Abstract

Background

This study evaluates the prevalence of cardiovascular events in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) patients.

Methods

We distributed surveys to 1439 subjects from our ADPKD research database. 426 subjects with ADPKD completed and returned surveys. Seven of 426 surveys returned were children and were excluded from the study.

Results

ADPKD patients responding were female (63.2%), non-Hispanic (88.1%) and white (93.6%). The mean age of total group was 53.2 ± 13.7 years. 82.8% had a family history of ADPKD and 32.5% had reached end-stage renal disease (ESRD). With respect to cardiovascular risk factors 86.6% were hypertensive with a mean age at diagnosis of 36.9 ± 12.9 years and hypertension was significantly more prevalent in males. In addition, 19.6% of subjects were obese, 20.8% were smokers, 8.7% had diabetes, 45.7% had high cholesterol and 17.8% were sedentary. The most prevalent self reported cardiovascular events were arrhythmias (25.9%), evidence of peripheral vascular disease (16.5%), heart valve problems (14.4%), cardiac enlargement (9.5%), stroke or cerebral bleeding (7.5%), myocardial infarction (6%) and brain aneurysm (5.0%). The most commonly used antihypertensive medications were renin-angiotensin inhibitors used by 75% of ADPKD patients. Older ADPKD patients and those at ESRD had a significantly higher incidence of cardiovascular events.

Conclusion

These findings support the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and events in ADPKD patients and thus increasing risk for mortality. Due to the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the ADPKD population, early diagnosis and clinical intervention are recommended.

Keywords: Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, cardiovascular events, risk factor, morbidity, mortality

Introduction

Approximately 6 million Americans have combined chronic cardiovascular and kidney disease resulting in an increasing epidemic of heart and kidney failure [1]. This morbid association represents unique challenges to the clinician. Approximately 600,000 Americans are affected with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), with over 2000 patients starting dialysis every year [2]. Patients with ADPKD have an increased incidence of early onset hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and cardiovascular abnormalities [3, 4]. The reported relative mortality rate in patients with ADPKD ranges between 1.6 fold (95% confidence interval, 1.3 to2.0) and 3.2 folds higher (95% confidence interval, 2 to 4.8) in comparison with the general population [5].

Cardiovascular complications are the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with ADPKD [6]. Primary prevention therefore is important to reduce early morbidity and mortality. Thus there is a need for detection and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in the ADPKD population. There is evidence that blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) with better control of blood pressure has improved ADPKD patient and renal survival [7–9]. There also are results in hypertensive ADPKD patients which demonstrate that initial therapy with RAAS inhibition as compared to diuretics necessitates significantly few antihypertensive medications for comparable control of blood pressure [10].

The present study analyzed the cardiovascular events and risk factors in a large number of ADPKD patients according to gender, age, hypertension, cholesterol, smoking and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). This observational study was undertaken in an era in which the majority of patients were receiving RAAS inhibition.

