Abstract

We set out to determine whether the addition of an aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) antagonist has an effect on glucose/fructose utilization in the spermatocyte when exposed to cigarette smoke condensate (CSC). We exposed male germ cells to 5 and 40 μg/mL of CSC ± 10 μmol/L of AHR antagonist at various time points. Immunoblot expression of specific glucose/fructose transporters was compared to control. Radiolabeled uptake of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) and fructose was also performed. Spermatocytes utilized fructose nearly 50-fold more than 2-DG. Uptake of 2-DG decreased after CSC + AHR antagonist exposure. Glucose transporters (GLUTs) 9a and 12 declined after CSC + AHR antagonist exposure. Synergy between CSC and the AHR antagonist in spermatocytes may disrupt the metabolic profile in vitro. Toxic exposures alter energy homeostasis in early stages of male germ cell development, which could contribute to later effects explaining decreases in sperm motility in smokers.

Keywords: cigarette smoke, spermatocytes, fructose, GLUT9a, GLUT12

Introduction

A growing body of evidence shows that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are toxic to the testis, resulting in impaired spermatogenesis and subfertility.1–5 Although it is clear that one such PAH, 2,3,7,8 tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (ie, dioxins), acts through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) to mediate toxicity, the specific mechanisms by which PAHs exert their toxic effect remain uncertain.3,6–8

Cigarette smoke, composed of over 4000 chemicals including known carcinogens such as PAHs,9 has been linked to aberrant spermatogenesis and semen parameters associated with male factor infertility.10–13 Furthermore, cigarette smoke is known to induce biological changes that can lead to abnormalities in a smoker’s progeny.14,15

Cigarette smoke consists of 2 phases: a gas phase and a particulate phase known as cigarette smoke condensate (CSC). Upon inhalation, both forms are absorbed into the systemic circulation and accumulate in seminal plasma in the male reproductive tract, either by diffusion or by active transport. This results in alterations in the concentration, motility, and morphology of sperm, changes in the testicular hormonal environment,16 and DNA damage.13,17–21

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists have been shown to disrupt hexose metabolism in various tissues both in vivo and in vitro.8,22–25 Mammalian testes and spermatozoa are known to utilize various glucose transporters (GLUTs)26–29 that serve to transport glucose and/or fructose for critical sperm cell metabolism and function.27,28,30,31

We have recently shown that CSC induces oxidative stress, DNA damage, and seminiferous tubule cell apoptosis in mice, ultimately leading to altered sperm motility. We also examined the effect of CSC exposure on a spermatocyte cell line, which represents the premeiotic stage of spermatogenesis (eg, primary spermatocytes). These cells exhibited oxidative damage and upregulation of several antioxidant genes.1–5 Disruption of spermatocyte energy utilization may be the mechanism responsible for the abnormal semen phenotypes seen in chronic male smokers.

Identifying the mechanism of toxic injury to male germ cells will lead to a better understanding of how toxicants contribute to infertility in men. Therefore, we hypothesized that 1 reason for the damage observed in spermatocytes might be that CSC exposure results in disruptions of energy homeostasis. Here we have assessed that possibility by measuring uptake of glucose and fructose in CSC-treated spermatocytes. Additionally, we have examined the effect of CSC on expression of several hexose transporters (called GLUTs) expressed in the spermatocytes. We examine the role that blockage of the AHR receptor has on energy utilization in the spermatocyte. Finally, we provide direct observation of CSC effects on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production in spermatocytes.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and In Vitro CSC Treatment

The murine spermatocyte cell line GC-2spd(ts), American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, Virginia,32,33 was grown to 70% confluence in ATCC-formulated Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (BSA; ATCC), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Lonza, Maryland) in an air atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cells were amplified in complete medium per the manufacturer’s instructions and used between passages 5 and 11. Previous cell viability assessments using the trypan blue exclusion test demonstrated no noticeable cytotoxicity under these conditions.5 The GC-2spd(ts) cells were then grown to 70% confluence and then incubated with serum-deficient media for 24 hours to avoid any influence of growth factors.

Cigarette smoke condensate (Murty Pharmaceuticals Inc, Lexington, Kentucky) was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain a stock concentration of 40 mg/mL. Spermatocyte treatment with DMSO (0.1%), 5 mg/mL or 40 μg/mL CSC for 18 and 24 hours, was performed based on studies showing CSC effects on AHR at these time points.5 Cigarette smoke condensate was purchased commercially. The CSC is prepared using a Phipps-Bird 20-channel smoking machine designed for Federal Trade Commission testing. The particulate matter from Kentucky standard cigarettes (1R3F; University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky) is collected on Cambridge glass fiber filters, and the amount of CSC obtained is determined by increase in weight of the filter. The average yield of CSC is 26.1 mg/cigarette.

