Abstract

Six adult dairy cows clinically diagnosed as hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS) were the subjects of this study. The involved intestinal lesions were fixed in formalin and examined macroscopically and histopathologically. Pathological examinations revealed large intramural hematomas with necrotic foci, resulting in luminal obstruction. The mucosal layer in the lesions was detached from the intestinal wall, and there were no hemorrhagic changes in the lumen. The intramural hematomas were sometimes covered with histologically intact mucosal layer. These pathological findings were not consistent with those of “intraluminal blood clots” reported previously. Gram-positive and anti-Clostridium antibody-positive short bacilli were found in hemorrhagic necrotic areas. However, the exact relationship between Clostridium spp. observed in the lesions and HBS remains unclear, because this bacterium is a normal inhabitant in cattle.

Keywords: Clostridium, HBS, hemorrhagic bowel syndrome, intramural hematoma

Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome (HBS), also known as jejunal hemorrhagic syndrome [10] or jejunal hematoma [3], is a relatively new and increasing disorder reported as sporadic, acute and necrohemorrhagic enteritis with high fatality rate in dairy and beef cattle. Clinical signs of the disease are decreased feed intake, depression, decreased milk production, dehydration, abdominal distension and dark clotted blood in the feces [1, 2, 4, 7, 10]. Clostridium perfringens type A [1,2,3, 6,7,8,9] and Aspergillus fumigatus [11] have been suggested as the potential cause, because these organisms have been isolated from the lesions of clinical cases. However, obvious causes of the disease are still not known. In laparotomy of the syndrome, characteristic hemorrhagic segmental lesions in the small intestine were observed, resulting in obstruction of the luminal passage at the lesion. The lesion has been reported as intraluminal blood clots [1, 2, 7, 9] or the obstructing blood clots [10]. In some reports, medical and surgical treatments as manual massage of the blood clots or enterectomy have been performed, but the survival rate for these treatments has been very low in spite of eliminating obstructions in the intestines [2, 7, 10]. Therefore, whether or not the pathological condition of the syndrome is due to real obstructions in the intestine has not been confirmed. The purpose of this study was research for further details of morphological changes in the lesions of HBS that had been reported as intraluminal blood clots in some papers.

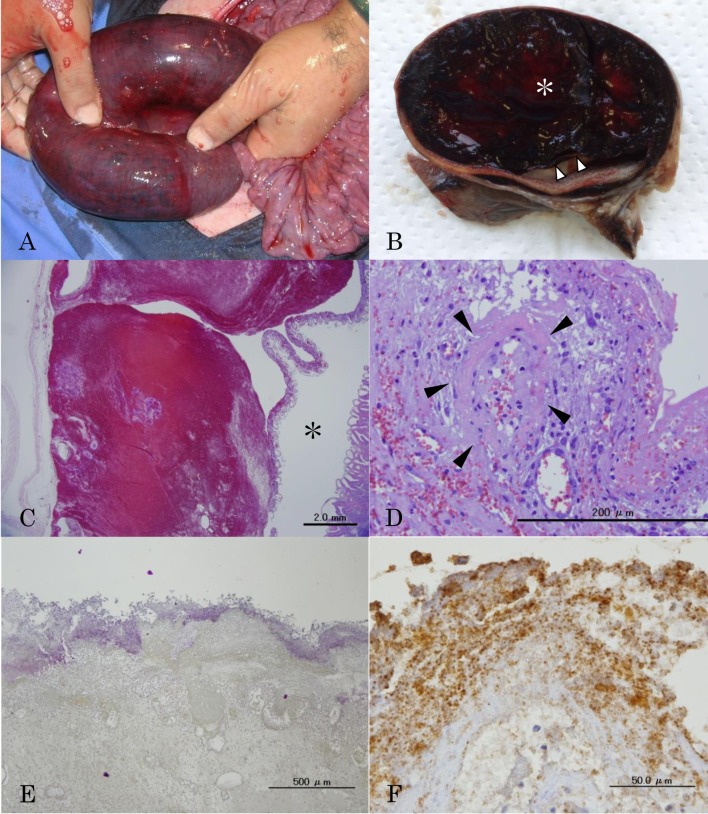

Laparotomy was performed on 6 cases of HBS, because of clinical signs and diagnosis based on the detection of characteristic segmental hemorrhage in the small intestine (Fig. 1A). All cases were Holstein Friesian dairy cows that underwent laparotomy between December 2009 and November 2013. These cows were 40 to 71 months old and were multiparous. The days after parturition varied from 97 to 138 days. All cows were admitted to our clinic within a day after onset of clinical signs, and laparotomies were performed in the operating room (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

