Abstract

Depression and generalized anxiety, separately and as comorbid states, continue to represent a significant public health challenge. Current cognitive-behavioral treatments are clearly beneficial but there remains a need for continued development of complementary interventions. This manuscript presents two proof-of-concept studies, in analog samples, of “microinterventions” derived from regulatory focus and regulatory fit theories and targeting dysphoric and anxious symptoms. In Study 1, participants with varying levels of dysphoric and/or anxious mood were exposed to a brief intervention either to increase or to reduce engagement in personal goal pursuit, under the hypothesis that dysphoria indicates under-engagement of the promotion system whereas anxiety indicates over-engagement of the prevention system. In Study 2, participants with varying levels of dysphoric and/or anxious mood received brief training in counterfactual thinking, under the hypothesis that inducing individuals in a state of promotion failure to generate subtractive counterfactuals for past failures (a non-fit) will lessen their dejection/depression-related symptoms, whereas inducing individuals in a state of prevention failure to generate additive counterfactuals for past failures (a non-fit) will lessen their agitation/anxiety-related symptoms. In both studies, we observed discriminant patterns of reduction in distress consistent with the hypothesized links between dysfunctional states of the two motivational systems and dysphoric versus anxious symptoms.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, cognitive-behavioral therapy, regulatory focus theory, regulatory fit theory, self-regulation

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are two of the most prevalent psychiatric disorders and leading causes of disability worldwide. Epidemiological studies find that MDD/GAD comorbidity occurs at least as frequently as MDD without GAD and much more frequently than GAD without MDD (e.g., Mineka et al., 1998; Zbozinek et al., 2012). Most individuals with MDD also report a history of an anxiety disorder (Fava et al., 2000; Kaufman et al., 2000). GAD is highly comorbid, with 60-70% of GAD patients having a lifetime history of MDD (Carter et al., 2001; Kessler et al., 1999). That GAD/MDD comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception can be observed as early as adolescence (van Lang et al., 2006), indicating that treatments should ideally be able to target both kinds of distress. Although existing interventions are efficacious, a significant proportion of MDD and GAD patients don't fully recover, and among those who do, most will experience relapse or recurrence (Mogg & Bradley, 2005). There is increasing evidence that MDD and GAD are characterized by both common and unique underlying mechanisms (Krueger et al., 2005). Nonetheless, there remains an urgent need for treatment innovations for MDD, GAD, and their comorbid states. In this manuscript we present two proof-of-concept studies, in analog samples, applying a well-validated behavioral science model to the clinical challenge of dealing with dysphoric and anxious symptoms.

Self-Discrepancy, Regulatory Focus, and Vulnerability to Depression vs. Anxiety

Effective goal pursuit behavior is fundamental to mental health and well-being (Elliot & Sheldon, 1998; Kahneman, Diener, & Schwarz, 1998). Central to life's pleasures and pains is success or failure in pursuit of approach and avoidance goals, including knowing when to keep what one is or has and when to change for something new. Surprisingly, however, there are relatively few interventions for mood and anxiety disorders based on the psychological principles that underlie approach and avoidance (Dozois, Seeds, & Collins, 2009; Holtforth, Pincus, Grawe, Mauler, & Castonguay, 2007; Karoly, 2010; Klinger & Cox, 2004). Such an alternative approach to reduction of dysphoric and anxious symptoms may provide a useful complement to existing cognitive-behavioral techniques.

The hedonic principle – that people approach pleasure and avoid pain – is the basic motivational assumption of theories across many areas of psychology (e.g., Atkinson, 1964; Festinger, 1957; Freud, 1952/1920; Gray, 1982; Heider, 1958; Kahneman & Tversky,1979; Mowrer, 1960; Thorndike, 1935). In spite of the wide applicability of this principle, however, its limitations have become apparent over the past several decades. The problem with the hedonic principle is not that it is wrong, but rather that its dominance has taken attention away from other principles that concern the different ways that people approach pleasure and avoid pain (Higgins, 1997) – different ways that influence the emotional and motivational consequences of perceived success and failure in goal pursuit. The two studies reported below examined the implications of differences in what constitutes “failure” in personal goal pursuit for developing targeted intervention techniques for MDD, GAD, and their comorbidity.

Self-discrepancy theory (SDT; Higgins, 1987) was developed to conceptualize how problems in self-regulation of personal goal pursuit contribute to mood and anxiety disorders. SDT identified two types of personal goals or self-guides: hopes and aspirations (ideal self-guides) versus duties and obligations (ought self-guides). The theory predicted that when individuals failed to meet their ideals, they would suffer from dejection/dysphoria, whereas when individuals failed to meet their oughts, they would suffer from agitation/anxiety. According to SDT, what produces these different emotional syndromes are the different psychological situations that people experience depending on which type of self-guide they are using. When events are construed in reference to ideals (hopes and aspirations), we experience success as a gain and failure as a non-gain. This gain/non-gain construal triggers emotions such as happiness, joy, and satisfaction when we succeed and sadness, frustration, and disappointment when we fail. In contrast, when events are construed in reference to oughts (duties and obligations), we experience success as a non-loss and failure as a loss. This loss/non-loss construal triggers emotions such as calmness and quiescence when we succeed and worry, guilt, and anxiety when we fail (Higgins & Tykocinski, 1992; Strauman, 1992).

SDT provided an integrative translational model linking self-regulatory cognition with the basic science literatures on motivation and emotion. Over the last two decades, numerous studies have found support for its predictions (for reviews, see Higgins, 1998, 2001). In addition, SDT recognized that specific situations could influence whether a person's ideals or oughts were more accessible at that moment. Whichever type of self-guide was more accessible would determine whether that particular situation was construed in reference to the person's ideal or ought guides, which in turn would determine which affective experiences resulted. Evidence for such emotional variability across situations as a function of the accessibility of ideal and ought guides from contextual priming has also been found in numerous studies (e.g., Andersen & Baum, 1994; Shah, 2003; Strauman & Higgins, 1987).

Regulatory focus theory (RFT; Higgins, 1998) is a more general model of self-regulation which built upon SDT by distinguishing between a promotion system that is concerned with nurturance, advancement, and fulfilling hopes (ideals) and a prevention system that is concerned with security, safety, and fulfilling duties (oughts). RFT emphasizes that promotion failure and prevention failure, along with their accompanying affective and motivational experiences, were psychological states. If either the promotion or prevention system were activated in any specific situation and a personally significant failure were to occur in that situation, then acute system-specific distress would also occur: dejection/dysphoria in the case of promotion failure and agitation/anxiety in the case of prevention failure (Idson et al., 2000). In contrast to the behavioral activation/inhibition systems, which operate as “bottom-up” systems in response to cues for spatiotemporal approach and avoidance, respectively (Depue & Collins, 1999; Watson et al., 1999), the promotion and prevention systems are “top-down” socialization-based systems for strategic approach (eager strategies) and avoidance (vigilant strategies) in response to activation of generalized goals or concerns (Strauman & Wilson, 2010). Indeed, there is evidence from functional neuroimaging studies to suggest that these two sets of approach/avoidance systems have distinguishable neural activation correlates (Strauman et al., 2013).

As had been postulated originally in SDT, promotion and prevention goal failure are associated with specific affective and motivational consequences. Depression is associated with actual:ideal discrepancy, a promotion system failure, whereas anxiety is associated with actual:ought discrepancy, a prevention system failure (Strauman & Higgins, 1988; Strauman, 1989, 1992). But RFT makes additional predictions about the antecedents and consequences of personal goal pursuit. Promotion failure is experienced as the absence of a positive outcome (a non-gain), whereas prevention failure is experienced as the presence of a negative outcome (a loss). Recent mechanism-focused research on RFT has found that when the promotion system is active, what matters to individuals at that moment is to advance from a current status quo “0” to attain a better “+1” state – to make progress (e.g., Brodscholl et al., 2007; Zou, Scholer, & Higgins, 2014). In contrast, when the prevention system is active, what matters to individuals at that moment is to maintain a safe status quo “0” and not fall to a worse “-1” state (e.g., Brodscholl et al., 2007; Scholer et al., 2010).