Cigarette Smoke Condensate and AHR Antagonist Treatment

Cells were treated with 10 μmol/L of the AHR antagonist CH223191, 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid-(2-methyl-4-o-tolyl-azophenyl)-amide (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, New Jersey), for 1 hour, followed by 5 or 40 μg/mL of CSC for 18 or 24 hours. Unlike other AHR antagonists, such as resveratrol and flavones, which might have weak AHR agonist properties at high concentrations, CH223191 is a pure AHR antagonist.34–36

Fructose and Glucose Uptake Assays

The GC-2spd(ts) cells were split into 12-well culture dishes and allowed to attain epithelial morphology with intercellular contacts. The GC-2spd(ts) cells were then treated as mentioned earlier with CSC ± AHR antagonist for a maximum of 24 hours, immediately after which time uptake of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) and fructose was measured. Radiolabeled fructose uptake in GC-2spd(ts) cells was measured according to established methods with the following adaptations.37 Cells were hexose deprived for 10 minutes in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The medium was changed to Ringer’s phosphate buffer containing 2 mol/L [14C]-D-fructose or [14C]-2D-glucose (American Radiochemicals, Inc, St Louis, Missouri) for 2.5 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was quenched in ice-cold HBSS, and cultures were washed in Ringer before lysis in 0.1 N NaOH and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate solution. A portion (70%) of each lysate was counted in Econosafe liquid scintillation fluid (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). We normalized uptake to cell number (4000 cells per well). Each substrate was assayed in triplicate 3 unique times.

Western Blot

After the treatment regimens, the cells were gently washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then scraped into radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 0.1 mol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri), 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1 mmol/L sodium fluoride, and 1× miniprotease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Indiana) for protein extraction. Cells were lysed by sonication on ice with three 10-s bursts. Whole cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10 000g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay. Aliquots of 30 μg of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were probed with rabbit anti-GLUT5 (Abnova, Taiwan), anti-GLUT8,38 anti-GLUT9a,39 and anti-GLUT12 antibodies26 (1:1000) followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:20 000; SantaCruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, California). Enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey) was used for detection, and the blots were reprobed with an anti-β-actin antibody for normalization. Fold changes are reported relative to DMSO control. Image J (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) was used to quantify the density of the bands.

Intracellular ATP Assay for Spermatocytes, GC-2spd(ts)

The concentration of intracellular ATP in the CSC-exposed spermatocytes was measured based on our previously published protocol with slight modifications.40 In brief, the spermatocyte cell line GC-2spd(ts), 1 × 106 cells/volume, 10-cm plate, grown in DMEM were serum starved and exposed separately to different concentrations of CSC (5, 20, and 40 mg) and equal volume of DMSO control. The cells exposed for 24 hours were harvested using 2 mL trypsin (containing 0.25% EDTA; Sigma) and equal volume of complete medium followed by centrifugation for 2 minutes at 1500 rpm. Supernatant was discarded, the pellet was washed with 1 mL cell dissociation solution (Sigma), and then extracted in 100 µL of 0.1 N NaOH by homogenization followed by incubation at 80°C for 20 minutes. The homogenate (100 µL) was neutralized with 50 µL mixture of 0.15 N HCl and 0.1 mol/L Tris–HCl (pH6.6) to form 34 mmol/L Tris–HCl (pH 8.1). The extract was used for ATP measurement by enzymatic reaction and the values were normalized to the amount of total protein in the cell lysate.

The assay was carried our using 20 microL of cell extract. Blank, ATP standards, and cell extracts were added to 50 µL of ATP reagent (60 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 8.1, 0.03% BSA, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 450 µmol/L d-glucose, 100 mmol/L nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), 3 µg/mL hexokinase without (NH4)2SO4, and 1 µg/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase without (NH4)2SO4), and the reaction was terminated after 20 minutes at 60°C for 20 minutes by adding 10 mL of 0.5 N NaOH. After adding a 1mL mixture of 6 N NaOH, 10 mmol/L imidazole, and 0.01% H2O2 were heated for 20 minutes and fluorescence was, measured using a fluorometer at 340 nm. The enhanced fluorescence of NADP+ is indicative of ATP levels.

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance followed by the Fisher least significant difference test was used to compare substrate uptake and GLUT expression between experimental treatments and DMSO control. For analysis of the equality of continuous distribution of samples, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used. Statistical significance was defined as P value < .05.

