Abstract

Theories on the origin of vertebrate teeth have long focused on chondrichthyans as reflecting a primitive condition—but this is better informed by the extinct placoderms, which constitute a sister clade or grade to the living gnathostomes. Here, we show that ‘supragnathal’ toothplates from the acanthothoracid placoderm Romundina stellina comprise multi-cuspid teeth, each composed of an enameloid cap and core of dentine. These were added sequentially, approximately circumferentially, about a pioneer tooth. Teeth are bound to a bony plate that grew with the addition of marginal teeth. Homologous toothplates in arthrodire placoderms exhibit a more ordered arrangement of teeth that lack enameloid, but their organization into a gnathal, bound by layers of cellular bone associated with the addition of each successional tooth, is the same. The presence of enameloid in the teeth of Romundina suggests that it has been lost in other placoderms. Its covariation in the teeth and dermal skeleton of placoderms suggests a lack of independence early in the evolution of jawed vertebrates. It also appears that the dentition—manifest as discrete gnathal ossifications—was developmentally discrete from the jaws during this formative episode of vertebrate evolution.

Keywords: jawed vertebrates, placoderm, dental development, evolution, modularity

1. Introduction

Theories on the evolutionary origin of teeth have long been rooted in the condition manifest by chondrichthyans, as the most distant living outgroup to humans and because they exhibit a comparatively simple pattern of tooth replacement. However, their apparent simplicity is secondary given that the extinct placoderms, which constitute the sister lineage(s) to all other jawed vertebrates, exhibit a greater diversity and complexity of dentitions that better inform the nature of an ancestral gnathostome dentition. Dental development is best known in the arthrodiran placoderms, where teeth aggregrate to comprise gnathals ossified to the bony shaft of the lower jaw and the palatoquadrate [1]. This dentition is statodont; teeth were added successionally, replacing teeth that were not shed, bound together by an ossification associated with tooth addition [1]. However, arthrodires are derived regardless of whether placoderms are considered a clade or a grade [2,3] and the existence and nature of the dentition in other placoderm lineages are poorly known. Here, we describe the structure and growth of the supragnathal of Romundina stellina, a member of the acanthothoracid placoderms—considered an outgroup to a monophyletic Placodermi [4], or else an early branching lineage of paraphyletic ‘placoderms' [5]. As such, in comparison to other placoderms and crown-gnathostomes, Romundina might better inform the plesiomorphic nature of gnathostome dentitions. We used synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM) to obtain a high-resolution volumetric characterization of gnathals from Romundina and, for comparison, the arthrodire Compagopiscis croucheri. We subjected these datasets to computed tomographic analysis to elucidate the structure and infer the development of these skeletal structures.

2. Material and methods

The supragnathal and associated skeletal elements are from acid-insoluble residues associated with the holotype of R. stellina, from the Early Devonian (Lochkovian) of Prince of Wales Island, Canada [6], housed in the Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm (NRM-PZ). For comparison, we studied posterior supragnathals of C. croucheri from the Upper Devonian, Frasnian, Gogo Formation of Australia, reposited at the Natural History Museum London (NHMUK PV). Volumetric characterization of the specimens was achieved using SRXTM [7] at the TOMCAT (X02DA) beamline of the Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institut, Switzerland (voxel dimensions 0.74 and 1.85 µm) and a SkyScan 1172 XTM at the University of Bristol (voxel dimensions 10 µm); the raw slice data are available at http://dx.doi.org/10.5523/bris.7h9gynbsui4u1hap471inrlua and as movie files in the electronic supplementary material. These data were analysed using AVIZO 8.01 (www.fei.com).

