Abstract

Understanding the transmission dynamics of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections is critically dependent on accurate behavioral data. This paper investigates the effect of questionnaire delivery mode on the quality of sexual behavior reporting in a survey conducted in Kampala in 2010 among 18–24 year old females using the women’s instrument of the 2006 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. We compare the reported prevalence of five sexual outcomes across three interview modes: traditional face-to-face interview (FTFI) in which question rewording was permitted, FTFI administered via computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in which questions were read as written, and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI). We then assess the validity of the data by evaluating reporting of sexual experience against three biological markers. Results suggest that ACASI elicits higher reporting of some key indicators than face-to-face interviews, but self-reports from all interview methods were subject to validity concerns when compared with biomarker data. The paper highlights the important role biomarkers play in sexual behavior research.

Introduction

Understanding the transmission dynamics of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) at the population level, and evaluating programmatic interventions designed to contain their spread, are critically dependent on accurate sexual behavioral data. Given that sexual activity cannot directly be observed, research must rely on self-reports, which are subject to problems of recall, question misinterpretation, social desirability bias, and normative reporting. Recent studies have found little association between self-reported risky behavior and infection, with several methodological reviews of survey data from developing countries directly questioning the validity and reliability of sexual behavior reporting (Cleland et al. 2004, Curtis and Sutherland 2004, Langhaug et al. 2010, Plummer et al. 2004). Indeed, notable oddities in behavioral data – including STIs among women claiming to be virgins (Buvé et al. 2001, Glynn et al. 2001, Cowan et al. 2002), lower than expected HIV incidence among men reporting multiple non-marital partners (Nnko et al. 2004), and discrepancies between information reported during individual interviews and that obtained from medical examination (Rassjö et al. 2011) – suggest that under- or over-reporting of sexual activity distort assessments of HIV risk.

Reporting biases may be reduced or exacerbated depending on the mode of questionnaire delivery. Much of the survey data from developing countries – most notably the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) – are collected using traditional face-to-face interviewing (FTFI). While this method has logistical and efficiency advantages over other approaches, reporting via FTFI may be compromised by interviewers’ inaccurate re-wording of questions, directive probes, non-verbal cues, and inappropriate feedback (Fowler and Mangione 1990). Researchers leading studies in Kenya and Malawi that found high levels of consistent reporting of sexual behaviors in FTFI compared to audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) speculated that, despite instructions to the contrary, interviewers sometimes skipped questions to which they assumed they already knew the answers, or reconciled discrepant responses on their own (Mensch et al. 2008a). Another study (Turner et al. 2009) found that participants in a clinical trial acknowledged deliberately misleading interviewers in FTFI out of politeness to researchers, or because they feared criticism or embarrassment.

Increasing attention has been paid to technology-based interview methods, including ACASI, as potential alternatives to FTFI (Phillips et al. 2010). A primary advantage of ACASI over other interview techniques is the private nature of data collection, and thus the potential to reduce social desirability bias in the reporting of sensitive or stigmatized behaviors. With ACASI, the participant listens to questions through headphones and enters responses using a touch screen or answer keypad. This technique affords a greater standardization of questionnaire administration by providing an identical script to each respondent, and therefore has been considered to largely eliminate interviewer effects. ACASI has been shown to be feasible to implement in a number of low development settings and to elicit higher reports of some sensitive behaviors relative to other interview modes – e.g. in Kenya (Hewett et al. 2004), Malawi (Mensch et al. 2008a), Zimbabwe (Langhaug et al. 2011), India (Potdar and Koenig 2005), and Vietnam (Le et al. 2006) – although results vary by setting and sample. A recent systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries found that, overall, ACASI produced higher reporting of sensitive behaviors than did FTFI (Langhaug et al. 2010), while a second review and meta-analysis of quantitative interviewing tools in low- and middle-income countries concluded that results depended on the sensitivity of the outcome and the population under study (Phillips et al. 2010).

In cases where levels or types of reporting statistically differ between interview modes, it is typically assumed, at least for females, that higher reporting of sexual activity and other risk behaviors is inherently more accurate, due to the stigma associated with acknowledging such activities (Hewett et al. 2008). To formally assess the truthfulness of reporting in different interview modes, it is informative to include an external validation measure against which to compare self-reported behavior. STI biomarkers can provide such an objective standard, although relatively few studies have combined randomized interview mode experimentation with STI outcomes as indicators of risky behavior (Langhaug et al. 2010, Phillips et al. 2010, Siegfried and Mathews 2010). Exceptions include an experiment among women in São Paulo, Brazil (Hewett et al. 2008), which evaluated sexual behavior reporting in ACASI and FTFI against STI biomarkers and found both that reporting of STI risk behavior was significantly higher in the computerized interview, and that associations between risk behavior and STI infection were stronger in ACASI relative to FTFI. In South Africa, Mensch and colleagues (2011) also observed an ACASI “advantage” over FTFI in a placebo gel microbicide study that tested participants for recent semen exposure. By contrast, Minnis et al. (2009) found in Zimbabwe that self-reported sexual activity and condom use were equally problematic in FTFI and ACASI when validated against an objective biomarker of recent unprotected sex.

This paper builds on existing literature by combining a randomized interview mode experiment with three different biological outcomes. Unlike most previous experiments, it also explicitly examines the role of interviewer effects in FTFI by comparing two interview delivery styles.

Methods

Study design and sample

The study was conducted among women aged 18–24 years in Kampala, Uganda. Using the sampling frame from the 2002 census, 40 enumeration areas in Kampala were selected using simple random sampling. Within each sampled enumeration area, 30 households were selected, also using simple random sampling. All women aged 18-24 who were either permanent residents of selected households or visitors to the household the night preceding the interview were eligible to participate in the study. Study participants were randomized to one of three interview modes:

Group 1: FTFI using conventional paper and pencil; question rewording permitted

Group 2: FTFI using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI)1; questions read as written

Group 3: Traditional FTFI for non-sensitive questions and ACASI for sensitive ones.

