Abstract

Targeted therapeutics have significant potential as therapeutic agents because of their selectivity and efficacy against tumors resistant to conventional therapy. The goal of this study was to determine the comparative activity of monovalent, engineered anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins fused to recombinant gelonin (rGel) to the activity of bivalent IgG-containing immunoconjugates. Utilizing Herceptin and its derived humanized single chain antibody (scFv) (designated 4D5), we generated a bivalent chemical Herceptin/rGel conjugate along with corresponding monovalent recombinant immunotoxins in two orientations: 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5. All the constructs showed similar affinity to Her2/neu overexpressing cancer cells but demonstrated significantly different antitumor activities. The rGel/4D5 orientation construct and Herceptin/rGel conjugate were superior to the 4D5/rGel construct in in vitro and in vivo efficacy. The enhanced activity was attributed to improved intracellular toxin uptake into target cells and efficient downregulation of Her2/neu-related signaling pathways. The Her2/neu-targeted immunotoxins effectively targeted cells with Her2/neu expression level >1.5×105 sites per cell. Cells resistant to Herceptin or chemotherapeutic agents were not cross-resistant to rGel-based immunotoxins. Against SK-OV-3 tumor xenografts, the rGel/4D5 construct with excellent tumor penetration showed impressive tumor inhibition. Although the Herceptin/rGel conjugate demonstrated comparatively longer serum half-life, the in vivo efficacy of the conjugate was similar to the rGel/4D5 fusion. These comparative studies demonstrate that the monovalent, engineered rGel/4D5 construct displayed comparable in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy to that of the bivalent Herceptin/rGel conjugate. Immunotoxin orientation can significantly impact the overall functionality and performance of these agents. The recombinant rGel/4D5 construct with excellent tumor penetration and rapid blood clearance may avoid unwanted toxicity to normal tissues when administered to patients and warrants consideration for further clinical evaluation.

Keywords: immunotoxin, Her2/neu, gelonin, valency, design optimization

Introduction

Numerous studies have revealed that Her2/neu overexpression by tumors is a threshold event leading to a highly aggressive cellular phenotype, and therapeutic strategies directed against Her2/neu have rapidly gained recognition (1, 2). Her2/neu targeted therapies including Herceptin and Lapatinib have significantly improved outcomes in Her2/neu positive cancers; however use of these agents can be limited by resistance and tolerability issues (3, 4). Therefore, there is a need for novel and improved therapeutic approaches targeting Her2/neu.

Immunotoxins are exquisitely powerful cytotoxic proteins (5, 6). Initial studies focused on constructs created by chemically conjugating an antibody to a protein toxin (7, 8). With advances in recombinant DNA technology, engineered antibody fragments have been employed to deliver various toxins to Her2/neu positive tumor cells (9, 10). There have been numerous studies examining the impact of construct size, antibody affinity and the valency of constructs on overall efficacy (11, 12). Wels et al suggested that higher avidity and longer residence time of IgG-based immunoconjugates may outweigh the improved tumor penetration of scFv-based constructs (13). However, immunoconjugate development has been hampered by nonspecific toxicity and vascular leak syndrome (14). In addition, tight junctions between tumor cells and high interstitial tumor pressures could, in theory, limit the successful use of IgG conjugates for solid tumors (12).

Recombinant engineering of immunotoxins has the potential to overcome many of these problems (12, 15). To improve Her2/neu-targeting properties, Adams et al suggested that (scFv)2 constructs display improved tumor targeting and retention compared to scFv monomers (16). However, Pastan et al described diabody-based immunotoxins (designated e23 (dsFv)2/PE) showing >10 fold greater in vitro cytotoxicity than their monovalent counterparts but only about 2 fold greater activity in vivo than the monovalent analogs (17). The high-affinity of diabodies may result in formation of a binding-site barrier at the periphery of tumors which impedes immunotoxin penetration into the tumor mass (18). Thus, the therapeutic window for Her2/neu targeting may be optimized utilizing other structural design changes instead of focusing exclusively on valency issues.

Recombinant gelonin (rGel), a 29kDa single chain ribosome-inactivating protein, has been well-established as a highly cytotoxic payload for chemical conjugates or fusion constructs for the treatment of many tumor types (19–21). In this study, we utilized Herceptin and its humanized scFv (designated 4D5) to generate a conventional Herceptin/rGel chemical conjugate and corresponding recombinant immunotoxins in two orientations: 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5. Further characterization studies were performed including examining the impact of valency and construct orientation on in vitro selectivity, specificity and efficacy of these agents as well as comparison of their pharmacokinetics, tumor penetration and tumor targeting efficacy in vivo against tumor xenografts.

Results

Preparation of rGel-based immunotoxins

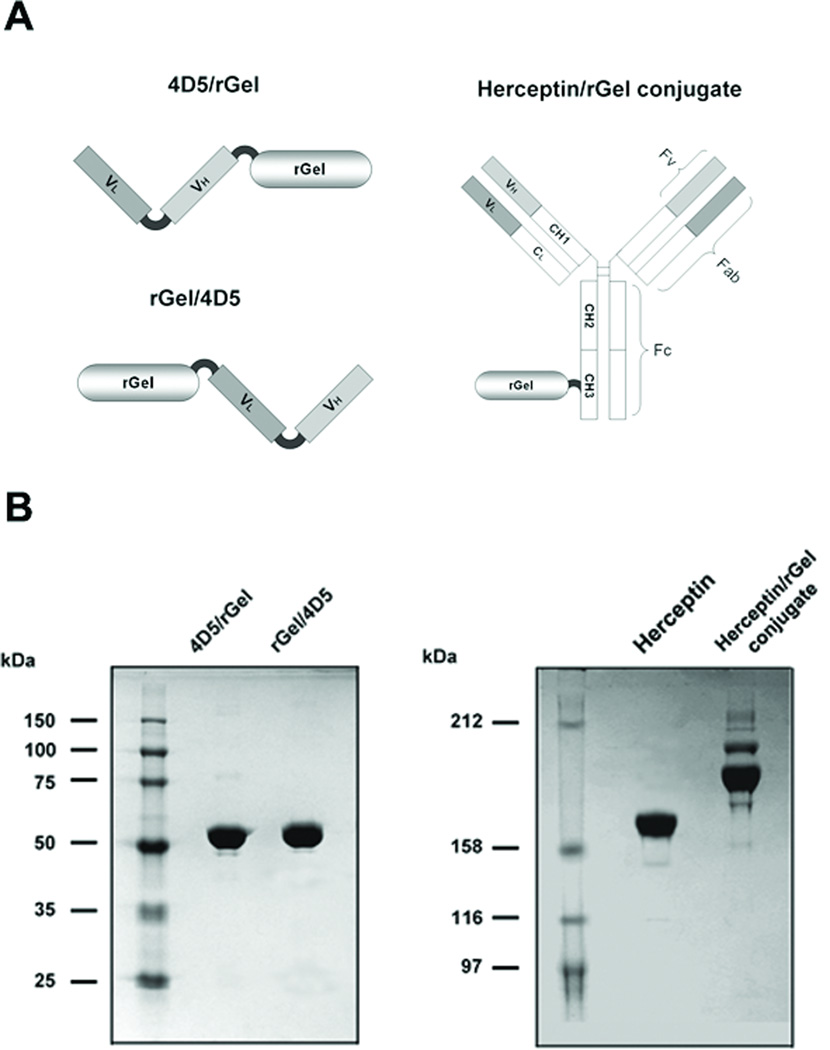

Antibody-toxin conjugates were generated with a disulfide-based SPDP linker for facile release of toxin from the antibody carrier (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, the final product contained a mixture of immunoconjugates containing one rGel molecule (major) and two rGel molecules (minor) (average molar ratio of 1.21 rGel molecules per antibody). No free Herceptin or free rGel were detected.

Figure 1.

Construction and preparation of Herceptin-based immunotoxins. (A) Schematic diagram of immunotoxin constructs containing scFv 4D5 or full-length antibody Herceptin and rGel. (B) Purified immunotoxins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions.

