Abstract

The electric sense combines spatial aspects of vision and touch with temporal features of audition. Its accessible neural architecture shares similarities with mammalian sensory systems and allows for recordings from successive brain areas to test hypotheses about neural coding. Further, electrosensory stimuli encountered during prey capture, navigation, and communication, can be readily synthesized in the laboratory. These features enable analyses of the neural circuitry that reveal general principles of encoding and decoding, such as segregation of information into separate streams and neural response sparsification. A systems level understanding arises via linkage between cellular differentiation and network architecture, revealed by in vitro and in vivo analyses, while computational modeling reveals how single cell dynamics and connectivity shape the sparsification process.

Introduction

Peripheral sensory neurons typically encode a wide range of environmental stimuli. Moving more centrally, this dense coding is progressively replaced by a narrowing of neural responses to a subset of features of the whole stimulus ensemble [1–5]. Such sparse coding makes for easier read-out by downstream neurons, and is more energy efficient [6]. The mechanisms underlying sparsification are still elusive, and their elucidation is a fundamental goal of systems neuroscience. In particular, there is a quest for links between cellular/molecular properties – revealed through in vitro recordings – and network architecture and responses – revealed through in vivo and anatomical studies. Ideally the process would be understood for a behaving animal. Computational modeling has revealed that sparse coding requires nonlinear mechanisms in both the biophysical and network properties of sensory circuitry.

This review looks at the successive transformations of sensory input in the electrosensory system of weakly electric fish. This system has enabled major advances in understanding how differences in anatomy and cellular physiology underlie sparse coding. This is because links between in vitro and in vivo subthreshold and spiking dynamics are possible in the awake animal responding to a wide range of behaviorally relevant sensory input. The review is organized as follows. We first introduce the electrosensory system and its natural stimuli. We then review how electroreceptors can respond differentially to all these stimuli. Next, we describe the first order electrosensory target (hindbrain) emphasizing how linked cellular and architectural differentiation initiates the routing of these inputs into separate output streams. Finally, we summarize recent work on how an even sparser and more efficient representation of the stimulus ensemble is generated in the midbrain. Throughout, we highlight the dynamical and computational features of neural function that provide the substrate for the sparse code.

The electrosensory system

Gymnotiform wave-type weakly electric fish produce an electric field by repetitively discharging a specialized electric organ located in their tail (Figure 1a). This electric field is commonly referred to as the electric organ discharge (EOD). The EOD is sensed everywhere on the body as a transdermal potential difference. Perturbations of the EOD, caused by nearby objects with conductivity different than that of the surrounding water (e.g. prey, conspecifics), modify the transdermal potential difference from its baseline value in a spatially dependent fashion that is commonly referred to as the electric image (Figure 1a). Computational studies have explained the detailed spatio-temporal structure of electric images caused by small objects (e.g. prey), self-generated movement (e.g. tail bends) [7], as well as spatially diffuse images caused by conspecifics [8]. Further, they have predicted important characteristics such as spatial resolution [9].

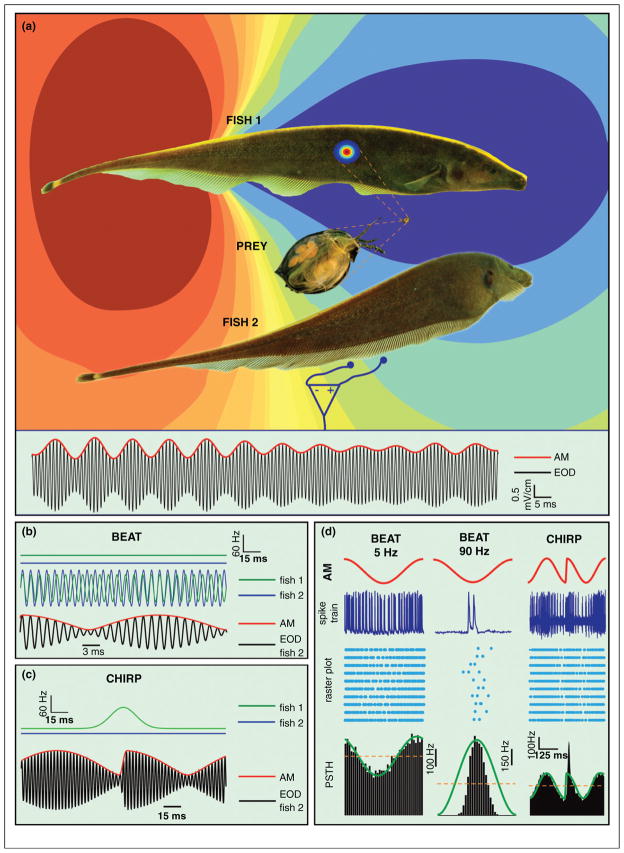

Figure 1. Spatio-temporal content of electrosensory signals varies based on the behavioral context.

