Abstract

Background

Hearing loss is a heterogeneous neurosensory disorder. Mutations of 56 genes are reported to cause recessively inherited nonsyndromic deafness.

Objective

We sought to identify the genetic lesion causing hearing loss segregating in a large consanguineous Pakistani family.

Methods and Results

Mutations of GJB2 and all other genes reported to underlie recessive deafness were ruled out as the cause of the phenotype in the affected members of the participating family. Homozygosity mapping with a dense array of one million SNP markers allowed us to map the gene for recessively inherited severe hearing loss to chromosome 7q31.2, defining a new deafness locus designated DFNB97 (maximum LOD score of 4.8). Whole-exome sequencing revealed a novel missense mutation c.2521T>G (p.F841V) in MET, which encodes the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor. The mutation co-segregated with the hearing loss phenotype in the family and was absent from 800 chromosomes of ethnically matched control individuals as well as from 136,602 chromosomes in public databases of nucleotide variants. Analyses by multiple prediction programs indicated that p.F841V is likely damaging to MET function.

Conclusion

We identified a missense mutation of MET, encoding the hepatocyte growth factor receptor, as a likely cause of hearing loss in humans.

Keywords: Hearing Loss, Deafness, Hepatocyte Growth Factor Receptor (HGFR), MET, Pakistan

Nonsyndromic recessively inherited hearing loss contributes to an estimated 77% to 93% of hereditary deafness in humans.1 The majority of the reported mutations in the 56 genes identified to date cause an increase in hearing level (HL) threshold of greater than 91 dB, referred to as profound deafness. Alleles of some of these same genes can also cause progressive hearing loss or a stable loss ranging in severity from moderate (41–55 dB HL), to severe (71–90 dB HL).2 The genes with an essential role in hearing encode proteins with a variety of functions,3 including gap junctions, unconventional myosins, and several proteins that are necessary to form and maintain the stereociliar cytoskeleton. Mutations of two genes encoding receptors, ESRRB (estrogen-related receptor beta, OMIM 60627) and ILDR1 (immunoglobulin-like domain containing receptor 1, OMIM 609739) are associated with deafness in humans. HGF encodes a growth factor (hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor) and noncoding mutations of HGF segregating in numerous Pakistani families cause nonsyndromic severe to profound deafness4 (OMIM 142409).

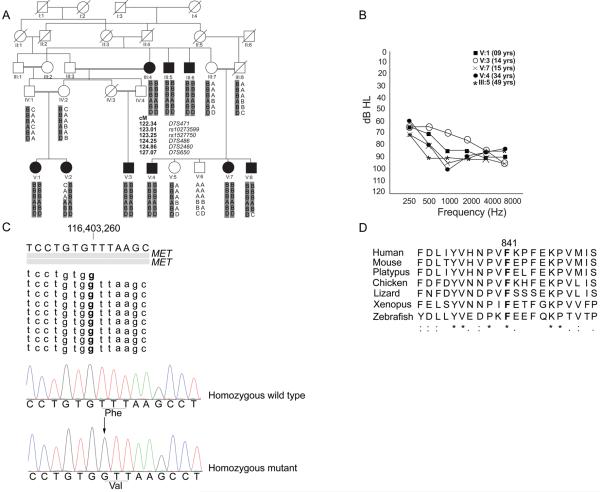

We recruited a large family HLGM17 (figure 1A) and proceeded to map and identify the gene responsible for hearing loss segregating in the affected members. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the School of Biological Sciences, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan and the National Institutes of Health, USA. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. The family includes 9 individuals (age range = 5–60 years old) with hearing loss at or before 2 years of age, noticeable due to delay in development of speech. Audiometry in ambient noise conditions revealed a severe degree of sensorineural hearing loss (pure tone average, PTA500 Hz-4000 Hz, 74–89 dB HL) with intra-familial variations in thresholds, (figure 1B). The participants were reported to independently ambulate by 12–13 months of age. The results of tandem gait and Romberg tests were normal, suggesting intact, or at least residual, peripheral vestibular function. Medical conditions including those related to liver, kidney and heart were not reported and there was no history of cancers in the family. Results of clinical evaluations, including complete blood counts, serum chemistries, urinalysis, liver function tests and funduscopy, were normal for two affected individuals (12 and 15 years old).