The monovalent immunotoxins were generated by fusing scFv 4D5 to the rGel using the flexible GGGGS linker in two orientations (4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5, Fig. 1A). Both immunotoxins were expressed in E.coli AD494 (DE3) pLysS. Following purification, the immunotoxins were shown to migrate at the expected molecular weight (55 kDa under non-reducing condition) with a purity >95% (Fig. 1B).

Analysis of binding affinity

The binding affinities of monovalent fusion constructs, and bivalent chemical conjugate were assessed by ELISA using Her2/neu extracellular domain (ECD) (Fig. 2A). The apparent binding affinities (Kd) were determined by calculating the concentration of immunotoxins that produced half-maximal specific binding. The monovalent 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5 demonstrated apparent affinities of 0.106nM and 0.142nM respectively and the bivalent Herceptin/rGel conjugate had an apparent affinity of 0.201nM. These results are in agreement with the published affinity values for native Herceptin to the Her2/neu receptor (Kd 0.15nM (22)).

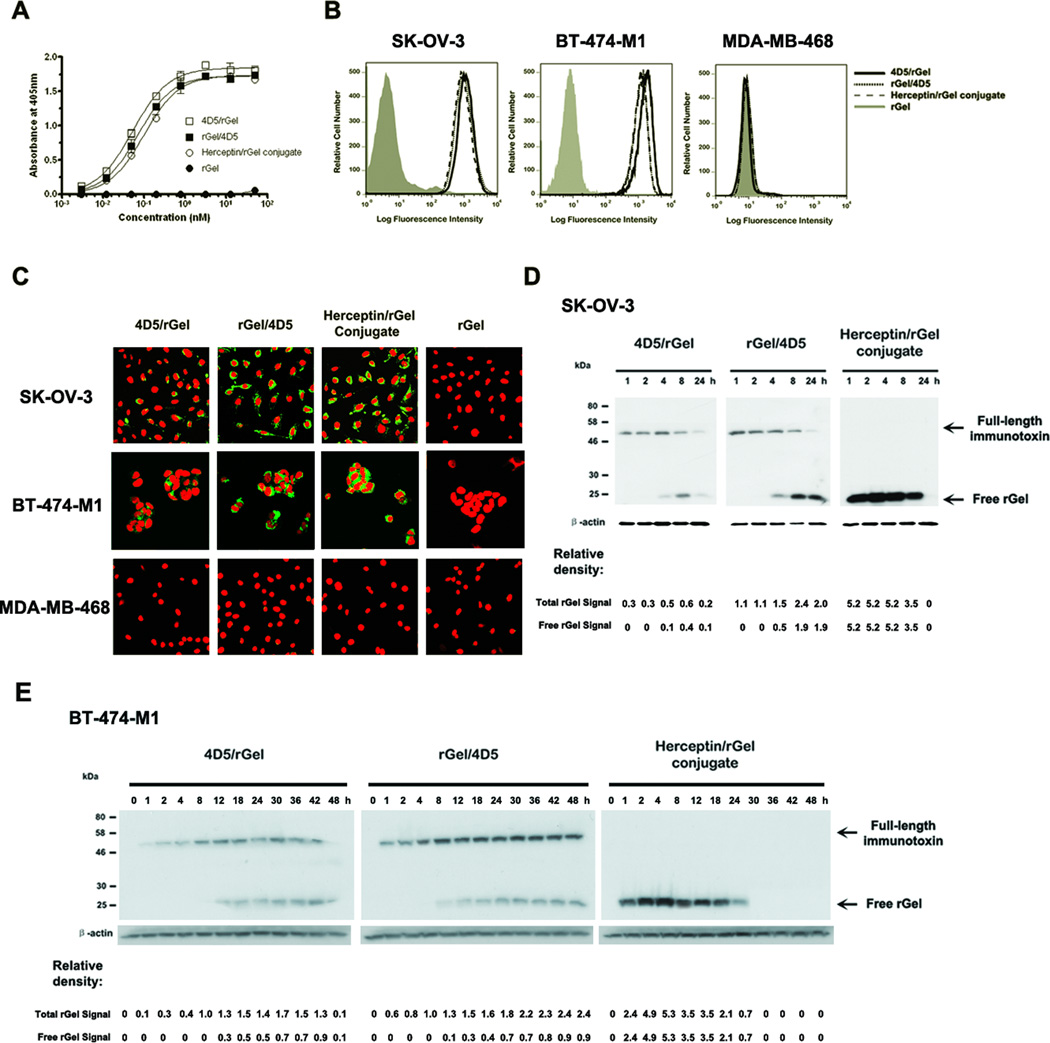

Figure 2.

Characterization of anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins. (A) Binding curves of immunotoxins to Her2/neu ECD by ELISA. (B) Binding affinity analysis of 25 nM constructs on Her2/neu-positive (SK-OV-3 and BT-474-M1) and -negative (MDA-MB-468) cells by flow cytometry. (C) Internalization analysis of Her2/neu-positive and -negative cells 4 hr after treatment with 25 nM immunotoxin. Cells were subjected to immunofluorescent staining with anti-rGel antibody (FITC-conjugated secondary) and with propidium iodine nuclear counterstaining. (D) and (E) Western blot analysis of intracellular behavior of 25 nM immunotoxin in SK-OV-3 and BT-474-M1 cells. Relative density of total rGel signal and free rGel signal was normalized to the β-actin protein loading control.

We next tested the cellular Her2/neu binding activities of these immunotoxins by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2B, all the immunotoxins produced higher staining intensities with the Her2/neu positive SK-OV-3 and BT-474-M1 cells and displayed a high selectivity compared to negative MDA-MB-468 cells. These studies confirmed that monovalent fusion constructs can display virtually identical binding affinities compared to their original bivalent antibody-based conjugates.

Cell-free protein synthesis inhibitory activity

To examine the n-glycosidic activity of rGel component of immunotoxins, these materials were tested by cell-free protein synthesis assay. Inhibition curves for 4D5/rGel, rGel/4D5, and Herceptin/rGel conjugate were compared with that of native rGel (Supplementary Fig. S1). The calculated IC50 values for each immunotoxin were found to be virtually identical (55.2, 48.9, 38.3 versus 70.3 pM for rGel, respectively). The consistency of rGel-based immunotoxins clearly demonstrated that no loss of toxin enzymatic activity occurred in the different constructs.

Cellular uptake and toxin delivery of immunotoxins

We next examined the comparative ability of the immunotoxins to internalize into SK-OV-3, BT-474-M1 and MDA-MB-468 cells. As shown in Fig. 2C, after 4h exposure, the rGel moiety of all the immunotoxins was observed primarily in the cytosol after treatment of SK-OV-3 or BT-474-M1 cells, but not MDA-MB-468 cells. This demonstrated that all constructs were comparable in efficient internalization after exposure to Her2/neu positive cells. The internalization efficiency of all the immunotoxins was further examined by time-dependent western blot analysis of the total rGel signal (full-length immunotoxin + free rGel) (Fig. 2D and 2E). The Herceptin/rGel conjugate showed the fastest and most efficient internalization into target cells. Both 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5 internalized rapidly into SK-OV-3 cells. However, the rGel/4D5 construct was found to internalize much faster than 4D5/rGel into BT-474-M1 cells. Compared to 4D5/rGel, rGel/4D5 displayed a comparatively higher and more prolonged intracellular concentration.

The intracellular release of rGel after endocytosis of various constructs was assessed based on analysis of the signal for free rGel (Fig.2D and 2E). For the Herceptin/rGel conjugate, there was a rapid initial delivery of free rGel to the cytoplasm within the first hour after drug exposure. The Herceptin/rGel conjugate delivered the greatest amount of rGel to both SK-OV-3 and BT-474-M1 cells. As for monovalent constructs, both fusions displayed similar initial delivery of free rGel in target cells, but the rGel/4D5 orientation construct delivered more prolonged higher levels of rGel compared to 4D5/rGel.