(a) Images of Apteronotus leptorhynchus (brown ghost knife fish). The electric field generated by Fish 1’s electric organ discharge (EOD) varies sinusoidally in time at a constant high frequency (species range: ~650–1000 Hz) and is seen at the peak of its head negative phase. A prey distorts the EOD to create an ‘electric image’ on the skin. A conspecific (Fish 2) also generates an EOD (not shown) that interferes with fish 1’s EOD. A small dipole and amplifier placed near the skin of Fish 2 shows the electrical signal (black) from both fish as indicated in the trace at the bottom. Also shown is time varying amplitude of the signal (red). (b) When two fish with different EOD frequencies (upper traces) are located close to one another, the EODs of each fish (middle traces) show alternating regions of constructive and destructive interference, which leads to a sinusoidal amplitude modulation (SAM, red) or a beat with frequency equal to the difference of the individual fish’s EOD frequencies (lower trace) for the summed signal (black). (c) Weakly electric fish can emit communication signals known as chirps that consist of a transient increase in its EOD frequency (upper traces) when close to a conspecific. As a result, the SAM frequency increases transiently which leads to a phase reset of the beat (lower traces). (d) Electroreceptor afferents respond differentially to time varying AMs characteristic of beats and chirps. For low (~5 Hz) frequencies, the afferent’s baseline firing rate is smoothly modulated by the beat (left panel) and in excellent agreement with the response predicted from a linear system. For high (~90 Hz) frequencies, afferents display nonlinear phase locking (middle panel) in that the afferent only fires near a preferred phase of the SAM; this is quite different than what would be predicted from a linear system (green line). For chirps, the resulting phase reset of the beat is a high frequency stimulus that causes a greater transient increase in firing rate than expected from a linear prediction (green line) as seen in the PSTH. This translates to a transient synchronization at the population level.

Scattered on the skin surface are electroreceptors that monitor the transdermal potential difference. While P-type electroreceptors respond to amplitude modulations (AMs) of the EOD, T-type electroreceptors respond instead to frequency modulations [10] while ampullary electroreceptors respond to exogenous (non-EOD) electric signals. Here we consider exclusively P-type electroreceptors and their downstream neurons, and henceforth refer to P-type electroreceptors as ‘electroreceptors’.

Electrosensory stimuli

EOD AM’s can arise in multiple behaviorally relevant situations. Prey objects give rise to spatially localized AMs that contain low temporal frequencies (Figure 1a) [11]. Self-generated AMs through body movements can induce spatially diffuse low frequency AMs that interfere with prey detection, but covering the entire body surface [10,12]. Weakly electric fish are often found in groups of 2–4 individuals [13]; the interference between the EODs of two neighboring fish causes a sinusoidal AM (‘SAM’) beat pattern at temporal frequencies 0–400 Hz [14] (Figure 1b). Moreover, brief (10–30 ms) increases in EOD frequency known as ‘chirps’ are used as communication signals, and transiently perturb the beat pattern (Figure 1c) [14].

Electroreceptors and coding of natural sensory input

Electroreceptors in A. leptorhynchus (~15,000 total) are phase locked to the EOD and discharge at rates of 100–500 spikes/s in a highly variable but patterned manner when the EOD is unperturbed [15]. The baseline discharges of individual electroreceptors are uncorrelated, allowing them to act as independent coding channels [16]. Patterning in the spontaneous discharge is characterized by a long interspike interval (ISI) following on average by a short ISI and vice versa [16–18] and is caused by spike frequency adaptation [19,20]. This patterning enables a dense but efficient representation of the natural stimulus ensemble. Indeed, it leads to reduced variability and better transmission of low (<20 Hz) frequency signals [21–24,25••] (see [23] for review) in an almost linear fashion through changes in firing rate (Figure 1d). Further, this patterning enables nonlinear phase locking and synchronization in response to high (>50 Hz) frequency SAMs. Chirp stimuli can cause transient synchronization or desynchronization of the electroreceptor population depending on the genders of interacting fish [26,27]. Electroreceptors respond similarly to self and externally generated AMs independently of their spatial extent as long as they have the same temporal structure [12,28].

