Abstract

Background

Early ART and virological suppression may impact on evolving antibody responses to HIV-infection. We evaluated frequency and predictors of seronegativity in infants starting early ART.

Methods

HIV-antibody results were compared between two of three arms of the Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral Therapy (CHER) trial: HIV-infected infants aged <12 weeks with CD4 ≥25% randomised to early-limited ART for 96 weeks (ART-96W) or deferred ART until clinical/immunological progression (ART-Def). HIV-infection was diagnosed by DNA PCR and RNA >1000 copies/ml. ART started at median age 7 and 23 weeks respectively. Antibody was measured from all available stored samples, ART-96W (n=109) and ART-Def (n=75), at trial week 84 (median age 92 (IQR 90.6–93.4) weeks) using 3 assays: 4th generation EIA HIV-antigen/antibody combination; HIV-1/2 rapid-antibody test and quantitative anti-gp120 IgG ELISA.

Findings

More ART-96W were seronegative than ART-Def by EIA (46% versus 11%, p<0.0001) and rapid-antibody test (53% versus 14%, p<0.0001). Anti-gp120 IgG was lower in ART-96W versus ART-Def (median 230 (133–13,129) versus 6,870 (IQR 1,706–53,645)μg/μl). Starting ART between 12-24 versus 0-12 weeks increased odds of seropositivity 13.7-fold (95%CI 3.1-60.2). All children starting ART aged >24 weeks were seropositive. Cumulative viral load to week 84 correlated with anti-gp120 IgG levels (coefficient=0.54, p<0.0001) and increased odds of seropositivity OR 1.58 (95%CI 1.1-2.3) adjusted for ART-initiation age.

Interpretation

Almost half children starting ART before aged 12 weeks were HIV-seronegative by at aged ∼2 years. HIV-antibody tests cannot be used to re-confirm HIV-diagnosis in children starting early-ART. Long-term consequences of seronegativity need further study.

Funding

Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, National Institutes of Health.

Keywords: HIV, ART, infant, antibody, diagnosis, confirmation

Introduction

In the absence of breastfeeding and early ART, infants acquire HIV either in-utero or at delivery and develop HIV-antibody responses by mean age 7.4 months[1]. Measurement of HIV-antibody is not recommended for HIV diagnosis below 18 months due to the persistence of maternal antibody[1, 2]; beyond 18 months HIV-antibody assays are used to diagnose and re-confirm HIV-infection. However, with early ART and effective viral suppression, there have been increasing case reports of infants not developing HIV-specific antibodies[3-7], probably due to reduced viral antigen exposure while maternal antibody is lost. Although rare, the decline of antibody titres has also been reported in HIV-infected children and adults on continuous ART initiated after infancy[8, 9].

The incidence of seronegativity in HIV-infected children is not known, and the management implications are potentially important as absence of detectable HIV-antibody could lead to misdiagnoses and inappropriate ART cessation. This is particularly relevant in many resource-limited settings where, for financial and logistical reasons, infants are started on ART following a single DNA PCR, and subsequent reconfirmation of HIV-status on ART using antibody tests then becomes problematic. Since current ART guidelines recommend immediate ART for all HIV-infected children under 5 years[10], it is important that the frequency and key predictors of seronegative status in HIV-infected children receiving early ART are understood, so that antibody results may be correctly interpreted, especially where HIV DNA or RNA tests are not readily available. In addition, neither the short nor long-term clinical, immunological or virological consequences of seronegativity in HIV-infected children treated early in infancy are known. This maybe particularly relevant during subsequent planned or unplanned ART interruption where pronounced viral rebound after discontinuation of ART has been reported in HIV-infected seronegative children[5, 6].

Within a week of detectable HIV-viraemia, B-cell responses can be detected as antigen-antibody complexes[11] followed in days by circulating anti-gp41 antibodies and then anti-gp120 antibodies after several weeks[12]. These binding antibodies are measured in standard diagnostic tests and, in contrast to neutralizing antibodies, do not exert selective immune pressure on HIV[13], although as HIV progresses the quantity of these binding antibodies might infer the presence of neutralizing antibodies[12]. B-cell depletion results in neutralizing antibody decline and subsequent plasma viral load rise[14], however in the context of ART initiated in early infancy HIV-seronegativity does not reflect B-cell depletion or viral eradication[8], but is likely due to lack of antigenic stimulation.