This mechanistic distinction is important because it clarifies the critical difference between an active promotion state versus an active prevention state in what makes unsuccessful goal pursuit distressing; i.e., what constitutes a “failure.” What is critical is not just the particular kind of personal goal that the individual is pursuing (e.g., ideal vs. ought) but also the meaning of the individual's current state “0.” In the prevention system, “0” is positive and it is moving below “0” that is a failure. In contrast, in the promotion system, remaining at “0” is a failure and moving from “0” to “+1” is positive. The critical nature of this distinction is revealed by considering what happens when individuals construe themselves as being in a worse (“-1”) state compared to the status quo “0” – a set of circumstances in which individuals with depressive and/or anxious symptoms regularly find themselves. Although being in a worse state is clearly negative within both systems, how to make things better presents a different challenge for promotion versus prevention. When individuals are in a prevention state, any behavioral option that gets back to the safe status quo “0” state is desirable – that is, the psychological mandate is to get back to “0” (Scholer et al., 2011). However, in a promotion state there is no value in simply getting back to “0” because it still constitutes a failure (Scholer et al., 2011; Zou et al., 2014). Thus, RFT suggests that helping people who are construing themselves as failing in personal goal pursuit requires creating different interventions for a prevention failure versus a promotion failure. Furthermore, the many individuals who experience both dysphoric and anxious symptoms are likely to be experiencing two different kinds of perceived failure at different times, and therefore are likely to benefit from both kinds of interventions at different times—targeting promotion failure when they experience dysphoric symptoms and prevention failure when they experience anxious symptoms.

Regulatory Focus/Regulatory Fit as Bases for Novel Intervention Strategies

According to RFT, although promotion failure and prevention failure are both painful, they differ in fundamental ways. Research on regulatory fit (Higgins, 2006) provides critical insights into the psychological mechanisms that underlie these differences. In particular, regulatory fit theory postulates that the two types of failure experiences have different effects on behavior. Promotion failure reduces the eagerness needed to successfully pursue promotion goals, whereas prevention failure increases the vigilance needed to successfully pursue prevention goals (Higgins, 2006). Thus, chronic promotion system failure could intensify and maintain the anhedonic, hypomotivated state (reduced eagerness) that characterizes MDD (Depue and Iacono, 1989; Strauman, 1989; Watson et al., 1999). In contrast, chronic prevention system failure could intensify and maintain the hypervigilant, nondirected state that characterizes GAD (Borkovec et al., 2004; Clark, 2005; Strauman, 1989).

The concept of regulatory fit suggests novel ways to lessen distress resulting from goal pursuit failure. One potential target for intervention stems from the observation that in the context of goal pursuit, a sense of non-fit reduces confidence in one's evaluative response to something—it makes people feel less certain about their evaluation (e.g., Cesario et al., 2004). Given that judgments of failure are evaluative responses, reducing certainty about such judgments should lessen their emotional and motivational impact. One way to reduce confidence in failure judgments is by targeting counterfactual thinking about a failure (“What might I have done differently?”), which has been shown to intensify the negative motivational and affective consequences of perceived failure (e.g., Martin and Tesser, 1996; Papadakis et al., 2006). Roese, Hur, & Pennington (1999) observed that promotion failure was more likely to produce counterfactual thinking about correcting a past error of omission by changing the “0” state to a “+1” state (an additive counterfactual). In comparison, prevention failure was more likely to produce counterfactual thinking about correcting a past error of commission by changing a “-1” state to a “0” state (a subtractive counterfactual).

Based on Roese et al.'s application of regulatory fit theory, we hypothesized that altering the counterfactuals that distressed individuals typically generate by creating non-fitting counterfactuals could reduce the certainty of their self-evaluation and thus also reduce distress. Specifically, we predicted that inducing individuals with a promotion failure to generate subtractive counterfactuals for past failures would lessen their depression-related symptoms. In contrast, inducing individuals with a prevention failure to generate additive counterfactuals for past failures would lessen their anxiety-related symptoms.

Other characteristics of goal pursuit also could be used to counteract the distress resulting from goal pursuit failure, by either increasing or decreasing engagement in goal pursuit activities (Higgins, 2006). Obstacles to goal pursuit, which arise continuously in the ongoing process of self-regulation, can be dealt with either by disengaging from what one is doing or by engaging more strongly in what one is doing. Based on the psychological characteristics of promotion vs. prevention goal pursuit, these different ways of dealing with adversity could be used tactically – that is, by intentionally decreasing or increasing individuals’ goal pursuit engagement strength (see Higgins, Marguc, & Scholer, 2012). We hypothesized that because promotion failure can lead to a hypomotivated, underengaged, dysphoric state, intervening to increase engagement in promotion goal pursuit could be effective in reducing depressive symptoms. In contrast, because prevention failure can lead to a hypermotivated, overengaged, agitated state, we hypothesized that intervening to decrease engagement in prevention goal pursuit would be effective in reducing anxious symptoms.

Using Microinterventions to Test Hypotheses About Psychotherapy Mechanisms of Action

Although psychosocial interventions are effective for a broad range of mental disorders, traditional approaches to psychotherapy development usually evaluate combinations or packages of interventions rather than single techniques (Goldfried, 2010; Youn et al., 2012). There are good reasons for this approach. Nonetheless, the field has matured sufficiently to permit a complementary therapy development strategy (Grawe, 2006; Harwood et al., 2011). So-called “macro”, “meso”, and “micro” levels of analysis each contribute essential insights into behavior change and each level contributes uniquely to psychosocial intervention research (Lutz et al., 2005, 2009). Nonetheless, knowledge from behavioral science and neuroscience often translate most readily into interventions when the translational effort focuses on linking specific techniques with specific hypothesized targets – that is, the “micro” level (Sanislow et al., 2010). At this level, reliable associations between particular techniques or interventions and particular changes in behavior, affect, or cognition are easier to detect. In addition, hypotheses regarding dysfunctional neural or psychological mechanisms are easier to test when such putative mechanisms are manipulated as precisely as possible. Microinterventions have the virtue of balancing internal and external validity in a way that facilitates translation and testing of basic theory in behavioral science and neuroscience (Insel et al., 2013). Each of the two proof-of-concept studies below incorporated a novel theory-based microintervention strategy in order to test a set of hypotheses regarding complementary strategies to acutely lessen dysphoric and anxious distress.

Study 1: Altering Strength of Engagement in Personal Goal Pursuit

The purpose of this study was to use regulatory focus and regulatory fit theories to develop and test a microintervention for reducing dysphoric and anxious distress. The underlying hypothesis was that depressive states are characterized by inadequate engagement of the promotion system, whereas anxious states are characterized by excessive engagement of the prevention system. If the promotion system is chronically underactive, the individual is likely to experience decreased approach motivation, loss of interest, anhedonia, and related symptoms. In contrast, if the prevention system is chronically overactive, the individual is likely to experience agitation, hypervigilance, and worry. In addition to supporting “success” self-evaluations (e.g., more positive, evidence-based self-construals as is done routinely in cognitive-behavioral therapy), what else might be done to help individuals regulate promotion/prevention engagement strength? We proposed a complementary strategy based on how framing effects can alter promotion and prevention engagement strength; in particular, the findings of Higgins and colleagues (2012) regarding the differential acute effects on self-regulation of framing an adversity as either “opposing an interference” or “coping emotionally with a nuisance.”

