Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to evaluate the short and long-term impact of pharmacovigilance (PV) training on the 5th year medical students’ knowledge about definitions and on the awareness of the regulatory aspects in PV.

Materials and Methods:

In academic year 2010/11, the students completed structured, questionnaire before and just after training. They also completed the same questionnaire 1-year after the training.

Results:

The students’ knowledge about PV significantly increased after training in the short term (P < 0.001). However, the improvement decreased significantly in the long-term (P < 0.001). Although long-term scores were higher than the baseline score, the difference was not statistically significant. Total scores were 17.5 ± 2.0, 20.8 ± 2.0 and 18.0 ± 2.5; before, at short and long-term after the training.

Conclusion:

PV training increased the students’ knowledge significantly. However, in the long-term, the impact of the training is limited. Repeated training of PV should be planned.

KEY WORDS: Awareness, impact, knowledge, medical training, pharmacovigilance

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, pharmacovigilance (PV) is the science and activities related to the detection, assessment, understanding, and prevention of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) or any other drug-related problem. More than 130 countries including Turkey are part of the WHO PV program.[1] The studies on PV have increased in our country after Turkish Pharmacovigilance Center (TUFAM) was established in 2005 and the related regulations were released.[2]

Spontaneous reporting by healthcare professionals (HCPs) has been shown to play an important role in identifying drug safety issues.[3] However, underreporting of ADRs has been a real problem in PV. In order to improve the reporting rate, it is important to educate the HCPs. The most appropriate time to do so, is during the undergraduate and the postgraduate training of the doctors.[4,5,6,7,8,9]

Just after the release of the regulations on PV, Dokuz Eylul University School of Medicine (DEUSM) implemented PV training program in the curriculum of 5th year medical students. The aim of the program was to increase the knowledge of medical students on PV and ADR and to enable them to develop the attitude and practice of spontaneous reporting.

We aimed to investigate the short and long-term impact of the PV training on the awareness and the knowledge of PV in 5th year medical students of DEUSM.

Materials and Methods

Pharmacovigilance training is imparted at the 5th year curriculum of medical students in DEUSM. The training on PV, imparted to small groups of 10–12 students, consists of 1-h of theoretical information, followed by 1-h of ADR reporting practice.

This prospective study was conducted after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the DEUSM (25.08.2011 no: 29-13/2011).

A structured questionnaire was used. Questions were divided into four groups: Group 1 questions tested the knowledge of TUFAM and written regulations for monitoring drug safety, group 2 questions tested the knowledge of WHO's ADR, serious ADR (sADR) and unexpected ADR (uADR) definition, group 3 questions tested the knowledge of qualified professionals to report an ADR according to regulations, group 4 questions tested the knowledge of the minimum criteria of ADR reporting.

The students completed the questionnaire before and just after PV training in academic year 2010/11. They completed the same questionnaire 1-year after (2011/12) the training in order to determine long-term effects of PV training. The completed questionnaires were named as questionnaire 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

All collected data were recorded in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmont, WA, USA). Correct answers were graded as one point and false answers were graded as zero point. The total score was 29. Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows 15.0 (SPSS 15.0 Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Differences between the results of the questionnaires were assessed by using repeated measures ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test when distributed normally and the Friedman's ANOVA test, followed by Wilcoxon signed rank test when distributed not normally. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Bonferroni correction was applied for the multiple comparisons in post-hoc Friedman's test statistics and significance level reduced to P < 0.016.

Results

Total number of the students in the 5th year was 117 in academic year 2010/11 but 77 students (65.8%) completing all three questionnaires were include for analysis. The mean age of the students were 23.1 ± 0.1 (range: 21-26). Female/male ratio was 0.87.

Students’ Answers to Group 1 Questions

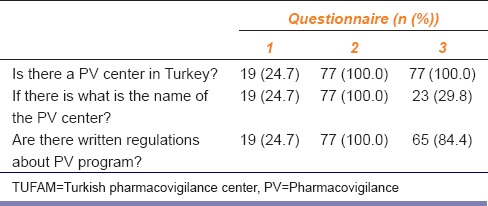

The students were tested for their awareness about the ADR reporting center and the regulations for drug safety. After the training, all students correctly answered the group 1 questions. In the questionnaire administered 1-year after the training, 29.8% of the students remembered the name of TUFAM. Whereas most of the students were still aware of the presence of a PV center and related regulations in Turkey [Table 1].

