Abstract

The impact of extramedullary disease (EMD) in AML on the outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) is unknown. Using data from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) we compared the outcomes of patients who had EMD of AML at any time prior to transplant to a cohort of AML patients without EMD. We reviewed data AML from 9,797 patients including 814 with EMD from 310 reporting centers and 44 different countries who underwent alloHCT between and 1995–2010. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS) after alloHCT. Secondary outcomes included leukemia-free survival (LFS), relapse rate, and treatment-related mortality (TRM). In a multivariate analysis, the presence of EMD did not affect either OS (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.91–1.09), LFS (0.98, 0.89–1.09), TRM (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.16, p=0.23) or relapse (RR =1.03, 95% CI, 0.92–1.16; p=0.62). Furthermore, the outcome of patients with EMD was not influenced by the location, timing of EMD, or intensity of conditioning regimen. The presence of EMD in AML does not affect transplant outcomes and should not be viewed as an independent adverse prognostic feature.

Keywords: extramedullary acute myeloid leukemia, allogeneic transplant, granulocytic sarcoma

Introduction

Extramedullary disease (EMD) in AML refers to disease found in organs or tissue outside the blood or bone marrow. The most common manifestations of EMD include myeloid sarcomas, leukemia cutis, and meningeal leukemia. Although the exact frequency is unknown, EMD has been estimated to occur in 3 – 8% of patients with AML, and has been reported to be more common in patients with core-binding factor leukemia, FAB M2/M4/M5, high WBC count and increased age.1 Historically, the presence of EMD has been considered a poor prognostic feature in AML.2 However, the impact of EMD may depend on the site of EMD as well as cytogenetic and molecular features. In adult patients with t(8:21), complete remission (CR) rates (50% vs 92%) and overall survival (OS) (5.4 vs 59.5 months) were markedly worse in patients with EMD treated with standard 7+3 regimens.3 In a retrospective analysis of 434 Japanese patients with AML, myeloid sarcomas were associated with higher relapse rate and lower disease-free survival (DFS).4

Due to its potent antitumor effects, it has been suggested that allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT) could overcome the potential poor prognostic impact of EMD in AML. However, data supporting this approach are limited. A retrospective study from the Société Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Thérapie Cellulaire (SFGM-TC) registry of 51 patients with myeloid sarcoma who underwent alloSCT demonstrated an OS of 36% at 5 years confirming that alloSCT is a valid therapeutic option.5 Isolated EMD relapses are common following alloHCT in patients with AML indicating a relative lack of graft vs. leukemia effect in EMD sites.6 Furthermore, reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens, T cell depleted grafts, or non-total body irradiation (TBI) based conditioning regimens have been associated with higher rates of EMD relapse and may reduce the effectiveness of alloHCT in AML with EMD disease.7–10

Because a prospective study to determine the impact of alloHCT for AML with EMD is not feasible, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIMBTR) database offers a comprehensive dataset to identify factors that influence the outcome of alloHCT for AML with EMD. In this study, we compared the outcomes of patients who had EMD of AML at any time prior to transplant to a cohort of AML patients without EMD. We also examined disease-, treatment-, and transplant-related characteristics that affected the outcomes of patients with EMD.

Patients and methods

Data source

The CIBMTR, a voluntary working group of more than 500 transplant centers worldwide, contribute data on consecutive allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplants to a statistical center housed both at the Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI) and the National Marrow Donor Program (Minneapolis, MN). Observational studies conducted by CIBMTR are performed with a waiver of informed consent and in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations as determined by the Institutional Review Board and the Privacy Officer of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Patient selection

The study population consists of AML patients between 18–70 years of age who underwent bone marrow or peripheral blood alloHCT from either an HLA-identical sibling or unrelated donor between 1995 and 2010. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia were excluded.

