Abstract

Many developing regions are facing a youth bulge, meaning that young people comprise the highest proportion of the population. These regions are at risk of losing what could be a tremendous opportunity for economic growth and development if they do not capitalize on this young and economically productive population - also referred to as the “demographic dividend,” defined as the increase in economic growth that tends to follow increases in the ratio of the working-age population - essentially the labor force - to dependents. Nations undergoing this population transition have the opportunity to capitalize on the demographic dividend if the right social, economic, and human capital policies are in place. In particular, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa are at risk of losing the demographic dividend. These regions face high youth unemployment, low primary school completion, and low secondary school enrollment. This results in an undereducated and unskilled segment of the population. The prohibitive costs of education prevent young people from finishing school, thereby entering the labor market unprepared. This article presents a case for youth-focused financial inclusion programs as one of the antidotes to the masses of poor, undereducated, and low-skilled young people swelling the labor markets of poor developing countries.

Keywords: demographic dividend, child savings accounts, contractual savings for education, sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa

Introduction

Will the world's poorest and least stable states be able to profit from the ‘demographic dividend’ that helped today's advanced industrialized nations grow? Are there ways to synergize public and private interests to increase the possibility that these countries will be able to help lift themselves out of poverty? Or will they instead be plagued by the “demographic curse” of mass youth unemployment? Demographic dividend refers to the increase in economic growth that tends to follow increases in the ratio of the working-age population - essentially the labor force - to dependents. In other words, as the proportion of working-age members of a national population increases, economic growth has often followed. Reduced fertility and mortality rates, increased participation by women in the labor market, and the reversal of outward migration trends among the working-age population have been cited as factors enhancing demographic dividends throughout the 1990s and 2000s (Bloom, Canning, & Sevilla, 2003). Yet, despite having young and growing populations, many of the world's poorest developing countries are in a precarious position when it comes to the possibility of optimizing the benefits of demographic dividends. In sub-Saharan Africa for instance, continued high fertility and youth dependency rates make economic growth even more difficult (Bloom & Sachs, 1998).

While many factors are necessary to optimize a country's potential benefit from a demographic dividend, this article also argues that education, particularly when linked to financial inclusion - that is, making financial products and services accessible and affordable for disadvantaged, low-income populations - can help optimize the demographic dividends from the “youth bulge.” Harnessing innovations in finance for education appears essential to this task. Specifically, this article suggests that contractual savings (savings accounts held at formal financial institutions designed for children and youth, with educational incentives and withdrawal stipulations) and insurance for financing education are key areas of opportunity for both private and public sector actors seeking to foster economic growth in emerging markets. Scholars of demographic dividends emphasize the role of education policy as a major determinant of developing countries’ ability to maximize the benefits of the demographic dividend. The role of education in maximizing the benefits of the demographic dividend in two of the world's youngest regions - sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East and North Africa - is particularly pressing. Yet, developing countries face serious challenges to financing education, especially when they have large and growing young populations. It is crucial to assess how these countries can optimize the benefits of the observed demographic trends. How can they increase the labor productivity of their growing youth populations rather than having a larger group of un-employed or under-employed youth who may otherwise increase the dependence burden to these economies?

This article argues that there is a socially crucial and economically exciting opportunity to harness innovations in education financing to increase funding for education in developing countries, particularly those with large, young populations. Innovative partnerships across the public and private sector divides are budding in a variety of settings throughout the developing world. Because both private sector financial institutions as well as citizens of developing countries themselves stand to gain from economic growth in emerging markets, this strategy builds on synergistic interests to maximize shared benefits from demographic dividends. Yet, the possibilities for such partnerships are understudied and not without pitfalls. This article aims to advance our thinking about such opportunities and to elucidate these possibilities and pitfalls.

In the second section, relevant demographic trends are discussed. Focusing on sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa, I consider the possible synergy between private and public sector institutions, particularly in the realm of education finance. Here, I draw on existing studies on contractual savings and insurance products, as well as selected interviews with program implementers familiar with the topic of contractual savings and insurance products for education. The third section considers examples of extant programs that reflect these opportunities, as well as available evidence concerning their success. The fourth section synthesizes reported findings and discusses the policy implications of this work.

Demographic transitions in developing countries

Most regions in the world are experiencing a demographic transition. Less developed countries have a larger proportion of youth and have higher fertility rates than advanced industrialized countries. They also tend to have much younger populations. Yet, life expectancy in many developing countries remains extremely low. Rates of dependents must be reduced for these countries to maximize the benefits of a demographic dividend.

First, let me set the rapidly changing global demographic changes in context. Today, Asia accounts for 60 percent of the global population. During the second part of the 21st century, however, demographers expect Asia's share of the world population to drop below 50 percent. Africa, which overtook Europe as the second most populous region in the world in 1996, is projected to experience even more rapid population growth, from 863 million in 2010 to 1.8 million in 2050 (Eastwood & Lipton, 2011; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013). By 2050, Africa is expected to account for 24 percent of the world population - up from its current 15 percent; and in 2100, it may account for 35 percent (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013). These are startling trends and underscore the rapidly changing nature of the global population.

Moreover, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is not only the world's least developed region, but, with approximately 200 million people between ages 12 and 24 living in Africa (representing 28% of the continent's population), it is also the world's youngest region (see Figure 1) (Garcia & Fares, 2008; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013).

Figure 1.

Youth population sub-groups from 1950 to 2050 (estimates and projections).

