Summary

The locus coeruleus noradrenergic (LC-NE) system is one of the first systems engaged following a stressful event. While numerous groups have demonstrated that LC-NE neurons are activated by many different stressors, the underlying neural circuitry and the role of this activity in generating stress-induced anxiety has not been elucidated. Using a combination of in vivo chemogenetics, optogenetics, and retrograde tracing we determine that increased tonic activity of the LC-NE system is necessary and sufficient for stress-induced anxiety and aversion. Selective inhibition of LC-NE neurons during stress prevents subsequent anxiety-like behavior. Exogenously increasing tonic, but not phasic, activity of LC-NE neurons is alone sufficient for anxiety-like and aversive behavior. Furthermore, endogenous corticotropin releasing hormone+ (CRH+) LC inputs from the amygdala increase tonic LC activity, inducing anxiety-like behaviors. These studies position the LC-NE system as a critical mediator of acute stress-induced anxiety and offer a potential intervention for preventing stress-related affective disorders.

Keywords: locus coeruleus, noradrenergic, stress, anxiety, Corticotropin releasing hormone, central nucleus of the amygdala, optogenetics, DREADDs

Introduction

Acute stress-induced anxiety helps maintain the arousal and vigilance required to sustain attention, accomplish necessary tasks, and avoid repeated exposures to dangerous conditions. Recent basic neuroscience has elucidated circuits throughout the limbic system that are either natively anxiogenic or anxiolytic, building a circuit-based pathology that may yield more selective therapeutic approaches (Felix-Ortiz et al., 2013; Jennings et al., 2013; Kheirbek et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013a; Tye et al., 2011). However, these limbic structures do not exclusively control anxiogenesis, as elegant recent work reveals parallel systems for anxiety in the septohypothalamic circuitry related to persistent, stress-induced anxiety (Anthony et al., 2014; Heydendael et al., 2014). Additionally, the majority of these studies propose mechanisms mediated by the fast-acting, small molecule neurotransmitters, GABA and glutamate. However, clinically, we know that neuromodulators such as norepinephrine and various neuropeptides play pivotal roles in long-term outcomes following stress exposure (Raskind et al., 2013). Here we propose a separate neuromodulatory system underlying immediate, acute stress-induced anxiety.

The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system (LC-NE) is a small, tightly packed pontine brain region that sends numerous projections to the forebrain and spinal cord. The LC is involved in a broad number of physiological functions including arousal, memory, cognition, pain processing, behavioral flexibility, and stress reactivity (Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Carter et al., 2010; Hickey et al., 2014; Snyder et al., 2012; Tervo et al., 2014; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008; Vazey and Aston-Jones, 2014). The LC system is a major component of the centrally mediated fight-or-flight response with numerous environmental stressors, including social and predator stress, activating the LC-NE system (Bingham et al., 2011; Cassens et al., 1981; Curtis et al., 1997, 2012; Francis et al., 1999; Reyes et al., 2008; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008; Valentino et al., 1991). The response of the LC-NE systems to stress is particularly important in the context of stress-induced human neuropsychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Olson et al., 2011; Raskind et al., 2013).

Histologically and electrophysiologically identified noradrenergic neurons within the LC-NE system of both lightly anesthetized and freely moving rodents, felines, and primates exhibit three distinct activation profiles: low tonic, high tonic, and phasic activity. It has been proposed that these neurons fire differently to determine behavioral flexibility to various environmental challenges. Low tonic LC discharge (1–2 Hz) is consistent with an awake state (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a; Carter et al., 2010, 2012) whereas phasic burst activity results from distinct sensory stimuli such as flashes of light, auditory tones, and brief touch (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b; Foote et al., 1980). Stressful events and stimuli shift LC activity towards a high tonic mode of firing (3–8 Hz) and stress-related neuropeptide release, such as corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is thought to drive the high tonic state while simultaneously decreasing phasic firing events (Curtis et al., 1997, 2012; Jedema and Grace, 2004; Page and Abercrombie, 1999; Reyes et al., 2008; Snyder et al., 2012; Valentino and Foote, 1988). Anatomical data support this notion using tract tracing studies and electron microscopy to suggest that CRH-containing amygdalar monosynaptic projections from the CeA terminate in the LC (Reyes et al., 2008). Given the importance of CRH in stress-induced behavioral responses such as dysphoria, anxiety, and aversion (Bruchas et al., 2009; Francis et al., 1999; Gafford et al., 2012; Heinrichs et al., 1994; Koob, 1999; Land et al., 2008), these projections are situated to significantly impact LC neuronal activity. However, the functional consequences of these inputs remain unresolved. We examined the role of this high tonic activity of LC-NE neurons during stress and defined the endogenous substrates that drive this increased LC-NE activity.

Here we dissect the locus coeruleus circuitry in the context of stress-induced negative affective behavior. In particular, we use chemogenetics and optogenetics to focus on the role of neural activity of locus coeruleus noradrenergic (LC-NE) neurons in generating these behaviors. We find that LC-NE neurons have increased activity during stress and that blocking this elevated activity suppresses acute stress-induced anxiety. Furthermore, optogenetic activation and release of endogenous amygdalar CRH into the LC promotes anxiety-like and aversive behavior. We report that the LC and its afferent circuitry are critical for encoding and producing stress-induced anxiety.

Results

Selective inhibition of LC-NE neurons during stress suppresses subsequent anxiety

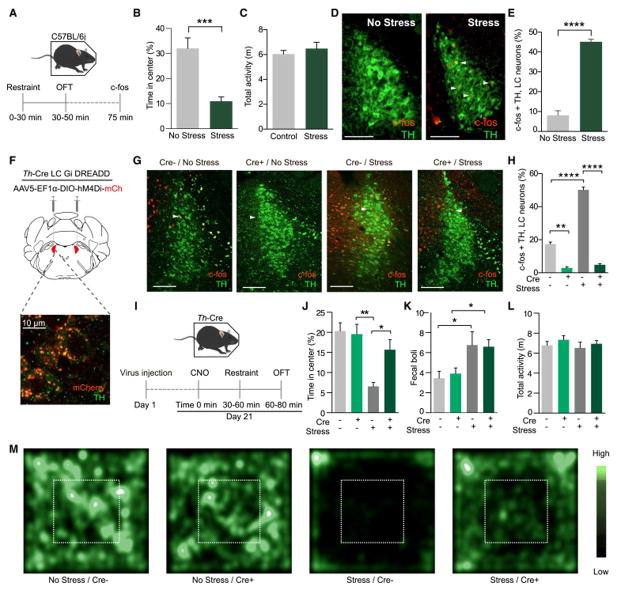

Numerous groups have reported that tonic activity of LC-NE neurons increases in response to stress (Bingham et al., 2011; Cassens et al., 1981; Curtis et al., 1997, 2012; Francis et al., 1999; Reyes et al., 2008; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008; Valentino et al., 1991). Others have demonstrated that non-selective pharmacological inactivation or lesions to the LC lessen morphine withdrawal symptoms, prevent footshock-evoked c-fos expression throughout the brain, and disrupt both unconditioned and conditioned aversive responses (Mirzaii-Dizgah et al., 2008; Neophytou et al., 2001; Passerin et al., 2000), but it has previously been untenable to selectively inhibit the activity of only these NE neurons and assess their role in stress-induced behaviors. To examine the role of LC-NE neurons in stress-induced anxiety-like behavior, we implemented a restraint stress paradigm, immediately followed by anxiety testing in the open field test (OFT) (Fig. 1A). Following 30 minutes of restraint stress, wild-type (C57BL/6J) mice produce a robust stress-induced anxiety phenotype and have increased immediate early gene (cfos) expression, consistent with increased activity of LC-NE neurons (Fig. 1B–E, Fig. S1A). To determine whether this increase in activity is necessary for the resultant anxiety-like behavior, we selectively targeted the inhibitory designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drug (Gαi-coupled; hM4Di DREADD (Armbruster et al., 2007) to LC-NE neurons by injecting a Cre-dependent AAV into the LC of tyrosine hydroxylase-IRES-Cre mice (Th-Cre) (Fig. 1F). When the receptor is activated by its ligand, Clozapine-n-oxide (CNO) at a dose previously demonstrated to alter LC activity in rodents ((10 mg/kg) (Vazey and Aston-Jones, 2014)) prior to stress, there is a significant decrease in stress-induced c-fos+ in LC-NE neurons indicating the selective hM4Di DREADD approach is effective at reducing LC-NE activity (Fig. 1G&H, Fig. S1B) during stress.

Figure 1. Chemogenetic inhibition of LC-NE neurons prevents stress-induced anxiety.

