Abstract

The Fas-FasL effector mechanism plays a key role in cancer immune surveillance by host T cells, but metastatic human colon carcinoma often uses silencing Fas expression as a mechanism of immune evasion. The molecular mechanism under FAS transcriptional silencing in human colon carcinoma is unknown. We performed genome-wide ChIP-Sequencing analysis and identified that the FAS promoter is enriched with H3K9me3 in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region is significantly higher in metastatic than in primary cancer cells, and is inversely correlated with Fas expression level. We discovered that verticillin A is a selective inhibitor of histone methyltransferases SUV39H1, SUV39H2 and G9a/GLP that exhibit redundant functions in H3K9 trimethylation and FAS transcriptional silencing. Genome-wide gene expression analysis identified FAS as one of the verticillin A target genes. Verticillin A treatment decreased H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter and restored Fas expression. Furthermore, verticillin A exhibited greater efficacy than Decitabine and Vorinostat in overcoming colon carcinoma resistance to FasL-induced apoptosis. Verticillin A also increased DR5 expression and overcame colon carcinoma resistance to DR5 agonist drozitumab-induced apoptosis. Interestingly, verticillin A overcame metastatic colon carcinoma resistance to 5-Fluouracil in vitro and in vivo. Using an orthotopic colon cancer mouse model, we demonstrated that tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic T lymphocytes are FasL+ and FasL-mediated cancer immune surveillance is essential for colon carcinoma growth control in vivo. Our findings determine that H3K9me3 of the FAS promoter is a dominant mechanism underlying FAS silencing and resultant colon carcinoma immune evasion and progression.

Keywords: H3K9 trimethylation, Fas, FasL, Immune escape, 5-Fluorouracil, verticillin A, Histone methyltransferase

Introduction

Fas is a member of the death receptor superfamily. Despite other “non-apoptotic” cellular responses emanating from its signaling (1), the major and best known function of Fas is apoptosis (2-8). Fas is expressed on the tumor cell surface, and its physiological ligand, FasL, is expressed on activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). CTLs are essential for eliminating virus infected cells and malignant cells in the host. CTLs destruct target cells primarily through one of two effector mechanisms: 1) perforin-mediated granzyme delivery following exocytosis of cytotoxic granule, and 2) FasL–induced apoptosis. Germline and somatic mutations or deletions of FAS or FASL gene coding sequences in humans lead to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) (9, 10). ALPS patients also exhibited increased risk of both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cancers (9, 11). Furthermore, FAS and FASL gene promoter polymorphisms are associated with decreased Fas expression level and increased risk of both hematopoietic malignancies and non-hematopoietic carcinoma development in humans (12-14). The Fas protein level is high in normal human colon tissues. In human primary colorectal carcinoma (CRC), however, the Fas protein level is generally lower as compared to normal colon tissues, and complete loss of Fas protein is often observed in human metastatic CRC (15, 16). Furthermore, Fas-mediated apoptosis exerted by the cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) is an important contributor of tumor regression, and acquisition of resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis is linked to recurrence and adverse prognosis in human CRC patients (17, 18). These observations thus strongly suggest that human CRC cells use silencing Fas expression as a key mechanism to escape from host immune surveillance. The regulation of Fas expression has been subject of extensive studies, and it is clear that Fas expression is regulated by both transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms (19-21). However, the molecular mechanism underlying FAS silencing in metastatic CRC cells (15, 16) remains to be determined. Furthermore, although Fas is a death receptor that mediates the extrinsic apoptosis pathway, interestingly, it has been shown that Fas also mediates colon carcinoma cell sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) (22, 23). 5-FU is the standard therapy for human CRC patients. However, acquisition of resistance to 5-FU is often inevitable in human CRC patients (24). Therefore, novel chemotherapeutic agent that can effectively overcome metastatic human CRC 5-FU resistance is in urgent need.

Covalent modifications of DNA and histones, the two core components of eukaryotic chromatin, are the two major mechanisms of epigenetic regulation of gene expression. The methylation of lysine residues in histones, particularly in the N-terminal tails of histones H3 and H4 of the chromatin, play a fundamental role in the regulation of gene expression through modulating chromatin structure. Histone methyltransferases (HMTase) catalyze the methylation of histones to modify chromatin structure, thereby influencing gene expression patterns during cellular differentiation and embryonic development. Recent studies have firmly established a fundamental role of aberrant HMTase activity and human diseases, particularly human cancers (25). Unlike genetic mutations of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, which are permanent alterations in the cancer genome, histone methylation is a reversible process, which has made HMTases attractive molecular targets for cancer therapy. Thus, elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying HMTase-mediated tumor suppressor gene expression regulation and the use of HMTase inhibitors to induce re-expression of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes can potentially lead to suppression of cancer growth or sensitization of cancer cells to specific therapeutic agents (25-29). DNMT and HDAC inhibitors have been under extensive development for human cancer therapy for the last two decades (30), in contrast, identification and development of HMTase inhibitors as therapeutic agents are still in its infancy (31-33). Furthermore, the specific HMTase targets associated with cancer progression remain to be determined.

In an attempt to identify new anticancer drug leads from nature, we screened wild mushroom extracts and identified verticillin A as a potent anticancer agent in vitro (34) and in vivo (35). Here, we report the discovery of verticillin A as a selective HMTase inhibitor that selectively inhibits SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a and GLP to inhibit H3K9me3 in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. Furthermore, we performed genome-wide H3K9me3 profiling in combination with genome-wide gene expression analysis using verticillin A as a H3K9me3 inhibitor, and identified FAS as a direct target of H3K9me3 in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. SUV39H1 SUV39H2 and G9a/GLP have redundant functions in H3K9 trimethylation and FAS silencing in the metastaic human colon carcinoma cells. Our data indicate that H3K9me3-mediated FAS transcription silencing is a major mechanism by which colon cancer cells use to evade host cancer immune surveillance and verticillin A is a new selective HMTase inhibitor that inhibits H3K9me3 to restore Fas expression to suppress colon cancer cell immune escape and chemoresistance.

Materials and Methods

Human cancer cells

Human CRC cell lines LS411N and SW620 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). ATCC has characterized these cells by morphology, immunology, DNA fingerprint, and cytogenetics. LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were selected from LS411N and SW620 cells, respectively, by culturing cells with increasing doses of 5-FU. Murine Colon26 cells were kindly provided by Dr. William E. Carson, III (Ohio State University, Columbus, OH).

Analysis of H3K9 methylation and Western blotting analysis

Cells were incubated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) containing protease inhibitors for 30 min. Cells were then centrifuged for 5 min, and the pellet was resuspended in 90 μl 0.1M HCl and incubated on ice for 30 min. The supernatant was neutralized with 10 μl 1M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0. The extract was then resolved in standard protein gels, and the blot was probed with antibodies specific for H3K9me2 (Active motif) and H3K9me3 (Abcam). The blot was reprobed with anti-H3 (Cell Signaling), which was used as the normalization control.

Inhibition of HMTase in vitro

Verticillin A was tested in 10-dose IC50 mode with 3-fold serial dilution starting at 10 μM at Reaction Biology Corp (Malvern, PA). SAH (S-(5'-Adenosyl)-L-homocysteine) was used as a positive control in each assays and tested in a 10-dose IC50 mode with 3-fold serial dilution starting at 100 μM. Reactions were carried out at 1 μM 3H-S-adenosyl-methionine as substrate.

DNA methylation analysis

Genomic DNA was purified using DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sodium bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA was performed using a DNA Modification Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Methylation-sensitive PCR were carried out according to standard PCR procedures. The PCR primers were listed in Table S1.

DNA microarray

The quality of RNA was analyzed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and assured by a RNA Integrity Number (RIN) ≥ 7. The Human Gene 2.0ST array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA), which covers 30,654 coding transcripts, was used for the gene expression profiling. Total RNA samples were processed using the Ambion WT Expression Kit (Life Technologies, Calsbad, CA) and GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling kit (Affymetrix). The synthesized sense strand cDNAs were then fragmented and biotin-labeled using GeneChip WT Terminal Labeling kit. The labeled cDNAs were hybridized onto the arrays using Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 systems according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The expression data were imported into Partek GS version 6.6 using standard import tool with GC-RMA normalization. The differential expressions were calculated using ANOVA of Partek package.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were carried out using anti-H3K9me3 antibody (Abcam), H3K9ac (Cell Signaling), or RNA Polymerase II (Santa Cruz) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fas promoter DNA was detected by PCR using promoter DNA-specific primers as listed in Table S1.

ChIP-Sequencing

Native chromatin was prepared from LS411N-5FU-R cells and digested with micrococcal nuclease to generate mononucleosomes using the Simple ChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Chromatin fragments were then incubated with anti-H3K9me3 antibody (Abcam) and the chromatin-antibody complexes were isolated using Protein A agarose and salmon sperm DNA (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ChIP DNA fragments were then prepared using the TruSeq ChIP Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) and sequenced using High-Seq 2500. Sequence reads in the FASTQ format were generated by the Illumina pipeline CASAVA 1.8.2, and were analyzed using MACS 1.4.2 as described (36). Peaks were annotated using in-house scripts and genes that have a peak in a promoter were fed into Panther to perform functional analysis.

Correlation between H3K9me3 and gene expression analysis

Normalized read depths in wiggle files generated by MACS were used to generate window enrichment of 200 bp with step of 100 bp using an in-house script. The UCSC genome graphs plotted the overall enrichment. The maximum enrichment of windows from 4k bp upstream and 1k bp downstream of transcription initiation site in a gene was correlated to gene expression. For each bin of gene expression, the distribution of ChIP-seq enrichment was drawn in a box plot using R.

