Key Points

The multivariate mechanism of FeCl3-induced thrombosis is rooted in colloidal chemistry, mass transfer, and biological clotting.

FeCl3-induced thrombosis is mediated by charge-based binding of proteins (cell surface bound and soluble) to the Fe3+ ion.

Abstract

The mechanism of action of the widely used in vivo ferric chloride (FeCl3) thrombosis model remains poorly understood; although endothelial cell denudation is historically cited, a recent study refutes this and implicates a role for erythrocytes. Given the complexity of the in vivo environment, an in vitro reductionist approach is required to systematically isolate and analyze the biochemical, mass transfer, and biological phenomena that govern the system. To this end, we designed an “endothelial-ized” microfluidic device to introduce controlled FeCl3 concentrations to the molecular and cellular components of blood and vasculature. FeCl3 induces aggregation of all plasma proteins and blood cells, independent of endothelial cells, by colloidal chemistry principles: initial aggregation is due to binding of negatively charged blood components to positively charged iron, independent of biological receptor/ligand interactions. Full occlusion of the microchannel proceeds by conventional pathways, and can be attenuated by antithrombotic agents and loss-of-function proteins (as in IL4-R/Iba mice). As elevated FeCl3 concentrations overcome protective effects, the overlap between charge-based aggregation and clotting is a function of mass transfer. Our physiologically relevant in vitro system allows us to discern the multifaceted mechanism of FeCl3-induced thrombosis, thereby reconciling literature findings and cautioning researchers in using the FeCl3 model.

Introduction

In vivo animal models of thrombosis are used extensively to study clot formation and propagation, of which the ferric chloride (FeCl3) thrombosis model is the most commonly used. In this model, filter paper saturated with FeCl3 is applied to vessel adventitia of small mammals, typically mice, resulting in occlusive thrombosis.1-5 As the FeCl3 diffuses into the vascular space, clot formation is commonly monitored by Doppler flow and intravital microscopy. Although the FeCl3 injury model is popular due to ease of implementation and robust thrombus formation, the underlying mechanisms of FeCl3-induced clotting remain unclear.

Clot initiation in this model is historically attributed to free iron-induced denudation of endothelial cells and the subsequent exposure of the subendothelium that triggers platelet adhesion/aggregation and activation of the coagulation cascade.6 However, studies using mice deficient in collagen receptor glycoprotein VI have produced contradictory results, reporting both normal and altered thrombus formation.7,8 Eckly et al observed that although endothelial cells appear denuded and platelets are present in the occlusive thrombus, there is limited collagen exposure in the vessel.9 Furthermore, an elegantly designed scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis revealed that endothelial cells are not denuded, and surprisingly, that erythrocytes mediate the adherence of platelets to the endothelium by an unknown mechanism.10 In addition to the uncertain status of the endothelium, the effects of FeCl3 vary based on the vessel to which it is applied: in mice lacking the extracellular domain of glycoprotein Ibα (GPIbα), the FeCl3 model results in occlusion in mesenteric venules but not in the carotid artery.7,11 These inconsistencies, in conjunction with the wide range of published FeCl3 concentrations (10 mM-2 M; for percentage, see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site) and application times (1-20 minutes) used to elicit a clotting response, raise questions about the direct chemical effects of FeCl3 on blood components and the role that mass transfer plays in this thrombosis model.12

These questions inspired us to systematically investigate the mechanisms of FeCl3-induced thrombosis via an in vitro reductionist approach: interrogating the effect of FeCl3 on individual blood components in the presence and absence of endothelial cells. To this end, we designed a microfluidic device that enables precise control over FeCl3 influx while allowing for direct visualization and quantification of FeCl3-induced aggregation of isolated blood components. Our laboratory has shown that vascular phenomenon relevant to hematologic processes can be studied in vitro by culturing endothelial cells to a confluent monolayer in microchannels.13,14 These “endothelial-ized” microfluidics allow us to recapitulate the in vivo endothelium-blood-FeCl3 interface and monitor the status of the endothelium during FeCl3 application, while controlling the flow conditions and cellular and molecular “inputs” to the system. We find that all isolated blood components and molecules aggregate in a FeCl3 concentration-dependent manner, with and without endothelial cells. We therefore posit a novel 2-stage mechanism for the action of FeCl3 in thrombus formation. The first stage is based on colloidal chemistry principles whereby cells and plasma proteins adhere and aggregate due to the binding of negatively charged proteins to positively charged iron species. The extent of this stage is dependent on effective FeCl3 concentration, which is governed by intraluminal mass transport. In the second-stage, clot formation proceeds via platelet aggregation and activation of the coagulation cascade in response to both endothelial cell death and arrested blood components. Experimentally separating the first and second phases is nontrivial, as they are visually indistinguishable and occur on a similar time scale. This novel multifaceted mechanism reconciles conflicting findings in the literature and cautions the use of the FeCl3 model, especially in interpreting the initial stages of clotting. Our 2-phase description of the underlying mechanisms of this model complements and further explains Barr et al’s findings that red blood cells (RBCs) mediate FeCl3-induced thrombosis.10

Methods

Human blood was drawn according to institutional review board–approved protocols per the Declaration of Helsinki into sodium citrate (Becton Dickinson). To recapitulate the endothelium-blood-FeCl3 interface, a polydimethylsiloxane-based T-shaped microfluidic was designed with a 250-μm-width main channel, 50-μm-width side channel, and overall device height of 50 μm. When appropriate, channels were endothelialized as previously described.15 To study whole blood, RBCs were diluted in platelet-rich plasma (PRP) to 12.5% to allow for improved microscopy and visualization of clot components. To recalcify blood, CaCl2 (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 0.01 M directly prior to every experiment, unless otherwise noted. To analyze drug treatment data, we used a 2-tailed Student t test with a 95% confidence interval (with statistical significance when P < .05). See supplemental Methods for blood separation protocol, in vivo iron measurements, diffusion calculations, and flocculation experiment and drug treatment/mouse experiment protocol.

