Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine the role of ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric patients with acute abdominal pain caused by intussusceptions.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective study of all pediatric patients with acute abdominal pain caused by intussusceptions and that underwent ultrasound examination at the emergency service of the Radiology Department between November 2007 and June 2013. The role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of intussusceptions has been assessed by comparing the echographic presumptive diagnosis with the final diagnosis of discharge. Its importance in the treatment has been assessed by determining the value of ultrasound findings in the choice of the best treatment.

Results

The ultrasound examination was positive in 16/18 patients with a final diagnosis of intussusception. Some sonographic findings seemed to be able to predict the opportunity to resort to non-surgical therapeutic options like hydrostatic or pneumatic reduction of the intestinal segments invaginated. In our casuistry, five children presented characteristics typical of this subgroup and underwent barium enema which provided the reduction of the intestinal segments involved. The future challenge will be to perform non-surgical ultrasound-guided reductions to avoid the exposure of the infants to ionizing radiations.

Conclusions

Ultrasonography is essential not only in the diagnosis, but also it adds important elements in the therapeutic choice and could play in the future an important role in non-surgical reduction of intestinal intussusceptions in pediatric patients.

Keywords: Intussusception, Childhood, Sonography

Riassunto

Obiettivo

Accertare il ruolo dell'ecografia nella diagnosi e trattamento dei pazienti pediatrici con dolore addominale acuto causato da invaginazione intestinale.

Materiali e metodi

Abbiamo eseguito uno studio retrospettivo su tutti i pazienti pediatrici con dolore addominale acuto causato da intussuscezione e sottoposti ad esame ecografico presso il servizio di emergenza del Dipartimento di Radiologia tra il Novembre 2007 ed il Giugno 2013. Il ruolo dell'ecografia nella diagnosi di intussuscezione è stato valutato comparando la diagnosi presuntiva ecografica con la diagnosi finale di dimissione; per ciò che concerne la sua importanza nel trattamento, ci si è basati sull'influenza dei reperti ecografici sul percorso terapeutico.

Risultati

Su 18 pazienti con diagnosi finale di intussuscezione l'esame ecografico è risultato positivo in 16 casi; inoltre è stato possibile osservare che alcuni reperti ecografici sembrano essere in grado di predire l'opportunità di ricorrere ad opzioni terapeutiche non chirurgiche, vale a dire riduzione idrostatica o pneumatica del segmento intestinale invaginato. Nella nostra casistica, 5 bambini hanno presentato caratteristiche tali da rientrare in questo sottogruppo, e pertanto sono stati sottoposti a clisma opaco, tramite cui in 3 casi si è ottenuto lo svaginamento dei segmenti intestinali. La sfida futura sarà sottoporre questo sottogruppo di pazienti a riduzione non chirurgica sotto guida ecografica, evitando così l'esposizione del bambino a radiazioni ionizzanti.

Conclusioni

l'ecografia risulta fondamentale non solo nella fase diagnostica, ma aggiunge elementi di peso nella decisione terapeutica e potrebbe rivestire, in futuro, un ruolo di primo piano in qualità di guida nella riduzione non chirurgica dell'invaginazione intestinale nel paziente pediatrico.

