Highlights

-

•

Recurrence should be considered in all patients with gallstone ileus.

-

•

A review of pre-operative imaging and meticulous inspection of the bowel and gallbladder should always be undertaken.

-

•

Faceted gallstones should alert the surgeon to the potential presence of a second stone.

-

•

Cholecystolithotomy should be considered as a safer alternative to cholecystectomy with fistula repair in high risk patients.

Keywords: Gallstone ileus, Recurrence, Enterolithotomy

Abstract

Introduction

Mechanical small bowel obstruction is an uncommon but important complication of cholelithiasis. Recurrent gallstone ileus has historically been considered a rare occurrence; however, the incidence is likely to be underreported and the condition carries a high mortality rate.

Presentation of case

We present a case in which a 67 year old man suffered a recurrence of gallstone ileus 10 days after his initial enterolithotomy, requiring further laparotomy.

Discussion

We review the literature to highlight potential clinical predictors as well as the benefits and pitfalls of management options in preventing repeated episodes of gallstone ileus in the same patient.

Conclusion

The presence of multifaceted gallstones and multiple stones of size ≥ 2cm on pre-operative imaging should alert the clinician to potential for recurrence.

1. Introduction

Gallstone ileus (GSI) is a mechanical obstruction of small bowel due to gallstones [1]. The incidence of this condition is considered rare but with 3268 patients undergoing surgery for GSI in the 5 year period from 2004 to 2009, it is likely that this is due to under-reporting [3]. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8.2% of cases and should therefore always be considered [8]. To highlight this, we report a case of recurrent gallstone ileus in which revisit laparotomy might have been avoided if indicators of recurrence had been actively sought, and we review the literature to discuss such predictors that can guide clinical decision making.

2. Presentation of case

A 67 year old male with a past medical history of hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and umbilical hernia was admitted with an 8 h history of severe central abdominal pain and vomiting. On examination he was afebrile with a heart rate of 125 beats per minute, blood pressure of 96/63 mm of mercury and was saturating at 91% on air. Initial blood investigations showed a white cell count of 26.8 × 109 cells/L and a serum lactate of 3.1 mmol/L. Other blood tests including amylase were normal.

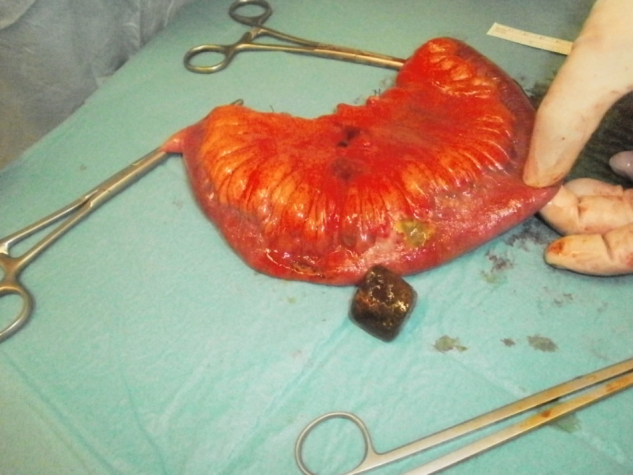

A computed tomographic (CT) scan reported features of inflammation around the gallbladder and duodenum as well as an ischaemic segment of small bowel. No pneumobilia was seen (Fig. 1A). He was taken for laparotomy where a 25 cm segment of ischaemic distal jejunum was resected and found to contain a 2 cm faceted gallstone (Fig. 2). The rest of the bowel was palpated and no stones identified. The right upper quadrant was not explored due to extensive inflammatory adhesions. Post-operative recovery was uneventful until the 10th post-operative day when he developed recurrent pain and vomiting requiring nasogastric tube aspiration.

Fig. 1.

(A) Coronal CT image obtained at initial presentation showing acute cholecystitis (filled arrow) and an ischaemic segment of small bowel (filled arrow). (B) Coronal CT image obtained on the tenth post-operative day demonstrating pneumobilia (filled arrow) and small bowel obstruction secondary to a second gallstone (filled arrow). (C) Historical axial CT image demonstrating two 2 cm faceted gallstones within the gallbladder.

Fig. 2.

Operative specimen of resected segment of ischaemic distal jejunum with patchy necrosis and a retrieved faceted gallstone.

Large volume nasogastric aspirates prompted investigation with a repeat CT scan which demonstrated pneumobilia and small bowel obstruction due to a second gallstone (Fig. 1B). On review of historical imaging, a CT scan 3 years prior to admission revealed 2 large gallstones in the gallbladder, both of which were 2 cm in diameter (Fig. 1C). He underwent further laparotomy and enterolithotomy the same day. The second 2 cm stone was found distal to the recent anastamosis. Dense inflammatory adhesions remained between the gallbladder and duodenum and it was elected not to explore this region further. He was discharged home 22 days after initial presentation.

