Abstract

Non-thermal irreversible electroporation (N-TIRE) has shown promise as an ablative therapy for a variety of soft-tissue neoplasms. Here we describe the therapeutic planning aspects and first clinical application of N-TIRE for the treatment of an inoperable, spontaneous malignant intracranial glioma in a canine patient. The N-TIRE ablation was performed safely, effectively reduced the tumor volume and associated intracranial hypertension, and provided sufficient improvement in neurological function of the patient to safely undergo adjunctive fractionated radiotherapy (RT) according to current standards of care. Complete remission was achieved based on serial magnetic resonance imaging examinations of the brain, although progressive radiation encephalopathy resulted in the death of the dog 149 days after N-TIRE therapy. The length of survival of this patient was comparable to dogs with intracranial tumors treated via standard excisional surgery and adjunctive fractionated external beam RT. Our results illustrate the potential benefits of N-TIRE for in vivo ablation of undesirable brain tissue, especially when traditional methods of cytoreductive surgery are not possible or ideal, and highlight the potential radiosensitizing effects of N-TIRE on the brain.

Keywords: Electroporation, brain tumor, brain cancer, neurosurgery, dog

Introduction

High-grade gliomas, most notably glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), are among the most aggressive of all malignancies in humans and dogs. High-grade variants of gliomas are difficult to treat and generally considered incurable with singular or multimodal therapies (1, 2). Many patients with GBM die within one year of diagnosis, and the 5-year survival rate in people is approximately 10% (2). Despite extensive research and advancement in diagnostic and therapeutic technologies, very few therapeutic developments have emerged that significantly improve survival for humans with GBM over the last seven decades (2).

Dogs with spontaneous brain tumors have been shown to be excellent translational models of human disease. Intracranial spontaneous primary tumors in dogs are three times more common than in humans, and brachycephalic breeds of dogs have predispositions to the development of gliomas (3). Canine malignant gliomas (MG) exhibit similar clinical, biologic, pathologic, molecular, and genetic properties as their human counterparts (3–5). The husbandry practices of many dog owners in developed countries may allow dogs to be considered sentinels for environmental risk factors associated with tumorigenesis. Dogs are of a suitable size that allows accelerated development and application of novel diagnostic and therapeutic clinical procedures. The physiological and neurologic functions of dogs with brain tumors can be readily assessed by changes in their interactions and learned behaviors and by a battery of clinical neurological examination methods.

Prognostic factors for dogs with primary intracranial neoplasms include both tumor histology, anatomic tumor location, and type of treatment administered (6). Prolonged survivals are rare in dogs with glial-origin neoplasms, irrespective of the type of treatment administered, and death is often attributed to recurrent local disease (6). Median survivals of 0.2, 0.9, and 4.9 months have been reported for dogs with several types of brain tumors receiving either symptomatic therapy, cytoreductive surgery, or multimodal therapy (surgery and radiotherapy or hyperthermia), respectively, illustrating the poor long term prognosis for dogs with brain tumors and need for the development of more effective therapies (6).

Considering the therapeutic challenge that human and veterinary neurosurgeons are faced with when managing patients with MG, many recent efforts have been directed into the development of minimally invasive techniques that can be used for focal neoplastic tissue ablation as alternatives to traditional surgical approaches. Thermal-dependent tissue ablation techniques, such as cryoablation (7), laser interstitial thermotherapy (8), and radiofrequency lesioning (9) have been developed, but with limited success or applicability in the brain primarily due to the heat sink effect associated with the vascular brain parenchyma.

Electroporation, which results in an increase in the permeability of the cell membrane, is initiated by exposing cells or tissues to external electric fields (10, 11). The electric fields induce a transmembrane potential (the electric potential difference across the plasma membrane) which is dependent on a variety of conditions such as tissue type, cell size, and pulse parameters including pulse strength and shape, duration, number, and pulse frequency. As a function of the induced transmembrane potential, the electroporation pulse can either: have no effect on the cell membrane, reversibly permeabilize the cell membrane after which cells can survive (reversible electroporation), or permeabilize the cell membrane in a manner that leads to cell death (irreversible electroporation).

When applied in tissue, it has been shown that certain electric field parameters can achieve irreversible electroporation without causing thermal damage to the treated volume (12), a process which is referred to as non-thermal irreversible electroporation (N-TIRE). N-TIRE is a novel tissue ablation technique that involves delivery of electrical pulses above critical, tissue-specific electric field thresholds which results in permeabilization of cells presumably through formation of nanoscale aqueous pores in cytoplasmic membranes, and resultant death of cells within a treated volume (12). The minimally invasive procedure involves placing 1-mm electrodes into the targeted area and delivering a series of electrical pulses for several minutes. N-TIRE affects essentially only one component of the tissue, the lipid bilayer, and spares other critical components of the tissue such as major blood vessels, nerves and the extracellular matrix (13, 14).

Recently, N-TIRE has shown promise as a therapy for soft-tissue neoplasms, using minimally invasive instrumentation and allowing for treatment monitoring with routine clinical procedures (13, 15, 16). We believe that the N-TIRE technology possesses other inherent properties that make it well suited for the treatment of brain lesions in which the therapeutic intent is focal and highly controlled tissue destruction. The thermal sparing effect of N-TIRE is advantageous compared to previously described methods of tissue destruction that are dependent on local tissue temperature changes. Studies of focal N-TIRE ablations in mammalian liver and prostate have shown that therapeutic protocols are safe and can be implemented to preserve the integrity of sensitive tissues, such as the major vasculature and ductal frameworks within treated parenchymal volumes (16–18). In addition, other researchers have shown theoretically that N-TIRE can be used in a minimally endovascular approach for the treatment of restenosis after stent implantation or in tumors located in proximity to blood vessels (19). We have previosuly demonstrated the safety, vascular sparing, and other focal ablative characteristics of N-TIRE in the normal canine brain (20, 21).

