Abstract

Background and Objective

In health, the periodontal ligament maintains a constant width throughout an organism’s lifetime. The molecular signals responsible for maintaining homeostatic control over the periodontal ligament are unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of Wnt signaling in this process by removing an essential chaperone protein, Wntless (Wls) from odontoblasts and cementoblasts, and observing the effects of Wnt depletion on cells of the periodontal complex.

Material and Methods

The Wnt responsive status of the periodontal complex was assessed using two strains of Wnt reporter mice, Axin2LacZ/+ mice and Lgr5LacZ/+. The function of this endogenous Wnt signal was evaluated by conditionally eliminating the Wntless (Wls) gene using an Osteocalcin Cre driver. The resulting OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice were examined using micro-CT and histology, immunohistochemical analyses for Osteopontin, Runx2 and Fibromodulin, in situ hybridization for Osterix, and alkaline phosphatase activity.

Results

The adult periodontal ligament is Wnt responsive. Elimination of Wnt signaling in the periodontal complex of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice results in a wider periodontal ligament space. This pathologically increased periodontal width is due to a reduction in the expression of osteogenic genes and proteins, which results in thinner alveolar bone. A concomitant increase in fibrous tissue occupying the periodontal space was observed along with a disruption in the orientation of the periodontal ligament.

Conclusion

The periodontal ligament is a Wnt dependent tissue. Cells in the periodontal complex are Wnt responsive and eliminating an essential component of the Wnt signaling network leads to a pathological widening of the periodontal ligament space. Osteogenic stimuli are reduced and a disorganized fibrillary matrix results from depletion of Wnt signaling. Collectively, these data underscore the importance of Wnt signaling in homeostasis of the periodontal ligament.

Keywords: Wntless, periodontal ligament, width, osteogenic factor

The widespread occurrence of periodontal diseases, and the realization that damaged or diseased tissues might be amenable to regenerative strategies, has generated considerable interest in the growth factors and cells that comprise the periodontium. Of these, perhaps the most difficult tissue to envision regenerating is the periodontal ligament. Therefore, we focused our study on defining the endogenous signals required for its homeostasis.

The periodontal ligament originates from a population of cranial neural crest cells that differentiate into the collagen-producing cells of the periodontal ligament. These cells secrete an extracellular matrix that organizes itself into collagen fiber bundles. The two ends of these fiber bundles undergo mineralization but the central region remains fibrous. This organization is more or less maintained throughout life (1) except in pathological situations such as ankylosis.

The human periodontal ligament space has hourglass shape, with the narrowest region being at the mid-root level (2). Maintenance of periodontal width is an important yardstick of this tissue’s homeostasis (3), because this maintenance is achieved by adaption of the periodontal ligament to applied forces (4). The ability of periodontal ligament cells to promote and suppress bone and cementum formation is also an essential part of maintaining the periodontal ligament space (5).

With age, the periodontium undergoes significant changes. Alveolar bone surfaces and cementum surfaces transition from being smooth and having regular, evenly distributed Sharpey’s fibers insertions, to being jagged and having an uneven distribution of Sharpey’s fibers (6). In addition, aging is associated with a reduction in the number and quality of periodontal fibers (6). Here, we sought to understand the role of Wnt signaling in periodontal ligament homeostasis and in doing so, discovered some clues into age-related phenotypes in the periodontal ligament.

Material and methods

Generation of mouse strains

The generation of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice has been described previously (7, 8). For this study, twenty 3 month-old mice were analyzed; 10 were OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice and 10 were wild-type littermates. The generation of Axin2LacZ/+ mice has been described previously (9, 10). Five 2 month-old mice were analyzed here. Lgr5LacZ/+ mice were described previously (11); five 2 month-old mice were analyzed.

Micro-CT analyses

Micro-CT analyses were carried out using MicroXCT-200 (SkyScan, Belgium) at 60kV and 7.98 Watt and a resolution of 2 microns. Scans were acquired using 8μm3 isotropic voxel size, with 800 CT slices evaluated in incisor area. Individual CT slices were reconstructed with MicroXCT7.0 reconstruction software (SkyScan, Belgium), and the resulting data were analyzed with Inveon Research Workplace (IRW) (Erlangen, Germany). Five wild-type and 5 OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl littermates were analyzed by micro-CT.

Sample preparation, processing and histology

Maxillae from 3-month old mice (6 wild-type, 6 OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl littermates) were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Samples were decalcified in a heat-controlled microwave in 19% EDTA for two weeks. After demineralization, specimens were dehydrated through an ascending ethanol series prior to paraffin embedding. Eight-micron-thick longitudinal sections were cut and collected on Superfrost-plus slides for histology.