Methods

Data source and study population

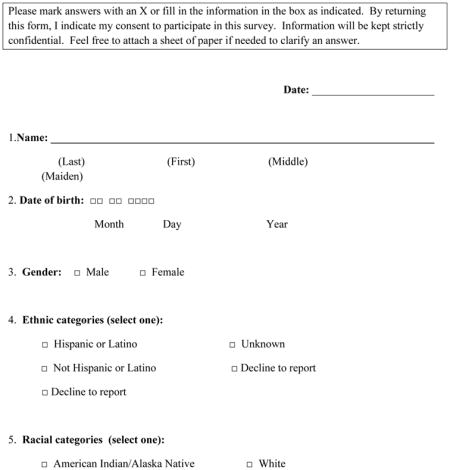

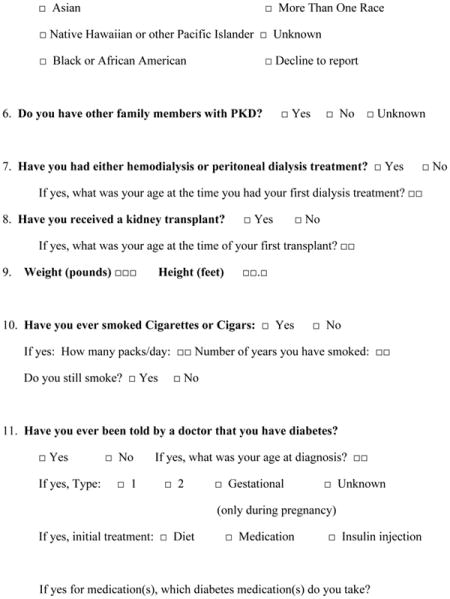

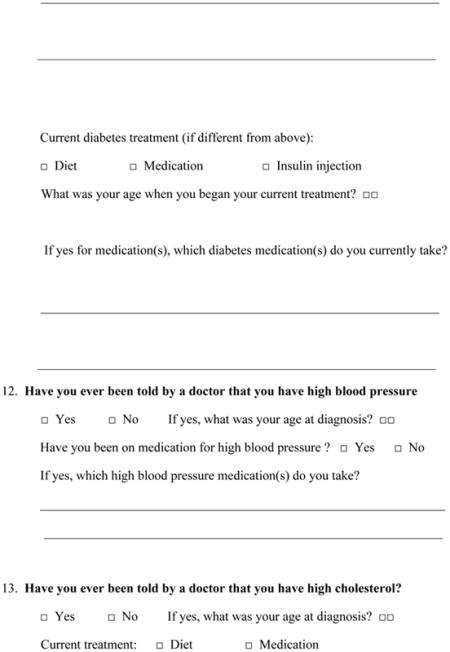

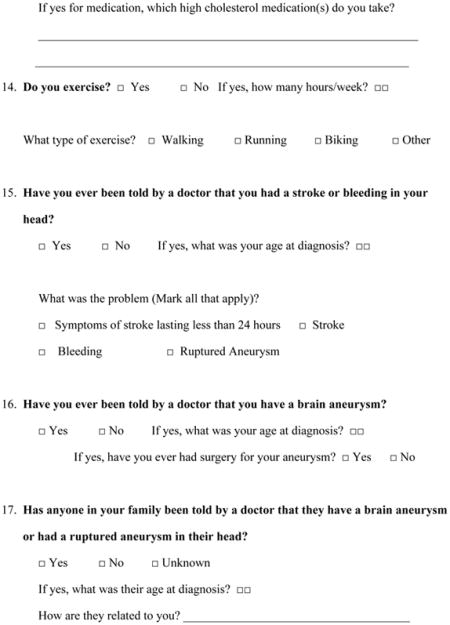

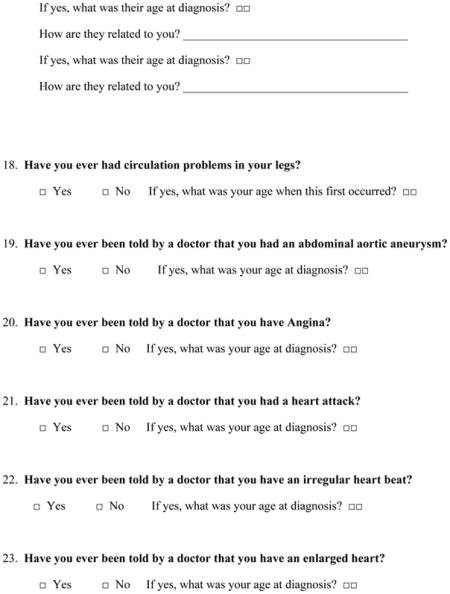

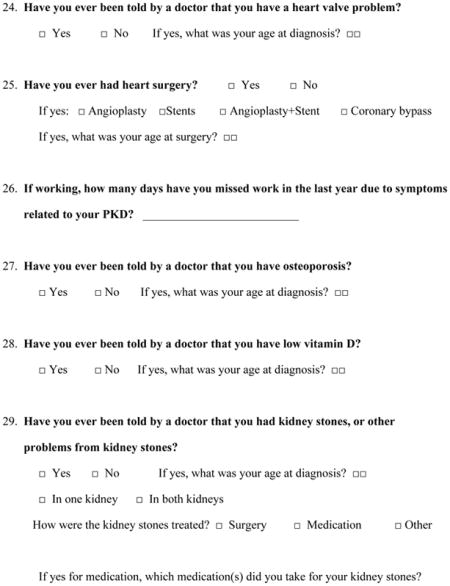

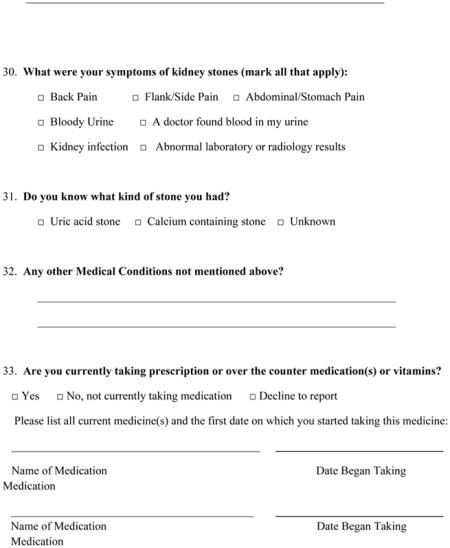

We developed a 6-page survey that was distributed to 1439 study subjects listed as having ADPKD in our database. The survey asked basic demographic questions and specific questions related to occurrence of cardiovascular disease in ADPKD patients, including occurrence of stroke, peripheral arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, left ventricular hypertrophy, and cardiac valvular abnormalities. The survey also collected information regarding the presence and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors, including hyperlipidemia, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and medication use.