Figure 1. Family HLGM17, audiograms, mutation and conservation of p.F841.

(A) Pedigree of Family HLGM17. Black symbols represent affected individuals. Double horizontal lines indicate consanguineous matings. The ancestral DFNB97 haplotype with alleles of four STR markers and two SNP markers spanning 4.73 cM on chromosome 7 is shaded in gray. Samples from IV:2, V:1, V:2 and V:3 were used for SNP genotyping. Meiotic recombination breakpoints in individuals V:2 and V:8 define the proximal and distal boundary, respectively, of a linkage interval of 4.06 cM (chromosome 7:115181357 bp-120965265 bp,GRCh37/ hg19). Positions of markers are shown according to Rutgers Combined Linkage-Physical Map.

(B) Pure-tone audiometry results of selected affected individuals of family HLGM17. Variation in hearing loss thresholds was observed for most individuals.

(C) DNAnexus analysis of the exome data from a region encompassing the c.2521T>G variant detected in MET. The gray bars depict two Refseq transcripts of MET. Nine of a total of 30 DNA sequence reads which cover this region are shown. The variation is visible in bold. Chromatograms generated through Sanger sequencing are also shown below this alignment, with the site of mutation underlined in both traces of affected and unaffected individuals. The “arrow” indicates the mutated base.

(D) ClustalW analysis of MET residues surrounding the site of the missense mutation showing conservation of p.F841 among diverse vertebrate species. The orthologous amino acid positions which are identical to p.F841 are shown in bold. Amino acid residues which are identical in all orthologoues are indicated by an asterisk below the alignment. The colons and periods indicate amino acid substitutions with highly conserved and less conserved residues, respectively.

Mutations of GJB2 and all other genes reported to underlie recessive deafness were ruled out in our study family by sequencing or linkage analyses with microsatellite markers tightly linked to the respective loci. Samples from four individuals were selected for genome-wide homozygosity mapping: the unaffected mother (IV:2), her two affected offspring (V:1, V:2) and her nephew with hearing loss (V:3). SNP genotyping was performed (Atlas Biolabs, Germany) with the Affymetrix SNP 6 array of one million SNP markers across the genome. KinSNP analyses5 revealed three regions of homozygosity on chromosomes 2, 6 and 7 (table S1). Genotyping with microsatellite markers across samples from other members of the family confirmed linkage to a 4.06 cM region on chromosome 7 (figure 1A, table S2). A maximum LOD score of 4.8 at θ = 0 was obtained with markers D7S486 and D7S2460. This locus was designated DFNB97 by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC). DFNB97 overlaps with the originally reported interval for the DFNB176 locus (OMIM 603010). However, the DFNB17 interval was subsequently refined7 to a non-overlapping 5.5-Mb region centromeric of DFNB97. In order to find the contribution of the newly mapped locus to deafness, we screened 100 families in which the moderate to profound hearing loss was not attributable to a known deafness gene variant. No other families were identified, which suggests that DFNB97 is a rare cause of hearing loss in Pakistan.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed on a DNA sample from individual V:1 (Otogenetics, USA). The exome was enriched using a NimbleGen V2 kit and sequenced on a HiSeq2000 using a paired-end (2×100 bp) protocol. FASTQ reads were mapped to the human genome (GRCh37/ hg19) by DNAnexus software with default settings on a cloud platform (table S3). We analyzed the exome data and generated a list of all variants in the genes known to cause hearing loss. Consistent with the genetic linkage analysis results, none of these genes had a pathogenic mutation. Next, the exome data was filtered and the analysis confined to variants located in the DFNB97 interval (chromosome 7:115181357 -120965265). We inspected the data alignment in this region to the reference genome at base pair resolution for each exon and the surrounding introns (DNAnexus and UCSC genome browsers). In the DFNB97 interval, all exons except one were fully captured for exome analysis (WES) and were sequenced with at least 50 bp of flanking intronic boundaries and a minimum of 10 reads. A GC-rich region of an exon was partially sequenced and probes for alternative exons of 6 genes were absent from the NimbleGen array (table S4). These exons not covered or captured by WES were analysed by Sanger sequencing of PCR amplification products, but no mutations were identified. A homozygous non-synonymous variant located in MET (Mesenchymal Epithelial Transition factor, NM_000245.2), c.2521T>G (p.F841V), hg19, chr7:116403260T>G, was identified in the exome data, ClinVar# SCV000211990 (figure 1C, table S5). The variant co-segregated with the phenotype, being homozygous in all 9 affected individuals, and was absent from DNA of 400 ethnically matched individuals (800 chromosomes). The mutation was also absent from the Exome Variant Server (6,503 individuals), Exome Aggregation Consortium dataset (60,706 individuals) and the 1000 genomes project database (1,092 individuals). These results support the hypothesis that this mutation in MET is the cause of DFNB97 hearing loss in our study family. However, since we only analyzed exonic regions, it is possible that a mutation in a regulatory region of MET or in a cis-acting element of any of the other 16 genes in the critical DFNB97 interval may be responsible for the hearing loss in family HLGM17 and the p.F841V variant is in linkage disequilibrium with the pathogenic allele.

