Abstract

Lupus develops when genetically predisposed people encounter environmental agents such as UV light, silica, infections and cigarette smoke that cause oxidative stress, but how oxidative damage modifies the immune system to cause lupus flares is unknown. We previously showed that oxidizing agents decreased ERK pathway signaling in human T cells, decreased DNA methyltransferase 1 and caused demethylation and overexpression of genes similar to those from patients with active lupus. The current study tested whether oxidant-treated T cells can induce lupus in mice. We adoptively transferred CD4+ T cells treated in vitro with oxidants hydrogen peroxide or nitric oxide or the demethylating agent 5-azacytidine into syngeneic mice and studied the development and severity of lupus in the recipients. Disease severity was assessed by measuring anti-dsDNA antibodies, proteinuria, hematuria and by histopathology of kidney tissues. The effect of the oxidants on expression of CD40L, CD70, KirL1 and DNMT1 genes and CD40L protein in the treated CD4+ T cells was assessed by Q-RT-PCR and flow cytometry. H2O2 and ONOO− decreased Dnmt1 expression in CD4+ T cells and caused the upregulation of genes known to be suppressed by DNA methylation in patients with lupus and animal models of SLE. Adoptive transfer of oxidant-treated CD4+ T cells into syngeneic recipients resulted in the induction of anti-dsDNA antibody and glomerulonephritis. The results show that oxidative stress may contribute to lupus disease by inhibiting ERK pathway signaling in T cells leading to DNA demethylation, upregulation of immune genes and autoreactivity.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), CD70, CD40L, KirL1

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic relapsing autoimmune disease that primarily affects women. SLE develops and flares when genetically predisposed people encounter certain environmental agents. The genes predisposing to lupus are being identified, and epidemiologic evidence indicates that environmental agents which cause oxidative stress, such as infections, sun exposure, silica and smoking, are associated with lupus onset and flares [1]. However, how environmentally induced reactive oxygen species interact with the immune system to trigger lupus flares remains unclear.

Our group reported that CD4+ T cells epigenetically altered with DNA methylation inhibitors like 5-azacytidine (5-azaC), procainamide (Pca) or hydralazine (Hyd) cause lupus-like autoimmunity in animal models [2], and that similar epigenetically modified T cells are found in lupus patients during disease flares [1]. We traced the cause of the epigenetic defect to PKCδ inactivation, which prevents upregulation of DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1) during mitosis to copy methylation patterns [3]. Others reported that serum proteins are nitrated in patients with active lupus, caused by superoxide (O−2) combining with nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a highly reactive molecule that nitrates proteins and other molecules [4]. Our group subsequently found that PKCδ is similarly nitrated in T cells from patients with active lupus, and that nitrated PKCδ is unable to transmit signals that upregulate Dnmt1 to copy DNA methylation patterns in dividing T cells, causing demethylation and overexpression of genes normally suppressed by DNA methylation [5]. We extended these observations by demonstrating that treating human CD4+ T cells with the oxidizing agents H2O2 or ONOO− inhibits PKCδ activation, thereby decreasing ERK pathway signaling, decreasing Dnmt1 levels and causing demethylation and overexpression of CD70 and Kir genes similar to T cells from patients with active lupus [6]. However, whether the epigenetically modified T cells are sufficient to cause lupus-like autoimmunity was unknown.

We have now tested if female murine CD4+ T cells treated with H2O2 or ONOO− also overexpress methylation sensitive genes, and if the treated cells cause lupus-like autoimmunity in mice. The results demonstrate that the oxidized T cells overexpress the X-linked gene CD40L, one copy of which is silenced by DNA methylation in female human and mouse T cells [7, 8], and Kir genes, normally expressed by NK cells but silenced by DNA methylation in human and mouse T cells [9]. The results also demonstrate that adoptive transfer of the treated cells into syngeneic recipients causes anti-DNA antibodies and an immune complex glomerulonephritis, similar to T cells treated 5-azaC, Pca or Hyd. Together these studies support the contention that environmentally-induced oxidative stress may trigger lupus flares by epigenetically altering T cells through effects on T cell signaling and Dnmt1 expression.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Drugs and reagents

5-azaC and H2O2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and ONOO− from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA).