The Children with HIV Early Antiretroviral Therapy (CHER) Trial was a randomised strategy trial comparing ART started in early infancy and limited to one or two years, with deferred ART initiation[15]. In this study, we used stored samples from children in CHER to explore the impact of early versus deferred ART initiation on subsequent HIV-antibody levels, at around 2 years of age.

Materials and Methods

1. CHER trial design and participants

The design of the CHER trial, conducted from 2005 until 2011, is described in detail elsewhere[15, 16]. Briefly, 411 asymptomatic HIV-infected infants <12 weeks of age with CD4 ≥25% were randomised to 3 arms comparing early limited ART for 40 or 96 weeks (ART-40W or ART-96W) with ART deferred until clinical or immunological deterioration (ART-Def). HIV-infection was diagnosed by HIV DNA PCR and confirmed by RNA viral load >1000 copies/ml. Viral load was measured retrospectively from stored plasma at 3-6 monthly intervals. Children in ART-Def started ART based on clinical disease progression criteria (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention severe stage B/C disease) or low CD4% (<25% in infancy; <20% in older children). Trial endpoints included death, clinical, virological or immunological failure.

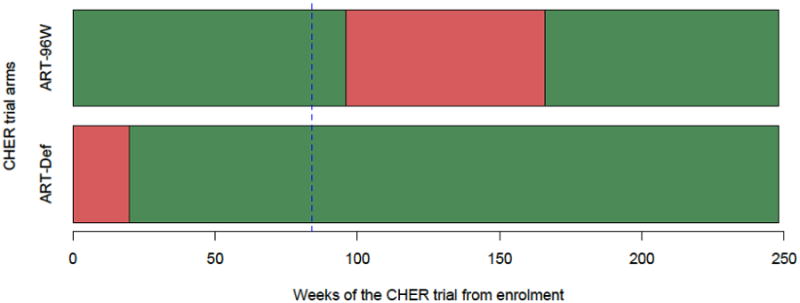

HIV-1 antibody was measured on all available stored plasma samples at trial week 84 (aged median 92 (IQR 90.6–93.4) weeks) from 2 of the 3 trial arms: ART-Def and ART-96W (Figure 1). Trial week 84 was selected since maternal antibody would no longer be detectable, and because all children in ART-96W were on ART and 89% of ART-Def had received at least 12 weeks ART.

Figure 1.

Overview of CHER trial treatment strategies and median duration on ART within arms. ART-Def = ART deferred until clinical/immunological progression; ART-96W = ART initiated at median 7 weeks of age for 96 weeks. From trial enrolment, median time to ART initiation for the 75 children examined in this study from the deferred arm, ART-Def, was 15 weeks (range 1-253). Median duration of ART-interruption for the 109 children from ART-96W was 74 weeks (range 0-102). Red = deferred or interrupted ART, Green = Start or re-start ART, dotted blue line = HIV-antibody assays performed at 84 weeks since randomization/enrolment of the CHER trial (approximately 92 weeks of age).

Use of stored samples was approved by Human Research Ethics Committees of Stellenbosch and Witwatersrand Universities where the CHER trial was conducted (M12/01/005 and 040703).

2. HIV-1 antibody assays

HIV-1 antibody was measured using plasma stored at −120°C at trial week 84. All specimens were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes and centrifuged to remove cell debris. Supernatant was used for 3 assays:

Automated serology: 4th generation microparticle enzyme immunoassay (EIA) HIV antigen/antibody combination (Abbott AXSYM system);

Rapid antibody test: HIV-1/2 qualitative immunochromographic rapid antibody test (Alere Determine®) assessed by an independent, blinded clinician;

Anti-gp120 ELISA: a sensitive in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to quantify anti-gp120 IgG and total IgG.

2.1 Automated HIV serology

Automated serology was performed at Stellenbosch University National Health Laboratory System laboratory using a 4th generation microparticle EIA HIV antigen/antibody combination (Abbott AXSYM system). The assay is performed by automatic equipment as frequently used in clinical practice, using recombinant HIV antigens and HIV p24 monoclonal antibodies coated on microparticles to capture antibodies against HIV-1/2 and HIV p24 antigen respectively[17]. “Weakly reactive” results were re-classified as seropositive.