The electrosensory lateral line lobe: efficient circuits for feature extraction and sparse coding

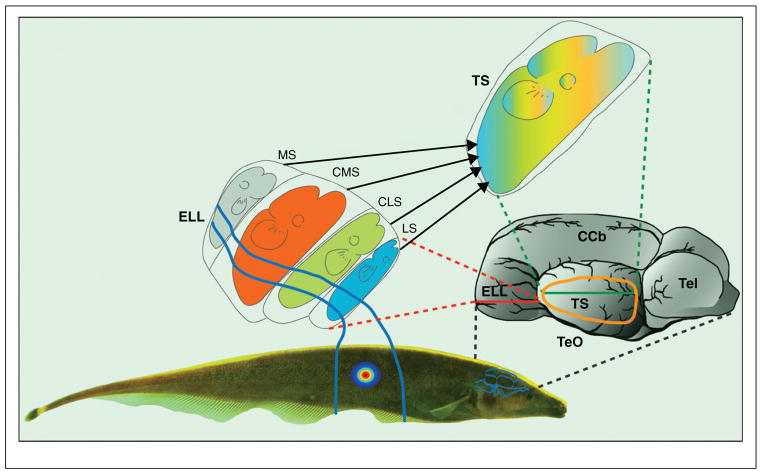

Electroreceptors project to the electrosensory lateral line lobe (ELL). Each afferent trifurcates and synapses onto pyramidal cells within three structurally similar parallel segments: centromedial (CMS), centrolateral (CLS) and lateral (LS) [29–33]. Ampullary electroreceptors project to the medial segment (MS) and are not considered here (Figure 2). All three segments thus receive identical input and each forms an entire topographic map of the animal’s body surface. The output from pyramidal cells from all maps converges onto the midbrain torus semicircularis (TS) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Anatomy of the electrosensory system.

The image at the right is a side view of the A. leptorhynchus brain with rostral to the right. The key electrosensory structures are the hypertrophied electrosensory lateral line lobe (ELL) within the rhombencephalon and torus semicircularis (TS) within the mesencephalon. The outline of the TS is indicated by the orange ovoid, but this structure is actually located interior to the external optic tectum (TeO). A horizontal slice through the ELL is shown near the middle of the figure. Electroreceptor afferents project only to the ipsilateral ELL where they form four parallel topographic maps, each within its own ELL segment. For each map, the head of the fish is represented rostrally in ELL, while the trunk is represented caudally. The dorso-ventral axis of the fish is represented along the medio-lateral axis of each map. The four segments are: medial (MS), centromedial (CMS), centrolateral (CLS) and lateral (LS). Passive electroreceptors project strictly to MS (not further considered). Each active electroreceptor afferent trifurcates to provide identical input to the CMS, CLS and LS maps. However, as indicated in this figure, the sizes of the maps are very different with CMS > CLS > LS. All four ELL maps converge onto the midbrain TS. Thus, the TS contains a single topographic map of the entire body surface. CCb – corpus cerebellum; Tel – telencephalon.

ELL circuitry: on and off center cells and columnar organization

The ELL has a characteristic layered organization and is organized in columns with all cells in a column receiving identical afferent input [34,35•]. Our description will center on the main output ELL neurons, pyramidal cells, which fall into two major classes, E and I, corresponding to On and Off center cells in the visual system [36–38]. This E/I dichotomy is a major architectural feature for sparse neural coding by having E and I-cells respond selectively to input caused by conductors (e.g. prey) and dielectric (e.g. rocks) objects, respectively. E and I-cells also preferentially respond to chirps associated with same and opposite-sex interactions, respectively [39•,40••].

