INTRODUCTION

The most common cause of portal hypertension is liver cirrhosis, which causes so-called intrahepatic or sinusoidal portal hypertension. Other disorders including presinusoidal and postsinusoidal diseases (ie, portal vein thrombosis, schistosomiasis, veno-occlusive disease, cardiac failure) may also cause increased portal pressure. Portal hypertension likely causes hemodynamic and mucosal changes in the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This article focuses on the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) and colopathy (PHC) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Features of portal hypertensive gastropathy and colopathy

| Features | Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy | Portal Hypertensive Colopathy |

|---|---|---|

| Endoscopic characteristics | Mosaic pattern and red spots | Mosaic pattern and red spots, sometimes, vascular ectasia appearance |

|

| ||

| Pathology | Dilated capillaries and venules, no inflammation | Edema and capillary dilatation, lymphocytes and plasma cells, in lamina propria |

|

| ||

| Treatment | Iron-replacement therapy | a Iron-replacement therapy |

| Transfusions | Transfusions | |

| Portal pressure–reducing agents | Portal pressure–reducing agents | |

|

| ||

| Salvage treatment | TIPS/shunt surgery | TIPS/shunt surgery |

| APC | APC | |

| Liver transplantation | Liver transplantation | |

Current practice is based on case and case series reports.

There are insufficient data for standard recommendations in PHC bleeding.

The cause of PHG and PHC is incompletely understood. However, available data indicate that portal hypertension is a critical component. It has been recognized that mucosal changes in the gastric mucosa of patients with portal hypertension were different pathologically from inflammatory gastritis; this led to the early description “congestive gastropathy.”1 The primary pathologic change was characterized by vascular ectasia. PHG is recognized endoscopically as a mosaic-like pattern called snakeskin mucosa with or without red spots.2 Additionally, the terms portal hypertensive enteropathy3,4 and PHC5,6 were created to describe similar changes in the small bowel and colonic mucosa, respectively. PHC is characterized by erythema of the colonic mucosa, vascular lesions including cherry-red spots, telangiectasias, or angiodysplasia-like lesions.

PHG and PHC are important clinically because they may lead to chronic and/or acute GI bleeding. Both disorders are often confused with other diseases that can present similarly. Careful investigation is essential to accurately delineate the proper diagnostic needs and to start specific treatment.

PORTAL HYPERTENSIVE GASTROPATHY

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PHG in patients with cirrhosis varies from 20% to 98%.2,7–12 This variation seems to be caused by several factors, including the study of different populations and variable patient selection, different interpretation of endoscopic lesions, and lack of uniform diagnostic criteria and classification.

Some studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of PHG in patients with advanced liver disease, esophageal varices, or history of sclerotherapy or ligation for esophageal varices.7,9,10 In general, the available data suggest that PHG is often associated with more severe portal hypertension.13 It has also been suggested that the prevalence of PHG increases as esophageal varices are obliterated,2 although this point is controversial.

Clinical Findings

Most patients with PHG are asymptomatic, but a significant number of patients exhibit symptoms related to chronic GI bleeding and chronic blood loss/iron deficiency anemia. A smaller proportion of patients exhibit evidence of active GI bleeding.

Chronic bleeding from PHG has been reported to occur in 3% to 60% of patients.8,9,14,15 The definition of chronic bleeding most commonly used is decrease of hemoglobin of 2 g/dL within a 6-month time period without evidence of acute bleeding and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use.16 Other definitions include the presence of iron deficiency anemia with a positive fecal occult blood test.15

Acute GI hemorrhage is less common. The prevalence of acute GI bleeding from PHG in patients with cirrhosis has been reported to be between 2% and 12%.7–9 Most of these cases are caused by severe PHG (90%–95%).7,9 The diagnosis of acute hemorrhage from PHG is made when active hemorrhage from PHG lesions or nonremovable clots over these lesions are identified during endoscopy, or if there is evidence of portal hypertension, typical gastric lesions, and no other source of bleeding can be identified after complete evaluation of the GI tract.17

Diagnostic Modalities

The diagnosis of PHG is made at the time of endoscopic evaluation. Endoscopic features include a typical snakeskin mosaic pattern, flat or bulging red marks or red spots resembling vascular ectasias,1 or black-brown spots. The most common location for PHG is the proximal stomach (fundus and body).18,19

The simplest way to make the diagnosis is by esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Capsule endoscopy has also been used and was shown to have a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 83% when compared with esophagogastroduodenoscopy.20 Another study performed in 119 patients showed that the sensitivity of capsule endoscopy was 69% and specificity 99%.21 However, the diagnostic yield in the gastric body was significantly greater than in the fundus (100% vs 48%, respectively).21 These data suggest that its role is more important in the assessment of small bowel enteropathy.22

