Abstract

Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels are activated by stimuli as diverse as heat, cold, noxious chemicals, mechanical forces, hormones, neurotransmitters, spices, and voltage. Besides their presumably similar general architecture, probably the only common factor regulating them is phosphoinositides. The regulation of TRP channels by phosphoinositides is complex. There is a large number of TRP channels where phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2 or PIP2], acts as a positive cofactor, similarly to many other ion channels. In several cases however, PI(4,5)P2 inhibits TRP channel activity, sometimes even concurrently with the activating effect. This review will provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on regulation of TRP channels by membrane phosphoinositides.

1. Introduction

Membrane phospholipids had generally been viewed as passive media that ion channels are embedded in. The beginning of the end of this view was probably marked by Donald Hilgemann’s finding that the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchangers and the cardiac KATP channels requires the presence of PI(4,5)P2 for activity (Hilgemann and Ball, 1996). There were sporadic publications before this article reporting effects of PI(4,5)P2 on channels or transporters, see (Huang, 2007) for references, but it was Hilgemann’s seminal publication that sparked the explosion of interest in this lipid in the context of ion channel regulation. In 1998 high profile articles from four different laboratories extended PI(4,5)P2 regulation to several inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channels (Baukrowitz et al., 1998; Huang et al., 1998; Shyng and Nichols, 1998; Sui et al., 1998). This was followed by an ever-growing number of publications showing that a largely unexpected number and variety of ion channels require PI(4,5)P2 for activity. By now it seems that phosphoinositides are general regulators of most mammalian ion channels (Hilgemann et al., 2001; Suh and Hille, 2008; Gamper and Rohacs, 2012).

The first two papers on the phosphoinositide regulation of TRP channels were published in 2001. Chuang et al reported that PI(4,5)P2 tonically inhibits the heat- and capsaicin-activated TRPV1 channels, and breakdown of this lipid upon PLC activation relieves this inhibition leading to potentiation of TRPV1 activity by pro-inflammatory agents such as bradykinin (Chuang et al., 2001). Another article found that PI(4,5)P2 inhibits the drosophila TRPL channel in excised patches (Estacion et al., 2001). Since the whole subfamily of mammalian TRPC-s are activated downstream of PLC, PI(4,5)P2 being a general inhibitor of TRP channels was a highly attractive hypothesis. For a while, the general view was that TRP channels are inhibited by PI(4,5)P2. This started to change when paper after paper showed that PI(4,5)P2 activates other TRP channels, such as TRPM7 (Runnels et al., 2002), TRPM5 (Liu and Liman, 2003), TRPM8 (Liu and Qin, 2005; Rohacs et al., 2005), TRPV5 (Lee et al., 2005; Rohacs et al., 2005) and TRPM4 (Nilius et al., 2006) similar to most other ion channel families. The number TRP channels that are influenced by phosphoinositides are growing ever since. It is quite likely, that at least in the 3 major families, most, if not all members are regulated by phosphoinositides, with the majority showing a dependence on some of these lipids for activity, in most cases PI(4,5)P2.

There have been several reviews on the topic published in recent years (Hardie, 2007; Qin, 2007; Rohacs and Nilius, 2007; Nilius et al., 2008; Rohacs, 2009). The field progressed considerably since; here I will give a comprehensive overview of the literature, incorporating novel findings since the last reviews, but trying to systematically describe earlier results too. Due to space restrictions, in several cases I refer to earlier reviews for details where I was not aware of new publications on PI(4,5)P2 regulation. I will also have no room for extensive discussions on some of the more complex or controversial regulation themes. I will provide a brief overview of the general function of the individual channels before discussing their regulation by phosphoinositides. In some cases the function of the channel is more complicated, or debated, so these short summaries are unavoidably over-simplifications. The reader is referred to other chapters of this handbook for more detailed information on individual TRP channels.

2. Phosphoinositide signaling

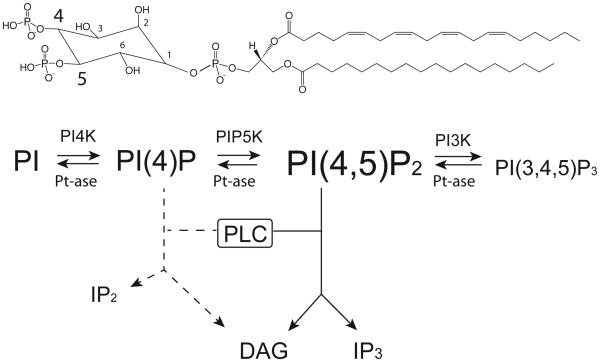

PI(4,5)P2 is generated by two phosphorylation steps from phosphatidylinositol (PI) (Fig. 1). Phosphoinositide 4 kinases (PI4K) catalyze the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate [PI(4)P], which is further phosphorylated by phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5 kinases (PIP5K). Phosphoinositide 3 kinases (PI3K) add a phosphate to the 3 position in the inositol ring, and form either PI(3,4)P2 or PI(3,4,5)P3, which are second messengers in signaling by various growth factors. Phospholipase C (PLC) enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 and the formation of the two classical second messengers inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). PI(4)P is also known to be the substrate for PLC enzymes, even though most PLCs are less active in hydrolyzing this lipid than PI(4,5)P2. PLCβ isoforms (PLCβ1-4) are activated by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) that couple to the Gq family of heterotrimeric G-proteins. PLCγ-s (PLCγ1 and 2) are activated by receptor tyrosine kinases. PLCδ-s (PLCδ1, δ3 and δ4) do not have obvious activators; these isoforms are the most sensitive to Ca2+ among the three classical PLC groups, and they can be activated by Ca2+ influx alone (Allen et al., 1997; Lukacs, 2013). In addition to the classical PLC-s, newer isoforms have also been cloned more recently (PLCη1 and η2 and PLCε); their regulation is less well understood (Fukami et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Phosphoinositide metabolism

Besides their precursor function, and regulation of ion channels, phosphoinositides are important regulators of cytoskeletal organization, membrane traffic, and general cellular architecture (Saarikangas et al., 2010; Shewan et al., 2011). These other functions of phosphoinositides may also affect ion channel activity, see the regulation of TRPV1 and TRPC channels.

3. Methods to study phosphoinositide regulation

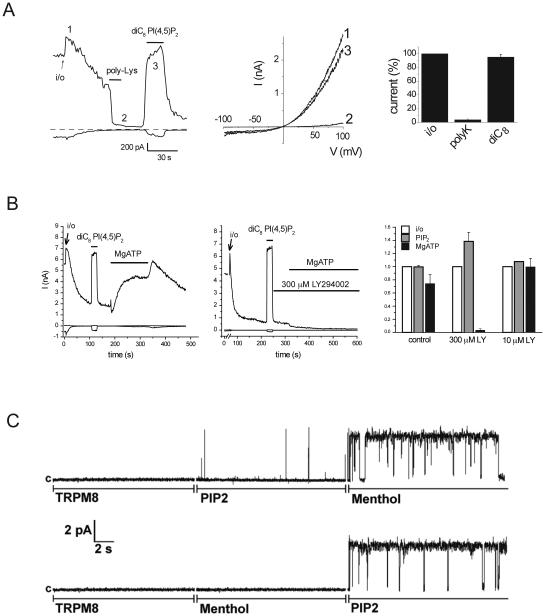

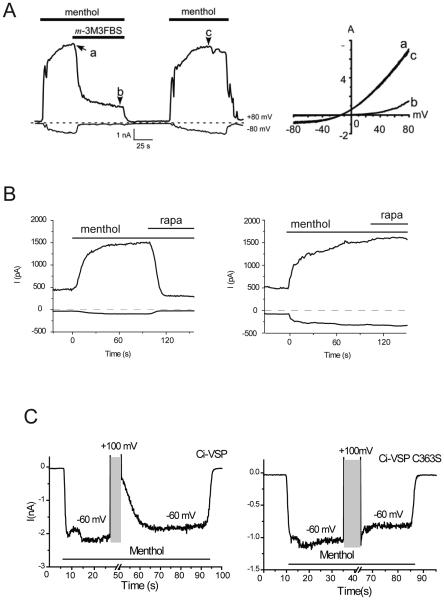

The methods to study phosphoinositide regulation of ion channels have been reviewed extensively in several articles (Rohacs et al., 2002; Rohacs and Nilius, 2007; Suh and Hille, 2008; Gamper and Rohacs, 2012). Here I will give a brief overview of the various techniques to study phosphoinositide regulation. Figures 2 and 3 show a compilation of experimental data using a number of techniques discussed here, all demonstrating the dependence of the activity of TRPM8 on PI(4,5)P2.

Figure 2.

