Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) control intestinal smooth muscle contraction to regulate gut motility. ICC within the plane of the myenteric plexus (ICC-MY) arise from c-Kit-positive progenitor cells during mouse embryogenesis. However, little is known about the ontogeny of ICC associated with the deep muscle plexus (ICC-DMP) in the small intestine and ICC associated with the submucosal plexus (ICC-SMP) in the colon. Leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domains protein 1 (LRIG1) marks intestinal epithelial stem cells, but the role of LRIG1 in non-epithelial intestinal cells has not been identified. We sought to determine the ontogeny of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, and whether LRIG1 has a role in their development.

METHODS

LRIG1-null mice (homozygous Lrig1-CreERT2) and wild-type mice were analyzed by immunofluorescence and transit assays. Transit was evaluated by passage of orally administered rhodamine B-conjugated dextran. Lrig1-CreERT2 mice or mice with CreERT2 under control of an inducible smooth muscle promoter (Myh11-CreERT2) were crossed with Rosa26-LSL-YFP mice for lineage tracing analysis.

RESULTS

In immunofluorescence assays, ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP were found to express LRIG1. Based on lineage tracing, ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP each arose from LRIG1-positive smooth muscle progenitors. In LRIG1-null mice, there was loss of staining for c-Kit in DMP and SMP regions, as well as for 2 additional ICC markers (ANO1 and NK1R). LRIG1-null mice had significant delays in small intestinal transit, compared with control mice.

CONCLUSIONS

LRIG1 regulates the post-natal development of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP from smooth muscle progenitors in mice. Slowed small intestinal transit observed in LRIG1-null mice may be due, at least in part, to loss of the ICC-DMP population.

Keywords: intestinal transit, development, ICC-DMP, ICC-SMP

Introduction

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) form networks within the musculature of the gastrointestinal tract and serve as pacemakers and transducers of neural inputs that control contraction of smooth muscle to regulate gut motility1–4. ICC dysfunction may contribute to the pathogenesis of a wide spectrum of intestinal disorders, including. achalasia5, diabetic gastroparesis6 and enteropathy7, Crohn's disease8 and slow transit constipation9,10. ICC are divided into several subpopulations according to their location. Myenteric ICC (ICC-MY) are found in the myenteric plexus of phasic muscle throughout the gut, while ICC associated with the deep muscular plexus (ICC-DMP) are located within the mucosal side of the circular muscle of the small intestine and ICC associated with the colonic submucosal plexus (ICC-SMP) are luminal to the circular muscle layer 11,12. Gastric, small intestinal and colonic ICC-MY and colonic ICC-SMP are electrical pacemaker cells1,13,14. Small intestinal ICC-DMP are not thought to act as pacemakers13, but rather to mediate excitatory and inhibitory motor neural inputs3,15,16. The murine colon also contains intramuscular and subserosal ICC populations (ICC-IM and ICC-SS, respectively)12.

c-Kit, a receptor tyrosine kinase that serves as the receptor for stem cell factor, is important for the proper development and function of ICCs13,14,17. Blockade of c-Kit activity with a neutralizing antibody in newborn mice results in loss of all ICC subsets, including ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP1,18. In contrast, ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP are present in c-Kit mutant mice with decreased c-Kit activity, such as W/Wv or Wsh/Wsh mice, whereas ICC-MY are grossly underdeveloped in the small intestine of these mice13,14,19. These findings suggest ICC-DMP and ICC-MY in the small intestine may be differentially regulated and differentially dependent on c-Kit activity. Indeed, ICC-MY and ICC-IM development is regulated by the ETS family transcription factor, ETV1, but ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP development is not20. However, factor(s) that selectively regulate the development and maintenance of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP are unknown.

In the mouse small intestine, both ICC-MY and intestinal smooth muscle cells emerge from common c-Kit-positive progenitors during mouse embryogenesis (E12.5 to E18)17,21. However, the origin of c-Kit-expressing ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP is uncertain; the former is present sparsely at birth in the mouse jejunum16,17, and the latter does not appear until postnatal day five in the proximal colon22. Both populations expand in number after birth to form functional cellular networks16,22. Based upon ultrastructual observations, it has been proposed that ICC-DMP emerges from undifferentiated cells termed ‘ICC-blasts’ that populate the DMP region1,18,23; however, the origin of ‘ICC-blasts’ is unknown.

Recently, we identified that Leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domains protein 1 (Lrig1), a pan-ErbB negative regulator24,25, marks intestinal epithelial stem cells26. Lrig1 is also expressed in epidermal27 and corneal stem cells28. The above are tissues that turnover continuously. However, the distribution and role of Lrig1 in tissues where cells turnover or proliferate less frequently, such as muscle, are unclear.

Herein, we provide evidence that ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP arise postnatally from intestinal smooth muscle cells in murine small intestine and colon, respectively. We also show that ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP express Lrig1 and that Lrig1 regulates the differentiation of smooth muscle cells into ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP. In the absence of Lrig1, ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP are largely lost. Moreover, Lrig1-null mice exhibit markedly delayed small intestinal motility. Taken together, these studies identify the ontogeny of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP and assign a role for Lrig1 in their development.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The generation of Lrig1<tm1.(cre/ERT)Rjc> (Lrig1-CreERT2/+) mice has been reported previously26. Lrig1-Apple/+ reporter mice, in which exon 1 of the Lrig1 gene was replaced by the apple fluorescent protein coding sequence, was generated in a similar strategy as Lrig1-CreERT2/+ mice29. Myh11-CreERT2 mice30 and Rosa26 (R26)-YFP mice31 were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). For developmental lineage tracing, Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26-YFP/+ mice or Myh11-CreERT2/+;R26-YFP/+ mice were given a single, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)(33 mg/kg) at postnatal day one and analyzed at the time points indicated. Eight-week-old adult mice were used for experiments presented in Figures 1, 2 and 6, and Supplementary Figure 1,2 and 5; in other experiments, ages of mice are described in figures and/or figure legends. All mouse experiments were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Figure 1. ICC-DMP express Lrig1.

