Abstract

The challenge of stabilization of small molecules and proteins has received considerable interest. The biological activity of small molecules can be lost as a consequence of chemical modifications, while protein activity may be lost due to chemical or structural degradation, such as a change in macromolecular conformation or aggregation. In these cases stabilization is required to preserve therapeutic and bioactivity efficacy and safety. In addition to use in therapeutic applications, strategies to stabilize small molecules and proteins also have applications in industrial processes, diagnostics, and consumer products like food and cosmetics. Traditionally, therapeutic drug formulation efforts have focused on maintaining stability during product preparation and storage. However, with growing interest in the fields of encapsulation, tissue engineering and controlled release drug delivery systems, new stabilization challenges are being addressed; the compounds or protein of interest must be stabilized during: (1) fabrication of the protein or small molecule loaded carrier, (2) device storage, and (3) for the duration of intended release needs in vitro or in vivo. We review common mechanisms of compound degradation for small molecules and proteins during biomaterial preparation (including tissue engineering scaffolds and drug delivery systems), storage and in vivo implantation. We also review the physical and chemical aspects of polymer-based stabilization approaches, with a particular focus on the stabilizing properties of silk fibroin biomaterials.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, stabilization approaches include modification of the small molecule or protein to reduce susceptibility to degradation (including chemical and genetic engineering, cross-linking, protein crystallization, and chemical modification), optimization of the storage environment (lyophilization, storage in organic solvents, freezing, storage in appropriate containers to prevent light or oxygen exposure) or additives (buffers to optimize pH, antioxidants to limit oxidation). Controlled release systems offer several advantages over conventional drug administration approaches, including enhanced efficacy and cost-efficiency, reduction or elimination of unwanted side-effects, reduced frequency of administration, improved patient convenience and compliance and drug levels that are continuously maintained in a therapeutically desirable range (Langer, 1980). Despite their therapeutic promise, controlled release systems introduce new stabilization challenges. Many proposed carrier fabrication methods feature harsh conditions that can damage or denature the incorporated protein or compound, including the use of organic solvents, elevated temperatures, toxic cross-linking chemicals and vigorous agitation (Mehta et al., 2011; Fu et al., 2000). One of the most commonly investigated biodegradable polymers, poly-(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), degrades via hydrolysis to acidic products, producing low pH microclimates detrimental to drug stability (Zhu et al., 2000; Varde and Pack, 2007). During in vitro and in vivo release, reservoir systems encounter conditions detrimental to stability: high-concentration, hydration, elevated temperature (37°C) and extended timeframes (potentially months) (Fu et al., 2000; Bilati et al., 2005). For controlled and sustained release biomaterials, stabilization must therefore be achieved and maintained during: (1) fabrication of the protein or small molecule loaded carrier, (2) device storage, and (3) for the duration of intended release needs in vitro or in vivo.

While some of the techniques employed for conventional formulation can potentially be applied to polymer drug carriers (for example the inclusion of antacids in PLGA carriers to neutralize acidic degradation products (Zhu et al., 2000; Varde and Pack, 2007)), biomaterials systems which can themselves effectively stabilize proteins and small molecules would have several important biomedical applications. Improved stabilization during storage and sustained-release from drug carriers would improve the therapeutic efficacy and safety of unstable drugs like antibiotics and chemotherapeutics, particularly in developing-world clinical settings where refrigeration is limited. Immobilization of bioactive dopants like indicator dyes, enzymes and immunological proteins could potentially be built into analytical and diagnostic applications (Lawrence et al., 2008; Tsioris et al., 2010; Omenetto and Kaplan, 2008; Omenetto and Kaplan, 2010). Stabilization of enzymes used in industrial processes via polymer carriers would allow cost-efficient re-use of expensive enzymes or allow expanded utility in a variety of sensor and diagnostic applications (Saxena et al., 2010; Mateo et al., 2007). Stabilization of signaling molecules like growth factors and cytokines within tissue engineering scaffolds would enhance therapeutic outcomes (Chen et al., 2010b; Biondi et al., 2008). Given the nature of the potential applications, the need to develop platforms based on biocompatible, biodegradable materials is critical. A variety of natural polymers have been proposed for immobilization including cellulose, cross-linked dextrans, starch, tannin, agarose, chitin, chitosan, collagen, gelatin and albumin (Zhang, 1998; Acharya et al., 2008). However, no methods to date provide for immobilization in polymer biomaterial systems with the necessary combination of simplicity, versatility, tunability, biocompatibility and stabilizing effects on encapsulants.

Silk fibroin is a biologically-derived protein polymer purified from domesticated silkworm (Bombyx mori) cocoons that possesses many attractive features for immobilization. Silk exhibits excellent mechanical properties, biocompatibility (Leal-Egaña and Scheibel, 2010; Meinel et al., 2005; Panilaitis et al., 2003), optical properties (Lawrence et al., 2008; Omenetto and Kaplan, 2008) and biodegrades to non-toxic products via proteolysis (Wang et al., 2008a; Horan et al., 2005). Silk is edible, non-toxic and relatively inexpensive: Qian et al. successfully immobilized glucose oxidase using regenerated silk fibroin from the waste silk of a silk mill (Qian et al., 1996). A broad range of useful silk material formats can be prepared using mild, simple processes (Numata and Kaplan, 2010; Pritchard and Kaplan, 2011). The ambient, aqueous processing options utilized during silk protein preparation and materials fabrication represents a major advantage over other immobilization materials in that stable silk matrices can be prepared without conditions which can potentially degrade incorporated proteins and small molecules such as harsh temperature, pressure or chemicals (Liu et al., 1996; Qian et al., 1997; Demura et al., 1989; Lu et al., 2010). Unlike many biological derived proteins, silk is inherently stable to changes in temperature and moisture (Kuzuhara et al., 1987; Omenetto and Kaplan, 2010) and mechanically robust (Altman et al., 2003). The unique block copolymer structure of silk, consisting of large hydrophobic domains and small hydrophilic spacers, promotes self-assembly into organized nanoscale crystalline domains (β-sheets) separated by more flexible hydrophilic spacers. Proteins loaded in silk matrices may form hydrogen bonds with the silk fibroin protein, promoting protein stability. As a result, assembled silk fibroin offers a highly stabilizing environment for incorporated proteins and small molecules (Lu et al., 2009) providing the appropriate “molecularly crowded” environment for enzyme stabilization.

2. Silk based strategies to prevent chemical and structural degradation

Silk-based immobilization strategies to improve stability of compounds or proteins generally fall into four main categories. Note that these methods can also be combined. The choice of which approach or combination of approaches to use depends on the application and the properties of compound or protein being stabilized.

(1) Adsorption

Adsorption refers to attachment to the surface of the silk carrier by weak forces, such as van der Walls or hydrophobic interactions. Simple adsorption can be used to decorate silk surfaces with proteins or compounds of interest (Vepari and Kaplan, 2007). Adsorption has the advantages of mild processing, relatively ease and low cost. However, the extent of compound or protein immobilization will depend on the strength of the interaction between the compound or protein of interest and the silk.

(2) Covalent attachment

Silk fibroin can be functionalized using the amino acid side chain chemistry, particularly carbodiimide and diazonium chemistries, which uses amine or carboxyl groups on silk for modification. These modifications provide chemical handles for the covalent attachment of proteins and compounds to silk carriers, producing a stronger interaction between compound or protein and silk matrix compared with adsorption. Chemical reactions that have been used to modify the amino acids in silk proteins for various biomedical applications including conjugation of compounds and proteins to silk fibroin biomaterials have been reviewed elsewhere (Murphy and Kaplan, 2009).

(3) Entrapment in carriers

Entrapment (or “bulk-loading” as it is termed to in the field of drug delivery) refers to capture of the protein or compound of interest by mixing into the silk solution prior to material format preparation. Bulk loading most commonly involves the casting of films of the desired surface area and thickness from solutions of compound or protein and aqueous silk fibroin followed by drying and post-treatment to produce the desired material properties (Hofmann et al., 2006), while other silk material formats and processing options have also employed this method. Unlike chemical coupling, the protein or compound of interest is not covalently attached to the silk protein, but entrapment and encapsulation offer the advantage of isolating most of the loaded compound or protein from the bulk medium. Entrapment in silk film matrices is inexpensive, straightforward and applicable to a wide range of compounds or proteins. In addition, proteins or compounds of interest can be entrapped in silk carriers using mild, ambient, aqueous manufacturing conditions, preserving their bioactivity (Liu et al., 1996; Qian et al., 1997; Demura et al., 1989a; Hofmann et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2010). Bulk-loaded silk films can also be prepared such that the water-solubility of the silk film is retained (Kim et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010). This allows rapid recovery of compound loaded into silk storage matrices in applications where sustained release or long-term immobilization is not optimal. On the other hand, water insoluble silk carriers can be used for sustained release applications and applications where silk supports are required for longer duration (e.g. bone regeneration).