Classification

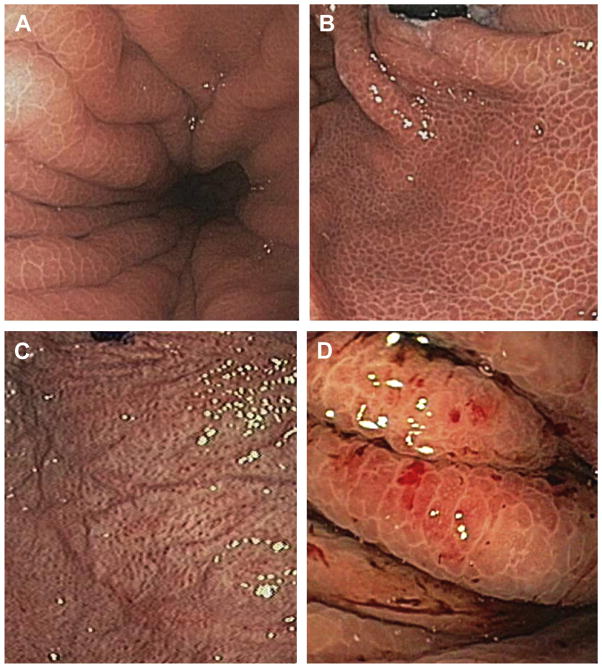

Classification of PHG is done based on the severity of its appearance. There are several proposed grading systems, but most experts recommend a two-category classification system,23,24 although a three-category system has also been proposed (Table 2).25 The two-grading classification proposed by Baveno III consensus is similar to older versions.1 PHG is classified as mild when the only change consists of a snakeskin mosaic pattern, and it is classified as severe when in addition to the mosaic pattern, flat or bulging red or black-brown spots are seen, and/or when there is active hemorrhage (Fig. 1).23

Table 2.

Classification of portal hypertensive gastropathy

| Category | Baveno III Consensus | NIEC | McCormack et al,1 1985 | Tanoue et al,25 1992 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | MLP of mild degree (without redness of the areola) | Mosaic-like pattern Mild: diffusely pink areola Moderate: flat red spot in center of pink areola Severe: diffusely red areola |

Fine speckling or scarlatina-type of rash Superficial reddening Snakeskin pattern |

Grade 1: Mild reddening Congestive mucosa |

| Moderate | N/A | N/A | N/A | Grade 2: Severe redness + fine reticular pattern in areas of raised mucosa |

| Severe | MLP + red signs or if any other red sign or brown-black spot is present | Red marks: red lesions of variable diameter, flat or slightly protruding Discrete or confluent |

Cherry-red spots, confluent or not Diffuse hemorrhage |

Grade 3: Grade 2 + point bleeding |

Abbreviations: MLP, mosaic-like pattern; NIEC, New Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treat of Esophageal Varices.

Fig. 1.

(A, B) Representative images of mild PHG. A shows a forward-viewing image of the proximal stomach. B shows a retroflex view of the cardia with the classic form of PHG, the typical “mosaic-like pattern” without significant stigmata of bleeding or erythema or edema. (C, D) Representative images of severe PHG. Red lesions of variable diameter are evident. There is often irregular mucosa. Cherry spots may be confluent or not. Slow oozing may also be seen as in D, an up-close view in the proximal stomach.

The two-category classification system has significantly better interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility and agreement.26 A recent study has shown that the endoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of PHG that were associated with a high rate of interobserver reliability are the mosaic-like pattern, red-point lesions, and cherry-red spots.27 The clinical importance of this grading system resides in the fact that patients with severe PHG have a higher chance of bleeding or to have chronic anemia than patients with mild PHG.9,28

Other Diagnostic Modalities

Nonendoscopic modalities for diagnosis of PHG have been studied. These include magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography.29,30 PHG is identified by computed tomography scan as enhancement on the inner layer of the gastric walls, which may reflect gastric congestion. In a study of 32 patients, 10 had PHG and 22 did not.29 Enhancement of the inner layer of the gastric wall in the delayed phase was observed in nine patients with PHG, and in five without portal hypertension. Magnetic resonance imaging was used to measure the diameter of the left gastric, paraesophageal, and azygos veins in 57 patients with portal hypertension. In patients with PHG, the mean diameters of these veins were not different from those in patients without PHG.30 These data suggest that imaging is at this time best reserved for experimental purposes.

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of PHG is incompletely understood. The presence of portal hypertension seems to be essential. Although studies have failed to demonstrate that there is a linear correlation between the degree of portal hypertension and the severity of PHG,10,12,31 studies that demonstrate improvement of PHG after shunt surgery or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) support the connection.32,33

The major histologic changes in PHG include dilatation of capillaries and venules in the mucosa and submucosa without significant inflammation.1 Several studies have shown that abnormalities in the mucosal microcirculation may be related to the congestion seen in PHG.13 PHG seems to develop secondary to congestion because of blockage of gastric blood drainage.32,34 A major apparent process in PHG is dysregulation of the mucosal microcirculation, which leads to mucosal hypoxia,35 altering the epithelial cell integrity by overproduction of oxygen free radicals, nitric oxide, tumor necrosis factor-α, endothelin-1, and prostaglandins.35–39 In addition, because of the impaired blood flow characteristics, and perhaps dysregulation of local cytokines, and vascular factors, the abnormal mucosa in PHG exhibits impaired healing and mechanisms of defense, which in turn may increase the risk for bleeding.40,41

Diagnostic Dilemmas

The endoscopic diagnosis of PHG includes several entities. For example, lesions typical of those found in PHG may be seen in patients with irritant injury to the gastric mucosa (ie, caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or ethanol), although PHG tends to more often be localized to the proximal stomach. One of the main considerations includes gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) or watermelon stomach. GAVE also presents with flat red spots, but usually without the mosaic pattern.42 GAVE may also appear endoscopically as streaks of erythema, seeming to emanate from the pylorus. GAVE is also usually located in the distal stomach (antrum).43 Thus, the location of the lesions (PHG, proximal stomach; GAVE, distal stomach) may help distinguish the disorders. On some occasions the red spots can coalesce throughout the entire stomach (proximal and distal) and it is called diffuse gastric vascular ectasia. In situations like this, differentiation from severe PHG is very difficult.