The survey was sent in a single mailing (January 2011) with instructions to return the survey using a provided return envelope. 426 subjects with ADPKD (30%) returned the survey completed. Out of 426 surveys returned, 7 were from patients under the age of 18 and were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

SAS version 9.3 PROC FREQ and PROC MEANS were used to obtain descriptive statistics for the surveys. The difference between the distribution of age categories for men and women was tested using a contingency table Chi-square test. For this test p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Proportions for demographics were calculated as a percentage of all respondents. Proportions for other tables were calculated as a percentage of those who responded to that question.

Because multiple outcomes were tested, p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni method. Adjusted p-values less than 0.0036 (0.05 / 14) or unadjusted p-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. This adjustment corrects for the probability of getting a significant p-value purely by chance.

Results

Descriptive analysis of ADPKD patients responding

ADPKD patients responding were female (63.2%), non-Hispanic (88.1%) and white (93.6%) (Table 1). The mean age of the total group was 53.2 ± 13.7 years. 82.8% had a family history of ADPKD and 32.5% had reached ESRD. Among respondents analysis of cardiovascular risk factors (Table 2) demonstrated that 86.6% had hypertension with mean age of diagnosis of 36.9 ± 12.9 years with significantly higher prevalence in males, 19.6% were obese, 20.8% were smokers, 8.7% had diabetes, 45.7% had high cholesterol and 17.8% were sedentary. The most prevalent self reported cardiovascular events (Table 3) were arrhythmias (25.9%) with mean age of diagnosis of 43.3 ± 16.4 years, evidence of peripheral vascular disease (16.5%) with mean age of diagnosis of 45 ± 13 years, heart valve problems (14.4%) with mean age of diagnosis of 41.2 ± 16.5 years, cardiac enlargement (9.5%) with mean age of diagnosis of 42.6 ± 13.9 years, stroke or cerebral bleeding (7.5%) with mean age of diagnosis of 50.8 ± 13.4 years, myocardial infarction (6%) with mean age of diagnosis of 53.4 ± 9.6 years and brain aneurysm (5.0%) with mean age of diagnosis of 43.4 ± 13.7 years. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) were used in 75% of hypertensive ADPKD patients (Table 4). Statins and anti-platelet medications (aspirin) were used in 11 % and 22.5 % respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 419 survey respondents with ADPKD

| Variable | N | % of Total (419) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 145 | 34.6% |

| Female | 265 | 63.2% |

| Not reported | 9 | 2.2% |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 18 | 4.3% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 369 | 88.1% |

| Unknown or not reported | 32 | 7.6% |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| American Indian / Alaska Native | 3 | 0.7% |

| Asian | 3 | 0.7% |

| Black or African American | 3 | 0.7% |

| White | 381 | 93.6% |

| More than one race | 12 | 3.0% |

| Unknown or not reported | 17 | 4.1% |

|

| ||

| Family history of ADPKD | 347 | 82.8% |

| No | 37 | 8.8% |

| Unknown | 35 | 8.4% |

|

| ||

| ESRD | 136 | 32.5% |

| No | 271 | 64.7% |

| Unknown | 12 | 2.9% |

|

| ||

| Hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis | 83 | 19.8% |

| No | 329 | 78.5% |

| Unknown | 7 | 1.7% |

|

| ||

| Transplantation | 117 | 27.9% |

| No | 291 | 69.5% |

| Unknown | 11 | 2.6% |

|

| ||

| Dialysis and transplantation | 66 | 16% |

|

| ||

| Preemptive transplantation (never on dialysis) | 51 | 12.2% |

|

| ||

| Mean ± SD | ||

| Age at time of survey | 418 | 53.2 ± 13.7 |

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; ESRD, End-stage renal disease.

Table 2.

Incidence of cardiovascular risk factors in 419 survey respondents with ADPKD

| Variable | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 77 / 392 | 19.6% |

|

| ||

| Ever smoked | 156 / 412 | 37.9% |

| Current Smoker | 32 / 154 | 20.8% |

|

| ||

| Diabetes | 36 / 412 | 8.7% |

| Hypertension | 356 / 411 | 86.6% |

| High cholesterol | 188 / 411 | 45.7% |

| Sedentary | 73 / 411 | 17.8% |

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; BMI, Body mass index

Table 3.