In vitro cytotoxicity of immunotoxins

The cytotoxic effects of the constructs were then tested against a variety of different tumor cell lines. As shown in Table 1, all the immunotoxins demonstrated specific cytotoxicity to cells expressing +3 and +4 levels of Her2/neu. Targeting indices ranged from 54 to 5120 and 21 to 2364 for Herceptin/rGel conjugate and rGel/4D5 respectively. The 4D5/rGel construct was comparatively less potent with targeting indices only as high as 213. Treatment of Herceptin-resistant BT-474-M1 (HR) cells demonstrated no cross-resistance to rGel-based immunotoxins compared to parental BT-474-M1 cells. In addition, MCF-7 cells transfected with Her2/neu (MCF-7/Her2) showed increased resistance to chemotherapeutic agents (Supplementary Fig. S2), but showed increased sensitivity to these constructs. The cytotoxicity of Herceptin/rGel conjugate and rGel/4D5 outperformed that of 4D5/rGel, which appeared to result from improved internalization and intracellular rGel delivery. Antigen-negative cells or those expressing relatively low (+1 and +2) levels of Her2/neu were not specifically targeted by any of the constructs.

Table 1.

Comparative IC50 Values of Fusion Constructs Against Various Types of Tumor Cell Lines.

| Cell Line | Type | Her2/neu Level |

IC50 (nM) | Targeting Index* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herceptin | 4D5/rGel | rGel/4D5 | Herceptin/rGel Conjugate |

rGel | 4D5/rGel | rGel/4D5 | Herceptin/rGel Conjugate |

|||

| SK-BR-3 | Breast | ++++ | 60.52 | 5.10 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 851.14 | 167 | 2364 | 5120 |

| BT-474-M1 | Breast | ++++ | 50.35 | 26.53 | 0.74 | 0.17 | 457.09 | 17 | 618 | 2689 |

| BT-474-M1 (HR) | Breast | ++++ | 7930.49 | 91.92 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 315.28 | 3 | 582 | 2425 |

| MCF-7/Her2 | Breast | ++++ | 8128.31 | 32.36 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 263.03 | 8 | 939 | 2391 |

| NCI-N87 | Gastric | ++++ | 668.21 | 2.37 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 505.48 | 213 | 3159 | 2407 |

| SK-OV-3 | Ovarian | ++++ | 1026.80 | 70.86 | 0.54 | 0.28 | 501.19 | 23 | 928 | 1790 |

| Calu-3 | Lung | ++++ | 4015.33 | 21.62 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 457.09 | 20 | 2285 | 2539 |

| MDA-MB-453 | Breast | +++ | 9120.11 | 543.7 | 1.62 | 0.79 | 435.70 | 21 | 269 | 552 |

| MDA-MB-361 | Breast | +++ | 9549.93 | 776.25 | 31.62 | 12.30 | 660.69 | 1 | 21 | 54 |

| MDA-MB-435S | Breast | ++ | N.D.† | 120.64 | 111.15 | 181.68 | 364.33 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| BT-20 | Breast | ++ | N.D. | 429.14 | 284.97 | 174.38 | 232.22 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ZR-75-1 | Breast | ++ | N.D. | 5903.00 | 6005.10 | 6555.07 | 3473.20 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A-431 | Epidermoid | + | N.D. | 98.31 | 106.68 | 213.99 | 167.38 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| MCF-7 | Breast | + | – | 595.39 | 322.18 | 222.89 | 197.15 | N.D.† | N.D. | 1 |

| MDA-MB-231 | Breast | + | N.D. | 526.62 | 349.70 | 571.48 | 447.10 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| MDA-MB-468 | Breast | - | N.D. | 335.66 | 364.33 | 447.10 | 485.18 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Targeting index represents IC50 of rGel/ IC50 of immunotoxin.

N.D. represents not determined.

Effects of immunotoxins on Her2/neu-related signaling pathways

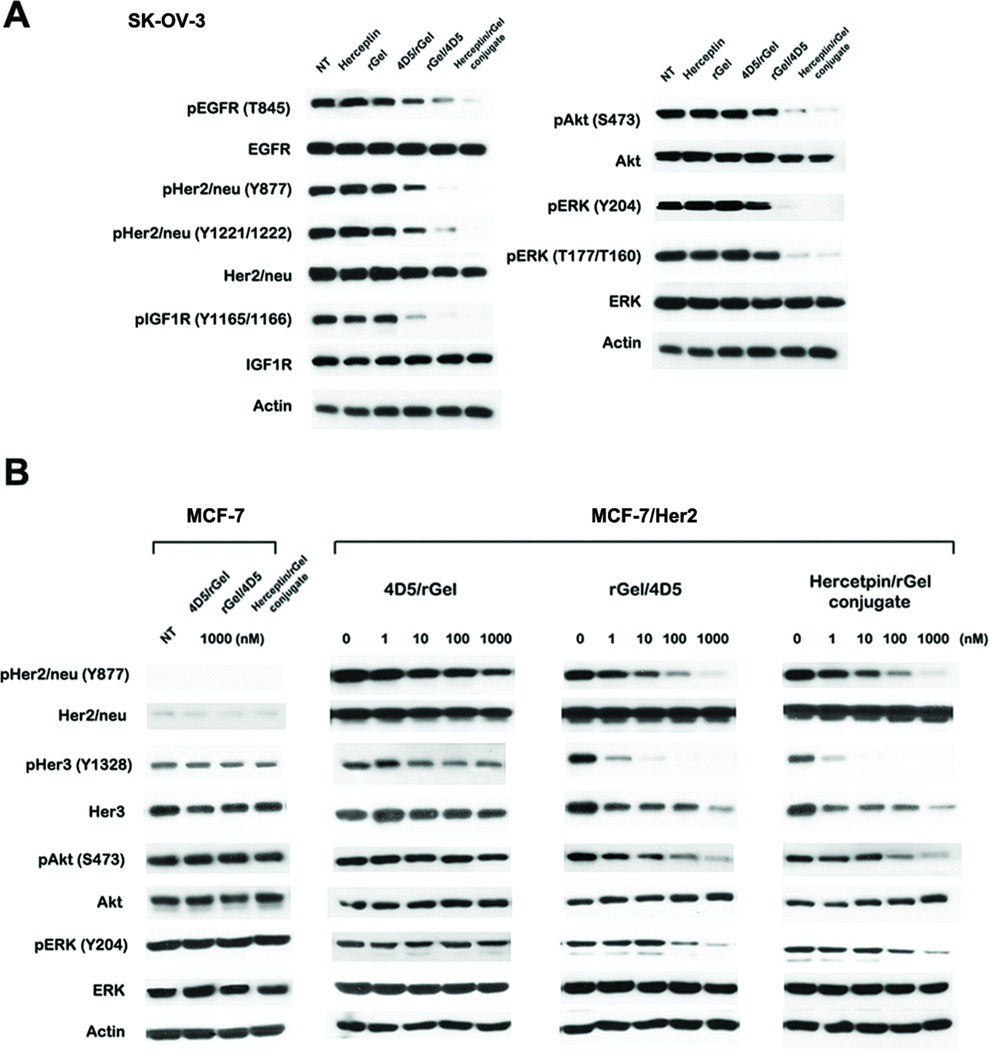

We next examined the mechanistic effects of the constructs on Her2/neu-related signaling events in SK-OV-3 cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, treatment with Herceptin/rGel conjugate and rGel/4D5 resulted in an impressive inhibition of phosphorylation of Her2/neu, EGFR, Akt and ERK, which are critical events in Her2/neu signaling cascade. In contrast, 4D5/rGel showed a comparatively reduced effect on these pathways. Treatment with these immunotoxins also resulted in reduction in the phosphorylation of IGF1R, a crosstalk partner of Her2/neu. These results suggest a link between down-regulation of IGF1R signaling and the antiproliferative effects of anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins against SK-OV-3 cells. The rGel/4D5 construct was comparatively more cytotoxic to target cells than 4D5/rGel and the improved cytotoxicity coincided with the increased effects on signal transduction.