The questionnaire used was a subset of questions from the women’s instrument of the 2006 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey (UDHS). The survey covered a number of sensitive topics, including sexual initiation, recent sexual activity, transactional or forced sex, condom use, and HIV/AIDS awareness. As is standard practice in the DHS (ICF Macro 2011), in Group 1 interviewers were permitted, when necessary, to reword questions to improve respondents’ understanding.2

For Group 2 (CAPI – questions read as written), interviewers were trained only to read questions off the computer screen verbatim, regardless of participant’s comprehension. The response option “Respondent does not understand question” was added to each question, and treated as missing in analyses. For Group 3 (ACASI), non-sensitive questions were administered via paper-and-pencil FTFI, following the same protocol as Group 1. Participants listened to sensitive questions through headphones connected to a handheld computer and recorded their answers by pressing colored buttons on the screen. In all interview modes, questionnaires were offered in either English or Luganda.

Using block randomization, respondents were assigned to one of the three interview modes, and also randomized to an interviewer to control for the potential impact of interviewer characteristics. Interviewers were selected from a cadre of trained personnel with previous experience administering the UDHS. Because of interviewers’ familiarity with DHS protocol, Group 1 and Group 3 interviews were undertaken first, following which interviewers were retrained to administer Group 2 interviews. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Upon completion of the survey and administration of additional informed consent procedures, a blood sample was obtained via finger prick for HIV and Herpes Simplex Virus-type 2 (HSV-2) testing. HIV testing was conducted at the household consistent with the Uganda National Ministry of Health Guidelines (Uganda Ministry of Health 2003). Specimens for the HIV test were evaluated with Determine™. Positive samples were then retested using Uni-Gold™ Recombigen®. Both Determine™ and Uni-Gold™ Recombigen® have a sensitivity of nearly 100% and a specificity >99%. A third rapid test, Clearview® HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK (99.7% sensitivity, 99.9% specificity), served as a tie-breaker in the event of discordant results. After completion of HIV testing, respondents were provided with their results, post-test counseling and, if applicable, referrals for follow-up testing and care.

HSV-2 testing was conducted at the Molecular Research Laboratory (MOLAB) of the Makerere University-University of California San Francisco Research Collaboration in Kampala, using dried blood spots (DBS) collected at the household. DBS were used in preference to whole blood due to the difficulties associated with storing and transporting whole blood to the lab. HSV-2 tests were based on the Kalon ELISA antibody test on DBS. However, of the initial 277 samples tested using the Kalon assay with a 1:4 dilution, only 5 tested positive, a prevalence well below expectations based on prior sero-prevalence surveys. Thus it was concluded that validation of dried blood spots for the Kalon HSV-2 test, which theretofore had not been conducted, needed to be undertaken. The validation, conducted at MOLAB, tested dilutions of 1:2, 1:3 and 1:4 on 220 stored serum-tested positive and negative specimens from the 2004–2005 Uganda HIV/AIDS Sero-Behavioural Survey, and found that the 1:2 ratio of buffer and eluate produced the best results with DBS. However, the sensitivity and specificity of the test were relatively low: 85% and 74%, respectively (Marandet et al. 2013). The HSV-2 results reported here should therefore be interpreted with caution, although any misclassifications should be independent of interview mode.

In addition to providing a blood sample, participants were asked to perform a self-administered vaginal swab for a Rapid Stain Identification of Human Semen (RSID™-Semen) test, a third study biomarker. The RSID test indicates whether a woman has engaged in unprotected sex during the previous 48 hours, with a sensitivity to detect the presence of as little as 1 μl of semenogelin, a major component of seminal fluid (Mauck, 2009). RSID specimens were self-swabbed by respondents at the household, placed in a dry tube, and transported to MOLAB for testing. Women were told that the RSID test identified the presence of semenogelin in vaginal fluids, but not that their sexual activity reporting would be compared with the test result.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Population Council Institutional Review Board, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the Makerere University Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee.

Analysis

Combining interview and biomarker data, the analysis will primarily focus on two evaluations of the reporting of sexual behavior:

A comparison of the reporting between Groups 1 (FTFI) and 2 (CAPI) to examine the effects of interviewer assistance and question rewording on reporting.

A comparison of the reporting between Groups 2 (CAPI) and 3 (ACASI) to assess whether the strict reading of questions in the CAPI mode reproduces the standardization of the ACASI interview, albeit retaining potential other interviewer effects on reporting.

For completeness’ sake, we will also compare Groups 1 and 3, which is the interview mode comparison that has been conducted in prior experimental research (e.g. Mensch et al. 2003, Mensch et al. 2008a).

Statistical analysis was conducted in Stata version 12.1 (College Station, TX). Using pairwise z tests, we begin by comparing the proportions of respondents interviewed via FTFI, CAPI and ACASI who report five key sexual outcomes: ever had vaginal sexual intercourse, ever forced to have sex, transactional sex in the past 12 months, more than one lifetime sexual partner, and unprotected sex in the past two days. We determine that a woman has had sex if she provided an age at first intercourse. We also include 11 women in the CAPI group who responded “Don’t know” to the age at first sex question but reported sexual activity elsewhere in the survey. Respondents were considered to have experienced forced sex if they reported any of the following: forced sexual debut, forced sex with current or most recent husband/partner, forced sex with a non-marital partner in the past 12 months, or forced sex with any person at any other time. Women who reported having transactional sex answered affirmatively to the question: “In the past 12 months, did you ever give or receive money, gifts or favours in exchange for sex?”. Respondents were also asked how many different people they had had sexual intercourse with in their lifetime. We identify those with more than one lifetime sexual partner, excluding those who answered “Don’t know” unless elsewhere in the survey they reported having more than one partner in the past year or having been married more than once. The indicator of unprotected sex in the past two days combines reporting of 1) sexual activity on the day of interview, the previous day, and two days prior, and 2) condom use on each day of reported sex.

