Abstract

Mother-infant vocal interactions serve multiple functions in child development, but the community-common or community-specific nature of key features of their vocal interactions remains unclear. Here we examined rates, interrelations, and contingencies of vocal interactions in 684 mothers and their 5-month-old infants in diverse communities in 11 countries (Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Cameroon, France, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, South Korea, and United States). Rates of mothers’ and infants’ vocalizations varied widely across communities and were uncorrelated. However, collapsing across communities mothers vocalized to infants contingent on the offset of their infants’ nondistress vocalizing, infants vocalized contingent on the offset of their mothers’ vocalizing, and maternal and infant contingencies were significantly correlated, pointing to the beginnings of dyadic conversational turn taking. Despite broad differences in the overall talkativeness of mothers and infants, maternal and infant contingent vocal responsiveness is common across communities, supporting essential functions of turn-taking in early child socialization.

The consequence of parent-child interaction for children’s emotional, social, cognitive, and language development has long been recognized by developmental theorists (Bowlby, 1982; Stern, 1985; Trevarthen, 1979; Vygotsky, 1981), and contingent responsiveness is an especially salient almost universal parenting practice, providing infants with experiences that support their development and effectance (Bornstein, 1989a, 2015). More specifically, vocal interactions are special in early development. Nondistress vocalizations constitute a salient infant signal, and language is a primary response mode of mothers, thus reinforcing the prominence of mother-infant vocal interchanges (Bornstein et al. 1992; Hsu & Fogel, 2003; Kärtner et al., 2008; Van Egeren, Barratt, & Roach, 2001). “Conversational” turn-taking (which is what mutually contingent vocal exchanges are) is requisite for successful verbal communication and serves as a basis for the acquisition of language and social interaction (Snow, 1977; Stern, 1985).

When humans talk to one another, they normally and ubiquitously engage in conversation, continuous and habitually nonsimultaneous exchanges in which speakers take turns. One person speaks at a time, and a second person begins in the space which follows the first person finishing. Turn-taking in conversation, which was first systematically deconstructed by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974; see also Wilson, Wiemann, & Zimmerman, 1984), is a fulcrum in the infrastructure and organization of dialogue. Turn-taking involves highly coordinated timing, the cyclical rise and fall in the probability of initiating speech during brief silences, and is essentially resource-free and automatic (Wilson & Wilson, 2005). Several arguments support a universal system for turn-taking that follows a “minimal-gap minimal-overlap” norm (Schegloff, 2006). The functional basis for conversational turns to be immediately adjacent (rather than overlapping or separated) makes clear the link between speakers’ utterances (Schegloff, 1968), ensures that the response is directly contingent on the preceding utterance (Gergely, Nádasdy, Csibra, & Biró, 1995), and reveals how the prior utterance was understood (Sacks, 1963; Sacks et al., 1974; Schegloff, Jefferson, & Sacks, 1977).

To date, most studies of mother-infant vocal exchanges have been conducted on samples collected in the United States and Northern Europe (Gros-Louis, West, Goldstein, & King, 2006; Tomlinson, Bornstein, Marlow, & Swartz, 2014; Van Egeren et al., 2001), and the few exceptions that have collected data elsewhere (East Asia and Africa, notably) have employed methods and samples not comparable in breadth or depth with them. Nonetheless, it is widely believed that mother-infant vocal turn taking may be so common as to be “universal”, where in actuality the degree to which mother-infant “conversations” follow mutually contingent patterns across a broad range of communities and languages is unknown. If mothers and young infants respond contingently to one another’s vocalizations generally, turn taking might be an early developing and community-common phenomenon and speak to a universal mechanism by which infants experience and acquire linguistic and pragmatic skills. Furthermore, turn-taking systems organize all sorts of very different activities; for example, language exchanges might establish a primary way in which social interactions more generally are organized. By contrast, if contingent mother-infant vocal communication is not consistent across diverse communities, then turn-taking will be a later developing and likely community-specific phenomenon and raise questions about how experiential factors regulate vocal and verbal as well as social interactions of mothers and their prelinguistic infants.

Although ethnographic and sociolinguistic evidence has been read as support that different communities hold some contrasting beliefs about human development, social interaction, and verbal communication (Dixon, Keefer, Tronick, & Brazelton, 1982; Ochs, 1988; Richman, Miller, & LeVine, 1992; Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986), we expected that mother-infant vocal interactions would respect universal rules of turn-taking. We arrived at this hypothesis after considering developmental, neurobiological, and cross-linguistic arguments. First, nonverbal turn-taking “proto-conversations” between newborns and caregivers are well documented and thought to constitute a universal “format” for very early joint activity (e.g., Crown, Feldstein, Jasnow, Beebe, & Jaffe, 2002; Holmlund, 1995; Jasnow & Feldstein, 1986; Kaye, 1982; Lavelli & Fogel, 2005; Masataka, 1993; Papoušek, Papoušek, & Bornstein, 1985; Rutter & Durkin, 1987; Stern, 1985; Stevenson, Ver Hoeve, Roach, & Leavitt, 1986; Striano, Henning, & Stahl, 2006). Mothers and babies regularly follow some behaviors (including vocalizations) by suppressing their own behavior, thereby permitting their partner to join in. From an extremely early age infants vocalize different sounds, and their caregivers respond to different infant vocalizations in structured patterns of turn-taking (Gros-Louis et al., 2006; Van Egeren et al., 2001). This developmental perspective led us to expect conversational turn-taking might be common in mothers and babies.

Even if some forms of “proto-” and actual conversational interactions between mothers and infants are universal in human societies (Keller, Schölmerich, & Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1988), rates of conversational turn-taking might still be shaped by local conventions. Lafayette, IN, European American mothers speak in response to their infants’ vocalizations more than Nagoya Japanese mothers (Fogel, Toda, & Kawai, 1988), Bostonian, MA, mothers are more verbally responsive to their infants than West Kenyan Gusii mothers (Richman et al., 1992), and urban Berliner mothers show higher levels of contingent vocal responsiveness than rural Cameroonian Nso mothers (Keller, Kärtner, Borke, Yovski, & Kleis, 2005). This perspective on the literature led us to expect community variation in the overall levels of contingent vocal responsiveness.

Second, the human nervous system appears to be wired for dialogue (i.e., adjacent sequences of communication and response; Garrod & Pickering, 2004) and does not cope well with producing and perceiving speech simultaneously because of interference from masking, diverted attention, or disrupted information processing. Under many such challenging acoustic conditions, speakers modify their speech (Aubanel, Cooke, Villegas, & Lecumberri, 2011; Carhart, Tillman, & Greetis, 1969; Lombard, 1911). Even background conversation disrupts foreground conversation. Thus, delay, interruption, or elimination of auditory feedback undermines speech fluency (Black, 1951; Cowie, Douglas-Cowie, & Kerr, 1982; Fukawa, Yoshioka, Ozawa, & Yoshida, 1988; Geers et al., 2003; Howell & Powell, 1987; Mackay, 1968; Schauwers et al., 2004; Siegel, Schork, Pick, & Garber, 1982), and, reciprocally, speech production modulates activity in brain regions involved in speech perception (Zheng, Munhall, & Johnsrude, 2009). Sidnell (2001) argued that turn-taking in conversation constitutes a species-specific biological adaptation, and Wilson and Wilson (2005) proposed that, during conversation, endogenous oscillators in the brains of the speaker and the listener become mutually entrained to engage one another more effectively. Thus, nervous system information processing considerations led us to expect that turn-taking in conversation would be common.

