Abstract

Natural populations of free-living protists often exhibit high-levels of intraspecific diversity, yet this is puzzling as classic evolutionary theory predicts dominance by genotypes with high fitness, particularly in large populations where selection is efficient. Here, we test whether negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS) plays a role in the maintenance of diversity in the marine flagellate Oxyrrhis marina using competition experiments between multiple pairs of strains. We observed strain-specific responses to frequency and density, but an overall signature of NFDS that was intensified at higher population densities. Because our strains were not selected a priori on the basis of particular traits expected to exhibit NFDS, these data represent a relatively unbiased estimate of the role for NFDS in maintaining diversity in protist populations. These findings could help to explain how bloom-forming plankton, which periodically achieve exceptionally high population densities, maintain substantial intraspecific diversity.

Keywords: selection, frequency dependence, density dependence, diversity, plankton

1. Introduction

Many free-living protists exhibit high levels of intraspecific diversity [1–4] despite their large population sizes, which offer the potential for natural selection to operate efficiently and fix the fittest genotype(s). Negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS) is a general mechanism that can maintain intraspecific diversity [5–7]. NFDS favours rare genotypes which subsequently increase in frequency to become common and are therefore disfavoured by selection, thereby allowing multiple genotypes to stably coexist.

NFDS is likely to interact with population density [8–14], becoming stronger at higher population densities owing to the intensification of competition, which could increase the potential for NFDS to maintain intraspecific variation. This interaction between NFDS and population density was first experimentally observed more than half a century ago in classic experiments with insects [8,9] and has since been examined theoretically [10,11] and observed empirically in a range of species [12–14]. Largely owing to the difficulties in distinguishing among multiple genotypes of protist species there have been no experimental tests of a role for NFDS in the maintenance of genetic diversity in these ecologically important organisms. The recent development of molecular methods now means it is feasible to study frequency-dependent intraspecific competition in protists [15].

Here, we provide, to our knowledge, the first experimental test for the operation of NFDS in a protist, the model flagellate Oxyrrhis marina. We estimated selection coefficients [16] for multiple pairs of strains at a range of starting frequencies and at several population densities that were representative of natural populations [17]. We observed strain-specific variation in responses but an overall signature of NFDS which was strengthened at higher population densities, suggesting a role for NFDS in maintaining the high intraspecific diversity observed in many natural protist populations.

2. Methods and materials

(a). Model species

We quantified instantaneous selection rates [16] using seven strains of the marine flagellate O. marina Dujardin 1895 that were isolated from European North Atlantic coastal sites: EST02 (Estoril, Portugal), FAR01 (Faro, Portugal), ROS03 (Roscoff, France), PLY01 (Plymouth, UK), BGN01 (Bergen, Norway), BOD01 (Bodø, Norway) and TMO01 (Tromsø, Norway; electronic supplementary material, table S1). All strains of O. marina were isolated from seawater samples taken from tide pools and maintained at 16°C at a light intensity of approximately 80 μmol photons m−2 on a 14 L : 10 D cycle [18]. Media was 32 PSU sterile filtered artificial seawater (SASW) enriched with f/2 (Sigma Aldrich, UK) and inoculated with Dunaliella primolecta at a cell density of approximately 3 × 105 cells ml−1 as a prey. Stock cultures were sub-cultured once per month. Pre-experimental cultures were created at least one month prior to experiments, without addition of f/2, and by replacing D. primolecta with heat-killed Escherichia coli [18] at a density of 1.25–2.5 × 106 CFU ml−1 as food. Depending on Oxyrrhis density, fresh food was added to cultures every 2–5 days.

(b). Frequency-density effects on selection experiments

Selection experiments to test for frequency and density dependence were performed by co-culturing six pairs of strains to estimate instantaneous selection coefficients [16]. Strain pair combinations were selected on the basis of the strain pairs differing at microsatellites alleles so that we could use microsatellite genotyping assays to estimate strain frequencies [15]; choice of pairs is therefore random with respect to strain ecological characteristics. Experimental microcosms were initiated at three initial frequency treatments (0.1, 0.5, 0.9) of the target strain and three total population density treatments (500, 2000 and 5000 cells ml−1) in a full factorial design with three replicates for each combination. Microcosms were 50 ml centrifuge tubes containing 50 ml SASW and heat-killed E. coli at a density of approximately 1.25–2.5 × 106 CFU ml−1. After gentle mixing, 10 ml subsamples were taken from each microcosm at 0 and 48 h and the frequency of each strain was estimated using allele specific quantitative-PCR on microsatellite loci [15] (electronic supplementary material, Methods S1). Given a growth rate of approximately 0.388 ± 0.05 d−1 in our O. marina strains, the short incubations prevented the realized population densities of density treatments from overlapping even with exponential growth.

