Summary

The transcription factor RUNX1 is frequently mutated in myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia. RUNX1 mutations can be early events, creating pre-leukemic stem cells that expand in the bone marrow. Here we show, counter-intuitively, that Runx1 deficient hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) have a slow growth, low biosynthetic, small cell phenotype and markedly reduced ribosome biogenesis (Ribi). The reduced Ribi involved decreased levels of rRNA and many mRNAs encoding ribosome proteins. Runx1 appears to directly regulate Ribi; Runx1 is enriched on the promoters of genes encoding ribosome proteins, and binds the ribosomal DNA repeats. Runx1 deficient HSPCs have lower p53 levels, reduced apoptosis, an attenuated unfolded protein response, and accordingly are resistant to genotoxic and endoplasmic reticulum stress. The low biosynthetic activity and corresponding stress resistance provides a selective advantage to Runx1 deficient HSPCs, allowing them to expand in the bone marrow and outcompete normal HSPCs.

Introduction

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) begin with the acquisition of a driver mutation that generates a pre-leukemic stem cell (pre-LSC) (Pandolfi et al., 2013). The pre-LSC is self-renewing and capable of competing with normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to ensure its survival and expansion in the bone marrow. Additional mutations gradually accumulate in the pre-LSC and its downstream progeny, giving rise to MDS or AML (Welch et al., 2012). Early mutations in the leukemogenic process often occur in genes encoding chromatin regulators such as TET2, DNMT3A, IDH2, and ASXL1 (Welch et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2014). These genes mediate processes such as DNA methylation, histone modification, or chromatin looping, altering the epigenetic “landscape” of the pre-LSC (Corces-Zimmerman et al., 2014; Jan et al., 2012; Shlush et al., 2014). Mutations that activate signal transduction pathways, such as internal duplication of FLT3 are also common in AML, but most often occur as later events in downstream progenitor populations (Corces-Zimmerman et al., 2014).

RUNX1 is a DNA binding transcription factor that is mutated in de novo and therapy-related AML, MDS, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), and in the autosomal dominant pre-leukemia syndrome familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia (FPD/AML) (Mangan and Speck, 2011). In mice, loss-of-function (LOF) Runx1 mutations cause defects in lymphocyte and megakaryocytic development, and alterations in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that include an increase in the number of committed erythroid/myeloid progenitors and expansion of the lineage negative (L) Sca1+ Kit+ (LSK) population in the bone marrow (Cai et al., 2011; Growney et al., 2005; Ichikawa et al., 2004). Runx1 deficiency has only a modest adverse effect on the number of functional long term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs), reducing their frequency in the bone marrow by 3 fold at most, without affecting their self-renewal properties (Cai et al., 2011; Jacob et al., 2009). LOF RUNX1 mutations may also confer increased resistance to genotoxic stress, as several small-scale studies of MDS/AML patients who were previously exposed to radiation, or treated with alkylating agents, revealed a high incidence (~40%) of somatic single nucleotide variants or insertion/deletion mutations in RUNX1, as compared to the overall 6-10% of MDS patients with LOF RUNX1 mutations (Bejar et al., 2011; Haferlach et al., 2014; Harada et al., 2003; Walter et al., 2013; Zharlyganova et al., 2008). The higher association of RUNX1 mutations with exposure to genotoxic agents suggests two possibilities: either RUNX1 mutations are preferentially induced by these agents, or more likely, that pre-existing RUNX1 mutations conferred a selective advantage to pre-LSCs exposed to these agents. RUNX1 mutations can be early or later events in the progression of MDS and AML (Jan et al., 2012; Welch et al., 2012). That they can be early events is demonstrated unequivocally by the observation that FPD/AML patients who harbor germline mutations in RUNX1 have a ~35% lifetime risk developing MDS/AML (Ganly et al., 2004; Michaud et al., 2002; Song et al., 1999).

Although it has been demonstrated that mutations that occur in pre-LSCs cause them to selectively expand in the bone marrow (Busque et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2014), the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not well understood. Here we aimed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which LOF RUNX1 mutations generate an expanded population of HSPCs. Counter-intuitively, we find that Runx1 deficiency in HSPCs results in a slow growth, low biosynthetic, small cell phenotype, accompanied by markedly decreased ribosome biogenesis (Ribi). Furthermore, Runx1 deficient HSPCs have lower levels of p53 and an attenuated unfolded protein response, and are less apoptotic following exposure to genotoxic stress. These observations lead to a model whereby LOF RUNX1 mutations generate stress resistant HSPCs that are able to perdure and expand by virtue of their slow growth properties and decreased rates of apoptosis as compared to normal HSPCs.

Results

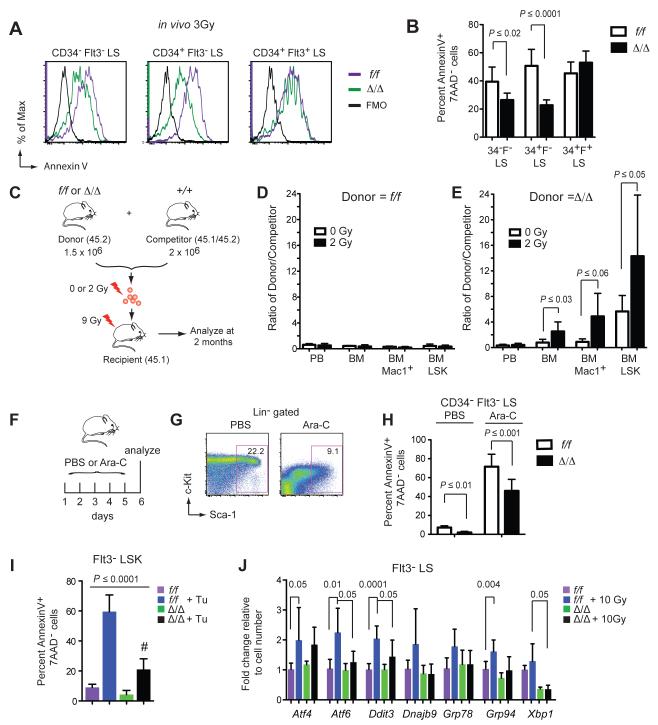

We previously demonstrated that Runx1 deficient murine HSPCs have a decreased percentage of apoptotic cells (Cai et al., 2011). To determine if Runx1 deficiency also protects against radiation-induced apoptosis, we generated hematopoietic-specific LOF Runx1 alleles with Vav1-Cre (Cai et al., 2011). We irradiated control Runx1f/f (f/f) and Runx1f/f; Vav1-Cre (Δ/Δ) mice and measured the percentage of apoptotic HSPCs 24 hours later. HSPCs were analyzed using CD34 and Flt3 markers, since we previously showed that CD48 and CD150 are dysregulated on Runx1 deficient HSPCs (Cai et al., 2011). Staining for Kit was not performed as its levels decrease following irradiation (Simonnet et al., 2009). A smaller percentage of irradiated Δ/Δ CD34− Flt3− LS (long-term repopulating HSCs) and CD34+ Flt3− LS cells (short-term HSCs) were Annexin V+ compared to f/f HSCs (Fig 1A,B). Runx1 deficiency did not, however, reduce the sensitivity of CD34+ Flt3+ LS cells (multipotent progenitors, MPPs) to radiation. Since reduced apoptosis and other properties to be discussed later were common to both CD34+ Flt3− and CD34− Flt3− LSK cells, these two populations were combined (Flt3− LSK cells, or Flt3− LS cells in experiments involving radiation or ≥24 hrs of in vitro culture) in most experiments.

Figure 1. Runx1 deficiency protects HSCs from genotoxic stress.