Introduction

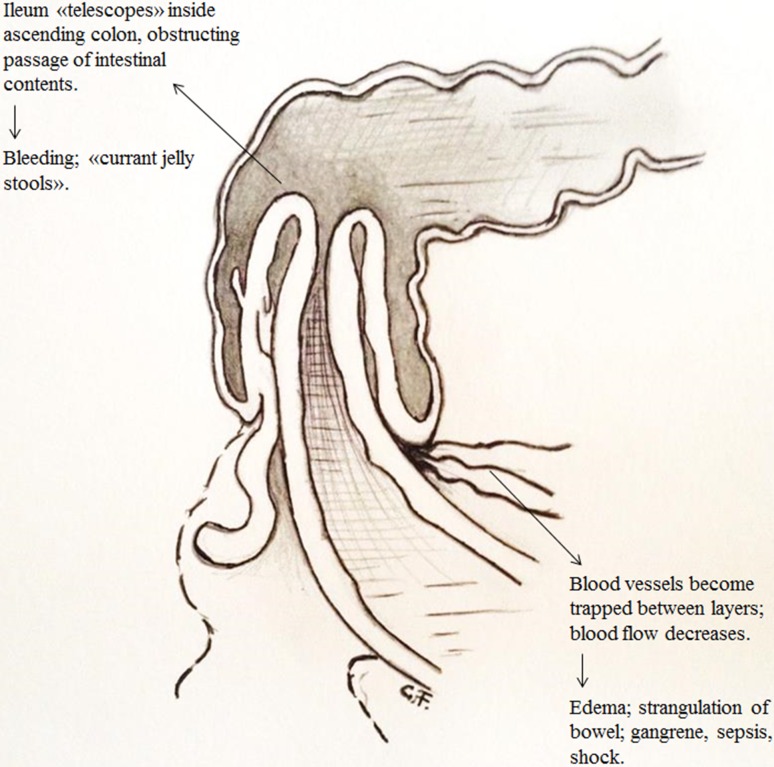

Intussusception is the process in which a portion of the intestine telescopes into itself. It is the most common cause of gastrointestinal obstruction in children, occurring most commonly between 3 and 12 months of age, and the most common type of bowel invagination is the ileocolic one. Since an unreduced intussusception can potentially cause bowel obstruction and mesenteric vascular compromise leading to bowel ischemia/necrosis, early diagnosis and treatment of this disease are very important (Fig. 1) [1–3]. The pathogenesis of intussusception is in approximately 90 % of cases idiopathic and is assumed to be secondary to uncoordinated peristalsis of the gut or to lymphoid hyperplasia, which may be due to a recent GI infection [4–9]. Approximately 5–6 % of intussusceptions in children have pathologic lead points (PLP) which are due to either focal masses or diffuse bowel wall abnormality. The most common focal PLPs are (in decreasing order of incidence) Meckel’s diverticulum, duplication cyst, polyp, and lymphoma. Diffuse PLPs are most commonly associated with cystic fibrosis or Henoch–Schonlein Purpura [1, 2, 10–12]. The “classic” clinical triad has been described as consisting of (a) acute colicky abdominal pain, (b) “currant jelly” or frankly bloody stools, and (c) either a palpable abdominal mass or vomiting. Many children do not present the complete triad of symptoms and in some cases intussusception may be transient with spontaneously reduction [3, 7, 13, 14].

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the most common (idiopathic, ileocolic) types of intussusception

Imagistic investigations are very important for a prompt and accurate diagnosis; if there is a high clinical suspicion of intussusception, especially when there are two or more of the cardinal symptoms, US should be the initial imaging procedure [15–18]. In a recent study of Hryhorczuk et al., the overall sensitivity of US for detecting intussusception was 97.9 % and specificity was 97.8 %; the positive predictive value of the test was 86.6 % and the negative predictive value was 99.7 % [7, 18]. The superior performance of US in the diagnosis of intussusception, the high level of patient comfort and safety allowed by US and the ability to arrive at alternative diagnoses with US has led to reserve enemas only for therapeutic purposes. When the symptoms are vague, it would be reasonable to perform also a plain radiography [17], but its sensitivity in detecting intussusception is as low as 45 % [14].

The aim of our retrospective study is to assess the impact of ultrasonography on diagnosis and treatment of pediatric patients with intussusception.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective study in 18 patients aged <10 with acute abdominal pain who underwent US of the abdomen at the emergencies service of our Department of Diagnostic Imaging from November 2007 to June 2013 and that were discharged from Pediatric Surgery Department with final diagnosis of intussusception. All the procedures in our hospital were performed according to the World Medical Association Declaration from Helsinki. All the patients’ parents were informed about the US examination procedures and the surgical procedures. Oral consent was obtained for US examinations and written informed consent was obtained before surgery. We excluded from our study patients initially evaluated by US in other hospitals and then transferred to our Emergency Department.

As initial imaging procedure, patients with clinical suspicion of intussusception underwent to trans-abdominal ultrasound examination; patients with acute abdominal pain of unknown origin underwent a plain radiography of the abdomen in addition to the trans-abdominal ultrasound examination.

US examination was performed by a general radiologist using the same ultrasound scanner (TOSHIBA Aplio 500). After screening the solid abdominal organs using a convex transducer (5 MHz), a 10-MHz linear transducers was then used for the detailed evaluation of the bowel and the mesentery. Color-coded Doppler examination was performed in all patients. Color Doppler imaging was optimized for a low flow rate with the gain set at the highest possible overall level, while the noise was kept to a minimum.

