Abstract

In the present study we have synthesized a novel amphiphilic porphyrin and its Ag(II) complex through modification of water-soluble porphyrinic structure in order to increase its lipophilicity and in turn pharmacological potency. New cationic non-symmetrical meso-substituted porphyrins were characterized by UV–visible, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), 1H NMR techniques, lipophilicity (thin-layer chromatographic retention factor, Rf), and elemental analysis. The key toxicological profile (i.e. cytotoxicity and cell line-(cancer type-) specificity; genotoxicity; cell cycle effects) of amphiphilic Ag porphyrin was studied in human normal and cancer cell lines of various tissue origins and compared with its water-soluble analog. Structural modification of the molecule from water-soluble to amphiphilic resulted in a certain increase in the cytotoxicity and a decrease in cell line-specificity. Importantly, Ag(II) porphyrin showed less toxicity to normal cells and greater toxicity to their cancerous counterparts as compared to cisplatin. The amphiphilic complex was also not genotoxic and demonstrated a slight cytostatic effect via the cell cycle delay due to the prolongation of S-phase. As expected, the performed structural modification affected also the photocytotoxic activity of metal-free amphiphilic porphyrin. The ligand tested on cancer cell line revealed a dramatic (more than 70-fold) amplification of its phototoxic activity as compared to its water-soluble tetracationic metal-free analog. The compound combines low dark cytotoxicity with 5 fold stronger phototoxicity relative to Chlorin e6 and could be considered as a potential photosensitizer for further development in photodynamic therapy.

Keywords: Ag porphyrin, Amphiphilic porphyrin, Anticancer activity, Genotoxicity, Cytotoxicity, Photosensitizer

1. Introduction

Porphyrins are known to preferentially accumulate in tumor tissue, a highly desirable feature for anticancer therapy [1–5]. Many photosensitizers (PSs) have been created based on numerous structural modifications plausible on porphyrinic macrocycle and successfully applied in photodynamic therapy of cancer [4–8]. Due to their high phototoxicity and tumor targeting ability, porphyrins were linked to various anti-cancer moieties to selectively transport and destroy the tumor tissue both with and without light applications [9–14]. At present, the search for potent chemotherapeutics (agents used without light application) among this class of compounds became also an area of vigorous exploration. In fact, for the last decade, anticancer activity of a series of metalloporphyrins has been a subject of several research groups’ studies. A series of Au(III) tetraarylporphyrins were synthesized and tested as potential chemotherapeutical agents for cancer treatment [15–17]. They exerted higher potency than cisplatin in killing human cancer cells [18], which led the authors to proceed successfully with in vivo studies [15]. Anticancer activity of water-soluble cationic Mn(III) complexes of meso-tetrakis (2-N-substituted pyridyl) porphyrins alone or as a part of combinatorial treatment was demonstrated in a series of in vivo cancer models such as the skin, brain, breast and prostate [19–23]. Two types of mechanisms, i.e. pro- and/or antioxidative, have been suggested to be possibly involved in the anticancer action of Mn(III) porphyrins, which were initially developed as superoxide dismutase mimics [23–27]. Kawakami’s group have reported that Fe(III) complexes of meso-substituted cationic porphyrins are also promising anticancer agents able to selectively destroy cancer cells [28]. They have demonstrated that iron porphyrin uses intracellular high level of superoxide anion as a target molecule to induce selective cancer cell death [29–31].

Lately we have shown that Ag(II) complexes of water-soluble cationic meso-tetrakis(N-substitutedpyridyl)porphyrins could also be considered as a potential new class of chemotherapeutic agents [32–35]. A number of water-soluble, meso-substituted cationic pyridylporphyrins and their metallocomplexes bearing various central metal atoms (Ag, Zn, Co, and Fe) in porphine ring and functional groups (allyl, oxyethyl, butyl, and methallyl) at the nitrogen atom in pyridine ring were synthesized and screened in vitro as potential anticancer agents [32–35]. The AgTAll4PyP, which includes Ag as a central metal atom and allyl functional group at the periphery was identified as the most cytotoxic metalloporphyrin (Fig. 1). Synthesized porphyrins and metallocomplexes were tested also on their photodynamic activities. The most phototoxic porphyrin was revealed to be the allyl group containing free-base porphyrin, H2TAll4PyP (Fig. 1) [35].

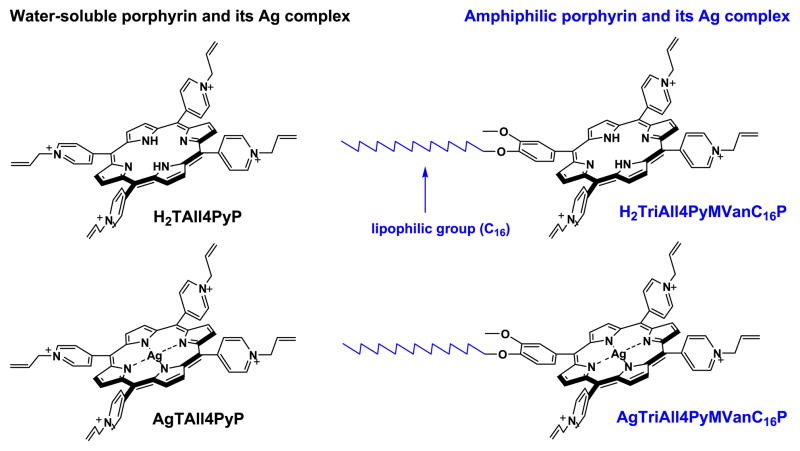

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of porphyrins (H2TAll4PyP and H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P) and their Ag(II) complexes (AgTAll4PyP and AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P). Due to the insertion of long alkyl chain and loss of a positive charge (phenyl replacing quaternized pyridyl) the porphyrin synthesized became more lipophilic, thus presumably more bioavailable for the cells.

In the present work, aiming to improve the bioavailability, and in turn anticancer (dark and photo-induced) activity of (metallo) porphyrins, we have designed and synthesized a new amphiphilic type of porphyrin, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P and its Ag(II) complex, AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (Fig. 1) via incorporation of long hydrophobic chain into the meso-position of the porphine ring. The combination of hydrophobic and hydrophilic substituents in the porphyrinic structure was documented earlier to improve compounds’ pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties [5,8,36–39]. The insertion of polar substituents into the macrocycle carrying also hydrophobic moieties makes the molecule an amphiphilic species with sufficient water-solubility to allow its systemic administration in vivo, while retaining high tendency to penetrate through a lipid barrier of cytoplasmic membrane of tumor cells and localize at intracellular compartments [5,36]. In addition, the presence of electrically charged functional groups generates electrostatic repulsion, thereby preventing the formation of aggregates which otherwise would drastically modify the porphyrin bioactivity [40]. Hence, due to the introduction of long alkyl chain and the loss of single positive charge (Fig. 1), synthesized porphyrin H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P and its Ag(II) complex, AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P, gain in the lipophilicity as compared to their tetracationic analogs. In turn, purposed structural variations intensify their phototoxicity (for free-base porphyrin) and chemotherapeutic (for Ag(II) complex) activity. The activities of new porphyrins (H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P and AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P) as potential photosensitizing and chemotherapeutic agents were studied and compared with those of tetracationic porphyrins (H2TAll4PyP and AgTAll4PyP) (Fig. 1).

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals and equipments

Pyrrole, 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde (vanillin), 4- pyridinecarboxaldehyde (97%), AgNO3, 3-bromopropene (allylbromide), acetonitrile, heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA), and N,N-dimethylformamide anhydrous of 99.8% purity were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GMBH, Germany. The chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin was obtained from EBEWE Pharma Ges.m.b.H.Nfg.KGA-4866 Unterach, Austria, and Chlorin e6 was kindly provided by Dr. Gyulkhandanyan (Institute of Biochemistry, NAS RA). All chemicals were used as received without further purification. H2TAll4PyP and its Ag complex were synthesized according to the methods earlier published in [35].