A. Characteristic dark-red bloody lesion in the intestine of HBS, resulting in luminal obstruction. B. Transverse section of the intestinal lesion after formalin fixation. Intramural hematoma (asterisk) is found. The mucosa is detached from the intestinal wall (arrowheads). C. Intramural hematoma and lumen (asterisk). Massive hemorrhage is observed in the submucosa and lamina propria. The mucosal layer is almost intact. These are no hemorrhagic lesions in the lumen. HE stain, Bar=2.0 mm. D. Fibrinoid necrosis of the vascular wall (arrowheads) in the submucosa of the lesion. HE stain, Bar=200 µm. E and F. Gram positive and anti-Clostridium antibody positive short bacilli in surface of necrotic mucosa. Gram stain, Bar=500 µm (E) and Immunohistochemistry, Bar=50 µm (F).

Table 1. Clinical history of six cases with hemorrhage bowel syndrome.

| Case number |

Date of onset | Age (months) |

Breed | Sex | Days post calving |

Survival period after onset (days) |

Outcome | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2009/12/7 | 41 | Holstein Friesian | Female | 97 | 1 | Euthanasia | |

| 2 | 2010/1/14 | 54 | Holstein Friesian | Female | 138 | 1 | Euthanasia | |

| 3 | 2010/4/20 | 33 | Holstein Friesian | Female | 95 | 2 | Dead | Enterectomy |

| 4 | 2010/6/8 | 54 | Holstein Friesian | Female | 109 | 2 | Dead | Manual massage |

| 5 | 2013/5/27 | 40 | Holstein Friesian | Female | 107 | 0 | Euthanasia | |

| 6 | 2013/11/20 | 71 | Holstein Friesian | Female | 114 | 1 | Dead | Enterectomy |

All cows were given fluids and calcium salts by intravenous injection before and during admission in the operating room. All cows were given antibiotic by intramuscular injection. Procaine penicillin G was administered to cases 1, 2, 4 and 6. Cefazolin was administered to cases 3 and 5. Four cases were given flunixin meglumine, and one case was given dexamethasone by intravenous injection. Laparotomy was performed in right lateral recumbent position with local infiltration anesthesia by lidocaine in all cases.

Manual massage was performed in the first surgery of case 4. In this case, the first surgery was finished, but the cow relapsed to HBS in one day after the first surgery. Enterectomy was performed to the newly segmental hemorrhagic lesion in the second laparotomy, but the cow died within one day after the second surgery. Three out of 6 cases were euthanized, because of the burst of the lesions under surgery. Enterectomy was performed in the other two cases, but they died within 2 days after surgery. Under laparotomy, the segmental hemorrhagic lesions were removed and fixed immediately in 10% neutral buffered formalin in all cases.

After 1 week of formalin fixation, the intestinal tissues were embedded in paraffin wax. Transverse sections which included the interface between the hemorrhage and nonhemorrhagic portions of the intestines were cut at 5 µm and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and the Gram stain. Selected sections were studied further by an immunostaining method using anti-Clostridium antibody.

Gross examination revealed large intramural hematomas in the intestinal lesions. The mucosa was detached from the intestinal wall by the hematoma, and the intestinal lumen was severely obstructed (Fig. 1B). Part of the detached mucosa was thinned and necrotic. Histopathological examinations revealed the mucosa was compressed and detached from the submucosa by the massive hemorrhage localized in the submucosa (Fig. 1C). Hemorrhage into the lumen was not found in some lesions in spite of submucosal massive hemorrhage. Mucosal layers in these lesions were histologically intact. Many thrombi and severe infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils and lymphocytes were found in the submucosa and lamina propria. Hemorrhagic foci were also found in serosa and mesenteric adipose tissue. The demarcation line between affected and intact areas was clear by detached mucosa. Fibroid necrosis of the vascular walls was found in all layers or parts of the submucosa adjacent to the hematoma (Fig. 1D). Partial lacteal dilatation and severe lymphocytes infiltration were also observed in the relatively normal mucosa. Numerous Gram-positive short bacilli and anti-Clostridium antibody-positive staining were found in the hemorrhagic or necrotic areas of the mucosa, submucosa and lamina propria (Fig. 1E).