Falling second behind SSA, populations in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are also growing rapidly. The region's population of approximately 430 million is projected to surpass 700 million by 2050 (see Figure 1) (Roudi-Fahimi & Kent, 2007; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2013). The youth bulge in MENA is also clear. In this region, one out of every three people is between ages 10 and 24, and at least 40 percent of the population is under age 15.

As Africa and the Middle East experience their largest youth cohorts in history, increased social exclusion, rising unemployment rates, and precarious education systems create enormous costs to national governments. Early school dropout and youth unemployment mean losses in potential labor productivity and human capital accumulation. This perpetuates a cyclical deprivation of opportunity and an increasing number of dependents (Chaaban, 2008). For example, at nearly 30 percent unemployment in the Middle East and 24 percent unemployment in North Africa, these regions have among the highest youth unemployment rates in the world by a wide margin (currently, youth unemployment in Italy, Spain and Portugal is also around 25%) (ILO, 2013; Jaramillo & Melonio, 2011). As a result, young educated workers are increasingly moving to the informal sector to cope with the scarcity of formal sector employment. This arguably undermines the region's potential to optimize benefits associated with demographic dividends and increases the chances that they will have to pay high costs associated with mass youth unemployment. While youth unemployment rates in sub-Saharan Africa are below average at just above 11 percent relative to the rest of the world, the region faces the lowest education enrollment and completion rates in the world, thereby producing an unskilled and uneducated labor force (ILO, 2013).

What are the economic implications of these demographic trends? A country's age structure is linked to its economic performance. Transition from a high fertility and mortality equilibrium to one characterized by low fertility and low mortality may impact economic growth in part by increasing the size and, as we will discuss below, the skill level of the working-age population, and also by decreasing the relative proportion of economic dependents (Bloom, Canning, Fink, & Finlay, 2007). Economic dependents typically include small children and older people, and in some societies women who are not permitted or encouraged to engage in wage labor. Countries with swollen youth populations that do not take steps to develop and capitalize on these demographic transitions often suffer and may remain underdeveloped for a longer time. For example, citizens in countries with a large proportion of children will likely devote a higher proportion of their resources to these children, rather than investing in productive enterprises or secondary and tertiary education. Over time, this can have negative effects on the entire economy. Hence, scholars have focused on the role of education policy as a determinant of countries’ ability to reap demographic dividends. The next section considers the specific ways in which education relates to this potential and considers related opportunities for fruitful partnerships.

The role of education: youth-focused, asset-based development

Education can optimize the demographic dividend. Specifically, education can bring more workers into formal employment. This can increase productivity as well as the nation's tax base, which may help increase overall employment and growth. At the macrolevel, education improves a country's competiveness. An educated labor force could potentially afford a country to attract more competitive production phases with higher value added. On the individual level (microlevel), education can help reduce unemployment and underemployment. It can also improve skills and knowledge so workers can use more advanced technologies. This may lead to improved efficiency in the market and hence more sustainable growth. The development of a more skilled labor force may also lower the unit cost for skilled workers and attract greater levels of foreign direct investment and higher wages for the employed.

Current challenges to increasing access to education in SSA and MENA

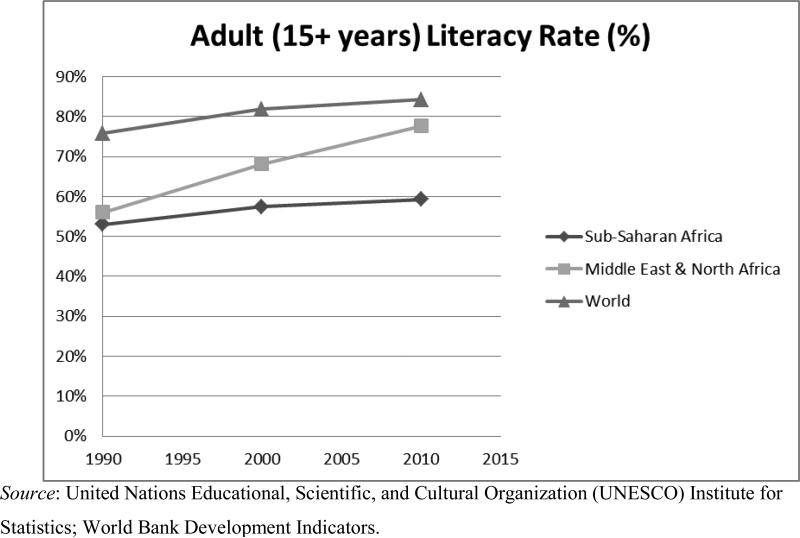

Most national governments in MENA and SSA do not prioritize funding education to the extent that they should. This increases their risk of losing out on the optimal benefits of dividends for their economies. Even in regions where governments have made efforts to universalize primary education, primary school completion rates are still very low. In MENA, 13.5 percent of the population aged 15 years and older completed primary school in 2010, as did 24.3 percent in sub-Saharan Africa (Barro & Lee, 2013). However, figures available for the same year indicate that 32.2 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa versus 23.8 percent in MENA had no schooling in 2010 (Barro & Lee, 2013). Approximately 95 million young women and men in SSA without formal education are unemployed, in low-paying jobs, or totally withdrawn from the labor force (Garcia & Fares, 2008). If labor is the most abundant asset of poor households in Africa, ensuring educational development of youth is essential to helping families move out of poverty. In Uganda, for example, men who completed primary education earned 30 percent more, and those who completed secondary education earned 140 percent more than those who did not complete primary. For women, the earnings ratios are even higher, at 49 and 150 percent, respectively (Vilhuber, 2006). Indeed, as indicated in Figures 2 and 3 below, regions with low literacy rates, also report low income per capita.