(4) Encapsulation in micro- or nano-particles

Comparable to entrapment, encapsulation refers to loading of a compound or protein of interest into silk micro- or nano-scale particles. For reviews of silk micro and nano-particle encapsulation, see Pritchard and Kaplan, 2011; Wenk et al., 2011 and Numata and Kaplan, 2010.

3. Protein and Peptide Stabilization by Silk

3.1. Enzymes

Stabilization of enzymes using silk biomaterials (particularly bulk-loaded films) has been reported for various enzymes (including horseradish peroxidase (HRP), glucose oxidase (GOx) and lipase) for industrial, medical, diagnostic and biosensor applications (Table 1). Note that the functionality of biosensors based on enzymes immobilized in silk film can be further improved by increasing matrix permeability to substrates, for example, through control of the secondary structure/beta-sheet content (Demura et al., 1989) or the addition of porogens like PEG, which improve diffusion of substrates through the membrane (Demura et al., 1991; Liu et al., 1996).

Table 1. Silk Stabilization of Enzymes.

| Enzyme Immobilized | Silk Immobilization Approach | Key Stabilization Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 75% ethanol) |

|

Qian et al., 1996 |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 75% ethanol) |

|

Qian et al., 1997 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 90% methanol) |

|

Hofmann et al., 2006 | |

| HRP gradients immobilized within three-dimensional silk fibroin sponges using either chemical coupling or adsorption |

|

Vepari and Kaplan, 2006 | |

| Bulk loaded silk microparticles (lipid template encapsulation) |

|

Wang et al., 2007 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed, cast on nanopatterned PDMS molds, dried; films rendered water insoluble by water annealing) |

|

Lawrence et al., 2008 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP mixed, case and dried; rendered water insoluble with 90% methanol) |

|

Lu et al., 2009 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed with or without 30% glycerol, cast and dried; films rendered water with water annealing, methanol or stretching) |

|

Lu et al., 2010 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed, cast on microneedle array PDMS molds, dried; films rendered insoluble by water annealing or methanol) |

|

Tsioris et al., 2011 | |

| Glucose oxidase (GOx) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and GOx solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 80% methanol or gluteraldehyde treatment) |

|

Kuzuhara et al., 1987 |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and GOx solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with stretching) |

|

Demura and Asakura, 1989 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and GOx solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with physical treatments: stretching, compressing and standing under high humidity and methanol-immersion treatment) |

|

Demura et al., 1989 | |

| Bulk loaded porous silk membrane (silk, GOx and PEG mixed, cast and dried) |

|

Demura and Asakura, 1991 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and GOx solutions mixed, cast and dried; method of rendering water insoluble not reported) |

|

Zhang et al., 1998 | |

| GOx bulk loaded in silk films and blended silk-poly(vinyl alcohol) films |

|

Liu et al., 1996 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP mixed, cast and dried; rendered water insoluble with 90% methanol) |

|

Lu et al., 2009 | |

| Lipase | Enzyme immobilized on silk fibers via cross-linking with glutaraldehyde |

|

Chatterjee et al., 2009 |

| Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP mixed, case and dried; rendered water insoluble with 90% methanol) |

|

Lu et al., 2009 | |

| Enzyme adsorped onto silk woven fabric: either PDMS-treated fiber (hydrophobic) or native fiber (hydrophilic) |

|

Chen et al., 2010 | |

| Cholesterol oxidase (ChOx) | Chemically coupled onto fibrous, porous woven silk mats |

|

Saxena et al., 2010 |

| Tyrosinase | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and enzyme solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with gluteraldehyde treatment) |

|

Acharya et al., 2008 |

| Ribonuclease | Chemically coupled to woven silk substrates |

|

Cordier et al., 1982 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | Immobilized on woven silk substrates by chemical or adsorption methods |

|

Grasset et al., 1983 |

| β-glucosidase | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and enzyme solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 50% ethanol) |

|

Miyairi et al., 1978 |

| Uricase | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and uricase solutions mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 80% methanol) |

|

Zhang et al., 1998 |

| Heme proteins (myoglobin, hemoglobin, horseradish peroxidase, and catalase) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and protein mixture cast on the surface of a graphite electrode, dried, rendered insoluble with 80% methanol) |

|

Wu et al., 2006 |

| L-asparaginase (ASNase) | Enzyme coupled covalently to silk fibroin powder with glutaraldehyde |

|

Zhang et al., 2005 |

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) | Bulk loaded silk microparticles (silk solution and enzyme solution mixed, salted out and filtered) (particle diameter <150 μm) |

|

Inoue et al., 1986 |

| Invertase | Bulk loaded silk fibroin powder (silk and enzyme hydrogel lyophilized, then ground to powder) |

|

Yoshimizu and Asakura, 1990 |

| Organophosphorus Hydrolase (OPH) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and OPH mixed, cast and dried; films rendered water insoluble with 30% ammonium sulfate) |

|

Dennis, et al. in preparation |

3.1.1. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)

Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) is widely used as an indicator enzyme in enzyme immunoassays, enzyme electrodes, effluent treatment and synthetic organics, but lacks stability in solution (Lu et al., 2009). The addition of silk solution to an HRP solution increased enzyme activity 30-40% and increased the half-life of HRP stored at room temperature to 25 days (compared with 2.5 hours for HRP in buffer alone) (Lu et al., 2009). Several authors have demonstrated that bioactivity of HRP is preserved when entrapped in silk films (Demura et al., 1989b; Qian et al., 1996; Qian et al., 1997; Hofmann et al., 2006; Lu et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2010). HRP activity was also preserved when incorporated via bulk-loading into silk optical gratings (Lawrence et al., 2008; Omenetto and Kaplan, 2008) and silk microneedle arrays (Tsioris et al., 2011), and when encapsulated in silk microspheres by means of a phospholipid template process (Wang et al., 2007). After 5 months of storage, HRP immobilized in silk films retained 24%, 22%, 17% of the initial activity when stored at 4°C, room temperature and 37°C, respectively. Stabilization was higher in untreated films than methanol treated films and higher in films with higher loading compared with low loading (Lu et al., 2009). The response of hydrogen peroxide sensors based on HRP immobilized in silk films only decreased 16% after 2 months of storage at 4°C (Qian et al., 1996). Lu et al. report retention of more than 90% of the initial enzymatic activity for HRP immobilized in silk films after 2 months at 37°C (Lu et al., 2010)

Vepari and Kaplan generated stable immobilized HRP gradients within three-dimensional silk fibroin sponges using either carbodiimide coupling of activated HRP or adsorption of HRP onto the silk substrate. After a 30 min incubation at 60°C, free enzyme lost all activity; compared to approx. 75% and 25% activity remaining (normalized to HRP activity at 25°C) for covalently coupled and adsorbed HRP, respectively. After 30 min incubation at 37°C, activity of HRP covalently coupled to silk sponges increased above 100%, consistent with the findings of Lu et al. that immobilization in silk can enhance apparent enzyme activity (possibly through renaturation of denatured protein) (Lu et al., 2009). A scaffold loaded with HRP via adsorption was incubated for 4 days in PBS solution to verify gradient stability; some desorption was observed but the gradient pattern was found to be intact. The simple, mild processes described for gradient immobilization of HRP onto silk sponges could be extended to a variety of proteins or small molecules (Vepari and Kaplan, 2006).

