Abstract

We systematically reviewed evidence of disparities in tobacco marketing at tobacco retailers by sociodemographic neighborhood characteristics. We identified 43 relevant articles from 893 results of a systematic search in 10 databases updated May 28, 2014. We found 148 associations of marketing (price, placement, promotion, or product availability) with a neighborhood demographic of interest (socioeconomic disadvantage, race, ethnicity, and urbanicity).

Neighborhoods with lower income have more tobacco marketing. There is more menthol marketing targeting urban neighborhoods and neighborhoods with more Black residents. Smokeless tobacco products are targeted more toward rural neighborhoods and neighborhoods with more White residents. Differences in store type partially explain these disparities.

There are more inducements to start and continue smoking in lower-income neighborhoods and in neighborhoods with more Black residents. Retailer marketing may contribute to disparities in tobacco use. Clinicians should be aware of the pervasiveness of these environmental cues.

Tobacco products and their marketing materials are ubiquitous in US retailers from pharmacies to corner stores.1 A similar presence is found across the globe, except in countries that ban point-of-sale (POS) tobacco marketing (e.g., Australia, Canada, Thailand2). In the United States, the POS has become the main communications channel for tobacco marketing3,4 and is reported as a source of exposure to tobacco marketing by more than 75% of US youths.5 Burgeoning evidence6,7 suggests that marketing at the POS is associated with youths’ brand preference,8 smoking initiation,9 impulse purchases,10,11 and compromised quit attempts.12,13

The marketing of tobacco products is not uniform; it is clear from industry documents that the tobacco industry has calibrated its marketing to target specific demographic groups defined by race,14 ethnicity,15 income,16 mental health status,17 gender,18,19 and sexual orientation.20 Framed as an issue of social and environmental justice,14 research has documented historical racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the presence of tobacco billboards,21–25 racial disparities in total tobacco marketing volume,24 and targeting of menthol cigarettes to communities with more Black residents.25,26 Targeted marketing of a consumer product that kills up to half27 of its users when used as directed exacerbates inequities in morbidity and mortality. Smoking is estimated to be responsible for close to half of the difference in mortality between men in the lowest and highest socioeconomic groups.28 However, evidence of marketing disparities is scattered across multiple disciplines and marketing outcomes, such as product availability, advertising quantity, presence of promotional discounts, and price. A synthesis of this literature would provide valuable information for intervention on tobacco marketing in the retail environment and inform etiological research on health disparities.

To address this gap in the literature, we systematically reviewed observational studies that examined the presence and quantity of POS tobacco marketing to determine the extent to which marketing disparities exist by neighborhood demographic characteristic (i.e., socioeconomic disadvantage, race, ethnicity, and urbanicity).

METHODS

We followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) systematic review guidelines for observational studies29 by iteratively developing a series of keywords in 4 domains: tobacco, marketing, disparity, and retail environment. Using PubMed, we added controlled vocabulary terms (i.e., Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] terms) to our search (see the box on the following page).

Final PubMed Search Terms

((tobacco products[MeSH] OR tobacco[tiab] OR tobacco industry[MeSH] OR (smoking[MeSH] NOT marijuana smoking[MeSH]) OR smoking[tiab] OR cigarette[tiab] OR cigarettes[tiab] OR cigar[tiab] OR cigars[tiab] OR cigarillo[tiab] OR cigarillos[tiab]) AND (marketing[MeSH] OR marketing[tiab] OR advertising[tiab] OR advert[tiab] OR adverts[tiab] OR promotion[tiab] OR promotions[tiab] OR ads[tiab] OR commerce[MeSH] OR price[tiab] OR placement[tiab] OR positioning[tiab] OR product[tiab] OR signs[tiab] OR signboard[tiab] OR signboards[tiab] OR discounts[tiab] OR “functional items”[tiab] OR signage[tiab] OR display[tiab] OR displays[tiab] OR “single cigarette”[tiab] OR “single cigarettes”[tiab] OR loosies[tiab]) AND (socioeconomic factors[MeSH] OR disparity[tiab] OR disparities[tiab] OR health status disparities[MeSH] OR inequality[tiab] OR inequalities[tiab] OR equity[tiab] OR inequity[tiab] OR inequities[tiab] OR targeting[tiab] OR target[tiab] OR targets[tiab] OR neighbourhood[tiab] OR neighbourhoods[tiab] OR neighborhood[tiab] OR neighborhoods[tiab] OR residence characteristics[MeSH] OR “residence characteristics”[tiab] OR contrasting[tiab] OR community[tiab] OR communities[tiab] OR (black[tiab] NOT “black market”[tiab]) OR “african american”[tiab] OR latino[tiab] OR latina[tiab] OR latinos[tiab] OR hispanic[tiab] OR hispanics[tiab] OR asia[tiab] OR asian[tiab]) AND (store[tiab] OR stores[tiab] OR “point of sale”[tiab] OR “points of sale”[tiab] OR retail[tiab] OR retailers[tiab] OR retailer[tiab] OR retailing[tiab] OR shop[tiab] OR “gas station”[tiab] OR “gas stations”[tiab] OR “point of purchase”[tiab] OR “points of purchase”[tiab] OR outlet[tiab] OR outlets[tiab] OR “milk bars”[tiab] OR newsstands[tiab] OR kiosk[tiab] OR petrol[tiab] OR garage[tiab] OR garages[tiab] OR “service station”[tiab] OR “service stations”[tiab] OR pharmacy[tiab] OR pharmacies[tiab] OR druggist[tiab] OR druggists[tiab] OR supermarket[tiab] OR supermarkets[tiab] OR grocers[tiab] OR groceries[tiab] OR hypermarket[tiab] OR hypermarkets[tiab] OR vendor[tiab] OR vendors[tiab] OR vending[tiab])).

Once our search resulted in no new relevant articles, we translated our controlled vocabulary terms into the controlled vocabulary of other databases (Appendix A, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org). Thus, we searched each database using the indexing terms indigenous to that database as well as our standard keywords. We implemented our search on July 18 and 19, 2013, and updated it on May 28, 2014, in 10 databases: Academic Source Complete, Business Source Complete, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Communications and Mass Media Complete, PsycINFO via EBSCO, Embase, GEOBASE, ISI Web of Knowledge, PubMed, and Scopus. We used no date, language, or geographic restrictions in our search.

