Abstract

Introduction

Several studies have shown a proximal shift of colorectal cancer (CRC) during the last decades. However, few have analyzed the changing distribution of adenomas over time.

Aim

The aim of this study was to compare the site and the characteristics of colorectal adenomas, in a single center, during two periods.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective, observational study in a single hospital of adenomas removed during a total colonoscopy in two one-year periods: 2003 (period 1) and 2012 (period 2).

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease, familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, or history of CRC were excluded from the study.

The χ2 statistical test was performed.

P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the two considered periods, a total of 864 adenomas from 2394 complete colonoscopies were analyzed: 333 adenomas from 998 colonoscopies during period 1 and 531 adenomas from 1396 colonoscopies during period 2.

There was a significant increase in the proportion of adenomatous polyps in the proximal colon from period 1 to 2 (30.6% to 38.8% (p = 0.015)).

Comparing the advanced features of adenomas between the two periods, it was noted that in period 2, the number of adenomas with size ≥1 cm (p = 0.001), high-grade dysplasia (p = 0.001), and villous features (p < 0.0001) had a significant increase compared to period 1.

Conclusion

Incidence of adenomatous polyps in the proximal colon as well as adenomas with advanced features has increased in the last years. This finding may have important implications regarding methods of CRC screening.

Keywords: colorectal adenomas, advanced features, distribution, colorectal cancer screeening

What does this paper add to the literature?

In this study we observed a significant trend in the increase of right colorectal adenomatous polyps as well as adenomas with advanced features in the last years. We believe this finding may have important implications regarding methods of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening.

Background and aims

CRC is the second most common cancer in women and the third in men worldwide. According to the World Health Organization GLOBOCAN database, in 2008 approximately 1.2 million new cases of CRC were diagnosed and 608,000 people died of CRC.1

Most cases of CRC are sporadic and develop slowly over several years through the adenoma-carcinoma sequence.2

For this reason, detecting and removing adenomas will interrupt this sequence and may actually reduce the development and incidence of CRC.3–7

In the last decade, the literature has reported a change in the topographic distribution of CRC, consisting of a lesion shift toward the proximal sector of the colon.8–12

Right-sided colon cancer represents a great challenge for physicians because of the inherent technical limitations of endoscopy screening strategies.13 Indeed, a higher incidence of proximal cancers would tend to reduce the protective effect of sigmoidoscopy, favoring total colonoscopy as the method of choice.14

Only a few studies have addressed the possible changes in the location of polyps over time, although some have described a possible proximal shift.15–17

The purpose of this study was to compare the topographic distribution of colorectal adenomas in a single center during two distinct periods of time in order to assess the occurrence of a trend to a proximal shift. Advanced features (≥1 cm in diameter, high-grade dysplasia, and villous histology) were also compared between the two periods.

Methods

We performed a retrospective, observational study of adenomas removed during a total colonoscopy in a single center (Prof Doutor Fernando Fonseca Hospital, Amadora, Portugal) in two one-year periods of time: 2003 (period 1) and 2012 (period 2).

The data were collected from medical records, procedure reports and pathology reports.

The age and gender of the patients were recorded as well as the location, histology, morphology and dimensions of adenomas.

For discrimination between the proximal and distal colon, the boundary was situated at the juncture of the splenic flexure, as described in previous studies.13,18

All exams were performed by certified gastroenterologists using standard endoscopic equipment. Colonoscopes used (in 2003 and 2012) were CF-Q160AL, Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan. Additional technologies such as narrow band imaging were not used.

Only colonoscopies reaching the cecum were considered. Incomplete colonoscopies for any reason, namely inadequate bowel cleansing, intolerance, or tortuous colon, were excluded.

For all the colonoscopies, the quality of colon cleansing was adequate to allow a complete endoscopic evaluation of the colon.

Bowel preparation regimen was similar in the two periods: Four liters of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution was used in 2003 and 2012.

Sedation using intravenous midazolam (performed by a gastroenterologist) or intravenous propofol (performed by an anesthesiologist) was administered on a case-to-case basis.