3.1.2. Glucose oxidase (GOx)

Glucose oxidase (GOx) is another important enzyme for biosensor applicationa. Several authors have demonstrated that immobilization of GOx in silk films dramatically improves the enzymes thermal and pH stability (Demura et al., 1989a; Kuzuhara et al., 1987; Zhang et al., 1998a; Lu et al., 2009). Demura et al. reported that GOx immobilized in fibroin films retained more than 90% relative activity after soaking in phosphate buffer at pH 7 at 4°C for 4 months. At 50°C, free enzyme loses 30% activity, while the relative activity of the immobilized enzyme scarcely changed (Demura et al., 1989). Kuzuhara et al. reported that immobilized GOx on fibroin retained 100% and 97% relative activity after 20 min incubation at 60°C and 70°C, respectively, compared with total activity loss above 6°C for free enzyme (Kuzuhara et al., 1987). GOx-immobilized in methanol treated silk films exhibited high storage stability: glucose detecting ability was retained for over 2 years in films stored at 4°C. Enzymatic activity was also maintained when GOx loaded silk films were immersed in buffers with varied pH (range of 5.0-10.0), exposed to temperatures from 20-50°C and used repeatedly for over 1,000 detections (Zhang et al., 1998a). GOx immobilized in silk films and blended silk-poly(vinyl alcohol) films exhibited improved pH stability and thermal stability compared with free GOx and GOx immobilized via glutaraldehyde crosslinking onto carbon electrodes. After 30 min incubation at 50°C, enzyme immobilized in silk membranes retained 93% activity, enzyme immobilized in silk-PVA blend films retained 86% activity and free enzyme activity dropped to 30% (Liu et al., 1996). Immobilization of GOx in silk fibroin not only improved thermal stability compared with free enzyme, but also improved stability compared with enzyme immobilized in gelatin films, which were unstable at elevated temperatures (Kuzuhara et al., 1987).

Perhaps most notably, Lu et al. report that for untreated films loaded with 1 wt% GOx, films stored at 4°C and 25°C exhibit slight activity loses during the first 3 months of storage, then during the remaining five months of storage, GOx activity increases above 100% of the initial activity. The authors attribute this observation to reversible denaturation of GOx in the original solution followed by renaturation upon interaction with the silk material. The authors also report that GOx stability is higher in untreated films compared with methanol treated films, possibly due to the optimal hydrophobic interactions between the GOx and silk allowing the enzyme to undergo structural changes (i.e. renaturation), as opposed to the more restrictive, highly hydrophobic and stacked β-sheet structures characteristic of methanol treated films (Lu et al., 2009).

3.1.3. Other enzymes

Lipase immobilized on silk fibers has successfully been used for hydrolysis of sunflower oil (Chatterjee et al., 2009) and hydrolysis of sunflower oil for the production of fatty acids (Chen et al., 2010a). Lipase immobilized by adsorption on woven silk fibers showed enhanced pH and temperature stability compared with soluble lipase (Chen et al., 2010a). Lipase immobilized on silk fibers via cross-linking with glutaraldehyde was stable for 2 months at 4°C (Chatterjee et al., 2009). At room temperature, activity of both the immobilized and free lipase declined, but the relative stability of the immobilized lipase was significantly higher than the free lipase. The crosslinking of lipase onto silk fibers resulted in the loss of 12% of activity, but the immobilized lipase could be reused even up to the third reaction cycle (Chatterjee et al., 2009). Cholesterol oxidase (ChOx) covalently immobilized onto fibrous, porous woven silk mats achieved remarkably high storage and operational stability. The half life (time at which 50% of initial activity remained) of the immobilized ChOx stored in a closed container at 4°C without being used was nearly 13 months (Saxena et al., 2010). Lu et al. reported significant activity retention for enzymes (lipase, glucose oxidase and horseradish peroxidase) entrapped in silk films over 10 months even at 37°C, and observed a correlation between silk protein processing and enzyme stability, suggesting that stability could be optimized via processing (Lu et al., 2009).

Silk fibroin has also proven to be an excellent substrate for tyrosinase immobilization, leading to higher conversion rates, high storage, pH and thermal stability and greater reusability. Under the same storage conditions, free enzyme lost all activity within 5 days, while immobilized enzyme retained approximately 75% of its original activity even after 10 days (Acharya et al., 2008). Ribonuclease immobilized onto woven silk substrates using diazo-coupling retained 63% of its activity after 7.2 months of storage in 0.1 M NaCl at 0-4°C (Cordier et al., 1982). Preparations of alkaline phosphatase immobilized on woven silk by covalent (diazo, azide, or glutaraldehyde) or adsorption methods retained bioactivity (Grasset et al., 1983). Stability of β-glucosidase entrapped in ethyl alcohol-treated silk films was protected against heating, electrodialysis and protease treatment (Miyairi et al., 1978). After 30 min incubation at 55°C, soluble enzyme lost approx. 50% of the initial activity, while immobilized enzyme lost only 10%. Exposure to papain reduced activity of soluble enzyme, but did not affect immobilized enzyme (Miyairi et al., 1978). An amperometric urate sensor based on uricase immobilized in silk fibroin membrane could be used repeatedly (more than 1,000 times), stored for over 2 years, and was stable in phosphate buffer for 3-4 months (Zhang et al., 1998b). Four heme-proteins (myoglobin, hemoglobin, horseradish peroxidase, and catalase) incorporated into regenerated SF films on graphite electrodes (GE) retained their ability to catalyze the reduction of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide. The investigation of UV–Vis and reflectance absorption infrared (RAIR) spectroscopy showed that the heme-proteins entrapped in silk maintained their native state and SEM and RAIR indicated that an intermolecular interaction existed between the heme-proteins and the fibroin (Wu et al., 2006).

Organophosphorus hydrolase (OPH) is a bacterial enzyme which holds promise as an effective agent for the bioremediation of organophosphates. Due to their potent neurotoxicity in both insects and higher organisms, organophosphates are produced on an industrial scale as pesticides and chemical warfare agents (reviewed in Singh et al., 2006). Regarding the later threat, coatings able to decontaminate and protect surfaces from nerve agent exposure while maintaining viability under a number of environmental conditions would be highly desirable. Towards this end, silk fibroin-entrapment of OPH has been tested for its ability to preserve enzymatic activity under hostile environmental conditions likely encountered by a surface coating. Silk fibroin-entrapped OPH is significantly stabilized during exposure to increased temperature and UV light when compared to the free enzyme (Dennis et al. in preparation). Additionally, the silk fibroin-entrapped OPH demonstrates remarkable tolerance to detergents and organic solvents. Thus, entrapment of OPH in silk fibroin not only increases enzyme stability under adverse environmental conditions, but also provides enzyme stability during the fabrications steps required to create surface coatings for decontamination and protection.

Silk-based enzyme stabilization approaches are also useful for stabilizing therapeutic enzymes, which might otherwise be difficult to safely and effectively administer. When the anti-leukemic enzyme L-asparaginase (ASNase) was coupled covalently with silk fibroin powder by glutaraldehyde, the conjugated enzyme exhibited enhanced thermostability, pH stability, storage stability and resistance to trypsin digestion. After 30 days at room temperature, unmodified enzyme only retained 20% of the original activity, while the fibroin conjugated enzyme retained more than 80% of the original activity. Further, covalent conjugation to silk powder increased the enzyme substrate affinity and circulating half-life compared with unmodified enzyme (Zhang et al., 2005). Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) was entrapped in silk fibroin microparticles (less than 150 microns diameter). Entrapped PAL was more stable than lyophilized free PAL: the remaining activity after 82-days storage at 4°C was 75.4 and 34.4% for entrapped and free PAL, respectively. In vitro results showed that PAL entrapped in silk fibroin gained resistance to chymotrypsin and trypsin proteolysis. Following oral administration of free and entrapped PAL, plasma levels of PAL's reaction product, cinnamate, were monitored to assess the in vivo enzyme activity. The entrapped enzyme, but not the free form, caused a significant rise of plasma cinnamate, suggesting the free enzyme lost bioactivity in vivo, but enzyme encapsulated in silk retained activity in the intestinal tract (Inoue et al., 1986).

3.2. Growth Factors

The goal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine is the induction of therapeutic tissue repair or restoration of tissue function by using scaffold substitutes that recapitulate the microenvironments of the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) (Chen et al., 2010b). Providing bioactive signals such as cytokines and growth factors can enhance therapeutic outcomes. However, growth factor (GF) delivery via systemic injection is limited by short half-life, rapid diffusion from the injection site and (if delivery is not localized) systemic side-effects (Chen et al., 2007). GFs are also susceptible to degradation in vivo due to harsh proteolytic environments. In addition to providing sustained and localized delivery, immobilization of GFs in polymer carriers might improve stability (Chen et al., 2010b).