We examine the association between interview mode and reporting of the five selected outcomes in a stepwise fashion, comparing odds ratios from unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models. In the multivariate models, we control both for characteristics of questionnaire delivery and selected socio-demographic variables. Specifically included are the language of questionnaire (English or Luganda) relative to the language of interview (in Groups 1 and 2 interviewers could conduct the interview in a language other than that used for the questionnaire)3, and whether the interview was conducted in the respondent’s native language. We thereby aim to control both for potential question misinterpretation by respondents as well as possible mistranslation by interviewers. We also control for age, highest level of schooling attended, marital status, religion, asset ownership, paid work in past 12 months, and current contraceptive use.

Introducing the biological data, we then validate the reporting of sexual activity and condom use. We firstly calculate the number of respondents in each interview mode who did not report ever having sex and yet tested positive for HIV or HSV-2. For the RSID test, we examine reporting of unprotected sex in the past two days. Because of rapid clearance of semenogelin from vaginal fluid after exposure, and thus the likelihood that the positive RSID tests underestimate true prevalence of recent unprotected sex, we follow Minnis et al. (2009) by restricting our analysis of discrepant data only to those respondents who test positive for RSID. The analysis concludes with an examination of item non-response in each of the three interview modes, particularly that deriving from question incomprehension in the CAPI group.

Results

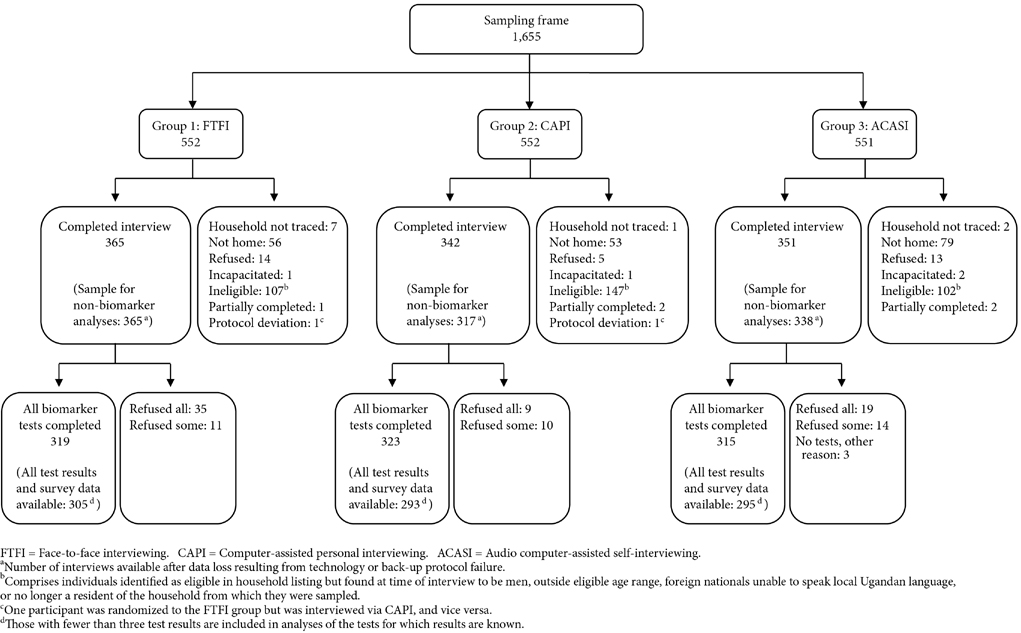

Figure 1 shows the number of completed interviews in each questionnaire delivery mode. Overall, 81.6% of eligible women (1,058/1,297) were successfully interviewed.4 The completion rate in the CAPI group (342/404=84.7%) was significantly higher than that in ACASI (351/449=78.2%, p=0.016). There was no difference between the CAPI and FTFI (365/444=82.2%) arms, nor between FTFI and ACASI. Thirty-two women refused to participate in the study, with a slightly lower proportion (1.2%) of eligible women in the CAPI group declining relative to the other two interview modes (3.2% in FTFI, p=0.060; and 2.9% in ACASI, p=0.093). An additional 7.3% and 3.7% of the electronic data collected via CAPI and ACASI, respectively, were unrecovered due to technology or backup protocol failure. The analytic sample therefore comprises 365 women in Group 1, 317 in Group 2, and 338 in Group 3.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of number of women aged 18–24, randomized to three interview modes, who participated in the survey and the biomarker tests, Kampala, Uganda, 2010

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of each interview group. Mean age in each was 21 years5, with approximately half of respondents being currently married. Education levels were very similar across arms: just over 50% had attended secondary school, and a further fifth reached tertiary education or university. Contraceptive use was fairly uniform across groups at approximately 40%; slightly more women reported using a non-hormonal method in CAPI than in FTFI or ACASI. The distribution of religious affiliations and engagement in paid work in the past year also differed significantly across interview modes. All covariates listed in Table 1 were included in multivariate models, except where indicated.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of women interviewed via FTFI, CAPI, and ACASI

| Group 1 FTFI – question rewording (N=365) | Group 2 CAPI – questions read as written (N=317) | Group 3 ACASI (N=338) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire characteristics | a | b | c |

|

| |||

| Language of questionnaire/interview | |||

| Matched - Luganda | 74.4 | 77.6 * | 68.9 |

| Matched - English | 11.4 | 15.5 *** | 31.1 *** |

| Unmatchedd | 14.2 ** | 6.9 *** | 0.0 *** |

| Native language of respondent | |||

| Interview in native language | 60.0 * | 68.8 | 62.6 |

| Interview in non-native language | 40.0 | 31.2 | 37.4 |

|

| |||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Age (mean) | 21.1 | 21.1 | 21.2 |

| Highest level of schooling attended (%) | |||

| No school | 1.9 | 3.2 | 1.8 |

| Primary | 28.8 | 28.8 | 26.1 |

| Secondary | 52.0 | 50.3 | 53.7 |

| Tertiary/university | 17.3 | 17.7 | 18.4 |

| Marital status (%) | |||

| Never married | 41.4 | 41.9 | 35.8 |

| Currently married | 52.1 | 51.4 | 54.7 |

| Previously married | 6.6 | 6.7 | 9.5 |

| Religion (%) | |||

| Catholic | 33.4 | 31.3 | 36.2 |

| Protestant | 28.2 * | 21.1 | 22.8 |

| Muslim | 18.6 | 23.3 | 26.1 * |

| Pentecostal | 14.3 | 18.9 * | 13.1 |

| Other | 5.5 | 5.4 * | 1.8 ** |

| Number of assets owned (mean) e | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 |

| Paid work in past 12 months (%) f | 41.9 * | 50.8 * | 41.5 |

| Current contraceptive use (%) | |||

| None | 66.0 | 59.9 | 62.9 |

| Hormonal method g | 20.9 | 20.4 | 23.4 |

| Non-hormonal method h | 13.1 * | 19.7 * | 13.8 |

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Difference in means/proportions between Group 1 and Group 2

