Abstract

Esophageal adenocarcinomas (EACs) are associated with dismal prognosis. Deciphering the evolutionary histories of this disease may shed light on therapeutically tractable targets and reveal dynamic mutational processes during the disease course and following neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). We exome sequenced 40 tumor regions from 8 patients with operable EACs, before and after platinum-containing NAC. This revealed the evolutionary genomic landscape of EACs with the presence of heterogeneous driver mutations, parallel evolution, early genome doubling events and an association between high intratumor heterogeneity and poor response to NAC. Multi-region sequencing demonstrated a significant reduction in T>G mutations within a CTT context when comparing early and late mutational processes and the presence of a platinum signature with enrichment of C>A mutations within a CpC context following NAC. EACs are characterized by early chromosomal instability leading to amplifications containing targetable oncogenes persisting through chemotherapy, providing a rationale for future therapeutic approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer is associated with dismal clinical outcome with only modest improvement in survival over recent decades (1). In addition, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has increased markedly over the past two decades in Western countries (2).

Whilst sequencing studies have identified drivers in EAC (3, 4), little is known regarding the clonal evolution of surgically operable disease and the impact of cytotoxic therapy upon the genomic landscape of residual tumor at surgery. Treatment with curative intent of resectable EAC involves surgical resection with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) or chemo-radiotherapy (5). NAC confers a survival advantage over surgery alone (6), but 50-60% of tumors are resistant to treatment (5). Whole exome sequencing in EAC identified 26 significantly mutated genes and in another study high density genomic profiling arrays identified focal somatic copy number aberrations containing therapeutically targetable kinases such as ERBB2, FGFR1, FGFR2, EGFR, and MET in a cohort of EACs. The timing of these events within the context of EAC evolution is unknown (3, 7, 8).

Several sequencing studies have begun to unravel the evolutionary histories of human cancers (9, 10). Emerging evidence reveals that phylogenetic analysis of multi-region exome sequence datasets from a single tumor allows the discrimination of conserved early genetic events present at all sites of the tumor sampled, from later mutations present in only part of the tumor. Distinguishing early from later somatic events during tumor evolution allows the temporal order of mutational processes that occur during the disease course to be resolved (4, 11-14). Previous studies have shown that the evolution from Barrett’s esophagus (BE) to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is dominated by loss of TP53, genome doubling, chromosomal instability (CIN) and a high frequency of chromothripsis events resulting in genomic diversity and an increase in the prevalence of focal amplifications and copy number gains and losses (4, 7, 15-17). We obtained multiple tumor regions from 8 EACs, acquired consecutively within a prospective tissue collection protocol, both at diagnosis and at surgery following platinum containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, in order to distinguish early from later somatic driver events and to decipher the genomic architecture of EAC during disease evolution and following cytotoxic therapy.

RESULTS

Genomic architecture and diversity in human EAC

We performed multi-region exome sequencing (M-seq) on 8 tumors from patients with operable EACs to assess tumor evolution both spatially (sequencing different regions of the primary tumor) and temporally (sequencing further regions of the tumor following combination chemotherapy). In total, 40 regions were sequenced. Tumor and germline regions were sequenced at median 90-fold coverage across the exonic capture regions (Supplementary Table S1). The clinical characteristics of these 8 patients are shown in Supplementary Table S2 and included patients with stage IIA to IIIC disease. Orthogonal validation showed a validation rate of 96.1% (see Methods).