Figure 2.

GDP per capita (US$).

Figure 3.

Adult (15+ years) Literacy Rate (%).

One of the key reasons that youth in sub-Saharan Africa often leave school early and enter the labor market unprepared is immediate financial constraints. This increases their vulnerability to intergenerational poverty and economic instability (Garcia & Fares, 2008; Oosterbeek & Patrinos, 2008). Youth who leave school early or never attend formal schooling systems rarely earn wages and often work in the informal sector – probably not maximizing their potential productivity had they completed school. In rural areas in particular, most youth are involved in un- or underpaid family work. Youth in urban areas also endure challenges. They often face long periods of un- or under-employment, leading many to engage in risky and volatile informal market sectors to earn money.

Against this backdrop, education emerges as an important channel to increase the ability of SSA and MENA to enjoy demographic dividends, rather than the curse of youth bulges. Although states are often constrained in their ability – and sometimes willingness – to allot adequate public resources towards the education sector, there is room for innovative public –private hybrids to pave the way, encouraging the emergence of promising markets that offer potential economic growth for households, financial institutions, and governments, alike.

In the section below, I discuss the potential role of asset development strategies, including individual-level contractual savings pegged to education, in improving access to education and educational performance.

The asset-effect

Knowing that governments are not in a position and/or are not prepared to shoulder the entire burden of funding education, the key question is: Given the benefits of education, coupled with the financial constraints families face, what can these young countries do to improve chances for their youth to attain education, which might eventually help the young economies to optimize the demographic dividend? And, more pointedly, what programs and policies are needed to open educational opportunities for youth who are part of these financially constrained families?

Consider the fact that the decisions youth make between the ages of 12 and 24 have disproportionate effects on their long-run potential to acquire human capital (Ssewamala, Han & Neilands, 2009; Ssewamala, Karimli, Han, & Ismayilova, 2010a). This has enormous consequences for the future. In Assets for the Poor (1991), Michael Sherraden theorized that holding even minor financial and/or material assets impacts people's behavior, attitudes, and hopes for the future. These, in turn, impact an individual's development of human capital. Moreover, in providing a foundation against risk, assets allow people to specialize and focus, and may also have important psycho-social benefits such as increased household stability and generally improved psycho-social functioning.

Although Sherraden's work began with a focus on the urban American poor, it has proven widely relevant for development practitioners working in a variety of settings including settings in developing African countries. Sherraden, Ssewamala and colleagues are currently involved in several tests of asset-development programs in the region (see YouthSave consortium, 2010, Center for Social Development, various publications; Ssewamala, 2005; Ssewamala, Alicea, Bannon, & Ismayilova, 2008; Ssewamala, Han, Neilands, Ismayilova, & Sperber, 2010b; Ssewamala, Han, & Neilands, 2009; Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2009). The explanation for the wide-ranging applicability of asset-theory is due in part to the fact that Sherraden (1991) articulated a position shared by many in the field of international social development when he observed that the existing social welfare (and development) policies, while “humane and justifiable, [are] not …necessarily the best way to structure welfare assistance” (p. 4). Rather, according to Sherraden, there should be “another approach that would fundamentally promote the well being of the poor and the long-term growth of [any given] nation” (1991, p. 4). Precisely, Sherraden and colleagues have shown that the poor can – and do – save and invest in their own future if provided with opportunities to develop basic financial literacy, access to institutions and low-cost financial products, and capital. To date, several studies have demonstrated specific benefits associated with participation in asset-building development interventions –defined as efforts that enable people with limited financial and economic resources or opportunities to acquire and accumulate long-term productive assets. The benefits range from improved health and psycho-social functioning, community development and child protection, and improved educational outcomes, including increased access to educational opportunities (Elliot, 2009; Huang, Guo, Kim, & Sherraden 2010; Curley, Ssewamala & Han, 2010; Ssewamala, Han & Neilands, 2009; Ssewamala, et al., 2010a; Ssewamala, Ismayilova, McKay, et al., 2010d). For example, Elliot (2009) examined 1,065 youth aged 12 to 18 years in U.S. public school through a nationally representative data base, 2002 Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), and found that children with a Child Development Account (CDA) were nearly twice as likely to expect to attend college than children without a CDA. Huang, et al. (2010) utilized the same dataset (PSID) and examined 650 young adults aged 18 to 21 and found that both income and assets had a consistent long-term association with children's college entry. Moreover, using the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Kim and Sherraden (2011) examined 632 U.S. high school students and found that financial assets and home-ownership were significantly associated with high school completion and college attendance - with the association being mediated by children's educational expectations. Curley, Ssewamala and Han (2010) evaluated an economic empowerment intervention (including a youth savings account [YSA] for education component) for 274 orphans in primary schools in rural Uganda and found that children with YSAs not only saved for their education but also had more positive changes in their future educational plans and a higher level of confidence in their plans when compared with the control group that did not receive the YSAs.

Given the above findings, the question is what could be the pathways through which assets (in this case savings) improve youth educational outcomes? A plausible explanation is that savings raise children's and/or parental educational expectations, raised expectations may lead to increased children's academic efforts and/or parental involvement, leading in turn to improved educational outcomes (Elliot, Kim, Jung, & Zhan, 2010; Ssewamala, Alicea, Bannon, & Ismayilova, 2008; Zhan, 2006). Overall empirical studies indicate that assets have a positive association with educational outcomes (Elliot, et al., 2010; Grinstein-Weiss, Yeo, Irish, & Zhan, 2009; Loke & Sacco, 2011).