The differentiation between GAVE and PHG may be important because treatment is typically different. Additionally, gastric vascular ectasia, which typically presents with chronic bleeding and iron deficiency, is a relatively uncommon cause of GI hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis.44 It is also identified in patients with other diseases including chronic renal failure, bone marrow transplantation, autoimmune and connective tissue diseases including scleroderma, atrophic gastritis, pernicious anemia, and sclerodactyly.42,45–47 There does not seem to be a direct relationship between the presence of portal hypertension and GAVE,48 and management of GAVE is different than for PHG. GAVE lesions are usually treated with endoscopic thermoablative methods and respond poorly to β-blockers or TIPS.33,48

When the endoscopic diagnosis is unclear, histologic assessment of the mucosa may help (and biopsy in the absence of severe coagulopathy is generally safe). The histologic findings of GAVE include more extensive vascular ectasia, spindle cell proliferation, and fibrin thrombi and fibrohyalinosis.44

Treatment Options

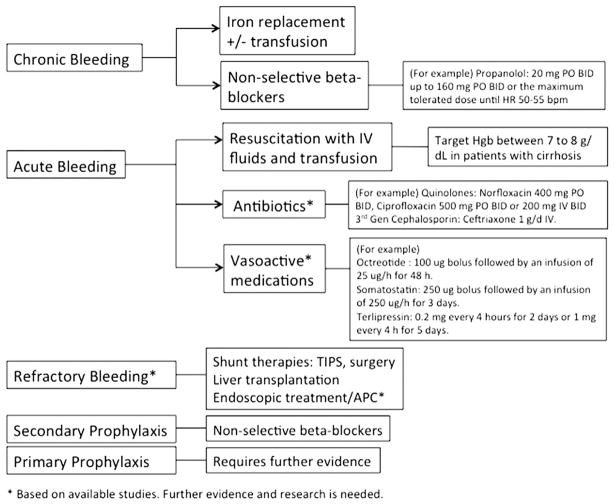

Treatment recommendations are targeted according to the presentation and differ depending on the rate of bleeding or whether the patient has specific symptoms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PHG management. Recommended approaches to therapy are shown. It is recommended to manage PHC similarly, although in patients with PHC, management is typically more individualized. APC, argon plasma coagulation.

Primary Prophylaxis

It is not uncommon to identify PHG during endoscopic screening for esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. In this scenario, the patient may be asymptomatic without any evidence of bleeding. Primary prophylaxis of GI bleeding in patients with PHG has not been assessed and it is usually not recommended. However, management in these situations needs to be done on an individual basis. The severity of PHG is an important factor to take in consideration. Mild PHG alone usually does not require primary prophylaxis. If the patient has small esophageal varices and mild PHG, the use of nonselective β-blockers may be considered because theoretically it can be of benefit for PHG.13 In patients with severe PHG and no varices, prophylaxis with nonselective β-blockers should be considered. However, this approach is controversial and more research is needed to clarify if β-blockers should be implemented as primary prophylaxis for bleeding from PHG.

Chronic Bleeding

Patients with PHG may present with iron deficiency anemia, consistent with chronic blood loss. It is important that other causes of iron deficiency anemia be excluded before assigning PHG as the cause. Iron-replacement therapy should be started in all patients with iron deficiency anemia caused by PHG; oral preparations are preferred, but intravenous (IV) iron may be used.13 The use of nonselective β-blockers seems to reduce chronic bleeding secondary to PHG. In a trial that included 14 patients with PHG who received 24 to 480 mg/day of long acting propanol49 13 patients stopped bleeding in 3 days. Propranolol was stopped in seven patients after 2 to 6 months; four of these patients rebled and stopped bleeding when propranolol was restarted. A randomized controlled trial included 54 patients with cirrhosis with acute or chronic bleeding from severe PHG; 26 patients who received propanol daily at a dose to reduce the resting heart rate by 25% or to 55 bpm (from 20–160 mg twice a day) were compared with 28 patients who received placebo.15 The percentage of patients free from rebleeding was higher in the propranolol group at 12 months (65% vs 38%) and at 30 months (52% vs 7%).

Thus, it is recommended to start iron supplementation and propranolol (up to 160 mg orally twice a day or to the maximum tolerated dose with goal heart rate (HR) of 50–55 bpm). Propanol therapy should be continued as long as the patient continues to have portal hypertension.17

Acute Bleeding

The differential diagnosis of acute GI bleeding in patients with cirrhosis includes bleeding varices (which account for approximately two-thirds of the lesions in these patients).50 Other important causes of bleeding include ulcerative processes, and mucosal lesions, such as PHG. As in all patients with acute GI bleeding, aggressive and early generalized support is essential. It should be emphasized that in the setting of portal hypertension blood transfusion should be performed with goal to maintain hemoglobin level between 7 and 8 g/dL.17 Oral or IV quinolones (eg, norfloxacin, 400 mg twice a day, or ciprofloxacin, 500 mg orally twice a day or 200 mg IV twice a day) or third-generation cephalosporin (eg, ceftriaxone, 1 g/day) for 7 days are recommended in patients with Child B or C cirrhosis or in patients who are on prophylaxis with quinolones.51 Initiation of vasoconstrictor therapy with terlipressin, somatostatin, or somatostatin analogues should be started as soon as possible and endoscopy should be performed as early as possible.

Once the diagnosis of PHG is confirmed and bleeding from varices has been ruled out, specific treatment of PHG should be started. Endoscopic treatment of acute bleeding secondary to PHG is generally not effective. In situations where a single or a limited number of lesions is apparent, endoscopic therapy (argon plasma coagulation [APC] or coagulation therapy) might be considered on an individual basis. An attempt to lower portal pressure is reasonable. The use of β-blockers has been evaluated in this setting. In one study that included 14 patients with severe PHG and acute bleeding who were treated with propranolol, bleeding was controlled within 3 days in 13 (93%) of 14 patients.49 It should be emphasized that β-blockers should be expected to take time to achieve an effective hemodynamic response; thus, in the acute period, the use of IV vasoactive drugs should be considered, even though tachyphylaxis is likely to develop.