The presumptive ecographic diagnosis of intussusception was made by finding pathognomonic signs such as “donut-like”, “bowel-within-bowel” or “pseudo-kidney” images. The presumptive plain radiography diagnosis was made by recognizing the “crescent-sign” (curvilinear mass within the course of the colon, usually located near the hepatic flexure) [1].

For all patients included in our study we investigated retrospectively, in collaboration with the physicians of Pediatric Surgery Department, the clinical pathway after the US examination (surgical or not surgical treatment) and the definitive diagnosis obtained from the discharge notes. The role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of intussusceptions was evaluated by comparing the ultrasound presumptive diagnosis with the final diagnosis of discharge. The importance of the ultrasound findings in the therapeutic course was assessed by the influence of some of them in the decision to perform non-surgical attempt to reduce the invaginated intestinal segment with a barium enema.

Results

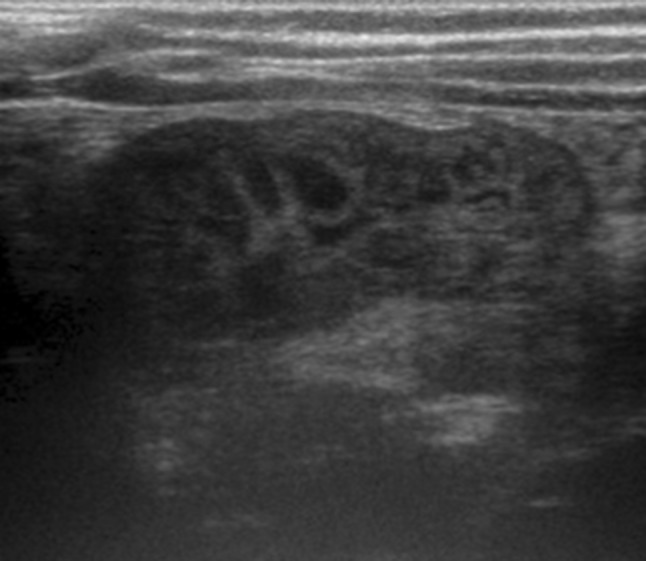

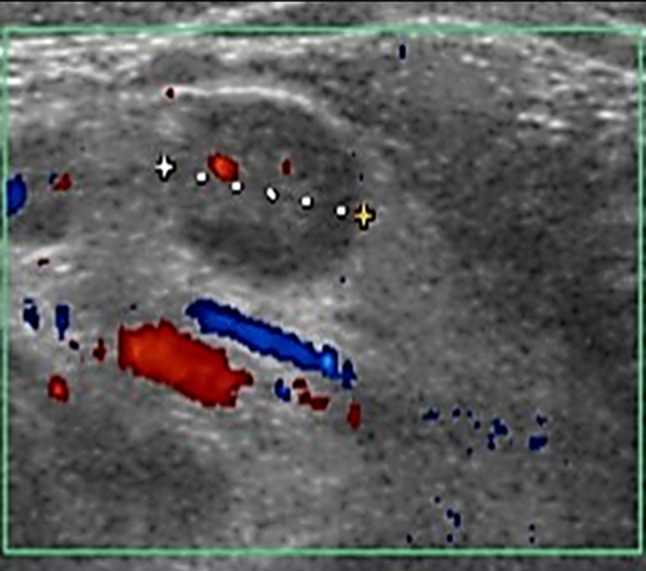

The total number of patients whose US examinations were retrospectively evaluated was 18 (10 females, 8 males, aged between 1 and 10 years, with a mean age of 3.8 years). Ultrasonography gave a presumptive diagnosis of intussusception in 16/18 cases (in 5/6 patients with a clinical suspicion and in 11/12 patients with acute abdominal pain of unknown origin). The most important signs were the finding of an abdominal mass formed by alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic concentric layers with “donut-like” aspect at transverse scans (Fig. 2), “intestine-within-intestine” aspect at longitudinal scans and “pseudo-kidney” in the oblique scans (Fig. 3) [14, 18]. The location of the suspected intussusception was the right abdomen in 11 patients, left abdomen in 3 and the paraumbilical region in 2. The outer diameter ranged between 2.5 and 5 cm (mean 3.6 ± 0.5 cm, range 2.5–5 cm). The blood flow signal appeared on color Doppler images in 12 patients (Fig. 4); the other 4 patients without blood flow showed fluid retention between the two loops involved in the intussusception (Fig. 5). Free fluid collection was not noted in five patients. When a specific leading cause was not found, enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes with diameter maximum between 10 and 15 mm were seen in five patients (Fig. 6). In the remaining 2/18 cases, the ultrasound examination was negative (1/6 with a clinical suspicion, 1/12 with acute abdominal pain of unknown origin).

