Summary

Background

HCV-TARGET is a longitudinal observational study of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) in a US consortium of 90 academic and community medical centers.

Aim

To assess utilization of response-guided therapy (RGT) and sustained virologic response (SVR) of a large cohort of patients.

Methods

Patients received peginterferon (PEG-IFN), ribavirin, and either telaprevir or boceprevir. Demographic, clinical, and virological data were collected during treatment and follow-up. RGT and treatment futility stopping rules was assessed at key time points.

Results

Of 2084 patients, 38% had cirrhosis and 56% had received prior treatment for HCV. SVR rates were 31% (95% CI: 24–40) and 50% (95%CI: 44–56) in boceprevir patients with and without cirrhosis, respectively. SVR rates were 46% (95%CI: 42–50) and 60% (95% CI: 57–64) in telaprevir patients with and without cirrhosis, respectively. Early clearance of virus, IL28B genotype, platelet counts, and diabetes were identified as predictors of SVR among boceprevir patients, while early clearance of virus, IL28B, cirrhosis, HCV subtype, age, hemoglobin, bilirubin and albumin levels were identified as predictors of SVR for telaprevir patients.

Conclusions

In academic and community centers, triple therapy including boceprevir or telaprevir led to SVR rates somewhat lower than those noted in large phase 3 clinical trials. Response rates were consistently higher among patients without cirrhosis compared to those with cirrhosis regardless of DAA used and prior treatment response. Trial registration clinicaltrials.gov NCT01474811.

Introduction

It is estimated that between 2% and 3% of the global population is infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), corresponding to approximately 130–170 million individuals.1–3 Chronic hepatitis C is one of the most common causes of liver disease in the United States and is responsible for approximately 12,000 deaths annually. Furthermore, it is expected that the morbidity and mortality associated with HCV infection will continue to increase over the next few decades.2,4,5 Until recently, the treatment of HCV included 48 weeks of peginterferon (PEG-IFN) combined with ribavirin (RBV) yielding sustained virologic response (SVR) rates of 40–50% for those with genotype 1.

In May 2011, the FDA approved two HCV NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors (PI), boceprevir and telaprevir for use in the United States, representing one of the most important advances in the management of chronic HCV genotype 1 in nearly a decade. The addition of a PI to PEG-IFN and RBV reportedly improved SVR rates to 60–75%.6–11 Importantly, these studies also allowed for development of response-guided therapy (RGT) algorithms and of new treatment futility stopping rules.12,13 RGT, whereby treatment duration is shortened to 24 or 28 weeks in patients with rapid virological response, defined as undetectable HCV RNA by week 4 with telaprevir or week 8 with boceprevir-based regimen respectively, is the standard of care for non-cirrhotic patients. This allows one-half to two-thirds of treatment-naïve patients treated with these medications to require only 24–28 weeks of total treatment with the same success rate as a 48-week course.7,8

HCV-TARGET, an observational study of patients with chronic HCV treated within the United States, provides the opportunity to better understand the impact of these drugs on a large cross-section of patients with hepatitis C in the United States. The evaluation of these regimens in a real world setting may provide data that could then be used as a comparator for next-generation therapies, including all oral therapies that are rapidly advancing clinical care.

The aims of this study were to characterize the rates of the virologic responses to the treatment regimens in terms of patient characteristics, and to observe practical application of RGT in order to assess adherence to treatment futility stopping rules in a large cohort of patients in both academic and community practices.

Methods

Study population and design

HCV-TARGET (HCVT, ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01474811) is a longitudinal, observational study performed by a consortium of academic (n=38) and community (n=52) medical centers in the US. From May 2011 to September 2012, patients treated with peginterferon and ribavirin in combination with boceprevir or telaprevir were enrolled. This study was designed to capture data for populations that were underrepresented by clinical trials; therefore inclusion criteria were very broad. All adult patients (18 years or older) being treated with antiviral regimens that contained telaprevir or boceprevir at participating study sites were eligible to be included.

Treatment was administered per local standards at the study site. The study protocol did not define specific treatment populations, regimens, dosing, or safety management guidelines. Data was captured from enrolled patients using a central database and novel standardized source data abstraction methods. A centralized team of trained coders reviewed all de-identified medical records obtained from participating sites for data entry. Throughout treatment and during post-treatment follow-up, demographic, clinical, adverse event, and virological data were collected. Independent data monitors systematically reviewed the data entries for completeness and accuracy. All database records were screened for extreme or unlikely values and verified/resolved with additional queries. Data from 301 patients from PEGBASE-USA, an Observational Study of Peginterferon [e.g. Pegasys®]-Based Direct Acting Antiviral Triple Therapy in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 1 (NCT01508130), funded by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA) were mapped to harmonize with the HCV-TARGET database and were included in the analyses reported here.

Patients received peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin plus either telaprevir or boceprevir in accordance with local standard of care and US labeling and were followed for the duration of their treatment and for up to 24 weeks post-treatment. Treating physicians were encouraged to follow RGT based on US labeling information. The protocol was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. A central IRB approved the protocol if a local IRB and independent ethics committee at each participating study center was not in place. All patients provided written informed consent for their participation or an informed consent waiver was granted by the IRB overseeing the site.

Definitions

Treatment-naïve participants were those who had never received interferon-based treatment for HCV, whereas treatment experienced patients had received treatment with an interferon-based regimen at any point prior to the current treatment with protease inhibitor-based treatment. Subcategories of treatment-experienced patients were defined by the investigators based upon their clinical evaluation and data available to them in routine practice. Thus, null responders had received at least 12 weeks of PEG-IFN and RBV with HCV RNA decrease <2 log10 at week 12; partial responders had an HCV RNA decrease ≥2 log10 by week 12 of treatment but remained detectable; prior relapsers were defined as patients who completed a prescribed course of PEG-IFN and RBV, becoming HCV RNA undetectable during therapy, but relapsed with detectable HCV RNA once treatment was discontinued; unknown response was defined as patients who have previously completed a prescribed course of PEG-IFN and RBV but whose treatment response based on HCV RNA determinations was not available; and prior intolerant as those patients who were treated with PEG-IFN and RBV but discontinued due to adverse event or patient choice prior to completion of therapy. Finally, other treatment included those patients who were treated with a non-peginterferon based regimen (such as interferon-alfa only, ribavirin plus interferon alfa-2b, interferon alfacon-1). If a patient had other treatment and a subsequent course of therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin, the patient was defined according to their PEG-IFN/RBV treatment experience.