2.2 Rapid HIV-antibody tests

Rapid HIV-antibody tests were performed by Alere Determine® HIV-1/2[18], an in-vitro, qualitative immunochromographic assay to detect antibodies to HIV-1/2 in human serum, plasma or whole blood. The results were read by an independent, blinded clinician with experience reading rapid HIV-antibody tests.

2.3 Quantitative anti-gp120 antibody ELISA

An in-house ELISA established at the Johannesburg National Institute for Communicable Diseases was used to quantify anti-gp120 HIV-antibody[19, 20]. Two ELISAs were run in parallel measuring anti-gp120 IgG (HIV-specific antibody) or total IgG. Maxisorp ELISA plates were coated overnight with either anti-human IgG (Sigma) or Consensus C gp120 protein for the respective ELISAs. Human IgG or HIV monoclonal antibodies (cloned as IgG1) were diluted serially for a 16-point standard curve (100 - 7×10-6μg/μl for IgG, 200 - 1.4×10-5μg/μl for anti-gp120). Plasma were added in 4-fold dilution series. Following sequential incubations with detection antibody, capture antibody and then Tetramethylbenzidine substrate, a VersaMAX ELISA Plate Reader detected absorbance at 450nm.

Controls

Each ELISA plate included one HIV-seropositive and one seronegative control. Plasma from 18 HIV-uninfected unexposed, age-matched healthy South African children were used to determine the specificity of the anti-gp120 ELISA. All controls were previously confirmed to be HIV-uninfected by automated serology, corroborated by maternal health records.

Statistical analysis

Welch's t-test was used to compare quantitative results between ART-Def and ART-96W. The chi-square test was used to compare binary outcomes including results classified as “weakly reactive”. Spearman's rank correlation to describe relationship between antibody quantity and cumulative viral load. Cumulative viral exposure at trial week 84 was summarised by area under the time-versus-log(viral load) curve, from randomization to week 84. This measure was calculated in each child from the available viral loads using the trapezium rule[21]. Logistic regression was used to model the relationship between the probability of a positive automated serology result and the following variables: ART-initiation age, CD4 count/percentage, and cumulative viral load. All analyses were conducted using the software R[22].

Role of funding source

The study sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or report writing. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

One hundred and nine plasma samples were available from 143 children randomised to ART-96W and 75 samples from 125 children in ART-Def. 34 ART-96W and 50 ART-Def samples were not tested because: plasma not stored (10 vs 11) or used for other reasons (1 vs 10), children lost to follow-up (11 vs 6), withdrew from study (1 vs 1) or died prior to trial week 84 (11 vs 22). The following numbers of specimens were processed for each HIV-1 antibody assay: anti-gp120 ELISA (109 ART-96W vs 75 ART-Def), automated serology (107 vs 75), rapid antibody test (101 vs 74) due to volume of sample available.

There were no significant differences between ART-96W and ART-Def children in gender, ethnicity, CD4 count/percentage or viral load at enrolment or week 84 (Table 1). As per trial design, a significant difference exists in median age at ART initiation between ART-96W and ART-Def, median 7 (7-8) weeks versus (23 (IQR 18-32) weeks respectively). Of all 184 children's samples analysed, 94% had received at least 24 weeks of ART by trial week 84. In ART-Def 67/75 (89%) had commenced ART by week 84. Of the 8 children who were not on ART, 4 started aged 3-5 years and 4 remained off ART; all 8 were seropositive.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children whose plasma were analyzed for HIV-antibody.