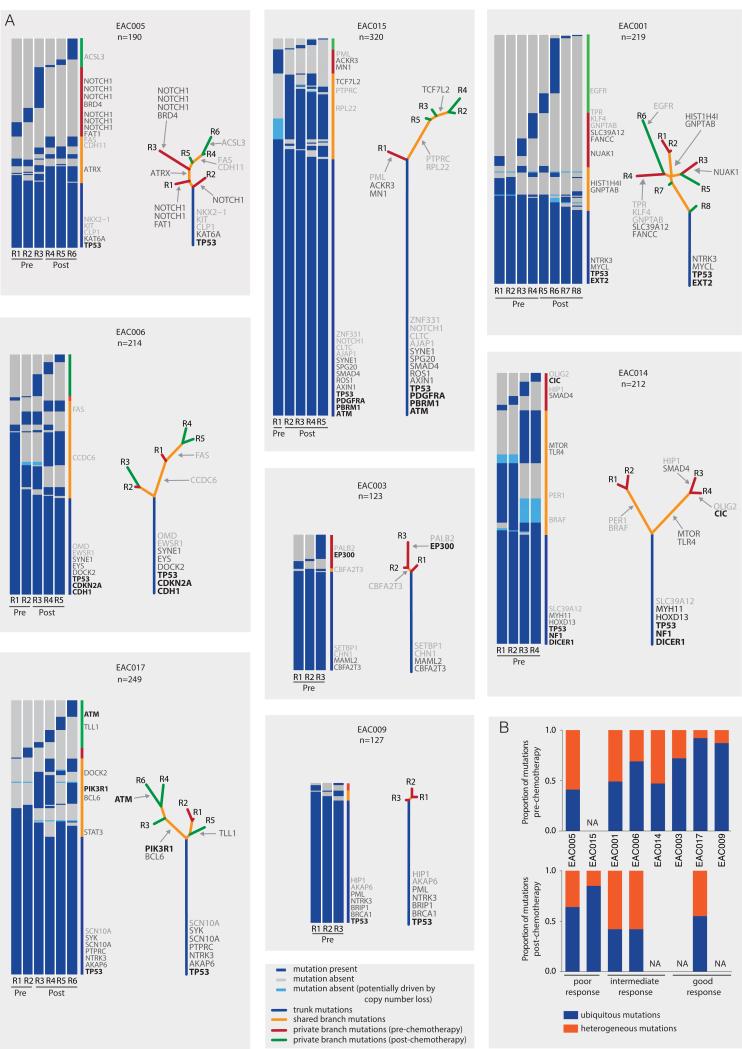

To assess the extent of spatial and temporal intratumor heterogeneity in EAC, non-silent somatic mutations were first classified as either ubiquitously detected, if detected in all tumor regions, or heterogeneous, if identified in one or more tumor regions, but not all. All tumors demonstrated spatial and temporal heterogeneity with a median of 55.63% of non-silent mutations being heterogeneous (range 12.6% to 69.4%) (Fig. 1A). The total number of non-silent mutations identified in these tumors (median = 213) was significantly greater (p=0.0109, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test) than the number of mutations identified if only a single tumor region had been sampled (median = 127.5), highlighting intratumor heterogeneity and the underestimation of mutational burden and clonal architecture from single samples in EAC (Supplementary Fig. S1). The proportion of heterogeneous mutations in each tumor, both pre- and post-chemotherapy is shown in Fig. 1B. We assessed this further by generating an intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) index. This was calculated for each tumor as the mean of the proportion of heterogeneous mutations relative to the total number of mutations determined by pairwise comparison of all pre-chemotherapy tumor regions. Intriguingly, we observed a strong correlation between the ITH index and response to NAC (Supplementary Fig. S2, Spearman rho = 0.93, p=0.015).

Figure 1.

Intratumor heterogeneity of somatic mutations. A, Heatmaps show the regional distribution of all non-silent mutations; presence (blue), absence, potentially due to copy number loss (light blue) or absence (grey) of each mutation is indicated for every tumor region. Column next to heatmap shows the distribution of mutations; mutation present in all tumor regions (blue), shared in more than one but not all regions (orange), in one pre-chemotherapy tumor region (red) and in one post-chemotherapy tumor region (green). Mutations are ordered by tumor driver category with categories 1-3 indicated in the right column in black, dark grey and light grey respectively (details in Supplementary Table S3). Total number of non-silent mutations (n) is provided for each tumor. Phylogenetic trees generated by a parsimony ratchet approach (18) based on the distribution of all detected mutations are shown to the right of the heatmap; trunk and branch lengths are proportional to the number of non-silent mutations acquired. Category 1, 2 and 3 driver mutations are indicated next to the trunk or with an arrow pointing to the branches where they were acquired. B, Plots show the proportion of trunk and branch mutations in the pre- and post-chemotherapy tumor regions. NA; data not available for these tumors; only one pre-chemotherapy tumor region available for analysis in EAC015 and tumors EAC014, EAC003, EAC009 had responded well to treatment with low tumor purity levels in the post chemotherapy regions, rendering analysis intractable.

Evaluation of truncal and branched driver point mutations

Filtered non-silent variants from each tumor region were used to construct phylogenetic trees using the parsimony ratchet method (18) (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. S3), with branch lengths reflecting the number of non-silent mutations. To account for SNV heterogeneity driven by copy number events, we identified all mutations in genomic segments of copy number variation across tumor regions and filtered those whose absence, or low variant allele frequency, could be explained by copy number loss. For example, in EAC015, we identified a genomic segment harboring 16 mutations. This segment was deleted in region R1 but present in all other tumor regions. Thus, the heterogeneity in this case can be explained by a single copy number loss event (Supplementary Fig. S4).

We then classified somatic SNVs in known cancer genes into category 1-3 driver events depending on evidence supporting driver mutation status (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table S3), with all other SNVs classified as category 4. We evaluated where on the phylogenetic tree these driver mutations were located. Overall, 47% (n=46) of putative driver events (category 1-3) were found to occur as branch mutations in the 8 EACs. Whilst there was an enrichment (p=0.08) of category 1 driver events on the trunks of the phylogenetic trees, 24% (n=4) of the category 1 events were located on the branches, occurring in 3 of the 8 tumors (EAC003, EAC014 and EAC017) with PIK3R1 in EAC017 as a potentially targetable mutation. Interestingly, these data support our recent findings that mutations in PIK3R1 have a tendency to be later, subclonal, events across cancer types (14). 52% of category 2 and category 3 drivers were detected in only a subset of regions. Additionally, we identified 10 frameshift indels within annotated driver genes, of which six were located on the trunk, including two in TP53 (EAC006 and EAC015). We also identified 15 of the 26 putative drivers reported in EAC (3) and mutations in 7 of these 15 drivers were found to occur on the branches (SMAD4, TLR4, SLC39A12, TLL1, EYS, NUAK1 and DOCK2; Supplementary Fig. S5). Their presence on the branches of the phylogenetic tree suggests that they may be more prevalent than expected based on single sample analyses in EAC. Supporting this, we identified a significantly greater number of driver mutations using the M-seq approach compared to a single biopsy for each of these tumors (p=0.041, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test) (Supplementary Fig. S6).