Difference in means/proportions between Group 2 and Group 3

Difference in means/proportions between Group 3 and Group 1

The vast majority of FTFI interviews were conducted in Luganda or in English. One participant in the Group 1 completed the interview in Runyankole-Rukiga and another in a different, unspecified language. For the portion of the Group 3 (ACASI) survey concerned with sexual behavior reporting, the language of interview was, by definition, the same as that of the questionnaire.

Range 0–8. Participants were asked if their household had: electricity, radio, television, mobile phone, refrigerator, table, sofa set, or DVD/CD player.

Includes women who reported being paid in cash, or both in cash and in kind, for work performed during the past 12 months. Excludes 18 women in the CAPI group who did not understand questions related to labor force participation.

Includes pill, injectable, implant

Includes IUD, condom, lactational amenorrhea, rhythm, withdrawal, other method not already mentioned

NOTES: Ns may be smaller than reported due to missing values. With the exception of marital status, all socio-demographic characteristics determined via face-to-face interview in Group 3.

Table 2 compares the reported prevalence of the sexual experience measures across interview modes and indicates that for four of the five outcomes reporting was higher in ACASI than in either of the other two modes, although differences were not universally significant. 92.0% of respondents reported ever having sex in ACASI vs. 86.0% in CAPI (p=0.015) and 87.9% in FTFI (p=0.076). Prevalence of forced sex was also highest in ACASI (39.2% vs. 34.3% in CAPI and 30.6% in FTFI) and was significantly different from FTFI (p=0.017). Note that respondents were given the opportunity to report an episode of forced sex even if they had not provided an age at sexual debut; 17 women (1 in FTFI, 8 in CAPI, 8 in ACASI) did so. However, the questionnaire skip pattern restricted subsequent questions related to sexual activity only to those who had reported an age at first sex. Among these women, a higher percentage acknowledged more than one lifetime sexual partner in ACASI than did respondents in FTFI or CAPI, but the differences were not significant. Approximately one-fifth (19.4%) of sexually active women reported engaging in transactional sex in ACASI, relative to 12.0% in FTFI (p=0.011) and 16.4% in CAPI. Although similar proportions of women in each of the three interview modes reported having had sex in the previous two days, reporting of condom use was significantly higher in ACASI compared with FTFI and CAPI (p<0.001 in each case). Given the presumed social desirability associated with condom use in a country with high HIV prevalence, the opposite pattern of responses was expected.

Table 2.

Reporting of sexual outcomes in each interview mode (%)

| Group 1 FTFI – question rewording (N=365) | Group 2 CAPI – questions read as written (N=317)a | Group 3 ACASI (N=338)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever had sex c | 87.9 | 86.0 * | 92.0 |

| Forced sex d | 30.6 | 34.3 | 39.2 * |

| If ever sex e: | (N=321) | (N=271) | (N=310) |

| >1 lifetime sexual partner f | 66.9 | 67.8 | 71.5 |

| Transactional sex past 12 months | 12.0 | 16.4 | 19.4 * |

| Sex in past two days g | 25.8 | 26.7 | 29.7 |

| Condom use in past two days (if sex in past two days)h | 4.9 | 8.7 *** | 30.4 *** |

| Unprotected sex in past two days | 24.5 | 24.4 | 20.7 |

p<0.001;

p<0.01;

p<0.05;

p<0.1

Difference in means/proportions between Group 2 and Group 3

Difference in means/proportions between Group 3 and Group 1

We determine that a woman has had sex if she provided an age at first intercourse. Also included are the 11 women in the CAPI group who responded “Don’t know” to the age at first sex question but reported sexual activity elsewhere in the survey.

Respondents were considered to have experienced forced sex if they reported any of the following: forced sexual debut, forced sex with current/most recent husband/partner, forced sex with a non-marital partner in the past 12 months, forced sex with any person at any other time.

Sexually active women were determined by the age at first sex question, according to the questionnaire skip instructions. Ns for subsequent sexual behavior questions may be lower than reported due to missing values.

Participants were asked how many different people they had had sexual intercourse with in their lifetime. Those who reported more than one lifetime sexual partner are included here. We exclude those who answered “Don’t know”, unless elsewhere in the survey they reported having more than one partner in the past year or having been married more than once.

Includes women who reported having sex on one or more of: the day of the interview, the day before the interview, and two days before the interview.

For each day that women reported having sex, they were asked if they used a condom for every sex act on that day. We include only women who reporting using a condom on every day that they reported having sex.

Table 3 shows the odds ratios from unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models predicting reporting of each outcome of interest. The crude logistic regression results, which use CAPI as the reference category, largely parallel the findings of Table 2. Because only one married woman (in the ACASI arm) reported never having sex, we restrict analysis of the ever had sex indicator to never-married women and find that, relative to CAPI, respondents in ACASI were more likely to report having premarital sex (OR: 1.73, p=0.066). The same is observed in the adjusted model, which controls for interview and participant characteristics (AOR: 1.95, p=0.057).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models predicting reporting of sexual outcomes in Group 1 (FTFI - question rewording) and Group 3 (ACASI), relative to Group 2 (CAPI – questions read as written)

| Group 1 FTFI - question rewording | Group 3 ACASI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Ever had sex (N=385)b | 1.16 | 0.69–1.96 | 1.16 | 0.63–2.12 | 1.73 | 0.96–3.09 | 1.95c | 0.98–3.88d |