Solely patients with sporadic polyps were included. Patients who met the criteria for hereditary non-polyposis CRC syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis or with past personal history of CRC were excluded from the study.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) were also excluded.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, we used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to assess normality. For normal variables, means and standard deviations were reported. For non-normal data, medians and interquartile ranges were reported.

χ2 test was used to assess the differences between the two periods.

Independent-sample t-test was used to assess for differences between the means in two periods.

P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0.

Results

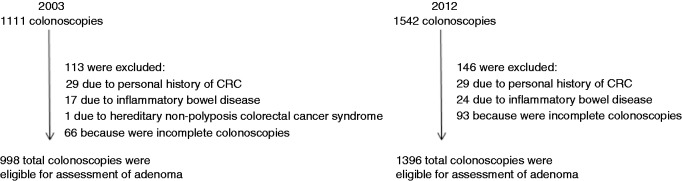

During the two periods considered, 2653 colonoscopies were performed: 1111 colonoscopies during period 1 and 1542 colonoscopies during period 2. Exclusion of 259 examinations (as depicted in the study flow diagram represented in Figure 1) resulted in 2394 complete colonoscopies. A total of 864 adenomas were analyzed: 333 adenomas from 998 colonoscopies during period 1 and 531 adenomas from 1396 colonoscopies during period 2.

Figure 1.

Colonoscopic examinations performed during the two periods.

CRC: colorectal cancer.

Adenomas were more frequently found in males than in females (66.3% in period 1 and 61.9% in period 2), but with no significant difference between period 1 and 2 (p = ns).

Median age at adenoma detection was greater in period 2 (67 years versus 64 years) with a statistically significant difference (p = 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population general characteristics

| Period 1 | Period 2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 187 | 362 | |

| Male | 124 (66.3) | 224 (61.9) | 0.30 CI 95% (0.04–0.13) |

| Female | 63 (33.7) | 138 (38.1) | |

| Age (years) | 64 (56–73) | 67 (59–74) | 0.001 CI 95% (1.3–5.2) |

| Total number of adenomas | 333 | 531 | |

| n (%), median (IQR) |

n: frequency; IQR: interquartile range; CI: confidence interval.

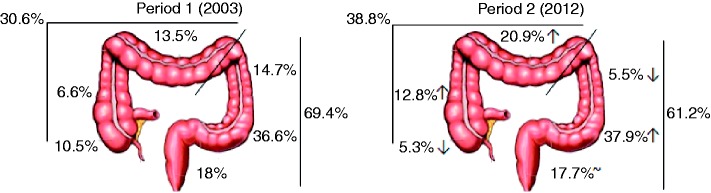

As depicted in Figure 2, the incidence of proximal adenomas increased from 30.6% to 38.8% (p = 0.015) from period 1 to period 2.

Figure 2.

Relative distribution of adenomas according to colon segment and rectum in periods 1 and 2. Relative percentages of adenomas are indicated near the corresponding tract of the colon and rectum. Total adenoma percentages of proximal and distal colon are also depicted.

↑: increase in the relative percentage of adenomas from period 1 to period 2; ↓: decrease in the relative percentage of adenomas from period 1 to period 2; ∼: no difference in the relative percentage of adenomas from period 1 to period 2.

Through the analysis of each segment separately, concerning proximal adenomas, there was an increase in the ascending colon (from 6.6% to 12.8%) and in the transverse colon (from 13.5% to 20.9%) and a decrease in the cecum (from 10.5% to 5.3%).

Regarding the distal colon, there was a reduction in adenomas in the descending colon (from 14.7% to 5.5%) and a slight increase in the sigmoid colon (from 36.6% to 37.9%). In the rectum, the percentage of adenomas was similar in the two periods (18% and 17.7%, period 1 and period 2, respectively).

The advanced features of adenomas (size ≥1 cm, high-grade dysplasia, and villous features) were also analyzed. There was an increase in the number of adenomas with size ≥1 cm (from 10.8% to 19.8%, p = 0.001) from period 1 to 2. Regarding histologic features, there was an increase in high-grade dysplasia (from 9.6% to 18.1%, p = 0.001), and villous features (from 11.4% to 30.0%, p < 0.0001) from period 1 to 2.