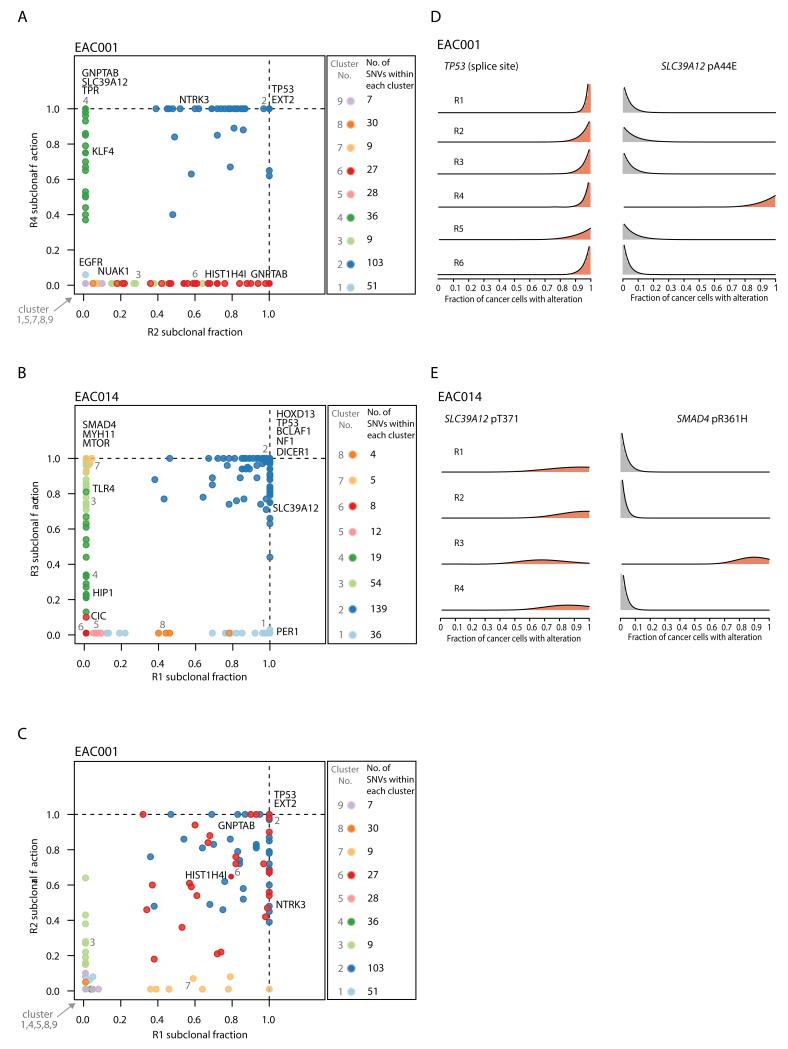

Next, to further resolve the clonal architecture of each tumor, we integrated copy number, variant allele frequencies and purity estimates to calculate the cancer cell fraction (CCF) of each mutation within each tumor region. We found evidence for at least one driver mutation (category 1-3) exhibiting an illusion of clonality in all but one tumor (EAC009) (Supplementary Fig S5). Such mutations appear clonally dominant within one tumor region, but are not detectable in other tumor regions. For instance, in EAC001, a non-silent mutation in SLC39A12 (pA44E), a gene that was identified as recurrently mutated in EAC (3), was estimated to be present in 100% of cancer cells within region R4 but was undetectable in all other tumor regions. Similarly, in EAC014, a mutation in SMAD4 (pR361H) was present in all cancer cells within region R3, but was undetectable in the remaining tumor regions. Conversely, mutations in SLC39A12 (pT37I) and TP53 (splice site) in EAC014 and EAC001 respectively were both found to be clonal in all tumor regions. (Fig. 2A - E).

Figure 2.

Cancer cell fraction comparisons for different tumor regions. A-C, In each plot, the cancer cell fraction of all single nucleotide variants (SNVs) for one tumor region is plotted against another tumor region. The SNVs within each cluster are indicated. D-E, Representative probability distributions over the cancer cell fraction for individual mutations are shown for specific tumors.

More generally, consistent with previous reports (3, 4), mutations in TP53 were always identified as fully clonal, and, in every case, mutations in TP53 were accompanied by copy neutral LOH, highlighting the importance of mutations in TP53 as early driver events. Likewise, mutation and complete loss of the wild-type allele was observed in all tumor regions for CDKN2A and SMAD4 in EAC006 and EAC015 respectively. These mutations likely occurred prior to truncal genome doubling (GD) events (see Supplementary Methods). However, in EAC014, while mutation and LOH was also observed in SMAD4, this was exclusive to region R3 and, similarly, for EAC017 mutation and LOH was observed in PIK3R1, but only in region R4.

In two out of the eight tumors we observed evidence for parallel evolution. In EAC005 multiple distinct mutations in NOTCH1 were identified in separate tumor regions (Fig. 1A) (19, 20), while in EAC001 multiple distinct mutations in GNPTAB were detected in different tumor regions (Fig. 1A and 2A). These data imply the existence of convergent selection pressures at later stages of tumor evolution. The clonal architecture of each tumor region also sheds light on the spatial relationships between tumor regions. Certain regions, such as regions R2 and R4 in EAC001, did not share any subclonal mutations, potentially indicative of geographical barriers existing between these regions, fostering subclonal diversification (Fig. 2A). Conversely, other tumor regions, including regions R1 and R2 in EAC001, shared multiple subclonal mutations, consistent with intermingling subclones between these tumor regions (Fig. 2C).