(A) Cartoon of restraint stress-induced anxiety paradigm. (B and C) Stressed animals spend significantly less time exploring the center of the OFT than non-stressed controls with no change in locomotor activity (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=7–8/group: Student’s t-test, p<0.001). (D and E) Representative immunohistochemistry (IHC) and quantification show restraint stress increases c-fos immunoreactivity (IR) in LC neurons (Red=c-fos, green=tyrosine hydroxylase, arrows indicate example co-localization, scale bars=100 μm; data represented as mean ± SEM, n=3 slices from 3 animals/group: Student’s t-test, p<0.0001). See locomotor activity data in Fig. S1. (E) Cartoon of viral strategy with high power confocal image of post-CNO internalized mCherry expression in LC-NE neurons. Scale bar=10 μm. (G and H) Representative IHC and quantification show hM4Di inhibition of LC neurons decreases c-fos IR in LC neurons (Red=c-fos, green=tyrosine hydroxylase, Scale bars=100 μm; data represented as mean ± SEM, n=3 slices from 3 animals/group: One-Way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc, No stress/Cre− vs. No stress/Cre+ **p<0.01, No stress/Cre− vs. Stress/Cre− ****p<0.0001, No stress/Cre− vs. Stress/Cre+ ****p<0.0001, No stress/Cre+ vs. Stress/Cre− ****p<0.0001, No stress/Cre+ vs. Stress/Cre+, not significant). See also Fig. S1. (I) Cartoon of LC-NE inhibition paradigm. (J) Inhibition of LC-NE neurons during stress blocks stress-induced anxiety. Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=8–13/group: One-Way ANOVA, Newman-Keuls post-hoc, No stress/Cre− vs. No stress/Cre+, not significant, No stress/Cre− vs. Stress/Cre− **p<0.01, No stress/Cre− vs. Stress/Cre+, not significant, No stress/Cre+ vs. Stress/Cre− **p<0.01, No stress/Cre+ vs. Stress/Cre+, not significant). (K) Inhibition of LC-NE neurons has no effect on stress-induced bowel motility. Data represented as mean ± SEM, n= n=8–13/group: One-Way ANOVA, Newman-Keuls post-hoc, No stress/Cre− vs. No stress/Cre+, not significant, No stress/Cre− vs. Stress/Cre− *p<0.05, No stress/Cre− vs. Stress/Cre+ *p<0.05, No stress/Cre+ vs. Stress/Cre−, not significant, No stress/Cre+ vs. Stress/Cre+, not significant). (L) Inhibition of LC-NE neurons has no effect on locomotor activity. Data represented as mean ± SEM. (M) Representative heat maps of activity during OFT.

Next, we used this hM4Di DREADD approach to test whether inhibition of LC-NE neurons during restraint stress can prevent subsequent stress-induced anxiety in the OFT (Fig. 1I). Stressed control animals not expressing the Cre-dependent hM4di (Th-CreLC:hM4Di−) show significant stress-induced anxiety-like behavior compared to unstressed animals regardless of hM4Di expression (Th-Cre LC:hM4Di− and Th-Cre LC:hM4Di+), seen in both time spent in the center and entries into the center of the OFT (Fig. 1J, Fig. S1C). Stressed Th-Cre LC:hM4Di+ animals, however, did not exhibit anxiety-like behavioral responses and instead have behavior similar to and not statistically different from both non-stressed Th-Cr LC:hM4Di+ and unstressed Th-Cre LC:hM4Di− mice (Fig. 1J, Fig. S1C). Interestingly, hM4Di DREADD-mediated inhibition of LC-NE neurons prior to stress did not alter stress-induced fecal output, suggesting that inhibition of LC-NE neurons suppresses acute stress-induced behavioral anxiety, but leaves other physiological responses intact (Fig. 1K) (Bruchas et al., 2009; Konturek et al., 2011). Importantly, the hM4Di manipulation has no effect on baseline anxiety levels and none of the manipulations affected locomotor activity (Fig. 1L&M). These findings suggest that intact LC-NE activity is needed during and after the stress experience to produce an acute stress-induced anxiety state.

Optogenetic entrainment of high tonic LC-NE activity

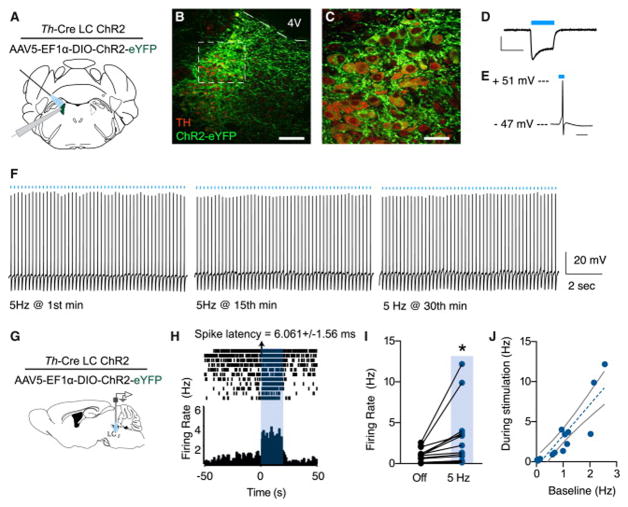

LC-NE neurons are reported to respond vigorously to stress with a robust increase in tonic firing rate (Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008). While this physiological response has been observed by many groups, the precise behavioral output of this increase has been previously inaccessible. We selectively targeted channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2(H134)-eYFP) to LC-NE neurons of Th-Cre mice (Th-CreLC:ChR2) and observed restricted eYFP labeling to the membranes of noradrenergic neurons of the LC (Fig. 2A–C). Slice recordings show that this targeting is sufficient to generate a photocurrent and action potentials in response to 470 nm light (Fig. 2D&E). To determine whether this strategy could be used to exogenously elevate the tonic firing of LC-NE neurons in a sustained fashion, we performed slice physiology experiments which demonstrated that LC-NE neurons can fire photostimulated action potentials at 5 Hz for as long as 30 minutes (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, in vivo extracellular recordings using a fiber optic-coupled multielectrode array showed that 5 Hz photostimulation produced responses similar to those evoked by stress (Bingham et al., 2011; Curtis et al., 2012) (Fig. 2G&H). Interestingly, putative LC neurons that did not appear to be directly photosensitive (>10 ms spike latency) still increased firing over time, perhaps due to well-known, tightly coupled nature of neurons in this structure (Alvarez et al., 2002) (Fig. 2I). Furthermore, indirect responses of these neurons to photostimulation is highly correlated (r=0.89, p< 0.0001) to their baseline firing suggesting that some LC neurons are potentially more intrinsically excited by broader LC activity (Fig. 2J). These findings indicate that optogenetic manipulation of LC-NE neurons can be used to sustain tonic firing of LC-NE that mimics their response to stress.

Figure 2. Optogenetic targeting to selectively drive tonic LC-NE activity.

(A) Cartoon of viral strategy for slice experiments. (B and C) Representative IHC shows selective targeting of ChR2-eYFP to TH+ LC neurons (Red= tyrosine hydroxylase, green=ChR2-eYFP, 4V = 4th ventricle, Scale bars= 100 and 50 μm, respectively). (D and E) Whole cell current- and voltage-clamp recordings of an LC-NE neuron expressing ChR2. D, scale bar is 200 pA x 100 ms and E, scale is 20 ms. (F) Slice recording of a single LC-NE neuron demonstrating action potentials over 30 min in response to 5 Hz 470 nm light. (G) Cartoon of viral and multielectrode delivery for anesthetized, in vivo recordings. (H) Peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) showing increased LC neuron firing during a 20 s optical stimulation at 5 Hz. (I) Firing rate of n=16 cells before and during 5 Hz photostimulation (Paired Student’s t-test, p<0.01). (J) Correlation of baseline activity to photostimulated activity (r=0.8938, p<0.0001).