Inclusion Coding of Records

We use “record” to indicate a published article identified in our search. “Study” indicates a research project from which multiple published articles may have been published. “Results” are the reported findings contained with published records. We sought to identify records in which disparities in tobacco marketing were assessed through observational data collection at retail locations. We defined disparities to include differences in tobacco marketing by income or other measures of socioeconomic disadvantage, by race (Asian, African American/Black), by ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino), and by urbanicity. We defined marketing to include price (e.g., advertised price, price discounts, or price promotions), promotion (e.g., branded advertisements and displays), placement (e.g., at child height, location near register), and product characteristics (e.g., unit size, single cigarettes, flavor): the 4 P’s of marketing.30

Marketing could be indoors or outdoors as long as it was assessed at a retail location (e.g., shop, street vendor, snack bar, pharmacy). However, we a priori determined to exclude records reporting solely the availability of cigarettes. Tobacco products included cigarettes, cigars, little cigars, snus, smokeless tobacco, e-cigarettes, and other products derived from tobacco. Two coders (J. G. L. L., S. W. R., and 2 graduate research assistants) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of records identified in the search for inclusion or exclusion. We reconciled differences by discussing them.

Data Abstraction

Following an abstraction protocol, 2 coders (J. G. L. L., S. W. R., and a graduate research assistant) independently abstracted each included study’s characteristics into online survey software. J. G. L. L. then merged them into an evidence table (Appendix B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Where bivariate associations could not be computed from the published data, we requested a correlation matrix from the corresponding author for studies published in the past 10 years. We coded results so that a positive sign indicated the presence of a hypothesized disparity.

Inclusion of Results

We included results in a 2-step process (shown in Figure 1): a narrative synthesis and assessment of statistical tests.

FIGURE 1—

PRISMA flow diagram of inclusion of studies and results.

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

We included all records reporting any findings, including qualitative, that involved visiting tobacco retailers and that assessed neighborhood disparities in tobacco marketing in the evidence table for narrative review.

For each record, we identified all results with a statistical test of association between the neighborhood characteristics of socioeconomic disadvantage, race, ethnicity, or urbanicity and any measure of marketing. In this stage, we excluded results for the following reasons:

effect sizes were for change over time;

area units were at the county level or larger (these are subject to the modifiable area unit problem31);

analyses were reported for “other” race because of category heterogeneity;

in the case of single cigarette sales, measures were based solely32,33 on retailer advertising of sales (e.g., “loosies: 35¢”; because advertisement of an illegal practice may not be a valid measure34); and

evidence was limited or insufficient to hypothesize marketing toward more vulnerable populations.

E-cigarettes,35 potentially reduced exposure products, and premium cigars may be targeted to less vulnerable populations and would thus attenuate evidence of targeting more disadvantaged and more diverse communities.

After these exclusions, we graphed results to depict the distribution of direction of associations.

Analysis

We stratified all analyses by neighborhood demographics: socioeconomic disadvantage, race (African American/Black, Asian), ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino), minority status (“minority status” is used by the original authors, often to indicate non-White, non-Hispanic status or being left undefined), and urbanicity. We also stratified results specific to menthol marketing, smokeless marketing, and little cigar or cigarillo marketing, as differences between groups targeted could attenuate the relationship. We conducted data management in SPSS version 22 (IBM, Chicago, IL). Meta-analysis of common measures was not possible because of the limited number of available effect sizes with common measures of neighborhood characteristics and outcomes. The evidence table (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) reports bivariate associations of marketing with neighborhood characteristics. Where both bivariate and adjusted results were reported, we chose to emphasize bivariate relations because a diversity of model covariates limited the comparability of adjusted results.

Systematic reviewers are challenged by how to weight the evidence on the basis of studies’ risk of bias in narrative reviews.36 To identify the strongest, most generalizable evidence for emphasis in the narrative review, we created an index of study characteristics, giving 1 point for

having more than 10 neighborhoods (for the studies not reporting the number of area units used, we gave a point if the number of retailers audited would average more than 10 per area unit at the 10-area-unit cutoff (i.e., the ratio of retailers to neighborhoods was greater than 10 to 1 if we assumed 10 neighborhoods),

having more than 100 retailers,

addressing spatial dependence,

using probability-based sampling of neighborhoods, and

using probability-based sampling of retailers.

One study scored zero, 8 scored 1, 8 scored 2, 5 scored 3, and the remaining 21 scored 4 or 5. We correlated the index with the year of publication (rs(n = 43) = 0.45; P < .01), suggesting improvements in studies over time. Although all studies are reported in the evidence table (Appendix B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org), we focused our narrative description on results from the 21 studies with an index value of 4 or 5.

RESULTS

There were 43 records from 8 countries that met the inclusion criteria: 33 from the United States,26,32,33,37–66 5 from Australia,67–71 and 1 each from Canada,72 Guatemala and Argentina,73 India,74 New Zealand,75 and the United Kingdom.76 The first study was published in 1989,40 and through 2013 (the last full year of data) there was a significant increase in publications per year (rs(n = 17) = 0.72; P < .01). From these, we identified 284 study results of which 148 included information on significance and direction of association. An evidence table is available online (Appendix B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Common Outcome Measures

Among the 43 records, 28 reported on promotions, including measures of the presence of any tobacco marketing on the exterior of stores, an index of tobacco marketing materials, and counts of marketing per square mile. Seventeen reported on price, including the presence of price discounts, advertised prices, and purchase prices. Sixteen reported on product characteristics, including single cigarettes and types of smokeless tobacco.

Twelve reported on placement of marketing, including prominent display of tobacco ads at the POS and products near candy. Seven additionally reported on compliance with marketing regulations.32,33,37,49,50,71,75 More detail is presented in the evidence table (Appendix B, available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Level of Analysis and Sample Size

Most studies analyzed results at the store level; however, 1 study analyzed some outcomes at the advertisement level (i.e., each ad was a case in the analysis, which looked at differences in advertisement characteristics by neighborhood),58 and 4 studies analyzed outcomes at the neighborhood level, deriving mean values,40 aggregating marketing up to marketing per square mile,59 calculating individual brands’ share of all ads,56 and providing total counts of ads in neighborhoods.38

Of the 32 studies that reported the number of area units (i.e., neighborhoods as defined by the study) excluding 1 study using store-centered buffers,39 the average was 89 (SD = 134; median = 36; range = 2–624). Of the 39 studies that reported the number of retailer audits conducted, the average was 425 (SD = 671; median = 240; range = 23–3989).