Third, turn-taking may be a rule of language (Caspers, 1998; de Ruiter, Mitterer, & Enfield, 2006; Hafez, 1991; Kjaerbeck, 1998; La France, 1974; Lerner & Takagi, 1999; Murata, 1994; Robbins, Devoe, & Wiener, 1978; Sacks et al., 1974; Sidnell, 2001; Streeck, 1996; Tanaka, 1999, 2000a, 2000b). Stivers et al. (2009) examined 10 major world languages drawn from traditional indigenous communities in an attempt to uncover shared underlying foundations in turn-taking. Speakers of all 10 languages similarly avoided overlap in conversation and minimized silence between conversational turns, pointing to robust human universals and a single shared architecture for language use. Even when the physical substrate of conversation differs radically from that of ordinary speech, as in nonverbal sign languages used by the deaf (Coates & Sutton-Spence, 2001; Mesch, 2000, 2001), turn-taking is systemic and widespread (Langford, 1994). As Wilson and Wilson (2005, p. 958) concluded, “To our knowledge, no culture or group has been found in which the fundamental features of turn-taking are absent.” This cross-linguistic consideration further fueled our expectations that mother-infant conversations would follow turn-taking.

To explore the community-common or -specific nature of mutually contingent mother-infant vocalizations and vocal interactions directly, we sampled speech in mother-infant dyads from communities in one country in North America (United States), two in South America (Argentina, Brazil), three in Europe (Belgium, France, Italy), two in Africa (Cameroon, Kenya), one in the Middle East (Israel), and two in East Asia (Japan, South Korea). We chose to study mothers and infants from communities in different regions and countries of the world because such comparative designs are requisite to understanding community-common versus community-specific influences in caregiving and child development (Norenzayan & Heine, 2005). Our main aim was to explore whether mother-infant dialogues in different communities exhibit central shared features of turn-taking (and if they did not to uncover community-specific manifestations).

In this study, therefore, we investigate, first, mean levels in and, second, correlations of rates of mother and infant vocalization. Analyses of mean levels across communities provide information about base rates of vocalization, and correlations provide information about associations between partners’ raw rates of vocalization. It is widely acknowledged that mothers in some ethnic groups and cultures are more verbal than others. For example, Konner (1977) recorded variations in the frequencies of caregiver vocalization to infants across samples drawn from the Kalahari San, Guatemala, and Boston working and middle class, and Richman et al. (1988) reported that North American, Swedish, and Italian mothers had higher rates of vocalization than Kenyan Gusii mothers. U.S. American mothers talk more to their babies than Japanese mothers (Caudill & Weinstein, 1969; Chew, 1969; Ferguson, 1977). Indeed, many observers have noted the relative dearth of speech used by African caregivers, be they Gusii of Kenya or native speakers of Sooninke or Pular from West Africa (Dixon, Tronick, Keefer, & Brazelton, 1981; Rabain-Jamin, 1994; Richman et al., 1988). Likewise, babies in some ethnic groups and cultures are more vocal than others; U.S. American infants vocalize nondistress more than Japanese infants (Bornstein, 1989b; Caudill & Weinstein, 1969).

In addition to these familiar statistical techniques, third, we analyzed timed event sequences of mother and infant vocalizations specifically to examine turn-taking. Sequential analyses provide information about interactional processes that underpin mother-infant exchanges by describing patterns of interaction in real time. Sequential analyses are more faithful (than, for example, correlations among rates of behaviors) to a dynamic approach that explains the behavior of each interlocutor by evaluating contingencies between partners (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997; Bakeman & Quera, 2011). Most research that has examined sequences of mother-infant interactions has used time-sampling coding techniques and looked at sequences of mother and infant behaviors without regard to the timing of those behaviors (event sequences), or has coded durations, without regard to how long it takes the partner to respond and thus become involved in the interaction (state sequences). In contrast, we examine contingency of timed sequences of mother and infant vocalizations at a microanalytic level. This approach permits more fine-grained assessments of turn-taking in mother-infant vocal interactions. Compared to event or state sequences, timed event sequences better capture the complexity and dynamic of real-life interactions because they preserve onset and offset times in partners’ speech (Bakeman & Quera, 2011). Timed event sequential data can answer research questions such as how likely is the infant to respond to the conclusion of his/her mother’s vocalization by vocalizing within a specified time window. Thus, timed sequential analysis complements and enriches standard statistical techniques and offers a dynamic process-oriented method to the study of mother-infant interactions that more closely approximates causal inference (Bakeman & Gnisci, 2005). Although mothers are often thought to lead infants in interactions because they are the more mature partner in the dyad (Kochanska & Aksan, 2004; Maccoby, 1992; Vygotsky, 1978), developmental scientists recognize the influence that infants themselves exert in mother-infant interactions, and mother-infant relationships more generally, and so in their own development (Bell, 1979; Bornstein, 2015). Therefore, our analysis of sequences incorporated a within-dyad factor that allowed us to determine which partner was more responsive – mother to infant or infant to mother (Fogel, 1982; Gottman & Ringland, 1981).

In brief, we investigated the following research questions: (i) Do communities (i.e., different countries) differ, or are they similar, in rates of mothers’ vocalizations to infants and rates of infants’ nondistress vocalizations? (ii) Are rates of mother and infant vocalization correlated, and are patterns of correlations similar or different across communities? (iii) Are mother vocalizations and infant vocalizations universally contingent, or does their contingency vary across communities? (iv) Do mothers who speak with a high degree of contingency to their infants have infants who vocalize with a high degree of contingency to their mothers, or are mother-infant vocal contingencies uncoordinated? (v) Do mothers or infants tend to be more vocally responsive, and are communities similar or different in the relative vocal responsiveness of each partner? As the focus of this paper is on community similarities and differences, analyses that address these five questions controlled for the potential impact of infant age and gender and maternal age and education as needed. In a nutshell, there are many claims in the developmental literature for community similarity and difference in rates of mother and infant vocalization, their correlation, and their contingency, but no adequately broad-ranging, microanalytic, quantitative comparison such as we undertake here has been made.

Method

Participants

To investigate these questions, we recruited 684 mothers and their 5½-month-old infants from distinct communities in 11 countries. Dyads were drawn from more than one socioeconomic and demographic subgroup in each country whenever possible so that country samples would be heterogeneous and broader generalizations could be drawn. In this report, we use the term “community” to refer to our country samples generically; our samples came from different countries, but we do not claim that these samples are representative of their respective nation states. We attempted to collect 50 to 100 families in each community, but some samples were smaller because of recruitment considerations. Argentine mother-infant dyads (n = 99) were recruited from greater metropolitan Buenos Aires (67% of the sample) and a rural community in Córdoba Province (33%). Belgian dyads (n = 100) were recruited from Ghent and Antwerp. Brazilian dyads (n = 58) were recruited from metropolitan Rio de Janiero. Cameroonian dyads (n = 29) were Nso, an indigenous group that lives in northwest Cameroon. French dyads (n = 49) were recruited from Paris and its immediate banlieux. Israeli dyads (n = 30) were recruited from metropolitan Haifa. Italian dyads (n = 92) were recruited from metropolitan Padua (55%), a northern city, and in and around Ruoti (45%), a southern town. Japanese dyads (n = 49) were recruited from greater metropolitan Tokyo. Kenyan dyads (n = 26) were Kamba, a Bantu group that lives in eastern Kenya. South Korean dyads (n = 52) were recruited from the Seoul metropolitan area. Dyads from the United States (n = 100) were randomly selected from a larger sample of European Americans; 77% came from the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, including MD and VA, and 23% from rural WV. Sample sizes per community were designed so that the ratio of the smallest to largest would not exceed 1:4 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