Discussion

In recent years, screening strategies for prevention of CRC by identification and removal of adenomatous polyps (precancerous lesions that may evolve to CRC) have been implemented.

Despite this effort, CRC is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in Europe.1

The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening of colorectal cancer in a standard population of adults between the ages of 50 and 75 years using any of the following three regimens: annual high-sensitivity fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy every five years combined with high-sensitivity fecal occult blood testing every three years, and screening colonoscopy at intervals of 10 years.19

Recent data from different studies report modifications as to the topographic distribution of CRCs, consisting of proximalization of these lesions.9,20,21 This fact may favor colonoscopy over sigmoidoscopy as a screening method.

Explanations for proximal shifting of colorectal adenomas are not clear: There may be a true increase in incidence in right-sided lesions (namely due to different genetic pathways of carcinogenesis between left and right locations22,23) or adenoma detection rate may have improved due to implementation of various quality-assessment indicators during colonoscopy24,25 (adenoma detection rate, recommended screening and surveillance intervals, adequate withdrawal times, and appropriate cecal intubation rates with photographic documentation24).

This study retrospectively evaluated the differences in the site distribution of colorectal adenomas between two periods over a period of nine years—2003 (period 1) and 2012 (period 2)—through analysis of endoscopic and pathology reports in a single center.

We observed a proximal shift in adenomas between periods 1 and 2.

Our results are in line with the results reported by Park et al. In their study, they reviewed medical records of patients who underwent a colonoscopy at a Korean Hospital between January 1996 and December 2005 and reported a significant increase in the proportion of adenomatous polyps on the proximal colon from 48.9% to 62.3% (p < 0.001).16

Fenoglio and colleagues also showed a significant increase in proximal adenomas between the first (1997–2001) and the second period (2002–2006), with 19.2% and 26%, respectively.14 In the study performed by Corleto et al., a proximal shift for polyps was observed, particularly in males (odds ratio (OR) 1.87, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.23–2.87; p < 0.0038) between period A (from 1989 to 1993) and B (2003 to 2007). However, no statistically significant differences in the overall number of adenomas were observed between the two periods.13

In our study, we also compared advanced colorectal adenomas between 2003 and 2012, observing an increased incidence in all features analyzed (≥1 cm in diameter, high-grade dysplasia, and villous histology) between these two periods.

Similar results were observed by Fenoglio et al., who reported an increased prevalence from 6.6% in the first period to 9.5% in the second period (OR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.02–2.17) considering only advanced adenomas.14

On the contrary, Kiedrowski et al. reported similar results between the two periods analyzed (1981–1994 and 2000–2004).26

Regarding polyp size, Corleto et al. found a statistically significant increase in the percentages of polyps of 10–19 mm in size from 10.3% to 15.1% (but they did not differentiate hyperplastic polyps from adenomas).13 Concerning histopathological pattern, their results diverge from ours as they reported increased frequency in adenomas with mild/moderate dysplasia in the proximal colon from period A to B, 21.8% to 41.2% (p < 0.001), respectively, whereas adenomas with severe dysplasia decreased from 37% to 23%, which was not statistically significant. However, histopathology data were not available for all polyps (data were available for 63.3% and 89.5% of polyps in period A and B, respectively).13

There are some limitations to our study that warrant consideration, namely the fact that it was conducted at only one hospital, which may limit the generalization of the data collected. In addition, all patients referred for colonoscopic examination had symptoms or family history of CCR. For this reason, the two patient groups in our study do not represent the normal screening population. In a healthy population, the topographic distribution of colon adenomas may be different from the patients in our study.

Nonetheless, even not knowing the causes of proximal shift in precancerous lesions, this retrospective study confirms, bearing in mind the aforementioned limitations, an increase in right adenomas over time.