The condition of the lesions in HBS was described as “intraluminal blood clots” or “obstructing blood clots” in many reports [1, 2, 7, 9]. We, as well as other clinical veterinarians, have tried to treat and operate on HBS based on the conditions reported. Namely, the object of manual massage for the lesion was to crush intraluminal blood clots and to eliminate the obstruction in the lumen of the intestine. However, in all cases of this report, the main hemorrhagic area was not found in the intraluminal, but in the intramural area. Massive hemorrhage was found in the submucosa, and the lesion was covered with almost intact mucosal layer. In addition, fibrinoid necrosis of the vascular wall was found in the regions adjacent to the hemorrhagic areas. These findings might suggest that the primary cause of HBS was hemorrhage by vascular damage in the submucosa. Therefore, the characteristic dark-red bloody intestinal lesions in HBS observed during laparotomy were thought to be mainly intramural hematomas under the serosa, not intraluminal blood clots. The disturbance of passage or the stricture in the intestine of HBS was caused by large intramural hematomas, and not by intraluminal blood clots. The dark clotted blood in the feces is one of the clinical signs of HBS [1, 2, 7, 9, 10], which is considered to be the result of intramural hematoma flowing into the lumen of posterior intestine by crushing the mucosa. A cure is difficult by a manual massage of the lesion in the case of intramural hematoma. This might explain the low recovery rate of HBS in spite of eliminating obstructions in the intestine by surgery. Although demarcation line between affected area and normal area was clear, the cases of HBS operated by enterectomy did not survive in this study. Therefore, removal of the intramural hematoma by enterectomy might be unsufficient for survival of cattle of HBS. Other factors that influence prognosis of HBS were still unknown. On the other hand, Peek et al. [10] reported that some cases of HBS were cured by only a manual massage to the lesions. Therefore, HBS had various conditions in the intestines ranged from irreversibility that was poor prognosis to mild changes that could be treated effectively by only manual massage. It might be necessary to judge whether the surgical procedure should be selected as manual massage, enterectomy or poor prognosis based on the condition of the lesion in each HBS case.

Clostridium might be involved in the pathogenesis of HBS [3, 7,8,9], because anti-Clostridium antibody-positive short bacilli were found in the mucosal and submucosal necrotic areas. However, Clostridium is a normal inhabitant in the intestine of cattle [12], and vaccination for Clostridium was not particularly effective in preventing HBS [5]. Therefore, the relationship between the pathogenesis of HBS and this bacterium is not clear. In a previous survey, increased consumption of a high-energy diet had been suggested as an important risk factor [5], but the definitive factors for the pathogenesis of HBS remain to be determined.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abutarbush S. M., Carmalt J. L., Wilson D. G., O’Conneor B. P., Clark E. G., Naylor J. M.2004. Jejunal hemorrhage syndrome in 2 Canadian beef cows. Can. Vet. J. 45: 48–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abutarbush S. M., Radostits O. M.2005. Jejunal hemorrhage syndrome in dairy and beef cattle: 11 cases (2001 to 2003). Can. Vet. J. 46: 711–715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adaska J. M., Aly S. S., Moeller R. B., Blanchard P. C., Anderson M., Kinde H., UzalJejunal F.2014. Jejunal hematoma in cattle: a retrospective case analysis. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 26: 96–103. doi: 10.1177/1040638713517696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson B. C.1991. ‘Point source’ haemorrhages in cows. Vet. Rec. 128: 619–620. doi: 10.1136/vr.128.26.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berghaus R. D., McCluskey B. J., Callan R. J.2005. Risk factors associated with hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 226: 1700–1706. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.226.1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceci L., Paradies P., Sasanelli M., de Caprariis D., Guarda F., Capucchio M. T., Carelli G.2006. Haemorrhagic Bowel Syndrome in dairy cattle: possible role of Clostridium perfringens Type A in the disease complex. J. Vet. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 53: 518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dennison A. C., VanMetre D. C., Callan R. J., Dinsmore P., Mason G. L., Ellis R. P.2002. Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome in dairy cattle: 22 cases (1997–2000). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 221: 686–689. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.221.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennison A. C., Van Metre D. C., Morley P. S., Callan R. J., Plampin E. C., Ellis R. P.2005. Comparison of the odds of isolation, genotypes, and in vivo production of major toxins by Clostridium perfringens obtained from the gastrointestinal tract of dairy cows with hemorrhagic bowel syndrome or left-displaced abomasum. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 227: 132–138. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxie M. G.2007. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 5th ed., Saunders Elsevier, London. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peek S. F., Santschi E. M., Livesey M. A., Prichard M. A., McGuirk S. M., Brounts S. H., Edwards R. B.2009. Surgical findings and outcome for dairy cattle with jejunal hemorrhage syndrome: 31 cases (2000–2007). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 234: 1308–1312. doi: 10.2460/javma.234.10.1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puntenney S. B., Wang Y., Forsberg N. E.2003. Mycotic infections in livestock: recent insights and studies on etiology, diagnostics and prevention of hemorrhagic bowel syndrome. pp.49–62 In: Southwest Animal Nutrition and Management Conference Proceedings.

- 12.Songer J. G.1999. Clostridium perfringens Type A infection in cattle. pp. 40–44. In: Annual Convention American Association of Bovine Practitioner Proceedings.