Abstract

AIM: To propose an allocation system of patients with liver cirrhosis to intensive care unit (ICU), and developed a decision tool for clinical practice.

METHODS: A systematic review of the literature was performed in PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. The search includes studies on hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and organ failure, or acute on chronic liver failure and/or intensive care therapy.

RESULTS: The initial search identified 660 potentially relevant articles. Ultimately, five articles were selected; two cohort studies and three reviews were found eligible. The literature on this topic is scarce and no studies specifically address allocation of patients with liver cirrhosis to ICU. Throughout the literature, there is consensus that selection criteria for ICU admission should be developed and validated for this group of patients and multidisciplinary approach is mandatory. Based on current available data we developed an algorithm, to determine if a patient is candidate to intensive care if needed, based on three scoring systems: premorbid Child-Pugh Score, Model of End stage Liver Disease score and the liver specific Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score.

CONCLUSION: There are no established systems for allocation of patients with liver cirrhosis to the ICU and no evidence-based recommendations can be made.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Failure, Intensive care, Allocation, Treatment

Core tip: The literature regarding allocation of cirrhotic patients to intensive care unit (ICU) is very limited and no studies have proposed and tested any specific allocation criteria. Thus it still remains to be determined, which cirrhotic patients will benefit from intensive care treatment, and if so, when during admission they should be transferred to the ICU, and when intensive treatment is futile and should be withheld. We propose an allocation system for clinical practice, based on internationally validated scoring systems.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of liver cirrhosis is increasing[1,2]. In the western world liver cirrhosis is mainly related to the increasing burden of alcohol-related liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and currently also hepatitis C, in the eastern world hepatitis B is a main cause. Patients with liver cirrhosis are prone to a progressive deterioration with the occurrence of portal hypertension and hepatic failure leading to end-stage liver disease and the development of complications. Furthermore, a large group (up to 75%) of patients are first diagnosed with liver cirrhosis, when experiencing their first episode of decompensation, and thus these patients represents a large hidden burden of the disease[3]. Patients with advanced liver cirrhosis, frequently require admission to intensive care unit (ICU)[4], mainly for various complications of advanced liver disease (i.e., sepsis, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, hepato-renal syndrome). These complications are associated with high risk of organ failures and a high mortality. Patients with cirrhosis presenting with acute hepatic deterioration and progressive organ failure represent the, now well described, syndrome acute-on-chronic-liver failure (ACLF)[5,6]. The Chronic Liver Failure (CLIF) ACLF in cirrhosis (CANONIC) study investigators of the European Association for the Study of the Liver - Chronic Liver Failure Consortium (EASL-CLIF) originally introduced the concept of ACLF: “ACLF is based on the presence of three major characteristics of the syndrome; acute decompensation, organ failure [predefined by the Clif Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score] and high 28-d mortality rate[6]”. Since ACLF affects approximately 30% of hospitalised cirrhotic patients, ACLF is the most frequent indication for admission to the ICU[4,5]. However, the mortality among patients admitted to the ICU with ACLF is high[7]. Consequently, clinical awareness on identification of cirrhotic patients at risk of developing organ failure, who will benefit from early intensive care treatment, is of great importance. The mortality among patients admitted to the ICU with ACLF ranges between 35%-93%[2,5,7]. Patients requiring mechanical ventilation are high-risk patients with poor long-term survival with a 1-year mortality rate of 89%[8]. Kavli et al[7] have shown that among patients with clinical or histological diagnosed alcoholic liver cirrhosis, in need for intensive care treatment, the 90-d mortality reaches levels of up to 93%, dependent on the degree of organ system failure[7]. Due to the poor prognosis the utilization of organ support in the ICU for these patients is often questioned. The treatment of patients with ACLF, not eligible for liver transplantation, is complicated and must be managed with therapies, which require a highly specialized team and close collaboration between hepatologists and intensive care specialists. There is a need for clinical tools and a proper triage to guide the physicians in decision making regarding the allocation of patients with ACLF to ICU, admitting only patients who would likely benefit from intensive care treatment[7]. In this study we aimed to perform a systematic review regarding allocation of patients with liver cirrhosis to intensive care, and to propose a decision tool for clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An electronic search was performed in PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE. Studies were included in the search irrespective of blinding, publication status, or language, and manual searches including scanning of reference lists in relevant articles and conference proceedings was also performed. All studies responding to the issue of this article were eligible for analysis, including previous reviews.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

The present systematic search includes studies on hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and organ failure or acute on CLIF and/or intensive care therapy.

Search methods for identification of studies

String 1: “liver cirrhosis” or “hepatic cirrhosis”; String 2: “liver failure” or “hepatic failure”; String 3: “intensive care” or “intensive treatment” or “intensive therapy” or “critical care”.