Cell surface death receptor analysis

LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were plated at 1×105 cells/well in 24-well plates. Cells were then treated with 0, 20, or 50 nM verticillin A for 24 hours. Cells were harvested and stained with human anti-DR4 (TRAIL-R1, H5101, Alexis Biochemical) or anti-DR5 (TRAIL-R2, H5201, Alexis Biochemical) and analyzed using flow cytometry. Fas cell surface expression was analyzed in verticillin treated or untreated cells using human anti-Fas antibody (Biolegend).

Cell viability assays

Cell viability assays were performed using the MTT cell proliferation assay kit (ATCC, Manassas, VA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Apoptosis analysis

Cells were treated with verticillin A (20 nM), MegaFasL (250 ng/ml), or drozitumab (500 ng/ml) or both for 24h. Both floating and adherent cells were then collected and incubated with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptosis was calculated by the formula: % apoptosis = % PI+ and AnnexinV+ cells - % PI+ and Annexin V+ cells in the control group.

Gene silencing

A set of four human Fas-specific siRNAs were obtained from Qiagen. W620-5FU-R cells were transiently transfected with these set of four siRNAs and analyzed for Fas expression by RT-PCR. One Fas siRNA (Cat # S100000637) was used to silence Fas expression for functional studies. SW620-5FU-R cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at 2.5×105 cells/well with scramble (200 nM) or Fas (200 nM) siRNA for 24 hours. Cells were then harvested and replated at 2×104 cells/well. Cells were then treated with or without verticillin A (20 nM) and MegaFasL (250ng/mL) for 24 hours. Cells were collected and analyzed for cell death by staining with Annexin V and PI. For sensitivity to 5-FU and verticillin A, cells were treated with or without verticillin A (20nM) and 5-FU (1 μg/mL) for 72 hours and analyzed for cell death by staining with Annexin V and PI and flow cytometry analysis. G9a-, SUV39H1- and SUV39H2-specific siRNAs were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotech (Cat# sc-43777, sc-38463 and sc-106822). SW620-5FU-R cells were transfected as described above. Cells were then analyzed for G9a, SUV39H1, SUV39H2 and Fas expression using real-time RT-PCR. Acidic extracts were also prepared from these cells and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-H3K9me3 antibody (Abcam).

Orthotopic murine CRC mouse model

Mouse (BALB/c) was continuously anesthetized with isoflurane (1-3% in oxygen). A small abdominal incision at the right side near the rear leg was made and the cecum identified with sterile gauze. Tumor cells (2×105 cells in 20 μl saline) were injected into the cecal wall from the serosal side using a sterile tuberculin syringe. The abdomen is closed with wound clips.

Human CRC xenograft mouse model

SW620-5FU-R cells were injected into nude mice s.c. at a dose of 3.5×105 cells/mouse. Five days later, tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into 4 groups. The tumor-bearing mice were injected i.v. with saline (control, n=5), 5-FU (25 mg/kg body weight, n=5), verticillin A (1mg/kg body weight, n=5), or 5-FU plus verticillin A (n=5) at days 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13. Tumor size was measured after each treatment. Mice were sacrificed at day 15 after tumor transplant. Serums were collected and analyzed for liver enzyme profiles at the Georgia Laboratory Animal Diagnostic Service (Athens, GA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Student’s t test. A p <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Verticillin A is a selective histone methyltransferase inhibitor

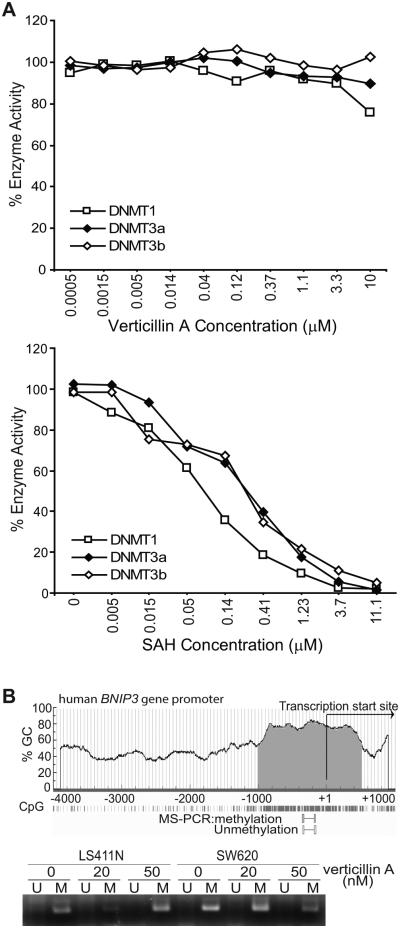

In a 3-year effort to identify natural anticancer agents, we identified the natural small molecule verticillin A (Fig. S1) as an agent with potent activity against human cancer cells but low toxicity to normal human cells (35). Investigating verticillin A mechanism of action in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells identified BNIP3 as a target of verticillin A. We previously observed that verticillin A dramatically increases BNIP3 expression level in human colon carcinoma cells and that silencing BNIP3 decreased verticillin A-induced apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells, suggesting that verticillin A induces tumor cell apoptosis at least partially through up-regulating BNIP3 expression (35). However, the BNIP3 promoter DNA is hypermethylated in human colon carcinoma tissues and in human colon carcinoma cell lines (35, 37). Our initial hypothesis was that verticillin A acts as a DNA methylation inhibitor since it activates transcription of DNA methylation-silenced BNIP3 and a panel of other DNA methylation-silenced genes in human colon carcinoma cells (35). DNA methylation is carried out by DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b. To test this hypothesis, we then examined the effects of verticillin A on DNMT enzymatic activity in vitro and observed that verticillin A exhibited no inhibitory effect on the enzymatic activity of DNMT1, DNMT3a or DNMT3b (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, verticillin A treatment did not result in DNA demethylation of the BNIP3 promoter region in human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 1B). Therefore, our data suggest that verticillin A activates DNA methylation-silenced BNIP3 transcription through a DNA demethylation-independent mechanism.

Figure 1. Verticillin A activates DNA methylation-silenced BNIP3 transcription without inducing DNA demethylation.

A. Verticillin A was tested in a 10-dose IC50 mode with 3-fold serial dilutions starting at 10 μM using 3H-S-adenosyl-methionine as substrate with recombinant DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b in vitro. The enzyme activity was then analyzed and plotted against verticillin A concentrations. IC50s were calculated using the Graphpad Prism program. Assays were performed three times with three lots of verticillin A. Shown are representative results of one of the three independent assays (top panel). Bottom panel: S-Adenosyl methionine (SAH) was used as a positive control also in a 10-dose IC50 mode with 3-fold serial dilutions starting at 100 μM with recombinant DNMT1, DNMT3a and DNMT3b as in the top panel. Only the dose range from 11.1 to 0 μM is shown. Shown are representative results of one of the three independent assays. B. Top panel: The human BNIP3 promoter structure is shown with the CpG island indicated. Bottom panel: LS411N and SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A at the indicated concentrations for 3 days and analyzed for BNIP3 promoter DNA methylation by methylation specific-PCR using primers located in the indicated region in the top panel; U: unmethylated, and M: methylated.

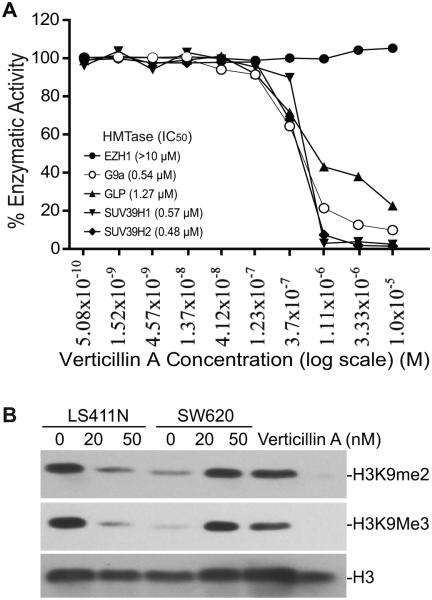

To identify the molecular target of verticillin A, we screened the effects of verticillin A on HMTase activity. We used a 10-dose IC50 mode with 3-fold serial dilutions starting at 10 uM verticillin A to determine whether verticillin A inhibits human histone methyltransferase activity. Among the known human HMTases tested, verticillin A selectively inhibits SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a, GLP (Fig. 2A), and to a less degree MLL1 and NSD2 (Table 1). However, verticillin A, at the highest tested dose (10 µM) exhibited no inhibitory activity towards the other 15 HMTases (Table 1). Our data thus suggest that verticillin A is a selective inhibitor for SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a, GLP, MLL1 and NSD2.

Figure 2. Verticillin A is a selective HMTase inhibitor.

A. Verticillin A selectively inhibits SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a and GLP in vitro. Verticillin A was tested in a 10-dose IC50 mode with 3-fold serial dilutions using 3H-S-adenosyl-methionine as substrate with recombinant human HMTases as indicated. The enzyme activity was then analyzed and plotted against verticillin A concentrations. IC50s were calculated using the Graphpad Prism program. Assays were performed three times with three lots of verticillin A. Shown are representative results of one of three independent assays. B. Verticillin A inhibits H3K9 methylation in human CRC cells. Metastatic human CRC LS411N and SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A at the indicated concentrations for 2 days. Histone acidic extracts were prepared and analyzed by Western blot with antibodies specific for the indicated methylated lysines of histone 3. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-H3 antibody as a loading control.

Table 1.