The criteria for the diagnosis of cirrhosis were either confirmation by liver biopsy or a combination of clinical, laboratory, histologic, and imaging features. Patients with the equivalent of stage 3 fibrosis (bridging fibrosis) by liver biopsy were defined as cirrhotic if they had any of the following: platelets count <140,000 per μL, presence of esophageal varices on esophagogastroduodenoscopy, nodular liver, portal hypertension, or ascites by radiologic imaging, or FibroSure test or equivalent compatible with stage 4 fibrosis. In the absence of liver biopsy, cirrhosis was defined by exhibiting two or more of the above non-histologic criteria.

A commonly used approach to RGT in patients without cirrhosis is for patients with undetetectable HCV RNA at weeks 4 and 12 (telaprevir patients) or 8 and 12 (boceprevir patients) to receive a total of 24–28 weeks of therapy, while those with detectable HCV RNA at week 4 or 8 but undetectable at week 12 received a total of 48 weeks of therapy.

Primary endpoint and HCV RNA assays

The primary endpoint for the virological analysis was SVR, defined as serum HCV RNA reported as Below Level of Quantitation (BLOQ) at least 10 weeks beyond the end of treatment. This definition provides a 2-week buffer for the standard 12-week definition to account for variability in clinic visits in routine practice. Patients lost to follow-up, who withdrew from the study, and patients with quantifiable HCV RNA who discontinued treatment prematurely were considered to have failed treatment. HCV RNA assays were performed locally and reflect those used in routine clinical practice throughout the United States. Source data from actual reports of serum HCV RNA testing was abstracted and entered into the HCVT database. For results where HCV RNA was BLOQ, additional information regarding “Detectable”, “Undetectable” or “Not Specified” was captured from the report.

Secondary virological endpoints included the frequency of HCV RNA BLOQ at various time points during treatment; the rate of relapse among those BLOQ at the end of treatment who subsequently had detectable HCV RNA post-therapy; and virological breakthrough (VBT) defined as BLOQ recorded during treatment but HCV RNA detectable on subsequent testing while still on therapy. Adherence to treatment futility stopping rules, per the labeled package inserts of boceprevir and telaprevir, was also captured.

Statistical Analysis

To assess the practical use of RGT and adherence to treatment futility stopping rules, simple counts of patients meeting various criteria were tabulated for analysis. Rates of SVR for each treatment regimen, collectively and in subgroups of interest, were tabulated along with their 95% confidence intervals. To identify potential predictors of SVR from a set of baseline variables selected a priori, multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. The set of variables of potential interest were selected a priori based upon a consensus of clinical expertise. The logistic models were restricted to HCV genotype 1 patients. To cope with occasional missing values in the baseline measurements, the method of multiple imputation (using SAS PROC MI software) was to impute values conditional on other available measurements. All statistical computations were performed using SAS software (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R software (version 3.0.2, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient Characteristics

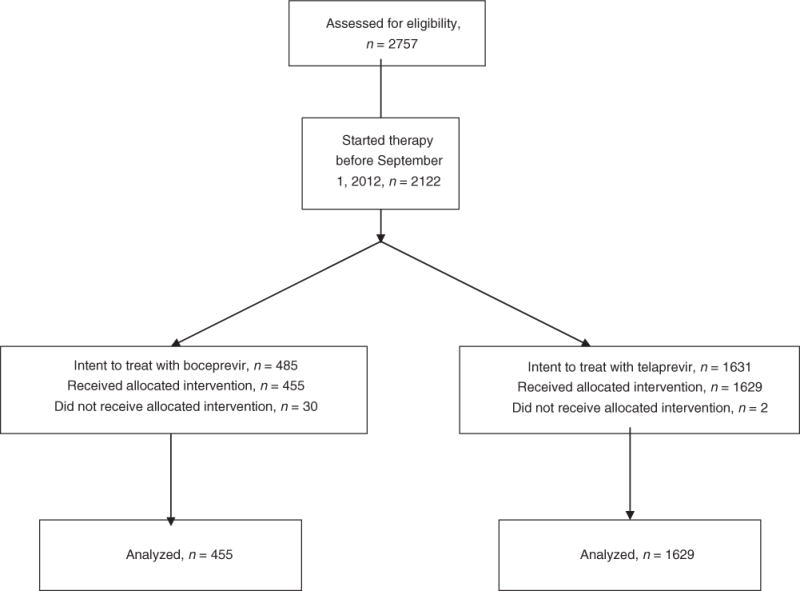

During the study period, 2,757 patients with chronic hepatitis C were evaluated for HCV therapy and enrolled into HCVT (Figure 1). Of these, 2,122 started HCV therapy prior to September 2012, and 2,084 (98%) received at least one dose of a PI and were included in the final analysis. The demographic features of these patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age of patients was 56 years, 61% were male, 79% were white, and 38% had cirrhosis (Table 1). Overall, 97% were infected with HCV genotype 1 and 71% had a high HCV viral load (≥800,000 IU/ml). A total of 18 liver transplant patients were enrolled in this study, 9 received boceprevir-based therapy and 9 telaprevir-based therapy. In addition, 5 patients co-infected with HCV and HIV were treated with boceprevir and 51 with telaprevir. A higher proportion of patients with cirrhosis were treated with telaprevir compared to boceprevir (40% vs. 31%, P<0.001). Most patients (57%) were treatment experienced with the highest proportion being prior relapsers (23%).

Figure 1.

Disposition of Patients from Enrollment to Treatment Initiation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristic | Boceprevir (n=455) |

Telaprevir (n=1,629) |

Total (n=2,084) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 55 (20–77) | 56 (18–75) | 56 (18–77) |

|

| |||

| Male sex, n (%) | 283 (62) | 982 (60) | 1,265 (61) |

|

| |||

| Median BMI (range), kg/m2 | 28 (18–57) | 28 (16–69) | 28 (16–69) |

|

| |||

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 364 (80) | 1,281 (79) | 1,645 (79) |

| Black | 66 (15) | 277 (17) | 343 (16) |

| Asian | 13 (3) | 33 (2) | 46 (2) |

| Other/missing | 12 (3) | 38 (2) | 50 (2) |

|

| |||

| Hispanic ethnicity,1 n (%) | 28 (6) | 103 (6) | 131 (6) |

|

| |||

| Mean ALT (SD), mean IU/l | 88 (81) | 92 (78) | 91 (79) |

|

| |||

| Mean total bilirubin (SD), mg/dl | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.5) |

|

| |||

| Mean albumin (range), g/dl | 4.1 (1.4–5.1) | 4.0 (1.0–5.1) | 4.1 (1.0–5.1) |

|

| |||

| Mean hemoglobin (SD), g/dl | 15 (1.5) | 15 (1.4) | 15 (1.4) |

|

| |||

| Mean platelet count (range), per μL | 182,200 (33,000–472,000) | 173,110 (25,000–500,000) | 175,110 (25,000–500,000) |