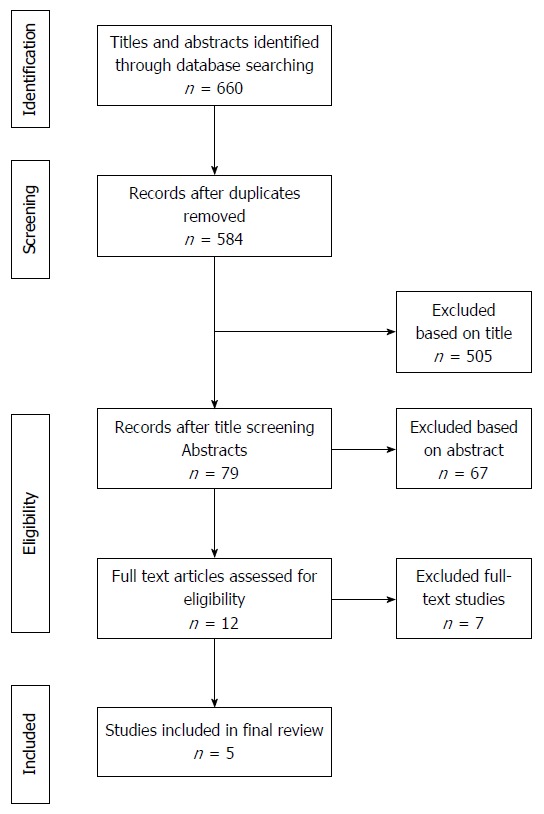

Potentially eligible studies were listed and evaluated. After reading the titles and abstracts, clearly irrelevant trials were excluded. Afterwards relevant full text studies were evaluated, and the eligible studies were selected (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of trials. Flowchart of search string.

RESULTS

The initial search identified 660 articles, 402 articles were indexed in PubMed, and 258 indexed in EMBASE. After duplicates were removed 584 articles, were evaluated for relevance.

During the initial title screening process 505 articles where evaluated by title of the first author, and found not relevant for the specific topic of this article, and therby excluded from the study. Further 67 articles were excluded after reading the abstracts, leaving 12 potentially relevant articles to be evaluated in full text together with a review of references in these articles. Ultimately, five articles were selected; two cohort studies and three reviews were found in the systematic search to be eligible for the present review (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the main findings of the included studies.

Table 1.

Included trials/studies

| Author, year, location, study design | Main target of the study | Patient population | Scores | Allocation system | In hospital mortality | ICU mortality |

| Kavli et al[7], 2012, Denmark, cohort study | This study investigated the severity of organ failure, and the frequency and outcome of withholding therapy in patients with advanced alcoholic liver cirrhosis admitted to a Scandinavian ICU | 87 adult patients with clinical or histological diagnosis of liver cirrhosis admitted to ICU at a University hospital in Denmark, within a 3 years period from January 2007-January 2010 | APACHE II, SAPS II, and SOFA were better at predicting mortality than Child-Pugh score | No specific allocation system is proposed | Only ICU data | With 3 or more organ failures the ICU mortality was > 90% |

| Shawcross et al[1], 2012, United Kingdom, cohort study | The aim of this study was to prospectively study the resource allocation and cost of a large cohort of patients with cirrhosis and one or more extrahepatic organ failure(s) | 563 patients were admitted to the Liver ICU at King’s College Hospital, between 2000 and 2007 | The median (IQR) for all patients admitted and surviving for > 8 h on day 1 (n = 548) was Child-Pugh score 12 (11-13), MELD 25 (14-34), APACHE II 22 (16-28) and SOFA 11 (8-13) | No specific allocation system is proposed | Overall hospital mortality of 59% (330/563) | 256/563 (51%) patients died whilst in the Liver ICU |

| Patients with cirrhosis admitted to ICU require high levels of organ support but ICU admission is not necessarily futile | ||||||

| Ginès et al[9], 2012, Spain, review | This review focuses on the diagnostic approach and treatment strategies cur-rently recommended in the critical care management of patients with cirrhosis | None | MELD and Child-Pugh scores have important limitations in the establishment of prognosis in critically ill cirrhotic patients | Encephalopatic cirrhotic patients (grade 3 or 4 hepatic encephalopathy) require ICU admission and intubation | Hospital mortality rates in patients with 1, 2 or 3 organ/system failures were 48%, 65%, and 70%, respectively | ICU and 6-mo mortality rates of 41% and 62%, respectively |

| Patients with a low MELD score (< 15), should be immediately considered for ICU. Contrary, in patients with end-stage cirrhosis (MELD > 30), 3 or more organ failures, and no perspective of transplantation, aggressive management is questionable | 59% of cirrhotic patients placed on mechanical ventilation died during their stay in the ICU | |||||

| Berry et al[10], 2013, United Kingdom, review | This review focuses on patients with cirrhosis, especially survival analysis and prognostic models | Child-Pugh score does not perform as well as general critical illness scoring systems | No specific allocation system is proposed | Greater than 60% | ICU mortality of up to 65%, rising to 90% with sepsis, if more than 1 d of respiratory support and renal support were required | |

| The MELD score performs better than the Child-Pugh score, yet the SOFA score is superior to both Child-Pugh and MELD score | Early aggressive approach to organ support is justified | |||||

| Saliba et al[11], 2013, France, review | This review focuses on prognostic scores and admission to ICU for critically ill cirrhotic patients | None | Suggests that ICU scores (SOFA, APACHE II, SAPS II) predict the outcome of cirrhotic patients admitted to the ICU better than liver scores (MELD and Child-Pugh) | No specific allocation system is proposed | Only ICU data | Ranges between 34%-69% |

| The persistence after ICU admission of three or more organ failures and the need for three or more organ supports, may lead to consider a limitation in life sustaining treatments, as a fatal outcome is almost constant |

Included studies of the present review. The table describes the included studies. ICU: Intensive care unit; SOFA score: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score; MELD: Model of End-stage Liver Disease.

Cohort studies

Kavli et al[7] performed a retrospective cohort study including 87 patients admitted to an ICU, at a university hospital with primary and secondary referrals. They found that increasing numbers of organ failures, correlate with increased mortality in critically ill patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Interestingly they found that in patients with 3 or more organ failures the ICU mortality was > 90% (Table 1). Furthermore, they found the prognostic scores specific for critical illness to be superior at predicting outcome compared to the liver-specific Child-Pugh score.

