Abstract

Successful mammalian development requires descendants of single-cell zygotes to differentiate into diverse cell types even though they contain the same genetic material. Preimplantation dynamics are first driven by the necessity of reprogramming haploid parental epigenomes to reach a totipotent state. This process requires extensive erasure of epigenetic marks shortly after fertilization. During the few short days after formation of the zygote, epigenetic programs are established and are essential for the first lineage decisions and differentiation. Here we review the current understanding of DNA methylation and histone modification dynamics responsible for these early changes during mammalian preimplantation development. In particular we highlight insights that have been gained through next generation sequencing technologies comparing human embryos to other models as well as the recent discoveries of active DNA demethylation mechanisms at play during preimplantation.

From zygote to blastocyst

Mammalian preimplantation development is a time of dynamic change in which the fertilized egg undergoes cleavage divisions developing into a morula and then a blastocyst with the first two distinct cell lineages (inner cell mass and trophectoderm). This developmental period is characterized by three major transitions, each of which entails pronounced changes in the pattern of gene expression. The first transition is the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) that serves three functions: (1) to destroy oocyte-specific transcripts [e.g., H1oo, (Tanaka et al. 2001)], (2) to replace maternal transcripts that are common to the oocyte and early embryo with zygotic transcripts and (3) to facilitate the reprogramming of the early embryo by generating novel transcripts that are not expressed in the oocyte (Latham et al. 1991). In mouse, zygotic gene activation initiates during the 1-cell stage, and is clearly evident by the 2-cell stage (Latham et al. 1991, Schultz et al. 1993). Coincident with genome activation is the implementation of a chromatin-based transcriptionally-repressive state (Nothias et al. 1995, Schultz 2002) and more efficient use of TATA-less promoters (Majumder & DePamphilis 1994), which are likely to play a major role in establishing the appropriate pattern of gene expression required for successful development.

The second developmental transition is compaction, which occurs during the 8-cell stage, when the first morphological differentiation occurs due to adhesive interactions between the blastomeres generating a tightly organized and less distinct mass of cells (Fleming et al. 2001). Accompanying compaction are pronounced biochemical changes through which blastomeres acquire characteristics resembling somatic cells, reflected in such features as ion transport, metabolism, cellular architecture, and gene expression pattern (Fleming et al. 2001, Kidder & Winterhager 2001). Following compaction, cleavage divisions allocate cells to the inside of the developing morula. These inner cells are set aside between the 8-cell and 16-cell stage, and then again between the 16-cell stage and the 32-cell stage (Pedersen et al. 1986). The inner cells of the morula give rise to the inner cell mass (ICM) cells from which the embryo proper is derived, whereas the outer cells differentiate exclusively into the trophectoderm (TE), which gives rise to extraembryonic tissues (Yamanaka et al. 2006). The TE is a fluid transporting epithelium that is responsible for forming the blastocoel cavity and is essential for continued development and differentiation of the ICM (Biggers et al. 1988, Watson et al. 1990). Distinct differentiation first occurs in the blastocyst and is characterized by differences in gene expression between the ICM and TE cells (Nichols & Gardner 1984, Pesce & Scholer 2001). Additionally, by the time of implantation the primitive endoderm has differentiated from the ICM/epiblast and resides as a single cell layer on the blastocoel cavity side of the ICM/EPI (Reviewed in (Schrode et al. 2013)).

These dynamic morphological, cellular and molecular events are driven by gene expression changes facilitated by epigenetic phenomenon, including DNA methylation and histone modifications at sites throughout the genome. Below we review current understanding of the mechanisms responsible for regulation of epigenetic programming and re-programming that occur during mammalian preimplantation.

DNA methylation dynamics in the Preimplantation Mouse Embryo

In mammalian cells, the predominant form of DNA methylation occurs at CpG dinucleotides. Throughout the genome, non-promoter associated CpGs are generally found methylated. However, the majority of protein coding genes have regions of high density CpG dinucleotides termed CpG islands. In most cell types the methylation status at these promoter associated CpG islands correlate with the transcriptional activity of the locus - actively transcribed genes generally are not methylated while silenced genes are often found to be heavily methylated in the promoter island. Additionally, there is growing evidence that CpG islands found outside of transcription start sites play functional roles (Saxonov et al. 2006, Illingworth et al. 2010, Maunakea et al. 2010). While DNA methylation at gene promoters is traditionally thought to act as a binary switch (methylated = silent, unmethylated= active), it appears that CpG density, not just presence of methylation alone, also contributes to regulation of expression. For example, methylation at low CpG dense promoters still allows for transcriptional activity (Fouse et al. 2008). Furthermore, there are numerous examples, particularly of non-coding RNAs, that are transcribed although the allele is heavily methylated (Bartolomei et al. 1993, Takada et al. 2002, Sleutels et al. 2003). These examples highlight that while there are general correlations of methylation status and gene activity – individual loci vary greatly.

In mammals, the molecular machinery responsible for adding a methyl group to cytosine residues [resulting 5-methylcystosine (5mC)] has been identified as a family of DNA methyltransferases (Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Dnmt3l). Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are responsible for de novo methylation and play partially redundant but independently essential roles during early development. This includes methylation of repeat regions, imprinted loci, as well as genes involved in lineage decisions (Okano et al. 1999, Bourc’his et al. 2001, Kaneda et al. 2004). More specifically, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b help to establish de novo methylation in the blastocyst, allowing global 5mC levels to increase to that of somatic cells following implantation (Smith et al. 2012). Dnmt3a is maternally loaded in the oocyte and is the predominate methyltransferase in the oocyte and zygote (Kaneda et al. 2004, Kato et al. 2007), whereas Dnmt3b is transcribed upon zygotic genome activation (Watanabe et al. 2002) and is the primary mediator of de novo methylation during implantation (Borgel et al. 2010). Knockout studies in mice show that each of the Dnmts are required for viability (Li et al. 1992, Okano et al. 1999), highlighting the essential nature of de novo and maintenance methylation during development.

Dnmt1 has two functional transcripts that are expressed during development-Dnmt1s is expressed in somatic cells while Dnmt1o is specifically expressed as an oocyte specific form (Rouleau et al. 1992, Gaudet et al. 1998, Mertineit et al. 1998). Unlike Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, Dnmt1 maintains CpG methylation by recognizing hemimethylated DNA and methlyating the unmethlyated strand ensuring 5mC is maintained through DNA synthesis (Leonhardt et al. 1992, Arand et al. 2012). Targeting of Dnmt1 to replication foci occurs in most proliferating cells (Kishikawa et al. 2003, Bostick et al. 2007), however Dnmt1o/s is largely excluded from the nucleus during early preimplantation stages (Howell et al. 2001), likely to allow for the large scale demethylation that occurs to both haploid genomes (figures 1 and 2).

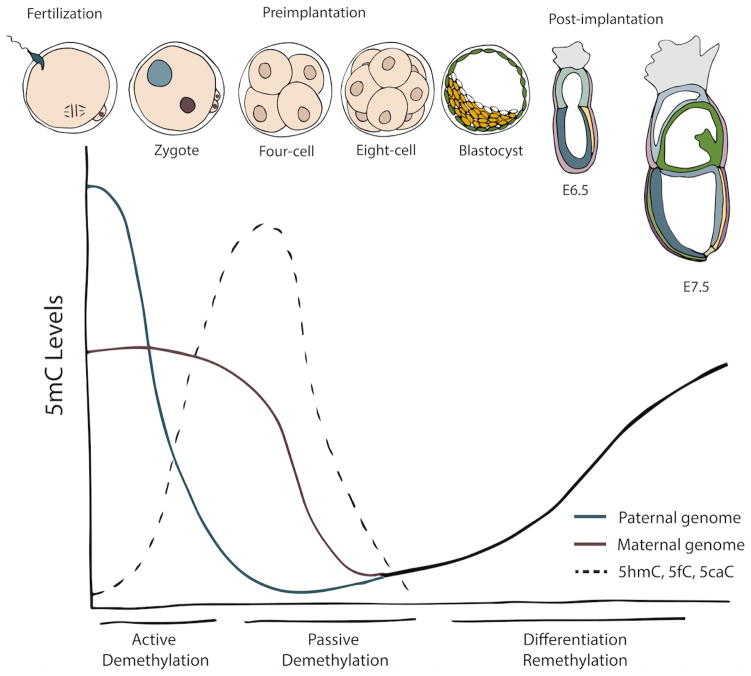

Figure 1. DNA demethylation in the zygote.