Results

Effects of CSC on Fructose and Glucose Uptake

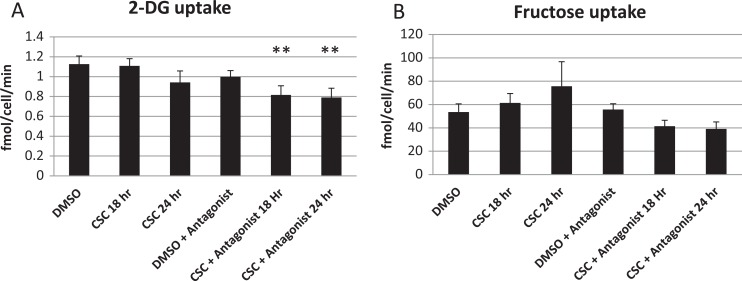

Spermatocytes took up 50-fold more fructose than 2-DG. Exposure to CSC for 24 hours slightly decreased 2-DG uptake while slightly increasing fructose uptake, but the differences were not statistically significant. The addition of an AHR antagonist alone did not significantly alter fructose or 2-DG uptake, but uptake of 2-DG was significantly (P = .01) lower and uptake of fructose trended toward a decrease in cells exposed to both CSC and AHR antagonist (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) ± aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) antagonist on hexose uptake. A, 2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG) uptake by spermatocytes treated with the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle control), CSC (40 μg/mL), AHR antagonist, or CSC + AHR antagonist, as indicated. N = 2 experiments in triplicate. B, Fructose uptake by spermatocytes treated with the DMSO (vehicle control), CSC, AHR antagonist, or CSC + AHR antagonist, as indicated. ** indicates P = .01 (analysis of variance [ANOVA] compared to DMSO). N = 2 experiments in triplicate. All values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Effects of CSC on Expression of GLUTs

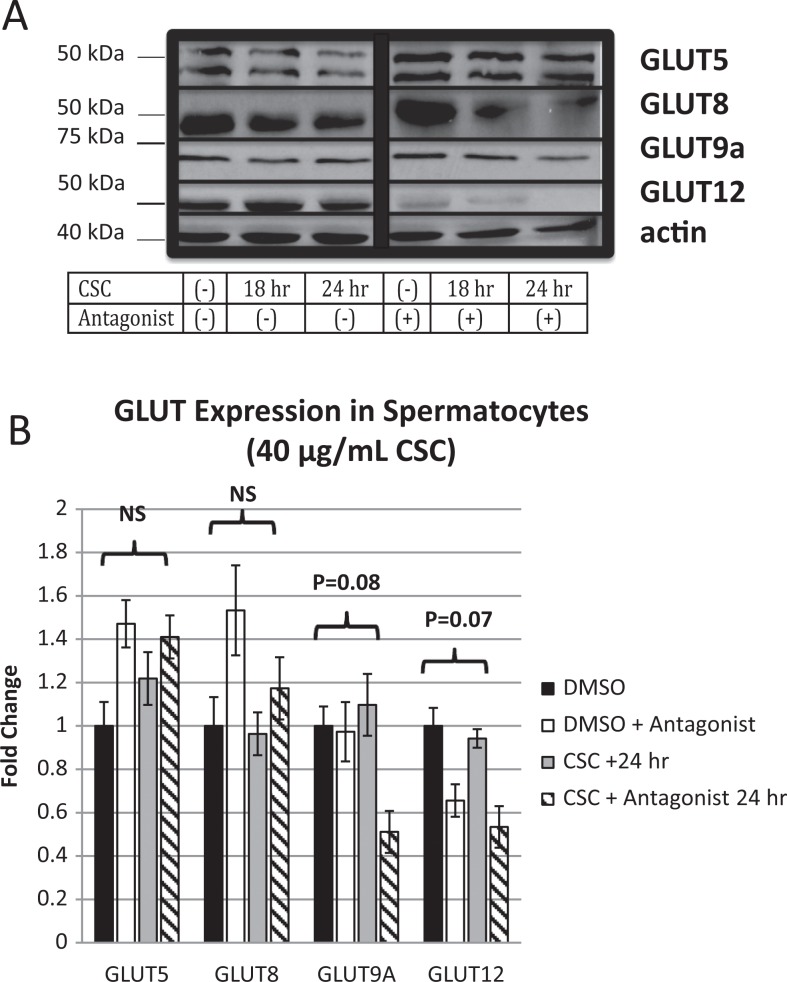

We have previously demonstrated that the GLUT9a and GLUT8 are expressed in mouse spermatocytes in vivo.27,41 Others have also shown that GLUT5 is a fructose transporter present in spermatocytes in vivo.42 We thus first confirmed that these GLUTs are all expressed at the protein level in the GC-2spd(ts) cells in vitro (Figure 2A). Furthermore, as GLUT12 expression has been shown to be dependent on GLUT8 expression in other systems of fructose transport,37 we examined expression of this protein as well and found its expression in spermatocytes in vitro.