The structure and purity of compounds synthesized were determined by NMR, electronic absorption spectroscopy, elemental analysis and thin-layer chromatography. Analytical thin-layer chromatography was performed on silica-coated plastic plates (1:1:8 = KNO3-saturated H2O: H2O:CH3CN (v/v) mobile phase is used for the water soluble and amphiphilic (metallo)porphyrins and chloroform:methanol system for organosoluble porphyrins). Preparative separation was performed by column chromatography on alumina (Brockmann Grade II). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a spectrometer “Mercury Varian 300” (solvents—deuterated chloroform and dimethyl sulfoxide). The electronic spectra of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins were recorded in the wavelength range of 350–800 nm on a “Perkin-Elmer Lambda 800” double-beam UV–visible spectrophotometer (solvents — distilled water and chloroform). The absorption coefficients of bands were determined in 10−4– 10−6 M porphyrin solutions by the Beer–Lambert law.

2.2. Synthesis of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins

2.2.1. 5-Mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-tri(4′-N-allylpyridyl) porphine tribromide (H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P)

The synthesis of H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P was performed by boiling a mixture of H2Tri4PyMVanC16P (50 mg, 0.056 mmol) and 3-bromopropene (1.0 mL, 11.6 mmol) in N,N-dimethylformamide (6 mL) at reflux. The experimental procedures of the synthesis of H2Tri4PyMVanC16P and its related isomers (H2TVanC16P, H2T4PyP, H2M4PyTriVanC16P, trans-H2Di4PyDiVanC16P, and cis-H2Di4Py DiVanC16P), along with their physicochemical characteristics (UV–vis, 1H NMR and elemental analyses data), are given in the Supplementary Material. The completion of the reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (1:1:8 = KNO3-saturated H2O:H2O:CH3CN (v/v) as a mobile phase). After 1.5 h the reaction was stopped, and the solvent was evaporated under a reduced pressure till the minimal volume. The residue was crystallized by acetone, filtered and washed in turn with isopropanol, acetone, petroleum ether and acetone. Yield 70 mg (99.3%). H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P porphyrin (C67H76Br3N7O2); 1H NMR (300 MHz; d6-DMSO; Me4Si) δH, ppm: −2.97 (2H, s, pyrrole-NH); 0.83 (3H, m, –C15H30CH3); 1.17–1.39 (22H, m, –CH2–); 1.45 (2H, m, –CH2–); 1.58 (2H, m, –CH2–); 1.92 (2H, m, –CH2–); 3.90 (3H, s, –OCH3); 4.27 (2H, t, J = 6.4, –OCH2–); 5.66 (6H, d, 3J = 6.3, –CH2–CH=CH2); 5.71 (3H, d, 3J = 10.2, –CH=CH2); 5.82 (3H, d, 3J = 17.0, –CH=CH2); 6.51 (3H, ddt, J =17.0, 3J = 10.2, 3J = 6.3, –CH=CH2); 7.44 (1H, d, J = 8.1, phenyl-5-H); 7.72 (1H, dd, J = 8.1, J = 2.0, phenyl-6-H); 7.84 (1H, d, J = 2.0, phenyl-2-H); 9.00–9.06 (6H, m, pyridine-2,2′-H); 9.07–9.13 (4H, m, β-pyrrole-3,3′-H); 9.19 (4H, s, β-pyrrole-3,3′-H); 9.49–9.54 (6H, m, pyridine-3,3′-H). Elemental analysis: Anal. calcd. for H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P·4H2O (C67H84Br3N7O6): C, 60.82; H, 6.40; N, 7.41%. Found: C, 60.47; H, 6.54; N, 7.51%. UV–vis (H2O): λmax, nm (log ε) 429.0 (5.29), 523.5 (4.17), 561 (3.73), 589 (3.71), 648 (3.4). ESI-MS data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) data for newly synthesized porphyrins, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P and its Ag complex.

| Speciesa | m/z [found (calculated)]

|

|

|---|---|---|

| H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P | AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P | |

| [P]3+ / | 3 337.0 (336.9) | 372.1 (371.8) |

| [P3+ − H+]2+ / 2 | 504.8 (504.8) | 558.2 (557.8) |

| [P3+ + HFBA−]2+ / 2 | 611.8 (611.8) | 664.7 (664.2) |

~1 μM solutions were applied prepared in 1:1 v/v acetonitrile:H2O (containing 0.01% v/v heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA)) mixture.

2.2.2. 5-Mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-tri(4′-N-allylpyridyl) porphinato Ag(II) trinitrate (AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P)

To a solution of H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P (70 mg, 0.056 mmol) in methanol (6 mL) AgNO3 (60 mg, 0.353 mmol) dissolved in ethanol (5 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at a boiling temperature for 0.5 h. Another portion of AgNO3 (100 mg, 0.588 mmol) dissolved in ethanol (5 mL) was added and boiling was continued for 1.5 h. At the end of the reaction that was determined by thin-layer chromatography (1:1:8 = KNO3-saturated H2O:H2O:CH3CN (v/v) as a mobile phase), UV–vis spectrometry and fluorescence measurements (ligand is fluorescence) solvent was evaporated to the minimum volume. Hot solution of product was filtered and washed by methanol till the solution become colorless. Then the filtrate was added with a little amount of ethanol and evaporated to remove methanol completely. After cooling of the solution the formed porphyrin precipitate was filtered and washed successively with diethylether, acetone, and diethylether. Yield 70 mg (96%). Elemental analysis: Anal. calcd. for AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P·6H2O (C67H86AgN10O17): C, 57.02; H, 6.14; N, 9.92%. Found: C, 56.88; H, 6.42; N, 10.33%. UV–vis (H2O): λmax, nm (log ε) 435.0 (5.19), 550.5 (3.99). ESI-MS data are presented in Table 1.

2.3. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS)

Electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analyses were performed on an Applied Biosystems MDS Sciex 5500 Q Trap LC/MS/MS spectrometer at Duke Cancer Institute PK/PD Core Laboratory as described elsewhere [41–43]. Briefly, samples of ~1 μM concentrations, prepared in acetonitrile:H2O mixture (1:1, v/v) containing 0.01% v/v heptafluorobutyric acid, were infused for 1 min at 10 μL/min into the spectrometer (curtain gas 20 V, ion spray voltage 3500 V, ion source 30 V, t = 300 °C, declustering potential 20 V, entrance potential 1 V, collision energy 5 V, gas N2). Data are summarized in Table 1.

2.4. Thin-layer chromatography

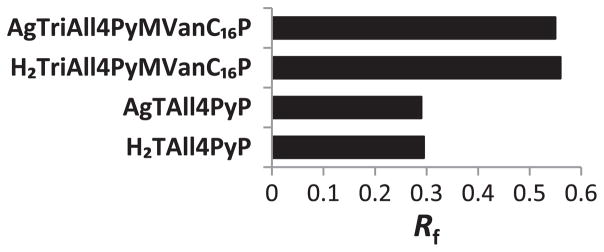

The thin-layer chromatographic retention factor, Rf, (compound path/solvent path) was determined for the porphyrins and their Ag complexes (Fig. 2) as it was reported for similar type of cationic meso-tetrakis( N-alkylpyridinium-2(or 3)-yl)porphyrins and their Mn complexes [41,43,44]. The lipophilicity of the latter compounds has conveniently been measured by Rf on silica gel plates using 1:1:8 = KNO3-saturated H2O:H2O:CH3CN (v/v) as a mobile phase and was shown to linearly relate to the partition between the n-octanol and water, Pow [41].

Fig. 2.

The lipophilicities of porphyrins (tetracationic H2TAll4PyP and tricationic H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P) and their Ag complexes (tetracationic AgTAll4PyP and tricationic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P) expressed in terms of chromatographic retention factor, Rf. Due to the introduction of a long lipophilic chain as well as a loss of single charge, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P and its Ag complex gained dramatically in lipophilicity as compared to their tetracationic analogs, H2TAll4PyP and its Ag complex. The lipophilicities of Ag complexes do not differ significantly as compared to their metal-free ligands mainly due to the absence of total charge difference between porphyrins and their corresponding metallocomplexes.

2.5. Cell lines and cell culture

The human cell lines HeLa (cervix carcinoma), HEP-3B (hepatocellular carcinoma), LN-308 (glioblastoma), and MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma) were generously provided by Prof. J. Masters (Institute of Urology and Nephrology, UCL, UK), and KCL-22 (chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis) was kindly provided by Dr. T. Liehr (Institute of Human Genetics and Anthropology, Germany). Human normal leukocytes (HNL) were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy, non-smoking donors of 24 to 30 years of age (women). Cells were routinely maintained in the growth media DMEM (cell lines HeLa, HEP-3B and MCF-7) or RPMI-1640 (cell lines KCL-22 and LN-308) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C.