The need for innovative methods to finance education and optimize the demographic dividends

Most countries in SSA will not be able to substantially expand secondary education unless they increase the share of expenditure allocated to secondary school. Specifically, public expenditure for education would have to be 25 and 30 percent of what would go towards secondary schooling. One option is to provide needs-based subsidies and waivers to those who cannot pay secondary school fees; merit-based scholarships are also sometimes used to encourage promising, low-income students to remain in school. Low-interest loans to finance the cost of schooling are also a possibility. However, this would involve a high-risk commitment from the financial sector and, without a ready market to absorb their skilled labor, could be a risky investment for students, as well (Lewin, 2008).

Clearly, evidence (some of which is detailed above; see also Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2009; YouthSave Consortium, 2010) demonstrates potential links between family assets, youth-owned savings accounts, and improved educational outcomes and skill acquisition. This growing body of evidence also demonstrates a positive relationship between increased access to formal financial institutions, youth savings accounts and insurance products, and positive youth development. Promoting savings among low-income youth may contribute to financial inclusion by introducing more people to the formal financial system. Further, “banking the unbanked” in this way may promote youth savings by increasing young people's knowledge of and experience with financial services. While increased youth and household savings products and deposit services are proving effective in facilitating poor and vulnerable youth to help finance their education, a major impediment remains: The vast majority (72%) of people in developing countries do not have access to formal financial services (Kendall, Mylenko, & Ponce, 2010). The main reasons for this include lack of proximity, the high costs of access to such services, and the organizational cultures of formal institutions whose procedures and staff attitudes often deter poor, financially excluded people (Making Cents International, 2009).

Further, many poor people do not use formal financial services because of doubts about the security of such institutions (Hulme, Moore, & Barrientos, 2009). Improving coverage and proximity, making financial savings services less costly, strengthening the security of savings services (both in real terms and in terms of public perceptions), and making formal institutions more user-friendly to poor people are among the ways in which formal financial institutions can attract poor and vulnerable clients. Young clients who wish to invest in their own schooling and adult clients who wish to invest in the education of their offspring typify this type of client. Hence, it is possible that voluntary educational savings accounts are valuable to financial institutions because they help select for more committed and responsible clients, prima fascia.

Overall, a consequence of most poor households in the poorest regions of the world not having access to formal financial services (see Figure 4) is that those without access to a bank account must rely on informal financial services, which may be more costly and unreliable as they are often insecure. At the family and individual level, the “unbanked” do not have options to manage their cash flows or to smooth consumption. At the macrolevel, such vast disparities in financial inclusion present obstacles to economic development, which is particularly relevant for low-income developing economies.

Figure 4.

Percentage of banked households across the world having a deposit account in a formal financial institution in 2009.

In SSA and MENA specifically, poor people's access to institutionalized financial mechanisms is very limited. Only 35 percent of the population in the Middle East and North Africa and 12 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa are considered to be financially included (CGAP & The World Bank Group, 2010). As a result, young people accumulate savings through informal channels. As indicated in Figure 4, although globally the percentage of banked households varies greatly across countries and regions, SSA is the region with the lowest share of banked households.

The potential role of savings products and insurance in financing education for youth in developing countries

Efforts in reducing the existing disparity in financial inclusion for the SSA region are increasing and include contractual savings products currently offered in developing economies. These products are intended to facilitate the mobilization of youth savings through such products like youth savings accounts (YSAs) or child development accounts (CDAs). From the perspective of financial institutions (FIs), compared with other forms of microsavings, such as involuntary deposits or demand/voluntary deposits, contractual savings provide long-term funds, typically have larger balances, are more profitable despite their higher interest, and require low administrative intensity (Hulme, Moore, & Barrientos, 2009). From the perspective of clients, contractual savings have the potential to fulfill expected needs or opportunities and encourage discipline, and they have a higher interest. Contractual savings for education necessitates financial products designed specifically for school-age youth and their parents/guardians (Meyer, Masa, & Zimmerman, 2010; also see Appendix A.

How does insurance for education compare with contractual savings for education? The key difference is that insurance for education is subject to insurance agent discretion. Agents make the ultimate decision about the validity of a claim or application, unlike savings which can be sanctioned by the saver (Hulme, et al., 2009). The other difference is that youth tend to be more interested in short-term returns rather than wait for longer-term returns promised and/or provided by most insurance companies. Youth tend to want to see their “returns” in a relatively shorter period, say 3 to 5 years, than waiting for 10 to 15 years. With that in mind, insurance companies need to devise short-term products that would be attractive to youth in purchasing insurance for education (personal communication with Michael J. McCord, December 19, 2011, and with Stephen Muiga, December 22, 2012).

The various contractual savings and education insurance products differ primarily in terms of their rules about who may save and invest and how the products are utilized. The most basic type of savings account offered to youth is simply a savings account open to all children of minor age status, often referred to as a youth savings account (YSA). Financial institutions often offer products geared specifically for different youth age cohorts, such as accounts for young children, adolescents, and young adults. Youth are able to transfer funds from one account to the next over time. This feature helps facilitate saving through life stages, enabling youth to accumulate savings over time. Additionally, it has the potential to foster a long-term client base for financial institutions, thereby strengthening the possibility for increases in their net profit over time.

Related specifically to savings linked to education, some banks in developing countries operate deposit centers directly in schools or school-based bank branches, which makes banking easily accessible for students, and has the potential to cultivate and grow the bank's clientele. In addition, the process has the potential to instill habitual saving at an early age. This allows banks to gain consumer loyalty in the long run.