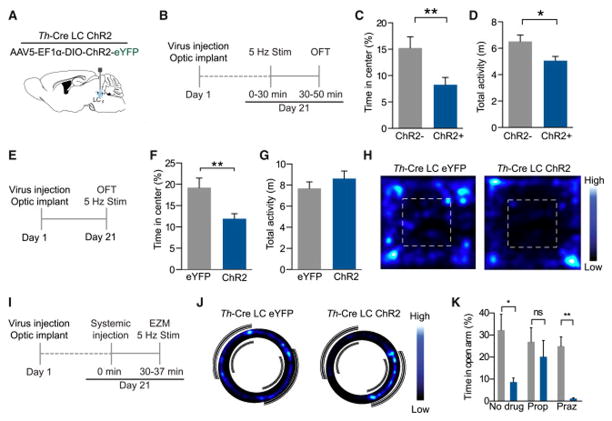

Increased LC-NE tonic neuronal firing is acutely anxiogenic

Using the same optogenetic strategy, we examined whether selectively increasing LC-NE tonic firing without a stressor is sufficient to mimic acute stress-induced anxiety-like behaviors. We photostimulated (5 Hz, 10 ms pulse width, 473 nm) LC-NE neurons for the same duration as the restraint stress paradigm and then placed the animals in the OFT (Fig. 3A&B) (Anthony et al., 2014). In this paradigm, Th-CreLC:ChR2 mice spent significantly less time exploring the center area than Cre− controls (Fig. 3C) indicating that exogenously increasing LC-NE firing rate can create a persistent anxiety-state and reduced locomotor behavior once the stimulation is removed (Fig. 3D, Fig. S2A). To assess whether the photostimulation itself can acutely drive anxiety-like behavior, we tested new animals with photostimulation during two assays of anxiety-like behavior, OFT and elevated zero maze (EZM) (Fig. 3E). In the OFT, photostimulated Th-CreLC:ChR2 mice spent significantly less time exploring the center area than did fluorophore expressing controls (Th-CreLC:eYFP) (Fig. 3F&G, Fig. S2C&D). Importantly, concurrent 5 Hz photostimulation does not affect total locomotor activity (Fig. 3G, Fig. S2B), suggesting 5 Hz LC-NE tonic activity selectively drives anxiety-like behavior. To determine what downstream receptor systems might be involved in the anxiety-like behavior induced by high tonic LC-NE activity, we repeated the concurrent photostimulation experiments using the EZM with selective systemic antagonism of either β-adrenergic receptors or α1-adrenergic receptors. 30 minutes prior to behavioral testing, we pre-treated animals with either the non-selective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist Propranolol HCl (10 mg/kg, i.p.), the α1-adrenergic antagonist Prazosin HCl (1 mg/kg, i.p.), or a vehicle control (Fig. 3I). We next photostimulated (5 Hz, 10 ms pulse width, 473 nm) LC-NE neurons during access to EZM (Fig. 3J & K). As we saw in Fig. 3F, 5 Hz photostimulation in the EZM induced anxiety-like behavior in Th-CreLC:ChR2+ compared to Th-CreLC:ChR2− control animals that do not express ChR2 (Fig. 3J & K). Th-CreLC:ChR2+ animals that were pre-treated with Propranolol were not significantly different from controls, indicating that systemic β-adrenergic antagonism reversed the effect of LC-NE photostimulation (Fig. 3K). Importantly, this was not the case in the animals treated with Prazosin (Fig. 3K). The blockade of α-adrenergic receptors in Th-CreLC:ChR2+ animals still showed an anxiogenic-like behavioral state following photostimulation (Fig. S2E). These experiments demonstrate that increasing the tonic firing rate of LC-NE neurons in the absence of a physical stressor is sufficient to produce robust anxiety-like behavior, requires NE, and is likely meditated by β-adrenergic receptor activity.

Figure 3. High tonic LC-NE neuronal activity is sufficient to induce anxiety-like behavior.

(A) Cartoon of viral and fiber optic delivery. (B) Calendar of pre-stimulation OFT studies. (C) 5 Hz photostimulation prior to OFT causes an anxiety-like phenotype of ChR2-expressing Th-Cre+ animals compared to Th-Cre− controls (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=14–15/group: Mann-Whitney t-test, p<0.01) with (D) a significant decrease in locomotor activity (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=14–15/group: Student’s t-test, p<0.05). (E) Calendar of concurrent stimulation OFT studies. (F) 5 Hz photostimulation drives anxiety-like behavior in OFT of Th-CreLC:ChR2 animals compared to Th-CreLC:eYFP controls (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=10/group: Student’s t-test, p<0.01) with (E) no change in locomotor activity (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=10/group). (H) Representative heat maps of activity in the OFT. See also Fig. S2. (I) Calendar of systemic antagonism in EZM studies. (J) Representative heat maps of activity in the EZM. (K) 5 Hz photostimulation drives anxiety-like behavior in EZM of Th-CreLC:ChR2 animals compared to Th-CreLC:eYFP controls, which is blocked by β-adrenergic antagonism (Prop), but not α1 antagonism (Praz) (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=6–9/group; Kruskal-Wallis One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01).

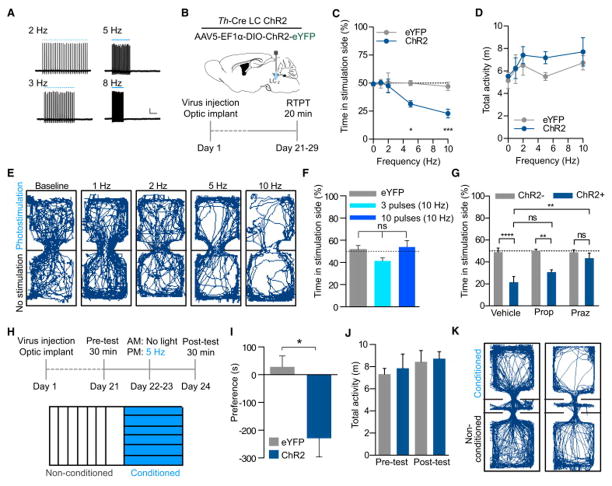

LC-NE tonic activity drives a frequency-dependent real time aversion

Following the observation that increased tonic activity of LC-NE neurons alone is capable of driving anxiety-like behaviors; we next sought to determine whether this activity produced aversion. Following slice electrophysiology experiments that demonstrated dynamic control of LC-NE firing at increasing frequencies while maintaining spike fidelity (Fig. 4A), we next sought to determine acute behavioral valence in Th-CreLC:ChR2 and Th-CreLC:eYFP mice at a range of photostimulation frequencies. To assess the positive or negative valence of the photostimulation we employed a real-time place-testing (RTPT) assay that triggers photostimulation upon the animal’s entry into a chamber void of salient contextual stimuli (Fig. 4B). This assay assesses native behavioral preference to photostimulation; regimes with a negative valence will cause an aversion from and those with a positive valence will drive a preference for the chamber paired with photostimulation (Kim et al., 2013a; Siuda et al., 2015; Stamatakis and Stuber, 2012; Tan et al., 2012). Without photostimulation and at low tonic firing rates similar to alert, awake LC activity (1 and 2 Hz) (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981a; Carter et al., 2010, 2012) there was no observable shift in chamber preference compared to baseline or Th-CreLC:eYFP control animals (Fig. 4C). However, when we increased the frequency of photostimulation to induce a higher tonic firing rate of LC-NE neurons (5 and 10 Hz), we observed a significant frequency-dependent shift away from the photostimulation-paired chamber (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that acutely increasing tonic firing of LC-NE neurons elicits a negative valence that is capable of biasing behavior to avoid the increased neuronal activity. As we found in the anxiety-like behavioral assays, there was no change in locomotor activity during any of the frequencies tested (Fig. 4D&E, Fig. S3A&B). To determine whether this negative valence was specifically due to increased tonic activity, we implemented the same RTPT assay using two different phasic photostimulation regimes (3 or 10 (10 ms) pulses at 10 Hz upon entry and every 30 s the mouse remains in the chamber). In the phasic photostimulation paradigm, we did not observe any negative or positive valence associated with either phasic regime (Fig. 4F, Fig. S3C&D). This finding is in line with evidence that suggests phasic responses of LC-NE neurons are elicited by salient stimuli rather than stressful events (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981b; Sara and Bouret, 2012).

Figure 4. LC-NE photostimulation drives both real-time and learned aversions.

(A) Current-clamp whole cell recording at 2, 3, 5 and 8 Hz. (B) Cartoon of viral and fiber optic delivery and calendar of behavioral studies. (C) Frequency response of RTPT and (D) locomotor activity at 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 Hz. Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=6–7/group: Two-Way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc, 5 Hz ChR2 vs. 5 Hz eYFP *p<0.05, 10 Hz ChR2 vs. 10 Hz eYFP ***p<0.001. (E) Representative traces of behavior at different frequencies. (F) Phasic stimulation does not drive aversion, n=6/group. (G) 5 Hz photostimulation causes a real-time place aversion in RTPT of Th-Cre+ animals expressing ChR2 in the LC compared to Th-Cre− control animals that do not express ChR2. This effect is not reversed by Propranolol (Prop) pre-treatment, but is by Prazosin (Praz) (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=6–10/group; One-Way ANOVA, Bonferonni post-hoc, ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, ns=no significance). (H) Timeline and cartoon of 5 Hz CPA experiment. (H) Mean preference (s) ± SEM, post-test minus pre-test (n=7–9; Student’s t-test, p<0.05). (I) No locomotor effect in either pre- or post-test. (J) Representative traces of behavior in the pre- and post-test. See also Fig. S3.

We next determined whether the same systemic antagonism of β-adrenergic receptors that prevented anxiety-like behavior could also prevent the acute negative behavioral valence seen in RTPT. We therefore repeated the experiment at 5 Hz with systemic treatments. Vehicle-treated Th-CreLC:ChR2+ animals display an aversion to the photostimulation-paired chamber as compared to Th-CreLC:ChR2− controls (Fig. 4G). Surprisingly, pre-treatment with Propranolol did not block the aversion (Fig. 4G). In contrast to our anxiety results, we found that pre-treatment with Prazosin blocked the real-time place aversion (Fig. 4G). Together, these data suggest that the negative affective behaviors elicited by elevating LC-NE tonic activity are pharmacologically separable.

