Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To characterize the use of and disposition from a tertiary pediatric emergency department (PED) by children with chronic conditions with varying degrees of medical complexity.

METHODS:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a dataset of all registered PED patient visits at Seattle Children’s Hospital from January 1, 2008, through December 31, 2009. Children’s medical complexity was classified by using a validated algorithm (Clinical Risk Group software) into nonchronic and chronic conditions: episodic chronic, lifelong chronic, progressive chronic, and malignancy. Outcomes included PED length of stay (LOS) and disposition. Logistic regression generated age-adjusted odds ratios (AOR) of admission with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

RESULTS:

PED visits totaled 77 748; 20% (15 433) of which were for children with chronic conditions. Compared with visits for children without chronic conditions, those for children with chronic conditions had increased PED LOS (on average, 79 minutes longer; 95% CI 77–81; P < .0001) and hospital (51% vs 10%) and PICU (3.2% vs 0.1%) admission rates (AOR 10.3, 95% CI 9.9–10.7 to hospital and AOR 25.0, 95% CI 17.0–36.0 to PICU). Admission rates and PED LOS increased with increasing medical complexity.

CONCLUSIONS:

Children with chronic conditions comprise a significant portion of annual PED visits in a tertiary pediatric center; medical complexity is associated with increased PED LOS and hospital or PICU admission. Clinical Risk Group may have utility in identifying high utilizers of PED resources and help support the development of interventions to facilitate optimal PED management, such as pre-arrival identification and individual emergency care plans.

KEY WORDS: children with special health care needs, medically complex, chronic conditions, children with chronic conditions

What’s Known on This Subject:

Children with chronic conditions use the pediatric emergency department (PED) more frequently than children without chronic conditions. To date, no one has examined how medical complexity relates to PED use and disposition.

What This Study Adds:

Varying degrees of medical complexity among children with chronic conditions are associated with increased PED length of stay, inpatient admission, and PED visit frequency. Clinical Risk Group software is able to identify disproportionate users of PED and hospital resources.

Children with special health care needs are defined broadly as “those who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.”1 Children with special health care needs comprise 13.9% to 15.6% of children in the United States,2–5 and are a rapidly growing population in pediatrics.6,7 A subset of children with chronic health conditions are those with medical complexity,8,9 which generally includes children with lifelong multiorgan system conditions, who have increased technology dependence and are cared for by multiple subspecialists. This group of children appears to account for increasing amounts of inpatient hospital use.10,11

Children with chronic conditions use emergency services more frequently than their nonchronic peers.2,4,12–20 The vulnerability of children with chronic medical conditions in the emergency setting, as well as the need for concise summaries of their medical condition, precautions needed, and/or special management plans, has been recognized by both the pediatric and emergency medicine communities.21–24 Better understanding of the increasingly large and medically complex subsets of children among those with chronic conditions is critical to optimizing their emergency care.

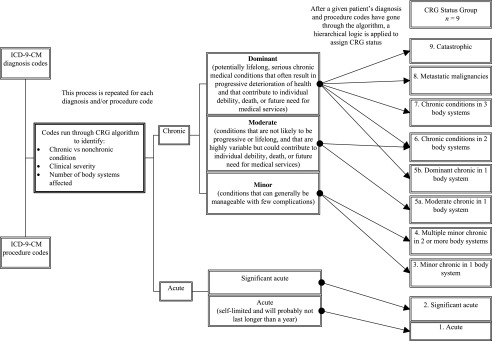

In the 1990s, the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions, in conjunction with 3M Health Information Systems (Salt Lake City, UT), developed a software program called Clinical Risk Groups (CRG). CRG uses diagnostic and procedure codes within a patient record to not only categorize children by nonchronic and chronic conditions, but also to stratify them by clinical severity into 9 groups25 (Fig 1). CRG has been validated by using inpatient and ambulatory patient data,25,26 but it has not previously been applied to pediatric emergency department (PED) data.

FIGURE 1.

Clinical Risk Groups (CRG) algorithm. ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification.

The objective of this study was to characterize the use of and disposition from a tertiary PED by children with nonchronic and chronic conditions at varied levels of medical complexity using CRG.