The site of EMD was determined by the reporting center in one of four categories: CNS, soft tissue, testes, or other. The “other” category was further subdivided into clinically relevant categories such as “skin” and “liver/spleen”. Pathologic or radiographic confirmation of EM disease was not required. Cytogenetics were classified according to SWOG/ECOG criteria.11 Conditioning regimens were classified as myeloablative (MA), reduced-intensity (RIC), or non-myeloablative (NMA).12, 13 CIBMTR classifications of unrelated donor (URD) matching were used to define well-matched, partially matched or mismatched categories.

Study end points and definitions

The primary outcome was overall survival (OS) after alloHCT (defined as the time from transplantation to death). Secondary end points included leukemia-free survival (LFS), relapse rate, and treatment-related (non-relapse) mortality (TRM; defined as any death in the first 28 days after transplantation or any death after day 28 in continuous remission), incidence of grade II–IV acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and the presence of chronic GVHD. Surviving patients were censored at the time of last contact.

Statistical analysis

Patient-, disease- and treatment-related factors were compared between EMD and non-EMD groups using the Chi-Square tests for categorical and Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. The probability of LFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, with the variance estimated by Greenwood’s formula. Values for other endpoints were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks.14

EMD and non-EMD groups were compared using proportional hazards regression models. Risk factors with significant level of p<0.05 in stepwise model building procedures were included in the outcome models. Potential interactions between the main effect (EMD status) and conditioning intensity, cytogenetic risk and other significant variables were examined.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 9,797 patients were identified from 310 reporting centers and 44 different countries: 814 with EMD prior to alloHCT (EMD group) and 8,983 without EMD pre-transplant (non-EMD group). The median follow-up of survivors was 58 months (range, 3–191 months) for the EMD group and 60 months (range, 3–194 months) for the non-EMD group.

Table 1 lists patient-, disease-, treatment-, and transplant-related variables for all patients. Patients with EMD tended to be younger (median age of 42 vs. 46 years, p < 0.001), were more likely to have a monocytic subtype (FAB M4-M5, 46 vs 29%, p < 0.001), and a higher initial WBC at diagnosis (22 vs 9, p<0.001). The most common site of EMD was CNS involvement (n=293, 35%). For other sites, 155 (19%) had skin-only and 112 (14%) possessed lymph node-only EMD. An additional 69 (8%) reported multiple sites of EMD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients between 18 to 70 years of age who underwent allogeneic transplant for AML between 1995 and 2010 reported to the CIBMTR

| Characteristics of patients | No-extramedullary disease | Extramedullary | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 8983 | 814 | |

| Number of centers | 299 | 178 | |

| Age, median (range) | 46 (18–70) | 42 (18–70) | <0.001 |

| Age in decades | <0.001 | ||

| 18–29 | 1533 (17) | 199 (24) | |

| 30–39 | 1599 (18) | 164 (20) | |

| 40–49 | 2311 (26) | 206 (25) | |

| 50–59 | 2364 (26) | 186 (23) | |

| 60–70 | 1176 (13) | 59 (7) | |

| Sex | 0.03 | ||

| Male | 4692 (52) | 458 (56) | |

| Female | 4291 (48) | 356 (44) | |

| Karnofsky score | 0.01 | ||

| <90% | 2877 (32) | 301 (37) | |

| >=90% | 5652 (63) | 470 (58) | |

| Missing | 454 (5) | 43 (5) | |

| Sub-disease | <0.001 | ||

| M0-M1 | 1737 (19) | 124 (15) | |

| M2 Myelocytic | 2014 (22) | 91 (11) | |

| M4-M5 | 2579 (29) | 374 (46) | |

| M6 Erythroblastic | 311 (3) | 7 (<1) | |

| M7 Megakaryoblastic | 137 (2) | 12 (1) | |

| Granulocytic sarcoma with unknown subtype | 0 | 71 (8) | |

| AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22)(AML1/ETO) | 39 (<1) | 8 (<1) | |