2.2. Mice

Female SJL mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, housed in filter-protected cages, and provided with standard irradiated rodent diet 5053 (Lab Diet; PMI Nutrition International) and water ad libitum. Urinary protein and hemoglobin were measured using Chemstrip 7 dipsticks (Roche, Madison, WI). The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen–free facility by the Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine at the University of Michigan in accordance with the National Institutes of Health and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International Guidelines. All procedures were approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.3. T cell isolation, culture, treatment and injection

Splenocytes, thymocytes and lymph node cells were isolated from female SJL mice, pooled and stimulated in vitro with 5 μg/ml concanavalin A in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES,1000 U Penicillin/1mg streptomycin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 18-24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2/balanced air incubator. CD4+ T cells were then isolated using magnetic beads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA), and treated with 5 μM 5-azaC, 20 μM H2O2 or 20 μM ONOO− for 3 days in 6 well plates as previously described [2, 6, 10]. The cells were then washed and 5×106 viable cells injected into the tail vein of each female SJL recipients, beginning when the mice were 12 weeks of age and continuing every 2 weeks for a total of 7 injections. Cells analyzed for gene expression by PCR were additionally treated with 50ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 500 ng/ml ionomycin during their final 6 hours of culture. Blood and urine samples were obtained every other week. Two weeks after the last injection the mice were sacrificed, CD4+ T cells isolated for further study and kidneys removed for histologic analysis.

2.4. Flow cytometric analysis

Spleen cells were washed twice in Standard Buffer (PBS containing 1% horse serum and 1 mg/ml sodium azide) at 4°C. All incubations were performed on ice. Non-specific binding was blocked by incubating the cells 1 hr on ice in Standard Buffer containing 10% horse serum. The cells were then stained in the dark for 1 hr with PE-Cy5-rat anti-mouse CD4 (BD Pharmingen, Fullerton, CA) together with PE-hamster anti-mouse CD154 (CD40L) or matching IgG controls washed, then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and stored in the dark at 4°C. The cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as previously described [8].

2.5. RT-PCR

Total RNA and DNA were simultaneously isolated from bead-purified CD4+ T cells using a Qiagen RNAEasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Products, Wilmington, DE). One microgram of total RNA per sample was used to synthesize cDNA using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit and anchored oligo(dT)18 primers (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers for murine CD70, CD40L, KirL1, β-actin, and Dnmt1 were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and used in RT-PCR to measure mRNA gene expression as previous described [8].

2.6. Anti-DNA antibody ELISA

Mouse IgG anti-dsDNA antibodies were measured by ELISA as previously described [11]. Briefly, Costar (Corning, NY) 96 well flat bottom microtiter plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 10 μg/ml dsDNA in PBS, pH 7.2. Various dilutions of mouse sera or murine monoclonal IgG anti-dsDNA antibody ( Millipore, Billerica, MA) standard were added in PBS and incubated overnight at 4° C. Bound anti-dsDNA antibodies were detected using HRP-goat anti-mouse IgG-Fc-specific (Bethyl Labs, Montgomery, TX) antibodies and One Step Ultra TMB substrate (Thermo, Rockford, IL) and measured at 450nm [11].

2.7. Histologic analyses

Kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed and paraffin embedded. Five micron sections were deparaffinized, hydrated and rinsed for 5 min. in tap water and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or treated with citrate antigen retrieval buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vector laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by treating the tissue sections with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min at ambient temperature followed by a 5 minute wash in PBS. The tissues were then incubated with 2.5% horse serum/PBS for 20 min. and IgG detected using the IMPRESS Detection system and NOVA-Red© substrate (Vector Laboratories, Inc). The tissue was counter stained with hematoxylin according to the manufacturer's instructions, mounted with Immu-Mount (Thermo Fisher) and coverslipped.

2.8. Statistical analyses

The significance of differences between means was assessed using Student's t-Test or ANOVA. The linear mixed model was used to assess the effect of different treatments on antibody production relative to injections of Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) over time, and the Chi square test to assess differences in proteinuria between groups at 12 weeks.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Murine CD4+ T cells treated with oxidizing agents overexpress methylation sensitive genes