Shawcross et al[1] performed a prospective analysis of 563 patients admitted to a liver ICU with diagnosis of cirrhosis and dysfunction of one or more extrahepatic organ(s). They assessed resource utilization and found that presence of organ failure resulted in considerable resource expenditure in patients with liver cirrhosis, but had hospital mortality of 59% as illustrated in Table 1.

Reviews

Ginès et al[9] performed a review with focus on the diagnostic approach and the currently recommended treatment strategy of critically ill cirrhotic patients. They report no new data, and no methods section is described. However, they describe that several studies have shown that relatively good results can be obtained in selected critically ill cirrhotic patients, and therefore reluctance to refer these patients to the ICU should be balanced. They suggest that patients with a low Model of End-stage Liver Disease (MELD score) (< 15) should be immediately considered for ICU. Contrary, in patients with end-stage cirrhosis (MELD > 30), 3 or more organ failures, and no perspective of transplantation, aggressive management is questionable.

Berry et al[10] performed a review within the field of cirrhotic patients and allocation to ICU. They reported no new data, and the methods section was sparsely described. They suggest that an aggressive approach to organ support is justified, and that further discussions between hepatologists and intensive care specialists are required to determine acceptable burden-to-benefit ratios for prolonged intensive care support in young alcoholic patients.

Saliba et al[11] performed a review within the field of cirrhotic patients and allocation to ICU. They reported no new data, and no methods section was described. However, they claimed that general ICU prognostic scores [SOFA score, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and SAPS II] predicted mortality better than liver specific scores (MELD and Child-Pugh score) in cirrhotic patients, once admitted to the ICU. Furthermore, ICU and liver scores predicted outcome more precisely once they were re-evaluated at day 3 from admission. The authors stated that patients should be referred from the hepatology ward to the ICU at an earlier stage of decompensation, and a multidisciplinary approach between hepatologists, intensive care specialists, and also transplant surgeons should be mandatory.

Scoring systems

A number of score systems have been developed to assess the prognosis of critically ill cirrhotic patients, see Table 2[2,12-35]. The liver specific scores have mainly focused on the general prognosis of cirrhotic patients, whereas the general scores, such as APACHE score, and SOFA score, were developed to predict outcome in the general population admitted to the ICU[5,14,20]. Numerous organ-failure scores have been developed to evaluate the prognosis depending on the number of organ failures, however, only a limited number of score systems have been established in clinical practice. To assess severity and prognosis due to underlying liver disease before ACLF or acute hospitalization, Child-Pugh score and MELD score are the best-validated scores[14]. The World Health Organization (WHO) performance status (PS) is also useful to grade general well-being and activities of daily life.

Table 2.

Scoring systems to predict mortality

| Score | Target | Number of studies | AUCROC range (min-max) |

| Child-Pugh | Prognostic1 | 14 | 0.71-0.87 |

| MELD | Prognostic1 | 8 | 0.77-0.93 |

| RFH | Prognostic1 | 1 | 0.79 |

| SOFA | Organ failure2 | 11 | 0.81-0.95 |

| APACHE II | Prognostic in ICU3 | 9 | 0.66-0.83 |

| APACHE III | Prognostic in ICU3 | 4 | 0.78-0.91 |

Prognostic: score used to assess the prognosis of chronic liver disease;

Organ failure: score with the objective to evaluate the degree of organ failure;

Prognostic in ICU: severity of disease classification score. The table describes the performance of the presented scoring systems[17,19-35]. AUROC: Areal Under the Reciever Operating Curve; Range (min-max) describing the minimum and maximum reported AUC for the given score, based on published trials[17,19-35]. ICU: Intensive care unit; MELD: Model of End-stage Liver Disease; RFH: Royal Free Hospital Score; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score; APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation.

The prognostic liver specific score named Child-Pugh score (Table 3) contains five components; grade of hepatic encephalopathy, presence of ascites, serum-bilirubin, serum-albumin, and the international normalized ratio for prothrombin time (INR)[36].

Table 3.

Child-Pugh score

| Measure | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points |

| Total billirubin (μmol/L) | < 34 (< 1.9 mg/dL) | 34-50 (< 1.9-2.9 mg/dL) | > 50 (> 2.9 mg/dL) |

| S-Albumin (g/L) | > 35 | 28-35 | < 28 |

| PT INR | < 1.70 | 1.71-2.30 | > 2.30 |

| Ascites | None | Mild | Moderate/severe |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | None | Grade I-II | Grade III-IV |

| Points | Class | One year survival | Two year survival |

| 5-6 | A | 100% | 85% |

| 7-9 | B | 81% | 57% |

| 10-15 | C | 45% | 35% |

Child-Pugh Score and associated one- and two-year survival.

Child Pugh score

The Child-Pugh score has been well established in clinical practice for decades. It contains a limited number of variables, is simply calculated, and is easily interpreted. The score is a simple method for determining the prognosis of patients with cirrhosis[15]. However, the Child-Pugh score does not take factors such as cardiovascular, renal, and pulmonary dysfunction into account, consequently it does not offer valid information to predict mortality in cirrhotic patients who have organ failure[14]. Further, the assessment of hepatic encephalopathy and presence of ascites are subjective measures and prone to observer variation.

MELD score

The MELD score is a scoring system for assessing the severity of chronic liver disease. The MELD Score ranges from 6 (less sick) to 40 (very sick) and the formula is based on the natural logarithm of serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, the INR for prothrombin time, and information regarding dialysis[37].