2.6. Estimation of dark cytotoxicity and cell line- (cancer type-) specificity of Ag porphyrins

The dark toxicity of Ag porphyrins was estimated using vital dye (Trypan blue; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) exclusion test [45]. Cells were seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106/mL into 15 mL glass vials (1–2 mL of cell suspension per vial), incubated for 24 h, and then Ag porphyrin dissolved in distilled water was added to the cell cultures at various concentrations. After further incubation for 48 h, the viable cell number was determined. The cells were stained with 0.4% Trypan blue solution for 5–15 min and counted in a hemocytometer under a light microscope. Attached cells (cell lines HeLa, HEP-3B, LN-308 and MCF-7) were detached with trypsin–EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) prior counting. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the negative control (cell cultures with no treatment). Cisplatin, a well-known chemotherapeutic agent [46,47], was used as a positive control. Doses inducing 50% inhibition of cell viability (the IC50 value) were determined and compared to reveal the cell line- (cancer type-) specificity of Ag porphyrin.

2.7. Estimation of genotoxic effect of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P

2.7.1. The Comet assay (estimation of early DNA damage)

The basic principle of the single cell gel (Comet) assay is the migration of DNA fragments in an agarose matrix under electrophoresis. When viewed under a microscope, cells have the appearance of a comet, with a head (the nuclear region) and a tail containing DNA fragments migrating towards the anode.

In our experiments the Comet assay was performed under alkaline conditions according to the procedure described [48–50]. Cultures of KCL-22 cell line 24 h after seeding were treated with Ag porphyrin at the concentrations IC50, IC50/5 and IC50/20 and incubated for 2 h. The untreated cells were used as a negative control. Then 15 μL of cell suspension was mixed with 100 μL of 0.5% low melting agarose and spread on slides precoated with 1% normal melting point agarose dissolved in PBS. The cells were lysed for 1 h at 4 °C with a solution consisting of 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris, and 1% Triton X-100 at pH 10. After the cell lysis the slides were placed for 40 min into a horizontal electrophoresis box in a buffer consisting of 300 mM NaOH and 1 mM EDTA at pH > 13 to allow DNA to unwind. Electrophoresis was conducted at 4 °C for 25 min in an electric field at 25 V, 300 mA. The slides were then neutralized with 0.4 M Tris (pH 7.5) three times for 5 min and stained with 20 μg/mL ethidium bromide overnight (all reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany).

The comets were observed at 360 magnifications with a fluorescence microscope Zeiss III RS (Germany) equipped with a 560 nm excitation filter, 590 nm barrier filter and a CCD video camera PCO (Germany). At least 150 cells (50 cells for each of triplicate slides) were examined for each experimental point.

Image analysis software Komet 4 (Perceptive instruments, UK) was used to analyze the content of DNA in tail (by the relative tail fluorescence intensity in percent to the untreated control), L/H (relation of a comet length to its height) and OTM (the product of a tail length and the percentage of DNA content in the tail) of comets.

2.7.2. The micronucleus (MN) induction test

To determine the genotoxicity of the Ag porphyrin the cytokinesis block variant of the in vitro MN induction test was applied [51]. This test is known to detect agents that modify chromosome structure and segregation in such a way as to lead to the induction of MN in interphase cells. Treatment of cultures with the inhibitor of actin polymerization cytochalasin B results in the “trapping” of cells at the binucleate stage where they can be easily identified.

Cultures of HeLa cell line 24 h after seeding were added with Ag porphyrin at concentrations IC60, IC50, IC50/2 and IC50/5. Cell cultures treated with Mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) (MMC; 0.1 μg/mL final concentration) were used as a positive control [52]. 4 h later cytochalasin B (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) dissolved in ethanol was added to the final concentration of 3 μg/mL. Cell cultures incubated only with cytochalasin B were used as a negative control. After 20 h of incubation the cells were fixed with ethanol:acetic acid (3:1), air dried and stained with diluted (1:20) Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). One thousand cells per triplicate cell cultures were scored in situ, without cell detachment, to assess the frequency of cells with one, two or more nuclei. The cytokinesis block proliferation index (CBPI) as a measure of cell cycle delay was estimated by [51]:

The number of binucleate cells with MN was counted in 1000 binucleate cells in the same cultures. Only micronuclei not exceeding 1/3 of the main nucleus diameter, not overlapping with the main nucleus, and with distinct borders were included in the scoring.

2.8. Flow cytometric analysis of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P effect on the cell progression through the cell cycle

Cultures of the KCL-22 cell line 24 h after seeding were incubated with Ag porphyrin at the concentrations IC50/2, IC50 and IC60 for 48 h. About 106 cells were collected by centrifugation and treated on ice with 1 mL cold 70% ethanol added dropwise on a vortex to prevent cell aggregation. Then cells were fixed in ethanol at 4 °C overnight and stored at −20 °C for few days (up to a week) until the analysis performance. For the cell cycle analysis the cells were carefully washed twice with PBS and treated with PI-staining buffer containing 0.1 mg/mL RNase (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and 0.05 mg/mL propidium iodide (PI) (Fluka, Switzerland) for 30 min. The DNA content was determined using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton & Dickinson, San Jose) based on a C-value, i.e. the amount of DNA in the haploid genome of an eukaryotic cell, measured in picograms (for humans the 1C value describes the amount of DNA in 23 chromatids or unreplicated chromosomes). The nuclear DNA content reflects the position of a cell within a cell cycle. Thus, application of an intercalating dye propidium iodide enables to establish the distribution histogram of cells according to their fluorescence intensity. Cell doublets and aggregates were excluded based on forward and side scatter parameters. Gated events considered to be single particles were analyzed with Tree Star FlowJo software cell cycle analysis module using the Dean–Jett–Fox model, and were presented as the number of cells versus the amount of DNA as it is indicated by the fluorescence intensity [53].

2.9. Estimation of light and dark toxicity of amphiphilic free-base porphyrin, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P

KCL-22 cells were seeded into 15 mL glass vials (2 mL of cell suspension per a vial), incubated for 24 h and then various concentrations of free-base porphyrin dissolved in distilled water were added. After 30 min of preincubation the cell cultures were light irradiated using tungsten lamp (30 mW/cm2, 28,000 lx) with a glass filter (light transmission at 600–900 nm) for 25 min. The cells were then incubated for 48 h and the viable cell number was determined by the vital dye exclusion test. The negative controls were cell cultures added with porphyrin and kept in the dark, and illuminated cell cultures not added with porphyrin. Cell cultures treated with known PS Chlorin e6 [54,55] at various concentrations were used as a positive control. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the intact control. The IC50 values were determined by analysis of dose–response curves.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. At least triplicate cultures were scored for an experimental point. All values were expressed as means ± S.E.M. The Student’s one tail t-test was applied for statistical treatment of the results; p < 0.05 was considered as the statistically significant value. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used for statistical analysis of the Comet assay results.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis

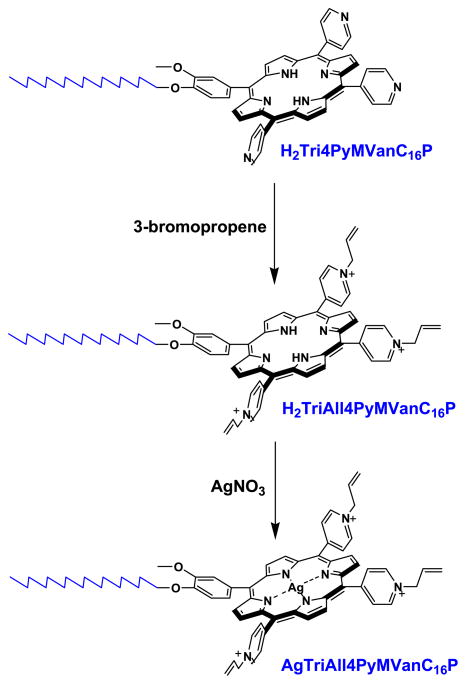

Six statistical porphyrinic isomers have been obtained via condensation of 3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxybenzaldehyde, 4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde and pyrrole by the modified Adler–Longo procedure [56]: H2T4PyP, H2Tri4PyMVanC16P, cis-H2Di4PyDiVanC16P, trans-H2Di4PyDiVanC16P, and H2M4PyTriVanC16P, H2TVanC16P (Scheme S1, Supplementary Material). Quaternization of pyridyl nitrogen atoms of H2Tri4PyMVanC16P by 3-bromopropene afforded the 5-(3′-metoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphine tribromide (H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P, amphiphilic porphyrin). The 5-(3′-metoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphinato Ag(II) trinitrate (AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P, amphiphilic Ag porphyrin) was prepared via interaction of free ligand H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P with silver nitrate (Scheme 1). The observed spectral transformations were in agreement with the data published earlier for tetracationic Ag porphyrins [35]; a strong Soret band and four weak Q-bands in absorption spectra typical for free-base porphyrin (H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P) were converted to a bathochromically shifted Soret and a single Q band typical of metallocomplex. All synthesized compounds were characterized in terms of elemental analysis, ESI-MS, UV–visible spectroscopy and 1H NMR technique (see in Materials and methods).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of amphiphilic porphyrin, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P (5-mono(3′-metoxy- 4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-tri (4′-N-allylpyridyl) porphine tribromide) and its silver metallocomplex, AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (5-mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)- 10,15,20-tri(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphinato Ag(II) trinitrate) from H2Tri4PyMVanC16P (5-mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-tri(4′-N-pyridyl)porphine) via two step procedure.