Human MET exhibits extensive amino acid sequence identity with its orthologues, ranging from 98% for the chimpanzee to 50.64% for the zebrafish. CLUSTALW analysis revealed that the phenylalanine residue substituted by the mutation in family HLGM17 is conserved among diverse vertebrate species (figure 1D), indicating that p.F841 is important for MET function. Although SIFT predicts that p.F841V is “tolerated”, PROVEAN, PolyPhen-2, Human splicing finder and Mutation Taster predicted it to be “damaging” to MET function.

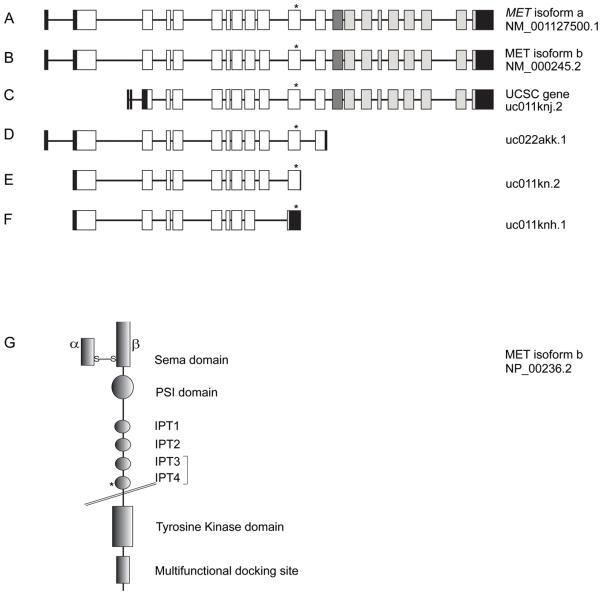

Alternative splicing of MET results in multiple mRNA transcripts. The two longest isoforms encode proteins of 1,408, or 1,390 amino acids (figure 2A, 2B) with the mutation located in exon 11 of these two isoforms. Four of the other mRNA transcripts also encompass the exon that has the mutation (figure 2C, 2D, 2E, 2F). A predicted gain of an internal donor splice site by mutation taster (score 0.99), within exon 11 of MET due to the c.2521T>G, mutation was investigated by an exon trap assay.4 Results of the experiments revealed that all but 2 of the total 65 clones derived from the transfection of mutant construct were identical to those obtained after transfection of the wild-type construct. However, one transcript obtained after transfection of the mutant construct, retained part of intron 10 with exon 11 while in the second transcript, part of intron 11 was retained with exon 11. This indicates that the c.2521T>G mutation may have a limited effect on splicing or alternatively, the mutation does not affect splicing and the two aberrant splicing products are experimental artifacts.

Figure 2. Schematic representations of MET isoforms and the processed receptor.

(A) MET isoform a encodes the highest molecular-weight protein among all the isoforms. Black boxes denote non-coding exons. White boxes depict exons encoding the extracellular part of MET. The dark grey box represents exon 13 which encodes the transmembrane domain. Exons shown in light grey encode the cytoplasmic domain of MET. The asterisk marks the position of the mutation.