(A) Immunofluorescent images of Lrig1-Apple/+ mouse small intestinal tissue sections stained for c-Kit (green). Endogenous apple fluorescence (RFP) is shown in red. ICC-DMP are enclosed with dotted boxes and enlarged in insets below. Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer bound by the submucosa (upper side) and the myenteric region (lower side). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(B-D) Immunofluorescent images of WT small intestinal tissue sections stained for Lrig1 and c-Kit (B), or alternative ICC-markers Ano1 (C) and Nk1r (D). Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer bound by the DMP region (upper side) and the myenteric region (lower side). Yellow arrowheads indicate cells that have positive staining for both Lrig1 and c-Kit. White arrowheads indicate Lrig1(+)/c-Kit(−) cell at the DMP region (B). White arrows indicate ICC-MY with weak Lrig1 staining (B-C). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Figure 2. Lrig1 is expressed in ICC-DMP, but not in Pdgfra-positive ICC-like fibroblasts.

(A) Confocal images of the small intestinal DMP region. WT small intestinal whole mounts were stained for c-Kit (green) and Lrig1 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(B) c-Kit expression status in Lrig1-positive cells in the DMP region is shown as a percentage. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 3 mice.

(C) Immunofluorescent images of WT small intestine. Tissues were stained for Pdgfra (green) and Lrig1 (red). Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D) Confocal images of the DMP region of WT small intestine. WT small intestinal whole mounts were stained for Pdgfr (green) and Lrig1 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 20 μm.

(E) Immunofluorescent images of human duodenum. Tissues were stained for c-KIT (green) and LRIG1 (red). White dotted line indicates circular muscular layer. Yellow arrowheads indicate ICC-MY. Confocal images of boxed DMP region is shown below enclosed with yellow arrows indicating cells stained for both LRIG1 and c-KIT, and white arrowheads with cells stained only for LRIG1. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. CM; circular muscular layer, LM; longitudinal muscular layer. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Figure 6. Lrig1 is required for development of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP.

(A-C) Immunofluorescent images of WT (Ai,Bi,Ci) and Lrig1 null (Aii,Bii,Cii) small intestinal tissue sections stained for Lrig1 and ICC markers. (A) c-Kit; green, Lrig1; red, (B) Lrig1; green, Ano1; red, (C) c-Kit; green, Nk1r; red. Dotted line indicates the submucosal side of the circular muscular layer where ICC-DMP should reside, but are lost in Lrig1 null mice. Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D) Quantification of cells in DMP (left panel) and MY (right panel) regions of the small intestine. Number of nuclei from c-Kit-positive cells per field (0.1 mm2) is shown. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 3 mice.

(E) Diagram of the postnatal development of ICC-DMP. (Left panel) At birth in the small intestine, circular smooth muscle cells express Lrig1 (red) and c-Kit expression (green) are observed in ICC-MY (upper left). During postnatal development, Lrig1 expression decreases in the outer side of the circular muscular layer, and cells at the most inner layer of Lrig1-positive circular smooth muscle cells show increased c-Kit expression (red-green stripe, upper middle). In the adult small intestine, sustained high Lrig1 expression is seen in ICC-DMP (red-green stripe) and Lrig1-positive ICC-like cells (red, upper right). When Lrig1 is lost, ICC-DMP are absent in the small intestine, while ICC-MY are preserved (lower). (Right panel) Localization of ICC-DMP and ICC-MY in the small intestine is shown. Ep; epithelium, Sm; submucosa, CM; circular muscular layer, LM; longitudinal muscular layer.

Human Samples

Three freshly resected normal human duodenal specimens were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (Vanderbilt University Medical Center). De-identified tissues were collected with Institutional Review Board approval. The tissues supplied are not resected specifically for research, but are surgical waste tissues, which are left over after the pathologist had taken tissues for diagnosis. Tissues were handled according to institutional ethical guidelines.

Tissue Processing and Immunofluorescence

For frozen sections, intestinal tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4°C, followed by consecutive 15% and 30% sucrose immersion before freezing in Optimal Cutting Temperature (O.C.T.) compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Cryosections were mounted onto glass slides and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes in PBS containing 0.1% Triton 100-X (PBST) and 2.5% normal donkey serum to reduce non-specific immunostaining. Alternatively for human samples, Protein Block Serum-Free (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) was used to reduce non-specific immunostaining. The sections were incubated with primary antibody at room temperature for one hour. Sections were then washed three times in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections were counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclear detection. Primary and secondary antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table (Antibody list). Micrographic images were obtained using an Olympus IX-71 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) for mouse tissue, and Axio Imager.M2 (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) for human tissue (Figure 2E upper row). Images presented are representatives of 3 mouse or human samples.

Whole Mount Staining

Whole intestinal tissues were fixed with ice-cold acetone and kept at −80°C less than one week until rehydration. Alternatively, for lineage tracing experiments, tissues were fixed with 4% PFA on ice for 15 minutes in order to preserve YFP immunoreactivity. After washing in PBS, the muscular layer was detached from the mucosa. After one hour of blocking in 2.5% donkey serum in PBST, samples were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Samples were then washed with PBS and labeled with secondary antibodies at room temperature for two hours. Tissues were counterstained with DAPI and mounted on glass slides. Confocal images were obtained using an Olympus FluoView-1000. Images presented are representatives of 3 mouse samples.

Quantification of ICCs and Lrig1-expressing Cells

The jejunum and colon of eight-week-old wild-type (WT) mice were used for quantification analyses, which are presented in Figure 2B and 6D. For quantification of lineage-traced cells, Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26-YFP or Myh11-CreERT2;R26-YFP mice were given a single tamoxifen injection, as described above. Mice then were sacrificed 3 weeks after tamoxifen injection, and jejunum, ileum and colon were used for quantification (Supplementary Figure 4C and Figure 5E). The small intestine was divided into three equal length segments rostral-caudally, and the most proximal portion of the second segment was designated jejunum, and the most distal portion of the third segment was designated ileum. The colon was divided into three equal length segments rostral-caudal to obtain proximal, middle and distal segments. For image quantification, confocal z-stack images were obtained with no more than a two-micron step between slices. Three mice were used for each genotype, and images were taken from three random fields per whole mount preparation (40× magnification (0.1 mm2) for Figure 2B and 6D, and 60× magnification (0.045mm2) for Supplementary Figure 4C and Figure 5E. The number of positive cells with each label was counted with DAPI nuclear stain using ImageJ software (Cell Counter plug-in, National Institutes of Health, USA).