In situ hybridization

Tissue sections were deparaffinized following standard procedures. Relevant digoxigenin-labeled mRNA antisense probes were prepared from complementary DNA templates for Osterix. Sections were dewaxed, treated with proteinase K, and incubated in hybridization buffer containing the relevant RNA probe. Probe was added at an approximate concentration of 1 μg/ml. Stringency washes of saline sodium citrate solution were done at 65°C and further washed in maleic acid buffer with 1% Tween 20.

Slides were treated with an antibody to Anti-digoxigenin-AP (Roche). For color detection, slides were incubated in nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (Roche) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche). After developing, the slides were coverslipped with permount mounting medium.

Histology

Movat’s pentachrome staining was performed (12). Tissues were also stained with the acidic dye Picrosirius red (13) to discriminate tightly packed and aligned collagen molecules.

Cellular assays and immunohistochemistry

Alkaline phosphatase staining and DAPI staining were performed to evaluate osteogenic factor and to count cells, respectively (14, 15). For immunostaining, tissue sections were deparaffinized, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by 3% hydrogen peroxide then washed in PBS. Slides were blocked with 5% goat serum (Vector S-1000) for 1 hour at room temperature. The appropriate primary antibody was added and incubated overnight at 4°C, then washed in PBS. Samples were incubated with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector BA-x) for 30 minutes, and washed in PBS. An advidin/biotinylated enzyme complex (Kit ABC Peroxidase Standard Vectastain PK-4000) was added and incubated for 30 minutes and a DAB substrate kit (Kit Vector Peroxidase subtrate DAB SK-4100) was used to develop the color reaction. Antibodies used include Runx2 (Origene, dilution 1: 2000), Osteopontin (NIH LF 175, dilution 1: 4000), Fibromodulin (Santa Cruz Biotech, dilution 1: 1000) and β-catenin (Lab Vision, dilution 1:100).

L-Wnt3a stimulation of mouse bone marrow-derived stromal cells

Bone marrow from 2 month-old mice was harvested; cultured in Dulbecco modified Medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C overnight. After washing in PBS, cells were incubated with either 100ng/μl L-Wnt3a or L-PBS in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 12 hours. Cells were then washed with PBS, fixed with 4% PFA and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, then staining for beta catenin was performed as described previously(10).

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as the mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was used to quantify differences described in this article. Two asterisks (**) denote a p value of less than .01.

Results

Wnt responsiveness is maintained in the adult periodontal complex

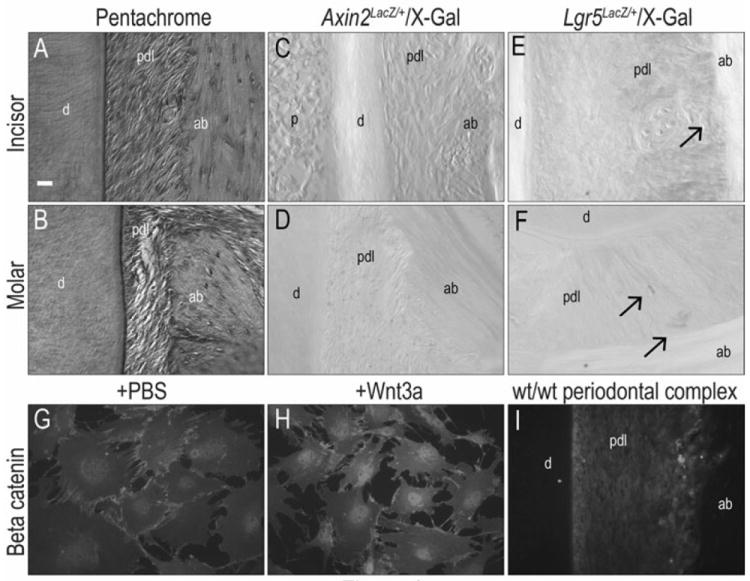

We used a strain of Wnt reporter (e.g., Axin2LacZ/+) mice to evaluate whether tissues comprising the PDL retained a dependency on Wnt signaling in adulthood. In these mice, an exon of the Wnt target gene Axin2 has been replaced with LacZ. X-gal staining can then be used to detect the LacZ gene product beta galactosidase (16). In both incisor (Fig. 1A,C) and molar (Fig. 1B,D) periodontal ligament spaces, we identified X-gal positive cells with a characteristic fibroblast morphology.

Fig.1. Wnt responsiveness in periodontal ligament space was maintained until adulthood.