Method

Overview

Individuals previously reporting mild to moderate levels of chronic dysphoric and/or anxious symptoms participated in a one-session analog therapeutic intervention in which they were presented with a script describing coping with distress in two ways: either as overcoming obstacles as interferences that needed to be opposed (intended to increase promotion engagement strength) or as viewing the distress as a nuisance that needed to be coped with by receiving attention (intended to decrease prevention engagement strength). After providing informed consent, participants completed the PANAS (current affect version) and were then randomized to one of four intervention conditions: overcoming obstacles (targeting dysphoric symptoms), viewing distress as a nuisance (targeting anxious symptoms), the combination of the two strategies, or an active control intervention (nonspecific coping strategies targeting neither kind of symptom). After the intervention, each participant then completed another PANAS to determine the acute impact on mood, if any, of the intervention s/he received.

Participants

We assessed dysphoric and anxious symptoms based on a combination of self-report measures. Participants initially were screened as part of a larger ongoing study (which had included assessment of self-discrepancy, regulatory focus and dysphoric/anxious mood) and were then recruited specifically for this study based on their self-reported dysphoric and anxious mood. Participants received token cash compensation for their time in each separate session of the overall study.

Instruments

The questionnaires administered during the initial screening session were:

-

(1)

Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (RFQ; Higgins et al., 2001). The RFQ is a 11-item Likert-type questionnaire assessing individual differences in self-regulatory orientation. Each subscale has an internal consistency (coefficient alpha) of .75 or higher, and two-month test-retest reliability (Pearson correlation) of .79 or higher. The present study used two RFQ subscales, one assessing the individual's overall sense of being successful in promotion goal-pursuit (promotion success) and the other assessing the individual's overall sense of being successful in prevention goal-pursuit (prevention success). The RFQ serves as one measure of promotion strength and prevention orientation.

-

(2)

Computerized Goal Assessment (CGA; Shah & Higgins, 2001). Shah developed a computerized measure that asks participants to list ideal and ought goals. Specifically, the program asks each participant to list distinct attributes of the ideal and ought self and then presents them in random order, asking the participant to rate on a 0-4 scale how much they believe they actually possess the attribute (0=not at all, 4=extremely), which are then used to generate actual:ideal and actual:ought self-discrepancy scores. Participants generate a total of five ideal and five ought goals and the same attribute cannot be listed more than once.

Afterwards, the program presents a reaction-time task: each attribute generated by the participant (plus control words) is presented one at a time, and the participant is asked to make a simple relevant to me/not relevant to me judgment. The latency to make this judgment is combined across all ideal and all ought attributes, respectively (after appropriate transformation to reduce skewness), to create promotion and prevention goal accessibility scores, which serves as a measure of promotion strength and prevention strength, respectively. In previous studies, the self-discrepancy scores showed a one-month test-retest reliability (Pearson correlation) exceeding .70, and the accessibility scores showed a one-month test-retest reliability (Pearson correlation) exceeding .60 (Higgins, 1987). (3) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961). The BDI is a 21-item self-report inventory in which each item corresponds to a common symptom of depression. Each of the 21 symptoms is rated on a scale from 0 (the symptom is absent) to 3 (the symptom is experienced in its extreme). The BDI has excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Dobson and Breiter, 1983).

-

(4)

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988). The BAI is a 21-item self-report inventory in which each item addresses a symptom commonly associated with anxiety. Each of the 21 symptoms is rated on a scale from 0 (the symptom is absent) to 3 (the symptom is experienced in its extreme). The BAI likewise has excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Fydrich, Dowdall, and Chambliss, 1992).

-

(5)

Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Questionnaire (CES-D; Weissman et al., 1977). The CES-D is a well-validated screening tool for mild, moderate, and severe dysphoric symptoms which provides reliable cutoff scores that approximate clinically significant levels of distress. The CES-D has excellent psychometric characteristics, including both internal consistency and test-retest reliability (Radloff, 1977).

-

(6)

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, and Jacobs, 1983). This study used only the state anxiety portion of the STAI, a 20-item inventory of instantaneous anxiety level. The STAI consists of 20 statements about current feeling that are rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much so). The STAI has shown excellent internal consistency and moderate test-retest reliability in previous studies (Spielberger, 1989).

At the second screening session two weeks later, participants completed a set of questionnaires including the BDI, CES-D, BAI, and STAI. To be eligible for the experimental study (see below), participants had to score 12 or higher on both administrations of the BDI and 10 or higher on both administrations of the CES-D (indicating at least mild chronic dysphoric mood), or 10 or higher on both administrations of the BAI as well as 25 or higher on both administrations of the STAI (indicating at least mild chronic anxious mood). Of the 310 participants screened, 89 met these criteria.

Procedure

Participants were recruited for what was described as a study of strategies to deal with stress, a minimum of one month after the second screening session. They were recruited by the same experimenters who conducted the screening sessions but without reference to any specific criteria, rather simply via offering participation in a follow-up study for additional compensation. After providing informed consent, each individual participant completed the PANAS (current affect version) and then was randomized to one of four intervention conditions: overcoming obstacles (targeting dysphoric symptoms by increasing promotion engagement strength), coping with a nuisance (targeting anxious symptoms by decreasing prevention engagement strength), both strategies, or an active control intervention (involving relaxed breathing and brief practice of cognitive reappraisal strategies). The specific intervention was presented by the experimenter in the form of a brief interactive script which the experimenter discussed with the participant for approximately 10 minutes.1 As part of the process, the participant was encouraged to generate examples of current problematic situations and to apply the technique described in the script to those situations. After the intervention, the participant completed another PANAS to determine the acute impact of the interventions on mood as well as a set of questions adapted from the Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000) asking her/him to rate the overall credibility, quality, and impact of the microintervention script.2 Each participant was then debriefed and thanked and received a small cash payment.

Our model postulated that individuals with chronic dysphoric mood would be characterized by hypo-engagement of the promotion system, whereas individuals with chronic anxious mood would be characterized by hyper-engagement of the prevention system. We predicted that dealing with distressing situations by construing them as obstacles to be opposed and overcome (thereby increasing promotion engagement strength) would lead to acute reduction of dysphoric mood, whereas dealing with distressing situations as unpleasant feelings to be coped with as a nuisance (thereby decreasing prevention engagement strength) would lead to acute reduction of anxious mood.

Statistical power calculations for this study were based on procedures described by Hedecker, Gibbons, & Waternaux (1999) for determining power in group-based longitudinal studies. The sample (N = 66) provided a power of 0.80 to detect a standardized effect size of 0.74. All analyses were conducting using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, USA). Significance tests were based on a two-tailed α of 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Mood change by intervention condition

Table 1 summarizes the mood ratings on the PANAS positive affect and negative affect scales before and after the microintervention for participants randomized to each of the four intervention conditions.

Table 1.

Study 1: PANAS Positive and Negative Affect Scores Before vs. After Intervention by Intervention Condition

| Active Control (N=16) | Increase Promotion Engagement Strength (N=17) | Decrease Prevention Engagement Strength (N=19) | Promotion/Prevention Combined (N=14) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PANAS-PA: | ||||

| Pre-Intervention | 18.66 (5.64) | 18.82 (4.88) | 18.60 (6.32) | 17.84 (5.59) |

| Post-Intervention | 19.58 (6.05) | 23.95 (5.98) | 19.01 (6.61) | 23.22 (6.02) |

| PANAS-NA: | ||||

| Pre-Intervention | 21.02 (6.61) | 20.77 (5.08) | 22.01 (6.34) | 21.15 (6.79) |

| Post-Intervention | 20.95 (6.82) | 20.62 (5.97) | 17.94 (6.01) | 16.89 (5.97) |

Note. Means and standard deviations are presented for each intervention condition, time point, and mood type. PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Positive Affect score. PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Negative Affect score.