The MELD Score formula: [0.957 × ln[serum creatinin] + 0.378 × ln[serum bilirubin] + 1.120 × ln[INR] + 0.643] × 10 (if hemodialysis, value for Creatinine is automatically set to 4.0).

Serum bilirubin is a blood sample that reflects the liver function. (Reference interval: 5-25 μmol/L). The INR reflects the ability of the liver to produce proteins; more specifically the clotting factors that contribute to the coagulation process (Reference interval: 0.8-1.2 is normal, higher is abnormal). Creatinine is a blood sample that reflects the function of the kidneys. (Reference interval: 60-105 μmol/L).

The MELD score is widely used to quantify end-stage liver disease in patients listed for liver transplantation[15], and has been repeatedly shown to be equivalent or even superior to the Child-Pugh score to estimate short-term survival among cirrhotic patients[14]. An additional advantage of MELD is the exclusion of subjective measures.

WHO performance score

The performance score was originally introduced in the treatment of cancer patients, as an attempt to quantify cancer patients’ general well-being and activities of daily life (Table 4)[38]. The score is widely used in other medical conditions as a simple measure of general condition, functional ability and quality of life.

Table 4.

World Health Organization performance score

| Grade | WHO Performance score |

| 0 | Fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction |

| 1 | Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature, e.g., light house work, office work |

| 2 | Ambulatory and capable of all selfcare but unable to carry out any work activities. Up and about more than 50% of waking hours |

| 3 | Capable of only limited selfcare, confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours |

| 4 | Completely disabled. Cannot carry on any selfcare, totally confined to bed or chair |

| 5 | Dead |

WHO: World Health Organization.

APACHE scores

The APACHE score is one of several ICU scoring systems. The score is a severity-of-disease classification system, based on 12 physiological parameters; 1, alveolar-arterial O2 tension difference (AaDO2) or arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) (depending on the fraction of inspired oxygen); 2, temperature (rectal); 3, mean arterial pressure; 4, arterial pH; 5, heart rate;, 6, respiratory rate; 7, sodium (serum); 8, potassium (serum); 9, Creatinine; 10,. Haematocrit; 11, white blood cell count; and 12; Glasgow Coma Scale. The score is applied within 24 h of admission to the ICU, the higher the score, the higher risk of death[15]. Compared to Child-Pugh scores it has been shown in numerous studies to be more powerful in predicting hospital mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. Wehler et al[39] found an areal under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) of 0.79 for the APACHE II score, compared to Child-Pugh with an AUROC of 0.73, other studies have found similar results[24-26,28].

SOFA Score and CLIF-SOFA

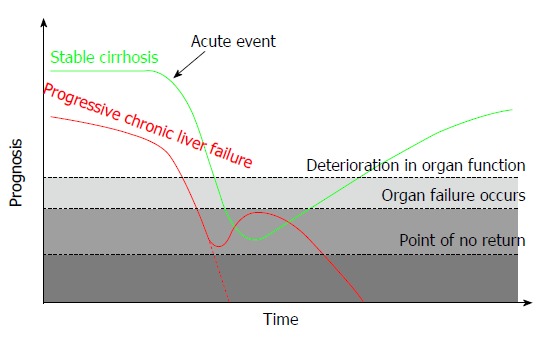

The SOFA score was developed as a simple prognostic score to evaluate the degree of organ failure in patients in the general ICU[2,29]. The score contains information on degree of failure regarding liver, kidney, brain, coagulation, circulation and lungs, graded from 0-4 (Table 5). The CLIF-SOFA score is a modified version of the original SOFA score, a newly developed scoring system exclusively for patients with end-stage liver disease, and it accommodates a lower threshold for serum creatinine, because minor increases in s-creatinine levels in cirrhotic patients indicate marked reductions in glomerular filtration rate. Furthermore, it uses the INR instead of platelets as a marker of coagulaopathy, increases the threshold for bilirubin to achieve organ failure, and uses grades of hepatic encephalopathy from the West Haven score as opposed to Glasgow Coma Scale for neurologic failure[2,6]. Organ failure in the CLIF SOFA score is defined as; liver failure: bilirubin > 205 μmol/L, kidney failure: creatinine > 177 μmol/L or requiring renal replacement therapy, neurologic failure: hepatic encephalopathy grade 3 or 4, coagulation failure: INR > 2.5, and circulation failure: requiring vasopressors to maintain adequate mean arterial pressure (MAP). The CLIF-SOFA score can be translated into a degree of ACLF[6,40] (Figure 2, Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score

| Organ | Variabel | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Liver | Billirubin, μmol/L | < 20 μmol/L | ≥ 20 to < 34 μmol/L | ≥ 34 to < 103 μmol/L | ≥ 103 to < 205 μmol/L | > 205 μmol/L |

| (mg/dL) | (-1.1) | (≥ 1.1 to < 1.9 ) | (≥ 1.9 to < 6.0) | (≥ 6.0 to < 11.9) | (> 11.9)1 | |

| Kidney | Creatinine, μmol/L | < 106 μmol/L | ≥ 106 to < 177 μmol/L | ≥ 177 to < 309 μmol/L | ≥ 309 to < 442 μmol/L | > 442 μmol/L |

| (mg/dL) | (< 1.2) | (≥ 1.2 to < 2.0) | (≥ 1.2 to < 3.5)1 | (≥ 3.5 to < 5)1 | (> 5.0)1 | |

| Or renal replacement therapy1 | ||||||

| CNS | HE grade | None | I | II | III1 | IV1 |

| Coagulation | INR | < 1.1 | ≥ 1.1 to 1.25 | ≥ 1.25 to < 1.5 | ≥ 1.5 to < 2.5 | ≥ 2.5 or platlets < 201 |