Distinct demethylation dynamics occur in the maternal (pink) and paternal (blue) pronuclei prior to fusion. At fertilization, the maternal haploid genome has approximately 40% methylation compared to nearly 90% methylation in the paternal haploid genome. Upon fertilization and continuing through pronuclear stage PN2, the paternal genome undergoes Tet3 dependent demethylation. PGC7, which preferentially binds to H3K9me2-rich chromatin, protects the maternal genome from Tet3 activity during PN stages. By PN5 stage, the bulk of paternal 5mC is gone and little change has occurred to maternal methylation. PPN= paternal pronucleus, MPN= maternal pronucleus.

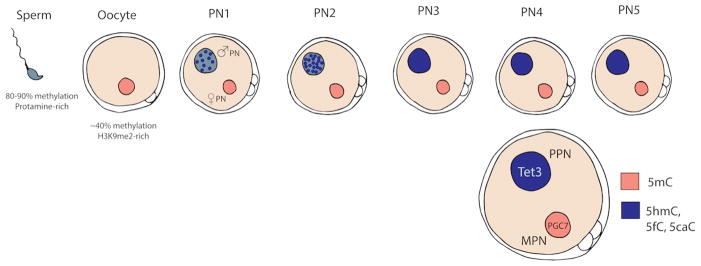

Figure 2. DNA methylation dynamics from fertilization through gastrulation.

The three main phases of methylation change are illustrated. During zygotic stages the paternal genome undergoes active demethylation (blue line). This active demethylation is evident by sharply increased levels of oxidative products (5mC to 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC) in the paternal pronucleus. Passive replication dependent demethylation (predominantly in the maternal pronucleus) occurs though exclusion of DNMTs from the nucleus during early preimplantation (red line). Lowest levels of methylation are reached between the morula to blastocyst stage, when methylation levels begin to rise. During blastocyst formation and gastrulation, the genome becomes re-methylated to levels consistent with somatic cells (black line).

Both sperm and oocytes contain parent of origin specific 5mC patterns. Therefore at the time of fertilization the two haploid genomes arrive with diverse epigenomic signatures. Both parental pronuclei undergo dramatic global demethylation, presumably to ensure similar epigenetic information at the two parental alleles of the majority of genes (imprinted loci being one exception) as well as to program the newly formed zygote to a totipotent state. The male haploid genome is heavily methylated in sperm, where between 80–90 percent of all CpG dinucleotides are methylated (Mayer et al. 2000, Oswald et al. 2000, Santos et al. 2002). Global DNA methylation levels in the maternal haploid genome are approximately half that of the sperm (Howlett & Reik 1991, Smallwood et al. 2011, Peat et al. 2014). Shortly after fertilization, the two parental genomes undergo distinct but equally dramatic waves of DNA demethylation. The paternal genome undergoes active, replication independent demethylation within the first several hours post-fertilization. In contrast, the maternal genome largely undergoes passive, cell division dependent diffusion of methylation, resulting in demethylation over the course of preimplantation development.

Active DNA demethylation during preimplantation development by Tet3 oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC)

Demethylation begins immediately in the newly formed embryo, prior to the first cell division. By the time the embryo reaches the morula stage, the genome is almost completely devoid of DNA methylation (Santos et al. 2002). Despite wide-spread global demethylation, a few regions of the genome are protected including imprinted loci and active retrotransposons like intracisternal A Particle (IAP) elements (Lane et al. 2003). The large scale demethylation begins with the rapid, active demethylation of the paternal haploid genome.

The differences between demethylation dynamics within the maternal and paternal pronuclei are thought to arise from their distinct architecture. The paternal genome is packed mostly around protamines, which are disassembled after fertilization and re-organized with histone containing nucleosomes (Braun 2001, Balhorn 2007). The maternal genome is largely assembled around H3K9me2-rich histones. These structural distinctions between the two haploid genomes at pronuclear stage 0 (PN0) is thought to greatly influence the timing of bulk genome-wide demethylation (Santos et al. 2005), the kinetics of which are different between the maternal and paternal pronuclei (Figure 1). Examination of global DNA methylation by immunofluorescence showed that the paternal pronucleus undergoes division independent demethylation (Santos et al. 2002). When the zygote reaches the PN3 stage (approximately 4 hours after fertilization), there is already a dramatic loss of 5mC observed in the paternal pronucleus but little change in the maternal pronucleus (Mayer et al. 2000, Oswald et al. 2000). By the time of the first cell division (24 hours after fertilization), there is no 5mC signal detected in the paternal PN, indicating near-complete loss of 5mC methylation. Even though the two parental genomes occupy the same nucleus after PN fusion, the differences in 5mC levels are apparent beyond the 4-cell stage (Santos et al. 2002).

Early studies of demethylation dynamics in mouse based on immunofluorescence conflicted somewhat with bisulfite DNA sequencing data sets which did not show as dramatic a loss of 5mC (Oswald et al. 2000). It was not until the realization that the 5mC oxidation product 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) is present in vivo that this discrepancy was resolved. Traditional bisulfite treatment does not distinguish between 5mC and 5hmC (Huang et al. 2010), while the antibodies used for immunofluorescence specifically (and only) detect 5mC. It has been subsequently shown that TET enzymes mediate the oxidation of 5mC to 5hmC (as well as 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC)) in vivo and that TET proteins are expressed and differentially localized during preimplantation development (Gu et al. 2011, He et al. 2011, Iqbal et al. 2011, Wossidlo et al. 2011). Specifically, TET3 primarily localizes to the paternal pronucleus (Figure 1) and is thought to be responsible for the observed rapid demethylation. Importantly, Gu et al showed that the loss of 5mC corresponds with a concomitant gain in 5hmC (Gu et al. 2011). In both pronuclei, 5mC is present until PN3, and by late PN3, there is a detectable decrease in 5mC and an increase in 5hmC (figure 1, (Gu et al. 2011, Iqbal et al. 2011, Wossidlo et al. 2011). It was also shown that Tet proteins convert 5mC to 5fC and 5caC as well, suggesting that Tet-mediated oxidation results in 3 oxidative forms for cytosine in vivo (Inoue 2011), ultimately resulting in replacement of the oxidized base with unmethylated cytosine by base excision repair or replication dependent diffusion. Additionally, oxidation of 5mC has been shown in others mammalian zygotes indicating a conserved mechanism of demethylation (Wossidlo et al. 2011).

Surprisingly, deletion of Tet3 activity results in retention of 5mC in the paternal pronucleus and inappropriate gene activation at many loci – but only mild global phenotype [reduced viability(Gu et al. 2011)]. Tet3 mediated hydrolysis of 5mC also occurs during reprogramming after SCNT cloning - Tet3 localizes to the pseudo-pronucleus in recombined zygotes. In SCNT embryos made with Tet3-null host oocytes, there is no 5hmC present in the pseudo-pronucleus, further indicating the role of Tet3 in active demethylation. (Wossidlo 2011, Gu 2011).

These recent studies offered the prevailing idea that demethylation during preimplantation development occurred via: (1) active DNA demethylation of the paternal pronuclei mediated by Tet3 and thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG)-mediated base excision repair [reviewed (Kohli & Zhang 2013)] and (2) passive, replication dependent dilution loss of methylation of the maternal genome due to lack of Dnmt1 in the nucleus (Howell et al. 2001).