A. Apoptosis in phenotypic LT-HSCs (CD34− Flt3− LS), ST-HSCs (CD34+ Flt3− LS), and MPPs (CD34+ Flt3+ LS). Mice were irradiated and 24 hrs later 7AAD− cells analyzed for Annexin V staining. f/f = Runx1f/f; Δ/Δ = Runx1f/f;Vav1-Cre; FMO= fluorescence minus one control.

B. Summary of data in panel A (mean ± SD, n=6-7 mice per genotype, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test). 34=CD34; F=Flt3.

C. In vivo competition experiment. 1.5 × 106 f/f or Δ/Δ donor BM cells were mixed with 2 × 106 wild type competitor BM cells. The cells were exposed to 0 or 2 Gy radiation then transplanted into recipient mice. Peripheral blood (PB) and BM were analyzed 2 months post irradiation.

D. The percentage of f/f donor-derived cells [donor/(donor + competitor + residual host)] and +/+ competitor-derived cells [competitor/(donor + competitor + residual host)] is plotted as a ratio of percentage donor/percentage competitor. The experiment was repeated three times, each time using one f/f and one Δ/Δ donor. Plotted is a representative experiment (mean ± SD, n=5-6 recipients, unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-test).

E. The percentage of Δ/Δ donor-derived cells divided by the percentage of +/+ competitor cells as in panel D. There was a significant expansion in non-irradiated Δ/Δ BM Mac1+ (P ≤ 0.03) and BM LSK cells (P ≤ 0.03) compared to their non-irradiated f/f counterparts.

F. Mice were injected for 5 consecutive days with vehicle (PBS) or 10 mg/kg Ara-C, and BM analyzed on day 6.

G. Scatter plots show gating for LS cells (Kit was not gated as its levels decreased following Ara-C treatment).

H. Percentage of apoptotic CD34− Flt3− LS cells with or without Ara-C treatment (mean ± SD, n=7-9 mice, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

I. Percentage of Annexin V+ Flt3− LSK cells 24 hours post intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 1 mg/kg tunicamycin (Tu) or vehicle into mice (mean ± SD, n=4-7 mice, P value determined by ANOVA; all values are significantly different from the comparator (#) by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test).

J. Expression of UPR transcripts (qPCR) in Flt3− LS cells with and without 10 Gy irradiation (mean ± SD, n=3-8 mice, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

To determine if Runx1 deficiency provides a selective advantage to HSCs following radiation exposure we mixed bone marrow (BM) cells from f/f or Δ/Δ mice with wild type competitor BM (+/+) at a 3:4 ratio, and either transplanted the cells directly into lethally irradiated (9Gy) recipient mice, or first subjected the cells to a low level of irradiation (2Gy) prior to transplantation (Fig 1C). If donor HSCs are less sensitive to radiation than +/+ competitor HSCs, the ratio of donor to +/+ competitor cells should increase following irradiation. The ratio of non-irradiated f/f donor to +/+ competitor cells in peripheral blood (PB), total BM, Mac1+ BM cells, and LSK BM cells was the same as the input 3:4 ratio, and not altered by radiation (Fig 1D). In contrast, Δ/Δ LSK cells expanded in the BM relative to +/+ competitor cells (P ≤ 0.002) (Fig 1E), as previously reported (Cai et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2009; Growney et al., 2005; Ichikawa et al., 2004; Jacob et al., 2009; Motoda et al., 2007). Radiation further increased the percentage of Δ/Δ donor-derived total BM and BM LSK cells relative to non-irradiated Δ/Δ cells, and there was a trend towards increased BM Mac1+ cells (Fig 1E). Therefore Runx1 deficient HSCs have a selective advantage over normal HSCs that is accentuated by irradiation.

LOF RUNX1 mutations in AML are associated with refractory disease and inferior event free, relapse free, and overall survival, presumably due to chemotherapy resistance (Gaidzik et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2009). To determine if Runx1 deficiency protects HSCs from chemotherapeutic agents, mice were treated for five days with arabinofuranosyl cytidine (Ara-C) and apoptosis analyzed. Ara-C treatment increased the percentage of apoptotic CD34− Flt3− LS cells of both genotypes, but the percentage of Annexin V+ cells was lower in Δ/Δ than in f/f HSCs (Fig 1F-H).

The expansion and decreased apoptosis of Runx1 deficient HSCs in the absence of induced stress suggests that they are also resistant to endogenous stress. Tunicamycin induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by blocking N-linked glycosylation, which causes misfolded proteins to accumulate in the ER and trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR). Treatment of mice with tunicamycin induced apoptosis of both f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells, but to a much lesser extent in Δ/Δ cells (Fig 1I). The expression of several UPR response genes was induced following irradiation, but activation of Atf6, Ddit3 (CHOP), and Xbp1 was significantly attenuated in Δ/Δ Flt3− LS cells (Fig 1J). As Δ/Δ HSPCs have a slow growth phenotype and do not exhibit increased self-renewal in serial transplant experiments (Cai et al., 2011), we conclude that their expansion in the BM likely results from their increased resistance to endogenous and genotoxic stress.

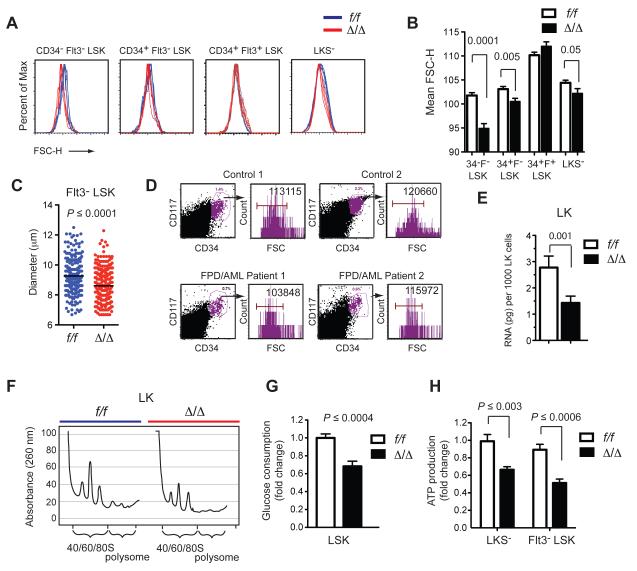

Runx1 deficient HSCs have decreased ribosome content

We noticed during the course of our analyses that Δ/Δ HSPCs produced less forward scatter (FSC) than f/f HSCs, indicating they are smaller in size. This was observed for Δ/Δ CD34− Flt3− LSK (LT-HSCs), CD34+ Flt3− LSK (ST-HSCs), and LKS− (progenitor) cells, although not for CD34+ Flt3+ LSK cells (MPPs) (Fig 2A,B), which coincidentally had normal levels of apoptosis (Fig 1A,B). Δ/Δ HSCs also had a smaller diameter than f/f HSCs (Fig 1C). To determine if this small cell phenotype was also relevant in humans, we analyzed CD117+ CD34+ BM cells from two FPD/AML patients with heterozygous LOF RUNX1 mutations. CD117+ CD34+ cells from these individuals also produced less FSC as compared to cells from age-matched control patients analyzed in the clinic on the same day, on the same cytometer (Fig 2D). Although the available samples are too few to draw any firm conclusions, the data suggest that human FPD/AML HSPCs are relatively small. Murine HSPCs with a mono-allelic LOF Runx1 mutation were not, however, smaller than wild type HSCs (not shown). Cell size is thus one of several aspects of Runx1 haploinsufficiency in mice that differs from the human FPD/AML phenotype (Sun and Downing, 2004), as mouse and humans appear to have different sensitivities to moderately reduced Runx1 dosage.

Figure 2. Runx1 deficient pre-LSCs have decreased ribosome biogenesis.