3. Results

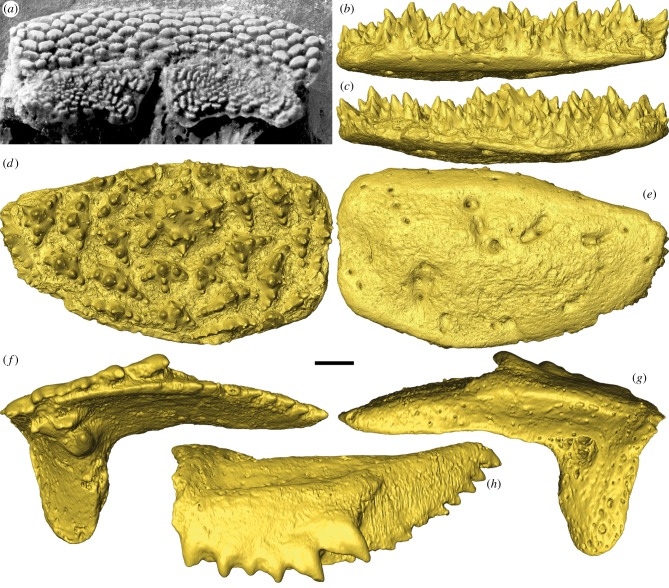

Only the upper dental plates (supragnathals) are known for Romundina, described from the palatal surface of an endocranium as ‘a pair of symmetrical flat plates with a specific ornament combining radiating and concentric rows with a centrifugal growth’ [4, p. 114]. The upper dental plates are flat and oval-shaped with an ornament of multi-cuspid tubercles (figure 1a). The new material is identified as a gnathal plate of Romundina on grounds of equivalent size and similar shape, and its derivation in association with the holotype of R. stellina [6]. The gnathal has a prominent central tubercle with a central cusp from which six radial ridges extend, each bearing a series of aligned cusps. This is surrounded by smaller tubercles, each exhibiting the same basic arrangement of cusps, though one or more of the radial ridges may not be developed. Thus, marginal tubercles exhibit elongate ridges aligned with the circumference of the gnathal plate (figures 1a,d and 2a).

Figure 1.

Acanthothoracid placoderm (same specimen as in [4]) and surface renderings (gold) of Romundina stellina and Compagopiscis croucheri. Upper dental plates (anterior supragnathals, ASG) in occlusal view (a). Right ASG of R. stellina (NRM-PZ P.15956) based on SRXTM data (b–e). (b) Distal, (c) proximal, (d) occlusal and (e) dorsal views. Left posterior supragnathal (PSG) of C. croucheri (NHMUK PV P.50943), based on MicroCT data (f–h). (f) Occlusal, (g) dorsal and (h) distal views. Scale bar represents 1.68 mm in (a), 178 µm in (b–e) and 206 µm in (f–h).

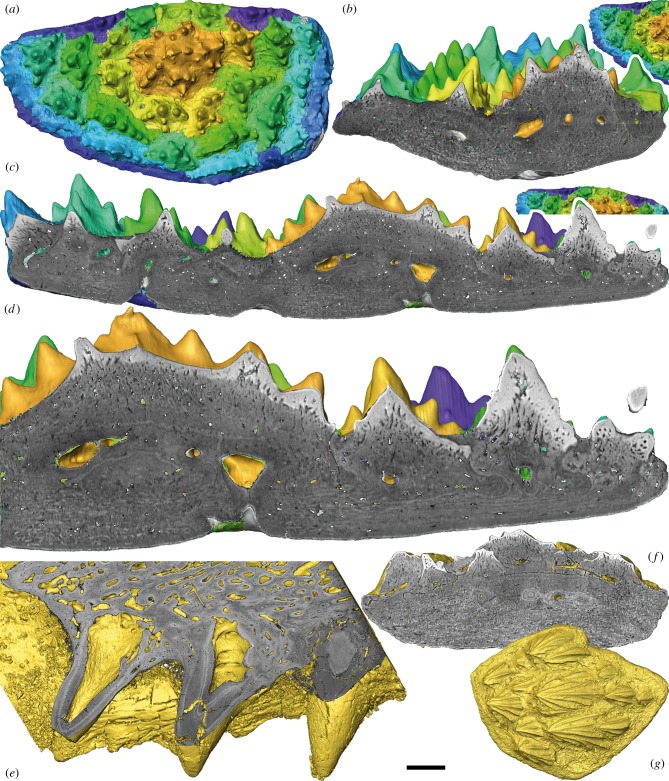

Figure 2.

Segmentation and virtual sections of SRXTM characterizations of a Romundina stellina supragnathal (NRM-PZ P.15956), dermal scale (NRM-PZ P.15952) and Compagopiscis croucheri supragnathal (NHMUK PV P.57629). (a–d) Right ASG of R. stellina. (a) Segmented sclerochronology of the dental plate following lines of arrested growth. Colour scheme (from gold to purple) represents the sequence of tooth addition. (b) Transverse and (c) longitudinal virtual sections showing addition of teeth and basal layer. (d) Detail of (c) showing enameloid/semidentine border and Sharpey's fibres. (e) Detailed virtual section of the right PSG of C. croucheri. (f) Virtual section and (g) dorsal view of the dermal scale of R. stellina. Scale bar represents 180 µm in (a), 97 µm in (b), 86 µm in (c), 50 µm in (d), 157 µm in (e), 96 µm in (f) and 224 µm in (g).