All infants were approximately 5½ months of age, firstborn singletons, healthy, full term, and weighed 2500 – 5000 g at birth. By 5 or 6 months of age, infants are able to take the initiative leading to genuine turn-taking exchanges. Approximately equal numbers of girls and boys participated in each community sample. Sociodemographic characteristics of participating families are found in Table 1. Much previous research on cross-national differences in mother-infant interaction and communication has not accounted for participant or community differences in maternal age, education, and parity or family social class (Kärtner et al., 2008; Keller, Otto, Lamm, Yovsi, & Kärtner, 2008; Richman et al., 1992); all variables presented in Table 1 were considered as potential covariates if they correlated with dependent variables and shared at least 1% of their variance (r ≥ .10). Maternal age and education were significantly related to the rate of maternal vocalization, rs(682) = .36 and .38, ps < .001, respectively. No other variables in Table 1 met criteria as covariates.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

| Argentina (n = 99) |

Belgium (n = 100) |

Brazil (n = 58) |

Cameroon (n = 29) |

France (n = 49) |

Israel (n = 30) |

Italy (n = 92) |

Japan (n = 49) |

Kenya (n = 26) |

S. Korea (n = 52) |

USA (n = 100) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | |||||||||||

| Age (years)a |

25.31 (4.96) |

29.24 (3.66) |

26.37 (5.81) |

23.44 (3.12) |

30.67 (4.75) |

28.05 (3.55) |

27.23 (4.71) |

28.88 (3.55) |

21.44 (3.34) |

29.00 (2.13) |

27.83 (5.57) |

| Educationb | 3.96 (1.37) |

5.25 (0.97) |

4.22 (1.83) |

3.17 (1.63) |

5.45 (1.26) |

5.43 (0.73) |

3.54 (1.50) |

5.14 (1.00) |

2.62 (1.63) |

5.67 (0.86) |

5.34 (1.38) |

| Working Statusc |

37% | 81% | 55% | 38% | 63% | 30% | 17% | 17% | 15% | 42% | 59% |

| Marriedd | 75% | 80% | 59% | 72% | 67% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 35% | 100% | 89% |

| Nuclear Familye |

59% | 93% | 72% | 45% | N/A | 97% | 90% | 90% | 15% | 52% | 77% |

| Infant | |||||||||||

| Age (months) f |

5.40 (0.26) |

5.16 (0.30) |

5.15 (0.13) |

5.03 (0.14) |

5.49 (0.36) |

5.47 (0.16) |

5.09 (0.17) |

5.28 (0.31) |

5.20 (0.29) |

5.32 (0.16) |

5.35 (0.24) |

| Gender (Girls:Boys) g |

44:55 | 46:54 | 31:27 | 15:14 | 22:27 | 16:14 | 47:45 | 26:23 | 11:15 | 26:26 | 39:61 |

| Birth weight (g) h |

3467.12 (415.48) |

3458.45 (413.08) |

3307.16 (371.55) |

3272.50 (535.57) |

3303.67 (322.80) |

3346.21 (433.64) |

3265.11 (388.02) |

3109.35 (323.06) |

3071.67 (427.64) |

3330.67 (395.07) |

3462.71 (468.95) |

Notes. Sample sizes vary due to missing data. M (SD) unless otherwise specified. Chi-square tests examined community differences for the distributions of mothers working and child gender. For each of the other sociodemographic characteristics, ANOVAs with one between-subjects factor (Community) were performed, followed by t-tests with Bonferroni’s correction (α = .05; however, if variances were heterogeneous, α = .025 for pairwise comparisons).

Kenyan mothers were younger than mothers in all others countries except Cameroon; Cameroonian mothers were younger than mothers in all other countries except Argentina, Brazil, and Kenya; Argentine mothers were younger than all mothers except Brazilian, Cameroonian, Kenyan, Israeli, and Italian mothers; French mothers were older than Brazilian, Italian, and U.S. mothers; and Belgian mothers were older than Brazilian mothers, F(10, 673) = 14.93, p < .001, η2p = .18.

Because differences exist between countries in the duration, quality, and content of schooling, bicultural researchers adjusted mothers’ years of education so that the scales were equivalent to the 7-point Hollingshead (1975) index. Belgian, French, Israeli, Japanese, South Korean, and U.S. mothers had higher education than Argentine, Brazilian, Cameroonian, Italian, or Kenyan mothers; Argentine and Brazilian mothers had higher education than Kenyan mothers; and Brazilian mothers had higher education than Cameroonian mothers, F(10, 673) = 30.89, p < .001, η2p = .32.

The percentage of mothers who were working when their infants were 5 months old varied across countries, χ2 (10, N = 636) = 118.27, p < .001.

The percentage of mothers who were married when their infants were 5 months old varied across countries, χ2 (10, N = 629) = 114.35, p < .001.

The percentage of infants who lived in nuclear families varied across countries, χ2 (9, N = 569) = 114.59, p < .001.

At the time of the visit Argentine, French, and Israeli infants were older than Belgian, Brazilian, Cameroonian, Italian, and Kenyan infants; French and Israeli infants were older than Japanese infants; French infants were older than South Korean infants; South Korean and U.S. infants were older than Belgian, Brazilian, Cameroonian, or Italian infants; and Japanese infants were older than Cameroonian or Italian infants, F(10, 673) = 21.64, p < .001, η2p = .24.

No community differences, χ2 (10, N = 684) = 6.41, ns.

Argentine, Belgian, and U.S. infants weighed more than Japanese and Kenyan infants at birth, and Argentine and U.S. infants weighed more than Italian infants at birth, F(10, 665) = 5.71, p < .001, η2p = .08.

Procedures

Families were recruited using methods common to developmental science research with infants, including mass mailings, hospital birth notifications, patient lists of medical groups, newspaper birth announcements, and advertisements in newspapers. The research project was approved by institutional review boards of the first author and in individual countries and was carried out in accordance with the provisions of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. We attempted to remain faithful to a principle of ecological validity by focusing on naturalistic interactions between mothers and infants at home (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Connors & Glenn, 1996). Interactions were videorecorded at a time when the infant was awake and alert, and the only people at home were the mother, the infant, and one trained female videographer who was from the same community as the dyad she was filming. Mothers were instructed that observations were meant to be representative of the dyad’s typical routine and behavior and were encouraged to disregard the videographer’s presence insofar as possible; the videographer resisted talking to, making eye contact with, or otherwise reacting to the mother or infant while recording. Filming commenced after a conventional period of acclimation to the camera and the presence of the videographer (McCune-Nicolich & Fenson, 1984; Stevenson, Leavitt, Roach, Chapman, & Miller, 1986) and continued for 1 hr. Infants were awake for virtually the entire observation (M = 99.84%, SD = .01, range = 92–100%).

Behavioral Coding

The first 50 min of the hr were coded using mutually exclusive and exhaustive coding schemes for mothers and for infants. Onsets and offsets of maternal vocalization directed to the infant and infant nondistress vocalization were coded to the nearest 0.10 s. The minimum duration for a vocalization was set to 0.3 s, and an intervocalization gap of 1 s was necessary for a second vocalization to be counted as new.

We computed the rate (number of times per hour) that mothers vocalized to their infants (called maternal vocalization) and the rate (number of times per hour) that infants vocalized in positive or neutral tones (called infant nondistress vocalization).

Coders, unaware of the study design and goals, were first trained to reliability (Cohen’s, 1960, kappa: κ > .60) on a standard set of videorecords. Coder reliability was checked every 10 records to guard against coding drift. Intercoder agreement was calculated in ~30% of each sample. All coders achieved acceptable levels of coder reliability (Fleiss, 1981); specifically, reliability coefficients were assessed with κ separately for each of the 11 communities, and pairs of coders ranged from κ = .63 to .74 (agreements ranged from 86% to 96%).