The native ECM is known to act as a protective storage depot for growth factors and releases them “on demand” (Benoit and Anseth, 2005; Wenk et al., 2010). Sakesela et al reported that soluble bFGF was readily degraded by plasmin, whereas bFGF bound to the ECM component heparan sulfate was protected from proteolytic degradation. Heparin sulfate (a highly anionic, sulfated glycosaminoglycan that binds numerous growth factors, including bFGF) acts as a natural, protective growth factor “carrier” (Sakesela et al., 1988). Release of ECM-bound growth factor is regulated by ECM-degrading proteinases expressed by normal and malignant cells (i.e. platelets, neutrophils, lymphoma cells) (Vlodavsky et al., 1991; Whitelock et al., 1996). Similarly, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) is known to be entrapped in mineralized bone matrix during bone formation and actively released during bone remolding (Uebersax et al., 2008).

Based on this understanding of the native system, there is growing interest in biomimetic scaffolds that, like the ECM, support cell growth and also sequester and stabilize important bioactive signals like growth factors and cytokines (Chen et al., 2010b). In addition to providing superior physical support scaffolds for cell growth and proliferation (Wang et al., 2006), there is growing evidence that silk fibroin biomaterials possesses a remarkable ability to preserve the bioactivity of incorporated growth factors (Wenk et al., 2010), suggesting silk scaffolds could mimic the physiological role of the ECM, acting as storage for growth factors such as FGF-2, BMP-2 and VEGF, and releasing them in response to proteolysis. The mild, aqueous processing options for silk biomaterials described previously are well-suited to stabilization and delivery of fragile growth-factors.

In some cases, growth factor signaling may be enhanced when the growth factor is firmly attached to the biomaterial scaffold, whereas other growth factors achieve a stronger response in soluble form (Wenk et al., 2010). Accordingly, a range of silk immobilization strategies have been described. While storage stability for growth factor loaded silk biomaterials has not been reported, preservation of bioactivity (indicative of stabilization during fabrication and in vitro or in vivo release) has been extensively investigated (Table 2). Strong retention of growth factors by silk may be achieved by covalent coupling or, depending on the strength of the interaction between the growth factor and silk fibroin, simple adsorption or bulk loading.

Table 2. Silk Stabilization of Growth Factors.

| Growth Factor | Silk Scaffold Immobilization Approach | Bioactivity Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMP-2 | Adsorption or covalent coupling to silk films |

|

Karageorgiou et al., 2004 |

| Adsorption onto 3D porous aqueous-derived silk sponge |

|

Karageorgiou et al., 2006 | |

| Bulk loaded in electrospun silk nanofiber mats |

|

Li et al., 2006 | |

| Adsorption onto 3D porous HFIP-derived silk sponge |

|

Kirker-Head et al., 2007 | |

| Encapsulation in silk microspheres (prepared by ethanol precipitation method) |

|

Bessa et al., 2010 | |

| Bulk loaded silk hydrogels (gelation induced via sonication of aqueous silk solution) |

|

Diab et al., 2011 | |

| FGF-2 | Adsorption onto silk films (retention enhanced by chemical decoration of fibroin with sulfonic acid moieties) |

|

Wenk et al., 2010 |

| IGF-I | Bulk loaded porous 3D scaffolds (prepared by adding growth factors and silk mixture to porous molds, freeze-drying and immersing in 90% methanol) |

|

Uebersax et al., 2008 |

| Encapsulation in silk microspheres (prepared by laminar jet break-up of aqueous solutions, followed by water vapor annealing) |

|

Wenk et al., 2008 | |

| PTH | Chemical coupling to silk films |

|

Sofia et al., 2001 |

| bFGF | Adsorption onto 3D porous silk sponges (aqueous- or HFIP-derived) |

|

Wongpanit et al., 2010 |

| NGF | Bulk loaded porous tube-shaped scaffolds (prepared by freeze drying molds filled with aqueous solution of NGF and silk) |

|

Uebersax et al., 2007 |

| GDNF NGF | Bulk loaded silk film tubes |

|

Madduri et al., 2010 |

| BMP-2 IGF-I | Lipid template silk fibroin microspheres incorporated into aqueous-derived silk porous scaffolds using a gradient process |

|

Wang et al., 2009 |

| BMP-2 VEGF | Bulk loaded silk hydrogels (gelation induced via sonication of aqueous silk solution) |

|

Zhang et al., 2011 |

Abbreviations: BMP-2, Bone morphogenetic protein 2; FGF-2, Fibroblast growth factor 2; IGF-I, Insulin growth factor I; PTH, Parathyroid hormone; bFGF, Basic fibroblast growth factor; NGF, Nerve growth factor; GDNF, Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; pERK1/2, Phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinases; hMSC, Human mesenchymal stem cells; HFIP, 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol;

When BMP-2 was applied to porous silk sponges, 25% of the initial BMP-2 was firmly adsorbed to the scaffold. The authors attributed enhanced mineralization at the center of silk biomaterial sponges to retention of BMP-2 at the center of the sponge, suggesting absorption onto silk enhanced stability compared to soluble BMP-2 (Karageorgiou et al., 2006). Release behavior indicated that bFGF (Wongpanit et al., 2010) and NGF (Uebersax et al., 2007) also interacted strongly with silk fibroin. Wenk et al. enhanced retention of FGF-2 by silk by decorating fibroin with sulfonic acid moieties (analogous to the natural FGF-2- binding sulfated glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate in the ECM). This approach led to more than 99% FGF-2 retained up to 6 days and the potency of the growth factor (evaluated via reduced metabolic activities of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) and increased levels of pERK1/2) was exclusively retained when bound to films of sulfonated SF derivatives, demonstrating FGF-2 stabilization (Wenk et al., 2010).

Karageorgiou et al. compared immobilization of BMP-2 onto silk films via adsorption and covalent coupling. Adsorbed BMP-2 on silk films caused an increase in hMSC osteogenesis compared with controls (unmodified silk films), though less of an increase in hMSC osteogenesis than covalently coupled BMP-2 on silk films. Increased osteogenesis was also reported when hMSCs were seeded onto the surfaces of BMP-2-decorated films compared with hMSCs exposed to similar amounts of soluble BMP-2, which the authors attributed to enhanced growth factor stability and higher protein concentrations in the local microenvironment (Karageorgiou et al., 2004).

Bulk-loading has been used to prepare growth factor loaded porous silk sponges and silk microspheres, useful material formats for tissue engineering applications. The bioactivity of BMP-2 immobilized in electrospun silk nanofiber mats was preserved as evidenced by increased osteogenesis of hMSCs cultured for 31 days on BMP-2-loaded scaffolds compared with empty control scaffolds (Li et al., 2006). IGF-I loaded into highly porous three-dimensional silk scaffolds enhanced chondrogenic differentiation of hMSCs compared with hMSCs cultured on unloaded control silk scaffolds (Uebersax et al., 2008). Nerve growth factor (NGF)-loaded porous tube-shaped scaffolds for nerve guides prepared by freeze drying molds filled with aqueous solutions of NGF and silk supported PC12 cell differentiation with neurite outgrowth (Uebersax et al., 2007). In addition, the silk fibroin immobilization matrix was able to preserve IGF-I potency (Uebersax et al., 2008) and NGF potency (Uebersax et al., 2007) during methanol treatment of the scaffolds.

Bessa et al. encapsulated BMP-2, BMP-9 and BMP-14 in silk microspheres and confirmed the bioactivity of the eluted growth factor in vitro and in vivo (Bessa et al., 2010). Wenk et al. prepared loaded IGF-I into silk fibroin spheres using laminar jet break-up of aqueous solutions, followed by water vapor annealing. This mild encapsulation process resulted in preservation of bioactivity, as indicated by enhanced in vitro proliferation of MG-63 cells compared with controls (Wenk et al., 2008). Wang et al. incorporated silk fibroin microspheres loaded with BMP-2 and IGF-I into aqueous-derived silk porous scaffolds using a gradient process. Both growth factors formed deep and linear concentration gradients in the scaffolds and were shown to induce and control hMSC differentiation (Wang et al., 2009).

3.3. Other proteins and peptides

The silk-film based immobilization approaches described in the previous section can also be applied to the stabilization of other proteins, particularly immunological proteins for diagnostics and biosensors (Table 3). Low molecular weight Protein A (LPA) is a powerful immunological tool, but is highly thermally unstable in solution. The thermal stability of LPA immobilized in silk fibroin films was found to be higher than that of free LPA at high temperature based on immunoglobulin G (IgG)-binding affinity: at 120°C, fibroin immobilized LPS retained 50% of its relative IgG binding, while free LPA retains less than 20% (Kikuchi et al., 1999). Silk film optical gratings doped with hemoglobin and stored for 4 days at room temperature were studied for function. Preservation of the oxygen binding functionality of hemoglobin entrapped and stored in silk films was confirmed with an optical transmission experiment (Lawrence et al., 2008; Omenetto and Kaplan, 2008). Primary antibody immobilized and enriched at the surface of fibroin substrates was stored at 25°C in dry conditions for 4 weeks and found to retain approx. 40% of its secondary antibody binding activity (Lu et al., 2011). Green fluorescent protein entrapped in silk fibroin films was show to retain its nonlinear optical properties (Putthanarat et al., 2004).