Fig. 2.

Short-axis US image shows the target (donut) sign

Fig. 3.

Oblique US image shows the pseudo-kidney sign, which results when the intussusception is curved or is imaged obliquely

Fig. 4.

Longitudinal color Doppler US image shows a complex mass within creased color signal centrally and within congested vessels in the walls of the intussuscepted loop of terminal ileum

Fig. 5.

Short-axis US image shows fluid retention between the walls of invaginated bowel

Fig. 6.

Longitudinal color Doppler US image demonstrates multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the right lower quadrant

In the 12 patients who underwent the plain radiography of the abdomen in addiction to the ultrasound, it was not possible to do a presumptive diagnosis of intussusception, possible only thought the “crescent-sign” [14]. In 11/12 patients plain radiography of the abdomen appeared completely negative despite the positive ultrasound examination; only in one patient, with a negative ultrasound examination, presumptive radiographic signs of intussusception were documented, such as altered distribution of gas in the small intestine characterized by gaseous distension of the intestinal loops and almost complete absence of air in the ascending colon [1].

5/16 children with sonographic presumptive diagnosis of intussusception were selectively sent to perform a barium enema, in order to confirm the diagnosis and to try a non-surgical reduction of the invaginated segment. In fact, as in agreement with literature [17], these five patients showed all the following clinical and ultrasound features indicative of a reduced risk of perforation: aged 3 months to 5 years, duration of lower abdominal symptoms less than 48 h from the instrumental diagnosis, absence of dehydration signs, shock, peritonitis and ultrasound picture documenting, at the same time, the presence of color Doppler flow in the intestinal wall of the outer and the inner segment and absence of peritoneal fluid between the loops involved.

In all the five cases, the barium enema documented the intussusceptions by recognizing the “meniscus sign” (Fig. 7) [17]. Only in three cases the barium enema reached a therapeutic effect with reduction of the intussusceptions, colo-colic in one case and ileo-colic in the other; in the other two cases it was used a surgical reduction, with ileo-colic intussusception resolution through manual reduction and evidence of lead point in 1 case (small intestine’s polyp that was resected during the surgery).

Fig. 7.

Barium enema study shows the “meniscus sign” in the contrast material-filled distal colon

The other 12 cases with presumptive sonographic diagnosis of intussusception were made directly in the operating room and in particular: 2/12 case underwent a manual reduction of the invaginated segment located in the ascending colon; 5/12 cases underwent a resection of the invaginated intestinal tract, in particular of an ileal tract, since those case were ileo-colic intussusception (Fig. 8); in 5/12 cases laparotomy showed no macroscopically evident signs of intussusception, therefore, were classified as cases of transient intussusception, including a patient with S. Henoch purpura.

Fig. 8.

Intraoperative photo shows ileo-colic intussusception

In the two cases with a negative ultrasound examination, since there was a strong clinical suspicion of intussusception, it was performed a barium enema which documented intussusception, but it did not allow the non-surgical reduction so the Patient underwent surgery with manual reduction of ileus-cecal-colic intussusception. The other Patient, who showed vague symptoms and a plain radiography documenting an altered distribution of intestinal gas, underwent laparotomy which revealed the ileo-ileal intussusception and underwent manual resolution and resection of the lead point (Meckel’s diverticulum).

Summarizing all 18 patients were discharged from the Department of Pediatric Surgery in good condition with no post-operative complications and a definitive diagnosis of intussusception, which was readily recognized by the survey initial ultrasound in 16 cases. Furthermore, the detection of some sonographic findings, such as the simultaneous presence of color Doppler vascular signals and the absence of fluid trapped between the loops involved, allowed the correct selection of five patients deserving of non-surgical reduction, with positive outcome in three cases.