Figure 3.

Western blot analysis of signaling pathway inhibition by the immunotoxins. (A) Analysis of signal transduction of SK-OV-3 cells treated with 100 nM drugs for 48 h. (B) Analysis of the effects of different doses of immunotoxins on the signaling pathways of MCF-7/Her2 and MCF-7 cells after 48 h of treatment. NT, no treatment.

Immunotoxin effects on Her2/neu-driven multidrug resistance

Cells overexpressing Her2/neu often display an increased requirement for the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in anchorage-independent growth (23). We compared the efficacy of various chemotherapeutic agents against MCF-7/Her2 cells and parental MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells nominally co-express Her3 and transfection results in an increased resistance to multiple chemotherapeutic agents (Supplementary Fig. S2) (24). However, we observe no cross-resistance of these cells to rGel-based immunotoxins. As shown in Fig. 3B, treatment with Herceptin/rGel conjugate and rGel/4D5 caused a dose-dependent inhibition of Her2/neu and Her3 phosphorylation, and inhibition of the downstream PI3K/Akt and Ras/ERK cascade.

Cytotoxic activity of immunotoxins against Herceptin-resistant cells

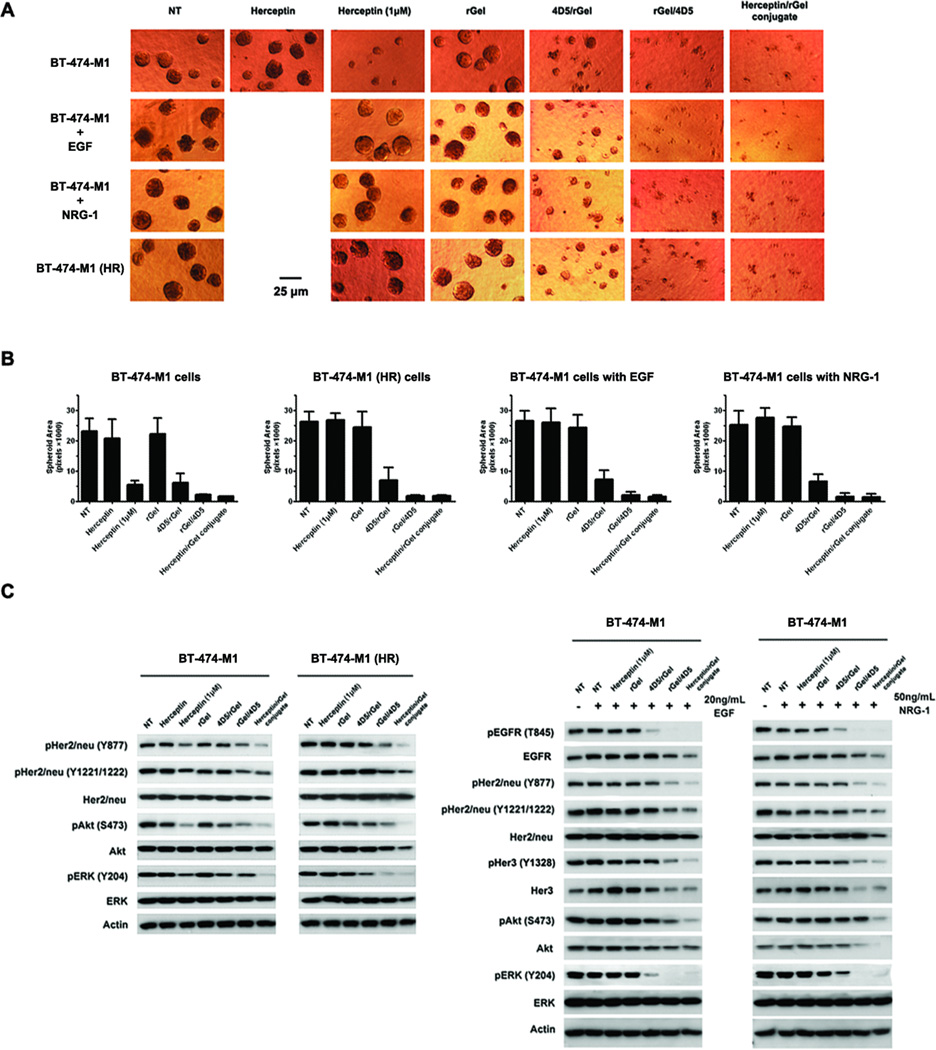

Acquired resistance to Herceptin therapy can be mediated by concomittent upregulation of Her2/neu downstream signaling pathways and can involve either constitutive Akt activation or activation from extrinsic growth factor stimulation. We developed a model of Herceptin-resistant variant BT-474-M1 (HR) cells. We also demonstrated that addition of EGF or NGR-1 growth factors to parental BT-474-M1 cells can ablate the cytotoxic response to Herceptin (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, the treatment of rGel-based immunotoxins displayed impressive cytotoxic effects against all of these Herceptin-resistant cells (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Mammary BT-474-M1 cells in anchorage-independent 3-D culture have been shown to organize into structures resembling in vivo architecture. We examined the growth of BT-474-M1 and the Herceptin-resistant cells in response to immunotoxins under 3-D growth conditions. As shown in Fig. 4A, all the immunotoxins demonstrated impressive growth inhibition against these 3-D models. Treatment with Herceptin/rGel conjugate or rGel/4D5 showed potent cytotoxic effects against both Herceptin sensitive and resistant models whereas 4D5/rGel only partially inhibited cell growth (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the immunotoxins on Herceptin-resistant cells. BT-474-M1 Herceptin-resistant cells were derived by either the continuous presence of Herceptin or by transient induction of 20 µg/mL EGF or 50 µg/mL NRG-1. Cells were treated with the drugs at a concentration of 50 nM, unless noted otherwise. (A) 3D Matrigel growth assays with BT-474-M1 parental and Herceptin-resistant cells by drug treatment for 12 days. The respective media were replenished every 3 days. Shown are representative images taken at 200× resolution. (B) Analysis of 3D Matrigel growth area of each spheroid. The calculation was performed using commercially available software ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/), and the average area presented as pixels (n > 25 spheroids). (C) Western blot analysis of signaling pathways downstream of EGFR, Her2/neu, and Her3 after 48 h of treatment. NT, no treatment.

We further investigated the signaling pathway of Her2/neu and its crosstalk receptors underlying the inhibitory potential of immunotoxins (Fig. 4C). In either Herceptin sensitive or resistant cells, treatment with immunotoxins led to a potent blockade of phosphorylation of EGFR, Her2/neu and Her3. Similar results were found for inactivation of downstream Akt and ERK in these models. As indicated, Herceptin/rGel conjugate and rGel/4D5 were the most potent at inhibiting phosphorylation of these targets while 4D5/rGel showed comparatively reduced effects.

Activity of immunotoxins against cells expressing intermediate levels of Her2/neu

Previous studies have suggested that targeting of tumors with antibodies or immunotoxins to Her2/neu may result in unexpected organ toxicities due to low levels of Her2/neu expressed on normal tissues (25, 26). We tested the immunotoxins on ZR-75-1 and BT-20 cells expressing intermediate levels of Her2/neu (~ 1.5×105 sites per cell) (27, 28). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S5A, all the immunotoxins were shown to bind to these cells, however we were unable to demonstrate immunotoxin uptake (Supplementary Fig. S5B). We were also unable to demonstrate cytotoxic effects of the immunotoxins on Her2/neu-related signaling pathways (Supplementary Fig. S5C). These results indicate that Herceptin-based immunotoxins show specific cytotoxicity to tumor cells expressing high levels of Her2/neu (> 1.5×105 sites per cell), but not cells with Her2/neu expression below this threshold level.