| Forced sex (N=949) | 0.88 | 0.63–1.23 | 0.87 | 0.61–1.26 | 1.31 | 0.94–1.83 | 1.26 | 0.88–1.82 |

| Multiple lifetime partners (N=829) | 1.01 | 0.70–1.45 | 1.05 | 0.71–1.55 | 1.22 | 0.84–1.77 | 1.38 | 0.91–2.08 |

| Transactional sex in past year (N=837) | 0.68 | 0.41–1.11 | 0.63 | 0.36–1.08 | 1.27 | 0.97–2.61 | 1.59 | 0.97–2.61e |

| Sex in past two days (N=844) | 0.97 | 0.66–1.43 | 1.20 | 0.76–1.90 | 1.22 | 0.83–1.78 | 1.42 | 0.91–2.20 |

| Unprotected sex, if sex in past two days (N=232) | 1.59 | 0.41–6.21 | 2.02 | 0.41–10.0 | 0.19 ** | 0.07–0.54 | 0.11 *** | 0.03–0.35 |

p<0.01

p<0.001

Adjusted models control for the characteristics listed in Table 1, with the exception of ever had sex, which excludes marital status and current contraceptive use. Dummy variables for interviewer ID were also included; 2 observations were dropped from the ever had sex model for predicting failure perfectly. For notes about how outcome and explanatory variables were constructed, consult Tables 1 and 2.

Restricted to never married women

p=0.066

p=0.057

p=0.068

Including both ever- and never-married participants, ACASI respondents were more likely to report forced sex, multiple lifetime partners, and transactional sex relative to those in CAPI, although none of the differences were statistically significant in unadjusted models. Controlling for covariates, the result for transactional sex achieved marginal statistical significance (AOR: 1.59, p=0.068). Reporting of recent sexual activity was similar across all three interview modes, but women in ACASI were significantly less likely to report that it was unprotected relative to both FTFI and CAPI (p<0.001).

ACASI reporting yielded significantly greater responses than did FTFI regarding the questions concerning forced sex (OR: 1.49, p=0.014; AOR: 1.42, p=0.052) and transactional sex (OR: 1.87, p=0.007; AOR: 2.49, p<0.001); data not shown. We did not observe any significant differences in reporting between the CAPI and FTFI groups in either the crude or adjusted regression models.

Validation with biomarkers

Figure 1 shows the number of women in each group who completed the biomarker tests. Women in the CAPI arm were less likely to refuse one or more biomarker tests than were women in the FTFI (5.6% vs. 12.6%, p=0.001) or ACASI (5.6% vs. 9.4%, p=0.054) groups. Among those who consented to the biomarker component, 4.4%, 2.5%, and 2.2% of results are incomplete in Groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively, due to insufficient or spoiled samples, failure to safely return specimen from the field, or data entry error. A comparison of the socio-demographic characteristics of women for whom one or more biomarker results are missing – because of refusals or for other reasons – shows that these women do not differ from their counterparts with complete biomarker data (not shown). Similarly, among women who undertook biomarker testing but for whom corresponding survey data are missing, the prevalence of positive HIV, HSV-2, and RSID tests does not statistically differ from the prevalence in the analytic sample.

Table 4 presents the number of women, among those for whom survey and biomarker data were available, who reported recent sexual activity and condom use, according to interview mode and the results from two of the three biomarker tests. Among the women for whom survey and biomarker data are available, 7.3% tested positive for HIV (9.1% in the FTFI group, 7.3% in CAPI, and 5.4% in ACASI; not shown). The difference between FTFI and ACASI was marginally significant (p=0.079). Because all participants who tested positive for HIV also reported sexual initiation, we do not present these results in Table 4.

Table 4.

Biomarker validation using HSV-2 and RSID testing of reports of sexual activity and condom use, by interview modea

| Group 1 FTFI – question rewording | Group 2 CAPI – questions read as written | Group 3 ACASI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HSV-2 + | HSV-2 − | HSV-2 + | HSV-2 − | HSV-2 + | HSV-2 − | |

| Never had sex (N) b | 8 | 32 | 7 | 29 | 7 | 10 |

| Ever had sex (N) | 136 | 148 | 149 | 118 | 135 | 159 |

| % who report never having had sex among those who test positive (95% CI) | 8/144 = 5.6% (1.8% – 9.3%) | 7/156 = 4.5% (1.2% – 7.8%) | 7/142 = 4.9% (1.3% – 8.5%) | |||

|

| ||||||

| RSID + | RSID − | RSID + | RSID − | RSID + | RSID − | |

|

| ||||||

| Never had sex (N)b | 2 | 33 | 5 | 30 | 0 | 16 |

| No sex in past 2 days (N) | 35 | 167 | 42 | 143 | 38 | 153 |

| Protected sex only in past 2 days (N) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 14 |

| Unprotected sex in past 2 days (N) | 40 | 29 | 40 | 23 | 25 | 31 |

| % who report no unprotected sex in past 2 days among those who test positive (95% CI) | 38/78 = 48.7% (37.6% – 59.8%) | 49/89 = 55.1% (44.7% – 65.3%) | 51/76 = 67.1%c (56.5 – 77.7%) | |||

HIV results omitted from table due to absence of discrepant reporters

Never had sex defined as reporting of neither an age at first sex nor an episode of forced sex

Significantly different from Group 1 (p=0.021)

The top panel of Table 4 enables us to calculate that 47.1% of women screened positive for HSV-2 antibodies, with prevalence varying slightly between interview mode groups (44.4% FTFI, 51.5% CAPI, and 45.5% ACASI; marginally significant difference between CAPI and FTFI, p=0.078). Unlike for HIV, the HSV-2 test results provide some evidence of discrepant reporting. Among those who tested positive, 5.6% reported never having had sex in the FTFI group, 4.5% did so in CAPI, and 4.9% in ACASI.