|

| |||

| Presence of cirrhosis,2 n (%) | 140 (31) | 648 (40) | 788 (38) |

|

| |||

| History of esophageal varices,3 n (%) | 56 (12) | 213 (13) | 269 (13) |

|

| |||

| Presence of diabetes, n (%) | 79 (17) | 224 (14) | 303 (15) |

|

| |||

| IL28B genotype, n (%) | |||

| CC | 60 (13) | 152 (9) | 212 (10) |

| CT, TT | 142 (31) | 393 (24) | 535 (26) |

| Unknown | 253 (56) | 1,084 (67) | 1,337 (64) |

|

| |||

| HCV genotype, n (%) | |||

| 1a | 254 (56) | 914 (56) | 1,168 (56) |

| 1b | 105 (23) | 380 (23) | 485 (23) |

| 1, subtype unspecified | 86 (19) | 286 (18) | 372 (18) |

| Other | 10 (2) | 49 (3) | 59 (3) |

|

| |||

| Prior HCV treatment, n (%) | |||

| Treatment naïve | 201 (44) | 701 (43) | 902 (43) |

| Treatment experienced* | 254 (56) | 925 (57) | 1,179 (57) |

| Prior relapse | 98 (22) | 390 (24) | 488 (23) |

| Prior null responder | 34 (7) | 172 (11) | 206 (10) |

| Prior partial responder | 28 (6) | 109 (7) | 137 (7) |

| Unknown, multiple response | 0 | 3 (<1) | 3 (<1) |

|

| |||

| HCV RNA ≥800,000 IU/ml, n (%) | 321 (71) | 1,150 (71) | 1,471 (71) |

Data available on 2,064 patients

Data available on 2,045 patients

Data available on 794 patients

Including 197 treatment-experienced patients with unknown response, 96 prior interferon-intolerant patients, and 31 patients with prior viral breakthrough

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HCV, hepatitis C virus;

Response to Treatment

Boceprevir

The overall SVR rates for treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients who received boceprevir were 52% (95% CI: 45–59) and 38% (95% CI: 32–44), respectively (Table 2a). SVR rates were similar in patients who received boceprevir in combination with PEG-IGN alfa-2a (45%, 95%CI: 40–51) or with PEG-IFN alfa-2b (44%, 95%CI: 35–54). Two (2/5) HIV patients treated with boceprevir achieved SVR. SVR rates were higher among patients without cirrhosis as compared to patients with cirrhosis in most subgroups studied, regardless of prior treatment response. Overall SVR rates for patients with cirrhosis and patients without cirrhosis who received boceprevir were 31% (95%CI: 24–40) and 50% (95% CI: 44–56), respectively. When stratified by treatment experience, 59% (95% CI: 51–67) of treatment-naïve patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR compared with 32% (95% CI: 20–47) of patients with cirrhosis, and 42% percent (95% CI: 34–50) of treatment-experienced patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR compared with 31% (95% CI: 22–42) of patients with cirrhosis. The highest SVR rate (66%, 95% CI: 53–77) was observed in patients without cirrhosis who had experienced relapse during prior treatment.

Table 2a.

Sustained Virologic Response in boceprevir patients

| Patients with cirrhosis (n=140) |

Patients without cirrhosis (n=310) |

Total* (n=455) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n/N (%, 95%CI) | n/N (%, 95% CI) | n/N (%, 95% CI) | |

| Overall SVR | |||

|

| |||

| All patients | 44/140 (31, 24–40) |

155/310 (50, 44–56) |

200/455 (44, 39–49) |

|

| |||

| SVR by prior treatment response | |||

|

| |||

| Treatment-naïve | 16/50 (32, 20–47) |

87/147 (59, 51–67) |

104/201 (52, 45–59) |

| Treatment-experienced | 28/90 (31, 22–42) |

68/163 (42, 34–50) |

96/254 (38, 32–44) |

| Prior relapse | 13/30 (43, 25–63) |

44/67 (66, 53–77) |

57/98 (58, 48–68) |

| Prior null response | 2/11 (18, 2–52) |

8/23 (35, 16–57) |

10/34 (29, 15–47) |

| Prior partial response | 3/12 (25, 5–57) |

3/16 (19, 4–46) |

6/28 (21, 8–41) |

| Prior breakthrough | 1/2 (50, 1–99) |

2/6 (33, 4–78) |

3/8 (38, 9–76) |

| Prior response unknown | 3/22 (14, 3–35) |

8/32 (25, 11–43) |

11/54 (20, 11–34) |

| Prior interferon intolerant | 6/10 (60), 26–88 |

3/19 (16, 3–40) |

9/29 (31, 15–51) |

|

| |||

| SVR by race | |||

|

| |||

| White | 39/115 (34, 25–43) |

125/244 (51, 45–58) |

165/364 (45, 40–51) |

| Black | 2/15 (13, 2–40) |

19/51 (37, 24–52) |

21/66 (32, 21–44) |

|

| |||

| SVR by IL28B status | |||

|

| |||

| CC | 7/15 (47, 21–73) |

31/44 (70, 55–83) |

39/60 (65, 52–77) |

| CT, TT | 7/46 (15, 6–29) |

29/96 (30, 21–40) |

36/142 (25, 18–33) |

|

| |||

| SVR according to presence of diabetes | |||

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 5/33 (15, 5–32) |

18/44 (41, 26–57) |

23/79 (29, 19–40) |

| No diabetes | 39/107 (36, 27–46) |

137/266 (52, 45–58) |

177/376 (47, 38–56) |

|

| |||

| SVR by HCV genotype | |||

|

| |||

| 1a | 22/81 (27, 18–38) |

87/169 (51, 44–59) |

110/254 (43, 37–50) |

| 1b | 16/32 (50, 32–68) |

34/72 (47, 35–59) |

50/105 (48, 38–58) |

|

| |||

| SVR by HCV RNA level | |||

|

| |||

| <800,000 copies/mL | 17/45 (38, 24–53) |

45/86 (52, 41–63) |

63/134 (47, 38–59) |

| ≥800,000 copies/mL | 27/95 (28, 20–39) |

110/224 (49, 42–56) |

137/321 (43, 37–48) |

SVR: sustained virologic response

Including 5 patients with missing cirrhosis status

We investigated differences in SVR rates based on use of various quantitative assays for HCV RNA. Among patients who were BLOQ at treatment week 8, 64% (95% CI: 55–73) of treatment-naïve and 65% (95% CI: 55–75) of treatment-experienced patients subsequently achieved SVR (Supplemental Table 1). Highest SVR rates were achieved among treatment-naïve patients who were BLOQ/undetectable at treatment week 8 (72%, 95%CI: 61–82) compared to those who were BLOQ but had detectable RNA levels (35%, 95%CI: 14–62); however, SVR rates were similar in treatment-experienced patients with HCV RNA undetectable (63%, 95%CI: 49–76) or detectable (65%, 95% CI: 45–81) (Supplemental Table 1).