| Circulation | MAP (mmHg) | ≥ 70 | < 70 | Dopamine ≤ 51 | Dopamine > 51 | Dopamine > 15 |

| Dobutamine | Epinephrine ≤ 0.11 | Epinephrine > 0.1 | ||||

| Terlipressin1 | Norepinephrine ≤ 0.11 | Norepinephrine > 0.11 | ||||

| Lungs | PaO2/FiO2 | > 400 | > 300 to ≤ 400 | > 200 to ≤ 300 | > 100 to ≤ 2001 | ≤ 1001 |

| SpO2/FiO2 | > 512 | > 357 to ≤ 512 | > 214 to < 357 | > 89 to ≤ 2141 | ≤ 891 | |

Indicates the limit for the definition of organ failure. HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; MAP: Mean arterial pressure; PaO2: Arterial oxygen tension; FiO2: Fraction of inspired oxygen; SpO2: Peripheral capillary oxygen saturation.

Figure 2.

Acute on Chronic Liver Failure. The green line illustrates a patient with stable cirrhosis (i.e., Child-Pugh class A/B) developing acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF). The red line illustrates a patient with progressive chronic liver failure (i.e., a patients with Child C cirrhosis and refractory ascites) developing ACLF. The Y-axis (Prognosis) is based on Child Pugh score or MELD score and the performance status before ACLF develops and CLIF-SOFA score after ACLF. The threshold “deterioration in organ function” represents a level with i.e. increase in creatinine or oxygen demand without organ failure. The threshold “organ failure” is as defined in the CLIF-SOFA score and “point of no return” is a state of multiorgan failure without reversibility.

Table 6.

Degree of Acute on Chronic Liver Failure and the associated mortality

| ACLF | Numbers of organ failure | 28-d mortality | 90-d mortality |

| 0 | 0 or 1 (/kidney) | 4.7% | 15.0% |

| 1 | 1 (no kidney dysfunction) | 22.1% | 40.7% |

| 2 | 2 | 32.0% | 52.3% |

| 3 | ≥ 3 | 76.7% | 79.1% |

ACLF: Acute on Chronic Liver Failure.

Royal Free Hospital score

The Royal Free Hospital (RFH) score is a novel prognostic model for critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Parameters included in the score are bilirubin, INR, lactate, urea, A-a gradient, and variceal bleeding. Theocharidou et al[18], found the RFH score to have good discriminative power, equally to the CLIF-SOFA and SOFA score, however, the score remains to be externally validated, to confirm the clinical utility.

DISCUSSION

The decision-making regarding allocation of cirrhotic patients to ICU remains a great interdisciplinary challenge in daily clinical practice. The literature is scarce and no studies specifically address this issue. There is general consensus that selection criteria for ICU admission candidates should be developed and validated for this group of patients and multidisciplinary approach is mandatory. However, all together the general approach throughout the literature is somewhat indefinable. It still remains to be determined, which cirrhotic patients will benefit from intensive care treatment, and if so, when during admission they should be transferred to the ICU, and contrary when intensive treatment is futile and should be withheld.

It has been known for more than 40 years that surgical procedures on cirrhotic patients is associated with increased risk[35], and for cirrhotic patients (child-pugh C) who undergo nontransplant surgical procedures, mortality rates of up to 76% have been reported[41]. Furthermore it is known that the mortality rate is markedly increased for emergency surgery (57%) compared to elective surgery (10%)[42]. Higher risk of infection, coagulopathy and malnutrition may be important factors[43-47]. In addition many cirrhotic patients decompensate in the postoperative phase and develop hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, hepato-renal syndrome or infections[44,45,47,48]. Reduced perfusion of the liver and altered response to anaesthetics and other medications, may also be contributing factors[49,50]. It is therefore essential to assess the severity of the underlying liver disease and to perform preoperative optimisation, including treatment of coagulopathy, ascites, portal hypertension, malnutrition, any substance abuse problem and infections.

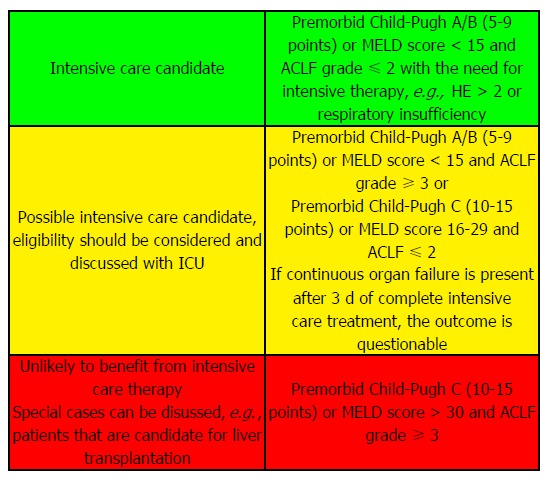

Based on current available data[5,6], we have developed an algorithm based on three scoring systems: Child-Pugh Score, MELD score and CLIF-SOFA score. In Figure 3 we suggest criteria to determine if a patient is a candidate to intensive care if needed. However, the algorithm remains to be validated in clinical practice.

Figure 3.

Proposal of a clinical system to identify candidates for intensive care if indicated. Algorithm based on three scoring systems: Child-Pugh Score, Model of End stage Liver Disease score (MELD) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (CLIF-SOFA). ACLF: Acute on chronic liver failure; ICU: Intensive care unit.