Prevalence of cardiovascular events 419 survey respondents with ADPKD

| Variable | N | % | Age at Diagnosis Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke or cerebral bleeding | 31 / 412 | 7.5% | 50.8 ± 13.4 |

| Brain aneurysm | 20 / 397 | 5.0% | 43.4 ± 13.7 |

| Circulation problems in legs | 66 / 400 | 16.5% | 45 ± 13 |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 3 / 397 | 0.8% | 35.7 ± 26.8 |

| Angina | 13 / 399 | 3.3% | 48.9 ± 15.9 |

| Heart attack | 24 / 399 | 6% | 53.4 ± 9.6 |

| Irregular heart beat (arrhythmia) | 103 / 398 | 25.9% | 43.3 ± 16.4 |

| Enlarged heart | 38 / 400 | 9.5% | 42.6 ± 13.9 |

| Heart valve problem | 57 / 397 | 14.4% | 41.2 ± 16.5 |

| 5 | |||

|

| |||

| Heart surgery | 23 / 393 | 5.9% | 50.7 ± 11.9 |

| Angioplasty | 4 / 23 | 17.4% | |

| Stents | 8 / 23 | 34.8% | |

| Angioplasty + Stents | 3 / 23 | 13% | |

| Coronary bypass | 4 /23 | 17.4% | |

| Cardiac valve surgery | 4/23 | 17.4% | |

Table 4.

Use of antihypertensive drugs among 419 survey respondents with ADPKD

| Drug | Hypertensive ADPKD Patients | Non hypertensive ADPKD Patients | All ADPKD Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Diuretics | 78 /333 | 23.4% | 1 / 53 | 1.9% | 79 / 387 | 20.4% |

| Sympathetic blocking agents | 92 / 329 | 28% | 2 / 54 | 3.7% | 94 / 385 | 24.4% |

| Vasodilators | 14 / 331 | 4.2% | 1 / 53 | 1.9% | 15 / 387 | 3.9% |

| Ca Channel blockers | 87 / 330 | 26.4% | 0 / 54 | 0% | 87 / 386 | 22.5% |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors | 155 / 331 | 46.8% | 6 / 54 | 11.1% | 161 / 387 | 41.6% |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 92 / 331 | 27.8% | 2 / 51 | 3.9% | 94 / 384 | 24.5% |

Sub-groups analysis

Demographic parameters or cardiovascular risk factors were not significantly different between males and females (Table 5). The occurrence of reported heart attacks was significantly higher in males (11.4%) compared to females (3.1%) (Adjusted p-value of 0.0136) (Table 4).

Table 5.

Analysis of cardiovascular risk factors and events by gender among 419 survey respondents with ADPKD

| Variable | Male | Female | p-value1 | Adjusted p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 33/140 | 23.6% | 44/248 | 17.7% | 0.1668 | 1 |

| Current Smoker | 9/60 | 15.0% | 22/91 | 24.2% | 0.1719 | 1 |

| Diabetes | 12/144 | 8.3% | 23/264 | 8.7% | 0.8961 | 1 |

| Hypertension | 127/143 | 88.8% | 225/264 | 85.2% | 0.3127 | 1 |

| High cholesterol | 68/143 | 47.6% | 119/264 | 45.1% | 0.6322 | 1 |

| Stroke or cerebral bleeding | 10/144 | 6.9% | 20/144 | 7.6% | 0.81541 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Brain aneurysm | 5/138 | 3.6% | 14/255 | 5.5% | 0.41011 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 2/138 | 1.5% | 1/255 | 0.4% | 0.28082 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Angina | 8/140 | 5.7% | 5/255 | 2.0% | 0.07262 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart attack | 16/140 | 11.4% | 8/255 | 3.1% | 0.00101 | 0.0136 |

|

| ||||||

| Irregular heart beat (arrhythmia) | 32/139 | 23.0% | 71/255 | 27.8% | 0.29801 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Enlarged heart | 21/140 | 15.0% | 17/256 | 6.6% | 0.00691 | 0.0971 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart valve problem | 17/138 | 12.3% | 40/255 | 15.7% | 0.36551 | 1 |

Chi square test

Fisher’s exact test

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; BMI, Body mass index;

ADPKD respondents over the age of 45 were significantly more likely to report hypertension and high cholesterol than those 45 or under (Table 6). Cardiovascular events were higher in older ADPKD respondents but did not reach significance (Table 6).

Table 6.