In one study of patients with acute GI bleeding caused by PHG, octreotide (100-μg bolus followed by an infusion of 25 μg/h for 48 hours) seemed to be effective.52 In this randomized controlled trial of 68 patients with acute bleeding from PHG that compared octreotide, vasopressin, and omeprazole, octreotide controlled bleeding in 100% of patients. Of note, omeprazole and vasopressin alone controlled bleeding in 64% and 59% of patients, respectively.52 Because acid is unlikely to be a primary cause of bleeding, omeprazole probably does not play a major role in treatment of PHG, and the rate of control of bleeding with omeprazole likely mimics placebo. In another study, somatostatin led to cessation of acute bleeding from PHG in 26 patients with cirrhosis, with a rate of relapse of 11.5%.53

A double-blind randomized multicenter study of 68 patients with bleeding esophageal varices and PHG evaluated the effect of terlipressin (0.2 mg every 4 hours for 2 days or 1 mg every 4 hours for 5 days) in 68 patients.54 The study showed a higher proportion of bleeding control and lower recurrence in patients assigned to a higher dose (1 mg every 4 hours),54 but bleeding caused by PHG versus varices was not clearly differentiated.

Refractory Bleeding

Bleeding refractory to medical treatment may occur in patients with chronic or acute bleeding. In patients who present with chronic GI bleeding, those who become transfusion dependent despite iron therapy and β-blockers are general considered refractory. In patients with acute GI bleeding secondary to PHG, medical treatment failure should be considered when there is recurrent hematemesis (after 2 or more hours of treatment, such as with vasoactive medications), or a 3-g drop in hemoglobin in the absence of transfusion or an inadequate hemoglobin raise after transfusion.55 In these situations, rescue therapies, such as TIPS or shunt surgery, may be considered.55 Surgical shunts may be considered in patients with well-preserved liver function or in those with noncirrhotic portal hypertension because they have shown to improve gastric mucosal lesions and decreased the number of transfusions.56,57 TIPS also seems to be effective in stopping bleeding from severe PHG,33 having been shown to improve the endoscopic appearance of lesions within 6 to 12 weeks, and also leads to reduced transfusion requirements.32,58,59

Although APC is attractive because of its ease of application, and in those with a limited number of lesions, there are insufficient data to currently recommend it.55 In a small study that evaluated APC in 11 patients with bleeding from PHG, APC of at least 80% of the involved mucosal surface at 30 to 40 W and 1.5 to 2 L/min of AP flow every 2 to 4 weeks led to cessation of bleeding and/or a reduction in transfusion in 81% of patients. These were highly selected patients; its use should be done on an individual basis.

The most effective means of therapy is liver transplantation, but is generally most appropriate for patients with decompensated liver disease.60

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prophylaxis of bleeding in PHG should be with a β-blocker.15,55 In a double-blind placebo controlled cross-over trial that included 22 patients with non-bleeding PHG who received 160 mg of long-acting propranolol per day for 6 weeks, nine patients had improved PHG grading, whereas three had improvement after placebo (40% vs 14%); acute GI bleeding occurred in two patients taking placebo and one patient taking propranolol.49 Another study assessed the occurrence of PHG after endoscopic variceal ligation in 77 patients who were randomized to band ligation alone (40 patients) or combined with propranolol (37 patients). Patients who received propranolol had a lower occurrence of PHG than patients who had only banding.61

PORTAL HYPERTENSIVE COLOPATHY

Introduction and Definition

Portal hypertension produces changes in the colorectal mucosa, likely similar to the upper GI tract. The term PHC was initially described in 199162 in a study reporting that colonic vascular ectasias and rectal varices were endoscopic features related to portal hypertension. Endoscopic abnormalities described in patients with portal hypertension range from vascular ectasias, anorectal or colonic varices, hemorrhoids, and nonspecific inflammatory changes.62,63 PHC is likely common in patients with portal hypertension, although bleeding from this entity seems to be uncommon.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PHC in patients with cirrhosis varies from 25% to 70%.62–64 The presence of rectal or colonic varices also varies widely, being reported in from 4% to 40% of patients.64–66 Bleeding from PHC is estimated to be between 0% and 9%.65,67–69 Major differences in the reported prevalence and risk of bleeding are likely caused by patient selection, study design, lack of a clear classification system, interobserver variability among endoscopies, or differences in the indication for endoscopy.

In one study, the prevalence of esophageal varices, large esophageal varices, previous history of bleeding from esophageal varices, and rectal varices was significantly higher in patients with purported PHC than in control without colonic PHC.62 PHC has been reported to be associated with a lower platelet count,6 an increasing severity of cirrhosis (Child grade),6 large esophageal varices,70 gastric varices,64,69 higher portal pressure,70,71 and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.71 However, some studies have reported no correlation of PHC or colorectal varices with the severity of cirrhosis (Child grade),65,71,72 portal pressure,67,73 or gastroesophageal varices.65,68,69,72

Clinical Findings

PHC is usually asymptomatic; it may become manifest clinically in some patients as insidious chronic lower GI bleeding causing iron deficiency anemia. It has also been reported to cause massive or acute lower GI hemorrhage.63 In one study of 35 patients with portal hypertension who underwent colonoscopy, the reported prevalence of PHC was 77%.70 Among these patients 17% had hemoccult positive stool, and 5% presented with lower GI bleed.

