Abstract

Objective

Liver disease is a potential complication from using dietary supplements. This study investigated an outbreak of non-viral liver disease associated with the use of OxyELITE ProTM, a dietary supplement used for weight loss and/or muscle building.

Methods

Illness details were ascertained from MedWatch reports submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) describing consumers who ingested OxyELITE Pro alone or in combination with other dietary supplements. FDA's Forensic Chemistry Center analyzed samples of OxyELITE Pro.

Results

From February 2012 to February 2014, FDA received 114 reports of adverse events of all kinds involving consumers who ingested OxyELITE Pro. The onset of illness for the first report was December 2010 and for the last report was January 2014. Thirty-three states, two foreign nations, and Puerto Rico submitted reports. Fifty-five of the reports (48%) described liver disease in the absence of viral infection, gallbladder disease, autoimmune disease, or other known causes of liver damage. A total of 33 (60%) of these patients were hospitalized, and three underwent liver transplantation. In early 2013, OxyELITE Pro products entered the market with a formulation distinct from products sold previously. The new formulation replaced 1,3-dimethylamylamine with aegeline. However, the manufacturer failed to submit to FDA a required “new dietary ingredient” notice for the use of aegeline in OxyELITE Pro products. Laboratory analysis identified no drugs, poisons, pharmaceuticals, toxic metals, usnic acid, N-Nitroso-fenfluramine, pyrrolizidine alkaloids, aristocholic acid, or phenethylamines in the products.

Conclusions

Vigilant surveillance is required for adverse events linked to the use of dietary supplements.

In the United States, surveillance for infectious and chronic diseases is well established,1–3 as is surveillance for adverse events associated with the use of drugs, biologics, and medical devices regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).4–6 A key instrument used for reporting adverse events linked to FDA-regulated products is MedWatch, a program launched in 1993.7,8

Surveillance of adverse events linked to dietary supplements is challenging because of the plethora of products used, the diversity of ingredients present, the heterogeneity of adverse events that may ensue, the difficulty of recognizing a link between adverse events and the use of a specific dietary supplement, and a low incidence of adverse effects that may occur following the use of certain supplements. Adverse events linked to dietary supplements may be reported to disparate authorities or surveillance systems, including poison control centers, local or state health departments, syndrome-specific surveillance entities (e.g., the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network9), or to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Department of Defense, or FDA. FDA encourages health-care professionals, patients, and consumers to report adverse events or problems linked to dietary supplements in one of several ways. MedWatch forms may be downloaded8 and faxed (1-800-332-0178) or mailed to FDA using a postage-paid business reply form provided online.8 Alternatively, MedWatch reports may be submitted online at either of two websites.7,10

On September 16, 2013, health-care providers at the sole transplant medical center in Hawaii notified FDA of seven previously healthy adults who developed acute or fulminant non-viral hepatitis after ingesting OxyELITE Pro” (USPlabs, LLC, Dallas, Texas), a dietary supplement used for weight loss and/or muscle building. Henceforth, FDA began communicating regularly with the Hawaii State Department of Health (HI DOH) and CDC, which HI DOH had invited to assist with an investigation of the illnesses.11 During the federal government shutdown from October 1–16, 2013, FDA initiated a laboratory analysis of OxyELITE Pro products obtained from patients and retail outlets in Hawaii, conducted a traceback of OxyELITE Pro products purchased by case patients in Hawaii, and reviewed 21 medical records submitted by the HI DOH. In this article, we describe regulatory actions taken by FDA to remove the dietary supplement from commerce and the key roles MedWatch played in identifying OxyELITE Pro-associated cases in the continental United States.

METHODS

FDA investigation—early events

To FDA's knowledge, OxyELITE Pro products entered commerce in early 2013 with a formulation distinct from products marketed previously. The new formulation included an ingredient, aegeline, also known as N-[2-hydroxy-2(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl]-3-phenyl-2-propenamide, which replaced 1,3-dimethylamylamine (also known as methylhexanamine, or, more simply, DMAA) that had been in the product previously. The manufacturer, USPlabs, LLC, failed to submit to FDA, as legally required, a new dietary ingredient (NDI) notice for the use of aegeline in OxyELITE Pro products. An NDI is defined as a dietary ingredient that was not marketed in a dietary supplement prior to October 15, 1994.