A. Forward scatter analysis of progenitor and HSPC populations.

B. Summary of data in panel A (mean ± SD, n=10-12, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

C. Mean diameters of Flt3− LSK cells, indicated by black lines, P value was determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

D. Forward scatter analysis of CD117+ CD34+ BM cells from two FPD/AML patients and two unaffected controls. FPD/AML Patient 1 and Control 1 were age-matched adults whose BM was analyzed on the same day on the same cytometer in the clinic. FPD/AML Patient 2 and Control 2 were age-matched children analyzed together on a different day. Mean FSC values are indicated. The FPD/AML patients are heterozygous for a non-functional RUNX1 allele in which exons 2-6 are duplicated.

E. Total RNA amount in 1000 f/f and Δ/Δ LK cells (mean ± SD, n=3-4, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

F. Ribosome profiling. Lysates from 4.5 × 106 f/f or Δ/Δ cells were lysed and centrifuged through a sucrose gradient.

G. Glucose consumption of LSK cells. Cells were cultured in 25 mM glucose for 24 hrs and the change in glucose concentration in the culture medium measured (mean ± SD, n=8, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

H. ATP levels in sorted cells (mean ± SD, n=6, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

Cell size generally correlates with ribosome biogenesis (Ribi) (Cook and Tyers, 2007), therefore we measured the amount of total RNA in Runx1 deficient cells, as the vast majority (>85%) of cellular RNA comprises or encodes components of the ribosome. Indeed Runx1 deficient HSPCs (LKS+/−, heretofore designated LK) contained 50% less total RNA than f/f cells on a per cell basis (Fig 2E). We also examined ribosome composition by preparing lysates from equal numbers of f/f and Δ/Δ LK cells, centrifuging the lysates through a sucrose gradient, and recording the UV absorbance of individual fractions. Δ/Δ LK cells had fewer ribosomes in all fractions, including polysomes, 80S assembled ribosomes, and large and small ribosomal subunits (Fig 2F). Analysis of 3 separate sucrose gradient experiments showed no perturbation of the 60S/40S subunit ratio, and therefore Ribi was decreased in a balanced manner. Consistent with the decreased Ribi, Runx1 deficient cells had a low metabolic profile; Δ/Δ LSK cells consumed less glucose when cultured in vitro (Fig 2G), and both LKS− and Flt3− LSK cells produced less ATP than their f/f counterparts (Fig 2H). Runx1 promotes G1 to S phase cell cycle progression (Friedman, 2009), and correspondingly Runx1 deficient HSPCs contain a higher percentage of cells in G1 (Cai et al., 2011). As decreased Ribi also delays G1 to S phase progression (Donati et al., 2012), decreased Ribi may underlie the effect of Runx1 deficiency on the cell cycle.

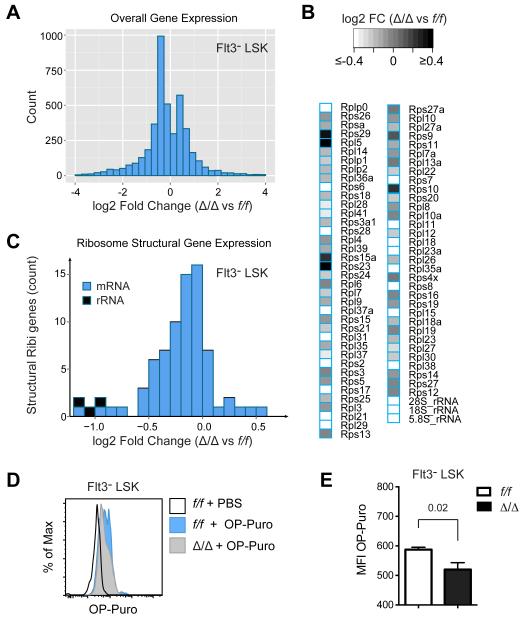

We performed RNA-Seq to measure the relative levels of RNAs encoding or comprising structural components of the ribosome, using spike-in controls to normalize the data according to cell number. We made two separate sequencing libraries; one from polyA-selected RNA to analyze mRNAs encoding ribosome proteins, and one from total RNA to compare rRNA levels. In total, 4248 genes were differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05). There was an average 11% decrease in overall mRNA levels in Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells (Fig 3A), and a slightly greater 13% decrease in mRNA transcripts for ribosome proteins (Fig 3B,C). Although an 11% versus 13% difference is small, it was significant (P < 0.01, one-tailed t-test), indicating that the expression of ribosome protein genes (as compared to all genes) was preferentially affected by Runx1 loss. The largest reduction was in rRNA, which was lower by 51% in Δ/Δ HSCs (Fig 3C), similar to the reduction in total RNA levels in LK cells (Fig 2E).

Figure 3. Ribosome protein and rRNA transcripts are decreased in Δ/Δ HSCs.

A. Histogram of overall gene expression changes in Δ/Δ versus f/f Flt3− LSK cells. Sequencing libraries were prepared from Poly(A) selected RNA from duplicate samples of 2 × 104 cells sorted directly into Trizol, with added spike-in controls.

B. Heat map of changes in ribosome protein mRNAs and rRNAs. Libraries for rRNA analysis were prepared from total RNA.

C. Relative expression of genes encoding structural components of ribosomes.

D. Histogram of OP-Puro incorporation following one hour of in vivo labeling.

E. Summary of OP-Puro incorporation (mean ± SD, n=7-8, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

See also Table S1.

Decreased biosynthetic capacity should negatively impact the rate of translation. We examined translation by measuring the incorporation of the alkyne puromycin analogue O-propargyl-puromycin (OP-Puro) into nascent peptides following injection into mice, as described by Signer et al. (Signer et al., 2014). Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells incorporated significantly less OP-Puro than f/f cells, indicating that the overall rate of translation was decreased in Δ/Δ HSCs (Fig 3D,E).

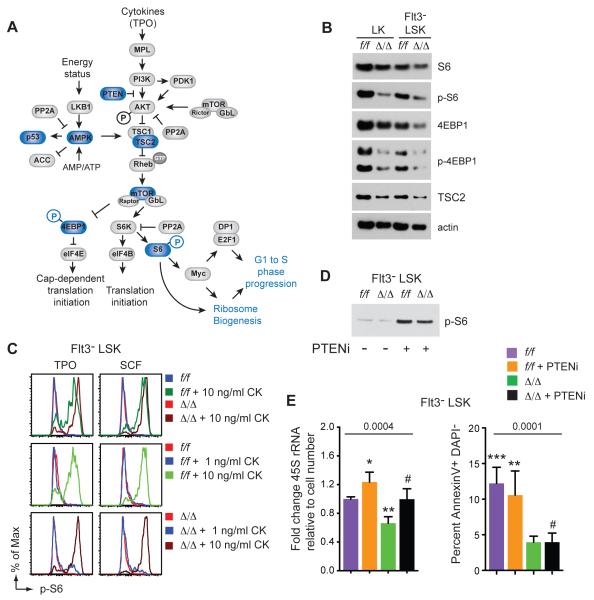

Decreased Ribi can be partially reversed by activating mTOR signaling

The mTOR pathway is an important regulator of cell growth, Ribi, and overall translation. Activated mTOR phosphorylates 4EBP1, relieving its repression of eIF4E, allowing Cap-dependent translation initiation (Fig 4A). mTOR also phosphorylates ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K), which directly regulates Ribi by phosphorylating the small ribosomal protein S6, and by inactivating several repressors of rRNA and ribosome protein transcription (Huber et al., 2011). The overall levels of S6, 4EBP1, tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2), and actin were slightly decreased in Δ/Δ LK and Flt3− LSK cells freshly isolated from the BM (Fig 4B). Phosphorylated 4EBP1 (p-4EBP1) was lower relative to total 4EBP1 raising the possibility that tonic mTOR signaling was slightly dampened. The p-S6 level varied in different experiments; in some experiments it was elevated in Δ/Δ CD34+/− Flt3− LSK cells (Fig S1), and in other experiments p-S6 was lower (Fig 4B). Although the activation status of tonic mTOR signaling was somewhat equivocal, our interpretation is that it is not greatly decreased and unlikely to account for the ~50% decrease in Ribi.