It is possible that some of the apparent discrepant reporting stems from result misclassification, given the specificity of the test. According to the Kalon validation with DBS, the positive predictive value – or the probability that a participant who tested positive is actually positive – is 0.75 (95% CI: 0.69–0.81). Hence, the probability of each self-reported virgin who tested positive being positive is 0.75 with the associated confidence interval. This will affect the magnitude of the estimates, but since the distribution of false positives should be independent of interview mode, it should not influence the comparisons.

Table 4 also breaks down RSID test results according to reporting of recent sex and condom use. Among women who tested RSID positive, 38 (48.7%) did not report having unprotected sex in the previous two days in FTFI, and 49 (55.1%) did not do so in CAPI. Fifty-one women, or 67.1% of those with a positive RSID result, did not report unprotected sex in the past two days in ACASI, a proportion that is significantly higher than in the FTFI group. Interestingly, while the vast majority of discrepant reports in the FTFI and CAPI groups stemmed from women not reporting any sex in the past two days, one-fifth of women in ACASI who tested positive for RSID reported using condoms during all recent sex acts.6

Given that reporting of condom use was unexpectedly higher in ACASI, we investigated whether women in ACASI who reported use of condoms during sex in the previous two days differed from their counterparts who did not report condom use. No statistically significant differences were observed among the characteristics listed in Table 1 (results not shown). We also explored whether higher reporting of condom use in ACASI could reflect riskier sexual partnerships, but did not find significant associations between protected sex and reporting of forced sex, transactional sex, or multiple partners (not shown). Note, though, that the power to detect statistical differences was somewhat limited by small sample size. We also examined whether respondents in ACASI consistently reported higher condom use by comparing responses to two additional indicators in the survey: proportions of women reporting using a condom the first time they had sexual intercourse were almost identical across interview modes (54.5% in ACASI vs. 54.6% in CAPI and FTFI). Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the reporting of condom use at last sex (27.2% in ACASI, 22.1% in CAPI, 20.3% in FTFI).

Item non-response

Finally, we briefly examine the extent to which the socio-demographic characteristics and sexual activity indicators displayed in Tables 1 and 2 were affected by item non-response. In the FTFI and ACASI interviews, respondents were given the option to decline to answer a particular question, or to answer “Don’t know”. In the CAPI group, interviewers had the additional opportunity to indicate that participants did not understand the question, by using a designated response option. For questions regarding socio-demographic characteristics,7 no participants in any interview mode did not know the answer or declined to respond, but question incomprehension was noted in the CAPI interview. While questions regarding schooling and childbirth, for example, were minimally affected, 26 women – or 8.2% of participants with non-missing data – did not understand at least one of the series of five questions related to labor force participation.8 Among the sexual behavior questions, reporting of transactional sex was most affected by question incomprehension: 9 women – or 3.3% of the subset of sexually active women – did not understand the question. In addition, CAPI participants were significantly more likely than FTFI respondents to answer “Don’t know” to questions related to age at first sex (3.2% vs. 0%, p<0.001) or to the number of lifetime sexual partners (4.1% vs. 1.3%, p=0.031).

Discussion

We investigated whether the reported prevalence of five sexual outcomes differed by interview mode, and then assessed the validity of self-reported data against three biological outcomes. Considered alongside the biomarker data, our results indicate that self-reported sexual behavior data are problematic irrespective of questionnaire delivery mode. Although no self-reported virgins tested positive for HIV, approximately 5% of women who screened positive for HSV-2 denied sexual debut, while between 48.7% and 67.1% of women who tested positive for RSID reported never engaging in unprotected sex in the past two days. These figures are consistent with findings from previous studies that have identified discrepant reporting using biomarkers (Gallo et al. 2013)9. Although the self-reported data from all three delivery modes raise concerns, we did observe differences between the groups with respect to reporting of sensitive behaviors, data validity, and item non-response.

The first featured comparison, between variants of the face-to-face interview (paper and pencil – question rewording and CAPI – questions read as written), did not reveal any significant differences in either the reported prevalence of sexual activity or in the magnitude of discrepant data when validated against biomarker results. This suggests that interviewer delivery had neither a strongly positive nor a strongly negative impact on the reporting of our outcomes of interest. It is important to note, however, that since the interviewers had previous experience administering the UDHS, in which question rewording is permitted, they may have found adhering to the Group 2 protocol difficult. Deviations from protocol may then explain the absence of differences in reporting between the two FTFI groups. Nevertheless, we did see above that item non-response to questions related both to socio-demographic characteristics and to sexual behavior was higher in CAPI relative to FTFI, stemming partly from question incomprehension. Although the magnitude of non-response in Group 2 was generally very low, it seems likely that Group 1 interviewers played some role in clarifying queries and resolving inconsistencies. Alternatively, participants with more “active” interviewers may have felt pressured to provide responses even if they did not understand the question or know the correct response (Mensch et al. 2008b).

The second featured comparison explored whether ACASI elicited higher reporting of sensitive behavior than did FTFI administered using a standardized script from which interviewers were instructed not to deviate. Results show that reporting of four key measures—sexual initiation, forced sex, multiple lifetime partners, and transactional sex—was greater in ACASI than in CAPI, but the differences were not statistically significant for the second and third of these measures and only marginally significant for the first and fourth. Compared with biological data, however, reporting in ACASI was equally or more inconsistent then in the other groups. The inflated reporting of condom use in ACASI is particularly puzzling given the presumed social desirability associated with using condoms.

There are several possible explanations for the discrepant data which do not necessarily imply deliberate misreporting. Firstly, since more women in the ACASI arm reported forced or transactional sex, higher condom use among this group could reflect these riskier partnerships. However, we found no association between the reporting of recent condom use and risky sexual behavior. Alternatively, the survey instrument did not include questions on condom slippage or breakage, which may have caused some respondents who reported having protected sex nevertheless to be exposed to semenogelin. We would, though, expect condom failures to be randomly distributed across the three questionnaire delivery modes.