Activation of TRPM8 excised inside-out patches and planar lipid bilayers. A. Representative trace for recording of TRPM8 currents in large patches in Xenopus oocytes with 500 μM menthol in the patch pipette from (Rohacs et al., 2005). Left panel shows currents at −100 and +100 mV, from ramp protocol shown in the middle. Application of 30 μg/ml poly-Lysine and 50 μM diC8 PI(4,5)P2 are indicated with the horizontal lines. B. Similar excised inside out patch measurement from (Yudin et al., 2011), demonstrating the effect of 2 mM MgATP and LY294002. Right panel shows summary for 300 μM LY294002 that inhibits both PI4K and PI3K, and for 10 μM LY294002 that selectively inhibits PI3K. C. Representative measurement in planar lipid bilayers with purified TRPM8 from (Zakharian et al., 2009). In the upper trace first the TRPM8 protein shows no activity in the absence of menthol and PI(4,5)P2, then diC8 PI(4,5)P2 is applied, then menthol, in the continuous presence of PI(4,5)P2. In the bottom trace menthol and PI(4,5)P2 is applied in the reverse order.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of TRPM8 by reduction of PI(4,5)P2 in intact cells, right panels in A,B and C show cartoon of the method used. A. Whole cell patch clamp measurement from (Daniels et al., 2009) showing inhibition of menthol induced RPM8 currents by the pharmacological PLC activator m-3M3FBS. B. Inhibition of TRPM8 activity by the rapamycin inducible 5-phosphatase from (Varnai et al., 2006). C. Inhibition of TRPM8 activity by depolarization-induced depletion of PI(4,5)P2 in ciVSP expressing cells from (Yudin et al., 2011). Left panel shows a measurement with the active ciVSP, middle panel with an inactive mutant.

3.1 Excised inside-out patches

Perhaps the most often used technique to demonstrate the effects of phosphoinositides is the excised inside-out patch configuration of the patch clamp technique. A common characteristic of PI(4,5)P2 dependent ion channels is run-down of channel activity upon excision into an ATP free solution, see Figure 2A for an example on TRPM8. Run-down of PI(4,5)P2 dependent ion channels is caused by dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P by lipid phosphatases associated with the patch membrane. Agents that chelate endogenous PI(4,5)P2 and other phosphoinositides such as poly-Lysine (Fig. 2A) or anti PI(4,5)P2 antibody accelerate run-down (Fig. 2A). When PI(4,5)P2 is applied to the patch, it reactivates PI(4,5)P2 dependent ion channels (Fig 2A and B). Natural phosphoinositides have a combination of long acyl chains, arachidonyl-stearyl (AASt) being the most common. These natural lipids or their synthetic versions such as dipalmitoyl PI(4,5)P2 form micelles in aqueous solutions, and activate channels relatively slowly, and their effects are usually long lasting, since they accumulate in the patch membrane (Rohacs et al., 2002). Short acyl chain DiC8 phosphoinositides are easier to handle, and their effect washes out quickly (Fig. 2A), making it possible to test multiple compounds in one patch, which can be useful for constructing dose-response curves or testing phosphoinositide specificity profiles.

Exogenously applied lipids may cause unwanted side effects (Hilgemann, 2012). The effects of endogenous phosphoinositides however can also be studied in excised patches, by applying MgATP, which activates endogenous lipid kinases in the patch membrane (Hilgemann and Ball, 1996; Sui et al., 1998). Figure 2B shows an example, where MgATP re-activated the PI(4,5)P2 dependent TRPM8 channels, and the effect was inhibited by LY294002 at concentrations where it inhibits PI4K-kinases, but not at lower concentrations where it acts selectively on PI3-Kinases.

Applying PI(4,5)P2 directly to the patch membrane is still the state of the art method technique to demonstrate direct activation by the lipid. Excised patches however may contain many different proteins, including the lipid phosphatases and kinases just described, and cytoskeletal elements (Sachs, 2010), which may affect channel activity (Furukawa et al., 1996). Thus to demonstrate a direct effect of phosphoinositides beyond doubt, techniques based on purified proteins are needed.

3.2 Techniques on purified channel proteins

Biochemical binding assays have also been used to demonstrate direct binding of channel proteins to PI(4,5)P2. There is a plethora of specific techniques; most of them use isolated cytoplasmic fragments of ion channels (Rohacs, 2009; Gamper and Rohacs, 2012). Conceptually, if PI(4,5)P2 acts directly on the channels, it has to bind to it. If binding of PI(4,5)P2 is demonstrated, however, it does not prove that the biological effect of PI(4,5)P2 happens through that binding. PI(4,5)P2 has a very high charge density, thus it could bind to positively charged protein surfaces, even if those do not face the plasma membrane in situ.

Perhaps the most convincing evidence for a direct effect of PI(4,5)P2 on a channel is to study its effect on purified proteins in an artificial membrane (Zakharian et al., 2009; D'Avanzo et al., 2010; Zakharian et al., 2010, 2011; Cao et al., 2013b). Figure 2C shows an example of activation by PI(4,5)P2 on the purified TRPM8 protein. The advantage of using reconstituted protein that it is probably the strongest evidence for a direct functional of the lipid an ion channel. The disadvantage is that the artificial membranes have different lipid composition from that of the plasma membrane, and other lipids may modify the effects of phosphoinositides (Cheng et al., 2011).

3.3 Pharmacological tools in intact cells or whole cell patch clamp

The major pathway most likely to decrease PI(4,5)P2 levels in intact cells is activation of PLC, which often inhibits PI(4,5)P2 sensitive channels. PLC can be activated by G-protein coupled receptors (PLCβ), Receptor tyrosine kinases (PLCγ), Ca2+ influx through the channel itself (PLCδ) or a chemical activator m-3M3FBS (Fig. 3A). Upon activation of PLC it is often hard to differentiate if the inhibitory effect is due to PI(4,5)P2 depletion, or other downstream pathways such as PKC.

PI4K can be inhibited by high concentrations of PI3K inhibitors such as LY294002 or wortmannin. These compounds slowly deplete PI(4)P and PI(4,5)P2 and may inhibit phosphoinositide sensitive ion channels (Rohacs et al., 2005). Since long treatments are necessary to significantly reduce phosphoinositide levels, many cellular processes may be affected, compounding interpretation. PI4K inhibitors have also been used to inhibit recovery from channel inhibition after PLC activation (Suh and Hille, 2002; Liu et al., 2005). New more specific PI4K inhibitors are being developed, but not yet commercially available (Altan-Bonnet and Balla, 2012).

3.4 Inducible phosphatases in intact cells or whole cell patch clamp

Over-expression of constitutively active lipid kinases and phosphatases can be used to modify phosphoinositide levels, but those again exert long-term effects on many cellular functions. For this reason various inducible phosphatases have been developed to rapidly and specifically dephosphorylate PI(4,5)P2. One group of these tools is based on the rapamycin-induced heteromerization of FKBP12 and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Using this system, a lipid phosphatase located in the cytoplasm can be translocated to the plasma membrane with rapamycin, where it dephosphorylates PI(4,5)P2 to form PI(4)P (Suh et al., 2006; Varnai et al., 2006). If the activity of an ion channel depends on PI(4,5)P2, but PI(4)P cannot activate it, translocation of the 5-phosphatase is expected to inhibit it (Fig. 3B). A novel version of this system was recently developed, where both a 5 and a 4 phosphatase was linked to FKBP12. This construct, pseudojanin, dephosphorylates both PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P in response to rapamycin (Hammond et al., 2012). With the combination of these tools, the effects of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P can be differentiated.

Voltage sensitive phosphatases from ciona intestinalis (ciVSP) or danio rerio (drVSP) are alternative tools to dephosphorylate PI(4,5)P2 (Okamura et al., 2009). These naturally occurring membrane proteins remove the 5 phosphate from PI(4,5)P2 in response to depolarizing voltages. They also dephosphorylate PI(3,4,5)P3, but the concentration of this lipid in non-stimulated cells is essentially zero, thus these tools can be assumed to selectively deplete PI(4,5)P2 in most cases. The advantage of voltage sensitive phosphatases over the rapamycin-inducible systems is that PI(4,5)P2 depletion is quickly reversible, and it is much easier to induce graded responses either with smaller or shorter depolarizing pulses. Generally, the inducible phosphatases are considered the most specific tools in intact cells to selective decrease PI(4,5)P2 levels, and they have been used to systematically clarify the role of phosphoinositides in regulation of various mammalian ion channel families (Suh et al., 2010; Kruse et al., 2012). The inducible phosphatases are not physiological however.

Overall, all of the tools have advantages and disadvantages, only the combined use of them can bring meaningful conclusion. For Kir and KCNQ channels and some TRP channels, such TRPM8 (Figures 2 and 3) essentially all tools support the same conclusion, channel activity depends on PI(4,5)P2. There are several TRP channels however where the different tools support seemingly opposite conclusions. In some cases most data can be explained with a congruent model, in some other cases it cannot. Regulation of TRP channels by phosphoinositides is more complex than Kir and KCNQ channels, and in many cases future work is required to clarify the picture.

4. General principles of phosphoinositide regulation

We have extensively discussed this topic in two previous reviews in the context of TRP channels (Rohacs, 2007, 2009). The following is a brief summary of some of the key concepts, some of which were worked out on the best studied PI(4,5)P2 sensitive ion channel families Kir channels and voltage gated KCNQ K+ channels (Kv7.x).