Figure 2.

Glucose transporter (GLUT) expression profile of spermatocytes. A, Western blot of previously (GLUT 5, 8, and 9a) and newly (GLUT 12) described GLUT transporters present in murine spermatocytes. Cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) alone does not affect whole cell protein expression among GLUT 5, 8, 9a, and 12; however, GLUT 9a and GLUT 12 begin to decrease with concurrent exposure to AHR antagonist. All Western immunoblots represent multiple determinations (>3). B, Quantification of fold change (expressed as standard error of the mean [SEM]) among GLUT 5, 8, 9a, and 12 normalized to actin. Comparisons between control (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) and CSC + antagonist for 24 hours for GLUT 9A and GLUT 12 approach significance.

Levels of GLUT9a did not change with exposure to 40 μg/mL CSC; however, the addition of the AHR antagonist decreased protein levels by 51%, a change that approached statistical significance (P = .08). The GLUT12 is present on murine spermatocytes, though, its expression did not change significantly when exposed to 40 μg/mL CSC. The addition of the AHR antagonist reduced the level of expression by 53%, approaching statistical significance (P = .07). Expression of GLUT5 and GLUT8 did not change with exposure to 40 μg/mL CSC ± AHR antagonist (Figure 2B).

In order to determine whether this effect of CSC was dose dependent, the above-mentioned experiments were repeated in triplicate with 5 μg/mL. No significant change in expression of GLUT9a or GLUT12 was seen with this lower concentration (data not shown). As a result, the effect appears to be dependent on the dose of CSC added.

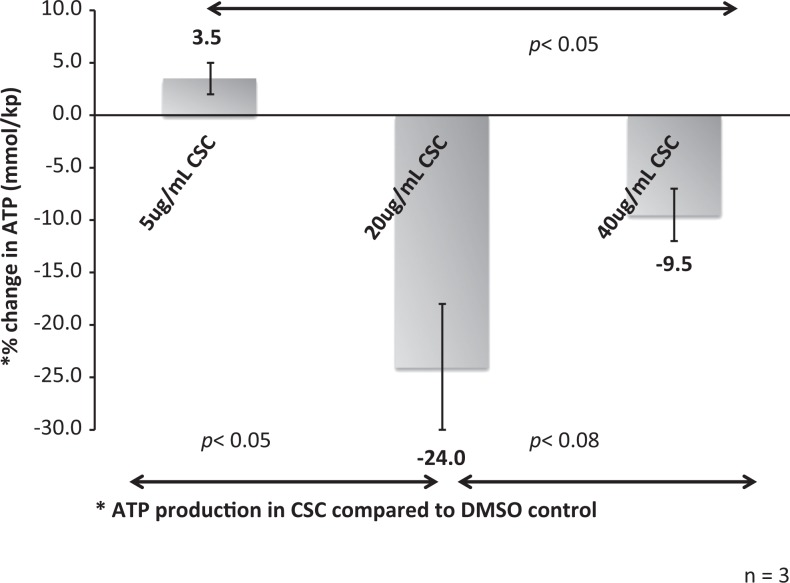

Cigarette Smoke Condensate Lowers ATP Production in Spermatocytes

Intracellular ATP production was measured after exposure to varying concentrations of CSC (5 µg/mL, 20 µg/mL, and 40 µg/mL) compared to control. At 20 and 40 µg/mL of CSC exposure, ATP production was attenuated 18% and 12%, respectively, from baseline suggesting that there is a downstream effect of CSC on energy production in the spermatocyte. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Effect of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production in spermatocytes. When examining the percentage change in ATP production in CSC-exposed spermatocytes compared to control (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]), there is a significant dose-dependent effect. With both 20 and 40 μg/mL CSC, the spermatocyte ATP production decreased significantly (P < .05) compared to 5 μg/mL.

Discussion

Here, we have shown that fructose is utilized more than 2-DG in spermatocytes and that chronic CSC exposure alone does not influence uptake of substrate. However, when combined with the AHR antagonist, 2-DG uptake is significantly decreased. Furthermore, protein expression of GLUT9a and GLUT12 decreases from control after the pure AHR antagonist (CH223191) is added with 40 μg/mL CSC but not 5 μg/mL. Finally, we show that ATP production is decreased suggesting that CSC has both direct and indirect effects on cellular metabolism.