3.2. Lipophilicity

Generally, the thin-layer chromatography (TLC) retention factor, Rf, is recognized to be not a very accurate measure of compound’s lipophilicity. However, a study performed by Kos et al. clearly demonstrated that there is a linear correlation between TLC retention factor, Rf, and n-octanol/water partition coefficient, log Pow, for the water-soluble cationic N-substituted pyridylporphyrins [41]. Consequently, the authors justified the use of TLC retention factor, Rf, as a valid measure of porphyrin’s lipophilicity, especially for the comparison purposes, when the analogous compounds are tested during the same experimental run [43]. As expected, due to the introduction of long lipophilic chain as well as a single charge loss, AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P gained significantly in lipophilicity as compared to AgTAll4PyP (Fig. 2) as determined by TLC retention factors, Rf. The measured values for both amphiphilic porphyrin and its Ag complex are almost twice higher as that for tetracationic analogs (Fig. 2). The differences between the Rf values of amphiphilic and water-soluble porphyrins could be translated into more than 3 orders of magnitude increase in lipophilicity according to the reported relationship between Rf and Pow by Kos et al. for similar porphyrins and metalloporphyrins [41]. Notably, the lipophilicities of porphyrins and their corresponding Ag complexes do not differ significantly which is due to the absence of the overall charge difference, as well as the lack of additional interactions between the TLC plate sorbent and metal complexes. Ag(II) porphyrins with d9 configuration have little tendency to coordinate axial ligands [57] (Fig. 2).

3.3. Dark toxicity and cell line- (cancer type-) specificity of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P

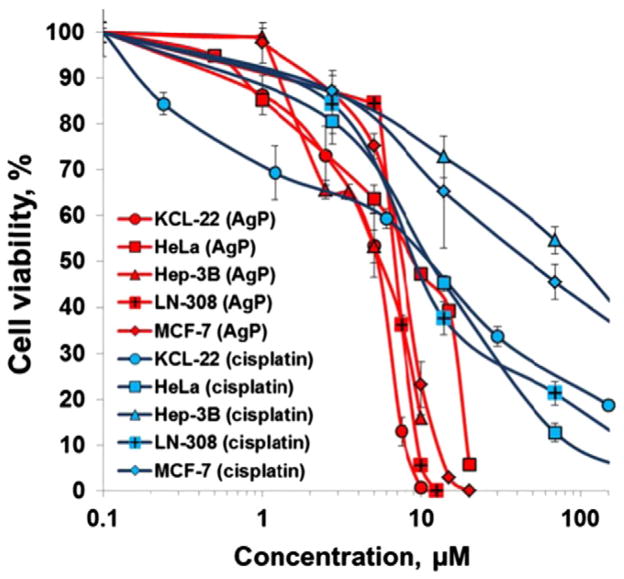

Five cancer cell lines derived from various tissue origin were subjected to this study: HeLa (cervix carcinoma), HEP-3B (hepatocellular carcinoma), LN-308 (glioblastoma), MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma), and KCL-22 (chronic myeloid leukemia). AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P was demonstrated to cause a dose-dependent cell survival reduction in all cell lines studied (Fig. 3). The sensitivity of cell lines tested (KCL-22, HEP- 3B, LN-308 and MCF-7) was fairly similar towards the amphiphilic metallocomplex (Table 2). The HeLa cell line was relatively less sensitive than the others. It was also shown that amphiphilic Ag porphyrin is up to 18-fold more toxic towards cancer cells than cisplatin used as a positive control (Table 2, Fig. 3). Of note, tested cancer cell lines showed vastly different sensitivity towards cisplatin. Silver nitrate employed in the preparation of metalloporphyrin showed no toxicity at up to 20 μM concentration on KCL-22 cell line (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

The cytotoxicity of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (AgP) in HeLa (cervix carcinoma), HEP-3B (hepatocellular carcinoma), LN-308 (glioblastoma), MCF-7 (breast adenocarcinoma) and KCL-22 (chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis) human cancer cell lines. The viability of cells was determined via Trypan blue exclusion assay after incubation of cells for 48 h with various concentrations of amphiphilic Ag porphyrin. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the negative control (cell cultures added with distilled water). The cytotoxicity of known chemotherapeutic cisplatin was also tested as a positive control.

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity (IC50 values) of water-soluble (AgTAll4PyP) and amphiphilic (AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P) Ag porphyrins on various cancer cell lines.

| Ag porphyrin | IC50 (μM) ± S.E.M.

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa | LN-308 | KCL-22 | MCF-7 | Hep-3B | |

| AgTAll4PyP | 26.0 ± 2.4 | 16.0 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 1.1 [35] | – | – |

| AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 5.6 ± 1.3 |

| Cisplatin | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 13.0 ± 1.5 | 46.7 ± 3.6 | 98.6 ± 6.8 |

The cytotoxicity of the AgTAll4PyP synthesized earlier [35] and AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (Fig. 1) for three human cell lines was compared (Table 2). AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P was significantly more toxic for HeLa and LN-308 cell lines and less toxic for KCL-22 cell line than AgTAll4PyP. So, alteration of Ag porphyrin hydrophilicity affected their cell line-specific cytotoxicity. In general, amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P expressed lower cell-line specificity than its water-soluble AgTAll4PyP did.

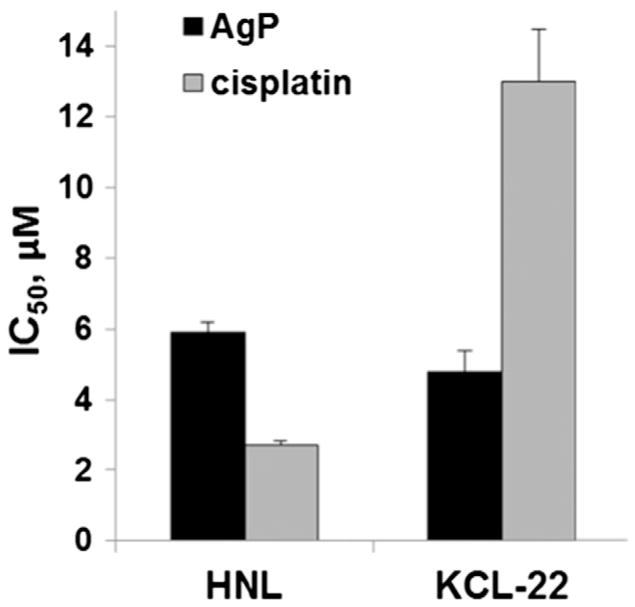

The selectivity of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P cytotoxic action towards human normal leukocytes (HNL) and its cancerous counterpart (KCL-22, chronic myeloid leukemia) was also tested and compared to that of cisplatin (Fig. 4). The results obtained showed that the Ag metallocomplex is significantly less toxic on normal (HNL) and more toxic to cancer (KCL-22) cells as compared to cisplatin. It is interesting to note, that cisplatin exhibited 5-fold higher cytotoxicity towards normal leukocytes than to their cancerous counterpart, whereas the toxicity of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P, although not significant, was higher towards cancer versus normal cells.

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity (IC50 values) of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (AgP) and cisplatin on human normal leukocytes (HNL) and chronic myeloid leukemia cells (KCL-22) determined by trypan blue exclusion assay.