However, recent work is shifting the hypotheses about the mechanisms responsible in vivo. Using whole genome approaches to assess cytosine methylation patterns it has been shown that Tet3-mediated demethylation is only partially responsible for paternal demethylation and that active demethylation also occurs in the maternal PN (Guo et al. 2014a, Shen et al. 2014). Furthermore, although Tet3 mediated oxidation is required for active demethylation, TDG-mediated base excision repair is not (Guo et al. 2014a). Additionally, it appears that there is conflicting evidence regarding the role that replication dependent demethylation plays in removing methylation from the paternal genome. By blocking replication of the paternal pronucleus, Shen et al. showed diminished demethylation in the paternal pronucleus even though Tet3 activity is present, indicating that replication is also involved in the demethylation of the paternal PN (Shen et al. 2014). Adding additional ambiguity is the fact that that Tet3-mediated demethylation is largely dispensable for successful development (Peat et al. 2014, Shen et al. 2014, Inoue et al. 2015).

Taken together the mechanisms that reprogram sperm and oocyte specific DNA methylation are not mutually exclusive as once predicted, and these recent stories indicate that there are likely unknown mechanisms also contributing to DNA methylation dynamics during preimplantation. With these advances, there are 3 main modes of DNA demethylation: (1) active Tet3-mediated oxidation (predominantly in the paternal pronucleus); (2) replication dependent dilution of Tet3-oxidative products, which plays a major role in demethylation the paternal pronucleus, and (3) replication dependent (Tet3 independent) dilution of 5mC (predominantly in the maternal pronucleus). As our technical abilities evolve it will be interesting to determine the interplay of these mechanisms within the same cells in vivo, define the specific loci at which each occurs, and identify if there are differing roles influencing cell fate decisions.

If Tet3 is present in the oocyte but only acts primarily on the paternal genome, there must be a protective mechanism to prevent conversion of maternal 5mC. One candidate for this maternal genome protection is PGC7/Stella, a DNA binding protein expressed during germ cell specification, gonad, and in oocytes (Saitou et al. 2002, Sato et al. 2002). PGC7 null embryos fail to complete preimplantation and there is a loss of 5mC in both pronuclei, indicating a protective role in the maternal pronucleus. Additionally, PGC7/Stella is targeted to differentially methylated regions (DMRs) of imprinted genes in the early embryo (Nakamura et al. 2007), supporting a functional role in blocking Tet3 mediated demethylation.

PGC7/Stella is able to protect the maternal pronucleus by binding to H3K9me2, which is a distinguishing feature of the maternal pronucleus. Loss of H3K9me2 by ectopic Jndm2a, a H3K9 methylation/dimethylation-specific demethylase, leads to loss of 5mC in both the maternal and parental pronuclei. PGC7/Stella also binds to H3K9me2 regions of the paternal pronucleus, including DMRs, which are not subject to protamine replacement. Tet3 is inhibited by PGC7/Stella thus offering protection from active demethylation (Nakamura et al. 2012).

Imprinted loci are protected from demethylation

While most of the genome undergoes global DNA demethylation, imprinted loci are protected and retain parent of origin differentially methylated regions (Branco 2008, Hirasawa 2008, Cirio 2008). It is clear that Dnmt1 is required for the maintenance of these imprinted sites (Bourc’his et al. 2001), even though it is largely excluded from the nucleus (Hirasawa 2008). Stella is also known to protect these loci, including some imprinted sites of the paternal genome. Additionally, Zfp57, a KRAB zinc finger protein, and Trim28 have also been shown to be required for integrity of ICRs in the early embryo. Trim28 interacts with Zfp57 to target it to specific imprinted sites resulting in recruitment of repressive complexes including NuRD, SETDB1, and DMNTs (Iyengar et al. 2011, Quenneville et al. 2011, Zuo et al. 2012). While loss of maternal Zfp57 can be rescued by paternal expression, loss of maternal Trim28 is lethal (Li et al. 2008, Messerschmidt et al. 2012), due in part to the variation in loss of imprinted expression (Messerschmidt et al. 2012).

Early DNA demethylation dynamics in other mammalian species

Preimplantation DNA demethylation dynamics are largely the same in mouse and human embryos. However, this is not the case in all mammals indicating distinct epigenetic reprogramming in different species. During the pronuclear stages and in the first cell divisions, human, mouse, and rat zygotes lose the majority of their paternal 5mC (Dean et al. 2001, Zaitseva et al. 2007). In contrast, both bovine and goat embryos retain an intermediate level of 5mC in the paternal pronuclei (Park et al. 2010, Wossidlo et al. 2010). Strikingly, sheep, pig, and rabbit embryos retain 5mC during the pronuclear stages and throughout preimplantation development (Beaujean et al. 2004, Jeong et al. 2007, Reis e Silva et al. 2012). In sheep, levels of 5mC drop during the 2-cell stage, but then increase at the 16-cell stage, and the ICM maintains levels of DNA methylation but the trophectoderm levels decrease dramatically (Young & Beaujean 2004).

These comparative studies illustrate the differences in timing and degree of 5mC loss during preimplantation among different mammalian species. These differences may be due in part to variation in zygotic genome activation, but they may also hint at differences in methylation reprogramming requirements needed to reach a totipotent state. These data also support the idea that active, Tet3-mediated demethylation in mouse is not required for normal preimplantation development (Peat et al. 2014, Shen et al. 2014).

Next-generation sequencing to assess global DNA methylation dynamics during preimplantation development

Next-generation sequencing, including reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) now allow assessment of global DNA methylation reprogramming with high resolution even from limited numbers of cells. Confirming earlier work, methylation across the genome is observed at relatively low levels in oocytes and early preimplantation stages, while sperm and post-implantation embryos have methylation similar to that of somatic cells (Smith et al. 2012, Guo et al. 2014a, Guo et al. 2014b, Peat et al. 2014). These newer technologies have allowed for refined assessment of methylation changes across the genome during precise developmental stages, examination of specific classes of DNA sequence elements and comparison of mouse and human preimplantation embryos.

DNA methylation dynamics in human preimplantation embryos

Two groups recently examined genome-wide DNA methylation changes in human oocyte, sperm, zygote, pre- and post-implantation stages, using reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) (Smith et al. 2012, Guo et al. 2014a). Similar to mouse, both groups found that human sperm is highly methylated (although less than mouse sperm) and human oocytes have intermediate levels of methylation. The post-fertilization demethylation kinetics are also similar in the human zygote (Smith et al. 2012). Guo et al. note that the greatest loss of DNA methylation occurred between the 1- to 2-cell stage in human embryos, rather than during PN stages (as is the case in the mouse). This could indicate that differences in the rate of active demethylation also correlates with the timing of zygotic genome activation, which occurs later in humans (Beaujean et al. 2004). Because bisulfite sequencing used in these studies did not distinguish between 5mC and the oxidative products of Tet-mediated demethylation, the distinct timing in mouse and human embryos may reflect a difference in the oxidation rates of 5mC or Tet activity between species. Paternal genome demethylation in human is similar to observations in mouse zygotes in that the majority of methylation is rapidly lost and only low levels of methylation remain during preimplantation. Levels of methylation in the maternal pronucleus are similar to mouse, but the genomic regions that are demethylated are divergent. Additionally, unlike in mouse, the majority of sperm and oocyte specific differentially methylated regions regain their full methylation following implantation (Smith et al. 2012, Guo et al. 2014a).

Comparison of genome wide methylation with single-cell RNA sequencing data (Yan et al. 2013) confirmed previously observed negative correlation between promoter methylation and gene expression and highlighted that this inverse relationship strengthens after the maternal to zygotic transition in human embryos (Smith et al. 2012, Guo et al. 2014b). Genes that had increased promoter methylation after the blastocyst stage showed a predicted decrease in expression in post-implantation stage embryos (Guo et al. 2014b). Also as expected, changes in DNA methylation during preimplantation influence the repression of transposable elements. SINE/variable number of tandem repeat/Alu elements (SVAs) expression increases after the 2-cell stage, when rapid demethylation occurs. This expression is maintained until the morula stage, when expression decreases – presumably as the genome is re-methylated – a trend which continues post-implantation (Smith et al. 2012, Guo et al. 2014b).