Sequential Dependent Variables

Following procedures described in Bakeman and Quera (2011) and Bakeman and Gnisci (2005), two dependent variables that captured the sequential aspects of mother-infant vocal interaction were generated: (a) maternal vocal responsiveness (MVR), the odds that a mother spoke to her infant within 2 s of the offset of an infant nondistress vocalization relative to other times, and (b) infant vocal responsiveness (IVR), the odds that an infant vocalized nondistress within 2 s of the offset of a maternal vocalization directed to the infant relative to other times. A central feature of turn-taking is precision of timing. Turn transitions are commonly tightly synchronized, and the next speaker usually begins speaking with virtually no gap following the end of the prior speaker’s utterance. Extensive parametric research determined that a 2-s trailing-edge triggered window captures contingencies in mother-infant vocalizations in naturalistic settings (Van Egeren et al., 2001).

Separately for each dyad, time units were tallied in 2 × 2 contingency tables for behavioral sequences MVR and IVR. For example, the contingency table for MVR tallied the tenths of a second that a mother (a) vocalized in the time windows after her infant vocalized, (b) vocalized outside time windows after her infant vocalized, (c) did not vocalize in time windows after her infant vocalized, and (d) did not vocalize outside time windows after her infant vocalized. Based on these tables, odds ratios (OR) were computed for each behavioral pair (Bakeman, Deckner, & Quera, 2005). The OR is a descriptive measure of effect size. ORs > 1 indicate that bouts of the target behavior are more likely to begin within 2 s of the offset of the given behavior than at other times, whereas ORs < 1 indicate less likelihood. Concretely, an OR of 3.00 for infant vocal responsiveness means that the odds of the infant vocalizing nondistress within 2 s of the offset of the mother speaking to the infant is 3 times greater than otherwise. If fewer than 5 occurrences of the given behavior were observed, the value of the OR was regarded as missing for that dyad because there would not have been a sufficient sample of the behavior from that dyad to draw conclusions about contingency (Bakeman et al., 2005). Overall, data for very few dyads were insufficient; however, Kenya (12% of MVR and 27% of IVR) had larger proportions of insufficient data than other countries (≤ 2%). Rates and odds ratios were computed using the Generalized Sequential Querier program (GSEQ version 5.1.09) and were all square-root transformed (after adding a .03 start value) to resolve problems with skewness and kurtosis.

Results

Rates of Maternal and Infant Vocalization and their Correlations

In answer to the first question, analyses of covariance by community and gender, controlling for maternal age and education (infant age was unrelated to rates), showed that rates of maternal vocalization, F(10, 660) = 13.70, p < .001, η2p = .17, and infant vocalization, F(10, 662) = 13.14, p < .001, η2p = .17, varied across communities. Twenty-four of 55 between-community comparisons (44%) were significant for maternal vocalization, and 17 of 55 between-community comparisons (31%) were significant for infant vocalization (Table 2). Results were similar when maternal age and education controls were removed.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between maternal and infant rates of vocalization

| Rates per hour |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal vocalization | Infant vocalization | |||||

| n | M | SD | M | SD | r | |

| Argentina | 99 | 248.56abc | 120.54 | 139.26abc | 60.45 | .20* |

| Belgium | 100 | 280.44abc | 137.32 | 141.96abc | 74.25 | −.15 |

| Brazil | 58 | 200.54ade | 89.51 | 106.78ae | 49.92 | .35** |

| Cameroon | 29 | 80.53d | 58.36 | 115.26abe | 45.44 | .28 |

| France | 49 | 326.15abcf | 114.52 | 185.00d | 68.09 | −.09 |

| Israel | 30 | 252.29abc | 99.80 | 171.25bcd | 58.80 | −.03 |

| Italy | 92 | 289.79cf | 131.13 | 172.28cd | 68.00 | .04 |

| Japan | 49 | 246.29abe | 124.17 | 138.16abcd | 72.63 | .11 |

| Kenya | 26 | 110.20de | 101.10 | 196.27bcd | 61.19 | −.15 |

| South Korea | 52 | 376.07f | 105.36 | 75.36e | 50.34 | .17 |

| United States | 100 | 260.35ab | 112.98 | 143.98abc | 68.85 | .11 |

| Total | 684 | 260.89 | 131.49 | 142.40 | 70.36 | .03 |

Note. Descriptive statistics are based on untransformed variables, but statistical tests were performed on transformed variables. Community means that do not share subscripts within columns differed significantly (p < .025) in Bonferroni post-hoc tests. Correlations are one-tailed.

p < .05.

p < .01.

In answer to the second question, Pearson correlations were calculated to investigate whether members of a dyad who vocalize more have partners who also vocalize more (overall and separately for each community; Table 2). Rates of mother and infant vocalization were residualized for significant relations with covariates prior to computing these correlations. Rates were not significantly related across all communities or in any individual community (except for Argentina and Brazil, where mothers who vocalized more frequently had infants who vocalized more frequently).

Contingency of Maternal and Infant Vocalization and their Correlations

One sample t-tests were performed for all communities combined and separately for each community to determine, for the third question, whether pairs of behaviors were significantly contingent (i.e., whether ORs differed significantly from the transformed equivalent of 1; see descriptives in Table 3 and t-tests in Table 4). Maternal vocalization to infants was contingent on infants’ vocalizations overall, and in every community, with medium to large effect sizes (except in Cameroon and Kenya which had the smallest sample sizes). Infant nondistress vocalizations were contingent on their mothers' vocalizations to them overall and in approximately one-half of the communities.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between maternal and infant vocal contingencies

| Contingencies |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal vocal responsiveness |

Infant vocal responsiveness |

|||||

| n | M | SD | M | SD | r | |

| Argentina | 97 | 1.52ab | .74 | 1.18 | .51 | .35*** |

| Belgium | 99 | 1.22acd | .43 | 1.07 | .51 | .46*** |

| Brazil | 58 | 1.33abcd | .53 | 1.13 | .49 | .37**a |

| Cameroon | 29 | 1.46abcd | .91 | 1.26 | .69 | .55*** |

| France | 49 | 1.24abcd | .39 | 1.12 | .43 | .74*** |

| Israel | 30 | 1.38abcd | .46 | 1.06 | .38 | .62*** |

| Italy | 92 | 1.47ab | .56 | 1.19 | .39 | .55*** |

| Japan | 49 | 1.45abd | .61 | 1.19 | .40 | .42** |

| Kenya | 19 | 1.24c | .86 | 1.42 | .61 | .21 |

| South Korea | 51 | 1.12cd | .31 | 1.23 | .45 | .27* |

| United States | 100 | 1.51b | .66 | 1.14 | .44 | .40*** |

| Total | 673 | 1.38 | .59 | 1.16 | .47 | .42*** |

Note. Descriptive statistics are based on untransformed variables, but statistical tests were performed on transformed variables. Community means that do not share subscripts withincolumns differed significantly (p < .025) in Bonferroni post-hoc tests. There was no significant effect of community for IVR. Correlations are one-tailed.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

n = 57, excluding one influential outlier.

Table 4.