Immunotoxin pharmacokinetic studies

To examine the pharmacokinetic behavior of these constructs, we utilized a fluorescent molecular imaging probe (IRDye 800CW) to label the immunotoxins. The pharmacokinetics of each agent in mice was determined by quantitating immunotoxin levels in serum by photoluminescence intensity analysis (Supplementary Fig. S6). As shown in Fig. 5A, Herceptin/rGel conjugate cleared from the circulation with α and β phase half-lives of 42 min and 42.7 h respectively. These clearance kinetics appear to be similar to that of the intact Herceptin IgG (29, 30). In contrast, the monovalent 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5 constructs demonstrated relatively rapid clearance from the circulation with monophasic half-lives of 32.3 min and 34.8 min respectively. These were similar to the serum half-lives previously found for scFv-based immunotoxins in mice (13, 31).

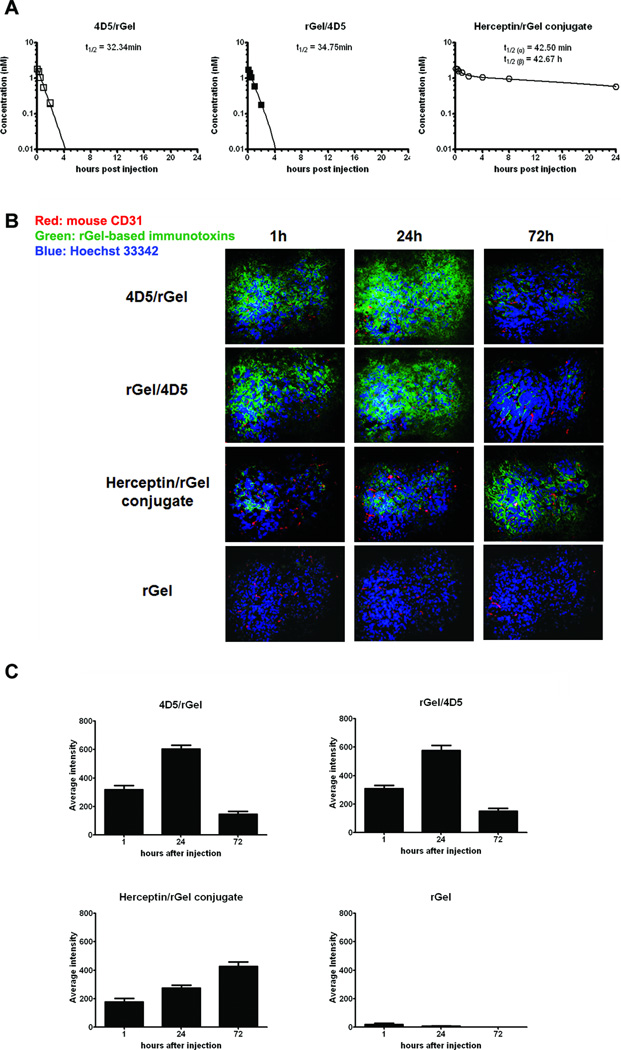

Figure 5.

In vivo pharmacokinetics and tumor distribution of anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins. (A) Pharmacokinetic analysis of immunotoxins in BALB/c mice. IRDye 800CW-labeled immunotoxins were injected intravenously into mice, and blood samples were withdrawn for photoluminescence intensity analysis using an IVIS optical imaging system. Results presented are mean ± standard deviation. (B) Immunofluorescence examination of the tumor penetration of immunotoxins relative to the tumor vasculature in SK-OV-3 tumor-bearing mice. At 1, 24, and 72 h after injection, animals were euthanized and frozen tumor sections were prepared and stained using anti-rGel antibody (green) and anti-mouse CD31 antibody (red) for murine vasculature. Hoechst 33342 was used for DNA staining. (C) Drug intensity in tumor samples was quantified with MetaMorph software, and the mean value was presented (n = 8).

Intra-tumor distribution patterns of immunotoxins

Dual immunofluorescence studies were performed to evaluate the intratumoral distribution patterns of different immunotoxins in mice bearing SK-OV-3 xenografts at different times after injection (mouse CD31, red, and rGel, green, Fig. 5B). Immunofluorescence revealed significant differences in the penetration of the immunotoxins from blood vessels into tumor with an apparent valency difference. ScFv-based immunotoxins exhibited the greatest average penetration distance from blood vessels as early as 1h after injection. Optimal, diffuse distribution occurred throughout the tumor at 24h after administration. In contrast, the intratumoral migration of the Herceptin/rGel conjugate appeared to be restricted primarily to the perivascular or intravascular areas of the tumor from 1h to 24h after administration. At 72h, the immunoconjugate had disseminated from perivascular space. Quantitative analysis (Fig. 5C) supports the observation that monovalent fusion constructs achieve maximal tumor distribution by 24 h, and clear from the tumor thereafter, and Herceptin/rGel conjugate appeared to increase in tumors over the 72h observation period. These findings suggest that high interstitial pressures in tumors may limit the initial diffusion of full-length antibodies from the blood vessels into the tumor (32, 33). In contrast, smaller fusion constructs display faster tumor uptake and clearance patterns, and appear to provide more uniform tumor penetration.

Antitumor activity of immunotoxins in xenograft models

We next evaluated the ability of anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins to inhibit the growth of SK-OV-3 tumor xenografts. As shown in Fig. 6A, a dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth was observed. For the Herceptin/rGel conjugate, total doses of 10 mg/kg caused a 20 day tumor growth delay, whereas 20 or 40mg/kg doses resulted in a >40 day growth delay until the animals were sacrificed. The groups treated with 20 or 40 mg/kg of the rGel/4D5 showed a similar pattern of tumor growth delay (~35 days). In contrast, the highest doses of 4D5/rGel (40mg/kg) showed modest (~12 days) growth delay, and no significant tumor inhibition was observed below this dose. For the rGel or Herceptin treatment groups, tumor size showed continuous progressive growth. There was no drug-induced toxicity observed in the mice at the doses of 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5 used in this experiment. At doses of 40mg/kg of Herceptin/rGel conjugate caused a 17% weight loss in the test animals (Supplementary Fig. S7).