Previously, we showed that accumulation of reactive oxygen species and messenger RNA expression of antioxidant genes (Hsp90, Nrf2, and Cyp1a1) peak at 6 hours.5 When examining protein expression levels, peak expression occurred between 20 and 24 hours after exposure. Addition of the AHR antagonist mitigated this expression; however, when examining CSC and AHR antagonist exposure together, the effect on spermatocyte energy utilization appears to be different.

Environmental exposures ranging from diesel exhaust43,44 to cigarette smoke13 have been implicated in reductions in sperm count, motility, viability, and oxidative stress leading to DNA damage, but many of these observations have been made in the latter stages of spermatogenesis. Furthermore, evidence suggests that once spermatozoa escape the Sertoli cell environment, toxic exposures and resulting oxidative stress can lead to worsening DNA damage.46

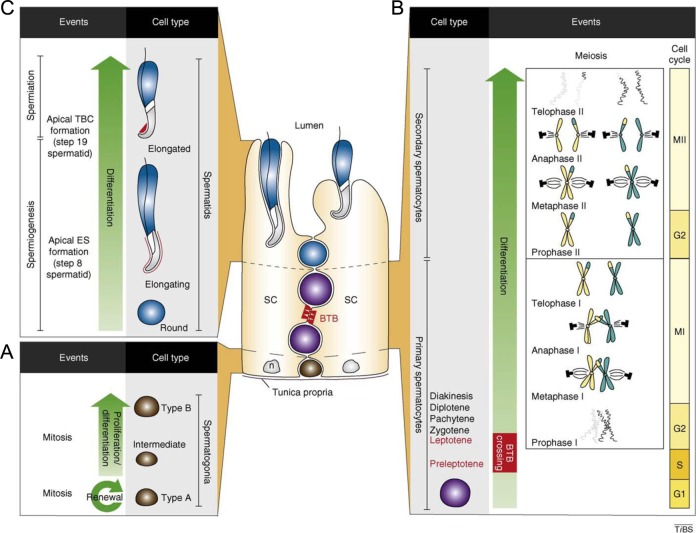

Spermatogenesis is the process by which male germ cells develop. Spermiogenesis is the process by which spermatids undergo morphologic changes to package their DNA, thus acquiring their characteristic shape. Spermiation is the process by which spermatozoa are released into the lumen of the seminiferous tubule and then travel to the epididymis where they acquire their motility (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Spermatogenesis. Type A spermatogonia undergoing mitosis and either replenishing pool of germ cells or differentiating into type B spermatogonia (basal compartment of seminiferous tubule). Meiosis I and II: preleptotene spermatocytes cross blood testis barrier (BTB) into adluminal compartment where meiosis II produces haploid round spermatids. Spermiogenesis and spermiation: haploid round spermatids undergo spermiogenesis, which is defined by the formation of the acrosome, and are released from the seminiferous epithelium into tubules. Reprinted from Lie PPY, Cheng Y, Mruk, DD. Coordinating cellular events during spermatogenesis: a biochemical model. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2009;34:366-373 with permission from Elsevier.45

A body of evidence4,47–49 suggests that toxic exposures in premeiotic stages of male germ cell development may be responsible for adverse phenotypes in latter stages of spermatogenesis effecting mature sperm’s motility, viability, impaired acrosome reaction, and subsequent fertilization suggesting that early exposures lead to late effects.48,49

Previously, we have used an in vitro spermatocyte cell line to model how environmental toxins potentiate increases in oxidative stress,5,50 providing further explanation for the mechanism behind abnormal semen parameters and perhaps subfertility seen in male smokers. Here, under similar conditions, we show that cigarette smoke can influence hexose utilization, perhaps leading to a preference for fructose among spermatocytes in vitro.

Glucose transporter 5 is abundantly expressed in human spermatozoa and is known to transport fructose with high affinity.42,51 The relationship between AHR and energy utilization and transport has been described in other tissues.8,22,52 Specifically, activation of cytochrome p450 1A1 (CYP1A1) leads to a profile of increased expression of GLUT1/GLUT3 and concomitant increases in glucose utilization in CaCo2 cells.52 When CYP1A1 is no longer detectable, expression of GLUT5 is increased and fructose uptake increases while glucose consumption decreases.52 This reciprocal relationship between different hexose preference and AHR activation parallels findings in this study.