| AML with abnormal BM eosinophils (CBFb/MYH11) | 37 (<1) | 4 (<1) | |

| AML with multi-lineage dysplasia | 530 (6) | 21 (3) | |

| AML, other specified | 250 (3) | 36 (4) | |

| AML, subtype unknown | 1349 (16) | 66 (8) | |

| White blood count at diagnosis, ×10^9/L | <0.001 | ||

| Median (range) | 9 (<1–1000) | 22 (<1–600) | |

| <= 10 | 3998 (45) | 253 (31) | |

| 10 – 100 | 2965 (33) | 334 (41) | |

| > 100 | 707 (8) | 120 (15) | |

| Missing | 1313 (15) | 107 (13) | |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | <0.001 | ||

| Favorable | 555 (6) | 72 (9) | |

| Intermediate | 4129 (46) | 407 (50) | |

| Poor | 1752 (20) | 140 (17) | |

| Missing | 2547 (28) | 195 (23) | |

| Previous history of MDS | <0.001 | ||

| No | 7182 (80) | 709 (87) | |

| Yes | 1709 (19) | 94 (12) | |

| Missing | 92 (1) | 11 (1) | |

| Disease status prior to conditioning | <0.001 | ||

| Primary induction failure | 1313 (15) | 97 (12) | |

| CR1 | 4367 (49) | 305 (37) | |

| >=CR2 | 1773 (20) | 214 (26) | |

| Relapse | 1530 (17) | 198 (24) | |

| Extramedullary disease | N/A | ||

| Not present | 8983 | 0 | |

| At both diagnosis and transplant | 0 | 60 (7) | |

| At diagnosis only | 0 | 542 (67) | |

| At transplant only | 0 | 159 (20) | |

| CNS leukemia present any time prior to conditioning | 0 | 53 (7) | |

| Site of extramedullary diseasea | |||

| Any CNS | 0 | 283 (35) | |

| Skin only | 0 | 155 (19) | |

| Lymph node only | 0 | 112 (14) | |

| Other | 0 | 264 (32) | |

| Not applicable | 8983 | 0 | |

| Time from extramedullary disease to transplant, months | N/A | 5 (<1–133) | |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, months | 0.21 | ||

| Median (range) | 6 (<1–321) | 7 (<1–200) | 0.23 |

| <6 | 4188 (47) | 360 (44) | |

| 6 – 12 | 2451 (27) | 231 (28) | |

| >12 | 2338 (26) | 221 (27) | |

| Missing | 6 (<1) | 2 (<1) | |

| Conditioning regimen combination | <0.001 | ||

| MA with TBI | 3123 (35) | 383 (47) | |

| MA without TBI | 3562 (40) | 283 (35) | |

| RIC/NMA | 2298 (26) | 148 (18) | |

| Type of donor | <0.001 | ||

| HLA-identical sibling | 3536 (39) | 360 (44) | |

| Well-matched unrelated | 3057 (34) | 243 (30) | |

| Partially-matched unrelated | 1547 (17) | 119 (15) | |

| Mismatched unrelated | 487 (5) | 40 (5) | |

| Unrelated unknown | 356 (4) | 52 (6) | |

| Graft type | 0.97 | ||

| Bone marrow | 3229 (36) | 292 (36) | |

| Peripheral blood | 5754 (64) | 522 (64) | |

| Year of transplant | 0.01 | ||

| 1995–2000 | 2446 (27) | 259 (32) | |

| 2001–2005 | 3213 (36) | 262 (32) | |

| 2006–2010 | 3324 (37) | 293 (36) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 60 (3–194) | 58 (3–191) | |

| Patients transplanted in CR2 only | 1649 | 200 | |

| Duration of CR1, months | <0.001 | ||

| Median (range) | 11 (<1–187) | 9 (<1–110) | <0.001 |

| <6 | 308 (19) | 63 (32) | |

| 6 – 12 | 475 (29) | 59 (30) | |

| >12 | 631 (38) | 53 (27) | |

| Missing | 235 (14) | 25 (13) |

Other sites of extramedullary disease include:

liver/spleen only, n=45; multiple sites, n=69; other specified, n=150

example of other specified: pelvic soft tissue mass; salivary gland chloroma; mass in right lung base; gum pyperplacy ecxema (paws); breast infiltrate; left mandible; gastric chloroma; bone (knee); thorencentesis fluid; polychondritis etc.