Contingencies in mother-infant vocal interactions

| Country | Maternal Vocal Responsiveness | Infant Vocal Responsiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | t(96) = 7.36, p < .001, d = .75 | t(96) = 2.57, p = .05, d = .26 |

| Belgium | t(98) = 5.01, p < .001, d = .50 | t(98) = 0.63, ns d = .06 |

| Brazil | t(57) = 4.47, p < .001, d = .59 | t(57) = 1.16, ns d = .15 |

| Cameroon | t(28) = 1.68, ns d = .31 | t(28) = 0.84, ns d = .16 |

| France | t(48) = 4.13, p < .001, d = .59 | t(48) = 1.41, ns d = .20 |

| Israel | t(29) = 4.25, p < .001, d = .78 | t(29) = 0.45, ns d = .08 |

| Italy | t(91) = 9.28, p < .001, d = .97 | t(91) = 4.44, p < .001, d = .46 |

| Japan | t(48) = 4.53, p < .001, d = .65 | t(48) = 2.69, p < .01, d = .38 |

| Kenyaa | t(17) = 1.52, ns d = .36 | t(17) = 2.93, p < .01, d = .69 |

| South Korea | t(50) = 2.28, p < .05, d = .32 | t(50) = 3.14, p < .01, d = .44 |

| United States | t(99) = 9.03, p < .001, d = .90 | t(99) = 2.33, p < .05, d = .23 |

| Total | t(671) = 16.49, p < .001, d = .64 | t(671) = 6.46, p < .001, d = .25 |

Note. One sample t-tests compared the mean OR to the transformed equivalent of 1.00.

One influential outlier was removed for Kenya.

Fourth, we explored whether MVR and IVR were similarly contingent overall and across communities. Pearson correlations were calculated to investigate whether mothers who were relatively more responsive to their infants’ vocalizations had infants who were relatively more responsive to their mothers’ vocalizations (Table 3). MVR and IVR were significantly correlated overall and in ten communities (except in Kenya).

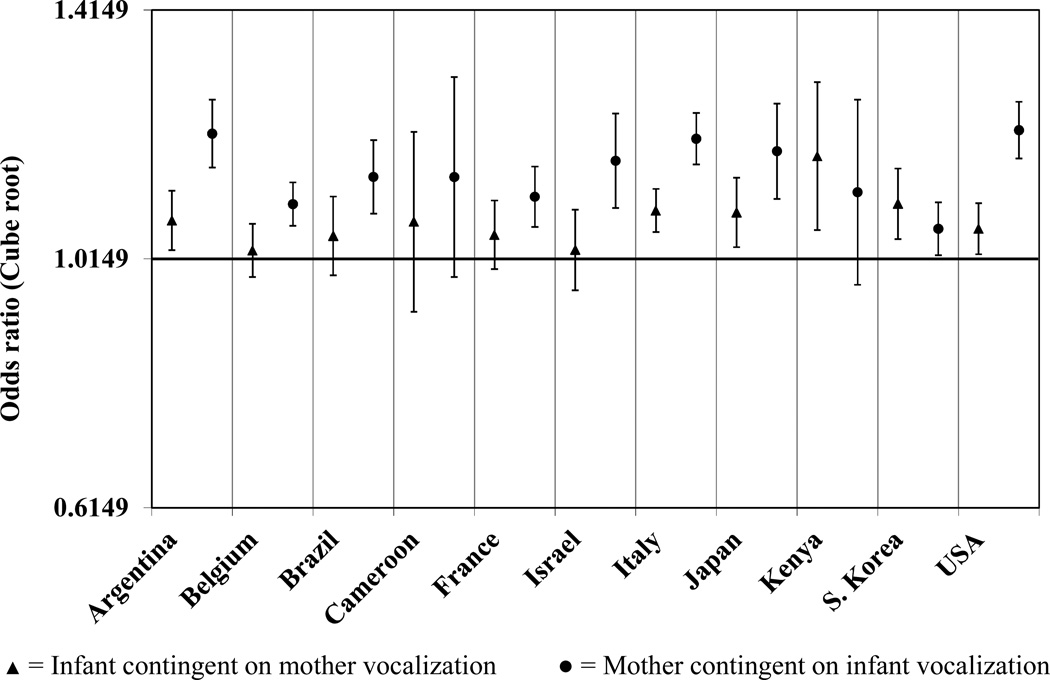

Finally, fifth, we analyzed whether mothers or infants were more responsive (Figure 1) using a repeated-measures analysis of variance (no covariates were related to ORs). Responder (mother vs. infant) was the within-subjects effect, and community and gender were between-subjects effects. Collapsing across communities, a main effect of Responder emerged, F(1, 671) = 99.13, p < .001, η2p = .129; mothers were more responsive partners than infants. However, the Community x Responder interaction was significant, F(10, 650) = 4.21, p < .001, η2p = .06. Analysis of simple effects of Responder within community indicated that mothers were more responsive partners than infants in Belgium, F(1, 95) = 7.97, p < .01, η2p = .08, Italy, F(1, 88) = 8.54, p < .01, η2p = .09, and the United States, F(1, 96) = 16.48, p < .001, η2p = .15. Mothers and infants were similarly responsive in the other communities. The simple effect of community for MVR was significant, F(10, 654) = 5.00, p < .001, η2p = .07; pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 3, and 10 of 55 (18%) community comparisons were significant. The simple effect of community for IVR was nonsignificant; across communities infants did not differ in their odds of vocalizing to their mothers in response to their mothers’ vocalizations.

Figure 1.

Contingency of mother and infant vocalizations by country. M ±95% confidence interval. The reference line at 1.0149 indicates a significant level of contingency. If an error bar overlaps the reference line, the behaviors are not significantly contingent. Error bars that do not overlap across countries indicate significant differences.

Discussion

Taken together, our findings point to community differences in overall rates of maternal and infant vocalization which are largely uncorrelated; however, mothers nearly universally spoke to their infants in response to their infants’ nondistress vocalizing, and when collapsing across communities infants’ nondistress vocalizations were significantly contingent on their mothers’ vocalizations to them. Differences emerged across communities in the strength of mothers’ responsiveness to infant vocalizations (although almost all were significantly contingent), but no community differences emerged in infant responsiveness to maternal vocalizations. Maternal and infant vocal responsiveness were also significantly correlated overall and in 10 of 11 communities, indicating that dyadic turn-taking rhythms are established in mothers and infants by the middle of the first year of life. Finally, and as expected, mothers were more responsive to their infants than their infants were to them. The face validity and consistency of findings from this cross-community study give evidence of the generalizability of our coding and contingency analysis approach, and the results extend findings about mother and infant “conversation” across communities in 11 countries around the globe.

Returning to our initial questions, first we found community differences in rates of maternal and infant vocalization. Different cultures hold different ethnotheories about the utility and meaningfulness of adult speech to infants (Dixon et al., 1982; Ochs, 1988; Richman et al., 1992), reflecting culture-specific interactional goals, conventions, or scripts for parenting (Bornstein, 2015). The dearth of maternal speech to infants in African samples we found has been commonly reported previously in the cross-cultural and anthropological literatures (e.g., Dixon et al., 1981; Keller et al., 2005; Rabain-Jamin, 1994; Richman et al., 1988). For example, Gusii mothers reportedly “ridicule” the idea of talking to children before they are able to speak, which they estimate at about 2 years of age (Richman et al., 1992), and social and religious representations in some African societies hold that a child who is not yet talking (or walking) is still “only a potential human being” (Bonnet, 1994; Goody, 1962; Lancy, 2013). Thus, variation in childrearing philosophies, values, and beliefs likely mediate community differences in maternal vocalization. For their part, community variation in infant vocalization may reflect temperament or its biological roots, for which there is growing cross-cultural evidence (Bornstein, 1989b; Chen & Schmidt, 2015).

Second, we found that infant and mother rates of vocalization were uncorrelated. Mothers and their infants did not vocalize in comparable degrees. A relatively talkative mother does not necessarily have a relatively talkative infant.