3.4. DNA damage induced by amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (Comet assay)

The ability of AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P to induce DNA damage has been analyzed at three different concentrations, IC50/20, IC50/5 and IC50. Low (IC50/20) concentration of amphiphilic Ag porphyrin had no effect. AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P added to KCL-22 cells at concentrations IC50/5 and IC50 was shown to induce the breakage of DNA molecule 2 h after application (Table 3). However, the observed level of DNA damage is known to be reparable [58] and not to lead to heritable DNA/chromosome damage or to the cell death [59]. Thus, amphiphilic Ag porphyrin could induce early dose-dependent slow, transient and reparable DNA lesions. Their involvement in the formation of fixed, heritable DNA/chromosome damages in affected cells needs further investigation.

Table 3.

DNA damage induced by amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P in KCL-22 cell line measured by the Comet assay.

| Concentration of Ag porphyrin, μM | % DNA in tail

|

L/H

|

OTM

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± S.E.M. | Median | Mean ± S.E.M. | Median | Mean ± S.E.M. | Median | |

| 0 (control) | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.67 | 1.06 ± 0.00 | 1.06 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.34 |

| IC50/20 | 1.74 ± 0.14 | 1.74 | 1.08 ± 0.00 | 1.07 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.58 |

| IC50/5 | 3.10 ± 0.20 | 3.11* | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 1.12* | 1.42 ± 0.08 | 1.14* |

| IC50 | 9.36 ± 0.68 | 7.14* | 1.34 ± 0.01 | 1.32* | 5.63 ± 0.42 | 4.12* |

p < 0.05 in comparison with the control.

3.5. Genotoxicity of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P (MN induction test)

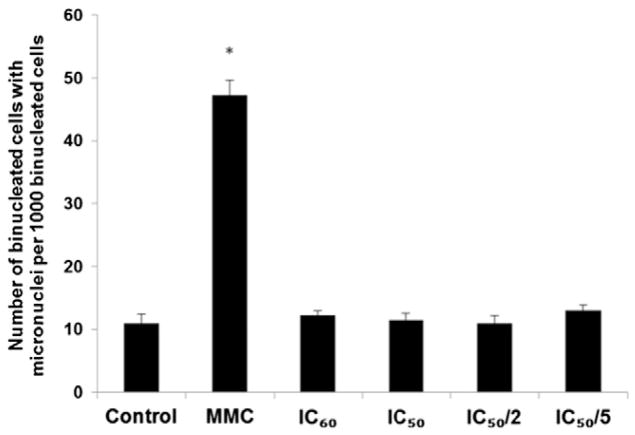

The background frequency of MN in HeLa cell line (i.e., the number of MN in untreated cultures) was lower than 30/1000 cells; thus, the cell system used meets the recommendations of OECD guideline [51]. Amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P did not induce MN formation at all concentrations applied (from IC50/5 to IC60) (Fig. 5). So, the early DNA lesions revealed by the Comet assay (see Section 3.3) did not contribute later to heritable genotoxic effects. At least, they did not participate in MN induction. In contrast, Mitomycin C (MMC) was observed to sharply increase the number of MNs (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P on the MN formation frequency in HeLa cell line. Cell cultures were treated with various concentrations of Ag porphyrin (IC60, IC50, IC50/2 and IC50/5) and Mitomycin C (MMC, as a positive control). One thousand binucleate cells per triplicate cell cultures were scored after “trapping” the cells with cytochalasin B at the binucleate stage and the number of binucleate cells with MN was counted. * p < 0.05 in comparison with the control. MN — micronucleus.

Amphiphilic Ag porphyrin was revealed to cause a weak dose-dependent cell cycle delay (expressed as CBPI) in HeLa cell line (Table 4). The IC60 and IC50 doses induced a small decrease in CBPI value (82% and 91% of the negative control, respectively), whereas the doses IC50/2 and IC50/5 demonstrated no effect.

Table 4.

Effect of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P on the proliferation rate in HeLa cell line.

| Treatment | CBPI | % of negative control | p to the negative control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | 1.46 ± 0.004 | 100 | |

| Positive control | 1.26 ± 0.01 | 86 | 0.024 |

| Ag porphyrin, IC50/5 | 1.42 ± 0.034 | 97 | 0.25 |

| Ag porphyrin, IC50/2 | 1.37 ± 0.004 | 94 | 0.17 |

| Ag porphyrin, IC50 | 1.33 ± 0.002 | 91 | 0.03 |

| Ag porphyrin, IC60 | 1.20 ± 0.002 | 82 | 0.004 |

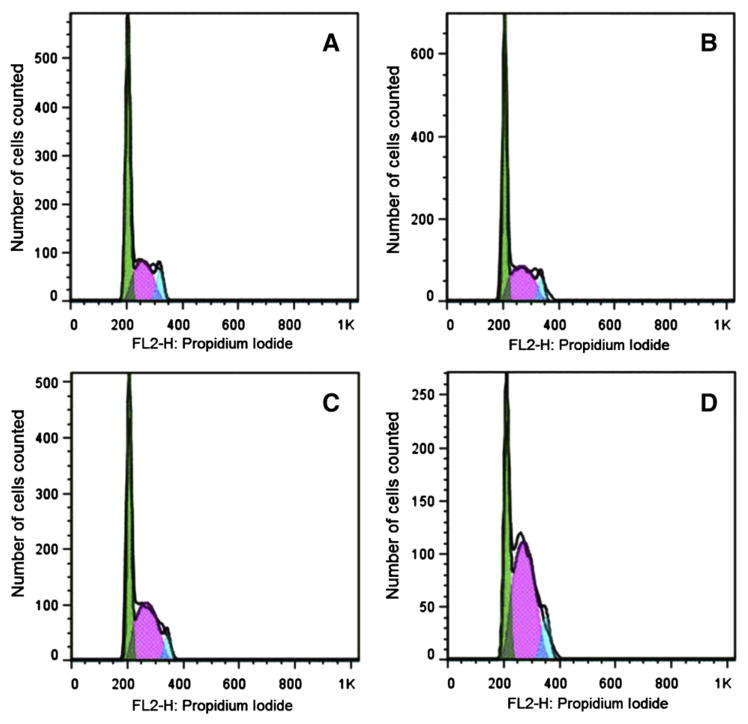

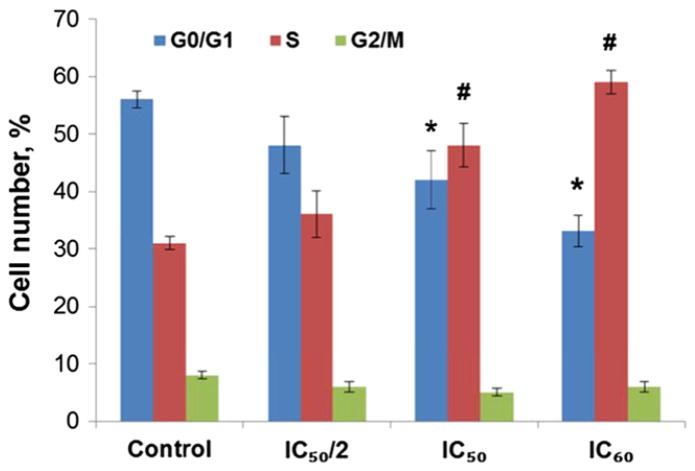

3.6. Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle effects of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P

The results of flow cytometric analysis of KCL-22 cells treated with various concentrations of AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P are shown in Fig. 6. The first large peak in each plot represented cells in G0/G1-phase (DNA content 2C) of the cell cycle; the following plateau (between 2C and 4C) represented the S-phase cells. The second peak showed cells in G2/M-phase (DNA content 4C). The number of events forming the S-plateau was higher in treated cultures in comparison with the untreated control; the G1 peaks were reduced and the G2 peaks were not changed.

Fig. 6.

DNA content-frequency representative histograms of KCL-22 cells untreated (A) and treated with IC50/2 (B), IC50 (C) or IC60 (D) concentrations of amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P for 48 h. Cell cycle analysis is presented as the number of cells counted versus the amount of DNA as it is indicated by the intensity of propidium iodide fluorescence. Percent analysis of cell distribution is presented in Fig. 7.