Area Units

Although census tracts (or equivalents) were the most common choice (n = 13 studies), many other area units were used to describe neighborhood demographics, including school neighborhoods (variously defined; n = 6), census block groups or equivalent (n = 5), and postal codes (n = 3).

Sixteen studies used other approaches, including business districts,38,52 buffering around observed retailers and averaging census block group characteristics,39 using a 1-mile radius from a youths-serving organization,44 combining postcodes on the basis of informant knowledge,33 and creating spatial units that were unique to the study.61

Statistical Approaches

Neighboring tobacco retailers may share similarities (i.e., spatial autocorrelation may be present), causing the collected data to violate assumptions of independence in standard statistical tests.31 Of the 5 articles53–55,63,64 that reported intraclass correlations for measures of marketing, the intraclass correlations ranged from 0.025 for retailers’ number of smokeless tobacco ads in census block groups in a Midwestern US city63 to 0.36 for the proportion of menthol marketing at retailers in census tracts in St. Louis, Missouri.55 Eight studies addressed this issue by using mixed models, usually multilevel models or generalized estimating equations.26,41,43,53–55,61,72 Another 4 studies corrected for dependence using robust SEs.32,63,64,67 One article aggregated marketing to the census tract (index value per square mile) and found no significant spatial autocorrelation as indicated by Moran’s I and Geary’s c.59 However, the majority of research (70%) did not comment on the issue of spatial autocorrelation.

Twelve records sampled retailers to have maximally contrasting groups. Four records compared extremes within their analysis. Although sampling designed to produce more extreme comparisons can inform etiological research, these strategies limit generalizability across neighborhoods. Fifty-eight percent of records dichotomized or otherwise categorized (e.g., median and mean split, tertiles or quintiles) demographic correlates and marketing outcomes that were originally continuous measures. Such categorization can reduce power to detect an effect.77

Evidence of Disparities in Point-of-Sale Marketing

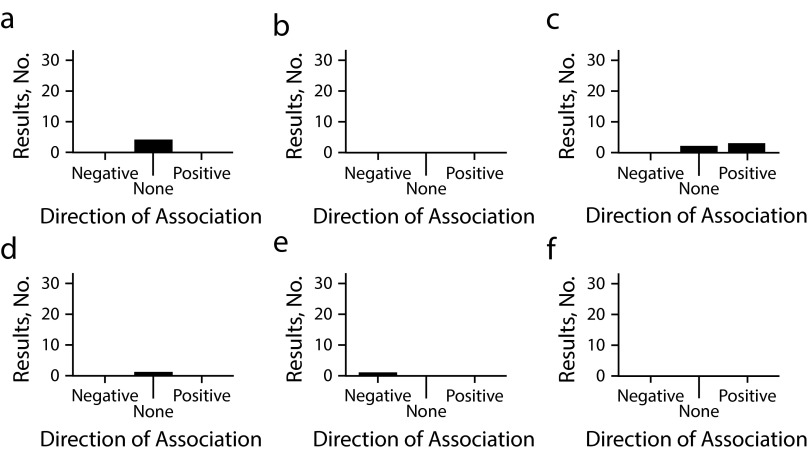

Figures 2 through 5 show the count of results that showed a negative association, no association, or a positive association between neighborhood characteristics and POS marketing for tobacco products generally (including studies that are specific to cigarettes only), menthol-specific marketing, smokeless-specific marketing, and little cigars- and cigarillos-specific marketing. Figure 2a shows that a major area of research focus has been on socioeconomic disadvantage and indicates that a preponderance of evidence shows a positive association between socioeconomic disadvantage and POS tobacco marketing. By contrast, Figure 2f shows that we found no evidence of overall POS tobacco marketing disparities by urbanicity, excluding menthol-, smokeless-, and cigar-specific marketing. Figure 2 illustrates how there are very few negative associations between the neighborhood characteristics and POS tobacco marketing. In Figure 3c, we identified evidence of only a positive association between greater numbers of Black neighborhood residents and POS menthol marketing.

FIGURE 2—

Count of results for general tobacco marketing by direction of association and neighborhood characteristics of (a) socioeconomic disadvantage, (b) Asian American race, (c) Black race, (d) Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, (e) minority status, and (f) urbanicity: May 28, 2014.

FIGURE 3—

Count of results for menthol-specific marketing by direction of association and neighborhood characteristics of (a) socioeconomic disadvantage, (b) Asian American race, (c) Black race, (d) Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, (e) minority status, and (f) urbanicity: May 28, 2014.

FIGURE 4—

Count of results for smokeless tobacco–specific marketing by direction of association and neighborhood characteristics of (a) socioeconomic disadvantage, (b) Asian American race, (c) Black race, (d) Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, (e) minority status, and (f) urbanicity: May 28, 2014.

FIGURE 5—

Count of results for cigar-specific marketing by direction of association and neighborhood characteristics of (a) socioeconomic disadvantage, (b) Asian American race, (c) Black race, (d) Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, (e) minority status, and (f) urbanicity: May 28, 2014.

Although exploratory research has clearly documented differences in tobacco marketing between very different neighborhoods in single cities,38,52,56,58,65,66,74 we focused our narrative on larger studies that used probability sampling or addressed spatial dependence (i.e., those scoring 4 or 5 on our 5-point index of study characteristics).

Evidence of Disparities by Socioeconomic Disadvantage

Of the 43 records, 29 examined differences in marketing by neighborhood income or any other indicator of socioeconomic disadvantage.26,32,33,37–39,42–44,47,51–53,56,58,59,62–64,67–76 Of these, 12 scored high in our study-characteristic index.26,32,33,39,47,54,59,63,64,67,72,75 Across these studies, there was a clear pattern of targeted marketing in more disadvantaged neighborhoods. Menthol marketing also shows evidence of a disproportionate presence in more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. We identified no evidence of disparities in smokeless or little cigars.