While the RTPT assay provides clear evidence that increased tonic, but not phasic, activity of LC-NE neurons is acutely aversive; it does not provide information as to whether this activity is encoded and can be later retrieved to inform future behavior. A natural response to a stressful experience would be to avoid the context in which the stress occurred. To test whether increased tonic LC-NE activity produces a learned change in behavior, we employed a Pavlovian conditioned place aversion (CPA) assay (Bruchas et al., 2009; Al-Hasani et al., 2013; Land et al., 2008). In this assay, Th-CreLC:ChR2 and Th-CreLC:eYFP animals are exposed to two distinct visual contexts that have no initial bias. During conditioning, animals do not receive optical stimulation in one context and receive high tonic stimulation (5 Hz, 10 ms pulse widths) in the other context (Fig. 4H). When allowed to freely explore both chambers following conditioning, Th-CreLC:ChR2 animals spent significantly less time in the chamber that was paired with high tonic photostimulation (Fig. 4I). In contrast, Th-CreLC:eYFP controls did not show a change in behavior from their initial exploration and neither group showed altered locomotor activity (Fig. 4J&K, Fig. S3E). These results suggest that the negative valence and anxiety-like behaviors previously observed during high tonic photostimulation of LC-NE neurons are capable of being learned and influencing future behavior.

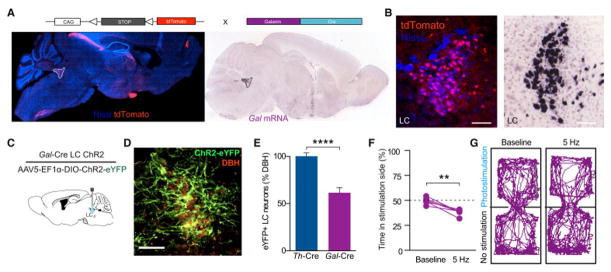

Photostimulation of galanin-containing LC-NE neurons is also sufficient to elicit aversion

In addition to the catalytic enzymes necessary for catecholamine production, a majority of LC-NE neurons also produce the neuropeptide galanin (Holets et al., 1988; Melander et al., 1986). Therefore, to further corroborate the results we observed using Th-Cre mice, we used mice expressing Cre recombinase under the promoter for Galanin (Gal-Cre) (Gong et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2014). To validate loci of Galanin expression we crossed these mice to a Cre-conditional tdTomato reporter line developed by the Allen Institute for Brain Science (Ai9) (Madisen et al., 2010). As predicted, we see dense, local expression in the LC as well as the hypothalamus and brainstem (Fig. 5A&B). We also observed some tdTomato+ cells in regions that do not have mRNA for galanin in the adult mouse (cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdalar structures) (Lein et al., 2007). In each of these regions we identify transient mRNA expression throughout development (Fig. S4). This Cre driver remains, however, a viable tool for selective targeting of the LC (Fig. 5C), as seen when we selectively targeted ChR2(H134)-eYFP to LC-NE neurons of Gal-Cre mice (Gal-CreLC:ChR2) there was restricted eYFP labeling to the membranes of noradrenergic neurons of the LC (Fig. 5D, Fig. S5). We found that eFYP expression was selective for LC-NE neurons (100% of eYFP expressing LC neurons were positive for the NE marker, dopamine beta hydroxylase (DBH+)). However, we found that only 61.48% of LC-NE neurons expressed ChR2(H134)-eYFP in the Gal-Cre line – significantly fewer than those in the Th-Cre line (Fig. 5E, Fig. S5). To test whether tonic photostimulation of this subpopulation of galanin-containing, LC-NE neurons also produces aversion, Gal-CreLC:ChR2 animals were tested in RTPT with and without photostimulation at 5 Hz. We found that increased tonic LC-NE stimulation in Gal-CreLC:ChR2 animals produced significant avoidance behavior, consistent with the behavior we observed under the same conditions in the Th-CreLC-ChR2 mice (Fig. 5F&G). These experiments corroborate our findings that high tonic stimulation of LC-NE neurons drives an aversive behavioral response and suggest that increased activity of the entire population of LC neurons may not be necessary to elicit aversive behavior.

Figure 5. Galanin containing LC-NE neurons are sufficient to drive place aversion.

(A and B) Galanin labeling in Gal-Cre x Ai9-tdTomato compared to in situ images from the Allen Institute for Brain Science in a sagittal section highlighting presence of galanin in the LC. All images show tdTomato (red) and Nissl (blue) staining. See also Fig. S4. (C) Cartoon of viral and fiber optic delivery. (D) IHC of ChR2-eYFP targeting to DBH+ LC neurons. Scale bar=100 μm. (E) Quantification of Cre-dependent eYFP viral expression in the LC of Th-Cre and Gal-Cre mouse lines. Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=3 slices from 3 animals/group: Student’s t-test, p<0.0001. See also Fig. S5. (F) 5 Hz stimulation of LC-Gal neurons drives aversion (n=6, Paired Student’s t-test, p<0.01). (G) Representative traces of behavior at different frequencies.

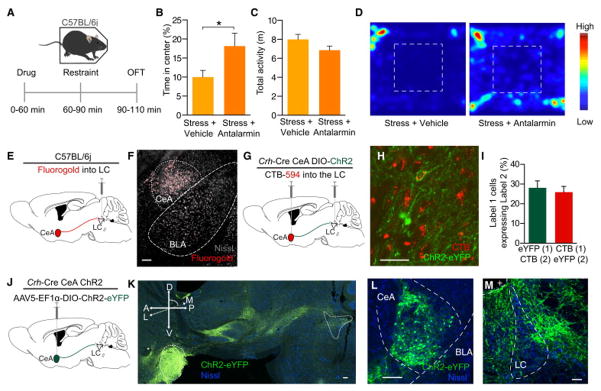

CRH+ neurons from the central amygdala send dense projections to the LC

Following observations that exogenously increasing tonic firing of LC-NE neurons is sufficient to drive anxiety-like and aversion behaviors in the absence of stress, we sought to determine the endogenous substrate for increased firing. Previously, CRH has been suggested as a potential mechanism for stress-induced increases in LC activity (Curtis et al., 1997, 2012; Jedema and Grace, 2004; Page and Abercrombie, 1999; Reyes et al., 2008; Snyder et al., 2012; Valentino and Foote, 1988). Consistent with these studies, we found that systemic antagonism (Antalarmin HCl, 10 mg/kg, i.p.) of endogenous CRH action on CRHR1 receptors is sufficient to prevent stress-induced anxiety (Fig. 6A–D) (Gafford et al., 2012; Heinrichs et al., 1994). We next determined whether the action of CRH locally within the LC is responsible for CRH-dependent anxiety-like behavior. To do so, we utilized two retrograde tracing approaches to examine potential sources of CRH input into the LC. First, we injected the tracer Fluorogold into the LC of C57Bl/6 mice (Fig. 6E). This non-selective retrograde tracing approach revealed known inputs into the LC from the cortex, hypothalamus, and central amygdala - a source of extrahypothalamic CRH (Bouret et al., 2003; Dimitrov et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2008) (Fig. 6F, Fig. S6). We next used a dual injection strategy to anatomically isolate LC-projecting, CRH+ neurons. To do so, we used mice expressing Cre under the promoter for CRH (Crh-Cre) mice (Taniguchi et al., 2011). We simultaneously injected a red-labeled retrograde tracer, Cholera Toxin Subunit B (CTB-594) (Conte et al., 2009), to the LC and the green-labeled AAV5-DIO-Ef1α-ChR2(H134)-eYFP to the CeA of these mice (Crh-CreCeA:ChR2; Fig. 6G). Here we visualized Crh+ neurons in the CeA project to the LC by observing significant colocalization of both fluorophores in single CeA neurons, indicating that these neurons project to the LC (Fig. 6H&I). Finally, to examine CRH+ terminal innervation of the LC, we only injected the Cre-dependent reporter AAV5-DIO-Ef1α-eYFP in the CeA of Crh-Cre mice (Fig. 6J). We clearly observed projections from the CeA to the LC in both transverse and coronal sections (Fig. 6K–M, Fig. S6F&G, Movie S1). These data identify a discrete projection of Crh+ neurons from the CeA to the LC that could act to provide CRH-induced increases in tonic LC activity.

Figure 6. Identifying a CRH+ CeA input to the LC.

(A) Calendar of pharmacological experiment. (B) CRF-R1 antagonism blocks stress-induced anxiety-like behavior (C) with no significant effect on locomotor activity (n=6–8/group, Student’s t-test, *p<0.05). (D) Representative heat maps show behavior in the OFT. (E) Cartoon depicting fluorgold tracing. (F) Representative image shows robust retrograde labeling of the CeA (Fluorgold pseudocolored red, Nissl=grey). See also Fig. S6. (G) Cartoon depicting dual injection tracing for CTB-594 and DIO-ChR2-eYFP. (H) Representative IHC shows retrograde labeling in CeA of CTB-594 (red) and anterograde labeling of CRH+ cells (green). Arrow indicates example co-localization. (I) ~25% of each label co-labels with the other. (J) Cartoon depicting anterograde tracing. (K) 71° off of sagittal slice of Crh-Cre mouse expressing DIO-eYFP in the CeA. Image shows intact projections from CeA to LC. Arrow indicates fiber optic placement. (L and M) Coronal image depict robust eYFP labeling in the CeA and LC of the same mouse. All scale bars=100 μm. + is 4th ventricle.