Functional heterogeneities in pyramidal cells

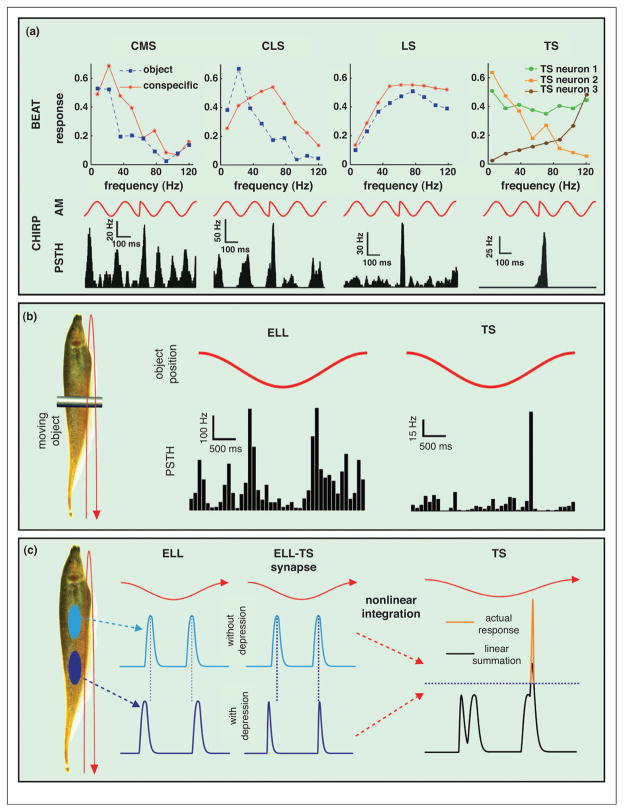

There are large heterogeneities amongst pyramidal cells of a given type: superficial pyramidal cells receive strong feedback, deep pyramidal cells do not [41]. Superficial cells encode input more selectively and nonlinearly than deep cells and electroreceptors [28,42,43]: they are tuned to a narrower temporal frequency range that can depend on the stimulus’ spatial extent (i.e. object vs. conspecific) (Figure 3a). Further, superficial pyramidal cells do not respond to self-generated AMs and can adapt to changes in such AMs through synaptic plasticity [10]. In contrast, like electroreceptors, deep cells responses are largely insensitive on the stimulus’ spatial extent and have broad frequency tuning curves [28,42,44]. Further, they display little or no plasticity compared to superficial cells [45]. We describe below the intrinsic and network-based mechanisms that mediate these functional heterogeneities.

Figure 3. Emergence of sparse coding in the hindbrain and further specialization in midbrain.

(a) (Top) Tuning curves from example pyramidal neurons from the CMS (left), CLS (middle), LS (right), and TS (far right) under spatially localized (mimicking an object, blue) and spatially diffuse (mimicking a conspecific, red) stimulation. While CMS neurons tend to be tuned to low (<20 Hz) frequencies under both stimulation geometries, CLS neurons tend to switch their tuning contingent on stimulation geometry. LS neurons are tuned instead to higher (~80 Hz) frequencies. TS neurons display large heterogeneities in their tuning: some neurons are tuned to low frequencies, others display more broadband tuning while others are tuned to high frequencies. The differential tuning across the ELL segments is manifested in the responses to small chirps (bottom). Indeed, LS neurons show the strongest response while CMS shows the weakest. Some TS neurons respond selectively to chirps. (b) Left: Schematic showing an object (metal bar) moving back and forth sinusoidally along the animal’s rostro-caudal axis. Right: Example responses from ELL (left) and TS (right) neurons to a moving object. ELL neurons strongly respond when the object is at a given position along the animal independently of movement direction. By contrast, TS neurons display directional selectivity and can respond only when the object moves in a given direction. (c) The mechanism by which TS neurons acquire directional selectivity involves combining the responses of two ELL neurons (blue and cyan) whose receptive fields are located at different positions along the animal’s body. The ELL neurons will respond at different phases of the object’s movement in a directionally independent fashion, thereby creating a time delay between their responses. However, differential filtering alters the output of one ELL neuron through high-pass filtering (dark blue) but does not affect the other (cyan), which can reduce the time delay is one direction and increase it in the other. This causes a greater overlap between the ELL neuron responses and thus a greater depolarization in the preferred movement direction and less overlap and depolarization in the other direction. The increased depolarization in the preferred direction can then activate subthreshold T-type calcium channels that then further increase the response in the head-to-tail but not in the tail-to-head direction (orange), thereby explaining the directionally selective responses in TS neurons.

Feedback determines functional heterogeneities in ELL

The ELL projects topographically to two contralateral regions: the nucleus praeminentialis (nP, rhombencephalon – feedback) and the torus semicircularis (TS, midbrain – ascending projections). A striking feature of the electrosensory system is that only the deep pyramidal cells project to nP whereas all project to TS [45]. NP mediates direct inhibitory and excitatory feedback to the ELL, as well as indirect feedback to ELL via cerebellar granule cells (EGp).

The excitatory component of the direct feedback may mediate a sensory ‘searchlight’, but this is not further considered here [32]. Further, the diffuse inhibitory component of a direct feedback of nP to ELL enables ‘categorical’ coding that is dependent on the stimulus’ spatial extent. Indeed, conspecific-like AMs elicit ELL gamma range oscillatory bursting whereas prey-like AMs do not [46]. A combination of experimental, computational, and theoretical studies have shown that this is because this feedback system exhibits a resonance, which is excited in proportion to the degree of spatial correlation in the stimulus [46,47]. The oscillatory bursting may enhance directionally selective responses to object movement in the TS [48].

A consequence of the anatomical/molecular arrangement of the indirect feedback is that superficial cells reject global spatially redundant low frequency input that can be caused by self-movement, using a ‘teacher’ input from deep cells that is not altered by feedback [45]. Experimental [28,45] and theoretical [49] studies have revealed how this feedback reduces the system’s response to low frequencies in an adaptive manner via burst dependent LTD [45,50].

Across-map differences: intrinsic and network mechanisms lead to differential frequency tuning

Pyramidal cells within all three maps display differential temporal frequency tuning [43,51]. CMS cells are tuned to lower frequencies, and LS cells to higher frequencies (Figure 3d). CLS cells can switch their tuning depending on the stimulus’ spatial extent [52]. Recent studies have shed light on the mechanisms mediating these differences in frequency tuning. Receptive fields of CMS are small, but those of LS cells are significantly larger (160–360 mm2) [34]. As such, CMS cells display better spatial resolution than LS cells. This combined with a higher spike threshold makes LS cells respond preferentially to synchronous electroreceptor input evoked by high frequency spatially diffuse stimuli (e.g. communication) (Figure 3a) [39•,40••,53]. By contrast, CMS cells will respond preferentially to spatially localized low frequency input (e.g. prey) (Figure 3a).