The analysis of cell distribution in the cell cycle (in percent, Fig. 7) also showed that the treatment with AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P significantly increased the S-phase cell number. The statistically significant reduction of cells in G1 phase was also evidenced in cultures treated with the IC50 or IC60 concentration. At the same time the number of cells in G2 phase were not changed. The results (Figs. 6 and 7) suggested that treatment of KCL-22 cells with amphiphilic Ag porphyrin interfered with the cell cycle, inducing the arrest of portion of cells at the S phase.

Fig. 7.

Cell cycle distribution in KCL-22 cell line treated with amphiphilic AgTriAll4 PyMVanC16P. * and # indicate statistically significant drop or increase with p < 0.05 versus control cell number (%) at G0/G1 and S phases, respectively.

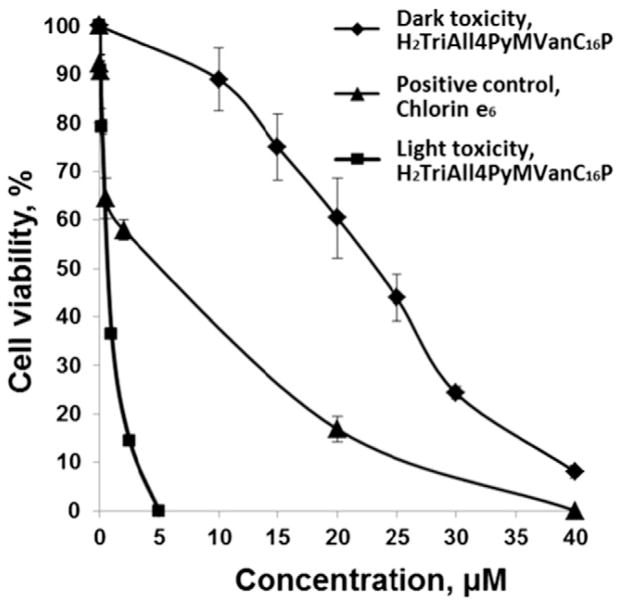

3.7. Light and dark toxicity of free-base amphiphilic porphyrin, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P

Earlier we have demonstrated, that free-base porphyrin H2TAll4PyP bears potential to be a prospective photosensitizer in photodynamic cancer therapy. Herein we aimed to investigate the effect of structural modification on the photodynamic potency of amphiphilic compound. The illumination of the cell suspensions in the presence of the amphiphilic free-base porphyrin H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P caused a concentration-dependent loss of cell viability (Fig. 8). The IC50 value (0.7 ± 0.1 μM) of this porphyrin measured upon cell culture illumination was lower than IC50 (25 ± 2 μM) of the same compound under the dark more than 35-fold. The porphyrin was 5 fold more phototoxic than Chlorin e6 (IC50 = 4.0 ± 0.2 μM). Thus, structural modification of free-base porphyrin from water-soluble molecule (H2TAll4PyP) [35] into amphiphilic one (H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P) led to a drastic increase in its both cytotoxicity and phototoxicity (IC50 values changed from >1600 to 25 and from 50 to 0.7 μM, respectively) (Table 5).

Fig. 8.

Dark and photo-induced cytotoxicity of amphiphilic free-base porphyrin, H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P on KCL-22 cell line. The toxicity of known photosensitizer Chlorin e6 on cell culture upon illumination is also presented as a positive control. KCL-22 cells, preincubated for 30 min with various concentrations of H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P (or Chlorin e6), were irradiated using tungsten lamp (30 mW/cm2, 28,000 lx)with a glass filter (light transmission at 600–900 nm) for 25 min. The cells were then incubated for 48 h and the viable cell number was determined by the vital dye exclusion test. Cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the intact control.

Table 5.

Cytotoxicity (IC50 values) of the amphiphilic free-base porphyrin H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P under dark conditions or illumination on KCL-22 cell line and comparison with its water-soluble analog (H2TAll4PyP). Chlorin e6 was tested as a positive control.

| Photosensitizer | IC50 (μM) ± S.E.M.

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Under dark | Photo-induced | |

| H2TAll4PyP [35] | >1600 | 50.0 |

| H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P | 25.0 ± 2.0 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| Chlorin e6 | >50.0 | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

4. Discussion

Historically, silver compounds were known for their strong antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties [60–62]. Their strong cytotoxic potential against cancer cells was also a promising aspect for many research groups to explore [63–65]. An additional advantage of the development of silver compounds as new metallodrugs is their low toxicity to humans [66]. Previously, we have demonstrated that water-soluble Ag porphyrins bear potential as effective chemotherapeutics and warrant further investigation [35]. Major advantage of having porphyrins as silver chelators over other silver ligators is their ability to selectively target the tumor tissue — a property, that may furthermore enhance the in vivo anticancer properties of silver porphyrins [1–5].

In the present work the structural modification of tetracationic H2TAll4PyP and its Ag(II) complex AgTAll4PyP (Fig. 1) [35] was performed to convert theminto amphiphilic compounds aiming to increase their bioavailability and, in turn, to improve their activity as potential anticancer agents. As a result, new tricationic porphyrin and its Ag(II) complex have been synthesized containing both lipophilic and hydrophilic groups at meso-positions of the porphine ring (Fig. 1). Ample of literature data indicate that porphyrins with properly balanced lipophilicity/hydrophilicity easily penetrate cell lipid barriers, have balanced plasma retention time and tissue availability, and display selectivity towards the malignant tissues [5,24,29,36,67–74]. Herein, as expected, conversion of the tetracationic AgTAll4PyP molecule to amphiphilic tricationic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P resulted in a significant increase in lipophilicity (Fig. 2), and, in turn, a certain increase in the cytotoxicity in vitro (for all cell lines tested but KCL-22 cell line). Interestingly, more than 600-fold increase in cytotoxicity on KCL-22 cell line was observed when the H2TAll4PyP (IC50 > 1600 μM) was converted to its Ag(II) complex, AgTAll4PyP (IC50 = 2.5 ± 1.1 μM). However, despite more than 60-fold increase in the cytotoxicity of H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P (IC50 = 25 ± 2.0 μM) over its tetracationic analog H2TAll4PyP, only 5-fold enhancement was achieved when the amphiphilic H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P was metallated (IC50 = 4.8 ± 0.6 μM for AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P). This differential enhancement could be attributed to the significant change in the intracellular distribution of Ag(II) complexes, which obviously plays a critical role for the expression of their cytotoxic action. In general, the AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P expressed lower cell line- (cancer type-) specificity as compared to AgTAll4PyP (Fig. 3, Table 2).

The new metallocomplex was not genotoxic as it provoked only slow early DNA damages (Table 5) that were apparently not expressed in posterior cell cycle events. The absence of induction of MN formation was a further evidence (Fig. 5) that early DNA damages revealed by the Comet assay were reparable. Amphiphilic AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P, however, demonstrated a slight cytostatic effect via the cell cycle delay due to the prolongation of S-phase and, presumably, blockage of affected cells at this phase (Figs. 6 and 7). This latter effect may likely be due to the ability of cationic porphyrins to bind to nucleic acids externally and/or internally (via intercalation) [75–77]. Other cellular structures, such as membranes, may be considered as potential targets of Ag porphyrins as well. Such tendency on preferential association with membrane structures was recently demonstrated for analogous Zn porphyrin ZnTnHex-4-PyP [78]. The properties revealed for amphiphilic Ag complex (high cytotoxicity, low cancer type-specificity, low genotoxicity and presence of a cytostatic effect) are, in general, desirable for anticancer drug candidates [79].

A well-known chemotherapeutic cisplatin was also tested in this study as a positive control. It is known, that it exhibits a variety of genotoxic side effects due to the strong crosslinks with DNA [80]. AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P seems to exert cytotoxic activity through mechanisms that are substantially different from those of cisplatin. Ag porphyrin provoked only slight and reparable DNA damages and did not induce MN formation, whereas such adverse effects of cisplatin are well known and widely documented in the literature [81]. Further, there is a certain difference between dose dependent cytotoxicity curves of the amphiphilic Ag porphyrin and cisplatin (Fig. 3). The cytotoxic concentration range for Ag porphyrin appeared to be much narrower than that of cisplatin. The AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P starts to exert toxicity at the ~1 μM concentration and caused 100% cell death at the dose not exceeding 20 μM, whereas cisplatin demonstrated cytotoxicity already at as low as ~0.2 μM concentration but IC100 value wasn’t reached even at 200 μM (Fig. 3). Such vast sensitivity of cancer cell lines for cisplatin has been already documented earlier by Tardito et al. [82]. Importantly, the sensitivity of normal human leukocytes was much higher towards cisplatin than to AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P. Moreover, cisplatin was 5-fold more toxic on normal leukocytes as compared to leukemia cells (Fig. 4).