Verticillin A IC50 for HMTase

| HMTase | Verticillin A (IC50 μM) |

SAH (IC50 μM) |

|---|---|---|

| DOT1 | NI | 1.99 |

| EZH2 | NI | 46.8 |

| MLL1 | 3.08 | 2.36 |

| MLL2 | NI | 131 |

| MLL3 | NI | 9.69 |

| MLL4 | NI | 7.61 |

| NSD2 | 4.13 | 5.05 |

| PRMT1 | NI | 0.34 |

| PRMT3 | NI | 1.59 |

| PRMT4 | NI | 0.358 |

| PRMT5 | NI | 0.775 |

| PRMT6 | NI | 0.295 |

| SET7 | >10 | 33.5 |

| SET8 | NI | >100 |

| SETMAR | >10 | 3.07 |

| SMYD2 | >10 | 1.22 |

| EZH1 | NI | >100 |

| G9a | 0.538 | 4.45 |

| GLP | 1.27 | 0.345 |

| SUV39H1 | 0.573 | >100 |

| SUV39H2 | 0.481 | 57.3 |

NI: No inhibition at 10 μM concentration

Verticillin A inhibits histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation

SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a and GLP all mediate methylation of histone H3 at lysine 9 (H3K9) (38, 39). SUV39H1 and SUV39H2 have redundant functions and mediate di- and tri-methylation of H3K9 within heterochromatin regions (38), whereas G9a and GLP form a heteromeric complex to catalyze H3K9 di-methylation (H3K9me2) (39), we therefore reasoned that if verticillin A inhibits SUV39H1/2 and G9a/GLP, then the global H3K9 methylation level should be decreased. To test this notion, LS411N and SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A and analyzed for overall H3K9 methylation. Histone acidic extracts were prepared from the untreated and treated cells and analyzed by Western blotting with H3K9Me2- and H3K9me3-specific antibodies. H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 levels were diminished by verticillin A in the tumor cells (Fig. 2B).

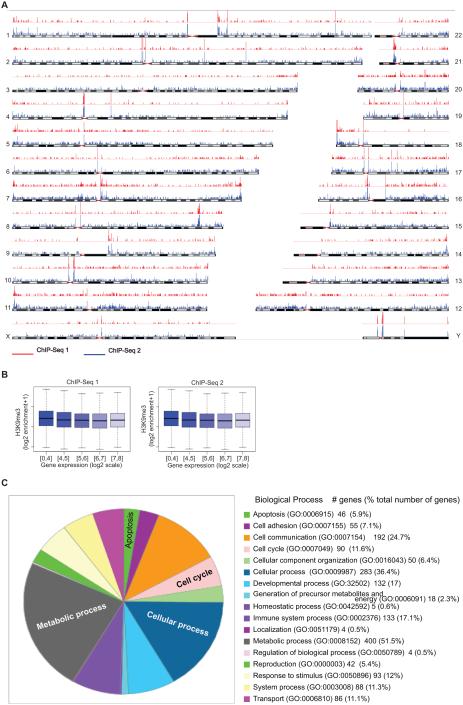

Genome-wide H3K9me3 distribution profile in human CRC cells

To investigate H3K9me3 distribution in human CRC cells in a genome-wide unbiased fashion, we generated native chromatin from LS411N-5FU-R cells containing primarily mononucleosomes by micrococcal muclease (MNase) digestion and performed ChIP with H3K9me3-specific antibody. The ChIP DNA fragments were sequenced with the Hi-Seq 2500 system. A total of approximately 36 million sequence reads of H3K9me3 were generated and mapped to human genome by bioinformatics tools (Fig. 3A). It is clear that H3K9me3 markers are distributed all over the genome in a relatively even fashion without significant H3K9me3-enriched clusters in certain chromosome regions (Fig. 3A). Approximately 8000 H3K9me3 peaks were identified. Because verticillin A exhibits potent inhibitory activity against H3K9me3, ChIP-Seq analysis of verticillin A-treated cells is technically challenging and was not performed. Nevertheless, we mapped H3K9me3 to the human genome in human colon carcinoma cells.

Figure 3. Genome-wide H3K9me3 and gene expression profiles in metastatic human CRC cells.

A. Chromatin of LS411N-5FU-R cells was digested with micrococcal nuclease to generate mononucleosomes. The nucleosomes were incubated with H3K9me3-specific antibody and subjected to ChIP. The ChIP DNA fragments were sequenced with the Hi-Seq 2500 system, and the sequence reads of H3K9me3 were generated and mapped to human chromosomes using bioinformatics tools. Shown are two independent ChIP-Seq experiments (red and blue lines, p<0.01). B. Genome-wide correlation analysis of H3K9me3 and gene expression. Normalized H3K9me3 read depths in wiggle files generated by MACS were used to generate window enrichment of 200 bp with step of 100 bp using an in-house script. The maximum enrichment of windows in 4k bp upstream to to 1k bp downstream of 5’ UTR of a gene was correlated to gene expression level. For each bin of gene expression, the distribution of ChIP-seq enrichment was drawn in a box plot using R. C. Identification of verticillin A target genes. LS411N-5FU-R cells were treated with verticillin A and analyzed by DNA microarray. The genes whose expression was changed by a 1.5 fold were selected and fed into Panther program to functionally group the genes based on their functions in biological process.

Genome-wide gene expression profile in human CRC cells

To determine the genome-wide gene expression profiles, we performed genome-wide gene expression analysis in LS411N-5FU-R cells using an Affymetrix Human Gene 2.0 ST Array. The entire data set is available from GEO database (accession # GSE51262). To identify genes whose expression levels are regulated by H3K9 methylation, we also treated LS411N-5FU-R cells with verticillin A and analyzed the genome-wide gene expression. Genes whose expression was significantly changed as compared to untreated cells were identified by a combination of ANOVA (p<0.01), intensity changes (≤1.5 fold), and minimum expression intensity (≥1.5). A total of 820 genes with identified. These verticillin A target genes were then functionally grouped. As expected, we identified a large set of genes with known functions in apoptosis and cell cycle regulation (Fig. 3C). The entire dataset is available in NCBI GEO database (accession # GSE51262: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE51262].

Genome-wide correlation of H3K9me3 and gene expression

Because H3K9me3 is a hallmark of transcriptionally repressive chromatin (25), we reasoned that there should exist an inverse correlation between H3K9me3 level and gene expression in the genome-wide level. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the expressed genes by quantitating the levels of H3K9me3 in the gene promoter region (1 kb downstream to 4 kb upstream of the gene transcription initiation site) and mRNA level as determined by genome-wide gene expression analysis as described above. Surprisingly, although a general trend of inverse correlation was observed, no statistically significant correlation was observed between H3K9me3 level and gene expression in the global level (Fig. 3B).

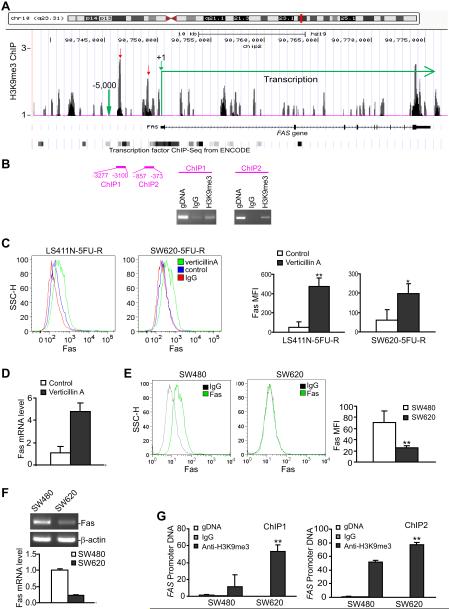

FAS is silenced by its promoter H3K9me3

The lack of inverse correlation between H3K9me3 and gene expression in the genome scale is not totally surprising since some of the suppressive effects of H3K9me3 may be secondary. In addition, some of the genes may be completely silenced by H3K9me3 and thus are not included for analysis. However, this inverse correlation should be true at least for some genes. Therefore, we then compared the gene expression and H3K9me3 profiles to identify individual genes whose expression is up-regulated by verticillin A and whose promoter region is enriched with H3K9me3. FAS is identified as such a gene. ChIP-Seq analysis identified two H3K9me3 peak clusters in the FAS promoter region (Fig. 4A), and we confirmed these two H3K9me3 locations by individual ChIP analysis of the human FAS promoter region using H3K9me3-specific antibody (Fig. 4B). Fas is undetectable in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells and is up-regulated by verticillin A as revealed by DNA microarray (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, analysis of cell surface Fas receptor indicated that verticillin A significantly increased Fas receptor level (Fig. 4C) and Fas mRNA level (Fig. 4D) in the metastatic human CRC cells.

Figure 4. H3K9me3 mediates Fas silencing in metastatic human CRC cells.

A. A screen shot of the normalized H3K9me3 data of ChIP-Seq as described in Fig. 3A uploaded in the UCSC genome browser. The top panel represents chromosome 10 with FAS location indicated by a red vertical line. Bottom panel: The FAS gene structure with H3K9me3 clusters mapped to the gene. The mapped transcription factor binding sites as determined by ChIP-Seq from ENCODE are indicated. H3K9me3 peaks in the FAS promoter region are indicated by the red arrows. B. Analysis of H3K9me3 in the FAS promoter region. The two H3K9me3 clusters as shown in A were validated by ChIP analysis of the FAS promoter region using H3K9me3-specific antibody. C. Verticillin A restores Fas expression in metastatic human CRC cells. LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were cultured in the absence (control) or presence of verticillin A (20 nM) for 2 days. Cells were stained with IgG isotype control (IgG) or a Fas-specific mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. Red line: IgG staining, Blue line: Fas intensity of untreated control cells, Green line: Fas intensity of verticillin A-treated cells. The Fas mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) were quantified and presented at the right panel. Column: mean, bar: SD. * p<0.01, * p<0.05. D. SW620-5FU-R cells were cultured in the absence (control) or presence of verticillin A (20 nM) for 2 days and analyzed for Fas mRNA level by real time RT-PCR. E. Fas expression level in primary and metastatic human CRC cells. SW480 and SW620 cells were stained with IgG or Fas-specific mAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative images of the Fas expression level. The MFI of Fas in SW480 and SW620 cells as shown in the left two panels were quantified and presented at the right. F. Fas mRNA levels in the primary and metastatic human colon carcinoma cells as determined by RT-PCR (top panel) and real-time RT-PCR (bottom panel). G. H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region in primary and metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. The two H3K9me3 clusters as shown in B were analyzed by ChIP using H3K9me3-specific antibody and FAS promoter-specific PCR. IgG was used as negative control for ChIP. The ChIP DNA was quantified by real-time PCR using 2 ng human colon cancer cell genomic DNA as positive control. The genomic DNA level was set at 1.