(A, B) Pentachrome staining showed intact periodontal complex structure of incisors and molars in 2-month old Axin2LacZ/+ mice. (C, D) The periodontal ligament space in 2-month old Axin2LacZ/+ incisors and molars are X-gal positive. (E, F) The periodontal ligament space in 2-month old Lgr5LacZ/+ incisors and molars are X-gal positive. (G) β-catenin was observed in the cell membranes in PBS treated bone marrow cells. (H) β-catenin was localized in the cell nuclei in Wnt3a treated bone marrow cells. (I) β-catenin positive cells were found in periodontal ligament space of wild-type mice. Scale bar: (A-F) 50μm

We verified the Wnt responsive status of the adult periodontal ligament space using two other approaches. We used a second Wnt reporter strain (17), Lgr5LacZ/+ and X-gal staining revealed a few positive cells in the incisor (Fig. 1E) and in the molar (Fig. 1F). β-catenin is an intracellular mediator of Wnt signaling (18) and its nuclear localization identifies Wnt-responsive cells. We demonstrated this by treating bone marrow cells with PBS (as a negative control) or with recombinant human WNT3A protein. In PBS treated samples, β-catenin immunostaining was localized to the cell membrane (Fig. 1G) in keeping with previous reports (19, 20). In Wnt3a treated samples, β-catenin immunostaining was largely restricted to the cell nuclei (Fig. 1H), in keeping with its essential function in Wnt signal transduction. We then performed β-catenin immunostaining on the periodontal complex and found that most of the positive cells were localized to the periodontal ligament space (Fig. 1I). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Wnt signaling plays a role in the adult periodontal complex. Our next experiments directly addressed what that role entailed.

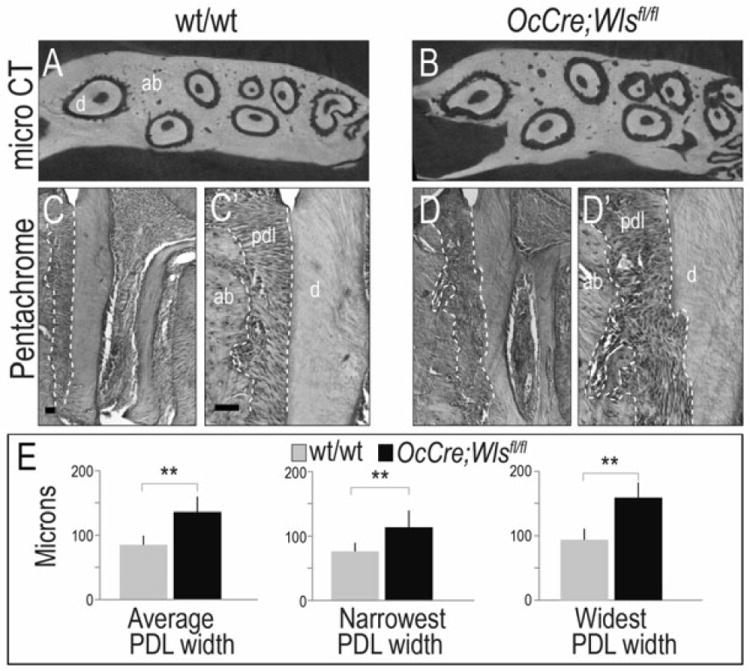

Loss of Wnt secretion from Osteocalcin-expressing cells results in a wider periodontal ligament space

We employed a strain of mice, OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl, in which Cre recombinase expression is under control of an Osteocalcin promoter driver, to eliminate Wntless, a chaperone protein that is essential for the secretion of mammalian Wnt proteins (21, 22). We verified that the loss of Wnt signaling occurs in both osteoblasts (8) and odontoblasts (7). Micro-CT examination of the maxillary periodontal complex revealed that compared to wild-type littermates, OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice had a wider periodontal ligament space (asterisks, Fig. 2A,B). OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice also exhibited irregular root surfaces, which sharply contrasted with the smooth root surfaces in wild-type mice (compare Fig. 2A,B).

Fig.2. Down regulation of Wnt signaling resulted in wider periodontal ligament space of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice.