Chromosomal instability and copy number amplifications are early drivers

Copy number analysis on the M-seq data revealed that all tumors showed extensive somatic copy number aberrations (Supplementary Fig. S7). Additionally, all tumors had evidence of ubiquitous TP53 disruption, either through mutation (7/8) or by amplification of MDM2 (EAC003), and all tumor regions showed evidence of GD. This is consistent with previous reports describing early TP53 inactivation followed by CIN and GD as an early defining event in the evolution of EAC (4, 17). We also found evidence of early chromothripsis events in two tumors, on chromosome 1 in EAC003, and on chromosome 19 in EAC017 (Supplementary Fig. S8). Both events were ubiquitously found in all tumor regions. To further measure the degree of CIN in this cohort, we calculated the weighted genome integrity index (wGII) as a proxy for CIN (21). We found that all tumor regions in this study showed high levels of wGII (median 0.53, range 0.31-0.66), indicative of CIN (21).

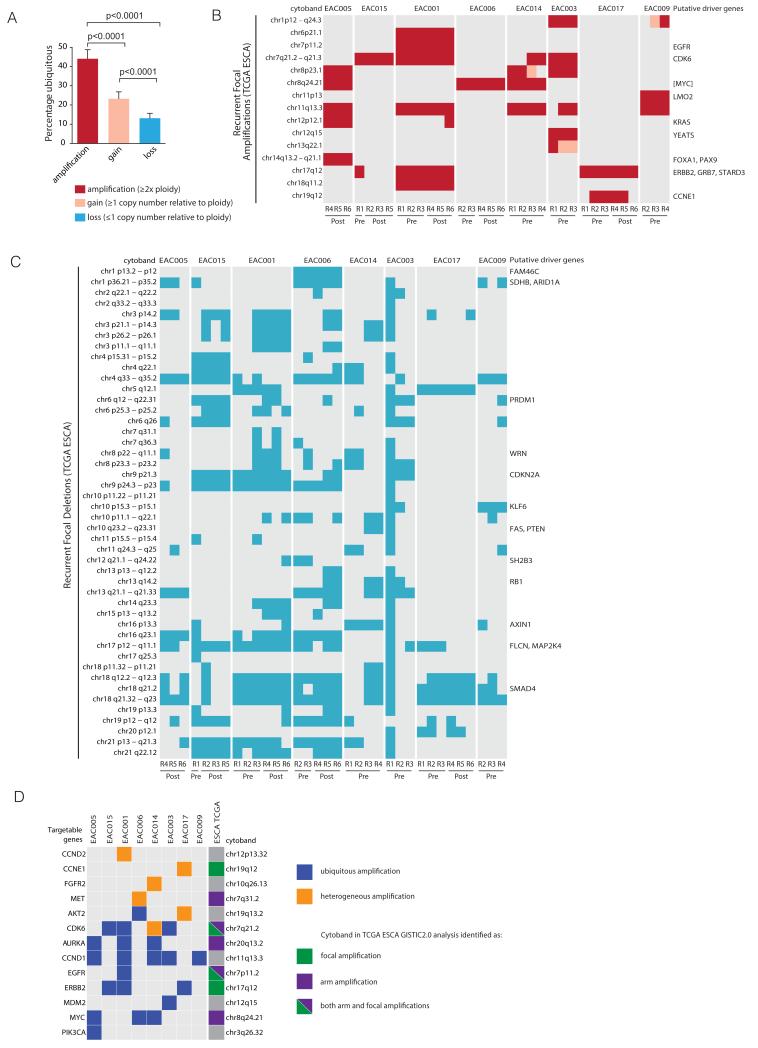

A similar level was observed in EAC tumors from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset (Supplementary Fig. S9), providing further support for CIN as a defining feature of EAC. Next, we analyzed the extent of heterogeneity at the copy number level. Across our cohort of 8 tumors, we identified 1090 genomic segments of copy number gain (≥1 copy number relative to ploidy), and 824 segments of copy number loss (≤1 copy number relative to ploidy). Of these, on average only 24% and 13% respectively, were ubiquitously identified in all tumor regions sequenced within a tumor, consistent with extensive CIN in these tumors. However, chromosomal amplifications (≥2x ploidy) were significantly more likely to be ubiquitously identified across tumour regions than either gains or losses (Fig. 3A). These data suggest chromosomal amplifications may often represent early events, which are maintained through NAC (Fig. 3B). In further support of ubiquitously identified amplifications representing shared events, haplotype analysis confirmed that the same allele was likely amplified in the majority of cases (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Intratumor heterogeneity of chromosomal alterations. A, Plot showing the percentage of ubiquitous copy number amplifications, gains and losses (+SEM) for all tumors. B and C, Heatmaps showing the distribution of potential tumor driver copy number amplifications and deletions for each tumor region based on recurrently amplified and deleted chromosomal segments identified from TCGA esophageal cancer (ESCA) data. For each region, amplification was determined as ≥2x ploidy and copy number loss was determined as ≤1 copy number, relative to ploidy. If no putative driver genes were identified within the recurrent amplification or deletion, the nearest gene appears in square brackets as described by GISTIC2.0 (22). D, Heatmap showing amplifications identified within the cohort of tumors containing a targetable oncogene as identified by the TARGET dataset (23) and whether these occur as ubiquitous (blue) or heterogeneous (orange) amplifications and if they occur as recurrent focal or arm level amplifications based on TCGA ESCA data (22).