Results

Conceptual framework of in vivo FeCl3 model

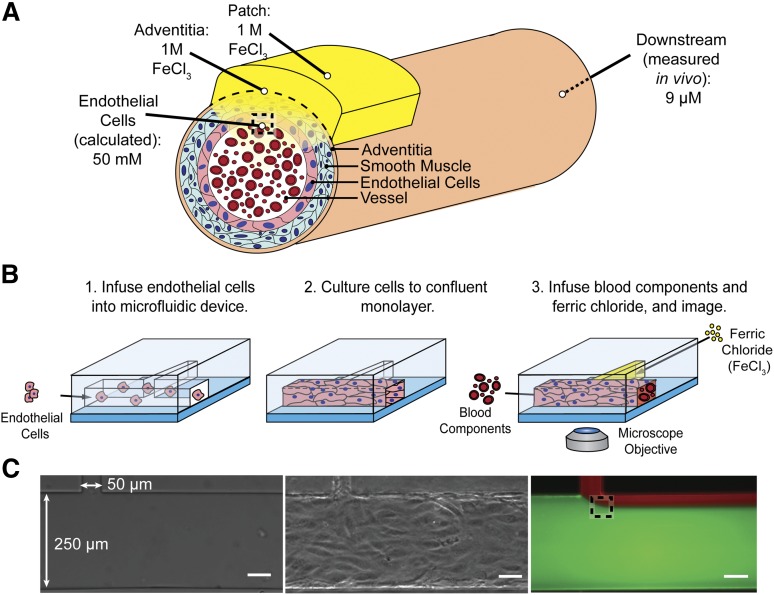

To recapitulate the in vivo FeCl3 model in a controlled in vitro system, the FeCl3 concentration that the endothelial cells and blood are exposed to was determined. Although the FeCl3 concentration at the vessel adventitia is that applied to the filter paper, the luminal endothelial cell concentration (after the FeCl3 diffuses through the vessel layers) is the unknown, but calculable, value of interest (Figure 1A). As diffusion of FeCl3 through the vessel wall is complex and difficult to experimentally validate, we instead measured the bulk iron concentration downstream of the application site in vivo and used Fick’s laws of diffusion to calculate the concentration at the endothelial cell/blood interface. Postapplication of 1 M FeCl3 to the adventitia of a mouse carotid artery, the bulk iron concentration in blood was found to be ∼9 μg/mL or 160 μM. Steady-state FeCl3 flux into the vessel is reached by 5 minutes and maintained at 10 minutes; the patch concentration is thus assumed to be constant over the relevant time scales. By equating flux of FeCl3 into the vessel to flux out of the vessel, a conservative estimate (that does not account for system losses) of concentration at the wall of the lumen is calculated to be ∼50 mM (supplemental Methods). This FeCl3 concentration can be introduced to blood components via perfusion into an in vitro microfluidic system, thereby giving us spatiotemporal control over FeCl3 concentration, and the ability to monitor its effects on blood and the vasculature.

Figure 1.

Recreating the in vivo FeCl3 model in a microfluidic platform. (A) Schematic of FeCl3 application (not to scale) in which a saturated 1 M FeCl3 patch is placed on the vessel adventitia. As the FeCl3 diffuses through the layers of the vessel wall, apparent concentration decreases, and at the luminal surface of the endothelial cells, the FeCl3 concentration is ≥50 mM. The dashed box at the luminal surface of the endothelial cells represents the location of interface of the solutions. (B) Endothelial cells are seeded in the large channel (250 μm) of a T-shaped microfluidic to recapitulate a blood vessel. FeCl3 is infused in the side channel (50 μm) and the blood/FeCl3 interface is visualized; shear stress 4 dyne/cm2. (C) Left to right, Bare microfluidic channel, endothelialized channel, and an example of fluid interface using fluorescent dyes and infusion rates of 2.7 μL per minute in large channel and 0.4 μL per minute in side channel. The dashed box represents the fluid interface that would be seen at the vessel wall in vivo. All scale bars represent 50 μm.

In vitro endothelialized microfluidic FeCl3 thrombosis model

To visualize the effects of FeCl3 on blood components in a reductionist manner, microfluidic channels were designed to introduce FeCl3 to individual blood components in a fixed shear environment. In vivo, FeCl3 continuously enters the vessel from the patch and interfaces with endothelial cells and blood. As convection dominates in this system, the FeCl3 concentration remains high near the vessel wall and flows downstream with the blood. The flow environment is aptly recapitulated using a T-shaped microfluidic; the influx of FeCl3 through a small side channel gives spatiotemporal control over the concentration, ensuring that the blood cells and endothelial cells at the streams’ interface are exposed to an exact input concentration. The 2 solutions interface near the channel wall, as it occurs in vivo (Figure 1C). The main channel of the microfluidic can be seeded with endothelial cells, which are cultured to a confluent monolayer on the channel surfaces, further recapitulating in vivo physiologic conditions (Figure 1B-C), though endothelial cells do not span the gap where the main channel joins the side channel. Endothelialized microfluidics enable us to concurrently visualize the effects of FeCl3 on blood and endothelial cells using standard bright-field and fluorescence video microscopy.