Analysis of cardiovascular risk factors and events by age (more or less 45 years) among 419 survey respondents with ADPKD

| Variable | ≤45 years | >45 years | p-value1 | Adjusted p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 17/86 | 19.8% | 60/305 | 19.7% | 0.9843 | 1 |

| Current Smoker | 11/28 | 39.3% | 21/125 | 16.8% | 0.0082 | 0.1146 |

| Diabetes | 3/91 | 3.3% | 33/320 | 10.3% | 0.0367 | 0.5140 |

| Hypertension | 59/91 | 64.8% | 296/319 | 92.8% | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| High cholesterol | 14/91 | 15.4% | 174/319 | 54.6% | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Stroke or cerebral bleeding | 1/92 | 1.1% | 30/319 | 9.4% | 0.00781 | 0.1089 |

|

| ||||||

| Brain aneurysm | 2/90 | 2.2% | 18/306 | 5.9% | 0.16341 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 0/92 | 0 | 3/304 | 1.0% | n/a | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Angina | 1/92 | 1.1% | 12/306 | 3.9% | 0.31412 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart attack | 1/92 | 1.1% | 23/306 | 7.5% | 0.02311 | 0.3236 |

|

| ||||||

| Irregular heart beat (arrhythmia) | 14/91 | 15.4% | 89/306 | 29.1% | 0.00891 | 0.1239 |

|

| ||||||

| Enlarged heart | 2/91 | 2.2% | 36/308 | 11.7% | 0.00671 | 0.0943 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart valve problem | 8/91 | 8.8% | 49/305 | 16.1% | 0.08281 | 1 |

Chi square test

Fisher’s exact test

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; BMI, Body mass index;

ADPKD respondents with ESRD were significantly more likely to report diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol levels (Table 7). They also reported significantly higher incidence of stroke or cerebral bleeding, heart attack, and cardiac enlargement (Table 7).

Table 7.

Analysis of cardiovascular risk factors and events by gender among 419 ADPKD survey respondents with and without ESRD.

| Variable | ESRD | No ESRD | p-value1 | Adjusted p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity (BMI≥30) | 21/129 | 16.3% | 56/257 | 21.8% | 0.2012 | 1 |

| Current Smoker | 8/57 | 14.0% | 24/94 | 25.5% | 0.0938 | 1 |

| Diabetes | 22/135 | 16.3% | 13/270 | 4.8% | 0.0001 | 0.0015 |

| Hypertension | 132/135 | 97.8% | 218/269 | 81.0% | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| High cholesterol | 86/134 | 64.2% | 97/270 | 35.9% | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Stroke or cerebral bleeding | 20/135 | 14.8% | 10/271 | 6.7% | <.00011 | 0.0008 |

|

| ||||||

| Brain aneurysm | 12/131 | 9.2% | 8/259 | 3.1% | 0.01021 | 0.1434 |

|

| ||||||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 2/131 | 1.5% | 1/259 | 0.4% | 0.26212 | 1 |

|

| ||||||

| Angina | 8/132 | 6.1% | 5/260 | 1.9% | 0.03872 | 0.5417 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart attack | 16/133 | 12.0% | 8/259 | 3.1% | 0.00051 | 0.0066 |

|

| ||||||

| Irregular heart beat (arrhythmia) | 44/133 | 33.1% | 57/258 | 22.1% | 0.01871 | 0.2614 |

|

| ||||||

| Enlarged heart | 21/132 | 15.9% | 16/261 | 6.1% | 0.00171 | 0.0240 |

|

| ||||||

| Heart valve problem | 23/130 | 17.7% | 32/260 | 12.3% | 0.14981 | 1 |

Chi square test

Fisher’s exact test

ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease; BMI, Body mass index;

Discussion

The most common extra-renal complications that contribute to morbidity and mortality in ADPKD patients are of cardiovascular nature [4]. Hypertension is the most frequent cardiovascular complication in ADPKD and contributes to both an increased incidence of cardiovascular mortality and faster progression to ESRD [6, 11, 12]. Hypertension develops early in the course of ADPKD [13] and occurs in 50 – 70 % of ADPKD patients with normal kidney function [14,15]. Previously we have reported a median age at diagnosis of hypertension in ADPKD of 32 years in males and 34 years in females [16]. The current results support the presence of early hypertension in ADPKD. Hypertension is a widespread feature of this disease and has been reported in up to 80% of ADPKD patients with ESRD on dialysis [17]. Thus, the main and most effective therapy in ADPKD remains control of hypertension primarily by including RAAS inhibition [7, 8]. The definitive answer of whether treatment with either ACEIs or / and ARBs results in decreased rate of renal disease progression in ADPKD awaits the results of the HALT-PKD study [18]. However, it is important to control hypertension in ADPKD patients since it is a specific risk factor for intra-cerebral hemorrhage and aneurysm ruptures [19].