| ART-Def | ART-96W | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||

| No. randomised | 125 | 143 |

| No. died before samples collected | 22 | 11 |

| No. missing samples | 50 | 34 |

| No. samples analysed | 75* (41) | 109* (59) |

| Gender male | 33 (44) | 48 (44) |

| Ethnicity Black [Remaining mixed race] | 74 (99) | 105 (96) |

| No. reached primary outcome in CHER trial | 18 (24) | 16 (15) |

| Median [IQR] | ||

| CD4 at enrolment: - Absolute count (cells/μl) - Percentage |

2,039 [1,587 – 2,861] 34 [28 – 41] |

2,067 [1,520 -2,743] 35 [30 – 39] |

| CD4 at 84 wk - Abs count (cells/μl) - Percentage |

1,623 [1,330 – 2,074] 34.2 [31 – 40] |

1,641 [1,247 – 2,065] 36.9 [31.7 – 42.1] |

| Log10 viral load at enrolment | 5.88 [5.68-5.88] | 5.88 [5.72-5.88] |

| Percentage with viral load <400 copies/ml at 84 wks | 80% | 83.5% |

| Log10 viral load at 84 wks of trial in unsuppressed | 4.71 [3.78-5.16] | 4.17 [4.01-4.79] |

| Age of starting ART (weeks)** | 22.9 [18.2 – 31.2] | 7.3 [6.8 – 8.3] |

| No. started ART by 84 wks | 67 (89%) | 109 (100%) |

ART-Def = ART deferred until clinical/immunological progression; ART-96W = ART initiated at median 7 weeks of age for 96 weeks.

Difference in numbers of each group detailed in text.

Age of ART-initiation differed significantly between arms, as per CHER design.

Children in ART-96W were significantly more likely to be seronegative than ART-Def by the two commercial tests. 49 (46%) ART-96W versus 8 (11%) ART-Def were seroneagtive by automated serology (p<0.0001), and 54 (53%) versus 8 (11%) by rapid antibody test (p<0.0001)(Table 2). Although most results were concordant between automated serology and the rapid test, 9 children in ART-96W with weakly reactive automated results had negative rapid tests. The 8 seronegative children from ART-Def started ART at median age 9.9 weeks (range 7.8-22.9), with median CD4 count 1521 cells/μl (range 939–2862) or CD4% 33 (31-43) and enrolment viral load at upper limit of detection (750,000 copies/ml).

Table 2.

Comparison of automated serology (“Serology”) and rapid antibody test (“Rapid”) between ART-Def versus ART-96W at CHER trial week 84.

| ART-Def n (%) | ART-96W n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serology | Rapid | Serology | Rapid | p-value | |

| Total processed | 75 | 74 | 107 | 101 | <0.0001* |

| Reactive | 62 (83) | 64 (85) | 38 (35) | 41 (41) | |

| Weakly reactive | 5 (7) | 2 (3) | 20 (19) | 6 (6) | |

| Non-reactive | 8 (10) | 8 (11) | 49 (46) | 54 (53) | |

| Insufficient | 0 | 1 | 2 | 8 | |

| Sensitivity | 89.3% | 89.1% | 54% | 56.5% | |

Chi-square test for difference between CHER arms is p<0.0001 for both routine antibody test methods (serology and rapid antibody tests). Sensitivity of these antibody tests was calculated based on known HIV-infection in all CHER participants, diagnosed by HIV DNA PCR and confirmed with a RNA viral load >1000 copies/ml in all children at enrolment. ART-Def = ART deferred until clinical/immunological progression; ART-96W = ART initiated at median 7 weeks of age for 96 weeks. A weakly reactive test will yield a weak line present in the test area and follow-up testing is recommended to confirm an initial weakly reactive result. Unless stated, the analysis presented in this paper used “weakly reactive” results re-classified as seropositive.