We then assessed whether the somatic copy number variations in our cohort were similar to those previously identified by TCGA using Gistic v2 (22). We found that 15 chromosomal segments previously identified in the TCGA cohort were amplified in at least one sample in our cohort, and 46 chromosomal segments exhibiting copy number loss overlapped with TCGA recurrent deletions (Fig 3B and C). With regards to amplifications, these were mostly ubiquitously identified and maintained within all tumor regions pre- and post-NAC and were often centered on specific oncogenes, such as c-MYC, CCND1, ERBB2, EGFR and KRAS (Fig. 3B and D; Supplementary Table S4). Notably, 9 genes that were ubiquitously amplified in at least one tumor and maintained following NAC, including AKT2, AURKA, CCND1, CDK6, ERBB2, EGFR and PIK3CA (Fig. 3D), have all been identified in the TARGET database (version 2) as potentially targetable copy number aberrations (23).

Mutation spectra of truncal and branch mutations

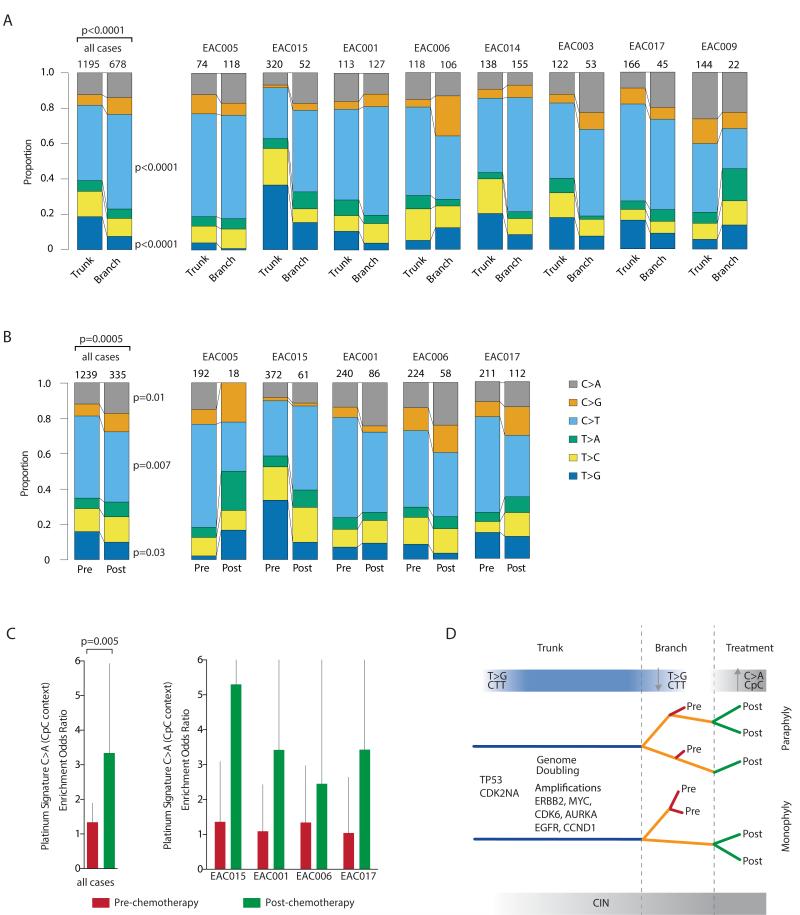

Mutational processes may be dynamic both spatially and temporally within individual tumor types (11, 12). We therefore examined the timing of mutational processes during EAC evolution. We observed statistically significant changes in the mutation spectra over time when comparing early (trunk) versus late (branched) somatic mutations. In early mutations we observed a strong enrichment for T>G mutations within a CTT context (6 out of 8 cases, p<0.0001). This mutation signature has previously been associated with BE and esophageal adenocarcinoma and may result from gastric acid reflux (3, 4, 17). When focusing on late mutations, we observed a relative decrease in the proportion of T>G mutations within a CTT context (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S10) and a relative increase in C>T mutations at CpG sites, previously reported as resulting from ageing and increased cell turnover (3, 4, 17, 24). These data suggest that founder genomic events occur within an environmental context possibly attributable to exposure to gastric acid (3, 4, 17), but this is not the major process contributing to mutational diversity in the growing neoplasm.

Figure 4.

Temporal and spatial dissection of mutation spectra in EAC samples. A, Stacked barplot showing the fraction of early mutations (trunk) and late mutations (branch) accounted for by each of the six mutation types in all M-seq samples and per case. The number of mutations analyzed is displayed on top of each bar. The difference between the spectra for trunk and branch mutations across all cases was assessed using a χ2 test. For specific mutation types, a Fisher’s exact test was used, and significant p values are shown. B, Stacked barplot showing the fraction of pre-chemotherapy mutations and post-chemotherapy mutations accounted for by each of the six mutation types in all M-seq samples and per case. The number of mutations analyzed is displayed on top of each bar. The difference between the spectra for trunk and branch mutations across all cases was assessed using a χ2 test. For specific mutation types, a Fisher’s exact test was used, and significant p values are shown. C, Barplot showing platinum signature enrichment odds ratio for pre-chemotherapy (red bars) and post-chemotherapy (green bars) mutations for M-seq samples. The platinum signature encompasses C>A in CpC context (25). 95% confidence intervals for Fisher’s exact test are indicated. D, A model of tumor progression in EAC. Inferring the evolutionary trajectories of EAC tumors through NAC by M-seq, identifying early and late mutational processes and the selective pressure of platinum treatment.

