Abstract

Connexins (Cxs), proteins that are vital for intercellular communication in vertebrates, have recently been shown to play a critical role in lymphatic development. However, our knowledge is currently limited regarding the functional relationships of Cxs with other proteins and signaling pathways. Cell culture studies have shown that Cx37 is necessary for coordinated activation of the transcription factor NFATc1, which cooperates with Foxc2 (another transcription factor) during lymphatic endothelial development. These data suggest that Cxs, Foxc2, and NFATc1 are part of a common developmental pathway. Here, we present a detailed characterization of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, demonstrating that lymphatic network architecture and valve formation rely on the concurrent embryonic expression and function of Foxc2 and Cx37. Foxc2 +/−Cx37−/− mice have lymphedema in utero, exhibit craniofacial abnormalities, show severe dilation of intestinal lymphatics, display abnormal lacteal development, lack lymphatic valves, and typically die perinatally (outcomes not seen in Foxc2 +/− or Cx37−/− mice separately). We provide a rigorous, quantitative documentation of lymphatic vascular network changes that highlight the specific structural alterations that occur in Foxc2+/− Cx37−/− mice. These data provide further evidence suggesting that Foxc2 and Cx37 are elements in a common molecular pathway directing lymphangiogenesis.

Keywords: Cx37, Foxc2, lymphatic valve, vascular development, lymphedema, lymphangiogenesis

Introduction

Lymph vessels in humans form an extensive, hierarchical network that serves the body by executing a number of key functions: the trafficking of immune cells, absorption of dietary lipids, and maintenance of extracellular fluid balance. A spectrum of diseases is directly related to dysfunction of the lymphatic system. Complications with immune cell trafficking are associated with inflammatory and autoimmune disease, obstruction of the intestinal lymph vessels can cause protein-losing enteropathy, and the inability of the lymphatic system to accommodate protein/fluid loads leads to lymphedema. In addition, the lymphatic vasculature serves as a route of metastasis for many cancers. Greater emphasis on understanding lymphatic function has recently arisen due to the appreciation that a number of pathological states involve the lymphatic vasculature (Alexander et al., 2010; Wang and Oliver, 2010). Furthermore, various human congenital diseases involve defects in the architecture of the lymphatic system arising during embryologic development, with deleterious consequences projecting into early postnatal life and adulthood.

Lymphatic vascular development and function have become burgeoning fields of study, and experiments in recent years have shed light on numerous factors and events that govern the growth, remodeling, maturation, and function of the lymphatic vasculature (Koltowska et al., 2013). According to the prevailing model, early lymphatic development in the mouse begins with the onset of Prox1 expression in localized clusters of blood endothelial cells (BECs) within the cardinal vein at embryonic day (E) 9.5, an event associated with those cells adopting a lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) identity. Those LECs then migrate away from the vein to form the lymph sacs and primary lymphatic plexus. The primary lymph plexus remodels through further sprouting, branching, and vessel fusion that establishes a hierarchy of lymph vessels throughout the tissues of the body. These vessels can be divided into two broad groups – absorptive vessels (lymph capillaries) and conducting vessels (pre-collectors, collectors, and lymph trunks). Much attention has been focused on identifying the molecular players responsible for orchestrating this developmental course. Specific transcription factors (e.g. Sox18, COUP-TFII, Prox1, Foxc2, NFATc1), cell surface receptors (e.g. Tie2, VEGFR3, neuropilin, plexin A1, ephrin-B2, β1-integrin) as well as their ligands (e.g. Ang-2, VEGF-C, semaphorins, EphB4, fibronectin), and downstream effectors are part of the ensemble responsible for shaping the lymphatic vasculature (for a review, see Koltowska et al., 2013).

FOXC2, a forkhead box, winged-helix transcription factor expressed by mesoderm and neural crest derived tissues, is essential for lymphatic development. Defective lymphatic remodeling, failure to form lymphatic valves, and abnormal mural cell coverage of lymphatic vessels have been found in Foxc2 −/− mice (Petrova et al., 2004). Foxc2−/− mice also have severe problems with cardiovascular, ocular, and skeletal development and die embryonically/perinatally (Iida et al., 1997; Winnier et al., 1997). On the other hand, Foxc2 +/− mice are viable, but have lymphatic valve insufficiency, distichiasis (double row of eyelashes), and dysmorphogenesis of lymph nodes (Kriederman et al., 2003; Shimoda et al., 2011). As such, these mice have been found to be a relevant model for lymphedema-distichiasis (LD), an autosomal dominant disorder in humans that typically presents as distichiasis and the pubertal onset of lymphedema in the lower limbs (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 153400). Mutations in the coding region for FOXC2 have been linked to this disorder (Fang et al., 2000), but some cases of LD have been identified in non-coding regions (Sholto-Douglas-Vernon et al., 2005; Witte et al., 2009).

The current study focuses on the interplay during lymphatic development between Foxc2 and connexins, a family of proteins best known for their ability to mediate intercellular communication by forming channels (termed gap junction channels) that directly link the cytoplasm of neighboring cells. Connexins can also form hemichannels (“half” of a gap junction channel) that allow the passage of substances between the cytoplasm and extracellular space. Three connexin isoforms (Cx37, Cx43, and Cx47) have been found in the murine lymphatic vasculature, and deletions or mutations in these isoforms cause lymphatic defects in mice and/or humans (Brice et al., 2013; Ferrell et al., 2010; Kanady et al., 2011). Lymphatic valve (Kanady et al., 2011; Sabine et al., 2012) and venous valve deficiencies (Munger et al., 2013) have been found in Cx37−/− mice. Cx43−/− mice are neonatal lethal and have cardiac malformations (Reaume et al., 1995), but they also lack lymphatic valves at E18.5 (Kanady et al., 2011). Combining genetic deficiencies in both Cx37 and Cx43 results in chylothorax as evidenced by the phenotype of Cx37−/−Cx43 +/− mice, while Cx37−/−Cx43 −/− embryos have lymph-blood mixing and develop lymphedema in utero (Kanady et al., 2011). In humans, late-onset lymphedema has been reported in a patient with oculodentodigital syndrome (ODD; OMIM 164200) – a disease affecting the face, eyes, teeth, and fingers – which is caused by mutations in CX43 (Brice et al., 2013). CX47 mutations in humans have also been linked to lymphedema (Ferrell et al., 2010).

From the studies above, disruption of lymphatic valve development/function was revealed as a commonality between mice lacking Foxc2, Cx37, or Cx43. Moreover, Cx37 expression in LECs of developing lymphatics was dramatically reduced in Foxc2−/− mice (Kanady et al., 2011), and siRNA knockdown of Foxc2 in cultured LECs led to a greater than 50% reduction in Cx37 mRNA levels (Sabine et al., 2012). These data suggest that Foxc2 regulates (either directly or indirectly) Cx37 expression in LECs, although direct evidence of Foxc2 binding to Cx37 gene regulatory sequences is at present lacking. In addition, Cx37 is required for coordinated activation of NFATc1, a transcription factor that coordinates with Foxc2 to regulate lymphatic collecting vessel maturation (Sabine et al., 2012). To further investigate the relationship between Foxc2 and connexins in lymphatic vascular development and function, we generated mice that have a Foxc2 deficiency in conjunction with a deficiency of either Cx37 or Cx43. We hypothesized that if Foxc2 and Cxs closely participate in a common developmental pathway, then combining deficiencies in these proteins would recapitulate or worsen the lymphatic abnormalities seen in mice with deficits in either protein alone. Our finding of exacerbated lymphatic defects in Foxc2+/−Cx37−/− mice provides further support for the idea that Foxc2 and Cx37 are part of a common molecular pathway directing lymphangiogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Cx37−/− (Gja4−/−) (Simon et al., 1997), Cx43 −/− (Gja1 −/−) (Reaume et al., 1995), and Foxc2 −/− (Iida et al., 1997) lines were maintained on a C57BL/6 background and genotyped by PCR using previously published methods (Kanady et al., 2011). Cx37 +/−, Cx43 +/−, and Foxc2 +/− mice were interbred to generate mice deficient in both Cx37 and Foxc2 or Cx43 and Foxc2. Animal protocols were approved by the IACUC Committee at the University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ).

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used for immunostaining were as follows: rabbit antibodies to Cx37 (Simon et al., 2006), Cx43 (C6219, Sigma), Prox1 (11–002, AngioBio; ab11941, Abcam), pHH3 (06–570, Millipore); rat antibodies to CD31 (550274, BD Biosciences); goat antibodies to Foxc2 (ab5060, Abcam), Vefgr3 (AF743, R&D Systems). AffiniPure minimal cross reactivity secondary antibodies (conjugated to Alexa 488, Cy3, Cy5, or Dylight 649) were from Jackson Immunoresearch.

Section immunostaining

Tissues were frozen unfixed in Tissue-tek O.C.T. and sectioned at 10 µm. Sections were fixed in acetone at −20°C for 10 minutes, blocked in a solution containing PBS, 4% fish skin gelatin, 1% donkey serum, 0.25% Triton X-100, and incubated with primary antibodies for 1.5 to 3 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed with PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 30–45 minutes. After washing, sections were mounted in Mowiol 40–88 (Aldrich) containing 1,4-diazobicyclo-(2,2,2)-octane and viewed with an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope fitted with a Photometrics CoolSnap ES2 camera.

Whole-mount immunostaining

Intestines (with mesentery attached) were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, washed in PBS, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 overnight, and then blocked overnight in solution containing PBS, 4% fish skin gelatin, 1% donkey serum, 0.25% Triton X-100. Primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 were applied to the tissue overnight at 4°C. After washing, fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. Following final washes, the mesenteries were mounted on slides in Citifluor mountant (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Skin tissue was treated similarly. Whole-mount samples were viewed with an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope fitted with a Photometrics CoolSnap ES2 camera or viewed with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

Lymphangiography with Evans blue dye

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital or ketamine/xylazine mixture and kept warm. Evans blue dye (EBD) (1% w/v) was injected intradermally into the hindpaws and a dissecting microscope was used to examine EBD transport. Evidence of abnormal dye reflux into hindlimb skin or mesenteric lymph nodes was noted if present. The thoracic cavity was then opened and the presence of EBD in the TD was noted if present along with any abnormal dye reflux into intercostal lymphatic vessels. EBD was also injected into the ear to examine EBD transport in the dermal lymph network.