Furthermore, constitutively activated AHR promotes transformed growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling, which is responsible for cell proliferation. In glioma cells, the AHR antagonist (CH223191) is known to reduce TGF-β and cellular proliferation.53

In our model, CSC simulates an activated AHR state, after the addition of the antagonist, 2-DG uptake decreases and fructose uptake trends downward (Figure 1). Although sperm’s primary substrate is glucose, we measured 2-DG uptake instead, since it is phosphorylated by hexokinases and is trapped in the cell, which allows for an accurate measurement of uptake.

Furthermore GLUT5, a dominant fructose transporter, expression remains constant with addition of the antagonist while GLUT9a and GLUT12, 2 hexose transporters that have specificity for both glucose and fructose, decrease (Figure 2B).

These findings suggest a role for GLUT9a and GLUT12 as a newly evolved, redundant transport system designed to maintain energy substrate in times of stress. As the stress increases with the addition of the AHR antagonist, secondary GLUTs like 9a and 12 are the first to downregulate and thus decrease the ability of the cells to transport critical energy substrates resulting in a decrease in ATP production and a loss of cellular function. In mature spermatids, for example, hypoexpression of GLUT9a is associated with low motility and fertilization rate.27,54

Fructose uptake was several orders of magnitude higher than 2-DG uptake (˜50-fold), suggesting a metabolic profile favoring fructose utilization. This is possibly due to the fact that GLUT5, a dominant fructose transporter, is stable throughout the experiment’s time points allowing influx of fructose. Alternatively, this could also be due to the fact that 2-DG has a lower affinity for the GLUTs than glucose.55

In vitro, spermatocyte exposure to CSC, or other environmental toxins like dioxins, results in an AHR-dependent upregulation of downstream antioxidant genes like Cyp1a1.56 The AHR antagonists have recently been shown to mitigate the toxic effects of cigarette smoke in both male and female germ cells.5,57 When examining this relationship from the perspective of hexose utilization in the spermatocyte, it appears that the AHR antagonist in combination with the CSC alters the transporter profile of the cell with changes in hexose uptake.

Although spermatocytes exposed to CSC alone did not result in significant changes in whole cell expression of most GLUTs, the addition of an AHR antagonist resulted in a decrease in GLUT9a (P = .08) and GLUT12 (P = .07). Although GLUT1, GLUT2, GLUT3, and GLUT5 are primarily responsible for fructose transport, secondary transporters, perhaps ultimately for the needs of the mature spermatid, are involved in fine-tuning the metabolic needs of the cell.27

Cigarette smoke and other environmental contaminants have been linked to abnormal semen parameters and subfertility in men, but a biological mechanism of toxicity remains elusive.18,58 Altered hexose utilization appears to disrupt cellular respiration in spermatocytes during exposure to CSC, which, in turn, is responsible for a decrease in ATP production and resultant oxidative stress and cell death seen previously. Finally, our work highlights a growing interest in the role of GLUTs in the functional aspects of the male gamete, and further investigation into the energetics of male germ cells could lead to a better understanding of cigarette smoke effect on sperm motility.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Dr Deborah Frank for her suggestions and scientific writing expertise.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support: (KO) F32 HD040135-10 NIH; (DB) 5K12HD000850-27 Pediatric Scientist Development Program NIH.

