Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) health care professionals recognize the need to motivate people with CF to adhere to nebulizer treatments, yet little is known about how best to achieve this. We aimed to produce motivational posters to support nebulizer adherence by using social marketing involving people with CF in the development of those posters.

Methods

The Sheffield CF multidisciplinary team produced preliminary ideas that were elaborated upon with semi-structured interviews among people with CF to explore barriers and facilitators to the use of nebulized therapy. Initial themes and poster designs were refined using an online focus group to finalize the poster designs.

Results

People with CF preferred aspirational posters describing what could be achieved through adherence in contrast to posters that highlighted the adverse consequences of nonadherence. A total of 14 posters were produced through this process.

Conclusion

People with CF can be engaged to develop promotional material to support adherence, providing a unique perspective differing from that of the CF multidisciplinary team. Further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of these posters to support nebulizer adherence.

Keywords: behavior change, social marketing, patient participation, nebulizers, medication adherence

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common life-shortening genetic condition in the UK, with a population of more than 10,000 affected people.1 Life expectancy for people with CF continues to improve,2 with an increasing array of CF treatments being introduced.3 Good adherence with CF treatments designed to maintain health is associated with better health outcomes and lower treatment costs.4 However, adherence with this form of treatment is generally poor, for example, a study among adults with CF found that median objective adherence with nebulized treatment is only 36%.5 Adherence is particularly challenging in CF due to the complex and time-consuming nature of effective treatments. Most adherence interventions for CF and other long-term conditions have also not been effective.6,7

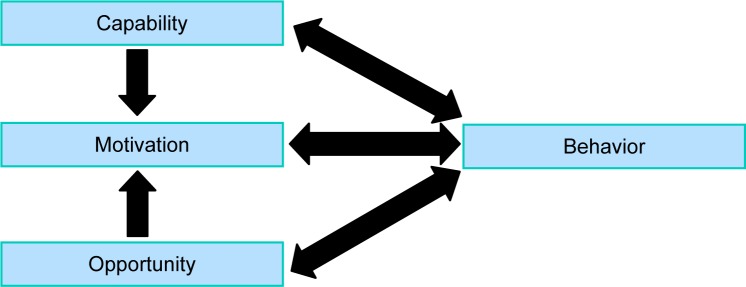

Adherence interventions are inherently complex, and the Medical Research Council Guidelines recommend that appropriate evidence and framework should be used to inform the development of a complex intervention.8 The Capability, Opportunity and Motivation (COM-B) model of behavior is a generic framework to understand human behavior, eg, medication adherence, and could assist in providing a theoretical underpinning to behavior change interventions.9 The COM-B model intends to be both parsimonious and comprehensive. The model hypothesizes that capability, opportunity, and motivation interact to produce behavior, which in turn can feedback to influence these initial components. The dynamic nature of this model is illustrated in Figure 1. The COM-B model can provide explanations for poor adherence. It can also act as a starting point in choosing interventions that are most likely to effectively address poor adherence.10 The motivation component within the COM-B model comprises “those brain processes that energize and direct behavior, not just goals and conscious decision making” but also “includes habitual processes, emotional responding, as well as analytical decision making”.9

Figure 1.

The Capability, Opportunity and Motivation (COM-B) model of behavior.

The motivational component to medication adherence can be further understood with the Necessity-Concerns Framework.11 Studies have shown that among intentional nonadherers, patients’ beliefs and perceptions about their treatment predict adherence.12,13 The Necessity-Concerns Framework operationalize the key beliefs that influence adherence into beliefs about the necessity of taking the medication and concerns about taking it.11

Social marketing has been shown to be effective in behavior change.14 It relies on commercial marketing techniques to influence behavior change by altering motivation toward that behavior.14 Successful social marketing depends on an understanding of the underlying motivations and characteristics of the target population.14 “Expert Patients Programme” is a Department of Health (DoH) initiative, which complements this approach by suggesting that involving patients in designing health care materials is important given their access to subjective expertise otherwise unobtainable to objective health professionals.15 A poster is a simple, yet effective, medium for displaying a message as part of a social marketing drive.16 Social marketing posters therefore provide a novel way to potentially improve adherence among people with CF.