Diagnostic Modalities

The diagnosis of PHC is endoscopic. In 64 patients with cirrhosis62 who underwent colonoscopy and upper endoscopy, PHC was diagnosed in the setting of flat or slightly raised reddish lesions less than 10 mm in diameter on an otherwise normal-appearing mucosa (Fig. 3). Of note, rectal varices were also examined, being defined as prominent submucosal veins, dilated proximal to the pectinate line, which protruded into the rectal lumen. These veins were different from normal rectal veins because of their greater diameter and tortuosity (measuring at least 3–6 mm in diameter). Another early study described vascular-appearing lesions in the colon that resembled gastric cherry spots and spider telangiectasias.63

Fig. 3.

Image of the colonic mucosa, depicting an area with multiple localized flat red lesions, typical of PHC. (Courtesy of A. Brock, MD, Charleston, SC.)

Classification

There is no universally accepted classification system for grading the severity of mucosal abnormalities in patients with PHC. This makes comparisons between studies challenging. Several classifications have been proposed (Table 3).5,6,62,70 Initially, a histologic criteria for the vascular lesions typical of PHC included two types of lesions.62 A so-called “early lesion” was characterized by moderately dilated, tortuous, thin-walled, and endothelial-lined veins and venules found in the submucosa. A “late-stage lesion” had progressively more dilated submucosal veins and dilated and tortuous venules and capillaries in the mucosa. Another system defined PHC endoscopically when patients had lesions appearing to be vascular ectasias, or diffuse red spots and three or more of the following: vascular irregularity, vascular dilatation, solitary red spots, and hemorrhoid.70 Vascular ectasia was classified in three types: type 1, a flat, fern-like vascular lesion (spider-like lesion); type 2, flat or slightly elevated red lesion less than 10 mm in diameter or a cherry-red lesion; and type 3, a slightly elevated submucosal tumor-like lesion with a central red color and depression. Vascular irregularity was defined as coil-like appearance of the vessels in the submucosa. Vascular dilatation was defined as numerous prominent veins of greater than 3 to 6 mm in diameter. Solitary red spots were defined as numerous red spots with or without inflammatory changes. Another study proposed that PHC should be classified in three grades: grade 1, characterized by erythema of the colonic mucosa; grade 2, erythema of the colonic mucosa with a mosaic-like pattern; and grade 3, vascular lesions in the colon including cherry-red spots, telangiectasias, or angiodysplasia-like lesions.5

Table 3.

Endoscopic classification of portal hypertensive colopathy

| Yamakado et al,70 1995 | Ito et al,6 2005 | Bini et al,5 2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of PHC | Vascular ectasia or diffuse red spots + ≥3 of the following: vascular irregularity, vascular dilatation (>3 mm vein), solitary red spots, and hemorrhoid | Vascular ectasia, redness and blue vein | Colitis-like abnormalities and/or vascular lesions |

|

| |||

| Endoscopic appearance | Type 1: flat, fern-like vascular (spider) lesion | Type 1: solitary vascular ectasia | Grade 1: erythema of colonic mucosa |

| Type 2: flat, slightly elevated red lesion of <10 mm in diameter or a cherry-red lesion | Type 2: diffuse vascular ectasia | Grade 2: erythema of the colonic mucosa with mosaic-like pattern | |

| Type 3: slightly elevated submucosal tumor-like lesion with central red color and depression | Grade 3: vascular lesions including cherry-red spots, telangiectasias or angiodysplasia-like lesions | ||

Abbreviation: PHC, portal hypertensive colopathy.

Pathology

The pathogenesis of PHC remains poorly understood. Portal hypertension seems to play an important role, and there is an association with a hyperkinetic circulatory state.70 The main pathologic change in PHC is colonic mucosal capillary ectasia.62,63 The histomorphometric analysis of colonic samples of cirrhotic patients with PHC and/or rectal varices had higher mean diameter of vessels and higher mean cross-sectional vascular area than patients with cirrhosis without PHC and/or rectal varices.62 Another study63 that included colonic biopsies of 20 patients with cirrhosis who underwent colonoscopy because of history of macroscopic or microscopic rectal bleeding, iron deficiency anemia, or colonic of polyps showed edema and capillary dilation in 50% of patients. The remaining 50% showed a slight increase in number of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria; furthermore, four patients with vascular ectasias had diffuse mucosal changes resembling chronic colitis. In a study of colon biopsies of 55 patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension and 25 control subjects,64 morphometric analysis showed that the diameter and thickness of the capillary wall was higher in patients with portal hypertension than control subjects. Other features included edema, increased mononuclear cell infiltration, and fibromuscular proliferation in the lamina propria.

In an animal model of portal hypertension,74 colonic mucosal blood flow and the number of submucosal veins were significantly increased when compared with control rats. Also, there was increased mRNA expression and enzyme activity of the inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase. It was proposed that excess nitric oxide generated by overexpressed inducible nitric oxide synthase might play a role in the vascular and hemodynamic changes seen in PHC.

Diagnostic Dilemmas

Vascular changes of PHC can sometimes be difficult to differentiate from angiodysplasia of the colon secondary to degenerative changes. The latter is usually reported in patients with chronic renal insufficiency, aortic stenosis, and older patients and these lesions are usually fewer, smaller, and less widely distributed than the lesions seen in PHC.62,72 Other noninflammatory and inflammatory etiologies of bleeding, such as ischemia, radiation changes, and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, are also in the differential diagnosis.69

For patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension who present with lower GI bleeding, PHC should be considered. Additionally, colonic varices should be differentiated from hemorrhoids, especially before surgical excision, and angiography may be considered.75

Treatment Options

The evidence with which to base treatment strategies in PHC is limited. Indeed, there is no established standard treatment of PHC. Most of the available recommendations are based on case reports or small series reports.