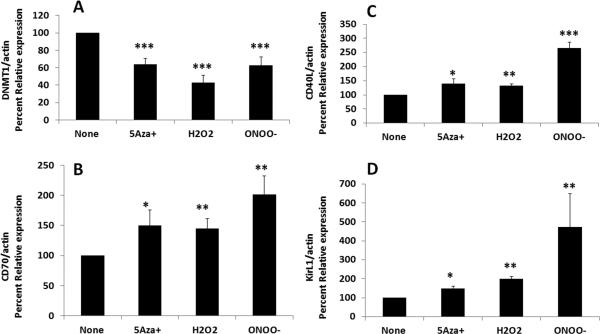

We previously reported that inhibiting the replication of human CD4+ T cell DNA methylation patterns with the Dnmt inhibitor 5-azaC causes demethylation and overexpression of genes including CD40L on the female inactive X chromosome in humans and mice [8, 12] as well as the human KIR gene family, normally expressed by NK cells but not T cells [9, 13]. Initial studies compared the effects of H2O2 and ONOO− to 5-azaC on murine CD4+ T cell CD40L and Kir expression. We recently reported that experimentally demethylated CD4+ T cells cause a more severe form of autoimmunity in lupus prone SJL mice relative to C57BL6 mice, with higher titer anti-DNA antibodies and more severe kidney disease [8]. Therefore SJL mice were used for these studies. The spleen, thymus and axillary lymph nodes were removed from female SJL mice, then mononuclear cells were isolated and stimulated with Con-A in vitro. 18-24 hours later CD4+ T cells were purified and cultured with 5 μM 5-azaC, 20 μM H2O2 or 20 μM ONOO− for 72 hours using protocols previously described by our group [6]. Live cells were isolated on a ficoll gradient followed by lysis, RNA isolation and cDNA preparation. CD40L and KirL1 transcripts were measured relative to β-actin by RT-PCR. CD40L was selected because this gene is encoded on the second, inactive X chromosome in females, and the increase in expression caused by DNA methylation inhibitors is due to demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive X in humans and mice [11, 12]. KirL1 was chosen because this gene is expressed by NK cells but not T cells, and is silenced in T cells primarily by DNA methylation [13]. Figure 1 shows that CD4+ T cells treated with 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO− had significantly decreased Dnmt1 gene expression relative to untreated controls (Fig 1A) and over-expressed CD70 (Fig. 1B), CD40L (Fig. 1C) and KirL1 (Fig. 1D) mRNA relative to untreated T cells. These results are similar to our earlier reports using other DNA methylation inhibitors [8, 9].

Figure 1. 5-azaC, H2O2 and ONOO− decrease Dnmt1 gene expression and increase the expression of methylation sensitive genes CD40L, CD70 and KirL1 mRNA in CD4+ T cells.

The spleen, thymus and axillary lymph nodes were removed from female SJL mice, then mononuclear cells were isolated and stimulated with Con-A in vitro. 18-24 hours later CD4+ T cells were purified and treated with 5 μM 5-azaC, 20 μM H2O2 or 20 μM ONOO− using previously described protocols [6]. 72 hours later the T cells were treated with PMA and ionomycin for their final 6 h culture then lysed and Dnmt1 (A), CD70 (B), CD40L (C) and KirL1 (D) transcripts measured relative to β-actin by RT-PCR. Results are expressed as percent of the untreated control (100%) and represent the mean +/− SEM of 3 experiments combined (*P≤0.05; **P<0.01; *** P≤ 0.001 by Student's t-Test.)

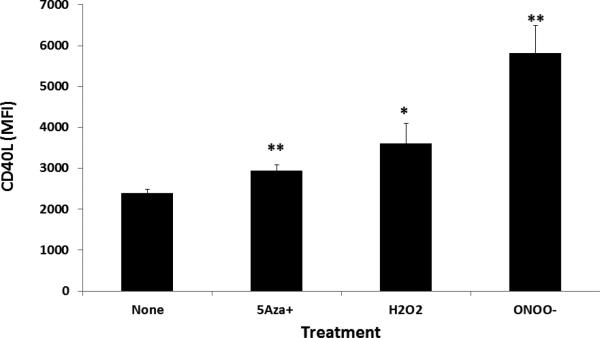

The effects of 5-azaC, H2O2 and ONOO− on CD40L expression were confirmed at the protein level. Splenocytes from female SJL mice were stimulated with Con-A then treated with H2O2 or ONOO− as in Figure 1. Seventy-two hours later the cells were washed, stained with fluorochrome conjugated antibodies to CD4 and CD40L then analyzed by flow cytometry. Figure 2 shows that 5-azaC treatment increased CD40L expression as expected (p=0.004). Both H2O2 and ONOO− significantly increase CD40L expression on CD4+ T cells compared to the untreated control (p = 0.049, p=0.004 respectively). ONOO− treatment induced more CD40L expression than 5-azaC (mean MFI 5819 +/− 675 vs 2942 +/− 147, p=0.01, n=5) but the difference between ONOO− and H2O2 was not statistically significant (mean MFI 3615 +/− 475, p=0.06) (p=0.004.

Figure 2. 5-azaC, H2O2 and ONOO− increase CD40L protein expression in CD4+ T cells.