Tomographic sections reveal that the gnathal plate comprises three layers: a superficial layer composed of tubercles, a medial vascular layer and a basal lamellar layer (figure 2b–d). The tubercles generally lack a coherent vascular cavity, but they comprise dentine with odontoblast lacunae, characteristic of semidentine, that converge on local chambers associated with the middle vascular layer. The dentine exhibits an irregular boundary with an outer hypermineralized capping layer of enameloid that is continuous between component cusps of each tubercle and permeated by the odontoblast canaliculi (figure 2b–d). Inner areas of dentine tissues with canaliculi and cell lacunae are characteristic for semidentine (figure 2d). The vascular middle layer is dominated by canals that extend through the basal and the superficial layers, opening between tubercles. The basal layer consists of lamellar bone that is generally organized into a plywood-like structure characteristic of isopedin, though it comprises fibre bundles that are approximately circular in cross-section, akin to the osteostracan and galeaspid dermal skeletons, rather than the sheet-like organization seen in actinopterygians [8]. This structure is permeated by Sharpey's fibres centrally (figure 2b–d) and disintegrates locally into spheritic mineralization characteristic of rapid growth or the absence of a coherent collagen matrix [9].

The tomographic data also reveal clearly that the tubercles were added episodically to the margins of the gnathal plate, evidenced by growth arrest lines that occur between tubercles that developed on the margins of older, earlier formed, tubercles (figure 2b–d). These growth lines can be traced continuing through the middle and basal layers, demonstrating that the bony plate grew in width and thickness in association with the addition of tubercles at the margins. Tracing these growth lines digitally revealed that the tubercles were added marginally in concert (figure 2b–d). Thus, the tubercles were added radially in respect of the pioneer, but restricted by the distal limit of the oral cavity where the gnathal plates abutted the premedian plate, as may be inferred in comparison to supragnathal plates in situ (figure 1a).

The supragnathal plates of the brachythoracid arthrodire C. croucheri occur bilaterally as separate anterior and posterior elements; either the anterior element is homologous to the single bilateral supragnathal plates in Romundina or else they are perhaps collectively equivalent. They each have a central cusp, from which branch three rows, only two of which comprise more than a few cusps (figure 1f–h). Tomographic sections reveal that each cusp has a distinct and voluminous pulp cavity (figure 2e). Growth arrest lines indicate that the cusps were added in succession, to the margin of the next oldest cusp within the row, and relative age of the cusps is also reflected in the degree to which the pulp cavities are centripetally infilled by dentine. The addition of each cusp is continuous with the bone added to the basal plate uniting the component cusps. The growth lines become indistinct where remodelling of the vasculature has occurred (figure 2e).

4. Discussion

The surface morphology of the tubercles comprising the supragnathal in Romundina is quite distinct from the morphology of the dermal tubercles, though they have a common composition. Given their statodont pattern of replacement, with new tubercles added at the margins of the oral surface, their toothlike composition, and the homology of the gnathals to the supragnathals of arthrodires such as Compagopiscis, which have already been interpreted as teeth [1], we interpret the supragnathals of Romundina as comprising teeth. Nevertheless, the structure and composition of the supragnathal toothplate in Romundina is surprising given what has been known previously concerning the structure of placoderm dental elements. The simple radial organization of the tubercles is similar to the compound oral denticles in the jawless thelodont Loganellia [10], but it is quite distinct from the strictly ordered arrangement of the tubercles comprising the gnathals of arthrodire placoderms, including the supragnathals described here from Compagopiscis, where the tubercles are monocuspid and arranged along discrete vectors [1]. Conversely, the multicuspid gnathal tubercles in Romundina are considerably more complex. These differences are perhaps reflected in the differing degrees of gnathal occlusion, where the supra- and infra-gnathals of Compagopiscis should be envisaged to occlude with precision, whereas it is difficult to conceive any meaningful degree of occlusion in Romundina, perhaps because it would be precluded by the complex interdigitating, space-filling morphology of the tubercles comprising the functional surface of the gnathals. Thus, these differences may as equally reflect poorer constraint of jaw articulation, as of dental development, in the earliest jawed vertebrates.

The presence of an enameloid capping layer to the teeth of Romundina is not unusual in comparison to the composition of osteichthyan and chondrichthyan teeth; however, it contrasts with the structure of teeth in arthrodires, which have been shown to lack enameloid [1]. Enameloid is also present in the external dermal tubercles of Romundina (figure 2f,g), which is a primitive feature for ostracoderms [9], but it is unusual for most placoderms where enameloid is absent through loss [11]. This suggests that the absence of enameloid from the teeth of arthrodires [1] is also a consequence of loss and that the teeth of the earliest jawed vertebrates included a hypermineralized capping layer of enameloid.