Table 1.

The number (n) and percentage of the students who gave correct answers to group 1 questions testing the knowledge of TUFAM and written regulations for monitoring drug safety in questionnaires (n=77)

Students’ Answers to Group 2 Questions

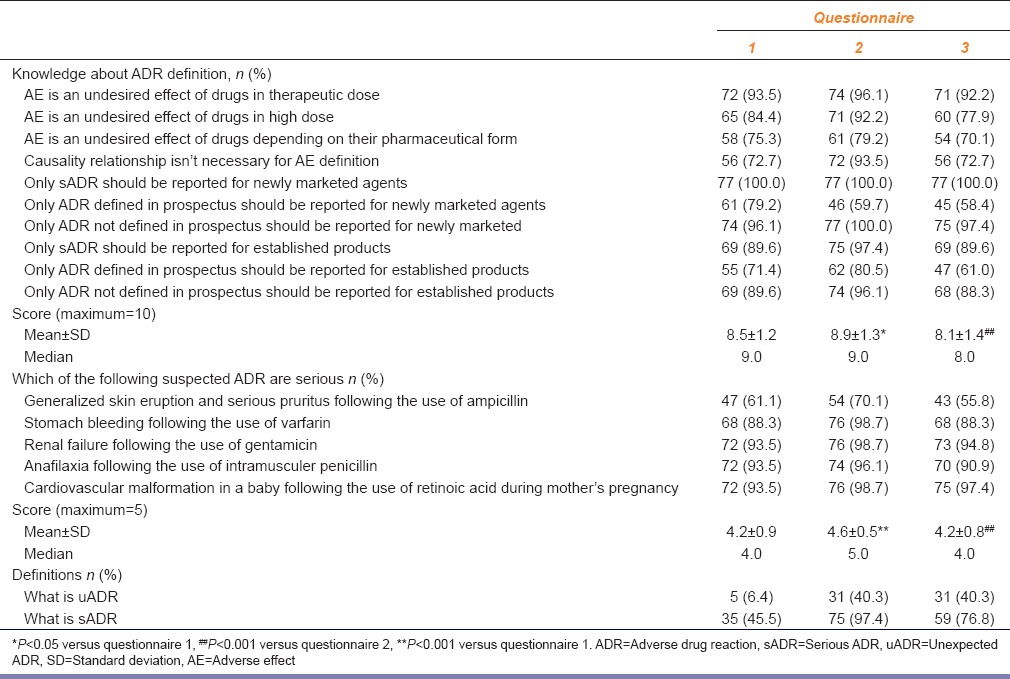

Questions about the definition of ADR were answered correctly by 72.7-93.5% of the students before the training. The total score of the correct answers was 8.5 out of 10. The score increased significantly after the training (P < 0.05). When ADR knowledge was tested using hypothetical case examples, the majority of the students knew which ADR was serious before the training. The total score of the correct answers was 4.2 out of 5. The score increased significantly just after the training (P < 0.01). However, the scores decreased significantly after 1-year.

The number of the students who gave correct answers to questions about the definitions of sADR and uADR increased just after the PV training and these were still high after 1-year [Table 2].

Table 2.

The number (n), percentage and the total scores of the students who gave correct answers for group 2 questions testing the knowledge of WHOs ADR, sADR and uADR definition in questionnaires (n=77)