Quantification of lymphatic vascular networks

Maximum intensity projections were generated from confocal z-stacks of whole-mount immunostained intestine and skin samples. Regions of intestine or skin that contained blood in the lymphatics were not included in the analysis as these could have been dilated due to luminal volume expansion. Manual image segmentation of the lymphatic vessels was then carried out based on Prox1 and CD31 or Vegfr3 immunolabeling using Adobe Photoshop CS4. The resulting segmentation was compared against the individual confocal slices used to create the maximum intensity projection to ensure accuracy. ImageJ was used to further process segmented images, and a skeletonization of the lymphatic network was created using the Skeletonize (2D/3D) plugin and measured using the AnalyzeSkeleton plugin (Arganda-Carreras et al., 2010). Segmented images were loaded into AngioTool (Zudaire et al., 2011) for calculation of lacunarity (determined through box counting). Further details are provided as a supplement (Fig. S1). Lacteal length was measured from confocal z-stacks using ImageJ and the Simple Neurite Tracer plugin (Longair et al., 2011). Lacteal density was calculated by counting the number of lacteals in X-Z projections and dividing by the area of the field.

Statistical Analysis

At least three embryos per genotype were analyzed for all comparisons. Student’s t-test (two-tailed, unequal variance) was performed for results in figure 8I. For figures 2F, 5I–L, 6I–J, and 9P–U, single factor ANOVA was performed for multi-wise comparisons with post hoc Tukey-Kramer tests when ANOVA yielded a significant result. Values were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

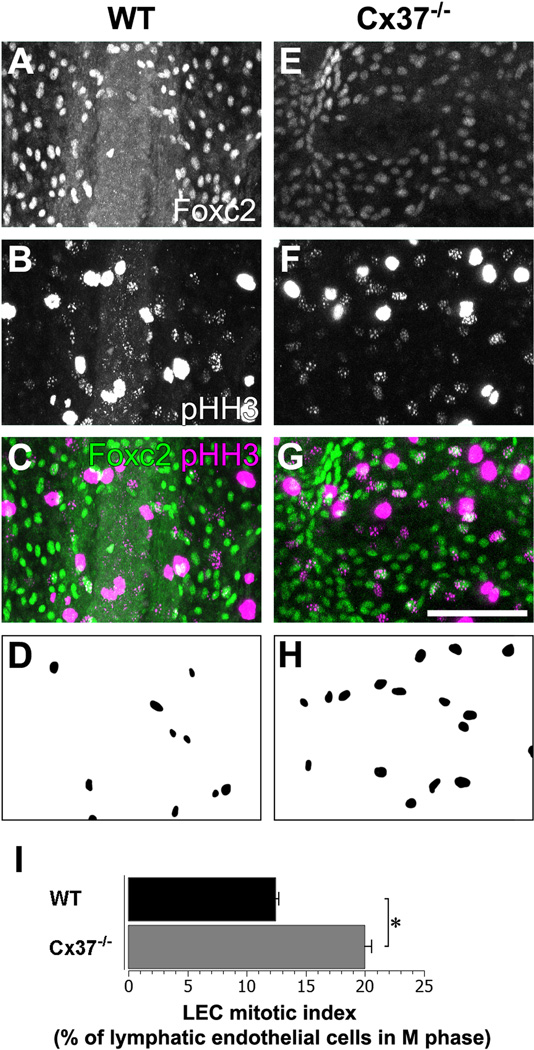

Figure 8.

Mesenteric lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) of Cx37 −/− mice are more mitotically active than WT mice. Foxc2 (A) and phospho-Histone H3 (pHH3, B) immunolabeling of WT mesenteric lymphatic vessels. (C) Colocalization of Foxc2 (green) and pHH3 (magenta) signal highlight LECs that are in M-phase of the cell cycle. (D) Segmentation of mitotic LECs (Foxc2+/pHH3+ cells) in (C). Foxc2 (E) and pHH3 (F) immunolabeling of Cx37 −/− mesenteric lymphatic vessels. (G) A greater number of mesenteric LECs show colocalization of Foxc2 (green) and pHH3 (magenta) signal in Cx37 −/− mice. (H) Segmentation of mitotic LECs (Foxc2+/pHH3+ cells) in (G). (I) LEC mitotic index measured as the number of Foxc2+pHH3+ cells divided by total number of Foxc2+ cells; there is a significant increase in the percentage of mitotic mesenteric LECs in Cx37 −/− mice compared to WT. Note that there is non-specific labeling of the cytoplasm of macrophages and mast cells with the pHH3 antibody, seen as the saturated signal from cells in white (B,F) and magenta (C,G). Scale bars: (A–C, E–G) 100 µm. Values are presented as means, with error bars indicating standard error of the mean. Asterisks, p < 0.05.

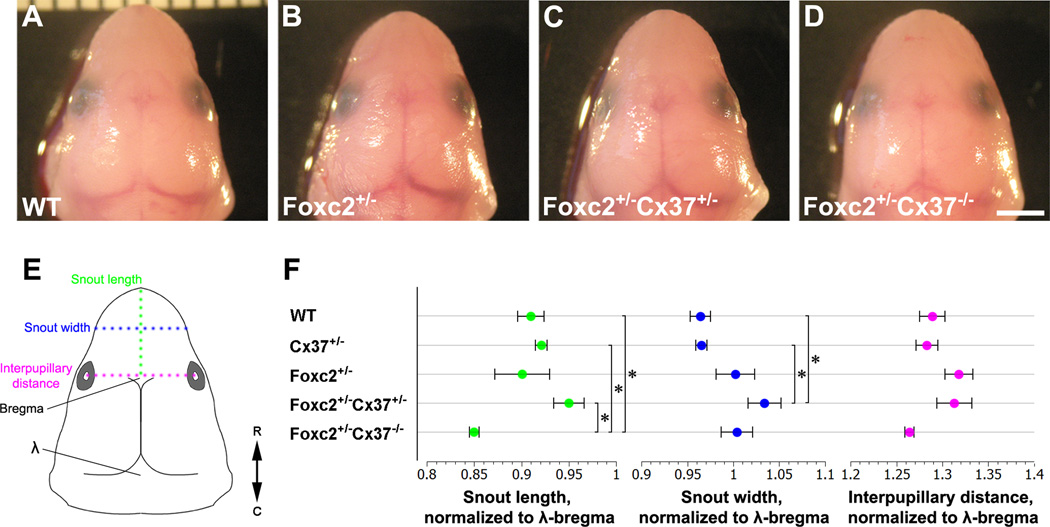

Figure 2.

Craniofacial morphometrics of E18.5 embryos. (A–D) Superior view of the head of littermates with the following genotypes: WT (A), Foxc2 +/− (B), Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− (C), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (D). (E) Schematic diagram of the embryonic head indicating where snout length (green), snout width (blue), and interpupillary distance (magenta) were measured. Bregma and lambda (λ) are shown on the schematic at the anterior and posterior fontanelles, respectively. Double-headed arrow denotes R (rostral) and C (caudal) directions. (F) Numeric measures of snout length (green points), snout width (blue points), and interpupillary distance (magenta points) normalized to λ –bregma distance are graphed for WT, Cx37 +/−, Foxc2 +/−, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice. The length of the snouts of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/−mice were significantly shorter than WT, Cx37 +/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− mice. The width of the snouts of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− mice were significantly greater than WT and Cx37 +/− mice. No statistically significant differences were found for interpupillary distance among genotypes analyzed. Scale bar: (A–D) 2 mm. Values are presented as means, with error bars indicating standard error of the mean. Asterisks, p < 0.05.

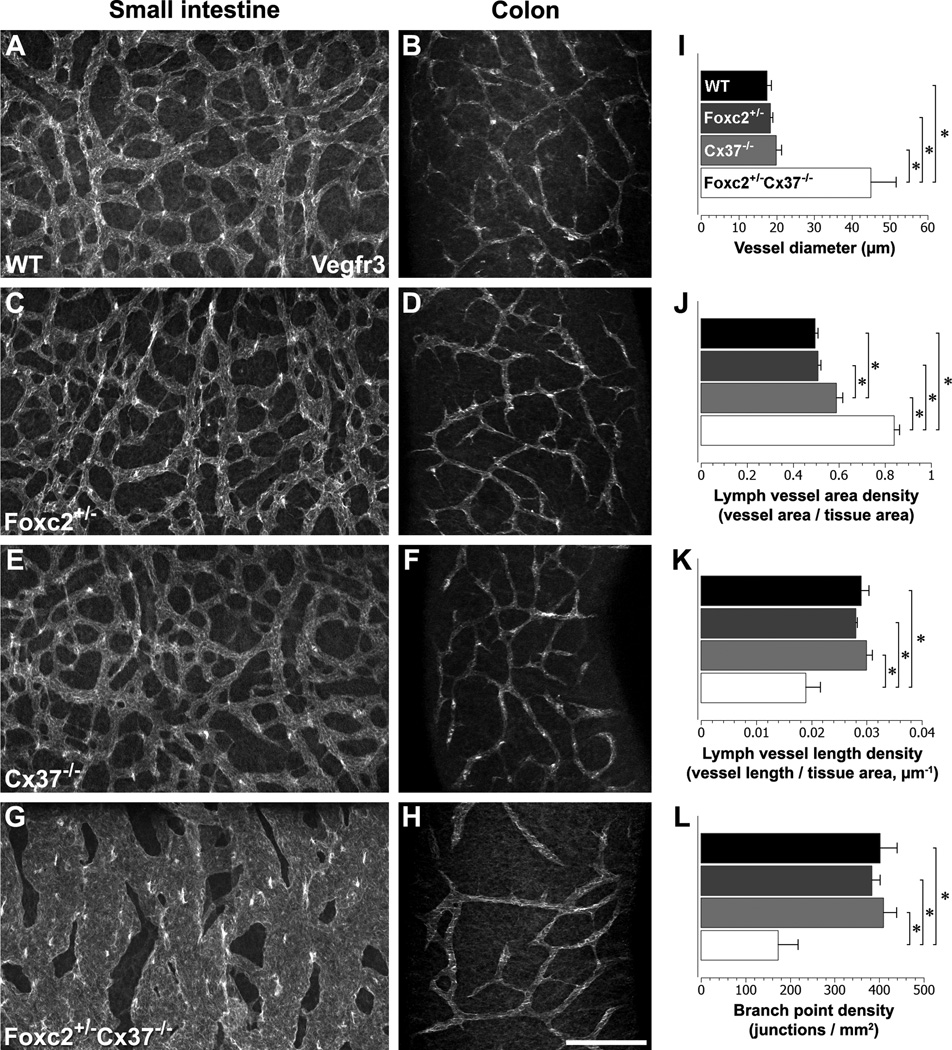

Figure 5.