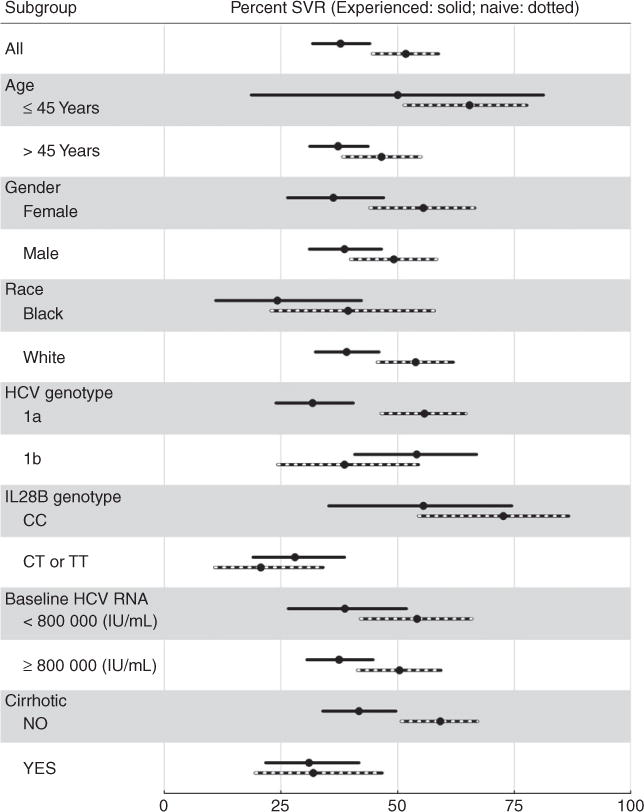

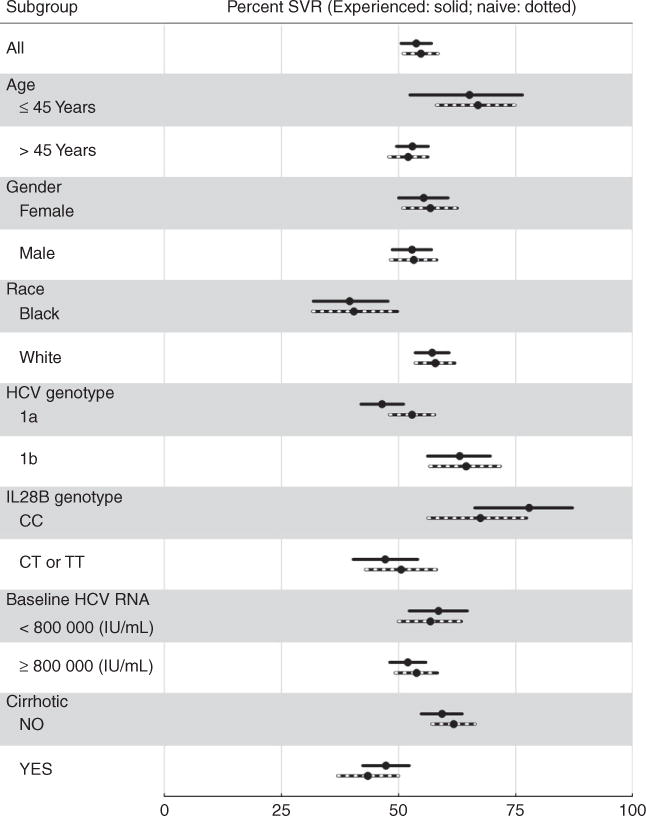

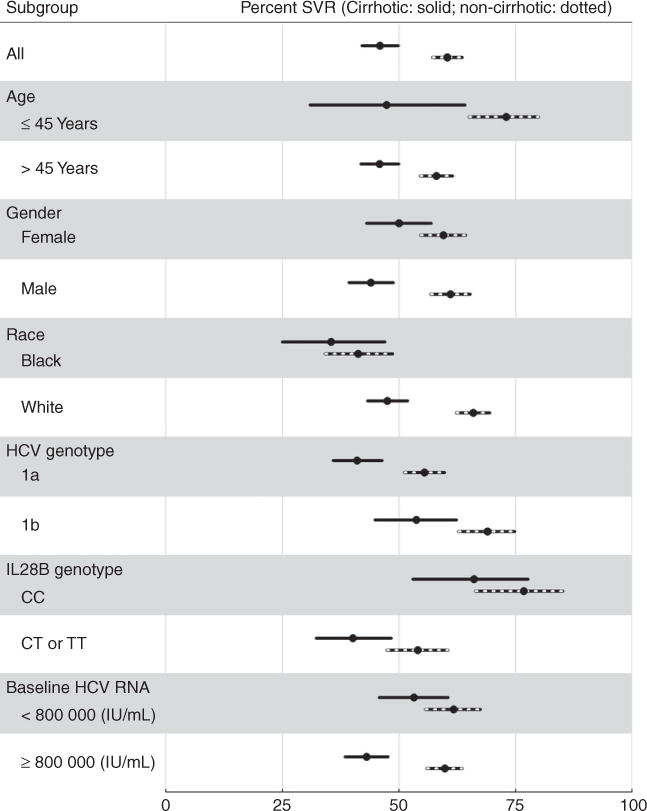

Figure 2 shows unadjusted SVR rates within subgroups defined by age, sex, race, genotype 1 subtype, IL28B, and baseline HCV RNA levels in treatment-naïve and treatment experienced patients treated with boceprevir. Similarly, Figure 3 shows unadjusted SVR rates among patients with and without cirrhosis within those same subgroups.

Figure 2.

Sustained virologic responses and 95% CI in total population and in various subpopulations of chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1, treated with boceprevir and stratified by treatment experienced (254 patients) vs. treatment naïve (201 patients).

Figure 3.

Sustained virologic responses and 95% CI in total population and in various subpopulations of chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1, treated with boceprevir and stratified by cirrhosis (140 patients) vs. no cirrhosis (310 patients).