Clonal evolution and mutational processes with platinum chemotherapy

Next we assessed the impact of platinum chemotherapy on the somatic mutational landscape. In two tumors (EAC005 and EAC015) we observed that post-chemotherapy regions clustered separately as a monophyletic group (indicating a shared common ancestor). In the remaining tumors paraphyly was observed whereby pre- and post-chemotherapy regions clustered together. Interestingly, in this small cohort, tumors EAC005 and EAC015, which had a poor response to chemotherapy (Supplementary Table S2), exhibited monophyly with clustering of post-chemotherapy tumor regions from a shared common ancestor (Supplementary Fig. S3), consistent with a common genomic event conferring resistance to therapy in these tumors.

We then assessed whether there was an identifiable genomic signature resulting from platinum exposure in residual disease after NAC. 5 out of 8 samples were analyzed following chemotherapy as the remaining three tumors had responded well to treatment with low tumor purity levels in the post chemotherapy regions, rendering analysis intractable. We identified statistically significant shifts in the mutation spectra when comparing pre- to post-chemotherapy somatic mutations (p=0.0005) with a significant decrease in the proportion of C>T mutations (p=0.007) and an increase in C>A mutations (p=0.01) (Fig. 4B). In keeping with the findings of Meier and colleagues, who identified the presence of a platinum signature, with an enrichment of C>A mutations within a CpC context, following platinum treatment in C.elegans (25), we observed this specific mutational signature when the post NAC tumors were analyzed together (p=0.005) (Fig. 4C). EAC005 was removed from the analysis as only 18 mutations were found to be unique to post-chemotherapy tumor regions with an absence of any C>A mutations, thereby preventing calculation of enrichment at CpC sites. Additionally, there was a trend towards increased numbers of small indels in samples obtained post platinum treatment (p=0.098), but we did not observe a significant change in the mutational load of these tumors following NAC. Taken together, these data support the findings of the waning of the CTT signature in the branches and the iatrogenic impact of platinum therapy upon cancer evolution (Fig. 4D).

DISCUSSION

Tracking how EACs evolve during the selective pressure of platinum NAC reveals the timing of key somatic events and mutational processes. We identified an enrichment of category 1 driver events occurring in the trunk of the phylogenetic trees. With the exception of PDGFR, the remaining category 1 drivers were tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, CDK2NA, NF1, EXT2, DICER1, CDH1 that are therapeutically difficult to target. However, for each patient within the cohort, there was at least one ubiquitously detected amplification, containing a potentially targetable driver oncogene persisting through NAC. This is supportive of a progression model of EAC (Fig. 4D) where early CIN contributes to amplification of oncogenes early in tumor evolution which may be selected for (26), and contribute to tumor progression, similar to our recent findings in Papillary Renal Carcinoma (27). However, some of these amplifications may have occurred via breakage fusion bridges and chromothripsis, resulting in double minute chromosomes which may be relatively resistant to targeted therapeutics (17).

In keeping with other studies we detected T>G mutations at CTT sites (3, 4, 17). Our analysis confirms that this signature is enriched early in tumor evolution, occurring in all tumor regions, prior to branched evolution. Interestingly, we observed a significant reduction in this mutational process in the late (branched) mutations with an associated relative increase in C>T at CpG sites, consistent with findings in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (11). This further highlights the benefit of multi-region sampling and provides evidence that distinct mutational processes operate during tumor initiation compared to those impacting mutational burden later in the disease course.

A number of putative driver mutations identified by Dulak et al, SMAD4, TLR4, SLC39A12, TLL1, EYS, NUAK1 and DOCK2 (3) were identified subclonally in our cohort of tumors suggesting these frequently occur later in tumor evolution. Many of these driver mutations resulted in an illusion of clonality, highlighting the importance of considering regional intratumoral heterogeneity in this tumor type in order to fully dissect the evolutionary history of these tumors and to more accurately identify fully clonal events which may serve as tractable therapeutic targets. Although M-seq captures more tumor diversity than single biopsies, with almost double the number of non-silent mutations detected compared to a single biopsy in this cohort, it still only samples a small fraction of the total tumor volume. Hence, this approach is still expected to underestimate the number of subclones present within a given tumor, limiting the resolution of the phylogenetic trees (11, 12).

Whilst it is difficult to discern the true extent of heterogeneity, using a M-seq approach we observed that tumors that were more heterogeneous as determined by an ITH index appeared to have a worse response to NAC in our cohort. However, given the limited number of cases in our cohort, our observations should be confirmed in an appropriately powered prospective cohort study, given the importance of defining predictive markers to determine response to chemotherapy in EAC. Furthermore, findings of a platinum scar post NAC, highlights the need to understand the selective pressures of platinum chemotherapy on genetic diversity and the iatrogenic impact of treatment upon tumor evolution. Platinum preferentially cross-links G-G nucleotides at presumably random sites throughout the genome, and subsequent DNA repair using translesion DNA polymerases has a tendency to incorporate a wrong base, resulting in a single point mutation in a GpG or CpC context (28). The observation that all patients, including those who derived limited clinical benefit from NAC, harbored residual disease with an increase in C>A mutations in a CpC context, known to occur in model organisms following platinum exposure, further emphasizes the importance of deciphering those patients who will not derive benefit from mutagenic cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Using M-seq we have identified considerable heterogeneity of non-silent mutations and the presence of subclonal driver mutations indicating that the incidence of driver mutations from single EAC samples may be underestimated, similar to recent observations in other tumor types. We find that mutations in TP53 as well as mutations in other tumor suppressor genes such as CDKN2A are early events, likely occurring before genome doubling, which was also found to be a ubiquitous event in all tumors. All tumors exhibit CIN and harbor considerable heterogeneity at the copy number level. Despite this emerging chaos, many amplified oncogenes are ubiquitous throughout the tumor, unperturbed by cytotoxics and may represent vulnerabilities suitable for therapeutic intervention. Longitudinal studies in the setting of NAC are required to decipher the relationships between ITH and cytotoxic response and recurrence, that may support the identification of resistant disease in advance of therapy to limit the iatrogenic impact of cytotoxics on cancer evolution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

See Supplementary Data for a full description of Methods.