(A, B) Micro-CT in the maxillary periodontal complex showed root resorption and wider periodontal ligament space in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to intact root surface and periodontal ligament space in the wild-type. (C, D) Histologic examination showed the wider periodontal ligament space in the sagittal section of maxillary first molar of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to the wild-type mice. (C’, D’) Higher magnification supported that there were root resorption and wider periodontal ligament space in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to the intact cementum in the wild-type mice. (E) Quantification showed that there was significantly wider periodontal ligament space in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to wild-type when measured in the narrowest, average and widest area. ** p < .01. Scale bar: (C, D) 50μm, (C’, D’) 50μm

Histologic examination of the maxillary periodontal complex confirmed that in comparison to the periodontal ligament space in wild-type mice, the periodontal ligament space in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice was noticeably wider (dotted white lines, Fig. 2C,D). Higher magnification of the periodontal complex supported this conclusion: compared to wild-type tissues, the alveolar bone and root surfaces in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice had a cratered appearance (Fig. 2C’,D’). Quantification of the narrowest, the widest, and the average widths of the periodontal ligament space were performed; compared to wild-type mice, the periodontal ligament space of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice was significantly wider (Fig. 2E).

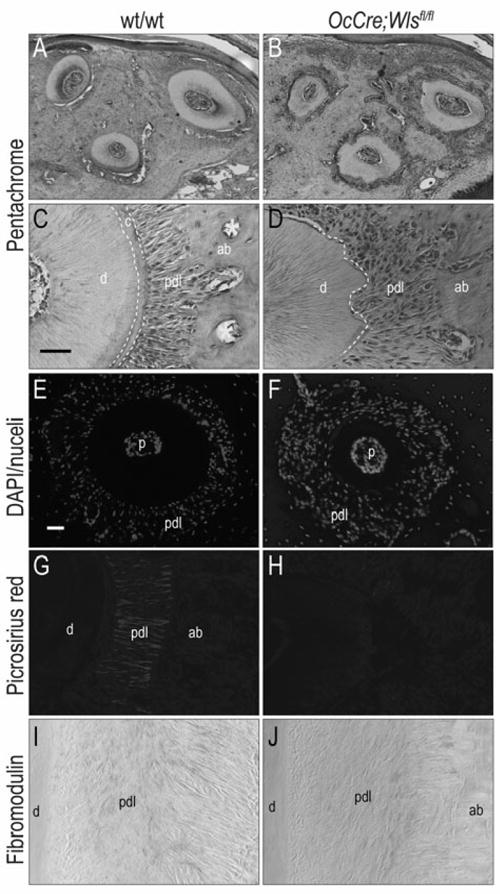

Loss of Wnt secretion causes periodontal breakdown

We evaluated other components of the periodontal complex. Low magnification (Fig. 3A,B) and high magnification images (Fig. 3C,D) clearly showed the lack of cementum and a highly disorganized periodontal ligament in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice. Vascular spaces, which were evident throughout the alveolar bone of wild-type mice (yellow asterisks, Fig. 3C) were notably reduced in the alveolar bone of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice (Fig. 3B,D).

Fig.3. A disruption of Wnt signaling causes deterioration of periodontal complex in the OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice.

(A, B) Pentachrome staining showed that intact root surface and well organized periodontal ligament fibers in the wild-type mice compared to the resoprtion of root structures and disorganization of periodontal ligament fibers in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice. (C, D) Higher magnification supported absence of cementum and disorganization of periodontal ligament fibers in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to intact cementum and well organized periodontal ligament fibers in the wild-type mice (E, F) Periodontal ligament space in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice was occupied with increased number of cells compared to wild-type mice. (G, H) Picrosirius red staining showed absence of periodontal ligament fibers adjacent to resorbed root and disorganization of fibers in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to highly organized collagen fiber insertion in the wild-type mice. (I, J) Expression of Fibromodulin in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice was reduced compared to the wild-type mice. Scale bar: (A, B) 50μm, (C, D, G-J) 50μm, (E, F) 50μm

From these histologic analyses we had the impression that the periodontal ligament in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice was occupied by more cells, but less periodontal fibers. DAPI staining confirmed this impression: compared to wild-type mice, there was a much higher cell density in the OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl periodontal space (Fig. 3E,F). Other tissues including the pulp and the alveolar bone, however, showed no obvious differences in cell density. We used Picrosirius red staining to visualize the fibrous collagen network that gives the periodontal ligament its orderly arrangement (Fig. 3G), and found that in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice this collagen-rich matrix was dramatically reduced (Fig. 3G). Cells in the periodontal ligament express Fibromodulin (23-27), which clearly marked the organized fibrous tissue in wild-type mice (Fig. 3I). The reduced expression of Fibromodulin and disorganized appearance of the periodontal ligament in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice verified our initial impressions (Fig. 3J). Thus, deletion of Wls and the reduction in Wnt signaling observed in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice resulted in a disorganized periodontal ligament that lacked its typical collagenous extracellular matrix.