Finally, although the wording and sequence of condom use questions was the same in ACASI as in the other two modes, and reporting of condom use was not associated with low education or literacy levels which might signal question incomprehension, it is possible that some participants misunderstood what was being asked, especially since reporting of condom use elsewhere in the survey did not differ across modes. A calendar question such as this, which involved respondents first answering a series of questions about sexual activity on each of the previous five days, and then a set of associated questions asking about condom use on those particular days, may not be suited to self-administered interview modes. More generally, although the proportion of respondents answering “Don’t know” or declining to answer questions in ACASI was low, it is conceivable, given the experience in the standardized CAPI interview, that in some cases participants may have registered responses to questions they did not understand. A key advantage of the automated, self-administered nature of ACASI is that it eliminates interview effects, but such a design removes the opportunity for interviewers to probe respondents or clarify questions, which may consequently restrict the level of complexity of data that can be collected (Luke et al. 2011).

On the other hand, higher reporting of some of the sexual behavior indicators in ACASI relative to the other two modes could reflect a greater ease with the privacy afforded by the computerized interview. In a South African clinical trial, Turner and colleagues (2009) found that female participants overwhelmingly preferred being interviewed via ACASI relative to FTFI (46% vs. 8%; 45% expressed no preference). The majority of women also felt that the computerized interview was equally (33%) or more (61%) private than the FTFI (7%). Beauclair et al. (2013) similarly found that ACASI was preferred to FTFI among urban South African respondents, but identified certain participants – those who were unemployed or aged 40–70 years old – who were less likely to find the method easy to use. Overall, the effectiveness of ACASI has been shown to vary by study visit, population, setting, and research objective (Gallo et al., 2013), so in contexts for which evidence is limited about the utility of a particular interview mode, acceptability pilot studies would be advised.

In view of the problems associated with self-reported data, biomarkers can play an important role in sexual behavior research, by providing alternate, and presumably more accurate, measures of STI risk and validating self-reported behavioral data (Mauck 2009). Of course, incorporating biomarker testing into research studies increases the cost and logistical challenge of data collection. Kalon ELISA test kits are fairly inexpensive at US$3 per test (Ng’ayo et el. 2010), while RSID-Semen kits approach US$8 per test (Independent Forensics).10 However, both necessitate additional expenditure on sample collection, storage, and transport, as well as laboratory analysis. It may also be difficult in field-based research to secure the level of privacy required for sample collection, or to obtain the consent of participants unfamiliar with the procedures involved (Gallo et al. 2013), although these factors did not appear to have a large impact in our study. Finally, STI biomarkers may be of limited utility as a means of validating self-reports if prevalence is low, as demonstrated by the HIV results featured here.

In studies where it is not feasible to include biological data, and for outcomes that cannot be adequately measured by biomarker tests, such as coital frequency and exposure to anal sex, researchers must continue to rely on self-reports. Investigators should therefore continue to develop and evaluate innovative ways to collect self-reported data which encourage accurate reporting and to supplement such methods with biomarker tests.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant, R01-HD047764, from the Eunice K. Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors thank Wilson Nyegenye and Helen Nviri of the Uganda Bureau of Statistics for their support in data collection and management, and Sister Mollay of Kiswa Health Centre for providing counseling to study participants. We also thank Wolfgang Hladik of Centers for Disease Control Uganda and Erica Soler-Hampejsek of the Population Council for their technical guidance. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding institution.

Footnotes

CAPI interviewers used handheld computers to read questions and enter participants’ answers, eliminating the need for paper questionnaires and data entry.

The following instructions were included in the interviewers’ training manual for paper-and-pencil FTFI: “If the respondent has not understood the question, you should repeat the question slowly and clearly. If there is still a problem, you may reword the question, being careful not to alter the meaning of the original question.”

The Uganda DHS is translated into seven major languages, which increases the likelihood that a survey is available in a respondent’s first language (Uganda Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro 2012).

The completion rate excludes ineligible women and protocol deviations from the denominator. A considerable proportion of women who were identified as eligible in the household listing were found at the time of interview not to meet one or more of the eligibility criteria. The majority were outside the specified age range, while others turned out either to be male, or foreign nationals unable to speak either English or a local Ugandan language. Women who had permanently moved from the households in which they were listed were also excluded and not followed up for participation.

Each respondent was asked both for her month and year of birth and for her current age. When age data are missing or unknown, we impute the mean age of the respective interview mode group. In cases where month/year of birth and current age are inconsistent, we use the birth date information to assign an age. This strategy results in the exclusion of 20 participants (2 in FTFI, 12 in CAPI, and 6 in ACASI) who fall outside the eligible age range. Omitting these women does not change the nature of our findings.

Preliminary laboratory analyses suggest that the RSID test may successfully detect traces of semenogelin more than 48 hours after an episode of unprotected sex (Professor Betsy Herold, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, personal communication, 13 July 2012). Extending the window of sexual activity reporting to five days prior to interview, 33.3% of women who tested positive for RSID did not report engaging in unprotected sex in the FTFI group, 41.6% did not do so in the CAPI group, and 55.3% did not in ACASI. As in Table 4, the proportion of women reporting discrepantly was significantly higher in ACASI relative to FTFI (p=0.006), and was also marginally significantly different from CAPI (p=0.079).

With the exception of marital status, all socio-demographic questions were asked to Group 3 participants via FTFI, following the protocol of Group 1.

12 women did not understand one of four questions related to whether or not she had worked in the past 12 months and the remaining 14 did not understand a question about whether the work was paid.

Note that it is possible, had participants been told before completing the interview that their responses would be compared against biological specimens, that they may have improved their accuracy, but a recent study did not find a significant difference in the reporting of unprotected sex between participants randomized to know and not to know about subsequent biomarker validation (Thomsen et al. 2007).