Next, we sought to determine the relationship between Fas expression and its promoter H3K9me3 level in human colon carcinoma cells. SW480 and SW620 is a pair of matched primary and metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. SW480 was established from primary colon carcinoma, whereas SW620 was derived from lymph node metastases of the same patients. Both cell lines were established prior to chemotherapy (40). The rationale is that if H3K9me3 controls Fas expression in human colon cells, then metastatic SW620 cells should have higher degree of H3K9me3 level than the primary colon carcinoma SW480 cells. Flow cytometry analysis indicates that Fas is highly expressed in SW480 cells, but is silenced in SW620 cells (Fig. 4E). RT-PCR analysis indicated that Fas mRNA level is also higher in SW620 cells in SW480 cells (Fig. 4F). ChIP analysis shows that H3K9me3 level is significantly higher in both regions of the FAS promoter in SW620 cells as compared to that in SW480 cells (Fig. 4G). Thus, we have determined that H3K9me3-mediated FAS transcription silencing is a molecular mechanism of loss of Fas expression in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells.

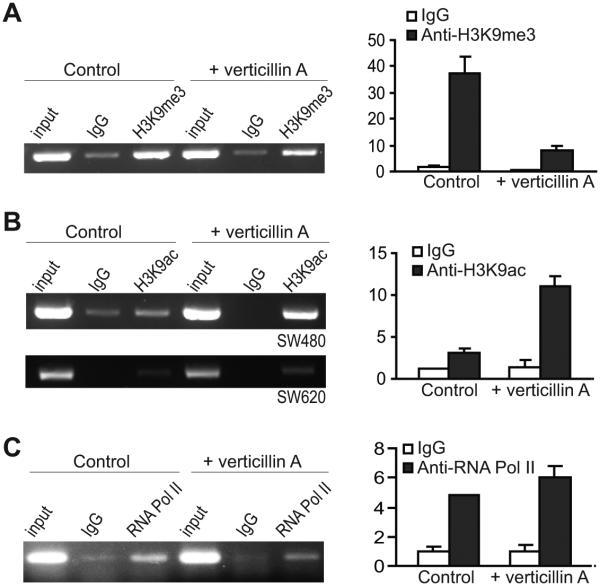

Verticillin A inhibits H3K9me3 at the FAS promoter region

We next sought to determine whether verticillin A affects H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region. SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A for 2 days and analyzed for H3K9me3 level. It is clear that verticillin A treatment decreased H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region SW620 cells (Fig. 5A). It is known that histone acetylation mediates Fas expression in embryonic fibroblasts (20) and H3K9ac is a mark for transcriptionally active chromatin (41). We therefore also analyzed H3K9ac level in the FAS promoter region in human colon carcinoma cells after verticillin A treatment. It is interesting to notice that H3K9ac level is higher in the FAS promoter region in the primary human colon carcinoma SW480 cells than in the metastatic SW620 cells, and verticillin A dramatically increased H3K9ac level in the FAS promoter region in SW480 cells (Fig. 5B). Verticillin A also increased H3K9ac level in the FAS promoter region in the metastatic SW620 cells, albert at a low degree (Fig. 5B). Our initial attempts did not identify an increase in the RNA Pol II level in the FAS promoter region in the human colon carcinoma cells after verticillin A treatment (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Verticillin A treatment decreases H3K9me3 in the FAS promoter region.

A. Left Panel: SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A (50 nM) for 2 days and analyzed for H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region (ChIP 1 region as shown in Fig. 4A and B) by ChIP and semi-quantitative PCR. Right panel: SW620 cells were treated as in the left panel and analyzed for H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region by ChIP and real-time PCR. B. Left panel: SW480 and SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A for 2 days and analyzed for H3K9ac level in the FAS promoter region (ChIP 1 region as shown in Fig. 4A and B) by ChIP and semi-quantitative PCR. Right panel: SW480 cells were treated with verticillin A for 2 days and analyzed for H3K9ac level in the FAS promoter region by ChIP and real-time PCR C. SW620 cells were treated with verticillin A (50 nM) for 2 days and analyzed for RNA Pol II level in the FAS promoter region (ChIP 1 region as shown in Fig. 4A and B) by ChIP and semi-quantitative PCR. Right panel: SW620 cells were treated as in the left panel and analyzed for RNA Pol II level in the FAS promoter region by ChIP and real-time PCR.

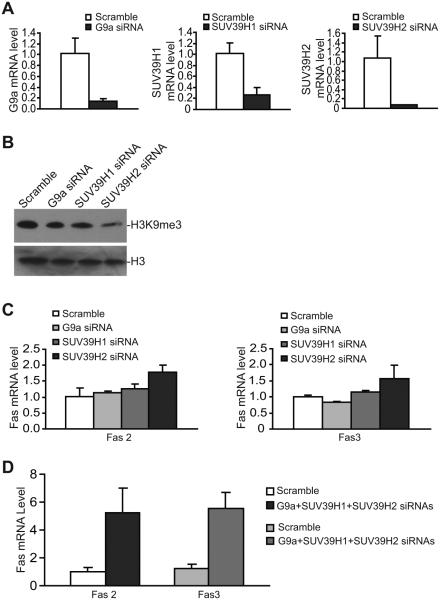

SUV39H1 SUV39H2 and G9a cooperate to catalyze H3K9 trimethylation to silence Fas expression

To determine which of the HMTases mediates H3K9me3-dependent Fas silencing in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells, we silenced SUV39H1, SUV39H2 and G9a expression using gene-specific siRNAs. Because G9a and GLP form a complex, we only silenced G9a expression. The expression levels of all three genes are effectively silenced by gene-specific siRNA (Fig. 6A). Silencing each of these three genes decreased H3K9me3 level in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 6B), suggesting that SUV39H1 SUV39H2 and G9a function in catalyzing H3K9 trimethylation in human colon carcinoma cells. However, silencing each of these three genes only resulted in minimal increase in Fas expression in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 6C). We then hypothesized that SUV39H1 SUV39H2 and G9a may have redundant functions in H3K9 trimethylation in the FAS promoter region. To test this hypothesis, we simultaneously silenced SUV39H1 SUV39H2 and G9a and analyzed Fas expression level. Indeed, silencing these three genes leads to a dramatic increase of Fas expression in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 6D). We thus conclude that SUV39H1 SUV39H2 G9a/GLP catalyze H3K9 trimethylation in the FAS promoter region to silence Fas expression in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells.

Figure 6. G9a SUV39H1 and SUV39H2 cooperate to mediate H3K9 trimethylation and FAS silencing.

A. SW620-5FU-R cells were transiently transfected with scramble, G9a-, SUV39H1-, and SUV39H2-specific siRNA (200 nM), respectively, for approximately 24h and analyzed for the respective mRNA levels as indicated by real time RT-PCR. The Fas mRNA level in scralble siRNA-transfected cells were arbitrarily set at 1. B. Cells as described in A were extracted for histone and analyzed by Western blotting using H3K9me3-specific antibody. H3 was used as normalization control. C. Cells as described in A were also analyzed for Fas expression levels using two Fas-specific PCR primer pairs [Fas 2 and Fas 3 (supplemental table 1)]. D. SW620-5FU-R cells were transiently transfected with scramble siRNA and pooled siRNAs of G9a SUV39H1 and SUV39H2 (200 nM each) for approximately 24h and analyzed for Fas expression using two pairs of Fas PCR primers and real-time RT-PCR.

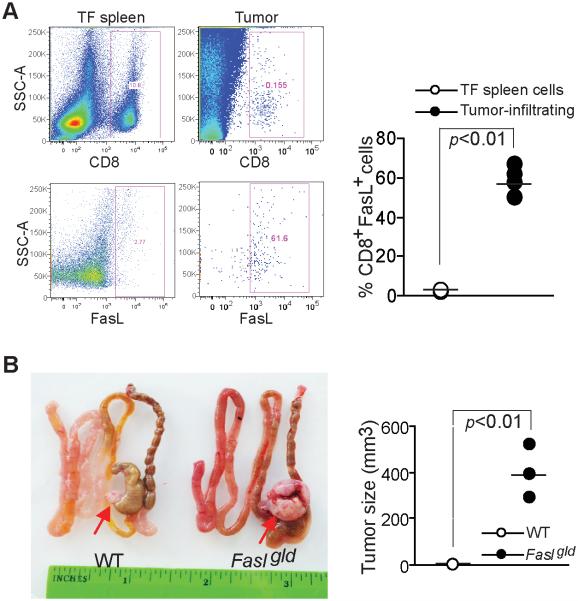

Colon carcinoma growth control in vivo requires FasL

The Fas-FasL effector mechanism plays a key role in cancer immune surveillance by host T cells (18). Our above observations thus suggest that colon carcinoma cells might use H3K9me3-mediated Fas silencing to escape from host cancer immune surveillance. To test this hypothesis, we examined colon carcinoma development in FasL-deficient mice. We first examined FasL expression in tumor-infiltrating CTLs. Tumor-infiltrating CTLs were gated and analyzed for FasL protein level on the cell surface, more than 60% of the tumor-infiltrating CTLs are FasL+ (Fig. 6A), as a negative control, CTLs from tumor-free mice are essentially FasL- (Fig. 7A). Next, mouse colon carcinoma colon26 cells were surgically transplanted into the cecal wall of synergic mice and observed for tumor growth. Significant fast tumor growth was observed in the FasL-deficient Fasgld mice as compared to the wt mice (Fig. 7B). Because FasL is primarily expressed on activated CTLs under physiological conditions (42), our observations thus indicate that FasL-mediated cytotoxicity of host CTLs is a key component of the host cancer immune surveillance system against colon carcinoma development under physiopathological conditions.