While many repeat elements undergo loss of DNA methylation and increased expression, the evolutionary age of the transposable element appears to influence the retention of methylation during preimplantation development. Evolutionarily younger elements, which are still capable of transposition are relatively resistant to demethylation while their evolutionarily older counterparts which have lost the ability to jump are readily demethylated along with coding genes. This might hint at the evolutionary origins of methylation/demethylation dynamics in mammalian preimplantation development (Wang et al. 2014).

Histone modifications during preimplantation

In addition to DNA methylation changes, chromatin organization and histone modifications play a critical role in establishing a totipotent embryo, as well as directing the first lineage decisions. Chromatin is a highly organized and dynamic nuclear structure containing DNA, histones and many other proteins. Nucleosomes, the basic building block of chromatin are comprised of two each of histone H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. It is well established that the N-terminal tails of these core histones are subject to post-translational modifications (PTMs) which play a fundamental role in influencing gene expression patterns among disparate cell types (Fischle et al. 2003). Histone PTMs include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination (and others), which occur at specific amino acid residues catalyzed by specific enzymes (Strahl & Allis 2000, Tan et al. 2011). Additional complexity arises in that methylation at lysines or arginines may exist in distinct forms: mono-, di-, or trimethyl for lysines and mono- or dimethyl on arginine residues (Kouzarides 2007). A general theme has emerged in which PTMs are catalyzed by opposite functional pairs of enzymes.

Many studies have revealed functional themes where histone PTMs correlate with gene expression patterns. For example, lysine acetylation is commonly considered to be an active mark which correlates with chromatin accessibility and active transcription, whereas histone lysine methylation can be either active or repressive depending on the particular lysine residue which is modified (Tsukada et al. 2006, Bernstein et al. 2007). Recent large scale efforts supported by the Roadmap Epigenomics Project are defining “chromatin states” in many diverse tissues – that is combinations of histone modifications, DNA methylation, and transcription factor binding that correlate with functional property of a particular locus (http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/publications/).

Histone modification during preimplantation embryo development

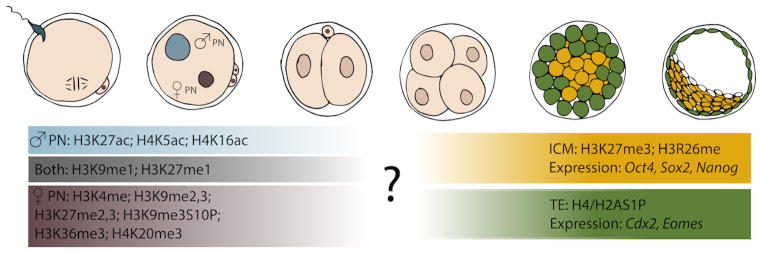

Studies of early embryonic development have shown that shortly after fertilization, many histone modifications are observed asymmetrically in the parental haploid genomes prior to pronuclear fusion (summarized in figure 3). For example in mice, H3K27ac, H4K5ac and H4K16ac are only detectable in the paternal PN of early zygotes (Adenot et al. 1997, Stein et al. 1997, Hayashi-Takanaka et al. 2011). Conversely, all forms of H3K4 methylation (me1, me2 and me3) are observed in maternal PN (Lepikhov & Walter 2004, Santenard et al. 2010), and H3K9me2 and me3 are also significantly higher in the maternal PN (Lepikhov & Walter 2004, Wongtawan et al. 2011, Beaujean 2014). H3K27me1 is present in both PNs, but H3K27me2 and -me3 occur extensively in the maternal PN (Erhardt et al., Santos et al. 2005, Santenard et al. 2010). Additionally, H3K9me3S10P, H3K36me3 and H4K20me3 are also found exclusively in the maternal PN at early post fertilization stages (Boskovic et al. 2012, Ribeiro-Mason et al. 2012, Beaujean 2014). Although the functional significance of these asymmetric PTMs remains largely unknown, it highlights the distinct reprogramming that is required for the paternal and maternal PN for proper embryonic genome activation and embryo development (Ribeiro-Mason et al. 2012, Beaujean 2014).

Figure 3. Differential histone modification during preimplantation development.

After fertilization the parental pronuclei are differentially enriched with many distinct histone modifications (left side – list of PTMs). Little data is available regarding the timing and mechanisms resulting after pronuclear fusion that result in largely homogenous PTMs during cleavage stages (indicated by question mark). By the time ICM and TE begin to differentiate, these cell lineages have acquired distinct epigenetic signatures and gene expression patterns (right side).

Histone PTMs also play key roles in remodeling of chromatin configuration and DNA methylation. In mice, increase of H3K79me by forced expression of DOT1L causes premature chromocenter formation and developmental arrest of 2-cell embryos (Ooga et al. 2013). Additionally, deletion of the methyltransferase Setdb1 in mouse embryonic stem cells leads to the reduction of H3K9me3 and an overall decrease of DNA methylation levels at specific loci (Leung et al. 2014). In porcine embryos, disturbed H3K4me3-H3K27me3 balance after knockdown of demethylase Kdm5b can cause increased expressions of Tet family members (Huang et al. 2015), which are found to be crucial for the interactions between histone modification and DNA methylation in mouse embryonic stem cells (Sui et al. 2012).

Functional studies of the roles of specific modifications are just beginning, using genetic strategies to add or remove specific enzymatic activities to embryos. For example in mice, hyperacetylation of histone H4 mediated by knockdown of HDAC1 causes developmental delay (Ma & Schultz 2008). Knockdown of either Ing2 (H3K4me3 methyltransferase activity) or RNF20 (histone H2B monoubiquitination) results in arrest at the morula stage (Zhou et al. 2015) (Ooga et al. 2015). Depletion of H4K20me1 by knockout of the PR-Set7 gene induces early embryonic lethality prior to the eight-cell stage (Oda et al. 2009), and our lab has shown critical roles of H3K36me3 during preimplantation development by knockdown of CTR9/PAF1 (Zhang et al. 2013b). Other recent examples include studies in mice showing that maternal-specific H3K9me3 is enriched at the Xist promoter region and prevents maternal Xist activation (Fukuda et al. 2014); increased H3K4me2 results in abnormal expression of eIF-4C/Oct4 and arrest at the two-cell stage (Shao et al. 2008); and that PRC1 binding to H3K27me3 plays an indispensable role in embryonic genome activation and developmental progression (Posfai et al. 2012). Although precise in the removal of specific gene function, these studies highlight the difficulty in assigning specific function to a particular modification or enzymatic activity since the phenotype is often developmental failure and misregulation of many genes. It is only very recently that next-generation technologies allow for very low input such that investigators can determine which loci across the genome are altered in these knockout/knockdown embryos (Brind’Amour et al. 2015).

Relevant to artificial reproductive technologies, histone modifications are sensitive to manipulations during preimplantation, potentially altering epigenomic patterns (Feil & Fraga 2011, Dupont et al. 2012). For example in the mouse, H3K4me3 is significantly lower in the in vitro fertilized embryos compared with in vivo fertilized embryos (Wu et al. 2012). Similarly lower levels of H3K27me3 are found in the inner cell mass of heated-sperm derived blastocysts when compared to untreated sperm derived blastocysts (Chao et al. 2012), and cryopreservation can alter H4K12ac patterns in both oocytes and zygotes (Suo et al. 2010). Despite these observations, it remains unclear if altered PTM levels persist in offspring or if surviving individuals contain appropriate epigenomic information – possibly correcting the epigenome during cell lineage differentiation at post-implantation stages.