Seven studies showed greater marketing in areas of more socioeconomic disadvantage. In New South Wales, Australia, a higher postcode quartile of socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with lower cigarette prices.67 In a study of 20 Canadian cities, results from mixed modeling found that median household income was inversely related to an index of marketing after controlling for city, neighborhood, and retailer characteristics; the unadjusted association was marginally significant.72 In Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, greater census block group socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with more menthol and exterior advertisements but not with other indicators of marketing, such as total advertisements.64 In 14 neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio, placement of products and total number of ads were not significantly different between high and low socioeconomic deprivation neighborhoods; however, there were more exterior ads on average in neighborhoods with more socioeconomic disadvantage than in those with less disadvantage.33 In Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, lower quartiles of income and education were associated with greater tobacco marketing.47 In Omaha, Nebraska, lower tract median income was associated with more logged marketing materials per square mile after control for percentage male, number of small stores, and outlet density; the unadjusted association was also positive (personal e-mail communication from Mohammad Siahpush, April 21, 2014).59

Some results did not show disparities by socioeconomic disadvantage. In a study of New York City pharmacies,39 neighborhood educational attainment was not associated with marketing, but neighborhoods above median income were more likely than were those below median income to advertise cigarettes. The authors attributed this difference to a greater presence of chain pharmacies in richer neighborhoods; chain pharmacies were more likely to advertise tobacco products than were independent pharmacies.39 In the Wellington area of New Zealand, stores’ presence in the lowest 4 compared with the highest 3 deciles of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was not associated with the placement of tobacco products near children’s products nor with visibility of tobacco products from outside the store (both of which are banned).75

Regarding specific characteristics of marketing, no relationship was found between socioeconomic disadvantage and the presence of cigars, little cigars, and cigarillos at the block group level in 50 California cities.54 In Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, greater census block group socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with smokeless marketing using measures of census block group proportion of residents on public assistance but not with residents under the poverty line.63 In 14 neighborhoods in Columbus, Ohio, counts of smokeless advertisements were not significantly different between high and low socioeconomic deprivation neighborhoods.33 In 3 North Carolina counties, a greater proportion of families living under the poverty line was associated with the likelihood of the presence of a violation of US Food and Drug Administration tobacco advertising and labeling regulations, controlling for county, store type, and other census tract characteristics.32 In 91 California school neighborhoods, the percentage of students participating in the school lunch program was associated with a smaller proportion of menthol advertising at retailers after control for store type, school demographics, and school neighborhood characteristics.26

Evidence of Disparities in the United States

By Black race.

Of the 33 studies from the United States, 19 reported on Black race.26,32,39,41,44,46,48–50,52,54–55,59,62–66 Of these, 10 scored high on our study characteristics index.26,32,39,41,48,54,55,59,63,64 Evidence suggested disproportionate POS marketing neighborhoods with more Black residents. Evidence of greater menthol marketing is unequivocal, and there is evidence of a disproportionate presence of little cigar and cigarillos marketing. Smokeless tobacco marketing may be targeted at neighborhoods with fewer Black residents.

It is of note that the majority of the evidence scoring high in our study characteristics index addresses menthol marketing but not overall marketing for neighborhoods with more Black residents. Only 1 record reporting a significant association of overall marketing scored high in our study characteristics index: in Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, across numerous different marketing outcomes, there was a general pattern of greater tobacco marketing at retailers in census block groups with more Black residents.64

There are unequivocal disparities in menthol marketing; the evidence consistently showed greater menthol marketing in more neighborhoods with more Black residents. In St. Louis, Missouri, using mixed models, census tract percentage Black and the percentage of Black children were significantly associated with measures of menthol marketing near candy and the proportion of menthol marketing overall.55 In 91 California school neighborhoods, using mixed models controlling for school neighborhood characteristics, school demographics, store type, and store density, the percentage of enrolled Black students was associated with lower mentholated Newport cigarette prices and greater volume of menthol marketing. Unadjusted results were not available. This result was not found for other racial/ethnic groups or for nonmenthol products.26 In Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, the percentage of Black residents in census block groups was associated with the number of menthol ads at retailers.64

Less evidence was available regarding little cigars, cigarillos, and smokeless tobacco marketing. Two analyses of the same study of tobacco retailers in Washington, DC, show significant associations between little cigars and cigarillos marketing and an increasing proportion of Black residents.41,48 In 50 California cities, adjusted models found no relationship between Black race and the presence of little cigars, cigars, and cigarillos, controlling for city marijuana use prevalence, city marijuana dispensary policy, city density of marijuana dispensaries, store type, store’s block group population density, store’s block group proportion of minors, store’s block group proportion of Whites and Hispanics, and store’s block group socioeconomic status54; however, unadjusted correlations from the author showed a significant relationship (personal e-mail communication from Sharon Lipperman-Kreda, June 16, 2014).

Not all study results showed relationships between the proportion of Black residents and tobacco marketing. In Omaha, Nebraska, the logged amount of marketing per square mile was not associated with the percentage of Black residents, controlling for percentage male, number of small stores, and outlet density59; however, the unadjusted correlation from the author was positive (r(n = 84) = 0.08; personal e-mail communication from Mohammad Siahpush, April 21, 2014). No relationship between the presence of marketing in New York City pharmacies and Black race in averaged census blocks with centroids within a half mile of the pharmacy was found.39 The percentage of Black residents in census block groups was negatively associated with total smokeless tobacco advertising in retailers in the Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, area.63 In 3 North Carolina counties, the likelihood of a violation of the US Food and Drug Administration’s tobacco advertising and labeling regulations was lower for neighborhoods with more Black residents, controlling for store type and other neighborhood characteristics. Control for county caused this relationship to become nonsignificant.32

By Asian American race.

Of the 33 studies from the United States, 6 reported by neighborhood Asian composition.26,45–46,63–65 Of these, 3 scored high on our index of study characteristics.26,63,64 These studies show limited evidence for targeted overall marketing and menthol disparities. These studies included no evidence to suggest disproportionate marketing for smokeless tobacco or little cigars.

The percentage of Asian American residents in census block groups showed some positive associations across a wide variety of marketing outcomes among retailers in Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, including count of menthol ads.64 In the same study, the percentage of Asian American residents in census block groups was negatively associated with total smokeless tobacco advertising in retailers.63 In a study of 91 California school neighborhoods, Asian student enrollment was not associated with Newport price, menthol share of marketing, or Marlboro price after controlling for school and neighborhood characteristics; unadjusted results were not available.26

By minority status.