In an animal model comparing saline, octreotide, and propranolol, octreotide and propranolol improved typical changes in the mucosa of rats with PHC (including mucosal edema, hyperemia, and hemorrhage).76 In patients with chronic lower GI bleeding secondary to PHC, treatment with a β-blocker has been reported to be effective.77 Another study demonstrated that there was a decreased risk of bleeding from PHC in patients with portal hypertension who were taking β-blockers.5 In general, if there is evidence of iron deficiency anemia, iron replacement should be started. Treatment with β-blocker therapy as tolerated to achieve a resting heart rate of 50 to 55 bpm is reasonable.

In patients with acute bleeding, vasoactive medications, such as octreotide or terlipressin, could be effective.77 Nonselective β-blockers are recommended as soon as hemodynamic stability is achieved.77 A case report of a patient bleeding from PHC demonstrated that octreotide infusion (100-μg bolus followed by continuous infusion at 25 μg/h) decreased hepatic venous pressure gradient and stopped bleeding.77

The use of neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser photocoagulation therapy was studied in 47 patients with angiodysplasias (20 in the colon, although it was not stated whether they were idiopathic or associated with PHC).78 A median number of laser sessions (range, 1–8) were necessary to remove the angioectasias. The probability of remaining free of bleeding at 54 months was 61 ± 9%. Bleeding recurred in 15 of the 47 patients.78 These data further emphasize that angiodyplasias in PHC are usually diffuse, and even after effective therapy (such as with laser) there is a risk of recurrent bleeding from residual vascular lesions.77

TIPS has been used as a rescue therapy in patients with refractory GI bleeding that does not respond to vasoactive medications or β-blockers. In one study of persistent bleeding from PHC in a patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension that did not responded initially to propanol, bleeding was controlled after TIPS placement.79 The portosystemic gradient was reduced after TIPS placement, and repeat colonoscopy at 9 days showed decrease in size and number of colonic lesions. The patient was followed up for 18 months without recurrence of GI bleeding.79 Another report demonstrated control of lower GI bleeding from numerous angiodysplastic spots in the right colon after a proximal splenorenal shunt with splenectomy.75

Colonic varices may be treated with sclerotherapy or with shunt therapy. A study that included 20 cirrhotic patients, of which 19 were referred for colonoscopy because of iron deficiency anemia or evidence of chronic or acute lower GI bleeding, reported that two patients who had massive rectal bleeding had successful sclerotherapy of bleeding rectal varices and another two patients underwent mesocaval shunt for cecal varices.63 There are other reports suggesting the use of TIPS to control recurrent bleeding from anorectal and colonic varices.80,81 There have been reports of the use of surgical ligation,82 sclerotherapy,83 and cryosurgery for treatment of anorectal varices.84

With lower GI bleeding refractory to medical therapy, endoscopic treatment, and TIPS, surgery may be considered.85 A 24-year-old patient with portal hypertension from portal vein thrombosis and persistent hematochezia underwent a TIPS procedure and later percutaneous coil embolization of the distal inferior mesenteric vein without control of her hematochezia. Sigmoidoscopy showed edematous, friable mucosa and prominent submucosal vessels in the left colon. Because of her refractory bleeding, a laparotomy with left-sided colectomy and coloanal anastomosis led to control of bleeding.85

Prophylaxis

Trials examining the role of β-blockers or other agents for primary or secondary prophylaxis for lower GI bleeding caused by PHC have not been performed. Therefore, the best approach is unknown. In patients with concomitant esophageal varices, nonselective β-blockers are reasonable.

SUMMARY

PHG and PHC can cause acute and/or chronic GI bleeding. Their pathogenesis is still not completely understood, but currently available evidence suggests that their development is related to portal hypertension. Diagnosis for both is endoscopic. The differential diagnosis is sometimes difficult and in these situations biopsy and histologic examination may be helpful. Management of PHG and PHC centers on the clinical presentation; for acute bleeding, hemodynamic stabilization with IV fluids, IV antibiotics, and blood transfusion should be provided as needed. IV pharmacologic therapy to decrease portal pressure followed by nonselective β-blockers as soon as the patient is hemodynamically stable is appropriate. In patients with chronic bleeding, therapy with β-blockers and iron replacement is advised. Patients with refractory bleeding represent difficult clinical challenges and should be managed on an individual basis, typically with the input of specialists. TIPS and shunt procedures may be helpful in some situations. The most effective approach to reduction of portal pressure is liver transplantation, which should be considered in appropriate candidates.

KEY POINTS.

PHG and PHC can cause acute and/or chronic gastrointestinal bleeding.

Diagnosis for both is endoscopic.

The specific management of PHG and PHC depends on the clinical presentation.

For acute bleeding, hemodynamic stabilization with intravenous (IV) fluids, IV antibiotics, and blood transfusion as needed should be begun immediately. This should be followed by IV pharmacologic therapy to decrease portal pressure, and subsequently by nonselective β-blockers.

In patients with chronic bleeding, therapy with β-blockers and iron replacement is recommended. The role of TIPS is controversial.

Patients with refractory bleeding should be managed on an individual basis.

Acknowledgments

N.H. Urrunaga was supported by the NIH (Research Grant T32 DK 067872).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts: The authors certify that they have no financial arrangements (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interests, patent-licensing arrangements, research support, major honoraria, and so forth).