4.1 How do phosphoinositides interact with ion channels?

Kir channels were the first ion channel family where PI(4,5)P2 dependence was demonstrated. The molecular mechanism of PI(4,5)P2 activation is best understood on these channels. The general view from the beginning was that the negatively charged head-group of PI(4,5)P2 interacts with positively charged residues in the cytoplasmic domains of the channels (Fan and Makielski, 1997; Huang et al., 1998). Thorough mutagenesis studies later mapped the positively charged residues mainly to the larger C-terminal domain, but PI(4,5)P2 interacting residues in the smaller N-terminus were also found (Lopes et al., 2002). Several homology models have been built based on partial crystal structures (Rosenhouse-Dantsker and Logothetis, 2007), when finally in 2011 two co-crystal structures with PI(4,5)P2 were published (Hansen et al., 2011; Whorton and MacKinnon, 2011). Quite remarkably, the original idea that the interaction of the lipid’s head group with the cytoplasmic domain(s) of the channel leads to a conformation change opening the channel (Fan and Makielski, 1997), was essentially confirmed, needless to say at a much higher molecular resolution (Hansen et al., 2011; Whorton and MacKinnon, 2011). Since the overall homology of TRP channels between sub-families is negligible outside the transmembrane domains, it is unlikely that such a conserved PI(4,5)P2 interaction binding site is responsible for the effects of PI(4,5)P2 on TRP channels. Accordingly, a variety of C- or N-terminal segments have been proposed as PI(4,5)P2 interacting sites in different TRP channels (Rohacs et al., 2005; Nilius et al., 2006; Brauchi et al., 2007; Klein et al., 2008; Garcia-Elias et al., 2013).

4.2 Phosphoinositide specificity

Kir channels have diverse specificities for phosphoinositides (Rohacs et al., 2003). Similarly, some TRP channels such as TRPM8 (Rohacs et al., 2005) or TRPV6 (Thyagarajan et al., 2008) are activated relatively specifically by PI(4,5)P2, whereas others, like TRPV1 are activated by many different phosphoinositides (Lukacs et al., 2007).

To put the effects of various phosphoinositides in context, we need to consider their in situ concentrations. PI(4,5)P2 constitutes up to 1 % of the phospholipids in the plasma membrane; PI(4)P is found in comparable quantities (Fruman et al., 1998). Their precursor PI constitutes up to 10% of membrane lipids (Fruman et al., 1998), but it has no effect on most PI(4,5)P2 sensitive channels, and its concentration is not expected to change significantly upon PLC activation. PI(3,4,5)P2 and PI(3,4)P2, the products of PI3K may also activate some PI(4,5)P2 sensitive ion channels, but their concentrations in the plasma membrane do not reach higher than 0.1 % even in stimulated cells (Fruman et al., 1998), thus their effect is likely to be overridden by the much higher concentration of PI(4,5)P2. Therefore based on their concentrations the two most likely phosphoinositides regulating ion channels are PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P; both these lipids are substrates for PLC. In most cases however, PI(4,5)P2 which has a higher charge density is much more potent than PI(4)P. Some intracellular channels, such as TRPML1 may be specifically activated by PI(3,5)P2, which is found mainly in intracellular membranes, see later.

4.3 Relation to other channel regulators

Some TRP channels, such as TRPV5 and 6 are constitutively active, but most require another stimuli to open. In the case of PI(4,5)P2 dependent TRP channels opening happens when both PI(4,5)P2 and the stimulus, such as menthol for TRPM8 are present. These stimuli often modify the effect of PI(4,5)P2, see below.

4.4 The role of apparent affinity

The resting concentration of PI(4,5)P2 in the plasma membrane is relatively high. Thus channels with high apparent affinity for this lipid may be over-saturated, and physiological decreases in PI(4,5)P2 will not affect their activity significantly. Channels with lower affinity on the other hand are more likely to be regulated by physiological changes in PI(4,5)P2 levels. The apparent affinity for PI(4,5)P2 is not static for several TRP channels, their chemical ligands, such as capsaicin or menthol can increase PI(4,5)P2 affinity (Rohacs et al., 2005; Lukacs et al., 2007).

4.5 Potential indirect effects of phosphoinositides

The regulation of TRP channels by PI(4,5)P2 is complex, in many cases opposing effects of the lipid are reported even on the same channel. Phosphoinositides regulate many cellular processes, including the organization of the cytoskeleton, and membrane traffic (Saarikangas et al., 2010; Shewan et al., 2011). These effects are mediated by a large number and variety of PI(4,5)P2 binding proteins (DiNitto et al., 2003). It is quite likely that some, or most of the complexity originates from other phosphoinositide binding proteins influencing channel activity (Rohacs, 2009). See TRPC and TRPV1 channels for some specific details.

5. TRPM channels

TRPM channels are the most diverse group in terms of activation mechanisms, and biological function. When their phosphoinositide regulation is concerned, however, we probably have the clearest picture here. In short, it is quite likely that PI(4,5)P2 is a common co-factor for members of this group, necessary for activity. There are variations to this theme, but there is a clear agreement in the literature on the overall direction of the effect of phosphoinositides. Six out of the eight members have been reported to be positively regulated by PI(4,5)P2 by now (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mammalian TRPM channels

| Name | Regulation/function | Phosphoinositide effects |

|---|---|---|

| TRPM1 | Mutation causes night blindness in humans |

No phosphoinositide effect reported yet |

| TRPM2 | Activated by ADP ribose | Poly-lysine inhibits, and PI(4,5)P2 re-activates in excised patches (Toth and Csanady, 2012) |

| TRPM3 | Heat, pregnenolon sulphate | No phosphoinositide effect reported yet |

| TRPM4 | Intracellular Ca2+ activates, non-selective Ca2+ impermeable cation channel |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (Zhang et al., 2005; Nilius et al., 2006) |

| TRPM5 | Intracellular Ca2+ activates non-selective Ca2+ impermeable cation channel |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (Liu and Liman, 2003) |

| TRPM6 | Mg2+ transporter, mutation causes human disease |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, rapamycin-inducible 5 phosphatase and ciVSP inhibits (Xie et al., 2011) |

| TRPM7 | cAMP, shear stress, plays important roles in development |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, activation of PLC inhibits (Runnels et al., 2002). PI(4,5)P2 is needed for the activity of the cardiac magnesium- inhibited TRPM7-like channels (Gwanyanya et al., 2006). Role of PLC mediated inhibition is challenged (Takezawa et al., 2004; Langeslag et al., 2007) |

| TRPM8 | Cold, Menthol | PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (Liu and Qin, 2005; Rohacs et al., 2005; Yudin et al., 2011) PI(4,5)P2 depletion inhibits (rapamycin, ciVSP), plays a role in desensitization (Rohacs et al., 2005; Daniels et al., 2009; Yudin et al., 2011) PI(4,5)P2 but not PI(4)P activates in planar lipid bilayers (Zakharian et al., 2009; Zakharian et al., 2010) PI(4,5)P2 regulates temperature threshold (Fujita et al., 2013) |

5.1 TRPM8

The literature on phosphoinositide regulation is most extensive on the cold and menthol sensitive TRPM8. These channels are expressed in sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglia (DRG), and trigeminal ganglia (TG). Their genetic deletion in mice significantly impaired detection of moderately cold temperatures (Bautista et al., 2007; Dhaka et al., 2007).

TRPM8 was reported by two different laboratories to be re-activated by PI(4,5)P2 after run-down in excised patches, and inhibited by either poly-lysine (Fig. 2A) or anti PI(4,5)P2 antibody (Liu and Qin, 2005; Rohacs et al., 2005). Mutations of positively charged residues in the highly conserved proximal C-terminal TRP domain shifted PI(4,5)P2 dose-response to the left, and accordingly, made the channels more sensitive to inhibition by PLC, as expected from reduced apparent affinity for PI(4,5)P2 (Rohacs et al., 2005). Later it was also reported that TRPM8 is reactivated by MgATP in excised patches, and this was prevented by inhibiting PI4K (Yudin et al., 2011), see Fig. 2B. TRPM8 was the first TRP channel that was reported to be inhibited by selective reduction of PI(4,5)P2 by rapamycin-induced translocation of a 5-phosphatase (Varnai et al., 2006), see Fig. 3B, a finding confirmed by other laboratories (Daniels et al., 2009), see also supplemental material in (Wang et al., 2008). Later the voltage sensitive phosphatase ciVSP was also shown to inhibit the channel (Yudin et al., 2011), see Fig. 3C. Consistent with the robust inhibition by two different 5-phosphatases, PI(4)P had very little effect on TRPM8 in excised patches (Rohacs et al., 2005). The channel protein was also purified and reconstituted in planar lipid bilayers (Fig. 2C), where activation by both menthol and cold depended on the presence of PI(4,5)P2, and PI(4)P could not support channel activity (Zakharian et al., 2009; Zakharian et al., 2010). PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 were also much less effective both in excised patches (Rohacs et al., 2005) and in lipid bilayers (Zakharian et al., 2010). These data show that PI(4,5)P2 is a direct specific activator of TRPM8.

Both menthol- and cold-induced currents display a time dependent decrease, in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, a phenomenon termed adaptation, or desensitization. It has been shown that both menthol (Rohacs et al., 2005; Daniels et al., 2009) and cold (Yudin et al., 2011) decrease cellular PI(4,5)P2 levels via Ca2+-induced activation of PLCδ isoforms. Dialysis of PI(4,5)P2 but not PI(4)P through the whole-cell patch pipette inhibited desensitization of menthol-induced currents (Yudin et al., 2011). These data together with the clear dependence of channel activity on PI(4,5)P2 support a model in which Ca2+ influx through TRPM8 induces depletion of PI(4,5)P2, which limits channel activity, leading to desensitization. A more recent paper confirmed the role of PI(4,5)P2 depletion in tachyphylaxis, the decrease in amplitude after repeated agonist applications, but proposed a role for Calmodulin (CaM) in acute desensitization (Sarria et al., 2011). A recent paper also implied that PI(4,5)P2 is involved in setting the threshold temperature for TRPM8 (Fujita et al., 2013).