Transplant conditioning regimens differed between the two groups. In the EMD group, 82% received a MA preparative regimen with 47% receiving a MA conditioning with total body irradiation compared to 75% and 35% respectively in the non-EMD group (p<0.001 for both comparisons). Disease status prior to conditioning also differed between the non-EMD and EMD groups: primary induction failure (PIF) 15% vs 12%, CR1 49% vs 37%, CR2 or beyond 20% vs 26%, active relapse 17% vs 24%, respectively (p < 0.001). The duration of first remission was shorter for subjects transplanted in CR2 in the EMD group vs the non-EMD group, 9 vs 11 months (p < 0.001) with 32% having a CR1 duration of < 6 months compared to 19% (p < 0.001) in the non-EMD group.

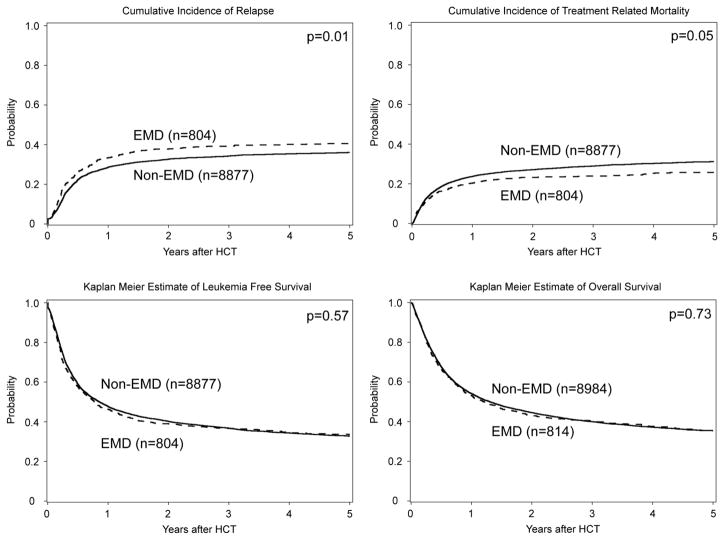

Univariate analysis of outcomes

Comparisons of outcomes between the EMD and non-EMD groups are listed in Table 2. There were no significant differences in LFS or OS, the primary end-points of our study, between patients with and without EMD in univariate analysis (Figure 1, Table 2). The 5 year LFS and OS for the EMD group was 33% (95%CI 30–37%) and 36% (95%CI 32–39%) respectively. The relapse rate in the EMD groups was significantly higher at 1 year (33% vs 29%, p = 0.012) and 3 years (39% vs 34%, p = 0.022) post-transplant compared to the non-EMD group. However, this risk was offset by lower rates of TRM post-transplant at 3 years (24% vs 29%, p = 0.009) and 5 years (26% vs 31%, p = 0.009) in the EMD group.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of outcomes

| No-EMD (N = 8983) | EMD (N = 814) | EMD and MD at HCT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes‡ | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) |