Splenocytes from female SJL mice were stimulated with Con-A then treated with H2O2 or ONOO− as in Figure 1. 72 hours later the cells were washed, stained with fluorochrome conjugated antibodies to CD4 and CD40L then analyzed by flow cytometry. * P=0.049, **P=0.004 by paired t-Test). Results are expressed as the mean±SEM (n=5 mice) and are from one of two independent experiments.

3.2. CD4+ T cells treated with oxidizing agents cause lupus-like autoimmunity in syngeneic mice

Functional significance of the changes in T cell gene expression caused by the oxidizers was tested using the adoptive transfer model previously described by our group for T cells treated procainamide and hydralazine, which inhibit T cell DNA methylation and cause a lupus-like disease in genetically predisposed people [14]. Splenocytes, thymocytes and lymph node cells were isolated from female SJL mice, stimulated with Con-A, then CD4+ T cells purified, washed, and treated with 5 μM 5-azaC, 20 μM H2O or 20μM ONOO− for another 72 hours as before. The cells were then washed, suspended in HBSS, and 5×106 cells injected through the tail vein into female SJL mice every 2 weeks for a total of 7 injections. Controls included untreated T cells and HBSS alone.

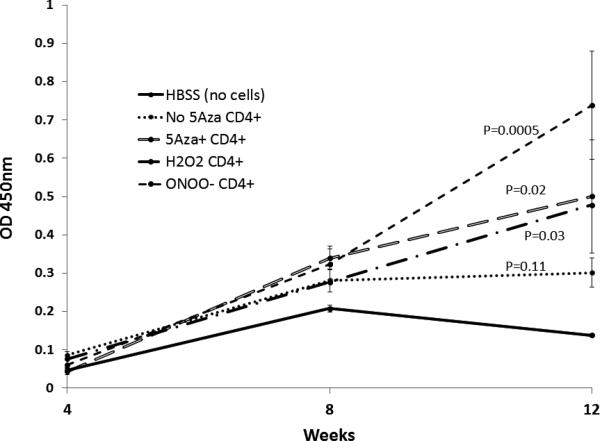

Figure 3 shows that by 12 weeks CD4+ T cells treated with 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO− all stimulate higher levels of anti-DNA antibodies relative to untreated T cells in syngeneic recipient mice (p=0.037 by ANOVA), resembling results from similar experiments reported by our group for procainamide and hydralazine treated T cells [15]. The ONOO− treated T cells caused the highest levels of anti-DNA antibodies at 12 weeks, and were significantly greater than those caused by HBSS (p=0.005) or untreated T cells (p=0.01). Urinary protein levels were measured by dipstick 12 weeks after the first injection in mice receiving untreated CD4+ T cells or CD4+ T cells treated with 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO−. Table 1 shows that mice receiving 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO− treated CD4+ T cells, but not untreated T cells, also developed significantly greater proteinuria relative to mice receiving HBSS alone (p<0.04). No hematuria was observed (not shown).

Figure 3. CD4+ T cells treated with 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO− cause anti-DNA antibodies in syngeneic mice.

CD4+ T cells treated as described for Fig. 1 were injected (5×106 cells/recipient) into the tail veins of female SJL mice every 2 weeks for a total of 7 injections. Controls included mice receiving untreated T cells and HBSS alone. Blood was obtained 4, 8 and 12 weeks after the first injection and serum anti-dsDNA antibody levels measured by ELISA. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM of groups of 5-8 mice. The linear mixed model of ANOVA was used to assess the statistical significance of the effects of different treatments on antibody production relative to HBSS injections without cells over time. P values shown are versus mice treated with HBSS (no cells).

Table 1.

CD4+ T cells treated with 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO− cause proteinuria in SJL mice

| Treatment | Proteinuria | P (vs HBSS) |

|---|---|---|

| HBSS | 0/5 | |

| Untreated T cells | 2/9 | NS |

| 5-azaC treated T cells | 4/5 | 0.01 |

| H2O2 treated T cells | 4/7 | 0.038 |

| ONOO− treated T cells | 7/10 | 0.01 |

Female SJL mice received i.v. injections of HBSS or 5×106 CD4+ T cells treated with the indicated agents every other week for a total of 7 injections. Urine protein was measured serially using dipsticks. P values were calculated using Chi-square statistics. Proteinuria : ≥30mg/dl protein for ≥2 consecutive wk.