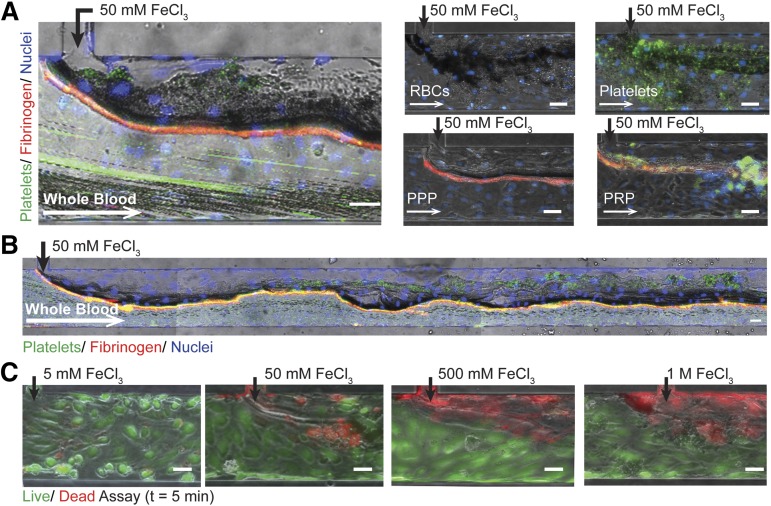

Effects of FeCl3 on in vitro “vasculature”

We recreated the in vivo FeCl3 model by introducing FeCl3 to blood in an endothelialized microfluidic system. When exposed to 50 mM FeCl3, endothelial cells remain adherent and whole blood forms an occlusive aggregate (Figure 2A; supplemental Video 1). Platelets and fibrinogen are present within the effective “clot,” but interestingly, erythrocytes constitute the bulk of the aggregate (Figure 2A). Furthermore, when individually introduced, washed RBCs, platelets, platelet-poor plasma (PPP), PRP, and even 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) form aggregates at the FeCl3 interface (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 1A, supplemental Video 2). The effect of FeCl3 on endothelial cell viability is concentration-dependent: endothelial cells are viable at low concentrations, but as concentrations increase from 5 mM to 1 M, endothelial cell death is more pervasive (Figure 2B). Dead endothelial cells remain adherent to the channels at all tested concentrations and shear stresses (up to 20 dyne/cm2), corroborating the results of Barr et al (data not shown).10

Figure 2.

Endothelialized microfluidics. (A) Aggregates form in endothelialized microfluidics infused with 50 mM FeCl3 and whole blood, washed RBCs, washed platelets, PPP, and PRP. Endothelial cells (blue: Hoescht), platelets (green: CD41), fibrinogen (red). (B) Aggregate formation over the length of the microchannel when whole blood is exposed to 50 mM FeCl3. (C) Endothelial cell viability is concentration dependent with increasing cell death at higher concentrations; left to right: 5 mM, 50 mM, 500 mM, 1 M (green/live: calcien, red/dead: propidium iodide). All scale bars represent 50 μm; N = 5.

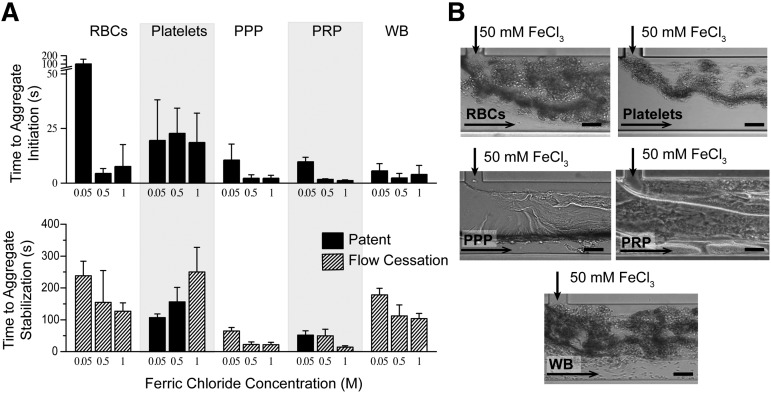

Effects of FeCl3 on blood in the absence of endothelial cells

To characterize the effects of FeCl3 on blood, independent of the endothelium, blood cells and proteins were individually exposed to FeCl3 in a “bare,” nonendothelialized, microfluidic device (Figure 1B), and time to aggregate initiation (adherence of components) and stabilization (complete or unchanging occlusion) were recorded. In the absence of endothelial cells, blood components form aggregates in a FeCl3 concentration–dependent manner, shown at 0.05, 0.5, and 1 M, as did 5% BSA (Figure 3; supplemental Figure 1B, supplemental Videos 3-4). At 50 mM, washed erythrocytes and platelets are slowest to aggregate, and proteins form sheet-like structures that appear to enhance cell binding and aggregation (Figure 3B). As the concentration of FeCl3 increases, the time to aggregate initiation decreases, and the time to aggregate stabilization generally decreases (Figure 3A). Full channel occlusion and flow cessation occur at 1 M FeCl3 in the absence of endothelial cells for all blood components.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism of FeCl3-induced thrombosis. (A) Aggregates of washed RBCs, washed platelets, PPP, PRP, and whole blood (WB) form in microfluidic channels at all concentrations ranging from 50 mM to 1 M. Time (in seconds) to initial adherence of blood components and stable aggregate formation (unchanging or complete occlusion) is shown, where complete channel occlusion is denoted by cross-hatched bars. (B) Representative images of blood component aggregates in nonendothelialized microfluidics are shown at 50 mM. The presence of sheet-like protein aggregates is clearly visible in PPP. All scale bars represent 50 μm; N = 5.