Of the 33 studies from the United States, 14 reported by minority status (operationalized as non-White, non-Hispanic or not defined).38,42,45,46,47,49,50,52,54,56,58,61,63,64 Of these, 5 scored high on our index of study characteristics.47,54,61,63,64 The general pattern of results suggests that greater overall marketing, more menthol marketing, and less smokeless tobacco marketing were associated with a greater proportion of minority residents. Of these, the evidence largely focused on overall marketing. In Oklahoma County, Oklahoma, neighborhoods in higher quartiles of percentage minority population were more likely to have a greater amount of tobacco marketing.47 In Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, smokeless tobacco marketing was generally patterned to be more present in areas with more White residents and less present in areas with more non-White residents,63 and there were more exterior ads and more menthol ads as the proportion of non-White residents increased.64

In the Minneapolis–St. Paul metro area, discount and premium cigarettes were significantly more expensive in areas with more minority residents, whereas menthol cigarettes were not more expensive in these neighborhoods.61 In 50 California cities, the presence of small cigars, cigars, and cigarillos was negatively associated with the percentage of non-White residents after controlling for marijuana policies and characteristics at the city level and neighborhood demographics; unadjusted correlations were marginally significant and positive (personal e-mail communication from Sharon Lipperman-Kreda, June 16, 2014).54

By Hispanic/Latino ethnicity.

Of the 33 studies from the United States, 13 studies reported on Hispanic/Latino ethnicity.26,32,39,44,45,50,52,54,56,59,63–65 Of these, 7 scored high on our index of study characteristics.26,32,39,54,59,63,64

No relationship between marketing and Latino ethnicity was identified in New York City pharmacies39; California school neighborhoods (for menthol share, Marlboro price, and Newport price after control for neighborhood, school, and store characteristics)26; Omaha, Nebraska census tracts (for logged marketing materials per square mile after control for percentage male, number of small stores, and outlet density)59; Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota census block groups (for smokeless and nonsmokeless marketing)63,64; or North Carolina census tracts (for US Food and Drug Administration violations after control for store, tract characteristics, and county).32 In a study of 50 California cities, Latino ethnicity was negatively associated with the presence of little cigars, cigars, and cigarillos in unadjusted correlations from the author (personal e-mail communication from Sharon Lipperman-Kreda, June 16, 2014).54

Disproportionate Tobacco Marketing by Urbanicity

Seven records reported on urbanicity.57,60,63,64,67,75 Of these, 4 scored high on our index of study characteristics.63,64,67,75 The limited evidence was consistent with targeting smokeless tobacco marketing to more rural areas and menthol-specific marketing to more urban areas. In Ramsey and Dakota counties, Minnesota, retailer location in suburban block groups was associated with fewer menthol ads but not with other types of marketing.63,64

Using a 3-level measure of remoteness in New South Wales, Australia, retailers’ remoteness was not associated with cigarette prices.67 In the Wellington area of New Zealand, urbanicity was not related to retailer compliance with POS tobacco display bans.75

Influence of Neighborhood Composition of Retailer Types

Previous research shows that the composition of retailers differs by neighborhood characteristics, with more small, nonchain retailers in more urban areas.78,79

The differences identified can be partially, but in most cases not fully, explained by different composition of retailer types in neighborhoods. When studies controlled for store type, the identified disparities persisted.26,39,40,54,55,59,61,64,66,68,72

DISCUSSION

Across study locations and measures of tobacco marketing, there are differences in tobacco marketing at the POS by neighborhood demographics. The pattern of study results suggests that increasing proportions of low-income and Black residents in neighborhoods are associated with more tobacco marketing generally and more menthol marketing, specifically. We found that in the available evidence the proportion of Latino residents in neighborhoods was not typically associated with the amount of marketing in neighborhoods. Smokeless tobacco marketing appears to be targeted to more White, rural areas. Menthol marketing is starkly more present in neighborhoods with more Black residents and in more urban neighborhoods. Evidence suggests little cigars may be more marketed at the POS in neighborhoods with more Black residents than in other neighborhoods. Neighborhoods differ in the amount and type of tobacco marketing: there are more inducements to start and continue smoking in lower-income neighborhoods and in neighborhoods with more Black residents. Retailer marketing may be contributing to disparities in tobacco use. Clinicians should be aware that environmental cues to continue smoking are more pervasive in lower-income neighborhoods and in neighborhoods with more Black residents.

Although the tobacco industry’s use of market segmentation and targeting is likely a major factor, there may be important unmeasured neighborhood characteristics that are moderators of neighborhood tobacco marketing. These may include neighborhood characteristics that are amenable to intervention,80 such as ordinances limiting marketing in retailer windows or other licensing, zoning, or minimum price policies.81,82

Researchers have not typically presented meta-analyzable results in this field, despite their importance to the broader field of tobacco control. Many otherwise compelling findings are not comparable because of the sampling and analytic strategies used. More sophisticated mixed modeling, although it addresses important issues of dependence, produces results from which effect sizes cannot be calculated directly. This is a challenge for this and future systematic syntheses of the evidence.

Tobacco Industry Geodemographic Targeting

Market segmentation and targeting are normative business practices.83 Geodemographic targeting (i.e., targeting by demographic profiles of people living within an area)84 has become a routine business strategy as data sources and geospatial computing have become available.85,86 Tobacco industry documents show attention to developing algorithms to target in-store marketing by area demographics. Brown & Williamson documents express enthusiasm for the potential of marketing segmentation by retailer and noted segmentation’s use for “ensuring that product displays and signage are used in the right stores, feature the right products, and are seen by the right consumers.”87 Philip Morris documents show customized presentations to convenience store chains on the basis of an “Integrated Retail Demographic Database Micro-Marketing Tool” that incorporated store-area data on smokers, census demographics, periodical subscriptions, lifestyles, and retail pricing data.88

Philip Morris documents note how micromarketing allowed the company to selectively implement “price promotion based on local market demographics”89 and listed stores by neighborhood profile from a commercial geodemographic classification system, PRIZM.89 In a 1997 document, Philip Morris listed 50 neighborhood demographic profiles and noted that profiles were predominantly influenced by age, ethnicity, education, income, marital status, urbanicity, family, employment, occupation, persons in household, and home ownership.90 Figure 6 shows a slide from a Philip Morris USA presentation.91 It is likely that these geodemographic targeting approaches have become more sophisticated over time.