The aim of this study was to produce a series of social marketing posters by using images and concepts refined through the utilization of “expert patients”, with the aim that in future the posters would result in increased adherence to treatment. Another explicit aim of the study was to use the process of poster development as a vehicle to carry out qualitative work exploring barriers and facilitators of adherence, specifically looking at intentional and unintentional nonadherence.

Methods

This study gained ethical approval from the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (ref: STH16267) and the Regional Ethical Committee (ref: 12/LO/1582). All participants provided written informed consent prior to taking part in the study. There were three stages of data collection.

Stage 1: Initial poster design based on literature and input from CF clinicians

Posters were initially designed based on prior literature on the barriers to adherence in CF.17–19 Designs were further developed using a focus group composed of the Sheffield Adult CF multidisciplinary team (MDT). The initial translation of what was reported in the literature into actual poster designs was made possible by accessing the experience and knowledge of experienced clinicians. Eighteen posters were created and taken to people with CF in the qualitative research phase. The posters aimed to motivate adherence by creating a discrepancy between a state of nonadherence and a better imagined future that would result from increased adherence. Participant involvement was split into two stages: the individual stage and the focus group stage.

Stage 2: Individual stage

The individual stage consisted of one-to-one sessions between a participant and an interviewer for a poster-scoring exercise and a semi-structured interview. For the poster-scoring task, participants were presented with each poster in a random order. Participants rated the posters on a linear scale from 0 (worst it could be) to 10 (best it could be) for three domains: the image, the text, and the overall impact. A semi-structured interview was then conducted to elicit participants’ opinions about the posters to further improve the design. A semi-structured interview design was used to obtain in-depth, high-quality data without subjecting participants to lengthy interviews, allowing the interviewer to guide the discussion while allowing participants the freedom to explore spontaneously emerging concepts.20 The topic guide for the semi-structured interview (Supplementary materials) was devised in consultation with the Sheffield Adult CF MDT.

Feedback from the individual stage was used to generate ideas and refine the initial posters to produce Stage 2 posters, including some posters that were completely new.

Stage 3: Focus group stage

Refined posters were then discussed in a focus group with quantitative scoring data allowing the omission of posters that were universally disliked by participants.

CF infection control guidelines make conventional face-to-face focus groups unfeasible. As online focus groups are a viable alternative,21 one was therefore conducted using the Cisco WebEx Meeting Centre for Internet Explorer Version 28.7.0.15458 (Cisco Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Participants were able to see the poster designs on their home computer while simultaneously discussing the posters via conference call. Feedback from the focus group was incorporated into the final Stage 3 poster designs. Topic guide for the focus group interview (Supplementary materials) was devised based on experience during the individual stage (Stage 2) and in consultation with the Sheffield Adult CF MDT.

Participants

All the participants recruited in this study were under the care of the Sheffield Adult CF Unit. Purposive sampling technique was performed, whereby participants for the individual stage were approached based on their nebulizer adherence to allow for a more representative sample. Adherence was calculated by comparing electronically recorded data from the participants’ adaptive aerosol dispenser device (I-neb®) with their agreed treatment regimen. This ensured an equal distribution of low (<25%), medium (25%–50%), and high adherers (>50%), ie, four participants for each adherence category. This categorization of adherence levels takes into account the median adherence with nebulized treatment of 36%.5 Recruitment continued until data saturation occurred (ie, no new major themes emerged from additional participants). A total of 12 participants undertook the individual stage of the study, out of the approached 36 people with CF. Of the 12 participants, eight were females, and the average age was 26.25 years (standard deviation [SD] =6.17). Two of the participants had completed secondary education (ie, achieved GCSE-equivalent qualifications), seven completed college (ie, A-level-equivalent qualifications), and three had attained degrees.

For the focus group, participants were not approached based on adherence profile, allowing users of any nebulizer type to participate. Participants were ineligible for the focus group if they had already completed the individual stage. Four participants were able to complete the focus group, concordant with previously recommended focus group size limits.22 Their average age was 33.75 years SD =5.74, and two of the participants were females. A participant had completed school, two completed college (ie, A-level-equivalent qualifications), and one received degree-level education. The focus group did not yield any new qualitative data that had not already emerged from the semi-structured one-to-one interviews; hence, only one focus group interview was conducted.