Here we describe the first application of N-TIRE for the in vivo treatment of an inoperable spontaneous canine intracranial MG as part of a comprehensive multimodal therapeutic strategy, highlighting its potential for more widespread clinical usage for the ablation of undesirable brain tissue. This case study demonstrates the ability of N-TIRE to safely ablate pathologically heterogeneous brain tissue while preserving vascular integrity and patient neurological functions. We illustrate the minimally invasive nature of N-TIRE and the ability to plan and execute N-TIRE therapy using procedures routinely used in clinical evaluation of the neurosurgical patient. Finally, we present practical and theoretical considerations that require further investigation to better define and refine N-TIRE treatment parameters within the intracranial environment.

Materials and Methods

Case History

The patient was a 12-year-old, castrated male, mixed breed dog with an 8 week history of visual deficits of the right eye and partial seizures, which progressed to behavioral changes and ataxia of all limbs the week prior to referral to the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Teaching Hospital Neurology and Neurosurgery Service. Upon admission, the dog had normal vital parameters. Neurological evaluation revealed mild generalized proprioceptive ataxia, right hemiparesis, aggressive behavior, and propulsive circling to the left. Visual tracking and the menace response were absent in the right eye, with intact direct and consensual pupillary light reflexes. Postural reaction deficits were detected in both right thoracic and pelvic limbs. No other significant physical examination abnormalities were detected. The history and neurological abnormalities present were consistent with a lesion in the left prosencephalon.

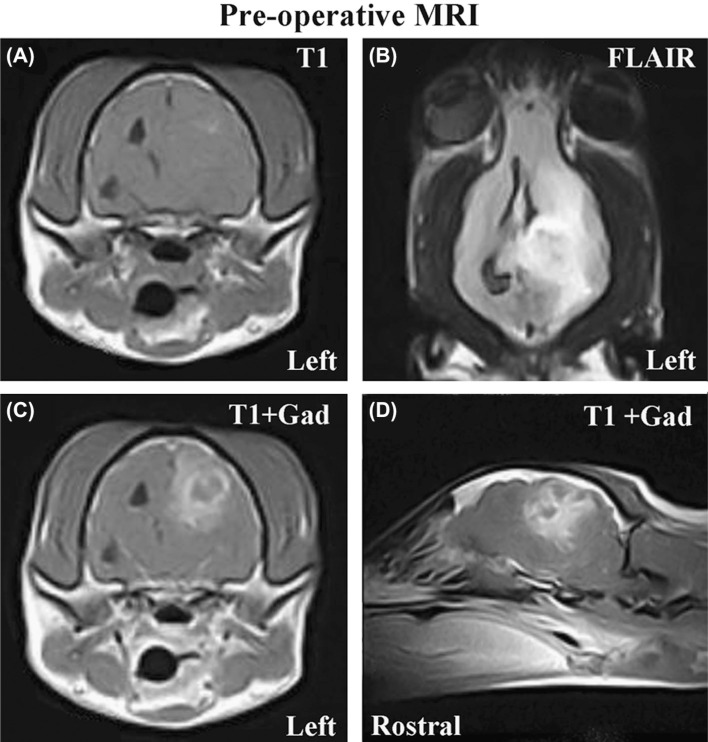

Magnetic resonance images (MRI) of the brain were obtained under general anesthesia. An intra-axial mass lesion, originating in the subcortical white matter of the left parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes of the cerebrum was noted on MRI (Figure 1). The mass was poorly marginated, heterogeneously iso-to hyperintense on T1 (Figure 1A), T2, and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR; Figure 1B) sequences, and demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement following intravenous administration of gadolinium (Figure 1C–D). Significant perilesional edema was present throughout the left cerebral hemisphere, and mass effect was manifested as obliteration of the left lateral ventricle, falx cerebri shift to the right, transtentorial herniation of the left occipital lobe of the cerebrum resulting in mesencephalic compression (Figure 1), and foramen magnum herniation. The MRI characteristics were consistent with a glial-origin neoplasm associated with subacute intraparenchymal brain hemorrhage. For treatment of the peritumoral edema, intravenous 20% mannitol and corticosteroids were administered.

Figure 1:

Pre-operative MRI scans (A-axial T1 pre-contrast; B-Dorsal FLAIR; C-axial T1 post-contrast; D-left parasagittal T1 postcontrast) revealing large, intra-axial mass lesion in the left cerebrum associated with secondary peritumoral edema, hemorrhage, and mass effect manifested as obliteration of the left lateral ventricle and shifting of the third ventricle to the right of midline.