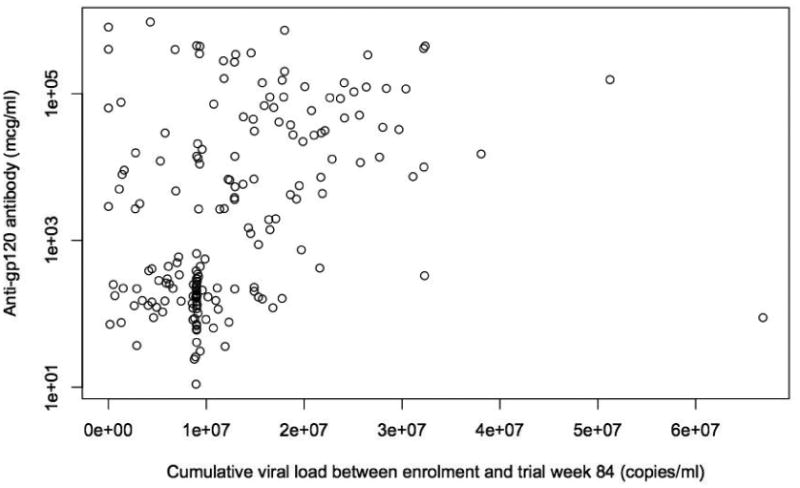

Total IgG levels were similar in both ART-96W and ART-Def (median 25,993 μg/μl [IQR 17,779-44,241] versus 25,530μg/μl [IQR 15,568-40,391], p=0.28). However, the quantitative anti-gp120 ELISA showed significant differences between ART-96W (median 230 μg/μl [IQR 133–13,129]) and ART-Def (6,870 μg/μl [IQR 1,706–53,645]), p=0.04) (Figure 2). In all children, higher anti-gp120 IgG were strongly associated with seropositivity by automated serology with median 162μg/μl [IQR 102-223] in seronegative versus 9,984 μg/μl [630-70,469] in seropositive children, p<0.0001. The 8 children from ART-Def who were not on ART by week 84 demonstrated very high anti-gp120 IgG (median 336,687 μg/μl). No anti-gp120 IgG was detected in any of the 18 HIV-uninfected controls, whereas all samples the 184 CHER children had detectable anti-gp120 IgG.

Figure 2.

Box-whisker plot comparing the distribution of HIV-specific antibody (Log10 anti-gp120 IgG μg/μl) from the quantitative anti-gp120 antibody ELISA between ART-Def and ART-96W (p=0.04) at 84 weeks of the CHER trial. ART-Def = ART deferred until clinical/immunological progression; ART-96W = ART initiated at median 7 weeks of age for 96 weeks. Anti-gp120 IgG was detectable in all children.

By automated serology, starting ART between 12-24 weeks old had 13.7-fold higher odds for seropositivity at trial week 84, compared to starting ART aged 0-12 weeks (95% CI: 3.1–60.2, p=0.001). All 33 children starting ART after 24 weeks old were seropositive at week 84. Figure 3A presents frequency of HIV-1 antibody seropositivity by automated serology at week 84 according to age at ART initation. The significant association between age at ART initiation and seropositivity also holds when the analysis is restricted to ART-96W only.

Figure 3.

A: Frequency of HIV-1 antibody seropositivity by automated serology at 84 weeks of the CHER trial (∼2 years of age) according to age of ART initation. The bar chart demonstrates the percentage of children who were seropositive at 2 years depending on whether commencing ART at 0-12, 12-24 or after 24 weeks of age (Blue = seronegative, Red = seropositive; here, a weakly reactive serology was interpreted as seropositive). B: Estimated probability of HIV seropositivity at ∼2 years of age derived from a logistic regression model fitting antibody response on age at ART initiation as linear in a logit scale. Here, the red data represents where weakly reactive serology was interpreted as seropositive, and the black data represents weakly reactive serology being seronegative; the circles represent the proportion of seropositivity in equally-sized groups for age at ART initiation; individual data-points are represented by the red or black dots at 0.0 (seronegative) or 1.0 (seropositive) on the probability y-axis. The inset table gives the odds or odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals of the two logistic regression models.

Logistic regression analysis demonstrates a strong association between serostatus and age of ART initiation (OR 1.24 95% CI 1.12-1.38), which reflects a 24% increase in the odds of seropositivity for every week before ART is initiated (Figure 3B. The effect of viral load (estimated by area-under-the-curve viral load until week 84) is also significant with OR 1.67 (95% CI 1.19-2.33), increasing the odds of seropositivity by 67% for every 100 copies of HIV RNA per militre blood. When the effect of viral load on seropositivity is adjusted for age of ART initiation, and vice-versa, both remain significant with age of ART initiation decreasing to OR 1.14 (95% CI 1.0-1.32), and viral load OR 1.59 (95% CI 1.1-2.3) (Appendix 1). CD4 count, and CD4 percentage when adjusted for viral load did not affect the odds of seropositivity. P-values for the null hypothesis that age at ART initiation doesn';t affect the log-odds are highly significant in both models, where weakly reactive was interpreted as positive or negative (p<0.0001). In addition, older age at ART initiation was also associated with increased anti-gp120 IgG (Spearman's rank correlation p=0.002, coefficient=0.35).