The mechanism of the antiproliferative action of silver complexes is closely related to their interaction with thiol (sulfhydryl) groups of the proteins [60], hence differing from the behavior of several cytotoxic complexes of other metals (including cisplatin), which interact mainly with DNA [80,83,84]. The vast majority of silver compounds reported in the literature, however, contain the metal in the +1 oxidation state. As the metal site plays an important role in their cytotoxicity expression, the mechanism of Ag(II) porphyrins might be largely different from that of Ag(I) complexes exhibiting entirely different in vivo behavior.

In our earlier report we have shown, that tetracationic free-base porphyrin, H2TAll4PyP (Fig. 1) possesses light-induced cell toxicity [35]. Ag porphyrins generally cannot possess phototoxic activity as they include paramagnetic metal that is known to increase the probability for non-radiative decay of triplet excited state [85,86]. In this study we have evaluated the photocytotoxic potential of newly synthesized H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P aiming to reveal the impact of structural modification on compounds photocytotoxic ability (i.e., H2TAll4PyP vs. H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P) (Fig. 1). It is known that the overall charge and solubility, ability to interact with the cell, and subcellular localization play a critical role in photodynamic efficacy of PSs [87,88]. PSs of amphiphilic nature were shown elsewhere to have higher photodynamic activity than symmetrically hydrophobic or hydrophilic molecules [38,39,89–91]. As expected, the structural modification of free-base tetracationic porphyrin (H2TAll4PyP) led to the development of its tricationic analog H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P of amphiphilic nature, which in turn resulted in a drastic (more than 70-fold) amplification of its phototoxic activity (Fig. 8). The dark cytotoxicity of the porphyrin was also increased but remained much lower than the same of its Ag(II) complex, AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P. Thus, amphiphilic free-base porphyrin combines low dark cytotoxicity with high phototoxicity that meets one of the important demands to ideal PS [92].

In summary, new cationic non-symmetrically meso-substituted porphyrin and its Ag(II) complex were synthesized bearing long lipophilic group and tested for their potential as photosensitizing and chemotherapeutic agents, respectively. The study has revealed cationic Ag porphyrins as a promising new class of anticancer compounds. Further studies are in progress to elucidate the possible molecular mechanisms that lie behind the therapeutic action of Ag porphyrins and to demonstrate their in vivo efficacy on animal models. As testing of the substances was performed by accepted alternative in vitro techniques [93–95], this work may be considered as a part of preclinical investigation of pharmacological activities of drug candidates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the US Civilian Research and Development Foundation, the National Foundation of Science and Advanced Technologies (GRASP 29/06 and ECSP-09-36_SASP), the Armenian National Science and Education Fund (ANSEF-NS-biotech-1387) and the State Committee of Science in Armenia (SCS 13-1D053).

Abbreviations

- H2TVanC16P

5,10,15,20-tetra(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl) porphyrin

- H2T4PyP

5,10,15,20-tetra(4′-N-pyridyl)porphyrin

- H2M4PyTriVanC16P

5-mono(4′-N-pyridyl)-10,15,20-tri(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)porphyrin

- Trans-H2Di4PyDiVanC16P

5,15-di(4′-N-pyridyl)-10,20-di(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)porphyrin

- Cis-H2Di4PyDiVanC16P

5,10-di(4′-N-pyridyl)-15,20-di(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)porphyrin

- H2Tri4PyMVanC16P

5,10,15-tri(4′-N-pyridyl)-20-mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)porphyrin

- H2TriAll4PyMVanC16P

5-mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-tri(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphine tribromide (amphiphilic, tricationic porphyrin)

- AgTriAll4PyMVanC16P

5-mono(3′-methoxy-4′-hexadecyloxyphenyl)-10,15,20-tri(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphinato Ag(II) trinitrate (amphiphilic, tricationic Ag porphyrin)

- H2TAll4PyP

5,10,15,20-tetra(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphyrin tetrabromide (water-soluble, tetracationic porphyrin)

- AgTAll4PyP

5,10,15,20-tetra(4′-N-allylpyridyl)porphinato Ag(II) tetranitrate (water-soluble, tetracationic Ag porphyrin)

- CBPI

cytokinesis block proliferation index

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- HFBA

heptafluorobutyric acid

- IC50 and IC100

doses inducing 50 and 100% inhibition of cell viability, accordingly

- MN

micronucleus

- MMC

Mitomycin C

- PI

propidium iodide

- Pow

partition coefficient between n-octanol and water

- PS

photosensitizer

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.06.013. These data include MOL files and InChiKeys of the most important compounds described in this article.

References

- 1.Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, Foster TH, Girotti AW, Gollnick SO, Hahn SM, Hamblin MR, Juzeniene A, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Mroz P, Nowis D, Piette J, Wilson BC, Golab J. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:250–281. doi: 10.3322/caac.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bugaj AM. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10:1097–1109. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00147c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison RR, Moghissi K. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:24–29. doi: 10.5946/ce.2013.46.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali H, van Lier JE. In: The Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 4. World Scientific; 2010. pp. 1–121. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey RK, Zheng G. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 6. Academic Press; 2000. pp. 157–230. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senge MO. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:1943–1960. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03984e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Synthesis and Organic Chemistry. Academic Press; 2000. p. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ethirajan N, Patel NJ, Pandey RK. In: The Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 4. World Scientific; 2010. pp. 249–325. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo CC, Li HP, Zhang XB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:1745–1751. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kralova J, Kejik Z, Briza T, Pouckova P, Kral A, Martasek P, Kral V. J Med Chem. 2010;53:128–138. doi: 10.1021/jm9007278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lottner C, Bart KC, Bernhardt G, Brunner H. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2079–2089. doi: 10.1021/jm0110690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lottner C, Bart KC, Bernhardt G, Brunner H. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2064–2078. doi: 10.1021/jm0110688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lottner C, Knuechel R, Bernhardt G, Brunner H. Cancer Lett. 2004;215:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lottner C, Knuechel R, Bernhardt G, Brunner H. Cancer Lett. 2004;203:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow KH, Sun RW, Lam JB, Li CK, Xu A, Ma DL, Abagyan R, Wang Y, Che CM. Cancer Res. 2010;70:329–337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lum CT, Huo L, Sun RW, Li M, Kung HF, Che CM, Lin MC. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:719–726. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.537693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lum CT, Liu X, Sun RW, Li XP, Peng Y, He ML, Kung HF, Che CM, Lin MC. Cancer Lett. 2010;294:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun RW, Li CK, Ma DL, Yan JJ, Lok CN, Leung CH, Zhu N, Che CM. Chemistry. 2010;16:3097–3113. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keir ST, Dewhirst MW, Kirkpatrick JP, Bigner DD, Batinic-Haberle I. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11:202–212. doi: 10.2174/187152011795255957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moeller BJ, Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Rabbani ZN, Anscher MS, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y, Chaiswing L, Oberley TD, Batinic-Haberle I, St Clair W, Epstein CJ, St Clair D. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1401–1405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rawal M, Schroeder SR, Wagner BA, Cushing CM, Welsh JL, Button AM, Du J, Sibenaller ZA, Buettner GR, Cullen JJ. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5232–5241. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batinic-Haberle I, Tovmasyan A, Roberts ER, Vujaskovic Z, Leong KW, Spasojevic I. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:2372–2415. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batinic-Haberle I, Rajic Z, Tovmasyan A, Reboucas JS, Ye X, Leong KW, Dewhirst MW, Vujaskovic Z, Benov L, Spasojevic I. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1035–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:877–918. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I, Tse HM, Tovmasyan A, Rajic Z, St Clair DK, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Piganelli JD. Amino Acids. 2012;42:95–113. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0603-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tovmasyan A, Sheng H, Weitner T, Arulpragasam A, Lu M, Warner DS, Vujaskovic Z, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. Med Princ Pract. 2013;22:103–130. doi: 10.1159/000341715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohse T, Nagaoka S, Arakawa Y, Kawakami H, Nakamura K. J Inorg Biochem. 2001;85:201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(01)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asayama S, Kasugai N, Kubota S, Nagaoka S, Kawakami H. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasugai N, Murase T, Ohse T, Nagaoka S, Kawakami H, Kubota S. J Inorg Biochem. 2002;91:349–355. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuasa M, Oyaizu K, Horiuchi A, Ogata A, Hatsugai T, Yamaguchi A, Kawakami H. Mol Pharm. 2004;1:387–389. doi: 10.1021/mp049936v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babayan N, Tovmasyan A, Gevorkyan A, Gasparyan G, Aroutiounian R. Korean J Environ Biol. 2008;26:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gasparyan G, Hovhannisyan G, Ghazaryan R, Sahakyan L, Tovmasyan A, Grigoryan R, Sarkissyan N, Haroutiunian S, Aroutiounian R. Int J Toxicol. 2007;26:497–502. doi: 10.1080/10915810701707056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tovmasyan A, Ghazaryan R, Sahakyan L, Babayan N, Gasparyan G. EJC Suppl. 2007;5:116–116. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tovmasyan AG, Babayan NS, Sahakyan LA, Shahkhatuni AG, Gasparyan GH, Aroutiounian RM, Ghazaryarn RK. J Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2008;12:1100–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson BW, Bellnier DA, Greco WR, Sharma A, Pandey RK, Vaughan LA, Weishaupt KR, Dougherty TJ. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4000–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen TJ, Vicente MG, Luguya R, Norton J, Fronczek FR, Smith KM. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2010;100:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazzeri D, Rovera M, Pascual L, Durantini EN. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;80:286–293. doi: 10.1562/2004-03-08-RA-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alves E, Costa L, Carvalho CM, Tome JP, Faustino MA, Neves MG, Tome AC, Cavaleiro JA, Cunha A, Almeida A. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddi E, Jori G. Rev Chem Intermed. 1988;10:241–268. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kos I, Reboucas JS, DeFreitas-Silva G, Salvemini D, Vujaskovic Z, Dewhirst MW, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;48:1046–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tovmasyan AG, Rajic Z, Spasojevic I, Reboucas JS, Chen X, Salvemini D, Sheng H, Warner DS, Benov L, Batinic-Haberle I. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:4111–4121. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01321h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tovmasyan A, Weitner T, Sheng H, Lu M, Rajic Z, Warner DS, Spasojevic I, Reboucas JS, Benov L, Batinic-Haberle I. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:5677–5691. doi: 10.1021/ic3012519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strober W. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2001:A.3B.1–A.3B.2. Appendix 3. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alderden RA, Hall MD, Hambley TW. J Chem Educ. 2006;83:728–734. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:1663–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collins AR, Oscoz AA, Brunborg G, Gaivao I, Giovannelli L, Kruszewski M, Smith CC, Stetina R. Mutagenesis. 2008;23:143–151. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gem051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao W, McNutt MA, Zhu WG. Methods. 2009;48:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175:184–191. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Test No. 487: Draft Proposal for a New Guideline. In Vitro Micronucleus Test, 2nd Version, 2006.