Figure 7. Colon carcinoma growth control in vivo requires FasL.

A. FasL expression in tumor-infiltrating CTLs. Tumors were excised from tumor-bearing mice and digested to make single cell suspension. The cells were stained with CD8- and FasL-specific mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. The CD8+ cells were gated and quantified for FasL+ cells. Cells from spleens of tumor-free mice were used as negative control. The % CD8+FasL+ cells were quantified and presented at the right. B. Loss of FasL function results in increased tumor growth. Colon 26 cells were surgically transplanted to the cecal wall of wt and FasLgld mice and tumors were examined 30 days after tumor transplant. The tumor sizes were measured and presented at the right.

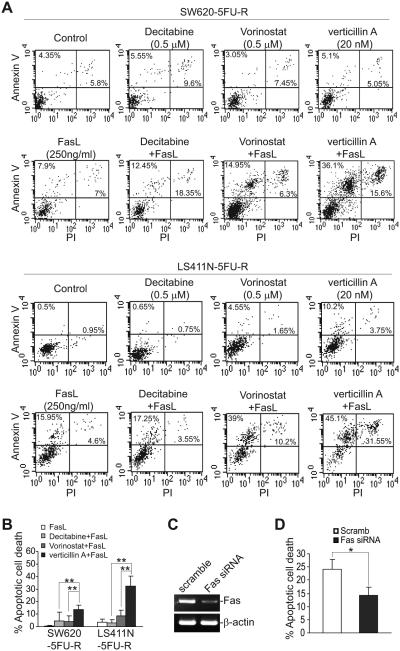

Verticillin A sensitizes metastatic human colon cells to FasL-induced apoptosis.

Resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis is a hallmark of human cancer in general (43), and of metastatic human CRC in particular (15, 44). It is known that epigenetic mechanisms including DNA methylation and histone acetylation modulate Fas transcription (20, 21). Therefore, we sought to determine the relative functions of these epigenetic mechanisms in terms of sensitization of Fas-resistant metastatic colon carcinoma cells to FasL-induced apoptosis. Sublethal doses of verticillin A, decitabine and vorinostat were tested for their ability to sensitize tumor cells to FasL-induced apoptosis in vitro. As expected, both LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were resistant to FasL (Fig. 8A & B), and both decitabine and vorinostat increased the sensitivity of the tumor cells to FasL-induced apoptosis, albeit to a small degree under the conditions tested (Fig. 8B). Verticillin A exhibited significantly greater efficacy than either decitabine or vorinostat in sensitizing the two metastatic human CRC cell lines to FasL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 8A & B).

Figure 8. Verticillin A exhibits greater efficacy than decitabine or vorinostat in sensitizing 5-FU-resistant metastatic CRC cells to FasL-induced apoptosis.

A. SW620-5FU-R and LS411N-5FU-R cells were cultured in the presence of decitabine, vorinostat, verticillin A, and FasL, either alone or in the indicated combinations and doses, for 24h. Cells were then stained with PI and Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are represent images of apoptotic cell death. B. The data shown in A were quantified as 1) % apoptosis = % Annexin V+ treated cells - % Annexin V+ untreated control cells; and 2) % apoptotic cell death= % PI+Annexin V+ treated cells - % PI+Annexin V+ untreated control cells. Column: mean, bar: SD. ** p<0.01. C. SW620-5FU-R cells were transfected with scramble or Fas-specific siRNA (200 nM) overnight and analyzed for Fas mRNA level by RT-PCR. D. The cells as shown in C were then treated with verticillin A (20 nM) and FasL for 24h and analyzed by staining with Annexin V and PI. % apoptotic cell death is calculated as % Annexin V+PI+ cells. * p<0.05.

To determine whether verticillin A sensitized human colon carcinoma cells to FasL-induced apoptosis through Fas up-regulation, SW620-5FU-R cells were transfected with scramble and Fas-specific siRNA. As expected, Fas-specific siRNA diminished Fas expression in the tumor cells (Fig. 8C). Treatment of these transfected cells with verticillin A and FasL revealed that silencing Fas expression diminished SW620-5FU-R cell sensitivity to apoptosis induction by verticillin A and FasL (Fig. 8D). Therefore, verticillin A sensitizes human colon carcinoma cells to FasL-induced apoptosis at least partially through up-regulation of Fas expression.

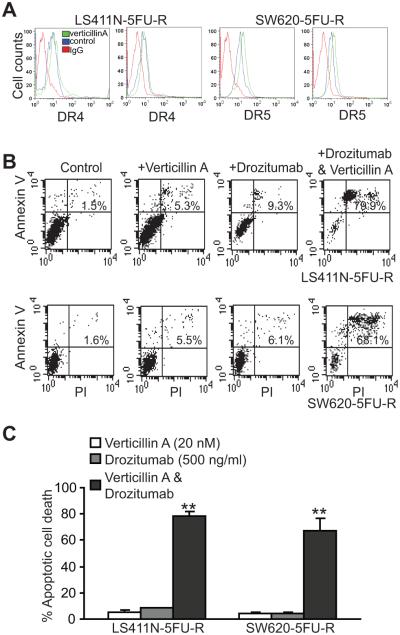

Verticillin A overcomes metastatic human colon carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

TRAIL-induced apoptosis pathway shares similar signaling pathways with the FasL-induced apoptosis pathway (44-46), and plays an important role in suppression of tumor metastasis (47). We next analyzed the effects of verticillin A on TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells. Verticillin A treated did not alter DR4 expression but increased DR5 expression level in both SW620-5FU-R and LS411N-5FU-R cells (Fig. 9A). Consistent with increased DR5 expression level, verticillin A significantly increased SE620-5FUR and LS411N-5FU-R cell sensitivity to Drozitumab (Fig. 9B & C), a DR5 agonist monoclonal antibody (mAb) that has been developed to treat human cancers (44, 48, 49).

Figure 9. Verticillin A up-regulates DR5 expression to increase metastatic human colon carcinoma cells to DR5 agonist antibody-induced apoptosis.

A. The indicated tumor cells were treated with verticillin A for 2 days and analyzed for DR4 and DR5 expression levels by flow cytometry. B. LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were treated with verticillin A (20 nM), Drozitumab (500 ng/ml) or both verticillin A and Drozitumab for 24h and analyzed for apoptosis by staining with Annexin V and PI. C. Quantification of apoptosis. % apoptotic cell death is expressed as % Annexin V+PI+ cells of the treated group - % Annexin V+PI+ cells of untreated control. ** p<0.01.

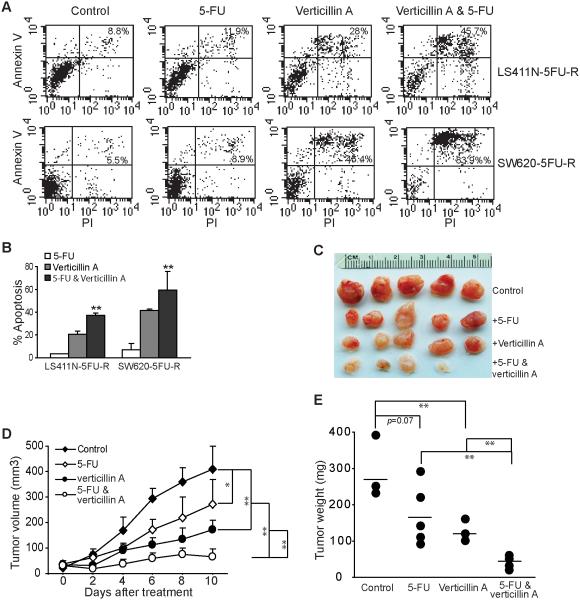

Verticillin A overcomes metastatic human CRC resistance to 5-FU-induced apoptosis in vitro and enhances 5-FU-mediated tumor growth suppression in vivo.

5-FU is the standard therapy for human CRC. However, acquisition of resistance to 5-FU is often inevitable in human CRC patients (24). Although Fas is a death receptor that mediates the extrinsic apoptosis pathway, interestingly, it has been shown that Fas also mediates CRC cell sensitivity to 5-Fluorouracil (22, 23). Furthermore, 5-FU-resistant human CRC cells express similar level of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 (Fig. S2A) and are as sensitive to verticillin A as the parent cell lines (Fig. S2B). Based on these observations, we hypothesized that in addition to its ability to sensitize colon carcinoma cells to FasL-induced apoptosis in vitro and FasL-mediated immune surveillance in vivo, verticillin A should also be effective in overcoming human CRC cell resistance to 5-FU. To test this hypothesis, LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were cultured in the presence of 5-FU, verticillin A or both 5-FU and verticillin A, and analyzed for apoptosis. It is clear that the combined verticillin A and 5-FU treatment induced significantly more apoptotic cell death than either agent alone (Fig. 10A & B). To determine whether this finding can be extended to an in vivo situation, SW620-5FU-R cells were injected into nude mice s.c. Five days later, tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into 4 groups. The tumor bearing mice were injected i.v. with saline, 5-FU, verticillin A, and 5-FU plus verticillin A every two days for ten days. At the dose used, 5-FU and verticillin A both exhibited tumor growth inhibitory activity (Fig. 10C). However, combined verticillin A and 5-FU exhibited the greatest inhibitory activity in terms of tumor size (Fig. 10D) and weight (Fig. 10E), and almost eradicated the established 5-FU-resistant tumor xenograft (Fig. 10C-E).