Methods

The study population included all patients registered for PED visits between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2009, at Seattle Children’s Hospital (SCH) in Seattle, Washington. SCH is a tertiary care center for a multistate region. Approximately half of all hospitalized patients are admitted through the PED; very few are directly admitted from the community. The PED is staffed by residents and nurse practitioners supervised by pediatric emergency medicine attending physicians. We excluded PED visits for patients older than 25 years of age, with a PED length of stay <10 minutes or >1500 minutes, and for patients who could not be assigned a CRG category because of inconsistent or missing data, such as International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification codes, date of birth, or gender. SCH’s Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study.

Data variables were collected from PED and hospital administrative databases (Epic and Cer-clini). For each child who had a PED visit, we obtained the child’s International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification diagnostic and procedure codes over the previous 3 years for use by the CRG software. At the time of their index PED visit, we obtained age, gender, race, time of admission and discharge from the PED, and disposition from the PED.

The predictor variable of interest was the individual patient’s CRG category. CRG places a child into 1 of 9 mutually exclusive hierarchical status groups (Fig 1). For this study, we grouped CRG into 5 final categories: nonchronic (CRG status groups 1 and 2) and chronic (CRG status groups 3–9), which include episodic chronic (CRG status groups 3, 4, 5a), lifelong chronic (CRG status groups 5b, 6), progressive chronic (CRG status groups 7, 9), and malignancy (CRG status group 8). The primary outcome of interest was PED disposition, which was (1) admission to hospital; (2) admission to PICU; (3) discharge to home; (4) other (included transfer to another facility, left without being seen and left against medical advice, death, and unknown). Secondary outcomes included PED length of stay (LOS) in minutes, as well as numbers of PED visits per patient over the study period. Although PED visit and admission cost data are important outcomes, they were not available in this dataset and, therefore, were not included in the analysis. Independent variables that were considered included age in years, gender, and race.

Data analysis was completed by using Stata 10SE (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and R statistical software programs (Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were generated for PED visits and descriptive variables, including age, race, and gender. Bivariate analysis was performed to describe outcomes across all CRG categories. Rates of outcomes by CRG category were also generated. Outcomes were then compared across CRG groups, including the collective chronic category, with nonchronic as the referent category. ANOVA test of differences was used to compare differences in age, gender, and race between CRG groups. Logistic regression was used to determine the odds of PICU admission for each CRG group, after controlling for age. Linear regression was used to determine the age-adjusted PED LOS for each CRG, after controlling for age. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

PED visits totaled 79 017 over the 2-year study period; however, 1269 visits were excluded, including 235 for individuals older than 25 years of age, 1120 visits that were <10 minutes or >1500 minutes in duration, and 263 for patients who we could not assign a CRG. The final cohort included 77 748 PED visits for 49 948 children.

Children with chronic conditions comprised 20% (n = 15 433/77 748) of all visits (Table 1). Children in the episodic and lifelong chronic groups accounted for 80% (n = 12 383/15 433) of all visits made by children with chronic conditions. The most medically complex group (progressive chronic) represented 12% (n = 1840/15 433) of visits made by children with chronic conditions.

TABLE 1.

PED visits and patient characteristics by CRG group, 2008–2009; n = 77 748

| Nonchronic | All Chronic | Episodic | Lifelong | Progressive | Malignancy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PED visits, n (%) | 62 315 (80) | 15 433 (20) | 5759 (7) | 6624 (9) | 1840 (2) | 1210 (2) |

| No. unique patients, n | 43 364 | 6584 | 2909 | 2765 | 545 | 365 |

| Mean age, y | 6.5 | 8.8 | 7.7 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 9.7 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 33 676 (54) | 8256 (54) | 3267 (57) | 3366 (51) | 959 (52) | 664 (55) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Native American | 542 (1) | 178 (1) | 62 (1) | 64 (1) | 20 (1) | 32 (3) |

| White | 29 727(47) | 7716 (50) | 2749 (48) | 3392 (51) | 948 (51) | 627 (52) |

| Other | 16 894 (27) | 3788 (24) | 1494 (26) | 1564 (24) | 439 (24) | 291 (24) |

| Black | 7183 (11) | 1758 (11) | 624 (11) | 801 (12) | 233 (13) | 100 (8) |

| Asian | 4421 (7) | 1018 (7) | 435 (7) | 395 (6) | 101 (5) | 87 (7) |

| Hispanic | 6 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Did not indicate | 3542 (6) | 975 (6) | 395 (7) | 408 (6) | 99 (5) | 73 (6) |

As shown in Table 1, the mean age was older for children with chronic conditions and increased with increasing medical complexity (ANOVA test of differences between means, all significant P < .0001). Among visits for children with chronic conditions, 54% (8256/15 433) were made by boys and 50% (7716/15 433) by patients who self-identified as white. Increasing medical complexity was not associated with significant gender or race differences.