| Acute GVHD, grade II–IV | 8938 | 811 | 61 | |||

| 100-day | 36 (35–37)% | 35 (32–38)% | 38 (26–51)% | |||

| Chronic GVHD | 8712 | 793 | 59 | |||

| 1-year | 41 (40–42)% | 42 (38–45)% | 25 (14–38)% | |||

| 3-year | 45 (44–46)% | 45 (42–49)% | 28 (16–41)% | |||

| 5-year | 46 (44–47)% | 46 (42–49)% | 28 (16–41)% | |||

| Relapse | 8877 | 804 | 60 | |||

| 1-year | 29 (28–29)% | 33 (30–37)% | 58 (45–70)% | |||

| 3-year | 34 (33–35)% | 39 (36–43)% | 62 (48–73)% | |||

| 5-year | 36 (35–37)% | 41 (37–44)% | 62 (48–73)% | |||

| Treatment related mortality | 8877 | 804 | 60 | |||

| 1-year | 24 (23–25)% | 20 (18–23)% | 25 (15–37)% | |||

| 3-year | 29 (28–30)% | 24 (21–27)% | 29 (18–41)% | |||

| 5-year | 31 (30–32)% | 26 (23–29)% | 35 (22–48)% | |||

| Leukemia free survival | 8877 | 804 | 60 | |||

| 1-year | 48 (47–49)% | 46 (43–50)% | 17 (8–27)% | |||

| 3-year | 37 (36–38)% | 37 (33–40)% | 9 (3–18)% | |||

| 5-year | 33 (32–34)% | 33 (30–37)% | NE† | |||

| Overall survival | 8983 | 814 | 61 | |||

| 1-year | 54 (53–55)% | 53 (50–57)% | 21 (12–32)% | |||

| 3-year | 40 (39–41)% | 40 (37–44)% | 10 (4–20)% | |||

| 5-year | 35 (34–37)% | 36 (32–39)% | 5 (1–13)% | |||

No case at risk at this time point

Gray’s test: p=0.92 for aGVHD, p=0.21 for cGVHD, p<0.001 for relapse, p=0.031 for TRM.

Log-rank test: p<0.001 for DFS, p<0.001 for OS

Figure 1. Analysis of HCT outcome by EMD vs. no-EMD.

Probability of overall survival (OS), leukemia free-survival (LFS) and cumulative incidence frequency (CIF) of treatment related mortality (TRM) and relapse

For the 61 patients who proceeded to transplant with active medullary and EMD, univariate analysis showed significantly higher 3-year relapse rate when compared to EMD group (62% vs 39%, p = <0.001), and significantly worse 3-year LFS (9% vs 37%, p = <0.001), and OS (10% vs 40%, p = <0.001). (Table 2).

Leukemia was the most common cause of death in the non-EMD group (42%) and EMD group (49%), followed by infection and GVHD (Supplemental Table 1). For all patients who relapsed after transplant, there were significant differences in the site of relapse post-transplant (Supplemental Table 2). In the EMD group, 26% (14% EM site, 12% peripheral blood (PB)/bone marrow (BM) and EM site) of patients relapsed at extramedullary sites whereas only 9% (5% EM site, 4% PB/BM and EM site) of patients in the non-EMD group relapsed at extramedullary sites. For patients transplanted in ≥ CR2 or at relapse, 23% of the EM group relapsed solely at an EM site post-transplant and 18% relapsed at both medullary and EM sites.

Multivariate analysis of outcomes

Because of the poor outcomes of subjects with both EMD and active marrow disease at the time of transplant, these patients were excluded from the multivariate analysis. Notably, the presence of EMD did not affect either OS (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.91–1.09; p=0.91) or LFS (0.98, 0.89–1.09; p=0.74). In addition, differences in both TRM (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.06, p=0.23) and relapse (RR =1.03, 95% CI, 0.92–1.16; p=0.62) failed to retain their significance in the multivariate model (Table 4, Supplemental Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of outcome

| Univariate | Multivariate‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | N | RR (95% CI) | P | RR (95% CI) | P |

| Overall Survival | |||||

| no-EMD | 8983 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.91 |

| EMD | 814 | 1.02 (9.03–1.11) | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | ||

| Leukemia Free Survival | |||||

| no-EMD | 8877 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.74 |

| EMD | 804 | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) | ||

| Treatment Related Mortality | |||||

| no-EMD | 8877 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.23 |

| EMD | 804 | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | 0.92 (0.80–1.06) | ||

| Relapse | |||||

| no-EMD | 8877 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.62 |

| EMD | 804 | 1.16 (1.03–1.30) | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) | ||

MVA model adjusted for: WBC at diagnosis, previous history of MDS, cytogenetic risk group, disease status prior to HSCT, duration of CR1, site of relapse for patients transplanted in >=CR2, time from diagnosis to HSCT, consolidation treatment, age group, conditioning regimen, type of donor, graft type, CMV serostatus, year of HSCT, GVHD prophylaxis.