GPCR-s activating PLC have also been shown to inhibit TRPM8 (Liu and Qin, 2005), but the involvement of PI(4,5)P2 depletion here is much less clear. Both PKC (Premkumar et al., 2005) and direct inhibition by Gq-alpha (Zhang et al., 2012b) have been implicated.

In conclusion, it is universally accepted now that the activity of TRPM8 depends on PI(4,5)P2, see Figures 2 and 3 for supporting data using a variety of techniques. It is also clear, that activation of PLC either by GPCR-s or by Ca2+ influx through the channel inhibits TRPM8. How much PI(4,5)P2 depletion and other signaling pathways contribute to this inhibition is less clear; we refer to our recent review for further details (Yudin and Rohacs, 2011).

5.2 TRPM6 and TRPM7

TRPM6 and TRPM7 are closely related to each other; both channels have an atypical kinase domain at their C-terminus. Loss of function mutations in TRPM6 cause familial hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia in humans (Walder et al., 2002). TRPM7 has been proposed to have a variety of functions, but from knockout studies it appears that this channel has important roles in development (Jin et al., 2012). Interestingly, despite the relatively restricted disease its mutation causes in humans, genetic deletion of TRPM6 in mice is also embryonic lethal (Walder et al., 2009).

TRPM7 was reported to require PI(4,5)P2 for activity (Runnels et al., 2002; Gwanyanya et al., 2006) and PLC activation was shown to inhibit it (Runnels et al., 2002). Two articles however challenged the inhibitory effect of PLC activation (Takezawa et al., 2004; Langeslag et al., 2007). We have discussed this controversy in more detail in a recent review (Rohacs, 2009). TRPM6 was also recently reported to require PI(4,5)P2 for activity, and inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 depletion with inducible phosphatases (Xie et al., 2011).

5.3 TRPM4 and TRPM5

Both TRPM5 and TRPM4 are Ca2+ activated non-selective cation channels that are not permeable to Ca2+. TRPM5 is mainly expressed in taste and related tissues, whereas TRPM4 is more widely expressed. Both channels have been shown to undergo desensitization to Ca2+ in excised patches, which was restored by the application of PI(4,5)P2 (Liu and Liman, 2003; Zhang et al., 2005; Nilius et al., 2006). On TRPM4, the PI(4,5)P2 interaction site was proposed to be a distal C-terminal cluster of positively charged residues, termed PH-like domain (Nilius et al., 2006). Regions conforming to the K/R-X3-11-K/R-X-K/R consensus sequence of this region can be found in most TRP channels either in the C- or the N-terminal cytoplasmic domains (Nilius et al., 2008). Interestingly, the N-terminal PI(4,5)P2 interacting region recently proposed in TRPV4, also conforms to this consensus sequence (Garcia-Elias et al., 2013), see later. The role of this sequence motif in PI(4,5)P2 regulation of other TRP channels remains to be determined.

5.4 TRPM2

TRPM2 is another TRP channel that has an enzyme domain on its C-terminus, an ADP ribose hydrolase; accordingly, the channel can be activated in excised patches by ADP ribose. TRPM2 has been implicated in a variety of physiological functions, such as insulin secretion and immunological responses, but the overall phenotype of the knockout mouse is quite moderate (Yamamoto et al., 2008). To our knowledge there is only one publication of examining potential effects of PI(4,5)P2 on TRPM2 (Toth and Csanady, 2012). In this work the authors found that run-down of TRPM2 activity in excised patches is not caused by loss of PI(4,5)P2 from the patch membrane, but rather a collapse of the pore. When poly-Lysine was applied to excised inside out patches however, channel activity was inhibited, and this could be relieved by application of PI(4,5)P2. It is quite possible that TRPM2 also requires PI(4,5)P2 for activity, but its affinity to the lipid is quite high, thus loss of the lipid does not contribute to run-down at high agonist (ADP ribose) concentrations.

6. TRPV channels

TRPV channels can be divided into two groups, TRPV1-4 are all outwardly rectifying non-selective Ca2+ permeable cation channels that can be activated by heat with various thresholds. TRPV5 and 6 on the other hand are Ca2+-selective inwardly rectifying ion channels that play roles in epithelial Ca2+ transport. Phosphoinositides have been implicated in regulation of all members of this sub-group, in most cases PI(4,5)P2 has a positive regulatory role, but inhibition by PI(4,5)P2 has also been described with or without the presence of concurrent activating effect (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mammalian TRPV channels

| Name | Regulation/function | Phosphoinositide effects |

|---|---|---|

| TRPV1 | Heat, capsaicin, low pH, involved in nociception |

Positive effects of phosphoinositides:

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (Stein et al., 2006; Lukacs et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008c; Klein et al., 2008; Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2011) Channel activity runs down in excised patches, MgATP restores activity in a PI4K dependent manner (Lukacs et al., 2013) In addition to phosphoinositides, many other negatively charged lipids including phosphatidylglycerol and oleoyl-CoA also activate TRPV1 in excised patches (Lukacs et al., 2013) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits desensitization in intact cells (Liu and Qin, 2005; Lishko et al., 2007; Lukacs et al., 2007; Lukacs, 2013) Channel activity is inhibited by combined depletion of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P using a rapamycin-inducible dual-phosphatase pseudojanin (Hammond et al., 2012; Lukacs, 2013) TRPV1 is inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 depletion with a rapamycin- inducible 5 phosphatase (Klein et al., 2008; Yao and Qin, 2009). PI(4,5)P2 enhances thermosensation and thermal hyperalgesia. Depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by prostatic acid phosphatase-induced PLC activation inhibits thermal sensitivity (Sowa et al., 2010) PI(4,5)P2 sensitivity was proposed to be mediated via a PI(4,5)P2 binding protein Pirt (Kim et al., 2008a), was challenged (Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2011) Negative effects of phosphoinositides: PI(4,5)P2 may partially inhibit in intact cells (Chuang et al., 2001; Prescott and Julius, 2003; Lukacs et al., 2007; Patil et al., 2011) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits in lipid vesicles (Cao et al., 2013b) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits via competing for AKAP (Jeske et al., 2011) |

| TRPV2 | Growth factors activate, noxious heat activates, |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (Mercado et al., 2010) |

| TRPV3 | Heat activates in keratinocytes | PI(4,5)P2 inhibits in excised patches (Doerner et al., 2011) |

| TRPV4 | Heat, hyposmosis activates | PI(4,5)P2 is required for osmotic and heat activation (Garcia-Elias et al., 2013) |

| TRPV5 | Constitutively active epithelial Ca2+ channel |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (Lee et al., 2005; Rohacs et al., 2005) |

| TRPV6 | Constitutively active epithelial Ca2+ channel |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches and planar lipid bilayers (Thyagarajan et al., 2008; Zakharian et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2013a) Rapamycin-inducible 5 phosphatase inhibits, PI(4,5)P2 depletion plays a role in Ca2+-induced inactivation (Thyagarajan et al., 2008) |

6.1 TRPV1

TRPV1 is activated by heat, capsaicin, low extracellular pH and a plethora of other pain-producing agents in sensory neurons. TRPV1 is perhaps the most studied member of the TRP superfamily; its phosphoinositide regulation is no exception. Compared to the relatively simple picture with the TRPM family, the regulation of TRPV1 by phosphoinositides is quite complex and controversial.

There is full agreement in the literature that TRPV1 is activated by phosphoinositides in excised patches. First it was shown that poly-Lysine inhibits, and diC8 PI(4,5)P2 activates both native TRPV1 currents in DRG neurons, and recombinant TRPV1 expressed in F11 cells (Stein et al., 2006). A following article confirmed these results in recombinant TRPV1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes using both DiC8 and AASt PI(4,5)P2 (Lukacs et al., 2007). The apparent affinity for PI(4,5)P2 was increased by higher capsaicin concentrations, and accordingly, the velocity of current run-down was inversely correlated with the concentration of capsaicin in the patch pipette. The same article also found that all other phosphoinositides tested, PI(3,4,5)P2, PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, PI(5)P, and PI(4)P activated TRPV1. PI(4)P was less potent than PI(4,5)P2, i.e. its dose-response was shifted to the right, but the maximal effect was similar to that induced by PI(4,5)P2 (Lukacs et al., 2007). Similar results have been obtained in excised patches with PI(4)P in two additional publications (Klein et al., 2008; Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2011). Finally an article from a different laboratory studying mainly TRPA1 channels, confirmed the activating effect of PI(4,5)P2 on TRPV1 in excised patches (Kim et al., 2008c).