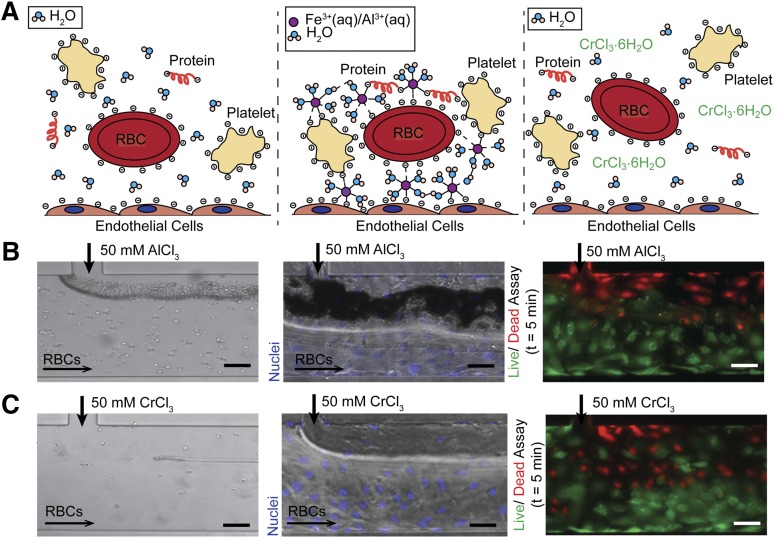

Proposed mechanism of FeCl3-induced aggregation

The universal aggregation effect of FeCl3 on blood cells and proteins in the absence of endothelial cells led us to posit a charge-based mechanism for aggregation (Figure 4A). Blood is a colloidal suspension of negatively charged cells and proteins; the stability, or resistance to aggregation, of colloidal particles in suspension is determined by the particle ζ potential, where a higher ζ potential corresponds to increased stability.16 In aqueous solutions, ferric ions undergo continuous hydrolysis, complexation, polymerization, and precipitation.17 At equilibrium, over a range of pH and FeCl3 concentrations, a number of species are present, predominantly Fe3+, Fe(OH)2+, and Fe2(OH)24+.18,19 Fe3+ ions can bind directly to negatively charged proteins (both soluble and cell surface localized), resulting in destabilization of those proteins with respect to flocculation, and furthermore resulting in cell aggregation.20 The cationic, amorphous hydroxide precipitates also deposit on negatively charged surfaces to form a large particulate matrix that entraps cells.18,21 Aggregation of colloidal components in the presence of metal salts proceeds by a combination of factors: an increase in ionic strength that reduces repulsion between similarly charged particles; adsorption of ions that neutralize charge and allow for particle bridging; and cell entrapment in a hydroxide precipitate.17,21 Interestingly, both FeCl3 and aluminum (III) chloride (AlCl3) are used in wastewater treatment to induce aggregation of colloidal suspensions of negatively charged toxins and biologics.21,22

Figure 4.

Charge-based mechanism of aggregation. (A) In healthy physiological conditions, blood cells and proteins are suspended in a stable colloidal suspension in water, separated due to electrostatic repulsion (left). Upon introduction of an ion (Fe3+ (aq), Al3+ (aq)) that can bind directly (form inner sphere complexes) to negatively charged proteins on cell surfaces or in suspension, blood cells and proteins are arrested on endothelial surface and form aggregates (middle). Upon introduction of a kinetically inert ion (Cr3+), the ion binds directly to water molecules and thus only has transient interactions with blood cells and proteins, allowing the cells to maintain their colloidal suspension as in the control condition (right). (B) The introduction of AlCl3 causes RBCs to aggregate at the fluidic interface in bare (left) and endothelialized (middle) microfluidics. AlCl3 causes endothelial cell death, but the cells remain adherent (right) (green/live: calcein; red/dead: propidium iodide). (C) The introduction of CrCl3 does not result in RBC aggregation in bare (left) or endothelialized (middle) microfluidics. CrCl3 causes endothelial cell death, but the cells remain adherent (right) (green/live: calcein; red/dead: propidium iodide). All scale bars represent 50 μm; N = 3.

In support of our hypothesized mechanism, introduction of Al3+, an ion similar to Fe3+ with respect to binding,20 results in erythrocyte aggregation in microchannels (Figure 4B). A recent publication likewise showed that the in vivo application of AlCl3 to a mouse carotid produces occlusive thrombosis.23 On the other hand, erythrocyte suspensions do not aggregate when exposed to Cr3+ because the ion has slow substitution kinetics and preferentially binds water instead of negatively charged species (Figure 4C).16,20 This suggests that to induce aggregation, a metal ion must be able to form inner sphere complexes (bind directly without intervening water molecules) with negatively charged moieties to form stable aggregates. Furthermore, exposure to both AlCl3 and chromium (III) chloride (CrCl3) results in endothelial cell death, suggesting that cell death alone is insufficient to initiate aggregation (Figure 4B-C).