Beginning in April 2012, FDA issued warning letters to firms that manufactured or distributed dietary supplements containing DMAA as a dietary ingredient. The warning letters stipulated that products containing DMAA violated FDA regulations because the firms that produced the products had not submitted an NDI notice as required for the use of DMAA as a new ingredient in dietary supplements. In the ensuing months, all firms except USPlabs, LLC, eliminated the use of DMAA and removed products containing DMAA from the market. Although USPlabs, LLC, eventually eliminated the use of DMAA in OxyELITE Pro, the firm introduced aegeline as a new ingredient in OxyELITE Pro even as DMAA-containing products remained in the market. After FDA issued a warning letter to USPlabs, LLC, for failure to submit an NDI notice for the use of aegeline in OxyELITE Pro, the firm voluntarily recalled OxyELITE Pro products in November 2013.

Descriptive epidemiology of reported cases

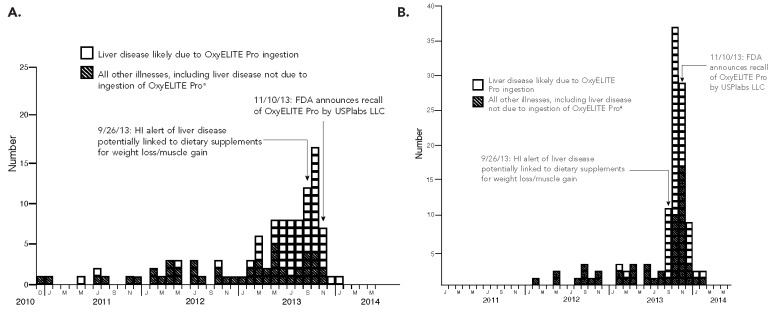

Adverse events reported indicated that 114 consumers who ingested OxyELITE Pro alone or in combination with one or more additional dietary supplements became ill during the study period from January 2011 through February 2014 (Figure). The reports were submitted to FDA via MedWatch (105 reports) or other reporting portals (nine reports). Most reports were submitted by health professionals (54 reports), followed by consumers (53 reports), friends or relatives of consumers (two reports), industry (two reports), a poison control center (one report), and a source reported as “other” (one report); one report did not provide a source. OxyELITE Pro was listed as the sole dietary supplement ingested prior to the onset of illness in 85 (75%) reports; no single dietary supplement emerged as a common exposure among the remaining 29 reports. The principal reasons for ingesting OxyELITE Pro were to lose weight and assist in workouts and/or muscle building.

Figure.

Dates of illness onset (A) and dates of receipt of adverse event reports (n=114) by the FDA (B) in users of OxyELITE Pro”, based on adverse event reports submitted to FDA, December 2010–February 2014

aNo date of illness onset specified for six reports (without liver disease)

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration

HI = Hawaii

Twenty-two (19%) reports listed the ingredients of OxyELITE Pro ingested or commented specifically on whether DMAA or aegeline was present in the formula consumed. Among these 22 reports, 12 specified DMAA and nine specified aegeline; one consumer reported ingesting product for a period of time that included DMAA initially, followed by aegeline. The most recent onset of illness date for consumers who reported ingesting DMAA-containing product was May 2013; the earliest onset of illness date among consumers of product known to contain aegeline was also May 2013. Two of 13 known DMAA exposures involved liver disease compared with nine of 10 known aegeline exposures.

Adverse event reports required evidence of one or more of the following to define an illness as liver disease: elevated transaminases and/or total bilirubin, jaundice and/or icterus, a diagnosis of hepatitis or acute liver failure, and/or an illness for which the subject underwent liver biopsy and/or liver transplantation. For analytic purposes, FDA separated adverse event reports that included OxyELITE Pro ingestion into two groups: (1) those that described liver disease for which no known cause of liver injury other than OxyELITE Pro (alone or in combination with other dietary supplements) consumption was specified (a group we refer to as “liver disease likely due to OxyELITE Pro”) and (2) all other reports. Adverse event reports that portrayed liver disease due to viral hepatitis, gallbladder disease, or any other known causes of liver damage were included in the “other” group. Among the 114 adverse event reports FDA received from January 1, 2011, through February 28, 2014, the FDA classified 55 (48%) as liver disease likely due to ingestion of OxyELITE Pro (alone or in combination with other dietary supplements) (Figure).