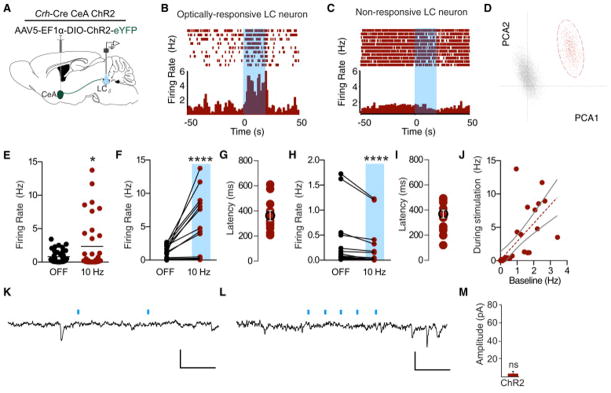

Photoactivation of CRH+ terminals in the LC causes increased tonic firing of LC neurons

We next determined the effects of stimulating the CRH terminals locally within the LC. In Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 mice, we recorded LC activity before, during, and after photostimulation (Fig. 7A). The CeA has been reported to spontaneously fire from 2–20 Hz (Ciocchi et al., 2010; Veinante and Freund-Mercier, 1998), so we used a 10 Hz photostimulation paradigm to maintain a physiologically-relevant frequency. In recordings of 35 putative LC neurons from 5 different animals, we found a heterogeneous population of responses including increased firing in a significant proportion of cells (42.8% of observed putative LC units) (Fig. 7B–F, Fig. S7A). While the overall sample of neurons significantly increased firing (Fig. 7E&F), we did observe an equal subset (42.8%) that decreased firing rate during photostimulation (Fig. 7H). In cases where the firing rate increased, the mean latency to fire was 344.6 ms, suggesting a neuromodulatory influence (Fig. 7F&G). Likewise, in cases where the firing rate decreased, the mean latency to fire was 360.0 ms (Fig. 7H&I). Similar to direct LC-NE photostimulation (Fig. 2J), we also observed that the increasing firing rates to Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 photostimulation, are correlated (r=.70, p< 0.0001) to the baseline state of each neuron, indicating that some LC neurons are more excitable by this projection than others. (Fig. 7J). This observed increase in firing is consistent with other reports following either stress or exogenous application of CRH (Curtis et al., 1997; Jedema and Grace, 2004; Page and Abercrombie, 1999). However, the slow onset of firing following photostimulation suggested that we did not observe any synaptically-mediated events. To further test for direct, monosynaptic events we made slice recordings of 35 LC neurons from 4 mice. While each slice exhibited dense ChR2+ axonal innervation of the LC (data not shown, but similar to Fig. 6M), we never observed any GABA-A IPSCs or AMPA-EPSCs at a variety of pulse paradigms (10, 20, 50, 100 Hz) (Fig. 7K–M). While we cannot definitively conclude that there are no direct, fast monosynaptic connections in this projection, these data suggest that the CeA projection mediates action in the LC through either slower neuromodulatory action or a more complex polysynaptic microcircuit.

Figure 7. CRH+ CeA-LC terminals modulate LC activity and drive anxiety through CRFR1 activation.

(A) Cartoon of viral and multi-electrode array delivery for anesthetized, in vivo recordings. (B and C) Representative PSTHs of putative LC neurons responding to 20s of 10 Hz, 10 ms pulse width photostimulation (473 nm, ~10 mW). (D) Representative principal component analysis plot showing the first two principal components with clear clustering of units. (E) Total recorded sample shows significant increase in firing rate to 10 Hz photostimulation (n=35, Wilcoxon matched- pairs signed rank test, p<0.05). (F) n=15 units increase firing rate by >10% during 10 Hz photostimulation (Wilcoxon matched- pairs signed rank test, p<0.0001). (G) Response latency following onset of photostimulation for cells that increase firing. (H) n=15 units decrease firing rate by >10% during 10 Hz photostimulation (Wilcoxon matched- pairs signed rank test, p<0.0001). See also Fig. S7A. (I) Response latency following onset of photostimulation for cells that increase firing. (J) Correlation of baseline activity to activity during photostimulation (r=0.7029, p<0.0001). Representative voltage-clamp traces following (K) 10 Hz, 3 ms photostimulation and (L) 50 Hz, 3 ms photostimulation of Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 terminals. Scale bars 30 pA; 50 ms. (M) Magnitude of the event after the first photostimulation. Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=35 cells from 4 brains.

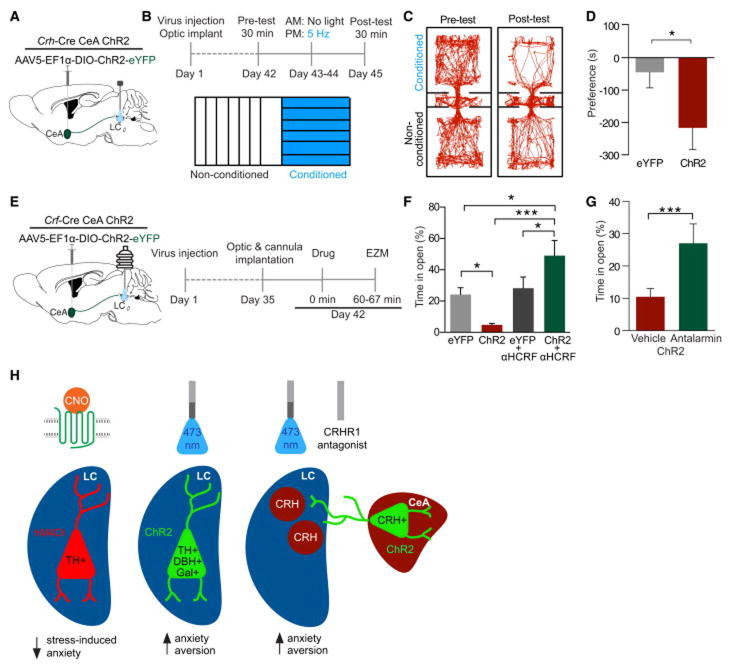

Stimulation of CRH+ CeA terminals in the LC is aversive and anxiogenic

We next assessed whether stimulation of these CRH+ CeA terminals would drive similar behavioral profiles to direct LC-NE stimulation or stress alone. In these experiments we used Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 and Crh-CreCeA-LC:eYFP animals with fiber optic implants over the LC (Fig. 8A). Using the same stimulation procedure we used during in vivo recordings (10 Hz, 10 ms pulse width), we first observed that photostimulation of CeA-LC CRH+ terminals conditions a place aversion in Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 compared to Crh-CreCeA-LC:eYFP controls (Fig. 8B,C&D). We next determined whether this stimulation was sufficient to induce anxiety-like behaviors in the EZM (Fig. 8E). In Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 animals, acute photostimulation produced significant anxiety-like behavior compared to Crh-CreCeA-LC:eYFP controls (Fig. 8F, Fig. S7B&C). Importantly, when we locally antagonize CRHRs directly in the LC prior to photostimatulation (α-helical CRF 1 μg, intra-LC) this effect is completely reversed unmasking an anxiolytic phenotype compared to fluorophore only-expressing antagonist controls, suggesting that CRH release from CeA-LC terminals is the substrate responsible for the photostimulation-induced anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 8F, S7B&C). Furthermore, systemic antagonism of CRHR1 (Antalarmin HCl, 10 mg/kg, i.p.) prior to photostimulation of Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 animals prevents the induced anxiety-like behavior (Fig. 8G). These results suggest that the CRH+ projection from the CeA to the LC carries both an aversive and anxiogenic component mediated through CRH+ activation of CRHR1 in the LC.

Figure 8. CRH+ CeA-LC terminals drive aversion and anxiety-like behavior through CRFR1 activity.

(A) Cartoon of viral and fiber optic delivery and (B) calendar of CPA behavior. (C and D) Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 show a significant CPA compared to Crh-CreCeA-LC:eYFP controls. Representative traces of behavior in the pre- and post-test and mean preference (s) ± SEM, post-test minus pre-test (n=10–12/group; Student’s t-test, p<0.05). (E) Cartoon of viral, cannula, and fiber optic delivery and calendar of EZM behavior. (F) 10 Hz photostimulation drives anxiety-like behavior in EZM of Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 animals compared to Crh-CreCeA-LC:eYFP controls, which is reversed by intra-LC α-helical-CRF (αHCRF) pretreatment (Data represented as mean ± SEM, n=7/group: One-Way ANOVA, Newman-Keuls, Crh-CreCeA-LC:eYFP vs. Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 *p<0.05, CreCeA-LC:eYFP vs. Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2+AHCRF **p<0.01, CreCeA-LC:ChR2 vs. Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2+AHCRF ***p<0.001). See also Fig. S7B&C. (G) Systemic CRHR1 antagonism reverses photostimulation-induced anxiety-like behavior (n=6–8/group, Student’s t-test, p<0.001). (H) Model and summary of results. See also Fig. S7D.