Analysis of variance with Time (pre-intervention, post-intervention) and PANAS Scale (PA, NA) as within-subject factors and Intervention Condition (Control, Increase Promotion Engagement, Decrease Prevention Engagement, Combined) as a between-subjects factor revealed a significant overall Time x PANAS Scale x Intervention Condition interaction, F(2, 150) = 5.56, p < .01, η2 = .06. This omnibus ANOVA indicated that positive and negative affect changed differentially across the four intervention conditions. Planned post-hoc comparisons then were conducted to test our specific hypotheses. For change in PA (our measure of improvement in dysphoric mood), we conducted a planned contrast comparing the Increase Promotion Engagement Strength and Combined conditions, each of which included an emphasis on increasing promotion engagement, with the Decrease Prevention Engagement Strength and Active Control conditions. We observed that the Increase Promotion Engagement and Combined conditions led to greater improvement in PA than the other two conditions, F(1, 150) = 4.87, p < .02, η2 = .04. Similarly, for change in NA (our measure of reduction in anxious mood), we observed that the Decrease Prevention Engagement and Combined conditions, each of which included an emphasis decreasing prevention engagement, led to greater improvement than the other two conditions, F(1, 150) = 4.43, p < .02, η2 = .04. As a supplementary analysis, we directly compared the Increase Promotion Engagement and Decrease Prevention Engagement conditions. For change in PA, The Increase Promotion Engagement condition showed a marginally greater increase that the Decrease Prevention Engagement condition, F(1, 150) = 3.27, p < .08, η2 = .03. For change in NA, The Decrease Prevention Engagement condition showed a marginally greater decrease that the Increase Promotion Engagement condition, F(1, 150) = 3.46, p < .07, η2 = .03.

Individual differences in self-discrepancy and regulatory focus as moderators

Magnitude of actual:ideal and actual:ought self-discrepancy had been assessed during the initial screening, along with two measures of individual differences regulatory system orientation: average response times to the “ideal self” and “ought self” questions on the Computerized Selves Questionnaire (representing a measure of the strength of promotion/prevention goal accessibility), and scores on the promotion success and prevention success scales of the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (representing the individual's accumulated history of self-perceived success vs. failure in promotion or prevention goal pursuit). To determine whether individual differences in magnitude/type of self-discrepancy or in regulatory system orientation moderated the observed association between specific interventions and change in dysphoric versus anxious mood, we repeated the planned contrast ANOVAs described above six times, each time including one of the potential moderators as both a main effect and an interaction effect (combined with Type of Intervention). Actual:ideal and actual:ought discrepancy did not significantly predict either type of mood change as main effects or as part of an interaction effect (all ps > .25), indicating that the observed differential effects of the microinterventions were not conditional on having a lower versus higher pre-existing level of either type of self-discrepancy. The promotion/prevention goal accessibility measures likewise did not significantly predict either type of mood change (all ps > .35), indicating that the impact of the microinterventions was not conditional on relatively lower versus higher chronic accessibility of an individual's promotion (ideal) or prevention (ought) goals.

However, for the RFQ promotion and prevention success subscales we found statistically significant associations with mood change when those subscales were included in the planned contrast ANOVAs as covariates. Specifically, participants who had previously reported lower levels of self-perceived success in attaining promotion goals manifested greater improvement in PA relative to baseline than participants reporting higher levels of promotion success, but only within the Increase Promotion Engagement and Combined conditions, F(2, 150) = 3.81, p < .05, R2(change) = .04. Similarly, participants who had previously lower levels of self-perceived success in attaining prevention goals manifested greater reductions in NA relative to baseline than participants reporting higher levels of prevention success, but only within the Decrease Prevention Engagement and Combined conditions, F(2, 150) = 3.55, p < .05, R2(change) = .05. There were no significant associations between self-perceived promotion or prevention success and either type of mood change in the Control condition.

The overall pattern of findings indicated specific, discriminant associations between changes in PA (our measure of acute dysphoric mood) versus NA (our measure of acute anxious mood) and the four microintervention conditions. As predicted, the two conditions that were postulated to increase promotion system engagement were associated with reliably greater acute increases in PA, whereas the conditions that were postulated to decrease prevention system engagement were associated with reliably greater acute decreases in NA. There were no significant differences among the four microintervention conditions on our manipulation check questions concerning credibility of the scripts, so the most plausible explanation for these discriminant findings appears to be that, consistent with RFT, dysphoric and anxious mood reflect distinct problems with self-regulation that require different interventions. Moreover, as the individual differences analyses indicated, the two new microinterventions appeared to work especially well for people who were dispositionally more likely to need them – i.e., individuals who previously had reported that they saw themselves as not particularly successful in pursuing their own promotion goals and/or prevention goals. We did not find that either magnitude of self-discrepancy or the accessibility of ideal/ought standards as measured via reaction time moderated the impact of any of the four intervention conditions on either type of distress.

Study 2: Using Counterfactuals to Alter Failure-Related Cognitive Processes

Another potential application of self-regulation theory to reducing dysphoric and anxious symptoms is to decrease the individual's certainty about their judgment that they have failed to attain a goal in order to lessen its emotional and motivational impact. Study 2 was a proof-of-concept investigation involving reducing certainty about failure judgments by targeting counterfactual thinking about a failure. It is common for individuals who are suffering from depression or anxiety to ruminate over past failures by engaging in counterfactual thinking (“What might I have done differently?”), which worsens their symptoms. The study used the principle of regulatory non-fit as a basis for targeted microinterventions by having participants use types of counterfactual thinking that were a non-fit with their current promotion or prevention orientation in order to reduce the certainty of their failure judgments.

As Roese et al. (1999) observed, individuals who report significant levels of anxious symptoms, which is related to chronic failure in the prevention system, are more likely to produce counterfactual thinking about correcting a past error of commission via a subtractive counterfactual (e.g., “What did I do that was wrong that I should not have done?”). Such a counterfactual, however, could increase and aggravate the hypervigilant state resulting from chronic prevention failure. We predicted that inducing individuals experiencing anxiety to generate additive counterfactuals (“What did I fail to do that I might have done?”) for past failures instead (a non-fit to the prevention system) would acutely lessen their anxiety. Similarly, according to Roese et al. (1999), participants who report significant levels of dysphoric symptoms, which are related to chronic failure in the promotion system, are more likely to produce counterfactual thinking about correcting a past error of omission via an additive counterfactual. Such a counterfactual, however, could aggravate the hypo-motivated state resulting from chronic promotion failure. We predicted that inducing individuals with chronic promotion failure (and hence, dysphoric symptoms) to generate subtractive counterfactuals for past failures instead (a non-fit to the promotion system) would acutely lessen their dysphoric affect.

Method

Overview

Individuals previously reporting mild to moderate levels of chronic dysphoric or anxious symptoms, or reporting no symptoms, participated in a one-session analog therapeutic intervention study. After providing informed consent, participants completed a mood checklist and were then assigned to write about a recent event that made them feel down and sad or about an event that made them feel worried and anxious. Participants completed the mood checklist for a second time and were then randomized to one of three intervention conditions: writing an additive counterfactual to the event, writing a subtractive counterfactual to the event, or a control condition consisting of not writing and simply waiting for the next set of instructions. After the intervention, each participant then completed another mood checklist to determine the acute impact on mood, if any, of the intervention s/he received.