A notable feature of youth savings accounts includes withdrawal frequency restrictions. These restrictions are in place for two reasons. First, limiting the number of withdrawals youth account-holders make can decrease administrative costs for the financial institution. Second, reducing withdrawals can encourage the accumulation of total savings amounts, encouraging the client to build long-term assets. Equity Bank in Kenya, for example, allows only one withdrawal per quarter and Barclays Bank in Ghana allows one withdrawal per month. Through Mexico's Youth with Opportunities program, in which the Mexican government opens savings accounts for children of poor families when the children are in the equivalent of middle school, the youth account-holders are restricted from making withdrawals until they graduate from high school. In Mongolia, Khan Bank and Zoos Bank restrict withdrawals of their respective youth savings products until age 18. Additionally, many purveyors of youth savings accounts often require child consent in order for the parents to withdraw from the account, as is common practice in Bolivia, among other places.

Other ways in which to limit withdrawal activity include using incentives and disincentives. Barclays Bank in Uganda gives youth account holders double interest if they refrain from withdrawing in a quarter (Meyer et al., 2008).1 Equity Bank offers free banker's checks to pay school fees directly debited from the YSA (Meyer et al., 2008). Both Fundisa in South Africa and Suubi-Uganda in Uganda, partner with financial institutions to offer in-kind and financial incentives such as matched savings with varying match rates. The next section considers several cases in more depth, before evaluating relative successes and pitfalls for contractual savings schemes and insurance for education.

Examples of contractual savings schemes for education and skills development: What can we learn from the Western industrialized countries and emerging economies?

Asset-based development policies and programs are occurring in many countries, including Western industrialized and emerging economies, and are increasingly including children (Loke & Sacco, 2011). The examples in Appendix B demonstrate varying long-term savings programs, government supported college saving schemes, and saving schemes linked to schooling and skills acquisition. Such programs necessitate family involvement in that parents and guardians invest in the education and human capital of their children through varying savings products.

Indeed, the examples provided in Appendix B are merely a few of several government-supported savings programs linked to schooling and skills acquisition applied in developed countries. Some of these could provide lessons to sub-Saharan African countries and MENA countries on how to structure contractual savings for educational financing - if these young countries are to optimize the demographic dividend through education.

Selected cases: contractual savings schemes and insurance for education funds

Fundisa South Africa

In South Africa, the Fundisa Fund is a unit trust fund intended for adults who wish to save for a child's tertiary education or public college/university tuition. The Fund can be opened at participating unit trust companies or banks throughout the country. A minimum monthly savings of R40 (US$5) is required. Unique advantages of this account include a state-sponsored bonus of 25 percent of the total yearly deposit, the account opener does not have to be related to the child, and the learner has until age 35 to begin studies at a public college or university. The bonus is a reward for saving and encourages continued savings. Each investor can receive up to a maximum of R600 per year, for each child beneficiary.

Thus, the Fundisa Fund, directly supported by the government, enables anyone, not only family members, to help finance a child's public university tuition (Fundisa, www.fundisa.org.za, accessed November, 2011). When the student is ready to study further, the money is transferred directly to the chosen institution. Both the Department of Education and donations from leading collective investment companies contribute to the bonus. Fundisa was launched in November 2007 (OECD, 2008).

Suubi-Uganda Child Savings Accounts (CSA)

A contractual savings product - funded by the United States Government through the National Institutes of Health research grants (R21 MH076475-01 and; RMH081763A Fred Ssewamala, Principal Investigator), the Suubi-Uganda Programs, encourage orphaned and vulnerable children (OVCs) and their caregivers to save money for the orphans’ education, through partnerships with local banks and microfinance institutions – linking orphaned youth and their families to formal financial institutions. The partnerships with local financial institutions present an integral role in fostering financial literacy and capability among the youth and their families, ensuring sustainability of the child savings account, and enabling families to pay for and invest in the orphans’ education (Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2009). The Child Savings Account (CSA) initiatives are intended for youth to save such that they will accumulate finances in order to fund their post-primary education or invest in a small family business/income-generating activity. A major incentive of the Suubi-Uganda CSA model is that the project matches what the youth or family members deposit at a 2:1 ratio. In order to ensure that this money is used strictly for education-related purposes only, neither the child nor the caregiver has access to the matched funds through standard withdrawal transactions. When the student is ready to pay for school from the matched funds, the money is transferred directly to the chosen institution. The same applies to children who decide to invest in small business development. They have to work with a recognized vendor.

YouthInvest in Egypt and Morocco

In Egypt and Morocco, Mennonite Economic Development Associates (MEDA) offers YouthInvest, which is designed for low-income youth with some education. In response to the high youth unemployment rates in these countries (15- 29 year-olds make up 59.5 and 37 percent of the countries’ total unemployment proportions in Egypt and Morocco, respectively), the YouthInvest Project was implemented in order to build youth's long-term economic prosperity, improve their employability and entrepreneurship skills, increase their ability to seek out and secure meaningful work or entrepreneurial activities, and ultimately lead to a better quality of life for their families and themselves (MEDA YouthInvest, http://www.meda.org/web/images/stories/YouthInvest.pdf, accessed November, 2011). Funded by the MasterCard Foundation and implemented by MEDA, the YouthInvest Project partners with MFIs and NGOs with expertise in preparing youth for business and enterprise development. Youth receive training in life skills, business, entrepreneurship, and financial literacy. Also, YouthInvest aims to increase youth's access to loans and savings, develop products that are appropriate to economically active youth, and encourage on-the-job skills training by placing youth in safe, appropriate, and active businesses as interns. In addition, all participants open a savings account with a commercial banking partner.