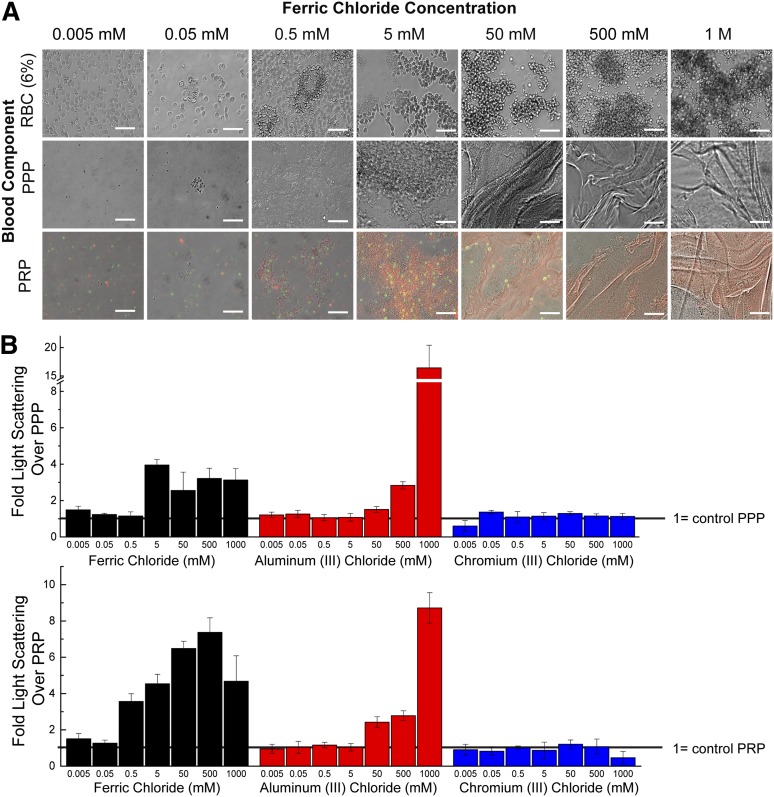

Blood components aggregate in static conditions when exposed to FeCl3. From 0.5 mM to 50 mM FeCl3, FeOH precipitates are visible and RBC membranes appear deformed; at concentrations >50 mM, proteins form sheet-like structures and RBCs form large aggregates (Figure 5A). Both FeCl3 and AlCl3 cause aggregation of recalcified PRP and PPP in the presence of FeCl3 as measured by dynamic light scattering, with aggregation generally increasing with increasing concentrations (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figure 2). Higher concentrations of AlCl3, relative to FeCl3, are necessary to initiate aggregation in all solutions; this is expected as AlCl3-induced colloid aggregation occurs over a narrow concentration and pH range.21 At concentrations of FeCl3 > 500 mM and AlCl3 > 1 M, the suspensions form a solid mass (supplemental Figure 2). Light-scattering measurements at these conditions are complicated by the nonergodic nature of the solution; that is, the size of the aggregates is large compared with the incident beam, so as the aggregates precipitate out, the solution is not temporally or spatially homogenous, and light scattering measurements are inaccurate.24 Measurements of aggregation of washed RBCs are likewise hampered by the solution’s nonergodicity, but microscopic and macroscopic examination show definitive aggregation, with solid masses forming at >50 mM FeCl3 (supplemental Figure 2B). As expected, CrCl3 does not induce aggregation, and there is no increase in light scattering over the controls at any tested concentration (Figure 5B-C).

Figure 5.

Flocculation activity of FeCl3. (A) The concentration-dependent ability of FeCl3 to aggregate blood components can be seen microscopically. At mid-range concentrations of FeCl3, amorphous iron hydroxide precipitates can be seen. Platelets (green: CD41); fibrinogen (red). (B) Light scattering of PRP (left) when exposed to a range of FeCl3, AlCl3, and CrCl3 concentrations. Values are expressed as fold increase over control PRP, where increased scatter corresponds to increased aggregation. Light scattering of PPP (right) exposed to a range of FeCl3, AlCl3, and CrCl3 concentrations. Values are expressed as fold increase over control PPP. All scale bars represent 50 μm; N = 3.

The presence of physiologic levels of divalent cations, Mg2+ and Ca2+, does not have a pronounced effect on aggregation parameters, as there are minimal changes in light scattering between samples with and without these cations (supplemental Figure 3A). After 20 minutes, recalcified PRP forms a stable, intrinsic coagulation pathway-derived clot with a sixfold increase in light scattering over the control. Light scatter of recalcified PRP solution exposed to 500 μM FeCl3 increases a further twofold after 20 minutes, increasing the scatter to that of the physiological clot (supplemental Figure 3B). This suggests that physiological clotting can occur in addition to metal ion–based aggregation.

Our findings suggest that initial adherence and aggregation of blood components in this model is due to inner-sphere complexation of Fe3+ to plasma proteins and cell membrane–localized proteins, as well as binding of cells to FeOH precipitates. Sheet-like protein aggregates also act as Fe3+ linkers that enhance cell binding (Figure 4A).

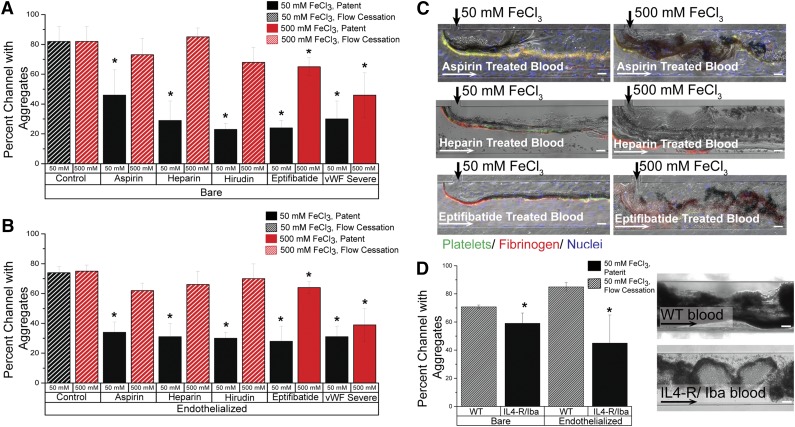

FeCl3-induced aggregate formation in altered clotting environments

Although the underlying mechanisms of the FeCl3 thrombosis model remain in question, its utility as an in vivo model to study clotting is well established. Numerous publications have shown that FeCl3-induced vascular occlusion is mitigated in knockout mice10,25,26 and in the presence of antithrombotic agents.27-31 Multiple platelet receptor defects have also been shown to modulate thrombus formation in the FeCl3 injury model.32 We monitored occlusion in both bare and endothelialized channels when blood was treated with aspirin (platelet inhibitor), heparin (thrombin inhibitor), hirudin (thrombin inhibitor), and eptifibatide (GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor), as well as blood reconstituted with von Willebrand factor (VWF)–free plasma obtained from a patient with type 3 von Willebrand disease. After 15 minutes, in both endothelialized and bare channels, all inhibitors significantly reduced occlusion (P < .05) when blood was exposed to 50 mM FeCl3; alternatively, when 500 mM FeCl3 was used, aspirin, heparin, and hirudin could not maintain vessel patency (Figure 6A-B; supplemental Figure 3). In control conditions, RBCs adhere at the FeCl3/blood interface, platelets stick to adherent RBCs, and a protein matrix forms; additional cells are entrapped within the growing protein/cell matrix and the dense aggregate expands across the full width of the channel. The aggregate is finally bordered by a layer of fibrinogen that “seals” the clot from blood flow, and flow within the channel ceases within 3 minutes (supplemental Figure 4). Cells enter the aggregate mass, but do not traverse it, and blood flow is restricted to the portion of the channel distal to the FeCl3 inlet. Alternatively, at 50 mM FeCl3, all inhibitors except aspirin prevent the extensive growth of aggregates past the interfacial line; aggregates do not have a large protein component and cells traverse the loose aggregate matrix, adhere transiently, and then resume transit through the channel. In one heparin experiment, aggregates initially span the channel, but blood flow dislodges the blockage and the vessel remains patent (supplemental Video 5). Aspirin-exposed blood, on the other hand, gives rise to disjointed, unstable protein/cell aggregates that readily embolize in response to fluid shear and lodge downstream (Figure 6C). When the concentration of FeCl3 is increased to 500 mM, aggregate formation is extensive in all conditions. Microchannel patency is partly retained in eptifibatide and VWF-free conditions because of the loose aggregate matrix, though blood flow is visibly decreased. At increasing FeCl3 concentrations, pharmacologic inhibition does not effectively prevent channel occlusion because, although the clotting cascade is compromised, the FeCl3 concentration is sufficiently high across the channel to induce charge-based aggregation.