All pyramidal cells display burst firing that results from somatodendritic interactions [54–56]. A somatic action potential backpropagates to the dendrite and causes a dendritic action potential that in turn propagates back to the soma and causes a depolarizing after-potential (DAP) leading to another somatic action potential. The DAP size grows throughout the burst thereby leading to shorter interspike intervals. The burst terminates when the inter-spike interval is below the dendritic refractory period [57]. The functional role of burst firing in pyramidal cells is not fully understood as these bursts can sometimes code for low frequency AMs in CMS and CLS cells [44,58] although isolated spikes can also perform this function [59]. Recent studies have shown that these bursts most probably signal the presence of specific features and contain little information in their structure [44,60]. SK channels in LS E-cells cause an AHP that opposes burst firing by cancelling the DAP [61]. This AHP can be overcome during chirp stimulation that thus gives rise to burst firing in these cells [39•]. Burst firing is extensively regulated by various mechanisms including neuromodulators such as serotonin [62•] and acetylcholine [63,64]. Burst firing is thus most probably used under particular behavioral contexts in order to signal specific stimulus features.

In summary, ELL pyramidal cells begin segregating electroreceptor input into ethologically relevant features related to navigation, predation and communication, and self-movement. To do so, they use a combination of intrinsic and network mechanisms that take advantage partly of the fact that electroreceptors respond differentially to different stimulus classes.

Feature selectivity in the electrosensory midbrain (TS)

The separation of electrocommunication and electrolocation channels has been nearly completed in TS. Indeed, TS neurons generally respond to a much narrower range of spatiotemporal frequencies than ELL pyramidal cells [65–67]. Some are tuned to low frequencies, others to mid-range or even high frequencies (Figure 3a). In addition, some TS neurons respond selectively to communication stimuli [68] (Figure 3a).

Moreover, TS neurons also respond selectively to objects (Figure 3b). Indeed, perception of directional motion is also an important function in weakly electric fish [69] and directional selectivity has recently been shown to be an emergent property in TS [70,71•] (Figure 3b) and is summarized in Figure 3c. Although ELL pyramidal cells are not directionally selective, cells with receptive fields at different positions along the fish’s body respond at different phases of the movement, creating a delay between their responses (Figure 3e). Moreover, ELL-TS synapses display differential degrees of synaptic depression along the animal’s body [71•]. High-pass filtering caused by synaptic depression can counteract the aforementioned delay, but only in one direction of movement, creating a directional bias. Nonlinear integration via T-type calcium channels further increases this bias [72•] (Figure 3c). Ongoing studies are focusing on the role of intrinsic and network mechanisms in the further sparsification of TS responses.

Summary

Through a combination of intrinsic and network properties, electrosensory circuitry progressively segregates inputs of varying temporal and spatial scales encountered in different behavioral contexts. This results in the creation of separate neural streams for electrolocation and electrocommunication. Experimental and computational work have revealed general principles of sparse coding that can be summarized as follows:

Electroreceptors use different strategies to encode different temporal frequencies. They implement noise reduction via negative interval correlations. They respond similarly to self vs. externally generated stimuli and are not tuned to spatial frequency.

Within the ELL, ON and OFF center-like cells provide a first step in sparsification by segregating responses to dielectric vs. conductive objects in the environment.

Parallel maps in ELL receive the same electroreceptor input and segregate information according to temporal and spatial frequency content. These differences are partly due to intrinsic (e.g. SK channels) and network (e.g. receptive field) mechanisms.

Within each ELL map, feedback pathways are used to make some pyramidal cells reject redundant stimuli in an adaptive fashion, and make them respond selectively to stimuli caused by conspecifics. The feedback input originates from a subgroup of dense coding deep pyramidal cells with receptor-like tuning properties and is used to make another subgroup of superficial pyramidal cells code more sparsely. Further, a dendritic backpropagation-based bursting mechanism allows superficial cells to respond preferentially to specific stimuli.

Further sparsification occurs in midbrain TS neurons with a near complete separation of responses to electrolocation and electrocommunication stimuli. Further, TS neurons acquire directional selectivity to moving objects by nonlinearly summing differentially filtered inputs from non-directionally selective ELL neurons.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by CIHR (M.J.C., A.L., L.M.), NSERC (M.J.C., A.L.), CFI (M.J.C.), and CRC (M.J.C.). The funders had no role in either study design, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript.