(B) MET isoform b is the highest transcribed isoform in all cell types examined to date and differs from isoform a by the absence of 54 nucleotides in exon 10. The asterisk shows the position of the c.2521T>G mutation in exon 11.

(C) A UCSC MET isoform lacks an exon which is known to encode most of the Sema domain.

(D) A predicted soluble MET isoform lacks sequences encoding the transmembrane anchoring amino acids.

(E) The DFNB97 missense mutation in a MET transcript is located 113 nucleotides upstream of the stop codon within an exon which corresponds to exon 11 of isoforms a and b.

(F) A MET isoform is annotated in which a stop codon is introduced in the exon corresponding to exon 11 of isoforms a and b due to absence of an exon present in other isoforms. The DFNB97 mutation is present in the 3′ UTR of this transcript.

(G) Schematic representation of the structure of MET isoform b showing the two processed subunits and different domains. The extracellular part of the receptor contains the ligand binding site and other domains. The Sema domain consists of the N-terminus part of the β-chain disulphide linked to the α-chain and binds to HGF. This is N-terminal to the PSI domain and four Ig or IPT domains. The bracket around IPT3 and IPT4 denotes a high-affinity binding site for HGF. The intracellular region of MET contains a kinase domain and residues involved in protein interactions and downstream signalling. The position of p.F841V mutation within IPT4 is marked by an asterisk.

MET is synthesized as a precursor protein and then proteolytically cleaved by furin to form alpha and beta subunits, which are covalently linked through disulphide bonds. The alpha subunit and part of the beta subunit of MET together form a low affinity binding site for HGF. The beta subunit has a cysteine-rich region termed PSI (Plexins, Semaphorins and Integrins) and four IPT (Immunoglobulin-like, Plexins, Transcription factors) domains, which are important structural components of the MET extracellular region (figure 2G). The beta subunit also traverses the plasma membrane and provides a cytoplasmic domain (figure 2G). The cytoplasmic portion of MET contains the tyrosine kinase domain which autophosphorylates the receptor at specific tyrosine residues upon HGF binding or upon activation by other cellular co-receptors.8 Conserved residues at the C-terminus also serve as an interface for docking of MET with its partner proteins.8 The activation of MET leads to the binding and phosphorylation within the cell of adapter proteins, such as GAB1 and GRB2, which in turn activate signalling transducers including PIK3, PTPN11, PTK2, and STATs.9

The extracellular domains of MET are involved in ligand-dependent receptor homodimerization and ligand-independent interactions with other cellular co-receptors such as CD44, EGFR and integrin α6β4.8 The mutation p.F841V is located in the extracellular IPT4 domain (figure 2G). Modelling the p.F841V mutation with CUPSAT and I-Mutant 2.0 using the crystal structure of IPT2-IPT410 (PDB ID, 2CEW) and the amino acid sequence of MET (NP_000236.2) predicted a decrease in the overall stability of the resulting protein. The IPT3 and IPT4 domains together form a high-affinity binding site for HGF.11 In the donut mutant zebrafish, a missense mutation in met affects the IPT3 domain (p.L775R equivalent to human p.I777R).12 The maturation of Met, its transport to the plasma membrane and the rate of activation of the kinase domain are all negatively affected by the mutation and result in failed outgrowth of the exocrine pancreas in donut mutants.12 We speculate that the p.F841V mutation may similarly affect human MET function, but with phenotypic consequences limited to the inner ear. Other possibilities for the pathogenic effect of the p.F841V mutation are that it reduces receptor stability and affinity for binding to HGF or impairs interaction with cellular coreceptors. Alternatively, the mutation may change expression level of some MET isoforms, similar to the effect seen for a missense variant that causes a dystonia-ataxia syndrome.13

In contrast to the phenotype in donut mutants, zebrafish met morphants have strikingly different defects including dysmorphology of the hypaxial muscles and impairment of the development of the lateral line. The zebrafish lateral line contains the neuromasts which resemble vertebrate inner ear sensory epithelia.14 The met morphants have diminished deposition of the proneuromast cells, as well as reduced number of migrating neuromast-derived hair cells and the non-neural supporting cells.15 It remains to be investigated if the sensory cells in the inner ear of the zebrafish morphants are similarly affected.

