Abstract

Lysosomes are becoming increasingly recognized as a hub that integrates diverse signals in order to control multiple aspects of cell physiology. This is illustrated by the discovery of a growing number of lysosome-localized proteins that respond to changes in growth factor and nutrient availability to regulate mTORC1 signaling as well as the identification of MiT/TFE transcription factors (MITF, TFEB and TFE3) as proteins that shuttle between lysosomes and the nucleus to elicit a transcriptional response to ongoing changes in lysosome status. These findings have been paralleled by advances in human genetics that connect mutations in genes involved in lysosomal signaling to a broad range of human illnesses ranging from cancer to neurological disease. This review summarizes these new discoveries at the interface between lysosome cell biology and human disease.

Introduction

Lysosomes degrade and recycle a broad range of macromolecules. This fulfills a housekeeping function and serves as an important source of nutrients. To meet these demands, the lysosomal lumen possesses an array of hydrolytic enzymes that digest complex biological macromolecules to regenerate the basic building blocks of cells. The diverse collection of proteins that are required to support these degradative functions of lysosomes is illustrated by the >50 distinct human diseases (collectively known as lysosomal storage disorders) that arise due to mutations that affect the ability of lysosomes to degrade and recycle their many substrates (reviewed in: [1–3]. While the digestive role of lysosomes is of unquestionable importance, the emergence of signaling functions for lysosomes demonstrates an even broader influence of lysosomes on cellular physiology that has an impact on a wide range of human diseases that extends beyond the lysosome storage diseases that have traditionally been associated with the dysfunction of this organelle. This review thus focuses on emerging aspects of lysosome-localized regulation of mTORC1 signaling and the lysosome-to-nucleus signaling mediated by MiT/TFE transcription factors. The contributions of such signaling to diverse physiological processes is further highlighted by the increasing number of human illnesses that arise due to mutations in the genes encoding lysosome-localized signaling proteins.

Lysosomes coordinate mTORC1 signaling

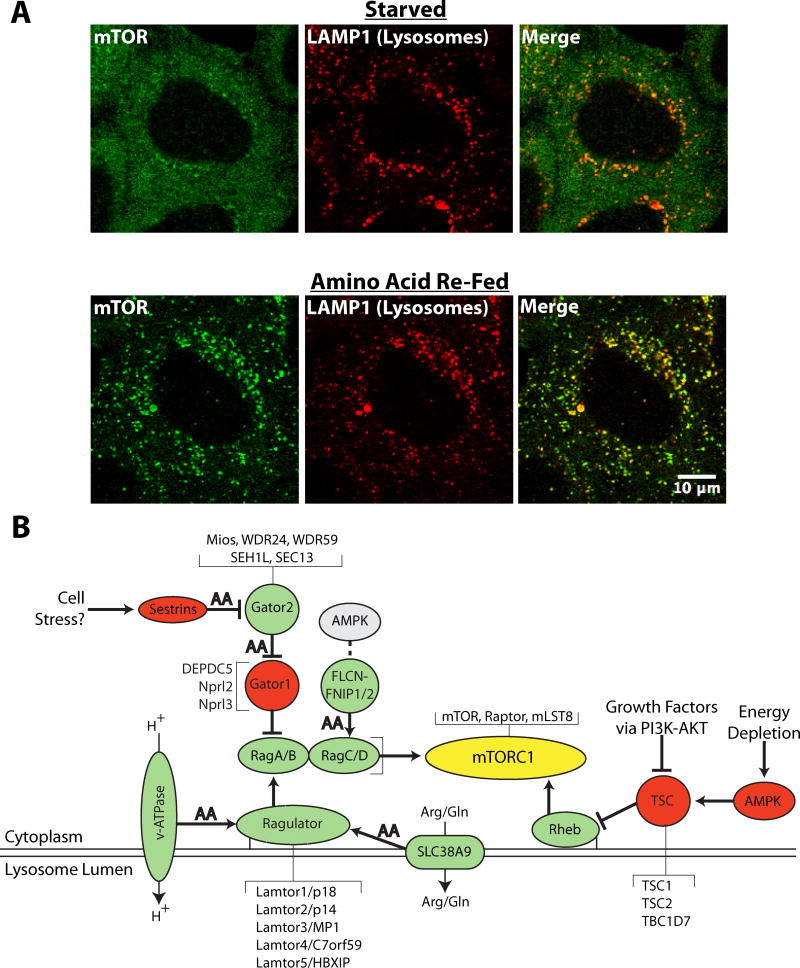

The mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) signaling pathway plays a broad role in the regulation of cell metabolism and growth [5–7]. mTORC1 activity is influenced by multiple inputs including growth factor signaling and the intracellular abundance of: ATP, oxygen, glucose and amino acids to control the balance between anabolic processes such as protein translation and catabolic cellular processes such as autophagy and lysosome biogenesis. While the signaling functions of mTORC1 have long been appreciated, lysosomes have more recently been identified as the major intracellular site where growth factor and nutrient signals converge to activate mTORC1 (Figure 1). The following sections will: 1) Summarize the lysosome-localized actions of Rheb and Rag GTPases that act in parallel to ensure that maximal mTORC1 activation is coordinated with growth factor and nutrient availability (Figure 1); and 2) Describe how mutations in such lysosome-localized signaling proteins contribute to human disease (Table 1). While this review focuses specifically on links between lysosomal signaling mechanisms and human disease, many aspects of the lysosomal nutrient sensing pathways and their links to the Tor kinase are evolutionarily conserved and investigation of these processes in model organisms has greatly contributed to our understanding of such pathways [4].

Figure 1. Multiple signals converge on the surface of lysosomes to regulate mTORC1 activity.

A) Confocal imaging reveals the dramatic recruitment of mTOR (green) to lysosomes (LAMP1, red) following the acute re-feeding (20 minutes) of amino acid starved (2 hours) HeLa cells (scale bar = 10μm, Image provided by Agnes Roczniak-Ferguson). B) This schematic diagram depicts key lysosome localized proteins that coordinate the regulation of mTORC1 activity in response to ongoing changes in nutrient, energy and growth factor availability. Proteins or protein complexes that positively and negatively contribute to mTORC1 activity are shaded green and red respectively. Arrows indicate the actions of specific proteins/protein complexes on their immediate downstream targets (pointed arrows = stimulation of target; blunt arrows = inhibition of target). “AA” indicates sites that have been identified as targets of regulation by amino acid availability.