YouthSave

YouthSave is a 5-year initiative that is testing and developing youth savings accounts in partnership with commercial banks, youth-serving organizations, and research institutions in Colombia, Ghana, Kenya, and Nepal (YouthSave Consortium, 2010).

Apollo Assurance in Kenya

Apollo Life Assurance in Kenya offers three varieties of education insurance plans. Parents can invest in their children's education with an annual bonus of 4 percent and monthly tax savings. The bonus is calculated based on the sum assured from the first year of the plan, yet is paid only on death or maturity of the plan. The benefits payable on maturity or death are tax-free. It is recommended that parents/guardians invest a minimum monthly deposit of KSh1,500 (US$15) for at least 10 years to finance the cost of high school/secondary school, and monthly deposits of KSh5,000 (US$52) to cover university education. Parents/guardians are allowed to have more than one education plan in order to cover all of their children (Apollo Life Assurance Limited, http://www.apollo.co.ke/, accessed November, 2011). For other details, see the table in Appendix A.

Other Initiatives

A partnership between financial institutions, Population Council, and MicroSave developed and delivered financial services to poor and vulnerable adolescent girls in Kenya and Uganda. Findings from market research indicate that girls who have money would save it in formal financial institutions given the opportunity (Austrian & Ngurukie, 2009).

Equity Bank-Uganda partnered with Banyan Global to develop an education loan product intended to bridge the financial gap for nursing students ages 17-24 in Mbarara, Uganda. Under the partnership, education loans have been customized to students’ school term and are offered at a reduced monthly interest rate of 2 percent (Chandani & Twamuhabwa, 2009).

PLAN International, operating in West Africa, aims to connect young people ages 15-24 in Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Niger to one of the largest youth savings and loan associations, modeled after village savings and loan associations; while in Burundi, CARE International initiated informal savings and credit groups for adolescents and young adults. The Ishaka Project aims to connect girls ages 1-22 to village savings and loan associations and related support services, such as financial and business management and life skills training (Deshpande & Zimmerman, 2010).

Impacts on improving poor children's access to education: sub-Saharan Africa

Research and practice linking young people to savings opportunities suggest that youth-owned savings accounts could benefit poor children and youth vis-à-vis facilitating asset effects which are economic, social, psychological, and behavioral changes caused by asset ownership. These changes have the potential to improve multiple development outcomes for poor and vulnerable youth, as well as benefit the families and households from where the children come.

Financial incentives can appeal to low-income households, for example matched savings. Fundisa in South Africa offers a bonus of up to 25 percent of the total yearly deposit, capping off at US$66. Children participants in the Suubi-Uganda economic empowerment programs - funded by the National Institutes of Health (U.S. Government) received a 2:1 match on deposits, an especially significant incentive for poor orphans (Ssewamala et al., 2008; Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2008, 2009). Results from the Suubi-Uganda program show that orphaned and vulnerable youth receiving the CSA do save. For example, one of the early evaluations of the Suubi-Uganda program indicated that children participating in the program were saving an average of US$76 per year, and after the 2:1 match, the total average was US$228 per year (Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2009). The matched funds were restricted to post-primary education expenses and microenterprise development investments. For details on Suubi-Uganda findings, see (Ssewamala & Ismayilova, 2009).

Impacts on improving youth access to economic participation and skill-building: Middle East and North Africa

The burgeoning youth population in MENA has created the need for innovations aimed at integrating young people into the economy. High unemployment, an irrelevant and inequitable education system, and lack of access to financial services are among the major challenges youth face in MENA. Youth exclusion, resulting in a combination of several challenges highlighted above, is imposing a high cost on society as a whole (Chabaan, 2008).

The YouthInvest Project operates under the hypothesis that addressing these challenges will lead to higher participation in viable and fulfilling economic activities (Harley et al., 2010). Organizations providing business education to young people exist; however, they do not provide the capital for young people to begin entrepreneurial activities. As a result of this gap, YouthInvest aims to connect young people with banks and microfinance institutions, combined with training youth participants in life skills, financial education, workforce readiness, and entrepreneurial activities. Merging training with access to formal financial institutions is especially important for out-of school youth, but also impacts in-school youth. The training in life skills and financial services includes knowledge about how to save, take out a loan, start a business, and enter the workforce (Harley et al., 2010). It is anticipated that youth graduates of this program will have increased ability to adapt to the job market and improve their overall academic performance.

The selected cases described above highlight the burgeoning field of youth financial inclusion in general, and in particular, the financial products and services stipulated for education, and skill and microenterprise development in the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. If these youth-oriented programs can establish a strong base of evidence today, perhaps developing country governments will implement them on a wide scale and/or as national or state policy, as we have seen in Canada, Singapore, South Korea, the United Kingdom (2002-2011) (see Appendix B), and some states in the United States (e.g. the State of Maine). In addition, with a solid evidence base, financial institutions in these and other developing countries may become more willing to form public-private partnerships and offer products and services designed for youth with similar stipulations for the youth to focus on their future. Such public-private partnerships can have far-reaching effects when taken to scale, effects in terms of the investment in youth who are on the cusp of the most economically productive period of their lives, and ensuring that their lives will in fact be productive, and they will be on the trajectory of contributing to their nation's demographic dividend.