Results with inducible phosphatases also generally confirm the positive regulatory role of PI(4,5)P2, but there is a debate on weather or not PI(4)P contributes to channel activity in intact cells. Shortly after the first publication with the rapamycin inducible 5-phosphatase, it was shown that using this construct, depletion of PI(4,5)P2 via conversion to PI(4)P, did not inhibit TRPV1 activity at saturating capsaicin concentrations, whereas it inhibited TRPM8 (Lukacs et al., 2007). The lack of inhibition of TRPV1 was explained by the fact that PI(4)P also activates these channels, whereas TRPM8 is specifically activated by PI(4,5)P2. Two recent publications using the rapamycin-inducible dual specificity phosphatase pseudojanin supported this conclusion. First it was shown that capsaicin-induced TRPV1 currents were inhibited by rapamycin-induced activation of pseudojanin, which dephosphorylates both PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P, but not when either the 5 or the 4 phosphatase activity was eliminated by mutations (Hammond et al., 2012). Another article confirmed these results, and showed that TRPV1 currents induced by low pH were inhibited by rapamycin in pseudojanin expressing cells, but they were not inhibited by the specific 5-phosphatase drVSP (Lukacs, 2013). In contrast to these publications, two articles found that a rapamycin-inducible 5-phosphatase inhibited capsaicin-induced TRPV1 currents (Klein et al., 2008; Yao and Qin, 2009). The discrepancy between these and earlier results is not clear, but the rapamycin-inducible system in these studies used a different 5-phosphatase than the one used by (Lukacs et al., 2007). Despite discrepancies on the specific roles of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P, data using excised patches and inducible phosphatases are consistent with the idea that phosphoinositides are positive regulators or cofactors of TRPV1.

Data in the literature support the idea that the positive regulation by phosphoinositides plays a role in desensitization of TRPV1 currents, in a similar fashion that was described earlier for TRPM8 (Rohacs et al., 2005). It was shown that desensitization of recombinant (Lishko et al., 2007; Lukacs et al., 2007) and native TRPV1 (Lukacs, 2013) is inhibited by dialysis of either PI(4,5)P2 or PI(4)P through the whole cell patch pipette. It was also shown that activation of recombinant (Liu et al., 2005; Lukacs et al., 2007; Yao and Qin, 2009) and native TRPV1 channels in DRG neurons (Lukacs, 2013) leads to a depletion of PI(4,5)P2 and PI(4)P presumably via activation of PLCδ isoforms by the massive Ca2+ influx through the channels. Phosphoinositide depletion is probably not the only mechanism of desensitization, since neither PI(4,5)P2 not PI(4)P could fully inhibit desensitization. Consistent with this, several other mechanisms, such as CaM, calcineurin, and direct binding of ATP to the channel have been proposed to play roles in desensitization (Mohapatra and Nau, 2005; Lishko et al., 2007; Rohacs, 2013).

As mentioned earlier however, TRPV1 was first proposed to be inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 (Chuang et al., 2001) via direct binding to a distal C-terminal lipid interacting site (Prescott and Julius, 2003). It was also proposed that pro-inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin sensitize TRPV1 to moderate stimuli, via removing this inhibitory effect by PLC mediated PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis. This model was mainly based on indirect evidence, and the effects of phosphoinositides were not tested in excised patches. To lend further support to the idea that PI(4,5)P2 inhibits TRPV1, the same laboratory recently purified the TRPV1 protein, and incorporated it into artificial liposomes. By patch clamping those liposomes, they showed that the channel was fully active in the absence of phosphoinositides, and that incorporation of PI(4,5)P2, PI(4)P or even PI, inhibited TRPV1 activity, more precisely, shifted the capsaicin dose-response curve to the right. Removal of the distal C-terminal phosphoinositide binding domain eliminated inhibition by PI(4,5)P2 (Cao et al., 2013b).

How do we reconcile these two seemingly incompatible views? First of all, the fact that TRPV1 showed both heat and capsaicin activation in an artificial membrane devoid of phosphoinositides makes it very clear that these lipids are not necessary for channel activity per se. As mentioned earlier, activation of TRPV1 by phosphoinositides was not specific to PI(4,5)P2, any other phosphoinositide could exert similar effects in excised patches (Lukacs et al., 2007). Among Kir channels, Kir6.2 (KATP) has a similar non-specific activation profile for phosphoinositides (Rohacs et al., 2003). Those channels can be activated not only by phosphoinositides, but many other negatively charged lipids, such as oleoyl-CoA (Rohacs et al., 2003), phosphatidylserine at high concentrations (Fan and Makielski, 1997) and even the artificial lipid DGS-NTA (Krauter et al., 2001). The liposomes used by (Cao et al., 2013b) contained high concentrations (~25%) of phosphatidyl glycerol (PG), which has a negative charge. One possible explanation for the full activity of TRPV1 in the complete absence of phosphoinositides is that the high concentrations of PG satisfied the requirement for negatively charged lipids for the activity of the channel. Indeed, when PG was tested in excised inside-out patches, it reactivated TRPV1 currents after run-down when applied at very high concentrations (Lukacs et al., 2013). Other phospholipids with single negative charges, phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylinositol (PI) could also support TRPV1 activity at high concentrations. Similar to KATP channels, oleoyl-CoA and DGS-NTA also activated TRPV1 (Lukacs et al., 2013). When the purified channel was incorporated in planar lipid bilayers consisting of neutral lipids, capsaicin activation depended on the presence of PI(4,5)P2 (Lukacs et al., 2013). TRPV1 activity showed ~90% run-down in excised patches after 5 minutes in an ATP free solution, and MgATP reactivated the channel in a PI4K dependent manner. This shows that phospholipids with single negative charges (PS, PI and PG) that do not become dephosphorylated in excised patches contribute to TRPV1 activity 10% or less. In conclusion, despite its promiscuous lipid specificity profile, in the context of the plasma membrane, the major intracellular lipids supporting TRPV1 activity are PI(4,5)P2 and potentially PI(4)P (Lukacs et al., 2013).

As to the inhibitory effect of PI(4,5)P2, there are many other data supporting this idea, most are based on measurements in intact cells or whole-cell patch clamp. We have found earlier that at low stimulation levels with capsaicin or heat, the rapamycin inducible 5-phoshatase potentiated TRPV1 currents both in HEK cell and in Xenopus oocytes (Lukacs et al., 2007). More recently we found that depleting PI(4,5)P2 with ciVSP potentiated TRPV1 currents induced by low capsaicin in Xenopus oocytes (unpublished observation), but neither ciVSP nor drVSP potentiated TRPV1 currents in a mammalian expression system either with low capsaicin, or low pH (Lukacs, 2013). On the other hand, selective depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by drVSP potentiated the sensitizing effect of sub-threshold and submaximal concentrations of the PKC agonist OAG (Lukacs, 2013). Dialysis of PI(4,5)P2, but not PI(4)P via the whole cell patch pipette inhibited bradykinin-induced sensitization, which again is compatible with PI(4,5)P2 being inhibitory. Based on this and other experiments, we have proposed a model in which GPCR activation leads to a selective moderate decrease in PI(4,5)P2 levels, which potentiates the well known sensitizing effect of PKC (Lukacs, 2013).

The fact that inhibition by PI(4,5)P2 was not detected in excised patches by any laboratory, argued that any inhibition of TRPV1 by PI(4,5)P2 is likely to be indirect, i.e. mediated by other cellular components or PI(4,5)P2 binding proteins. The A-Kinase anchoring protein AKAP150 for example was proposed to mediate the inhibitory effect of PI(4,5)P2 (Jeske et al., 2011). Another PI(4,5)P2 binding protein that was proposed to influence TRPV1 activity is Pirt (Kim et al., 2008a). This protein, however was proposed to mediate positive effects of PI(4,5)P2, and its role has been recently challenged (Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2011). The finding that PI(4,5)P2 inhibited the purified TRPV1 in artificial membranes provided strong support for a direct inhibition by phosphoinositides (Cao et al., 2013b). Clearly, more work is needed at this point to understand the mechanism of negative modulation of TRPV1 by phosphoinositides.

Overall, the author’s view is that TRPV1 requires negatively charged lipids for activity, and in the cellular context these lipids are PI(4,5)P2 and probably PI(4)P. Removal of these phosphoinositides contribute to desensitization upon maximal pharmacological activation. A concurrent inhibitory effect is also quite likely, and smaller selective decreases in PI(4,5)P2 levels contribute to sensitization by pro-inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin (Lukacs, 2013; Rohacs, 2013).

6.2 TRPV2

TRPV2 was originally proposed to be a noxious heat sensor, with activation temperatures over 50 °C, but subsequent studies showed that TRPV2−/− mice have no temperature sensation deficit (Park et al., 2011). At the same time, the knockout animals had impaired phagocytosis by macrophages (Link et al., 2010). As opposed to the large number of papers on TRPV1, there is only one publication on TRPV2 in connection to PI(4,5)P2 (Mercado et al., 2010). This article showed that TRPV2 is inhibited by poly-Lys, and reactivated by DiC8 PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches. It was also shown that activation of the channel with its chemical agonist 2-APB induced a depletion of PI(4,5)P2 resulting in desensitization of the channel.

6.3 TRPV3

TRPV3 is activated by moderate heat in keratinocytes. Gain of function mutations in TRPV3 cause Olmsted syndrome, a rare congenital disorder characterized by palmoplantar and periorificial keratoderma, alopecia, and severe itching (Lin et al., 2012). This channel was reported to be inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches and its voltage and temperature dependent gating was potentiated by hydrolysis of the lipid (Doerner et al., 2011).