Discussion

The LC-NE system has long been implicated as a key mediator of the central stress response (Koob, 1999). Observational electrophysiological studies across many species identified that LC-NE neurons respond vigorously to stress and behavioral pharmacology has revealed a potential role for endogenous CRH in this response (Bingham et al., 2011; Cassens et al., 1981; Curtis et al., 1997, 2012; Francis et al., 1999; Jedema and Grace, 2004; Page and Abercrombie, 1999; Reyes et al., 2008; Snyder et al., 2012; Valentino et al., 1991; Valentino and Foote, 1988; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008). Here, we report that activity of LC-NE neurons is required to elicit acute stress-induced anxiety. Furthermore, selectively increasing the firing of LC-NE neurons is itself anxiogenic in the absence of stress and can inform future behavior through learned association. Finally, optogenetic stimulation of CRH+ CeA terminals into the LC replicates the acute anxiogenic and aversive behavioral state of direct LC-NE high tonic stimulation (Fig. 8H).

LC activity during stress is necessary for acute stress-induced anxiety

Noradrenergic tone is important for processing stressful stimuli, encoding fearful events, deciphering threatening versus non-threatening signals (Aston-Jones et al., 1999; Neophytou et al., 2001; Passerin et al., 2000; Snyder et al., 2012). The findings here that LC-NE activity is required to transmit this information and produce stress-induced anxiety-like behavior extends our understanding of the LC in stress and the “fight or flight” response. Interestingly, inhibition of the LC-NE system without stress did not affect baseline anxiety levels, suggesting that less LC activity is not necessarily anxiolytic. Furthermore, inhibiting LC-NE neurons during stress did not prevent other physiological readouts of stress, such as gastrointestinal motility. Future work will need to determine whether other stress-induced behaviors such as drug reinstatement and analgesia (Bannister et al., 2009; Al-Hasani et al., 2013; Hickey et al., 2014; Shaham et al., 2000) require increased LC-NE activity.

The chemogenetic inhibition approach used here is temporally restricted due to the kinetics of CNO activity and neuromodulatory effects of DREADDs. We used this approach so as to be agnostic to the timing of the stress-induced activity to capture the period of intense restraint-induced stress as well as the assay-evoked stress inherent in tests of anxiety-like behavior. However, it is not possible to precisely determine when it would be crucial to inhibit LC-NE activity to prevent stress-induced anxiety. Future studies using optogenetic inhibition during either stress or anxiety testing will be needed to ascertain the temporal dynamics of this system. Furthermore, the chemogenetic approach appeared to suppress LC-NE activity below baseline, indicating that some baseline LC-NE activity might be necessary for stress-induced anxiety. However, we do not believe this to be the case given that suppressing LC-NE in unstressed animals did not alter baselines anxiety-like behavior. Additionally, it is possible that only a subset of LC-NE neurons are required for stress-induced anxiety and previous studies have indicated that the dorsal-ventral axis of the LC has diverse actions (Hickey et al., 2014). Further study is needed to elucidate whether the microanatomy and local neural circuits within the LC play an important role in stress-induced anxiety.

High tonic LC-NE neuronal activity can initiate anxiety-like and aversive behavior

Recent studies have used optogenetics for binary control of acute anxiety (Felix-Ortiz et al., 2013; Heydendael et al., 2014; Jennings et al., 2013; Kheirbek et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013a, 2013b; Tye et al., 2011). These limbic circuits and their projections into the mesolimbic dopamine system have demonstrated rapid onset and offset of anxiety likely mediated by small-molecule neurotransmission. Here, we demonstrate persistent anxiety-like behavior generated by increasing the tonic activity of the neuromodulatory LC-NE system prior to anxiety testing (similar in timescale to restraint stress) as well as acute anxiety during increased LC-NE activity (control of assay-evoked anxiety). While this activity generates anxiety on a short timescale (seconds to minutes), it is unlikely that the immediate (subsecond timescale) result of high tonic activity is anxiety. Rather, it is plausible that the LC serves to integrate information from numerous forebrain and sensory inputs and, over time, the persistent high tonic state feeds forward onto previously established anxiety circuits serving to adjust the gain on these downstream systems to ultimately drive anxiety (Koob, 1999). The amygdala and extended amygdala are candidate regions where feed-forward, gain modulation could exist as there are reciprocal connections between the LC and divisions of the amygdala (Bouret et al., 2003; Buffalari and Grace, 2007) (Fig. S7D). Importantly, this model of LC modulation of anxiety circuitry is likely an endogenous mechanism given than the removal of the LC-NE system prevents stress-induced anxiety.

The optogenetic manipulation that incites anxiety also elicits aversive behaviors. These findings suggest that higher tonic frequencies potentially produce anxiety through negative affect. While it is generally thought that anxiety and aversion are both negative affective states, the two behavioral outputs can be neurobiologically distinct (Kim et al., 2013a; Land et al., 2008). This appears to be the case with the LC system. The anxiety-like and real-time aversive components of these behaviors appear to be mediated by different receptor systems (anxiety-like behavior through β-adrenergic receptors and real-time aversion through α-adrenergic receptors). A circuit-based mechanism for this segregation remains to be determined.

CRH+ CeA-LC terminals increase activity and drive anxiety through CRFR1 activation

Anatomical studies first identified the projection from the CeA to the LC (Van Bockstaele et al., 1996, 1998) and recent work has defined these projections to suggest that CeA-LC projections are potentially glutamatergic and carry the neuropeptides dynorphin and CRH (Reyes et al., 2008). Importantly, CRH+ CeA neurons have been shown to be a part of the protein kinase C δ− subpopulation of CeA neurons recently shown to be distinct from CeA neurons involved in conditioned fear and food consumption (Cai et al., 2014; Haubensak et al., 2010). This CRH+ projection into the LC has been of particular interest as a source of extrahypothalamic CRH that increases tonic LC firing during stress. The overall population of recorded LC neurons increase tonic firing during photostimulation of CRH+ CeA-LC terminals yet we did observe a complex array of responses. The diversity of responses could represent anatomical differentiation of LC neurons. It is possible that non-responding neurons do not receive innervation from the CeA or the local polysynaptic partners and the difference in responses could be explained by varied expression of cell-surface receptors on postsynaptic neurons. While the literature shows monosynaptic connections exist in this circuit (Reyes et al., 2008), none of our slice physiology or in vivo data suggest any fast-acting neurotransmission. While this could be due to the potential for selection bias inherent in in vivo recordings or an artifact of slower acting neuropeptide/G-protein coupled receptor-mediated transmission, we cannot rule out the a polysynaptic mechanism. It is important to note that spatially-isolated photostimulation of these terminals in the LC recapitulates the aversion and anxiety-like behaviors observed with both stress and direct LC photostimulation. Furthermore, the anxiety-like behavior can be reversed by either systemic or local antagonism of CRHR1 in the LC, suggesting that photostimulation-induced release of CRH mediates these behaviors through action in or very near the LC. While these experiments do not explicitly control for possible optogenetically-induced backpropagating action potentials, the anxiogenic to anxiolytic reversal by local CRHR1 blockade suggests the LC is likely a critical site of action for these behaviors.

Understanding how the vast efferent projection network of the LC facilitates anxiogenesis will be an important next step. We suspect that particular efferent LC-NE projections onto particular postsynaptic receptors likely mediate the observed behavioral outcomes. For example, the LC projects into the lateral septum and the basolateral amygdala, both of which play a key role in the regulation of stress and anxiety-like behaviors (Anthony et al., 2014; Felix-Ortiz et al., 2013; Tye et al., 2011). While the role of lateral septum (LS) neurons in prolonged stress-induced anxiety has been clearly demonstrated (Anthony et al., 2014), future work is needed to investigate whether known LC inputs into the LS (Risold and Swanson, 1997) modulate this system to produce prolonged anxiety. Additionally, the LC also has many known projections to other anxiogenic centers such as the basolateral amygdala and reciprocal projections back to the CeA (Bouret et al., 2003; Buffalari and Grace, 2007) meriting similar investigation (Fig. S7D). This circuit-based theory of LC function provides a framework towards understanding other LC functions including attention and arousal.

We report here that stress-induced increases in LC activity are critical for anxiety-like behavior, affirming the LC-NE system as a key mediator of the acute behavioral stress response. Taken together, this study provides fundamental framework for understanding the mammalian brain circuitry responsible for the innate anxiety response.

Experimental Procedures

Additional detailed methods provided in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Experimental subjects & Stereotaxic surgery

Adult (25–35 g) male C57BL/6J, TH-IRES-Cre, Crh-IRES-Cre, and Gal-Cre were group-housed, given access to food pellets and water ad libitum and maintained on a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM). All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University and conformed to US National Institutes of Health guidelines. For surgery, animals were anaesthetized in an induction chamber (4% Isolflurane) and placed in a stereotaxic frame where they were maintained at 1–2% isoflurane. Mice were injected with AAV5-DIO-HM4Di, AAV5-DIO-ChR2 or AAV5-DIO-eYFP, Fluorogold, or CTB-594 unilaterally into the LC (coordinates from bregma: −5.45 anterior-posterior (AP), +/−1.25 medial-lateral (ML), −4.00 mm dorsal-ventral (DV)), or the CeA (−1.25 AP, +/− 2.75 ML, −4.75 DV). Mice were then implanted with metal cannula or fiber optic implants (adjusted from viral injection 0.00 AP, +/− 0.25 ML, +1.00 DV) (Carter et al., 2010).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described (Al-Hasani et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013b).