Gastric Emptying and Intestinal Transit Assay

Gastric emptying and small intestinal transit were measured by evaluating the intestinal location of Rhodamine B-conjugated dextran (D1841, Molecular Probes) as described elsewhere32 with modification. Six-week-old mice were given 2.5mg/ml of Rhodamine B-conjugated dextran in 5% methylcellulose (M7027, Sigma) via gavage. Ten minutes after administration for the gastric emptying assay and 60 minutes after administration for the small intestinal transit assay, the entire small bowel (unflushed) was divided into 10 equal segments and placed into tubes with 4ml of PBS. The stomach was prepared similarly. Tissues were homogenized and were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for ten minutes to separate out a pellet and supernatant. The fluorescence in each aliquot of the cleared supernatant was read by a Synergy4 plate reader (excitation 540 nm/emission 625 nm, BioTek). Gastric emptying was calculated as the ratio of the total fluorescent intensity in small intestine divided by total fluorescent intensity in stomach and small intestine. For small intestinal transit, fluorescent intensity for each small intestinal segment (I1 to I10, numbered from oral side) was used to calculate the geometric center of delivered dextran by the formula below32.

Statistical Analysis

For Figure 7A, C and D, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis AVNOVA was used to test for an overall difference among the three treatment groups at 5% significance level. Then all possible pair-wise tests were conducted using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and reported only when the overall test was significant, and P <.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Data is displayed as mean values ± SD.

Figure 7. Lrig1 null mice exhibit delayed small intestinal transit.

(A) Geometric center of the distribution of delivered Rhodamine B-dextran is plotted for each mouse examined. Black bar indicates mean value of each genotype group.

(B) Representative data of the distribution of delivered Rhodamine B-dextran for each mouse examined. Data from mice with a geometric center value closest to the mean value of each group is shown. The Y-axis is presented as the percentage of total Rhodamine B intensity.

(C) Gastric emptying assay. Ratio of Rhodamine B excluded from the stomach is plotted for each mouse examined. Black bar indicates mean value of each genotype group.

(D) Length of small intestine of mice used for transit assay. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 10 to 12 mice per group.

Additional experimental procedures are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Results

Lrig1 is expressed by ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP

We previously showed that Lrig1, a pan-ErbB negative regulator25, marks intestinal epithelial stem cells26. To characterize Lrig1 transcriptional activity in vivo, we recently generated Lrig1-Apple/+ mice into which a red fluorescent protein (RFP) reporter was inserted into the translational start site of the endogenous mouse Lrig1 locus29. As expected, RFP fluorescence was observed at the crypt base in the small intestine (Figure 1A) and colon (Supplementary Figure 1A). Unexpectedly, we observed fluorescence beneath the epithelium in both the small intestine (Figure 1A) and colon (Supplementary Figure 1A). To examine the specificity of Lrig1 expression in this region, we performed immunofluorescence using a commercially available Lrig1 antibody, and found an identical staining pattern to that of RFP, confirming that Lrig1 protein was also present in these subepithelial cells (Supplementary Figure 1B). Lrig1 immunoreactivity was not observed in Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 (hereafter Lrig1 null) mice, confirming the specificity of the antibody (Supplementary Figure 1C, and described below). Since Lrig1 is also expressed in glial cells in mouse brain33, we first examined whether these Lrig1-positive cells were components of the enteric nervous system. We co-stained with a glial cell marker, S100, and PGP9.5, a neuronal cell marker; the subepithelial Lrig1-positive cells did not express either marker (Supplementary Figure 1D-G), suggesting that these Lrig1-positive cells are likely non-neuronal.

We next considered whether these cells might be ICCs. To investigate this possibility, we co-stained with the ICC marker, c-Kit. As expected, c-Kit immunoreactivity was detected in all ICC populations: ICC-MY and ICC-DMP in the small intestine, and ICC-MY, ICC-IM, ICC-SS and ICC-SMP in the colon (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure 1A). Lrig1 was co-expressed with c-Kit in ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP in the small intestine and colon, respectively (Figure 1A-B and Supplementary Figures 1A,H). In contrast, there was no Lrig1 staining in the colonic ICC-MY population (Supplementary Figure 1H) and only weak Lrig1 immunoreactivity in the small intestinal ICC-MY population (Figure 1B). We compared Lrig1 immunoreactivity with two other ICC markers: anoctamin-1 (Ano1), which is expressed in all ICC populations34, and the neurokinin 1 receptor (Nk1r), which labels ICC-DMP3,35, but not other ICC subsets. Lrig1 was co-expressed with these markers in ICC-DMP (Figure 1C-D) and ICC-SMP (Supplementary Figure 1I). As expected, Ano1 was expressed by ICC-MY, whereas Lrig1 staining was absent in this population. Thus, Lrig1 is expressed in ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP in both small intestine and colon, but not in ICC-MY in the colon and only weakly in ICC-MY in the small intestine. Interestingly, there was no ICC subpopulation in the stomach that exhibited Lrig1 immunoreactivity comparable to duodenal ICC-DMP (Supplementary Figure 1J-K). ICC-MY in the stomach had weak Lrig1 staining similar to what was seen in ICC-MY in the duodenum, and in contrast to absent Lrig1 immunoreactivity in colonic ICC-MY.