In all children, cumulative log-viral load from study enrolment until week 84 correlated with anti-gp120 IgG levels (Spearman's rank correlation p<0.0001, coefficient=0.54) (Figure 4). Children with high viral exposure had high HIV-specific antibodies; however children with less cumulative viral exposure (i.e. <7.8 log) showed greater variation in HIV-specific antibody levels.

Figure 4.

Relationship between quantitative anti-gp120 IgG at trial week 84 and cumulative viral load from enrolment until trial week 84. Spearman's rank correlation p<0.0001, correlation coefficient=0.54.

Neither serostatus nor quantity of anti-gp120 IgG appeared to correlate with subsequent time spent off ART after the scheduled ART-interruption at week 96 in the ART-96W arm (median 33.8 weeks [IQR 11.4 – 71.8], Spearman's rank correlation both p>0.26, coefficient=0.11). All children from ART-96W who had viral load tested exhibited HIV-1 viral rebound during ART-interruption[23].

Discussion

We have shown that nearly half of children starting ART in the first 12 weeks of life are seronegative for antibodies to HIV using commercial assays at approximately 2 years of age, compared with only 6% of infants starting ART aged 12-24 weeks and none starting ART thereafter. Furthermore, concentrations of antibodies to HIV-1 gp120 were significantly correlated with HIV-1 viral loads suggesting an important role of antigenic stimulation in antibody production.

Although HIV-seronegativity has been previously described[3-6], this is the first study to formally compare HIV antibody values taken at the same age from children who started early ART compared with deferred ART in a randomised trial. A key implication of our results is that in children with early diagnosis and treatment before 6 months, a negative antibody test is a frequent occurrence, particularly among those starting before 12 weeks. All ART-96W children experienced HIV-RNA rebound following ART interruption at week 96; thus, a negative antibody assay does not indicate absence of HIV.

For numerous reasons it may be necessary to reconfirm HIV-status in children on ART from early infancy. The accessibility, accuracy and false positive rates of HIV-1 proviral DNA PCR in some resource-limited countries are far from ideal, especially with older assays[24], and children are started on ART without confirmation of HIV status [25]. There are anecdotal reports that caregivers not infrequently doubt the initial diagnosis and request confirmation from healthcare practitioners, or purchase over-the-counter rapid antibody tests, which are increasingly available. When faced with a negative HIV-antibody result it may be difficult to convince families to continue therapy, which may ultimately be to the detriment of the child.

Given the limitations of the current commercial antibody tests in this setting, WHO stresses the importance of repeating HIV-1 DNA PCR in children just prior to initiating ART, but not waiting for the results before starting ART. If discordant with the initial DNA PCR, a third tie-breaker DNA PCR would guide any decision about stopping ART. Where confirmation of status is requested in a child started on ART before 6 months old, DNA PCR should be repeated and HIV-antibody tests should not be used. If the DNA PCR result is negative and families insist on stopping ART, interruption should be undertaken with staggered stopping for non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors[26], and might be followed with antibody testing. Preliminary data from quantitative DNA PCR analysis in CHER show that even children with negative DNA PCR after early ART have viral resurgence after stopping ART[7, 23].

In view of increased focus on early treatment strategies to limit reservoir size[27], more sensitive simple diagnostic tests are needed. Our data confirm previous studies showing that rapid HIV antibody tests are less sensitive than automated serology[28]. Considering all CHER participants tested had detectable anti-gp120 IgG, clinical tests utilising these envelope antigens might improve diagnostic accuracy alongside proviral DNA assays and be cheaper than viral load testing.

Analysis demonstrated that age of ART initiation and viral load are strong predictors of serostatus, and adjusted analyses demonstrate that they both have independent contributions. The association between cumulative plasma HIV-1 RNA and anti-gp120 IgG levels suggest that antibody production is related to HIV-1 antigen-stimulation. Whether persistence of anti-gp120 IgG represents slow decay or is a response to low levels of HIV replication, requires serial measurements alongside comprehensive analysis of cell-associated HIV DNA and RNA. Detecting low-level replication despite sustained virological control could support investigating potential novel targets for eradication strategies.