6.4 TRPV4

TRPV4 is another temperature sensitive TRP channel, which also acts as an osmosensor. Mutations in this channel are also associated with a variety of human diseases (Nilius and Voets, 2013). A recent report (Garcia-Elias et al., 2013) showed that activation of this channel in excised patches by heat required PI(4,5)P2. In intact cells, both osmotic and heat-induced activation was eliminated if PI(4,5)P2 was depleted using a rapamycin-inducible PI(4,5)P2 phosphatase (Garcia-Elias et al., 2013). Activation by a direct chemical agonist 4α-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate was not affected by PI(4,5)P2 depletion. Positively charged residues in the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain (121KRWRK125), located before the ankyrin-repeats and the proline-rich domain, were implied in the effect of PI(4,5)P2. PI(4,5)P2 depletion increased the distance between the C-terminal ends of the channel as determined by fluorescence resonance energy transfer, indicating a structural rearrangement of the channel upon PI(4,5)P2 binding (Garcia-Elias et al., 2013).

6.5 TRPV5 and TRPV6

These two channels are highly homologous to each other, but less to other members of the TRPV family. Unlike any other TRP channels, TRPV5 and 6 are Ca2+ selective, and they display inward rectification. Both are implicated in epithelial Ca2+ transport, TRPV5 in the kidney (Hoenderop et al., 2003), whereas TRPV6 in the duodenum (Bianco et al., 2007) and in epididymal epithelia (Weissgerber et al., 2011).

The activity of both TRPV5 (Lee et al., 2005) and TRPV6 (Thyagarajan et al., 2008) runs down in excised patches, and they are reactivated by PI(4,5)P2, but not PI(4)P. TRPV6 has also been shown to be re-activated by MgATP in excised patches and this effect was inhibited by three structurally different compounds that inhibit PI4K activity, showing that MgATP in this system acted by providing substrate for lipid kinases (Zakharian et al., 2011). TRPV6 was also shown to be activated by PI(4,5)P2 but not PI(4)P in planar lipid bilayers, demonstrating direct effect on the channel (Zakharian et al., 2011). Consistent with the lack of effect of PI(4)P, the channel is inhibited by the rapamycin-inducible 5-phosphatase (Thyagarajan et al., 2008). Ca2+ influx through TRPV6 was also shown to activate PLC, contributing to channel inactivation (Thyagarajan et al., 2009). CaM has also been implicated in Ca2+-induced inactivation of both TRPV6 (Niemeyer et al., 2001; Derler et al., 2006) and TRPV5 (de Groot et al., 2011). CaM was shown to inhibit TRPV6 in excised patches, which could be alleviated, but not prevented by excess PI(4,5)P2 (Cao et al., 2013a). CaM and PI(4,5)P2 thus compete with each other, even though it probably does happen through direct competition, as proposed for TRPC6 (Kwon et al., 2007) since we could not observe competition in biochemical binding experiments. Overall, it is quite likely that PI(4,5)P2 depletion and CaM cooperatively produce Ca2+-induced inactivation of TRPV6 (Cao et al., 2013a).

7. TRPC channels

Mammals have 6 or 7 TRPC channels, depending on the species; in humans TRPC2 is a pseudogene. From the functional point of view, this group is the most homogenous, all members are activated downstream of PLC. There are certainly flavors to this general theme, but at least on the textbook level we can make this generalization. TRP channels were discovered in drosophila, where they play a role in visual transduction. The channel complex that generates the receptor potential in the insect eye consists of the TRP and the TRPL channels, both are homologues of the mammalian TRPC channel, thus they will be discussed here.

When it comes to their phosphoinositide regulation, this group is probably the most complicated among the three major families (Table 3). Inhibition by PI(4,5)P2 and relief from inhibition by depletion of this lipid upon PLC activation was proposed originally as a mechanism contributing to activation (Estacion et al., 2001). This notion however is controversial, it may contribute to activation in some cases, but it is certainly not a general mechanism of opening. What activates TRPC-s is not elucidated yet; activation of TRPC3, 6 and 7 channels by DAG is very well accepted, but there is less agreement on how other TRPC-s are activated. It is quite likely that multiple and diverse mechanisms converge on most TRPC channels (Putney and Tomita, 2011; Rohacs, 2013).

Table 3.

Mammalian TRPC channels and drosophila orthologues,

| Name | Regulation/function | Phosphoinositide effects |

|---|---|---|

| dTRPL | Activated downstream of PLC, drosophila vision |

PI(4,5)P2 inhibits in excised patches (Estacion et al., 2001) PI(4,5)P2 activates but PI(4)P and PI inhibits in excised patches (Huang et al., 2010) |

| TRPC1 | Activated downstream of PLC | PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, native cells (Saleh et al., 2009b, a; Shi et al., 2012) |

| TRPC3 | Activated downstream of PLC, DAG activates |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, expression system (Lemonnier et al., 2008) VSP inhibits (Imai et al., 2012; Itsuki et al., 2012) |

| TRPC4 | Activated downstream of PLC | TRPC4α but not TRPC4β is inhibited by PI(4,5)P2, whole cell patch clamp (Otsuguro et al., 2008) TRPC4β is inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 depletion (rapamycin- inducible phosphatase) (Kim et al., 2013) |

| TRPC5 | Activated downstream of PLC, | PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, but inhibits in whole cell, PI(4,5)P2 depletion may inhibit or activate it (Trebak et al., 2009) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits desensitization in whole-cell patch clamp (Kim et al., 2008b) PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patch in complex with TRPC1 in native cells, but inhibits in the absence of TRPC1 (Shi et al., 2012) |

| TRPC6 | Activated downstream of PLC, DAG activates |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches (expression system) (Lemonnier et al., 2008) VSP inhibits (Imai et al., 2012; Itsuki et al., 2012) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits in excised patches (native smooth muscle cells) (Albert et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2010) Extracellular PI(4,5)P2 enhances its activity in platelets (Jardin et al., 2008) Calmodulin inhibits by displacing PI(3,4,5)P3 (Kwon et al., 2007) |

| TRPC7 | Activated downstream of PLC, DAG activates |

PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, expression system (Lemonnier et al., 2008) VSP inhibits (Imai et al., 2012; Itsuki et al., 2012) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits in excised patches, native channels (Ju et al., 2010) |

7.1 Excised patch data

The first publication implying PI(4,5)P2 in this channel family showed that the drosophila TRPL channel expressed in SF9 cells was inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches (Estacion et al., 2001). The authors proposed that PI(4,5)P2 depletion together with DAG activates dTRPL. This finding fits very well the hypothesis that PI(4,5)P2 is a general inhibitor of TRP channels, and would also provide a logical activation mechanism for TRPC channels that are also activated downstream of PLC. Several years later, however, this finding was challenged, and it was shown that DiC8 PI(4,5)P2 activated TRPL, whereas PI(4)P and PI inhibited it (Huang et al., 2010).

Recombinant TRPC channels are often used as models to study channel regulation, since endogenous TRPC currents are often too small to measure reliably. Recombinant TRPC5 (Trebak et al., 2009) as well as TRPC3, 6 and 7 channels (Lemonnier et al., 2008) have been shown to be activated by PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches.

There is quite some work performed in native vascular smooth muscle cells on phosphoinositide regulation of TRPC channels, reviewed in (Large et al., 2009). TRPC1 channels were shown to be activated in excised patches either alone (Saleh et al., 2009b) or in complex with TRPC5 channels (Shi et al., 2012). These results are consistent with the general activation of recombinant TRPC channels. On the other hand, native TRPC5 (Shi et al., 2012), TRPC6 (Albert et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2010) and TRPC7 channels were shown to be inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 in excised inside-out patches (Ju et al., 2010). These results contradict the activating effect of PI(4,5)P2 on the same channels studied in expression systems.

7.2 Whole cell patch clamp experiments

Recombinant TRPC5 is activated by PI4K inhibition, and inhibited by inclusion of PI(4,5)P2 or PI(4)P in the patch pipette (Trebak et al., 2009). This is consistent with PI(4,5)P2 depletion contributing to activation. As mentioned earlier however, the same paper showed that TRPC5 is activated in excised patches, furthermore, PI(4,5)P2 depletion with a rapamycin-inducible 5-phosphatase inhibited the channel (Trebak et al., 2009). A general feature of TRPC channel activation by GPCR-s is that after an initial peak, current amplitudes decline (desensitization). It was shown that inclusion of PI(4,5)P2 in the patch pipette inhibited desensitization of TRPC5 (Kim et al., 2008b). This is compatible with the idea that hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 initiates TRPC5 channel activation, but the loss of the lipid limits channel activity on a longer time course.

TRPC4α but not TRPC4β was shown to be inhibited by intracellular dialysis of PI(4,5)P2. This effect depended on the actin cytoskeleton, and was prevented by the deletion of the C-terminal PDZ-binding motif that links TRPC4 α to F-actin through the sodium-hydrogen exchanger regulatory factor and ezrin (Otsuguro et al., 2008). Intriguingly, TRPC4β was inhibited by a rapamycin-inducible 5 phosphatase, and desensitization was inhibited by both PI(4,5)P2 and its non-hydrolyzable analogue (Kim et al., 2013).