Histone modifications in ICM and TE lineage specification

In mouse embryos, transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog are enriched in cells of the ICM and function to both promote pluripotency and resist differentiation. Conversely, in TE, transcription factors such as Cdx2 and Eomes become upregulated promoting differentiation. In contrast to the mouse, Oct4 and Cdx2 are co-expressed in the ICM and TE of bovine and porcine embryos, and the mechanisms of molecular differentiation remain largely unknown (Kirchhof et al. 2000).

This first lineage specification is critical for implantation and successful development. DNA methylation has been shown to be dispensable for growth and differentiation of the extraembryonic lineages (Sakaue et al. 2010), suggesting that appropriate histone modifications may provide key epigenetic information directing gene expression and lineage specification. Once the TE and ICM become distinct, they exhibit asymmetries in specific histone PTMs. For example in the mouse, H4- and H2AS1P are increased in the TE cells (Sarmento et al. 2004), while H3K27me3 is enriched in the ICM (Erhardt et al. 2003a). At the four-cell stage, blastomeres have different levels of methylated H3R26me and those cells with higher H3R26me are more likely to result in ICM cell fate. Overexpression of the H3R26 methyltransferase CARM1 results in increased expression Nanog and Sox2, suggesting that pluripotency factor expression is influenced by locus specific H3R26me (Torres-Padilla et al. 2007). Other examples include studies showing that repressive H3K9me3 at the Cdx2 promoter is important for maintaining pluripotency and loss of associated methyltransferase ESET in early embryos results in ICM failure (Yeap et al. 2009). However, in TE lineage, Suv39h methyltransferase mediates repressive H3K9me3 at ICM-specific gene promoters in the TE lineage (Alder et al. 2010, Rugg-Gunn et al. 2010). These studies highlight that even the same histone modification can be finely tuned by distinct enzymes to influence lineage specification in different cell populations.

There are ever growing observations of locus specific enrichment of histone modifications correlating with lineage decisions during preimplantation development. For example, H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 are enriched at promoters of genes exclusively expressed in ICM or TE in both murine and bovine embryos (Dahl et al. 2010, Herrmann et al. 2013). It was also recently shown that loss of repressive H3K27me3 participation at TE-specific genes is essential for TE lineage development and embryo implantation (Saha et al. 2013, Paul & Knott 2014). In addition to methylation of histone H3 residues, acetylation of histone H4 (H4K8ac and H4K12ac) has also been implicated in early lineage specification (VerMilyea et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2013a).

A handful of histone modifying proteins thought to be central to epigenetic programing during development have knock-out phenotypes only apparent after preimplantation. These include members of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (Eed, Ezh2 and Suz12) as well as the H3K9 methyltransferases G9a and Eset. It remains unclear if the timing of null phenotypes is due to functional redundancy with other genes, maternal loading of RNA/protein or if the modifications they perform are in fact not required until gastrulation (or later). There are a few histone modifying enzyme knock-out phenotypes in mice that do result in lethality during preimplantation some of which show lineage specific defects. Loss of the histone H3K9 demethylase Jmjd2C results in morula arrest and null embryos show reduced levels of ICM specific gene transcription suggesting a failure to maintain pluripotency (Wang et al. 2010). Similarly, null embryos of several members of the NuRD complex [Sin3A, Suds3, Arid4b (McDonel et al. 2009)] and PAF1 complex [Ctr9 and Rtf1 (Ding et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2013b)] do form blastocysts but show defects in ICM proliferation as a major cause of developmental lethality and failure. It is perhaps not so surprising that knockout of genes with distinct functions (such as Sin3A and Ctr9) result in similar defects in maintenance of ICM potency which is of the utmost importance for continued development and requires myriad proteins to accomplish.

Moving Forward

As described above, a wide array of covalent histone modifications are now recognized to occur in vivo and correlate with distinct transcriptional states and/or chromatin conformation. However, knowledge about the role of histone modifications during development is mostly limited to reports of changes in global patterns - apparent by immunofluorescence with antibodies directed against specific modifications (reviewed in (Beaujean 2014)). While these descriptive studies are an essential beginning, little is known about the functional importance of these modifications. In vivo analysis of the role of histone modifications at specific loci during early development is only just beginning, and the relative lack of functional data is due to several factors including: 1) limitations in our ability to efficiently generate maternal and zygote null embryos at the same time 2) limitations in our ability to assess histone modifications at specific loci from very small numbers of cells and 3) an inability to alter specific modifications at specific loci. Due to the combinatorial nature of the histone code and the difficulty in functionally preventing one particular modification at one locus in vivo it is currently not feasible to simply ask “what is the role of a specific histone modification at a specific genomic locus during development”. Fortunately, this type of epigenetic engineering has come to the fore and many groups are currently working to develop in vivo epigenetic targeting tools.

With greatly enhanced access to next-generation sequencing technologies there is ever growing opportunity to probe genome-wide methylation patterns at single base/nucleosome resolution in diverse cell populations, and improved techniques are pushing WGBS towards single cell sequencing. Additionally, multiple methods are now readily available for the discrimination of 5mC and 5hmC at a single base resolution. Combining DNA methylation analysis with ChIP-seq and RNA-seq during preimplantation development will allow for a comprehensive cataloguing of early epigenetic reprogramming dynamics. Cross-species comparison of these dynamics at specific loci and the capability to functionally test the importance of specific modifications will allow for deeper understanding of how epigenetic dynamics influence preimplantation development, the transition from gametes to totipotency, and the requirements of lineage differentiation.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This was supported in part by March of Dime Research Grant #6-FY11-367 and NIH 1R21HD078942-01 to JM.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review article.