This finding entails important implications regarding methods of CRC screening. Sigmoidoscopy, one of the methods recommended for CRC,19 would not detect those adenomas. Adenomas in the right colon are solely accessible at colonoscopy. Indeed, we do think screening strategies should address the whole colon, leaving the methods that evaluate only a part of the colon to specific situations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in our study there was a significant trend in the increase of proximal colorectal adenomatous polyps in the last years as well as adenomas with advanced features. This finding may have important implications regarding methods of CRC screening.

Acknowledgments

Contributions to this article include: Ana Maria Oliveira: Study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. Vera Anapaz: Analysis and interpretation of data. Luís Lourenço: Acquisition of data. Catarina Graça Rodrigues: Acquisition of data. Sara Folgado Alberto: Analysis and interpretation of data. Alexandra Martins: Writing of the manuscript. Jorge Reis: Study conception and design. João Ramos de Deus: Writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127: 2893–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2014; 383: 1490–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart AR, Kennedy JH. Preventing bowel cancer: An insight for clinicians. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2011; 3: 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leslie A, Carey FA, Pratt NR, et al. The colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Br J Surg 2002; 89: 845–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewett DG, Kahi CJ, Rex DK. Does colonoscopy work? J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010; 8: 67–76; quiz 77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1298–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1095–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cady B, Stone MD, Wayne J. Continuing trends in the prevalence of right-sided lesions among colorectal carcinomas. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obrand DI, Gordon PH. Continued change in the distribution of colorectal carcinoma. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez D, Dalal Z, Raw E, et al. Anatomical distribution of colorectal cancer over a 10 year period in a district general hospital: Is there a true “rightward shift”? Postgrad Med J 2004; 80: 667–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seydaoğlu G, Özer B, Arpacı N, et al. Trends in colorectal cancer by subsite, age, and gender over a 15-year period in Adana, Turkey: 1993–2008. Turk J Gastroenterol 2013; 24: 521–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajmanoochehri F, Asefzadeh S, Kazemifar AM, et al. Clinicopathological features of colon adenocarcinoma in Qazvin, Iran: A 16 year study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014; 15: 951–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corleto V, Pagnini C, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Is proliferative colonic disease presentation changing? World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 6614–6619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fenoglio L, Castagna E, Comino A, et al. A shift from distal to proximal neoplasia in the colon: A decade of polyps and CRC in Italy. BMC Gastroenterol 2010; 10: 139–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Offerhaus GJ, Giardiello FM, Tersmette KW, et al. Ethnic differences in the anatomical location of colorectal adenomatous polyps. Int J Cancer 1991; 49: 641–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SY, Kim BC, Shin SJ, et al. Proximal shift in the distribution of adenomatous polyps in Korea over the past ten years. Hepatogastroenterology 2009; 56: 677–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levi F, Randimbison L, La Vecchia C. Trends in the subsite distribution of colorectal carcinomas and polyps: An update. Cancer 1998; 83: 2040–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, et al. Right-side shift of colorectal adenomas with aging. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63: 453–458. quiz 464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, et al. Evaluating Test Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Screening—Age to Begin, Age to Stop, and Timing of Screening Intervals: A Decision Analysis of Colorectal Cancer Screening for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force from the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2009 Mar. (Evidence Syntheses, No. 65.2.) Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK34013/. [PubMed]

- 20.Cady B, Stone MD, Wayne J. Continuing trends in the prevalence of right-sided lesions among colorectal carcinomas. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto M, Stiratori Y, Yamaji Y, et al. Relationship between age and site of colorectal cancer based on colonoscopy findings. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55: 548–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher M, Fisher L, Waxman B, et al. Changing trends in colorectal cancer: Possible cause and clinical implications. Health 2010; 2: 842–849. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azzoni C, Bottarelli L, Campanini N, et al. Distinct molecular patterns based on proximal and distal sporadic colorectal cancer: Arguments for different mechanisms in the tumorigenesis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoenfeld P, Cohen J. Quality indicators for colorectal cancer screening for colonoscopy. Tech Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 15: 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper GS. Colonoscopy: A tarnished gold standard? Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2588–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiedrowski M, Mróz A, Kamiński MF, et al. Proximal shift of advanced adenomas in the large bowel—does it really exist? Pol Arch Med Wewn 2012; 122: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]