There was no correlation between levels of anti-gp120 IgG and duration of time tolerated off ART in ART-96W; however studies using quantitative measurements of DNA PCR alongside more detailed mathematical analysis of CD4 and viral load trajectories throughout ART-interruption in CHER are underway.

We cannot extrapolate our results to all children starting ART over 24 weeks old since the number of children starting ART after 6 months in CHER was low and they were more likely to be symptomatic. Other limitations include the fact that children from ART-Def had fewer samples than ART-96W, due mainly to higher death rates. However, of importance this might, if anything, increase the proportion of early treated children being seronegative. Of note we also cannot comment about HIV-antibody status among breastfeeding children starting ART, as the majority of children in CHER were formula-fed.

Due to the study design of CHER, age of ART-initiation is indistinguishable from duration of ART. However, in adults loss of antibody is not reported unless the individual was either receiving pharmacological immunosuppression or initiated ART rapidly after primary infection[29], therefore this suggests that age of ART-initiation plays an important role in the suppression of HIV-antibody.

In addition, to the age and timing of ART-initiation, HIV-antibody status and quantity is likely to depend on timing of transmission, maternal virus inoculum size and strength of immunological responses. Although routine antibody tests to confirm HIV-status cannot be recommended in this population, the strong relationship between cumulative viral load and anti-gp120 IgG levels, support a possible role for antibody quantification to assess extent of virological control or reservoir size[30]. These assays might also be used to improve clinical management since high HIV-antibody quantity or seropositivity after early-ART could be a marker of poor adherence, inappropriate dose, drug absorbance/metabolism issues, or these factors combined.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that almost half of the children starting ART within 12 weeks of birth and 6% of those starting at 12-24 weeks were seronegative by ∼2 years of age. Therefore, clinical results from automated serology and rapid antibody assays cannot be used as evidence for HIV-infection among these children. WHO is planning to update early infant diagnostic guidelines in 2015 and should take account of our findings. Clear guidance is also needed for children of caregivers seeking HIV-status confirmation of their children, along with monitoring strategies for children who interrupt ART because the caregiver questions the original diagnosis of HIV.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Pubmed was searched for all relevant articles regarding HIV-antibody seronegativity in HIV-infected children. There were no restrictions for age or language, and searches took place between 1st December 2010 and 6th June 2014. Search results revealed several case reports or case series describing HIV-infected children started on ART shortly after birth to be HIV seronegative. There was no description of frequency of HIV seronegativity, nor evidence from randomised control trials.

Added value of this study

This study presents the frequency of seronegative HIV status in HIV-infected children treated from <12 weeks of age, and the data is derived from a randomised controlled trial.

Implications of all the available evidence

HIV-antibody tests that are currently available should not be used to confirm HIV-status in HIV-infected children who initiated ART in the first 6 months of life. Future research should explore the clinical and immunological impact of HIV seronegativity.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the children and their families who participated in the CHER trial, and the staff at the Perinatal Research Unit and the Children's Infectious Disease Unit for performing the trial. We thank the virology diagnostics laboratory at Tygerberg Hospital for performing the automated serology tests.

Dr. Violari reports other from Tibotec Pharmaceuticals, grants from National Institutes of Health-Division of AIDS, grants from Columbia School of Public Health, grants from John's Hopkins University, grants from Gilead Sciences, grants from Jansen Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work;. Dr. Cotton reports grants from BMS, grants from Gilead, grants from ViiV, grants from Novartis, grants from VPM, outside the submitted work; Dr. Lewis reports funding from Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, during the conduct of the study

Footnotes

Contributors: HP, DMG and NK conceived the study. AV and MFC were the protocol co-chairs for each site of the CHER trial. KO and RP provided the specimens and necessary data from the CHER trial. HP and NM processed and analysed the specimens. HP, JL and AB performed the statistical analysis. NK, DMG, AB, AV, MFC, RC and LM contributed to the study design and data interpretation. HP prepared the manuscript and all authors have contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final draft for submission.