References

- Adenot PG, Mercier Y, Renard JP, Thompson EM. Differential H4 acetylation of paternal and maternal chromatin precedes DNA replication and differential transcriptional activity in pronuclei of 1-cell mouse embryos. Development. 1997;124:4615–4625. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder O, Lavial F, Helness A, Brookes E, Pinho S, Chandrashekran A, Arnaud P, Pombo A, O’Neill L, Azuara V. Ring1B and Suv39h1 delineate distinct chromatin states at bivalent genes during early mouse lineage commitment. Development. 2010;137:2483–2492. doi: 10.1242/dev.048363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arand J, Spieler D, Karius T, Branco MR, Meilinger D, Meissner A, Jenuwein T, Xu G, Leonhardt H, Wolf V, Walter J. In vivo control of CpG and non-CpG DNA methylation by DNA methyltransferases. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balhorn R. The protamine family of sperm nuclear proteins. Genome Biol. 2007;8:227. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomei MS, Webber AL, Brunkow ME, Tilghman SM. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying the imprinting of the mouse H19 gene. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1663–1673. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.9.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujean N. Histone post-translational modifications in preimplantation mouse embryos and their role in nuclear architecture. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81:100–112. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujean N, Hartshorne G, Cavilla J, Taylor J, Gardner J, Wilmut I, Meehan R, Young L. Nonconservation of mammalian preimplantation methylation dynamics. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R266–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007;128:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggers JD, Bell JE, Benos DJ. Mammalian blastocyst: transport functions in a developing epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:C419–432. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.255.4.C419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgel J, Guibert S, Li Y, Chiba H, Schubeler D, Sasaki H, Forne T, Weber M. Targets and dynamics of promoter DNA methylation during early mouse development. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1093–1100. doi: 10.1038/ng.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boskovic A, Bender A, Gall L, Ziegler-Birling C, Beaujean N, Torres-Padilla ME. Analysis of active chromatin modifications in early mammalian embryos reveals uncoupling of H2A.Z acetylation and H3K36 trimethylation from embryonic genome activation. Epigenetics. 2012;7:747–757. doi: 10.4161/epi.20584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick M, Kim JK, Esteve PO, Clark A, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE. UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science. 2007;317:1760–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.1147939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourc’his D, Xu GL, Lin CS, Bollman B, Bestor TH. Dnmt3L and the establishment of maternal genomic imprints. Science. 2001;294:2536–2539. doi: 10.1126/science.1065848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun RE. Packaging paternal chromosomes with protamine. Nat Genet. 2001;28:10–12. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brind’Amour J, Liu S, Hudson M, Chen C, Karimi MM, Lorincz MC. An ultra-low-input native ChIP-seq protocol for genome-wide profiling of rare cell populations. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6033. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao SB, Chen L, Li JC, Ou XH, Huang XJ, Wen S, Sun QY, Gao GL. Defective histone H3K27 trimethylation modification in embryos derived from heated mouse sperm. Microsc Microanal. 2012:18476–482. doi: 10.1017/S1431927612000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl JA, Reiner AH, Klungland A, Wakayama T, Collas P. Histone H3 lysine 27 methylation asymmetry on developmentally-regulated promoters distinguish the first two lineages in mouse preimplantation embryos. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean W, Santos F, Stojkovic M, Zakhartchenko V, Walter J, Wolf E, Reik W. Conservation of methylation reprogramming in mammalian development: aberrant reprogramming in cloned embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13734–13738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241522698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Paszkowski-Rogacz M, Nitzsche A, Slabicki MM, Heninger AK, de Vries I, Kittler R, Junqueira M, Shevchenko A, Schulz H, Hubner N, Doss MX, Sachinidis A, Hescheler J, Iacone R, Anastassiadis K, Stewart AF, Pisabarro MT, Caldarelli A, Poser I, Theis M, Buchholz F. A genome-scale RNAi screen for Oct4 modulators defines a role of the Paf1 complex for embryonic stem cell identity. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont C, Cordier AG, Junien C, Mandon-Pepin B, Levy R, Chavatte-Palmer P. Maternal environment and the reproductive function of the offspring. Theriogenology. 2012;78:1405–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt S, Lyko F, Ainscough JF, Surani MA, Paro R. Polycomb-group proteins are involved in silencing processes caused by a transgenic element from the murine imprinted H19/Igf2 region in Drosophila. Dev Genes Evol. 2003a;213:336–344. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0331-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt S, Su IH, Schneider R, Barton S, Bannister AJ, Perez-Burgos L, Jenuwein T, Kouzarides T, Tarakhovsky A, Surani MA. Consequences of the depletion of zygotic and embryonic enhancer of zeste 2 during preimplantation mouse development. Development. 2003b;130:4235–4248. doi: 10.1242/dev.00625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Fraga MF. Epigenetics and the environment: emerging patterns and implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;13:97–109. doi: 10.1038/nrg3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Binary switches and modification cassettes in histone biology and beyond. Nature. 2003;425:475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature02017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TP, Sheth B, Fesenko I. Cell adhesion in the preimplantation mammalian embryo and its role in trophectoderm differentiation and blastocyst morphogenesis. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D1000–1007. doi: 10.2741/fleming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouse SD, Shen Y, Pellegrini M, Cole S, Meissner A, Van Neste L, Jaenisch R, Fan G. Promoter CpG methylation contributes to ES cell gene regulation in parallel with Oct4/Nanog, PcG complex, and histone H3 K4/K27 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Tomikawa J, Miura T, Hata K, Nakabayashi K, Eggan K, Akutsu H, Umezawa A. The role of maternal-specific H3K9me3 modification in establishing imprinted X-chromosome inactivation and embryogenesis in mice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5464. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet F, Talbot D, Leonhardt H, Jaenisch R. A short DNA methyltransferase isoform restores methylation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32725–32729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu TP, Guo F, Yang H, Wu HP, Xu GF, Liu W, Xie ZG, Shi L, He X, Jin SG, Iqbal K, Shi YG, Deng Z, Szabo PE, Pfeifer GP, Li J, Xu GL. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature. 2011;477:606–610. doi: 10.1038/nature10443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Li X, Liang D, Li T, Zhu P, Guo H, Wu X, Wen L, Gu TP, Hu B, Walsh CP, Li J, Tang F, Xu GL. Active and passive demethylation of male and female pronuclear DNA in the Mammalian zygote. Cell Stem Cell. 2014a;15:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Zhu P, Yan L, Li R, Hu B, Lian Y, Yan J, Ren X, Lin S, Li J, Jin X, Shi X, Liu P, Wang X, Wang W, Wei Y, Li X, Guo F, Wu X, Fan X, Yong J, Wen L, Xie SX, Tang F, Qiao J. The DNA methylation landscape of human early embryos. Nature. 2014b;511:606–610. doi: 10.1038/nature13544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Yamagata K, Wakayama T, Stasevich TJ, Kainuma T, Tsurimoto T, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, Kurumizaka H, Nozaki N, Kimura H. Tracking epigenetic histone modifications in single cells using Fab-based live endogenous modification labeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6475–6488. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, Ding J, Jia Y, Chen Z, Li L, Sun Y, Li X, Dai Q, Song CX, Zhang K, He C, Xu GL. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann D, Dahl JA, Lucas-Hahn A, Collas P, Niemann H. Histone modifications and mRNA expression in the inner cell mass and trophectoderm of bovine blastocysts. Epigenetics. 2013;8:281–289. doi: 10.4161/epi.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell CY, Bestor TH, Ding F, Latham KE, Mertineit C, Trasler JM, Chaillet JR. Genomic imprinting disrupted by a maternal effect mutation in the Dnmt1 gene. Cell. 2001;104:829–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett SK, Reik W. Methylation levels of maternal and paternal genomes during preimplantation development. Development. 1991;113:119–127. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zhang H, Wang X, Dobbs KB, Yao J, Qin G, Whitworth K, Walters EM, Prather RS, Zhao J. Impairment of Preimplantation Porcine Embryo Development by Histone Demethylase KDM5B Knockdown Through Disturbance of Bivalent H3K4me3-H3K27me3 Modifications. Biol Reprod. 2015 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.122762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Pastor WA, Shen Y, Tahiliani M, Liu DR, Rao A. The behaviour of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth RS, Gruenewald-Schneider U, Webb S, Kerr AR, James KD, Turner DJ, Smith C, Harrison DJ, Andrews R, Bird AP. Orphan CpG islands identify numerous conserved promoters in the mammalian genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Shen L, Matoba S, Zhang Y. Haploinsufficiency, but Not Defective Paternal 5mC Oxidation, Accounts for the Developmental Defects of Maternal Tet3 Knockouts. Cell Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K, Jin SG, Pfeifer GP, Szabo PE. Reprogramming of the paternal genome upon fertilization involves genome-wide oxidation of 5-methylcytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3642–3647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S, Ivanov AV, Jin VX, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Farnham PJ. Functional analysis of KAP1 genomic recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1833–1847. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01331-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong YS, Yeo S, Park JS, Koo DB, Chang WK, Lee KK, Kang YK. DNA methylation state is preserved in the sperm-derived pronucleus of the pig zygote. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:707–714. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072450yj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M, Okano M, Hata K, Sado T, Tsujimoto N, Li E, Sasaki H. Essential role for de novo DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a in paternal and maternal imprinting. Nature. 2004;429:900–903. doi: 10.1038/nature02633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Kaneda M, Hata K, Kumaki K, Hisano M, Kohara Y, Okano M, Li E, Nozaki M, Sasaki H. Role of the Dnmt3 family in de novo methylation of imprinted and repetitive sequences during male germ cell development in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2272–2280. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder GM, Winterhager E. Intercellular communication in preimplantation development: the role of gap junctions. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D731–736. doi: 10.2741/kidder. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhof N, Carnwath JW, Lemme E, Anastassiadis K, Scholer H, Niemann H. Expression pattern of Oct-4 in preimplantation embryos of different species. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1698–1705. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishikawa S, Murata T, Ugai H, Yamazaki T, Yokoyama KK. Control elements of Dnmt1 gene are regulated in cell-cycle dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res Suppl. 2003:307–308. doi: 10.1093/nass/3.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli RM, Zhang Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature. 2013;502:472–479. doi: 10.1038/nature12750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N, Dean W, Erhardt S, Hajkova P, Surani A, Walter J, Reik W. Resistance of IAPs to methylation reprogramming may provide a mechanism for epigenetic inheritance in the mouse. Genesis. 2003;35:88–93. doi: 10.1002/gene.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham KE, Solter D, Schultz RM. Activation of a two-cell stage-specific gene following transfer of heterologous nuclei into enucleated mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 1991;30:182–186. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt H, Page AW, Weier HU, Bestor TH. A targeting sequence directs DNA methyltransferase to sites of DNA replication in mammalian nuclei. Cell. 1992;71:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90561-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepikhov K, Walter J. Differential dynamics of histone H3 methylation at positions K4 and K9 in the mouse zygote. BMC Dev Biol. 2004;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung D, Du T, Wagner U, Xie W, Lee AY, Goyal P, Li Y, Szulwach KE, Jin P, Lorincz MC, Ren B. Regulation of DNA methylation turnover at LTR retrotransposons and imprinted loci by the histone methyltransferase Setdb1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6690–6695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322273111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Ito M, Zhou F, Youngson N, Zuo X, Leder P, Ferguson-Smith AC. A maternal-zygotic effect gene, Zfp57, maintains both maternal and paternal imprints. Dev Cell. 2008;15:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P, Schultz RM. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) regulates histone acetylation, development, and gene expression in preimplantation mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 2008;319:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, DePamphilis ML. Requirements for DNA transcription and replication at the beginning of mouse development. J Cell Biochem. 1994;55:59–68. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240550107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunakea AK, Nagarajan RP, Bilenky M, Ballinger TJ, D’Souza C, Fouse SD, Johnson BE, Hong C, Nielsen C, Zhao Y, Turecki G, Delaney A, Varhol R, Thiessen N, Shchors K, Heine VM, Rowitch DH, Xing X, Fiore C, Schillebeeckx M, Jones SJ, Haussler D, Marra MA, Hirst M, Wang T, Costello JF. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature. 2010;466:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature09165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer W, Niveleau A, Walter J, Fundele R, Haaf T. Demethylation of the zygotic paternal genome. Nature. 2000;403:501–502. doi: 10.1038/35000656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonel P, Costello I, Hendrich B. Keeping things quiet: roles of NuRD and Sin3 co-repressor complexes during mammalian development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertineit C, Yoder JA, Taketo T, Laird DW, Trasler JM, Bestor TH. Sex-specific exons control DNA methyltransferase in mammalian germ cells. Development. 1998;125:889–897. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt DM, de Vries W, Ito M, Solter D, Ferguson-Smith A, Knowles BB. Trim28 is required for epigenetic stability during mouse oocyte to embryo transition. Science. 2012;335:1499–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1216154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Arai Y, Umehara H, Masuhara M, Kimura T, Taniguchi H, Sekimoto T, Ikawa M, Yoneda Y, Okabe M, Tanaka S, Shiota K, Nakano T. PGC7/Stella protects against DNA demethylation in early embryogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:64–71. doi: 10.1038/ncb1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Liu YJ, Nakashima H, Umehara H, Inoue K, Matoba S, Tachibana M, Ogura A, Shinkai Y, Nakano T. PGC7 binds histone H3K9me2 to protect against conversion of 5mC to 5hmC in early embryos. Nature. 2012;486:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature11093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J, Gardner RL. Heterogeneous differentiation of external cells in individual isolated early mouse inner cell masses in culture. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984;80:225–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothias JY, Majumder S, Kaneko KJ, DePamphilis ML. Regulation of gene expression at the beginning of mammalian development. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22077–22080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda H, Okamoto I, Murphy N, Chu J, Price SM, Shen MM, Torres-Padilla ME, Heard E, Reinberg D. Monomethylation of histone H4-lysine 20 is involved in chromosome structure and stability and is essential for mouse development. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2278–2295. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01768-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 1999;99:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooga M, Suzuki MG, Aoki F. Involvement of DOT1L in the remodeling of heterochromatin configuration during early preimplantation development in mice. Biol Reprod. 2013;89:145. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.113258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooga M, Suzuki MG, Aoki F. Involvement of histone H2B monoubiquitination in the regulation of mouse preimplantation development. The Journal of reproduction and development. 2015 doi: 10.1262/jrd.2014-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald J, Engemann S, Lane N, Mayer W, Olek A, Fundele R, Dean W, Reik W, Walter J. Active demethylation of the paternal genome in the mouse zygote. Curr Biol. 2000;10:475–478. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Lee D, Cho S, Shin ST, Kang YK. Active loss of DNA methylation in two-cell stage goat embryos. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:1323–1328. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.092973jp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Knott JG. Epigenetic control of cell fate in mouse blastocysts: the role of covalent histone modifications and chromatin remodeling. Mol Reprod Dev. 2014;81:171–182. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peat JR, Dean W, Clark SJ, Krueger F, Smallwood SA, Ficz G, Kim JK, Marioni JC, Hore TA, Reik W. Genome-wide bisulfite sequencing in zygotes identifies demethylation targets and maps the contribution of TET3 oxidation. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1990–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen RA, Wu K, Balakier H. Origin of the inner cell mass in mouse embryos: cell lineage analysis by microinjection. Dev Biol. 1986;117:581–595. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce M, Scholer HR. Oct-4: gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells. 2001;19:271–278. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posfai E, Kunzmann R, Brochard V, Salvaing J, Cabuy E, Roloff TC, Liu Z, Tardat M, van Lohuizen M, Vidal M, Beaujean N, Peters AH. Polycomb function during oogenesis is required for mouse embryonic development. Genes Dev. 2012;26:920–932. doi: 10.1101/gad.188094.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quenneville S, Verde G, Corsinotti A, Kapopoulou A, Jakobsson J, Offner S, Baglivo I, Pedone PV, Grimaldi G, Riccio A, Trono D. In embryonic stem cells, ZFP57/KAP1 recognize a methylated hexanucleotide to affect chromatin and DNA methylation of imprinting control regions. Mol Cell. 2011;44:361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis e Silva AR, Bruno C, Fleurot R, Daniel N, Archilla C, Peynot N, Lucci CM, Beaujean N, Duranthon V. Alteration of DNA demethylation dynamics by in vitro culture conditions in rabbit pre-implantation embryos. Epigenetics. 2012;7:440–446. doi: 10.4161/epi.19563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Mason K, Boulesteix C, Brochard V, Aguirre-Lavin T, Salvaing J, Fleurot R, Adenot P, Maalouf WE, Beaujean N. Nuclear dynamics of histone H3 trimethylated on lysine 9 and/or phosphorylated on serine 10 in mouse cloned embryos as new markers of reprogramming? Cell Reprogram. 2012;14:283–294. doi: 10.1089/cell.2011.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau J, Tanigawa G, Szyf M. The mouse DNA methyltransferase 5′-region. A unique housekeeping gene promoter. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:7368–7377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg-Gunn PJ, Cox BJ, Ralston A, Rossant J. Distinct histone modifications in stem cell lines and tissue lineages from the early mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10783–10790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914507107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha B, Home P, Ray S, Larson M, Paul A, Rajendran G, Behr B, Paul S. EED and KDM6B coordinate the first mammalian cell lineage commitment to ensure embryo implantation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2691–2705. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00069-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou M, Barton SC, Surani MA. A molecular programme for the specification of germ cell fate in mice. Nature. 