Figure 4. mTOR signaling in Runx1 deficient HSPCs.

A. Summary of mTOR pathway. Blue indicates proteins or phosphorylation events that were examined by Western blot.

B. Western blot of mTOR pathway proteins in freshly isolated HSPCs (lysates from 20,000 cells/lane).

C. Activation of the mTOR pathway as measured by phosphorylation of S6 in serum starved cells stimulated with SCF or TPO at the indicated concentrations. CK, cytokine.

D. Western blot for p-S6 in lysates prepared from 20,000 Flt3− LSK cells 24 hours following i.p. injection of the PTEN inhibitor VO-OHpic trihydrate (PTENi).

E. Left; qPCR for 45S rRNA in Flt3− LSK cells 24 hours following i.p. injection of vehicle or PTENi (mean ± SD, n=3-5 mice). Right; apoptosis in Flt3− LSK cells following injection of PTENi (mean ± SD, n=3-6 mice). P values determined by one-way ANOVA, values significantly different from the comparators (#) by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test are indicated with asterisks. See also Figure S1.

We examined mTOR signaling further by analyzing mTOR pathway activation in response to hematopoietic cytokines. Runx1 directly regulates several cytokine receptors including MPL, the receptor for thrombopoietin (TPO), an important regulator of HSC function (Cai et al., 2011; Heller et al., 2005; Kimura et al., 1998; Solar et al., 1998). Therefore we predicted that Runx1 deficient HSPCs might be less responsive to mTOR activation by cytokines. We tested the response of Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells to TPO, and also to stem cell factor (SCF) to determine if this was the case. The addition of 10 ng/ml TPO or SCF to serum starved f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells in vitro resulted in S6 phosphorylation within 10 minutes (Fig 4C). Contrary to our prediction, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of p-S6 was higher in Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells relative to f/f cells following TPO or SCF stimulation. f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells also responded to similar concentrations of TPO and SCF (Fig 4C). We conclude that the mTOR pathway could be robustly activated by TPO and SCF in Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells.

Activation of mTOR signaling can correct some of the proliferation, differentiation, and translation defects associated with mutations in ribosome protein genes (Boultwood et al., 2013; Payne et al., 2012). To determine whether activation of mTOR signaling could reverse the decreased Ribi and apoptosis in Δ/Δ HSCs, we treated mice with an inhibitor of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), VO-OHpic trihydrate (PTENi). Injection of PTENi increased p-S6 levels in both f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells, demonstrating that mTOR signaling was activated (Fig 4D). Activation of mTOR signaling increased the levels of 45S rRNA in both f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells (Fig 4E), although 45S rRNA levels were still significantly lower in Δ/Δ compared to f/f cells. Activation of mTOR had no effect on the percentage of apoptotic f/f or Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells (Fig 4E), thus increased mTOR signaling could partially normalize Ribi, but it failed to alter the low apoptotic phenotype of Δ/Δ HSCs.

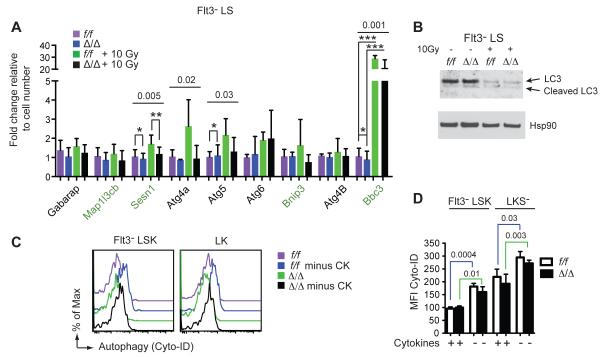

Increased autophagy does not contribute to decreased Ribi

Autophagy is a process by which cellular contents, including ribosomes, are degraded and recycled for use under starvation conditions. Lower mTOR signaling can induce autophagy, which in turn could contribute to the decreased ribosome content of Δ/Δ cells. We analyzed the expression of genes encoding the core autophagy machinery, and several genes whose expression defines a pro-autophagic signature (Warr et al., 2013) by qPCR. Expression of the pro-autophagy signature genes was either unaltered (Bnip3) or slightly lower (Sesn1, Bbc3) in Δ/Δ Flt3− LS cells (Fig 5A). Radiation increased Bbc3 (Puma) mRNA in both f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LS cells, but significantly less so in Δ/Δ cells (Fig 5A). The proportion of cleaved versus uncleaved LC3 protein, which is required for the formation of autophagosomal membranes, increased to a similar extent in irradiated f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LS cells (Fig 5B). We measured autophagy in Flt3−LSK cells and LKS− progenitors that were provided or starved for cytokines by labeling autophagic vacuoles (pre-autophagosomes, autophagosomes, and autolysosomes) with a cationic amphiphilic tracer dye, Cyto-ID. Cytokine starvation increased the staining of autophagic vacuoles in both f/f and Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK and LK cells, indicative of increased autophagy (Fig 5C,D). However, the autophagic vacuolar staining was equivalent in Δ/Δ and f/f cells in the presence or absence of cytokines. We conclude that increased autophagy is not the primary cause of the decreased ribosome content in Δ/Δ HSCs and progenitors. Since mTOR signaling represses autophagy, and autophagy is not higher in Δ/Δ HSCs, this supports our conclusion that tonic mTOR signaling is not significantly decreased in Δ/Δ HSCs.

Figure 5. Runx1 deficient HSPCs do not undergo increased autophagy.

A. Relative mRNA levels for core (black labels) and pro-autophagy genes (green labels) in freshly isolated Flt3− LS cells without or 24 hours post 10Gy radiation (mean ± SD, n=3-8, P value determined by one-way ANOVA, significantly different values were determined by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test and indicated with asterisks).

B. Western blot for LC3 in lysates prepared from 20,000 Flt3− LS cells without or 6 hours post 10Gy radiation.

C. Autophagy in HSPCs measured by Cyto-ID staining of autophagic vacuoles. Cells were cultured for 6 hrs in the presence or absence of cytokines (CK = SCF, Flt3L, IL-11). Fresh cells or starved cells were stained by Cyto-ID.

D. Quantification of data in panel B (mean ± SD, n=3 × 2 experiments, shown is one representative experiment, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