Data analysis

Qualitative data from the semi-structured interviews were analyzed using inductive content analysis.23 Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, before being read and listened to independently by authors SJ and NB. A ground-up approach was used, whereby the most common concepts emerging from the text were independently recorded and superordinated by SJ and NB. SJ and NB then collated their findings and organized these concepts into a coding manual. The coding manual was continuously updated throughout the process of analyzing subsequent transcripts through regular face-to-face discussion. This process was continued until the authors reached a consensus on the final thematic structure.

The focus group was again subjected to inductive content analysis23 by both SJ and NB independently before reaching an agreed consensus. Emergent themes from the focus group were used to update the thematic model and posters.

Results

Themes from participants’ feedback about factors associated with nebulizer adherence

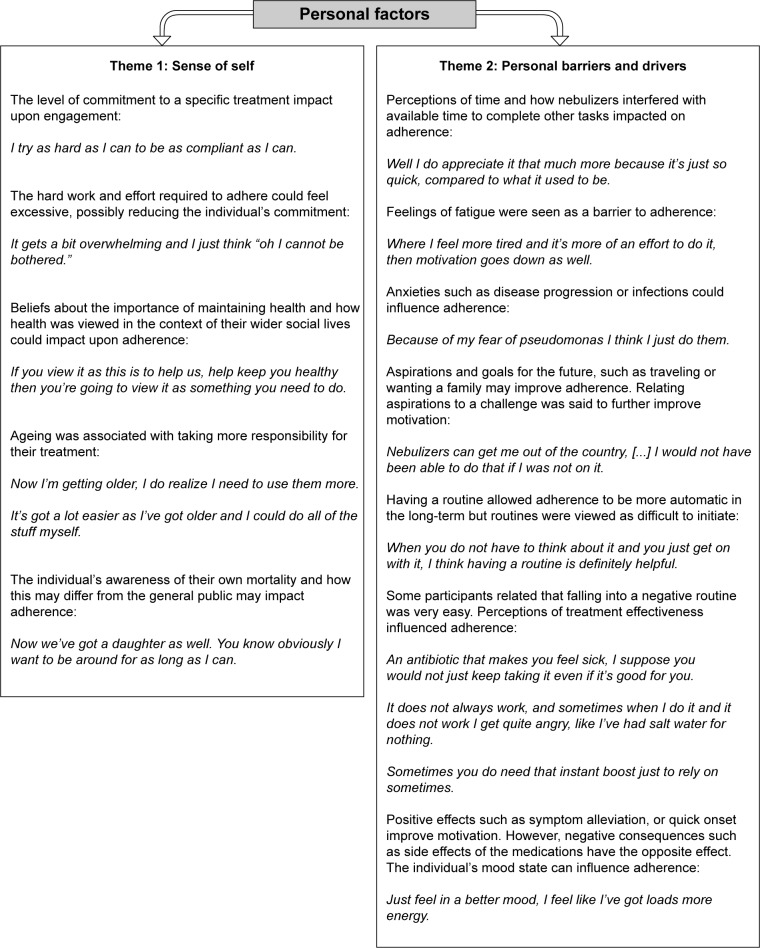

Two overarching factors derived from the semi-structured interviews were personal factors and relationships. These factors were reflected in the following six themes: sense of self, personal barriers and drivers, relationship with CF, relationship with family/friends, relationship with health care professionals, and relationship with wider society. These themes are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary of factors associated with nebulizer adherence.

Note: Direct quotes are in italics.

Abbreviation: CF, cystic fibrosis.

Development of social marketing posters

A key feedback from people with CF during Stage 2 (individual stage) resulted in a change to the standard prose contained on each poster. The original statements generated during Stage 1 (literature search and input from CF clinicians) were felt to be too long. The series of statements generated by people with CF during Stage 2 were more precise and more personal, eg, “reduce your need for hospital admissions”, “avoid intravenous antibiotics”, and “improve your lung function”.

Some participants expressed the desire for fact-based posters as they wanted “proof” that nebulizers work. This was not the case for everyone, however, with scenarios being preferable to facts for some participants. Participants stated the need for relatable and attainable concepts to be displayed on the posters.