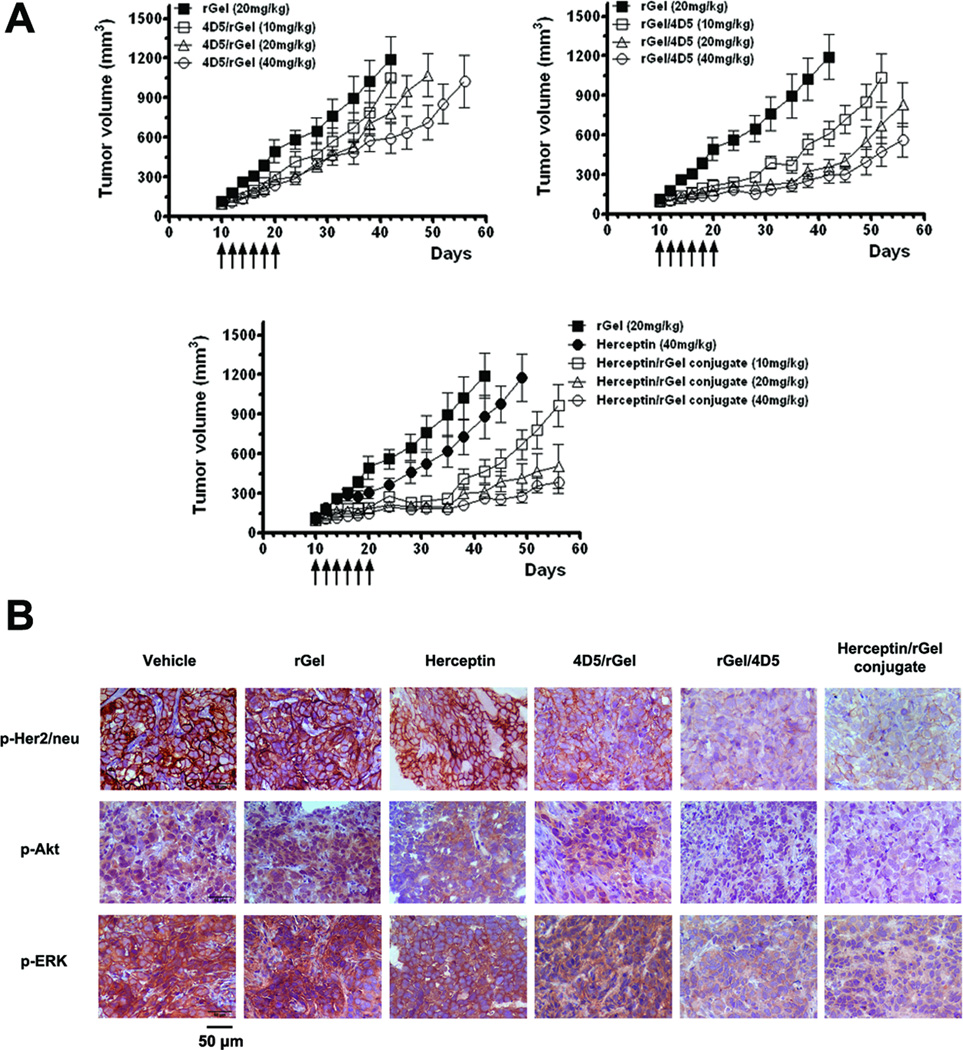

Figure 6.

In vivo study of the in vivo efficacy of immunotoxins against SK-OV-3 tumor xenografts. (A) Treatment of SK-OV-3 tumors with immunotoxins at doses of 10, 20, or 40 mg/kg, rGel at 20 mg/kg, or Herceptin at 40 mg/kg. Mean tumor volumes were calculated by W × L × H as measured by calipers. (B) Immunohistochemical analysis of phosphorylation levels of Her2/neu, Akt, and ERK from SK-OV-3 tumors obtained from immunotoxin-treated mice. Dark brown color is indicative of p-Her2/neu, p-Akt, or p-ERK. Shown are representative images taken at 400× resolution.

Immunohistochemistry studies

The ability of immunotoxins to downregulate p-Her2/neu, p-Akt and p-ERK in vivo was investigated by immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 6B). Control groups (PBS or rGel) had large area with viable SK-OV-3 cells with high levels of p-Her2/neu, p-Akt and p-ERK (dark brown areas), involving Her2/neu signaling cascade. Examining tumors from mice treated with either Herceptin or 4D5/rGel, we also found large areas of viable tumor cells with only slightly reduced levels of phosphorylation. In contrast, treatment with Herceptin/rGel conjugate or rGel/4D5 resulted in significantly reduced levels of phosphorylation of Her2/neu, Akt and ERK in tumors. These results suggest that rGel/4D5 is able to inhibit tumor growth efficiently as Herceptin/rGel conjugate, and this agent is effective in causing the downregulation of Her2/neu signaling pathways in tumors after systemic administration.

Discussion

Initial studies of anti-Her2/neu rGel-based fusion constructs focused on the characterization of target specificity of scFv, and linker design between scFv and rGel (34, 35). However, there have been no in-depth studies of the relationship of rGel-based fusion constructs compared to large chemical conjugates. This appears to be the first comprehensive examination of the characteristics of rGel-based monovalent immunotoxin design compared to bivalent immunoconjugates with respect to the impact of valency on toxin delivery, cytotoxic activity, pharmacokinetics, tumor penetration, and comparative antitumor efficacy in tumor xenograft models.

Previous studies suggest that bivalent constructs have a higher affinity and are more effective delivery vehicles for toxins when compared to monovalent fusion designs (36, 37). In contrast, our studies demonstrated that both monovalent and bivalent immunotoxins displayed comparable Her2/neu binding affinity. We did find that the bivalent conjugate was more effective compared to monovalent constructs in terms of delivery of rGel to the intracellular compartment. However, the magnitude of the increased delivery of rGel toxin did not appear to correlate with a corresponding increase in relative in vitro cytotoxicity since both Herceptin/rGel conjugate and rGel/4D5 fusion demonstrate comparable IC50 values against target cells. These studies may suggest that subcellular trafficking and delivery to the ribosomal compartment may also play pivotal roles in the overall cytotoxic potential of these agents.

Once these constructs bind to the extracellular domain, Her2/neu endocytosis may result in either recycling from endosomes back to the plasma membrane releasing the target molecule out of cells, or degradation of the protein within target cells. A comparison of 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5 orientations demonstrated that both constructs bound to tumor cells to an equivalent extent, but we found a comparatively greater level of intracellular rGel after exposure to rGel/4D5. These studies suggest that the orientation of the rGel/4D5 construct appears to more readily promote the intracellular trafficking and release of the rGel payload from the construct compared to the 4D5/rGel orientation. The mechanisms underlying the observed orientation specificity of this construct are not clear but this may be a feature of the Her2/neu target itself, a subtle characteristic of the antibody utilized or it may be related to the rGel payload employed.

Our antitumor efficacy studies demonstrated that Herceptin/rGel conjugate in the SK-OV-3 xenograft model was highly effective at this schedule and at doses ranging from 10 to 40mg/kg. Treatment with rGel/4D5 fusion at doses above 20mg/kg led to significant inhibition of tumor growth similar to that observed for the immunoconjugate. Considering the significant differences in serum half-lives observed between both agents (0.5 h vs 43 h for rGel/4D5 and Herceptin/rGel conjugate, respectively), these results suggest that the advantages of uniform and rapid tumor penetration of small molecules may outweigh the advantages of IgG molecules with higher valency or longer tumor residence times. Multiple administrations resulting in higher concentrations of rGel/4D5 with a uniform penetration into tumor tissue may be an effective strategy to overcome the limitations of the rapid clearance of these fusion constructs. In addition, the higher toxicity highlighted an additional point regarding Herceptin/rGel conjugate compared to rGel/4D5. Characteristics of rGel/4D5 such as uniform tumor penetration and rapid clearance may reduce unwanted toxicity to normal tissue in patient treatment, and may warrant consideration for continued clinical trial.

Overexpression of Her2/neu and the associated increase in Her2/neu-mediated signaling has been implicated in conferring therapeutic resistance in various tumor types (23, 24). Of critical importance is the observed potency and lack of cross-resistance of rGel-based immunotoxins against cells resistant to chemotherapeutic agents or therapeutic antibodies. The mechanistic studies demonstrated that anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins could efficiently downregulate phosphorylation of Her2/neu and its associated resulting in inhibition of both PI3K/Akt and Ras/ERK signaling pathways. Because immunotoxin treatment also impacts EGFR, Her3 and IGF1R signaling pathways, the inhibition of Her2/neu signaling may be partially associated with immunotoxin cytotoxic effects.

The Her2/neu receptor is present at low levels on a number of normal tissues including epithelia of the gastro-intestinal, respiratory and urogenital tracts, mammary tissue, cardiac and hepatic cells (38). Previous studies with anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins erb-38 or (FRP)-ETA have shown potent antitumor activity in animal models, but unexpected hepatotoxicity in patients due to the presence of low levels of Her2/neu on hepatocytes (~0.5×105 sites per cell) (25, 39, 40). The binding affinities were 27 ×10-9M for erb-38 (37) and 6.5×10−9M for (FRP5)-ETA (41). This suggests that Her2/neu targeted immunotoxins with affinities in the nanomolar range may effectively target both tumor and normal cells expressing low antigen levels. In our studies, Herceptin-based immunotoxins with subnanomolar affinity (Kd ~10−10 M) showed specific cytotoxicity to Her2/neu overexpressing cancer cells, but not cells expressing Her2/neu ≤ 1.5×105 sites per cell. Therefore, these constructs have a distinct advantage over the reported anti-Her2/neu immunotoxins, at minimizing toxicity by reducing nonspecific organ damage, suggesting the potential for clinical evaluation.