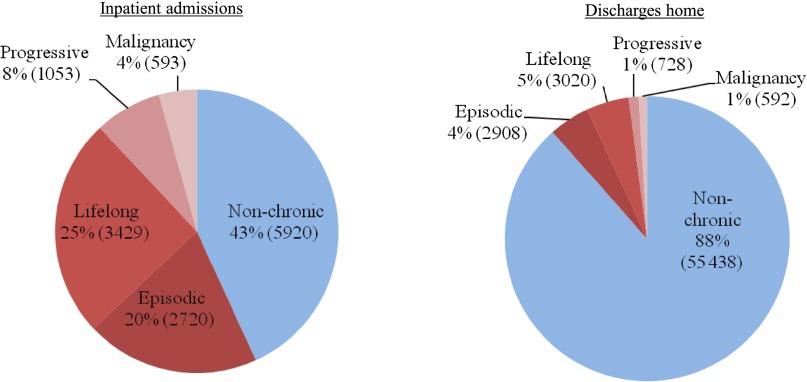

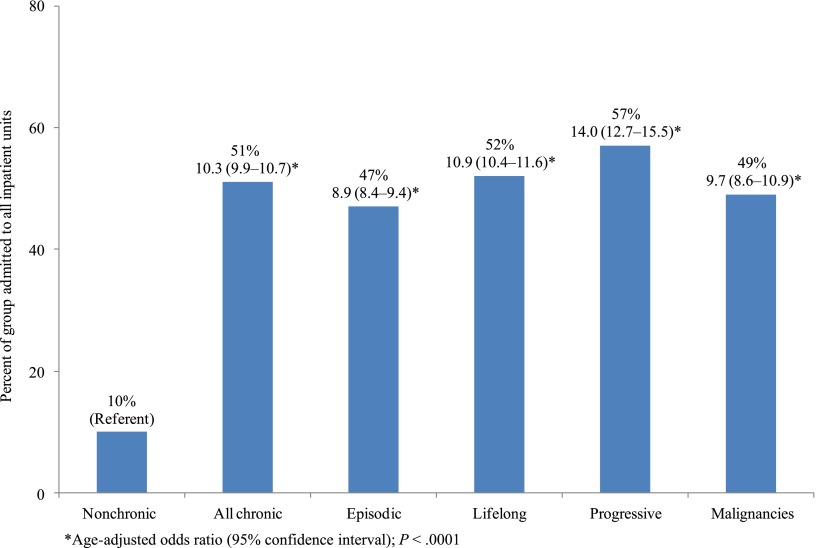

Disposition from the PED varied by chronicity, as well as by increasing medical complexity (Fig 2). Most, 57% (n = 7795/13 715), of all inpatient admissions from the PED were for children with chronic conditions. Compared with children without chronic conditions, children with chronic conditions were admitted more often to the hospital (51% vs 10%) (Table 2). Higher odds of hospital admission (AOR 10.3, 95% CI 9.9–10.7; P < .0001) were seen for children with chronic conditions (Fig 3). Rates of hospital admission increased with increasing medical complexity (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

PED disposition in nonchronic versus chronic children (by CRG group).

TABLE 2.

Outcomes by CRG Group

| Outcome | Nonchronic | All Chronic | Episodic | Lifelong | Progressive | Malignancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All inpatient admission rate,a n (%) | 5920 (10) | 7795 (51) | 2720 (47) | 3429 (52) | 1053 (57) | 593 (49) |

| PICU only admission rate,b n (%) | 90 (0.1) | 487 (3.2) | 98 (1.7) | 266 (4.0) | 83 (4.5) | 40 (3.3) |

| Discharged from the hospital, n (%) | 55 438 (89) | 7248 (47) | 2908 (50) | 3020 (46) | 728 (40) | 592 (49) |

| Other, n (%) | 659 (1) | 97 (1) | 45 (1) | 46 (1) | 5 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Unknown, n (%) | 298 (0) | 293 (2) | 86 (2) | 129 (2) | 54 (3) | 24 (2) |

| Median PED LOS, min (IQR)c | 152 (102–221) | 239 (163–324) | 235 (156–324) | 247 (170–330) | 255 (185–336) | 204 (147–271) |

| PED visits over 2-y study periodd | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Higher admission rates for children with versus children without chronic conditions, 51% vs 10% (AOR 10.3, 95% CI 9.9–10.7).