Our study demonstrates a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, obesity, diabetes and hypercholesterolemia in ADPKD population. In a previous study 22% of ADPKD patients (age 35.9 ± 11.1 years) with normal kidney function also fulfilled the International Diabetes Federation criteria of metabolic syndrome [20].

LVH is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and a common finding in hypertensive and even normotensive ADPKD patients [21–24]. However, a recent study in ADPKD patients with preserved renal function reported a prevalence of LVH of 3.9 % (25). Increased left ventricular mass index does occur in children and young adults with ADPKD [13, 26–28]. The early onset of hypertension in ADPKD may be associated with LVH in nearly 50% of ADPKD patients by their 40s [22]Increased LVMI has been found to be associated with poor renal and overall outcomes in ADPKD patients [12]. A significant correlation between hypertension and increased LVMI has been demonstrated in both children and adults with ADPKD [13, 26–28]. RAAS inhibition in hypertensive ADPKD patients has led to long-term reversal of LVH [29,30]. This finding was significantly greater in association with rigorous control of blood pressure (< 120/80 mmHg) in ADPKD patients [30].

Structural cardiac abnormalities are found more often in ADPKD patients than in non-ADPKD family members or normal controls [31]. A prospective echocardiographic study in ADPKD subjects found mitral valve prolapse in 26% and mitral regurgitation in 31% [27]. Tricuspid regurgitation and aortic regurgitation also were found in 15% and 8%, respectively (29). In the current ADPKD study overall heart valve problems were found in 14.4% of patients.

The occurrence rate of coronary events, such as angina, myocardial infarction, and need for coronary revascularization in ADPKD patients with normal renal function has not been previously reported in the literature. Our survey reported that 3.3% of respondents had angina, 6% had suffered a heart attack and 5.9 % had undergone angioplasty, angioplasty and stent or cardiac valve surgery. The mean age of heart surgery was 50.7 ±11.9 years. ADPKD patients with ESRD had less coronary events than matched ESRD patients of other causes [32, 33]. This has been attributed to less severe anemia in ADPKD patients [32, 33]. This is probably due to increased endogenous erythropoietin production in ADPKD patients [34].

Arterial aneurysms, particularly intracranial aneurysms, are more prevalent in ADPKD patients than in the general population (4.0–11.7% versus 1.0%) [35, 36]. Moreover, it has been suggested that ADPKD is a risk factor for coronary artery aneurysms [37]. Abdominal aortic aneurysm also appears to be more prevalent in ADPKD patients [38, 39]. The incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysm in our cohort was very low (0.8%). However, a tendency towards larger aortic diameters in ADPKD patients compared to a control population has previously been reported [39].

The other major vascular abnormality in ADPKD is intracranial aneurysms (ICA). The prevalence ranges from 5% in patients with no family history of ICA to 21% in those with a positive family history of ICA rupture [32, 35, 41]. The prevalence may be even higher in ADPKD patients on dialysis, as observed in our study. An occurrence rate of both asymptomatic and ruptured ICA of 33.3 % has been reported in ADPKD patients with ESRD [42]. Another study [43] found no difference in incidence of cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) between ADPKD patients on dialysis and a non-PKD dialysis patient population. Only 25–50% of CVAs in ADPKD patients have been reported to result from ICA rupture [6, 44]. In our cohort the prevalence of brain aneurysms and stroke or intracerebral bleeding were respectively 5% and 7.5%. ICA rupture accounts for a 35–55% risk of combined morbidity and mortality [19, 45], thus, identification and screening of patients at risk for developing symptomatic ICA are recommended. Systematic screening of ICA with 3-dimensional magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is recommended for ADPKD patients, particularly for adult patients (≥30 years), with a positive family history of hemorrhagic stroke or ICA, patients undergoing major surgery with potential hemodynamic instability and those at high risk occupations [46, 47]. MRA has been recommended every 5 years if initially negative and every 2–3 years if positive [46]. However, recent data support less requierement for screening for ICAs in ADPKD patients, and therefore widespread screening is not indicated [48].

Patients with non-PKD chronic kidney disease are at significantly increased cardiovascular events and risk factors [49]. However, ADPKD is unique by early occurrence of hypertension, heart valve problems and ICA. As expected, older ADPKD patients and those with ESRD are at higher risk for cardiovascular events. However, male gender may be losing its importance as a risk factor for cardiovascular events in ADPKD. The early and effective treatment of hypertension in ADPKD is critical in the prevention of cardiovascular events in ADPKD.