FIGURE 6—

Slide from Philip Morris USA Integrated Retail Demographic Database presentation.

Strengths and Weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of neighborhood tobacco marketing disparities to examine multiple demographic groups. One previous meta-analysis compared Black versus White neighborhoods.24 It is likely that there are thresholds and nonlinear relationships between demographic and marketing variables. Future studies should attempt to identify if there are particular levels of poverty or proportions of racial/ethnic populations that are most relevant.

The demographic characteristics of neighborhoods are not independent of one another and are sometimes very highly correlated. This is particularly true for socioeconomic disadvantage and the proportion of Black residents in many US locations because of patterns of segregation and racism. However, studies with multivariable or multilevel models suggest that these neighborhood factors explain unique sources of variation in the prevalence of retail tobacco marketing.26,54,55,59,61,72

Policy Implications

Recent work in tobacco prevention and control has provided burgeoning evidence that many evidence-based interventions may exacerbate disparities while improving population health,92–95 a concept termed the “inequality paradox.”96

Besides higher product prices,93 regulation of the retail environment97 has the potential to have a pro-equity effect98 because of the existing disparities we identified. So, too, do community efforts to reduce tobacco marketing at the POS.99 But, this requires confirmation. There are multiple strategies for regulating tobacco marketing at POS97 and emerging strategies for ensuring minimum prices.82

Unanswered Questions and Future Research

The origins of the identified disparities cannot be disentangled from the existing cross-sectional data. Two possible sources may be particularly likely. First, the tobacco industry uses geodemographic targeting to segment marketing. Second, social structures and processes may influence the types and numbers of tobacco retailers in neighborhoods.

Although the composition of retailer types may explain some of the disparities in tobacco marketing, the characteristics of the retail environment may also be driven, in part, by demand. Neighborhoods are complex, and the retail environment is likely influenced by economic conditions, the institutional and regulatory environments, and community demography.100 Thus, the complex interplay between demand and marketing may influence the types of retailers present, the products they carry, and their tobacco marketing.

Conclusions

Lower-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods with more Black residents are disproportionately exposed to tobacco industry marketing. Menthol disparities are more striking for neighborhoods with more Black residents than for all other demographic groups. Neighborhoods with a higher proportion of Latino residents showed no evidence of disproportionate marketing, and little evidence is available regarding tobacco marketing targeting neighborhoods with more Asian American residents. Although targeted marketing is a normative business practice,83 its use for a unique class of consumer products that kill up to half27 of their users is an important issue of social injustice. Regulatory action, denormalization of these marketing practices, and community mobilization are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institutes of Health ([NIH]; awards U01CA154281 and F31CA186434).

An earlier version of this research was presented at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Philadelphia, PA, February 27, 2015.

Our many thanks go to Mellanye Lackey, MSI, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), Health Sciences Library, for her time and for the many improvements she made to our search strategy. Marcella H. Boynton, PhD, provided exceptionally helpful statistical advice and encouragement. Andrew B. Seidenberg, MPH, provided helpful comments on the article. We thank Justin T. Bailey, MPH, for his coding assistance and Abigail Shapiro, MSPH, for her diligence in verifying effect sizes and her thoughtful comments on the process and the article.

K. M. Ribisl is on the board of directors of Counter Tools (http://countertools.org), a nonprofit that distributes store mapping and store audit tools from which he receives compensation. K. M. Ribisl and J. G. L. Lee also have a royalty interest in a store audit and a mapping system owned by UNC. The tools and audit mapping system were not used in this study. K. M. Ribisl has served as an expert consultant in litigation against cigarette manufacturers.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Human Participant Protection

No human participant protection was required because no human participants were involved in this study.

References

- 1.Franco M, Nandi A, Glass T, Diez-Roux A. Smoke before food: a tale of Baltimore City. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1178. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.105262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute for Global Tobacco Control. State of evidence review: point of sale promotion of tobacco products. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2013. Available at: http://globaltobaccocontrol.org/resources/state-evidence-review-point-sale-promotion-tobacco-products. Accessed May 25, 2015.