Depletion of PI(4,5)P2 using the voltage sensitive phosphatase drVSP inhibited recombinant TRPC3, 6 and 7 channels (Imai et al., 2012; Itsuki et al., 2012). The same study showed that channels desensitized less if endogenous muscarinic receptors were stimulated than if similar receptors were over-expressed. They also showed that stimulation of over-expressed receptors lead to a much stronger decrease in PI(4,5)P2 levels than that induced by endogenous receptors. This is consistent with the idea that loss of PI(4,5)P2 is a major factor in desensitization during PLC activation. Accordingly, intracellular dialysis of PI(4,5)P2 slowed the desensitization of recombinant TRPC3, 6 and 7 channels, and endogenous TRPC-s in A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells (Imai et al., 2012).

7.3 Conclusions

Many TRPC channels have been shown to be activated by PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches, and inhibited by specific inducible phosphatases in intact cells. Depletion of PI(4,5)P2 may contribute to desensitization of several of them during PLC stimulation. In principle, loss of PI(4,5)P2 may limit channel activity in two different ways. Since PI(4,5)P2 activates many TRPC-s in excised patches, it is possible that it functions as a co-factor needed for channel activity. It is also possible however, that loss of PI(4,5)P2 is limiting channel activity, because there is less substrate for PLC, thus less activating messenger, for example DAG, is generated. PI(4)P however is also a substrate for PLC, even though generally most isoforms are more active in hydrolyzing PI(4,5)P2 (Fukami et al., 2010). It also has to be noted that much of the data supporting this desensitization model is performed in expression systems, and some native channels may behave differently.

An opposing model, in which PI(4,5)P2 is inhibitory, and its depletion contributes to activation, may be valid for some TRPC-s, but it is unlikely to be a general mechanism. Overall, there are several discrepancies in the literature, especially between excised patch data on native TRPC-s and recombinant ones (see table 3). It is possible that endogenous channels assemble with accessory proteins that modify their function. Given that drosophila visual TRP-s function in a highly organized local complex (Montell, 2012), it would not be surprising if endogenous mammalian TRPC functioned similarly. TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels for example are shown to be associated with the phospholipid binding protein SESTD1 (Miehe et al., 2010). It has to be noted that when studying endogenous TRPC channels, it may be difficult to unambiguously identify individual TRPC channel subtypes in native tissues. Clearly, more work is needed to understand how phosphoinositides regulate TRPC channels.

8. Other TRP channels

8.1 TRPA1

TRPA1 was originally proposed to be a noxious cold sensor. Its activation by cold is controversial; there are numerous articles claiming that cold temperatures activate the channel, and similar number claiming that cold has no effect. There is full agreement in the literature that noxious chemicals, such as mustard oil, formaldehyde and compounds in tear gases, activate this channel. TRPA1 is especially important in the respiratory system for avoiding inhalation of harmful chemicals (Nilius et al., 2012). The involvement of TRPA1 in pain in humans is demonstrated by the finding that gain of function mutations of these channels cause Familial Episodic Pain Syndrome (Kremeyer et al., 2010).

The regulation of TRPA1 by phosphoinositides is also complicated (Table 4). The activity of recombinant TRPA1 channels was found to run down in excised patches, and could be re-activated by PI(4,5)P2 and by MgATP. Run down however became irreversible after >2 min in ATP free conditions (Karashima et al., 2008). This behavior of TRPA1 in excised patches was quite similar in our hands (T.R. unpublished observation). The same study by Karashima et al reported that mustard oil-induced currents in DRG neurons were inhibited by high concentrations of wortmannin, where the drug inhibits PI4K. Rapid desensitization in response to mustard oil was inhibited by supplying PI(4,5)P2 through the patch pipette, whereas neomycin, which chelates phosphoinositides accelerated it (Karashima et al., 2008). These data support a model in which TRPA1 activity depends on PI(4,5)P2 and its depletion plays a role in desensitization. Consistent with the proposed dependence of TRPA1 activity on PI(4,5)P2, another study found that capsaicin-induced cross desensitization of TRPA1 was prevented by dialysis of PI(4,5)P2 through the patch pipette (Akopian et al., 2007). Contrary to these findings however, two articles reported no effect of PI(4,5)P2 in excised patches (Kim and Cavanaugh, 2007) or inhibition in the presence of inorganic poly-phosphate (Kim et al., 2008c), which is an intracellular activator of these channels. Another study found that depletion of PI(4,5)P2 with a rapamycin inducible 5-phosphatase did not inhibit TRPA1, while it inhibited TRPM8 (Wang et al., 2008). In conclusion there are indications, that TRPA1 requires PI(4,5)P2 for activity, but there are also contrary data in the literature, and the regulation of these channels by phosphoinositides may be more complex than a simple dependence on PI(4,5)P2.

Table 4.

Other TRP channels

| Name | Regulation/function | Phosphoinositide effects |

|---|---|---|

| TRPA1 | Mustard oil and other noxious chemicals |

PI(4,5)P2 inhibits heterologous desensitization by capsaicin (Akopian et al., 2007) PI(4,5)P2 activates in excised patches, inhibits desensitization in whole cell (Karashima et al., 2008) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits sensitization by PAR in whole-cell (Dai et al., 2007) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits in excised patches in the presence of PPPi, no effect w/o PPPi (Kim and Cavanaugh, 2007; Kim et al., 2008c) Depletion of PI(4,5)P2 with rapamycin-inducible phosphatase have no effect (Wang et al., 2008) |

| TRPML1 | Intracellular channel, mutation causes mucolipidosis |

Specifically activated by PI(3,5)P2 (Dong et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012a) |

| TRPP2 | Mutated in polycystic kidney disease, Mechanosensor? |

PI(4,5)P2 inhibits, depletion of PI(4,5)P2 by EGF activates (Ma et al., 2005) |

8.2 TRPML1

Members of the TRPML sub-family are Ca2+ and Fe2+ permeable non-selective cation channels located in intracellular membranes. Functional TRPML1 channels are located in the endolysosomal membranes. Mutations in this channel cause type IV mucolipidosis in humans. TRPML requires the presence of PI(3,5)P2, which is also specifically located in endolysosomal membranes. Activation by PI(3,5)P2 is highly specific, and the channels have a very high apparent affinity for this lipid, the EC50 of TRPML for PI(3,5)P2 is 48 nM (Dong et al., 2010). For comparison, the highest affinity mammalian plasma membrane channels have an EC50 of 5 μM for Kir2.1 (Rohacs et al., 2002), and 1.3 – 4.9 μM for TRPV1 depending on the conditions (Lukacs et al., 2007; Klein et al., 2008). On the low affinity end, KCNQ2/3 channels have an EC50 of 40-80 μM (Zhang et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005). Intriguingly, a similar high specificity activation by PI(3,5)P2 was also described for another intracellular ion channel family, the two-pore TPC1 and TPC2 channels, very distant homologues of TRP channels (Wang et al., 2012).

One very important function of phosphoinositides is to serve as markers of identity of various membrane compartments, such as the plasma membrane (PM), endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi or endosomes (Shewan et al., 2011). It was proposed by Hilgemann, that a major function of the general dependence of ion channels on PI(4,5)P2 is to avoid their opening during their passage through the ER and Golgi, which are devoid of PI(4,5)P2, and selectively open on the arrival in the PM, which contains this lipid (Hilgemann et al., 2001). An “inverted” version of this theme was proposed for TRPML1 channels; it was shown that TRMPL1 is inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 thus the channels that “accidentally” reached the plasma membrane, are inactivated by PI(4,5)P2. PM channels could be activated by either depleting PI(4,5)P2 or adding excess PI(3,5)P2 (Zhang et al., 2012a).

8.3 TRPP1

TRPP1 (PKD2, Polycystin 2, also called TRPP2 in older nomenclature) is a member of the TRPP family (Wu et al., 2010). It co-assembles with PKD1, and loss of function mutations of either proteins lead to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Despite its well-established role in the pathophysiology of this quite common genetic disorder, its physiological roles and regulation is not very well understood. TRPP2 is activated by epidermal growth factor, and this was proposed to proceed via relief from PI(4,5)P2 inhibition upon PLC activation (Ma et al., 2005).

9. Conclusions and future questions

PI(4,5)P2 modulates many different ion channels. For Kir and KCNQ channels it has been demonstrated beyond doubt that PI(4,5)P2 is an obligatory cofactor for the activity of all members of the respective ion channels families. This is based on results from many different techniques, including excised patches and specific inducible lipid phosphatases in intact cells, and the results with these channels are largely in agreement between different laboratories. For Kir channels high-resolution co-crystal structures of channels with and without PI(4,5)P2 have recently became available.

By now, there is data in the literature for almost all members of the 3 major TRP channel families showing some form of modulation by PI(4,5)P2. On these channels however, we are very far from the clear picture with Kir-s and KCNQ-s. In most cases TRP channel activity depends on PI(4,5)P2, just like for Kir-s and KCNQ-s. It is safe to say, that activation by PI(4,5)P2 via direct binding of the lipid to the channel is a conserved feature among many members of the 3 major subfamilies. The dependence of channel activity on PI(4,5)P2 seem to play a role in desensitization via PLC induced depletion of the lipid for a large number of TRP channels including some members of all three major sub-families.