Patient cohort description

Eight consecutive samples from patients diagnosed with EAC who then went on to have NAC followed by definitive surgical resection (within a prospective tissue collection protocol) were obtained for sequencing. Samples were obtained with informed consent, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethics were approved by an Institutional Review Board for St Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (REC Ref. no. 04/Q0403/119). Detailed clinical characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Treatment response to chemotherapy was classified as good, intermediate and poor based on both the staging of tumors and the Mandard Tumor Regression Score (TRG) following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Poor response was classified as tumors that were upstaged and had a Mandard TRG score of 5; intermediate response, if there was no evidence that tumors had been upstaged or a Mandard TRG score of 3-4 and good response; if there was no evidence that tumors had been upstaged and a Mandard TRG score of 1-3 (29).

Multi-region whole exome sequencing

Exome capture was performed for each tumor region and matched blood germline on 1-2 μg DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Agilent). Samples were paired-end multiplex sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 to the desired average sequencing depth (approximately 90x), as described previously (11). Sequence data has been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the EBI (accession number pending). bwa mem (bwa-0.7.7) (30) was used to align raw paired end reads (100bp) to the full hg19 genomic assembly and variants were called using VarScan2 somatic (v2.3.6) (31). Orthogonal validation was performed on all identified 685 non-silent mutations from 3 tumors (EAC001, EAC003 and EAC005). These were manually reviewed and selected for deep sequencing (median coverage depth = 445) on the Ion Torrent PGM sequencer (Life Technologies) resulting in a validation rate of 96.1%.

Copy number analysis

Processed sample exome SNP and copy number data from paired tumor-normal was generated using VarScan2 (v2.3.6), and further processed using the Sequenza R package 2.1.1 (32) to provide segmented copy number data and cellularity and ploidy estimates for all samples based on the exome sequence data. Processed copy number data for each sample was divided by the sample mean ploidy, and log2 transformed. Gain and loss were defined as log2(2.5/2) and log2(1.5), respectively. Copy number heterogeneity was defined using minimum consistent regions (Supplementary Fig. S11). Amplification was defined as log2(4/2). Genome doubling was determined as previously described (33). wGII was determined as described (21).

Cancer cell fraction estimation and cluster analysis

The cancer cell fraction and mutation copy number of each mutation were estimated by integrating Sequenza-derived integer copy number and tumor purity estimates with the VAF as outlined in Lohr et al (34) and Landau et al (35). SNVs were filtered in order to remove those whose absence, or low CCF values, may be driven by copy number events. In total, across all tumor regions, 100 mutations were filtered as being driven by copy number change.

Phylogenetic tree construction

All non-silent mutations that passed validation (EAC001, EAC003 and EAC005) or further filtering (EAC006, EAC009, EAC014, EAC015 and EAC017) were considered for the purpose of determining phylogenetic trees. Trees were built using binary presence/absence matrices built from the regional distribution of variants within the tumor. The R Bioconductor package phangorn (1.99-7) (36) was utilized to perform the parsimony ratchet method (37) generating unrooted trees. Branch lengths were determined using the acctran function.

Identification and classification of driver mutations

All non-silent variants were compared against a list of potential driver genes (n=598), and classified into category 1:4 depending on the prior evidence of the variant being a driver, with category 1 representing high confidence driver mutations (see Supplementary Methods).

Temporal dissection of mutations

For each M-seq tumor, we classified each mutation as ‘early’ or ‘late’ based on whether it was located on the trunk or branch of the phylogenetic tree. All truncal mutations were classified as ‘early’ and any branch mutations as ‘late’. The variants were also split according to their occurrence pre-treatment and post-treatment with platinum chemotherapy. Variants were classed as post-treatment specific if they were absent from all regions extracted from pre-chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

This work illustrates dynamic mutational processes occurring during EAC evolution and following selective pressures of platinum exposure, emphasizing the iatrogenic impact of therapy on cancer evolution. Identification of amplifications encoding targetable oncogenes maintained through NAC, suggests the presence of stable vulnerabilities, unimpeded by cytotoxics, suitable for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgements

The results published here are in part based upon data generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas pilot project established by the NCI and NHGRI. The data were retrieved through dbGaP authorization (Accession No. phs000178.v5.p5). Information about TCGA and the investigators and institutions who constitute the TCGA research network can be found at http://cancergenome.nih.gov/.

