Abstract

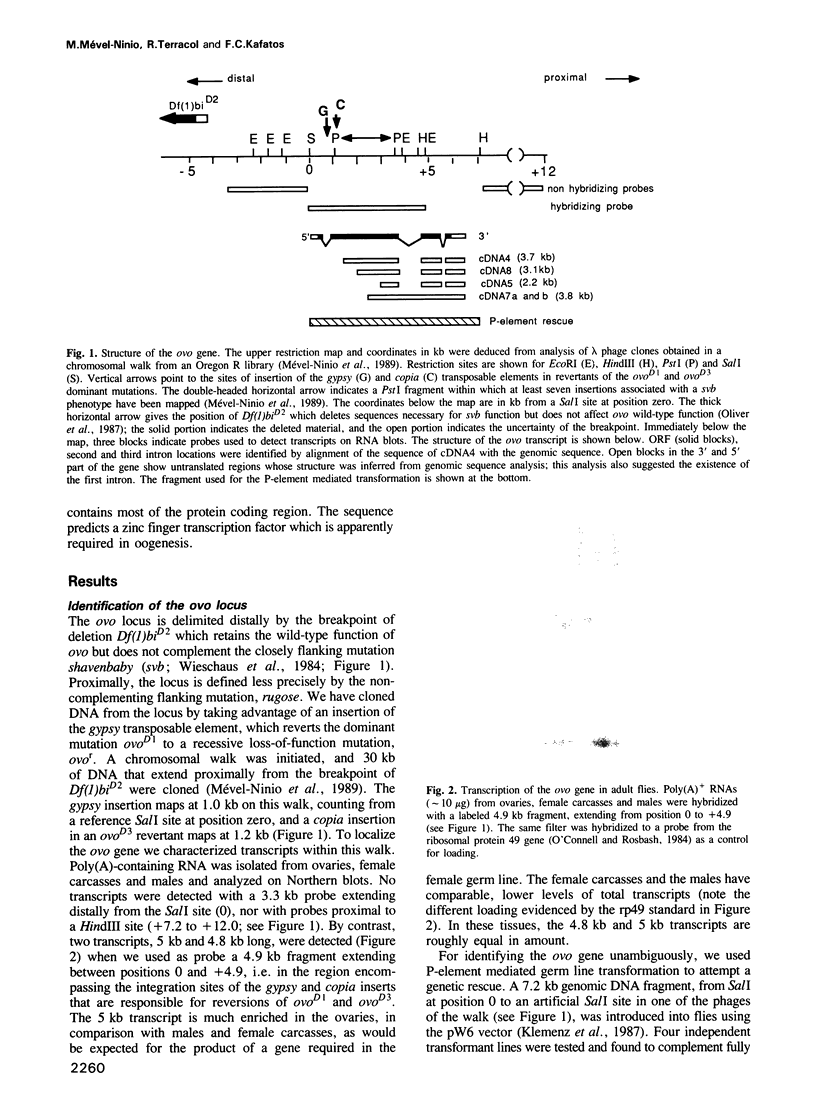

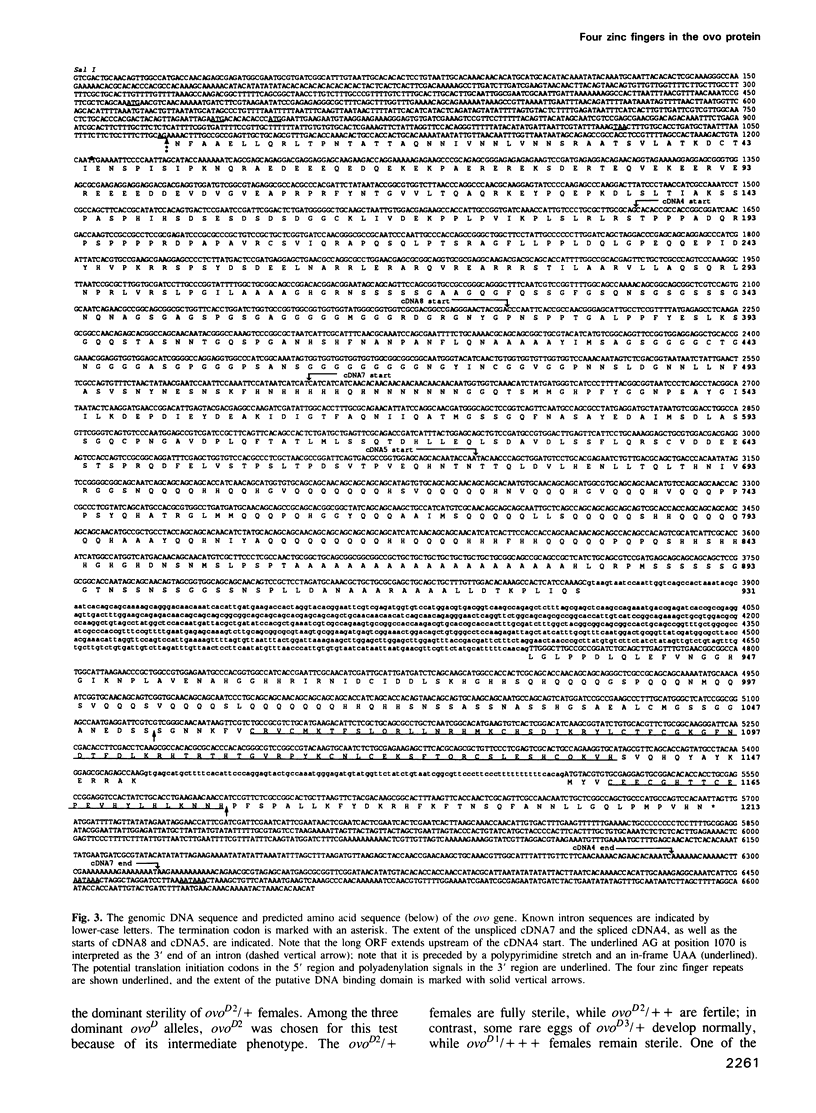

As defined by dominant and recessive ovo mutations, the ovo gene is required for development of the Drosophila female germ line, and does not exert any function in males or in somatic tissues. However, reversion of dominant ovo mutations can result in new phenotypes that are not related to the female germ line: the svb and lzl mutations affect cuticle and eye development, respectively. We have identified a 7.2 kb genomic fragment that rescues ovo mutations in transgenic Drosophila and thus contains all sequences necessary for ovo+ function. This fragment has been sequenced almost in its entirety, defining the ovo locus at the molecular level. Multiple copies of the same fragment also rescue the lzl mutation. They do not rescue svb mutations, in agreement with genetic evidence that the svb function requires additional, more distal sequences. Nevertheless, a number of transposable element insertions that induce a svb phenotype interrupt the coding sequence of ovo. Taken together, the genetic and molecular data indicate the existence of a complex locus, where the ovo and svb functions depend on overlapping coding sequences but distinct regulatory elements. The data also suggest a model for the lzl phenotype. Expression of ovo at the RNA level is detectable at stage 8 of oogenesis in nurse cells and persists through the rest of oogenesis and in early embryogenesis. The ovo transcript encodes a protein of at least 1209 amino acids with four zinc fingers, suggesting that ovo might be a transcription factor required for female germ line maintenance and gametogenesis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bellefroid E. J., Lecocq P. J., Benhida A., Poncelet D. A., Belayew A., Martial J. A. The human genome contains hundreds of genes coding for finger proteins of the Krüppel type. DNA. 1989 Jul-Aug;8(6):377–387. doi: 10.1089/dna.1.1989.8.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay J. L., Dennefeld C., Alberga A. The Drosophila developmental gene snail encodes a protein with nucleic acid binding fingers. 1987 Nov 26-Dec 2Nature. 330(6146):395–398. doi: 10.1038/330395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H., Kafatos F. C. Functional cDNA libraries from Drosophila embryos. J Mol Biol. 1988 Sep 20;203(2):425–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. H., King D. L., Wilcox M., Kafatos F. C. Developmentally regulated alternative splicing of Drosophila integrin PS2 alpha transcripts. Cell. 1989 Oct 6;59(1):185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90880-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busson D., Gans M., Komitopoulou K., Masson M. Genetic Analysis of Three Dominant Female-Sterile Mutations Located on the X Chromosome of DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER. Genetics. 1983 Oct;105(2):309–325. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.2.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener D. R. Comparison of the consensus sequence flanking translational start sites in Drosophila and vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Feb 25;15(4):1353–1361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.4.