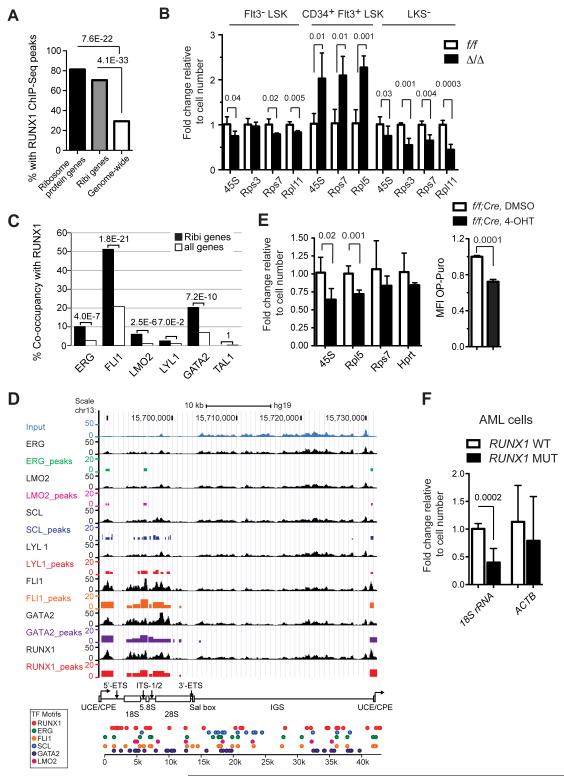

Runx1 directly regulates Ribi

Since neither mTOR signaling nor autophagy was lower in Δ/Δ HSCs, we concluded there was another reason Ribi was decreased, and examined whether Runx1 directly regulates Ribi. We analyzed the genome wide occupancy of RUNX1 using previously published ChIP-Seq data generated in human CD34+ HSPCs (Beck et al., 2013). We identified 20,552 RUNX1 peaks (q-value < 0.01), and examined peaks located within 5 kb of the transcriptional start sites (TSS) of their closest genes (32.37% of all RUNX1 peaks). 70.56% of the promoter proximal regions of 197 genes involved in Ribi, which included 80 genes encoding large or small ribosome subunit proteins, were occupied by RUNX1 in human CD34+ HSPCs (Fig 6A). Of the 80 genes encoding structural proteins of the ribosome, 65 (80.25%) had a RUNX1 peak within 5 kb of their promoter (Fig 6A). An additional 45 Ribi genes, including 10 ribosome protein genes, had at least one RUNX1 peak with an enrichment of ≥ 2 fold over input (Table S1). In comparison, only 29.3% of all promoters genome wide were occupied by RUNX1 (Fig 6A). Therefore RUNX1 binding in human CD34+ HSPCs is highly enriched at the promoters of Ribi genes (P ≤ 4.1E-33), including the subset of Ribi genes encoding structural components of the ribosome (P ≤ 7.6E-22). We performed a similar analysis of Runx1 occupancy using other published ChIP-Seq datasets, and although the fraction of Ribi genes occupied by Runx1 was lower in these other cell types and studies, in all cases occupancy was enriched on Ribi genes (Table S2). We examined the expression of several ribosome genes occupied by RUNX1 in more purified populations of mouse HSPCs, and found significant differences in the levels of Rps3, Rps7, Rpl11 and rRNA transcripts in both Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK and LK(S−) cells when measured on a per-cell basis (Fig 6B). Interestingly, the expression of Rps7 and 45S rRNA was elevated in Δ/Δ Flt3+ LSK cells (MPPs), and thus the effect of Runx1 loss on Ribi is context dependent. In conclusion, many genes involved in Ribi are direct Runx1 targets, and their expression is affected by a LOF Runx1 mutation.

Figure 6. Runx1 is enriched at the promoters of ribosome protein genes, and occupies rDNA repeats.

A. Enrichment of Runx1 binding peaks at the promoters of ribosome protein genes and genes involved in Ribi. Enrichment P-value is shown over the bars and was computed using hypergeometric distribution. Genes annotated with biological process GO terms related to Ribi plus 80 ribosome protein genes were analyzed.

B. qPCR for rRNA and ribosome protein mRNAs in HSPCs (mean ± SD n=3-5, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

C. Enrichment of co-occurrence of RUNX1 and other hematopoietic TFs at the promoters of Ribi genes. P-values were computed using hypergeometric distribution.

D. TF ChIP-Seq peaks across the rDNA sequence. For each TF, the top track shows the normalized ChIP-Seq signal and the bottom track shows binding peaks called by MACS2. The height of a peak is proportional to the fold enrichment of the ChIP-Seq signal compared to input control. On the bottom are TF binding sites across the rDNA sequence. Binding sites were detected using FIMO at p-value < 0.005. IGS, intergenic spacer; UCE/CPE, upstream control element/core promoter element; 5′-ETS, 5′ external spacer; ITS-I/2, internal transcribed spacer regions 1 and 2; Sal box; 3′-ETS, 3′ external spacer.

E. Acute deletion of Runx1 in vitro decreases 45S rRNA and translation. Runx1 was deleted in Runx1f/f cells that were transgenic for a ubiquitously expressed, tamoxifen regulated Cre, by addition of 4-OHT to the culture medium. Left, RNA levels were measured by qPCR 48 hours after 4-OHT addition (mean ± SD, n=5). Right, OP-Puro incorporation (mean ± SD, n=3, P values determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

F. rRNA levels in primary human AML cells with (MUT) or without (WT) LOF RUNX1 mutations (mean ± SD, n=5-7, unpaired two-tailed Student t-test).

We next determined whether other hematopoietic transcription factors (TFs), including GATA2, FLI1, LYL1, TAL1, LMO2, and ERG, were enriched on RUNX1-bound promoters in human CD34+ HSPCs (Beck et al., 2013). We found that FLI1 was highly enriched on RUNX1-occupied Ribi gene promoters; approximately 50% of the Ribi gene promoters bound by RUNX1 were also occupied by FLI1, as compared to 20% of the RUNX1 bound promoters genome-wide (Fig. 6C). GATA2 was also highly enriched on Ribi gene promoters bound by RUNX1, although to a lesser extent than FLI1 (Fig. 6C). Enrichment of ERG and LMO2 co-occupancy was significant, while co-occupancy by LYL1 and TAL1 was not enriched.

In addition to occupying the promoters of ribosome protein genes, all three Runx proteins (Runx1, Runx2, Runx3) were previously shown to associate with nucleolar organizing regions, to bind RUNX consensus sites in the genes encoding rRNA (rDNA), and to regulate rRNA transcription (Ali et al., 2008; Young et al., 2007). We analyzed the binding of RUNX1 and the other hematopoietic TFs to the rDNA repeats using the same ChIP-Seq data generated in hCD34+ HSPCs (Beck et al., 2013). Current genome assemblies do not contain rDNA repeats, so in order to map ChIP-seq reads to the rDNA sequence we computationally appended the sequence of a single rDNA repeat to the proximal tip of chromosome 13 in the human genome assembly. Since only one rDNA repeat sequence is included in the assembly, the data obtained represents an aggregate of signals on all ~400 rDNA repeats (Zentner et al., 2011). All 7 TFs occupied the upstream control element/core promoter element (UCE/CPE), and most of the rDNA repeat coding region, with RUNX1, GATA2, and FLI1 generating the most highly enriched peaks (Fig 6D). The occupied regions were similar to those bound by the second largest subunit of DNA polymerase I (RPA116) and the upstream binding protein (UBF) in K562 cells (Zentner et al., 2011). Analysis of the rDNA repeat sequence identified motifs for the five sequence specific TFs (RUNX1, GATA2, FLI1, TAL1, and ERG) throughout the rDNA repeat, including in the intergenic sequence (IGS) not occupied by any of the TFs based on the lack of enrichment relative to Input (Fig 6D).

We examined whether acute deletion of Runx1 would affect the levels of 45S rRNA and translational rate in HSPCs. Purified HSCs (Flt3− LSK) containing two floxed Runx1 alleles and a tamoxifen regulated Cre (Hayashi and McMahon, 2002) were cultured ex vivo for 48 hours in the presence or absence of the tamoxifen metabolite 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT). The level of 45S rRNA and OP-Puro incorporation were significantly reduced 48 hours after deletion of Runx1 with Cre + 4-OHT (Fig 6E), further supporting the hypothesis that Runx1 directly regulates Ribi in HSPCs. We also analyzed the level of rRNA in primary human AML cells containing LOF RUNX1 mutations. 18S rRNA was significantly lower in AML cells containing LOF RUNX1 mutations, suggesting that the relatively low Ribi phenotype is also a feature of AML blasts (Fig 6F).

In summary, the Ribi gene promoter and rDNA occupancy data derived in human CD34+ cells, in addition to the effects of acute deletion of Runx1 on 45S rRNA levels and translation in HSPCs support a direct role for Runx1 in regulating Ribi.