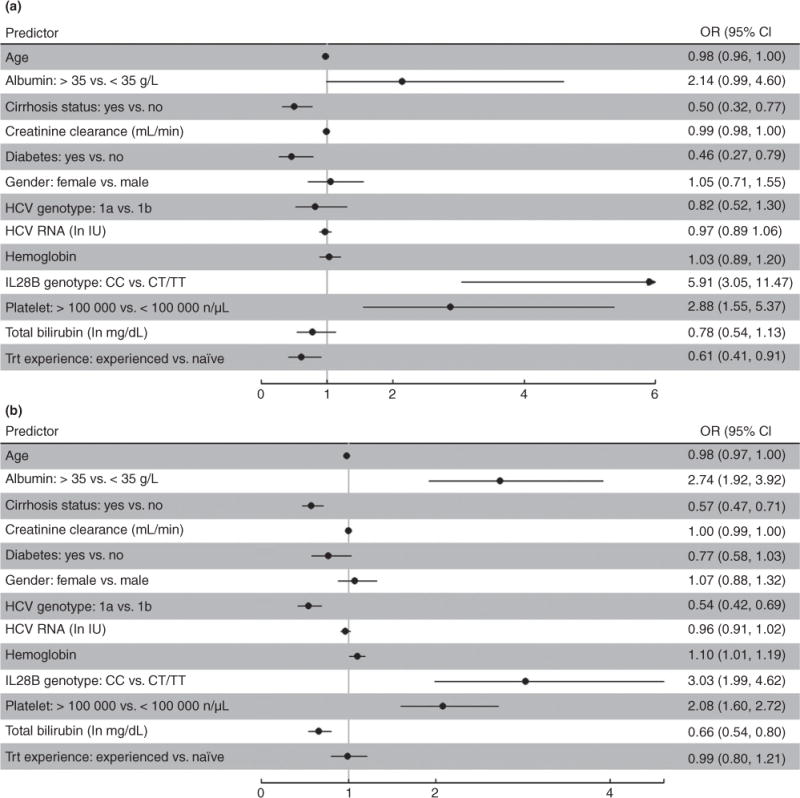

To identify potential baseline predictors of SVR in genotype 1 patients, the following variables were considered: creatinine clearance, platelets, hemoglobin values, albumin values, total bilirubin, HCV RNA units, sex, age, cirrhosis status, diabetes status, previous treatment experience, HCV genotype, and IL28B genotype. SVR odds ratios (OR) for these variables, adjusted for age and race, reported in Figure 4A suggest that absence of cirrhosis, lack of previous treatment experience, IL28B genotype CC, higher platelet levels, absence of diabetes, and perhaps higher albumin levels, may be useful predictors of achieving SVR among boceprevir patients. As expected, these results are consistent with the stratified estimates of SVR rates in Table 2a and Figures 2 and 3; for example, 65% of IL28B genotype CC patients achieved SVR compared to 25% of their counterparts. And for example, 47% of non-diabetics patients achieved SVR compared to 30% of diabetics.

Figure 4.

Age- and gender- adjusted odd ratio estimates and 95% CI for the association of various predictors and SVR to antiviral therapy with boceprevir (A) or telaprevir (B) in chronic hepatitis C patients. Black dots indicate point estimate for OR.

Telaprevir

The overall SVR rates for treatment-naïve and treatment-experienced patients on telaprevir were 55% (95%CI: 51–59) and 54% (95%CI: 51–57), respectively. SVR rates were similar in patients who received telaprevir in combination with PEG-IGN alfa-2a (56%, 95%CI: 54–59) or with PEG-IFN alfa-2b (53%, 95%CI: 43–63). Sixty-one percent (31/51) HIV patients treated with telaprevir achieved SVR. SVR rates were consistently higher in patients without cirrhosis (60% overall, 95% CI: 57–64) as compared to patients with cirrhosis (46% overall, 95% CI: 42–50) regardless of prior treatment response, except in the few patients who had experienced prior virological breakthrough (Table 2b). When stratified by treatment experience, 62% (95% CI: 57–66) of treatment-naïve patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR compared with 44% (95% CI: 37–50) of patients with cirrhosis, and 59% percent (95% CI: 55–64) of treatment-experienced patients without cirrhosis achieved SVR compared with 47% (95% CI: 43–52) of patients with cirrhosis. The highest SVR rate (76%, 95% CI: 70–81) was observed in patients without cirrhosis who had experienced relapse during prior treatment (Table 2b).

Table 2b.

Sustained Virologic Response in telaprevir patients

| Patients with cirrhosis (n=648) |

Patients without cirrhosis (n=947) |

Total* (n=1,629) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n/N (%, 95%CI) | n/N (%, 95% CI) | n/N (%, 95% CI) | |