The exact time point when patients should be referred to intensive care may be difficult to identify and will likely depend on local clinical setup, i.e., access to intermediate care. However, the following general consideration can be used. Dialogue between physicians from the referring ward and ICU is mandatory and should be initiated at an early stage to assess if the patient is candidate to intensive care if needed and to ensure detection and treatment of organ failures as early as possible.

Close monitoring of progressive organ dysfunction in the ward is essential. Sometimes it may also be rational to transfer patients to the intermediate care/ICU to prevent occurrence of organ failure by close monitoring. Referral criteria should include the following: (1) Comatose patients not able to protect airways; (2) Respiratory failure with need of mechanical ventilation; (3) Circulatory failure with systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or low mean arterial pressure (MAP < 60 mmHg) despite adequate fluid supplementation and increasing lactate or increasing creatinine or reduced urine output; (4) necessity of vasopressors; and (5) septic shock or multi-organ failures.

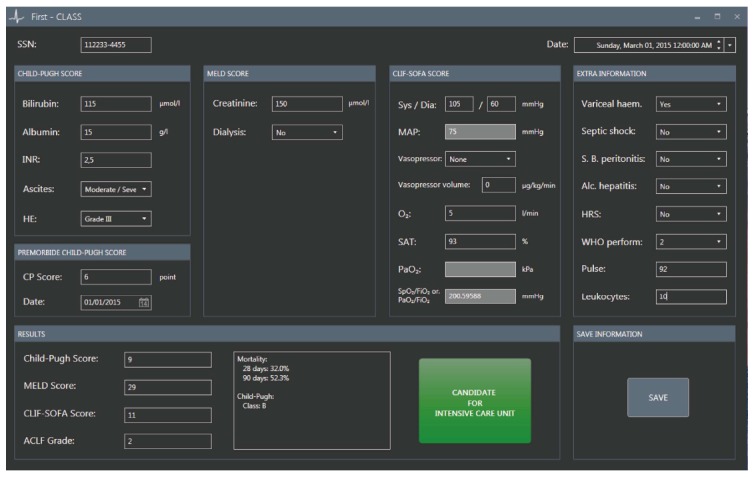

To help the daily registration of important values in patients with liver cirrhosis, we have developed a specific computer software program First Chronic Liver Allocation Scoring System (First-CLASS).

First-CLASS features an extensive data-gathering tool, with a user-friendly graphical interface, for the purpose of scoring acute on CLIF patients. An immediate score of the patient is calculated using the described algorithm, and it will be presented to the user. All data is saved to a database, which can be easily retrieved for both research and evaluation of specific patients. First-CLASS provides a program for viewing the data that has been collected in a meaningful way, such as using graphs for visualization of results in the given admission period. Furthermore the First-CLASS-Viewer program allows for exporting the data of patients to be used directly for statistical analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

First Chronic Liver Allocation Scoring system. Danish civil registration number, a unique 10-digit personal identification number assigned to every Danish citizen at birth since 1968. HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; CP Score: Child Pugh Score; MAP: Mean arterial pressure; SAT: Oxygen saturation (%); Varice Haemorr: Variceal haemorrhage; S.B. Peritonitis: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; Alko. Hepatitis: Alcoholic hepatitis; HRS: Hepato renal syndrome; WHO Perform: WHO performance status; ACLF grade: Acute on chronic liver failure grade; First-CLASS: First Chronic Liver Allocation Scoring System; SSN: Social Security Number.

In conclusion, we found that the literature regarding allocation of cirrhotic patients to ICU is very limited and no studies have proposed and tested any specific allocation criteria. Thus it still remains to be determined, which cirrhotic patients will benefit from intensive care treatment, and if so, when during admission they should be transferred to the ICU, and when intensive treatment is futile and should be withheld. Based on indirect evidence we have proposed a scoring system that can help identify which patients are candidates or not to ICU therapy, however the system needs validation.

COMMENTS

Background

Patients with liver cirrhosis are prone to a progressive disease course with the occurrence of portal hypertension and hepatic failure leading to end-stage disease and development of complications. Cirrhosis and organ failure is associated with a high mortality. Rational and timely allocation to an intensive care unit (ICU) is a challenge of clinical importance.

Research frontiers

The exact time point when patients should be referred to intensive care may be difficult to identify and will likely depend on local clinical setup, i.e., access to intermediate care. Close monitoring of progressive organ dysfunction in the ward is essential. Sometimes it may also be rational to transfer patients to the intermediate care/ICU to prevent occurrence of organ failure by close monitoring. Referral criteria should include the following: (1) Comatose patients not able to protect airways; (2) Respiratory failure with need of mechanical ventilation; (3) Circulatory failure with systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or low mean arterial pressure (MAP < 60 mmHg) despite adequate fluid supplementation and increasing lactate or increasing creatinine or reduced urine output; (4) necessity of vasopressors; and (5) septic shock or multi-organ failures.

Innovations and breakthroughs

To help the daily monitoring and registration of organfunctions in patients with liver cirrhosis, the authors have developed computer software program First Chronic Liver Allocation Scoring System (First-CLASS). First-CLASS features an extensive data-gathering tool, with a user-friendly graphical interface, for the purpose of scoring acute on chronic liver failure (CLIF) patients. An immediate score of the patient is calculated using the described algorithm, and it will be presented to the user.

Applications

It still remains to be determined, which cirrhotic patients will benefit from intensive care treatment, and if so, when during admission they should be transferred to the ICU, and when intensive treatment is futile and should be withheld. Based on indirect evidence, the authors have proposed a scoring system that can help identify which patients are candidates or not to ICU therapy, however the system needs validation.