Other semen-detecting assays are also available for ~US$4.50 – ~US$20 (Gallo et al., 2013)

References

- Beauclair Roxanne, Meng Fei, Deprez Nele, et al. Evaluating audio computer assisted self-interviews in urban south African communities: evidence for good suitability and reduced social desirability bias of a cross-sectional survey on sexual behavior. [Accessed 9 December 2013];BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013 13(11) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-11. < http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/13/11>. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvé A, Lagarde E, Caraël M, et al. for the Study Group on Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Interpreting sexual behaviour data: validity issues in the multicentre study on factors determining the differential spread of HIV in four African cities. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S117–S126. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Boerma JT, Caraël M, Weir SS. Monitoring sexual behaviour in general populations: a synthesis of lessons of the past decade. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl II):ii1–ii7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan Frances M, Langhaug Lisa F, Mashungupa George P, et al. School based HIV prevention in Zimbabwe: feasibility and accepability of evaluation trials using biological outcomes. AIDS. 2002;16(12):1673–1678. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200208160-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis SL, Sutherland EG. Measuring sexual behaviour in the era of HIV/AIDS: the experience of Demographic and Health Surveys and similar enquiries. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl II):ii22–ii27. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler Floyd J, Mangione Thomas. Standardized Survey Interviewing: Minimizing Interviewer-Related Error. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo Maria F, Steiner Markus J, Hobbs Marcia M, Warner Lee, Jamieson Denise J, Macaluso Maurizio. Biological markers of sexual activity: Tools for improving measurement in HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention research. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2013;40(6):447–452. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828b2f77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn JR, Caraël M, Auvert B, et al. for the Study Group on Heterogeneity of HIV Epidemics in African Cities. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S51–S60. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett PC, Mensch BS, Erulkar AS. Consistency in the reporting of sexual behaviour by adolescent girls in Kenya: a comparison of interviewing methods. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl II):ii43–ii48. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett Paul C, Mensch Barbara S, Manoel Carlos S, de Ribeiro A, et al. Using sexually transmitted infection biomarkers to validate reporting of sexual behavior within a randomized, experimental evaluation of interviewing methods. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(2):202–211. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICF Macro. MEASURE DHS Basic Documentation No. 2. Calverton, Maryland, U.S.A: ICF Macro; 2011. Demographic and Health Survey Interviewer’s Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Forensics. Independent Forensics Order Sheet. Lombard, IL: Independent Forensics; 2013. [Accessed 9 December 2013]. < http://www.ifi-test.com/ShortUSOrderForm.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Langhaug Lisa F, Cheung Yin Bun, Pascoe Sophie JS, et al. How you ask really matters: randomised comparison of four sexual behaviour questionnaire delivery modes in Zimbabwean youth. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87(2):165–173. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhaug Lisa F, Sherr Lorraine, Cowan Frances M. How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2010;15(3):362–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Linh Cu, Blum Robert W, Magnani Robert, Hewett Paul C, Do Hoa Mai. A pilot of audio computer-assisted self-interview for youth reproductive health research in Vietnam. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(6):740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Nancy, Clark Shelley, Zulu Eliya M. The relationship history calendar: improving the scope and quality of data on youth sexual behavior. Demography. 2011;48(3):1151–1176. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marandet Angele, Nsobya Sam, Mensch Barbara S, et al. Examining the performance of the Kalon Herpes Simplex Virus 2 assay using dried blood spots in a Ugandan population. 2013 doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v5i1.429. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck Christine K. Biomarkers of semen exposure. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36(3 Suppl):S81–S83. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318199413b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S, Hewett Paul C, Abbott Sharon, et al. Assessing the reporting of adherence and sexual activity in a simulated microbicide trial in South Africa: an interview mode experiment using a placebo gel. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(2):407–421. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9791-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S, Hewett Paul C, Erulkar Annabel S. The reporting of sensitive behavior by adolescents: a methodological experiment in Kenya. Demography. 2003;40(2):247–268. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S, Hewett Paul C, Gregory Richard, Helleringer Stephane. Sexual behavior and STI/HIV status among adolescents in rural Malawi: an evaluation of the effect of interview mode on reporting. Studies in Family Planning. 2008a;39(4):321–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch Barbara S, Hewett Paul C, Jones Heidi E, et al. Consistency in women’s reports of sensitive behavior in an interview mode experiment, Sao Paulo, Brazil. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2008b;34(4):169–176. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.34.169.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnis Alexandra M, Steiner Markus J, Gallo Maria F, et al. Biomarker validation of reports of recent sexual activity: results of a randomized controlled study in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170(7):918–924. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng’ayo Musa Otieno, Friedrich David, Holmes King K, Bukusi Elizabeth, Morrow Rhoda Ashley. Performance of HSV-2 Type Specific Serological Tests in Men in Kenya. Journal of Virological Methods. 2010;163(2):276–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnko Soori, Ties Boerma J, Urassa Mark, Mwaluko Gabriel, Zaba Basia. Secretive females or swaggering males?: An assessment of the quality of sexual partnership reporting in rural Tanzania. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;59(2):299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Anna E, Gomez Gabriella B, Boily Marie-Claude, Garnett Geoffrey P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative interviewing tools to investigate self-reported HIV and STI associated behaviours in low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(6):1541–1555. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer ML, Ross DA, Wright D, et al. “A bit more truthful”: the validity of adolescent sexual behaviour data collected in rural northern Tanzania using five methods. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Suppl II):ii49–ii56. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potdar Rukmini, Koenig Michael A. Does Audio-CASI improve reports of risky behavior? Evidence from a randomized field trial among young urban men in India. Studies in Family Planning. 2005;36(2):107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassjö EB, Mirembe F, Darj Elisabeth. Self-reported sexual behaviour among adolescent girls in Uganda: reliability of data debated. African Health Sciences. 2011;11(3):383–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried Nandi, Mathews Catherine. Commentary: All is not what it seems: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative interviewing tools to investigate self-reported HIV and STI-associated behaviours in low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(6):1556–1557. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen Sarah C, Gallo Maria F, Ombidi Wilkister, et al. Randomised controlled trial on whether advance knowledge of prostate-specific antigen testing improves participant reporting of unprotected sex. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(5):419–420. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.022772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner Abigail Norris, De Kock Alana E, Meehan-Ritter Amy, et al. Many vaginal microbicide trial participants acknowledged they had misreported sensitive sexual behavior in face-to-face interviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(7):759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF International Inc. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS; Calverton, Maryland: ICF International Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda National Policy Guidelines for HIV Counselling and Testing. Kampala: Ministry of Health; 2003. [Google Scholar]