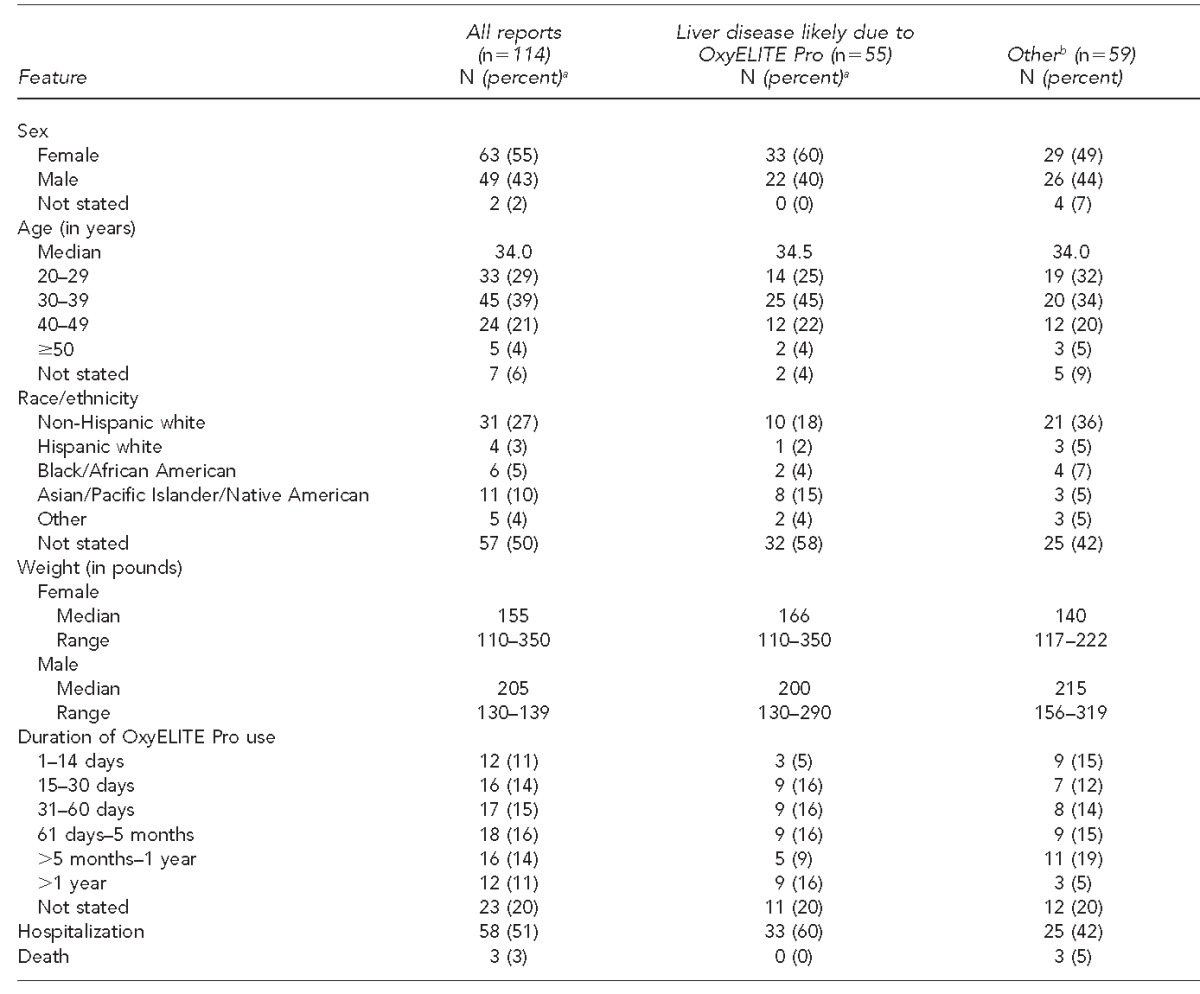

Thirty-three states, two foreign nations, and Puerto Rico submitted adverse event reports indicating OxyELITE Pro consumption. The Table summarizes select demographic and clinical features of the 114 adverse event reports. Overall, females accounted for 63 (55%) reports, and the median age of consumers was 34 years. Race/ethnicity was specified in 57 (50%) reports. Those self-identifying as Asian/Pacific Islander/Native American comprised a greater proportion of consumers with liver disease likely due to OxyELITE Pro compared with those described in reports attributed to other illnesses (8 vs. 3). The median weight for women and men was 155 pounds and 205 pounds, respectively. The median duration of use of OxyELITE Pro among consumers with liver disease likely due to the dietary supplement and those with other illnesses was identical at 2.5 months. Of the 58 consumers who were hospitalized, more were hospitalized with liver disease likely due to OxyELITE Pro (60%) than for other illnesses (42%). Three patients with liver disease likely due to OxyELITE Pro underwent liver transplantation (in California, Pennsylvania, and Hawaii, respectively).

Table.

Demographic and clinical features of adverse events linked to OxyELITE Pro™ via reports received by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, with dates of illness onset of January 2011–February 2014

aPercentages may not total to 100 due to rounding.

bRefers to all other illnesses, including liver disease not due to ingestion of OxyELITE Pro.

Three adverse event reports specified death. In November 2011, a 32-year-old female soldier (weight = 180 pounds) who reportedly consumed multiple dietary supplements in addition to OxyELITE Pro collapsed while running; her body temperature at the hospital was 105 degrees Fahrenheit, and she died five weeks after initial collapse from multiorgan failure.12 A second death involved a 41-year-old male soldier (weight = 232 pounds) who reportedly ingested multiple dietary supplements in addition to OxyELITE Pro and collapsed after an eight-mile run in February 2012 and could not be resuscitated; an autopsy attributed the death to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The third death, which occurred in May 2013, involved a 45-year-old woman (no weight specified) who reportedly died from a brain aneurysm after consuming 13 capsules of OxyELITE Pro during a 27-day period; the woman took no other dietary supplements or medications.

Medical records review

In early October 2013, FDA reviewed 21 medical records provided by HI DOH for patients with liver disease who had onset of illness on or after April 1, 2013, and who ingested one or more dietary supplements used for weight loss and/or bodybuilding. The review revealed that many patients had ingested OxyELITE Pro and experienced liver disease in the absence of viral infection, gallbladder disease, autoimmune disease, or other known causes of liver damage.