In cross-sections of the small intestine, we noted that Lrig1 stained a number of cells in the DMP region of the small intestine that were c-Kit negative (Figure 1B). To evaluate if this reflected a difference in intracellular distribution of Lrig1 and c-Kit, or the potential existence of two different populations, we performed whole mount staining of the DMP region (Figure 2A). All c-Kit-positive ICC-DMP expressed Lrig1 (Supplementary Figure 2A-B), indicating Lrig1 is uniformly expressed in ICC-DMP. However, while 60% of Lrig1-positive cells also expressed c-Kit, 40% were c-Kit-negative (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 2B). We observed similar results when we quantified Lrig1- and Ano1-expressing populations, as well as Lrig1- and Nk1r-expressing populations (Supplementary Figure 2C-D). In the colonic SMP region, such Lrig1(+)/c-Kit(−) cells were also observed, but less frequently (Supplementary Figure 2E). Similar to the small intestine, all ICC-SMP c-Kit-positive cells co-expressed Lrig1 (data not shown). In the DMP region of the small intestine, c-Kit-negative/Pdgfra-positive fibroblast-like cells with oval cell bodies and long processes run parallel with ICC-DMP and smooth muscle cells, while Pdgfra-positive fibroblast-like cells are absent in the colonic SMP region36,37. We examined whether Lrig1(+)/c-Kit(−) cells were these c-Kit-negative fibroblast-like cells. We observed that Lrig1-positive cells and Pdgfra-expressing cells are adjacent, but non-overlapping (Figure 2C-D). Overall, these results indicate that Lrig1 is expressed in ICC-DMP in the small intestine and ICC-SMP in the colon, and is also expressed in an unknown c-Kit-negative population, which is morphologically similar to its c-Kit-positive counterpart. Of note, human duodenum also exhibited both LRIG1-positive/c-KIT-positive and LRIG1-positive/c-KIT-negative cells in the DMP region of the circular muscular layer, while LRIG1 immunoreactivity was absent in ICC-MY (Figure 2E), suggesting the potential relevance of our murine findings to humans.

Lrig1 expression precedes emergence of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP during postnatal development

We next investigated the timing of Lrig1 expression beneath the epithelium during postnatal development. In the small intestine, ICC-DMP are rarely observed at postnatal day 0 (P0), but are detected shortly after birth and continue to develop until at least P1016. In the colon, ICC-SMP are absent at birth; they emerge around P5 in the proximal colon, and shortly later in the distal colon22. We examined a time-course of the developing tunica muscularis in the ileum and proximal colon and observed that Lrig1 is expressed broadly in the smooth muscular layer from P0 to P5 (Figure 3Ai-iii and Supplementary Figure 3Ai-iii). Lrig1 exhibited a clear vertical gradient with strong expression at the mucosal side of the circular muscular layer and weaker expression at the outer border (Figure 3Ai-iii, Supplementary Figure S3Ai-iii). In the small intestine, some cells at the innermost surface of the circular muscular layer were negative for Lrig1 at P0 (Supplementary Figure 3D). At later time points, Lrig1-negative circular smooth muscle cells formed an thin inner layer (Supplementary Figure 3E-F); this layer was separated from the outer part of the circular muscular layer by ICC-DMP23. Strong Lrig1 expression in the circular muscular layer of the ileum gradually became dimmer, and restricted to the mucosal side three weeks after birth; some Lrig1-positive cells also expressed the ICC-DMP marker c-Kit at this time (Figure 3A-B). We observed similar results in the proximal colon from P0 to three weeks (Supplementary Figure 3A-B). We also examined c-Kit immunoreactivity in the emerging ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP populations over this time-course and observed a time-dependent increase in staining intensity (Figure 3A,C and Supplementary Figure 3A,C). Together, these data indicate that Lrig1 expression in the circular smooth muscle is widespread at P0, but, over the first three weeks of life, it becomes restricted to the region that contains c-Kit-expressing cells.

Figure 3. Changes in Lrig1 and c-Kit expression during postnatal development of the muscular layer.

(A) Immunofluorescent images of WT small intestinal tissue sections stained for Lrig1 (red) and c-Kit (green) during postnatal development from postnatal day 0 (i) to 3 weeks old (vi). Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(B,C) Relative immunoreactivity of Lrig1 (B) and c-Kit (C) during postnatal development of the small intestinal muscular layer. Data are shown as relative intensity of Lrig1 in cells adjacent to the MY region compared to cells in the DMP region (B), or relative intensity of c-Kit in DMP region compared to MY region (C). Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 3 mice.

(D,E) Confocal images of colon during postnatal development. ICC-SMP positive for both c-Kit (green) and the muscular marker SMA (D, red) at P5 and triple positive for c-Kit (green), calponin (E, red) and Lrig1 (E, white) at P7 were enclosed with dotted boxes and enlarged in insets below. Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm.

These observations imply a developmental link between smooth muscle cells and both ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP. To further investigate that possible link, we reasoned that smooth muscle markers should decrease within the inner region of the circular muscular layer as c-Kit-positive ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP emerged. In fact, c-Kit expression in ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP gradually increased from P0 to P10 (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 3A), leading us to examine the transition from smooth muscle cells to ICCs during this time frame. At P5-7, some colonic ICC-SMP cells remained positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA) (P5) or calponin (P7), both of which are markers for smooth muscle cells (Figure 3D-E), suggesting that these cells may be in an intermediate state between smooth muscle cells and c-Kit-positive ICC-SMP cells. In addition, we observed co-expression of c-Kit, calponin and Lrig1 at P7 (Figure 3E). Collectively, these results suggest that a subset of Lrig1-expressing smooth muscle progenitors give rise to c-Kit-expressing ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP.