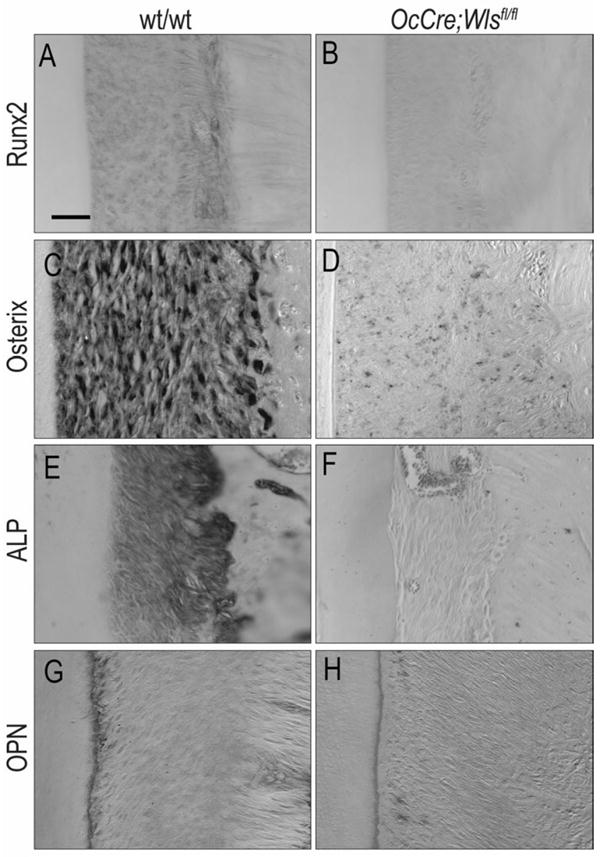

Down-regulation of Wnt signaling decreases osteogenic markers in PDL

Cells of the periodontal ligament are believed to be osteogenic in nature (28, 29). We evaluated a number of early osteogenic markers using immunostaining and in situ hybridization. In wild-type mice, Runx2 protein was expressed in the PDL space with intense expression on the alveolar bone surface, and no expression on the cementum surface (Fig. 4A). In OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice, Runx2 protein was only minimally expressed in the periodontal ligament (Fig. 4B). We also examined mice for the expression of osteogenic genes and found that Osterix was strongly expressed in the wild-type periodontal ligament (Fig. 4C) but was minimally expressed in the periodontal ligament of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice (Fig. 4D).

Fig.4. Alteration of osteogenic marker in periodontal ligament space of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice resulted from down regulation of Wnt signaling.

(A, B) Significantly reduced Runx2 expression was observed in periodontal ligament space of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to the wild-type mice. (C, D) Osterix expression was significantly reduced in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice compared to the wild-type mice. (E, F) ALP expression was found in periodontal ligament space of wild-type mice, while it was not observed in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice. (G, H) Osteopontin was strongly expressed in wild-type cementoblasts, while weak expression was observed in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl cementoblasts. Scale bar: (A-H) 50μm

The trend where osteogenic markers were expressed at very low levels in the mutant was observed again when we analyzed alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity: ALP activity was high in the wild-type periodontal ligament and low or undetectable in the OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl periodontal ligament (Fig. 4E,F). In wild-type mice, Osteopontin was strongly expressed in cementoblasts (Fig. 4G) but only weakly expressed in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl cementoblasts (Fig. 4H). Taken together, these molecular and cellular analyses demonstrate that normally osteogenic nature of the periodontal ligament depends upon Wnt signaling; in an environment where Wnt signaling is blocked (8), the expression of osteogenic markers is dramatically reduced.

Discussion

Cells of the periodontal ligament are responsive to an endogenous Wnt signal. Using two strains of Wnt reporter mice we demonstrate that the periodontal ligament maintains active Wnt signaling well into adulthood (Fig. 1). As confirmation of the Wnt-dependent status of the periodontium, we showed that the intracellular Wnt mediator β-catenin (30) is localized to the nuclei of cells in the periodontal ligament (Fig. 1). The function of this endogenous Wnt signal in the periodontal complex is currently unknown, and this became the focus of our investigation.

There is a wealth of data regarding the role of Wnt signaling in tissue homeostasis (reviewed in (31)) but in the adult periodontal complex, the function of Wnt signaling is less clear. Gain- and loss-of-function strategies have provided some insights: for example, transgenic mice over-expressing the soluble Wnt antagonist Dkk1 (32) under control of a collagen type I promoter exhibit a wider periodontal ligament space and root resorption (33). The authors did not speculate about the mechanisms responsible for these phenotypes, however. In vitro studies suggest that a Wnt stimulus leads to up regulation of osteogenic genes such as Osterix, Runx2, and alkaline phosphatase in cells isolated from the periodontal ligament (34), implying a role for Wnt signaling in mineralization of the tissue. Our own studies have implicated Wnt signaling in the constant turnover of the murine incisor periodontium (35) but we did not directly test the consequence of Wnt perturbation. OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice, in which Wnt signaling is abrogated by elimination of the Wntless chaperone protein, exhibit a reduction in alveolar bone volume (Fig. 2 and see (8)). As a consequence, we found that the periodontal ligament space is widened (Figs. 2,3).