After reviewing the 21 medical records for patients in Hawaii, FDA collected medical records from 12 consumers in the continental United States identified through MedWatch reports who reported liver disease after ingesting OxyELITE Pro. The 12 case patients resided in the following states: Arizona (one report), California (three reports), Kentucky (one report), New York (one report), Ohio (two reports), Minnesota (one report), Rhode Island (one report), Virginia (one report), and West Virginia (one report). The findings from FDA's review of medical records for the 12 consumers residing in the continental United States, a brief synopsis of which follows, supported the conclusion drawn by FDA from earlier reviews of Hawaii case-patient medical records and from adverse event reports filed with FDA that OxyELITE Pro likely contributed to liver injury in patients who consumed this dietary supplement. Nine of the 12 case patients were hospitalized, with dates of hospitalization occurring from June through November 2013. Patients ranged in age from 23–51 years, and eight were female. Race/ethnicity was stated for eight case patients: six Asian American, one non-Hispanic white, and one Hispanic white patient. Case patients exhibited elevated transaminases (often >1,000 international units) and hyperbilirubinemia. Liver biopsy results from case patients with severe disease revealed confluent hepatocyte necrosis with marked cholestasis and portal tracts showing chronic inflammatory cell infiltrates composed of small lymphocytes, clusters of plasma cells, and rare eosinophils. In less severe cases, there was evidence of lobular and interface hepatitis, portal triaditis, and piecemeal necrosis with a primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Laboratory analysis of OxyELITE Pro samples

FDA's Forensic Chemistry Center analyzed 18 samples of OxyELITE Pro obtained from 13 case patients as well as product samples from retail shelves. Non-targeted liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry demonstrated the presence of combinations of aegeline, higenamine, caffeine, and yohimbine, or, in some products, a trio of DMAA, caffeine, and yohimbine. The following agents were not detected via the non-targeted screens used nor by additional non-targeted methodologies: drugs, poisons, pharmaceuticals, toxic metals, usnic acid, N-Nitroso-fenfluramine pyrrolizidine alkaloids, aristocholic acid, and phenethylamines. The amounts of aegeline, higenamine, and yohimbine in the samples were measured using liquid chromatography. Quantification of aegeline ranged from 33.2 milligrams (mg)/capsule to 112.0 mg/capsule, while the range of higenamine varied from 15.5 mg/capsule to 41.6 mg/capsule. Yohimbine quantification varied from 1.6 mg/capsule to 3.2 mg/capsule. Forensic examination of product labels showed them to be authentic (i.e., examination of the label indicated they had not been tampered after manufacture).