3. Discussion

It is estimated that GSI complicates 0.4–1.5% of all cases of cholelithiasis; however the true incidence of this condition is unclear [2]. Studies suggest it accounts for 0.3–5.3% of small bowel obstructions [2]. The condition mainly affects elderly women compared to men, with a ratio of 3.5–1 [3,6]. Patients present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction including colicky abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and abdominal distension. The gallstone often obstructs intermittently, a phenomenon termed ‘tumbling obstruction’. Diagnosis can be made radiologically on the basis of intestinal obstruction, pneumobilia and changes in the position of previously noted gallstones. The widespread availability of CT has improved diagnostic rates. An absence of pneumobilia and non-calcified gallstones often clouds diagnosis and in 50% of cases diagnosis is only made at the time of laparotomy [6].

Controversy exists regarding optimal management at laparotomy [4,5]. Options include enterolithotomy alone or single stage enterolithotomy with closure of the cholecystoduodenal fistula and cholecystectomy. Reisner et al. report a mortality rate of 11.7% for simple enterolithotomy compared to 16.7% for a one stage procedure [6] and most reports favour enterolithotomy alone due to lower mortality and morbidity, although when bowel resection is required this margin of difference narrows [4,5]. The overall mortality from GSI has been steadily decreasing, with published rates of 6% [6]. This improvement in survival has been accompanied by an increase in the reporting of recurrence which is thought to occur in 5–8.2% of cases in patients undergoing enterolithotomy alone [8]. 50% of recurrences occur within one month of the index operation, but can occur up to 2 years later and indeed second and third recurrences are described [9]. Importantly, mortality from recurrence requiring surgery ranges from 12% to 20% [1,6].

We have therefore reviewed the literature to identify common features that might predict recurrence. When bilio-enteric fistulae form, gallstones pass into the bowel and are cleared in 80–90% of cases [13,14]. The most frequent sites of communication are cholecystoduodenal (69–70%), cholecystocolonic (14%) and cholecystogastric (6%) [13]. Recurrence almost always occurs as a result of residual stones in the proximal bowel or gallbladder and gallstones ≥2 cm are most likely to obstruct [6,9]. Recurrence is also reported following ERCP and endoscopic laser lithotripsy of obstructing duodenal gallstones (Bouveret’s syndrome) [11,12]. The mainstay of preventing recurrence is to take meticulous efforts pre-operatively and intra-operatively to identify and remove stones ≥2 cm. In 50% of cases where diagnosis has been made radiologically, careful review will demonstrate a second stone at another location [16,17]. Preoperative ultrasound may reveal residual stones within the gallbladder [8,18]. Where diagnosis is made at laparotomy, a cylindrical or faceted stone should alert the surgeon to potential for further stones [6,10]. Inspection and palpation of the entire small bowel and gallbladder should be undertaken [7]. Identification of stones in an inflammatory right upper quadrant mass can be difficult and here intra-operative ultrasound can be helpful [7–9].

When a second stone is identified in the bowel lumen, management is straightforward as this can be removed through the initial enterotomy or advanced distally into the colon. Recommended management of the gallbladder and the remaining bilio-enteric fistula is debatable as previously discussed [15,17]. Studies demonstrating higher mortality in patients undergoing single stage enterotomy, cholecystectomy and fistula closure compared to patients undergoing enterolithotomy alone should be interpreted with caution due to lack of randomisation [4–6]. Morbidity rates range from 27.3% to 50% for those undergoing simple enterolithotomy, to as high as 61.1–66% for a one stage operation [5]. The single stage procedure often requires complex reconstructive surgery which will be technically challenging in the presence of inflammation [17]. Our local policy recommends enterolithotomy alone in all but the most exceptional circumstances.