Rather, third, and centrally, we found that mothers overall and in most communities vocalized contingently in response to their infants’ vocalizing, just as their infants vocalized in response to their mothers’ vocalizations. We “equated” mothers on sociodemographic factors, such as age, education, and parity; and the communities we studied varied in structural characteristics from dwellings to geographic locations. Our results cannot readily be ascribed to differences in these variables, an important indication of a universal. Taken together, therefore, our findings point to community-common patterns of maternal and infant conversational turn-taking. Among different possible maternal responses to infant vocalization (speech, touch, play, smile), speech is the most common response in U.S. (Van Egeren et al., 2001) and in other samples (Bornstein et al., 1992; Kärtner et al., 2008). The consistent responsiveness in mothers to infant vocalization suggests that mothers may conceive of their infants as competent language partners, and mothers may be treating their baby’s nondistress vocalizations as incipient speech (Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986), even though infants had yet to form words and despite differences in overall talkativeness and possible variations in community meanings and emphases placed on mother-infant communication.

Amid a strong universal pattern, some cultural variation emerged. The lack of significant contingencies in Cameroon and Kenya may reflect their small sample sizes (a limitation of the study), higher proportions of missing data due to low rates of talking (in Kenya), and possible cultural belief systems that moderate universals. Lending support to the suggestion that power may have been the root limitation, odds ratios were above 1.00 for 69% of Cameroonian and 79% of Kenyan dyads, similar percentages to those in other countries (60%-88%). The mean odds ratios in Cameroon and Kenya were also consistent with those in the other countries (Table 3). Our findings also accord with others in the literature; for example, German Muenster mothers show more contingent responses to their infants’ signals than Cameroonian Nso mothers (Keller et al., 2008). The nature of vocal interactions in African dyads and reasons for possible differences merit further investigation.

The overall cross-community pattern suggests that maternal vocal contingency is a general response tendency that serves broader functions in the early socialization of human children. Maternal infant-directed speech has been linked to increased infant brain activity (Zangl & Mills, 2007) and blood flow in the frontal cortex (Saito et al., 2006), physical growth (Monnot, 1999), early language skills (Thiessen, Hill, & Saffran, 2005), and social preferences (Schachner & Hannon, 2011), and maternal responsiveness to infant vocalizations predicts later child language development (Bornstein, Tamis-LeMonda, & Haynes, 1999). Our results suggest that, in addition to the automatic and universal way mothers speak to their infants using higher-frequency affect and intonation (e.g., “baby talk”; Burnham, Kitamura, & Vollmer-Conna, 2002; Soderstrom, 2007), maternal verbal responsiveness to infant vocalizations may be a universal characteristic that could also promote diverse social aspects of child development. For example, it is impolite to interrupt; rather, we wait our turn … to speak and to act.

It is noteworthy that by 5 months of age infants overall vocalize back to their mothers contingent on their mothers' speech. Strong parallels in turn-taking across communities and languages of varied type, geographical location, and cultural traditions in 11 countries offer systematic support for the view that turn-taking in informal conversation is an early developing behavior consistent with the presence of a universal, stable system of conversation that avoids overlaps and minimizes gaps in interlocutor speech. The results argue for an interactional foundation for language that is relatively stable and separable from specific languages and cultural practices where it is instantiated (Levinson, 2006).

Fourth, unlike the raw vocalization frequencies, infant and maternal vocal responsiveness were generally correlated. Infant and maternal vocal responsiveness were not significantly correlated in Kenya, which may be a consequence of the small sample size Infants who are more vocally responsive to their mothers have mothers who are more vocally responsive to their infants and vice–versa. By 5 months, mothers and infants are coming into turn-taking attunement with its several developmental benefits (Bornstein, 2013). Turns in dialogue are not isolated utterances, but are bidirectional and linked across interlocutors so that interlocutors often tightly interleave and align channels of production and comprehension. Such counterphased mutual entrainment between speaker and listener further suggests that interlocutors activate their production systems even when listening because they have to be prepared to become the speaker. These inferences raise compelling developmental questions.

Finally, fifth, we found that mothers tended to be more responsive to their infants than infants were to their mothers. Thinking about parent-child relationships naturally highlights parents as agents of children’s socialization, and there is ample evidence, especially in the early years, that, between parents and children, parents exert more sway and young children command less agency (Elias, Hayes, & Broerse, 1986; Kochanska & Aksan, 2004; Maccoby, 1992; Vygotsky, 1978). This asymmetrical finding therefore accords with other developmental observations concerned with transaction. Maternal responsiveness has attracted the attention of developmental researchers because it faithfully reflects a recurring and significant three-event sequence in everyday exchanges between child and parent that involves child act, parent reaction, and effect on child, and because responsiveness has been found to possess meaningful predictive validity over diverse domains of children’s development (Bornstein et al., 1992). Maternal responding serves notice to the infant that mother is attending (a key part of learning about interaction, intentionality, causation, and the like is figuring out when your partner is attending to or has been affected by your behavior), just as responsiveness maintains infant attention and continues the interaction (Bornstein, Arterberry, & Lamb, 2014; Stern, 1985). Responsiveness is central to a mother’s job in scaffolding the development of her infant, and by being vocally responsive mothers reinforce and motivate their infants’ vocalizations. To a considerable degree, however, parent-infant transactions are a two-way street, and infants actively select, modify, interpret, and create their own environments, including their parenting, as maternal responsiveness is, after all, reaction to an infant act (Murray & Trevarthen, 1986).

Implications and Future Directions

Because conversations need to be organized, and to ensure that conversations proceed smoothly, rules of turn-taking in speech establish order. Language is fundamentally grounded in social interaction, and it is likely that the turn-taking mechanisms underlying verbal and social interaction coevolved. Thinking developmentally, it is therefore meaningful to ask how mother-infant dyads engage in such efficient turn-taking and how they develop turn taking so quickly. Models of inter-turn intervals indicate that speakers and listeners synchronize their speech during dialogue to establish communication and maintain equilibrium (Wilson & Wilson, 2005). Turn-taking must develop very quickly, and its functioning cannot depend on complex decisions or await marshalling considerable resources, suggesting that turn-taking is automatic and emerges without conscious effort. There is evidence that adult interlocutors are almost entirely unaware of the dynamics of turn taking (e.g., they more or less immediately imitate each other’s grammar; Pickering & Garrod, 2004, 2007). Adult listeners also likely project an upcoming end of a turn using multiple semantic, syntactic, prosodic, attentional, or body movement cues produced by the speaker, and reciprocally a variety of devices has been proposed by which adult listeners indicate their desire to take a turn, such as movements, audible inbreaths, or interjected words. However, vocal signals alone are sufficient to coordinate smooth turn-taking as Shockley, Santana, and Fowler (2003) learned that coordination between partners was carried by verbal, and not by visual, signals. Developmental approaches to unpackaging the transaction of turn taking need to address facts such as one partner talks at a time; although speakers change, the duration and ordering of turns vary; transitions are finely coordinated; and techniques exist for allocating turns. On what cues do mothers and 5-month-old infants rely?

The findings of this study indicate that turn-taking conversation has developed by 5 months of age before infants produce their first words. This pattern of interaction is (nearly) universal across various communities, despite large differences in the overall talkativeness of partners. These conversational skills seem to unfold early, automatically, and without formal instruction. Rather, conversations emerge as an integral ingredient of children’s earliest interactions.