Table 1.

Summary of genes encoding lysosomal signaling proteins with established roles in human disease.

| Gene | Disease | Inheritance/Genetic Mechanism | Molecular Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSC1 | Tuberous Sclerosis Lymphangioleiomyomatosis | Autosomal | Component of TSC Rheb GAP complex |

| TSC2 | Tuberous Sclerosis Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Cancer | Autosomal Dominant | Rheb-GAP |

| TBC1D7 | Megalencephaly Intellectual Disability Migraine susceptibility? | Autosomal Recessive | Component of TSC Rheb GAP complex |

| DEPDC5 | Familial Focal Epilepsy Hemimegalencephaly Cancer |

Autosomal Dominant – Second hit mutation in affected cells Somatic Mutations |

Component of GATOR1 – RagA/B GAP complex |

| Nprl2 | Cancer | Mutations in various tumors and cancer-derived cell lines | Component of GATOR1 – RagA/B GAP complex |

| LAMTOR2/p14 | Primary Immunodeficiency with short stature and hypopigmentation | Autosomal recessive – Reduced expression. | Component of Ragulator–RagA/B GEF |

| VMA21 | X-Linked Myopathy with Excessive Autophagy | X-linked, hypomorphic mutations | Chaperone for V-ATPase assembly |

| FLCN | Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome | Autosomal dominant (loss-of-heterozygosity in affected tissue) | RagC GAP |

| TFEB | Renal Carcinoma | Chromosomal translocation (somatic) | Transcription factor |

| TFE3 | Renal Carcinoma; Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Chromosomal translocation (somatic) | Transcription factor |

| MITF | Melanoma; Renal Carcinoma | Chromosomal translocation (somatic); also point mutation | Transcription factor |

Regulation of mTORC1 activation by Rheb

The kinase activity of mTORC1 is stimulated by direct interactions of mTOR with the GTP-bound form of the Rheb GTPase [8], a protein that resides on the cytoplasmic surface of lysosomes [9]. This interaction is inhibited by the Rheb-GTPase activating protein (GAP) activity of the tuberous sclerosis protein complex (TSC) that is formed by the TSC1, TSC2 and TBC1D7 proteins [10]. The actual GAP activity of this trimeric complex is mediated by TSC2 while both TSC1 and TBC1D7 are critical for TSC complex stability [10,11]. Growth factors, such as insulin, stimulate mTORC1 activity via the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-PI3K-AKT signaling pathway that culminates in the AKT-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 [12–14]. This phosphorylation disrupts TSC-Rheb interactions and causes TSC to dissociate from the surface of lysosomes [15]. Conversely, under conditions of energy stress, the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) suppresses mTORC1 activity by phosphorylating a different site on TSC2 that results in enhanced GAP activity towards Rheb [16]. Thus, regulating the lysosomal localization and Rheb-GAP activity of a complex comprising TSC1-TSC2-TBC1D7 is of key importance for controlling mTORC1 signaling.

Rheb hyperactivation results in diseases of uncontrolled cell growth

Inactivating mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 (also known as hamartin and tuberin respectively) cause both tuberous sclerosis complex and lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). These diseases are characterized by hyperactive mTORC1 signaling and the aberrant growth of cells in multiple tissues [17,18]. The neurological consequences of tuberous sclerosis complex can be severe and include seizures in the majority of patients along with varying degrees of cognitive impairment and strong autism predisposition [17,19]. The causative role of excessive mTOR activity in epilepsy is further supported by the recent identification of somatic activating mTOR mutations in the brains of patients suffering from focal cortical dysplasia type II, a form of epilepsy that is often resistant to anticonvulsant medications [20]. Human genetic studies within the last 2 years have additionally identified rare loss-of-function mutations in TBC1D7 that do not cause the full range of tuberous sclerosis complex symptoms but nonetheless result in excessive mTORC1 activity and the development of megalencephaly combined with intellectual disability [21,22]. There is also a potential link between TBC1D7 and migraine susceptibility [23]. Additional studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms that lead to the multiple distinct human diseases that arise from TSC1, TSC2 and TBC1D7 mutations and their potential relevance to signaling from the lysosome. In addition to the direct consequences of mutations in the genes encoding TSC proteins, this lysosome-localized protein complex is also a downstream target of numerous oncogenes (including: RTKS, PI3K, AKT, Ras, Raf) and tumor suppressors (including: PTEN, NF1, LKB1) whose mutations collectively contribute to the elevation of mTORC1 signaling in a large fraction of human cancers [5,24]. mTOR as well as its upstream regulators thus represent a potentially important therapeutic target in a wide range of diseases that are characterized by hyperactive mTORC1 signaling. As proof of principle, cancer patients have recently been identified that exhibit exceptional responses to mTORC1 inhibitors that have been attributed to the major roles played by specific mTORC1 pathway mutations in driving the growth of their tumors [25–27].

Acute regulation of the Rag GTPases controls the recruitment of mTORC1 to lysosomes

Rag GTPases assemble as heterodimers made up of either RagA or RagB bound to RagC or RagD that localize to the cytoplasmic surface of lysosomes. Recruitment of mTORC1 to the surface of lysosomes through interactions with Rag heterodimers positively regulates mTORC1 activity by bringing mTOR into proximity with Rheb [28–30]. As Rag-mediated recruitment of mTORC1 to lysosomes is tightly regulated by intracellular amino acid availability (Figure 1), considerable interest is currently focused on the mechanisms whereby amino acid availability regulates the Rag GTPases.

The nucleotide status of each individual Rag protein within a Rag heterodimer influences mTORC1 recruitment to lysosomes with the most active form represented by the combination of RagA/BGTP-RagC/DGDP[29]. A membrane anchored complex, the Ragulator, made up of Late Endosomal/Lysosomal Adaptor, MAPK And MTOR Activator 1 (LAMTOR1/p18), LAMTOR2/p14, LAMTOR3/MP1, LAMTOR4/C7orf59 and LAMTOR5/HBXIP tethers Rag heterodimers to the surface of lysosomes and also acts as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Rag A/B [28,31]. This function of the Ragulator is intimately dependent on lysosome status via physical interactions with the V-ATPase [31]. Both the V-ATPase as well as the proton gradient that it generates are required for the amino acid stimulated GEF activity of Ragulator towards RagA/B [31]. In addition to their role in the mTORC1 pathway, several Ragulator components (LAMTOR1/p18, LAMTOR2/p14, LAMTOR3/MP1) were also separately identified as a scaffold for the recruitment of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) to the surface of late endosomes-lysosomes [32,33]. It remains to be determined whether this represents a mechanism for cross-talk between MAPK and mTORC1 signaling pathways or more general roles for lysosomes as either regulators or targets of MAPK signaling.