- 3.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Smokeless Tobacco Report for 2009 and 2010. 2012. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Federal Trade Commission. Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Report for 2009 and 2010. 2012. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Trends in exposure to pro-tobacco advertisements over the Internet, in newspapers/magazines, and at retail stores among US middle and high school students, 2000–2012. Prev Med. 2013;58:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson L, McGee R, Marsh L, Hoek J. A systematic review on the impact of point-of-sale tobacco promotion on smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(1):2–17. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakefield MA, Ruel EE, Chaloupka FJ, Slater SJ, Kaufman NJ. Association of point-of-purchase tobacco advertising and promotions with choice of usual brand among teenage smokers. J Health Commun. 2002;7(2):113–121. doi: 10.1080/10810730290087996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakefield M, Germain D, Henriksen L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiction. 2008;103(2):322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter OB, Mills BW, Donovan RJ. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on unplanned purchases: results from immediate postpurchase interviews. Tob Control. 2009;18(3):218–221. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Germain D, McCarthy M, Wakefield M. Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: a cohort study. Addiction. 2010;105(1):159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoek J, Gifford H, Pirikahu G, Thomson G, Edwards R. How do tobacco retail displays affect cessation attempts? Findings from a qualitative study. Tob Control. 2010;19(4):334–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yerger VB, Przewoznik J, Malone RE. Racialized geography, corporate activity, and health disparities: tobacco industry targeting of inner cities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4, suppl):10–38. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz TB, Wright LT, Crawford G. The menthol marketing mix: targeted promotions for focus communities in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl 2):S147–S153. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green MP, McCausland KL, Xiao H, Duke JC, Vallone DM, Healton CG. A closer look at smoking among young adults: where tobacco control should focus its attention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1427–1433. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.103945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Apollonio DE, Malone RE. Marketing to the marginalised: tobacco industry targeting of the homeless and mentally ill. Tob Control. 2005;14(6):409–415. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amos A, Greaves L, Nichter M, Bloch M. Women and tobacco: a call for including gender in tobacco control research, policy and practice. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):236–243. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrow M, Barraclough S. Gender equity and tobacco control: bringing masculinity into focus. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(1 suppl):21–28. doi: 10.1177/1757975909358349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens P, Carlson LM, Hinman JM. An analysis of tobacco industry marketing to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) populations: strategies for mainstream tobacco control and prevention. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(3, suppl):129S–134S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackbarth DP, Silvestri B, Cosper W. Tobacco and alcohol billboards in 50 Chicago neighborhoods: market segmentation to sell dangerous products to the poor. J Public Health Policy. 1995;16(2):213–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luke D, Esmundo E, Bloom Y. Smoke signs: patterns of tobacco billboard advertising in a metropolitan region. Tob Control. 2000;9(1):16–23. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoddard JL, Johnson CA, Sussman S, Dent C, Boley-Cruz T. Tailoring outdoor tobacco advertising to minorities in Los Angeles County. J Health Commun. 1998;3(2):137–146. doi: 10.1080/108107398127427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Primack BA, Bost JE, Land SR, Fine MJ. Volume of tobacco advertising in African American markets: systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(5):607–615. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altman DG, Schooler C, Basil MD. Alcohol and cigarette advertising on billboards. Health Educ Res. 1991;6(4):487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, Fortmann SP. Targeted advertising, promotion, and price for menthol cigarettes in California high school neighborhoods. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):116–121. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jha P, Peto R, Zatonski W, Boreham J, Jarvis MJ, Lopez AD. Social inequalities in male mortality, and in male mortality from smoking: indirect estimation from national death rates in England and Wales, Poland, and North America. Lancet. 2006;368(9533):367–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68975-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yudelson J. Adapting McCarthy’s four P’s for the twenty-first century. J Mark Educ. 1999;21(1):60–67. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fotheringham AS, Rogerson PA. GIS and spatial analytical problems. Int J Geogr Inf Syst. 1993;7(1):3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rose SW, Myers AE, D’Angelo H, Ribisl KM. Retailer adherence to Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, North Carolina, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E47. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frick RG, Klein EG, Ferketich AK, Wewers ME. Tobacco advertising and sales practices in licensed retail outlets after the Food and Drug Administration regulations. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):963–967. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodruff SI, Wildey MB, Conway TL, Clapp EJ. Effect of a brief retailer intervention to reduce the sale of single cigarettes. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(3):172–174. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.3.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose SW, Barker DC, D’Angelo H et al. The availability of electronic cigarettes in US retail outlets, 2012: results of two national studies. Tob Control. 2014;23(suppl 3):iii10–iii16. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katikireddi SV, Egan M, Petticrew M. How do systematic reviews incorporate risk of bias assessments into the synthesis of evidence? A methodological study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(2):189–195. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Archbald C. Sale of individual cigarettes: a new development. Pediatrics. 1993;91(4):851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbeau EM, Wolin KY, Naumova EN, Balbach E. Tobacco advertising in communities: associations with race and class. Prev Med. 2005;40(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bernstein SL, Cabral L, Maantay J et al. Disparities in access to over-the-counter nicotine replacement products in New York City pharmacies. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1699–1704. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braverman MT, D’Onofrio CN, Moskowitz JM. Marketing smokeless tobacco in California communities: implications for health education. NCI Monogr. 1989;(8):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantrell J, Kreslake JM, Ganz O et al. Marketing little cigars and cigarillos: advertising, price, and associations with neighborhood demographics. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1902–1909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi K, Fabian LE, Brock B, Engman KH, Jansen J, Forster JL. Availability of snus and its sale to minors in a large Minnesota city. Tob Control. 2014;23(5):449–451. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Cruz T, Unger JB. An examination of trends in amount and type of cigarette advertising and sales promotions in California stores, 2002–2005. Tob Control. 2008;17(2):93–98. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.022046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freedman DA. Local food environments: they’re all stocked differently. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;44(3–4):382–393. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gany F, Rastogi N, Suri A, Hass C, Bari S, Leng J. Smokeless tobacco: how exposed are our schoolchildren? J Community Health. 2013;38(4):750–752. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hickman N, Klonoff EA, Landrine H et al. Preliminary investigation of the advertising and availability of PREPs, the new “safe” tobacco products. J Behav Med. 2004;27(4):413–424. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000042413.69425.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.John R, Cheney MK, Azad MR. Point-of-sale marketing of tobacco products: taking advantage of the socially disadvantaged? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(2):489–506. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirchner TR, Villanti AC, Cantrell J et al. Tobacco retail outlet advertising practices and proximity to schools, parks and public housing affect Synar underage sales violations in Washington, DC. Tob Control. 2015;24(e1):e52–e58. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klonoff EA, Fritz JM, Landrine H, Riddle RW, Tully-Payne L. The problem and sociocultural context of single-cigarette sales. JAMA. 1994;271(8):618–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Alcaraz R. Minors’ access to single cigarettes in California. Prev Med. 1998;27(4):503–505. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lane SD, Keefe RH, Rubinstein R et al. Structural violence, urban retail food markets, and low birth weight. Health Place. 2008;14(3):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laws MB, Whitman J, Bowser DM, Krech L. Tobacco availability and point of sale marketing demographically contrasting districts of Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 2):ii71–ii73. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lipperman-Kreda S, Grube JW, Friend KB. Contextual and community factors associated with youth access to cigarettes through commercial sources. Tob Control. 2014;23(1):39–44. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lipperman-Kreda S, Lee JP, Morrison C, Freisthler B. Availability of tobacco products associated with use of marijuana cigars (blunts) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moreland-Russell S, Harris J, Snider D, Walsh H, Cyr J, Barnoya J. Disparities and menthol marketing: additional evidence in support of point of sale policies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(10):4571–4583. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10104571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pucci LG, Joseph HM, Jr, Siegel M. Outdoor tobacco advertising in six Boston neighborhoods. Evaluating youth exposure. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15(2):155–159. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruel E, Mani N, Sandoval A et al. After the Master Settlement Agreement: trends in the American tobacco retail environment from 1999 to 2002. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(34 suppl):99S–110S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seidenberg AB, Caughey RW, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Storefront cigarette advertising differs by community demographic profile. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24(6):e26–e31. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090618-QUAN-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siahpush M, Jones PR, Singh GK, Timsina LR, Martin J. The association of tobacco marketing with median income and racial/ethnic characteristics of neighbourhoods in Omaha, Nebraska. Tob Control. 2010;19(3):256–258. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slater S, Giovino G, Chaloupka F. Surveillance of tobacco industry retail marketing activities of reduced harm products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(1):187–193. doi: 10.1080/14622200701704947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toomey TL, Chen V, Forster JL, Van Coevering P, Lenk KM. Do cigarette prices vary by brand, neighborhood, and store characteristics? Public Health Rep. 2009;124(4):535–540. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voorhees CC, Swank RT, Stillman FA, Harris DX, Watson HW, Becker DM. Cigarette sales to African-American and White minors in low-income areas of Baltimore. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(4):652–654. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Widome R, Brock B, Klein EG, Forster JL. Smokeless tobacco advertising at the point of sale: prevalence, placement, and demographic correlates. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(2):217–223. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Widome R, Brock B, Noble P, Forster JL. The relationship of neighborhood demographic characteristics to point-of-sale tobacco advertising and marketing. Ethn Health. 2013;18(2):136–151. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.701273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wildey MB, Young RL, Elder JP et al. Cigarette point-of-sale advertising in ethnic neighborhoods in San Diego, California. Health Values. 1992;16(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodruff SI, Agro AD, Wildey MB, Conway TL. Point-of-purchase tobacco advertising: prevalence, correlates, and brief intervention. Health Values. 1995;19(5):56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burton S, Williams K, Fry R et al. Marketing cigarettes when all else is unavailable: evidence of discounting in price-sensitive neighbourhoods. Tob Control. 2014;23(e1):e24–e29. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalglish E, McLaughlin D, Dobson A, Gartner C. Cigarette availability and price in low and high socioeconomic areas. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013;37(4):371–376. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCarthy M, Scully M, Wakefield M. Price discounting of cigarettes in milk bars near secondary schools occurs more frequently in areas with greater socioeconomic disadvantage. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2011;35(1):71–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wakefield M, Zacher M, Scollo M, Durkin S. Brand placement on price boards after tobacco display bans: a point-of-sale audit in Melbourne, Australia. Tob Control. 2012;21(6):589–592. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zacher M, Germain D, Durkin S, Hayes L, Scollo M, Wakefield M. A store cohort study of compliance with a point-of-sale cigarette display ban in Melbourne, Australia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):444–449. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohen JE, Planinac LC, Griffin K et al. Tobacco promotions at point-of-sale: the last hurrah. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(3):166–171. doi: 10.1007/BF03405466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barnoya J, Mejia R, Szeinman D, Kummerfeldt CE. Tobacco point-of-sale advertising in Guatemala City, Guatemala and Buenos Aires, Argentina. Tob Control. 2010;19(4):338–341. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bansal R, John S, Ling PM. Cigarette advertising in Mumbai, India: targeting different socioeconomic groups, women, and youth. Tob Control. 2005;14(3):201–206. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quedley M, Ng B, Sapre N et al. In sight, in mind: retailer compliance with legislation on limiting retail tobacco displays. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(8):1347–1354. doi: 10.1080/14622200802238860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Devlin E, Anderson S, Borland R, MacKintosh AM, Hastings G. Development of a research tool to monitor point of sale promotions. Soc Mar Q. 2006;12(1):29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 77.MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alwitt LF, Donley TD. Retail stores in poor urban neighborhoods. J Consum Aff. 1997;31(1):139–164. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shareck M, Frohlich KL, Poland B. Reducing social inequities in health through settings-related interventions—a conceptual framework. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(2):39–52. doi: 10.1177/1757975913486686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ashe M, Jernigan D, Kline R, Galaz R. Government, politics, and law. Land use planning and the control of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and fast food restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1404–1408. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McLaughlin I, Pearson A, Laird-Metke E, Ribisl K. Reducing tobacco use and access through strengthened minimum price laws. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(10):1844–1850. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grier SA, Kumanyika S. Targeted marketing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:349–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Castree N, Kitchin R, Rogers A, editors. A Dictionary of Human Geography. London, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beaumont JR, Inglis K. Geodemographics in practice: developments in Britain and Europe. Environ Plann A. 1989;21(5):587–604. doi: 10.1068/a210605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Batey P, Brown P. From human ecology to customer targeting: the evolution of geodemographics. In: Longley P, Clarke G, editors. GIS for Business and Service Planning. Cambridge, UK: GeoInformation International; 1995. pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Store segmentation. Brown & Williamson. Bates no. 311102903. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/npf12d00. Accessed June 9, 2015.