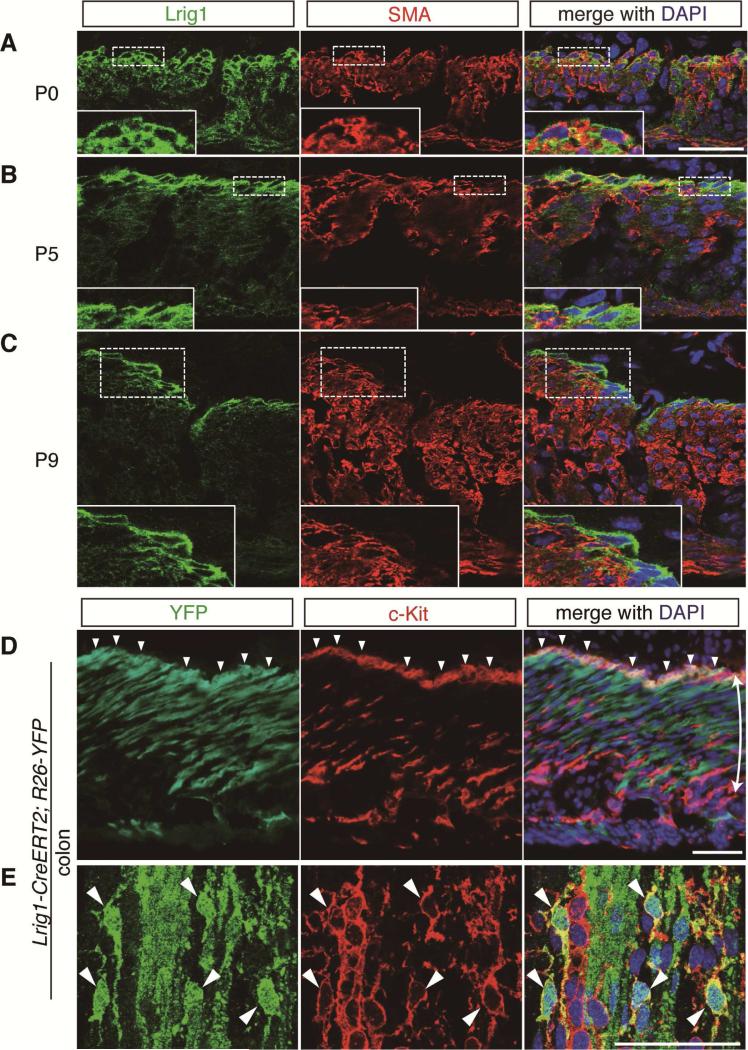

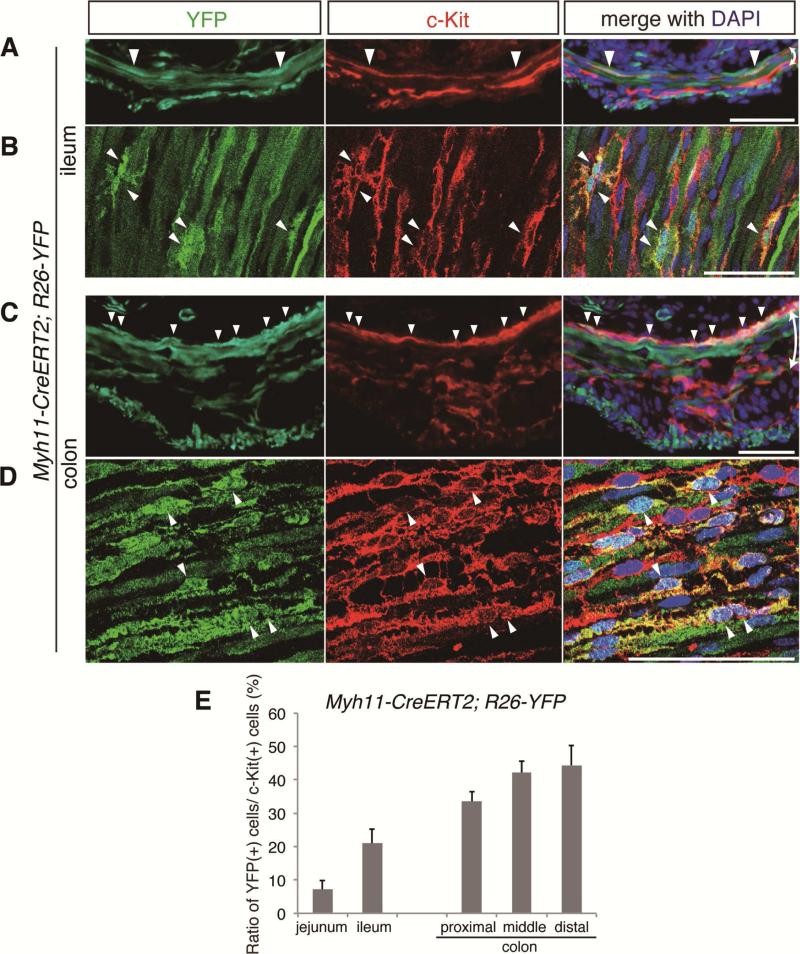

Lrig1-positive smooth muscle cells give rise to ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP

To further substantiate the claim that Lrig1-expressing smooth muscle cells are the origin of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, we examined the dynamics of Lrig1 and SMA expression during early development. We observed that SMA expression was gradually lost from Lrig1-expressing cells at the surface of developing circular muscle of the colon from P0 to P9 (Figure 4A-C). To ask directly if Lrig1-expressing cells were the cell-of-origin for ICC-SMP, we used Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26-YFP mice26 to perform lineage tracing. We administered a single injection of tamoxifen (33 mg/kg, i.p.) at P1 before the emergence of ICC-SMP in the colon22 (Supplementary Figure 3Ai-ii) and when Lrig1 is expressed in smooth muscle cells beneath the epithelium (Figure 4A). When tissues were evaluated after development of ICC-SMP, YFP-positive cells were observed in the colonic c-Kit-expressing ICC-SMP population (Figure 4D-E), as in smooth muscle cells (Figure 4D). We quantified YFP positivity within ICC-SMP by confocal microscopic analysis and found that ~50% of ICC-SMP were lineage traced throughout the colon (Supplementary Figure 4C). In the small intestine, we also observed YFP positivity in ICC-DMP (Supplementary Figure 4A-E). To directly confirm the smooth muscular origin of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, we also performed lineage tracing experiments using inducible, smooth muscle-specific Cre-recombinase (smooth muscle myosin heavy chain 11, Myh11-CreERT2)30 crossed to R26-YFP mice31. Tamoxifen was administered to Myh11-CreERT2/+;R26-YFP/+ mice at P1 and intestinal tissues were harvested and processed at later time points. We observed increasing ratios of lineage-traced, YFP(+)/c-Kit(+), cells up to ~45% towards the distal part of the intestine (Figure 5A-E), indicating ICC-SMP and ICC-DMP are the progeny of Myh11-expressing smooth muscle cells. This gradual increase in lineage-traced cells towards the distal intestine may correspond to a rostral-caudal gradient development of ICC-DMP16 and ICC-SMP22, which may be related to inactivation of Myh11 transcription earlier in the more proximal parts of the intestine. These lineage tracing results provide strong evidence that ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP arise from smooth muscle progenitors postnatally.