N-TIRE Treatment Planning

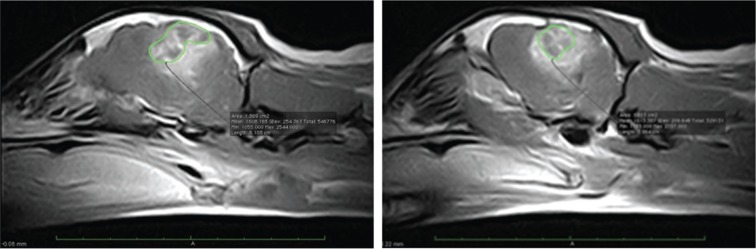

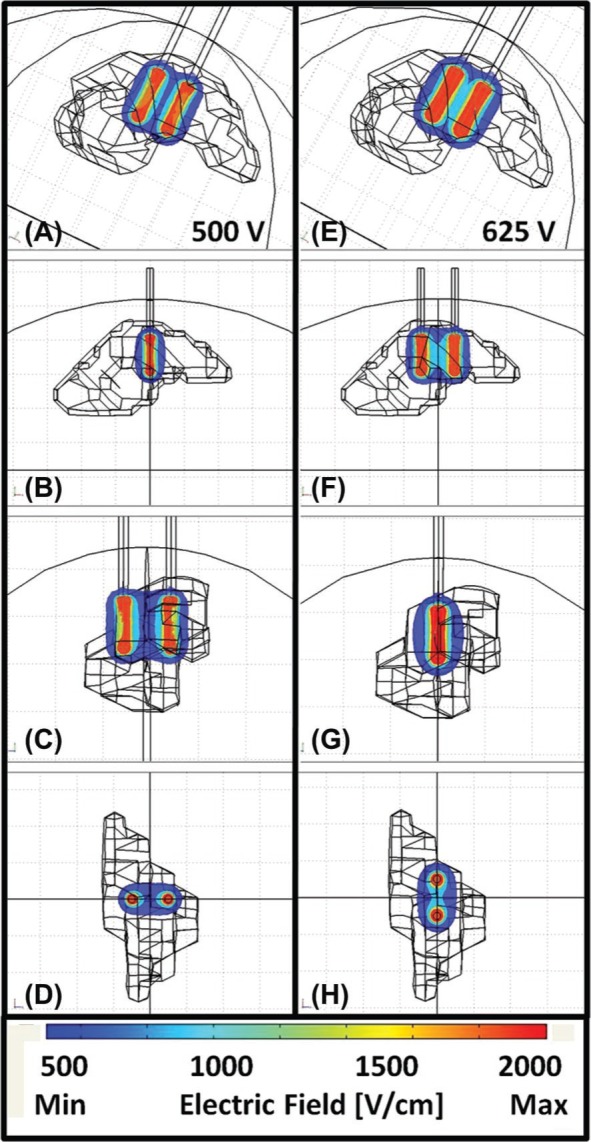

Open source image analysis software (OsiriX, Geneva, Switzerland) was used to isolate the brain tumor geometry from the normal brain tissue. The tumor was traced in each of the two-dimensional (2-D) diagnostic T1 post-contrast MRI scans as seen in Figure 2. Attempts were made to exclude regions of peritumoral edema from the tumor volume by composite modeling of the tumor geometry using all available MRI sequences (T1 pre-and post-contrast, T2, and FLAIR) and image planes. A three-dimensional (3-D) solid representation of the tumor volume (Figure 3) was generated using previously reported reconstruction procedures (21). The tumor geometry was then imported into a numerical modeling (Comsol Multiphysics, v.3.5a, Stockholm, Sweden) software in order to simulate the physical effects of the electric pulses in the tumor and surrounding healthy brain tissue. The electric field distribution was determined using the method described in (22) in which the tissue conductivity incorporates the dynamic changes that occur during electroporation (23). In our model we assumed a 50 % increase in conductivity when the tissue was exposed to an electric field magnitude greater than 500 V/cm, which we have shown as a N-TIRE threshold for brain tissue using specific experimental conditions (22). Currently, the threshold for brain tumor tissue is unknown so the same magnitude as normal tissue was used for treatment planning purposes.

Figure 2:

Consecutive T1 post-contrast MRI images in the left parasagittal plane of a canine glioma patient. The tumor is delineated in green and there is marked peritumoral edema and hemorrhage. Rostral is to the left in both images.

Figure 3:

Brain, electrodes and reconstructed tumor geometry imported into numerical software for N-TIRE treatment planning. 3-D electric field distributions corresponding to the (A-D) 500 V and (E-H) 625 V treatment protocols (Table I).

Based on the tumor dimensions and numerical simulations, we determined pulse parameters that would only affect tumor tissue (Table I). The resulting electric field distributions from these parameters are displayed in Figure 3. The two sets of pulse strengths were delivered in perpendicular directions to ensure uniform coverage of the tumor and were synchronized with the electrocardiogram (ECG) signal to prevent ventricular fibrillation or other cardiac arrhythmias (Ivy Cardiac Trigger Monitor 3000, Branford, CT, USA). The sets of pulses were delivered with alternating polarity between the sets to reduce charge build-up on the surface of the electrodes. In addition, shorter pulse durations than those used in previous N-TIRE studies (15, 17, 18) were used in order to reduce the charge delivered to the tissue and decrease resistive heating during the procedure. Our calculations and temperature measurements from previous intracranial N-TIRE procedures ensured that no thermal damage would be generated in normal brain. The temperature measured at the electrode tip resulted in a maximum 0.5°C increase after four sets of twenty 50-ps pulses when using similar pulse parameters to the ones in Table I (24). In addition, the charge delivered during the procedure was typical or lower than that used in humans during electroconvulsive therapy, a treatment for depression that also uses electric pulses (25).

Table I.

N-TIRE treatment protocol for canine malignant glioma patient.

| Voltage (V) | Electrode gap (cm) | Electrode exposure (cm) | Volt-to-dist ratio (V/cm) | Pulse duration | Number of pulses | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1000 | 50 μs | 2 × 20 | ECG synchronized |

| 625 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1250 | 50 μs | 4 × 20 | ECG synchronized |

N-TIRE Therapy

Total intravenous general anesthesia was induced and maintained with propofol and fentanyl constant rate infusions. A routine left rostrotentorial approach to the canine skull was performed and a limited left parietal craniectomy defect was created. The craniectomy size was limited to the minimum area necessary to accommodate placement of the N-TIRE electrode configurations required to treat the tumor, as determined from pre-operative treatment plans. Following regional durectomy, multiple biopsies of the mass lesion were obtained, which were consistent with a high-grade (World Health Organization Grade III) mixed glioma.

After administration of appropriate neuromuscular blockade and based on the treatment planning, focal ablative N-TIRE lesions were created in the tumor using the NanoKnife® (AngioDynamics, Queensbury, NY USA), and blunt tip electrodes. The NanoKnife® is an electric pulse generator in which the desired N-TIRE pulse parameters (voltage, pulse duration, number of pulses, and pulse frequency) are entered. The NanoKnife® is also designed to monitor the resulting current from the treatment and to automatically suspend the delivery of the pulses if a current threshold is exceeded.

The electrodes were inserted into the tumor tissue in preparation for pulse delivery. The blunt tip electrodes were connected via a 6-foot insulated wire (cable) to the generator. After foot pedal activation, the pulses were conducted from the generator to the exposed electrodes.