Grants support

C.S. is a senior Cancer Research UK clinical research fellow and is funded by Cancer Research UK, the Rosetrees Trust, EU FP7 (projects PREDICT and RESPONSIFY, ID: 259303), the Prostate Cancer Foundation, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the European Research Council (THESEUS). N.Mu. is a clinical lecturer and is funded by the National Institute for Health Research. This research was funded by Academy of Medical Sciences and supported by researchers at the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals and Imperial College London Biomedical Research Centre.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program [Internet] National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda: Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/esoph.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohl H, Welch HG. The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:142–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dulak AM, Stojanov P, Peng S, Lawrence MS, Fox C, Stewart C, et al. Exome and whole-genome sequencing of esophageal adenocarcinoma identifies recurrent driver events and mutational complexity. Nat Genet. 2013;45:478–86. doi: 10.1038/ng.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver JM, Ross-Innes CS, Shannon N, Lynch AG, Forshew T, Barbera M, et al. Ordering of mutations in preinvasive disease stages of esophageal carcinogenesis. Nat Genet. 2014;46:837–43. doi: 10.1038/ng.3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies AR, Gossage JA, Zylstra J, Mattsson F, Lagergren J, Maisey N, et al. Tumor stage after neoadjuvant chemotherapy determines survival after surgery for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2983–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.9070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Zalcberg JR, Simes RJ, Barbour A, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology. 2011;12:681–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dulak AM, Schumacher SE, van Lieshout J, Imamura Y, Fox C, Shim B, et al. Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas of the esophagus, stomach, and colon exhibit distinct patterns of genome instability and oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4383–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Bettegowda C, Hutfless SM, Wang Y, David S, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:899–905. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yates LR, Campbell PJ. Evolution of the cancer genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:795–806. doi: 10.1038/nrg3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501:338–45. doi: 10.1038/nature12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerlinger M, Horswell S, Larkin J, Rowan AJ, Salm MP, Varela I, et al. Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nat Genet. 2014;46:225–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Bruin EC, McGranahan N, Mitter R, Salm M, Wedge DC, Yates L, et al. Spatial and temporal diversity in genomic instability processes defines lung cancer evolution. Science. 2014;346:251–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1253462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortmann CA, Kent DG, Nangalia J, Silber Y, Wedge DC, Grinfeld J, et al. Effect of mutation order on myeloproliferative neoplasms. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:601–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGranahan N, Favero F, de Bruin EC, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z, Swanton C. Clonal status of actionable driver events and the timing of mutational processes in cancer evolution. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:283ra54. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frankel A, Armour N, Nancarrow D, Krause L, Hayward N, Lampe G, et al. Genome-wide analysis of esophageal adenocarcinoma yields specific copy number aberrations that correlate with prognosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2014;53:324–38. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li X, Galipeau PC, Paulson TG, Sanchez CA, Arnaudo J, Liu K, et al. Temporal and spatial evolution of somatic chromosomal alterations: a case-cohort study of Barrett’s esophagus. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:114–27. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nones K, Waddell N, Wayte N, Patch AM, Bailey P, Newell F, et al. Genomic catastrophes frequently arise in esophageal adenocarcinoma and drive tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5224. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nixon KC. The Parsimony Ratchet, a New Method for Rapid Parsimony Analysis. Cladistics. 1999;15:407–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1999.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ojha J, Ayres J, Secreto C, Tschumper R, Rabe K, Van Dyke D, et al. Deep sequencing identifies genetic heterogeneity and recurrent convergent evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:492–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-580563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alcolea MP, Greulich P, Wabik A, Frede J, Simons BD, Jones PH. Differentiation imbalance in single oesophageal progenitor cells causes clonal immortalization and field change. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:615–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burrell RA, McClelland SE, Endesfelder D, Groth P, Weller MC, Shaikh N, et al. Replication stress links structural and numerical cancer chromosomal instability. Nature. 2013;494:492–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broad Institute TCGA Genome Data Analysis Center . SNP6 Copy number analysis (GISTIC2) Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; 2014. doi:10.7908/C1QJ7G5S. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Genome Analysis [Internet] Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; Cambridge: c2013. Available from: http://www.broadinstitute.org/cancer/cga/target. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier B, Cooke SL, Weiss J, Bailly AP, Alexandrov LB, Marshall J, et al. C. elegans whole-genome sequencing reveals mutational signatures related to carcinogens and DNA repair deficiency. Genome Res. 2014;24:1624–36. doi: 10.1101/gr.175547.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak MA, Komarova NL, Sengupta A, Jallepalli PV, Shih Ie M, Vogelstein B, et al. The role of chromosomal instability in tumor initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16226–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202617399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovac M, Navas C, Horswell S, Salm M, Bardella C, Rowan A, et al. Recurrent chromosomal gains and heterogeneous driver mutations characterise papillary renal cancer evolution. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6336. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemaire MA, Schwartz A, Rahmouni AR, Leng M. Interstrand cross-links are preferentially formed at the d(GC) sites in the reaction between cisdiamminedichloroplatinum (II) and DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1982–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandard AM, Dalibard F, Mandard JC, Marnay J, Henry-Amar M, Petiot JF, et al. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer. 1994;73:2680–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2680::aid-cncr2820731105>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome research. 2012;22:568–76. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Favero F, Joshi T, Marquard AM, Birkbak NJ, Krzystanek M, Li Q, et al. Sequenza: allele-specific copy number and mutation profiles from tumor sequencing data. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2015;26:64–70. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dewhurst SM, McGranahan N, Burrell RA, Rowan AJ, Gronroos E, Endesfelder D, et al. Tolerance of whole-genome doubling propagates chromosomal instability and accelerates cancer genome evolution. Cancer discovery. 2014;4:175–85. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohr JG, Stojanov P, Carter SL, Cruz-Gordillo P, Lawrence MS, Auclair D, et al. Widespread genetic heterogeneity in multiple myeloma: implications for targeted therapy. Cancer cell. 2014;25:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, McKenna A, Stevenson K, Lawrence MS, et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. 2013;152:714–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schliep KP. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:592–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nixon KC. The Parsimony Ratchet, a new method for rapid parsimony analysis. Cladistics. 1999;15:407–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1999.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.