Terminology

Patients with cirrhosis presenting with acute hepatic deterioration and progressive organ failure represent the, now well described, syndrome Acute-on-Chronic-Liver Failure (ACLF). The CLIF ACLF in cirrhosis study investigators of the European Association for the Study of the Liver - Chronic Liver Failure Consortium originally introduced the concept of ACLF: “ACLF is based on the presence of three major characteristics of the syndrome; acute decompensation, organ failure (predefined by the CLIF SOFA score) and high 28-d mortality rate”.

Peer-review

In this manuscript “Allocation of patients with liver cirrhosis and organ failure to intensive care: Systematic review and a proposal for clinical practice”, the authors aimed to perform a systematic review regarding allocation of patients with liver cirrhosis to ICU. They also proposed a scoring system to help identify the patients as candidates for ICU therapy. The subject matter of current study is of interest. This review may help clinicians chose the more suitable treatments.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Lindvig KP performed the systematic search and analyzed the data; Teisner AS and Krag A evaluated the systematic search; Lindvig KP and Krag A wrote the paper; Teisner AS, Kjeldsen J, Strøm T, Toft P and Furhmann V contributed equally to the writing process.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: February 10, 2015

First decision: March 28, 2015

Article in press: June 16, 2015

P- Reviewer: De Robertis R, Makhlouf NA, Zhao HT S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Shawcross DL, Austin MJ, Abeles RD, McPhail MJ, Yeoman AD, Taylor NJ, Portal AJ, Jamil K, Auzinger G, Sizer E, et al. The impact of organ dysfunction in cirrhosis: survival at a cost? J Hepatol. 2012;56:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McPhail MJ, Shawcross DL, Abeles RD, Chang A, Patel V, Lee GH, Abdulla M, Sizer E, Willars C, Auzinger G, et al. Increased Survival for Patients With Cirrhosis and Organ Failure in Liver Intensive Care and Validation of the Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Scoring System. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1353–1360.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dam Fialla A, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Touborg Lassen A. Incidence, etiology and mortality of cirrhosis: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:702–709. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.661759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Monescillo A, Arocena C, Valer P, Ginès P, Moreira V, Milicua JM, Jiménez W, Arroyo V. Circulatory function and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;42:439–447. doi: 10.1002/hep.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, Amoros A, Moreau R, Ginès P, Levesque E, Durand F, Angeli P, Caraceni P, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, Durand F, Gustot T, Saliba F, Domenicali M, Gerbes A, Wendon J, Alessandria C, Laleman W, Zeuzem S, Trebicka J, Bernardi M, Arroyo V; CANONIC Study Investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–1437, 1437.e1-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavli M, Strøm T, Carlsson M, Dahler-Eriksen B, Toft P. The outcome of critical illness in decompensated alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:987–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levesque E, Saliba F, Ichaï P, Samuel D. Outcome of patients with cirrhosis requiring mechanical ventilation in ICU. J Hepatol. 2014;60:570–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginès P, Fernández J, Durand F, Saliba F. Management of critically-ill cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S13–S24. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry PA, Thomson SJ, Rahman TM, Ala A. Review article: towards a considered and ethical approach to organ support in critically-ill patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:174–182. doi: 10.1111/apt.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saliba F, Ichai P, Levesque E, Samuel D. Cirrhotic patients in the ICU: prognostic markers and outcome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19:154–160. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835f0c17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boone MD, Celi LA, Ho BG, Pencina M, Curry MP, Lior Y, Talmor D, Novack V. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score predicts mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients. J Crit Care. 2014;29:881.e7–881.13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, Patch D, Shaw S, Hui C, Burroughs AK. Review article: scoring systems for assessing prognosis in critically ill adult cirrhotics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feltracco P, Brezzi M, Barbieri S, Milevoj M, Galligioni H, Cillo U, Zanus G, Vitale A, Ori C. Intensive care unit admission of decompensated cirrhotic patients: prognostic scoring systems. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:1079–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galbois A, Das V, Carbonell N, Guidet B. Prognostic scores for cirrhotic patients admitted to an intensive care unit: which consequences for liver transplantation? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karvellas CJ, Bagshaw SM. Advances in management and prognostication in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20:210–217. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai MH, Chen YC, Ho YP, Fang JT, Lien JM, Chiu CT, Liu NJ, Chen PC. Organ system failure scoring system can predict hospital mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:251–257. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200309000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theocharidou E, Pieri G, Mohammad AO, Cheung M, Cholongitas E, Agarwal B, Burroughs AK. The Royal Free Hospital score: a calibrated prognostic model for patients with cirrhosis admitted to intensive care unit. Comparison with current models and CLIF-SOFA score. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:554–562. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.López-Velázquez JA, Chávez-Tapia NC, Ponciano-Rodríguez G, Sánchez-Valle V, Caldwell SH, Uribe M, Méndez-Sánchez N. Bilirubin alone as a biomarker for short-term mortality in acute-on-chronic liver failure: an important prognostic indicator. Ann Hepatol. 2013;13:98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vazquez-Elizondo G, Carrillo-Esper R, Zamora-Valdés D, Méndez-Sánchez N. Mortality prediction of cirrhotic patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:78–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu KH, Jenq CC, Tsai MH, Hsu HH, Chang MY, Tian YC, Hung CC, Fang JT, Yang CW, Chen YC. Outcome scoring systems for short-term prognosis in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Shock. 2011;36:445–450. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31822fb7e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juneja D, Gopal PB, Kapoor D, Raya R, Sathyanarayanan M. Profile and outcome of patients with liver cirrhosis requiring mechanical ventilation. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27:373–378. doi: 10.1177/0885066611400277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cholongitas E, Betrosian A, Senzolo M, Shaw S, Patch D, Manousou P, O’Beirne J, Burroughs AK. Prognostic models in cirrhotics admitted to intensive care units better predict outcome when assessed at 48 h after admission. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1223–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YC, Tian YC, Liu NJ, Ho YP, Yang C, Chu YY, Chen PC, Fang JT, Hsu CW, Yang CW, et al. Prospective cohort study comparing sequential organ failure assessment and acute physiology, age, chronic health evaluation III scoring systems for hospital mortality prediction in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cholongitas E, Senzolo M, Patch D, Kwong K, Nikolopoulou V, Leandro G, Shaw S, Burroughs AK. Risk factors, sequential organ failure assessment and model for end-stage liver disease scores for predicting short term mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted to intensive care unit. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho YP, Chen YC, Yang C, Lien JM, Chu YY, Fang JT, Chiu CT, Chen PC, Tsai MH. Outcome prediction for critically ill cirrhotic patients: a comparison of APACHE II and Child-Pugh scoring systems. J Intensive Care Med. 2004;19:105–110. doi: 10.1177/0885066603261991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai MH, Peng YS, Lien JM, Weng HH, Ho YP, Yang C, Chu YY, Chen YC, Fang JT, Chiu CT, et al. Multiple organ system failure in critically ill cirrhotic patients. A comparison of two multiple organ dysfunction/failure scoring systems. Digestion. 2004;69:190–200. doi: 10.1159/000078789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YC, Tsai MH, Ho YP, Hsu CW, Lin HH, Fang JT, Huang CC, Chen PC. Comparison of the severity of illness scoring systems for critically ill cirrhotic patients with renal failure. Clin Nephrol. 2004;61:111–118. doi: 10.5414/cnp61111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das V, Boelle PY, Galbois A, Guidet B, Maury E, Carbonell N, Moreau R, Offenstadt G. Cirrhotic patients in the medical intensive care unit: early prognosis and long-term survival. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2108–2116. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f3dea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aggarwal A, Ong JP, Younossi ZM, Nelson DR, Hoffman-Hogg L, Arroliga AC. Predictors of mortality and resource utilization in cirrhotic patients admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2001;119:1489–1497. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabe C, Schmitz V, Paashaus M, Musch A, Zickermann H, Dumoulin FL, Sauerbruch T, Caselmann WH. Does intubation really equal death in cirrhotic patients? Factors influencing outcome in patients with liver cirrhosis requiring mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1564–1571. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karvellas CJ, Pink F, McPhail M, Austin M, Auzinger G, Bernal W, Sizer E, Kutsogiannis DJ, Eltringham I, Wendon JA. Bacteremia, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II and modified end stage liver disease are independent predictors of mortality in critically ill nontransplanted patients with acute on chronic liver failure. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:121–126. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b42a1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levesque E, Hoti E, Azoulay D, Ichaï P, Habouchi H, Castaing D, Samuel D, Saliba F. Prospective evaluation of the prognostic scores for cirrhotic patients admitted to an intensive care unit. J Hepatol. 2012;56:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cavallazzi R, Awe OO, Vasu TS, Hirani A, Vaid U, Leiby BE, Kraft WK, Kane GC. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score for predicting outcome in critically ill medical patients with liver cirrhosis. J Crit Care. 2012;27:424.e1–424.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray KF, Carithers RL. AASLD practice guidelines: Evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1407–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D’Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zubrod CG, Schneiderman M, Frei Iii E, Brindley C, Lennard Gold G, Shnider B, Oviedo R, Gorman J, Jones Jr R, Jonsson U, et al. Appraisal of methods for the study of chemotherapy of cancer in man: Comparative therapeutic trial of nitrogen mustard and triethylene thiophosphoramide. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1960;11:7–33. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wehler M, Kokoska J, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, Strauss R. Short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with cirrhosis assessed by prognostic scoring systems. Hepatology. 2001;34:255–261. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jalan R, Gines P, Olson JC, Mookerjee RP, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Arroyo V, Kamath PS. Acute-on chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1336–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Austin MJ, Shawcross DL. Outcome of patients with cirrhosis admitted to intensive care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:202–207. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f6a40d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrison RN, Cryer HM, Howard DA, Polk HC. Clarification of risk factors for abdominal operations in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Ann Surg. 1984;199:648–655. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198406000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Artinyan A, Marshall CL, Balentine CJ, Albo D, Orcutt ST, Awad SS, Berger DH, Anaya DA. Clinical outcomes of oncologic gastrointestinal resections in patients with cirrhosis. Cancer. 2012;118:3494–3500. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gholson CF, Provenza JM, Bacon BR. Hepatologic considerations in patients with parenchymal liver disease undergoing surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:487–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayashida N, Aoyagi S. Cardiac operations in cirrhotic patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;10:140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoetzel A, Ryan H, Schmidt R. Anesthetic considerations for the patient with liver disease. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2012;25:340–347. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283532b02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nicoll A. Surgical risk in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1569–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jepsen P, Sørensen HT, Vilstrup H, Ott P. [Surgical risk for patients with liver disease] Ugeskr Laeger. 2006;168:4299–4302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keegan MT, Plevak DJ. Preoperative assessment of the patient with liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2116–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedman LS. The risk of surgery in patients with liver disease. Hepatology. 1999;29:1617–1623. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]