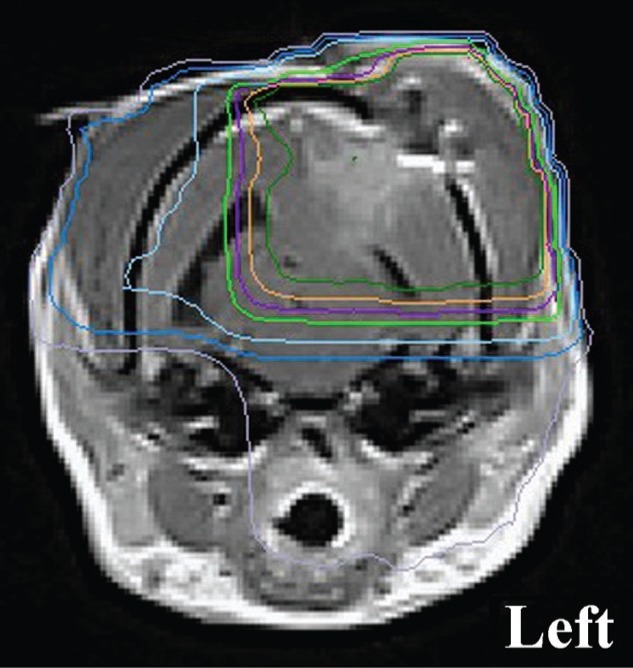

Radiotherapy (RT) Planning

Radiotherapy planning was executed using MRI images obtained from the 48-hour post-N-TIRE MRI (Figure 4). The MRI images were imported into a 3-D computerized treatment planning system (Topslane WiMRT, TGM2, Clearwater, FL, USA). A 3-D treatment plan was created using forward planning and 4 portals. The plan focused on delivering 2.5 Gy per fraction to the area of enhancement including surgical incision plus a 5 mm margin of normal tissue as identified on the T1 + gadolinium transverse images. The tolerance dose for 5% complication in 5 years for irradiation of 1/3 of the brain volume is estimated at 60 Gy (26). Protocols for daily definitive radiation therapy of brain tumors in veterinary medicine are commonly fractionated into 3 Gy per fraction for a total dose of 48 Gy to 54 Gy. The protocol created for this patient used a decreased dose per fraction with the intent to lower the risk of late effects given the volume of brain in the irradiated field. The protocol was 2.5 Gy per fraction, 20 fractions, for a total dose of 50 Gy. Two treatment days had double treatments separated by 6 hours. These double treatment days were to account for days missed due to holidays. X-rays were delivered by a Varian Clinac4® linear accelerator (Palo Alto, California, USA). The patient positioning was confirmed by portal imaging.

Figure 4:

Representative, 48 post N-TIRE therapy MRI image used for radiotherapy planning demonstrating isocenter and isodose distribution. The 100%, 98%, 95%, 90%, 70%, 50% and 30% isodose lines are delineated by the dark green, orange, purple, light green, light blue, dark blue, and gray traces, respectively.

Results

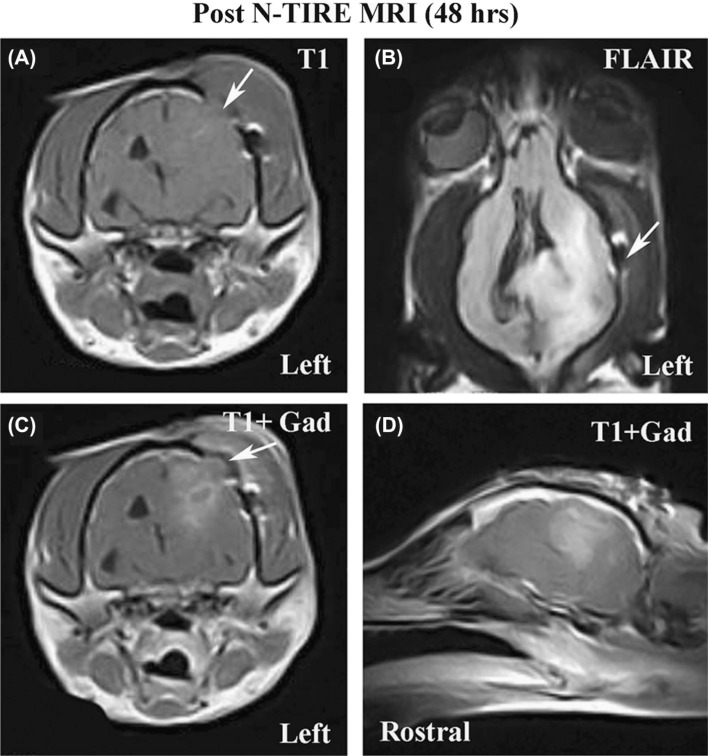

The total operative time for the craniectomy was 106 minutes, of which 12 minutes were required for completion of the N-TIRE therapy. The patient recovered from the N-TIRE craniectomy procedure without complication, and was maintained in the intensive care unit on parenteral opioid analgesics and phenobarbital. Post-operatively, no adverse clinical effects were observed in the patient. An MRI examination performed 48 hours after N-TIRE therapy (Figure 5) revealed a reduction in the size of the neoplasm by approximately 75 percent (Table II), based on volumetric calculations determined from pre-and post-N-TIRE MRI studies using the methods reported in the N-TIRE Treatment Planning section. This suggests that the field strength to kill malignant tissue is significantly lower than for normal tissue, which implies that N-TIRE may have some selectivity in the brain. There was also improvement in the previously noted mesencephalic compression secondary to the transtentorial herniation, as well as a reduction in the amount and extent of perilesional edema.

Figure 5:

MRI examination performed on canine glioma patient 48 hours post-N-TIRE therapy illustrating a reduction in tumor volume. Panels A-D (A-axial T1 pre-contrast; B-Dorsal FLAIR; C-axial T1 post-contrast; D-left parasagittal T1 post-contrast) are homologous images to those provided in panels A-D of Figure 1, and the limited craniectomy defect is visible in panels A, B, and C (arrows).

Table II.

Tumor volumes calculated pre-and 48 hours post N-TIRE ablation from post-contrast T1 MRI.

| Plane | Pre N-TIRE (cm3) | Post N-TIRE (cm3) | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial | 1.15 | 0.32 | 72.2 |

| Sagittal | 1.68 | 0.42 | 75.1 |

| Dorsal | 1.25 | 0.32 | 74.7 |

| Average | 1.36 | 0.35 | 74.2 |

| St.Dev | 0.28 | 0.06 |

By post-operative day 5, the patient’s neurological status improved, with resolution of the previous right sided hemiparesis, and propulsive circling, and improvement in the previously noted aggression. The visual deficits remained static in the right eye. The dog developed aspiration pneumonia, which resolved with antimicrobial and pulmonary toilet therapies. The dog was discharged to the owner on the 10th postoperative day, with instructions to administer phenobarbital and levetiracetam for the symptomatic seizures, and corticosteroids for peritumoral edema.