Table 3. Silk Stabilization of Proteins.

| Protein Immobilized | Silk Immobilization Approach | Key Stabilization Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcal low molecular weight Protein A (LPA) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and protein solutions mixed, cast, dried; films rendered insoluble by water annealing) |

|

Kikuchi et al., 1999 |

| Hemoglobin | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and protein solutions mixed, cast on nanopatterned PDMS molds, dried; films rendered insoluble by water annealing) |

|

Lawrence et al., 2008 |

| Normal murine IgG | Immobilization and enrichment at the silk film surface via addition of antibody solution to the surface of a concentrated, partially dried, semi-solid silk film, followed by drying |

|

Lu et al., 2011 |

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk extracted from silkworm glands and diluted, silk and protein solutions mixed, cast and annealed at 20°C) |

|

Putthanarat et al., 2004 |

| NeutrAvidin | Chemically coupled to silk microspheres and to silk protein in solution prior to hydrogel formation |

|

Wang et al., 2011 |

| Insulin | Covalently coupled to silk fibroin powder using gluteraldehyde |

|

Zhang et al., 2006 |

| Murine anti-TGFb IgG1 monoclonal antibody | Bulk loaded silk hydrogels (gelation induced by sonication) |

|

Guziewicz et al., 2011 |

A carbodiimide-based coupling strategy was employed to couple NeutrAvidin with silk fibroin in solution or with silk microspheres. NeutrAvidin coupled to silk fibroin solution or silk microspheres retained the ability to bind biotin, including fluorescently labeled biotin (Atto 610), biotinylated-HRP and biotinylated anti-CD3 antibody (the latter functionalization resulted in specific binding of the functionalized silk microspheres to CD3-positive T-lymphocytic cells) (Wang et al., 2011). Insulin was covalently coupled to silk fibroin powder using gluteraldehyde and the resulting insulin-fibroin conjugate showed much higher recovery (about 70%) and physicochemical and biological stability insulin coupled to bovine serum albumin (BSA) or unmodified insulin. In vitro plasma half-lives of insulin alone, BSA-insulin, and fibroin-insulin were 16, 20, and 34 h, respectively. The pharmacological activity of the SF-Ins bioconjugates in diabetic rats evidently was about 3.5 times as long as that of the native insulin (Zhang et al., 2006).

Unlike other gelation processes, which require harsh conditions to crosslink polymer chains, sonication-induced silk hydrogels form physical crosslinks without exposing the incorporated therapeutic to stresses such as shear, temperature or organic solvents (Wang et al., 2008b). As such, silk hydrogels are an attractive immobilization matrix for fragile proteins. NeutrAvidin decorated silk fibroin retained its ability to self-assemble into hydrogel after reaction (Wang et al., 2011). Guziewicz et al. loaded monoclonal antibodies into sonicated silk and lyophilized the antibody loaded silk hydrogels to further improve long-term storage stability. The bioactivity of the antibody released from the silk lyophilized gels was confirmed in a cell-based bio-assay (Guziewicz et al., 2011).

4. Small Molecule Stabilization by Silk

Stabilization of small molecules presents different challenges than protein stabilization. Unlike proteins, which can lose bioactivity when structural loss occurs, small molecule degradation predominantly occurs via chemical degradation. However, the unique physical properties of silk can also improve the stability of small molecules, including dyes and pigments, antioxidants, antibiotics and chemotherapeutics (Table 4).

Table 4. Silk Stabilization of Small Molecules.

| Small Molecule Immobilized | Silk Immobilization Approach | Key Stabilization Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine | Drug encapsulated into silk microspheres, loaded into silk sponges and coated with drug-loaded silk films |

|

Wilz et al., 2008; Szybala et al., 2009 |

| Chlorophyll a β-carotene Astaxanthin | Adsorption onto silk powder |

|

Ishii et al., 1995 |

| Antioxidants from crude olive leaf extract (oleuropein and rutin) | Adsorption onto silk powder |

|

Bayçin et al., 2010 |

| Doxycycline Ciprofloxacin | Adsorption onto silk fibers |

|

Choi et al., 2004 |

| Curcumin | Encapsulated in silk nanoparticles |

|

Gupta et al., 2009 |

| Various antibiotics (penicillin, tetracycline, rifampicin, erythromycin) | Various immobilization approaches, including bulk loading, adsorption and encapsulation |

|

Pritchard et al., in preparation |

| Tetracycline | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and antibiotic solutions mixed, cast on microneedle array PDMS molds, dried; films rendered insoluble by water annealing or methanol) |

|

Tsioris et al., 2011 |

| Doxorubicin | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and antibiotic solutions mixed, cast on microprism array (MPA) PDMS molds, dried; films rendered insoluble by water annealing) |

|

Tao et al., submitted |

| Phenol-sulfon-phthlein (Phenol Red) | Bulk loaded silk films (silk and HRP solutions mixed, cast on nanopatterned PDMS molds, dried; films rendered insoluble by water annealing) |

|

Lawrence et al., 2008 |

| 4-amino-benzoic acid | Chemically coupled to silk film |

|

Tsioris et al., 2010 |

Though relatively stable in solution (Kaltenbach et al., 2011), the small molecule anticonvulsant adenosine is cleared rapidly and has a short half-life when injected. However, sustained in vivo effects were observed when adenosine was encapsulated in silk microspheres suspended in silk sponges and implanted in the hippocampi of kindled epileptic rats. A dose dependent delay in seizure acquisition was observed (Wilz et al., 2008) and implants designed to release 1000 ng adenosine a day completely protected kindled rats from seizures over a 10-day period (Szybala et al., 2009). These studies demonstrated that encapsulation in silk drug carriers represents a safe and effective strategy to sustain adenosine activity at the site of intended action, counteracting rapid local clearance.

Natural pigments such as chlorophyll or carotenoids are attractive due to their safety and biocompatibility, but are less widely used than their synthetic counterparts due to their extreme light-instability once extracted from living bodies. Pigment-fibroin conjugates prepared by adsorbing chlorophyll a, β-carotene and astaxanthin onto silk fibroin exhibited high stability to visible and UV light, while fibroin-free pigments were rapidly decolorized by UV light irradiation. The authors attribute this improvement in pigment stability to fibroin's ability to substitute for the proteins that naturally stabilize these materials in vivo (Ishii et al., 1995). Immobilization of the oleuropein and rutin from crude olive leaf extract onto silk fibroin was investigated both to purify olive leaf antioxidants and to create an edible, safe, stable of protein-bioactive phytochemical conjugate with antioxidative, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties. After adsorption of olive leaf antioxidants, the functionalized silk fibroin exhibited antioxidative and antimicrobial activity. Further, the antioxidant activity of desorbed polyphenols purified from the extract using silk was nearly 2 times higher than that of the olive leaf extract containing the same amount of desorbed polyphenols (Bayçin et al., 2010).

Choi et al. immobilized two antibiotics (doxycycline and ciprofloxacin) onto silk fibers using a range of conditions and found that doxycycline and ciprofloxacin “dyed” silk fibers were able to inhibit local growth of Staphylococcus epidermis lawns on agar plates for at least 48 or 24 hours, respectively (Choi et al., 2004). Encapsulation in silk preserved curcumin's bioactivity, and improved intracellular uptake and drug efficacy; curcumin packaged into silk nanoparticles (<100 nm) reduced breast cancer viability in vitro (Gupta et al., 2009). Recently, the capacity of silk carriers to sequester, stabilize and release bioactive antibiotics was studied (Pritchard et al., in preparation). Incorporation of penicillin and tetracycline into silk films dramatically improved stability compared with storage in solution, and also improved stability compared with storage as dry powder. Stabilization and protection persisted above physiological temperatures (e.g., up to 60°C) and for extended time frames (e.g., up to 6 to 9 months). Preservation of bioactivity during carrier fabrication and drug release was also confirmed for sponges loaded with rifampicin and erythromycin. The latter, though highly unstable in aqueous media (Briseart et al., 1996), continued to inhibit S. aureus growth up to 35 days despite being incubated at 37°C for over a month in a hydrated silk sponge (Pritchard et al., in preparation). Tetracycline bioactivity was also preserved during fabrication of silk microneedle arrays and subsequent in vitro release studies in Staphylococcus aureus lawns (Tsioris et al., 2011).