Discussion

Intussusception represents one of the most common abdominal emergency in infancy. The classical clinical triad, consisting of abdominal colics, red jelly stools and a palpable mass, is present only in approximately 50 % of cases, 20 % of patients are symptoms-free at clinical presentation [7]. In our series presumptive ultrasonographic diagnoses of intussusception were made by identifying, in 16/18 patients with acute abdominal pain (5/18 with a clinical suspicion of intussusception), an abdominal mass located in most cases in the right abdominal quadrants and appearing as a “donut”, a bowel-in-bowel or “pseudo-kidney” image [18]. Presumptive US diagnosis of intussusception was later confirmed in all 16 cases, as documented by discharge notes, substantiating Literature data and consolidating the primary role of US not only in the management of little patient with a strong clinical suspect of intussusception, but also in those cases of acute but aspecific abdominal pain, where conversely the use of plain radiographs did not add any useful element to orientate the diagnosis but was only able to exclude the presence of perforation or occlusion.

A correct execution of US examination in the evaluation of intussusception provides a qualified and adequate measurement of both longitudinal and axial diameters of suspected invaginated bowels. This information correlates with gravity and so with prognosis of intussusception, as also described by some Authors, for example by Munden et al. that in their series found that length of intussusception was the most useful independent predictor of the need of surgical intervention and concluded that when small-bowel intussusception is detected in infants and children undergoing abdominal sonography, intussusception length greater than 3.5 cm is a strong independent predictor of the need of surgical intervention [19]. In the opinion of these Authors, transitory intussusception tends to have smaller both axial and longitudinal diameters compared to cases of nearly irreducible intussusception, in which diameters should be greater.

Our study confirmed this information since five of our cases, finally discharged with a diagnosis of transitory intussusception, had their average axial diameter, measured by US, lower than the others while all of our surgically treated cases showed a larger axial diameter. These data could be helpful in daily US practice, even if a larger number of cases are required to verify these results [16]. A correct execution of US examination requires a careful search of PLP, even if their identification in children remains a diagnostic challenge for both clinicians and radiologists because of the varied and often non specific presentations and the wide spectrum of types of PLP. The incidence of PLP in intussusceptions is quite low, occurring only in 1.5–12 % of children [10–12]. Navarro et al. [10] found that imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis of PLP as from their series it is evident how US is the cornerstone modality in this regard, while plain radiographs of the abdomen do not play any role in identifying PLP. On US it is sometimes possible to recognize Merckel Diverticulum as a bulbous, elongated or tear-drop shaped mass at the distal end of the intussusceptum lying within the intussuscipiens or lymphoma as a lobulated hypoechoic mass in the intussusceptum [10, 20–23]. However, US did not depict any PLP in our series even if in two of our patients a PLP was certainly identified at surgical intervention (one case a Merckel Diverticulum and one case a tenual polyp). However, in five patients we found enlarged nodes near the mass suspected to be an intussusception according to the popular theory that suggests that there is a primary lymphoid hyperplasia in the distal small intestine secondary to infective agents, especially viruses, and that some of these enlarged lymph nodes aggregates or hypertrophied Peyer patches become entrapped in the intestine, serving as lead points for the intussusception [6, 7].

A correct execution of US examination also requires a careful search for abdominal fluid, as free peritoneal fluid or localized near interested bowels, also known as the “trapped-fluid sign”, caused by trapped fluid between the serosal surfaces of intussuscepted loops [17]. As also reported by Literature, the identification of free endo-peritoneal fluid does not necessarily indicate the presence of complications such as peritonitis or perforations, while the occurence of fluid “trapped” between intussuscepted bowel segments, that can be observed in less than 15 % of cases, seems to correlate with a lower reduction rate [17, 24] and has been described as a highly predictive sign of bowel necrosis [18]. In our study we found the presence of free endo-abdominal fluid in five patients, all of these submitted to surgery. In four of these these cases there was not evidence of intussuscepted bowels at surgery, classified, for this reason, as transitory intussusception; the other patient required bowel resection and primary anastomosis. However, all these five cases did not show complications such as perforation or peritonitis at surgery. On the contrary we documented the presence of “trapped” fluid between involved bowel in other four patients, all of them subsequently submitted to surgical resection because of the evidence at surgery of necrotic bowel. Also those data seem to confirm what Literature has previously reported.