Figure 10. Verticillin A overcomes metastatic human CRC cell resistance to 5-FU therapy.

A. Verticillin A effectively overcomes metastatic human CRC cell resistance to 5-FU-induced apoptosis. LS411N-5FU-R and SW620-5FU-R cells were cultured in the presence of verticillin A (20 nM), 5-FU (1 µg/ml), or both verticillin A and 5-FU for 3 days. Cells were then stained with PI and Annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry. B. The data shown in A were quantified with the % apoptotic cell death calculated using the formula: % PI+ Annexin V+ treated cells - % PI+ Annexin V+ control cells. Column: mean, bar: SD. **p<0.01. C. Images of tumors from nude mice after the indicated therapy. SW620-5FU-R cells were injected into nude mice s.c. at a dose of 3.5×105 cells/mouse. Five days later, tumor-bearing mice were randomly divided into 4 groups. The tumor-bearing mice were injected i.v. with saline (control, n=5), 5-FU (25 mg/kg body weight, n=5), verticillin A (1mg/kg body weight, n=5), or 5-FU plus verticillin A (n=5) at days 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13. Tumor size was measured after each treatment. Mice were sacrificed at day 15 after tumor transplant. D. Tumor growth kinetics. The differences in tumor volumes were analyzed by t test. The p values are presented at the right. D. Tumors were dissected and weighted after the mice were sacrificed. The line represents mean tumor weight. The tumor weight was analyzed by t test and the p values are presented at the top of the panel.

To determine whether verticillin A sensitized human colon carcinoma cells to 5-FU-induced apoptosis through Fas up-regulation, SW620-5FU-R cells were transfected with scramble and Fas-specific siRNA. As expected, Fas-specific siRNA diminished Fas expression in the tumor cells (Fig. 8C). However, treatment of these transfected cells with verticillin A and 5-FU revealed that silencing Fas expression does not change SW620-5FU-R cell sensitivity to apoptosis induction by verticillin A and 5-FU (Fig. S3). Therefore, verticillin A sensitizes human colon carcinoma cells to 5-FU-induced apoptosis through a Fas-independent mechanism.

Verticillin A exhibits low liver toxicity in vivo

To determine the toxicity of verticillin A, we measured serum liver enzyme profiles in mice after 5-FU therapy. Liver enzymes are diagnostic markers for liver damage. We collected serum from the above four groups of mice and measured liver enzyme and protein levels in the serum. Among all the enzyme analyzed in all four groups, only aspartate transaminase level was modestly increased (Table 2). Therefore, the preliminary assays indicate that verticillin A has minimal liver toxicity at the efficacious dose.

Table 2.

Mouse serum liver profiles*

| Serum Enzyme/Protein Level | Treatment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=3) |

5-FU (n=5) |

Verticillin A (n=5) |

5-FU & verticillin A (n=3) |

|

| ALP (U/L) | 54.8±16.9 | 56.7±24 | 62.8±22 | 51.7±14.2 |

| ALT (U/L) | 34.0±18.5 | 15.3±3.5 | 27.2±7.3 | 49.0±32.9 |

| AST (U/L) | 164±87.7 | 109±63.2 | 154±105.8 | 244.3±152.5 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 127.5±12.9 | 157±26.6 | 122.6±12.7 | 193±37.2 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1±0 | 0.1±0 | 0.06±0.05 | 0.1±0 |

| Total Protein (g/dl) | 5.1±0.2 | 4.9±0.1 | 4.5±0.3 | 4.9±0.2 |

Measurements were performed 2 days after the last treatment

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate transaminase

Discussion

Deregulation of H3K9me3 has been linked to various human cancers (50-52), and multivariate survival analysis showed that H3K9me3 levels are associated with cancer recurrence and poor survival rate in human patients with gastric cancer (53). We performed genome-wide H3K9me3 ChIP-Seq analysis and mapped H3K9me3 locations to the genome in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. Although H3K9 methylation often occurs within heterochromatin regions (38), interestingly, we observed that H3K9me3 marks exist relatively evenly all over the entire genome without significant clusters in a particular chromatin region in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 3A). Our observations may thus suggest that H3K9me3 alone may not be a signature for heterochromatins at least in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells.

H3K9me3 is generally regarded as a mark of transcriptionally repressive chromatin (25). Therefore, it is expected that H3K9me3 marks should be inversely correlated with transcriptionally gene silencing. It is therefore a surprising observation that no correlations exist between gene promoter H3K9me3 and mRNA levels in the genome scale. It is possible that some of H3K9me3-regulated genes may be completely silenced to become undetectable and thus excluded in the correlation analysis. However, correlation analysis of H3K9me3 with mRNA expression levels in verticillin A-treated cells also did not find a correlation between H3K9me3 and gene expression in the genome scale in the metastatic human CRC cells. Therefore, it is possible that H3K9me3 alone may be insufficient to induce a heterochromatin structure to silence gene expression in the genome scale. Instead, H3K9me3 may act in concert with DNA hypermethylation to generate a transcriptionally repressive chromatin structure (54).

Although no genome-wide correlation was observed between H3K9me3 and mRNA expression, examination of individual gene promoter H3K9me3 and mRNA expression levels identified FAS as a target gene of H3K9me3. Two H3K9me3 clusters were identified in the FAS promoter region by genome-wide ChIP-Seq analysis, and validated by ChIP analysis of H3K9me3 in the FAS promoter region in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. DNA microarray study identified Fas as one of the genes whose expression was significantly up-regulated by verticillin A, and we validated that Fas receptor is also significantly increased by verticillin A treatment on the surface of metastatic human colon carcinoma cells. It is known that Fas expression is regulated by its promoter DNA hypermethylation in certain human CRC cells (55). It is also known that Fas transcription is mediated by histone acetylation in embryonic fibroblasts (20). Furthermore, Fas expression can be up-regulated by inhibition of DNA methylation and histone acetylation (21). Here, we show that Fas is silenced by its promoter H3K9me3. Moreover, inhibition of H3K9 methylation with verticillin A exhibits significantly greater apoptosis sensitization effects than inhibition of DNA methylation or histone acetylation. Our data thus suggest that H3K9me3 acts as a dominant epigenetic mechanism over DNA methylation and histone acetylation by which the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells silence Fas expression (15).

Consistent with the notion that H3K9me3 is a dominant epigenetic mechanism underlying FAS transcriptional silencing in metastatic human colon carcinoma cells, verticillin A treatment dramatically decreased H3K9me3 level in the FAS promoter region in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 5A). Interesting, although verticillin A treatment dramatically increased H3K9ac level in the primary human colon carcinoma SW480 cells, verticillin A treatment only induced minimal increase of H3K9ac in the metastatic human colon carcinoma SW620 cells. These observations suggest that lack of H3K9ac and high level of H3K9me3 at the FAS promoter region might be the key mechanisms underlying FAS silencing in metastatic human colon carcinoma.

RNA Pol II association with the FAS core promoter to form transcription preinitiation complex is very inefficient, but supports fast transcription rate in human cancer cells (56). Therefore, FAS transcription rate may be controlled by the level of promoter-bound RNA Pol II and the polymerization rate of RNA Pol II. In this study, our initial attempts failed to identify increased RNA Pol II binding to the FAS promoter in the verticillin A-treated human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 5C) even though verticillin A decreased H3K9me3 level that may likely create a more transcriptionally active promoter structure (Fig 5A). The molecular mechanism underlying the effects of H3K9me3 on RNA Pol II association with the FAS promoter and FAS transcription in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells requires further elucidation.

Systemic analysis of large cohorts of clinical specimens revealed that presence of tumor-specific CTLs in the tumor microenvironment is positively correlated with the absence of early metastasis and increased survival of CRC patients (17, 57, 58). We determined that tumor-infiltrating CTLs are FasL+, and CRC cells grow significantly faster in FasL-deficient mice in vivo, demonstrating a critical role of FasL of CTLs in immune suppression of CRC development under pathological conditions. Therefore, the fact that Fas expression in often completely lost in metastatic human CRC (15) and our finding that metastatic human colon carcinoma cells use H3K9me3 to silence Fas expression suggest that metastatic human colon carcinoma cells use H3K9me3 as a mechanism to silence Fas to evade the host CTL-mediated immune surveillance to progress and metastasize. Anti-tumor immune response is often suppressed by immune suppressor cells. However, recent studies have shown that the immune suppressive Treg cells only selectively suppress the perforin pathway without inhibiting T cell activation in vivo (59, 60). Because FasL is primarily expressed on activated CTLs, the Fas-mediated effector mechanism thus should be still functional in the immune suppressive tumor microenvironment. Therefore, pharmacological means to restore Fas expression in colon carcinoma cells can be an effective approach to sensitize tumor cells to CTL FasL-mediated cytotoxicity, thereby suppressing colon cancer immune evasion to suppress metastasis even under the immune suppressive conditions.

We discovered verticillin A, a natural compound, as a selective HMTase inhibitor that is effective in restoring Fas expression in metastatic human CRC cells. Verticillin A selectively inhibits SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a and GLP enzymatic activity with an IC50 of 0.48-1.27 μM in vitro. It is known that SUV39H1, SUV39H2, G9a and GLP all catalyze H3K9 methylation (38, 39). SUV39H1 and SUV39H2 have redundant functions and mediate di- and tri-methylation of H3K9 within heterochromatin regions (38), whereas G9a and GLP form a heteromeric complex to catalyze H3K9 di-methylation (39). However, we observed that G9a also catalyzes H3K9 trimethylation to mediate FAS silencing in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells (Fig. 6). In fact, SUV39H1 SUV39H2 and G9a all catalyze H3K9 trimethylation to cooperatively silence Fas expression in the metastatic human colon carcinoma cells.