We anticipated these findings. In previous work, others and we demonstrated that a positive Wnt stimulus is required for the commitment of cells to an osteogenic lineage (36, 37). In the absence of a Wnt stimulus, bone formation is attenuated (8, 38, 39). Amplifying the endogenous Wnt stimulus, either by biochemical means (9) or via a genetic approach (10) accelerates the differentiation of stem and osteoprogenitor cells into osteoblasts, which may be a method to stimulate regenerative bone formation (40). Thus, the loss of alveolar bone and cementum was a foreseeable phenotype resulting from depletion of a Wnt stimulus (8, 41). Our results here demonstrate that Wnt signaling also functions in homeostasis of the periodontal ligament (Fig. 1). Which aspects of homeostasis are under Wnt control became our next focus (Fig. 3).

The width of the periodontium changes with age and prevailing theories dictate that mechanical loading is largely responsible for these alterations. For example, tooth loss results in hyper-loading of the remaining dentition, which leads to pathological widening of the PDL (42). Conversely, a lack of occlusion leads to atrophy and a narrowing of the PDL space (43, 44). In OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice, however, no teeth were lost and the animals were examined only up to three months of age; consequently, any changes in the width of the periodontium were not due to tooth loss or advanced biological age.

Instead, we attribute disruptions to the periodontal complex to changes in biological signals that normally maintain this tissue. We suspected that gross widening of the periodontium in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice was attributable to thinner radicular alveolar bone and expression analyses for Osterix, Runx2, Osteopontin, and ALP (Fig. 4), coupled with 3D reconstructions of the micro-CT images and histological analyses (Fig. 2) confirmed that the radicular alveolar bone was significantly reduced in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice. Thus, pathological widening of the periodontal ligament space can be in part attributed to a disruption in Wnt-mediated alveolar bone formation.

There are two possible explanations for the reduced thickness of the cementum. First, it is formally possible that the cementum initially forms but fails to attach properly to the dentin and thus is lost; or second, that the cementum, like the alveolar bone, is thinner because of excessive bone resorption. To discriminate between these possibilities we evaluated OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice at progressively earlier stages of development and found that in 1 month-old pups, the cementum was present and appeared to be of a similar thickness as wild-type controls. Thus it is unlikely that the first explanation is viable. To address the possibility that cementum, like alveolar bone, forms normally in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice but is lost through excessive osteoclast activity, we evaluated OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice and wild-type littermates for TRAP activity. In addition, we evaluated whether cementum thickness is affected in mice that have elevated Wnt signaling (e.g., Axin2) and are in in a separate, ongoing study we evaluated these analyses.

We further speculated that the OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl periodontal ligament space widened as a result of an aberrant increase in the amount of cells or fibrous tissue produced by these cells. Except in disease states, the number and distribution of cell nuclei per mm2 in the periodontium is relatively constant (4). Cell density, which is defined as the number of cells in a given volume, remains relatively constant with age (45) and is controlled by three factors: the rate of cell division; the rate of cell death; and cell migration into the region of interest. In a previous examination of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice we found no significant difference in cell proliferation (46). It is unlikely that cell migration in the adult intact dentition contributes significantly to changes in cell density within the PDL; consequently, the most likely contributor to increased cell density in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice is a reduction in cell death.

At three months of age, the periodontal complex of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice resembled that of an elderly animal (6, 47). We speculate that a reduction in Wnt signaling is at least partly responsible for some of the age-related changes in tissue architecture we observe in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice. For example, bone mass is decreased with age, even in healthy individuals (48), and bone loss is a hallmark of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice (7, 8). Dentin becomes progressively thicker as humans age (49) and OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice also exhibit a significantly thicker dentin (7). In humans, the volume of the pulp is reduced with aging (50), a phenotype which we also observe in OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice (7). Thus, changes in mineralized tissues of OCN-Cre;Wlsfl/fl mice(7) are consistent with an aging phenotype.