Characterization of intestinal lymphatics in WT, Foxc2 +/−, Cx37 −/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5. Confocal immunomicrographs of the small intestine and colon from E18.5 WT (A,B), Foxc2 +/− (C,D), Cx37 −/− (E,F), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice are shown; samples were probed for Vegfr3. The lymphatic vessels were segmented based on Vegfr3 signal and skeletonized. (I–L) Quantitation of the submucosal lymphatic network of the proximal small intestine. Submucosal lymph vessel diameter (I) and submucosal lymph vessel area density (I) of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were significantly greater than WT, Foxc2 +/−, and Cx37 −/−mice. Submucosal lymph vessel length density (K) and submucosal lymphatic branch point density (L) of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were significantly lower than WT, Foxc2 +/−, and Cx37 −/−mice. Additionally, submucosal lymph vessel area density of Cx37 −/− mice was significantly greater than WT and Foxc2 +/− mice. Scale bar: (A–H) 200 µm. Values are presented as means, with error bars indicating standard error of the mean. Asterisks, p < 0.05.

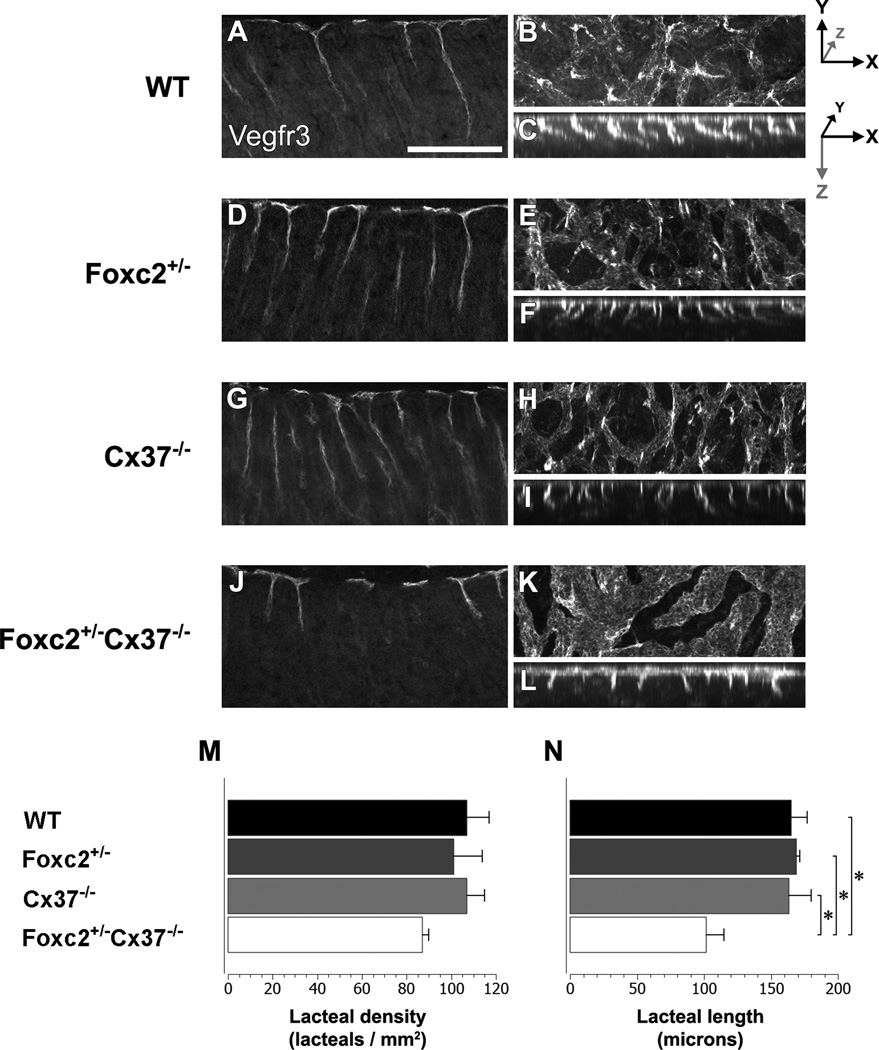

Figure 6.

Lacteal development is disrupted in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5. Vegfr3 whole-mount immunostaining (imaged via confocal microscopy) highlights the submucosal lymphatics and lacteals of the proximal small intestine in WT (A–C), Foxc2 +/− (D–F), Cx37 −/− (G–I) and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (J–L) mice. Single longitudinal sections (optical) from WT (A), Foxc2 +/− (D), Cx37 −/− (G), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (J) mice. Maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stacks in the X-Y and X-Z planes for WT (B,C), Foxc2 +/− (E,F), Cx37 −/− (H,I), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/−(K,L) mice. In X-Y projections (B,E,H,K), lacteals are seen as intense regions of Vegfr3 signal. In X-Z projections (C,F,I,L), individual lacteals resemble ropes hanging from the top of each image. Intestinal lumen is directed towards the bottom of the image in (A,C,D,F,G,I,J,L). Measurements of lacteal density (M) and lacteal length (N) for WT (black bars), Foxc2 +/− (dark grey bars), Cx37 −/− (light grey bars), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (white bars) mice are shown. Lacteals from Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were significantly shorter than WT, Foxc2 +/−, and Cx37 −/− mice. Scale bar: (A–L) 200 µm. Values are presented as means, with error bars indicating standard error of the mean. Asterisks, p < 0.05.

Results

Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice exhibit generalized edema, craniofacial abnormalities, and die perinatally

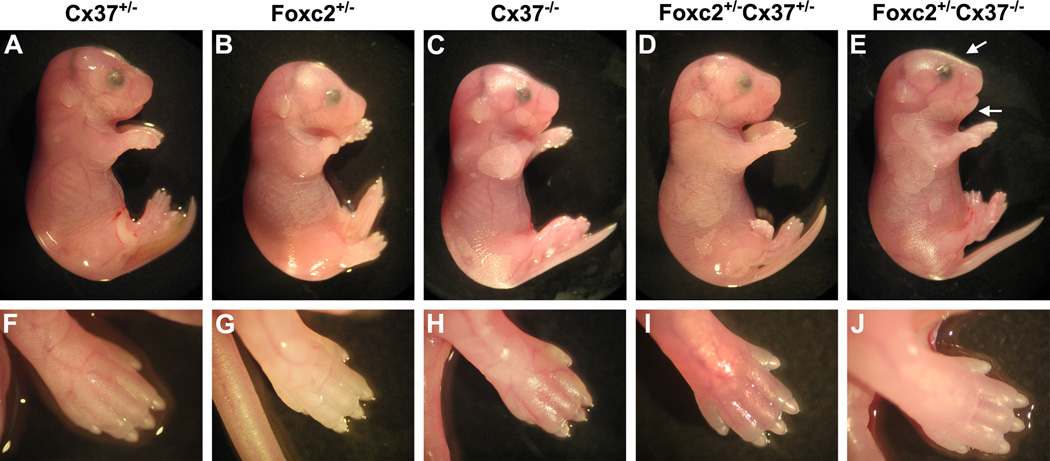

We surveyed mouse embryos at embryonic day (E) 18.5 for gross phenotypic differences among the following genotypes: Cx37 +/−, Cx37 −/−, Foxc2 +/−, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/−. Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− embryos were similar in appearance to wild type (WT), Cx37 +/−, Cx37 −/−, and Foxc2 +/− embryos (Fig. 1A–D). Conversely, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− embryos had an overall swollen appearance (indicative of generalized edema), with the extremities of these animals also affected (Fig. 1E,J). Blunting of the snout was also noted as a common feature in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice. Thus, while Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− embryos were overtly normal, lymphedema only became apparent when there was Foxc2 haploinsufficiency in conjunction with the complete loss of Cx37.

Figure 1.

Gross images of E18.5 mice. Littermates with the following genotypes are shown: Cx37 +/− (A,F), Foxc2 +/− (B,G), Cx37 −/− (C,H), Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− (D,I), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/−(E,J). Lateral views of the whole embryo (A–E), with corresponding images of the hindlimb (F–J). Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− embryos presented with mild generalized edema (E) that also affected the hindlimbs (J). Flattening of the nasal bridge (E, upper arrow) and micrognathism (E, lower arrow) also occurred. No overt differences in gross embryonic morphology were notable among the other genotypes (A-D, F-I).

Dysmorphic facial features and defects in skeletogenesis have been reported in Foxc2 −/− mice, but Foxc2 +/− mice have been described as overtly normal in these respects (Iida et al., 1997; Winnier et al., 1997). Given our initial observations that Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− embryos had blunted snouts, we performed morphometric analysis of the head in order to further characterize any craniofacial differences. Length of the snout, snout width, and interpupillary distance were measured and expressed as a ratio of the distance between lambda and bregma (points at the posterior and anterior fontanelles, respectively) in E18.5 mice (Fig. 2A–F). The snout length of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (0.850 +/− 0.005) embryos was 7% shorter than WT (0.910 +/− 0.014), 8% shorter than Cx37 +/− (0.921 +/− 0.006), and 11% shorter than Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− (0.950 +/− 0.016) embryos. The snout of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− (1.034 +/− 0.018) mice was 7% wider than WT (0.964 +/− 0.014) and 7% wider than Cx37 +/− (0.965 +/− 0.006) embryos. There were no statistically significant changes in interpupillary distance. While craniofacial abnormalities have been associated with human cases of lymphedema-distichiasis, we were unable to find differences in Foxc2 +/− mice compared to other genotypes using the parameters measured. Interestingly, craniofacial differences only manifested when Foxc2 hemizygosity was combined with the loss of one or both alleles of Cx37 in the mice we surveyed.