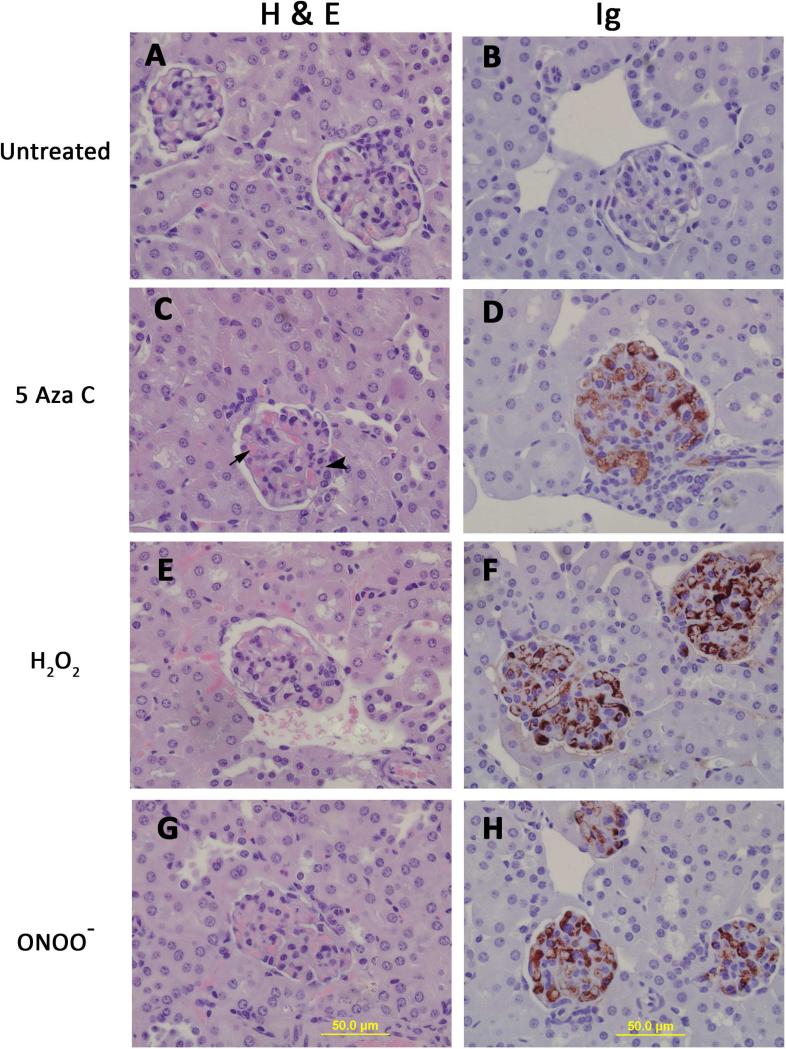

At 14 weeks the mice were sacrificed and kidneys removed for histologic analysis. Figure 4 shows hematoxylin and eosin (left) and anti-IgG (right) stained kidney sections from mice receiving untreated, 5-azaC treated, H2O2 treated or ONOO− treated CD4+ T cells. Panels A and B show representative glomeruli from mice receiving untreated T cells. The glomeruli are normal. Glomeruli from mice receiving 5-azaC treated CD4+ T cells (panel C) exhibited hypercellularity, hyaline thrombi (arrow) and karyorrhexis (arrow head). IgG deposits (panel D) were also detected in the glomeruli from these animals. Similarly glomeruli from mice receiving H2O2 treated T cells (Fig. 4E, F) and from mice receiving ONOO− treated T cells (Fig 4G, H) exhibited hypercellularity, hyaline thrombi and karyorrhexis. IgG staining was more intense in the glomeruli from these mice compared with animals that received 5-azaC treated cells and is consistent with the higher levels of anti-dsDNA antibody produced in mice receiving H2O2 or ONOO− treated cells. Together these studies demonstrate that CD4+ T cells treated with the Dnmt1 inhibitor 5-azaC, or the oxidizing agents H2O2 or ONOO− are sufficient to cause anti-DNA antibodies and an immune complex glomerulonephritis in genetically predisposed mice.

Figure 4. CD4+ T cells treated with 5-azaC, H2O2 or ONOO− cause an immune complex glomerulonephritis in syngeneic mice.