(c). Data analysis

Selection coefficients (s), a measure of the rate of change in strain frequencies, for a target strain versus a non-target strain were estimated from the slope of the natural log of the strain ratio versus time [16]. A global model (i.e. including all pairwise assays) of selection coefficients was analysed using a mixed effects model, with random slopes and s as the dependent variable, density and frequency as fixed effects, and strain pair as a random effect using the R package ‘lme4’ [19]. Owing to the non-independent and reciprocal nature of selection coefficients (where for a given pair of strains the value of s for the target strain is equal to the negative value of s for its competitor) the strain with the positive mean s across treatments was designated the target strain.

To investigate interactions between density and frequency upon the strength of selection, further analyses were performed independently on frequency dependence within density treatments, by ANOVA, using a simple main effects test with an adjusted α-value of 0.017. Frequency and density dependence on selection coefficients was also tested for each pair of strains independently by two-way ANOVA, with s as the dependent variable and frequency and density as factors. Owing to the arbitrary designation of a strain as ‘target’ (i.e. based on it having a mean positive selection coefficient) and to test for competitor-specific effects against the same strain, we performed additional analyses by assigning two ‘focal’ strains: EST02 (Portugal) and BGN01 (Norway) which represent different populations of origin.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R v. 3.1.0 (R Core Development Team, 2014) and all data are presented as mean ±1 s.e.

3. Results

(a). Frequency- and density-dependent selection

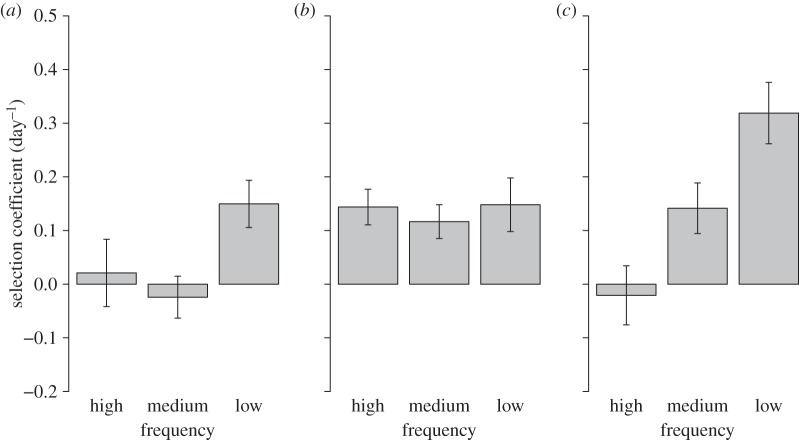

Across all experiments there were significant interactions between frequency and density, frequency and strain pair, and density and strain pair on selection coefficients (mixed effects model, χ24 = 26.7, p < 0.001). The significant interaction between frequency and density is explained by weak or a lack of significant frequency dependence at low (simple main effects ANOVA, F2,51 = 3.30, p = 0.048) and medium (simple main effects ANOVA, F2,51 = 0.19, p = 0.83) population densities but strong, significant NFDS at high population densities (simple main effects ANOVA, F2,51 = 10.16, p < 0.001; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean selection coefficient for seven strains of Oxyrrhis marina relative to a competitor at (a) low (500), (b) medium (2000), and (c) high (5000 cells ml−1) population densities (panels) and high (0.9), medium (0.5) and low (0.1) initial frequencies (bars).

With EST02 and BGN01 as ‘focal’ strains, we observed similar responses of selection to frequency and density. For EST02, there was an interaction between frequency and density on selection (two-way ANOVA, F4,70 = 3.188, p < 0.05) that followed the pattern described above, but with no interaction with competitor strain; this suggests that EST02 responded to changes in frequency and density regardless of its competitor. For BGN01, there was a significant three-way interaction between density, frequency and the competitor (three-way ANOVA, F8,54 = 2.248, p < 0.05) that suggests a competitor-specific response to frequency and density for this strain.

Owing to the variation in responses exhibited by strain pairs, we also analysed the effects of frequency and density for each individual strain combination. Our experimental microcosms revealed complexity with all possible combinations of frequency dependence (BGN01 and TMO01), density dependence (ROS03 and EST02) and interactions between density and frequency dependence (PLY01 and BGN01; EST02 and BOD02), and two pairs of strains (EST02 and BGN01; EST02 and FAR01) showing no significant effect of frequency or density on selection (table 1). This suggests that the selection response to frequency and density also depends upon the combination of genotypes.