Figure 4. ICC-SMP arise from Lrig1-positive cells during postnatal development.

(A-C) Confocal images of the colonic tunica muscularis during postnatal development at indicated postnatal ages. Lrig1-positive cells (green) at the surface of the inner circular muscular layer (labeled by SMA, red) are enclosed in dotted boxes and enlarged in insets below. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 15 μm.

(D-E) Immunofluorescent (D) and confocal (E) images of the colon of Lrig1-CreERT2/+;R26-LSL-YFP/+ mice. Tamoxifen was given at postnatal day 1 (P1) and tissues were collected at P9 (D) or P22 (E). Tissues were stained for YFP with an anti-EGFP antibody (green) and c-Kit (red). For confocal imaging, single optical slices of SMP region were acquired (E). Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Arrowheads indicate ICC-SMP positive for YFP. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Figure 5. ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP arise postnatally from smooth muscle progenitors.

(A-D) Immunofluorescent (A, C) and confocal (B, D) images of small intestine (A-B) and colon (C-D) of Myh11-CreERT2/+;R26-LSL-YFP/+ mice. Tamoxifen was given at postnatal day 1 (P1) and tissues were collected at P10 (A, C) or P22 (B, D). Tissues were stained for YFP with an anti-EGFP antibody (green) and c-Kit (red). Double-headed arrow indicates circular muscular layer. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Arrowheads indicate ICC-DMP (A-B) or ICC-SMP (C-D) cells that are positive for YFP. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(E) Quantification of lineage-traced cells for confocal microscopic analysis. YFP expression status among c-Kit-positive cells in DMP and SMP region is shown as percentages. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 3 mice.

Lrig1 is required for development of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP

We next examined whether the expression of Lrig1 influenced the development of ICC. We examined wild-type (WT) and Lrig1 null mice and observed near complete loss of c-Kit immunoreactivity in the DMP region in the small intestine and SMP region in the colon (Figure 6A, Supplementary Figure 5A). In Lrig1 null mice, additional markers for ICCs, Ano1 and Nk1r, were also largely absent, compared to WT mice (Figure 6B-C and Supplementary Figure 5B). Of note, SMA staining in the small intestine revealed that the DMP region does not develop in Lrig1 null mice (Supplementary Figure 6A-B), compared to WT mice of the same age. To quantify these findings, we counted total c-Kit-positive cells per visual field in the ICC-DMP region in WT, Lrig1 heterozygous (Lrig1-CreERT2/+, hereafter Lrig1 het) and Lrig1 null mice. Although Lrig1 het mice have only one wild-type Lrig1 allele, they have a similar number of Lrig1-positive and c-Kit-positive cells compared to WT mice (Figure 6D, left panel). We observed significantly fewer total c-Kit-positive cells in Lrig1 null mice, compared to the other two cohorts (Figure 6D, left panel). Together, our observations suggest that the ICC-DMP population is largely lost in Lrig1 null mice, and there appears to be no haploinsufficient effect.

In addition to Lrig1 expression in ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, we also observed weak Lrig1 immunoreactivity in small intestinal ICC-MY (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 5C), but not in colonic ICC-MY in WT mice (Supplementary Figure 1H). However, ICC-MY were not altered in cell number or in gross morphology (Figure 6D, right panel, and Supplementary Figure 5D) in Lrig1 null mice. On the other hand, in the stomach that lacks a Lrig1-positive ICC population at the inner side of the circular muscle, no obvious changes in ICC populations were observed in Lrig1 null mice (data not shown). We also evaluated the postnatal development of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP in Lrig1 null mice. Immunoflurorescent analyses using Lrig1 null tissue showed no emergence of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, confirming that lack of Lrig1 affects development of these cells, and that our results cannot be explained by regression of these cells after their emergence (Supplementary Figure 7 and data not shown). These results indicate that Lrig1 is not only a marker for ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, but also is essential for development of these ICC subsets (Figure 6E).

Lrig1 null mice exhibit delayed small intestinal transit

To evaluate the functional consequence of ICC-DMP loss in Lrig1 null mice, we next assessed small intestinal transit, a process that is regulated by numerous factors38,39, including ICC40,41. We administered Rhodamine B-conjugated dextran via gavage and quantified segmental passage of the dextran within the small intestine. WT and Lrig1 het mice displayed a similar distribution of dextran throughout the small intestine, while Lrig1 null mice exhibited significantly slower transit (Figure 7A-B). To exclude the contribution of change in gastric emptying, an additional cohort of mice was given Rhodamine B-conjugated dextran, and the amount of dye that left the stomach was evaluated. Of note, the ratio of the dextran retained in the stomach did not differ among genotypes (Figure 7C). In addition, the length of the small intestine was not significantly different in Lrig1 null mice compared to WT and Lrig1 het mice (Figure 7D), indicating that decreased segmental passage in Lrig1 null mice is cannot be explained by longer segments than in WT mice. Thus, Lrig1 null mice exhibit significantly delayed small intestinal transit, suggesting a possible functional consequence of the loss of this ICC population.