References

- Aubanel V, Cooke M, Villegas J, Lecumberri MLG. Interspeech. Italy: Florence; 2011. Conversing in the presence of a competing conversation: Effects on speech production; pp. 2833–2836. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Deckner DF, Quera V. Analysis of behavioral streams. In: Teti DM, editor. Handbook of research methods in developmental science. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2005. pp. 394–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Gnisci A. Sequential observational methods. In: Eid M, Diener E, editors. Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Gottman JM. Observing interaction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, Quera V. Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. Parent, child, and reciprocal influences. American Psychologist. 1979;34:821–826. [Google Scholar]

- Black JW. The effect of delayed side-tone upon vocal rate and intensity. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1951;16:56–60. doi: 10.1044/jshd.1601.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D. L’éternal retour ou le destin singulier de l’enfant. L’Homme. 1994;34:93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Maternal responsiveness: Characteristics and consequences. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1989a. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Cross-cultural developmental comparisons: The case of Japanese-American infant and mother activities and interactions. What we know, what we need to know, and why we need to know. Developmental Review. 1989b;9:171–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Mother-infant attunement: A multilevel approach via body, brain, and behavior. In: Legerstee M, Haley DW, Bornstein MH, editors. The infant mind: Origins of the social brain. New York: Guilford; 2013. pp. 266–298. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Children’s parents. In: Lerner RM, Bornstein MH, Leventhal T, editors. Ecological settings and processes in developmental systems. Volume 4 of the Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015. pp. 55–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Arterberry ME, Lamb ME. Development in Infancy: A Contemporary Introduction. 5th ed. New York: Psychology Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Haynes OM. First words in the second year: Continuity, stability, and models of concurrent and predictive correspondence in vocabulary and verbal responsiveness across age and context. Infant Behavior and Development. 1999;22:65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Tal J, Ludemann P, Toda S, Rahn CW, Vardi D. Maternal responsiveness to infants in three societies: The United States, France, and Japan. Child Development. 1992;63:808–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham D, Kitamura C, Vollmer-Conna U. What’s new, pussycat? On talking to babies and animals. Science. 2002;296:1435–1435. doi: 10.1126/science.1069587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart R, Tillman TW, Greetis ES. Perceptual masking in multiple sound backgrounds. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1969;45:694–703. doi: 10.1121/1.1911445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers J. Who’s next? The melodic marking of question vs. continuation in Dutch. Language & Speech. 1998;41:375–398. doi: 10.1177/002383099804100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill W, Weinstein H. Maternal care and infant behavior in Japan and America. Psychiatry. 1969;32:12–43. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1969.11023572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Schmidt LA. Temperament and personality. In: Lamb ME, editor. Social, emotional, and personality development. Volume 3 of the Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015. pp. xx–xx. Editor-in-chief: R. M. Lerner. [Google Scholar]

- Chew JJ. The structure of Japanese baby talk. Newsletter of the Association of Japanese Teachers. 1969;6:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Coates J, Sutton-Spence R. Turn-taking patterns in deaf conversation. Journal of Sociolinguistics. 2001;5:507–529. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Connors E, Glenn SM. Methodological considerations in observing mother-infant interactions in natural settings. In: Haworth J, editor. Psychological research: Innovative methods and strategies. New York: Routledge; 1996. pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Cowie R, Douglas-Cowie E, Kerr AG. A study of speech deterioration in post-lingually deafened adults. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 1982;96:101–112. doi: 10.1017/s002221510009229x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown CL, Feldstein S, Jasnow MD, Beebe B, Jaffe J. The cross-modal coordination of interpersonal timing: Six-week-olds infants’ gaze with adults’ vocal behavior. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2002;31:1–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1014301303616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruiter JP, Mitterer H, Enfield NJ. Projecting the end of a speaker’s turn: A cognitive cornerstone of conversation. Language. 2006;82:515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S, Keefer C, Tronick E, Brazelton TB. Perinatal circumstances and newborn outcome among the Gusii of Kenya: Assessment of risk. Infant Behavior and Development. 1982;5:11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SD, Tronick EZ, Keefer C, Brazelton TB. Mother-infant interaction among the Gusii of Kenya. In: Field TM, Sostek AM, Vietze P, Leiderman PH, editors. Culture and early interactions. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Elias G, Hayes A, Broerse J. Maternal control of co-vocalization and inter-speaker silences in mother-infant vocal engagements. Journal of Child Psycholgy & Psychiatry. 1986;27:409–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CA. Baby talk as a simplified register. In: Snow C, Ferguson CA, editors. Talking to children: Language input and acquisition. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1977. pp. 209–235. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1981. pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A. Early adult-infant interaction: Expectable sequences of behaviour. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1982;7:1–22. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/7.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel A, Toda S, Kawai M. Mother-infant face-to-face interaction in Japan and the United States: A laboratory comparison using 3-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:398–406. [Google Scholar]

- Fukawa T, Yoshioka H, Ozawa E, Yoshida S. Difference of susceptibility to delayed auditory feedback between stutterers and nonstutterers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1988;31:475–479. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3103.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrod S, Pickering MJ. Why is conversation so easy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers AE, Nicholas JG, Sedey AL. Language skills of children with early cochlear implantation. Ear and Hearing. 2003;24:46S–58S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051689.57380.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely G, Nádasdy Z, Csibra G, Biró S. Taking the intentional stance at 12 months of age. Cognition. 1995;56:165–193. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00661-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goody J. Death, property and the ancestors. A study of the mortuary customs of the LoDagaa of West Africa. London: Tavistock; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Ringland JT. The analysis of dominance and bidirectionality in social development. Child Development. 1981;52:393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Gros-Louis J, West MJ, Goldstein MH, King AP. Mothers provide differential feedback to infants’ prelinguistic sounds. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2006;30:509–516. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez OM. Turn-taking Egyptian Arabic: Spontaneous speech vs. drama dialogue. Journal of Pragmatics. 1991;15:59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Holmlund C. Development of turntakings as a sensorimotor process in the first 3 months: A sequential analysis. In: Nelson KE, Reger Z, editors. Children’s language. Vol. 8. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Howell P, Powell DJ. Delayed auditory feedback with delayed sounds varying in duration. Perception and Psychophysics. 1987;42:166–172. doi: 10.3758/bf03210505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H, Fogel A. Social regulatory effects of infant nondistress vocalization on maternal behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:976–991. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasnow M, Feldstein S. Adult-like temporal characteristics of mother-infant vocal interactions. Child Development. 1986;57:754–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärtner J, Keller H, Lamm B, Abels M, Yovsi RD, Chaudhary N, Su Y. Similarities and differences in contingency experiences of 3-month-olds across sociocultural contexts. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:488–500. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye K. The mental and social life of babies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, Kärtner J, Borke J, Yovski R, Kleis A. Parenting styles and the development of the categorical self: A longitudinal study on mirror self-recognition in Cameroonian Nso and German families. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:496–504. [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, Otto H, Lamm B, Yovsi RD, Kärtner J. The timing of verbal/vocal communications between mothers and their infants: A longitudinal cross-cultural comparison. Infant Behavior & Development. 2008;31:217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, Schölmerich A, Eibl-Eibesfeldt I. Communication patterns in adult-infant interactions in Western and non-Western cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1988;19:427–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerbeck S. The organization of discourse units in Mexican and Danish business negotiations. Journal of Pragmatics. 1998;30:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Development of mutual responsiveness between parents and their young children. Child Development. 2004;75:1657–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konner M. Infancy among the Kalahari Desert San. In: Leiderman PH, Tulkin SR, Rosenfeld A, editors. Culture and infancy: Variations in the human experience. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 287–328. [Google Scholar]

- La France M. Nonverbal cues to conversational turn taking between black speakers. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 1974;1:240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Lancy DF. “Babies aren’t persons”: A survey of delayed personhood. In: Keller H, Hiltrud O, editors. Different faces of attachment: Cultural variations of a universal human need. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1436&context=sswa_facpub. [Google Scholar]