Participants

As in Study 1, we assessed dysphoric and/or anxious symptoms based on a combination of self-report measures. Participants initially were screened as part of a larger ongoing study and were then recruited specifically for this study based on their self-reported dysphoric and anxious mood. Participants received token cash compensation for their time in each separate session of the overall study. In this case, we used the same questionnaires as in Study 1 to determine eligibility for the intervention session (see below), which was according to whether participants’ scores fell into one of the following three groups. For the dysphoric group, participants had to score 12 or higher on the BDI and 10 or higher on the CES-D (indicating at least mild chronic dysphoric mood), but 6 or lower on the BAI as well as 18 or lower on the STAI. For the anxious group, participants had to score or 10 or higher on both the BAI as well as 25 or higher on the STAI (indicating at least mild chronic anxious mood), but 8 or less on the BDI and 6 or less on the CES-D. For the nondistressed group, participants had to score 5 or less on the BDI and 4 or less on the CES-D as well as 4 or lower on the BAI as well as 18 or lower on the STAI. Of the 198 respondents who participated in the screening, 114 were eligible for one of the three groups and completed the subsequent intervention session.

Instruments

Participants completed a series of questionnaires in their first visit for screening of chronic mood status and to assess potential covariates, including the same set of measures administered in Study 1: The Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (RFQ), the Computerized Goal Assessment (CGA), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), the Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Questionnaire (CES-D), and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).

Procedure

Participants completed the study in two separate sessions over the course of a summer semester, spaced a minimum of three weeks apart. The first session was a screening and included the aforementioned questionnaires, administered in a random order. Participants whose chronic mood scores fell into one of the three predetermined groups and who agreed to return came for the second visit in which they completed questionnaires and several writing prompts, the latter varying according to which of several possible conditions to which the participant was randomly assigned. A total of 114 participants completed both visits (35 in the dysphoric group, 31 in the anxious group, and 48 in the nondistressed group).

At the start of the second visit, participants completed a 24-item version of the Multiple Affect Adjective Check List, referred to as Mood Checklist A (MCA). Participants were then asked to describe in writing either 1) a problem or hassle from the past week that made them feel down and depressed, or 2) a problem or hassle from the past week that made them feel anxious and nervous. All participants in the dysphoric group, and half of the participants in the nondistressed group, wrote about a problem that made them feel down and depressed. All participants in the anxious group, and the other half of the participants in the nondistressed group, wrote about a problem that made them feel anxious and nervous. Participants within each group then were randomly assigned to write about either a) an additive counterfactual to the problem (“Now think about what action you could have taken, what you could have done that you did not do, that would have been more successful.”), or b) a subtractive counterfactual to the problem (“Now think about what you did to deal with the problem that was a mistake. What might you have done differently?”), or c) a no-writing condition in which participants simply waited for the next set of instructions.

After writing about the assigned type of problem (or simply waiting, for those individuals in the no-writing condition), participants completed an identical 24-item Mood Checklist B (MCB). Those who generated counterfactuals then completed a manipulation check consisting of three statements about the difficulty of generating the desired counterfactual, the extent to which the counterfactual they generated fit or did not fit with the mood they had been in at that moment, and the effectiveness of the counterfactual for changing their mood. Participants rated each statement on a 7-point Likert scale. All participants then were given two opportunities for written rumination, with the first asking participants to recount their problem and add any additional information as desired, and the second asking how the problem had been or might be resolved. Finally, participants completed an identical 24-item Mood Checklist C (MCC). After completing the session, each participant was debriefed and thanked for her/his participation.

Statistical power calculations for this study were based on procedures described by Hedecker et al. (1999) for determining power in group-based longitudinal studies. The sample (N = 114) provided a power of 0.80 to detect a standardized effect size of 0.51. All analyses were conducting using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, USA). Significance tests were based on a two-tailed α of 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Counterfactual condition manipulation checks

Immediately after writing counterfactual statements, participants in the two counterfactual conditions completed a three-item questionnaire as a manipulation check. The first question focused on the overall difficulty of generating the counterfactual. There was no statistically significant difference between the additive and subtractive conditions (p > .5), nor was there a significant difference among the participant groups (p > .25) or a significant Group X Condition interaction (p > .5). These findings indicate that any effects of type of counterfactual generation on the dysphoric versus anxious participants did not derive from differences in experienced difficulty of generating the counterfactual.

The second manipulation check question addressed whether the participants experienced a regulatory non-fit in the intended counterfactual conditions. Participants were asked to rate how well the counterfactual they generated fit with the state of mind they were in at the time. There was no statistically significant difference between the additive and subtractive conditions (p > .5), nor was there a significant difference among the participant groups (p > .5). There was, however, a significant Group X Condition interaction (p < .05) in which two sets of participants rated the fit of the counterfactual they generated as lower than two other sets of participants. As intended, the dysphoric participants who were assigned to generate a subtractive (non-fit) counterfactual (M = 2.98, sd = 1.05) and the anxious participants who were assigned to generate an additive (non-fit) counterfactual (M = 3.14, sd = 1.31) rated the counterfactual they generated as significantly less of a fit with their current state of mind than the anxious and control participants who were assigned to the subtractive counterfactual condition (M = 4.68, sd = 2.01) or the dysphoric and control participants who were assigned to the additive counterfactual condition (M = 5.01, sd = 1.76).

The final manipulation check question focused on participants’ experience of the effectiveness of generating the counterfactual for reducing distress. Again there was no statistically significant difference between the additive and subtractive conditions (p > .25), nor was there a significant difference among the participant groups (p > .25). Again, however, there was a significant Group X Condition interaction (p < .05) in which two sets of participants rated the effectiveness of the counterfactual generating process as greater than two other sets of participants. Consistent with our hypothesis that a non-fit counterfactual would be experienced as more effective, the dysphoric participants who were assigned to generate a subtractive (nonfit) counterfactual (M = 4.52, sd = 1.74) and the anxious participants who were assigned to generate an additive (non-fit) counterfactual (M = 4.59, sd = 1.42) rated the counterfactual exercise as significantly more effective than the anxious and control participants who were assigned to the subtractive counterfactual condition (M = 3.21, sd = 1.12) or the dysphoric and control participants who were assigned to the additive counterfactual condition (M = 3.38, sd = 1.18).

Impact of counterfactuals on mood

The main study hypotheses concerned the acute emotional impact of engaging distressed participants in counterfactual thinking that was a non-fit (vs. a fit) with the negative motivational state associated with chronic regulatory system failure (promotion vs. prevention) and the accompanying type of distress (dysphoric vs. anxious, respectively). Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations on the Mood Checklist dysphoric and anxious affect subscales for each participant group at each time point.

Table 2.

Study 2: Mean Sadness and Anxiety Ratings by Participant Group, Intervention Condition, and Time

| Dysphoric and Wrote About Sad Event (N=35) |

Anxious and Wrote About Anxious Event (N=31) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Counterfactual (N=12) |

Subtractive Counterfactual (N=13) |

No Counterfactual (N=10) |

Additive Counterfactual (N=10) |

Subtractive Counterfactual (N=12) |

No Counterfactual (N=11) |

|||||||

| Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | |

| Time 1 | 2.39 (1.89) | 2.28 (1.66) | 2.42 (1.64) | 2.42 (1.91) | 2.55 (2.01) | 2.17 (1.66) | 2.88 (2.02) | 3.01 (1.59) | 2.60 (1.64) | 2.88 (1.66) | 2.55 (1.82) | 3.11 (1.42) |

| Time 2 | 2.46 (1.51) | 2.28 (1.82) | 2.22 (1.88) | 2.44 (1.75) | 2.40 (1.66) | 2.15 (1.67) | 2.68 (1.92) | 2.75 (1.69) | 2.70 (1.71) | 2.77 (1.79) | 2.75 (1.90) | 3.01 (1.67) |

| Time 3 | 2.44 (1.87) | 2.24 (1.88) | 1.61 (1.95) | 2.31 (1.66) | 2.61 (1.79) | 2.33 (1.42) | 2.79 (1.92) | 2.41 (1.41) | 2.52 (1.84) | 2.79 (1.88) | 2.60 (1.77) | 2.99 (1.66) |