Sixteen days post-operatively the patient began fractionated radiotherapy, receiving a total of 50 Gy delivered as 20 treatments of 2.5 Gy each, using a 4 MeV linear accelerator (Varian Clinac4® Palo Alto, California, USA). The patient was treated once daily Monday through Friday following induction of general anesthesia. The patient was observed to be mentally brighter, more alert and better oriented by the 5th treatment. After treatment 11, the dog had two seizures that responded to diazepam therapy. Mannitol was incorporated into the anesthesia for the following two treatments and no additional seizures occurred through the rest of the RT treatment. The patient was ataxic and seemed to be less visual for the next few days, but this resolved over the next week. Throughout treatment, despite noticeable improvement, the patient remained aggressive and mildly disoriented.

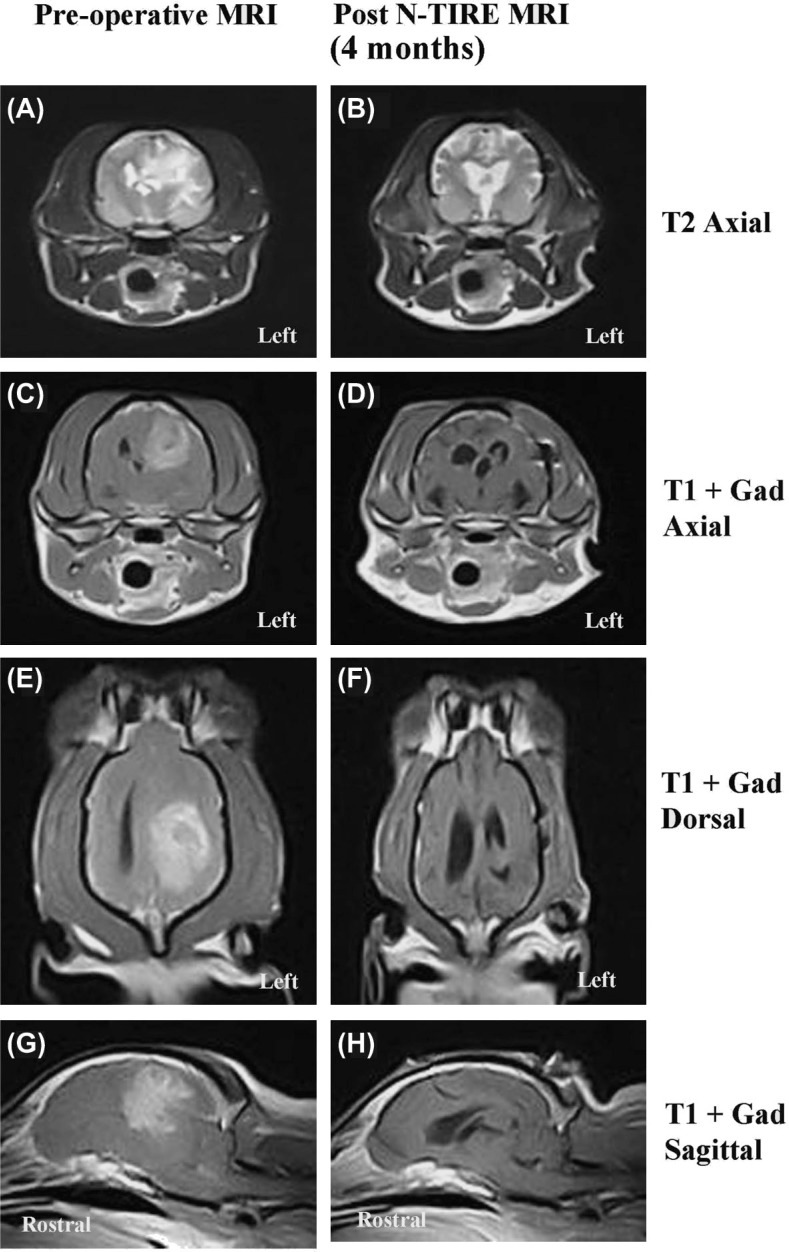

Following completion of radiotherapy, the patient developed evidence of cognitive dysfunction, manifesting as lack of awareness of familiar people and environments, blunted responses to verbal commands, and disturbed sleep-wake cycles. These cognitive deficits, as well as the previously documented visual deficits in the right eye remained static during recheck examinations performed 2 and 4 months following the performance of the N-TIRE treatment, and were not responsive to corticosteroid therapy. The patient was determined to be in complete remission following demonstration of no visible tumor on the 4 month post-N-TIRE MRI examination (Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Comparative pre-operative (left panels A, C, E, G) and 4 month post-N-TIRE (right panels B, D, F, H) MRI examinations. There is no evidence of the previously visualized left cerebral MG evident on the 4 month MRI scan.