Although verticillin A is effective in suppression of metastatic human CRC cell growth at a relatively high dose (i.e. 100 nM), verticillin A might be more valuable as a sensitizer to overcome human cancer cell resistance to apoptosis, and we observed that a sublethal dose of verticillin A effectively overcame metastatic human colon carcinoma cell resistance to FasL-induced apoptosis, and this sensitization is apparently Fas-dependent (Fig. 8C & D). Epigenetic agents, such as DNMT and histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, were initially used at their maximally tolerated doses in clinical trials in human cancer patients, and were often associated with extensive toxicity and minimal efficacy (61). Recent studies have shown that both clinical efficacy and tolerance improve when lower doses of these agents are used, and current clinical development efforts for DNMT and HDAC inhibitors are primarily focused on combining these agents with cytotoxic agents (29). HMTase inhibitors are much less studied as cancer therapeutic agents. In this study, we observed that H3K9me3 may play a dominant role over DNA methylation and HDACs in conferring metastatic human CRC cells to FasL-induced apoptosis. We observed that verticillin A can effectively inhibit H3K9me3 to re-activate FAS transcription. We envision that a sublethal and thus subtoxic dose of verticillin A may be used as an adjunct agent to restore Fas expression in human CRC cells to sensitize the tumor cells to CTL FasL-mediated cytotoxicity to suppress immune escape and to increase the efficacy of CTL immunotherapy to suppress CRC progression and metastasis.

TRAIL is a cancer-selective agent and has been shown to play an important role in suppression of tumor progression (46, 47). However, human clinical trials of TRAIL or TRAIL receptor agonist mAb has failed to advance beyond phase II because of limited efficacy. This outcome is expected since resistance to apoptosis is a hallmark of human cancer (62). Recent findings that modulating the TRAIL receptor complex to enhancing signaling to overcome cancer cell TRAIL resistance to suppress cancer progression has induced new hope for TRAIL-based cancer therapy (63). Here, we observed that in addition to sensitize metastatic human colon carcinoma cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis, verticillin A increased DR5 expression to effectively overcome metastatic human colon carcinoma cells to DR5-induced apoptosis. Therefore, verticillin A has the potential to be developed as an adjunct agent in TRAIL-based cancer therapy.

On the other hand, 5-FU is the standard and most commonly used therapeutic drug for patients with advanced and metastatic CRC (24, 64). Over the last three decades, increased understanding of its mechanism of action has led to the development of strategies to improve its efficacy, primarily through combination with other therapeutic drugs (65, 66). However, despite these advances, the increase in clinical response to 5-FU has been minimal and cancer cell resistance remains a major challenge in 5-FU therapy (64). Our finding that 5-FU-resistant metastatic human CRC cells express similar levels of H3K9me3 and are sensitive to verticillin A suggest that 5-FU therapy does not alter verticillin A targets in the cancer cells. Moreover, a sublethal dose of verticillin A effectively increased 5-FU-resistant metastatic human colon carcinoma cells to 5-FU-induced apoptosis (Fig. 9A). This sensitization effect is unlikely dues to increased Fas expression (Fig. S3) and likely due to altered expression of apoptosis-regulatory genes in the apoptosis signaling pathway (35). Verticillin A exhibited minimal toxicity to the liver in tumor-bearing mice in vivo. This outcome is also not surprising since verticillin A selectively targets HMTases to inhibit H3K9 methylation, an epigenetic event that is primarily involved in carcinogenesis and cancer progression but not in normal cellular activity. Therefore, verticillin A is potentially an effective and yet low toxic epigenetic agent for targeting 5-FU resistance in human patients with metastatic CRC, and thus holds great promise for further development as an “epi-drug” in human cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Drs. Eiko Kitamura and Chang-Sheng Chang at the GRU Cancer Center Integrated Genomics Facility for the excellent technical assistance in genome-wide gene expression and ChIP-Seq analysis, and Dr. A. Kaur and Ms. T. El-Elimat at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro for assistance in the purification of verticillin A.

Grant support: National Institute of Health grants CA182518 and CA185909 (to KL), CA125066 (to N.H.O. and C.P.), and VA Merit Review Award BX001962 (to KL).