Behavior

All behaviors were performed within a sound attenuated room maintained at 23°C at least one week after habituation to the holding room and the final surgery. Lighting was stabilized at ~250 lux for anxiety-like behaviors, ~1500 lux for aversion behaviors. Movements were video recorded and analyzed using Ethovision 8.5 (Noldus Information Technologies, Leesburg, VA).

Stress-induced anxiety paradigm

Mice were immobilized in modified disposable conical tubes once for 30 min and were then immediately transferred to the open field. For the hM4Di experiments, mice were injected with CNO (10 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min prior to restraint) (Vazey and Aston-Jones, 2014). For the CRF antagonism experiment, mice were injected with Antalarmin HCl (10 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min prior to restraint).

Open Field Test (OFT)

OFT testing was performed in a 2500 cm2 enclosure for 20 min (stress-induced or pre-stimulation experiments); center defined as a square of 50% the total OFT area. For acute optogenetic experiments, Th-CreLC:ChR2 or Th-CreLC:eYFP mice were allowed them to roam for 21 min. Photostimulation alternated off and on (5 Hz, 10 ms width, ~10 mW light power) in 3 min bins.

Elevated Zero Maze (EZM)

EZM testing was performed as described (Bruchas et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2013b). Th-Cre animals received 5 Hz (10 ms width) and Crh-Cre animals received 10 Hz (10 ms width) photostimulation (~10 mW light power). For the CRFR1 antagonism experiments, mice were infused into the LC with α-helical CRF (1 μg, intra-LC, 1 hr prior to behavior, Tocris) or Antalarmin HCl (10 mg/kg, i.p., 30 min prior to behavior, Sigma).

Conditioned Place Aversion

Mice were trained in an unbiased, balanced three-compartment conditioning apparatus as described (Bruchas et al., 2009; Al-Hasani et al., 2013; Land et al., 2008).

Real-time Place Testing

Animals were placed in a custom-made unbiased, balanced two-compartment conditioning apparatus (52.5 × 25.5 × 25.5 cm) as described previously (Siuda et al., 2015). During a 20 min trial, entry into one compartment triggered photostimulation of various frequencies (0, 1, 2, 5, 10 Hz, etc.) while the animal remained in the light-paired chamber and entry into the other chamber ended photostimulation.

Slice electrophysiology

Following anesthesia, horizontal midbrain slices containing the LC (240 μm) were cut in ice-cold cutting solution and incubated post-cutting at 35°C in oxygenated ACSF solution with 10 μM MK-801 for 45 min before recording. Following incubation, slices were placed in a recording chamber and perfused with ACSF (34 ± 2°C) containing 100 μM picrotoxin, 10 μM DNQX and 1 μM idazoxan at 2 ml/min. Whole-cell current-clamp recordings were made as described (Courtney and Ford, 2014). Widefield activation of ChR2 was activated with collimated light from a LED (470 nm, ~1 mW) through the 40x water immersion objective. Patch pipettes (1.5–2 MW) were pulled from borosilicate glass (World Precision Instruments). To examine synaptic events driven by optogenetic stimulation (3 ms pulses) of CRH terminals in the LC, recordings were made in the absence of synaptic receptor antagonists. To confirm that photostimulation of terminals arising from the CeA did not evoke measurable synaptic events, recordings were also made in a subset of trials (n = 5) in the presence of TTX (500 nM), 4-AP (100 μM) and antalarmin (10 μM). All solutions can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

In vivo electrophysiology

A 16-channel array (35-μm tungsten wires, 150-μm spacing between wires, 150-μm spacing between rows, Innovative Physiology) was epoxied to a fiber optic and lowered into the LC of a lightly (<1% isoflurane) anesthetized, Th-CreLC:ChR2 or Crh-CreCeA-LC:ChR2 animals. Voltages from each electrode were bandpass-filtered with activity between 250 and 8,000 Hz analyzed as spikes. LC cells were selected based on stereotaxic position, baseline activity, and toe pinch response. The signal was amplified and digitally converted (Omniplex and PlexControl, Plexon), spikes were sorted using principal component analysis and/or evaluation of t-distribution with expectation maximization (Offline sorter, Plexon). Sorted units were analyzed with NeuroExplorer 3.0 and timestamps were exported for further analysis in Microsoft Excel and Matlab 7.12.