References

- 1.McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I, et al. Gastric lesions in portal hypertension: inflammatory gastritis or congestive gastropathy? Gut. 1985;26:1226–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.11.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thuluvath PJ, Yoo HY. Portal hypertensive gastropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2973–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menchén L, Ripoll C, Marín-Jiménez I, et al. Prevalence of portal hypertensive duodenopathy in cirrhosis: clinical and haemodynamic features. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:649–53. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200606000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higaki N, Matsui H, Imaoka H, et al. Characteristic endoscopic features of portal hypertensive enteropathy. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:327–31. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bini EJ, Lascarides CE, Micale PL, et al. Mucosal abnormalities of the colon in patients with portal hypertension: an endoscopic study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:511–6. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito K, Shiraki K, Sakai T, et al. Portal hypertensive colopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3127–30. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Amico G, Montalbano L, Traina M, et al. Natural history of congestive gastropathy in cirrhosis. The Liver Study Group of V. Cervello Hospital Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1558–64. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90458-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P, et al. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. The New Italian Endoscopic Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC) Gastroenterology. 2000;119:181–7. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, et al. The natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis and mild portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1959–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwao T, Toyonaga A, Oho K, et al. Portal-hypertensive gastropathy develops less in patients with cirrhosis and fundal varices. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1235–41. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80457-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontana RJ, Sanyal AJ, Mehta S, et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in chronic hepatitis C patients with bridging fibrosis and compensated cirrhosis: results from the HALT-C trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:983–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarin SK, Sreenivas DV, Lahoti D, et al. Factors influencing development of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:994–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cubillas R, Rockey DC. Portal hypertensive gastropathy: a review. Liver Int. 2010;30:1094–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarin SK, Shahi HM, Jain M, et al. The natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy: influence of variceal eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2888–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pérez-Ayuso RM, Piqué JM, Bosch J, et al. Propranolol in prevention of recurrent bleeding from severe portal hypertensive gastropathy in cirrhosis. Lancet. 1991;337:1431–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93125-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Franchis R, editor. Portal Hypertension II; Proceedings of the Second Baveno International Consensus Workshop on Definitions, Methodology and Therapeutic Strategies; Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ripoll C, Garcia-Tsao G. Management of gastropathy and gastric vascular ectasia in portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:281–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cales P, Pascal JP. Gastroesophageal endoscopic features in cirrhosis: comparison of intracenter and intercenter observer variability. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1189. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90652-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vigneri S, Termini R, Piraino A, et al. The stomach in liver cirrhosis. Endoscopic, morphological, and clinical correlations. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:472–8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90027-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Franchis R, Eisen GM, Laine L, et al. Esophageal capsule endoscopy for screening and surveillance of esophageal varices in patients with portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2008;47:1595–603. doi: 10.1002/hep.22227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoyama T, Oka S, Aikata H, et al. Is small-bowel capsule endoscopy effective for diagnosis of esophagogastric lesions related to portal hypertension? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jgh.12372. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Palma GD, Rega M, Masone S, et al. Mucosal abnormalities of the small bowel in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: a capsule endoscopy study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:529–34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Franchis R. Updating consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno III Consensus Workshop on definitions, methodology and therapeutic strategies in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2000;33:846–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80320-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spina GP, Arcidiacono R, Bosch J, et al. Gastric endoscopic features in portal hypertension: final report of a consensus conference, Milan, Italy, September 19, 1992. J Hepatol. 1994;21:461–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanoue K, Hashizume M, Wada H, et al. Effects of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy on portal hypertensive gastropathy: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:582–5. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70522-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo HY, Eustace JA, Verma S, et al. Accuracy and reliability of the endoscopic classification of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:675–80. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Macedo GF, Ferreira FG, Ribeiro MA, et al. Reliability in endoscopic diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:323–31. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i7.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart CA, Sanyal AJ. Grading portal gastropathy: validation of a gastropathy scoring system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1758–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishihara K, Ishida R, Saito T, et al. Computed tomography features of portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28:832–5. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200411000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erden A, Idilman R, Erden I, et al. Veins around the esophagus and the stomach: do their calibrations provide a diagnostic clue for portal hypertensive gastropathy? Clin Imaging. 2009;33:22–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohta M, Yamaguchi S, Gotoh N, et al. Pathogenesis of portal hypertensive gastropathy: a clinical and experimental review. Surgery. 2002;131:S165–70. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.119499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mezawa S, Homma H, Ohta H, et al. Effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt formation on portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric circulation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1155–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamath PS, Lacerda M, Ahlquist DA, et al. Gastric mucosal responses to intra-hepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:905–11. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta R, Sawant P, Parameshwar RV, et al. Gastric mucosal blood flow and hepatic perfusion index in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:921–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albillos A, Colombato LA, Enriquez R, et al. Sequence of morphological and hemodynamic changes of gastric microvessels in portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:2066–70. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90333-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Migoh S, Hashizume M, Tsugawa K, et al. Role of endothelin-1 in congestive gastropathy in portal hypertensive rats. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:142–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopez-Talavera JC, Merrill WW, Groszmann RJ. Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a major contributor to the hyperdynamic circulation in prehepatic portal-hypertensive rats. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:761–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payen JL, Cales P, Pienkowski P, et al. Weakness of mucosal barrier in portal hypertensive gastropathy of alcoholic cirrhosis. Effects of propranolol and enprostil. J Hepatol. 1995;23:689–96. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawanaka H, Tomikawa M, Jones MK, et al. Defective mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK2) signaling in gastric mucosa of portal hypertensive rats: potential therapeutic implications. Hepatology. 2001;34:990–9. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferraz JG, Wallace JL. Underlying mechanisms of portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(Suppl 1):S73–8. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199700001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perini RF, Camara PR, Ferraz JG. Pathogenesis of portal hypertensive gastropathy: translating basic research into clinical practice. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:150–8. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gostout CJ, Viggiano TR, Ahlquist DA, et al. The clinical and endoscopic spectrum of the watermelon stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:256–63. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199210000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ripoll C, Garcia-Tsao G. The management of portal hypertensive gastropathy and gastric antral vascular ectasia. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Payen JL, Calès P, Voigt JJ, et al. Severe portal hypertensive gastropathy and antral vascular ectasia are distinct entities in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:138–44. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent C, Pomier-Layrargues G, Dagenais M, et al. Cure of gastric antral vascular ectasia by liver transplantation despite persistent portal hypertension: a clue for pathogenesis. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:717–20. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tobin AB, Budd DC. The anti-apoptotic response of the Gq/11-coupled muscarinic receptor family. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1182–5. doi: 10.1042/bst0311182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ingraham KM, O’Brien MS, Shenin M, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in systemic sclerosis: demographics and disease predictors. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:603–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spahr L, Villeneuve JP, Dufresne MP, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: absence of relation with portal hypertension. Gut. 1999;44:739–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.5.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hosking SW, Kennedy HJ, Seddon I, et al. The role of propranolol in congestive gastropathy of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1987;7:437–41. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lyles T, Elliott A, Rockey DC. A risk scoring system to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with cirrhosis presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013 doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000014. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernández J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gómez C, et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1049–56. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.010. quiz: 1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Y, Qiao L, Wu J, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of octreotide, vasopressin, and omeprazole in the control of acute bleeding in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy: a controlled study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:973–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kouroumalis EA, Koutroubakis IE, Manousos ON. Somatostatin for acute severe bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:509–12. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199806000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruha R, Marecek Z, Spicak J, et al. Double-blind randomized, comparative multicenter study of the effect of terlipressin in the treatment of acute esophageal variceal and/or hypertensive gastropathy bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Franchis R, Faculty BV. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soin AS, Acharya SK, Mathur M, et al. Portal hypertensive gastropathy in noncirrhotic patients. The effect of lienorenal shunts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:64–7. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199801000-00017. discussion: 68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Orloff SL, et al. Treatment of bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy by portacaval shunt. Hepatology. 1995;21:1011–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Urata J, Yamashita Y, Tsuchigame T, et al. The effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1061–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vignali C, Bargellini I, Grosso M, et al. TIPS with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent: results of an Italian multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:472–80. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeWeert TM, Gostout CJ, Wiesner RH. Congestive gastropathy and other upper endoscopic findings in 81 consecutive patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, et al. The effects of endoscopic variceal ligation and propranolol on portal hypertensive gastropathy: a prospective, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:579–84. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.114062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Naveau S, Bedossa P, Poynard T, et al. Portal hypertensive colopathy. A new entity. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1774–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01296624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kozarek RA, Botoman VA, Bredfeldt JE, et al. Portal colopathy: prospective study of colonoscopy in patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1192–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90067-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V. Prevalence and factors influencing hemorrhoids, anorectal varices, and colopathy in patients with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 1996;28:340–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bresci G, Parisi G, Capria A. Clinical relevance of colonic lesions in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 2006;38:830–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rabinovitz M, Schade RR, Dindzans VJ, et al. Colonic disease in cirrhosis. An endoscopic evaluation in 412 patients. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:195–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen LS, Lin HC, Lee FY, et al. Portal hypertensive colopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:490–4. doi: 10.3109/00365529609006770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ganguly S, Sarin SK, Bhatia V, et al. The prevalence and spectrum of colonic lesions in patients with cirrhotic and noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology. 1995;21:1226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Misra V, Misra SP, Dwivedi M, et al. Colonic mucosa in patients with portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:302–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamakado S, Kanazawa H, Kobayashi M. Portal hypertensive colopathy: endoscopic findings and the relation to portal pressure. Intern Med. 1995;34:153–7. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Diaz-Sanchez A, Nuñez-Martinez O, Gonzalez-Asanza C, et al. Portal hypertensive colopathy is associated with portal hypertension severity in cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4781–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Misra V, et al. Colonic changes in patients with cirrhosis and in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Endoscopy. 2005;37:454–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang TF, Lee FY, Tsai YT, et al. Relationship of portal pressure, anorectal varices and hemorrhoids in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 1992;15:170–3. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90031-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohta M, Kaviani A, Tarnawski AS, et al. Portal hypertension triggers local activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene in colonic mucosa. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:229–35. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(97)80114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leone N, Debernardi-Venon W, Marzano A, et al. Portal hypertensive colopathy and hemorrhoids in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2000;33:1026–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aydede H, Sakarya A, Erhan Y, et al. Effects of octreotide and propranolol on colonic mucosa in rats with portal hypertensive colopathy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1352–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoshie K, Fujita Y, Moriya A, et al. Octreotide for severe acute bleeding from portal hypertensive colopathy: a case report. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1111–3. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200109000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Naveau S, Aubert A, Poynard T, et al. Long-term results of treatment of vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract by neodymium YAG laser photocoagulation. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:821–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01536794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Balzer C, Lotterer E, Kleber G, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for bleeding angiodysplasia-like lesions in portal-hypertensive colopathy. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:167–72. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katz JA, Rubin RA, Cope C, et al. Recurrent bleeding from anorectal varices: successful treatment with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1104–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fantin AC, Zala G, Risti B, et al. Bleeding anorectal varices: successful treatment with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) Gut. 1996;38:932–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.6.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johansen K, Bardin J, Orloff MJ. Massive bleeding from hemorrhoidal varices in portal hypertension. JAMA. 1980;244:2084–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Richon J, Berclaz R, Schneider PA, et al. Sclerotherapy of rectal varices. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3:132–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01645319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mashiah A. Massive bleeding from hemorrhoidal varices in portal hypertension. JAMA. 1981;246:2323–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ozgediz D, Devine P, Garcia-Aguilar J, et al. Refractory lower gastrointestinal bleeding from portal hypertensive colopathy. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:613. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]