Discussion

In the present study, we show that ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP arise postnatally from circular smooth muscle cells, and that the pan-ErbB inhibitor, Lrig1, is a novel marker of these ICC subsets (Figure 6E). We also demonstrate that Lrig1 null mice exhibit delayed small intestinal transit. These findings identify the ontogeny of this subset of ICCs and implicate a role for Lrig1 in their development.

There appears to be an intimate link between ICC-MY and smooth muscle cells. For example, ICC-MY and smooth muscle cells arise from a common c-Kit-positive progenitor in the mouse small intestine during embryogenesis21. In addition, neutralizing antibody blockade of c-Kit activity in neonatal mice results in acquisition of ultrastructural features of smooth muscle cells by ICC-MY16. However, a direct link between smooth muscle cells and ICC-DMP or ICC-SMP has not been previously shown. We now show by lineage tracing that both ICC-DMP in the small intestine and ICC-SMP in the colon arise postnatally from inner circular smooth muscle cells. Lrig1 expression in this region precedes c-Kit expression and the emergence of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP. In early postnatal life, Lrig1 is expressed broadly in smooth muscle cells, but becomes more restricted to ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP over time. In addition, Lrig1 loss results in loss of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP. Based on our observations, we propose a model in which Lrig1 promotes postnatal differentiation of smooth muscle cells to ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP. We suspect the non-lineage traced cells in the ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP populations are due to inefficient recombination and/or a rostral-caudal developmental gradient. However, we cannot exclude that ICC-SMP and ICC-DMP are heterogeneous populations with different origins. We hypothesize that, in the absence of Lrig1, smooth muscle cells are unable to differentiate into ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, similar to the observation that mice treated postnatally with a c-Kit neutralizing antibody fail to exhibit differentiation of putative precursor cells18.

Loss of ICC-DMP results in delayed small intestinal transit and it is tempting to speculate that loss of ICC-DMP is directly responsible for this delay. However, it is important to consider other possibilities that could affect gut motility in Lrig1 null mice, such as the potential contribution of Lrig1-positive/c-Kit-negative ICC-like cells. We found that ~40% of Lrig1-positive cells are c-Kit-negative in the small intestine, although they exhibit similar morphology to ICC-DMP. These Lrig1-positive/cKit-negative ICC-like cells, which have not been reported previously, form a network with ICC-DMP and are distinct from Pdgfra-positive fibroblast-like cells36,37. In the colon, a rare population of Lrig1-positive ICC-like cells was also observed in the SMP region, where Pdgfra-positive fibroblast-like cells do not reside36. It will be important to determine whether these Lrig1-positive ICC-like cells have a functional role in smooth muscle, or if they represent an intermediate state preceding mature ICC-DMP or ICC-SMP. It is also possible that intestinal smooth muscle cells were affected due to loss of Lrig1, as Lrig1 is broadly expressed in smooth muscle of newborn mice. Ultimately, more detailed physiological studies will be required to fully understand which cell (or cells) are responsible for decreased gut motility in Lrig1 null mice.

Our studies make use of Lrig1 deficiency in Lrig1-CreERT2/CreERT2 mice, which express Cre recombinase in place of the Lrig1 protein. Wong et al. reported in 2012 the intestinal phenotype of Lrig1 germline knockout mice, which were generated using a different strategy and in a different genetic background. Of interest, this group observed a perinatal lethality in Lrig1 null mice related to marked abdominal distension42. They proposed this phenotype was due to intestinal epithelial hyperproliferation, resulting from loss of this ErbB negative regulator; however, the hyperproliferation was modest. We submit that an alternate explanation for the abdominal distension in these mice may be due to effects on ICC populations, in particular, ICC-DMP.

We now report a genetically engineered mouse model in which there is loss of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP with preservation of ICC-MY. This model will allow investigators to conduct experiments that will provide greater mechanistic and physiological understanding of the nature of ICC-DMP and ICC-SMP, and how these ICC subsets may influence gastrointestinal function in health and disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by: National Cancer Institute R01CA151566, P50CA095103 Gastrointestinal Specialized Programs of Research Excellence, and a VA Research Merit Grant to R.J.C.; T32CA119925 to A.E.P.; March of Dimes FY12-450 and US National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK60047 to E.M.S2.; NIH F30 DK096831 to M.A.M.; and the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research Grant to J.K. Core services performed through Vanderbilt University Medical Center's Digestive Disease Research Center were supported by NIH Grant P30DK058404 Core Scholarship.

Abbreviations

- DMP

deep muscle plexus

- ICC

Interstitial Cells of Cajal

- MY

myenteric region

- SMP

submucosal plexus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Writing Assistance

We thank Emily J. Poulin for editorial assistance.

Author Contributions

J.K., A.E.P., Y.W., J.L.F. and R.J.C. designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.A.M. and E.M.S2. provided technical assistance, conceptual advice, and contributed reagents. J.K. and R.J.C. assembled the manuscript.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authors. Chi P, Chen Y, Wong VWY, Stange DE, Page ME