Figure 6.

Aggregation of blood in altered clotting environments. (A) In bare microfluidics, all drugs and phenotypic abnormalities lead to significant decreases in channel occlusion at 50 mM (P < .05) compared with the control solution, but 500 mM FeCl3 overcomes the protective effect of aspirin, heparin, and hirudin. Solid bars represent patent channels while the slant pattern represents flow cessation. Significance is denoted by an asterisk (*), and was measured by a 2-tailed, Student t test between the treatment condition and its paired control (eg, 50 mM control and 50 mM aspirin). There was not a significant difference in occlusion between untreated control blood exposed to 50 mM and that exposed to 500 mM. (B) In endothelialized microfluidics, drugs and phenotypic abnormalities lead to significant decreases in occlusion at 50 mM (P < .5), but 500 mM FeCl3 overcomes the protective effect. Solid bars represent patent channels whereas the slant pattern represents flow cessation. Significance is denoted by an asterisk (*), and was measured by a 2-tailed, Student t test between the treatment condition and its paired control (eg, 50 mM control and 50 mM aspirin). There was not a significant difference in occlusion between untreated control blood exposed to 50 mM and that exposed to 500 mM. (C) Representative images from drug treatments in bare and endothelialized microfluidics, at 50 mM and 500 mM. Platelets (green: CD41), fibrinogen (red). (D) In bare and endothelialized channels, IL4-R/Iba blood forms fewer aggregates at 50 mM FeCl3 than WT blood, and the channel remains patent. Significance is denoted by an asterisk (*), and was measured by a 2-tailed, Student t test. Representative image of WT blood and IL4-R/Iba blood aggregation in the microfluidic channel. All scale bars represent 50 μm; N = 4.

Furthermore, FeCl3-induced aggregation in blood from wild-type mice was compared with that of mice lacking the extracellular domain of GPIb-α (IL4-R/Iba mice). As expected, wild-type blood exposed to 50 mM FeCl3 forms aggregates that fully occlude the channel in a manner similar to human blood (Figure 6D). GPIb-α–deficient blood results in significantly reduced occlusion with vessel patency maintained after 15 minutes. Unlike the extensive, continuous dense cell aggregate in the wild-type condition, IL4-R/Iba mouse blood forms disjointed aggregates that comprise regions of dense RBCs and sparse RBCs, allowing blood flow to continue through and around the aggregates (Figure 6D; supplemental Videos 6-7). The aggregates are primarily composed of RBCs as previously shown in vivo.10

The marked effects that mouse genotype and pharmacologic agents have on FeCl3-induced thrombus formation are congruous with our proposed mechanism of FeCl3 action, and our findings help to explain inconsistencies in thrombus formation between injury models, as well those between studies using the same injury model. Although the initial adhesion and aggregation of blood proteins and cells is mediated by concentration-dependent, charged-based interactions between FeCl3 and blood components, the progression to complete occlusion occurs via conventional clotting mechanisms involving platelet activation and the coagulation cascade. Similarly, Eckly et al’s findings suggest that initial platelet adhesion in the FeCl3 model is atypical of the clotting cascade as there is not extensive collagen exposure in the vessel.9

Discussion

The extensive use of the FeCl3 model in hematologic research and the lack of a well-defined mechanism of action led us to take a reductionist, yet interdisciplinary, microfluidic approach to study FeCl3-induced thrombosis. Our study reveals that FeCl3 has multiple dose-dependent effects on blood, in the presence and absence of endothelial cells, leading us to a novel 2-phase mechanism of action. In the first phase, the charge-based complexation of positively charged iron species and negatively charged proteins (cell surface bound and in solution) initiates FeCl3-induced thrombosis independent of biological ligand-receptor interactions. RBCs are the first adherent blood component, and form the bulk of the initial aggregate. Platelets and proteins are visible within the initial aggregate to a lesser degree (supplemental Figure 4A). We also recreate the findings that the extent of thrombus formation in this model is dependent on physiological clotting processes by introducing anticlotting agents and blood with phenotypic clotting deficiencies. This leads to the second phase of our proposed mechanism in which endothelial cell death and iron-bound, adherent blood components initiate the conventional biological clotting cascade. The final clot is RBC, platelet, and protein rich and expands across the width of the channel (supplemental Figure 4B). The inability to tightly control the FeCl3 concentration in vivo makes the distinction between chemically induced aggregation and physiological clotting impossible to assess. Likewise, there may be multifactorial effects from drugs such as heparin, whose high negative charge density likely affects the activity of FeCl3.