Data Analysis/Statistics

All data expressed as mean ± SEM. In data that were normally distributed, differences between groups were determined using independent t-tests or one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVAs followed by post hoc comparisons if the main effect was significant at p<0.05. In cases where data failed the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test, non-parametric analyses were used. Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIDA R21 DA035144 (M.R.B.), McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience (M.R.B.), NIDA R01 DA035821 (C.P.F.), NIMH F31 MH101956 (J.G.M.), NIDA K99 DA038725 (R.A.), and WUSTL DBBS (J.G.M.). We thank the Bruchas Laboratory, in particular Blessan Sebastian, William Planer, Audra Foshage and Lamley Lawson, for helpful insight, discussion, and technical support. We especially thank Robert W. Gereau, IV, Erik D. Herzog, Timothy E. Holy, Joseph D. Dougherty, and Vijay K. Samineni for helpful discussion. We thank Karl Deisseroth (Stanford) for the channelrhodopsin-2 (H134) construct, Garret Stuber (UNC) for the Th-IRES-Cre mice and Max Kelz (Penn) for the Gal-Cre mice. We also thank The WUSTL HOPE Center viral vector core (NINDS, P30NS057105) and Bakewell Neuroimaging Laboratory.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.M. and M.R.B.; Methodology, J.G.M. R.A., E.R.S.,C.P.F., and M.R.B.; Investigation, J.G.M., C.P.F., R.A., E.R.S., D.Y.H., and A.J.N. Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing, J.G.M. and M.R.B.; Funding acquisition, M.R.B.; Supervision, C.P.F.; Project administration, M.R.B.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez VA, Chow CC, Van Bockstaele EJ, Williams JT. Frequency-dependent synchrony in locus ceruleus: role of electrotonic coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4032–4036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062716299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony T, Dee N, Bernard A, Lerchner W, Heintz N, Anderson D. Control of Stress-Induced Persistent Anxiety by an Extra-Amygdala Septohypothalamic Circuit. Cell. 2014;156:522–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1981a;1:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats exhibit pronounced responses to non-noxious environmental stimuli. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1981b;1:887–900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00887.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Cohen J. Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1309–1320. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister K, Bee LA, Dickenson AH. Preclinical and early clinical investigations related to monoaminergic pain modulation. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2009;6:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham B, McFadden K, Zhang X, Bhatnagar S, Beck S, Valentino R. Early adolescence as a critical window during which social stress distinctly alters behavior and brain norepinephrine activity. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;36:896–909. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Chan J, Pickel VM. Input from central nucleus of the amygdala efferents to pericoerulear dendrites, some of which contain tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity. J Neurosci Res. 1996;45:289–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960801)45:3<289::AID-JNR11>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bockstaele EJ, Colago EE, Valentino RJ. Amygdaloid corticotropin-releasing factor targets locus coeruleus dendrites: substrate for the coordination of emotional and cognitive limbs of the stress response. J Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:743–757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouret S, Duvel A, Onat S, Sara SJ. Phasic activation of locus ceruleus neurons by the central nucleus of the amygdala. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2003;23:3491–3497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03491.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Land BB, Lemos JC, Chavkin C. CRF1-R activation of the dynorphin/kappa opioid system in the mouse basolateral amygdala mediates anxiety-like behavior. PloS One. 2009;4:e8528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, Grace AA. Noradrenergic modulation of basolateral amygdala neuronal activity: opposing influences of alpha-2 and beta receptor activation. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2007;27:12358–12366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2007-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Haubensak W, Anthony TE, Anderson DJ. Central amygdala PKC-δ+ neurons mediate the influence of multiple anorexigenic signals. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1240–1248. doi: 10.1038/nn.3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter ME, Yizhar O, Chikahisa S, Nguyen H, Adamantidis A, Nishino S, Deisseroth K, de Lecea L. Tuning arousal with optogenetic modulation of locus coeruleus neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/nn.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter ME, Brill J, Bonnavion P, Huguenard JR, Huerta R, de Lecea L. Mechanism for Hypocretin-mediated sleep-to-wake transitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2635–E2644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202526109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassens G, Kuruc A, Roffman M, Orsulak PJ, Schildkraut JJ. Alterations in brain norepinephrine metabolism and behavior induced by environmental stimuli previously paired with inescapable shock. Behav Brain Res. 1981;2:387–407. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(81)90020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciocchi S, Herry C, Grenier F, Wolff SBE, Letzkus JJ, Vlachos I, Ehrlich I, Sprengel R, Deisseroth K, Stadler MB, et al. Encoding of conditioned fear in central amygdala inhibitory circuits. Nature. 2010;468:277–282. doi: 10.1038/nature09559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte WL, Kamishina H, Reep RL. Multiple neuroanatomical tract-tracing using fluorescent Alexa Fluor conjugates of cholera toxin subunit B in rats. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1157–1166. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney NA, Ford CP. The timing of dopamine- and noradrenaline-mediated transmission reflects underlying differences in the extent of spillover and pooling. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2014;34:7645–7656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0166-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis aL, Lechner SM, Pavcovich La, Valentino RJ. Activation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system by intracoerulear microinfusion of corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on discharge rate, cortical norepinephrine levels and cortical electroencephalographic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis AL, Leiser SC, Snyder K, Valentino RJ. Predator stress engages corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid systems to alter the operating mode of locus coeruleus norepinephrine neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1737–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov EL, Yanagawa Y, Usdin TB. Forebrain GABAergic projections to locus coeruleus in mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:2373–2397. doi: 10.1002/cne.23291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz AC, Beyeler A, Seo C, Leppla CA, Wildes CP, Tye KM. BLA to vHPC inputs modulate anxiety-related behaviors. Neuron. 2013;79:658–664. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote SL, Aston-Jones G, Bloom FE. Impulse activity of locus coeruleus neurons in awake rats and monkeys is a function of sensory stimulation and arousal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:3033–3037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DD, Caldji C, Champagne F, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor–norepinephrine systems in mediating the effects of early experience on the development of behavioral and endocrine responses to stress. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafford GM, Guo J-D, Flandreau EI, Hazra R, Rainnie DG, Ressler KJ. Cell-type specific deletion of GABA(A)α1 in corticotropin-releasing factor-containing neurons enhances anxiety and disrupts fear extinction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16330–16335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119261109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, Losos K, Didkovsky N, Schambra UB, Nowak NJ, Joyner A, Leblanc G, Hatten ME, et al. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hasani R, McCall JG, Foshage AM, Bruchas MR. Locus Coeruleus Kappa Opioid Receptors modulate Reinstatement of Cocaine Place Preference through a Noradrenergic Mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubensak W, Kunwar PS, Cai H, Ciocchi S, Wall NR, Ponnusamy R, Biag J, Dong HW, Deisseroth K, Callaway EM, et al. Genetic dissection of an amygdala microcircuit that gates conditioned fear. Nature. 2010;468:270–276. doi: 10.1038/nature09553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Pich EM, Baldwin HA, Rassnick S, Britton KT, Koob GF. Anti-stress action of a corticotropin-releasing factor antagonist on behavioral reactivity to stressors of varying type and intensity. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 1994;11:179–186. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1380104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heydendael W, Sengupta A, Beck S, Bhatnagar S. Optogenetic examination identifies a context-specific role for orexins/hypocretins in anxiety-related behavior. Physiol Behav. 2014;130:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey L, Li Y, Fyson SJ, Watson TC, Perrins R, Hewinson J, Teschemacher AG, Furue H, Lumb BM, Pickering AE. Optoactivation of locus ceruleus neurons evokes bidirectional changes in thermal nociception in rats. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2014;34:4148–4160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4835-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holets VR, Hökfelt T, Rökaeus Å, Terenius L, Goldstein M. Locus coeruleus neurons in the rat containing neuropeptide Y, tyrosine hydroxylase or galanin and their efferent projections to the spinal cord, cerebral cortex and hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 1988;24:893–906. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedema HP, Grace AA. Corticotropin-releasing hormone directly activates noradrenergic neurons of the locus ceruleus recorded in vitro. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2004;24:9703–9713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2830-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JH, Sparta DR, Stamatakis AM, Ung RL, Pleil KE, Kash TL, Stuber GD. Distinct extended amygdala circuits for divergent motivational states. Nature. 2013;496:224–228. doi: 10.1038/nature12041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek MA, Drew LJ, Burghardt NS, Costantini DO, Tannenholz L, Ahmari SE, Zeng H, Fenton AA, Hen R. Differential control of learning and anxiety along the dorsoventral axis of the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2013;77:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Adhikari A, Lee SY, Marshel JH, Kim CK, Mallory CS, Lo M, Pak S, Mattis J, Lim BK, et al. Diverging neural pathways assemble a behavioural state from separable features in anxiety. Nature. 2013a;496:219–223. doi: 10.1038/nature12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T, McCall JG, Jung YH, Huang X, Siuda ER, Li Y, Song J, Song YM, Pao HA, Kim RH, et al. Injectable, Cellular-Scale Optoelectronics with Applications for Wireless Optogenetics. Science. 2013b;340:211–216. doi: 10.1126/science.1232437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konturek PC, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol Off J Pol Physiol Soc. 2011;62:591–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1167–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, Chavkin C. The dysphoric component of stress is encoded by activation of the dynorphin kappa-opioid system. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2008;28:407–414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, Boe AF, Boguski MS, Brockway KS, Byrnes EJ, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melander T, Hökfelt T, Rökaeus A. Distribution of galaninlike immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1986;248:475–517. doi: 10.1002/cne.902480404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Karimian SM, Hajimashhadi Z, Riahi E, Ghasemi T. Attenuation of morphine withdrawal signs by muscimol in the locus coeruleus of rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:171–175. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282fe8849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neophytou SI, Aspley S, Butler S, Beckett S, Marsden CA. Effects of lesioning noradrenergic neurones in the locus coeruleus on conditioned and unconditioned aversive behaviour in the rat. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001;25:1307–1321. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson VG, Rockett HR, Reh RK, Redila VA, Tran PM, Venkov HA, DeFino MC, Hague C, Peskind ER, Szot P, et al. The Role of Norepinephrine in Differential Response to Stress in an Animal Model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Abercrombie ED. Discrete local application of corticotropin-releasing factor increases locus coeruleus discharge and extracellular norepinephrine in rat hippocampus. Synap N Y N. 1999;33:304–313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990915)33:4<304::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passerin AM, Cano G, Rabin BS, Delano BA, Napier JL, Sved AF. Role of locus coeruleus in foot shock-evoked Fos expression in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:1071–1082. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, Hoff DJ, Hart K, Holmes H, Homas D, Hill J, Daniels C, Calohan J, et al. A Trial of Prazosin for Combat Trauma PTSD With Nightmares in Active-Duty Soldiers Returned From Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1003–1010. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12081133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes Ba S, Drolet G, Van Bockstaele EJ. Dynorphin and stress-related peptides in rat locus coeruleus: contribution of amygdalar efferents. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:663–675. doi: 10.1002/cne.21683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risold PY, Swanson LW. Chemoarchitecture of the rat lateral septal nucleus. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;24:91–113. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara SJ, Bouret S. Orienting and reorienting: the locus coeruleus mediates cognition through arousal. Neuron. 2012;76:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Highfield D, Delfs J, Leung S, Stewart J. Clonidine blocks stress-induced reinstatement of heroin seeking in rats: an effect independent of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:292–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuda ER, Copits BA, Schmidt MJ, Baird MA, Al-Hasani R, Planer WJ, Funderburk SC, McCall JG, Gereau RW, IV, Bruchas MR. Spatiotemporal Control of Opioid Signaling and Behavior. Neuron. 2015;86:923–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder K, Wang W-W, Han R, McFadden K, Valentino RJ. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the norepinephrine nucleus, locus coeruleus, facilitates behavioral flexibility. Neuropsychopharmacol Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;37:520–530. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis AM, Stuber GD. Activation of lateral habenula inputs to the ventral midbrain promotes behavioral avoidance. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1105–1107. doi: 10.1038/nn.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KR, Yvon C, Turiault M, Mirzabekov JJ, Doehner J, Labouèbe G, Deisseroth K, Tye KM, Lüscher C. GABA neurons of the VTA drive conditioned place aversion. Neuron. 2012;73:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsiani D, Kvitsani D, Fu Y, Lu J, et al. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervo DGR, Proskurin M, Manakov M, Kabra M, Vollmer A, Branson K, Karpova AY. Behavioral Variability through Stochastic Choice and Its Gating by Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Cell. 2014;159:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye KM, Prakash R, Kim SY, Fenno LE, Grosenick L, Zarabi H, Thompson KR, Gradinaru V, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K. Amygdala circuitry mediating reversible and bidirectional control of anxiety. Nature. 2011;471:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature09820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele E. Convergent regulation of locus coeruleus activity as an adaptive response to stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Foote SL. Corticotropin-releasing hormone increases tonic but not sensory-evoked activity of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons in unanesthetized rats. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 1988;8:1016–1025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-01016.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Page ME, Curtis aL. Activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons by hemodynamic stress is due to local release of corticotropin-releasing factor. Brain Res. 1991;555:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90855-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazey EM, Aston-Jones G. Designer receptor manipulations reveal a role of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system in isoflurane general anesthesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:3859–3864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veinante P, Freund-Mercier M-J. Intrinsic and extrinsic connections of the rat central extended amygdala: an in vivo electrophysiological study of the central amygdaloid nucleus. Brain Res. 1998;794:188–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Autry AE, Bergan JF, Watabe-Uchida M, Dulac CG. Galanin neurons in the medial preoptic area govern parental behaviour. Nature. 2014;509:325–330. doi: 10.1038/nature13307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.