Table 1.

Two-way ANOVA statistics for frequency and density dependence of selection coefficients in Oxyrrhis marina microcosms. (Model results are presented with interactions, where significant, or otherwise with both factors.)

| target strain | competitor strain | factor | d.f. | sum squares | mean square | f | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS03 | EST02 | density | 2 | 0.3955 | 0.1978 | 8.984 | 0.0014 |

| frequency | 2 | 0.1108 | 0.0554 | 2.517 | 0.1037 | ||

| residuals | 22 | 0.4843 | 0.0220 | ||||

| BGN01 | TMO01 | density | 2 | 0.2115 | 0.1058 | 3.042 | 0.0682 |

| frequency | 2 | 1.8189 | 0.9094 | 26.159 | <0.0001 | ||

| residuals | 22 | 0.7649 | 0.3048 | ||||

| EST02 | BOD02 | density | 2 | 0.0249 | 0.0124 | 0.697 | 0.5111 |

| frequency | 2 | 0.0237 | 0.0119 | 0.664 | 0.5267 | ||

| density × frequency | 4 | 0.2913 | 0.0728 | 4.080 | 0.0158 | ||

| residuals | 18 | 0.3213 | 0.0179 | ||||

| PLY01 | BGN01 | density | 2 | 0.3337 | 0.1669 | 16.090 | <0.0001 |

| frequency | 2 | 0.1439 | 0.0720 | 6.940 | 0.0058 | ||

| density × frequency | 4 | 0.2694 | 0.0673 | 6.494 | 0.0020 | ||

| residuals | 18 | 0.1867 | 0.0104 | ||||

| EST02 | BGN01 | density | 2 | 0.0070 | 0.0035 | 0.161 | 0.852 |

| frequency | 2 | 0.0612 | 0.0306 | 1.413 | 0.265 | ||

| residuals | 22 | 0.4767 | 0.0216 | ||||

| FAR01 | EST02 | density | 2 | 0.0389 | 0.0194 | 0.767 | 0.476 |

| frequency | 2 | 0.0677 | 0.0339 | 1.336 | 0.283 | ||

| residuals | 22 | 0.5574 | 0.0253 |

4. Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms that maintain intraspecific variation in natural populations is an important challenge in evolutionary ecology, as this variation underpins numerous fundamental processes [20,21], including adaptation to environmental change (e.g. [22]). We observed an overall signature of NFDS between pairs of competing strains of O. marina, which was intensified at higher population densities. This finding may be especially relevant to understand the evolutionary ecology of bloom-forming plankton, which periodically achieve exceptionally high population densities and yet often maintain substantial intraspecific diversity [23,24]. It is important to note, though, that within this overall pattern there was extensive strain-specific variation in the response to both frequency and density, highlighting the potential complexity of competitive interactions within natural protist populations. Nevertheless, because our strain selection was not based a priori on particular traits or phenotypes expected to exhibit NFDS (e.g. public goods scenarios in bacteria [25] or sexual selection between phenotypic morphs in animals [26]) our data represent a relatively unbiased estimate of the role of NFDS. Our data provide the first evidence to our knowledge that NFDS is a plausible mechanism maintaining the high levels of intraspecific diversity typical of natural free-living protist populations. The next challenge is to incorporate the interaction between frequency, density and genetic diversity into models that attempt to predict population dynamics in natural systems, for example, the seasonal dynamics of plankton blooms and the responses of protist populations to environmental change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Colin Beale and Chris Thomas for useful discussions that led to this research.

Data accessibility

Data available from the Dryad Digital Respository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.nk52s.

Authors' contributions

E.J.A.M. conceived the study, performed experiments, analysed data, interpreted results and drafted the manuscript. P.C.W., C.D.L. and M.A.B. conceived the study, interpreted results and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

E.J.A.M. was supported by a NERC research studentship (NE/H025472/2) as part of the UK Ocean Acidification Research Programme.