Where a stone ≥2 cm is identified in the gallbladder, a dilemma occurs as to the best option to prevent recurrent GSI with acceptable morbidity and mortality. One option is to perform cholecystolithotomy with primary closure or tube cholecystostomy [7]. The long term outcome of this in the setting of gallstone ileus is uncertain; what is established is that when patients with symptomatic gallbladder stones without GSI undergo percutaneous cholecystolithotomy, 31% develop recurrent stones in 2 years time with only 14% developing recurrent symptoms [19]. Fifteen percent of patients undergoing stand-alone enterolithotomy for GSI will develop biliary symptoms and 10% will require elective surgery for symptom relief [6]. In the absence of gallstones, the cholecystoduodenal fistula will spontaneously close approximately 50% of cases if the cystic duct is patent [3,6]. Therefore, cholecystolithotomy appears to offer a safe option in preventing recurrent GSI with an acceptable mortality, however more data are required on outcomes from this in the context of GSI; no data are currently available regarding the risk of recurrent GSI occurring as a result of re-formation of gallstones within the gallbladder. Some advocate the one stage procedure due to the risk of gallbladder malignancy developing in the presence of a fistula; the risk of this is controversial, with studies citing rates of between 0.82 and 25% [4,20]. Such an incidence is considered small compared to the risk of morbidity of exploring the inflammatory right upper quadrant and we agree that especially in the elderly patient, this risk may be considered acceptable.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion gallstone ileus is increasingly common, especially in the context of an aging population in developed healthcare systems, and it is likely that many cases go unreported. The presentation of this interesting condition is varied and surgical management must be tailored to the individual patient. Recurrent gallstone ileus is seen in 8.2% of these patients necessitating further surgical intervention with its associated morbidity and mortality. Having encountered this in our case we have identified strategies to minimize risk of recurrence while aiming to maintain a low morbidity and mortality. This can be achieved by careful review of preoperative imaging, intraoperative assessment of the bowel and gallbladder as well as consideration of the safer operative option of cholecystolithotomy where indicated.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The research was self funded with no external sponsors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was provided by the local research & ethics committee.

Authors contributions

J.R Apollos wrote the manuscript and edited the images.

R.V Guest proof-read and edited the manuscript.

Consent

Verbal and written consent has been obtained from the patient in question.

Guarantor

Jeyakumar Apollos is the guarantor for the study.

Contributor Information

J.R. Apollos, Email: japollos@nhs.net.

R.V. Guest, Email: rachel.guest@ed.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Buetow G.W., Glaubitz J.P., Crampton R.S. Gallstone ileus. Arch. Surg. 1963;86(3):504. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1963.01310090154029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson R., Woodward N., Diffenbaugh W., Strohl E. Gallstone obstruction of the intestine. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1967;125(3):540–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halabi W., Kang C., Ketana N., Lafaro K., Nguyen V., Stamos M. Surgery for gallstone ileus. Ann. Surg. 2014;259(2):329–335. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827eefed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravikumar R., Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann. R. Colloid Surg. Engl. 2010;92(4):279–281. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12664192076377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Sanjuán J., Casado F., Fernández M., Morales D., Naranjo A. Cholecystectomy and fistula closure versus enterolithotomy alone in gallstone ileus. Br. J. Surg. 1997;84(5):634–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reisner R.M., Cohen J.R. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am. Surg. 1994;60(6):441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers R.A.M. Surgical treatment of gallstone ileus. S. Afr. Med. J. 1976;50:2078–2080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doogue M., Choong C., Frizelle F. Recurrent gallstone ileus: underestimated. ANZ J. Surg. 1998;68(11):755–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussain Z., Ahmed M., Alexander D., Miller G., Chintapatla S. Recurrent recurrent gallstone ileus. Ann. R. Colloid Surg. Engl. 2010;92(5):4–6. doi: 10.1308/147870810X12659688851753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagger R., Sadek S., Singh K. Recurrent small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic surgery for gallstone ileus. Surg. Endosc. 2003;17(10):1679. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-4213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamauchi Y., Wakui N., Asai Y., Dan N., Takeda Y., Ueki N. Gallstone ileus following endoscopic stone extraction. Case Rep. Gastrointes. Med. 2014;2014:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/271571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alsolaiman M., Reitz C., Nawras A., Rodgers J., Maliakkal B. Bouveret’s syndrome complicated by distal gallstone ileus after laser lithotripsy using holmium: yag laser. BMC Gastroenterol. 2002;2(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piedad O., Wels P. Spontaneous internal biliary fistula, obstructive and nonobstructive types. Ann. Surg. 1972;175(1):75–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197201000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooperman A., Dickson E., ReMine W. Changing concepts in the surgical treatment of gallstone ileus. Ann. Surg. 1968;167(3):377–383. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196803000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahshaw A., Bartlett M. Choice of operation for gallstone intestinal obstruction. Ann. Surg. 1966;164(6):1051–1055. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196612000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altinkaya N., Koc Z., Alkan O., Demir S., Belli S. Multidetector computed tomography diagnosis of ileal and antropyloric gallstone ileus. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17(5):461–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzgerald J., Fitzgerald L., Maxwell-Armstrong C., Brooks A. Recurrent gallstone ileus: time to change our surgery? J. Dig. Dis. 2009;10(2):149–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2009.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies J., Sedman P., Benson E. Gallstone ileus–beware the silent second stone. Postgrad. Med. J. 1996;72(847):300–301. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.847.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donald J., Cheslyn-Curtis S., Gillams A., Russell R., Lees W. Percutaneous cholecystolithotomy: is gall stone recurrence inevitable? Gut. 1994;35(5):692–695. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.5.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clavien P.A., Richon J., Burgan S., Rohner A. Gallstone ileus. J. Br. Surg. 1990;77:737–742. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]