| Overall SVR | |||

|

| |||

| All patients | 298/648 (46, 42–50) |

572/947 (60, 57–64) |

883/1,629 (54, 52–56) |

|

| |||

| SVR by prior treatment response | |||

|

| |||

| Treatment-naïve | 103/237 (44, 37–50) |

272/440 (62, 57–66) |

384/701 (55, 51–59) |

| Treatment-experienced | 194/410 (47, 43–52) |

300/506 (59, 55–64) |

498/925 (54, 51–57) |

| Prior relapse | 98/148 (66, 58–74) |

181/239 (76, 70–81) |

281/390 (72, 67–76) |

| Prior null response | 22/87 (25, 17–36) |

31/84 (37, 27–48) |

53/172 (31, 24–38) |

| Prior partial response | 31/61 (51, 38–64) |

26/48 (54, 39–69) |

57/109 (52, 43–62) |

| Prior breakthrough | 8/13 (62, 32–86) |

6/10 (60, 26–88) |

14/23 (61, 39–80) |

| Prior response unknown | 25/72 (35, 24–47) |

25/70 (36, 25–48) |

51/143 (36, 28–44) |

| Prior interferon intolerant | 9/24 (38, 19–59) |

23/41 (56, 40–72) |

33/67 (49, 37–62) |

|

| |||

| SVR by race | |||

|

| |||

| White | 261/549 (48, 43–52) |

468/708 (66, 62–70) |

738/1281 (58, 55–60) |

| Black | 28/79 (35, 25–47) |

78/189 (41, 34–49) |

110/277 (40, 34–46) |

|

| |||

| SVR by IL28B status | |||

|

| |||

| CC | 41/62 (66, 53–78) |

66/86 (77, 66–85) |

110/152 (72, 65–79) |

| CT, TT | 61/152 (40, 32–48) |

127/235 (54, 47–61) |

191/393 (49, 44–54) |

|

| |||

| SVR according to presence of diabetes | |||

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 54/122 (44, 35–54) |

51/101 (50, 40–61) |

105/224 (47, 40–54) |

| No diabetes | 244/526 (46, 42–51) |

521/846 (62, 58–65) |

778/1,405 (55, 53–58) |

|

| |||

| SVR by HCV genotype | |||

|

| |||

| 1a | 145/353 (41, 36–46) |

297/535 (56, 51–60) |

452/914 (49, 46–53) |

| 1b | 72/134 (54, 45–62) |

167/242 (70, 63–75) |

242/380 (64, 59–69) |

|

| |||

| SVR by HCV RNA level | |||

|

| |||

| <800,000 copies/mL | 99/186 (53, 46–61) |

171/277 (62, 56–67) |

276/479 (58, 53–62) |

| ≥800,000 copies/mL | 199/462 (43), 39–48 |

401/670 (60, 56–64) |

607/1,150 (53, 50–56) |

SVR12: sustained virologic response at 12 weeks

Including 34 patients with missing cirrhosis status

Among patients who were BLOQ at treatment week 4, 64% (95%CI: 60–69) of treatment-naïve and 63% (95%CI: 59–67) of treatment-experienced patients subsequently achieved SVR (Supplemental Table 1). Highest SVR rates were achieved among those who were BLOQ/undetectable at treatment week 4 compared to those who were BLOQ but had detectable RNA levels: 68% (95% CI: 62–73) of treatment-naïve patients and 70% (95% CI: 65–75) of treatment-experienced patients with BLOQ vs. 51% (95%CI: 42–61) of treatment-naïve patients and 50% (95%CI: 42–58) of treatment-experienced patients with HCV RNA BLOQ but detectable (Supplemental Table 1).

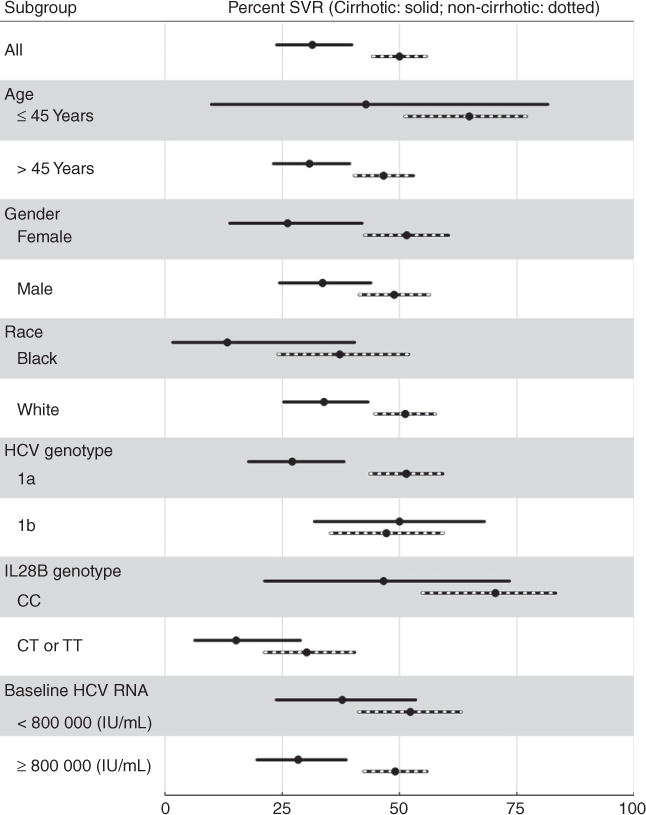

Figure 5 shows unadjusted SVR rates within subgroups defined by age, sex, race, genotype 1 subtype, IL28B, and baseline HCV RNA levels in treatment-naïve and treatment experienced patients treated with telaprevir. Similarly, Figure 6 shows unadjusted SVR rates for telaprevir among patients with and without cirrhosis within those same subgroups.

Figure 5.

Sustained virologic responses and 95% CI in various subpopulations of chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1, treated with telaprevir and stratified by treatment experienced (925 patients) vs. treatment naïve (701 patients).

Figure 6.

Sustained virologic responses and 95% CI in various subpopulations of chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1, treated with telaprevir and stratified by cirrhosis (648 patients) vs. no cirrhosis (947 patients).

Figure 4B reports SVR OR for the baseline variables selected a priori in genotype 1 telaprevir patients. Adjusted for age and race, these odds ratios suggest that absence of cirrhosis, IL28B genotype CC, higher platelet levels, HCV genotype 1b, higher albumin, lower bilirubin, higher hemoglobin, and perhaps absence of diabetes, may be useful predictors of achieving SVR in telaprevir patients. As expected, these results are consistent with the stratified estimates of SVR rates in Table 2b and Figures 5 and 6; e.g., 64% of genotype-1b patients achieved SVR compared to 49% of genotype 1a patients.

Interestingly, treatment experience was not predictive of SVR in the telaprevir patients, with very similar SVR rates in patients with (54%) and without (55%) treatment experience.

Adherence to Futility Recommendations

Of the patients who started boceprevir after lead-in (n=424), 372 were still on treatment at week 12 (Supplemental Table 2). The reasons for discontinuing treatment prior to week 12 were adverse events (n=35), lack of response (n=9), and other (n=8). At week 12 (defined as treatment day 77–90), HCV RNA was assessed in 95% of patients (352). Of these, 292 (83%) had HCV RNA less or equal to 100 IU/ml and continued therapy and 60 (17%) had HCV RNA >100 IU/ml, of those 20 patients stopped therapy prior to week 14. Therefore, adherence to RGT with boceprevir was 312/372 (84%). Among the patients who remained on treatment, SVR was observed in 167/292 (57%, 95%CI: 51–63) of the patients with HCV RNA ≤100 IU/ml at week 12 who completed 28 weeks of treatment and in 2/11 (18%, 95%CI: 2–52) of those with >100 IU/ml at week 12 who completed 48 weeks of treatment according to RGT. Most of the boceprevir patients with HCV RNA >100 IU/ml (n=60) at week 12 discontinued treatment (median 109 days; range 91–284) in keeping with RGT recommendation.

Of the patients who started telaprevir (n=1,629), 1,390 (85%) had HCV viral load assessed at week 4 (defined as treatment day 21–34) (Supplemental Table 2). Those with HCV RNA ≤1,000 IU/ml (n=1,323) continued RGT and 745/1,323 achieved SVR (57%, 95%CI: 54–59). Of those with HCV RNA >1,000 IU/ml (n=67) at week 4, most discontinued treatment at a later visit (median 63 days; range 37–287) while only 10 completed a full course. Of those with HCV RNA >1,000 IU/ml at week 4, SVR was achieved in 9/67 patients (14%, 95%CI: 6–24). Adherence to RGT in telaprevir patients was 97% (1,333/1,390). No difference in adherence to RGT was observed between academic and community sites (data not shown).