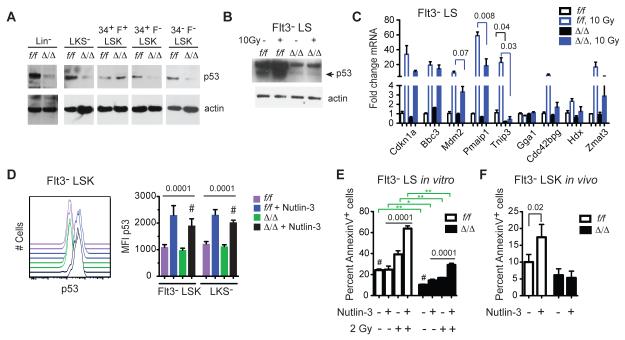

Runx1 deficient HSPCs do not activate p53

Ribi is the most energy-consuming cellular process, and its integrity is carefully monitored by a p53 checkpoint. Defects associated with the ribosomopathies Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA), Schwachman-Diamond syndrome, and in the somatically acquired 5q- syndrome in MDS caused by mutations in Ribi genes result in activation of p53, G1 growth arrest, and cellular senescence or apoptosis (Golomb et al., 2014). However, we observed lower p53 protein levels in Δ/Δ versus the corresponding f/f populations in Western blots of lysates prepared from equal numbers of HSPCs, including Lineage minus (Lin−) and LKS− progenitors, LT-HSCs, and ST- HSCs (Fig 7A). Tp53 mRNA levels were not altered, however, in Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells by RNA-Seq, therefore the reduction in p53 protein levels in LT-HSCs and ST-HSCs occurs post-transcriptionally. The only population in which p53 was not reduced was CD34+ Flt3+ LSK cells (MPPs) (Fig 7A), which correlated with their normal size (Fig 2A,B), higher levels of 45S rRNA (Fig 6B), and lack of radiation resistance (Fig 1A,B). Radiation increased p53 levels in f/f Flt3− LS cells, but very little increase was observed in the equivalent Δ/Δ population (Fig 7B). The activation of several p53 target genes by radiation (Mdm2, Pmaip1, Tnip3) was attenuated in Δ/Δ Flt3− LS cells (Fig 7C).

Figure 7. p53 protein levels are lower in Runx1 deficient HSPCs.

A. Western blots for p53 in purified HSC and progenitor populations. Lysates from 20,000 cells were loaded in each lane. The p53 and actin blots are different exposures from the same gel.

B. p53 in Flt3− LS cells, pre- and 6 hrs post radiation of mice.

C. qRT-PCR for p53 target genes in Flt3− LS cells, pre- and 6 hrs post radiation or mice (mean ± SEM, n=3, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

D. Intracellular p53 staining in HSPCs in the absence or presence of Nutlin-3 treatment in vitro (3 hrs at 10 μM). On left are representative histograms for Flt3− LSK cells. Data for Flt3− LSK and LKS− cells are summarized in the bar graph on the right (mean ± SD, n=5, one-way ANOVA, all values were significantly different from the comparators (#) by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test).

E. Annexin V+ Flt3− LS cells in the absence and presence of Nutlin-3 and irradiation in vitro (mean ± SD, n=5, ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests, comparator = #). Significant differences between pairs of samples are indicated by green brackets and determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

G. Annexin V+ Flt3− LSK cells in mice 24 hours post i.p. injection of Nutlin-3 (20 mg/kg) (mean ± SD, n=4, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

We determined the extent to which activation of p53 could correct the low apoptotic phenotype of Δ/Δ HSCs by treating cells with the Mdm2-p53 inhibitor Nutlin-3. Treatment with Nutlin-3 increased the levels of p53 in Flt3− LSK and LKS− cells, although the p53 MFI was lower in Δ/Δ cells than in equivalently treated f/f cells (Fig 7D). Apoptosis was not elevated to the same extent in Δ/Δ Flt3− LS cells as compared to f/f cells in response to Nutlin 3 treatment in vitro, either in the absence or presence or radiation (Fig 7E), and Nutlin 3 failed to increase the percentage of apoptotic Δ/Δ Flt3− LSK cells in vivo when injected into mice (Fig 7F). In summary, we conclude that the p53 pathway is attenuated in Δ/Δ HSPCs, but that activation of p53 alone cannot reverse the low apoptotic phenotype.

Discussion

LOF RUNX1 mutations can be early or later events in the progression of MDS or AML. Here we show that early LOF Runx1 mutations reduce Ribi in HSPCs. The reduction in Ribi correlated with lower rates of translation and a stress resistant phenotype, with attenuated UPR and p53 pathways. The increased stress resistance resulted in the superior survival of Runx1 deficient HSCs in the face of genotoxic insults, providing them with a selective advantage over normal HSCs in the bone marrow. Thus, Runx1 mutations create a “hibernating” pre-LSC that, due to its stress resistance, can perdure and preferentially accumulate. The negative impact of Runx1 loss on Ribi could be partially reversed by activating mTOR signaling, suggesting that one of the important contributions of cooperating mutations in AML that activate signaling pathways may be to at least partially overcome the decreased Ribi. Importantly, activation of mTOR signaling increased Ribi without increasing apoptosis, thus the stress resistance conferred by Runx1 loss persists in the context of proliferative signals, as shown previously for activated Ras signaling (Motoda et al., 2007). It will be interesting to see if other initiating mutations in MDS and AML result in dysregulation of Ribi, and whether this is a common mechanism underlying pre-malignancy. Evaluation of Ribi in human MDS and AML samples will require normalizing RNA levels based on cell number with spike-in controls, since normalizing by total RNA content will mask alterations in Ribi (Loven et al., 2012).

Although we cannot rule out the possibility that altered expression of cell surface or signaling molecules is responsible for the decreased Ribi, the ChIP-Seq occupancy data suggest that Runx1 loss directly impacts Ribi. The regulation of Ribi by Runx1 is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that Runx proteins regulate the transcription of rRNA (Ali et al., 2008; Young et al., 2007). However, the prior studies showed that Runx1 functions as a negative regulator of rRNA transcription; here we show that Runx1 appears to positively regulate rRNA transcription in HSCs and progenitors, and negatively regulate it in MPPs. Therefore the functional outcome of Runx1 loss is context dependent. The activity of Runx1 in different contexts may be influenced by cooperating hematopoietic TFs such as FLI1, which was previously shown to regulate Ribi in Friend erythroleukemic cells (Juban et al., 2009), or by global regulators of Ribi such as Myc (Dang, 2012). The chromatin regulatory complexes that Runx1 recruits could also determine whether the outcome is the activation or repression of Ribi. For example, Runx1 recruits the polycomb repressor complex 1 (PRC1) through a direct interaction with Bmi1 (Yu et al., 2012), and loss of Bmi1 decreased the expression of multiple Ribi genes in erythroid progenitor cells (Gao et al., 2015).

The decrease in p53 levels in Runx1 deficient HSPCs is in direct contrast to the activation of p53 associated with perturbed Ribi in the ribosomopathies. Ribosomopathies are caused by mutations in ribosome proteins or assembly factors, and are thought to create imbalances in ribosome components, often apparent as an imbalance in the ratio of small and large ribosome subunits (Teng et al., 2013). This in turn leads to the accumulation of excess ribosome proteins that cannot be incorporated into small or large ribosome subunits. Two ribosome proteins, RPL5 and RPL11 are major mediators of this Ribi checkpoint; excess RPL5 and RPL11 bind Mdm2 and inhibit its interaction with p53, causing p53 to accumulate (Teng et al., 2013). However, in situations where both rRNA and mRNAs for ribosome proteins are decreased, p53 levels tend to be lower rather than higher (Donati et al., 2011). For example, simultaneous inhibition of ribosomal RNA and protein synthesis by serum starvation or rapamycin treatment was shown to reduce, rather than increase p53 levels (Donati et al., 2011). In Runx1 deficient HSPCs both rRNA and mRNAs encoding ribosome proteins were lower, there was no evidence of either small or large ribosome subunit accumulation, and the p53 checkpoint was not activated.