References

- 1.Logares R, Boltovskoy A, Bensch S, Laybourn-Parry J, Rengefors K. 2009. Genetic diversity patterns in five protist species occurring in lakes. Protist 160, 301–317. ( 10.1016/j.protis.2008.10.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowe CD, Montagnes DJ, Martin LE, Watts PC. 2010. High genetic diversity and fine-scale spatial structure in the marine flagellate Oxyrrhis marina (Dinophyceae) uncovered by microsatellite loci. PLoS ONE 5, e15557 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0015557) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harnstrom K, Ellegard M, Andersen TJ, Godhe A. 2011. Hundred years of genetic structure in a sediment revived diatom population. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 4252–4257. ( 10.1073/pnas.1013528108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebret K, Kritzberg ES, Figueroa R, Rengefors K. 2012. Genetic diversity within and genetic differentiation between blooms of a microalgal species. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 2395–2404. ( 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02769.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke B. 1964. Frequency-dependent selection for the dominance of rare polymorphic genes. Evolution 18, 364–369. ( 10.2307/2406348) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray J. 1972. Genetic diversity and natural selection. Edinburgh, UK: Oliver & Boyd. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Judson OP. 1995. Preserving genes: a model of the maintenance of genetic variation in a metapopulation under frequency-dependent selection. Genet. Res. 65, 175–191. ( 10.1017/S0016672300033267) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewontin RC. 1955. The effects of population density and composition on viability in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 9, 27–41. ( 10.2307/2405355) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan RL, Sokal RR. 1965. Further experiments on competition between strains of house flies. Ecology 46, 172–182. ( 10.2307/1935268) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eadie JM, Fryxell JM. 1992. Density dependence, frequency dependence, and alternative nesting strategies in goldeneyes. Am. Nat. 140, 621–641. ( 10.1086/285431) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newton MR, Kinkel LL, Leonard KJ. 1998. Determinants of density- and frequency-dependent fitness in competing plant pathogens. Phytopathology 88, 45–51. ( 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.1.45) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levitan DR, Ferrell DL. 2006. Selection on gamete recognition proteins depends on sex, density, and genotype frequency. Science 312, 267–269. ( 10.1126/science.1122183) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer JR, Kassen R. 2007. The effects of competition and predation on diversification in a model adaptive radiation. Nature 446, 432–435. ( 10.1038/nature05599) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mappes T, Koivula M, Koskela E, Oksanen TA, Savolainen T, Sinervo B. 2008. Frequency and density-dependent selection on life-history strategies: a field experiment. PLoS ONE 3, e1687 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0001687) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minter EJA, Lowe CD, Brockhurst MA, Watts PC. 2015. A rapid and cost-effective quantitative microsatellite genotyping protocol to estimate intraspecific competition in protist microcosm experiments. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 315–323. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12321) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chevin LM. 2011. On measuring selection in experimental evolution. Biol. Lett. 7, 210–213. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.0580) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montagnes DJS, Lowe CD, Martin L, Watts PC, Downes-Tettmar N, Yang Z, Roberts EC, Davidson K. 2010. Oxyrrhis marina growth, sex and reproduction. J. Plankton Res. 33, 615–627. ( 10.1093/plankt/fbq111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowe CD, Martin LE, Roberts EC, Watts PC, Wootton EC, Montagnes DJS. 2011. Collection, isolation and culturing strategies for Oxyrrhis marina. J. Plankton Res. 33, 569–578. ( 10.1093/plankt/fbq161) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates D, Machler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. 2014. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. (http://arxiv.org/abs/1406.5823) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes AR, Inouye BD, Johnson MT, Underwood N, Vellend M. 2008. Ecological consequences of genetic diversity. Ecol. Lett. 11, 609–623. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01179.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolnick DI, et al. 2011. Why intraspecific trait variation matters in community ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 183–192. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2011.01.009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markert JA, Champlin DM, Gutjahr-Gobell R, Grear JS, Kuhn A, McGreevy TJ, Jr, Roth A, Bagley MJ, Nacci DE. 2010. Population genetic diversity and fitness in multiple environments. BMC Evol. Biol. 10, 205 ( 10.1186/1471-2148-10-205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rynearson TA, Armbrust EV. 2005. Maintenance of clonal diversity during a spring bloom of the centric diatom Ditylum brightwellii. Mol. Ecol. 14, 1631–1640. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02526.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saravanan V, Godhe A. 2010. Genetic heterogeneity and physiological variation among seasonally separated clones of Skeletonema marinoi (Bacillariophyceae) in the Gullmar Fjord, Sweden. Eur. J. Phycol. 45, 177–190. ( 10.1080/09670260903445146) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross-Gillespie A, Gardner A, West SA, Griffin AS. 2007. Frequency dependence and cooperation: theory and a test with bacteria. Am. Nat. 170, 331–342. ( 10.1086/519860) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinervo B, Lively CM. 1996. The rock-paper-scissors game and the evolution of alternative male strategies. Nature 380, 240–243. ( 10.1038/380240a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the Dryad Digital Respository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.nk52s.