| Control and Wrote About Sad Event (N=24) | Control and Wrote About Anxious Event (N=24) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Counterfactual (N=8) | Subtractive Counterfactual (N=8) | No Counterfactual (N=8) | Additive Counterfactual (N=9) | Subtractive Counterfactual (N=8) | No Counterfactual (N=7) | |||||||

| Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | Sadness | Anxiety | |

| Time 1 | 1.69 (1.89) | 1.68 (1.66) | 1.42 (1.64) | 1.42 (1.91) | 1.55 (2.01) | 1.67 (1.66) | 1.28 (1.82) | 1.71 (1.59) | 1.60 (1.64) | 1.89 (1.56) | 1.53 (1.82) | 1.91 (1.42) |

| Time 2 | 1.46 (1.51) | 1.28 (1.82) | 1.52 (1.88) | 1.44 (1.75) | 1.40 (1.66) | 1.65 (1.67) | 1.27 (1.92) | 1.75 (1.69) | 1.70 (1.71) | 1.77 (1.79) | 1.31 (1.90) | 2.01 (1.67) |

| Time 3 | 1.54 (1.87) | 1.54 (1.88) | 1.39 (1.95) | 1.51 (1.66) | 1.61 (1.79) | 1.73 (1.42) | 1.19 (1.92) | 1.61 (1.41) | 1.62 (1.84) | 1.78 (1.88) | 1.61 (1.77) | 1.89 (1.66) |

Note. Means and standard deviations are presented for each participant group, mood type, and time point. Mood ratings are on a 0-5 scale with 5 being the highest. Time 1 = Baseline. Time 2 = Immediately following the counterfactual intervention. Time 3 = Following the additional writing.

We predicted that anxious individuals would experience a greater decrease in anxious mood after writing about an additive counterfactual, which is a non-fit to the motivational system that is dysfunctional for them (the prevention system), than they would after writing about a subtractive counterfactual. Likewise, we predicted that dysphoric individuals would experience a greater decrease in sad mood after writing about a subtractive counterfactual, which is a non-fit to the motivational system that is dysfunctional for them (the promotion system), than they would after writing about an additive counterfactual. To examine our hypotheses, which focused on comparative rates of change over three time points, an omnibus mixed linear model was tested with Time (baseline, post-counterfactual, post-additional writing) as a within-subject factor and Priming Condition (sad, anxious) and Counterfactual Condition (subtractive, additive, none) as between-subject factors. We observed several linear effects that were statistically significant but no statistically significant quadratic effects, so we conducted statistical tests for slope differences in linear patterns of change across the three measurement points. A significant Time X Counterfactual interaction was observed, F(2, 108) = 3.95, p < .05, η2 = .04, which was qualified by a significant Time X Priming X Counterfactual interaction, F(2, 108) = 4.98, p < .05, η2 = .06.

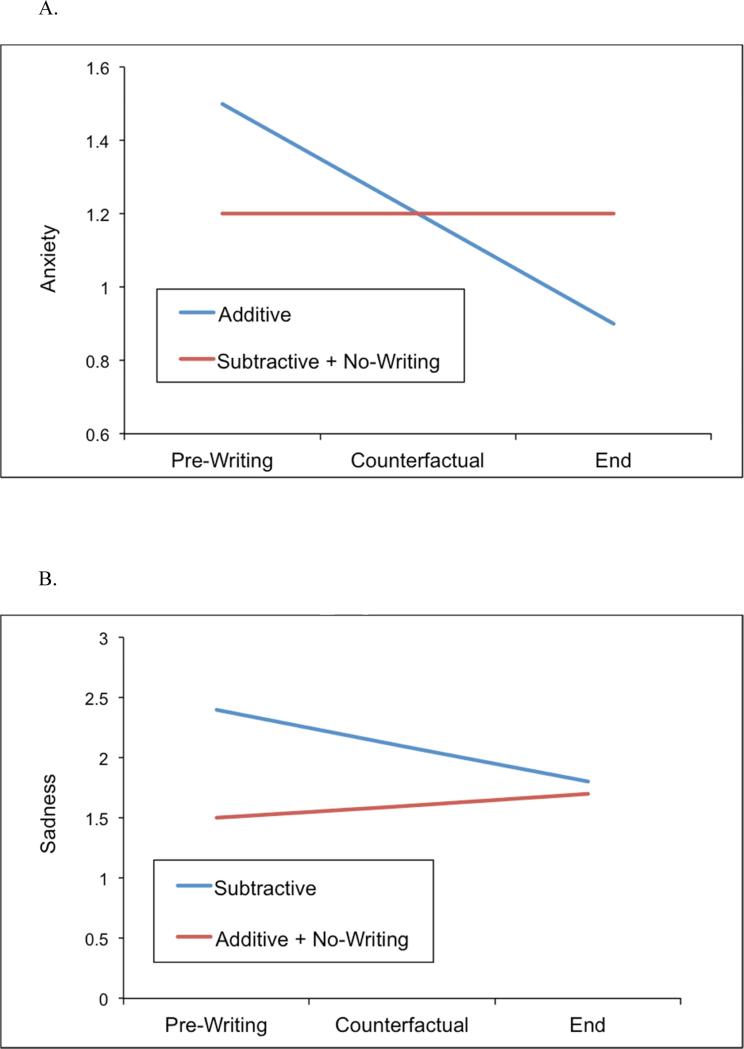

The significant three-way interaction reflected two distinct patterns of change within the groups of participants according to the type of counterfactual each was asked to generate. For the additive counterfactual condition, we observed that the anxious participants showed a significant decrease in self-reported anxious mood across the three time points, standardized slope coefficient = -.39, F(1, 108) = 5.44, p < .05, whereas neither the dysphoric (slope = -0.08) nor the control (slope = 0.04) participants manifested a significant slope coefficient for anxious mood. In contrast, for the subtractive counterfactual condition, we observed that the dysphoric participants showed a significant decrease in self-reported sad mood across the three time points, standardized slope coefficient = -.37, F(1, 108) = 5.06, p < .05, whereas neither the anxious (slope = -.05) nor the control (slope = -.06) participants manifested a significant slope coefficient for dysphoric mood. Figure 1 shows the estimated average slope of self-reported anxious mood across the three time points for the subtractive counterfactual compared with the additive counterfactual plus the no-writing conditions (Figure 1A) as well as the estimated average slope of sad mood across the three time points for the additive counterfactual compared with the subtractive counterfactual plus the no-writing conditions (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

The figures on the next page show the average slope of self-reported anxious mood change for the subtractive counterfactual compared with the additive counterfactual plus the no-writing condition (Figure 1A) as well as the average slope of sad mood change for the additive counterfactual compared with the other conditions (Figure 1B). For the additive counterfactual condition, the anxious participants showed a significant decrease in self-reported anxious mood across the three time points, t(55) = 2.19, p < .05, whereas neither the dysphoric nor the control participants manifested such a decrease (both showed no statistically significant positive or negative slope for anxious mood). In contrast, for the subtractive counterfactual condition, the dysphoric participants showed a significant decrease in self-reported sad mood across the three time points, t(55) = 2.33, p < .05, whereas neither the anxious nor the control participants manifested such a decrease (both showed no statistically significant positive or negative slope for dysphoric mood).

Individual differences in self-discrepancy and regulatory focus as moderators

Magnitude of actual:ideal and actual:ought self-discrepancy also had been assessed during the initial screening, as well as the same two measures of individual differences in regulatory system orientation as in Study 1: average response times to the “ideal self” and “ought self” questions on the Computerized Selves Questionnaire (representing a measure of the strength of promotion/prevention goal accessibility), and scores on the promotion success and prevention success scales of the Regulatory Focus Questionnaire (representing self-perceived success vs. failure in promotion or prevention goal pursuit). To determine whether individual differences in magnitude/type of self-discrepancy or in perceived regulatory system effectiveness moderated the observed association between specific interventions and change in dysphoric vs. anxious mood, we repeated the mixed linear model described above several times, each time including one of the potential moderators as both a main effect and an interaction effect (combined with Type of Intervention).