In conclusion, we developed a number of novel rGel-based immunotoxins containing bivalent and monovalent targeting antibodies. These immunotoxins showed specific activity against cancer cells expressing high level of Her2/neu. The orientation of scFv and rGel toxin did make a significant difference with the rGel/4D5 orientation displaying far better activity compared to the 4D5/rGel orientation molecule. Resistance to Herceptin or chemotherapeutic agents did not appear to impact immunotoxin efficacy. Although the Herceptin/rGel conjugate showed a long circulation half-life and impressive antitumor efficacy, the rGel/4D5 construct demonstrated excellent tumor penetration and displayed comparable cytotoxic efficacy in vitro and in vivo against tumor xenograft models. These studies provide a new and comprehensive understanding of monovalent vs. bivalent immunotoxins, and may have a significant impact on the design of future rGel-based immunotoxins.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

The cell lines SK-BR-3, SK-OV-3, NCI-N87, Calu-3, A-431, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. The cell MDA-MB-435S (Her2/neu transfection) and BT-474-M1 were supplied from Dr. Dihua Yu (UT MDACC, Houston, TX). The cell MCF-7/Her2, MDA-MB-453 and MDA-MB-361 were from Dr. Zhen Fan (UT MDACC, Houston, TX). The cell ZR-75-1 and BT-20 were provided from Dr. Anette Weyergang (Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway). The Herceptin-resistant BT-474-M1 (HR) cell line was derived from the BT-474-M1 cells after selection in the presence of 1 µM Herceptin. The cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, plus 1mM antibiotics.

Preparation of Herceptin/rGel conjugate

The details for the generation of antibody/rGel chemical conjugates have been published elsewhere (30). For the Herceptin/rGel conjugate, rGel was covalently linked to Herceptin using the heterobifunctional cross-linking reagent SPDP.

Preparation of 4D5-based fusion constructs

The sequence of scFv 4D5 was derived from the published Herceptin light and heavy-chain variable domain sequences (22). We generated fusion constructs with rGel in two orientations (designated 4D5/rGel and rGel/4D5. The immunotoxins were then expressed in E. coli AD494 (DE3) pLysS and purified by IMAC as previously reported (34).

Determination of binding affinity

Evaluation of Her2/neu binding affinity was measured by ELISA: 96-well ELISA plates were coated with Her2/neu ECD. Then, a series diluted immunotoxins were added to each well. Anti-rGel antibody and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was used as a tracer.

Evaluation of cellular Her2/neu binding by flow cytometry was performed on Her2/neu positive (SK-OV-3 or BT-474-M1) and negative (MDA-MB-468) cells. Cells were incubated with 25nM immunotoxins at 4°C. After washes, anti-rGel antibody was added, which was chased by FITC-labeled secondary antibody. Detection of bound immunotoxins was performed by flow cytometry on XL-MCL Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

Reticulocyte lysate in vitro translation assay

The n-glycosidase activity of the rGel component of the various constructs was assessed using a cell-free protein synthesis system by rabbit reticulocytes lysate kit (Promega) (20).

Internalization analysis

Immunofluorescence-based internalization studies were performed on SK-OV-3, BT-474-M1 and MDA-MB-468 cells (34). After drug treatment, the cells were subjected to anti-rGel antibody (FITC-conjugated secondary antibody). Nuclei were counterstained with propidium iodine. Visualization of immunofluorescence was performed with a confocal laser scanning microscope Zeiss LSM510 (Carl Zeiss).

Intracellular behavior study

The intracellular behavior of each immunotoxin was analyzed on SK-OV-3 and BT-474-M1 cells. After incubation for various times, the cells were treated with acidic Glycine Buffer (pH 2.5) to strip cell-surface-bound proteins, and lysed in RIPA Lysis Buffer. Cytosolic fractions were analyzed by western blot using anti-rGel antibody. Data are presented as the relative density of total rGel signal or free rGel signal normalized to β-actin. Relative protein quantification was done using AlphaEaseFCTM software (Alpha Innotech).

In vitro cytotoxicity assays

Log-phase cells in monolayer culture were treated with various immunotoxins or rGel at 37 °C for 72 h, and the cell viability was determined by using crystal violet staining method (20).

Impact on cell signaling pathways

Western blot analysis was applied to evaluate the effects of immunotoxins on signaling pathways in the cells. After 48h treatment, cells were lysed and analyzed by western blot with antibodies recognizing Her2/neu (Cell Signaling Technology), p-Her2/neu (Tyr877), p-Her2/neu (Tyr 1221/1222), EGFR, p-EGFR (Thr845), Her3, p-Her3 (Tyr1328), IGF1R, p-IGF1R (Tyr 1165/1166), Akt, p-Akt (Ser473), ERK, p-ERK (Thr 177/Thr 160) (Santa Cruz Biotechonology), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Three-dimensional cell culture

BT-474-M1 and its derived Herceptin-resistant cells were placed on top of laminin-rich matrix (Matrigel, BD Biosciences), and maintained in DMEM medium with 5% Matrigel (42), with or without the presence of 20ng/mL EGF or 50ng/mL NRG-1. Cells were treated with each drug on day 3, and culture medium was refreshed every 3 days. The analysis of 3D Matrigel growth was evaluated on day 12 for more than 25 spheroids under each condition. ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) was used for the analysis of spheroid area from phase contrast-photos.

Pharmacokinetic studies

Immunotoxins were labeled with infrared dye reagent IRDye 800CW (Li-Cor Biosciences). Balb/c mice were i.v. injected with 2nM IRDye800 equivalent of fluorescent probes, and blood samples were obtained at different times post injection (3min, 15min, 30min, 1h, 2h, 4h, 8h and 24h). The photoluminescence intensity of the samples was quantitated using an IVIS optical imaging system (Xenogen Corp.). The circulation half-life was calculated by fitting the data to a one-phase exponential decay equation for monovalent fusions and a two-phase exponential decay equation for bivalent conjugate (GraphPad Prism).

Tumor penetration studies

Balb/c nude mice were injected s.c. with SK-OV-3 cells (5×106 cells/mouse). When the tumor reached ~150 mm3, animals were i.v. injected with 250 µg rGel or monovalent immunotoxins (4D5/rGel or rGel/4D5), or 500 µg Herceptin/rGel conjugate. After 1, 24, 72h, the mice were sacrificed and tumor samples were collected and frozen for section slides. The slides were incubated with anti-rGel antibody (FITC-conjugated secondary antibody), and anti-mouse CD31 antibody (phycoerythrin-conjugated secondary antibody), and were further subjected to nuclear counterstaining with Hoechst 33342. Immunofluorescence observation was performed under an Axioplan 2 imaging microscopy (Carl Zeiss). Quantitative analysis on the tissue slides were measured by MetaMorph software (Molecular Device).

In vivo efficacy studies

Balb/c nude mice inoculated with SK-OV-3 cells were assigned into treatment groups, such that by day 10 post inoculation, the mean tumor volume for each group was ~100 mm3. Mice were treated every other day for six times by i.v. injection of PBS, rGel (20mg/kg), Herceptin (40mg/kg), and various immunotoxins (4D5/rGel, rGel/4D5 and Herceptin/rGel conjugate) (10, 20 and 40mg/kg). All treatment groups consisted of 5 animals per group, and tumor size was monitored twice weekly using caliper measurement.