Participants in general preferred messages that emphasized aspirations or the positives of adherence as opposed to consequences of nonadherence or messages that could be perceived as threatening. Messages illustrating this positivity are given in Table 1. Participants in particular liked the message that “prevention works”, which is felt to aid the consistency of the different posters.

Table 1.

Illustrative headlines universally liked by participants

| “Jake works full time, plays games with his mates, and finds time for his nebs” |

| “Jane works hard, plays hard … and she does her nebs” |

| “A matter of life and breath, using nebs … allows both” |

| “Wish you were here? Nebs could get you where you want to be” |

Note: All these headlines indicated how adherence could impact people’s lives.

In terms of design, participants preferred the posters with borders on each side. Curved lines or complex designs were said to detract from the message, hence avoided in the final poster design.

Participants stated that they would like the posters to be placed in clinical rooms. They also asked for personal copies in their homes to act as a consistent reminder.

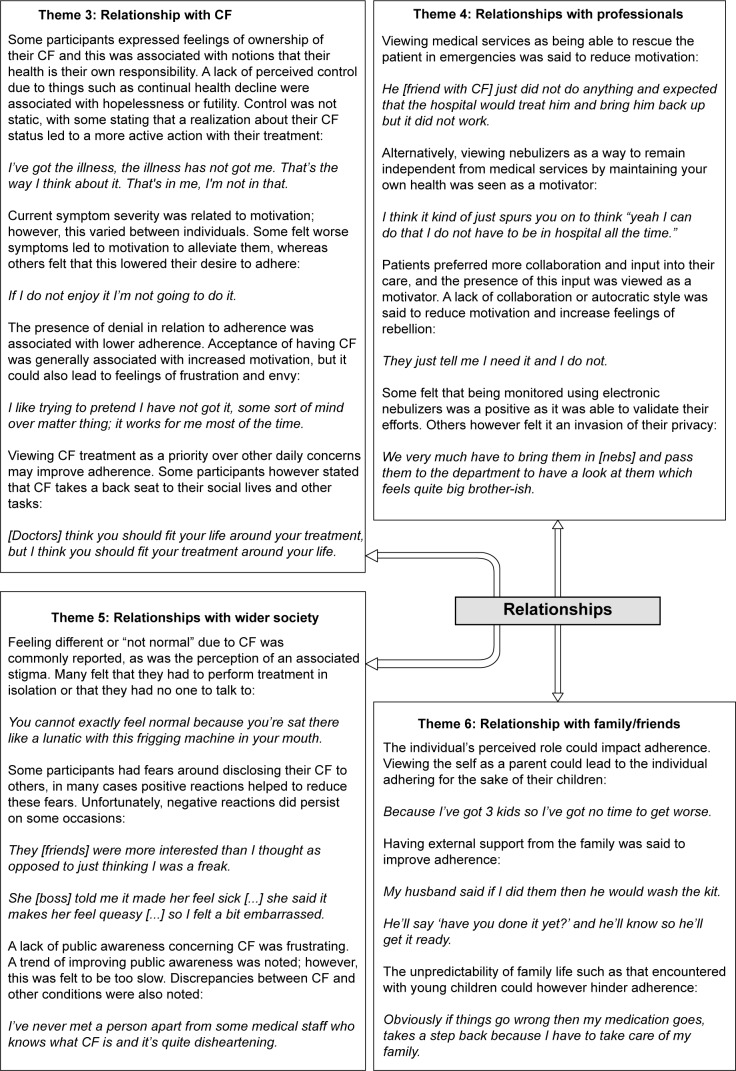

Ten of the most highly scored posters during Stage 2 (Figure 3) were then taken forward to Stage 3 (focus group stage) for the poster designs to be finalized.

Figure 3.

The ten highest scoring posters generated during Stage 2 (individual stage).

The focus group provided detailed feedback about poster design. Feedback supported concepts highlighted in the participant interviews during the individual stage (Stage 2). Respondents made it clear that posters highlighting that treatment offered a hopeful future were much more effective in motivating change than warning posters that highlighted the adverse consequences of nonadherence. Having realistic and attainable messages were said to be important in making the posters applicable to the CF population.