DLI was excluded from model.

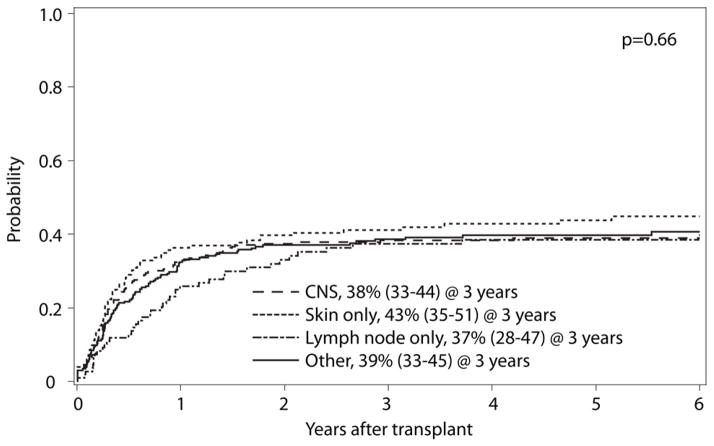

Outcome site of EMD disease or by onset of EMD

No significant differences were observed in the rate of relapse, (p=0.66, Figure 2) or OS based on by site of EMD (p=0.28, Table 3). We compared the outcomes of the 71 patients who had an isolated granulocytic sarcoma compared to the remaining 743 patients with both EMD and marrow involvement of their leukemia (Supplemental Table 3). We also examined the timing of EMD onset, whether EMD was present at the time of diagnosis or at the time of transplantation. Again, in each case, there was no difference in OS between these two groups. (Table 3)

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of relapse based on anatomic location of EMD.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis based on EMD site and time of EMD onset

| EMD site | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any CNS | Skin only | Lymph node only | Other | No EMD | |||||||

| Outcomes | N | Prob | N | Prob | N | Prob | N | Prob | N | Prob | P-value |

| Overall survival | 283 | 155 | 112 | 264 | 8983 | ||||||

| 1-year | 55 (49–60)% | 44 (36–52)% | 60 (50–69)% | 54 (48–60)% | 54 (53–55)% | 0.11 | |||||

| 3-year | 42 (36–48)% | 35 (27–42)% | 43 (33–52)% | 41 (35–47)% | 40 (39–41)% | 0.62 | |||||

| 5-year | 39 (33–45)% | 28 (21–36)% | 34 (25–44)% | 37 (31–44)% | 35 (34–37)% | 0.28 | |||||

| Time of EMD onset | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At diagnosis | At transplant | No EMD | |||||

| Outcomes | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | N Eval | Prob (95% CI) | P-value |

| Overall survival | 602 | 159 | 8983 | ||||

| 1-year | 55 (51–59)% | 45 (37–53)% | 54 (53–55)% | 0.07 | |||

| 3-year | 42 (38–46)% | 34 (26–41)% | 40 (39–41)% | 0.15 | |||

| 5-year | 37 (33–41)% | 30 (22–37)% | 35 (34–37)% | 0.27 | |||

Pretransplant conditioning

Because the GVL effect might be weaker in EM sites6, we also tested for any interaction between the presence of EMD and the intensity of the conditioning regimen on the risk of relapse which might confound our analysis. No interaction was identified between MA and RIC on the risk of relapse (P=0.1591). After MA conditioning, the relative risk of relapse was 1.09 (95% CI, 0.95–1.24; p=0.21) and for RIC was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.70–1.14; p=0.36).