Conclusions: synergy between public and private actors in optimizing demographic dividends

There are a variety of ways in which institutions can benefit from offering financial services to youth. As mentioned earlier, the current global youth population is the largest in history, and it is predicted to grow by over one billion within the next decade. If financial institutions do not effectively and comprehensively tap into this growing market, they will miss out on a massive and expanding consumer base. Governments and youth-serving organizations throughout the developing world should partner with financial institutions to create children and youth savings and education insurance products. School-age children must begin saving at an early age in order to increase their likelihood of a future filled with viable prospects and opportunities. Youth, in most cases, reside in households within a family, creating an easily accessible market-base and cross-selling opportunities, making smaller transactions more profitable. Moreover, as youth grow older, they may retain their first account, or at least transfer their funds from the youth account to an adult-oriented account at the same financial institution, which could potentially result in the accumulation of credit, loans, and insurance policies – all part of asset accumulation which began with financial inclusion efforts at an early period of their lives.

Programs, policies, and products geared toward investing in youth may help countries currently experiencing the youth bulge optimize their demographic dividend. Insurance companies, banks, microfinance institutions, governments, and development finance institutions can begin by assessing their own institutional capacities and form partnerships with youth-serving organizations, youth and families, schools, and training institutes to design products for financing education specifically for youth and their caregivers. Examining evidence from successful existing products, programs, and partnerships can help convince national governments and FIs to penetrate the growing market and contribute to this global trend. A solid base of evidence exists that demonstrates the social and economic impact of these financial services on youth and proves the business case for financial-sector involvement. Engaging youth in market research and product development can help FIs design products that address the needs and demands and reflect the diversity of youth that FIs have the potential to serve. Multi-sector partnerships are essential in scaling these products and services. When combined, all of these efforts may help developing countries realize the demographic dividend. Throughout history, we have seen numerous times that when countries invest in their youth, economic growth follows.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

My thanks go to Vilma Ilic, Program Manager at Columbia University School of Social Work International Center for Child Health and Asset Development (ICHAD), and Julia Shu-Huah Wang and Elizabeth Sperber, both Doctoral Candidates at Columbia University, for their help with the initial review of the literature included in this article. Funding for this article came from the KfW Development Bank. This article was originally presented at the KfW Financial Sector Development Symposium in Berlin, Germany, January 18- 20, 2012. Thanks to Dr. Martin Hagen and Piero Violante for organizing the conference, and for all the helpful comments they gave me at the writing of the original version of this paper.

Footnotes

Some youth savings products give youth complete control over their accounts, giving them more autonomy over their finances, but also more responsibility. BancoEstado in Chile allows girls to manage their accounts at age 12 and boys at age 14.

References

- Austrian K, Ngurukie C. Safe and smart savings products for vulnerable adolescent girls in Kenya & Uganda. Making Cents International; Washington, DC: 2009. Youth-Inclusive Financial Services Case Study No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Barro RJ, Lee JW. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950-2010. Journal of Development Economics. 2013;104:184–198. (2013) [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Canning D, Fink G, Finlay JE. Realizing the demographic dividend: Is Africa any different? Harvard University; 2007. Program on the Global Demography of Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Sachs JD. Geography, demography, and economic growth in Africa. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1998;2:207–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Canning D, Sevilla J. The Demographic Dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. RAND; 2003. Population Matters Monograph MR-1274. [Google Scholar]

- Chaaban J. The costs of youth exclusion in the Middle East. Washington, DC: 2008. Wolfensohn Center for Development, The Brookings Institution. Middle Eat Youth Initiative Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Chandani T, Twamuhabwa W. A partnership to offer education loans to nursing students in Uganda. Making Cents International; Washington, DC: 2009. Youth-Inclusive Financial Services Case Study No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy M, Cramer R, Parrish L. Section 529 savings pans, access to post- secondary education, and universal asset building. New American Foundation Asset Building Program; Washington, DC: 2005. Issue Brief #7. [Google Scholar]

- Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) & The World Bank Group . Financial access 2010: The state of financial inclusion through the crisis. Authors; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Curley J, Sherraden M. Policy lessons from children's allowances for children's savings accounts. Child Welfare. 2000;79(6):661–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley J, Ssewamala FM, Han C. Assets and educational outcomes: Child Development Accounts (CDAs) for orphaned children in Uganda. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1585–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande R, Zimmerman JM. Savings accounts for young people in developing countries: Trends in practice. Enterprise Development and Microfinance. 2010;21(4):275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood R, Lipton M. Demographic transition in sub-Saharan Africa: How big will the economic dividend be? Population Studies. 2011;65(1):9–35. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2010.547946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot W., III Children's college aspirations and expectations: the potential role of children's development accounts (CDAs). Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:274–283. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott W, Kim K, Jung H, Zhan M. Asset holding and educational attainment among African American youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:1497–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M, Fares J. Directions in Development, Human Development. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2008. Youth in Africa's labor market. [Google Scholar]

- Grinstein-Weiss M, Yeo YH, Irish K, Zhan M. Parental assets: a pathway to positive child educational outcomes. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare. 2009;36(1):61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Han CH, Kim Y, Zou L. Global Assets Announcement: Child Development Accounts proposed in South Korea. 2006 Retrieved from http://gwbweb.wustl.edu/csd/Publications/2006/Korea_CDA_8-29-06.pdf.

- Harley JG, Sadoq A, Saoudi K, Katerberg L, Denomy J. YouthInvest: A case study of savings behaviour as an indicator of change through experiential learning. Enterprise Development and Microfinance. 2010;21(4):293–306. [Google Scholar]

- HM Treasury Budget 2007: Building Britain's long-term future – prosperity and fairness for families, economic and fiscal strategy report. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/budget/budget_07/report/bud_budget07_repindex.cfm.