We would like to dedicate this review to Joseph Bastian, a friend, colleague, mentor, and pioneer in research on the electrosensory system.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Barlow HB. Single Units and sensation: a neuron doctrine for perceptual psychology. Perception. 1972;1:371–394. doi: 10.1068/p010371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rolls ET, Tovee MJ. Sparseness of the neuronal representation of stimuli in the primate temporal visual cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:713–726. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quiroga RQ, Reddy L, Kreiman G, Koch C, Fried I. Invariant visual representation by single neurons in the human brain [see comment] Nature. 2005;435:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/nature03687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez-Orive J, Mazor O, Turner GC, Cassenaer S, Wilson RI, Laurent G. Oscillations and sparsening of odor representations in the mushroom body. Science. 2002;297:359–365. doi: 10.1126/science.1070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olshausen BA, Field DJ. Sparse coding of sensory inputs. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, House JL, Krahe R, Nelson ME. Modeling signal and background components of electrosensory scenes. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol. 2005;191:331–345. doi: 10.1007/s00359-004-0587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly M, Babineau D, Longtin A, Lewis JE. Electric field interactions in pairs of electric fish: modeling and mimicking naturalistic input. Biol Cybern. 2008;98:479–490. doi: 10.1007/s00422-008-0218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babineau D, Lewis JE, Longtin A. Spatial acuity and prey detection in weakly electric fish. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bastian J. Plasticity in an electrosensory system. I. General features of a dynamic sensory filter. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2483–2496. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson ME, MacIver MA. Prey capture in the weakly electric fish Apteronotus albifrons: sensory acquisition strategies and electrosensory consequences. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:1195–1203. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.10.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bastian J. Plasticity of feedback inputs in the apteronotid electrosensory system. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:1327–1337. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamper SA, Carrera GE, Tan EW, Fugere V, Krahe R, Fortune ES. Species differences in group size and electrosensory interference in weakly electric fishes: implications for electrosensory processing. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hupe GJ, Lewis JE. Electrocommunication signals in free swimming brown ghost knifefish, Apteronotus leptorhynchus. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:1657–1667. doi: 10.1242/jeb.013516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gussin D, Benda J, Maler L. Limits of linear rate coding of dynamic stimuli by electroreceptor afferents. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2917–2929. doi: 10.1152/jn.01243.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chacron MJ, Maler L, Bastian J. Electroreceptor neuron dynamics shape information transmission. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:673–678. doi: 10.1038/nn1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratnam R, Nelson ME. Non-renewal statistics of electrosensory afferent spike trains: implications for the detection of weak sensory signals. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6672–6683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06672.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chacron MJ, Longtin A, St-Hilaire M, Maler L. Suprathreshold stochastic firing dynamics with memory in P-type electroreceptors. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;85:1576–1579. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chacron MJ, Pakdaman K, Longtin A. Interspike interval correlations, memory, adaptation, and refractoriness in a leaky integrate-and-fire model with threshold fatigue. Neural Comput. 2003;15:253–278. doi: 10.1162/089976603762552915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benda J, Maler L, Longtin A. Linear versus nonlinear signal transmission in neuron models with adaptation currents or dynamic thresholds. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:2806–2820. doi: 10.1152/jn.00240.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chacron MJ, Longtin A, Maler L. Negative interspike interval correlations increase the neuronal capacity for encoding time-varying stimuli. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5328–5343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05328.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chacron MJ, Lindner B, Longtin A, Maler L, Bastian J. Experimental and Theoretical demonstration of noise shaping by interspike interval correlations. Proc SPIE. 2005;5841:150–163. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avila Akerberg O, Chacron MJ. Nonrenewal spike train statistics: causes and consequences on neural coding. Exp Brain Res. 2011;210:353–371. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2553-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longtin A, Laing C, Chacron MJ. Correlations and memory in neurodynamical systems. In: Rangarajan G, Ding M, editors. Long-Range Dependent Stochastic Processes. Springer; 2003. pp. 286–308. [Google Scholar]