Some fresh posters were also generated based on the suggestions of the focus group.

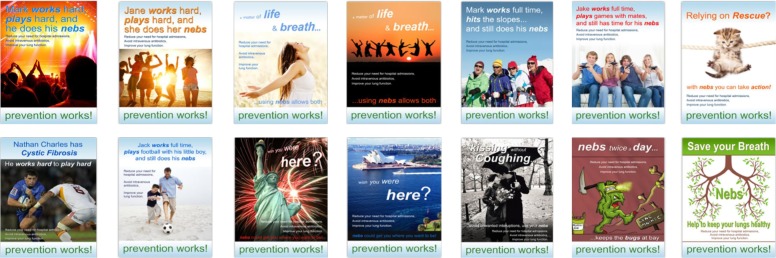

Feedback gained from people with CF during both the stages (individual stage and focus group stage) was collated and fed back to Phillips Respironics to produce the final posters. A total of 14 posters were produced (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Final poster designs created by Phillips Respironics Graphics department.

Discussion

The DoH Expert Patient document emphasizes that the subjective experience of people with long-term chronic health conditions can offer expertise, which may differ from health professionals.15 In order for social marketing approaches to be effective, the designers need to understand their target audience.14 By using semi-structured interviews and an online focus group, the present study engaged people with CF in the research process and was able to gain insight into their subjective experience. The data emerging from participants therefore informed concepts used in designing the poster, making it more relevant.

Participants with CF are unable to complete face-to-face focus groups because of the constraints mandated by infection control guidelines. An online focus group was therefore utilized. A previous study suggested that online focus groups offer data comparable to conventional face-to-face methods.21 We found that online focus group allowed an interactive discussion about the posters, and participants were able to discuss their own experiences of adherence and motivation, generating content-rich data. Coordinating the online focus group was straightforward, and the method was universally praised by participants. Advancements in software and the wide availability of the Internet have now made online focus groups relatively straightforward.

The two overarching factors influencing adherence that emerged from the qualitative analysis were personal factors and relationship. Two main themes were present within personal factors: the sense of self and personal barriers/drivers. The sense of self related to a person’s views and attitudes. The individual’s commitment to their treatment could influence how important staying healthy was to the individual, which in turn could impact the individual’s adherence in the face of a difficult treatment regimen. Barriers highlighted in previous studies such as other commitments, time pressure, fatigue, embarrassment, and views about treatment benefits17–19,24 were also found to be important to the people with CF in the current study who expressed that routine, perceived treatment effectiveness, emotions, anxieties, aspirations, and future goals could all influence nebulizer adherence. Four main themes were present within relationship factors: family relationships, relationships with health care professionals, relationships with wider society, and the personal relationship with CF. These are similar to the themes identified in another recent study looking at facilitators and barriers to adherence among adolescents with CF.24 It is known that burden of family responsibilities could actually lead to reduced adherence because of time pressure,24 but family responsibilities could also improve adherence by engendering a wish to stay well for others. Interaction with the CF MDT team were also recognized to impact on adherence, with relationships of trust-promoting adherence. If people with CF considered that the CF team could rescue them when they were not adhering, this could be associated with attitudes that acknowledged a decreased need for adherence. The style of engagement offered by the CF team influenced adherence. Participants preferred having a collaborative relationship allowing patient input into care. Participants’ relationships with wider society influenced the motivation to adhere. Some participants stated that they felt different from others in the society and that this could be accompanied by perceptions of stigma, leading to a wish to hide CF, which in turn might reduce a willingness to carry out treatment away from home. Some people with CF perceived that the awareness of CF in the general population was poor, which was seen as a cause of frustration by some people.

Themes generated from the qualitative data were incorporated into the posters. The concept of using posters as part of a social marketing approach addresses the motivation component of the COM-B model for improving adherence and changing behavior. These posters also promote discrepancy between the status quo and a better imagined future, to support people with CF to find their own reasons to change. This is consistent with the spirit of motivational interviewing (MI). MI is a technique suggested to increase the motivation of people with CF for treatment by encouraging people to make their own choices taking into account positive health behaviors and potential consequences, rather than simply telling them what they need to do.25 It is hoped that posters developed in this way would be particularly helpful in CF units setting out to use MI to promote adherence. As such, further research is needed to determine the efficacy of these social marketing posters to support adherence to treatment among people with CF.