Acute and chronic GVHD

At day 100, the incidence of grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD was similar between the EMD and non-EMD groups (35% vs 36%, p=0.60, Table 2). The incidence of chronic GVHD at 1-, 3-, and 5-years was also similar between the 2 groups.

Discussion

This analysis of 814 patients with EM involvement of AML represents the largest and most comprehensive analysis of alloHCT outcomes in this patient population. Historically, EMD has been viewed as a poor prognostic factor, although data supporting this position are limited. For other risk factors in AML such as a monosomal karyotype and FLT3-ITD, the adverse prognostic impact persists despite alloHCT.15, 16 Unexpectedly, when compared to a non-EMD cohort, we did not identify any impact of EMD itself on either survival, disease relapse, or treatment related mortality. In addition the location, timing of EMD, or intensity of conditioning regimen also did not affect transplant outcomes.

As with any large retrospective registry study, there are important limitations in our analysis. The presence and location of EMD was determined by the reporting center and did not require a confirmatory pathologic or radiographic diagnosis. This may result in underreporting of EMD in locations such as lymph nodes and deep soft tissue sites that can escape detection on routine clinical examination, and over reporting in areas such as the skin, where leukemia cutis may be confused with other dermatologic conditions. At the same time, this mirrors current clinical practice in which no guidelines or standards exist for the evaluation of EMD.

Because of the relative uncommon nature EMD, we are also unable to make meaningful conclusions about specific individual cytogenetic subtypes i.e. t(8:21) or MLL rearrangements, and more uncommon sites of EMD such as testicular involvement. Molecular genetics in AML is a rapidly evolving field and the CIBMTR dataset for AML is limited by lack of uniform molecular characterization of cases. For example, nucleophosmin mutations in cytogenetically normal AML confer a favorable prognosis and have been identified in 15% of isolated myeloid sarcomas though aberrant cytoplasmic localization of the protein by immunohistochemistry.17

Based on our analysis of the CIBMTR, we found that the presence of EMD is not an independent risk factor for relapse, DFS, or OS in patients undergoing alloHCT. Furthermore, the outcome of patients with EMD was not influenced by the location, timing of EMD, or intensity of conditioning regimen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would also like to acknowledge the following contributing co-authors for their contributions to this manuscript: Kirk R. Schultz, Mark R. Litzow, Philip L. McCarthy, Mahmoud D. Aljurf, Mitchell S. Cairo, William A. Wood, Celalettin Ustun, Thomas R. Klumpp, Edwin M. Horwitz, Jyotishankar Raychaudhuri, Bruce M. Camitta, Yi-Bin Chen, Peter H. Wiernik, Tsiporah B. Shore, Selina M. Luger, Ashish Bajel, Harry C. Schouten, Grace H. Ku, Maxim Norkin, Faiz Anwer, Asmita Mishra, Attaphol Pawarode, Amelia Langston, Mitchell Sabloff, Ann E. Woolfrey, Hans-Jochem Kolb, Edmund K. Waller, Usama Gergis, John Koreth, Reinhold Munker, Joseph McGuirk, William R. Drobyski, Bita Jalilizeinali, and H. Jean Khoury.

Geoffrey L. Uy’s contribution is supported by NCI grant K23 CA140707.

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-12-1-0142 and N00014-13-1-0039 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from * Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; * Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; * Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; * Celgene Corporation; Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; * Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.;* Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac GmbH; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; * Milliman USA, Inc.; * Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; * Remedy Informatics; * Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; * Tarix Pharmaceuticals; * TerumoBCT; * Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; * THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Minnesota; University of Utah; and * Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Corporate Members

Presented in part at the 2014 BMT Tandem Meetings, Grapevine, TX, March 2, 2014

Conflict-of-Interest Statement: The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary information is available at BMT’s website.