References

- 1.Torihashi S, Ward SM, Nishikawa S-I, et al. c-kit-Dependent development of interstitial cells and electrical activity in the murine gastrointestinal tract. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:97–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00304515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson L, Robinson TL, Lee JCF, et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal generate a rhythmic pacemaker current. Nat. Med. 1998;4:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iino S, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of Cajal are functionally innervated by excitatory motor neurones in the murine intestine. J. Physiol. 2004;556:521–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein S, Seidler B, Kettenberger A, et al. Interstitial cells of Cajal integrate excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission with intestinal slow-wave activity. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1630. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gockel I, Bohl JR, Eckardt VF, et al. Reduction of Interstitial Cells of Cajal (ICC) Associated With Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase (n-NOS) in Patients With Achalasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008;103:856–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horváth VJ, Vittal H, Lörincz A, et al. Reduced Stem Cell Factor Links Smooth Myopathy and Loss of Interstitial Cells of Cajal in Murine Diabetic Gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:759–770. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forrest A, Huizinga JD, Wang X-Y, et al. Increase in stretch-induced rhythmic motor activity in the diabetic rat colon is associated with loss of ICC of the submuscular plexus. Am. J. Physiol. - Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G315–G326. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00196.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porcher C, Baldo M, Henry M, et al. Deficiency of interstitial cells of Cajal in the small intestine of patients with Crohn's disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He C-L, Burgart L, Wang L, et al. Decreased interstitial cell of Cajal volume in patients with slow-transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashyap P, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Pozo MJ, et al. Immunoreactivity for Ano1 detects depletion of Kit-positive interstitial cells of Cajal in patients with slow transit constipation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011;23:760–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iino S, Horiguchi K. Interstitial Cells of Cajal Are Involved in Neurotransmission in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2006;39:145–153. doi: 10.1267/ahc.06023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Sajee D, Huizinga JD. Interstitial Cells of Cajal. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2012;12:411–421. doi: 10.12816/0003165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, et al. Mutation of the proto-oncogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. J. Physiol. 1994;480:91–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Klüppel M, et al. W/kit gene required for interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity. Nature. 1995;373:347–349. doi: 10.1038/373347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X-Y, Vannucchi M-G, Nieuwmeyer F, et al. Changes in Interstitial Cells of Cajal at the Deep Muscular Plexus Are Associated with Loss of Distention-Induced Burst-Type Muscle Activity in Mice Infected by Trichinella spiralis. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;167:437–453. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62988-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward SM, McLaren GJ, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of Cajal in the deep muscular plexus mediate enteric motor neurotransmission in the mouse small intestine. J. Physiol. 2006;573:147–159. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torihashi S, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Development of c-Kit-positive cells and the onset of electrical rhythmicity in murine small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:144–155. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torihashi S, Nishi K, Tokutomi Y, et al. Blockade of kit signaling induces transdifferentiation of interstitial cells of Cajal to a smooth muscle phenotype. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iino S, Horiguchi K, Nojyo Y. Wsh/Wsh c-Kit mutant mice possess interstitial cells of Cajal in the deep muscular plexus layer of the small intestine. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;459:123–126. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi P, Chen Y, Zhang L, et al. ETV1 is a lineage-specific survival factor in GIST and cooperates with KIT in oncogenesis. Nature. 2010;467:849–853. doi: 10.1038/nature09409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klüppel M, Huizinga JD, Malysz J, et al. Developmental origin and kit-dependent development of the interstitial cells of cajal in the mammalian small intestine. Dev. Dyn. 1998;211:60–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199801)211:1<60::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han J, Shen W-H, Jiang Y-Z, et al. Distribution, development and proliferation of interstitial cells of Cajal in murine colon: an immunohistochemical study from neonatal to adult life. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2010;133:163–175. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellegrini MSF. Morphogenesis of the special circular muscle layer and of the interstitial cells of Cajal related to the plexus muscularis profundus of mouse intestinal muscle coat. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 1984;169:151–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00303144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gur G, Rubin C, Katz M, et al. LRIG1 restricts growth factor signaling by enhancing receptor ubiquitylation and degradation. EMBO J. 2004;23:3270–3281. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laederich MB, Funes-Duran M, Yen L, et al. The Leucine-rich Repeat Protein LRIG1 Is a Negative Regulator of ErbB Family Receptor Tyrosine Kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47050–47056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell AE, Wang Y, Li Y, et al. The Pan-ErbB Negative Regulator Lrig1 Is an Intestinal Stem Cell Marker that Functions as a Tumor Suppressor. Cell. 2012;149:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen KB, Collins CA, Nascimento E, et al. Lrig1 Expression Defines a Distinct Multipotent Stem Cell Population in Mammalian Epidermis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura T, Hamuro J, Takaishi M, et al. LRIG1 inhibits STAT3-dependent inflammation to maintain corneal homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:385–397. doi: 10.1172/JCI71488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulin EJ, Powell AE, Wang Y, et al. Using a new Lrig1 reporter mouse to assess differences between two Lrig1 antibodies in the intestine. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirth A, Benyó Z, Lukasova M, et al. G12-G13–LARG–mediated signaling in vascular smooth muscle is required for salt-induced hypertension. Nat. Med. 2008;14:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin C-S, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev. Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller MS, Galligan JJ, Burks TF. Accurate measurement of intestinal transit in the rat. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1981;6:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(81)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki Y, Sato N, Tohyama M, et al. cDNA Cloning of a Novel Membrane Glycoprotein That Is Expressed Specifically in Glial Cells in the Mouse Brain LIG-1, A PROTEIN WITH LEUCINE-RICH REPEATS AND IMMUNOGLOBULIN-LIKE DOMAINS. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:22522–22527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Gibbons SJ, Bardsley MR, et al. Ano1 is a selective marker of interstitial cells of Cajal in the human and mouse gastrointestinal tract. Am. J. Physiol. - Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1370–G1381. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00074.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faussone-Pellegrini M-S. Relationships between neurokinin receptor-expressing interstitial cells of Cajal and tachykininergic nerves in the gut. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006;10:20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iino S, Horiguchi K, Horiguchi S, et al. c-Kit-negative fibroblast-like cells express platelet-derived growth factor receptor α in the murine gastrointestinal musculature. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2009;131:691–702. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0580-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iino S, Nojyo Y. Immunohistochemical demonstration of c-Kit-negative fibroblast-like cells in murine gastrointestinal musculature. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 2009;72:107–115. doi: 10.1679/aohc.72.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:286–294. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanders KM, Koh SD, Ro S, et al. Regulation of gastrointestinal motility—insights from smooth muscle biology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:633–645. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huizinga JD, Lammers WJEP. Gut peristalsis is governed by a multitude of cooperating mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. - Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1–G8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90380.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin J, Chen JDZ. Roles of interstitial cells of Cajal in regulating gastrointestinal motility: in vitro versus in vivo studies. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2008;12:1118–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong VWY, Stange DE, Page ME, et al. Lrig1 controls intestinal stem-cell homeostasis by negative regulation of ErbB signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:401–408. doi: 10.1038/ncb2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.