Because patients with cirrhosis are not considered candidates for RGT and are recommended to receive 48 weeks of therapy, we analyzed those with cirrhosis separately to assess the adherence to this recommendation and to assess virological outcomes. Of 788 patients, 403 (51%) completed the prescribed course of therapy (68 with boceprevir and 335 with telaprevir-based therapy) without premature discontinuation due to AE or lack of efficacy. The mean duration of treatment among cirrhotic patients that completed therapy was 44.4 weeks (range 22.6–57.3 weeks) with a SVR rate of 70% (60% with boceprevir and 72% with telaprevir based therapy). The 106 genotype 1 prior relapsers with cirrhosis treated with telaprevir, excluding patients with incomplete treatment duration were analyzed. Of those, 18 were treated for 24 weeks or less and 8 (44%, 95%CI: 22–69) achieved SVR, whereas 88 were treated for more than 24 weeks and 67 (76%, 95%CI: 66–85) achieved SVR (Supplemental Figure 1), indicating that prior relapsers with cirrhosis achieved better outcomes when treated for 48 weeks.

Discussion

After the approval of boceprevir and telaprevir in the US in May 2011, their use in combination with PEG-IFN and ribavirin rapidly became the standard of care for treatment of genotype 1 HCV and was associated with increased SVR compared to PEG-IFN and ribavirin alone. This is important as patients who achieve SVR with antiviral therapy have long-term clinical benefits compared to treatment failures.14–19 In this report, we describe the largest experience to date on the unrestricted use of triple therapy and utilization of RGT algorithms.

The HCV-TARGET population had more patients with cirrhosis (38%) compared to most trials (10–25%), the majority of patients (78%) received telaprevir, and 57% were treatment-experienced, reflective of the patient population undergoing treatment in the DAA era. In treatment-naïve patients, SVR rates were similar in those receiving boceprevir (52%) and telaprevir (55%), rates lower than those observed in phase III clinical trials (65–75%),6–8 as observed in other reports in routine clinical practice.20 In treatment-experienced patients, SVR was highest in those with prior relapse (58% and 72% in boceprevir and telaprevir patients, respectively) and lowest in those with prior null response (29% and 31% in boceprevir and telaprevir patients, respectively). Seventy-five percent of prior relapsers and 52% of prior non-responders treated with a fixed triple therapy boceprevir regimen achieved SVR. Relapsers and prior partial responders in the response-guided treatment arm had SVR rates of 69% and 40%, respectively.10 The lower SVR rates observed in HCV-TARGET compared with those reported in clinical trials could be explained by the higher proportion of patients with cirrhosis and of African-American patients in our study, factors that have all been associated with lower SVR.21,22

Adherence to RGT was high: 84% for boceprevir and 97% for telaprevir. The higher rate for telaprevir may be due to its simpler treatment algorithm. In prior relapsers treated with telaprevir, similar SVR were observed in non-cirrhotics patients treated for 24 weeks (80%) or longer (83%) whereas more cirrhotic patients achieved SVR when treated for >24 weeks (76%) as compared to those who received 24 weeks of treatment (44%). These data support the FDA recommendation to use RGT in prior relapsers to PEG-IFN and ribavirin undergoing retreatment with telaprevir,23 and the longer treatment course duration of prior cirrhotic relapsers with telaprevir. In addition to RGT, stopping rules have also been revised for PI-based therapy.12 In this study, stopping rules for antiviral therapy were correctly followed in 30–33% of patients, who stopped treatment within 12 days of meeting futility rules. In those who continued treatment despite meeting futility rules, only 5% of boceprevir patients and 11% of telaprevir patients achieved SVR, supporting the recommendations that treatment be stopped in these individuals. As expected, those with BLOQ/undetectable HCV RNA at key time points had higher SVR rates compared to those who had HCV RNA BLOQ but detectable, reflecting the presence of ongoing viral replication.24,25

As previously reported,26 rates of anemia and treatment discontinuations in HCV-TARGET were far higher than reported for the pivotal registration trials, and similar to those observed in a large studies in European patients with compensated cirrhosis,27 highlighting the reduced tolerability of these regimen in patients with advanced disease. Findings from both studies identified baseline level of platelets and anemia as important baseline factors to take into consideration during treatment decision.26,27

There were several pragmatic features and limitations in our study. First, because all patients were treated as standard of care based on local practice, differences among patient populations or among sites, including academic and community sites may have affected our results. In addition, week 4 and week 12 samples were rarely re-tested, which could have led to higher accuracy of SVR prediction as described in patients treated with telaprevir.28 We also did not systematically assess adherence, which has been shown to impact SVR in triple therapy.29 Nor did we capture the proportion of uninsured patients in this study. Access to care and HCV medications is an important component of care. A recent study in the DAA era of uninsured patients showed that despite access to care and medications, the utility of evaluation and initiation of treatment remained low suggesting that eliminating barriers to health care may not lead to an increase in treatment rates.30

HCV-TARGET represents the largest prospective cohort of HCV treated patients in the U.S. and allows an in-depth analysis of “real life” experience of HCV patients treated with first generation DAAs. As HCV treatment evolves from first generation protease inhibitors to sofosbuvir, simeprevir and other emerging interferon-free regimens, it is important to consider that patients treated in real-life are likely to be more diverse, have more advanced fibrosis, and have more comorbidities than patients included in registration trials. SVR rates, as demonstrated in our study, could be lower than predicted. This difference in real-life SVR rates may have a large economic impact and studies like HCV-TARGET, that include academic and community practices administering local standard of care treatment, can provide valuable reference data for prescribers, regulatory agencies, and the public on the effectiveness of HCV therapy for years to come. Ongoing data from HCV-TARGET will assess the efficacy of newer all oral HCV regimens and will be able to how to better manage a diverse patient population and how to improve access to therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of Data Coordinating Center at UNC Chapel Hill: Kenneth Bergquist, John Baron, Dianne Mattingly, Wendy Robertson, and Tiffany Marsh; the staff of Clinical Coordinating Center at UF Gainesville: Monika Vainorius, Lauren Morelli, Anthe Hoffman, Dona-Marie Mintz, Lasheaka McClellan, Angela Bauer, Patrick Horne, Rennie Mills, Amy Gunnett, Troy Chasteen, April Newsom, Jacob Harmer, Amanda Slater, Chante Taylor, Greg Riherd, and Karentan Robinson; the nurses and patients who were involved in this study; and Valérie Philippon, Ph.D. for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript, with funding from University of Florida.

Grant support: HCV-TARGET is an investigator-initiated study jointly sponsored by The University of Florida, Gainesville, FL (PI: Nelson), and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC (PI: Fried). It was funded in part by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck & Co., Kadmon Corporation, and Genentech and in part by CTSA UF UL1TR000064 and UNC 1UL1TR001111. Dr. Fried is funded in part by NIH Mid-Career Mentoring Award K24 DK066144.