For several TRP channels inhibitory effects of PI(4,5)P2 were published, often in contradiction with the presence of an activating effect on the same channel. Often the different techniques we described gave seemingly non-coherent results. Since this is a recurring theme, it is hard to dismiss them as unreliable data. Apparently the phosphoinositide regulation of many TRP channels, TRPV1 and TRPCs for example, is quite complex, and it is likely that some of the effects of phosphoinositide effects are mediated by other PI(4,5)P2 binding proteins. Clearly more work is needed to solve the puzzle of how TRP channels are regulated by phosphoinositides.

Much is needed also on the structure-function front. Since direct activation by PI(4,5)P2 was shown for several TRP channels, it is quite likely that the activating effect of the lipid results from direct binding. From the sporadic mutations affecting PI(4,5)P2 regulation no coherent picture is arising about the binding site. With representative members of most major mammalian ion channel families having been crystallized, we may be cautiously optimistic about the prospect of obtaining full-length structures of TRP channels, which would be a tremendous boost to structure function studies on these channels.

Abbreviations

- AASt

Arachydonyl-stearyl

- AKAP

A-kinase anchoring protein

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- DGS-NTA

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[(N-(5-amino-1-carboxypentyl)iminodiacetic acid)succinyl]

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GPCR

G Protein Coupled Receptor

- IP3

Inositol-1,4,5-trisphopshate

- Kir

K+ inwardly rectifying

- PI

Phosphatidylinositol

- PI(4)P

Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate

- PI(4,5)P2

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PI4K

Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase

- PIP5K

Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PLC

Phospholipase C

- PG

phosphatidyl glycerol

- PKC

Protein Kinase C

- PH

Pleckstrin-homology

- Pirt

phosphoinositide interacting regulator of TRP

- PM

Plasma membrane

- TG

trigeminal ganglion

- TPC

Two-pore channel

- TRP

Transient Receptor Potential

- TRPA

TRP Ankyrin

- TRPC

TRP Classical

- TRPL

TRP-like

- TRPM

TRP Melastatin

- TRPML

TRP Mucolipin

- TRPP

TRP Polycystin

- TRPV

TRP Vanilloid

- VSP

Voltage sensitive phosphatase

REFERENCES

- Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Jeske NA, Hargreaves KM. Transient receptor potential TRPA1 channel desensitization in sensory neurons is agonist dependent and regulated by TRPV1-directed internalization. J Physiol. 2007;583:175–193. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Saleh SN, Large WA. Inhibition of native TRPC6 channel activity by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2008;586:3087–3095. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen V, Swigart P, Cheung R, Cockcroft S, Katan M. Regulation of inositol lipid-specific phospholipase C-delta by changes in Ca2+ ion concentrations. Biochem J. 1997;327:545–552. doi: 10.1042/bj3270545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altan-Bonnet N, Balla T. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases: hostages harnessed to build panviral replication platforms. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T, Schulte U, Oliver D, Herlitze S, Krauter T, Tucker SJ, Ruppersberg JP, Fakler B. PIP2 and PIP as determinants for ATP inhibition of KATP channels. Science. 1998;282:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Siemens J, Glazer JM, Tsuruda PR, Basbaum AI, Stucky CL, Jordt SE, Julius D. The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature. 2007;448:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nature05910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco SD, Peng JB, Takanaga H, Suzuki Y, Crescenzi A, Kos CH, Zhuang L, Freeman MR, Gouveia CH, Wu J, Luo H, Mauro T, Brown EM, Hediger MA. Marked disturbance of calcium homeostasis in mice with targeted disruption of the Trpv6 calcium channel gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:274–285. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauchi S, Orta G, Mascayano C, Salazar M, Raddatz N, Urbina H, Rosenmann E, Gonzalez-Nilo F, Latorre R. Dissection of the components for PIP2 activation and thermosensation in TRP channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10246–10251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703420104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Zakharian E, Borbiro I, Rohacs T. Interplay between calmodulin and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in Ca2+-induced inactivation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 6 channels. J Biol Chem. 2013a;288:5278–5290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao E, Cordero-Morales JF, Liu B, Qin F, Julius D. TRPV1 channels are intrinsically heat sensitive and negatively regulated by phosphoinositide lipids. Neuron. 2013b;77:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WW, D'Avanzo N, Doyle DA, Nichols CG. Dual-mode phospholipid regulation of human inward rectifying potassium channels. Biophys J. 2011;100:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang HH, Prescott ED, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt SE, Basbaum AI, Chao MV, Julius D. Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature. 2001;411:957–962. doi: 10.1038/35082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Avanzo N, Cheng WW, Doyle DA, Nichols CG. Direct and specific activation of human inward rectifier K+ channels by membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:37129–37132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.186692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Wang S, Tominaga M, Yamamoto S, Fukuoka T, Higashi T, Kobayashi K, Obata K, Yamanaka H, Noguchi K. Sensitization of TRPA1 by PAR2 contributes to the sensation of inflammatory pain. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1979–1987. doi: 10.1172/JCI30951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels RL, Takashima Y, McKemy DD. Activity of the neuronal cold sensor TRPM8 is regulated by phospholipase C via the phospholipid phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1570–1582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807270200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot T, Kovalevskaya NV, Verkaart S, Schilderink N, Felici M, van der Hagen EA, Bindels RJ, Vuister GW, Hoenderop JG. Molecular mechanisms of calmodulin action on TRPV5 and modulation by parathyroid hormone. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2845–2853. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01319-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derler I, Hofbauer M, Kahr H, Fritsch R, Muik M, Kepplinger K, Hack ME, Moritz S, Schindl R, Groschner K, Romanin C. Dynamic but not constitutive association of calmodulin with rat TRPV6 channels enables fine tuning of Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Physiol. 2006;577:31–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A, Murray AN, Mathur J, Earley TJ, Petrus MJ, Patapoutian A. TRPM8 is required for cold sensation in mice. Neuron. 2007;54:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNitto JP, Cronin TC, Lambright DG. Membrane recognition and targeting by lipid-binding domains. Sci STKE. 20032003:re16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2132003re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner JF, Hatt H, Ramsey IS. Voltage- and temperature-dependent activation of TRPV3 channels is potentiated by receptor-mediated PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137:271–288. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, Zhang Q, Cheng X, Zhang Y, Weisman LS, Delling M, Xu H. PI(3,5)P2 controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca2+ release channels in the endolysosome. Nat Commun. 2010;1:38. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M, Sinkins WG, Schilling WP. Regulation of Drosophila transient receptor potential-like (TrpL) channels by phospholipase C-dependent mechanisms. J Physiol. 2001;530:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0001m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Makielski JC. Anionic phospholipids activate ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5388–5395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman DA, Meyers RE, Cantley LC. Phosphoinositide kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:481–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita F, Uchida K, Takaishi M, Sokabe T, Tominaga M. Ambient temperature affects the temperature threshold for TRPM8 activation through interaction of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6154–6159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5672-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami K, Inanobe S, Kanemaru K, Nakamura Y. Phospholipase C is a key enzyme regulating intracellular calcium and modulating the phosphoinositide balance. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Yamane T, Terai T, Katayama Y, Hiraoka M. Functional linkage of the cardiac ATP-sensitive K+ channel to the actin cytoskeleton. Pflugers Arch. 1996;431:504–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02191896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N, Rohacs T. Phosphoinositide sensitivity of ion channels, a functional perspective. Subcell Biochem. 2012;59:289–333. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-3015-1_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Elias A, Mrkonjic S, Pardo-Pastor C, Inada H, Hellmich UA, Rubio-Moscardo F, Plata C, Gaudet R, Vicente R, Valverde MA. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate-dependent rearrangement of TRPV4 cytosolic tails enables channel activation by physiological stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9553–9558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220231110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwanyanya A, Sipido KR, Vereecke J, Mubagwa K. ATP and PIP2 dependence of the magnesium-inhibited, TRPM7-like cation channel in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C627–635. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00074.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond GR, Fischer MJ, Anderson KE, Holdich J, Koteci A, Balla T, Irvine RF. PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 Are Essential But Independent Lipid Determinants of Membrane Identity. Science. 2012;337:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1222483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SB, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC. TRP channels and lipids: from Drosophila to mammalian physiology. J Physiol. 2007;578:9–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW. Fitting K(V) potassium channels into the PIP2 puzzle: Hille group connects dots between illustrious HH groups. J Gen Physiol. 2012;140:245–248. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Ball R. Regulation of cardiac Na+,Ca2+ exchange and KATP potassium channels by PIP2. Science. 1996;273:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Feng S, Nasuhoglu C. The complex and intriguing lives of PIP2 with ion channels and transporters. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.111.re19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenderop JG, van Leeuwen JP, van der Eerden BC, Kersten FF, van der Kemp AW, Merillat AM, Waarsing JH, Rossier BC, Vallon V, Hummler E, Bindels RJ. Renal Ca2+ wasting, hyperabsorption, and reduced bone thickness in mice lacking TRPV5. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1906–1914. doi: 10.1172/JCI19826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL. Complex roles of PIP2 in the regulation of ion channels and transporters. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1761–1765. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00400.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]