Because silk film encapsulation and/or immobilization stabilized incorporated compound function, doping strategies can be built into silk optical devices to produce multi-functional, biodegradable devices for applications like diagnostics and biosensors. Silk films patterned with micro-prism arrays (MPA) were shown to provide enhanced optical signal through tissues and could be functionalized with inclusion of the chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin for combined therapy and monitoring. Loading of the doxorubicin into silk MPAs dramatically enhanced storage stability compared with storage in solution: after 3 weeks stored at -20°C (frozen) and 60°C, the fluorescence of the doxorubicin stored in silk films did not significantly decrease at either storage temperature, while less than 80% and 30% of fluorescent doxorubicin remained for storage in solution at -20°C and 60°C, respectively (Tao et al., submitted). Lawrence et. al integrated biological substances into specialized optical elements prepared by casting aqueous silk solution and analyzed the functionality of the incorporated substances within the solidified silk films. By casting on diffractive molds, optical properties of the patterned silk film and biological function of the dopant could be consolidated into a single multi-functional biomaterial device. When the small molecule organic pH indictor phenolsulfonphthlein (Phenol Red) was incorporated into a patterned silk grating, both the optical function and functionality of the small molecule dopant were retained. The optical function of the diffraction grating was confirmed by showing propagating supercontinuum radiation onto the grating, while the pH sensing capability of the incorporated Phenol Red was shown through variations of the spectrum correlated to the acidty of the dip solution when gratings were immersed into solutions of different pH (Lawrence et al., 2008). Similarly, silk protein was chemically modified with 4-aminobenzoic acid to perform pH sensing in active optofluidic devices. The modified silk was found to be stable and spectrally responsive over a wide pH range (Tsioris et al., 2010)

5. Proposed Mechanisms of Silk-Based Stabilization

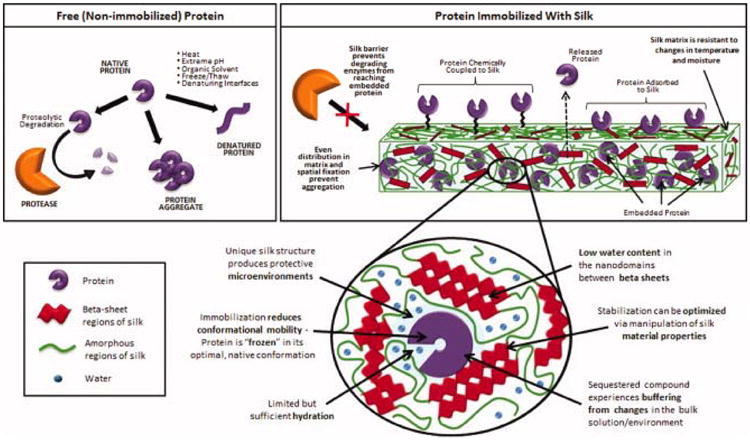

There are many potential sources of protein or small molecule instability, and silk may exert a combination of different stabilizing effects. As described earlier, preservation of bioactivity during silk device fabrication may be attributed to the use of mild, aqueous processing options made possible due to the unique chemistry, structure and assembly of silk into nanodomains with reduced water content (Figure 1). The following mechanisms (or, more likely, a combination of the following mechanisms) have been proposed to explain the stabilization effects of immobilization or conjugation with silk fibroin during storage and duration in vitro or in vivo release or exposure (silk stabilization effects are also summarized in Figure 1):

Figure 1. Physical and chemical aspects of stabilization of compounds in silk.

Protective Barrier Effects

At their intended site of action, proteins and small molecules may be subject to enzymatic clearance and degradation, for example the proteolytic enzymes encountered in the GI tract during oral administration or the antibiotic-degrading β-lactamase enzymes released by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Turos et al., 2007). Once immobilized in silk carriers, the susceptibility of small molecules and proteins to enzymatic degradation decreases dramatically due to their reduced accessibility to exogenous enzymes. Protective effects may also result from the silk protein binding inactivators, as has been described for high concentrations of hemoglobin or albumin. Immobilization also protects most of the incorporated small molecules or protein from the external interface, reducing air-water interface or oil-water interface related instability.

Reduced Mobility Effects

Dehydration (i.e. via lyophilization or small molecule storage in a dry powder state) is believed to stabilize small molecules and proteins by reducing molecular mobility. Immobilization in or on a solid silk matrix, particularly when the drug carrier is stored in a dehydrated state, has a comparable stabilization effect on encapsulants, especially proteins. Aggregation is a common source of protein inactivation. Small molecules may also form aggregates that fall out of solution, thereby losing activity. When proteins or small molecules are dispersed in or attached to silk matrices, mutual spatial fixation and reduction of molecular mobility prevent aggregation. Another major source of protein activity loss (particularly in response to heating, pH shifts and denaturing agents like organic solvents) is unfolding, i.e. conformational change of the protein's structure. Immobilization (either through entrapment, adsorption or chemical coupling to the silk biomaterial surface) would be expected to increase protein rigidity and reduce conformational mobility. This “freezing” of the protein in its optimal, native structure and reduced molecular mobility reduces protein unfolding compared to free proteins, thereby improving thermal stability. This explanation also describes reduced dissociation of immobilized multimeric proteins, particularly when proteins are entrapped; attachment to polymer surfaces will only reduce dissociation is all the subunits are attached. Hydrogen bond formation between imbedded proteins and the silk fibroin protein may further reduce mobility and promote protein stability.

Microenvironment Effects

Encapsulation in polymer matrices (particularly silk due to its unique structure) produces protective microenvironments. Embedded proteins and small molecules sequestered in these microenvironments are expected to experience a degree of buffering from changes that occur in the bulk solution. Improved storage, more stable conditions in fibroin matrix microenvironments may contribute to increased stabilization against pH inactivation, organic solvents and hydrogen peroxide. Further, the dominating hydrophobic nature of silk proteins excludes water from the crystallized beta sheet domains, while also limiting water content in the less crystalline yet still hydrogen bonded spacers or more hydrophilic regions. Since these structural features remain nanoscale in size, water content available to denature or resolubilize entrapped compounds is limited.

Table 5 summarizes the types of silk-based stabilization investigated by authors covered in this review. Processing stability refers to any demonstration that bioactivity or structure of the incorporated compound or protein are preserved during the fabrication of the carrier (i.e., during bulk-loading into films or sponges, encapsulation in micro- or nano-particles, chemical coupling or crosslinking or adsorption). Storage stability designates studies that investigated stabilization during simulated storage. Enhanced thermostability is categorized as storage stability even at temperatures above intended storage conditions, as it provides accelerated degradation information. Operational stability refers to retention of activity during use of the immobilized protein or small molecule. For immobilized enzymes or biosensors, operational stability can include evidence of stability during repeated industrial processing cycles or diagnostic tests. For therapeutic compounds or proteins (silk drug carriers or scaffolds), sustained release or increased duration of and in vitro or in vivo effect compared with administration of soluble protein or small molecule is categorized as operational stability. Enhanced resistance to proteolysis is also categorized as operational stability, as proteases are unlikely to be encountered during long-term storage. Enhanced pH stability is classified as operational stability and enhanced light stability is classified as storage stability. A plus sign (+) indicates that the study provided evidence of stabilization effects in this category. A minus sign (-) indicates that the study did not provide evidence of stabilization in this category, not that the study provided evidence that stabilization effects did not occur in this category. For example, if bioactivity of a protein-loaded silk scaffold is demonstrated in vitro or in vitro with no mention of a storage period post-fabrication, the study is considered to have included evidence of processing stability and operational stability (bioactivity was maintained during fabrication, and retained during in vitro culture of cells or in vivo implantation), but not storage stability.