RBCs, platelets, PRP, and PPP all aggregate when exposed to FeCl3, tending toward increased aggregation as concentration increases. Aggregation is visible both macroscopically and microscopically, independent of endothelial cells, and with and without shear or mixing. FeCl3 is known to cause aggregation of colloidal solutions by ζ potential reduction, by directly binding to negatively charged particles, and by forming amorphous cationic hydroxide precipitates that can entrap and bind negatively charged particles.21 Furthermore, the binding of FeCl3 to negative proteins on blood cell surfaces, known as the “colloidal iron method,” was historically used to determine the distribution of anionic cites on cells, such as RBCs and endothelial cells.33-35 Aqueous iron species (hydroxides) precipitate on the surface of endothelial cells, as seen in our in vitro studies, and as corroborated by an in vivo FeCl3 mechanism study in which SEM revealed endothelial cell localized hydroxide deposits.36 We propose that RBCs are the first and most numerous cell species in the initial FeCl3-induced aggregate due to their membrane’s high negative charge density (sialic acid on the surface) and the concentration of erythrocytes in blood. Barr et al’s findings that RBC binding in the FeCl3 model occurs at arterial, venous, and mesenteric shear rates, is well explained by charge-based binding.10 In the absence of RBCs, platelets too form aggregates on the channel surface, though interactions are more transient and occlusion proceeds more slowly. FeCl3 is an oxidizing agent, and at high concentrations is a strong Lewis acid; this may contribute to the concentration-dependent endothelial cell death seen in our system. The acidity alone, however, does not cause cell aggregation: introducing acetic acid at pH 1 in endothelialized devices causes visible endothelial cell death but not RBC aggregation (not shown). The “charge-based” mechanism we present is further supported because an ion with similar binding activity, AlCl3, also causes cell aggregation, and in vivo thrombus formation.23 Inert CrCl3, however, causes endothelial cell death, but not cell aggregation.

At low concentrations of FeCl3 and high drug concentrations, extent of aggregation is mitigated. Aspirin-treated blood gives rise to an unstable, frequently embolizing thrombus; heparin and hirudin reduce the area of the channel covered by aggregates; eptifibatide leads to a loose matrix; and VWF deficiency increases time to aggregation and results in unstable occlusion. As seen in vivo, increasing the FeCl3 concentration can overcome the protective effect of these agents: there is a narrow range of FeCl3 concentrations for which there are differences between the treated and untreated conditions.

The dependency of thrombus initiation and extent of occlusion on FeCl3 concentration is well explained by our proposed mechanisms: there is a critical concentration of FeCl3 required at the lumen for aggregate initiation and propagation. Furthermore, the differences between occlusion in varying injury models and vessel types32 is well explained, as the sensitivity of the system to FeCl3 concentration is in part due to the intraluminal mass transport of FeCl3, which is a function of blood velocity and vessel diameter; simulations show that intraluminal flow conditions determine the percentage of the vessel that is exposed to FeCl3 concentrations that induce aggregation (>0.5 mM) (supplemental Figure 5). The role that mass transfer plays in the FeCl3 thrombosis model explains the variability in application techniques and results.

Full venous occlusion by FeCl3 in mice lacking the extracellular domain of GPIbα led researchers to propose that there is another ligand for VWF at venous shear rates; and similarly unusual RBC/platelet/ligand interactions have been proposed to explain unanticipated findings when using FeCl3.10,11,25,37 Our findings suggest that initial blood aggregation is independent of biological ligand/receptor interactions. Furthermore, in small vessels, the effective concentration of FeCl3 is higher over a larger area of the channel and charge-based binding is likely more extensive (supplemental Figure 5). We surmise that vessel wall composition and thickness, which vary by vessel type as well as by sex, age, weight, and genotype of mouse, will also affect the intraluminal FeCl3 concentration. However, investigation of these variables is beyond the scope of this article.

Our concentration-dependent mechanisms suggest that researchers should take caution when using the FeCl3 injury model and that the use of this model is not appropriate for studies in clot initiation, namely platelet-endothelium interactions. Likewise, FeCl3 concentration should be expressed as a molarity, as opposed to a percentage, for accurate comparisons between studies using hexahydrate and anhydrous FeCl3 species. FeCl3 should be also be reconstituted/diluted directly before use as spontaneous FeOH formation may change the diffusion properties of FeCl3, and thus its thrombotic activity, especially at low concentrations (high pH) where FeCl3 is unstable.

The controlled reductionist environment afforded by our in vitro endothelialized microfluidic system allows for precise control over FeCl3-induced thrombosis and led us to propose a novel, 2-phase mechanism for the action of FeCl3 in thrombus formation. The first phase is independent of typical biological “clotting,” and consists of the FeCl3 concentration-dependent binding of negatively charged blood cells and proteins to positively charged iron species. The adherent cells from the first phase initiate the second phase, the standard biological clotting cascade. Where one phase ends and the other begins is nontrivial to determine, as the effective FeCl3 concentration in the channel (which determines the extent of the first phase) is dependent on mass transfer phenomena. Researchers should take caution that this will affect their findings, especially in small vessels, and that aggregation phenomena that seemingly suggest a novel ligand/receptor interaction may in fact be due to nonspecific charge-based binding effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER award 1150235 (W.A.L), and National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants U54-HL112309 (J.C.C. and W.A.L.), U01-HL117721 (W.A.L.), and R01-HL121264 (W.A.L.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.C.C., R.L., L.A.L., S.M., C.G., and W.A.L. contributed to the conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of the research; J.C.C. and W.A.L. wrote the manuscript; J.C.C., Y.S., M.E.F., D.R.M., and B.H. performed research and collected and analyzed data; J.B.D. performed diffusion calculations; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Wilbur A. Lam, Georgia Institute of Technology, 345 Ferst Dr NW, Atlanta, GA 30318; e-mail: wilbur.lam@emory.edu; wilbur.lam@bme.gatech.edu.