- Huang J, Guo B, Kim Y, Sherraden M. Parental income, assets, borrowing constraints and children's post-secondary education. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32:585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme D, Moore K, Barrientos A. Assessing the insurance role of microsavings. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; New York: 2009. Working Paper No. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Human Resources and Skills Development Canada The Canada education savings grant. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/en/hip/lld/cesg/publicsection/CESP/Canada_Education_Savings_Grant_General.shtml.

- International Labour Organization (ILO) Global youth unemployment trends and projections from 2007 to 2013. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/multimedia/maps-and-charts/WCMS_212430/lang--en/index.htm.

- Jaramillo A, Melonio T. Breaking even or breaking through: Reaching financial sustainability while providing high quality standards in higher education in the Middle East and North Africa. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall J, Mylenko N, Ponce A. Measuring financial access around the world. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2010. Policy Research Working Paper, 5253. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Sherraden M. Do parental assets matter for children's educational attainment? Evidence from mediation tests. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33:969–979. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Strategies for sustainable financing of secondary education in sub-Saharan Africa. Africa Human Development Series. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2008. World Bank Working Paper No. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Loke V, Sacco P. Changes in parental assets and children's educational outcomes. Journal of Social Policy. 2011;40(2):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Making Cents International . State of the field in youth enterprise, employment and livelihoods development: Programming and policymaking in youth enterprise, employment, and livelihoods development; and youth-inclusive financial services. Making Cents International; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Zimmerman JM, Boshara R. Global Assets Project. New America Foundation; Washington, DC: 2008. Child savings accounts: Global trends in design and practice. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Masa RD, Zimmerman JM. Overview of child development accounts in developing countries. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010;32(11):1561–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbeek H, Patrinos HA. Financing lifelong learning. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2008. Policy Research Working Paper, 4569. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Taking financial literacy to the next level: Important challenges and promising solutions. Author; Washington, DC: 2008. OECD-US Treasury international conference on financial education. [Google Scholar]

- Roudi-Fahimi F, Kent MM. Challenges and opportunities: The population of the Middle East and North Africa. 2. Vol. 62. Population Bulletin; Washington, DC: 2007. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugaratnam T. Budget 2007 speech. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg.

- Sherraden M. Assets and the poor: A new American welfare policy. M. E. Sharpe; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sherraden M. Research & Policy Brief, Center for Social Development Publication, No. 09-29. Center for Social Development; Washington University, St. Louis: 2009. Savings and educational attainment: The potential of college savings plan to increase educational success. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports 2008 Retrieved from: http://www.mof.gov.sg/budget_2011/expenditure_overview/mcys.html.

- Singapore Ministry of Education Post-secondary education account: Additional support for Singaporeans to pursue further education. 2005 Retrieved from http://stars.nhb.gov.sg/stars/public/viewPDF.jsp?pdfno=20050822986.pdf.

- Ssewamala FM. Children Development Accounts in Africa: A pilot study. Washington University, Center for Social Development; St. Louis: 2005. CSD Working Paper No. 05-05. [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Ismayilova L. Faith-based institutions as project implementers: An innovative economic empowerment intervention for care and support of AIDS-orphaned and vulnerable children in rural Uganda. In: Joshi P, Hawkins S, Novey J, editors. Innovations in effective compassion: Compendium of research papers presented at the faith-based and community initiatives conference on research, outcomes, and evaluation. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. pp. 213–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Alicea S, Bannon WM, Ismayilova L. A novel economic intervention to reduce HIV risks among school-going AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(1):102–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.011. [NIHMSID#172604] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Ismayilova L. Integrating children's savings accounts in the care and support of orphaned adolescents in rural Uganda. Social Service Review. 2009;83(3):453–472. doi: 10.1086/605941. [NIHMSID#172608] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Han C-K, Neilands TB. Asset ownership and health and mental health functioning among AIDS-orphaned adolescents: Findings from a randomized clinical trial in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(2):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.019. [NIHMSID#172769, PubMed#19520472] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Karimli L, Han C-K, Ismayilova L. Social capital, savings, and educational performance of orphaned adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Children and Youth Services Review. 2010a;32(12):1704–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.07.013. [NIHMSID#226111] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Han C-K, Neilands TB, Ismayilova L, Sperber E. Effect of economic assets on sexual risk-taking intentions among orphaned adolescents in Uganda. American Journal of Public Health. 2010b;100(3):483–488. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158840. [NIHMSID#1 PubMed# 20075323] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Sperber E, Zimmerman J, Karimli L. The potential of asset-based development strategies for poverty alleviation in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Social Welfare. 2010c;19(4):433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Ismayilova L, McKay M, Sperber E, Bannon W, Alicea S. Gender and the effects of an economic empowerment program on attitudes toward sexual risk-taking among AIDS-orphaned adolescent youth in Uganda. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010d;46(4):372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.010. [NIHMSID#144977] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA) World population prospects: The 2012 revision. Population Division. UN DESA; New York, NY: 2013. Population Estimates and Projections. [Google Scholar]

- Vilhuber L. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2006. The transition from school to the labor market in Uganda.Preliminary outline presented at the World Bank Youth in Africa's labor market workshop. [Google Scholar]

- YouthSave Consortium . Youth savings in developing countries: Trends in practice, gaps in knowledge. YouthSave Initiative; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan M. Assets, parental expectations and involvement, and children's educational performance. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28:961–975. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.