Higher admission rates for children with versus children without chronic conditions, 3.2% vs 0.1% (AOR 25, 95% CI 17–36).

Linear regression comparing LOS by CRG, after controlling for age, all differences compared with nonchronic were significant with 95% CI, P < .0001.

ANOVA test of differences between means, all significant P < .0001.

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of and adjusted odds of inpatient admission from the PED by CRG group.

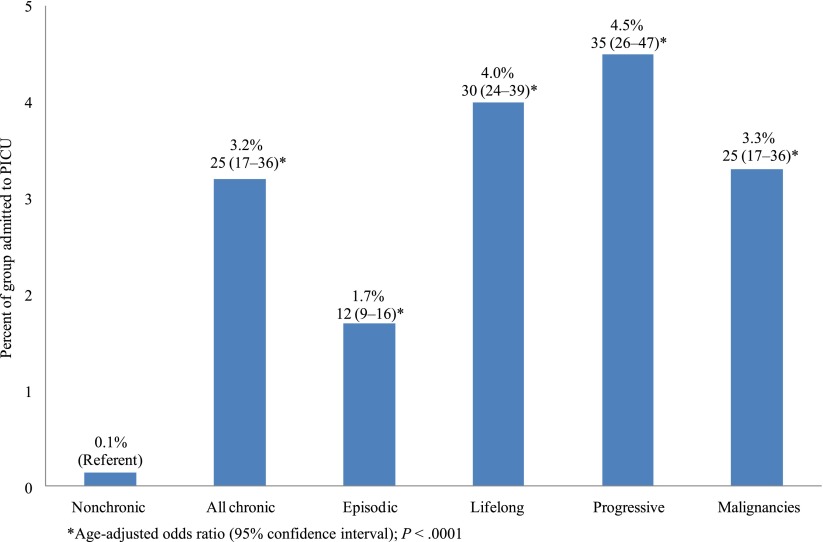

Children with chronic conditions accounted for 84% (n = 487/577) of all PED to PICU admissions (Table 2) and these children had higher PICU admission rates (3.2% vs 0.1%) compared with children without chronic conditions. Rates of PICU admission also increased with increasing medical complexity (Fig 4); when controlled for age, children with chronic conditions had higher odds of PICU admission (AOR 25, 95% CI 17.0–36.0; P < .0001), and odds of PICU admission increased with increasing medical complexity.

FIGURE 4.

Percentage of and adjusted odds of PICU admission from the PED by CRG group.

In addition to admissions, median PED LOS was longer for children with chronic conditions and increased with increasing medical complexity (Table 2). On average, visits for children with chronic conditions were 79 minutes longer (95% CI 77–81; P < .0001) compared with children without chronic conditions. The average number of visits per patient over the 2-year study period increased with increasing medical complexity from 1.2 among those without chronic conditions, to 3.4 for the progressive chronic group (Table 2). Of the 10 deaths that occurred in the PED, 2 were children with chronic conditions in the lifelong chronic category, and the remaining 8 were children without chronic conditions.

Discussion

This study found that children with chronic conditions comprise 20% of PED visits. With increasing medical complexity, the rates of both hospital and PICU admission, PED LOS, and repeat PED visits all increased. For example, the most medically complex category of children (progressive) used 2.4% of PED visits, but had a hospital admission rate of 57% and PICU admission rate of 4.5%.