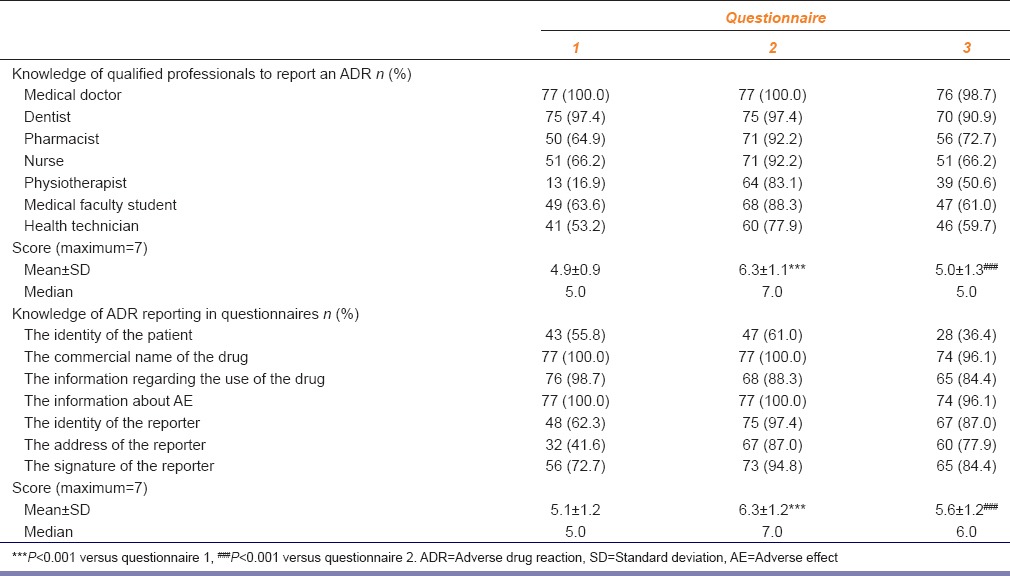

Students’ Answers to Group 3 Questions

Correct answers to the question “according to the regulations are the following HCPs responsible for reporting ADR?” increased significantly just after the training (P < 0.001). However, the number of correct answers decreased after 1-year [P < 0.001, Table 3].

Table 3.

The number (n), percentage and the total scores of the students who gave correct answers to group 3 and 4 questions testing the knowledge of qualified professionals to report an ADR according to regulations and testing the knowledge of ADR reporting in questionnaires (n=77), respectively

Students’ Answers to Group 4 Questions

Just after the training, the number of the students who answered correctly to the questions about ADR reporting increased (P < 0.001). However, the results decreased after 1-year [P < 0.001, Table 3].

Total Score

The students’ knowledge about PV significantly increased after the training in the short term (P < 0.001). However, the increment decreased in the long-term (P < 0.001). Although long-term scores were still slightly higher than the baseline score, the difference was not statistically significant. Consecutive total scores were 17.5 ± 2.0, 20.8 ± 2.0 and 18.0 ± 2.5 in the first, second and third questionnaires, respectively.

Discussion

Spontaneous ADR reporting is an important tool of ADR reporting in the of national PV system. It was shown that medical students’ or physicians’ knowledge about PV was inadequate in some countries[7,8,10,11] and it was reported that ADR reporting's increased after the training.[4,6] Therefore, medical students’ training is very important to increase ADR reporting.[5,7,8,12]

The importance of the ADR reporting was recognized by pharmacologists after the establishment of national PV system and legal regulations in 2005 and in many medical and pharmacy faculties, some revisions were made in their curriculum. In our university, 5th year medical students have been attending 2 h sessions – 1-h theoretical and 1-h practical related to basic definitions and regulations of PV since 2005.

In this study, the knowledge of 5th year medical students about ADR reporting and Turkish PV program was evaluated before, just after and 1-year after the PV training. Overall, the knowledge of students increased soon after the training. However, the increase did not remain steady except for the awareness of the existence of the TUFAM and the presence of the PV regulations in Turkey.

In many studies HCPs have some knowledge about the PV program and their spontaneous ADR reporting rate was low and one of the reasons for this was inadequate awareness of reporting ADRs.[9,13,14] These show the importance of the PV training.[6,14] The rate of spontaneous ADR in HCPs who learned about the importance of reportings, how to report an ADR and the role of PV system were high.[9] We think that our students will be serious about spontaneous ADR reporting in their professional life because most of them were aware of the existence of a national PV center and regulations in Turkey in their internship 1-year after the training.

The questions about the ADR definitions in the questionnaire were answered correctly by most of the students before the training because they had learning objectives about ADR of the drugs in previous years in their curricula. The number of the students who knew the definitions sADR increased just after the training. But the number of the students who knew the definition of uADR were also low just after the training. In Turkey, HCPs have to report sADR and uADR to – TUFAM, as per the regulations published in 2005. Therefore, the description of uADR must be highlighted in our training.[15,16]

Physicians, pharmacists, dentists, and nurses have to report ADR according to published regulations about PV in Turkey. All of the students’ replied in affirmative that physicians have to report ADR, both before and after the training. The question “can medical faculty students reporting?” was answered in affirmative by 64% the response was higher just after the training. However, medical students can not report the ADR according to current regulations. However, students’ perceiving themselves efficient to report is an important finding. Including the students in the list of HCPs who can report; is a proposal that can be submitted to the authorities regulators.