Table 5. Summary of Silk Stabilization Effects: Processing, Storage and Operational Stability.

| Protein or Compound Immobilized | Silk Material Format | Stabilization Effects | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing Stability | Storage Stability | Operational Stability | |||

| Enzymes – Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | |||||

| Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Qian et al., 1996 |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Qian et al., 1997 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | - | + | Hofmann et al., 2006 | |

| Chemical coupling or adsorption onto silk sponges | + | + | + | Vepari and Kaplan, 2006 | |

| Microparticle encapsulation | + | - | + | Wang et al., 2007 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (nanopatterned) | + | - | - | Lawrence et al., 2008 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Lu et al., 2009 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Lu et al., 2010 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films (microneedle arrays) | + | - | + | Tsioris et al., 2011 | |

| Enzymes – Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | |||||

| Glucose oxidase (GOx) | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Kuzuhara et al., 1987 |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Demura and Asakura, 1989 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Demura et al., 1989 | |

| Bulk loaded porous silk films | + | - | - | Demura and Asakura, 1991 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Zhang et al., 1998 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films and blended silk-PVA films | + | + | + | Liu et al., 1996 | |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Lu et al., 2009 | |

| Other Enzymes | |||||

| Lipase | Glutaraldehyde crosslinking onto silk fibers | + | + | + | Chatterjee et al., 2009 |

| Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Lu et al., 2009 | |

| Adsorption onto silk woven fabric | + | + | + | Chen et al., 2010 | |

| Cholesterol oxidase | Chemical coupling onto woven silk substrates | + | + | - | Saxena et al., 2010 |

| Tyrosinase | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Acharya et al., 2008 |

| Ribonuclease | Chemical coupling onto woven silk substrated | + | + | - | Cordier et al., 1982 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Chemical coupling or adsorption onto woven silk substrates | + | - | - | Grasset et al., 1983 |

| β-glucosidase | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Miyairi et al., 1978 |

| Uricase | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Zhang et al., 1998 |

| Heme proteins (myoglobin, hemoglobin, horseradish peroxidase, and catalase | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Wu et al., 2006 |

| L-asparaginase (ASNase) | Glutaraldehyde crosslinking to silk powder | + | + | + | Zhang et al., 2005 |

| Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) | Encapsulation silk particles | + | + | + | Inoue et al., 1986 |

| Invertase | Bulk loaded silk hydrogel, lyophilized, then ground to powder | + | + | - | Yoshimizu and Asakura, 1990 |

| Organo-phosphorus Hydrolase (OPH) | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Dennis et al., in preparation |

| Growth Factors | |||||

| BMP-2 | Adsorption onto silk films or covalent coupling onto silk films | + | - | + | Karageorgiou et al., 2004 |

| Adsorption onto 3D porous silk sponge | + | - | + | Karageorgiou et al., 2006 | |

| Bulk loaded in electrospun silk nanofiber mats | + | - | + | Li et al., 2006 | |

| Adsorption onto 3D porous silk sponge | + | - | + | Kirker-Head et al., 2007 | |

| Encapsulation in silk microspheres | + | - | + | Bessa et al., 2010 | |

| Bulk loaded silk hydrogels (gelation induced via sonication of aqueous silk solution) | + | - | + | Diab et al., 2011 | |

| FGF-2 | Adsorption onto silk films (retention enhanced by chemical decoration of fibroin with sulfonic acid moieties) | + | - | + | Wenk et al., 2010 |

| IGF-I | Bulk loaded porous 3D scaffolds | + | - | + | Uebersax et al., 2008 |

| Encapsulation in silk fibroin microspheres | + | - | + | Wenk et al., 2008 | |

| PTH | Chemical coupling to silk films | + | - | + | Sofia et al., 2001 |

| bFGF | Adsorption onto 3D porous silk sponges (aqueous- or HFIP-derived) | - | - | + | Wongpanit et al., 2010 |

| NGF | Bulk loaded porous tube-shaped scaffolds f | + | - | + | Uebersax et al., 2007 |

| GDNF NGF | Bulk loaded silk film tubes | + | - | + | Madduri et al., 2010 |

| BMP-2 IGF-I | Lipid template silk fibroin microspheres incorporated into aqueous-derived silk porous scaffolds using a gradient process | + | - | + | Wang et al., 2009 |

| BMP-2 VEGF | Bulk loaded silk hydrogels (gelation induced via sonication of aqueous silk solution) | + | - | + | Zhang et al., 2011 |

| Other Proteins | |||||

| Low mol. wt. Protein A (LPA) | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | + | Kikuchi et al., 1999 |

| Hemoglobin | Bulk loaded silk films | + | - | - | Lawrence et al., 2008 |

| IgG | Immobilization and enrichment on the silk film surface | + | + | - | Lu et al., 2011 |

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | Bulk loaded silk films | + | - | - | Putthanarat et al., 2004 |

| NeutrAvidin | Chemically coupled to silk microspheres and silk protein in solution | + | - | + | Wang et al., 2011 |

| Insulin | Coupled to silk fibroin powder gluteraldehyde | + | - | + | Zhang et al., 2006 |

| Murine anti-TGFb IgG1 monoclonal antibody | Bulk loaded sonication-induced silk hydrogels | + | - | - | Guziewicz et al., 2011 |

| Small Molecules | |||||

| Adenosine | Encapsulated into silk microspheres loaded into silk sponges and coated with drug-loaded silk films | + | - | + | Wilz et al., 2008; Szybala et al., 2009 |

| Chlorophyll a β-carotene Astaxanthin | Adsorption onto silk powder | + | + | - | Ishii et al., 1995 |

| Oleuropein Rutin | Adsorption onto silk powder | + | - | + | Bayçin et al., 2010 |

| Doxycycline Ciprofloxacin | Drugs “dyed” onto silk fibers | + | - | + | Choi et al., |

| Curcumin | Encapsulated with silk nanoparticles | + | - | + | Gupta et al., 2009 |

| Penicillin, Tetracycline Rifampicin Erythromycin | Bulk-loaded silk films and adsorption | + | + | + | Pritchard et al., in preparation |

| Tetracycline | Bulk loaded silk films | + | - | + | Tsioris et al., 2011 |

| Doxorubicin | Bulk loaded silk films | + | + | - | Tao et al., submitted |

| Phenolsulfon-phthlein (Phenol Red) | Bulk loaded silk films | + | - | - | Lawrence et al., 2008 |

| 4-amino-benzoic acid | Chemically coupled to silk films | + | - | - | Tsioris et al., 2010 |

6. Conclusions

In addition to its ability to support cell growth as a tissue engineering scaffold and to sustain and control release as a drug carrier for controlled-release implants, silk fibroin possesses a unique ability to stabilize immobilized proteins (especially enzymes and growth factors) and small molecules. Silk immobilization via covalently coupling, adsorption, entrapment or encapsulation enhances the stability of small molecule and proteins against heat, pH and proteolysis. The use of mild, aqueous processing options stabilizes during silk carrier fabrication, while a combination of protective barrier, microenvironment and reduced compound or protein mobility enhance stabilization during storage and exposure to in vitro, in vivo or operational conditions. Given the exceptional capacity of silk to stabilize sensitive incorporated compounds, we anticipate silk biomaterials will be attractive carriers for gene delivery, vaccines and volatile flavors and fragrances.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NSF, the NIH and the AFOSR for support for various aspects of studies that form the basis for this review.

References

- Acharya C, Kumar V, Sen R, Kundu SC. Biotechnol J. 2008;3:226–233. doi: 10.1002/biot.200700120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman GH, Diaz F, Jakuba C, Calabro T, Horan RL, Chen J, Lu H, Richmond J, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2003;24:401–416. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayçin D, Altiok E, Ülkü S, Bayraktar O. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:1227–1236. doi: 10.1021/jf062829o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit DSW, Anseth KS. Acta Biomaterialia. 2005;1:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessa PC, Balmayor ER, Hartinger J, Zanoni G, Dopler D, Meinl A, Banerjee A, Casal M, Redl H, Reis RL, vanGriensven M. Tissue Eng C Methods. 2010;16:937–945. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilati U, Allémann E, Doelker E. Eur Journal Pharm Biopharm. 2005;59:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi M, Ungaro F, Quaglia F, Netti PA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisaert M, Heylen M, Plaizier-Vercammen J. Pharm World Sci. 1996;18:182–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00820730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Barbora L, Cameotra SS, Mahanta P, Goswami P. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;157:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8405-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Lin H, Wang J, Zhao Y, Wang B, Zhao W, Sun W, Dai J. Biomaterials. 2007:1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Yin C, Cheng Y, Li W, Cao Z, Tan T. Biomass Bioenerg. 2010a in press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen FM, Zhang M, Wu ZF. Biomaterials. 2010b;31:6279–6308. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HM, Bide M, Phaneuf M, Quist W, Logerfo F. Textile Res J. 2004;74:333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cordier, D.; Couturier, R.; Grasset, L.; Ville, A. 1982, 4, 249-255.