- Langford D. Analyzing talk: Investigating verbal interaction in English. London: Macmillan Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelli M, Fogel A. Developmental changes in the relationship between the infant’s attention and emotion during early face-to-face communication: The 2-month transition. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:265–280. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner GH, Takagi T. On the place of linguistic resources in the organization of talk-in-interaction: A co-investigation of English and Japanese grammatical practices. Journal of Pragmatics. 1999;31:49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson SC. On the human “interaction engine”. In: Enfield NJ, Levinson SC, editors. Roots of human sociality: Cognition, culture, and interaction. London: Berg; 2006. pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard E. Le signe d’elevation de la voix. Annales des maladies de l’oreille et du larynx. 1911;37:101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay DG. Metamorphosis of a critical interval: Age-linked changes in the delay in auditory feedback that produces maximal disruption of speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1968;43:811–821. doi: 10.1121/1.1910900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masataka N. Effects of contingent and noncontingent maternal stimulation on the vocal behavior of three- to four-month-old Japanese infants. Journal of Child Language. 1993;20:303–312. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900008291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCune-Nicolich L, Fenson L. Methodological issues in studying early pretend play. In: Yawkey TD, Pelligrini AD, editors. Child’s play: Developmental and applied. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 81–124. [Google Scholar]

- Mesch J. Tactile Swedish Sign Language: Turn taking in signed conversations of people who are deaf and blind. In: Metzger M, editor. Bilingualism and identity in deaf communities. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press; 2000. pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mesch J. Tactile sign language: Turn taking and questions in signed conversations of deaf-blind people. Hamburg, Germany: Signum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Monnot M. Function of infant-directed speech. Human Nature. 1999;10:415–443. doi: 10.1007/s12110-999-1010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K. Intrusive or co-operative? A cross-cultural study of interruption. Journal of Pragmatics. 1994;21:385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Trevarthen C. The infant’s role in mother-infant communication. Journal of Child Language. 1986;13:15–29. doi: 10.1017/s0305000900000271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenzayan A, Heine SJ. Psychological universals: What are they and how can we know? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:763–784. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochs E. Culture and language development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Papoušek M, Papoušek H, Bornstein MH. The naturalistic vocal environment of young infants: On the significance of homogeneity and variability in parental speech. In: Field T, Fox N, editors. Social perception in infants. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1985. pp. 269–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, Garrod S. Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2004;27:169–225. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x04000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering MJ, Garrod S. Do people use language production to make predictions during comprehension? TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabain-Jamin J. Language and socialization of the child in African families living in France. In: Greenfield PM, Cocking R, editors. Cross-cultural roots of the minority child development. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Richman AL, LeVine RA, Staples New R, Howrigan GA, Welles-Nystron B, LeVine SE. Maternal behavior to infants in five cultures. In: LeVine RA, Miller PM, Maxwell West M, editors. Parenting behavior in diverse societies. Vol. 40. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1988. pp. 81–98. New directions for child development. [Google Scholar]

- Richman A, Miller P, LeVine R. Cultural and educational variations in maternal responsiveness. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:614–621. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins O, Devoe S, Wiener M. Social patterns of turn-taking: Nonverbal regulators. Journal of Communication. 1978;28:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter DR, Durkin K. Turn-taking in mother-infant interaction: An examination of vocalizations and gaze. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H. Sociological description. Berkeley Journal of Sociology. 1963;8:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H, Schegloff EA, Jefferson G. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language. 1974;50:696–735. [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Aoyama S, Kondo T, Fukumoto R, Konishi N, Nakamura K, …Toshima T. Frontal cerebral blood flow change associated with infant-directed speech. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2006;92:F113–F116. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.097949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachner A, Hannon EE. Infant-directed speech drives preferences in 5-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:19–25. doi: 10.1037/a0020740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauwers K, Gillis S, Daemers K, De Beukelaer C, De Ceulaer G, Yperman M, Govaerts PJ. Normal hearing and language development in a deaf-born child. Otology & Neurotology. 2004;25:924–929. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA. Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist. 1968;70:1075–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA. Interaction: The infrastructure for social institutions, the natural ecological niche for language, and the arena in which culture is enacted. In: Enfield NJ, Levinson SC, editors. Roots of human sociality: Culture, cognition, and interaction. Oxford: Berg; 2006. pp. 70–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff EA, Jefferson G, Sacks H. The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language. 1977;53:361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Schieffelin BB, Ochs E. Language socialization. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1986;15:163–191. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley K, Santana MV, Fowler CA. Mutual interpersonal postural constraints are involved in cooperative conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 2003;29:326–332. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.29.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidnell J. Conversational turn-taking in a Caribbean English Creole. Journal of Pragmatics. 2001;33:1263–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel GM, Schork EJ, Jr, Pick HL, Jr, Garber SR. Parameters of auditory feedback. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1982;25:473–475. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2503.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow CE. The development of conversation between mothers and babies. Journal of Child Language. 1977;4:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom M. Beyond babytalk: Re-evaluating the nature and content of speech input to preverbal infants. Developmental Review. 2007;27:501–532. [Google Scholar]

- Stern DN. The interpersonal world of the infant. New York: Basic; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MB, Leavitt LA, Roach MA, Chapman RS, Miller JF. Mothers’ speech to their 1-year-old infants in home and laboratory settings. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1986;15:451–461. doi: 10.1007/BF01067725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MB, Ver Hoeve JN, Roach MA, Leavitt LA. The beginning of conversation: Early patterns of mother-infant vocal responsiveness. Infant Behavior and Development. 1986;9:423–440. [Google Scholar]

- Stivers T, Enfield NJ, Brown P, Englert C, Hayashi M, Heinemann T, Levinson S. Universals and cultural variation in turn-taking in conversation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:10587–10592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903616106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeck J. A little Ilokano grammar as it appears in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics. 1996;26:189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Striano T, Henning A, Stahl D. Sensitivity to interpersonal timing at 3 and 6 months of age. Interaction Studies. 2006;7:251–271. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. New York: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. Turn-taking in Japanese conversation: A study in grammar and interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. The particle ne as a turn-management device in Japanese conversation. Journal of Pragmatics. 2000a;32:1135–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. Turn projection in Japanese talk-in-interaction. Research on Language & Social Interaction. 2000b;33:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen ED, Hill EA, Saffran JR. Infant-directed speech facilitates word segmentation. Infancy. 2005;7:53–71. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Bornstein MH, Marlow M, Swartz L. Imbalances in the knowledge about infant mental health in rich and poor countries: Too little progress in bridging the gap. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2014;35:624–629. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C. Communication and cooperation in early infancy: A description of primary intersubjectivity. In: Bullowa M, editor. Before speech: The beginning of interpersonal communication. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1979. pp. 321–347. [Google Scholar]

- Van Egeren LA, Barratt MS, Roach MA. Mother-infant responsiveness: Timing, mutual regulation, and interactional context. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:684–697. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. The genesis of higher mental functions. In: Wertsch JV, editor. The concept of activity in Soviet psychology. New York: M. E. Sharpe; 1981. pp. 3144–3188. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, Wilson TP. An oscillator model of the timing of turn-taking. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2005;12:957–968. doi: 10.3758/bf03206432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TP, Wiemann JM, Zimmerman DH. Models of turn-taking in conversational interaction. Journal of Language & Social Psychology. 1984;3:159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zangl R, Mills DL. Increased brain activity to infant-directed speech in 6- and 13-month-old infants. Infancy. 2007;11:31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng ZZ, Munhall KG, Johnsrude IS. Functional overlap between regions involved in speech perception and in monitoring one’s own voice during speech production. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;22:1770–1781. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]