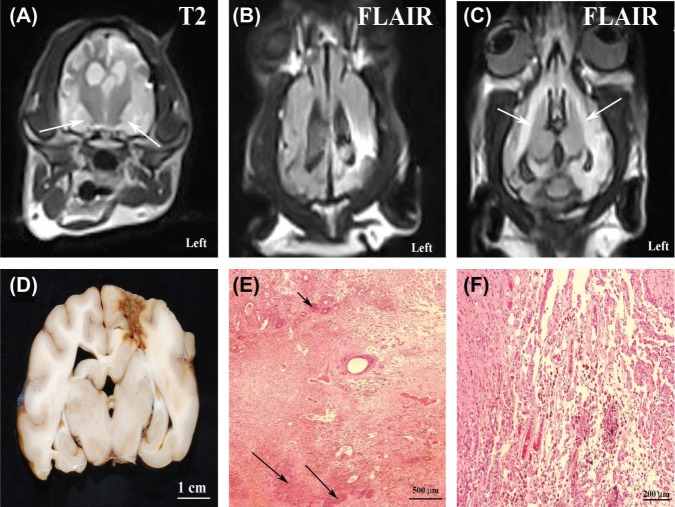

Thirteen days following the documentation of complete remission (approximately 4.5 months post-N-TIRE therapy) the dog was presented for evaluation of an acute deterioration in mentation, proprioceptive ataxia and dysequilibrium, and circling to the left, which were attributed to a multifocal brain disorder. An MRI examination of the brain performed at that time revealed a focal cortical depression in the region of the previous N-TIRE therapy, as well as marked T2 and FLAIR hyperintensity (Figure 7A–C) within the white and gray matter surrounding the previous tumor site, as well as bilaterally symmetric T2 and FLAIR hyperintensites involving hippocampus and pyriform lobes (Figure 7A–B) of the cerebrum, the internal capsule, optic radiations, and corpus callosum (Figure 7C). These lesions were iso-to mildly hypointense on T1 images, and demonstrated mild to moderate heterogeneous enhancement following intravenous administration of gadolinium. The cumulative clinical and MRI findings were considered suggestive of early-delayed radiation encephalopathy, although recurrent MG could not be excluded.

Figure 7:

Axial T2 (A) and dorsal FLAIR (B and C) MRI sequences and post-mortem pathology (D-F) of delayed radiation brain necrosis. Marked T2 (A) and FLAIR (B) signal hyperintensity involving the ipsilateral gray and white matter in region of the previous tumor on the left, as well as bilateral involvement of the pyriform lobes (A; arrows) and white matter of the internal capsule (C; arrows). There is marked signal change evident in the region of the previous tumor when Figure 6B is compared to the homologous FLAIR image (Figure 5F) obtained at the 4 month recheck. (D) A tan focus of necrosis is evident in the left parietal lobe in the region of the previous tumor. (E) Geographic area of coagulative necrosis with dystrophic calcification (arrows; H&E stain). (F) Vascular telangiectasia and hemosiderin laden macrophages within necrotic region of neuropil (H&E stain).

Anti-edema therapy with parenteral corticosteroids, osmotic, and loop diuretics was instituted and continued for 8 days, but the dog’s clinical status continued to deteriorate. The dog was humanely euthanized at the owner’s request by intravenous barbiturate overdosage, with an overall survival in this patient of 149 days after performance of N-TIRE therapy.

Gross post-mortem examination revealed an extensive tanbrown necrotic focus in the left fronto-parietal lobes of the cerebrum (Figure 7D). Microscopically, extensive and geographic regions of coagulative brain necrosis and dystrophic calcification were observed, with the epicenter located in the left parietal lobe in the original location of the MG (Figure 7E). Necrotic regions extended bilaterally into the hippocampus and pyriform lobes, contained hemorrhage, multiple foci of gemistocytic astrocytosis and spheroids, and were commonly infiltrated with hemosiderin laden macrophages (Figure 7F). Multifocal regions of vascular telangiectasias (Figure 7F), vascular hyalinization and microhemorrhage were noted within necrotic areas. White matter pallor and edema were noted to be marked in the epicentric region of necrosis but were also present, although more moderate, rostrally and caudally along the fibers of the internal capsule, optic radiation, and corpus callosum in both the left and right cerebral hemispheres. No evidence of recurrent MG was observed on post-mortem examination. The post-mortem changes were interpreted as consistent with early-delayed radionecrosis of the brain.

Discussion

Despite advances in cancer treatment, MG remains highly resistant to therapy. By nature of their neuroinvasiveness, MG are often not amenable to curative surgery and recur with high frequency (1, 2, 5). Even with aggressive multimodal treatment most patients succumb to the disease within one year. The 5-year survival rate for human patients with GBM is 10% and this statistic has remained nearly unchanged over the last five years (2). Although much less is known regarding the effects of single or multimodal therapies on the survival of dogs with gliomas, the prognosis is considered poor for dogs with MG, with one study reporting a median survival of 9 days for all dogs with non-meningeal origin neoplasms (6). This is the first report of application of N-TIRE for in vivo treatment of spontaneous intracranial MG. Adjunctive radiotherapy, anti-edema treatment, and anticonvulsants were subsequently and concurrently administered to provide comprehensive multimodal therapy. Complete remission was achieved in this canine patient based on serial MRI examinations of the brain and post-mortem examination.

We performed a safe, minimally-invasive N-TIRE procedure at the time of tumor biopsy in this patient based on treatment parameters from the numerical models and preliminary data in normal brain (20–22). Usage of N-TIRE ablation was considered advantageous for this case, as the large tumor volume precluded complete traditional surgical excision without the potential for significant perioperative morbidity associated with brain manipulation. The procedure resulted in rapid improvement of the patient’s neurological signs, which allowed for safe administration of adjunctive post-operative fractionated radiotherapy (RT). We are unable to attribute the clinical improvement entirely to N-TIRE treatment as the patient simultaneously underwent a decompressive craniectomy that provided a reduction in intracranial pressure. However, a limited craniectomy was performed, and two days after the N-TIRE ablation the tumor size was reduced by approximately 75 percent and there was marked reduction in peritumoral edema seen on MRI. Of additional importance is that this patient had evidence of spontaneous, tumor-associated intracerebral hemorrhage on pre-operative MRI sequences. Post-operative MRI showed no additional hemorrhage, further supporting the vascular-sparing nature of N-TIRE treatment (20, 21). It is important to note that there is only one data point between the N-TIRE procedure and RT so it is difficult to evaluate the independent effects of the pulses. N-TIRE induces an immune response in tissues (16, 18) including the brain (20) that could have contributed to the reduction in tumor size and/or complete remission. Future experiments will investigate the effects of N-TIRE therapy alone for the treatment of brain cancer.