A correct execution of US examination includes the use of color-Doppler that is able to identify the presence/absence of vascular signs in the walls of involved bowel. However, as also suggested by Literature, the presence of vascular signs cannot certainly exclude the ischemia/necrosis of intestinal walls involved. This datum has been confirmed by our study and in one of our cases in which US documented the presence of vascular signs, the little patient subsequently underwent surgery with resection of involved bowel, almost necrotic. On the contrary, the absence of vascular signs at color-Doppler is a more specific ultrasonographic sign of intestinal necrosis. In our series, all four patients with lack of vascular signs in involved bowel walls were correctly submitted to surgery, which confirmed the presence of necrosis in all of them, who underwent to intestinal resection [25, 26]. In these four patients there was the coexisting evidence of “trapped” fluid between involved bowel. For these two reasons none of these four patients has been considered for non-surgical treatment. According to Literature, our study underlines that the presence of vascular signs and the absence of “trapped” fluid between involved bowel are together the main ultrasonographic findings to look for, in association with clinical criteria, in discriminating between patients who are eligible for a non-surgical hydrostatic and pneumatic reductions.

Non-surgical reduction of intussusception is generally made under fluoroscopic guidance [27–30], even if US-guided reduction may represent in the future a valid alternative to fluoroscopy as a less invasive guide in non-surgical reduction of intussusception, avoiding exposition to ionizing radiations of little patients. The best studies about the use of US guide in intussusception reduction come from Asia, but nowadays also Europe is considering this technique. The procedure can be performed with water or with saline solution; some studies demonstrated an high probability of successful reduction (75–95 %) with low rate of complications (1 case of perforation on 825 reported cases). Worst results came from pneumatic US-guided reduction.

Summarizing, in children with acute abdominal pain and a strong suspect of intussusception the primary imaging modality of choice is ultrasound scanning, with a sensitivity of 98–100 %, a specificity of 88–97.8 % and a negative predictive value of 100 % [7, 31–34]. US has also a role in therapeutic decision. However, US still shows several limits: for example US is not able to depict most of PLP or distinguish ileo-ileal from ileo-colic intussusception (this distinction is very important because ileo-ileal intussusception are more difficult to be reduced radiologically and also have a higher incidence of PLP) [11]. Another great limit is linked to the experience of the US-operator, who can easily miss small and important signs of intussusception.

Conclusions

US showed great accuracy and sensibility in the diagnosis of intussusception. It can add important elements that the physicians can use to make the right choice of treatment. Moreover sonography is affirming as a safe guidance tool, in place of fluoroscopy, for hydrostatic or pneumatic non-surgical reduction of children intussusception. Even if this role is still not well diffuse and well supported by large scale studies it could be an interesting way to prevent the exposure of children to radiations. In the present study we found that some US findings are consistent with surgical results and clinical outcomes that make us confident to suggest an US examination of the abdomen in all the pediatric patients clinically suspected to have intussusception.

Conflict of interest

M. Bartocci, G. Fabrizi, I. Valente, C. Manzoni, S. Speca, L. Bonomo declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal studies

The study described in this article does not contain studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Mandeville K, Chien M, Anthony Willyerd F, et al. Intussusception: clinical presentations and imaging characteristics. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(9):842–844. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318267a75e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Applegate KE. Intussusception in children: evidence-based diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(Suppl 2):S140–S143. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1178-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JH (2004) US features of transient small bowel. Intussusception in pediatric patients. Korean J Radiol 5(3):178–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hryhorczuk AL, Lee EY. Imaging evaluation of bowel obstruction in children: updates in imaging techniques and review of imaging findings. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47(2):159–170. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Csernia T, Parana S, Puria P. New hypothesis on the pathogenesis of ileocecal intussusceptions. J Pediatric Surg. 2007;42(9):1515–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell TM, Steyn JH. Viruses in lymph nodes of children with mesenteric adenitis and intussusception. Br Med J. 1962;2(5306):700–702. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5306.700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorantin E, Lindbichler F. Management of intussusception. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(Suppl 4):L146–L154. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer TK, Bihrmann K, Perch M, et al. Intussusception in early childhood: a cohort study of 1.7 million children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):782–785. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okimoto S, Hyodo S, Yamamoto M, et al. Association of viral isolates from stool samples with intussusception in children. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(9):e641–e645. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarro O, Dugougeat F, Komecki A, et al. The impact of imaging in the management of intussusception owing to pathologic lead points in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30(9):594–603. doi: 10.1007/s002470000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timothy N Rogers Andrew Robb. Intussusception in infants and young children. Surgery 2010 August; 28: 402-405