Causality assessment

On the basis of the evidence, FDA concluded that a causal link likely existed between OxyELITE Pro ingestion and liver injury. First, evidence of liver injury among patients who did not require liver transplantation reversed after OxyELITE Pro ingestion ceased. Second, among the 55 patients with liver disease FDA deemed likely to be due to OxyELITE Pro ingestion, other causes of liver disease were systematically excluded, including viral infections, autoimmune disorders, and intoxications. Third, results of liver biopsies often ascribed a diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury, with OxyELITE Pro cited as the most likely cause. Finally, as shown in the Figure, there was an abrupt reduction in reported cases of liver injury among those who consumed OxyELITE Pro following removal of the dietary supplement from the market.

DISCUSSION

Dietary supplement-induced hepatotoxicity is not a novel phenomenon. In 2009, a supplement called Hydroxycut marketed for weight loss was recalled following the identification of 17 users of the product who experienced liver damage.13 All patients were hospitalized, four died from acute liver failure, and three required liver transplantation. Eight patients in the series were identified at different medical centers, while nine additional illnesses were reported to FDA through MedWatch.13 As in the present report describing OxyELITE Pro-related liver damage, those who became ill after consuming Hydroxycut often experienced jaundice, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting.

Although findings from case series such as the one presented here cannot be used to draw definitive conclusions about the role of OxyELITE Pro as a cause of liver injury, several observations support the plausibility of a causal role. First, for a number of cases, treating physicians ruled out a role in liver injury not only of viruses, but also autoimmune and gallbladder diseases. Second, while some of the patients with liver disease described may not have disclosed medications and/or dietary supplements they took in addition to OxyELITE Pro, for a number of patients in this series, OxyELITE Pro was the only supplement reportedly used before illness occurred. Third, the abrupt national increase beginning in early summer 2013 of illnesses characterized by liver disease suggests that a common exposure was responsible for illness, and the lack of reports of a dietary supplement other than OxyELITE Pro consumed by many patients argues that the latter supplement was likely responsible for causing liver injury. Fourth, for many patients, liver injury resolved after discontinuation of OxyELITE Pro. Finally, extensive forensic chemistry testing of products obtained from case patients as well as from market shelves failed to identify any components not listed on the products' ingredient statements, suggesting one or more of the constituents labeled on the products was responsible for causing liver damage.

During the study period (January 2011 through February 2014), we surmise that a reformulation of OxyELITE Pro to include aegeline was most likely responsible for the increased number of cases of liver injury subsequently reported in 2013. It is possible that DMAA also contributed to liver injury during the study period in consumers who ingested OxyELITE Pro containing this ingredient. Given that it was not until April 2013 that USPlabs, LLC, announced its intention to phase out products containing DMAA, it is likely that DMAA-containing product may have been available for purchase through the study period at least until the first half of 2013. DMAA, a sympathomimetic agent, was linked to cerebral hemorrhage in three adults in New Zealand,14 but to our knowledge, no published studies have attributed liver injury to DMAA. However, the physiologic actions of DMAA on the body are similar to amphetamine and ephedrine,15 and, notably, the liver is vulnerable to amphetamine toxicity.16 As for aegeline, feeding trials in rats with Aegle marmelos, a plant with a long history of use in Ayurvedic medicine, produced hepatic lesions that included central vein abnormalities.17

Illness outbreaks, regardless of etiology, pose challenges in many forms. Among them is the critical need to identify outbreaks as early as possible, a requisite task that precedes the need for implementation of control measures. In the setting of dietary supplement outbreaks, this task may be particularly challenging in the absence of time-tested surveillance systems of the kind that exist for communicable diseases. This challenge was illustrated in the present outbreak of liver disease likely due to OxyELITE Pro, wherein a significant lag separated the occurrence and the reporting of cases. This phenomenon, in part, was noted recently as evidence that a “woefully inadequate system for monitoring supplement safety” exists on the part of FDA.18