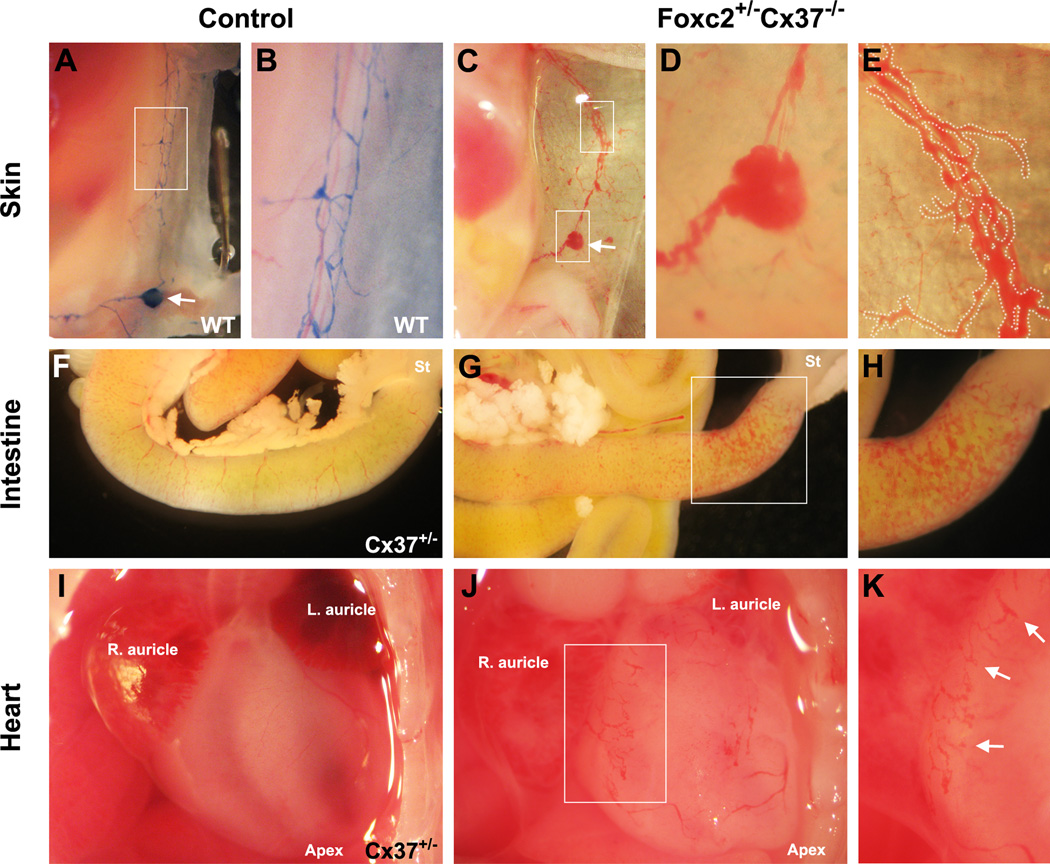

Aggregations of blood were faintly visible through the skin of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5. Dissections of the embryos revealed that the inguinal lymph node, as well as the dermal lymphatic vessels surrounding it, contained blood (Fig. 3A–E, Fig. S2). Within the mesentery and intestinal wall of the proximal small intestine, there was a network of blood-containing, dilated vessels in some embryos (Fig. 3F–H). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the lymphatic identity of these vessels. The degree and extent to which blood was observed in the lymphatic vessels of the skin and intestine varied from mild to severe. Since Foxc2 −/− mice have been reported to have defects in the formation and patterning of the aortic arch (Iida et al., 1997; Winnier et al., 1997), we also inspected the heart, aorta, and its distributary blood vessels in these animals. There were no discernible abnormalities in the aorta or the principal arterial branches arising from it compared to other genotypes. However, wide, blind-ended, blood-filled vessels were present on the surface of the heart, and were likely dilated pericardial lymphatic vessels (Fig. 3I–K). Thus, in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, lymph-blood mixing occurred in the skin, intestine, and pericardial lymphatics, and these mice showed signs of intestinal and pericardial lymphangiectasia at E18.5.

Figure 3.

Lymph-blood mixing in the lymphatics of the skin (C–E), intestines (G,H), and heart (J,K) of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5. (A) Evans blue dye (EBD) injection of E18.5 WT embryo showing normal drainage pattern from the inguinal lymph node (arrow) and thoracoepigastric lymphatic vessels. (B) Thoracoepigastric lymph vessels, higher magnification view of the white box from (A); note the fine caliber of WT lymph vessels in this region. (C) Blood within the inguinal lymph node (lower box, arrow denotes same anatomical region as lymph node in panel A) and thoracoepigastric lymph vessels (upper box) of a Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/−embryo. (D) Higher magnification view of lymph node from (C). (E) Higher magnification view of thoracoepigastric lymph vessels from (C); blood-filled lymph vessels are digitally outlined in white for better contrast. (F) Gross image of the small intestine from an E18.5 Cx37 +/− control embryo, compared to a Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− littermate (G). (H) Higher magnification view of white box from (G); blood is present within the serosal lymphatics in the proximal small intestine. (I) Gross image of the heart from E18.5 Cx37 +/− control embryo; right/left auricles and apex are labeled. (J) Blood accumulation in blind-ended vessels of the pericardium in an E18.5 Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− embryo. (K) Higher magnification view of white box from (J), arrows highlight blood-filled lymph vessels.

Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice collected at E13.5, E18.5 and postnatal day (P) 0 showed similar developmental progression compared to littermates. Most embryos collected at E18.5 and P0 attempted to breathe and responded to physical stimuli. However, only two animals of this genotype survived past weaning age – one died at two months and one at seven months of age. While Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were fully developed in general by birth, most died either perinatally or before weaning age.

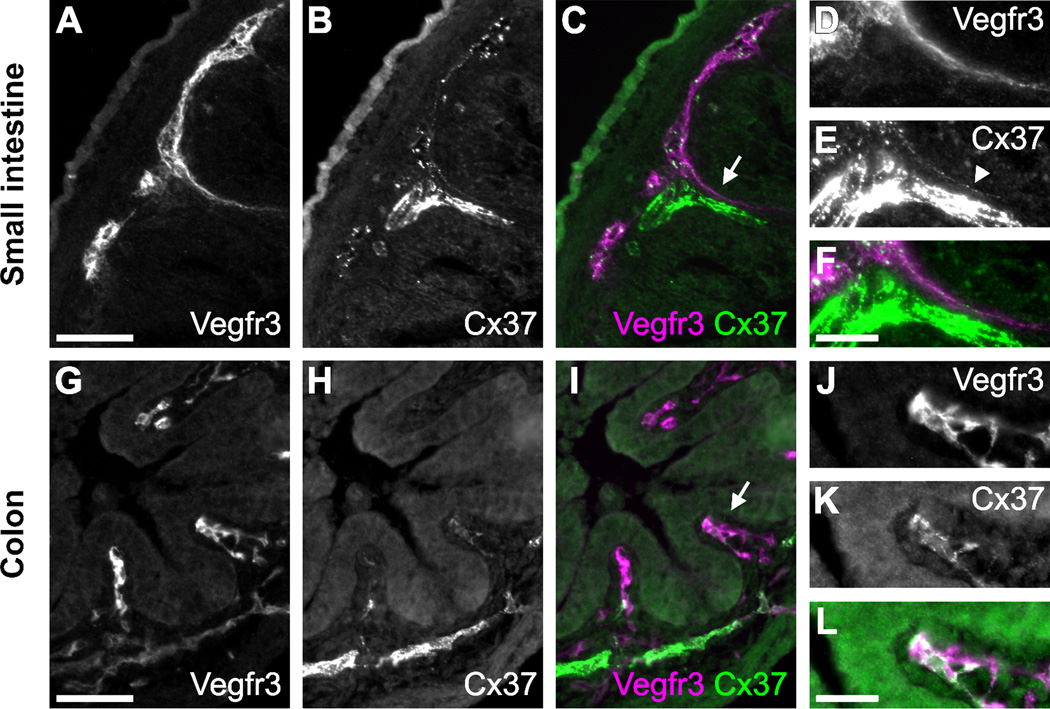

Cx37 is expressed in the lacteals and submucosal lymph vessels of E18.5 mice

Lacteals are specialized lymphatic capillaries found in the villi of the small intestine that are responsible for a large portion of dietary fat and lipid-soluble vitamin absorption. In a previous survey of Cx37 expression, we failed to detect Cx37 expression in lacteals (Kanady et al., 2011). However, given the defects in the formation of the intestinal lymphatic vasculature in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, we looked more closely for Cx37 immunostaining in the lymphatic vessels serving the intestines of E18.5 WT mice. Antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (Vegfr3) were used to identify LECs. Vegfr3 is expressed by both blood and lymphatic endothelial cells during early embryogenesis, but becomes primarily restricted to LECs later in development, where its activation is required for lymphangiogenesis (Kaipainen et al., 1995; Karkkainen et al., 2004). Punctate Cx37 staining was detected in the lacteals (weakly) and submucosal lymphatics of both the small (Fig. 4A–F) and large intestine (Fig. 4G–L).

Figure 4.

Cx37 is expressed in the submucosal lymphatics of the small intestine and colon. Cryosections of the small intestine (A–F) and colon (G–L) of E18.5 WT mice are shown. Vegfr3 immunostaining was used to identify submucosal lymphatic vessels. (A) Vegfr3 and (B) Cx37 immunolabeling of the submucosal lymphatics of the small intestine. (C) Vegfr3 (magenta) and Cx37 (green) signals colocalize in the submucosal lymphatics and lacteal. (D–F) Higher magnification view of the area denoted by the arrow in (C), arrowhead in (E) indicates relevant area of Cx37 expression within the lacteal. Vegfr3 (G) and Cx37 (H) immunolabeling of the submucosal lymphatics of the colon. (I) Vegfr3 (magenta) and Cx37 (green) signals colocalize in the submucosal lymphatics. (J–L) Higher magnification view of the area denoted by the arrow in (I). The bright, saturated Cx37 signal in (E) is from the arterial submucosal vasculature, also in the lower part of panel (H). Scale bars: (A-C, G-I) 50 µm; (D-F, J-L) 25 µm.

Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice have dilated submucosal lymph vessels in the small intestine and defects in mesenteric lymph vessel remodeling and maturation

We performed whole-mount immunofluorescence staining of E18.5 intestines using antibodies against Vegfr3 to visualize the intact intestinal lymphatic vasculature (Fig. 5A–H). Confocal microscopy was used to optically section through the intestinal wall and evaluate the submucosal lymphatic network and lacteals. By E18.5, the submucosal lymphatic network in WT mice has formed a highly branched system of vessels mostly homogenous in diameter (Fig. 5A). In comparison, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− samples had a striking derangement of the submucosal lymphatic vasculature, which formed a disorganized network of dilated, cavernous lymph vessels (Fig. 5G). These vessels were erratic in caliber, ranging from approximately 20 to over 250 microns in diameter. This variation in vessel caliber gave the network a mesh-like appearance with holes that differed greatly in size. The mean submucosal lymph vessel diameter of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (45.0 +/− 6.63 µm) mice was 158% greater than WT (17.5 +/− 1.15 µm) mice, 145% greater than Foxc2 +/− (18.36 +/− 0.65 µm), and 125% greater than Cx37 −/− (19.96 +/− 1.33 µm) mice (Fig. 5I). The submucosal lymphatic vascular area density (lymph vessel area/tissue area) was 69% greater in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (0.840 +/− 0.022) mice compared to WT (0.496 +/− 0.013) mice, 65% greater compared to Foxc2 +/− (0.509 +/− 0.012) mice, and 43% greater compared to Cx37 −/− (0.593 +/− 0.024) mice (Fig. 5J). Conversely, lymphatic vascular length density (vessel length/tissue area) in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (0.019 +/− 0.0026) mice was 35% less than WT (0.029 +/− 0.0014) mice, 32% less than Foxc2 +/− (0.028 +/− 0.0003) mice, and 37% less than Cx37 −/− (0.030 +/− 0.0011) mice (Fig. 5K). Additionally, there was a 57% decrease in branch point density (branch points/tissue area) in the submucosal lymphatics of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (173 +/− 45 branch points/mm2) mice compared to WT (402 +/− 38 branch points/mm2) mice, a 55% decrease compared to Foxc2 +/− (383 +/− 19 branch points/mm2) mice, and a 58% decrease compared to Cx37 −/− (413 +/− 31 branch points/mm2) mice (Fig. 5L). Regions of the proximal small intestine were the most affected, with distal segments of the small intestine and large intestine showing less morphological irregularity. We calculated the percentage of tissue that was within a particular distance of a lymphatic vessel, and the majority of the parenchyma in the small intestine was closer to a given vessel in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice compared to WT, Foxc2 +/−, and Cx37 −/− mice (Fig. S3). Overall, the distribution and patterning of the submucosal lymphatic vasculature in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice was significantly altered, which likely translated to postnatal lymphatic functional deficits in the intestine.