References

- 1. Ding YS, Ashley DL, Watson CH. Determination of 10 carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mainstream cigarette smoke. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55 (15):5966–5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Georgellis A, Montelius J, Rydstrom J. Evidence for a free-radical-dependent metabolism of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene in rat testis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1987;87 (1):141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schultz R, Suominen J, Varre T, et al. Expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator messenger ribonucleic acids and proteins in rat and human testis. Endocrinology. 2003;144 (3):767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Georgellis A, Toppari J, Veromaa T, Rydstrom J, Parvinen M. Inhibition of meiotic divisions of rat spermatocytes in vitro by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Mutat Res. 1990;231 (2):125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Esakky P, Hansen DA, Drury AM, Moley KH. Cigarette smoke condensate induces aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent changes in gene expression in spermatocytes. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;34 (4):665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gray LE, Ostby JS, Kelce WR. A dose-response analysis of the reproductive effects of a single gestational dose of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in male Long Evans Hooded rat offspring. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;146 (1):11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pohjanvirta R, Tuomisto J. Short-term toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in laboratory animals: effects, mechanisms, and animal models. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46 (4):483–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tonack S, Kind K, Thompson JG, Wobus AM, Fischer B, Santos AN. Dioxin affects glucose transport via the arylhydrocarbon receptor signal cascade in pluripotent embryonic carcinoma cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148 (12):5902–5912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith CJ, Hansch C. The relative toxicity of compounds in mainstream cigarette smoke condensate. Food Chem Toxicol. 2000;38 (7):637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hughes EG, Brennan BG. Does cigarette smoking impair natural or assisted fecundity? Fertil Steril. 1996;66 (5):679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sofikitis N, Miyagawa I, Dimitriadis D, Zavos P, Sikka S, Hellstrom W. Effects of smoking on testicular function, semen quality and sperm fertilizing capacity. J Urol. 1995;154 (3):1030–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stillman RJ, Rosenberg MJ, Sachs BP. Smoking and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 1986;46 (4):545–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vine MF. Smoking and male reproduction: a review. Int J Androl. 1996;19 (6):323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marczylo EL, Amoako AA, Konje JC, Gant TW, Marczylo TH. Smoking induces differential miRNA expression in human spermatozoa: a potential transgenerational epigenetic concern? Epigenetics. 2012;7 (5):432–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohamed el SA, Song WH, Oh SA, et al. The transgenerational impact of benzo(a)pyrene on murine male fertility. Hum Reprod. 2010;25 (10):2427–2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blanco-Munoz J, Lacasana M, Aguilar-Garduno C. Effect of current tobacco consumption on the male reproductive hormone profile. Sci Total Environ. 2012;426:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merisalu A, Punab M, Altmae S, et al. The contribution of genetic variations of aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway genes to male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2007;88 (4):854–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramlau-Hansen CH, Thulstrup AM, Aggerholm AS, Jensen MS, Toft G, Bonde JP. Is smoking a risk factor for decreased semen quality? A cross-sectional analysis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22 (1):188–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saleh RA, Agarwal A. Oxidative stress and male infertility: from research bench to clinical practice. J Androl. 2002;23 (6):737–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viczian M. The effect of cigarette smoke inhalation on spermatogenesis in rats. Experientia. 1968;24 (5):511–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zavos PM, Correa JR, Karagounis CS, et al. An electron microscope study of the axonemal ultrastructure in human spermatozoa from male smokers and nonsmokers. Fertil Steril. 1998;69 (3):430–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishida T, Kan-o S, Mutoh J, et al. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced change in intestinal function and pathology: evidence for the involvement of arylhydrocarbon receptor-mediated alteration of glucose transportation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;205 (1):89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu PC, Matsumura F. TCDD suppresses insulin-responsive glucose transporter (GLUT-4) gene expression through C/EBP nuclear transcription factors in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2006;20 (2):79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Olsen H, Enan E, Matsumura F. Regulation of glucose transport in the NIH 3T3 L1 preadipocyte cell line by TCDD. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102 (5):454–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tuomisto JT, Pohjanvirta R, Unkila M, Tuomisto J. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced anorexia and wasting syndrome in rats: aggravation after ventromedial hypothalamic lesion. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;293 (4):309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Purcell SH, Aerni-Flessner LB, Willcockson AR, Diggs-Andrews KA, Fisher SJ, Moley KH. Improved insulin sensitivity by GLUT12 overexpression in mice. Diabetes. 2011;60 (5):1478–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim ST, Moley KH. The expression of GLUT8, GLUT9a, and GLUT9b in the mouse testis and sperm. Reprod Sci. 2007;14 (5):445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim ST, Moley KH. Paternal effect on embryo quality in diabetic mice is related to poor sperm quality and associated with decreased glucose transporter expression. Reproduction. 2008;136 (3):313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Purcell SH, Moley KH. Glucose transporters in gametes and preimplantation embryos. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20 (10):483–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gomez O, Romero A, Terrado J, Mesonero JE. Differential expression of glucose transporter GLUT8 during mouse spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2006;131 (1):63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schurmann A, Axer H, Scheepers A, Doege H, Joost HG. The glucose transport facilitator GLUT8 is predominantly associated with the acrosomal region of mature spermatozoa. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307 (2):237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolkowicz MJ, Coonrod SA, Reddi PP, Millan JL, Hofmann MC, Herr JC. Refinement of the differentiated phenotype of the spermatogenic cell line GC-2spd(ts). Biol Reprod. 1996;55 (4):923–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hofmann MC, Hess RA, Goldberg E, Millan JL. Immortalized germ cells undergo meiosis in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91 (12):5533–5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim SH, Henry EC, Kim DK, et al. Novel compound 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide (CH-223191) prevents 2,3,7,8-TCDD-induced toxicity by antagonizing the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69 (6):1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoshida T, Katsuya K, Oka T, et al. Effects of AHR ligands on the production of immunoglobulins in purified mouse B cells. Biomed Res. 2012;33 (2):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang S, Qin C, Safe SH. Flavonoids as aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists/antagonists: effects of structure and cell context. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111 (16):1877–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Debosch BJ, Chi M, Moley KH. Glucose Transporter 8 (GLUT8) Regulates Enterocyte Fructose Transport and Global Mammalian Fructose Utilization. Endocrinology. 2012;153 (9):4181–4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carayannopoulos MO, Chi MM, Cui Y, et al. GLUT8 is a glucose transporter responsible for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in the blastocyst. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97 (13):7313–7318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carayannopoulos MO, Schlein A, Wyman A, Chi M, Keembiyehetty C, Moley KH. GLUT9 is differentially expressed and targeted in the preimplantation embryo. Endocrinology. 2004;145 (3):1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Evans SA, Doblado M, Chi MM, Corbett JA, Moley KH. Facilitative glucose transporter 9 expression affects glucose sensing in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150 (12):5302–5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Adastra KL, Frolova AI, Chi MM, et al. Slc2a8 deficiency in mice results in reproductive and growth impairments. Biol Reprod. 2012;87 (2):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Burant CF, Takeda J, Brot-Laroche E, Bell GI, Davidson NO. Fructose transporter in human spermatozoa and small intestine is GLUT5. J Biol Chem. 1992;267 (21):14523–14526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang JY, Liao JW, Liu YC, et al. Motorcycle exhaust induces reproductive toxicity and testicular interleukin-6 in male rats. Toxicol Sci. 2008;103 (1):137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Izawa H, Kohara M, Watanabe G, Taya K, Sagai M. Diesel exhaust particle toxicity on spermatogenesis in the mouse is aryl hydrocarbon receptor dependent. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53 (5):1069–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lie PPY, Cheng Y, Mruk DD. Coordinating cellular events during spermatogenesis: a biochemical model. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2009;34:366–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gharagozloo P, Aitken RJ. The role of sperm oxidative stress in male infertility and the significance of oral antioxidant therapy. Hum Reprod. 2011;26 (7):1628–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Onoda M, Djakiew D. Pachytene spermatocyte protein(s) stimulate sertoli cells grown in bicameral chambers: dose-dependent secretion of ceruloplasmin, sulfated glycoprotein-1, sulfated glycoprotein-2, and transferrin. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1991;27A (3 pt 1):215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pina-Guzman B, Sanchez-Gutierrez M, Marchetti F, Hernandez-Ochoa I, Solis-Heredia MJ, Quintanilla-Vega B. Methyl-parathion decreases sperm function and fertilization capacity after targeting spermatocytes and maturing spermatozoa. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;238 (2):141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pina-Guzman B, Solis-Heredia MJ, Rojas-Garcia AE, Uriostegui-Acosta M, Quintanilla-Vega B. Genetic damage caused by methyl-parathion in mouse spermatozoa is related to oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216 (2):216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Esakky P, Hansen DA, Drury AM, Moley KH. Molecular analysis of cell type-specific gene expression profile during mouse spermatogenesis by laser microdissection and qRT-PCR. Reprod Sci. 2013;20 (3):238–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Angulo C, Rauch MC, Droppelmann A, et al. Hexose transporter expression and function in mammalian spermatozoa: cellular localization and transport of hexoses and vitamin C. J Cell Biochem. 1998;71 (2):189–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Carriere V, Barbat A, Rousset M, et al. Regulation of sucrase-isomaltase and hexose transporters in Caco-2 cells: a role for cytochrome P-4501A1? Am J Physiol. 1996;270 (6 pt 1):G976–G986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gramatzki D, Pantazis G, Schittenhelm J, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor inhibition downregulates the TGF-beta/Smad pathway in human glioblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2009;28 (28):2593–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim ST, Omurtag K, Moley KH. Decreased spermatogenesis, fertility, and altered Slc2A expression in Akt1-/- and Akt2-/- testes and sperm. Reprod Sci. 2012;19 (1):31–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li Q, Manolescu A, Ritzel M, et al. Cloning and functional characterization of the human GLUT7 isoform SLC2A7 from the small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287 (1):G236–G242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kitamura M, Kasai A. Cigarette smoke as a trigger for the dioxin receptor-mediated signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2007;252 (2):184–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Neal MS, Mulligan Tuttle AM, Casper RF, Lagunov A, Foster WG. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists attenuate the deleterious effects of benzo[a]pyrene on isolated rat follicle development. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21 (1):100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jurewicz J, Hanke W, Radwan M, Bonde JP. Environmental factors and semen quality. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2009;22 (4):305–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]