Actual:ideal and actual:ought discrepancy did not significantly predict either type of mood change as main effects or as part of an interaction effect (all ps > .15), indicating that the observed differential effects of the microinterventions were not conditional on having a lower vs. higher pre-existing level of either type of self-discrepancy. The promotion/prevention goal accessibility measures likewise did not significantly predict either type of mood change (all ps > .5), indicating that the impact of the microinterventions was not conditional on lower vs. higher chronic accessibility of an individual's promotion (ideal) or prevention (ought) goals.

However, consistent with the results of Study 1, the RFQ promotion success subscale did show a statistically significant association with mood change. Specifically, dysphoric participants who had previously reported lower levels of self-perceived success in attaining promotion goals manifested greater reduction in sad mood than participants reporting higher levels of promotion success, but only within the subtractive (non-fit) counterfactual condition, F(2, 108) = 4.52, p < .05, R2(change) = .04. Unlike Study 1, there was no comparable effect for the RFQ prevention success subscale in regard to anxious participants.

Overall, the data from Study 2 were consistent with the hypothesized mechanisms of action for counterfactual-based microinterventions derived from regulatory focus and fit theories. We had predicted that counterfactuals generated about experiences of goal pursuit failure that were a poor fit to the motivational characteristics of the regulatory system involved with the failure would have the effect of acutely reducing distress about the failure because the non-fit would reduce confidence in the failure judgment. The manipulation check and mood change data each reflected that prediction. Dysphoric participants who had been randomly assigned to write a subtractive (non-fit) counterfactual about a failure experience that had made them feel sad (“Think about what you did to deal with the problem that was a mistake. What might you have done differently?”) reported that doing so was a non-fit with their current state of mind, experienced the counterfactual generation as being effective in making them feel better, and did, indeed, reduce their dysphoric state. Similarly, anxious participants who had been randomly assigned to write an additive counterfactual about a failure experience that had made them feel nervous (“Think about what action you could have taken, what you could have done that you did not do, that would have been more successful.”) reported that doing so was a non-fit with their current state of mind, experienced the counterfactual generation as being effective in making them feel better, and did, indeed, reduce their anxious state. The data from other comparison conditions (e.g., dysphoric participants writing additive counterfactuals and anxious participants writing subtractive counterfactuals) showed no such significant effects.

General Discussion

Using regulatory focus theory and regulatory fit theory, we conducted two proof-of-concept studies of microinterventions that targeted dysphoric and anxious affective states in undergraduates who reported a range of such symptoms. Study 1 exposed participants who varied in their levels of chronic dysphoric and/or anxious mood to a one-session intervention designed to either strengthen or weaken engagement in personal goal pursuit. The participants in the experimental conditions were given a script describing a technique for dealing with adversity and were encouraged to generate examples of current problematic situations and apply the technique described in the script to those situations. They were assigned to: (a) a script that described dealing with distress by overcoming or opposing obstacles (intended to strengthen regulatory system engagement), (b) a script that described viewing the distress as an emotional nuisance (intended to weaken regulatory system engagement), (c) a combined script, or (d) an active control condition. Because dysphoria is associated with under-engagement of the promotion system whereas anxiety is associated with over-engagement of the prevention system, we predicted that dealing with distress by overcoming or opposing obstacles would be beneficial for dysphoric symptoms, as reflected in an increase in PA, whereas viewing the distress as an emotional nuisance would be beneficial for anxious symptoms, as reflected in a decrease in NA. The results supported these predictions.

Study 2 tested a microintervention based on previous findings indicating that defining goal pursuit failure as not attaining a gain is relevant to the promotion system, whereas defining failure as not avoiding a loss is relevant to the prevention system. Because it is common for individuals suffering from depression or anxiety to ruminate over past failures, this second study tested whether ruminative responses to failure could be reduced by creating regulatory non-fit for the ruminative counterfactual thinking. The specific intervention was based on prior evidence (Roese et al., 1999) that prevention failure is associated with subtractive counterfactual thinking (e.g., “What mistake did I make?”, which represents a negative act that needs to be subtracted), whereas promotion failure is associated with additive counterfactual thinking (e.g., “What did I fail to do?”, which represents a positive act that needs to be added). Given this evidence, a regulatory focus non-fit is created when anxious individuals are asked instead to use additive counterfactual thinking, and when dysphoric individuals are asked instead to use subtractive counterfactual thinking. We predicted that by inducing a specifically targeted regulatory non-fit through the mechanism of replacing the usual counterfactual responses to failure associated with anxiety or dysphoria, the intervention would decrease those specific participants’ anxious or dysphoric feelings. We assigned participants who varied in their levels of chronic dysphoric and/or anxious mood to (a) write an additive counterfactual regarding a recent failure, (b) write a subtractive counterfactual regarding a recent failure, or (c) a no writing condition. As predicted, self-reported anxiety decreased when participants used (non-fit) additive counterfactual thinking, and sadness decreased when participants used (non-fit) subtractive counterfactual thinking.

Insel (2008) observed that although psychosocial treatments often receive less attention in the popular press than pharmacological treatments, the data supporting their efficacy are frequently stronger and the conceptual links between hypothesized etiologic factors and treatment mechanisms are more straightforward. Given this insight, translating emerging knowledge in basic behavioral science into novel psychological interventions represents a high priority for enhancing public health. The general purpose of these proof-of-concept studies was to answer this call using emerging knowledge from previous investigations that tested the implications of regulatory focus theory and regulatory fit theory for motivation and affect. Our aim was not to develop a full-fledged treatment, but rather, taking an experimental medicine approach, to identify and verify targets for psychosocial intervention in analogue samples (Insel & Sahakian, 2012). A second, equally important, aim was to test how interventions based on the distinction between promotion failure and prevention failure could be used to complement existing psychosocial treatments for anxious and dysphoric states. The results suggest how microinterventions could be personalized and used to target specific symptoms. Our microinterventions were translations from basic research on self-regulatory dysfunction that are designed to target specific self-regulatory mechanisms. The microinterventions were designed to be used across diagnostic categories (i.e., targeting specific types of distress rather than overall diagnostic status) and could be disseminated efficiently to accompany existing CBT approaches (including transdiagnostic CBT protocols; e.g., Barlow et al., 2011) as well as other efficacious psychosocial treatments. In the tradition of recent transdiagnostic adaptations of CBT techniques, e.g., Perceptual Control Theory and intervention via the Method of Limits (PCT/MOL: Carey, 2011; Carey, Mansell, & Tai, 2014), our emphasis was on targeting putative mechanisms underlying distress rather than on affect or symptoms per se. In contrast to PCT/MOL and Barlow's transdiagnostic approach, our model was derived from principles of motivation and goal pursuit and stipulated that fundamental differences between promotion and prevention could be applied therapeutically and idiographically.

It should be noted that regulatory focus and regulatory fit theories, while sharing a broad social-cognitive perspective with CBT-type interventions, nonetheless are distinct in a number of respects from cognitive-behavioral conceptualizations of the etiology and treatment of internalizing symptoms. RFT distinguishes between a promotion system of self-regulation that is concerned with nurturance, advancement, and fulfilling hopes (ideals) and a prevention system that is concerned with security, safety, and fulfilling duties (oughts). In an early discussion of the role of the promotion and prevention systems in vulnerability to internalizing disorders, Strauman (2002) postulated distinctions between the promotion and prevention systems with regard to motivational impetus, affective consequences, personality correlates, neural components, socialization origins, and associations with psychopathology.