The active, GTP-bound, state of RagA/B is opposed by the GAP activity of a separate lysosome-localized complex, GATOR1, made up of Nprl2, Nprl3 and DEPDC5 [34]. This activity of GATOR1 is in turn negatively regulated by a poorly understood pentameric complex (comprised of Sec13, Seh1l, Mios, Wdr24 and Wdr59) known as GATOR2 [34,35,36]. While the specific mechanisms of GATOR2 function remain uncertain, this complex is predicted to have structural similarity to other protein complexes that form coats at membrane interfaces such as the COPII coat and nuclear pores [37]. Indeed, in addition to functioning in GATOR2, Sec13 is also part of both COPII coats and nuclear pores while Seh1l has shared roles in both GATOR2 and nuclear pore complexes. GATOR2 is regulated by interactions with the sestrins that are controlled by amino acid availability [35,36] As sestrins also independently inhibit mTORC1 in response responses to various cellular stresses via an AMPK-TSC2 dependent mechanism [38], there is the potential for cross talk between these pathways.

Additional Rag regulation occurs via a dimeric complex made up of folliculin (FLCN) and either of the homologous FLCN-interacting proteins 1 or 2 (FNIP1/2) that interacts directly with the GTPase domain of RagA/B in a nutrient regulated manner [39]. Surprisingly, given an FLCN crystal structure [40] and subsequent bioinformatics analysis [41] that predicted that the major folded domain of both FLCN and FNIP1/2 most closely resembles the DENN family of Rab GEFs, biochemical analysis has detected GAP activity of the FLCN-FNIP complex towards RagC/D [42]. As FNIP1/2 also interacts strongly with AMPK [43,44] and FLCN depleted cells exhibit elevated AMPK signaling [45], the FLCN-FNIP1/2 complex may further serve to mediate cross talk between AMPK and mTORC1 signaling pathways.

The precise mechanisms whereby specific intracellular amino acids (leucine, glutamine and arginine in particular) are sensed remain unclear [46] but amino acid responsiveness of mTORC1 signaling is at least in part dependent on SLC38A9, an arginine and/or glutamine transporter of the lysosomal membrane that co-purifies with the Ragulator and the Rags [47,48]. Physical interactions between the lysosomal V-ATPase with multiple Ragulator subunits also contribute to amino acid sensing mechanisms [31,49]. While Rags play a prominent role in communicating amino acid availability to mTORC1, RagA/B knockout cells were recently shown to retain a residual responsiveness of mTORC1 to glutamine that is dependent on the Arf1 GTPase [50]. Thus, multiple mechanisms appear to function in parallel to support the amino acid dependence of mTORC1 signaling.

Rag GTPase dysregulation and human disease

Defects in the ability of lysosomes to regulate Rag GTPases in response to changes in intracellular amino acid availability have recently been linked to several human diseases. Loss-of-function FLCN mutations cause Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, a disease characterized by the growth of hair follicle tumors (fibrofolliculomas), lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothorax (collapsed lung) and a high incidence of renal carcinoma [51]. Exome sequencing also recently identified an FLCN mutation in combination with a TSC2 mutation in anaplastic thyroid cancer with dysregulated mTORC1 signaling and robust responsiveness to treatment with mTORC1 inhibitors [27]. The extent to which such sporadic FLCN mutations contribute to cancers beyond Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome warrants further investigation.

The human Rag GTPase pathway is hyper-activated by loss-of-function mutations in DEPDC5 and Nprl2 (components of the GATOR1 RagA/B GAP). DEPDC5 mutations cause multiple neurological defects including: familial focal epilepsy, abnormal neuron growth and brain malformations such as hemimegalencephaly [52–56]. Loss of DEPDC5 thus shares mechanistic and neurologic similarities with TSC mutations that also result in excessive mTORC1 activity and seizure susceptibility. Meanwhile, NPRL2 has a tumor suppressor function and deletions of this gene have been observed in multiple cancers including lung cancer and glioblastoma as well as in some cancer derived cell lines [34,57]. As NPRL2 and DEPDC5 are thought to function as part of the same RagA/B GAP complex, it is not yet clear how their mutations result in different diseases.

Point mutations in the 3′ untranslated region of the LAMTOR2/p14 (Ragulator component) gene that result in reduced protein expression were identified in members an isolated family suffering from a constellation of symptoms including: immune deficiency, hypopigmentation and short stature [58]. Characterization of cells from such patients revealed defects in the intracellular positioning of late endosomes/lyososomes [58] and subsequently the critical contributions of LAMTOR2/p14 to the recruitment of Rag GTPases to the cytoplasmic surface of lysosomes [28].

Hypomorphic mutations in VMA21, a gene encoding a chaperone that promotes V-ATPase assembly within the endoplasmic reticulum result in X-linked myopathy with excessive autophagy (XMEA) [59]. Reduced V-ATPase levels result in impaired lysosome acidification in XMEA patients. Diminished mTORC1 signaling in XMEA has also been observed and attributed to reduced generation of amino acids via lysosome-mediated proteolysis [59] but could potentially also reflect impaired transduction of amino acid-dependent signals to mTORC1.

Regulation of lysosome homeostasis by the lysosome-to-nucleus shuttling of MiT/TFE transcription factors

A major advance in the field of lysosome cell biology was the discovery that transcription factor EB (TFEB, a basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription factor) can coordinate the expression of numerous genes encoding lysosome and autophagosome proteins by binding to an E-box-like response element (CLEAR element) found within their promoters [60,61]. This ability of TFEB to regulate lysosome function has been investigated as a potential therapy for lysosomal storage diseases [62–64] as well as for the clearance of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases [65–67] and has shown promise in both cell culture and animal models.