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury K., Deutsch U., Gruss P. A multigene family encoding several "finger" structures is present and differentially active in mammalian genomes. Cell. 1987 Mar 13;48(5):771–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline T. W. Two closely linked mutations in Drosophila melanogaster that are lethal to opposite sexes and interact with daughterless. Genetics. 1978 Dec;90(4):683–698. doi: 10.1093/genetics/90.4.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devereux J., Haeberli P., Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984 Jan 11;12(1 Pt 1):387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans M., Audit C., Masson M. Isolation and characterization of sex-linked female-sterile mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1975 Dec;81(4):683–704. doi: 10.1093/genetics/81.4.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gateff E. Cancer, genes, and development: the Drosophila case. Adv Cancer Res. 1982;37:33–74. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadonaga J. T., Carner K. R., Masiarz F. R., Tjian R. Isolation of cDNA encoding transcription factor Sp1 and functional analysis of the DNA binding domain. Cell. 1987 Dec 24;51(6):1079–1090. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemenz R., Weber U., Gehring W. J. The white gene as a marker in a new P-element vector for gene transfer in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 May 26;15(10):3947–3959. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.10.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani B. D., Lingappa J. R., Kafatos F. C. Temporal regulation in development: negative and positive cis regulators dictate the precise timing of expression of a Drosophila chorion gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 May;85(9):3029–3033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKearin D. M., Spradling A. C. bag-of-marbles: a Drosophila gene required to initiate both male and female gametogenesis. Genes Dev. 1990 Dec;4(12B):2242–2251. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. J., Tjian R. Transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells by sequence-specific DNA binding proteins. Science. 1989 Jul 28;245(4916):371–378. doi: 10.1126/science.2667136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler J. D. Developmental genetics of the Drosophila egg. I. Identification of 59 sex-linked cistrons with maternal effects on embryonic development. Genetics. 1977 Feb;85(2):259–272. doi: 10.1093/genetics/85.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses K., Ellis M. C., Rubin G. M. The glass gene encodes a zinc-finger protein required by Drosophila photoreceptor cells. Nature. 1989 Aug 17;340(6234):531–536. doi: 10.1038/340531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mével-Ninio M., Mariol M. C., Gans M. Mobilization of the gypsy and copia retrotransposons in Drosophila melanogaster induces reversion of the ovo dominant female-sterile mutations: molecular analysis of revertant alleles. EMBO J. 1989 May;8(5):1549–1558. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöthiger R., Jonglez M., Leuthold M., Meier-Gerschwiler P., Weber T. Sex determination in the germ line of Drosophila depends on genetic signals and inductive somatic factors. Development. 1989 Nov;107(3):505–518. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell P. O., Rosbash M. Sequence, structure, and codon preference of the Drosophila ribosomal protein 49 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984 Jul 11;12(13):5495–5513. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver B., Pauli D., Mahowald A. P. Genetic evidence that the ovo locus is involved in Drosophila germ line sex determination. Genetics. 1990 Jul;125(3):535–550. doi: 10.1093/genetics/125.3.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver B., Perrimon N., Mahowald A. P. Genetic evidence that the sans fille locus is involved in Drosophila sex determination. Genetics. 1988 Sep;120(1):159–171. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver B., Perrimon N., Mahowald A. P. The ovo locus is required for sex-specific germ line maintenance in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1987 Nov;1(9):913–923. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W. R., Lipman D. J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Apr;85(8):2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N. Clonal Analysis of Dominant Female-Sterile, Germline-Dependent Mutations in DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER. Genetics. 1984 Dec;108(4):927–939. doi: 10.1093/genetics/108.4.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M. How eukaryotic transcriptional activators work. Nature. 1988 Oct 20;335(6192):683–689. doi: 10.1038/335683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H. M., Preston C. R., Phillis R. W., Johnson-Schlitz D. M., Benz W. K., Engels W. R. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988 Mar;118(3):461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin G. M., Spradling A. C. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science. 1982 Oct 22;218(4570):348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro M. B., Senapathy P. RNA splice junctions of different classes of eukaryotes: sequence statistics and functional implications in gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987 Sep 11;15(17):7155–7174. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.17.7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea M. J., King D. L., Conboy M. J., Mariani B. D., Kafatos F. C. Proteins that bind to Drosophila chorion cis-regulatory elements: a new C2H2 zinc finger protein and a C2C2 steroid receptor-like component. Genes Dev. 1990 Jul;4(7):1128–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.7.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoller D., Friedel C., Schmid A., Bettler D., Lam L., Yedvobnick B. The Drosophila neurogenic locus mastermind encodes a nuclear protein unusually rich in amino acid homopolymers. Genes Dev. 1990 Oct;4(10):1688–1700. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. C., Rubin G. M. Transposition of cloned P elements into Drosophila germ line chromosomes. Science. 1982 Oct 22;218(4570):341–347. doi: 10.1126/science.6289435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky M. Sex determination in Drosophila: the X-chromosomal gene liz is required for Sxl activity. EMBO J. 1988 Dec 1;7(12):3889–3898. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D., Pfeifle C. A non-radioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989 Aug;98(2):81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E., Szabad J. The development and function of the female germ line in Drosophila melanogaster: a cell lineage study. Dev Biol. 1979 Jan;68(1):29–46. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]