Our study mirrors earlier work focused on PED use by children with chronic conditions. Our finding that 20% of PED visits at a tertiary care center were made by children with chronic conditions is consistent with previous studies that range from 1.8% to 24.0%15,17,19,27; differences between studies may be because of differences in definition used. In addition, SCH PED patient characteristics were similar to previous studies, which found that children with chronic conditions were more often boys and older.2,12,14,15,19,28–30 We found children with chronic conditions accounted for 57% of the hospital and 84% of the PICU admissions from the PED. Previous studies have found increased rates of admission from the PED for children with chronic conditions compared with children without chronic conditions, ranging from 28% to 38% vs 11% to 23% to the hospital and 1% vs 0.03% to the PICU.15,19,31,32 This is the first study to use a tool to stratify children with chronic conditions by medical complexity and describe associated PED use and disposition. Although our findings about increased utilization with increased medical complexity are unique, they are not surprising. The results suggest a large population of medically vulnerable children. The observation is further substantiated by the near linear relationship between medical complexity and both PED LOS and hospital and PICU admission rates. Risk of emergency PICU admission already has been reported for children with technology assistance, a group that would correspond with the progressive chronic CRG category.31

Children with chronic conditions in this study, in addition to being admitted more often, also remained in the PED longer than their nonchronic peers. Interpretation of PED LOS is limited given that other factors affecting LOS, such as PED patient census, provider-to-patient ratio, and inpatient bed availability, were not evaluated. Nonetheless, increasing LOS associated with increasing medical complexity suggests a period of prolonged evaluation and/or intervention as well as the implication of increased use of PED resources.

This study has several limitations. To identify children with chronic conditions, CRG uses existing diagnostic and procedural codes in administrative data for a given patient. Therefore, a child with chronic conditions who had not previously been to the hospital would not be reliably identified as a child with a chronic condition. Thus, it is possible that within our study population there were children with chronic conditions who were misclassified as nonchronic; however, this limitation would bias us away from finding differences between groups, which we observed. Another limitation is that of our setting. Because SCH is one of the few dedicated tertiary pediatric centers in a multistate region, the proportion of PED visits made by children with chronic conditions is relatively high, although consistent with previous literature. To be considered representative of pediatric institutions, this analysis should be repeated in geographic areas with multiple pediatric tertiary care facilities or by using a multicenter PED database, which is facilitated by recent inclusion of CRG in the Pediatric Health Information System database. In addition, in our institution, there are very few direct admissions from community providers and children with chronic conditions are admitted through the PED. Therefore, direct admissions do not affect the results of this study. In other institutions where direct admissions occur with greater frequency or vary by chronic and nonchronic patient status, however, the PED to inpatient admission rates could be affected and direct admissions would need to be considered in the analysis.

One of the study outcomes, PED LOS, could be indirectly affected by hospital or PED-based quality improvement initiatives designed to improve PED throughput, thus confounding our results. During the study period, however, there were no hospital or PED initiatives or policy changes that involved or affected PED evaluation, admission, or discharge processes.

Finally, decision-making around admission for an individual patient is complex and may include not only medical, but also social reasons, such as necessary family respite. It is not clear from the current study, if the driver of admission was more frequently acute clinical instability or chronic medical fragility. It is possible that a portion of these children were also admitted more frequently because of challenges in clinical assessment, whereupon a longer observation period would allow for ongoing assessment of their clinical status and progression. An evaluation of the social components for admissions, as well as associated cost data, were beyond the scope of this article and not available in the study data set.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, this study convincingly demonstrates that children with chronic conditions comprise a significant portion of annual visits in a tertiary PED, and their degree of medical complexity is associated with increased LOS and need for inpatient and PICU admission. CRGs, which stratify medical complexity based on hospital administrative data, demonstrate an ability to identify disproportionate users of PED and hospital resources. Emergency departments must be prepared to care for children with chronic medical complexity. Potential interventions to aid in preparation for both institutions as well as individual patients include individual pre-arrival identification, the use of individual emergency care plans, and expedited admissions processes.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Holly Clifton for her expertise in using Clinical Risk Groups software and for providing the primary data for this study.