Localized regions of intense Vegfr3 immunostaining readily identified the locations of developing lacteals in E18.5 whole-mount stained intestines (Fig. 6A–H), which allowed us to quantify the lacteal density (lacteals/tissue area) as well as measure their length. We saw lacteals associated with nearly all the villi we examined, and the lacteal density for WT (107 +/−10 lacteals/mm2), Foxc2 +/− (101 +/− 13 lacteals/mm2), Cx37 −/− (108 +/− 7 lacteals/mm2), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (87 +/− 3 lacteals/mm2) mice were similar (Fig. 6I). However, the lacteals of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− samples were often wider at the base and 38% shorter (101.8 +/− 13.1 µm) compared to WT (165.1 +/− 12.0 µm), 40% shorter compared to Foxc2 +/− (169.0 +/− 2.6 µm), and 38% shorter compared to Cx37 −/− (163.3 +/− 16.8 µm) samples (Fig. 6J).

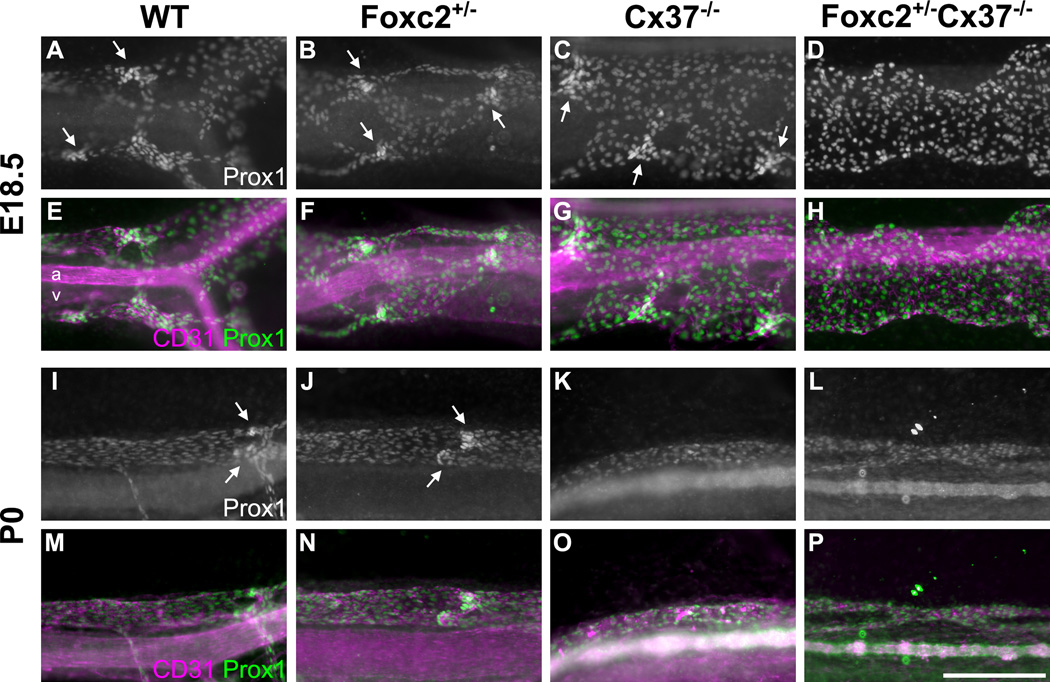

We evaluated the mesenteric lymphatics across different genotypes at E18.5 (Fig. 7A–H) and P0 (Fig. 7I–P). By E18.5 in WT mice, the mesenteric lymph vasculature has formed a fine, valved network of vessels with even caliber (Fig. 7A,E). In contrast, most of the mesenteric lymph vessels of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were hyperplastic (Fig. 7D,H). Some of the enlarged vessels were relatively even in caliber, while others were cavernous with highly irregular caliber. These cavernous segments had a “string of beads” appearance in some instances. The mesenteric lymphatics also showed regional variability in the severity of enlargement, with vessels of relatively normal caliber in some lymphatics primarily near the intestinal-mesenteric border. The lymphatic developmental anomalies of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice within the mesenteric lymphatics are therefore similar to those seen in the submucosal lymphatics of the intestine, namely a gross enlargement of vessels and the formation of an erratic, plexiform vasculature.

Figure 7.

Mesenteric lymph vessels of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice lack valves and are dilated at E18.5. Prox1 whole-mount immunostaining highlights lymphatic vessels of the mesentery in WT (A), Foxc2 +/− (B), Cx37 −/− (C), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (D) mice at E18.5. Corresponding Prox1 (green) and CD31 (magenta) color composites are shown for WT (E), Foxc2 +/− (F), Cx37 −/−(G), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (H) mesenteries at E18.5. (I–L) Prox1 whole-mount immunostaining at P0 for WT (I), Foxc2 +/− (J), Cx37 −/− (K), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (L) mesenteries. (M–P) Prox1 (green) and CD31 (magenta) color composites are shown for WT (M), Foxc2 +/− (N), Cx37 −/− (O), and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (P) mesenteries at P0. Arrows denote lymphatic valve forming areas; note that none are present in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice. Scale bar: (A–P) 200 µm.

Normally, intraluminal valves begin to form in the mesenteric lymphatic collecting vessels around E15.5 and by E18.5 they are abundant (Kim et al., 2007). The mesenteric lymph vessels in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5 (Fig. 7D,H) and P0 (Fig. 7L,P) completely lacked valves, and we did not see localized Prox1 upregulation that typically demarcates valve-forming areas. Unlike the regional variability in overall lymphatic vessel architecture, the absence of valves was uniformly observed in these animals. In contrast, mesenteric valves were still present in Foxc2 +/− mice at E18.5, and their relative abundance appeared similar to WT. However, evidence for apparently incompetent lymphatic valves has been documented in Foxc2 +/− mice, using the Evans blue dye (EBD) assay (Kriederman et al., 2003). Developing mesenteric valves were also noted in Cx37 −/− mesentery at E18.5; a reduction in the number of these valves has been previously documented for Cx37 −/− mice (Kanady et al., 2011; Sabine et al., 2012). Our results demonstrate that mesenteric lymphatic valve development fails to initiate or is arrested in the earliest stages when mice have deficiencies in both Foxc2 and Cx37.

Loss of Cx37 increases the mitotic activity of LECs in the mesentery of E18.5 mice

We previously reported that Cx37 −/− embryos develop enlarged jugular lymph sacs at E13.5 (Kanady et al., 2011). Given the severe enlargement of lymphatics in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, we investigated LEC proliferation in the mesenteric lymph vessels of Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5. Histone H3 is a protein that is phosphorylated nearly exclusively during M-phase, and has thus been characterized as a “true” mitotic marker (Hendzel et al., 1997; Li et al., 2005; Tapia et al., 2006). Whole-mount immunostaining of E18.5 mesenteries with antibodies directed against phosphorylated Histone H3 (pHH3) revealed that the percentage of mitotically active LECs from Cx37 −/− mice was 61% higher (20.00 +/− 0.53%) compared to WT mice (12.46 +/− 0.23%) (Fig. 8A–I). Thus, the loss of Cx37 results in increased growth of lymphatic vessels by affecting mitotic activity.

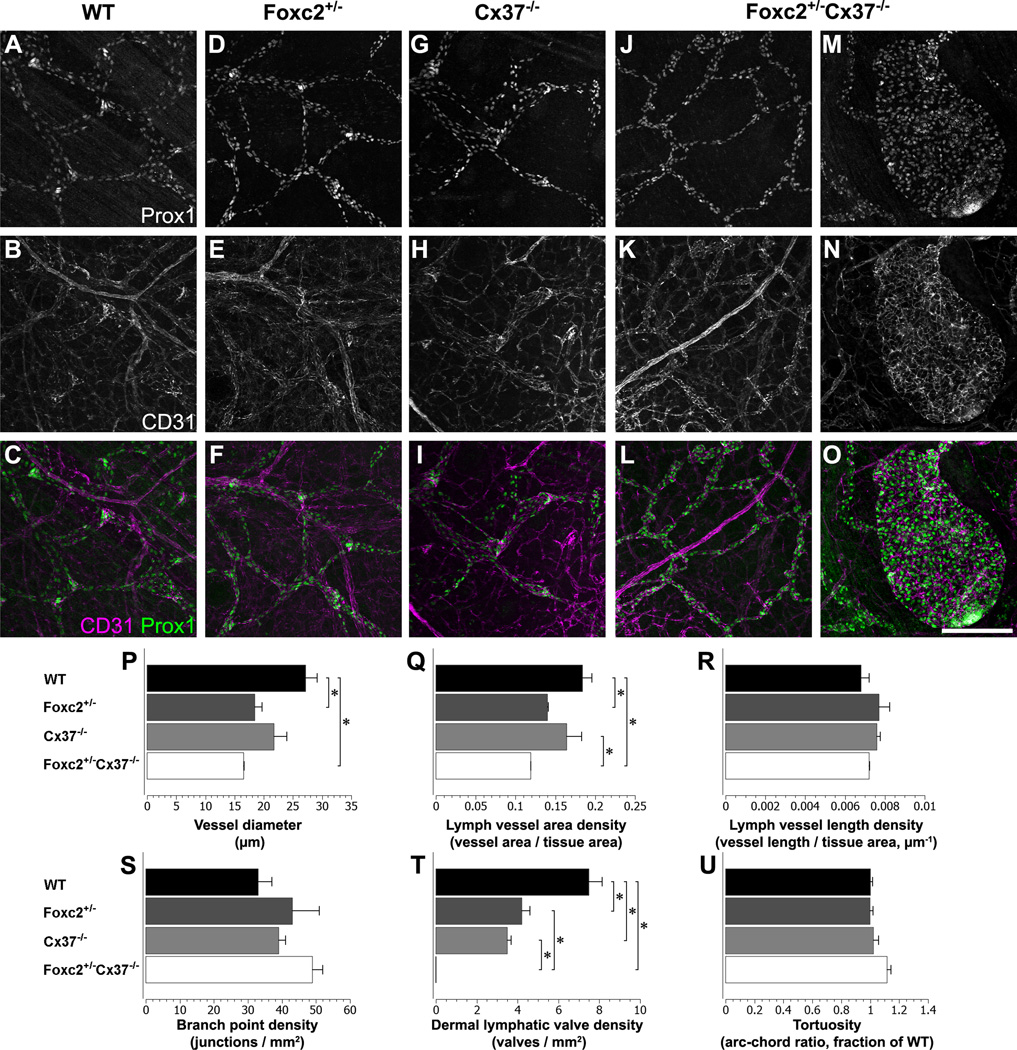

The dermal lymphatics of Foxc2 +/−Cx37−/− mice have abnormal patterning, lack lymphatic valves, and form lymphangiomas