RFT also provides a framework for conceptualizing the comorbidity of dysphoric and anxious symptoms which likewise complements CBT-based models. First, it helps to understand individual variability in affective responses to similar situations. RFT predicts distinct affective consequences depending on whether a goal is construed in terms of promotion or prevention, and this framework helps determine whether an outcome is construed as a success or failure, and thus whether, and what type, of negative affect results. Second, RFT predicts that even healthy people will experience both types of distress at least occasionally, simply because a person who is dealing with life stresses and problems will at least on some occasions experience promotion failure and at least on some occasions experience prevention failure. What will vary across individuals is the relative frequency of each type of occasion, which will depend on a variety of factors, including socialization history (Klenk et al. 2011). RFT also addresses the critical question of why at any given moment a person is experiencing primarily dejection-depression or primarily agitation-anxiety. The individual's current affective state is in part a function of whether they are trying to “make good things happen” (promotion) or trying to “keep bad things from happening” (prevention), and research in social cognition indicates that both promotion and prevention focus can be situationally induced with or without the individual's awareness (Higgins, 1997). This can help to explain why an individual who typically experiences problems with dysphoric symptoms may come to experience an acute surge in anxious symptoms and vice versa. Finally, RFT also predicts comorbidity based on the dynamic reciprocal relation between the two hypothesized motivational systems: dysfunction in one system (e.g. the promotion system), which is associated with depression, can render an individual vulnerable to dysfunction in another system (e.g. the prevention system), which is associated with anxiety disorders such as GAD (Klenk et al., 2011). The fact that RFT can help to account for acute as well as chronic anxious/depressive comorbidity suggests that interventions based on RFT may be effective among individuals with both types of symptoms.

The present studies also build upon the findings from randomized clinical trials of self-system therapy (SST), the brief structured psychotherapy based on RFT which already been shown to be efficacious (Eddington et al., in press; Strauman et al., 2006). SST (Vieth et al., 2003) was designed for depressed individuals characterized by hypoactivation of the promotion system. The primary objectives of SST include education about depression, re-initiation of promotion-focused behavior, systematic self-evaluation, identifying targets for change, and using change and/or compensatory strategies to restore adaptive self-regulation. SST was hypothesized to work by altering maladaptive self-regulation, using techniques that include changing the availability and accessibility of personal goals, changing the importance and affective significance of such goals, and changing patterns of goal pursuit behavior. It was hypothesized that SST would be comparable to established treatments overall and superior efficacy for depressed individuals characterized by promotion system dysfunction. In two randomized trials (Eddington et al., in press; Strauman et al., 2006), patients with significant promotion dysfunction who received SST and patients without significant promotion dysfunction who received CT showed significantly greater improvement than patients with significant promotion dysfunction assigned to CT or patients without significant promotion dysfunction assigned to SST.

Although clinical trials are useful for establishing efficacy of treatments, they are not optimal designs either for evaluating the efficacy of specific ingredients (i.e., single interventions or what we are calling “microinterventions”) or for testing hypotheses about mechanisms of action. The present studies used an experimental, one-session design to test two RFT-derived interventions on a “micro” level (Lutz et al., 2005) as well as to examine how acute changes in mood were attained. Our intent was that the microinterventions tested in the present studies would be designed to impact self-regulatory function among a much broader population than the techniques that were part of SST, which were designed to intervene at a level of self-regulatory dysfunction that is only thought to characterize a subset of depressed individuals. We view the present findings as initial evidence that brief targeted psychosocial interventions designed to impact self-regulation are feasible and efficacious.

The limitations of the present studies should be acknowledged. Each study was based on an analogue sample of undergraduates, primarily because our intent was to obtain proof-of-concept as an initial step in the development of the self-regulatory microinterventions. Although experimental medicine approaches are consistent with a analogue-first research strategy, the findings will need to be replicated and ultimately extended to clinical samples in order to better evaluate the potential utility of the microinterventions. Also, the studies focused exclusively on acute (and likely transitory) changes in affective state and symptomatology, again based on the strategy of proof-of-concept. It will require additional research to determine whether the microinterventions, when used regularly, can provide reliable and clinically significant reduction in distress. In addition, the studies relied exclusively on self-report assessment of distress, which should be expanded upon in subsequent investigations. Nonetheless, the findings were consistent with our theory-based predictions, and represent an initial step toward expanding the cognitive-behavioral armamentarium for dealing with dysphoric and anxious states.

Highlights.

We present two studies based on regulatory focus and fit theory testing new interventions for anxiety and depression.

One new intervention involved altering strength of engagement in goal pursuit to create a temporary “lack of fit”.

The other intervention involved using positive vs. negative counterfactuals, again to create a “lack of fit”.

The “lack of fit”, in turn, changes the individual's motivational state and reduces distress associated with perceived failure.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was supported by Grant R01 MH039429 from the National Institute of Mental Health. This research also was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grants P30 DA023026 and R01 DA031579, which is supported by the NIH Common Fund and managed by the OD/Office of Strategic Coordination (OSC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Copies of the intervention scripts are available from the authors upon request.

There were no statistically significant differences among the four interventions conditions on the credibility items, with each condition manifesting an average score between “credible” and “very credible”.

References

- Andersen SM, Baum A. Transference in interpersonal relations: Inferences and affect based on significant-other representations. Journal of Personality. 1994;62(4):459–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson JW. An Introduction to Motivation. Van Nostrand; Oxford, England: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. The unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–63. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Alcaine O, Behar E. Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS, editors. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice. Guilford Press; New York: 2004. pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- Brodscholl JC, Kober H, Higgins ET. Strategies of self-regulation in goal attainment versus goal maintenance. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2007;37(4):628–648. [Google Scholar]

- Carey TA. Exposure and reorganization: The what and how of effective psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:236–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey TA, Mansell W, Tai SJ. A biopsychosocial model based on negative feedback and control. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00094. Article 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RM, Wittchen H, Pfister H, Kessler RC. One-year prevalence of subthreshold and threshold DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. Depression And Anxiety. 2001;13(2):78–88. doi: 10.1002/da.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J, Grant H, Higgins ET. Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “Feeling Right”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86(3):388–404. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue R,A, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:491–569. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS, Breiter HJ. Cognitive assessment of depression: Reliability and validity of three measures. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92(1):107–109. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DA, Seeds PM, Collins KA. Transdiagnostic approaches to the prevention of depression and anxiety. Journal Of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23(1):44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Elliot AJ, Sheldon KM. Avoidance personal goals and the personality-illness relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;75(5):1282–1299. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Rankin MA, Wright EC, Alpert JE, Nierenberg AA, Pava J, Rosenbaum JF. Anxiety disorders in major depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(00)90140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Row Peterson; Evanston, IL: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Washington Square Press; New York: 1952. (Original work published 1920) [Google Scholar]

- Fydrich T, Dowdall D, Chambliss DL. Reliability and validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfried MR. The future of psychotherapy integration: Closing the gap between research and practice. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2010;20(4):386–396. [Google Scholar]

- Grawe K. Neuropsychotherapy: Towards a neuroscientifically informed psychotherapy. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety: An Inquiry Into the Functions of the Septo-Hippocampal System. Oxford Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood T, Pratt D, Beutler LE, Bongar BM, Lenore S, Forrester BT. Technology, telehealth, treatment enhancement, and selection. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011;42:448–454. doi:10.1037/a0026214. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD, Waternaux C. Sample size estimation for longitudinal designs with attrition: Comparing time-related contrasts between groups. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Heider F. The Psychopathology of Interpersonal Relations. Wiley; New York: 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist. 1997;52:1280–1300. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.12.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review. 1987;94(3):319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 30. Academic Press; New York: 1998. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Promotion and prevention experiences: Relating emotions to nonemotional motivational states. In: Forgas JP, editor. Handbook of affect and social cognition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, New Jersey: 2001. pp. 186–211. [Google Scholar]