- 88. IRDD—What is the concept? Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2061620188-2061620204. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vgr00b00. Accessed June 9, 2015.

- 89.Price value strategy study. Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2070023809-2070023957. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/jzh31b00. Accessed June 9, 2015.

- 90. Account review 2.0: incorporation share based clustering, business requirements, January 10, 1997. Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2071866577-2071866645. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qka31b00. Accessed June 9, 2015.

- 91. Integrated retail demographic database micro-marketing tool. Philip Morris USA. Bates no. 2071923172-2071923200. Available at: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gfy59h00. Accessed June 9, 2015.

- 92.Greaves L, Johnson J, Bottorff J et al. What are the effects of tobacco policies on vulnerable populations? A better practices review. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(4):310–315. doi: 10.1007/BF03405610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e89–e97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Main C, Thomas S, Ogilvie D et al. Population tobacco control interventions and their effects on social inequalities in smoking: placing an equity lens on existing systematic reviews. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tauras JA. Differential impact of state tobacco control policies among race and ethnic groups. Addiction. 2007;102(suppl 2):95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):216–221. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):147–153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Garrett BE, Dube SR, Babb S, McAfee T. Addressing the social determinants of health to reduce tobacco-related disparities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu266. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rogers T, Feighery EC, Tencati EM, Butler JL, Weiner L. Community mobilization to reduce point-of-purchase advertising of tobacco products. Health Educ Q. 1995;22(4):427–442. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bernard P, Charafeddine R, Frohlich KL, Daniel M, Kestens Y, Potvin L. Health inequalities and place: a theoretical conception of neighbourhood. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1839–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]