Immunohistochemistry

SK-OV-3 xenografted mice were treated with PBS, 20mg/kg of rGel, 4D5/rGel or rGel/4D5, 40mg/kg of Herceptin or Herceptin/rGel conjugate. Tumor samples were collected and fixed in 4% formaldehyde and paraffin embedded. The immunohistochemistry was applied with antibodies against p-Her2/neu (Tyr877), p-ERK (Thr 177/Thr 160) (Santa Cruz Biotechonology) and p-Akt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology). Antibody binding was revealed by addition of 3.3’-diaminobenzidine substrate. Tissues were further counterstained with hematoxylin and examined using a Nikon Eclipse TS-100 microscope (Nikon).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Xin Li of University of Kentucky for assistance with immunohistochemical study. This research work was conducted, in part, by the Clayton Foundation for Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Scholl S, Beuzeboc P, Pouillart P. Targeting HER2 in other tumor types. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 1):S81–S87. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_1.s81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniele L, Sapino A. Anti-HER2 treatment and breast cancer: state of the art, recent patents, and new strategies. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2009;4:9–18. doi: 10.2174/157489209787002489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohlmann PR, Mayer IA, Mernaugh R. Resistance to Trastuzumab in Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7479–7491. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy CG, Fornier M. HER2-positive breast cancer: beyond trastuzumab. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24:410–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann U. Recombinant antibody fragments and immunotoxin fusions for cancer therapy. In Vivo. 2000;14:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain KK. Use of bacteria as anticancer agents. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2001;1:291–300. doi: 10.1517/14712598.1.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maier LA, Xu FJ, Hester S, Boyer CM, McKenzie S, Bruskin AM, et al. Requirements for the internalization of a murine monoclonal antibody directed against the HER-2/neu gene product c-erbB-2. Cancer Res. 1991;51:5361–5369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez GC, Boente MP, Berchuck A, Whitaker RS, O'Briant KC, Xu F, et al. The effect of antibodies and immunotoxins reactive with HER-2/neu on growth of ovarian and breast cancer cell lines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:228–232. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90918-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckman RA, Weiner LM, Davis HM. Antibody constructs in cancer therapy: protein engineering strategies to improve exposure in solid tumors. Cancer. 2007;109:170–179. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain M, Venkatraman G, Batra SK. Optimization of radioimmunotherapy of solid tumors: biological impediments and their modulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1374–1382. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krauss WC, Park JW, Kirpotin DB, Hong K, Benz CC. Emerging antibody-based HER2 (ErbB-2/neu) therapeutics. Breast Dis. 2000;11:113–124. doi: 10.3233/bd-1999-11110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennell CA, Erickson HA. Designing immunotoxins for cancer therapy. Immunol Res. 2002;25:177–191. doi: 10.1385/IR:25:2:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazor Y, Noy R, Wels WS, Benhar I. chFRP5-ZZ-PE38, a large IgG-toxin immunoconjugate outperforms the corresponding smaller FRP5(Fv)-ETA immunotoxin in eradicating ErbB2-expressing tumor xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreitman RJ. Recombinant toxins for the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2003;5:44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiter Y. Recombinant immunotoxins in targeted cancer cell therapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;81:93–124. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(01)81003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams GP, Tai MS, McCartney JE, Marks JD, Stafford WF, III, Houston LL, et al. Avidity-mediated enhancement of in vivo tumor targeting by single-chain Fv dimers. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1599–1605. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bera TK, Onda M, Brinkmann U, Pastan I. A bivalent disulfide-stabilized Fv with improved antigen binding to erbB2. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:475–483. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bera TK, Viner J, Brinkmann E, Pastan I. Pharmacokinetics and antitumor activity of a bivalent disulfide-stabilized Fv immunotoxin with improved antigen binding to erbB2. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4018–4022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yee ST, Okada Y, Ogasawara K, Omura S, Takatsuki A, Kakiuchi T, et al. MHC class I presentation of an exogenous polypeptide antigen encoded by the murine AIDS defective virus. Microbiol Immunol. 1997;41:563–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenblum MG, Cheung LH, Liu Y, Marks JW., III Design, expression, purification, and characterization, in vitro and in vivo, of an antimelanoma single-chain Fv antibody fused to the toxin gelonin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3995–4002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossann M, Li Z, Shi Y, Kreilinger U, Buttner J, Vogel PD, et al. Novel immunotoxin: a fusion protein consisting of gelonin and an acetylcholine receptor fragment as a potential immunotherapeutic agent for the treatment of Myasthenia gravis. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;46:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter P, Presta L, Gorman CM, Ridgway JB, Henner D, Wong WL, et al. Humanization of an anti-p185HER2 antibody for human cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4285–4289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermanto U, Zong CS, Wang LH. ErbB2-overexpressing human mammary carcinoma cells display an increased requirement for the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway in anchorage-independent growth. Oncogene. 2001;20:7551–7562. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knuefermann C, Lu Y, Liu B, Jin W, Liang K, Wu L, et al. HER2/PI-3K/Akt activation leads to a multidrug resistance in human breast adenocarcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:3205–3212. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai-Scherf LH, Villa J, Pearson D, Watson T, Liu E, Willingham MC, et al. Hepatotoxicity in cancer patients receiving erb-38, a recombinant immunotoxin that targets the erbB2 receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2311–2315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardinale D, Colombo A, Torrisi R, Sandri MT, Civelli M, Salvatici M, et al. Trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity: clinical and prognostic implications of troponin I evaluation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3910–3916. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLarty K, Cornelissen B, Scollard DA, Done SJ, Chun K, Reilly RM. Associations between the uptake of 111In-DTPA-trastuzumab, HER2 density and response to trastuzumab (Herceptin) in athymic mice bearing subcutaneous human tumour xenografts. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:81–93. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0923-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordstrom JL, Gorlatov S, Zhang W, Yang Y, Huang L, Burke S, et al. Anti-tumor activity and toxicokinetics analysis of MGAH22, an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody with enhanced Fc-gamma receptor binding properties. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R123. doi: 10.1186/bcr3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis Phillips GD, Li G, Dugger DL, Crocker LM, Parsons KL, Mai E, et al. Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9280–9290. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenblum MG, Shawver LK, Marks JW, Brink J, Cheung L, Langton-Webster B. Recombinant immunotoxins directed against the c-erb-2/HER2/neu oncogene product: in vitro cytotoxicity, pharmacokinetics, and in vivo efficacy studies in xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:865–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benhar I, Pastan I. Characterization of B1(Fv)PE38 and B1(dsFv)PE38: single-chain and disulfide-stabilized Fv immunotoxins with increased activity that cause complete remissions of established human carcinoma xenografts in nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1023–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yokota T, Milenic DE, Whitlow M, Schlom J. Rapid tumor penetration of a single-chain Fv and comparison with other immunoglobulin forms. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3402–3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain RK, Baxter LT. Mechanisms of heterogeneous distribution of monoclonal antibodies and other macromolecules in tumors: significance of elevated interstitial pressure. Cancer Res. 1988;48:7022–7032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao Y, Marks JD, Marks JW, Cheung LH, Kim S, Rosenblum MG. Construction and characterization of novel, recombinant immunotoxins targeting the Her2/neu oncogene product: in vitro and in vivo studies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8987–8995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y, Marks JD, Huang Q, Rudnick SI, Xiong C, Hittelman WN, et al. Single-chain antibody-based immunotoxins targeting Her2/neu: design optimization and impact of affinity on antitumor efficacy and off-target toxicity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:143–153. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams GP, Schier R, McCall AM, Crawford RS, Wolf EJ, Weiner LM, et al. Prolonged in vivo tumour retention of a human diabody targeting the extracellular domain of human HER2/neu. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1405–1412. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bera TK, Onda M, Brinkmann U, Pastan I. A bivalent disulfide-stabilized Fv with improved antigen binding to erbB2. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:475–483. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brand FX, Ravanel N, Gauchez AS, Pasquier D, Payan R, Fagret D, et al. Prospect for anti-her2 receptor therapy in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:715–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maurer-Gebhard M, Schmidt M, Azemar M, Altenschmidt U, Stocklin E, Wels W, et al. Systemic treatment with a recombinant erbB-2 receptor-specific tumor toxin efficiently reduces pulmonary metastases in mice injected with genetically modified carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2661–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azemar M, Djahansouzi S, Jager E, Solbach C, Schmidt M, Maurer AB, et al. Regression of cutaneous tumor lesions in patients intratumorally injected with a recombinant single-chain antibody-toxin targeted to ErbB2/HER2. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;82:155–164. doi: 10.1023/b:brea.0000004371.48757.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wels W, Harwerth IM, Mueller M, Groner B, Hynes NE. Selective inhibition of tumor cell growth by a recombinant single-chain antibody-toxin specific for the erbB-2 receptor. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6310–6317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.