2002;418:293–300. doi: 10.1038/nature00927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaue M, Ohta H, Kumaki Y, Oda M, Sakaide Y, Matsuoka C, Yamagiwa A, Niwa H, Wakayama T, Okano M. DNA methylation is dispensable for the growth and survival of the extraembryonic lineages. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1452–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santenard A, Ziegler-Birling C, Koch M, Tora L, Bannister AJ, Torres-Padilla ME. Heterochromatin formation in the mouse embryo requires critical residues of the histone variant H3.3. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:853–862. doi: 10.1038/ncb2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F, Hendrich B, Reik W, Dean W. Dynamic reprogramming of DNA methylation in the early mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2002;241:172–182. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos F, Peters AH, Otte AP, Reik W, Dean W. Dynamic chromatin modifications characterise the first cell cycle in mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 2005;280:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento OF, Digilio LC, Wang Y, Perlin J, Herr JC, Allis CD, Coonrod SA. Dynamic alterations of specific histone modifications during early murine development. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4449–4459. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Kimura T, Kurokawa K, Fujita Y, Abe K, Masuhara M, Yasunaga T, Ryo A, Yamamoto M, Nakano T. Identification of PGC7, a new gene expressed specifically in preimplantation embryos and germ cells. Mech Dev. 2002;113:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1412–1417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510310103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrode N, Xenopoulos P, Piliszek A, Frankenberg S, Plusa B, Hadjantonakis AK. Anatomy of a blastocyst: cell behaviors driving cell fate choice and morphogenesis in the early mouse embryo. Genesis. 2013;51:219–233. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz GA, Hahnel A, Arcellana-Panlilio M, Wang L, Goubau S, Watson A, Harvey M. Expression of IGF ligand and receptor genes during preimplantation mammalian development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1993;35:414–420. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080350416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz RM. The molecular foundations of the maternal to zygotic transition in the preimplantation embryo. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:323–331. doi: 10.1093/humupd/8.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao GB, Ding HM, Gong AH. Role of histone methylation in zygotic genome activation in the preimplantation mouse embryo. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2008;44:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s11626-008-9082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Inoue A, He J, Liu Y, Lu F, Zhang Y. Tet3 and DNA replication mediate demethylation of both the maternal and paternal genomes in mouse zygotes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutels F, Tjon G, Ludwig T, Barlow DP. Imprinted silencing of Slc22a2 and Slc22a3 does not need transcriptional overlap between Igf2r and Air. EMBO J. 2003;22:3696–3704. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood SA, Tomizawa S, Krueger F, Ruf N, Carli N, Segonds-Pichon A, Sato S, Hata K, Andrews SR, Kelsey G. Dynamic CpG island methylation landscape in oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Nat Genet. 2011;43:811–814. doi: 10.1038/ng.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ZD, Chan MM, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Gnirke A, Regev A, Meissner A. A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature. 2012;484:339–344. doi: 10.1038/nature10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein P, Worrad DM, Belyaev ND, Turner BM, Schultz RM. Stage-dependent redistributions of acetylated histones in nuclei of the early preimplantation mouse embryo. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;47:421–429. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199708)47:4<421::AID-MRD8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, Price C, Li Z, Chen J. Crosstalk Between DNA and Histones: Tet’s New Role in Embryonic Stem Cells. Curr Genomics. 2012;13:603–608. doi: 10.2174/138920212803759730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo L, Meng Q, Pei Y, Fu X, Wang Y, Bunch TD, Zhu S. Effect of cryopreservation on acetylation patterns of lysine 12 of histone H4 (acH4K12) in mouse oocytes and zygotes. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:735–741. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9469-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada S, Paulsen M, Tevendale M, Tsai CE, Kelsey G, Cattanach BM, Ferguson-Smith AC. Epigenetic analysis of the Dlk1-Gtl2 imprinted domain on mouse chromosome 12: implications for imprinting control from comparison with Igf2-H19. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:77–86. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Luo H, Lee S, Jin F, Yang JS, Montellier E, Buchou T, Cheng Z, Rousseaux S, Rajagopal N, Lu Z, Ye Z, Zhu Q, Wysocka J, Ye Y, Khochbin S, Ren B, Zhao Y. Identification of 67 histone marks and histone lysine crotonylation as a new type of histone modification. Cell. 2011;146:1016–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Hennebold JD, Macfarlane J, Adashi EY. A mammalian oocyte-specific linker histone gene H1oo: homology with the genes for the oocyte-specific cleavage stage histone (cs-H1) of sea urchin and the B4/H1M histone of the frog. Development. 2001;128:655–664. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.5.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Padilla ME, Parfitt DE, Kouzarides T, Zernicka-Goetz M. Histone arginine methylation regulates pluripotency in the early mouse embryo. Nature. 2007;445:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature05458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VerMilyea MD, O’Neill LP, Turner BM. Transcription-independent heritability of induced histone modifications in the mouse preimplantation embryo. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xie G, Singh M, Ghanbarian AT, Rasko T, Szvetnik A, Cai H, Besser D, Prigione A, Fuchs NV, Schumann GG, Chen W, Lorincz MC, Ivics Z, Hurst LD, Izsvak Z. Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus-driven transcription defines naive-like stem cells. Nature. 2014;516:405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature13804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Kou Z, Han Z, Chen DY, Sun QY, Gao S. The histone demethylase JMJD2C is stage-specifically expressed in preimplantation mouse embryos and is required for embryonic development. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:105–111. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.078055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe D, Suetake I, Tada T, Tajima S. Stage- and cell-specific expression of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b during embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 2002;118:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AJ, Damsky CH, Kidder GM. Differentiation of an epithelium: factors affecting the polarized distribution of Na+,K(+)-ATPase in mouse trophectoderm. Dev Biol. 1990;141:104–114. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90105-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wongtawan T, Taylor JE, Lawson KA, Wilmut I, Pennings S. Histone H4K20me3 and HP1alpha are late heterochromatin markers in development, but present in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1878–1890. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wossidlo M, Arand J, Sebastiano V, Lepikhov K, Boiani M, Reinhardt R, Scholer H, Walter J. Dynamic link of DNA demethylation, DNA strand breaks and repair in mouse zygotes. EMBO J. 2010;29:1877–1888. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wossidlo M, Nakamura T, Lepikhov K, Marques CJ, Zakhartchenko V, Boiani M, Arand J, Nakano T, Reik W, Walter J. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian zygote is linked with epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2011;2:241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FR, Liu Y, Shang MB, Yang XX, Ding B, Gao JG, Wang R, Li WY. Differences in H3K4 trimethylation in in vivo and in vitro fertilization mouse preimplantation embryos. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:1099–1108. doi: 10.4238/2012.April.27.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka Y, Ralston A, Stephenson RO, Rossant J. Cell and molecular regulation of the mouse blastocyst. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2301–2314. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Yang M, Guo H, Yang L, Wu J, Li R, Liu P, Lian Y, Zheng X, Yan J, Huang J, Li M, Wu X, Wen L, Lao K, Li R, Qiao J, Tang F. Single-cell RNA-Seq profiling of human preimplantation embryos and embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeap LS, Hayashi K, Surani MA. ERG-associated protein with SET domain (ESET)-Oct4 interaction regulates pluripotency and represses the trophectoderm lineage. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2009;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LE, Beaujean N. DNA methylation in the preimplantation embryo: the differing stories of the mouse and sheep. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;82–83:61–78. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva I, Zaitsev S, Alenina N, Bader M, Krivokharchenko A. Dynamics of DNA-demethylation in early mouse and rat embryos developed in vivo and in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:1255–1261. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Dai X, Wallingford MC, Mager J. Depletion of Suds3 reveals an essential role in early lineage specification. Dev Biol. 2013a;373:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Haversat JM, Mager J. CTR9/PAF1c regulates molecular lineage identity, histone H3K36 trimethylation and genomic imprinting during preimplantation development. Dev Biol. 2013b;383:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Wang P, Zhang J, Heng BC, Tong GQ. ING2 (inhibitor of growth protein-2) plays a crucial role in preimplantation development. Zygote. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0967199414000768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X, Sheng J, Lau HT, McDonald CM, Andrade M, Cullen DE, Bell FT, Iacovino M, Kyba M, Xu G, Li X. Zinc finger protein ZFP57 requires its co-factor to recruit DNA methyltransferases and maintains DNA methylation imprint in embryonic stem cells via its transcriptional repression domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:2107–2118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]