Participants with CF in this study preferred the positive and supportive nature of posters that described an aspirational future rather than posters that described a future of adverse consequences resulting from nonadherence. Previous research has shown that framing information in terms of benefits (gain-framed appeal, which emphasizes the benefits of taking action) or detriments (loss-framed appeal, which emphasizes the costs of failing to take action) can have a substantial influence on the intended behavior. For a health behavior that is perceived to involve some risk of an unpleasant outcome, eg, for screening or detection of a health problem such as breast self-examination to detect early breast cancer, loss-framed appeal is more persuasive.26,27 In contrast, gain-framed appeal is more effective in promoting the use of “prevention behaviors”, eg, increasing physical activity to maintain health status.27,28 Adherence to medication is a prevention behavior to maintain health status; thus, the finding that people with CF preferred positive messages to promote adherence is congruent with previous research.

People with CF were enthusiastic in taking part in the design of posters to promote adherence. Participants in general preferred posters highlighting potential future advantages of adherence (gain-frame appeal), but found posters highlighting dire consequences of poor adherence (loss-frame appeal) to be discouraging. Posters that allow people with CF to capture their own reasons for adherence may support other efforts, eg, MI to improve adherence. The process of incorporating participants’ subjective expertise into the project allowed salient concepts to be captured in the poster content. Future research is now needed to evaluate the effectiveness of this social marketing approach to support adherence among people with CF.

Supplementary materials

Topic guide for the semi-structured interview

The research team estimate that this interview schedule would take around 1 hour to complete.

- As you saw in the ranking exercise we have developed posters that aim to motivate or encourage people to use their nebulizers regularly.

- Can you think of a time that you have lacked motivation to do something even though it needed to be done?

- What is it about this situation that you particularly remember?

- What was it about this situation that made you feel like this?

- Can you think of a time when you have been very motivated to do something?

- What is it about this situation that you particularly remember?

- If so, what was it about that situation that made you feel that way?

- How important do you feel motivation actually is?

- In improving peoples health and wellbeing?

- In improving your own health and wellbeing?

- What are your thoughts about nebulizers?

- How would you describe the nebulizers you use?

- How do you think others find them?

- How do you feel about the nebulizer you use?

- How do you feel about you your nebulizer plan?

- How do you feel about how often you are asked to use nebulizers?

- What impact do nebulizers have on your life?

- What impact do you think they may have on other people’s lives?

- How does using an I-neb differ from other nebulizers you may have used in the past?

- How does your nebulizer compare to your other treatments?

- Are there things that prevent you from using your nebulizer?

- What do you think may prevent other people from using nebulizers?

- Are there things that help you to use your nebulizer?

- What do you think may help other people to use their nebulizers?

- Did you have any thoughts about the posters you have seen today?

- Thinking more specifically about the posters you saw today, what were the main things that occurred to you when you saw them?

- Did any one in particular convey this to you?

- If yes, which one and why (please pick up poster if necessary)?

- How clear is it that they are about nebulizer use?

- Were there any posters in particular that were like this?

- If not clear, how could it be made clearer?

- What do you think about posters encouraging people to use their nebulizers?

- How successful do you think such posters would be in encouraging people to use their nebulizers?

- How likely would any of these posters be to improve your nebulizer use?

- How likely would any of these posters be to improve other people’s nebulizer use?

- Where would be the best place to put these posters?

- If you had the opportunity to design a poster to motivate you to use nebulizers what would your poster look like?

- Would you make any changes to any of the poster you have seen?

- Are there other methods that would be more effective?

Is there anything else that you would like to say about this project, the posters, or adherence in general?

Topic guide for the focus group interview

Welcome

Hi and welcome to this focus group. First of all let me thank you for taking the time to contribute to this research. My name is ___________ and I work as ______________. I will be running the focus-group today.

Before we get started I have a brief introduction to explain what this focus group is about and what it will involve.