In addition to investigating the therapeutic potential of TFEB-mediated enhancement of the lysosomal pathway, considerable progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms whereby cells normally regulate this transcription factor. Under basal conditions of intact lysosome function and adequate nutrient availability, TFEB is largely maintained in an “off” state. This is achieved by the dynamic recruitment of TFEB to the cytoplasmic surface of lysosomes via Rag GTPase interactions whereupon TFEB can be phosphorylated on serine 211 in an mTORC1-dependent manner and subsequently released from lysosomes and sequestered in the cytoplasm by phosphorylation-dependent interactions with 14-3-3 proteins [68–71]. In response to either impaired lysosome function and/or the depletion of intracellular amino acids, this cytoplasmic sequestration of TFEB is relieved and TFEB translocates to the nucleus to elicit an adaptive response [68–70]. More recently, calcineurin was identified as a phosphatase that can respond to lysosomal calcium signals to promote the nuclear localization of TFEB via dephosphorylation of serine 211 [72]. While such signaling plays a powerful role in controlling the nucleus versus cytoplasmic localization of TFEB via regulation of its phosphorylation on serine 211 [68,69], other TFEB phosphorylation sites have been characterized [61,73,74] and large scale phospho-proteomic studies (www.phosphosite.org) have identified numerous additional TFEB phosphorylation sites whose functions and relationship to lysosome status remain to be determined.

TFEB shares extensive sequence homology with transcription factor E3 (TFE3) and the microphthalmia transcription factor (MITF). Both MITF and TFE3 dimerize with TFEB (as well as each other), are regulated by lysosome status in a manner that parallels TFEB [69] and also regulate the expression of genes encoding lysosomal proteins [64,75]. MITF is phosphorylated by both MAPK [76] and Wnt [75] signaling pathways on sites that are conserved in both TFEB and TFE3, however, it remains to be determined how such phosphorylation is either spatially or functionally connected to lysosomes. In this light, the MAPK recruitment to late endosomes/lysosomes by ragulator subunits [32,33] is particularly intriguing and warrants further investigation.

MiT/TFE Transcription Factors are oncogenes

Chromosomal translocations involving the TFEB, TFE3 and MITF genes cause renal carcinoma and other cancers [77–79]. While these chromosomal translocations frequently result in the expression of a fusion protein that could theoretically cause cancer through novel gain-of-function mechanisms, specific chromosomal translocations have been identified that place TFEB expression under the control of a much stronger promoter (~60 fold up-regulation) without changing the TFEB coding sequence [79,80]. Thus, elevated expression of the wildtype TFEB protein is sufficient for the oncogenic mechanism. More subtly, point mutations that impair MITF sumoylation enhance risk for both renal carcinoma and melanoma [81]. There is also a rich literature concerning the many roles played by MITF as a master regulator of the melanocyte lineage [82]. It remains to be determined how the cancer causing effects of excessive levels of MiT/TFE transcription factors relates to their roles as regulators of lysosome function. These transcription factors also have multiple targets with cancer relevance whose regulation by lysosome status remains unknown including: E-cadherin [83], a component of adherens junctions; CDK2, a kinase that regulates the cell cycle [84]; PGC1α, a transcriptional co-activator that regulates metabolism and mitochondrial function [85]; and Met, a receptor tyrosine kinase whose activating mutations are also common in renal carcinoma [77,86].

Possible contributions of MiT/TFE transcription factors to Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

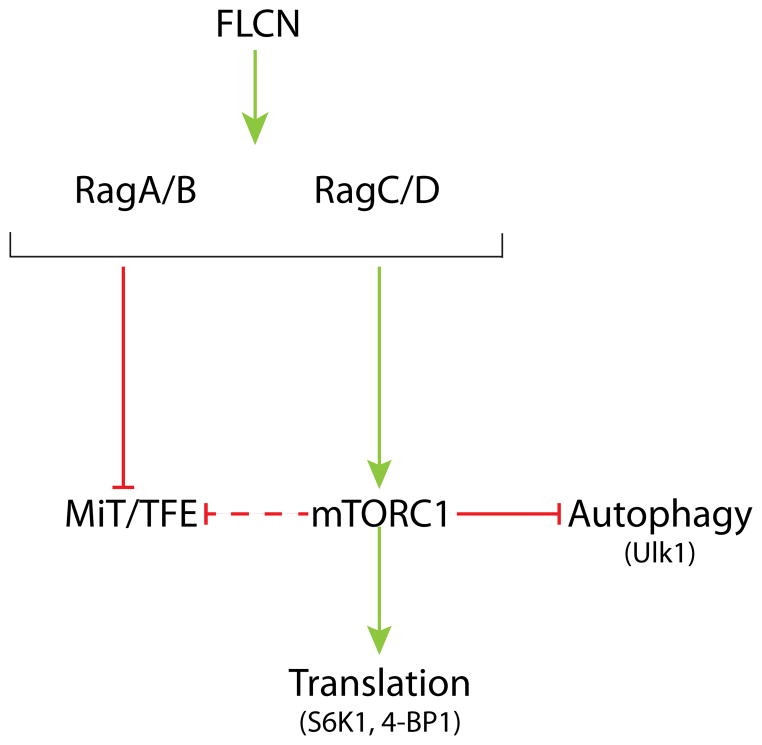

As mTORC1 activity is elevated in the majority of cancers [5,24], it is counterintuitive that FLCN is both a tumor suppressor in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome as well as a positive regulator of mTORC1 activity via direct Rag interactions [39,42]. However, as over-expression of MiT-TFE transcription factors causes cancer independent of mutations to canonical upstream components of the mTORC1 signaling pathway [77,78], the increased nuclear levels of MiT-TFE transcription factors may be a more important contributor to tumor growth in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome than the negative effects of FLCN depletion on mTORC1 signaling [39,42]. Indeed, enhanced nuclear localization of MiT-TFE proteins has been widely observed in FLCN-depleted cells [39,87,88], while effects on the mTORC1 pathway vary dramatically depending on cell culture versus in vivo tumor contexts and may reflect long term compensatory changes required for neoplastic growth [89–91]. The exquisite sensitivity of MiT/TFE nuclear abundance to FLCN loss may arise from the double dependence of MiT/TFE proteins on the Rag GTPases for their negative regulation (Figure 2). Inhibition of the nuclear localization of MiT/TFE proteins requires Rags for both their own recruitment to lysosomes (a prerequisite for their mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation) as well as for the lysosomal recruitment and activation of mTORC1 whose kinase activity is required for MiT/TFE phosphorylation and cytoplasmic sequestration [69,71]. In contrast, other key mTORC1 targets such as ribosomal protein S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 are directly recruited to mTORC1 via their direct binding to the raptor subunit [92,93] and thus do not exhibit a synergistic dependence on the Rags for both their mTORC1 recruitment and phosphorylation. It has recently been reported that cells from RagA/B conditional knockout mice exhibit excessive cell growth/proliferation [94,95]. Based on the model outlined above, excess MiT/TFE activity represents a candidate for explaining these unexpected phenotypes.