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- DAA

direct acting antivirals

- PEG-IFN

peginterferon

- RGT

response-guided therapy

- PI

protease inhibitor

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Writing support: Medical writing and editing was provided by Valerie Philippon, PhD, with funding from the University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Declaration of interest: Richard K. Sterling has received research grants from AbbVie, Gilead, BMS, Merck, Vertex, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Roche/Genentech and has received honoraria for consulting from AbbVie, Gilead, Vertex, Roche/Genentech, Merck, Bayer, Salix, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Alexander Kuo has received research grants from AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, Roche/Genentech, Merck, and Vertex. Vinod K Rustgi has received grant/research support from Abbott Laboratories, Anadys Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; is a consultant for and has received honoraria from Genentech, Inc, Gilead Sciences, Inc, and Merck; and is on the advisory boards of Merck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and Tibotec. Mark S. Sulkowski has received funds for research support paid to Johns Hopkins University from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and Vertex and consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and Tobira. Thomas G. Stewart has nothing to disclose. Jonathan M. Fenkel has received honoraria for consulting from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Idenix, Janssen, and Vertex. Hisham El-Genaidi has nothing to disclose. Mitchell A. Mah’moud has received research grants from Roche/Genentech, Merck and Janssen and also honoraria for speaking or consulting from AbbVie, Merck and Salix. George M. Abraham has received research grants from Gilead, Merck, Vertex and Roche/Genentech and has received honoraria for consulting from AbbVie, Gilead, Vertex, Roche/Genentech, Merck and Kadmon. Paul W. Stewart has nothing to disclose Lucy Akushevich has nothing to disclose. David R Nelson has received grant/research support from Abbott, Achillion, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Kadmon, Genentech, Gilead, Merck, and Vertex. Michael W. Fried has received research grants from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Vertex and has received honoraria for speaking or consulting from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck, Vertex. Adrian M. Di Bisceglie serves on the advisory boards of Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pharmasset, Roche/Genentech, Salix, Tibotec, and Vertex, serves on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for Bayer, and has received grant and research support from Abbott, Anadys, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlobeImmune, Idenix, Pharmasset, Roche/Genentech, Transgene, Tibotec, and Vertex.

Authorship:

Guarantor of article: Richard K. Sterling

Specific author contributions: David R Nelson and Michael W. Fried obtained funding, designed and supervised the study, contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and manuscript preparation. Richard K. Sterling, Alexander Kuo, Vinod K Rustgi, Mark S. Sulkowski, Jonathan M. Fenkel, Hisham El-Genaidi, Mitchell A. Mah’moud, George M. Abraham, Adrian M. Di Bisceglie contributed to the data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript. Thomas G. Stewart, Paul W. Stewart and Lucy Akushevich performed statistical analysis, contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data, and to manuscript preparation. All authors approved the final draft of the manuscript, including the authors list.

References

- 1.Te HS, Jensen DM. Epidemiology of hepatitis B and C viruses: a global overview. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:1–21. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436–41. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rustgi VK. The epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:513–21. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:513–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherman KE, Flamm SL, Afdhal NH, et al. Response-guided telaprevir combination treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1014–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogawa E, Furusyo N, Nakamuta M, et al. Telaprevir-based triple therapy for chronic hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis: a prospective clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1076–85. doi: 10.1111/apt.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson IM, Marcellin P, Zeuzem S, et al. Refinement of stopping rules during treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1 infection with boceprevir and peginterferon/ribavirin. Hepatology. 2012;56:567–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.25865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramachandran P, Fraser A, Agarwal K, et al. UK consensus guidelines for the use of the protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:647–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.04992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George SL, Bacon BR, Brunt EM, Mihindukulasuriya KL, Hoffmann J, Di Bisceglie AM. Clinical, virologic, histologic, and biochemical outcomes after successful HCV therapy: a 5-year follow-up of 150 patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:729–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.22694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson DR, Davis GL, Jacobson I, et al. Hepatitis C virus: a critical appraisal of approaches to therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:397–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.016. quiz 366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcellin P, Boyer N, Gervais A, Martinot M, Pouteau M, Castelnau C, et al. Long-term histologic improvement and loss of detectable intrahepatic HCV RNA in patients with chronic hepatitis C and sustained response to interferon-alpha therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:875–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-10-199711150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruno S, Stroffolini T, Colombo M, et al. Sustained virological response to interferon-alpha is associated with improved outcome in HCV-related cirrhosis: a retrospective study. Hepatology. 2007;45:579–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberti A. Impact of a sustained virological response on the long-term outcome of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2011;31(Suppl 1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veldt BJ, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, et al. Sustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:677–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Cheung R, Mole LA. Comparative effectiveness of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir in a large U.S. cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:93–103. doi: 10.1111/apt.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butt AA, Kanwal F. Boceprevir and telaprevir in the management of hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:96–104. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxena V, Manos MM, Yee HS, et al. Telaprevir or boceprevir triple therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and varying severity of cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1213–24. doi: 10.1111/apt.12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fevery B, Susser S, Lenz O, et al. HCV RNA quantification with different assays: implications for protease-inhibitor-based response-guided therapy. Antivir Ther. 2014 Feb 28; doi: 10.3851/IMP2760. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermehren J, Aghemo A, Falconer K, et al. Clinical significance of residual viremia detected by two real-time PCR assays for response-guided therapy of HCV genotype 1 infection. J Hepatol. 2014;60:913–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.01.002. Epub 2014 Jan 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Jadhav P, Amur S, et al. Response guided telaprevir therapy in prior relapsers: The role of bridging data from treatment-naïve and experienced subjects. Hepatology. 2013;57:857–902. doi: 10.1002/hep.25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon SC, Muir AJ, Lim JK, et al. Safety Profile of Boceprevir and Telaprevir in Chronic Hepatitis C: Real-World Experience From HCV-TARGET. J Hepatol. 2014 Sep 9; doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.052. pii: S0168-8278(14)00647-3. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hézode C, Fontaine H, Dorival C, et al. Triple therapy in treatment-experienced patients with HCV-cirrhosis in a multicentre cohort of the French Early Access Programme (ANRS CO20-CUPIC) – NCT01514890. J Hepatol. 2013;59:434–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maasoumy B, Cobb B, Bremer B, et al. Detection of low HCV viraemia by repeated HCV RNA testing predicts treatment failure to triple therapy with telaprevir. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:85–92. doi: 10.1111/apt.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon SC, Yoshida EM, Lawitz EJ, et al. Adherence to assigned dosing regimen and sustained virological response among chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients treated with boceprevir plus peginterferon alfa-2b/ribavirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:16–27. doi: 10.1111/apt.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donepudi I, Parades A, Hubbard S, Awad C, Sterling RK. Utility of evaluating HCV in an Uninsured population. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2014:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.