14 weeks after the first injection the mice were sacrificed and kidneys removed for histologic analysis. Hematoxylin and eosin stained kidney sections from mice receiving untreated (A), 5-azaC treated (C), H2O2 treated (E) or ONOO− treated (G) CD4+ T cells. Kidney sections from the same mice tested for IgG deposition using immunoperoxidase staining. Glomeruli from mice receiving 5-azaC (D). H2O2 (F) and ONOO− (H) treated CD4+ T cells all show IgG deposition, identified by the red deposits while mice receiving untreated T cells (B) do not. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

4. DISCUSSION

A relatively extensive body of literature implicates CD4+ T cell DNA demethylation in lupus onset and flares. Early work demonstrated that inhibiting DNA methylation in CD4+ T cells with 5-azaC alters gene expression and converts polyclonal as well as cloned antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in autoreactive cells that respond to self class II MHC determinants without the addition of specific antigen [16, 17]. The autoreactivity was traced to overexpression of the adhesion molecule LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18), due to demethylation of the ITGAL (CD11a) gene [18], and causing LFA-1 overexpression by transfection caused a similar MHC-restricted autoreactivity [19]. Importantly, both the drug treated and the transfected T cells were sufficient to cause lupus-like autoimmunity when injected i.v. into syngeneic mice [20]. The autoreactivity may be due to increased costimulatory signaling caused by increased LFA-1 expression, because causing LFA-1 overexpression by transfection resulted in a similar autoreactivity [19]. Alternatively, LFA-1 – ICAM 1 complexes surround the T cell receptor-class II MHC molecule complex to form the “immunologic synapse” [21]. The increased LFA-1 levels may also over stabilize the normally low affinity interaction between the T cell receptor and class II MHC molecules without the appropriate peptide in the antigen binding cleft, causing T cell activation [19]. Similarly, procainamide and hydralazine, which cause a lupus-like disease in genetically predisposed people [22], also decrease total CD4+ T cell DNA methylation, causing ITGAL overexpression and T cell autoreactivity similar to that caused 5-azaC [20], providing another example of exogenous agents causing lupus-like autoimmunity through T cell DNA demethylation. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the same changes in ITGAL methylation and expression are found in T cells treated with procainamide and in T cells from patients with active lupus. Further, the degree of demethylation and overexpression are directly related to disease activity as measured by the SLEDAI [23], suggesting that similar mechanisms may contribute to drug induced and idiopathic human lupus flares. Later studies demonstrated that 5-azaC also demethylates and causes overexpression of genes encoding perforin, CD70, CD40L and the KIR gene family and that these genes are also demethylated and overexpressed by lupus T cells [14]. Perforin contributes to autoreactive macrophage killing [24], while CD70 and CD40L contribute to antibody overstimulation [25, 26], and KIR contributes to interferon-γ overproduction and autoreactive macrophage killing [27].

Mechanistic studies revealed that the lupus T cell DNA methylation defect is due to low Dnmt1 levels, caused by a failure to upregulate Dnmt1 during mitosis, and that decreased ERK pathway signaling contributes to the low Dnmt1 levels [28]. The lupus T cell ERK pathway signaling defect was traced to PKCδ, which fails to autophosphorylate when stimulated with PMA [3]. Interestingly, the lupus-inducing drug hydralazine also inhibits T cell PKCδ activation [3], and PKCδ mutations cause lupus in people [29] and mice [30], suggesting an important role for PKCδ inactivation in lupus pathogenesis.

Later studies demonstrated that PKCδ is nitrated in T cells from patients with active lupus, similar to the serum protein nitration found in patients with active lupus [4]. Further, immunoprecipitations with anti-3-nitrotyrosine antibodies revealed that the nitrated PKCδ fraction is refractory to PMA stimulation, while the unmodified fraction retained PMA-stimulated autophosphorylation activity, indicating that the PKCδ signaling function is sensitive to nitration [5]. More recent studies confirmed that treating human CD4+ T cells with H2O2 or ONOO− similarly inhibits PKCδ activation, decreasing ERK pathway signaling, decreasing Dnmt1 levels and causing demethylation and overexpression of genes found to be demethylated and overexpressed in T cells from patients with active lupus, including CD70 [29] and the Kir gene family [31]. These studies also revealed that ONOO− is more potent than H2O2. This may reflect a requirement for H2O2 to combine with endogenous NO to form ONOO− which then inactivates PKCδ [5] as well as causing the protein nitration that characterizes lupus flares [4]. Together these studies indicate that oxidizing agents can epigenetically modify CD4+ T cells in vitro to resemble CD4+ T cells from patients with active lupus. However, whether the modified cells are capable of causing autoimmunity in vivo was unknown.

The studies described in the current report extend these observations by demonstrating that ONOO− and H2O2 also cause overexpression of mouse T cell genes normally suppressed by DNA methylation, similar to their effects on human T cells [32]. Importantly, the present studies also demonstrate that injecting the oxidized, epigenetically altered murine CD4+ T cells into syngeneic mice is sufficient to cause a lupus-like disease with anti-DNA antibodies and an immune complex glomerulonephritis similar to that caused by other DNA methylation inhibitors such as procainamide, hydralazine or 5-azaC [2], suggesting a mechanism for the association of oxidative stress with lupus flares. The autoimmunity induced by the treated cells is not due to necrotic cells caused by treatment with ONOO− or H2O2 because we have previously reported that heat killed, necrotic T cells do not cause lupus-like autoimmunity in similar adoptive transfer experiments [2].