Whole-mount preparations of skin from E18.5 WT, Foxc2 +/−, Cx37 −/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were immunostained for Prox1 and CD31 (also known as platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1, PECAM-1) in order to assess lymphatic development (Fig. 9A–O) and quantify vascular parameters (Fig. 9P–U). The lymphatic network of the skin in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− embryos was composed of fine vessels, smaller in caliber than WT, Foxc2 +/−, and Cx37 −/− samples, which was a stark contrast to the severe enlargement of the lymphatic vessels of the intestinal and mesenteric lymph vessels. However, lymphatic vessels in some regions of the skin in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were hyperplastic. The mean diameter of dermal lymph vessels was 39% smaller in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice (16.6 +/− 0.1 µm) compared to WT (27.2 +/− 2.0 µm) mice, and Foxc2 +/−(18.2 +/− 1.3 µm) mice had a mean lymph vessel diameter that was 33% smaller compared to WT mice (Fig. 9P). The dermal lymphatic vascular fraction in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (0.119 +/− 0.000) mice was 35% less than WT (0.184 +/− 0.012) and 27% less than Cx37 −/− (0.164 +/− 0.019) mice (Fig. 9Q). Lacunarity (which evaluates vascular structural nonuniformity), was significantly higher in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− (0.60 +/− 0.03) samples compared to WT (0.41 +/− 0.04), indicating that dermal lymph vessels in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice have less homogeneous lymphatic coverage in the skin. We also measured tortuosity of lymph vessel segments, branch point density, and lymph vessel length density, but found no differences in these measures between genotypes. Together, these data demonstrate that the dermal lymph vessels in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were thinner overall (contributing to a lower lymph vascular area density) and had an uneven distribution throughout the skin.

Figure 9.

The dermal lymphatics of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5 lack valves, are smaller in caliber, and can develop structures resembling cystic lymphangiomas. Prox1 immunolabeling (A, D, G, J, M) and CD31 immunolabeling (B, E, H, K, N) for WT, Foxc2 +/−, Cx37 −/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− dermal lymphatic vessels. (C, F, I, L, O) Color composites of corresponding panels (A, D, G, J, M) for Prox1 (green) and (B, E, H, K, N) for CD31 (magenta). (M–O) Structure resembling a cystic lymphangioma in a Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− skin sample. (P–U) Dermal lymphatic vascular network quantitation. (P) Dermal lymph vessel diameter of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice was significantly smaller than WT mice. Dermal lymph vessel diameter of Foxc2 +/− mice was also significantly lower than WT. (Q) Dermal lymph vessel area density of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice was significantly lower than WT and Cx37 −/− mice. Additionally, lymph vessel area density of Foxc2 +/− mice was significantly lower than WT. (T) There were significantly fewer dermal lymph valves in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice compared to WT, Foxc2 +/−, and Cx37 −/− mice. There was also a significant reduction in dermal lymph valves in Foxc2 +/− and Cx37 −/− mice compared to WT. There were no differences in dermal lymph vessel length density (R), branch point density (S), or vessel tortuosity (U) between genotypes. Scale bar: (A–O) 200 µm. Six 10x fields were evaluated per embryo, n = 3 for each genotype. Values are presented as means, with error bars indicating standard error of the mean. Asterisks, p < 0.05.

Lymphatic valves were completely absent from both the ventral and dorsal skin of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− samples, and localized regions of Prox1 upregulation were not evident in these animals (Fig. 9J–L). There were also fewer lymphatic valves in the skin of Foxc2 +/− (4.2 +/− 0.4 valves/mm2) and Cx37 −/− (3.5 +/− 0.2 valves/mm2) mice compared to WT (7.5 +/− 0.6 valves/mm2) mice (Fig. 9T). Interestingly, there was regionally skewed reduction in valves/valve-forming regions in Cx37 −/− mice, with significantly decreased valve density in the dorsal skin (2.0 +/− 0.1 valves/mm2) compared to the ventral skin (5.1 +/− 0.5 valves/mm2). Thus, similar to mesenteric lymph vessels, there was valve agenesis in the dermal lymphatic network of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5.

Curiously, despite the reduction in overall dermal lymphatic vessel caliber and vascular fraction in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5, we found that the ends of some lymphatic capillaries had grown extremely large (to approximately 200 – 500 microns in diameter). The growths were Prox1 positive, variable in size, and highly cellular (Fig. 9M). We found them in various locations within the skin – both ventral and dorsal. CD31 staining tended to be stronger in these structures compared to surrounding lymphatic vessels (Fig. 9N). These results show that hemizygous loss of Foxc2 combined with the loss of both alleles of Cx37 in mice promotes the formation of structures that resemble cystic lymphangiomas.

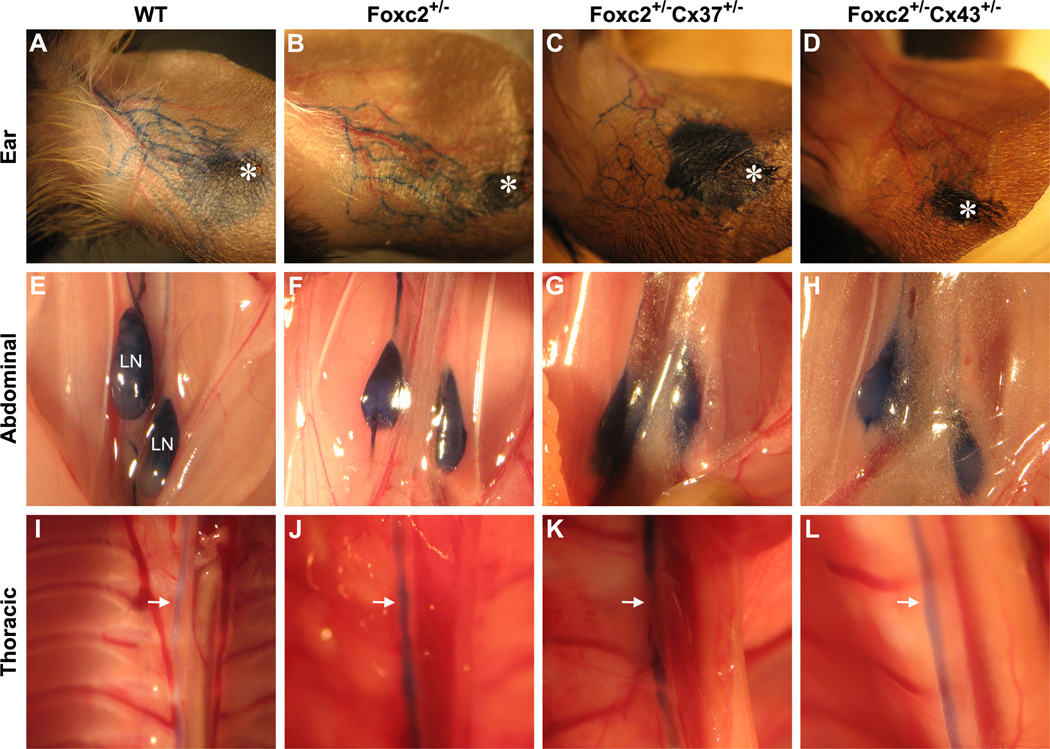

Foxc2+/−Cx37+/− adult mice display similar lymphatic drainage patterns compared to Foxc2+/− mice

Lymphatic drainage and function have been previously evaluated in Foxc2 +/− adult mice by using EBD lymphangiography, which revealed generalized lymphatic vessel and lymph node hyperplasia in those animals (Kriederman et al., 2003). In our past analysis of Cx37 −/− adult mice, most had EBD reflux in the lymph vessels of the skin and the intercostal lymphatics, which suggested insufficient valve function and an impairment in maintaining unidirectional lymph flow (Kanady et al., 2011). Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice die perinatally, thus we were unable to assess adults of this genotype. However, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− are viable and EBD lymphangiography was performed on adult mice of this genotype. Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− adult mice (3 to 6 months of age) exhibited similar EBD drainage patterns in the ear (Fig. 10A–C), lumbar lymph nodes (Fig. 10E–G), and thoracic duct (Fig. 10I–K) compared to Foxc2 +/− mice. Reflux of EBD was not found, suggesting that the presence of a single copy of Cx37 is sufficient to largely preserve valve function in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− mice. Since Cx43 is necessary for lymphatic valve development (Kanady et al., 2011) and results from ChIP-chip studies suggest that a Foxc2-NFATc1 binding site is located near the Cx43 gene (Norrmen et al., 2009), we also evaluated Foxc2 +/−Cx43 +/− mice. No differences were found in Foxc2 +/−Cx43 +/− mice (Fig. 10D,H,L) compared to Foxc2 +/− mice.

Figure 10.

Evans blue dye (EBD) lymphangiography of WT, Foxc2 +/−, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx43 +/− adult mice. EBD drainage patterns in the ear (A–D), abdominal cavity (E–H), and thoracic cavity (I–L). EBD readily filled the lymphatics of ear (injection site denoted by the asterisk), the lumbar lymph nodes (E-H, labeled “LN”), and thoracic duct (denoted by arrows in I-L) of WT, Foxc2 +/−, Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/−, and Foxc2 +/−Cx43 +/− mice. No obstructions or reflux of EBD were found in the areas examined.