Figure 2. MiT/TFE transcription factors are regulated by Rag GTPases via both direct and mTORC1-dependent mechanisms.

This schematic diagram summarizes the synergistic regulation of MiT/TFE transcription factors by Rag GTPases through both the direct Rag-MiT/TFE interactions that recruit these transcription factors to lysosomes as wells as the role played by the Rags in the activation of mTORC1 and subsequent MiT/TFE phosphorylation. In contrast, mTORC1 targets involved in the regulation of translation and autophagy do not exhibit direct Rag interactions. Green arrows = positive regulation; Red arrows = inhibition.

Conclusions

Lysosomes serve as a platform for a growing collection of proteins that integrate multiple signals that control the balance between anabolic and catabolic cellular processes. mTORC1 activity is the major output of growth factor signaling and nutrient sensing mechanisms that converge at the lysosome that is in turn influenced at multiple levels by energy availability via AMPK. The MiT-TFE transcription factors are regulated by lysosome status through a dual mechanism that involves both a direct interaction with the lysosome-localized Rag GTPases as well as their mTORC1-dependent phosphorylation. Looking towards the future, the currently high pace of discovery of lysosome-localized proteins required for mTORC1 signaling will need to be complimented with greater insight into the mechanistic basis for their actions. Such advances will provide a strong foundation for developing therapeutic tools to address the expanding range of human diseases that arise from the dysfunction of lysosome-based signaling pathways. Coming full circle back to the longstanding problem of lysosome storage disorders and their pathogenetic mechanisms, while it intuitively makes sense that the accumulation of undigested material within the lysosomal lumen can elicit adverse effects on cell health, the mechanisms that link storage of specific molecules with distinct disease pathologies or the vulnerability of different cell types to specific degradation defects is not well understood. A better understanding of the impact of lysosomal storage on lysosome-based signaling mechanisms might help to address these issues and could also offer therapeutic opportunities.

Highlights.

Lysosomes integrate multiple signals required for mTORC1 signaling.

Lysosomal signals regulate gene expression through MiT-TFE transcription factors.