In summary, clinical observations indicate that agents which cause oxidative stress, such as infections [33], sun exposure [34], silica [35] and smoking [36], are associated with lupus onset and flares. The studies described above indicate that CD4+ T cells exposed to reactive oxygen species are sufficient to cause lupus-like autoimmunity in mice. Together these reports suggest that environmentally induced oxidative stress may trigger lupus flares in genetically predisposed people through effects on T cell signaling and DNA methylation. These studies also support the use of anti-oxidants to treat lupus flares, as reported by others [37].

Highlights.

We previously showed that oxidizing agents decreased ERK pathway signaling in human T cells, decreased DNA methyltransferase 1 and caused demethylation and overexpression of genes similar to those from patients with active lupus.

The current study tested whether oxidant-treated T cells can induce lupus in mice.

CD4+ T cells treated in vitro with hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxide decreased Dnmt1 expression in CD4+ T cells and caused the upregulation of genes known to be suppressed by DNA methylation in patients with lupus and animal models of SLE.

Adoptive transfer of oxidant-treated CD4+ T cells into syngeneic recipients resulted in the induction of anti-dsDNA antibody and glomerulonephritis.

The results demonstrate that oxidative stress may contribute to lupus disease by inhibiting ERK pathway signaling in T cells leading to DNA demethylation, upregulation of immune genes and autoreactivity