HGF is the only known ligand of MET and together the two proteins play a part in proliferation, migration and invasive growth.8 MET also participates in epithelial development by interacting with the scaffolding protein, GAB1.16 Met is expressed in the inner ears of rats 17 and mice (Shared Harvard Inner-Ear Laboratory Database). The role of HGF and MET interaction in the inner ear is not known. The involvement of HGF/MET signaling in healing of skin wounds,18 suggests the possibility of a similar function in repair of cochlea after trauma due to chemicals or noise. This is supported by the observation that intrathecal injection of Haemagglutinating Virus of Japan Envelope (HVJ-E) containing HGF to cerebrospinal fluid in rats increases expression of endogenous Hgf and Met and was reported to prevent and ameliorate hearing impairment induced by kanamycin treatment.17

Mouse models have been investigated to determine the role of HGF/MET signalling. In mice, a null allele of Met is embryonic-lethal due to severe developmental defects.19 Therefore, the inner ear pathophysiology due to loss of MET may be studied by using transgenic mice in which Met is deleted specifically in the inner ear using mice with a floxed Met 20 and Cre recombinase under the direction of an inner ear specific promoter. A second strategy would be to knock-in the equivalent human mutation of MET (c.2521T>G; p.F841V) in the mouse orthologue, Met.

MET and HGF are the first described receptor-ligand pair for which a mutation of either protein causes nonsyndromic recessive deafness in humans. We speculate that mutations in other genes encoding different proteins of the HGF/MET signalling pathway may also result in hearing loss. Continued research will yield insights into function of HGF/MET interaction in the auditory system and will also identify other associated proteins necessary for normal hearing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the family for participating in the study. We are highly grateful to Mr. Muhammad Usman for ascertainment of the family and Dr. Meghan Drummond for helpful discussions. We thank Dr. Andrew Griffith and Dr. Dennis Drayna for reviewing the manuscript.

FUNDING Grant number R01TW007608 from the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, USA to S.N. This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health intramural funds from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders DC000039-18 to T.B.F.

Footnotes

WEB RESOURCES 1000 Genomes Project, http://www.1000genomes.org

Clinical Variation, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/

ClustalW, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/

CUPSAT, http://cupsat.tu-bs.de/

DNAnexus, https://www.dnanexus.com/

Exome Aggregation Consortium, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Human Splicing Finder, http://www.umd.be/HSF/

I-Mutant 2.0, http://folding.biofold.org/i-mutant/i-mutant2.0.html

MutationTaster http://www.mutationtaster.org/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM, http://www.omim.org

Polyphen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml

Protein Data Bank, PDB, http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do

Protein Variation Effect Analyzer, PROVEAN, http://provean.jcvi.org/

Rutgers combined linkage-physical map, http://compgen.rutgers.edu/rutgers_maps.shtml

Shared Harvard inner-ear laboratory database, SHIELD, https://shield.hms.harvard.edu/

Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant, SIFT, http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/

UCSC Genome Browser Feb. 2009 (GRCh37/hg19), https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgibin/hgGateway

CONTRIBUTORS GM, SN to mapping of DFNB97 and identification of MET, JMS to exon-splicing assay, AI, RJM for helping with predictions on MET mutational effects and experimental work. TBF and SN coordinated the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS None