Multiple diseases arise from mutations in lysosomal signaling protein genes.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Agnes Roczniak-Ferguson for her suggestions and critical reading of this manuscript. S.M.F. is supported by grants the Ellison Medical Foundation, The Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research and the National Institutes of Health (GM105718).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Platt FM, Boland B, van der Spoel AC. The cell biology of disease: Lysosomal storage disorders: The cellular impact of lysosomal dysfunction. J Cell Biol. 2012;199(5):723–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201208152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kollmann K, Uusi-Rauva K, Scifo E, Tyynela J, Jalanko A, Braulke T. Cell biology and function of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis-related proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(11):1866–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulze H, Sandhoff K. Lysosomal lipid storage diseases. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2011;3(6) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chantranupong L, Wolfson RL, Sabatini DM. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms across evolution. Cell. 2015;161(1):67–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149(2):274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albert V, Hall MN. mTOR signaling in cellular and organismal energetics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;33C:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dibble CC, Manning BD. Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(6):555–564. doi: 10.1038/ncb2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J. Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase. Curr Biol. 2005;15(8):702–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito K, Araki Y, Kontani K, Nishina H, Katada T. Novel role of the small GTPase Rheb: Its implication in endocytic pathway independent of the activation of mammalian target of rapamycin. Journal of Biochemistry. 2005;137(3):423–430. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dibble CC, Elis W, Menon S, Qin W, Klekota J, Asara JM, Finan PM, Kwiatkowski DJ, Murphy LO, Manning BD. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2012;47(4):535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17(15):1829–1834. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating TSC2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(9):658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(9):648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10(1):151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Menon S, Dibble CC, Talbott G, Hoxhaj G, Valvezan AJ, Takahashi H, Cantley LC, Manning BD. Spatial control of the TSC complex integrates insulin and nutrient regulation of mTORC1 at the lysosome. Cell. 2014;156(4):771–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.049. This study revealed that insulin signaling via the PI3K-Akt pathway positively regulates Rheb and mTORC1 by causing the release of the TSC complex from lysosome-localized interactions with Rheb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115(5):577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: From tubers to mTOR. Annals of Human Genetics. 2003;67(Pt 1):87–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henske EP, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis - a wolf in sheep’s clothing. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):3807–3816. doi: 10.1172/JCI58709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahin M. Targeted treatment trials for tuberous sclerosis and autism: No longer a dream. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2012;22(5):895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim JS, Kim WI, Kang HC, Kim SH, Park AH, Park EK, Cho YW, Kim S, Kim HM, Kim JA, Kim J, et al. Brain somatic mutations in mtor cause focal cortical dysplasia type II leading to intractable epilepsy. Nature Medicine. 2015;21(4):395–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alfaiz AA, Micale L, Mandriani B, Augello B, Pellico MT, Chrast J, Xenarios I, Zelante L, Merla G, Reymond A. TBC1D7 mutations are associated with intellectual disability, macrocrania, patellar dislocation, and celiac disease. Human Mutation. 2014;35(4):447–451. doi: 10.1002/humu.22529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capo-Chichi JM, Tcherkezian J, Hamdan FF, Decarie JC, Dobrzeniecka S, Patry L, Nadon MA, Mucha BE, Major P, Shevell M, Bencheikh BO, et al. Disruption of TBC1D7, a subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 protein complex, in intellectual disability and megalencephaly. J Med Genet. 2013;50(11):740–744. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anttila V, Winsvold BS, Gormley P, Kurth T, Bettella F, McMahon G, Kallela M, Malik R, de Vries B, Terwindt G, Medland SE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat Genet. 2013;45(8):912–917. doi: 10.1038/ng.2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelsey I, Manning BD. mTORC1 status dictates tumor response to targeted therapeutics. Sci Signal. 2013;6(294):pe31. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagle N, Grabiner BC, Van Allen EM, Hodis E, Jacobus S, Supko JG, Stewart M, Choueiri TK, Gandhi L, Cleary JM, Elfiky AA, et al. Activating mTOR mutations in a patient with an extraordinary response on a phase I trial of everolimus and pazopanib. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4(5):546–553. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grabiner BC, Nardi V, Birsoy K, Possemato R, Shen K, Sinha S, Jordan A, Beck AH, Sabatini DM. A diverse array of cancer-associated mtor mutations are hyperactivating and can predict rapamycin sensitivity. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4(5):554–563. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Wagle N, Grabiner BC, Van Allen EM, Amin-Mansour A, Taylor-Weiner A, Rosenberg M, Gray N, Barletta JA, Guo Y, Swanson SJ, Ruan DT, et al. Response and acquired resistance to everolimus in anaplastic thyroid cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(15):1426–1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403352. Characterization of a cancer with mutations in TSC2 and FLCN and its responsiveness to the therapeutic inhibition of mTORC1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141(2):290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320(5882):1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(8):935–945. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Bar-Peled L, Schweitzer LD, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM. Ragulator is a GEF for the Rag gtpases that signal amino acid levels to mtorc1. Cell. 2012;150(6):1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.032. The first identification of a protein complex that regulates the nucleotide binding status of the Rag GTPases in response to changes in intracellular amino acid availability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wunderlich W, Fialka I, Teis D, Alpi A, Pfeifer A, Parton RG, Lottspeich F, Huber LA. A novel 14-kilodalton protein interacts with the mitogen-activated protein kinase scaffold MP1 on a late endosomal/lysosomal compartment. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(4):765–776. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nada S, Hondo A, Kasai A, Koike M, Saito K, Uchiyama Y, Okada M. The novel lipid raft adaptor p18 controls endosome dynamics by anchoring the MEK-ERK pathway to late endosomes. Embo J. 2009;28(5):477–489. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34**.Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, Sabatini DM. A tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the Rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2013;340(6136):1100–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.1232044. This study introduces 2 complexes, GATOR1 and GATOR2, that act sequentially to transduce changes in intracellular amino acid availability into RagA/B inactivation when amino acid availability is limited and further reveal the loss of GATOR1 components in specific cancers. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chantranupong L, Wolfson RL, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Scaria SM, Bar-Peled L, Spooner E, Isasa M, Gygi SP, Sabatini DM. The sestrins interact with GATOR2 to negatively regulate the amino-acid-sensing pathway upstream of mTORC1. Cell Reports. 2014;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parmigiani A, Nourbakhsh A, Ding B, Wang W, Kim YC, Akopiants K, Guan KL, Karin M, Budanov AV. Sestrins inhibit mTORC1 kinase activation through the GATOR complex. Cell Reports. 2014;9(4):1281–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Algret R, Fernandez-Martinez J, Shi Y, Kim SJ, Pellarin R, Cimermancic P, Cochet E, Sali A, Chait BT, Rout MP, Dokudovskaya S. Molecular architecture and function of the SEA complex, a modulator of the TORC1 pathway. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics: MCP. 2014;13(11):2855–2870. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.039388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Budanov AV, Karin M. p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mtor signaling. Cell. 2008;134(3):451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39**.Petit CS, Roczniak-Ferguson A, Ferguson SM. Recruitment of folliculin to lysosomes supports the amino acid-dependent activation of Rag GTPases. J Cell Biol. 2013;202(7):1107–1122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307084. The first identification of a direct, lysosome-localized function for folliculin (FLCN), the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome tumor supressor, in the regulation of Rag GTPases by amino acid availability. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nookala RK, Langemeyer L, Pacitto A, Ochoa-Montano B, Donaldson JC, Blaszczyk BK, Chirgadze DY, Barr FA, Bazan JF, Blundell TL. Crystal structure of folliculin reveals a hiddenn function in genetically inherited renal cancer. Open Biol. 2012;2(8):120071. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine TP, Daniels RD, Gatta AT, Wong LH, Hayes MJ. The product of C9orf72, a gene strongly implicated in neurodegeneration, is structurally related to denn Rab-GEFs. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(4):499–503. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42**.Tsun ZY, Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Zoncu R, Wang T, Kim C, Spooner E, Sabatini DM. The folliculin tumor suppressor is a GAP for the RagC/D GTPases that signal amino acid levels to mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2013;52(4):495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.016. Data is presented in support of a specific action of folliculin-FNIP complex as an amino acid regulated RagC/D GAP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baba M, Hong SB, Sharma N, Warren MB, Nickerson ML, Iwamatsu A, Esposito D, Gillette WK, Hopkins RF, 3rd, Hartley JL, Furihata M, et al. Folliculin encoded by the BHD gene interacts with a binding protein, FNIP1, and AMPK, and is involved in AMPK and mTOR signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(42):15552–15557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603781103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hasumi H, Baba M, Hong SB, Hasumi Y, Huang Y, Yao M, Valera VA, Linehan WM, Schmidt LS. Identification and characterization of a novel folliculin-interacting protein FNIP2. Gene. 2008;415(1–2):60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan M, Gingras MC, Dunlop EA, Nouet Y, Dupuy F, Jalali Z, Possik E, Coull BJ, Kharitidi D, Dydensborg AB, Faubert B, et al. The tumor suppressor folliculin regulates AMPK-dependent metabolic transformation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2640–2650. doi: 10.1172/JCI71749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Efeyan A, Comb WC, Sabatini DM. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature. 2015;517(7534):302–310. doi: 10.1038/nature14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rebsamen M, Pochini L, Stasyk T, de Araujo ME, Galluccio M, Kandasamy RK, Snijder B, Fauster A, Rudashevskaya EL, Bruckner M, Scorzoni S, et al. SLC38A9 is a component of the lysosomal amino acid sensing machinery that controls mTORC1. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature14107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48*.Wang S, Tsun ZY, Wolfson RL, Shen K, Wyant GA, Plovanich ME, Yuan ED, Jones TD, Chantranupong L, Comb W, Wang T, et al. Metabolism. Lysosomal amino acid transporter SLC38A9 signals arginine sufficiency to mTORC1. Science. 2015;347(6218):188–194. doi: 10.1126/science.1257132. The above 2 references establish a critical role for SLC38A9, a lysosomal amino acid transporter, in the regulation of mTORC1 signaling by amino acid availability. However, they differ on whether SLC38A9 senses/transports glutamine versus arginine respectively. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zoncu R, Bar-Peled L, Efeyan A, Wang S, Sancak Y, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 senses lysosomal amino acids through an inside-out mechanism that requires the vacuolar V-ATPase. Science. 2011;334(6056):678–683. doi: 10.1126/science.1207056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jewell JL, Kim YC, Russell RC, Yu FX, Park HW, Plouffe SW, Tagliabracci VS, Guan KL. Metabolism. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science. 2015;347(6218):194–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1259472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nickerson ML, Warren MB, Toro JR, Matrosova V, Glenn G, Turner ML, Duray P, Merino M, Choyke P, Pavlovich CP, Sharma N, et al. Mutations in a novel gene lead to kidney tumors, lung wall defects, and benign tumors of the hair follicle in patients with the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dibbens LM, de Vries B, Donatello S, Heron SE, Hodgson BL, Chintawar S, Crompton DE, Hughes JN, Bellows ST, Klein KM, Callenbach PM, et al. Mutations in DEPDC5 cause familial focal epilepsy with variable foci. Nat Genet. 2013;45(5):546–551. doi: 10.1038/ng.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53*.Ishida S, Picard F, Rudolf G, Noe E, Achaz G, Thomas P, Genton P, Mundwiller E, Wolff M, Marescaux C, Miles R, et al. Mutations of DEPDC5 cause autosomal dominant focal epilepsies. Nat Genet. 2013;45(5):552–555. doi: 10.1038/ng.2601. The above two references identify DEPDC5 (GATOR1 complex component) mutations as a cause of familial focal epilepsy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.D’Gama AM, Geng Y, Couto JA, Martin B, Boyle EA, LaCoursiere CM, Hossain A, Hatem NE, Barry B, Kwiatkowski DJ, Vinters HV, et al. mTOR pathway mutations cause hemimegalencephaly and focal cortical dysplasia. Annals of Neurology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/ana.24357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scheffer IE, Heron SE, Regan BM, Mandelstam S, Crompton DE, Hodgson BL, Licchetta L, Provini F, Bisulli F, Vadlamudi L, Gecz J, et al. Mutations in mammalian target of rapamycin regulator DEPDC5 cause focal epilepsy with brain malformations. Annals of Neurology. 2014;75(5):782–787. doi: 10.1002/ana.24126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lal D, Reinthaler EM, Schubert J, Muhle H, Riesch E, Kluger G, Jabbari K, Kawalia A, Baumel C, Holthausen H, Hahn A, et al. DEPDC55 mutations in genetic focal epilepsies of childhood. Annals of Neurology. 2014;75(5):788–792. doi: 10.1002/ana.24127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ueda K, Kawashima H, Ohtani S, Deng WG, Ravoori M, Bankson J, Gao B, Girard L, Minna JD, Roth JA, Kundra V, et al. The 3p21. 3 tumor suppressor NPRL2 plays an important role in cisplatin-induced resistance in human non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9682–9690. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bohn G, Allroth A, Brandes G, Thiel J, Glocker E, Schaffer AA, Rathinam C, Taub N, Teis D, Zeidler C, Dewey RA, et al. A novel human primary immunodeficiency syndrome caused by deficiency of the endosomal adaptor protein p14. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(1):38–45. doi: 10.1038/nm1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramachandran N, Munteanu I, Wang P, Ruggieri A, Rilstone JJ, Israelian N, Naranian T, Paroutis P, Guo R, Ren ZP, Nishino I, et al. VMA21 deficiency prevents vacuolar atpase assembly and causes autophagic vacuolar myopathy. Acta Neuropathologica. 2013;125(3):439–457. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, Di Malta C, Donaudy F, Embrione V, Polishchuk RS, Banfi S, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. 2009;325(5939):473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, Garcia Arencibia M, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Erdin SU, Huynh T, Medina D, Colella P, Sardiello M, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332(6036):1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Medina DL, Fraldi A, Bouche V, Annunziata F, Mansueto G, Spampanato C, Puri C, Pignata A, Martina JA, Sardiello M, Palmieri M, et al. Transcriptional activation of lysosomal exocytosis promotes cellular clearance. Dev Cell. 2011;21(3):421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spampanato C, Feeney E, Li L, Cardone M, Lim JA, Annunziata F, Zare H, Polishchuk R, Puertollano R, Parenti G, Ballabio A, et al. Transcription factor EB (TFEB) is a new therapeutic target for pompe disease. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2013;5(5):691–706. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martina JA, Diab HI, Lishu L, Jeong AL, Patange S, Raben N, Puertollano R. The nutrient-responsive transcription factor TFE3 promotes autophagy, lysosomal biogenesis, and clearance of cellular debris. Science Signaling. 2014;7(309):ra9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Polito VA, Li H, Martini-Stoica H, Wang B, Yang L, Xu Y, Swartzlander DB, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Lee VM, Sardiello M, et al. Selective clearance of aberrant tau proteins and rescue of neurotoxicity by transcription factor EB. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2014;6(9):1142–1160. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201303671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Decressac M, Mattsson B, Weikop P, Lundblad M, Jakobsson J, Bjorklund A. TFEB-mediated autophagy rescues midbrain dopamine neurons from alpha-synuclein toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(19):E1817–1826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305623110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tsunemi T, Ashe TD, Morrison BE, Soriano KR, Au J, Roque RA, Lazarowski ER, Damian VA, Masliah E, La Spada AR. PGC-1alpha rescues huntington’s disease proteotoxicity by preventing oxidative stress and promoting TFEB function. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(142):142ra197. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martina JA, Chen Y, Gucek M, Puertollano R. mTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy. 2012;8(6):903–914. doi: 10.4161/auto.19653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69*.Roczniak-Ferguson A, Petit CS, Froehlich F, Qian S, Ky J, Angarola B, Walther TC, Ferguson SM. The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Science Signaling. 2012;5(228):ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002790. This study along with references 68 and 70 establishes that MiT/TFE transcriptions factors are recruited to the cytoplasmic surface of lysosomes and shuttle between lysosomes and the nucleus in an mTORC1-regulated manner. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Settembre C, Zoncu R, Medina DL, Vetrini F, Erdin S, Erdin S, Huynh T, Ferron M, Karsenty G, Vellard MC, Facchinetti V, et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 2012;31(5):1095–1108. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71*.Martina JA, Puertollano R. Rag GTPases mediate amino acid-dependent recruitment of TFEB and MITF to lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):475–491. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201209135. Recruitment of TFEB and MITF to lysosomes was found to occur through interactions with the GTP-bound form of RagA/B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A, De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso C, Forrester A, Settembre C, et al. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(3):288–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pena-Llopis S, Vega-Rubin-de-Celis S, Schwartz JC, Wolff NC, Tran TA, Zou L, Xie XJ, Corey DR, Brugarolas J. Regulation of TFEB and v-ATPases by mTORC1. EMBO J. 2011;30(16):3242–3258. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferron M, Settembre C, Shimazu J, Lacombe J, Kato S, Rawlings DJ, Ballabio A, Karsenty G. A RANKL-PKCbeta-TFEB signaling cascade is necessary for lysosomal biogenesis in osteoclasts. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):955–969. doi: 10.1101/gad.213827.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ploper D, Taelman VF, Robert L, Perez BS, Titz B, Chen HW, Graeber TG, von Euw E, Ribas A, De Robertis EM. MITF drives endolysosomal biogenesis and potentiates Wnt signaling in melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424576112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu M, Hemesath TJ, Takemoto CM, Horstmann MA, Wells AG, Price ER, Fisher DZ, Fisher DE. C-kit triggers dual phosphorylations, which couple activation and degradation of the essential melanocyte factor Mi. Genes Dev. 2000;14(3):301–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77*.Durinck S, Stawiski EW, Pavia-Jimenez A, Modrusan Z, Kapur P, Jaiswal BS, Zhang N, Toffessi-Tcheuyap V, Nguyen TT, Pahuja KB, Chen YJ, et al. Spectrum of diverse genomic alterations define non-clear cell renal carcinoma subtypes. Nat Genet. 2015;47(1):13–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.3146. A chromosomal translocation involving MITF was identified as a cause of renal carcinoma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kauffman EC, Ricketts CJ, Rais-Bahrami S, Yang Y, Merino MJ, Bottaro DP, Srinivasan R, Linehan WM. Molecular genetics and cellular features of TFE3 and TFEB fusion kidney cancers. Nature Reviews Urology. 2014;11(8):465–475. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Davis IJ, Hsi BL, Arroyo JD, Vargas SO, Yeh YA, Motyckova G, Valencia P, Perez-Atayde AR, Argani P, Ladanyi M, Fletcher JA, et al. Cloning of an Alpha-TFEB fusion in renal tumors harboring the t(6;11)(p21;q13) chromosome translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(10):6051–6056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931430100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuiper RP, Schepens M, Thijssen J, van Asseldonk M, van den Berg E, Bridge J, Schuuring E, Schoenmakers EF, van Kessel AG. Upregulation of the transcription factor TFEB in t(6;11)(p21;q13)-positive renal cell carcinomas due to promoter substitution. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(14):1661–1669. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yokoyama S, Woods SL, Boyle GM, Aoude LG, MacGregor S, Zismann V, Gartside M, Cust AE, Haq R, Harland M, Taylor JC, et al. A novel recurrent mutation in MITF predisposes to familial and sporadic melanoma. Nature. 2011;480(7375):99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hsiao JJ, Fisher DE. The roles of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and pigmentation in melanoma. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2014;563:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huan C, Sashital D, Hailemariam T, Kelly ML, Roman CA. Renal carcinoma-associated transcription factors TFE3 and TFEB are leukemia inhibitory factor-responsive transcription activators of E-cadherin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(34):30225–30235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Du J, Widlund HR, Horstmann MA, Ramaswamy S, Ross K, Huber WE, Nishimura EK, Golub TR, Fisher DE. Critical role of CDK2 for melanoma growth linked to its melanocyte-specific transcriptional regulation by MITF. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(6):565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Settembre C, De Cegli R, Mansueto G, Saha PK, Vetrini F, Visvikis O, Huynh T, Carissimo A, Palmer D, Klisch TJ, Wollenberg AC, et al. TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation-induced autoregulatory loop. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(6):647–658. doi: 10.1038/ncb2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tsuda M, Davis IJ, Argani P, Shukla N, McGill GG, Nagai M, Saito T, Lae M, Fisher DE, Ladanyi M. TFE3 fusions activate met signaling by transcriptional up-regulation, defining another class of tumors as candidates for therapeutic Met inhibition. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):919–929. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87*.Betschinger J, Nichols J, Dietmann S, Corrin PD, Paddison PJ, Smith A. Exit from pluripotency is gated by intracellular redistribution of the bhlh transcription factor TFE3. Cell. 2013;153(2):335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.012. FLCN and TFE3 were identified as regulators of stem cell pluripotency illustrates how signals that originate at the lysosome can have wide ranging effects on cell physiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hong SB, Oh H, Valera VA, Baba M, Schmidt LS, Linehan WM. Inactivation of the flcn tumor suppressor gene induces TFE3 transcriptional activity by increasing its nuclear localization. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hudon V, Sabourin S, Dydensborg AB, Kottis V, Ghazi A, Paquet M, Crosby K, Pomerleau V, Uetani N, Pause A. Renal tumour suppressor function of the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome gene product folliculin. J Med Genet. 2010;47(3):182–189. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hasumi Y, Baba M, Ajima R, Hasumi H, Valera VA, Klein ME, Haines DC, Merino MJ, Hong SB, Yamaguchi TP, Schmidt LS, et al. Homozygous loss of BHD causes early embryonic lethality and kidney tumor development with activation of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(44):18722–18727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908853106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nishii T, Tanabe M, Tanaka R, Matsuzawa T, Okudela K, Nozawa A, Nakatani Y, Furuya M. Unique mutation, accelerated mtor signaling and angiogenesis in the pulmonary cysts of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Pathology International. 2013;63(1):45–55. doi: 10.1111/pin.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nojima H, Tokunaga C, Eguchi S, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Yoshino K, Hara K, Tanaka N, Avruch J, Yonezawa K. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mtor) partner, Raptor, binds the mTOR substrates p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 through their TOR signaling (TOS) motif. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(18):15461–15464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schalm SS, Fingar DC, Sabatini DM, Blenis J. TOS motif-mediated Raptor binding regulates 4E-BP1 multisite phosphorylation and function. Curr Biol. 2003;13(10):797–806. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim YC, Park HW, Sciarretta S, Mo JS, Jewell JL, Russell RC, Wu X, Sadoshima J, Guan KL. Rag GTPases are cardioprotective by regulating lysosomal function. Nature Communications. 2014;5(4241) doi: 10.1038/ncomms5241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Efeyan A, Schweitzer LD, Bilate AM, Chang S, Kirak O, Lamming DW, Sabatini DM. RagA, but not RagB, is essential for embryonic development and adult mice. Dev Cell. 2014;29(3):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]