CONCLUSION

Although surveillance of dietary supplement adverse events has much room for improvement, we believe MedWatch provides a ready avenue for reporting adverse events by patients, health-care providers, and industry. However, the value of MedWatch depends largely on the extent to which potential reporters employ the system. In the current outbreak, MedWatch reports, once received by FDA, provided rich information that the agency used to undertake regulatory actions as expeditiously as possible to remove OxyELITE Pro from market shelves. In particular, MedWatch reports helped to define a national scope for an outbreak that initially appeared to be confined to Hawaii.

The reports also identified patients in multiple states from whom medical records were retrieved in a fashion that allowed FDA to both confirm and extend clinical and epidemiologic observations reported earlier by authorities in Hawaii. Thus, as often occurs with potential public health threats, in the realm of surveillance for dietary supplement adverse events, it is the astute health-care provider who recognizes something out of the ordinary who contacts local public health authorities that sets in motion the chain of necessary epidemiologic and regulatory action.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Historical perspectives notifiable disease surveillance and notifiable disease statistics—United States, June 1946 and June 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45(25):530–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams DA, Gallagher KM, Jajosky RA, Kriseman J, Sharp P, Anderson WJ, et al. Summary of notifiable diseases—United States, 2011 [published erratum appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63(1):24] MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;60(53):1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park HS, Lloyd S, Decker RH, Wilson LD, Yu JB. Overview of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database: evolution, data variables, and quality assurance. Curr Probl Cancer. 2012;36:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo EJ. Postmarketing safety of biologics and biological devices. Spine J. 2014;14:560–5. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Food and Drug Administration (US) Postmarketing requirements and commitments: introduction databases [cited 2014 Mar 27] Available from: URL: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/post-marketingPhaseIVCommitments/default.htm.

- 6.Food and Drug Administration (US) FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) [cited 2015 Apr 2] Available from: URL: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/default.htm.

- 7.Food and Drug Administration (US) MedWatch online voluntary reporting form [cited 2015 Apr 2] Available from: URL: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/medwatch.

- 8.Food and Drug Administration (US) Download forms [cited 2015 Apr 2] Available from: URL: http://www.fda.gov/safety/MedWatch/HowToReport/DownloadForms/default.htm.

- 9.Fontana RJ, Watkins PB, Bonkovsky HL, Chalasani N, Davern T, Serrano J, et al. Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) prospective study: rationale, design, and conduct. Drug Saf. 2009;32:55–68. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932010-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration (US) The safety reporting portal [cited 2015 Apr 2] Available from: URL: http://www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov.

- 11.Park SY, Viray M, Johnston D, Taylor E, Chang A, Martin C, et al. Notes from the field: acute hepatitis and liver failure following the use of a dietary supplement intended for weight loss or muscle building, May–October 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(40):817–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliason MJ, Eichner A, Cancio A, Bestervelt L, Adams BD, Deuster PA. Case reports: deaths of active duty soldiers following ingestion of dietary supplements containing 1,3-dimethylamylamine (DMAA) Mil Med. 2012;177:1455–9. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fong TL, Klontz KC, Canas-Coto A, Casper SJ, Durazo FA, Davern TJ, 2nd, et al. Hepatotoxicity due to hydroxycut: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1561–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gee P, Talion C, Long N, Moore G, Goet R, Jackson S. Use of recreational drug 1,3-dimethylethylamine (DMAA) [corrected] associated with cerebral hemorrhage. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:431–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsh DF. The comparative pharmacology of the isomeric heptylamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1948;94:225–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dias da Silva D, Carmo H, Lynch A, Silva E. An insight into the hepatocellular death induced by amphetamines, individually and in combination: the involvement of necrosis and apoptosis. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87:2165–85. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arseculeratne SN, Gunatilaka AA, Panabokke RG. Studies on medicinal plants of Sri Lanka. Part 14: toxicity of some traditional medicinal herbs. J Ethnopharmacol. 1985;13:323–35. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(85)90078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen PA. Hazards of hindsight—monitoring the safety of nutritional supplements. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1277–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]