- 52.Kirsch-Volders M, Sofuni T, Aardema M, Albertini S, Eastmond D, Fenech M, Ishidate M, Jr, Kirchner S, Lorge E, Morita T, Norppa H, Surralles J, Vanhauwaert A, Wakata A. Mutat Res. 2003;540:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pozarowski P, Darzynkiewicz Z. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;281:301–311. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-811-0:301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horibe S, Nagai J, Yumoto R, Tawa R, Takano M. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:3010–3017. doi: 10.1002/jps.22501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Z. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2005;4:283–293. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adler AD, Longo FR, Finarelli JD, Goldmacher J, Assour J, Korsakoff L. J Org Chem. 1967;32:476–482. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanders J, Bampos N, Clyde-Watson Z, Darling S, Hawley J, Kim H-J, Mak C, Webb S. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 3. Academic Press; 2000. pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aroutiounian RM, Hovhannisyan GG, Gasparyan GH, Margaryan KS, Aroutiounian DN, Sarkissyan NK, Galoyan AA. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:598–602. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olive PL, Wlodek D, Banath JP. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4671–4676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banti CN, Hadjikakou SK. Metallomics. 2013;5:569–596. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00046j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chopra I. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:587–590. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Politano AD, Campbell KT, Rosenberger LH, Sawyer RG. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2013;14:8–20. doi: 10.1089/sur.2011.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iqbal MA, Haque RA, Nasri SF, Majid AA, Ahamed MB, Farsi E, Fatima T. Chem Cent J. 2013;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kyros L, Kourkoumelis N, Kubicki M, Male L, Hursthouse MB, Verginadis E, II, Gouma S, Karkabounas K, Charalabopoulos SK, Hadjikakou Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2010:386860. doi: 10.1155/2010/386860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pellei M, Gandin V, Marinelli M, Marzano C, Yousufuddin M, Dias HV, Santini C. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:9873–9882. doi: 10.1021/ic3013188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Banti CN, Giannoulis AD, Kourkoumelis N, Owczarzak AM, Poyraz M, Kubicki M, Charalabopoulos K, Hadjikakou SK. Metallomics. 2012;4:545–560. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20039b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haruyama T, Asayama S, Kawakami H. J Biochem. 2010;147:153–156. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kessel D. Cancer Lett. 1986;33:183–188. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(86)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kessel D, Luguya R, Vicente MG. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;78:431–435. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)078<0431:lapeot>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moan J, Peng Q, Evensen JF, Berg K, Western A, Rimington C. Photochem Photobiol. 1987;46:713–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oenbrink G, Jurgenlimke P, Gabel D. Photochem Photobiol. 1988;48:451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1988.tb02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weitner T, Kos I, Sheng H, Tovmasyan A, Reboucas JS, Fan P, Warner DS, Vujaskovic Z, Batinic-Haberle I, Spasojevic I. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;58:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyle RW, Dolphin D. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;64:469–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jori G. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;36:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Briggs BN, Gaier AJ, Fanwick PE, Dogutan DK, McMillin DR. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7496–7505. doi: 10.1021/bi300828z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dalyan YB, Haroutiunian SG, Ananyan GV, Vardanyan VI, Lando DY, Madakyan VN, Kazaryan RK, Messory L, Orioli P, Benight AS. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2001;18:677–687. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2001.10506698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim YR, Gong L, Park J, Jang YJ, Kim J, Kim SK. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:2330–2337. doi: 10.1021/jp212291r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ezzeddine R, Al-Banaw A, Tovmasyan A, Craik JD, Batinic-Haberle I, Benov LT. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36579–36588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.511642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rixe O, Fojo T. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7280–7287. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kliesch U, Adler ID. Mutat Res. 1987;192:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(87)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Serpeloni JM, Grotto D, Mercadante AZ, de Lourdes Pires Bianchi M, Antunes LM. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84:811–822. doi: 10.1007/s00204-010-0576-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tardito S, Isella C, Medico E, Marchio L, Bevilacqua E, Hatzoglou M, Bussolati O, Franchi-Gazzola R. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24306–24319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brulikova L, Hlavac J, Hradil P. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19:364–385. doi: 10.2174/092986712803414295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turel I, Kljun J. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:2661–2687. doi: 10.2174/156802611798040787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berg K, Selbo PK, Weyergang A, Dietze A, Prasmickaite L, Bonsted A, Engesaeter BO, Angell-Petersen E, Warloe T, Frandsen N, Hogset A. J Microsc. 2005;218:133–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2005.01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Detty MR, Gibson SL, Wagner SJ. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3897–3915. doi: 10.1021/jm040074b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Peng Q. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kessel D, Luo Y, Deng Y, Chang CK. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;65:422–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb08581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jiang FL, Poon CT, Wong WK, Koon HK, Mak NK, Choi CY, Kwong DW, Liu Y. Chembiochem. 2008;9:1034–1039. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Peritore C, Simonis U. VDM Verlag. 2009:140. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Poon CT, Chan PS, Man C, Jiang FL, Wong RN, Mak NK, Kwong DW, Tsao SW, Wong WK. J Inorg Biochem. 2010;104:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Allison RR, Downie GH, Cuenca R, Hu XH, Childs CJH, Sibata CH. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2004;1:27–42. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hassan SB. Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Sciences, Vol. Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine) Uppsala University; Uppsala: 2004. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sharma SV, Haber DA, Settleman J. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:241–253. doi: 10.1038/nrc2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jena GB, Kaul CL, Ramarao P. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005:209–222. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.