Increasing numbers of Aboriginal youth in Northern Ontario are killing themselves, and 42% of the suicides over the last 10 years have occurred in just seven communities, says an anthropologist who has reviewed statistics from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario.

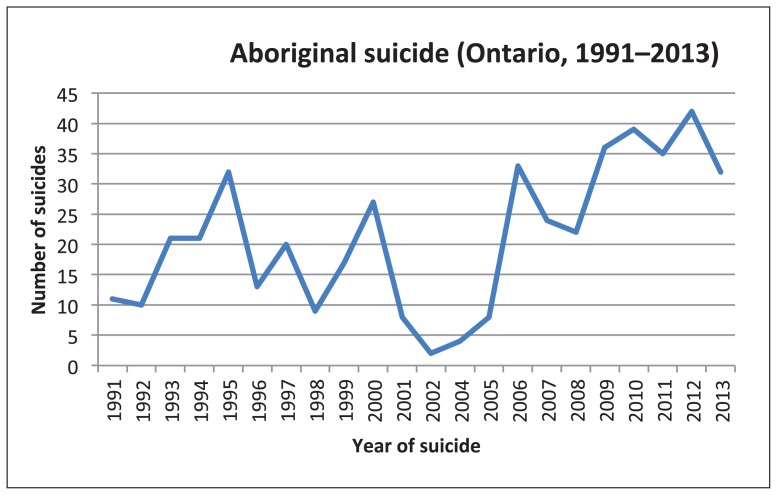

In 2013, there were 31 suicides by Aboriginal people in Ontario, up from 11 in 1991, said Gerald McKinley, a postdoctoral fellow at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Overall, from 1991 to 2013, there were 468 suicides by Aboriginal people in Ontario, almost half by people 25 or younger, he added.

McKinley has been able to analyze the figures only because the coroner’s office breaks out those suicides in Ontario, unlike in most other provinces. Although Health Canada cites the Aboriginal youth suicide rate as up to seven times higher than that for non-Aboriginal youth, there are no Aboriginal-specific rates per 100 000 for each province.

Those figures would help in creating a national suicide prevention strategy with a targeted indigenous component, which suicide prevention experts say is critical for bringing rates down in Canada.

McKinley points to historical trauma as part of the reason behind the escalating numbers. “We talk about things like historical trauma as if it’s events that have happened in the past,” McKinley told CMAJ in an interview. “But the number of suicide completions [is] increasing steadily, decade over decade over decade. What’s happening [now] is new communities are joining in.”

The effects of historical intergenerational trauma was the topic of a panel at the International Association for Suicide Prevention’s annual conference in Montréal on June 18 and a major focus of the recent recommendations by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Both the commission and the conference were clear that intergenerational trauma experienced by people whose family members attended residential schools is linked to suicide.

In 2013, there were 31 suicides by Aboriginal people in Ontario, up from 11 in 1991 (McKinley and Islam, 2015 [forthcoming]).

Image courtesy of Gerald McKinley

First Nations youth who had parents or grandparents at residential schools are more likely to experience depression, suicidal ideation and to attempt suicide than Aboriginal peers whose parents and grandparents did not attend those schools, says Amy Bombay, an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Dalhousie in Halifax.

Bombay analyzed the responses of youth aged 12–17 in the First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10, conducted by the First Nations Information Governance Centre in 250 communities across Canada. They describe it as the only First Nations–governed, national health survey in Canada.

“Early-onset depression is also associated with a greater likelihood of a suicide attempt throughout life,” Bombay says. Her findings emphasize the importance of intervening with the children and grandchildren of residential survivors early — and checking on their parents’ health, she told CMAJ in an interview.

“Suicide is preventable,” says Brian Mishara, the director of the Centre for Research and Intervention on Suicide and Euthanasia and a psychology professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal. “The tragedy is the incredibly high suicide rates among native people in Canada and that’s something which does not appear to be improving.”

Clusters of three to five youths in a community who complete suicide within months of each other drive the increasing rates in Ontario, McKinley says. “Similarities in method, geographic distribution and age completion make concerns over the idea of suicide as a contagion legitimate and worth considering.”

Since 2004, Ontario’s coroner has also tracked communities where the suicides take place. That’s how McKinley knows that 23.5% of the province’s Aboriginal suicides occurred in Pikangikum, a fly-in reserve north of Red Lake, where sniffing gas among children and youth is a persistent tragedy.

McKinley works with the Marten Falls First Nation, a remote community north of Thunder Bay. Together, McKinley and community members are trying to understand why there have been no suicides in Marten Falls, which shares the same difficult social conditions as neighbouring communities where people have taken their lives.

Most First Nations in Northern Ontario have few or no suicides, McKinley says. The critical factor for suicide prevention among youth is to understand why it is spreading to communities that have rarely experienced it.

“It’s also important to point out that suicide is not a tradition for the Anishnawbe with whom I work. It’s a direct result of a system created by colonialism and racism,” he said.

Successful suicide prevention requires identifying communities most at risk to understand how youth see themselves and their future, McKinley said. Then it requires working with the communities on community-owned programs to rebuild positive support networks for youth, he says.

The current system of flying people out of remote communities for limited courses of mental health treatment “is not going to save people,” McKinley says.