- 12.Hryhorczuk AL, Lee EY. Imaging evaluation of bowel obstruction in children: updates in imaging techniques and review of imaging findings. Semin Roentgenol. 2012;47(2):159–170. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua JHY, Chan HC, Jacobsen AS (2006) Role of surgery in the era of highly successful air enema reduction of intussusception. Asian J surg 29(4):267–273 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Cogley JR, O’Connor SC, Houshyar R, et al. Emergent pediatric US: what every radiologist should know. RSNA. 2012;32(3):651–665. doi: 10.1148/rg.323115111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.B-Osamu D, Koji A, Hutson JM (2004) Twenty-one cases of small bowel intussusception: the pathophysiology of idiopathic intussusception and the concept of benign small bowel intussusceptions. Pediatr Surg Int 20:140–143 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Yasar Ayaz U, Dilli A, Ayaz S, et al. Ultrasonographic findings of intussusception in pediatric cases. Med Ultrasonogr. 2011;13(4):272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.del-Pozo GG, Albillos JC, Tejedor D, et al. Intussusception in children: current concept in diagnosis and enema reduction. RSNA. 1999;19(2):299–319. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.2.g99mr14299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Applegate KE. Intussusception in children: imaging choices. Semin Roentgenol. 2008;43(1):15–21. doi: 10.1053/j.ro.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munden MM, Bruzzi JF, Coley BD, et al. Sonography of pediatric small-bowel intussusception: differentiating surgical from nonsurgical cases. Pediatr Imaging AJR. 2007;188:275–279. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong N-T, Beasley SW. The lead-point in intussusception. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:640–643. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(90)90353-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daneman A, Myers M, Shuckett B, et al. The appearances of inverted Meckel diverticulum with intussusception. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:295–298. doi: 10.1007/s002470050132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jéquier S, Argyropoulou M, Bugmann P. Ultrasonography of jejunal intussusceptions in children. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1995;46:285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dicle O, Erbay G, Haciyanli M, et al. Inflammatory fibroid polyp presenting with intestinal invagination: sonographic and correlative imaging findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27:89–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199902)27:2<89::AID-JCU8>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del-Pozo G, Gonzalez-Spinola J, Gomez-Anson B. Intussusception: trapped peritoneal fluid detected with US—relationship to reducibility and ischemia. Radiology. 1996;201:379–386. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong MS, Wong HF, Lin SL, et al. Factor related to the detection of blood flow by color Doppler ultrasonography in intussusception. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:141–144. doi: 10.7863/jum.1997.16.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim SH, Bae HK, Lee SH, et al. Assessment of reducibility of ileocolic intussusception in children: usefulness of color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1994;191:781–785. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.3.8184064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorenstein A, Raucher A, Serour F, et al. Intussusception in children: reduction with repeated, delayed air enema. Radiology. 1998;206:721–724. doi: 10.1148/radiology.206.3.9494491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommea S, To T, Jacob C et al (2006) Factors determining the need for operative reduction in children with intussusception: a population-based study. J Pediatr Surg 41:1014–1019 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lai AH, Phua KB, Teo EL, et al. Intussusception: a three-year review. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2002;31:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shehata S, El Kholi N, Sultan A, et al. Hydrostatic reduction of intussusception: barium, air or saline? Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:380–382. doi: 10.1007/s003830000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim HK, Bae SH, Kee KH, et al. Assessment of reducibility of ileocolic intussusception in children: usefulness of color Doppler sonography. Radiology. 1994;191:781–785. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.3.8184064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verschelden P, Filiatraut D, Garel L. Intussusception in children: reliability of US in diagnosis—a prospective study. Radiology. 1992;182:77–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.1.1727313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sargent MA, Babyn P, Alton DJ. Plain abdominal radiography in suspected intussusception: a reassessment. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:17–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02017652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hryhorczuk AL, Strouse PJ. Validation of US as a first-line diagnostic test for assessment of pediatric ileocolic intussusception. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(10):1075–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]