As you may be aware the aim of this focus group is to discuss ideas relating to a poster campaign that has been developed. The posters relate to nebulized treatment and aim to encourage people to use their treatment.

The posters have been developed by both people with cystic fibrosis, and staff who work on the CF ward. Feedback we gained from these people has been used to refine and improve the posters.

We are now looking to gain some feedback from you to make some final adjustments to the posters before they are sent off for publishing.

Before we continue I would like to remind you of some of the expectations of a focus group in case you have not been in one before.

We would like you to be polite and respectful to other members of the focus group.

While we encourage discussion and debate, please do try to not talk over other people. Let people get out their points.

We will not tolerate any abusive or foul language directed at another in the group. If we judge people to be using this form of language they will be ejected from the group.

There are no right or wrong answers to these questions and we value everyone’s opinion.

Running order

During this focus-group we will show you a series of posters. We will first show you a set of posters and ask you to discuss and comment on their message.

For this we are interested in what you think about the message contained in the text, and how effective you feel it will be.

We will then ask you to separately comment on the image on the posters shown.

After you have commented on the main text and the images of the poster shown we will cycle onto the next set of posters and repeat the process. Asking you to first comment on the text and message and then the image.

We will keep repeating this until you have seen all of the posters.

Finally we will ask you for your comments on three types of poster design.

Possible general prompt questions

Message

What do you think about the message?

Does the message mean anything to you?

Do you think this message will be effective?

What do you think the aim of the message is?

What does the message make you think about?

Would you change anything about the message?

Is this better/worse than other messages?

Image

What do you think about the image?

Do you feel the image is effective?

Does the image match with the message/text

Would you change anything about the image?

What type of image would work better?

Is this better/worse than other images?

Work Hard Play Hard (slide 1)

The first concept we wish to show is Work Hard, Play Hard. What do you think about the message of these posters? Please do not comment on the image or the design, we will ask about that later. For now please try to only discuss the message.

Possible prompts – message

Do you think this is achievable?

Do you think this type of message is relatable?

What do you think about the message?

What do you think about making them gender specific?

Possible prompts – Image

Do you like the bright color?

What do you think about the images being silhouetted?

What do you think about the image focusing on one person?

Life and Breath (slide 2)

Thank you for that, we will now move on to the next set of posters – a matter of life and Breath.

Possible prompts – message

Is this message accurate?

Possible prompts – image

Do you prefer the image where you can see the person, or the silhouette?

Do you like the idea of their arms being spread?

What do you think about the images containing only one person?

Works full time (slide 3+4+5)

(Talk about the message on slides 3, 4, and 5 – then cycle back to talk about the image)

Possible prompts – message

Is this message attainable?

How do you feel about the length of the message?

How do these messages relate to you?

Possible prompts – image

How do you feel about the large groups?

Do the images relate to you?

Which of the four images do you like the most?

Wish you were here (slides 6+7)

Possible prompts message

What does this message mean to you?

Do you feel that this message is correct?

Possible prompts image

Which of these images do you prefer? Why?

Do you prefer the city-scapes or the other images?

How do you feel about there being no people in these images?

Do you prefer the night time images?

Bugs at bay/kissing without coughing – (slide 8)

This slide contains two posters which are not necessarily related. Please try to be clear about which poster you are referring to when commenting.

Possible prompts – messages

What do you think about these messages?

Is kissing without coughing meaningful to you?

Is “nebs twice a day” relevant to you?

Possible prompts – images

How do you feel about the image in black and white?

What do you think is happening in the cartoon picture/does the cartoon make sense?

What do you think about their being a cartoon?

Save your breath – waiting on rescue – (slide 9)

Possible prompts – message

Does the message (save your breath) feel like an instruction?

What do you think is meant by rescue?

Do you feel that it is right you could take action?

Possible prompts – image

What do you feel the tree represents?

What do you feel about there being no people in the images?

What do you think about their being an animal on the poster?

What do you think about the cat hanging from a rope?

Style – slide 10+11+12

In these next slides we are going to show you a number of poster styles. They will all be of the same message and contain the same image. In this section we only want you to comment on which designs you like and why. Please wait until I have shown you all of the designs before you make comment. I will scroll back to the other designs if you wish.