The demonstration of decreased Ribi and the low metabolic profile of Runx1 deficient HSPCs raises the issue of how residual Runx1 deficient leukemic or preleukemic HSCs can be eradicated in patients during or following chemotherapy to reduce bulk disease. Determining how the survival and stress resistance of these cells is wired may be necessary for devising strategies to ablate them.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Runx1f/f;Vav1-Cre mice (8-12 weeks old) were described previously (Cai et al., 2011). Mice were treated according to the University of Pennsylvania’s Animal Resources Center and IACUC protocols.

Human samples

AML pheresis and bone marrow mononuclear cells were obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Stem Cell and Xenograft Core, under the approval from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB). All samples lacked TP53, ATM, KIT, PTEN, JAK2, and KRAS mutations. Frozen human AML samples were recovered in RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS, live cells counted, and RNA prepared from equivalent numbers of cells.

Transplantation

B6.SJL (Ly5.1) mice were purchased from the NCI and used as recipients. Whole bone marrow cells from 129S1/SvImJ (Ly5.2) x B6.SJL (Ly5.1) F1 mice (JAX, Bar Harbor, ME) were used as competitors. 2 ×106 competitor cells mixed with 1.5 ×106 Runx1f/f or Runx1f/f;Vav1-Cre bone marrow were either irradiated (2Gy) or not, and injected into the tail vein of irradiated recipient mice (9Gy, split dose 3 hours apart). BM contribution was measured 2 months after transplantation.

Cell purification and flow cytometry

Followed lineage depletion (Miltenyi), BM cells were stained with surface markers and analyzed/sorted by LSRII/Aria (BD Bioscience, San Jose CA). Antibodies are listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Dead cells were stained with 7-AAD (eBioscience) or DAPI (Invitrogen). VO-OHpic (Sigma) was injected into mice (20mg/kg i.p.) on two consecutive days.

Cell diameters were measured as described by Signer et al. (Signer et al., 2014).

Intracellular staining

Cells were fixed by 2% PFA, permeabilized by methanol, then incubated with primary (1:300) and secondary antibody (1:2000). To measure translation rates in vivo, mice were injected with OP-Puro (Medchem Source, 50 mg/kg, i.p.), BM was collected one hour later and stained for surface markers and OP-Puro using the Click-iT Protein Synthesis Assay Kit (Life Technologies) (Signer et al., 2014). To measure translation following Runx1 deletion in vitro, purified Kit+ cells were cultured with 5 μM 4-OHT for 48 hrs, and OP-Puro added 20 minutes before harvesting and staining the cells.

Apoptosis assays

Mice were sacrificed 24 hours post radiation with 3Gy or following a single i.p. injection with Tunicamycin (Sigma, 1mg/kg) or Nutlin-3 (Sigma, 20mg/kg), or after the last of 5 daily injections with AraC (Sigma, 100mg/kg). BM cells were stained for Annexin V, DAPI, and antibodies against lineage (B220, CD3, Ter119, Mac1 and Gr1), Sca1, Flt3, CD34, and Kit. Lin− cells were enriched with a lineage depletion kit (Miltenyi), cultured with or without 10μM Nutlin-3 for 24 hours, then stained for cell surface markers.

Autophagy assay

HSPCs were purified and cultured in Stemspan medium with or without SCF (150ng/ml), Flt3 (1ng/ml) and IL-11 (20ng/ml) for 6 hours. Cyto ID staining was analyzed following the manufacturer’s protocol (Enzo Life Sciences).

Western blots and qPCR

2 × 104 sorted cells were mixed with loading dye and electrophoresed through 4-12% SDS-PAGE gels for Western blots. Total RNA was extracted with microRNA easy kit (Qiagen) and digested with DNase (Qiagen). Concentration was measured by Bio-analyzer (Agilent). Reverse transcription and real time PCR were performed using standard protocols. Antibodies, qPCR primer sequences, and a more detailed Western Blot protocol are included in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Polysome profiling

4.5 × 106 Lin− c-Kit+ cells were sorted and polysome profiling performed using standard protocols.

Glucose consumption and ATP production

Sorted LSK cells were cultured for 24 hours in Stem Span medium. Glucose concentration in the medium was measured by YSI 7100 Multiparameter Bioanalytical System (YSI Life Sciences), and ATP in cells using an ATP Detection Kit (Life Technologies).

ChIP-Seq and RNA-Seq

Methods for ChIP-Seq and RNA-Seq analysis are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. GEO accession number for RNA-Seq data is GSE67609.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Runx1 deficient HSCs are resistant to endogenous and genotoxic stress