References

- 1.Byrd JC, Edenfield WJ, Shields DJ, Dawson NA. Extramedullary myeloid cell tumors in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: a clinical review. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(7):1800–1816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.7.1800. e-pub ahead of print 1995/07/01; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang H, Brandwein J, Yi QL, Chun K, Patterson B, Brien B. Extramedullary infiltrates of AML are associated with CD56 expression, 11q23 abnormalities and inferior clinical outcome. Leuk Res. 2004;28(10):1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.01.006. e-pub ahead of print 2004/08/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd JC, Weiss RB, Arthur DC, Lawrence D, Baer MR, Davey F, et al. Extramedullary leukemia adversely affects hematologic complete remission rate and overall survival in patients with t(8;21)(q22;q22): results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(2):466–475. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.466. e-pub ahead of print 1997/02/01; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu H, Saitoh T, Hatsumi N, Takada S, Yokohama A, Handa H, et al. Clinical significance of granulocytic sarcoma in adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(8):1513–1517. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02324.x. e-pub ahead of print 2012/05/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chevallier P, Mohty M, Lioure B, Michel G, Contentin N, Deconinck E, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for myeloid sarcoma: a retrospective study from the SFGM-TC. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(30):4940–4943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6315. e-pub ahead of print 2008/07/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris AC, Kitko CL, Couriel DR, Braun TM, Choi SW, Magenau J, et al. Extramedullary relapse of acute myeloid leukemia following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: incidence, risk factors and outcomes. Haematologica. 2013;98(2):179–184. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.073189. e-pub ahead of print 2012/10/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craddock C, Nagra S, Peniket A, Brookes C, Buckley L, Nikolousis E, et al. Factors predicting long-term survival after T-cell depleted reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2010;95(6):989–995. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.013920. e-pub ahead of print 2009/12/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid C, Schleuning M, Schwerdtfeger R, Hertenstein B, Mischak-Weissinger E, Bunjes D, et al. Long-term survival in refractory acute myeloid leukemia after sequential treatment with chemotherapy and reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108(3):1092–1099. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4165. e-pub ahead of print 2006/03/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee KH, Lee JH, Choi SJ, Kim S, Seol M, Lee YS, et al. Bone marrow vs extramedullary relapse of acute leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: risk factors and clinical course. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32(8):835–842. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704223. e-pub ahead of print 2003/10/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kogut N, Tsai NC, Thomas SH, Palmer J, Paris T, Murata-Collins J, et al. Extramedullary relapse following reduced intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant for adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(3):665–668. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.720375. e-pub ahead of print 2012/08/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96(13):4075–4083. e-pub ahead of print 2000/12/09. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giralt S, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Bacigalupo A, Horowitz M, Pasquini M, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimen workshop: defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(3):367–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.497. e-pub ahead of print 2009/02/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champlin R, Khouri I, Shimoni A, Gajewski J, Kornblau S, Molldrem J, et al. Harnessing graft-versus-malignancy: non-myeloablative preparative regimens for allogeneic haematopoietic transplantation, an evolving strategy for adoptive immunotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2000;111(1):18–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02196.x. e-pub ahead of print 2000/11/25; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. e-pub ahead of print 1999/04/16; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang M, Storer B, Estey E, Othus M, Zhang L, Sandmaier BM, et al. Outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia with monosomal karyotype who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;118(6):1490–1494. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339721. e-pub ahead of print 2011/06/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunet S, Labopin M, Esteve J, Cornelissen J, Socie G, Iori AP, et al. Impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication on the outcome of related and unrelated hematopoietic transplantation for adult acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 (7):735–741. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9868. e-pub ahead of print 2012/02/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falini B, Lenze D, Hasserjian R, Coupland S, Jaehne D, Soupir C, et al. Cytoplasmic mutated nucleophosmin (NPM) defines the molecular status of a significant fraction of myeloid sarcomas. Leukemia. 2007;21(7):1566–1570. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404699. e-pub ahead of print 2007/04/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.