Discussion

Foxc2 and Cx37 involvement in bone formation

Several lymphedema-associated disorders are accompanied by craniofacial defects (Northup et al., 2003). Lymphedema in utero may cause these bone malformations by impairing the migration of tissues during embryonic development (Witt et al., 1987). However, craniofacial abnormalities can present from birth in humans with hereditary lymphedema, even when lymphedema is of late-childhood or adolescent onset (Fang et al., 2000). In the animals we examined, craniofacial differences manifested both in the presence (in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice) and absence (in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− mice) of lymphedema in utero. Thus, lymphedema-dependent and lymphedema-independent effects may influence bone formation in this mouse model. Indeed, both Foxc2 (Park et al., 2011) and Cx37 (Pacheco-Costa et al., 2014) are expressed by osteogenic cells, and mice with separate genetic deletion of these proteins have defects in skeletogenesis and altered structural bone characteristics (Iida et al., 1997; Pacheco-Costa et al., 2014). At present, it is unclear whether Foxc2 and Cx37 share molecular pathways in bone development, but the craniofacial features that are exhibited in mice only when deficiencies in Foxc2 and Cx37 are combined are consistent with this idea.

Foxc2 and Cx37 in intestinal lymphangiogenesis

Remarkably, lymphangiectasia in the intestine of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice was mainly localized to the proximal small intestine, suggesting that deficiencies in Foxc2 and Cx37 have a greater influence on mid-gut derived lymphatic tissues compared to other areas. Intestinal and mesenteric lymph vessels in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were located alongside blood vessels, evidence that basic guidance events during the establishment of the primary lymphatic network were maintained. However, profound dilation and decreased branch point density of intestinal lymphatics indicated defects in lymphangiogenesis and vessel remodeling (sprouting, branching and/or anastomosis). Increased LEC proliferation likely contributed to the enlargement of lymph vessels, as evidenced by greater numbers of mitotic mesenteric LECs in Cx37 −/− mice. This finding is consistent with studies reporting that Cx37 is growth suppressive (Burt et al., 2008; Fang et al., 2011). The exact mechanism by which Cx37 controls growth is unknown; however, its ability to form a channel capable of supporting intercellular, transmembrane, and intracellular signaling is necessary for growth suppression in cell culture settings (Good et al., 2014).

Lacteals form part of the mucosal lymphatic network within the small intestine, which develops secondarily to the submucosal lymphatic network (Heuer, 1909). The lacteals of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice were considerably shorter, another shortcoming of the system to properly remodel the submucosal lymphatic network. Disruption of lacteal growth was also demonstrated in mice lacking Angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2, a vascular growth factor), resulting in abnormally short lacteals or often their absence (Gale et al., 2002). Thus, our results place Foxc2 and Cx37 alongside Ang-2 on a brief list of factors known to affect lacteal growth.

Clinically, intestinal lymphangiectasia can give rise to chronic diarrhea, loss of serum proteins into the intestinal lumen (protein-losing enteropathy), and impaired absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins (Vignes and Bellanger, 2008). Coupled with defective lacteal development, intestinal loss of serum proteins and nutrient malabsorption during critical postnatal periods may have contributed to postnatal death in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice.

Lymph-blood mixing

The presence of blood in discrete regions of the dermal, intestinal, and pericardial lymphatics late in embryonic development might be explained by inappropriate anastomoses between the lymphatic and blood vasculature in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, but we did not find morphological evidence for this phenomenon. However, a more exhaustive histological analysis may be required to rule out this possibility. Alternatively, lymphovenous valve defects may be a factor in lymph-blood mixing. Incidentally, while accumulation of blood within lymph vessels may be partly responsible for their dilation in each of these regions, enlargement of vessels in areas devoid of lymph-blood mixing argues that disturbed lymphangiogenesis was a major cause of lymphangiectasia.

Foxc2, Cx37, and Cx43 in lymphatic valve development

Based on data showing that Cx45 in cardiac endothelium was necessary for activation of NFATc1 with epithelial-mesenchymal transformation during cardiac valve morphogenesis, it was suggested that connexins were involved in calcineurin/NFATc1 signaling (Kumai et al., 2000). Oscillatory shear stress experiments on LECs in culture have shown that Cx37 is also required for coordinated activation of NFATc1 (Sabine et al., 2012). Foxc2 binding sites within the genome have been identified in proximity to predicted NFATc1 sites, and luciferase reporter assays using fragments from some of those identified regions showed synergistic activation in the presence of both Foxc2 and NFATc1 (Norrmen et al., 2009). Additionally, lymphatic Cx37 gene expression is greatly reduced in the absence of Foxc2 and a partial genetic interaction between Foxc2 and Cx37 was suggested by increased immature valves in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 +/− mice (Kanady et al., 2011; Sabine et al., 2012). These findings have coalesced into a proposed model whereby mechanotransduction, Prox1, and Foxc2 are involved in the control of Cx37 and calcineurin/NFAT signaling in lymphatic valve development (Sabine et al., 2012).

Our data concerning the absence of intraluminal valves in the lymphatic collectors of the skin and mesentery of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice at E18.5 are consistent with the model above. Connexin-based calcium signaling has been demonstrated to occur via intercellular diffusion of Ca2+ or inositol trisphosphate through gap junctions (Boitano et al., 1992; Giaume and Venance, 1998) or by purinergic nucleotide-based paracrine mechanisms via hemichannels (Ponsaerts et al., 2010). Thus, one possible scenario in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice is that the loss of Cx37 represents a reduced capacity for connexin-mediated calcium signaling in response to mechanical events, leading to decreased activation of calcineurin and lower levels of activated NFATc1. Coupled with a prima facie reduction in the levels of Foxc2 in Foxc2 +/− mice, a subsequent decrease in Foxc2-NFATc1 cooperative regulation of gene expression might be expected in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice.

The phenotype of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice affords new insights into the relation of these two proteins to lymphatic valve development. Since Foxc2 +/− and Cx37 −/− mice each have approximately a 50% reduction in the number of developing lymphatic valves in the skin at E18.5, the complete loss of valves in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− embryos points to a synergistic effect of Foxc2 and Cx37 on valve formation. Moreover, there was no evidence of localized upregulation of Prox1 (demarcating valve-forming areas) during lymph vessel remodeling in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, indicating that valve formation failed to initiate or was arrested at very early stages. On the other hand, mice lacking just Cx37 do show localized, circumferential upregulation of Prox1 during early lymphatic valve genesis, but often have defective valve maturation (Kanady et al., 2011; Sabine et al., 2012). Therefore, in the absence of Cx37, having half the genetic complement of Foxc2 is not sufficient to initiate the valve formation program. These data suggest that the function of Foxc2 (or that of a protein that it functionally interacts with, such as NFATc1) depends on Cx37 expression during lymphatic valvulogenesis.

Foxc2 and Cx37 in dermal lymphangiogenesis

The morphological changes in the dermal lymphatic network of Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice (overall reduction in vessel caliber and lower density of coverage) run counter to those of the collecting vessels of the mesentery and intestine (increased vessel caliber and higher area density). Cx37 is expressed to a lesser extent in dermal lymphatic capillaries (Kanady et al., 2011) compared to lymphatic collecting vessels, and this difference may reflect a functionally distinct role of Cx37 in certain vessel types. However, consistent with vessel enlargement seen in the mesentery and intestine, portions of the dermal lymphatic network were also enlarged and structures resembling lymphangiomas developed in some of these mice.

The basis of the differing growth/remodeling effects of Foxc2 and Cx37 on specific levels of the lymphatic vascular hierarchy is unclear. One possible explanation may be related to LEC versus non-LEC connexin expression and function. Cx37 is expressed by macrophages where it is involved in modulating ATP-dependent adhesion (Wong et al., 2006) and these cells play a role in defining dermal lymphatic vascular caliber by limiting LEC proliferation (Gordon et al., 2010). Therefore, the loss of Cx37 in macrophages may be partly responsible for the changes in lymphatic vascular caliber seen in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice. In addition, recent lineage tracing experiments have provided evidence for a non-venous origin of portions of the dermal (Martinez-Corral et al., 2015) and mesenteric (Stanczuk et al., 2015) lymphatic vasculature in mice, through a process of lymphvasculogenesis. Hence, another possible explanation for lymphatic-bed specific changes in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice is differing functions for Foxc2 and Cx37 in lymphvasculogenesis versus lymphangiogenesis.

Relating Foxc2+/−Cx37−/− mice and hereditary lymphatic disorders in humans

Certain phenotypic abnormalities in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice can also be seen in a number of lymphedema-associated and hereditary lymphatic disorders in humans. For example, von Recklinghausen, Turner, Noonan, Klippel-Trenaunay, and Hennekam syndromes are all associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia (Vignes and Bellanger, 2008). Biopsy samples from the duodenum of patients with intestinal lymphangiectasia showed more than a five-fold reduction in mRNA expression levels of FOXC2 compared to control (Hokari et al., 2008). While CX37 mRNA expression was not assessed in those patients, we would expect similar reductions given previous data correlating Foxc2 and Cx37 expression levels in mice (Kanady et al., 2011; Sabine et al., 2012). Thus, examining these proteins together may benefit future studies attempting to identify the etiology of lymphatic disorders (particularly involving lymphangiectasia) in humans.

Summary

This study shows that both Foxc2 and Cx37 are necessary for lymphangiogenesis to progress correctly. A number of new lymphatic defects manifest when hemizygous deletion of Foxc2 is combined with complete ablation of Cx37 (compared to those resulting from their individual loss). Establishment of the primary lymphatic plexus occurs in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice, but its remodeling into a functional vascular network replete with lymphatic valves is severely impaired. Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice also have dysmorphic cranial development, indicating that Foxc2 and Cx37 may have shared domains of control in bone development as well. The abnormalities that occur in Foxc2 +/−Cx37 −/− mice are similar to the spectrum of symptoms seen in some lymphedema-associated disorders.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Lymphangiectasia and valve agenesis result from combined Foxc2 and Cx37 deficiencies.

Foxc2+/−Cx37−/− mice: lower dermal lymphatic caliber, but with isolated lymphangiomas.

Foxc2+/−Cx37−/− mice have shorter lacteals, but they are unchanged in total number.

Foxc2+/−Cx37−/− mice have craniofacial/lymphatic defects similar to human diseases.

Foxc2 and Cx37 are necessary for normal lymphatic growth and remodeling.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank José Ek-Vitorín for numerous enlightening discussions regarding this work and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL64232 (to A.M. Simon) and T32-HL007249 (to J.M. Burt, supporting J.D. Kanady).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

John D. Kanady, Email: jkanady@email.arizona.edu.

Stephanie J. Munger, Email: sjmunger@email.arizona.edu.

Marlys H. Witte, Email: lymph@email.arizona.edu.

Alexander M. Simon, Email: amsimon@email.arizona.edu.