Acknowledgements

We thank Erin Grant for her excellent technical assistance and Ms. Stacy Fry for her excellent secretarial assistance. We also thank Dr. Gabriela Gorelik for helpful discussions and advice on oxidative stress and PKC-δ. This work was supported by PHS grants AR42525 and ES017885, a Merit grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Lupus Insight Prize from the Lupus Foundation of America, the Alliance for Lupus Research and the Lupus Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Somers EC, Richardson BC. Environmental exposures, epigenetic changes and the risk of lupus. Lupus. 2014;23:568–76. doi: 10.1177/0961203313499419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quddus J, Johnson KJ, Gavalchin J, Amento EP, Chrisp CE, Yung RL, et al. Treating activated CD4+ T cells with either of two distinct DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, 5-azacytidine or procainamide, is sufficient to cause a lupus-like disease in syngeneic mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1993;92:38–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI116576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorelik G, Fang JY, Wu A, Sawalha AH, Richardson B. Impaired T cell protein kinase C delta activation decreases ERK pathway signaling in idiopathic and hydralazine-induced lupus. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:5553–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oates JC, Gilkeson GS. The biology of nitric oxide and other reactive intermediates in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical immunology. 2006;121:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorelik GJ, Yarlagadda S, Patel DR, Richardson BC. Protein kinase Cdelta oxidation contributes to ERK inactivation in lupus T cells. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64:2964–74. doi: 10.1002/art.34503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Gorelik G, Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Oxidative stress, T cell DNA methylation, and lupus. Arthritis & rheumatology. 2014;66:1574–82. doi: 10.1002/art.38427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewagama A, Gorelik G, Patel D, Liyanarachchi P, McCune WJ, Somers E, et al. Overexpression of X-linked genes in T cells from women with lupus. Journal of autoimmunity. 2013;41:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strickland FM, Hewagama A, Wu A, Sawalha AH, Delaney C, Hoeltzel MF, et al. Diet influences expression of autoimmune-associated genes and disease severity by epigenetic mechanisms in a transgenic mouse model of lupus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013;65:1872–81. doi: 10.1002/art.37967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Kuick R, Hanash S, Richardson B. DNA methylation inhibition increases T cell KIR expression through effects on both promoter methylation and transcription factors. Clinical immunology. 2009;130:213–24. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson B, Sawalha AH, Ray D, Yung R. Murine models of lupus induced by hypomethylated T cells (DNA hypomethylation and lupus...). Methods in molecular biology. 2012;900:169–80. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-720-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strickland FM, Hewagama A, Lu Q, Wu A, Hinderer R, Webb R, et al. Environmental exposure, estrogen and two X chromosomes are required for disease development in an epigenetic model of lupus. Journal of autoimmunity. 2012;38:J135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Q, Wu A, Tesmer L, Ray D, Yousif N, Richardson B. Demethylation of CD40LG on the inactive X in T cells from women with lupus. Journal of immunology. 2007;179:6352–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouhi A, Gagnier L, Takei F, Mager DL. Evidence for epigenetic maintenance of Ly49a monoallelic gene expression. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:2991–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson B. Primer: epigenetics of autoimmunity. Nature clinical practice Rheumatology. 2007;3:521–7. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yung R, Chang S, Hemati N, Johnson K, Richardson B. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. IV. Comparison of procainamide and hydralazine with analogs in vitro and in vivo. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1997;40:1436–43. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, Johnson KJ, Richardson BC. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. Cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. Journal of immunology. 1995;154:3025–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornacchia E, Golbus J, Maybaum J, Strahler J, Hanash S, Richardson B. Hydralazine and procainamide inhibit T cell DNA methylation and induce autoreactivity. Journal of immunology. 1988;140:2197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu Q, Ray D, Gutsch D, Richardson B. Effect of DNA methylation and chromatin structure on ITGAL expression. Blood. 2002;99:4503–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richardson B, Powers D, Hooper F, Yung RL, O'Rourke K. Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 overexpression and T cell autoreactivity. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1994;37:1363–72. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, Amento E, Carr D, Laing T, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1996;97:2866–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI118743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bromley SK, Burack WR, Johnson KG, Somersalo K, Sims TN, Sumen C, et al. The immunological synapse. Annual review of immunology. 2001;19:375–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yung RL, Richardson BC. Drug-induced lupus. Rheumatic diseases clinics of North America. 1994;20:61–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu Q, Kaplan M, Ray D, Ray D, Zacharek S, Gutsch D, et al. Demethylation of ITGAL (CD11a) regulatory sequences in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2002;46:1282–91. doi: 10.1002/art.10234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan MJ, Lu Q, Wu A, Attwood J, Richardson B. Demethylation of promoter regulatory elements contributes to perforin overexpression in CD4+ lupus T cells. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:3652–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oelke K, Lu Q, Richardson D, Wu A, Deng C, Hanash S, et al. Overexpression of CD70 and overstimulation of IgG synthesis by lupus T cells and T cells treated with DNA methylation inhibitors. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;50:1850–60. doi: 10.1002/art.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Yuan J, Pan Y, Fei Y, Qiu X, Hu N, et al. T cell CD40LG gene expression and the production of IgG by autologous B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical immunology. 2009;132:362–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basu D, Liu Y, Wu A, Yarlagadda S, Gorelik GJ, Kaplan MJ, et al. Stimulatory and inhibitory killer Ig-like receptor molecules are expressed and functional on lupus T cells. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:3481–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng C, Kaplan MJ, Yang J, Ray D, Zhang Z, McCune WJ, et al. Decreased Rasmitogen-activated protein kinase signaling may cause DNA hypomethylation in T lymphocytes from lupus patients. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001;44:397–407. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200102)44:2<397::AID-ANR59>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belot A, Kasher PR, Trotter EW, Foray AP, Debaud AL, Rice GI, et al. Protein kinase cdelta deficiency causes mendelian systemic lupus erythematosus with B cell-defective apoptosis and hyperproliferation. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2013;65:2161–71. doi: 10.1002/art.38008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyamoto A, Nakayama K, Imaki H, Hirose S, Jiang Y, Abe M, et al. Increased proliferation of B cells and auto-immunity in mice lacking protein kinase Cdelta. Nature. 2002;416:865–9. doi: 10.1038/416865a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawalha AH, Wang L, Nadig A, Somers EC, McCune WJ, Michigan Lupus C, et al. Sex-specific differences in the relationship between genetic susceptibility, T cell DNA demethylation and lupus flare severity. Journal of autoimmunity. 2012;38:J216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel DR, Richardson BC. Epigenetic mechanisms in lupus. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2010;22:478–82. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833ae915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. Infections and SLE. Autoimmunity. 2005;38:473–85. doi: 10.1080/08916930500285352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim A, Chong BF. Photosensitivity in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine. 2013;29:4–11. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee S, Hayashi H, Maeda M, Chen Y, Matsuzaki H, Takei-Kumagai N, et al. Environmental factors producing autoimmune dysregulation--chronic activation of T cells caused by silica exposure. Immunobiology. 2012;217:743–8. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costenbader KH, Karlson EW. Cigarette smoking and systemic lupus erythematosus: a smoking gun? Autoimmunity. 2005;38:541–7. doi: 10.1080/08916930500285758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perl A. Oxidative stress in the pathology and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2013;9:674–86. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]