N-TIRE is a novel minimally invasive technique to focally ablate undesired tissue using low energy electric pulses (15). These pulses permanently destabilize the membranes of the tumor cells, inducing death without thermal damage in a precise and controllable manner with sub-millimeter resolution (15, 27, 28, 29). The application of N-TIRE requires minimal time and can be performed at the time of surgery, as in this case, or using stereotactic image (i.e. CT or MRI) guidance (24). This is an ideal treatment strategy for many canine brain tumor patients where either tumor volumes are often sufficiently large, as in this case, to preclude safe traditional surgical excision without associated significant perioperative morbidity; or excision is not possible due to the neuroanatomic location of the tumor. We believe that, in addition to the ability to effectively ablate tissue without heating, a major advantage of N-TIRE treatment is the very sharp transition between treated and non-treated tissue, which allows for sparing of sensitive neuroanatomic structures in proximity to the treatment field. Numerical models will be used in subsequent investigations in order to establish the value at which this transition occurs in brain tumor tissue.

Clinical experience and the medical literature indicate that focal ablative or cytoreductive techniques, including N-TIRE, are of limited independent use in the treatment of MG due in part to their inherent locoregional neuroinvasive behavior (1–3). However, as illustrated here, N-TIRE appears to be an additional and viable technique available to the neurosurgeon when a rapid reduction in tumor volume and intracranial hypertension is clinically necessary. In addition, the advantages of N-TIRE as a focal ablative technique may have applications in treatment of benign intracranial tumors, such as meningiomas, particularly those located in anatomic locations that are difficult to approach, where residual microscopic disease following traditional surgery often leads to recurrence.

With N-TIRE there is a region of non-destructive increase in membrane permeability that occurs outside the zone of irreversible tissue ablation (12). The temporary increase in membrane permeability of tissues within this reversibly electroporated penumbra could potentially be used to optimize local delivery of cytotoxic compounds for targeted death of neoplastic cells (30, 31). Microscopic infiltration of tumor cells into the brain parenchyma surrounding gross tumor foci are pathological hallmarks of MG and GBM (1, 5), and a significant limiting factor when employing local therapeutic techniques, including N-TIRE, that are based upon resection or in situ destruction of macroscopic tissue in a biologically sensitive tissue, such as the brain. Therefore, capitalizing on the ability to deliver otherwise impermeant therapeutic agents to cells within the reversibly electroporated penumbra is another tremendous possible advantage of N-TIRE for the treatment of MG and brain disease in general.

Documentation of complete remission following therapy for histopathologically confirmed intracranial glioma is extremely rare (or rarely reported) in veterinary medicine. Unfortunately, although complete remission was documented in this case, clinical and MRI evidence of progressive radiation necrosis developed, and ultimately caused the death of the patient. The ante-mortem MRI and post-mortem pathologic changes noted in this case were similar to those reported in human beings with early-delayed types of radionecrosis of the brain (32, 33). Delayed side effects of radiotherapy are often permanent and develop months to years after the cessation of treatment (33, 34). Cognitive impairment and radionecrosis of the brain are not commonly recognized in canine patients after RT with doses and fractions similar to those prescribed in the patient described here (personal communication with Dr. Nancy Gustafson, February 2010). Compared to humans, there is a paucity of published data available describing the incidence of or risk factors associated with the development of delayed radiation encephalopathies in dogs with spontaneous brain tumors. The incidence of radiation necrosis in adult humans after conventional doses used for brain tumor treatment ranges from 5 to 24%, but this complication is considered rare when cumulative doses of standard fractionated radiation less than 50-60 Gy are delivered to the brain (32, 33). Several recognized risk factors associated with the development of post-RT associated neurological complications in humans were present in the patient reported here including advanced age, large volume of brain irradiated, and >2 Gy fractions administered (34–36). However, non-necrotizing radiation encephalopathies manifesting as neurobehavioral disorders are more common than radiation induced necrosis, and may occur at doses as low as 20 Gy in adult humans (34, 35). Given that progressive radionecrosis of the brain resulted in the death of this patient, we must recognize the possibility that N-TIRE therapy may have some radiosensitizing or other synergistic interaction with external beam RT. Although this may enhance therapeutic effectiveness of RT, it could also predispose to the development of delayed radiation complications in patients with brain disease if administered using current and conventional dosing regimens.

In conclusion, we have shown that treatment of canine MG with N-TIRE is rapid, minimally invasive, and effective for ablation of pathologically heterogeneous neoplastic brain tissue without exacerbating intracerebral hemorrhage. In addition, this work demonstrates that N-TIRE can be successfully planned and executed with clinical procedures routinely used during evaluation of the neurosurgical patient. In our patient, N-TIRE ablation was an integral part of a comprehensive multimodality therapeutic regimen that resulted in complete remission from the MG. Our preliminary results justify continued research and development of N-TIRE therapy for the ablation of unwanted brain tissue, and highlight the need for investigations into possible advantageous or deleterious interactions of N-TIRE with other anticancer therapies commonly used in the management of brain tumor patients, such as radio-and chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Coulter Foundation and the Maria Garst Memorial Fund for Cancer Research. The authors would also like to thank AngioDynamics® Inc. for loan of their equipment and for technical support of this study, Josh Tan for software help, Nadia Yungk and Drs. Karen Inzana, Blaise Burke, and Ellen Binder for assistance with patient management.

Abbreviations:

- CT:

Computed Tomography

- Gad:

Gadolinium

- GBM:

Glioblastoma Multiforme

- IRE:

Irreversible Electroporation

- MG:

Malignant Glioma

- MRI:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- N-TIRE:

Non-thermal Irreversible Electroporation

- RT:

Radiotherapy.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Davalos, Garcia, Rossmeisl and Robertson have pending patents in the area of irreversible electroporation. In addition, Davalos consults in the area of numerical modeling of electric fields in tissue. The other authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. La Rocca R. V., Mehdorn H. M. Localized BCNU chemotherapy and the multimodal management of malignant glioma. Curr Med Res Opin 25, 149–60, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stupp R., Mason W. P., van den Bent M. J., Weller M., Fisher B., Taphoorn M. J., Belanger K., Brandes A. A., Marosi C., Bogdahn U., Curschmann J., Janzer R. C., Ludwin S. K., Gorlia T., Allgeier A., Lacombe D., Cairncross J. G., Eisenhauer E., Mirimanoff R. O. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352, 987–96, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rossmeisl J. H., Duncan R. B., Huckle W. R., Troy G. C. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in tumors and plasma from dogs with primary intracranial neoplasms. Am J Vet Res 68, 1239–45, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dickinson P. J., Roberts B. N., Higgins R. J., Leutenegger C. M., Bollen A. W., Kass P. H., LeCouteur R. A. Expression of receptor tyrosine kinases VEGFR-1 (FLT-1), VEGFR-2 (KDR), EGFR-1, PDGFRa and c-Met in canine primary brain tumours. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology 4, 132–40, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stoica G., Kim H. T., Hall D. G., Coates J. R. Morphology, immunohistochemistry, and genetic alterations in dog astrocytomas. Vet Pathol 41, 10–9, (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heidner G. L., Kornegay J. N., Page R. L., Dodge R. K., Thrall D. E. Analysis of survival in a retrospective study of 86 dogs with brain tumors. J Vet Intern Med 5, 219–26, (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tacke J. Thermal therapies in interventional MR imaging. Cryotherapy. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 11, 759–65, (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Atsumi H., Matsumae M., Kaneda M., Muro I., Mamata Y., Komiya T., Tsugu A., Tsugane R. Novel laser system and laser irradiation method reduced the risk of carbonization during laser interstitial thermotherapy: assessed by MR temperature measurement. Lasers Surg Med 29, 108–17, (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cosman E. R., Nashold B. S., Bedenbaugh P. Stereotactic radiofrequency lesion making. Appl Neurophysiol 46, 160–6, (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weaver J. C., Chizmadzhev Y. A. Theory of electroporation: a review. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg 41, 135–60, (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weaver J. C. Electroporation: a general phenomenon for manipulating cells and tissues. J Cell Biochem 51, 426–35, (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davalos R. V., Mir L. M., Rubinsky B. Tissue ablation with irreversible electroporation. Ann Biomed Eng 33, 223–31, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubinsky B. Irreversible Electroporation in Medicine. Tecnol Cancer Res Treat 6, 255–259, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maor E., Ivorra A., Rubinsky B. Non thermal irreversible electroporation: novel technology for vascular smooth muscle cells ablation. PLoS ONE 4, e4757, (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Al-Sakere B., Andre F., Bernat C., Connault E., Opolon P., Davalos R. V., Rubinsky B., Mir L. M. Tumor ablation with irreversible electroporation. PLoS ONE 2, e1135, (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee E. W., Loh C. T., Kee S. T. Imaging guided percutaneous irreversible electroporation: ultrasound and immunohistological correlation. Technol Cancer Res Treat 6, 287–293, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubinsky B., Onik G., Mikus P. Irreversible electroporation: a new ablation modality-clinical implications. Technol Cancer Res Treat 6, 37–48, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Onik G., Mikus P., Rubinsky B. Irreversible electroporation: implications for prostate ablation. Technol Cancer Res Treat 6, 295–300, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maor E., Rubinsky B. Endovascular nonthermal irreversible electroporation: a finite element analysis. J Biomech Eng 132, 031008, (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ellis T. L., Garcia P. A., Rossmeisl J. H., Henao-Guerrero N., Robertson J., Davalos R. V. Nonthermal irreversible electroporation for intracranial surgical applications. J Neurosurg, (in print), (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21. Garcia P. A., Rossmeisl J. H., Robertson J., Ellis T. L., Davalos R. V. Pilot study of irreversible electroporation for intracranial surgery. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 1, 6513–6, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garcia P. A., Rossmeisl J. H., Neal R. E., II, Ellis T. L., Olson J., Henao-Guerrero N., Robertson J., Davalos R. V. Intracranial Non-Thermal Irreversible Electroporation: In vivo analysis. J Membr Biol 236, 127–36, (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sel D., Cukjati D., Batiuskaite D., Slivnik T., Mir L. M., Miklavcic D. Sequential finite element model of tissue electropermeabilization. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 52, 816–27, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia P. A., Neal R. E. I., Rossmeisl J. H., Davalos R. V. Non-Thermal Irreversible Electroporation for Deep Intracranial Disorders. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 1, (in print), (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jaffe R. The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy: Recommendations for Treatment, Training, and Privileging: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association, 2nd ed. Am J Psychiatry 159, 331, (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hall E. J. Radiobiology for the Radiologist 5th ed, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, MD: (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Al-Sakere B., Bernat C., Andre F., Connault E., Opolon P., Davalos R. V., Mir L. M. A study of the immunological response to tumor ablation with irreversible electroporation. Techol Cancer Res Treat 6, 301–05, (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davalos R. V., Rubinsky B. Temperature considerations during irreversible electroporation. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 51, 5617–22, (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Granot Y., Ivorra A., Maor E., Rubinsky B. In vivo imaging of irreversible electroporation by means of electrical impedance tomography. Phys Med Biol 54, 4927–43, (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glass L. F., Pepine M. L., Fenske N. A., Jaroszeski M., Reintgen D. S., Heller R. Bleomycin-mediated electrochemotherapy of metastatic melanoma. Arch Dermatol 132, 1353–7, (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heller R., Gilbert R., Jaroszeski M. J. Clinical applications of electrochemotherapy. Advanced drug delivery reviews 35, 119–29, (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burger P. C., Mahley M. S., Jr., Dudka L., Vogel F. S. The morphologic effects of radiation administered therapeutically for intracranial gliomas: a postmortem study of 25 cases. Cancer 44, 1256–72, (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kumar A. J., Leeds N. E., Fuller G. N., Van Tassel P., Maor M. H., Sawaya R. E., Levin V. A. Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy-and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology 217, 377–84, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shaw E. G., Robbins M. E. The management of radiation-induced brain injury. Cancer Treat Res 128, 7–22, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crossen J. R., Garwood D., Glatstein E., Neuwelt E. A. Neurobehavioral sequelae of cranial irradiation in adults: a review of radiation-induced encephalopathy. J Clin Oncol 12, 627–42, (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Asai A., Kawamoto K. [Radiation-induced brain injury]. Brain Nerve 60, 123–9, (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]