References

- Alexander JS, Ganta VC, Jordan PA, Witte MH. Gastrointestinal lymphatics in health and disease. Pathophysiology. 2010;17:315–335. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arganda-Carreras I, Fernández-González R, Muñoz-Barrutia A, Ortiz-De-Solorzano C. 3D reconstruction of histological sections: Application to mammary gland tissue. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2010;73:1019–1029. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano S, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular propagation of calcium waves mediated by inositol trisphosphate. Science. 1992;258:292–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1411526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brice G, Ostergaard P, Jeffery S, Gordon K, Mortimer PS, Mansour S. A novel mutation in GJA1 causing oculodentodigital syndrome and primary lymphoedema in a three generation family. Clin. Genet. 2013;84:378–381. doi: 10.1111/cge.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt JM, Nelson TK, Simon AM, Fang JS. Connexin 37 profoundly slows cell cycle progression in rat insulinoma cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1103–C1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.299.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Dagenais SL, Erickson RP, Arlt MF, Glynn MW, Gorski JL, Seaver LH, Glover TW. Mutations in FOXC2 (MFH-1), a forkhead family transcription factor, are responsible for the hereditary lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:1382–1388. doi: 10.1086/316915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang JS, Angelov SN, Simon AM, Burt JM. Cx37 deletion enhances vascular growth and facilitates ischemic limb recovery. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2011;301:H1872–H1881. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00683.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell RE, Baty CJ, Kimak MA, Karlsson JM, Lawrence EC, Franke-Snyder M, Meriney SD, Feingold E, Finegold DN. GJC2 missense mutations cause human lymphedema. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NW, Thurston G, Hackett SF, Renard R, Wang Q, McClain J, Martin C, Witte C, Witte MH, Jackson D, Suri C, Campochiaro PA, Wiegand SJ, Yancopoulos GD. Angiopoietin-2 is required for postnatal angiogenesis and lymphatic patterning, and only the latter role is rescued by Angiopoietin-1. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaume C, Venance L. Intercellular calcium signaling and gap junctional communication in astrocytes. Glia. 1998;24:50–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good ME, Ek-Vitorín JF, Burt JM. Structural determinants and proliferative consequences of connexin 37 hemichannel function in insulinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:30379–30386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.583054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon EJ, Rao S, Pollard JW, Nutt SL, Lang RA, Harvey NL. Macrophages define dermal lymphatic vessel calibre during development by regulating lymphatic endothelial cell proliferation. Development. 2010;137:3899–3910. doi: 10.1242/dev.050021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel MJ, Wei Y, Mancini MA, Van Hooser A, Ranalli T, Brinkley BR, Bazett-Jones DP, Allis CD. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma. 1997;106:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s004120050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer G. The development of the lymphatics in the small intestine of the pig. Am. J. Anat. 1909;9:93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hokari R, Kitagawa N, Watanabe C, Komoto S, Kurihara C, Okada Y, Kawaguchi A, Nagao S, Hibi T, Miura S. Changes in regulatory molecules for lymphangiogenesis in intestinal lymphangiectasia with enteric protein loss. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008;23:e88–e95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida K, Koseki H, Kakinuma H, Kato N, Mizutani-Koseki Y, Ohuchi H, Yoshioka H, Noji S, Kawamura K, Kataoka Y, Ueno F, Taniguchi M, Yoshida N, Sugiyama T, Miura N. Essential roles of the winged helix transcription factor MFH-1 in aortic arch patterning and skeletogenesis. Development. 1997;124:4627–4638. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaipainen A, Korhonen J, Mustonen T, van Hinsbergh VW, Fang GH, Dumont D, Breitman M, Alitalo K. Expression of the fms-like tyrosine kinase 4 gene becomes restricted to lymphatic endothelium during development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:3566–3570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanady JD, Dellinger MT, Munger SJ, Witte MH, Simon AM. Connexin37 and Connexin43 deficiencies in mice disrupt lymphatic valve development and result in lymphatic disorders including lymphedema and chylothorax. Dev. Biol. 2011;354:253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen MJ, Haiko P, Sainio K, Partanen J, Taipale J, Petrova TV, Jeltsch M, Jackson DG, Talikka M, Rauvala H, Betsholtz C, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor C is required for sprouting of the first lymphatic vessels from embryonic veins. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:74–80. doi: 10.1038/ni1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KE, Sung H-K, Koh GY. Lymphatic development in mouse small intestine. Dev. Dyn. An Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2007;236:2020–2025. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltowska K, Betterman KL, Harvey NL, Hogan BM. Getting out and about: the emergence and morphogenesis of the vertebrate lymphatic vasculature. Development. 2013;140:1857–1870. doi: 10.1242/dev.089565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriederman BM, Myloyde TL, Witte MH, Dagenais SL, Witte CL, Rennels M, Bernas MJ, Lynch MT, Erickson RP, Caulder MS, Miura N, Jackson D, Brooks BP, Glover TW. FOXC2 haploinsufficient mice are a model for human autosomal dominant lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1179–1185. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumai M, Nishii K, Nakamura K, Takeda N, Suzuki M, Shibata Y. Loss of connexin45 causes a cushion defect in early cardiogenesis. Development. 2000;127:3501–3512. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.16.3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DW, Yang Q, Chen JT, Zhou H, Liu RM, Huang XT. Dynamic distribution of Ser-10 phosphorylated histone H3 in cytoplasm of MCF-7 and CHO cells during mitosis. Cell Res. 2005;15:120–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longair MH, Baker DA, Armstrong JD. Simple Neurite Tracer: open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2453–2454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Corral I, Ulvmar M, Stanczuk L, Tatin F, Kizhatil K, John SW, Alitalo K, Ortega S, Makinen T. Non-Venous Origin of Dermal Lymphatic Vasculature. Circ. Res. CIRCRESAHA. 2015;116:306170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger SJ, Kanady JD, Simon AM. Absence of venous valves in mice lacking Connexin37. Dev. Biol. 2013;373:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrmen C, Ivanov KI, Cheng J, Zangger N, Delorenzi M, Jaquet M, Miura N, Puolakkainen P, Horsley V, Hu J, Augustin HG, Yla-Herttuala S, Alitalo K, Petrova TV. FOXC2 controls formation and maturation of lymphatic collecting vessels through cooperation with NFATc1. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:439–457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup KA, Witte MH, Witte CL. Syndromic classification of hereditary lymphedema. Lymphology. 2003;36:162–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Costa R, Hassan I, Reginato RD, Davis HM, Bruzzaniti A, Allen MR, Plotkin LI. High Bone Mass in Mice Lacking Cx37 Due to Defective Osteoclast Differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;M113:529735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.529735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Gadi J, Cho K-W, Kim KJ, Kim SH, Jung H-S, Lim S-K. The forkhead transcription factor Foxc2 promotes osteoblastogenesis via up-regulation of integrin β1 expression. Bone. 2011;49:428–438. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova TV, Karpanen T, Norrmén C, Mellor R, Tamakoshi T, Finegold D, Ferrell R, Kerjaschki D, Mortimer P, Ylä-Herttuala S, Miura N, Alitalo K. Defective valves and abnormal mural cell recruitment underlie lymphatic vascular failure in lymphedema distichiasis. Nat. Med. 2004;10:974–981. doi: 10.1038/nm1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponsaerts R, De Vuyst E, Retamal M, D’hondt C, Vermeire D, Wang N, De Smedt H, Zimmermann P, Himpens B, Vereecke J, Leybaert L, Bultynck G. Intramolecular loop/tail interactions are essential for connexin 43-hemichannel activity. FASEB J. 2010;24:4378–4395. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaume AG, de Sousa PA, Kulkarni S, Langille BL, Zhu D, Davies TC, Juneja SC, Kidder GM, Rossant J. Cardiac malformation in neonatal mice lacking connexin43. Science. 1995;267:1831–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.7892609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabine A, Agalarov Y, Maby-El Hajjami H, Jaquet M, Hägerling R, Pollmann C, Bebber D, Pfenniger A, Miura N, Dormond O, Calmes J-M, Adams RH, Mäkinen T, Kiefer F, Kwak BR, Petrova TV. Mechanotransduction, PROX1, and FOXC2 cooperate to control connexin37 and calcineurin during lymphatic-valve formation. Dev. Cell. 2012;22:430–445. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda H, Bernas MJ, Witte MH. Dysmorphogenesis of lymph nodes in Foxc2 haploinsufficient mice. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2011;135:603–613. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0819-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholto-Douglas-Vernon C, Bell R, Brice G, Mansour S, Sarfarazi M, Child AH, Smith A, Mellor R, Burnand K, Mortimer P, Jeffery S. Lymphoedema-distichiasis and FOXC2: unreported mutations, de novo mutation estimate, families without coding mutations. Hum. Genet. 2005;117:238–242. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AM, Chen H, Jackson CL. Cx37 and Cx43 localize to zona pellucida in mouse ovarian follicles. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2006;13:61–77. doi: 10.1080/15419060600631748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon AM, Goodenough DA, Li E, Paul DL. Female infertility in mice lacking connexin 37. Nature. 1997;385:525–529. doi: 10.1038/385525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanczuk L, Martinez-Corral I, Ulvmar MH, Zhang Y, Laviña B, Fruttiger M, Adams RH, Saur D, Betsholtz C, Ortega S, Alitalo K, Graupera M, Mäkinen T. cKit Lineage Hemogenic Endothelium-Derived Cells Contribute to Mesenteric Lymphatic Vessels. Cell Rep. 2015;10:1708–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia C, Kutzner H, Mentzel T, Savic S, Baumhoer D, Glatz K. Two mitosis-specific antibodies, MPM-2 and phospho-histone H3 (Ser28), allow rapid and precise determination of mitotic activity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006;30:83–89. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000183572.94140.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease) Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2008;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Oliver G. Current views on the function of the lymphatic vasculature in health and disease. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2115–2126. doi: 10.1101/gad.1955910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnier GE, Hargett L, Hogan BL. The winged helix transcription factor MFH1 is required for proliferation and patterning of paraxial mesoderm in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1997;11:926–940. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt DR, Hoyme HE, Zonana J, Manchester DK, Fryns JP, Stevenson JG, Curry CJ, Hall JG. Lymphedema in Noonan syndrome: clues to pathogenesis and prenatal diagnosis and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1987;27:841–856. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte MH, Erickson RP, Khalil M, Dellinger M, Bernas M, Grogan T, Nitta H, Feng J, Duggan D, Witte CL. Lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome without FOXC2 mutation: evidence for chromosome 16 duplication upstream of FOXC2. Lymphology. 2009;42:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CW, Christen T, Roth I, Chadjichristos CE, Derouette J-P, Foglia BF, Chanson M, Goodenough DA, Kwak BR. Connexin37 protects against atherosclerosis by regulating monocyte adhesion. Nat. Med. 2006;12:950–954. doi: 10.1038/nm1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zudaire E, Gambardella L, Kurcz C, Vermeren S. A computational tool for quantitative analysis of vascular networks. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.