Lack of knowledge about how to report ADRs are among the basic reasons of the low rate of ADR reportings.[9,14,16] Therefore, PV trainings must emphasize on how to report. We also trained the students about how to report ADRs and which information should be included in the PV form. In our study, a great number of the students answered all the questions on the minimum information that should be included in a report in order for it to be valid, 1-year after the training was given during their internship. This suggests that 1-year after the training most of the students will fill the ADR reporting form easily in the future.

Students’ knowledge level and awareness on PV were limited 1-year after training. This demonstrates our lectures training are inadequate and continuous training programs are needed.

Conclusion

The undergraduate medical students are prospective prescribers of society. Therefore, increasing awareness about PV program through training starting in medical school appears to be necessary to enhance reporting. The effects of the educational intervention, however, were temporary and hence regular retraining is essential.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nill.

Conflict of Interest: No.

References

- 1.Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 10]. World Health Organization. WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. Looking at the Pharmacovigilance: Ensuring the Safe Use of Medicines. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_EDM_2004.8.pdf/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guide for the Monitorization and Evaluation of the Medicinal Products. Published in Official Gazete in 30th March, 2005 to Became Valid 30th June. 2005. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 10]. Available from: http://www.rega.basbakanlik.gov.tr/

- 3.Begum SS, Mansoor M, Sandeep A, Mahadevamma L, Krishnagoudar BS. Tools to improve reporting of adverse drug reactions – A review. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2013;23:262–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra D, Wardhan N, Rehan HS. Knowledge, attitude and practices associated with adverse drug reaction reporting amongst doctors in a teaching hospital. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2011;23:227–32. doi: 10.3233/JRS-2011-0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta P, Udupa A. Adverse drug reaction reporting and pharmacovigilance: Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions amongst resident doctors. J Pharm Sci Res. 2011;3:1064–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hema NG, Bhuvana KB, Sangeetha Pharmacovigilance: The extent of awareness among the final year students, interns and postgraduates in a government teaching hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1248–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naritoku DK, Faingold CL. Development of a therapeutics curriculum to enhance knowledge of fourth-year medical students about clinical uses and adverse effects of drugs. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21:148–52. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shankar PR, Subish P, Mishra P, Dubey AK. Teaching pharmacovigilance to medical students and doctors. Indian J Pharm. 2006;38:316–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pimpalkhute SA, Jaiswal KM, Sontakke SD, Bajait CS, Gaikwad A. Evaluation of awareness about pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction monitoring in resident doctors of a tertiary care teaching hospital. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehan HS, Vasudev K, Tripathi CD. Adverse drug reaction monitoring: Knowledge, attitude and practices of medical students and prescribers. Natl Med J India. 2002;15:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vora MB, Paliwal NP, Doshi VG, Barvaliya MJ, Tripathi CB. Knowledge of adverse drug reactions and the pharmacovigilance activity among the undergraduate medical students of Gujarat. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3:1511–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Upadhyaya P, Seth V, Moghe VV, Sharma M, Ahmed M. Knowledge of adverse drug reaction reporting in first year postgraduate doctors in a medical college. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2012;8:307–12. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S31482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oshikoya KA, Senbanjo IO, Amole OO. Interns’ knowledge of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics after undergraduate and on-going internship training in Nigeria: A pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardeep, Bajaj JK, Rakesh K. A survey on the knowledge, attitude and the practice of pharmacovigilance among the health care professionals in a teaching hospital in northern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:97–9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4883.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedrós C, Vallano A, Cereza G, Mendoza-Aran G, Agustí A, Aguilera C, et al. An intervention to improve spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting by hospital physicians: A time series analysis in Spain. Drug Saf. 2009;32:77–83. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai CK, Iyer G, Panchal J, Shah S, Dikshit RK. An evaluation of knowledge, attitude, and practice of adverse drug reaction reporting among prescribers at a tertiary care hospital. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2:129–36. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.86883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]