Runx1 deficient HSCs have decreased ribosome biogenesis

Runx1 directly regulates ribosome biogenesis

Acknowledgments

NIH R01 CA149976 and the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute (to NAS), NIH R01 CA106995 (PM), NIH R01 HL111192 (ARK) and NIH R01 HG006130 (KT) supported this work. Core facilities at the University of Pennsylvania are supported by a CCSG to the Abramson Cancer Center (P30 CA016520). Technical support was provided by Daniel Marmer of the Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali SA, Zaidi SK, Dacwag CS, Salma N, Young DW, Shakoori AR, Montecino MA, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Imbalzano AN, et al. Phenotypic transcription factors epigenetically mediate cell growth control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6632–6637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800970105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck D, Thoms JA, Perera D, Schutte J, Unnikrishnan A, Knezevic K, Kinston SJ, Wilson NK, O’Brien TA, Gottgens B, et al. Genome-wide analysis of transcriptional regulators in human HSPCs reveals a densely interconnected network of coding and noncoding genes. Blood. 2013;122:e12–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Raza A, Levine RL, Neuberg D, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boultwood J, Yip BH, Vuppusetty C, Pellagatti A, Wainscoat JS. Activation of the mTOR pathway by the amino acid (L)-leucine in the 5q- syndrome and other ribosomopathies. Advances in biological regulation. 2013;53:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busque L, Patel JP, Figueroa ME, Vasanthakumar A, Provost S, Hamilou Z, Mollica L, Li J, Viale A, Heguy A, et al. Recurrent somatic TET2 mutations in normal elderly individuals with clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1179–1181. doi: 10.1038/ng.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Gaudet JJ, Mangan JK, Chen MJ, De Obaldia ME, Oo Z, Ernst P, Speck NA. Runx1 loss minimally impacts long-term hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009;457:889–891. doi: 10.1038/nature07619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook M, Tyers M. Size control goes global. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2007;18:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong WJ, Weissman IL, Medeiros BC, Majeti R. Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2548–2553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324297111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149:22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati G, Bertoni S, Brighenti E, Vici M, Trere D, Volarevic S, Montanaro L, Derenzini M. The balance between rRNA and ribosomal protein synthesis up- and downregulates the tumour suppressor p53 in mammalian cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:3274–3288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati G, Montanaro L, Derenzini M. Ribosome biogenesis and control of cell proliferation: p53 is not alone. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1602–1607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AD. Cell cycle and developmental control of hematopoiesis by Runx1. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:520–524. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidzik VI, Bullinger L, Schlenk RF, Zimmermann AS, Rock J, Paschka P, Corbacioglu A, Krauter J, Schlegelberger B, Ganser A, et al. RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: results from a comprehensive genetic and clinical analysis from the AML study group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:1364–1372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganly P, Walker LC, Morris CM. Familial mutations of the transcription factor RUNX1 (AML1, CBFA2) predispose to acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1–10. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000139611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao R, Chen S, Kobayashi M, Yu H, Zhang Y, Wan Y, Young SK, Soltis A, Yu M, Vemula S, et al. Bmi1 promotes erythroid development through regulating ribosome biogenesis. Stem cells. 2015;33:925–938. doi: 10.1002/stem.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb L, Volarevic S, Oren M. p53 and ribosome biogenesis stress: The essentials. FEBS letters. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Growney JD, Shigematsu H, Li Z, Lee BH, Adelsperger J, Rowan R, Curley DP, Kutok JL, Akashi K, Williams IR, et al. Loss of Runx1 perturbs adult hematopoiesis and is associated with a myeloproliferative phenotype. Blood. 2005;106:494–504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, Okuno Y, Bacher U, Nagae G, Schnittger S, Sanada M, Kon A, Alpermann T, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28:241–247. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada H, Harada Y, Tanaka H, Kimura A, Inaba T. Implications of somatic mutations in the AML1 gene in radiation-associated and therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:673–680. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller PG, Glembotsky AC, Gandhi MJ, Cummings CL, Pirola CJ, Marta RF, Kornblihtt LI, Drachman JG, Molinas FC. Low Mpl receptor expression in a pedigree with familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia and a novel AML1 mutation. Blood. 2005;105:4664–4670. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A, French SL, Tekotte H, Yerlikaya S, Stahl M, Perepelkina MP, Tyers M, Rougemont J, Beyer AL, Loewith R. Sch9 regulates ribosome biogenesis via Stb3, Dot6 and Tod6 and the histone deacetylase complex RPD3L. EMBO J. 2011;30:3052–3064. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa M, Asai T, Saito T, Yamamoto G, Seo S, Yamazaki I, Yamagata T, Mitani K, Chiba S, Ogawa S, et al. AML-1 is required for megakaryocytic maturation and lymphocytic differentiation, but not for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells in adult hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2004;10:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nm997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob B, Osato M, Yamashita N, Wang CQ, Taniuchi I, Littman DR, Asou N, Ito Y. Stem cell exhaustion due to Runx1 deficiency is prevented by Evi5 activation in leukemogenesis. Blood. 2009:1610–1620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan M, Snyder TM, Corces-Zimmerman MR, Vyas P, Weissman IL, Quake SR, Majeti R. Clonal evolution of preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells precedes human acute myeloid leukemia. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:149ra118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juban G, Giraud G, Guyot B, Belin S, Diaz JJ, Starck J, Guillouf C, Moreau-Gachelin F, Morle F. Spi-1 and Fli-1 directly activate common target genes involved in ribosome biogenesis in Friend erythroleukemic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2852–2864. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01435-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Roberts AW, Metcalf D, Alexander WS. Hematopoietic stem cell deficiencies in mice lacking c-Mpl, the receptor for thrombopoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1195–1200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loven J, Orlando DA, Sigova AA, Lin CY, Rahl PB, Burge CB, Levens DL, Lee TI, Young RA. Revisiting global gene expression analysis. Cell. 2012;151:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan JK, Speck NA. RUNX1 mutations in clonal myeloid disorders: from conventional cytogenetics to next generation sequencing, a story 40 years in the making. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16:77–91. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v16.i1-2.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud J, Wu F, Osato M, Cottles GM, Yanagida M, Asou N, Shigesada K, Ito Y, Benson KF, Raskind WH, et al. In vitro analyses of known and novel RUNX1/AML1 mutations in dominant familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myelogenous leukemia: implications for mechanisms of pathogenesis. Blood. 2002;99:1364–1372. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoda L, Osato M, Yamashita N, Jacob B, Chen LQ, Yanagida M, Ida H, Wee HJ, Sun AX, Taniuchi I, et al. Runx1 protects hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells from oncogenic insult. Stem cells. 2007;25:2976–2986. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi A, Barreyro L, Steidl U. Concise review: preleukemic stem cells: molecular biology and clinical implications of the precursors to leukemia stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:143–150. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne EM, Virgilio M, Narla A, Sun H, Levine M, Paw BH, Berliner N, Look AT, Ebert BL, Khanna-Gupta A. L-Leucine improves the anemia and developmental defects associated with Diamond-Blackfan anemia and del(5q) MDS by activating the mTOR pathway. Blood. 2012;120:2214–2224. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-382986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, Chen WC, Brandwein JM, Gupta V, Kennedy JA, Schimmer AD, Schuh AC, Yee KW, et al. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014;506:328–333. doi: 10.1038/nature13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signer RA, Magee JA, Salic A, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells require a highly regulated protein synthesis rate. Nature. 2014;509:49–54. doi: 10.1038/nature13035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonnet AJ, Nehme J, Vaigot P, Barroca V, Leboulch P, Tronik-Le Roux D. Phenotypic and functional changes induced in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells after gamma-ray radiation exposure. Stem cells. 2009;27:1400–1409. doi: 10.1002/stem.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar GP, Kerr WG, Zeigler FC, Hess D, Donahue C, de Sauvage FJ, Eaton DL. Role of c-mpl in early hematopoiesis. Blood. 1998;92:4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W-J, Sullivan MG, Legare RD, Hutchings S, Tan X, Kufrin D, Ratajczak J, Resende IC, Haworth C, Hock R, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 (AML1) causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukamia (FPD/AML) Nature Genet. 1999;23:166–175. doi: 10.1038/13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Downing JR. Haploinsufficiency of AML1 results in a decrease in the number of LTR-HSCs while simultaneously inducing an increase in more mature progenitors. Blood. 2004;104:3565–3572. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JL, Hou HA, Chen CY, Liu CY, Chou WC, Tseng MH, Huang CF, Lee FY, Liu MC, Yao M, et al. AML1/RUNX1 mutations in 470 adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic implication and interaction with other gene alterations. Blood. 2009;114:5352–5361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng T, Thomas G, Mercer CA. Growth control and ribosomopathies. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2013;23:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter MJ, Shen D, Shao J, Ding L, White BS, Kandoth C, Miller CA, Niu B, McLellan MD, Dees ND, et al. Clonal diversity of recurrently mutated genes in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2013 doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr MR, Binnewies M, Flach J, Reynaud D, Garg T, Malhotra R, Debnath J, Passegue E. FOXO3A directs a protective autophagy program in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;494:323–327. doi: 10.1038/nature11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, Miller CA, Larson DE, Koboldt DC, Wartman LD, Lamprecht TL, Liu F, Xia J, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150:264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, McLellan MD, Johnson KJ, Wendl MC, McMichael JF, Schmidt HK, Yellapantula V, Miller CA, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young DW, Hassan MQ, Pratap J, Galindo M, Zaidi SK, Lee SH, Yang X, Xie R, Javed A, Underwood JM, et al. Mitotic occupancy and lineage-specific transcriptional control of rRNA genes by Runx2. Nature. 2007;445:442–446. doi: 10.1038/nature05473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Mazor T, Huang H, Huang HT, Kathrein KL, Woo AJ, Chouinard CR, Labadorf A, Akie TE, Moran TB, et al. Direct recruitment of polycomb repressive complex 1 to chromatin by core binding transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2012;45:330–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentner GE, Saiakhova A, Manaenkov P, Adams MD, Scacheri PC. Integrative genomic analysis of human ribosomal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4949–4960. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zharlyganova D, Harada H, Harada Y, Shinkarev S, Zhumadilov Z, Zhunusova A, Tchaizhunusova NJ, Apsalikov KN, Kemaikin V, Zhumadilov K, et al. High frequency of AML1/RUNX1 point mutations in radiation-associated myelodysplastic syndrome around Semipalatinsk nuclear test site. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2008;49:549–555. doi: 10.1269/jrr.08040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.