References

- 1.Eysholdt K-G. Die experimentelle thrombose und ihre beeinflussung durch heparin und heparinoide. Langenbecks Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 1954;277(5):455–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurz KD, Main BW, Sandusky GE. Rat model of arterial thrombosis induced by ferric chloride. Thromb Res. 1990;60(4):269–280. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90106-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farrehi PM, Ozaki CK, Carmeliet P, Fay WP. Regulation of arterial thrombolysis by plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in mice. Circulation. 1998;97(10):1002–1008. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denis C, Methia N, Frenette PS, et al. A mouse model of severe von Willebrand disease: defects in hemostasis and thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(16):9524–9529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Smith PL, Hsu MY, et al. Effects of factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride-induced vena cava thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(9):1982–1988. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westrick RJ, Winn ME, Eitzman DT. Murine models of vascular thrombosis (Eitzman series). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(10):2079–2093. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konstantinides S, Ware J, Marchese P, Almus-Jacobs F, Loskutoff DJ, Ruggeri ZM. Distinct antithrombotic consequences of platelet glycoprotein Ibalpha and VI deficiency in a mouse model of arterial thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(9):2014–2021. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massberg S, Gawaz M, Grüner S, et al. A crucial role of glycoprotein VI for platelet recruitment to the injured arterial wall in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;197(1):41–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckly A, Hechler B, Freund M, et al. Mechanisms underlying FeCl3-induced arterial thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(4):779–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barr JD, Chauhan AK, Schaeffer GV, Hansen JK, Motto DG. Red blood cells mediate the onset of thrombosis in the ferric chloride murine model. Blood. 2013;121(18):3733–3741. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauhan AK, Kisucka J, Lamb CB, Bergmeier W, Wagner DD. von Willebrand factor and factor VIII are independently required to form stable occlusive thrombi in injured veins. Blood. 2007;109(6):2424–2429. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Owens AP, III, Lu Y, Whinna HC, Gachet C, Fay WP, Mackman N. Towards a standardization of the murine ferric chloride-induced carotid arterial thrombosis model. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(9):1862–1863. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kita A, Sakurai Y, Myers DR, et al. Microenvironmental geometry guides platelet adhesion and spreading: a quantitative analysis at the single cell level. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers DR, Sakurai Y, Tran R, et al. Endothelialized microfluidics for studying microvascular interactions in hematologic diseases. J Vis Exp. 2012;(64) doi: 10.3791/3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai M, Kita A, Leach J, et al. In vitro modeling of the microvascular occlusion and thrombosis that occur in hematologic diseases using microfluidic technology. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):408–418. doi: 10.1172/JCI58753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blesa MA, Matijević E. Phase transformations of iron oxides, oxohydroxides, and hydrous oxides in aqueous media. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 1989;29(3-4):173–221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schäfer AI, Fane AG, Waite TD. Chemical addition prior to membrane processes for natural organic matter (NOM) removal. In: Hahn H, Hoffmann E, Ødegaard H, editors. Chemical Water and Wastewater Treatment V. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1998. pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flynn CM. Hydrolysis of inorganic iron(III) salts. Chem Rev. 1984;84(1):31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stefánsson A. Iron (III) hydrolysis and solubility at 25 degrees C. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41(17):6117–6123. doi: 10.1021/es070174h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoeschele JD, Turner JE, England MW. Inorganic concepts relevant to metal binding, activity, and toxicity in a biological system. Sci Total Environ. 1991;109-110:477–492. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(91)90202-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan J, Gregory J. Coagulation by hydrolysing metal salts. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;100-102:475–502. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matilainen A, Vepsäläinen M, Sillanpää M. Natural organic matter removal by coagulation during drinking water treatment: a review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;159(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolters M, van Hoof RH, Wagenaar A, et al. MRI artifacts in the ferric chloride thrombus animal model: an alternative solution: preventing MRI artifacts after thrombus induction with a non-ferromagnetic Lewis acid. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(9):1766–1769. doi: 10.1111/jth.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pusey PN, Van Megen W. Dynamic light scattering by non-ergodic media. Physica A. 1989;157(2):705–741. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergmeier W, Piffath CL, Goerge T, et al. The role of platelet adhesion receptor GPIbalpha far exceeds that of its main ligand, von Willebrand factor, in arterial thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(45):16900–16905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608207103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joglekar MV, Ware J, Xu J, Fitzgerald ME, Gartner TK. Platelets, glycoprotein Ib-IX, and von Willebrand factor are required for FeCl(3)-induced occlusive thrombus formation in the inferior vena cava of mice. Platelets. 2013;24(3):205–212. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.696746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surin WR, Prakash P, Barthwal MK, Dikshit M. Optimization of ferric chloride induced thrombosis model in rats: effect of anti-platelet and anti-coagulant drugs. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2010;61(3):287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bird JE, Giancarli MR, Allegretto N, et al. Prediction of the therapeutic index of marketed anti-coagulants and anti-platelet agents by guinea pig models of thrombosis and hemostasis. Thromb Res. 2008;123(1):146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Cheng Q, Xu L, et al. Effects of factor IX or factor XI deficiency on ferric chloride-induced carotid artery occlusion in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):695–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Couture L, Richer LP, Cadieux C, Thomson CM, Hossain SM. An optimized method to assess in vivo efficacy of antithrombotic drugs using optical coherence tomography and a modified Doppler flow system. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2011;64(3):264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz M, Meade G, Stoll P, et al. Conformation-specific blockade of the integrin GPIIb/IIIa: a novel antiplatelet strategy that selectively targets activated platelets. Circ Res. 2006;99(1):25–33. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000232317.84122.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denis CV, Wagner DD. Platelet adhesion receptors and their ligands in mouse models of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(4):728–739. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000259359.52265.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolson GL. Anionic sites of human erythrocyte membranes. I. Effects of trypsin, phospholipase C, and pH on the topography of bound positively charged colloidal particles. J Cell Biol. 1973;57(2):373–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.57.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Bruyn PP, Michelson S, Becker RP. Nonrandom distribution of sialic acid over the cell surface of bristle-coated endocytic vesicles of the sinusoidal endothelium cells. J Cell Biol. 1978;78(2):379–389. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.2.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss L, Zeigel R. Cell surface negativity and the binding of positively charged particles. J Cell Physiol. 1971;77(2):179–186. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040770208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tseng MT, Dozier A, Haribabu B, Graham UM. Transendothelial migration of ferric ion in FeCl3 injured murine common carotid artery. Thromb Res. 2006;118(2):275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ni H, Papalia JM, Degen JL, Wagner DD. Control of thrombus embolization and fibronectin internalization by integrin alpha IIb beta 3 engagement of the fibrinogen gamma chain. Blood. 2003;102(10):3609–3614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]