- Demura M, Asakura T, Kuroo T. Biosensors. 1989a;4:361–372. [Google Scholar]

- Demura M, Asakura T, Nakamura E, Tamura H. J Biotechnol. 1989b;10:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Demura M, Asakura T. J Membrane Sci. 1991;59:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, P.B.; Walker, A.Y.; Dickerson, M.B.; Kaplan, D.L.; Naik, R.R. in preparation

- Diab' T, Pritchard EM, Uhrig BA, Boerckel JD, Kaplan DL, Guldberg RE. J Mech Behav Biomed. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.11.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu K, Klibanov AM, Langer R. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:24–25. doi: 10.1038/71875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasset L, Cordier D, Couturier R, Ville A. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1983;25:1423–1434. doi: 10.1002/bit.260250520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Aseh A, Ríos CN, Aggarwal BB, Mathur AB. Int J Nanomedicine. 2009;4:115–122. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guziewicz N, Best A, Perez-Ramirez B, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2642–2650. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S, Foo CT, Rossetti F, Textor M, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL, Merkle HP, Meinel L. J Control Release. 2006;111:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan RL, Antle K, Collette AL, Wang Y, Huang J, Moreau JE, Volloch V, Kaplan DL, Altman GH. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3385–3393. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S, Matsunaga Y, Iwane H, Sotomura M, Nose Y. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1986;141:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(86)80349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Furukawa M, Matsushima A, Kodera Y, Yamada A, Kanai H, Inada Y. Dyes Pigments. 1995;27:211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach M, Hutchinson DJ, Bollinger JE, Zhao F. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:1533–1536. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgiou V, Meinel L, Hofmann S, Malhotra A, Volloch V, Kaplan DL. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71:528–537. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karageorgiou V, Tomkins M, Fajardo R, Meinel L, Snyder B, Wade K, Chen J, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;78:324–334. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi J, Mitsui Y, Asakura T, Hasuda K, Araki H, Owaku K. Biomaterials. 1999;20:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Kim YS, Amsden J, Panilaitis B, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG, Zakin MR, Rogers JA. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;95:133701–133703. doi: 10.1063/1.3238552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Viventi J, Amsden JJ, Xiao JL, Vigeland L, Kim YS, Blanco JA, Panilaitis B, Frechette ES, Contreras D, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG, Huang YG, Hwang KC, Zakin MR, Litt B, Rogers JA. Nat Mater. 2010;9:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nmat2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirker-Head C, Karageorgiou V, Hofmann S, Fajardo R, Betz O, Merkle HP, Hilbe M, von Rechenberg B, McCool J, Abrahamsen L, Nazarian A, Cory E, Curtis M, Kaplan D, Meinel L. Bone. 2007;41:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.04.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klibanov AM. Anal Biochem. 1979;93:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzuhara A, Asakura T, Tomoda R, Matsunaga T. J Biotechnol. 1987;5:199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Langer R. Chem Eng Commun. 1980;6:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence BD, Cronin-Golomb M, Georgakoudi I, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1214–1220. doi: 10.1021/bm701235f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Egaña A, Scheibel T. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2010;55:155–167. doi: 10.1042/BA20090229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Vepari C, Jin HJ, Kim HJ, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3115–3124. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang X, Liu H, Yu T, Deng J. J Biotechnol. 1996;46:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lu SZ, Wang X, Uppal N, Kaplan DL, Li MZ. Front Mater Sci China. 2009;3:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Wang X, Hu X, Cebe P, Omenetto F, Kaplan DL. Macromol Biosci. 2010;10:359–68. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200900388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Wang X, Zhu H, Kaplan DL. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7:2782–2786. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madduri S, Papaloïzos M, Gander B. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2323–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo C, Paloma JM, Fernandez-Lorente G, Guisan JM, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2007;40:1451–1463. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta SK, Kaur G, Verma A. Colloid Surface A. 2011;375:219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Meinel L, Hofmann S, Karageorgiou V, Kirker-Head C, McCool J, Gronowiz G, Zichner L, Langer R, Vanjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2005;26:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyairi S, Sugiura M, Fukui S. Agric Biol Chem. 1978;42:1661–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy AR, Kaplan DL. J Mater Chem. 2009;23:6443–6450. doi: 10.1039/b905802h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numata K, Kaplan DL. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62:1497–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Nature Photon. 2008;2:641–643. [Google Scholar]

- Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Science. 2010;329:528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1188936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panilaitis B, Altman GH, Chen J, Jin HJ, Karageorgiou V, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3079–3085. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard EM, Kaplan DL. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:797–811. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.568936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, E.M.; Valentin, T.; Panilaitis, B.; Omenetto, F.; Kaplan, D.L. In preparation

- Putthanarat S, Eby RK, Naik RR, Juhl SB, Walker MA, Peterman E, Ristich S, Magoshi J, Tanaka T, Stone MO, Farmer BL, Brewer C, Ott D. Polymer. 2004;45:8451–8457. [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Liu Y, Liu H, Yu T, Deng J. Anal Biochem. 1996;236:208–214. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Liu Y, Liu H, Yu T, Deng J. Biosens Bioelectron. 1997;12:1213–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Saksela O, Moscatelli D, Sommer A, Rifkin DB. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:743–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.2.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena U, Goswami P. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;162:1122–1131. doi: 10.1007/s12010-010-8923-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BK, Walker A. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:428–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofia S, McCarthy MB, Gronowicz G, Kaplan DL. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;54:139–148. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200101)54:1<139::aid-jbm17>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szybala C, Pritchard EM, Lusardi TA, Li T, Wilz A, Kaplan DL, Boison D. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao H, Siebert SM, Pritchard EM, Sassaroli A, Panilaitis BJB, Brenckle MA, Amsden JJ, Fantini S, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG. Nature Mater. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Tsioris K, Tilburey GE, Murphy AR, Domachuk P, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:1083–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Tsioris K, Raja WK, Pritchard EM, Panilaitis B, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG. Adv Mater. 2011 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Turos E, Reddy GSK, Greenhalgh K, Ramaraju P, Abeylath SC, Jang S, Dickey S, Lim DV. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:3468–3472. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebersax L, Mattotti M, Papaloizos M, Merkle HP, Gander B, Meinel L. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4449–4460. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebersax L, Merkle HP, Meinel L. J Control Release. 2008;127:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varde NK, Pack DW. J Control Release. 2007;124:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vepari CP, Kaplan DL. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006;93:1130–1137. doi: 10.1002/bit.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vepari CP, Kaplan DL. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:991–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlodavsky I, Fuks Z, Ishai-Michaeli R, Bashkin P, Levi E, Korner G, Bar-Shavit R, Klagsbrun M. J Cell Biochem. 1991;45:167–176. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kimi HJ, Vunjak-Novaokovic G, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2006;27:6064–6084. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wenk E, Matsumoto A, Meinel L, Li C, Kaplan DL. J Control Release. 2007;117:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Rudym DD, Walsh A, Abrahamsen L, Kim HJ, Kim HS, Kirker-Head C, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2008a;29:3415–3428. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kluge JA, Leisk GG, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2008b;29:1054–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wenk E, Zhang X, Meinel L, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. J Control Release. 2009;134:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kaplan DL. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11:100–110. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk E, Wandrey AJ, Merkle HP, Meinel L. J Control Release. 2008;132:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk E, Murphy AR, Kaplan DL, Meinel L, Merkle HP, Uebersax L. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1403–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk E, Merkle HP, Meinel L. J Control Release. 2011;150:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelock JM, Murdoch AD, Iozzo RV, Underwood PA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10079–10086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilz A, Pritchard EM, Li T, Lan JQ, Kaplan DL, Boison D. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3609–3616. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongpanit P, Ueda H, Tabata Y, Rujiravanit R. J Biomat Sci. 2010;21:1403–1419. doi: 10.1163/092050609X12517858243706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Shen Q, Hu S. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;558:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimizu H, Asakura T. J Applied Polym Sci. 1990;40:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ. Biotechnol Adv. 1998;16:961–971. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Zhu J, Gu RA. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1998a;75:215–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02787776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Shen Wei De, Gu Ren Ao, Zhu Jiang, Xue Ren Yu. Analytica Chimica Acta. 1998b;369:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Zhou WL, Shen WD, Chen YH, Zha XM, Shirai K, Kiguchi K. J Biotechnol. 2005;120:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]