Conflicts of Interest: all remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Palasanthiran P, et al. Decay of transplacental human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibodies in neonates and infants. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1994;170(6):1593–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hospitalization of children born to human immunodeficiency virus-infected women in Europe. The European Collaborative Study. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1997;16(12):1151–6. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199712000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hainaut M, et al. Seroreversion in children infected with HIV type 1 who are treated in the first months of life is not a rare event. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005;41(12):1820–1. doi: 10.1086/498313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luzuriaga K, et al. Early therapy of vertical human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection: control of viral replication and absence of persistent HIV-1-specific immune responses. Journal of virology. 2000;74(15):6984–91. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6984-6991.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vigano A, et al. Failure to eradicate HIV despite fully successful HAART initiated in the first days of life. The Journal of pediatrics. 2006;148(3):389–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanchetta M, et al. Early therapy in HIV-1-infected children: effect on HIV-1 dynamics and HIV-1-specific immune response. Antiviral therapy. 2008;13(1):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler KM, et al. Rapid Viral Rebound after 4 Years of Suppressive Therapy in a Seronegative HIV-1 Infected Infant Treated from Birth. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2014 doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hare CB, et al. Seroreversion in subjects receiving antiretroviral therapy during acute/early HIV infection. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006;42(5):700–8. doi: 10.1086/500215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Sullivan CE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and human immunodeficiency virus serological responses and viral burdens in HIV-infected patients treated with HAART. Journal of medical virology. 2002;67(3):320–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomaras GD, et al. Initial B-cell responses to transmitted human immunodeficiency virus type 1: virion-binding immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG antibodies followed by plasma anti-gp41 antibodies with ineffective control of initial viremia. Journal of virology. 2008;82(24):12449–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01708-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overbaugh J, Morris L. The Antibody Response against HIV-1. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2(1):a007039. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keele BF, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(21):7552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang KH, et al. B-cell depletion reveals a role for antibodies in the control of chronic HIV-1 infection. Nature communications. 2010;1:102. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Violari A, C M, Gibb DM, Babiker AG, Steyn J, Madhi SA, Jean-Philippe P, McIntyre JA. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotton MF, et al. Early time-limited antiretroviral therapy versus deferred therapy in South African infants infected with HIV: results from the children with HIV early antiretroviral (CHER) randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1555–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61409-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Division AD. HIV Ag/Ab Combo (IVD REF 2G83-20) A.A. System; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Determine A. Alere Determine HIV-1/2 (240795/R6) Alere; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray ES, et al. The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4+ T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. Journal of virology. 2011;85(10):4828–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, et al. Analysis of neutralization specificities in polyclonal sera derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. Journal of virology. 2009;83(2):1045–59. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01992-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley KF, H M, Bence SJ. Mathematical Methods for Physics and Engineering. Cambridge: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. URL. http://www R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Payne H, W S, Otwombe K, Hsaio M, Callard R, Babiker A, Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, Klein N. Conference of Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Seattle: 2015. Early ART-initiation and sustained virological suppression in children improves HIV-1 proviral DNA reservoir reduction: Evidence from the CHER Trial. 2015. Oral abstract #35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lilian RR, et al. Early diagnosis of in utero and intrapartum HIV infection in infants prior to 6 weeks of age. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50(7):2373–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00431-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundmann N, I P, Stringer J, Wilfert C. Presumptive diagnosis of severe HIV infection to determine the need for antiretroviral therapy in children less than 18 months of age. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2011;89:513–520. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.085977. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geretti AM, et al. Sensitive assessment of the virologic outcomes of stopping and restarting non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e69266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luzuriaga K, et al. Reduced HIV Reservoirs After Early Treatment HIV-1 Proviral Reservoirs Decay Continously Under Sustained Virologic Control in Early-Treated HIV-1- Infected Children. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claassen M, et al. Pitfalls with rapid HIV antibody testing in HIV-infected children in the Western Cape, South Africa. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2006;37(1):68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saez-Cirion A, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9(3):e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burbelo PD, et al. HIV antibody characterization as a method to quantify reservoir size during curative interventions. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;209(10):1613–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.