Aging is obviously a complex process (51) but there is accumulating evidence to support the theory that some of these age-related atrophic changes in mineralized tissues are due to a reduction in Wnt signaling. For example, there is a strong correlation between telomere length and biological age (52) and new data demonstrate that telomerase activity, which is essential for stabilizing and maintaining the length of telomeres, is regulated by Wnt signals (53-57). Conversely, diminished Wnt signaling is associated with abnormally short telomeres, and the early onset of aging (55, 58, 59). By understanding more completely this link between aging phenotypes and Wnt signaling we will undoubtedly gain insights into how to diminish age-related deterioration of dental tissues.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by a grant from the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) TR1-01249.

Micro XCT imaging work was performed at the Division of Biomaterials and Bioengineering Micro-CT Imaging Facility, UCSF, generously supported by NIH S10 Shared Instrumentation Grant (S10RR026645).

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ten Cate AR. The development of the periodontium--a largely ectomesenchymally derived unit. Periodontol 2000. 1997;13:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanci A, Bosshardt DD. Structure of periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCulloch CA, Lekic P, McKee MD. Role of physical forces in regulating the form and function of the periodontal ligament. Periodontol 2000. 2000;24:56–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2240104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCulloch CA, Melcher AH. Cell density and cell generation in the periodontal ligament of mice. The American journal of anatomy. 1983;167:43–58. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001670105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimono M, Ishikawa T, Ishikawa H, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of periodontal regeneration. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;60:491–502. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Severson JA, Moffett BC, Kokich V, Selipsky H. A histologic study of age changes in the adult human periodontal joint (ligament) J Periodontol. 1978;49:189–200. doi: 10.1902/jop.1978.49.4.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim WH, Liu B, Cheng D, et al. Wnt signaling regulates pulp volume and dentin thickness. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2088. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong Z, Zylstra-Diegel CR, Schumacher CA, et al. Wntless functions in mature osteoblasts to regulate bone mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120407109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leucht P, Jiang J, Cheng D, et al. Wnt3a reestablishes osteogenic capacity to bone grafts from aged animals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1278–1288. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minear S, Leucht P, Jiang J, et al. Wnt proteins promote bone regeneration. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:29ra30. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, et al. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Movat HZ. Demonstration of all connective tissue elements in a single section; pentachrome stains. AMA Arch Pathol. 1955;60:289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittaker P, Kloner RA, Boughner DR, Pickering JG. Quantitative assessment of myocardial collagen with picrosirius red staining and circularly polarized light. Basic Res Cardiol. 1994;89:397–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00788278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurien BT, Scofield RH. A brief review of other notable protein detection methods on blots. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;536:557–571. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-542-8_56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapuscinski J. DAPI: a DNA-specific fluorescent probe. Biotechnic & histochemistry : official publication of the Biological Stain Commission. 1995;70:220–233. doi: 10.3109/10520299509108199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burn SF. Detection of beta-galactosidase activity: X-gal staining. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;886:241–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-851-1_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, et al. Lgr5 homologues associate with Wnt receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature. 2011;476:293–297. doi: 10.1038/nature10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novak A, Dedhar S. Signaling through beta-catenin and Lef/Tcf. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;56:523–537. doi: 10.1007/s000180050449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willis CL, Camire RB, Brule SA, Ray DE. Partial recovery of the damaged rat blood-brain barrier is mediated by adherens junction complexes, extracellular matrix remodeling and macrophage infiltration following focal astrocyte loss. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B, Yu HM, Hsu W. Craniosynostosis caused by Axin2 deficiency is mediated through distinct functions of beta-catenin in proliferation and differentiation. Dev Biol. 2007;301:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.physletb.2003.10.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter AC, Rao S, Wells JM, Campbell K, Lang RA. Generation of mice with a conditional null allele for Wntless. Genesis. 2010;48:554–558. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banziger C, Soldini D, Schutt C, Zipperlen P, Hausmann G, Basler K. Wntless, a conserved membrane protein dedicated to the secretion of Wnt proteins from signaling cells. Cell. 2006;125:509–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lallier TE, Spencer A. Use of microarrays to find novel regulators of periodontal ligament fibroblast differentiation. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:93–109. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lallier TE, Spencer A, Fowler MM. Transcript profiling of periodontal fibroblasts and osteoblasts. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1044–1055. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.7.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matheson S, Larjava H, Hakkinen L. Distinctive localization and function for lumican, fibromodulin and decorin to regulate collagen fibril organization in periodontal tissues. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40:312–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2005.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matias MA, Li H, Young WG, Bartold PM. Immunohistochemical localization of fibromodulin in the periodontium during cementogenesis and root formation in the rat molar. J Periodontal Res. 2003;38:502–507. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe T, Kubota T. Characterization of fibromodulin isolated from bovine periodontal ligament. J Periodontal Res. 1998;33:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang GT, Gronthos S, Shi S. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: their biology and role in regenerative medicine. J Dent Res. 2009;88:792–806. doi: 10.1177/0022034509340867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, et al. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 2004;364:149–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glinka A, Wu W, Delius H, Monaghan AP, Blumenstock C, Niehrs C. Dickkopf-1 is a member of a new family of secreted proteins and functions in head induction. Nature. 1998;391:357–362. doi: 10.1038/34848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han XL, Liu M, Voisey A, et al. Post-natal effect of overexpressed DKK1 on mandibular molar formation. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1312–1317. doi: 10.1177/0022034511421926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heo JS, Lee SY, Lee JC. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling enhances osteoblastogenic differentiation from human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. Molecules and cells. 2010;30:449–454. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooker SM, Liu B, Helms JA. Role of Wnt signaling in the biology of the periodontium. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:140–147. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.ten Berge D, Brugmann SA, Helms JA, Nusse R. Wnt and FGF signals interact to coordinate growth with cell fate specification during limb development. Development. 2008;135:3247–3257. doi: 10.1242/dev.023176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling in Mesenchymal Progenitors Controls Osteoblast and Chondrocyte Differentiation during Vertebrate Skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JB, Leucht P, Lam K, et al. Bone regeneration is regulated by wnt signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1913–1923. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joeng KS, Schumacher CA, Zylstra-Diegel CR, Long F, Williams BO. Lrp5 and Lrp6 redundantly control skeletal development in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2011;359:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason JJ, Williams BO. SOST and DKK: Antagonists of LRP Family Signaling as Targets for Treating Bone Disease. Journal of osteoporosis. 2010;2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/460120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myung PS, Takeo M, Ito M, Atit RP. Epithelial wnt ligand secretion is required for adult hair follicle growth and regeneration. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:31–41. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steigman S, Michaeli Y, Yitzhaki M, Weinreb M. A three-dimensional evaluation of the effects of functional occlusal forces on the morphology of dental and periodontal tissues of the rat incisor. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1269–1274. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680081101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watarai H, Warita H, Soma K. Effect of nitric oxide on the recovery of the hypofunctional periodontal ligament. J Dent Res. 2004;83:338–342. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Usumi-Fujita R, Hosomichi J, Ono N, et al. Occlusal hypofunction causes periodontal atrophy and VEGF/VEGFR inhibition in tooth movement. Angle Orthod. 2013;83:48–56. doi: 10.2319/011712-45.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leblond CP. Classification of Cell Populations on the Basis of Their Proliferative Behavior. National Cancer Institute monograph. 1964;14:119–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim WH, Liu B, Cheng D, et al. Wnt signaling regulates pulp volume and dentin thickness. J Bone Miner Res. 2013 doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leong NL, Hurng JM, Djomehri SI, Gansky SA, Ryder MI, Ho SP. Age-related adaptation of bone-PDL-tooth complex: Rattus-Norvegicus as a model system. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gabet Y, Bab I. Microarchitectural changes in the aging skeleton. Current osteoporosis reports. 2011;9:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s11914-011-0072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Couve E, Osorio R, Schmachtenberg O. The amazing odontoblast: activity, autophagy, and aging. J Dent Res. 2013;92:765–772. doi: 10.1177/0022034513495874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin LM, Rosenberg PA. Repair and regeneration in endodontics. International endodontic journal. 2011;44:889–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allsopp RC, Vaziri H, Patterson C, et al. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10114–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi J, Southworth LK, Sarin KY, et al. TERT promotes epithelial proliferation through transcriptional control of a Myc- and Wnt-related developmental program. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Toh L, Lau P, Wang X. Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) is a novel target of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in human cancer. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.368282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strong MA, Vidal-Cardenas SL, Karim B, Yu H, Guo N, Greider CW. Phenotypes in mTERT(+)/(-) and mTERT(-)/(-)mice are due to short telomeres, not telomere-independent functions of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:2369–2379. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05312-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffmeyer K, Raggioli A, Rudloff S, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates telomerase in stem cells and cancer cells. Science. 2012;336:1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1218370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Park JI, Venteicher AS, Hong JY, et al. Telomerase modulates Wnt signalling by association with target gene chromatin. Nature. 2009;460:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature08137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stower H. Telomeres: stem cells, cancer and telomerase linked by WNT. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:480. doi: 10.1038/nrm3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greider CW. Molecular biology. Wnt regulates TERT--putting the horse before the cart. Science. 2012;336:1519–1520. doi: 10.1126/science.1223785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]