- 25••.Nesse W, Maler L, Longtin A. Biophysical information representation in temporally correlated spike trains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21973–21978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008587107. This paper was inspired by the electroreceptor negative ISI correlations as well as by [35•]. It showed that the state of the adaptation process generating negative correlations itself contains information about the sensory input. It further demonstrated that a suitably matched postsynaptic process could extract this information and therefore implement rapid very weak signal detection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benda J, Longtin A, Maler L. Spike-frequency adaptation separates transient communication signals from background oscillations. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2312–2321. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4795-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benda J, Longtin A, Maler L. A synchronization-desynchronization code for natural communication signals. Neuron. 2006;52:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chacron MJ, Maler L, Bastian J. Feedback and feedforward control of frequency tuning to naturalistic stimuli. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5521–5532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0445-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berman NJ, Maler L. Inhibition evoked from primary afferents in the electrosensory lateral line lobe of the weakly electric fish (Apteronotus leptorhynchus) J Neurophysiol. 1998a;80:3173–3196. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berman NJ, Maler L. Interaction of GABAB-mediated inhibition with voltage-gated currents of pyramidal cells: computational mechanism of a sensory searchlight. J Neurophysiol. 1998b;80:3197–3213. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berman NJ, Maler L. Distal versus proximal inhibitory shaping of feedback excitation in the electrosensory lateral line lobe: implications for sensory filtering. J Neurophysiol. 1998c;80:3214–3232. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berman NJ, Maler L. Neural architecture of the electrosensory lateral line lobe: adaptations for coincidence detection, a sensory searchlight and frequency-dependent adaptive filtering. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:1243–1253. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.10.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shumway C. Multiple electrosensory maps in the medulla of weakly electric Gymnotiform fish. II. Anatomical differences. J Neurosci. 1989;9:4400–4415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-12-04400.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maler L. Receptive field organization across multiple electrosensory maps. I. Columnar organization and estimation of receptive field size. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516:376–393. doi: 10.1002/cne.22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Maler L. Receptive field organization across multiple electrosensory maps. II. Computational analysis of the effects of receptive field size on prey localization. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516:394–422. doi: 10.1002/cne.22120. This paper is one of the few that applied Fisher Information methods to estimate the physiological requirements for detection of weak signals. In this case very realistic estimates of the E cell receptive field dimensions across the ELL topographic maps were used for the computational analysis. The Fisher Information analysis also incorporated detailed physiological data, and concluded that rate coding might not be sufficient for the detection of weak prey signals. This conclusion further inspired the theoretical analysis of [25••] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders J, Bastian J. The physiology and morphology of two classes of electrosensory neurons in the weakly electric fish Apteronotus Leptorhynchus. J Comp Physiol A. 1984;154:199–209. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maler L, Sas EK, Rogers J. The cytology of the posterior lateral line lobe of high frequency weakly electric fish (Gymnotidae): differentiation and synaptic specificity in a simple cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1981;195:87–139. doi: 10.1002/cne.901950107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maler L. The posterior lateral line lobe of certain gymnotiform fish. Quantitative light microscopy. J Comp Neurol. 1979;183:323–363. doi: 10.1002/cne.901830208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Marsat G, Proville RD, Maler L. Transient signals trigger synchronous bursts in an identified population of neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:714–723. doi: 10.1152/jn.91366.2008. This paper demonstrated that superficial E cells of the lateral ELL segment (LS) were exquisitely sensitive to chirps occuring during same sex interactions and responded to them by emitting spike bursts. Burst firing is in general suppressed by an SK channel mediated AHP except during the chirp. This illustrates how a core burst mechanism due to back-propagating dendritic spikes can be modulated at a molecular level (SK channels) to change a neuron’s coding properties. As described in [62•], more subtle regulation of sensory responsiveness can then be generated by molecular machinery that modulates the SK-mediated AHP via 5-HT receptors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40••.Marsat G, Maler L. Neural heterogeneity and efficient population codes for communication signals. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:2543–2555. doi: 10.1152/jn.00256.2010. This paper demonstrated that a type of chirp used in courtship could be discriminated by the firing patterns of ELL I cells. A key point of this paper was the in vivo demonstration that cellular heterogeneity across I cells was essential for their differential response, and therefore for the ability of the I cell population to discriminate many chirps that occur during opposite sex interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bastian J, Nguyenkim J. Dendritic Modulation of Burst-like firing in sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:10–22. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chacron MJ. Nonlinear information processing in a model sensory system. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:2933–2946. doi: 10.1152/jn.01296.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krahe R, Bastian J, Chacron MJ. Temporal processing across multiple topographic maps in the electrosensory system. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:852–867. doi: 10.1152/jn.90300.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avila Akerberg O, Krahe R, Chacron MJ. Neural heterogeneities and stimulus properties affect burst coding in vivo. Neuroscience. 2010;168:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bastian J, Chacron MJ, Maler L. Plastic and non-plastic cells perform unique roles in a network capable of adaptive redundancy reduction. Neuron. 2004;41:767–779. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doiron B, Chacron MJ, Maler L, Longtin A, Bastian J. Inhibitory feedback required for network oscillatory responses to communication but not prey stimuli. Nature. 2003;421:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature01360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doiron B, Lindner B, Longtin A, Maler L, Bastian J. Oscillatory activity in electrosensory neurons increases with the spatial correlation of the stochastic input stimulus. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:048101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.048101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramcharitar JU, Tan EW, Fortune ES. Global electrosensory oscillations enhance directional responses of midbrain neurons in eigenmannia. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2319–2326. doi: 10.1152/jn.00311.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chacron MJ, Longtin A, Maler L. Delayed excitatory and inhibitory feedback shape neural information transmission. Phys Rev E. 2005;72:051917. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.051917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bol K, Marsat G, Harvey-Girard E, Longtin A, Maler L. Frequency-tuned cerebellar channels and burst-induced LTD lead to the cancellation of redundant sensory inputs. J Neurosci. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0193-11.2011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shumway C. Multiple electrosensory maps in the medulla of weakly electric Gymnotiform fish. I. Physiological differences. J Neurosci. 1989;9:4388–4399. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-12-04388.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chacron MJ, Doiron B, Maler L, Longtin A, Bastian J. Non-classical receptive field mediates switch in a sensory neuron’s frequency tuning. Nature. 2003;423:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature01590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehaffey WH, Maler L, Turner RW. Intrinsic frequency tuning in ELL pyramidal cells varies across electrosensory maps. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2641–2655. doi: 10.1152/jn.00028.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doiron B, Laing C, Longtin A, Maler L. Ghostbursting: a novel neuronal burst mechanism. J Comput Neurosci. 2002;12:5–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1014921628797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez FR, Mehaffey WH, Turner RW. Dendritic Na+ current inactivation can increase cell excitability by delaying a somatic depolarizing afterpotential. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3836–3848. doi: 10.1152/jn.00653.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner RW, Maler L, Deerinck T, Levinson SR, Ellisman MH. TTX-sensitive dendritic sodium channels underlie oscillatory discharge in a vertebrate sensory neuron. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6453–6471. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06453.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lemon N, Turner RW. Conditional spike backpropagation generates burst discharge in a sensory neuron. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1519–1530. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oswald AMM, Chacron MJ, Doiron B, Bastian J, Maler L. Parallel processing of sensory input by bursts and isolated spikes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4351–4362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0459-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Middleton JW, Yu N, Longtin A, Maler L. Routing the flow of sensory signals using plastic responses to bursts and isolated spikes: experiment and theory. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2461–2473. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4672-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avila Akerberg O, Chacron MJ. In vivo conditions influence the coding of stimulus features by bursts of action potentials. J Comput Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10827-011-0313-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ellis LD, Mehaffey WH, Harvey-Girard E, Turner RW, Maler L, Dunn RJ. SK channels provide a novel mechanism for the control of frequency tuning in electrosensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9491–9502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1106-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62•.Deemyad T, Maler L, Chacron MJ. Inhibition of SK and M channel mediated currents by 5-HT enables parallel processing by bursts and isolated spikes. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:1276–1294. doi: 10.1152/jn.00792.2010. The first paper to explore the functional role of 5-HT in the ELL. The authors show that 5-HT promotes burst firing through downregulation of the AHP, thereby making the cells more responsive to a wide range of stimuli. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ellis LD, Krahe R, Bourque CW, Dunn RJ, Chacron MJ. Muscarinic receptors control frequency tuning through the downregulation of an A-type potassium current. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:1526–1537. doi: 10.1152/jn.00564.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mehaffey WH, Ellis LD, Krahe R, Dunn RJ, Chacron MJ. Ionic and neuromodulatory regulation of burst discharge controls frequency tuning. J Physiol (Paris) 2008;102:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rose GJ, Fortune ES. New techniques for making whole-cell recordings from CNS neurons in vivo. Neurosci Res. 1996;26:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(96)01074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rose GJ, Fortune ES. Frequency-dependent PSP depression contributes to low-pass temporal filtering in Eigenmannia. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7629–7639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07629.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fortune ES, Rose G. Passive and active membrane properties contribute to the temporal filtering properties of midbrain neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3815–3825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03815.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vonderschen K, Chacron MJ. Sparse coding of natural communication signals in midbrain neurons. Biomed Cent Neurosci. 2009;10:O3. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cowan NJ, Fortune ES. The critical role of locomotion mechanics in decoding sensory systems. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1123–1128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4198-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bastian J. Electrolocation II. The effects of moving objects and other electrical stimuli on the activities of two categories of posterior lateral line lobe cells in Apteronotus albifrons. J Comp Physiol A. 1981;144:481–494. [Google Scholar]

- 71•.Chacron MJ, Toporikova N, Fortune ES. Differences in the time course of short-term depression across receptive fields are correlated with directional selectivity in electrosensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:3270–3279. doi: 10.1152/jn.00645.2009. The first paper showing that the time constants of synaptic depression vary depending on the stimulus’ location along the animal’s body, thereby creating a directional bias that is exploited by midbrain electrosensory neurons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72•.Chacron MJ, Fortune ES. Subthreshold membrane conductances enhance directional selectivity in vertebrate sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:449–462. doi: 10.1152/jn.01113.2009. The first study showing that subthreshold T-type can act as the necessary nonlinear integrator in order to generate directional selectivity in midbrain neurons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]