ETHICS REVIEW University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan (IRB00005281) and Combined Neuroscience IRB; OH-93-N-016 in USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duman D, Tekin M. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness genes: a review. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2213–36. doi: 10.2741/4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherry R, Rubinstein A. The audiological screening for the speech language evaluation. In: Stein-Rubin C, Fabus R, editors. A Guide to Clinical Assessment and Professional Report Writing in Speech-Language Pathology. 1 ed Delmar/Cengage Learning; 2011. p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dror AA, Avraham KB. Hearing impairment: a panoply of genes and functions. Neuron. 2010;68:293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz JM, Khan SN, Ahmed ZM, Riazuddin S, Waryah AM, Chhatre D, Starost MF, Ploplis B, Buckley S, Velasquez D, Kabra M, Lee K, Hassan MJ, Ali G, Ansar M, Ghosh M, Wilcox ER, Ahmad W, Merlino G, Leal SM, Friedman TB, Morell RJ. Noncoding mutations of HGF are associated with nonsyndromic hearing loss, DFNB39. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amir el AD, Bartal O, Morad E, Nagar T, Sheynin J, Parvari R, Chalifa-Caspi V. KinSNP software for homozygosity mapping of disease genes using SNP microarrays. Hum Genomics. 2010;4:394–401. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-6-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greinwald JH, Jr., Wayne S, Chen AH, Scott DA, Zbar RI, Kraft ML, Prasad S, Ramesh A, Coucke P, Srisailapathy CR, Lovett M, Van Camp G, Smith RJ. Localization of a novel gene for nonsyndromic hearing loss (DFNB17) to chromosome region 7q31. Am J Med Genet. 1998;78:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo Y, Pilipenko V, Lim LH, Dou H, Johnson L, Srisailapathy CR, Ramesh A, Choo DI, Smith RJ, Greinwald JH. Refining the DFNB17 interval in consanguineous Indian families. Mol Biol Rep. 2004;31:97–105. doi: 10.1023/b:mole.0000031385.64105.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organ SL, Tsao MS. An overview of the c-MET signaling pathway. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2011;3:S7–S19. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birchmeier C, Birchmeier W, Gherardi E, Vande Woude GF. Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:915–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gherardi E, Sandin S, Petoukhov MV, Finch J, Youles ME, Ofverstedt LG, Miguel RN, Blundell TL, Vande Woude GF, Skoglund U, Svergun DI. Structural basis of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor and MET signalling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4046–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basilico C, Arnesano A, Galluzzo M, Comoglio PM, Michieli P. A high affinity hepatocyte growth factor-binding site in the immunoglobulin-like region of Met. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21267–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800727200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson RM, Delous M, Bosch JA, Ye L, Robertson MA, Hesselson D, Stainier DY. Hepatocyte growth factor signaling in intrapancreatic ductal cells drives pancreatic morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doss S, Lohmann K, Seibler P, Arns B, Klopstock T, Zuhlke C, Freimann K, Winkler S, Lohnau T, Drungowski M, Nurnberg P, Wiegers K, Lohmann E, Naz S, Kasten M, Bohner G, Ramirez A, Endres M, Klein C. Recessive dystonia-ataxia syndrome in a Turkish family caused by a COX20 (FAM36A) mutation. J Neurol. 2014;261:207–12. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitfield TT. Lateral line: precocious phenotypes and planar polarity. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haines L, Neyt C, Gautier P, Keenan DG, Bryson-Richardson RJ, Hollway GE, Cole NJ, Currie PD. Met and Hgf signaling controls hypaxial muscle and lateral line development in the zebrafish. Development. 2004;131:4857–69. doi: 10.1242/dev.01374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weidner KM, Di Cesare S, Sachs M, Brinkmann V, Behrens J, Birchmeier W. Interaction between Gab1 and the c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase is responsible for epithelial morphogenesis. Nature. 1996;384:173–6. doi: 10.1038/384173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oshima K, Shimamura M, Mizuno S, Tamai K, Doi K, Morishita R, Nakamura T, Kubo T, Kaneda Y. Intrathecal injection of HVJ-E containing HGF gene to cerebrospinal fluid can prevent and ameliorate hearing impairment in rats. FASEB J. 2004;18:212–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0567fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li JF, Duan HF, Wu CT, Zhang DJ, Deng Y, Yin HL, Han B, Gong HC, Wang HW, Wang YL. HGF accelerates wound healing by promoting the dedifferentiation of epidermal cells through beta1-integrin/ILK pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:470418. doi: 10.1155/2013/470418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uehara Y, Minowa O, Mori C, Shiota K, Kuno J, Noda T, Kitamura N. Placental defect and embryonic lethality in mice lacking hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Nature. 1995;373:702–5. doi: 10.1038/373702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borowiak M, Garratt AN, Wustefeld T, Strehle M, Trautwein C, Birchmeier C. Met provides essential signals for liver regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403412101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.