Possible prompts

Which design is your favorite?

Will certain designs fit better with different posters?

Can you think of any other designs?

How would you design a poster?

Finale

Is there anything else you would like to comment about these posters or the project in general?

Thank you for taking part in this focus-group, and we hope that you have enjoyed the experience.

We will be sending an email round again thanking you for your participation and it will include a copy of our contact details should you wish to make any further comments about the posters that you did not want to share in the group.

If you have any questions or would like to talk to someone about anything you have mentioned in this focus group, please do not hesitate to contact Steve Jones on the contact details he has provided.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This work was supported by a grant from the Burdett foundation and an unrestricted grant from Respironics who market the chipped I-Neb nebulizer. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1891–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoo ZH, Wildman MJ, Teare MD. Exploration of the impact of ‘mild phenotypes’ on median age at death in the U.K. CF registry. Respir Med. 2014;108(5):716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawicki GS, Ren CL, Konstan MW, Millar SJ, Pasta DJ, Quittner AL. Treatment complexity in cystic fibrosis: trends over time and associations with site-specific outcomes. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12(5):461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eakin MN, Riekert KA. The impact of medication adherence on lung health outcomes in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(6):687–691. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283659f45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels T, Goodacre L, Sutton C, Pollard K, Conway S, Peckham D. Accurate assessment of adherence: self-report and clinician report vs electronic monitoring of nebulizers. Chest. 2011;140(2):425–432. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glasscoe CA, Quittner AL. Psychological interventions for people with cystic fibrosis and their families. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD003148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003148.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785–795. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson C, Eliasson L, Barber N, Weinman J. Applying COM-B to medication adherence. Eur Health Psychologist. 2014;16(1):7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wroe AL. Intentional and unintentional nonadherence: a study of decision making. J Behav Med. 2002;25(4):355–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1015866415552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menckeberg TT, Bouvy ML, Bracke M, et al. Beliefs about medicines predict refill adherence to inhaled corticosteroids. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stead M, Gordon R, Angus K, McDermott L. A systematic review of social marketing effectiveness. Health Educ. 2007;107(2):126–191. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyreman S. The expert patient: outline of UK government paper. Med Health Care Philos. 2005;8(2):149–151. doi: 10.1007/s11019-005-2274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart R. The effects of a poster in informing and empowering patients in infection prevention and control. J Infect Prev. 2012;13(5):146–153. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bregnballe V, Schiotz PO, Boisen KA, Pressler T, Thastum M. Barriers to adherence in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis: a uestionnaire study in young patients and their parents. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:507–515. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S25308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Toole D, Latchford G, Duff A, et al. A qualitative study to explore factors that impact adherence to aerosol therapy in young people with CF: patient and parent perspectives. J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11(Suppl 1):S137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.George M, Rand-Giovannetti D, Eakin MN, Borrelli B, Zettler M, Riekert KA. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators: self-management decisions by older adolescents and adults with CF. J Cyst Fibros. 2010;9(6):425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–295. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox FE, Morris M, Rumsey N. Doing synchronous online focus groups with young people: methodological reflections. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(4):539–547. doi: 10.1177/1049732306298754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang KC, Davis A. Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Fam Pract. 1995;12(4):474–475. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Wildemuth BM. Qualitative analysis of content. In: Wildemuth BM, editor. Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited; 2009. pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawicki GS, Heller KS, Demars N, Robinson WM. Motivating adherence among adolescents with cystic fibrosis: youth and parent perspectives. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(2):127–136. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duff AJ, Latchford GJ. Motivational interviewing for adherence problems in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(3):211–220. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyerowitz BE, Chaiken S. The effect of message framing on breast self-examination attitudes, intentions, and behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(3):500–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman AJ, Bartels RD, Wlaschin J, Salovey P. The strategic use of gain- and loss-framed messages to promote healthy behavior: how theory can inform practice. J Commun. 2006;56(Suppl 1):S202–S220. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van ‘t Riet J, Ruiter RA, Werrij MQ, de Vries H. Investigating message-framing effects in the context of a tailored intervention promoting physical activity. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(2):343–354. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]