Conclusion

There are intrinsic limitations to the survey based nature of this study and the reported frequencies may be underestimated. Nevertheless, these present findings confirm the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and events in ADPKD patients which are associated with increased risk for mortality. Moreover, older ADPKD subjects and those with ESRD had an increased risk for cardiovascular events, and this increased morbidity and mortality. Due to the prevalence and early onset of cardiovascular risk factors in the ADPKD population, early diagnosis and intervention by aggressively treating blood pressure in ADPKD patients is important to prevent LVH, cardiovascular complications, and mortality.

Acknowledgments

IH has received an International Society of Nephrology funded fellowship and support from Laboratory of Kidney Pathology (LR00SP01-Pr Ben Maiz Hedi) Charles Nicolle Hospital, Tunis – Tunisia.

PM supported in part by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780.

This research was supported by grant numbers M01RR00051, M01RR00069 General Research Centers Program, National Center for Research Resources (NCRR)/NIH; by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI grant number ULI RR025780 by grant DK34039 from NIH(NIDDK) and by the Zell Family Foundation. The content of this publication are the authors sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent the official NIH views.

Appendix. Survey on Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.McCullough PA. Scope of cardiovascular complications in patients with kidney disease. Ethn Dis. 2002;12:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2011 Annual Data Report. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrier RW. Optimal care of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2006;11:124–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ecder T, Schrier RW. Cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:221–228. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florijin KW, Noteboom WM, Van Saase JL, Chang PC, Breuning MH, Vandenbroucke JP. A century of mortality in five large families with polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:370–374. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fick GM, Johnson AM, Hammond WS, Gabow PA. Causes of death in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:2048–2056. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5122048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schrier RW, McFann KK, Johnson AM. Epidemiological study of kidney survival in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63:678–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patch C, Charlton J, Roderick PJ, Gulliford MC. Use of antihypertensive medications and mortality of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57:856–862. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orskov B, Rømming Sørensen V, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Strandgaard S. Improved prognosis in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Denmark. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2034–2039. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01460210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ecder T, Edelstein CL, Fick-Brosnahan GM, Johnson AM, Chapman AB, Gabow PA, Schrier RW. Diuretics versus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:98–103. doi: 10.1159/000046231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iglesias C, Torres V, Offord K, Holley K, Beard C, Kurland L. Epidemiology of adult polycystic kidney disease, Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1935–1980. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983;2:630–639. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(83)80044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabow PA, Johnson AM, Kaehny WD, Kimberling WJ, Lezotte DC, Duley IT, Jones RH. Factors affecting the progression of renal disease in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1992;41:1311–1319. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeier M, Geberth S, Schmidt KG, Mandelbaum A, Ritz E. Elevated blood pressure profile and left ventricular mass in children and young adults with adult polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3:1451–1457. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V381451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman AB, Schrier RW. Pathogenesis of hypertension in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 1991;11:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ecder T, Schrier RW. Hypertension in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: early occurrence and unique aspects. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:194–200. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V121194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrier RW, Johnson AM, McFann K, Chapman AB. The role of parental hypertension in the frequency and age of diagnosis of hypertension in offspring with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1792–1799. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milutinovic J, Fialkow PJ, Agodoa LY, Phillips PA, Rudd TG, Bryant JI. Adult polycystic kidney disease symptoms and clinical findings. Q J Med. 1984;53:511–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman AB, Torres VE, Perrone RD, Steinman TI, Bae KT, Miller JP, Miskulin DC, Rahbari Oskoui F, Masoumi A, Hogan MC, Winklhofer FT, Braun W, Thompson PA, Meyers CM, Kelleher C, Schrier RW. The HALT polycystic kidney disease trials: design and implementation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:102–109. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04310709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaveau D, Pirson Y, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Macnicol A, Gonzalo A, Grunfeld JP. Intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1994;45:1140–1146. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pietrzak-Nowacka M, Safranow K, Byra E, Bińczak-Kuleta A, Ciechanowicz A, Ciechanowski K. Metabolic syndrome components in patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2009;32:405–410. doi: 10.1159/000260042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koren MJ, Devereux RB, Casale PN, Savage DD, Laragh JH. Relationship of left ventricular mass and geometry to morbidity and mortality in uncomplicated essential hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:345–352. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman AA. Left ventricular hypertrophy in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1292–1297. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V881292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saggar-Malik A, Missouris CG, Gill JS, Singer DR, Markandu ND, MacGregor GA. Left ventricular mass In normotensive subjects with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. BMJ. 1994;309:1617–1618. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6969.