Glossary

- AOR

adjusted odds ratios

- CRG

Clinical Risk Group

- CI

confidence interval

- LOS

length of stay

- PED

pediatric emergency department

- SCH

Seattle Children’s Hospital

Footnotes

Dr L. O’Mahony conceptualized and designed the study, managed data acquisition, carried out data analysis and interpretation, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs D.S. O’Mahony, Simon, and Neff carried out data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Klein and Quan conceptualized and designed the study, carried out data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

None of the sponsors participated in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Simon is supported by Award K23NS062900 from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, the Child Health Corporation of America via the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Setting Network Executive Council, Seattle Children’s Center for Clinical and Translational Research, and CTSA Grant ULI RR025014 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr Neff is a consultant to Classification Research of National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions (NACHRI) for development of software, especially Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs), a product of NACHRI and 3M Health Information Systems (HIS). 3M HIS has granted Seattle Children’s Hospital a no-cost research license for this project to test CRG use in a children’s hospital discharge data set. Dr Neff receives no royalties from CRGs or any NACHRI/3M HIS products and has no financial interests in either NACHRI or 3M HIS. The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

References

- 1.McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1 pt 1):137–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2009-2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Available at: www.childhealthdata.org/action/databriefs. Accessed July 10, 2012

- 3.Bethell CD, Read D, Blumberg SJ, Newacheck PW. What is the prevalence of children with special health care needs? Toward an understanding of variations in findings and methods across three national surveys. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(1):1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(1):10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kavanagh PL, Adams WG, Wang CJ. Quality indicators and quality assessment in child health. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(6):458–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy NA, Carbone PS, Council on Children With Disabilities. American Academy of Pediatrics . Parent-provider-community partnerships: optimizing outcomes for children with disabilities. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):795–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrin JM, Bloom SR, Gortmaker SL. The increase of childhood chronic conditions in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2755–2759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bramlett MD, Read D, Bethell C, Blumberg SJ. Differentiating subgroups of children with special health care needs by health status and complexity of health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(2):151–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, Fussell JJ, Robbins JM. Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):638–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook BA, Krischer JP, Kraft RE. Use of health care by chronically ill children in rural Florida. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(6):644–652 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neff JM, Anderson G. Protecting children with chronic illness in a competitive marketplace. JAMA. 1995;274(23):1866–1869 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto LG, Zimmerman KR, Butts RJ, et al. Characteristics of frequent pediatric emergency department users. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11(6):340–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds S, Desguin B, Uyeda AB, Davis AT. Children with chronic conditions in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1996;12(3):166–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, Machlin SR, Zodet MW, et al. Health care for children and youth in the United States: 2001 annual report on access, utilization, quality, and expenditures. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(6):419–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weller WE, Minkovitz CS, Anderson GF. Utilization of medical and health-related services among school-age children and adolescents with special health care needs (1994 National Health Interview Survey on Disability [NHIS-D] Baseline Data). Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 pt 1):593–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciccone MO, Debbia C, Cartosio ME, Di Pietro P. The chronically ill patient in the emergency department: management during simultaneous acute disease. Pediatr Med Chir. 2003;23(3):174–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massin MM, Montesanti J, Gérard P, Lepage P. Children with chronic conditions in a paediatric emergency department. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(2):208–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroner EL, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Emergency department reliance: a discriminatory measure of frequent emergency department users. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacchetti A, Sacchetti C, Carraccio C, Gerardi M. The potential for errors in children with special health care needs. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1330–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carraccio CL, Dettmer KS, duPont ML, Sacchetti AD. Family member knowledge of children’s medical problems: the need for universal application of an emergency data set. Pediatrics. 1998;102(2 pt 1):367–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine and Council on Clinical Information Technology. American College of Emergency Physicians. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee . Policy statement—emergency information forms and emergency preparedness for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):829–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. American Academy of Pediatrics . Emergency preparedness for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/104/4/e53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Popalisky J, Gay JC. Identifying and classifying children with chronic conditions using administrative data with the clinical risk group classification system. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neff JM, Clifton H, Park KJ, et al. Identifying children with lifelong chronic conditions for care coordination by using hospital discharge data. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(6):417–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson DS, Walsh K, Fleisher GR. Spectrum and frequency of pediatric illness presenting to a general community hospital emergency department. Pediatrics. 1992;90(1 pt 1):5–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahon M, Kibirige MS. Patterns of admissions for children with special needs to the paediatric assessment unit. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(2):165–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newacheck PW, Strickland B, Shonkoff JP, et al. An epidemiologic profile of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1 pt 1):117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein REK, Silver EJ. Comparing different definitions of chronic conditions in a national data set. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dosa NP, Boeing NM, Ms N, Kanter RK. Excess risk of severe acute illness in children with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics. 2001;107(3):499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton D, Stanley P, Babl FE, Phillips F. Preventing or accelerating emergency care for children with complex healthcare needs. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]