Indeed, the coordinated presence versus absence of enameloid associated with the dermal and oral odontodes may be more illuminating, suggestive of the non-independence of these skeletal systems in the earliest jawed vertebrates. This view is entirely compatible with the view that teeth evolved through the extension of odontogenic competence from external to internal epithelia, but incompatible with the view that internal and external odontodes evolved independently from a non-skeletal antecedent organ system [12].

In either instance, the organization of teeth into gnathals that occur distinct from other aspects of the dermal and endoskeletal systems appears to be widespread among placoderms, including acanthothoracids and arthrodires. As such, this may reflect a primitive condition for jawed vertebrates, and the intimate association of teeth and jaws may be an entirely derived feature of osteichthyans.

5. Conclusion

The gnathals of Romundina may reflect a primitive condition for placoderms and, indeed, jawed vertebrates more generally: discrete developmental units that comprise teeth composed of dentine and capped with enameloid. As such, the search for the origin of teeth must be extended deeper into gnathostome phylogeny. However, the organization of teeth and their intimate developmental association with jaws appear to be derived phenomena that evolved later in jawed vertebrate phylogeny.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Goujet for the photo of specimen CPW. 9A (figure 1a) and acknowledge the help of John Cunningham, Duncan Murdock, Sam Giles, A. Hetherington, Federica Marone and Marco Stampanoni. We thank three anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Data accessibility

Data used in this manuscript are archived at http://dx.doi.org/10.5523/bris.7h9gynbsui4u1hap471inrlua and as movie files in electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

Both authors designed the study and contributed equally to the manuscript. M.R. carried out the segmenting of the scans. Both authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We received funding from EU FP7 grant agreement 312284 (CALIPSO), Marie Curie Action (to M.R., P.C.J.D.), ERC Grant no. 311092 (to Martin Brazeau); NERC Standard grant no. NE/G016623/1 (to P.C.J.D.), the Paul Scherrer Institute, a Royal Society Wolfson Merit and a Leverhulme Trust Research Fellowship (to P.C.J.D.).

References

- 1.Rücklin M, Donoghue PC, Johanson Z, Trinajstic K, Marone F, Stampanoni M. 2012. Development of teeth and jaws in the earliest jawed vertebrates. Nature 491, 748–751. ( 10.1038/nature11555) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brazeau MD. 2009. The braincase and jaws of a Devonian ‘acanthodian’ and modern gnathostome origins. Nature 457, 305–308. ( 10.1038/nature07436) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis SP, Finarelli JA, Coates MI. 2012. Acanthodes and shark-like conditions in the last common ancestor of modern gnathostomes. Nature 486, 247–250. ( 10.1038/nature11080) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goujet D, Young GC. 2004. Placoderm anatomy and phylogeny: new insights. In Recent advances in the origin and early radiation of vertebrates (eds Arratia G, Wilson MVH, Cloutier R.), pp. 109–126. München: Pfeil. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupret V, Sanchez S, Goujet D, Tafforeau P, Ahlberg PE. 2014. A primitive placoderm sheds light on the origin of the jawed vertebrate face. Nature 507, 500–503. ( 10.1038/nature12980) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ørvig T. 1975. Description, with special reference to the dermal skeleton, of a new radotinid arthrodire from the Gedinnian of Arctic Canada. Colloque Int. CNRS 218, 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donoghue PCJ, et al. 2006. Synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy of fossil embryos. Nature 442, 680–683. ( 10.1038/nature04890) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang NZ, Donoghue PCJ, Smith MM, Sansom IJ. 2005. Histology of the galeaspid dermoskeleton and endoskeleton, and the origin and early evolution of the vertebrate cranial endoskeleton. J. Vert. Paleontol. 25, 745–756. ( 10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0745:HOTGDA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donoghue PCJ, Sansom IJ, Downs JP. 2006. Early evolution of vertebrate skeletal tissues and cellular interactions, and the canalization of skeletal development. J. Exp. Zool. B 306B, 278–294. ( 10.1002/jez.b.21090) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rücklin M, Giles S, Janvier P, Donoghue PCJ. 2011. Teeth before jaws? Comparative analysis of the structure and development of the external and internal scales in the extinct jawless vertebrate Loganellia scotica. Evol. Dev. 13, 523–532. ( 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00508.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles S, Rücklin M, Donoghue PCJ. 2013. Histology of ‘placoderm’ dermal skeletons: implications for the nature of the ancestral gnathostome. J. Morphol. 274, 627–644. ( 10.1002/jmor.20119) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donoghue PCJ, Rücklin M. 2014. The ins and outs of the evolutionary origin of teeth. Evol. Dev. ( 10.1111/ede.12099) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this manuscript are archived at http://dx.doi.org/10.5523/bris.7h9gynbsui4u1hap471inrlua and as movie files in electronic supplementary material.