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None

References

- 1.Cai Z, Yang F, Yu L, Yu Z, Jiang L, Wang Q, Yang Y, Wang L, Cao X, Wang J. Activated T cell exosomes promote tumor invasion via Fas signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2012;188:5954–5961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koncz G, Hancz A, Chakrabandhu K, Gogolak P, Kerekes K, Rajnavolgyi E, Hueber AO. Vesicles released by activated T cells induce both Fas-mediated RIP-dependent apoptotic and Fas-independent nonapoptotic cell deaths. J Immunol. 2012;189:2815–2823. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Figueira SK, Vrazo AC, Binkowski BF, Butler BL, Tabata Y, Filipovich A, Jordan MB, Risma KA. Real-time detection of CTL function reveals distinct patterns of caspase activation mediated by Fas versus granzyme B. J Immunol. 2014;193:519–528. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghare SS, Joshi-Barve S, Moghe A, Patil M, Barker DF, Gobejishvili L, Brock GN, Cave M, McClain CJ, Barve SS. Coordinated histone H3 methylation and acetylation regulate physiologic and pathologic fas ligand gene expression in human CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:412–421. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss JM, Subleski JJ, Back T, Chen X, Watkins SK, Yagita H, Sayers TJ, Murphy WJ, Wiltrout RH. Regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment undergo Fas-dependent cell death during IL-2/alphaCD40 therapy. J Immunol. 2014;192:5821–5829. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh J, Kim SH, Ahn S, Lee CE. Suppressors of cytokine signaling promote Fas-induced apoptosis through downregulation of NF-kappaB and mitochondrial Bfl-1 in leukemic T cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:5561–5571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynes MW, Edelman BL, Kostyk AG, Edwards MG, Coldren C, Groshong SD, Cosgrove GP, Redente EF, Bamberg A, Brown KK, Reisdorph N, Keith RC, Frankel SK, Riches DW. Increased cell surface Fas expression is necessary and sufficient to sensitize lung fibroblasts to Fas ligation-induced apoptosis: implications for fibroblast accumulation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2011;187:527–537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He JS, Gong DE, Ostergaard HL. Stored Fas ligand, a mediator of rapid CTL-mediated killing, has a lower threshold for response than degranulation or newly synthesized Fas ligand. J Immunol. 2010;184:555–563. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straus SE, Jaffe ES, Puck JM, Dale JK, Elkon KB, Rosen-Wolff A, Peters AM, Sneller MC, Hallahan CW, Wang J, Fischer RE, Jackson CM, Lin AY, Baumler C, Siegert E, Marx A, Vaishnaw AK, Grodzicky T, Fleisher TA, Lenardo MJ. The development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with germline Fas mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood. 2001;98:194–200. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikolov NP, Shimizu M, Cleland S, Bailey D, Aoki J, Strom T, Schwartzberg PL, Candotti F, Siegel RM. Systemic autoimmunity and defective Fas ligand secretion in the absence of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Blood. 2010;116:740–747. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park WS, Oh RR, Kim YS, Park JY, Lee SH, Shin MS, Kim SY, Kim PJ, Lee HK, Yoo NY, Lee JY. Somatic mutations in the death domain of the Fas (Apo-1/CD95) gene in gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2001;193:162–168. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::aid-path759>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei D, Sturgis EM, Wang LE, Liu Z, Zafereo ME, Wei Q, Li G. FAS and FASLG genetic variants and risk for second primary malignancy in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1484–1491. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunter NJ, Scott K, Hills R, Grimwade D, Taylor S, Worrillow LJ, Fordham SE, Forster VJ, Jackson G, Bomken S, Jones G, Allan JM. A functional variant in the core promoter of the CD95 cell death receptor gene predicts prognosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:196–205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-349803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sung WW, Wang YC, Cheng YW, Lee MC, Yeh KT, Wang L, Wang J, Chen CY, Lee H. A polymorphic -844T/C in FasL promoter predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5991–5999. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moller P, Koretz K, Leithauser F, Bruderlein S, Henne C, Quentmeier A, Krammer PH. Expression of APO-1 (CD95), a member of the NGF/TNF receptor superfamily, in normal and neoplastic colon epithelium. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:371–377. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krammer PH. CD95(APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis: live and let die. Adv. Immunol. 1999;71:163–210. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strater J, Hinz U, Hasel C, Bhanot U, Mechtersheimer G, Lehnert T, Moller P. Impaired CD95 expression predisposes for recurrence in curatively resected colon carcinoma: clinical evidence for immunoselection and CD95L mediated control of minimal residual disease. Gut. 2005;54:661–665. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afshar-Sterle S, Zotos D, Bernard NJ, Scherger AK, Rodling L, Alsop AE, Walker J, Masson F, Belz GT, Corcoran LM, O'Reilly LA, Strasser A, Smyth MJ, Johnstone R, Tarlinton DM, Nutt SL, Kallies A. Fas ligand-mediated immune surveillance by T cells is essential for the control of spontaneous B cell lymphomas. Nat Med. 2014;20:283–290. doi: 10.1038/nm.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu F, Bardhan K, Yang D, Thangaraju M, Ganapathy V, Waller JL, Liles GB, Lee JR, Liu K. NF-kappaB Directly Regulates Fas Transcription to Modulate Fas-mediated Apoptosis and Tumor Suppression. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:25530–25540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.356279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maecker HL, Yun Z, Maecker HT, Giaccia AJ. Epigenetic changes in tumor Fas levels determine immune escape and response to therapy. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang D, Torres CM, Bardhan K, Zimmerman M, McGaha TL, Liu K. Decitabine and vorinostat cooperate to sensitize colon carcinoma cells to fas ligand-induced apoptosis in vitro and tumor suppression in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;188:4441–4449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borralho PM, Moreira da Silva IB, Aranha MM, Albuquerque C, Nobre Leitao C, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Inhibition of Fas expression by RNAi modulates 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells expressing wild-type p53. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tillman DM, Petak I, Houghton JA. A Fas-dependent component in 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin-induced cytotoxicity in colon carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longley DB, Harkin DP, Johnston PG. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:330–338. doi: 10.1038/nrc1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:343–357. doi: 10.1038/nrg3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spannhoff A, Hauser AT, Heinke R, Sippl W, Jung M. The emerging therapeutic potential of histone methyltransferase and demethylase inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1568–1582. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crea F, Nobili S, Paolicchi E, Perrone G, Napoli C, Landini I, Danesi R, Mini E. Epigenetics and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer: an opportunity for treatment tailoring and novel therapeutic strategies. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:280–296. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nebbioso A, Carafa V, Benedetti R, Altucci L. Trials with 'epigenetic' drugs: an update. Mol Oncol. 2012;6:657–682. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juergens RA, Wrangle J, Vendetti FP, Murphy SC, Zhao M, Coleman B, Sebree R, Rodgers K, Hooker CM, Franco N, Lee B, Tsai S, Delgado IE, Rudek MA, Belinsky SA, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Brock MV, Rudin CM. Combination epigenetic therapy has efficacy in patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:598–607. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramaniam D, Thombre R, Dhar A, Anant S. DNA Methyltransferases: A Novel Target for Prevention and Therapy. Front Oncol. 2014;4:80. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vedadi M, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Liu F, Rival-Gervier S, Allali-Hassani A, Labrie V, Wigle TJ, Dimaggio PA, Wasney GA, Siarheyeva A, Dong A, Tempel W, Wang SC, Chen X, Chau I, Mangano TJ, Huang XP, Simpson CD, Pattenden SG, Norris JL, Kireev DB, Tripathy A, Edwards A, Roth BL, Janzen WP, Garcia BA, Petronis A, Ellis J, Brown PJ, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Jin J. A chemical probe selectively inhibits G9a and GLP methyltransferase activity in cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:566–574. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, Majer CR, Sneeringer CJ, Song J, Johnston LD, Scott MP, Smith JJ, Xiao Y, Jin L, Kuntz KW, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Bernt KM, Tseng JC, Kung AL, Armstrong SA, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Pollock RM. Selective killing of mixed lineage leukemia cells by a potent small-molecule DOT1L inhibitor. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson AD, Larsen NA, Howard T, Pollard H, Green I, Grande C, Cheung T, Garcia-Arenas R, Cowen S, Wu J, Godin R, Chen H, Keen N. Structural basis of substrate methylation and inhibition of SMYD2. Structure. 2011;19:1262–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Figueroa M, Graf TN, Ayers S, Adcock AF, Kroll DJ, Yang J, Swanson SM, Munoz-Acuna U, Carcache de Blanco EJ, Agrawal R, Wani MC, Darveaux BA, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH. Cytotoxic epipolythiodioxopiperazine alkaloids from filamentous fungi of the Bionectriaceae. J Antibiot. 2012;65:559–564. doi: 10.1038/ja.2012.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu F, Liu Q, Yang D, Bollag WB, Robertson K, Wu P, Liu K. Verticillin A Overcomes Apoptosis Resistance in Human Colon Carcinoma through DNA Methylation-Dependent Upregulation of BNIP3. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6807–6816. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bacon AL, Fox S, Turley H, Harris AL. Selective silencing of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 target gene BNIP3 by histone deacetylation and methylation in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:132–141. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Carroll D, Scherthan H, Peters AH, Opravil S, Haynes AR, Laible G, Rea S, Schmid M, Lebersorger A, Jerratsch M, Sattler L, Mattei MG, Denny P, Brown SD, Schweizer D, Jenuwein T. Isolation and characterization of Suv39h2, a second histone H3 methyltransferase gene that displays testis-specific expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9423–9433. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.24.9423-9433.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rice JC, Briggs SD, Ueberheide B, Barber CM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Shinkai Y, Allis CD. Histone methyltransferases direct different degrees of methylation to define distinct chromatin domains. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1591–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hewitt RE, McMarlin A, Kleiner D, Wersto R, Martin P, Tsokos M, Stamp GW, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Tsoskas M. Validation of a model of colon cancer progression. J Pathol. 2000;192:446–454. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH775>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin Q, Yu LR, Wang L, Zhang Z, Kasper LH, Lee JE, Wang C, Brindle PK, Dent SY, Ge K. Distinct roles of GCN5/PCAF-mediated H3K9ac and CBP/p300-mediated H3K18/27ac in nuclear receptor transactivation. EMBO J. 2011;30:249–262. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LA O, Tai L, Lee L, Kruse EA, Grabow S, Fairlie WD, Haynes NM, Tarlinton DM, Zhang JG, Belz GT, Smyth MJ, Bouillet P, Robb L, Strasser A. Membrane-bound Fas ligand only is essential for Fas-induced apoptosis. Nature. 2009;461:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nature08402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashkenazi A. Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with pro-apoptotic receptor agonists. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:1001–1012. doi: 10.1038/nrd2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almasan A, Ashkenazi A. Apo2L/TRAIL: apoptosis signaling, biology, and potential for cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:337–348. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ashkenazi A. Targeting death and decoy receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor superfamily. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:420–430. doi: 10.1038/nrc821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosse-Wilde A, Voloshanenko O, Bailey SL, Longton GM, Schaefer U, Csernok AI, Schutz G, Greiner EF, Kemp CJ, Walczak H. TRAIL-R deficiency in mice enhances lymph node metastasis without affecting primary tumor development. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:100–110. doi: 10.1172/JCI33061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocha Lima CM, Bayraktar S, Flores AM, Macintyre J, Montero A, Baranda JC, Wallmark J, Portera C, Raja R, Stern H, Royer-Joo S, Amler LC. Phase Ib Study of Drozitumab Combined With First-Line mFOLFOX6 Plus Bevacizumab in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Invest. 2012 doi: 10.3109/07357907.2012.732163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson NS, Yang B, Yang A, Loeser S, Marsters S, Lawrence D, Li Y, Pitti R, Totpal K, Yee S, Ross S, Vernes JM, Lu Y, Adams C, Offringa R, Kelley B, Hymowitz S, Daniel D, Meng G, Ashkenazi A. An Fcgamma receptor-dependent mechanism drives antibody-mediated target-receptor signaling in cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yokoyama Y, Hieda M, Nishioka Y, Matsumoto A, Higashi S, Kimura H, Yamamoto H, Mori M, Matsuura S, Matsuura N. Cancer-associated upregulation of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation promotes cell motility in vitro and drives tumor formation in vivo. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:889–895. doi: 10.1111/cas.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ceol CJ, Houvras Y, Jane-Valbuena J, Bilodeau S, Orlando DA, Battisti V, Fritsch L, Lin WM, Hollmann TJ, Ferre F, Bourque C, Burke CJ, Turner L, Uong A, Johnson LA, Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Loda M, Ait-Si-Ali S, Garraway LA, Young RA, Zon LI. The histone methyltransferase SETDB1 is recurrently amplified in melanoma and accelerates its onset. Nature. 2011;471:513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature09806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marteau JB, Rigaud O, Brugat T, Gault N, Vallat L, Kruhoffer M, Orntoft TF, Nguyen-Khac F, Chevillard S, Merle-Beral H, Delic J. Concomitant heterochromatinisation and down-regulation of gene expression unveils epigenetic silencing of RELB in an aggressive subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in males. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:53. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park YS, Jin MY, Kim YJ, Yook JH, Kim BS, Jang SJ. The global histone modification pattern correlates with cancer recurrence and overall survival in gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1968–1976. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin B, Li Y, Robertson KD. DNA methylation: superior or subordinate in the epigenetic hierarchy? Genes Cancer. 2011;2:607–617. doi: 10.1177/1947601910393957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petak I, Danam RP, Tillman DM, Vernes R, Howell SR, Berczi L, Kopper L, Brent TP, Houghton JA. Hypermethylation of the gene promoter and enhancer region can regulate Fas expression and sensitivity in colon carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:211–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morachis JM, Murawsky CM, Emerson BM. Regulation of the p53 transcriptional response by structurally diverse core promoters. Genes Dev. 2010;24:135–147. doi: 10.1101/gad.1856710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Galon J. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen ML, Pittet MJ, Gorelik L, Flavell RA, Weissleder R, von Boehmer H, Khazaie K. Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-beta signals in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mempel TR, Pittet MJ, Khazaie K, Weninger W, Weissleder R, von Boehmer H, von Andrian UH. Regulatory T cells reversibly suppress cytotoxic T cell function independent of effector differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glover AB, Leyland-Jones BR, Chun HG, Davies B, Hoth DF. Azacitidine: 10 years later. Cancer Treat Rep. 1987;71:737–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graves JD, Kordich JJ, Huang TH, Piasecki J, Bush TL, Sullivan T, Foltz IN, Chang W, Douangpanya H, Dang T, O'Neill JW, Mallari R, Zhao X, Branstetter DG, Rossi JM, Long AM, Huang X, Holland PM. Apo2L/TRAIL and the death receptor 5 agonist antibody AMG 655 cooperate to promote receptor clustering and antitumor activity. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:714–726. doi: 10.1038/nrc3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]