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bardaji A, Vea AM, Gutierrez C, Ridao C, Richart C, Oliver JA. Left ventricular mass and diastolic function in normotensive young adults with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:970–975. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(98)70071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrone RD, Abebe KZ, Schrier RW, Chapman AB, Torres VE, Bost J, Kaya D, Miskulin DC, Steinman TI, Braun W, Winklhofer FT, Hogan MC, Rahbari-Oskoui F, Kelleher C, Masoumi A, Glockner J, Halin NJ, Martin D, Remer E, Patel N, Pedrosa I, Wetzel LH, Thompson PA, Miller JP, Bae KT, Meyers CM HALT PKD Study Group. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Assessment of Left Ventricular Mass in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2508–2515. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04610511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ivy DD, Shaffer EM, Johnson AM, Kimberling WJ, Dobin A, Gabow PA. Cardiovascular abnormalities in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;5:2032–2036. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5122032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardaji A, Martinez-Vea A, Valero A, Gutierrez C, Garcia C, Ridao C, Oliver JA, Richart C. Cardiac involvement in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a hypertensive heart disease. Clin Nephrol. 2002;56:211–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cadnapaphornchai MA, McFann K, Strain JD, Masoumi A, Schrier RW. Increased left ventricular mass in children with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and borderline hypertension. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1192–1196. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ecder T, Edelstein CL, Chapman AB, Johnson AM, Tison L, Gill EA, Brosnahan GM, Schrier RW. Reversal of left ventricular hypertrophy with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in hypertensive patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:1113–1116. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schrier R, McFann K, Johnson A, Chapman A, Edelstein C, Brosnahan G, Ecder T, Tison L. Cardiac and renal effects of standard versus rigorous blood pressure control in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: results of a seven-year prospective randomized study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1733–1739. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000018407.60002.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hossack KF, Leddy CL, Johnson AM, Schrier RW, Gabow PA. Echocardiographic findings in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:907–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810063191404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pirson Y, Christophe JL, Goffin E. Outcome of renal replacement therapy in adult polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:24–28. doi: 10.1093/ndt/11.supp6.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritz E, Zeier M, Schneider P, Jones E. Cardiovascular mortality of patients with polycystic kidney disease on dialysis: Is there a lesson to learn? Nephron. 1994;66:125–128. doi: 10.1159/000187788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verdalles U, Abad S, Vega A, Ruiz Caro C, Ampuero J, Jofre R, Lopez-Gomez JM. Factors related to the absence of anemia in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2011;32:69–74. doi: 10.1159/000323095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman AB, Rubinstein D, Hughes R, Stears JC, Earnest MP, Johnson AM, Gabow PA, Kaehny WD. Intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:916–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209243271303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruggleri PM, Poulos N, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Obuchowski NA, Awad IA, Braun WE, Nally J, Lewin JS, Modic MT. Occult intracranial aneurysms in polycystic kidney disease: screening with MR angiography. Radiology. 1994;191:33–39. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.1.8134594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadimeri H, Lamm C, Nyberg G. Coronary aneurysms in patients with adult polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:837–841. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V95837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montoliu J, Torras A, Revert L. Polycystic kidneys and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Lancet. 1980;1:1133–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman AB, Hilson AJW. Polycystic kidneys and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Lancet. 1980;1:646–647. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torra R, Nicolau C, Badenas C, Brú C, Pérez L, Estivill X, Darnell A. Abdominal aortic aneurysms and adult polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2483–2486. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7112483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huston J, Torres VE, Sullivan PP, Offord KP, Wiebers DO. Value of magnetic resonance angiography for the detection of intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3:1871–1877. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V3121871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konoshita T, Okamoto K, Koni I, Mabuchi H. Clinical characteristics of polycystic kidney disease with end-stage renal disease. Clin Nephrol. 1998;50:113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christophe JL, Van Ypersele de Strihou C, Pirson Y. Complications of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in 50 haemodialysed patients. A case-control study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:1271–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeier M, Geberth S, Ritz E, Jaeger T, Waldherr R. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease - clinical problems. Nephron. 1988;49:177–183. doi: 10.1159/000185052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schievink WI, Torres VE, Piepgras DG, Wiebers DO. Saccular intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;3:88–95. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiebers DO, Torres VE. Screening for unruptured intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:953–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209243271310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu HW, Yu SQ, Mei CL, Li MH. Screening for intracranial aneurysm in 355 patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Stroke. 2011;42:204–206. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Irazabal MV, Huston J, 3rd, Kubly V, Rossetti S, Sundsbak JL, Hogan MC, Harris PC, Brown RD, Jr, Torres VE. Extended Follow-Up of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Detected by Presymptomatic Screening in Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1274–1285. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09731110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarnak MJ. Cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:11–17. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]