Abstract

Chronic stress can lead to the development of anxiety and mood disorders. Thus, novel therapies for preventing adverse effects of stress are vitally important. Recently, the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B was identified as a novel regulator of stress-induced anxiety. This opens up exciting opportunities to exploit PTP1B inhibitors as anxiolytics.

Keywords: Endocannabinoid signaling, Stress-induced anxiety, Protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B, Anxiolytic therapy, Trodusquemine/MSI-1436, Glutamate receptor

Signal transduction pathways controlled by reversible tyrosine phosphorylation have been implicated in the regulation of a variety of synaptic and cellular functions in neurons, with both protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) and phosphatases (PTPs) playing crucial roles under normal and pathophysiological conditions [1]. The ability to modulate such signal transduction pathways selectively holds enormous therapeutic potential. To date, much of the drug development focus has been on protein kinases and the first drugs directed against PTKs have now entered the market, representing breakthroughs in cancer therapy [1]. Nevertheless, these approaches have their limitations and novel therapeutic targets and strategies are required to complement kinase-directed drug development. Despite the importance of the phosphatases in the control of reversible phosphorylation-dependent signal transduction, these enzymes remain underexploited as therapeutic targets [1]. The protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B plays a well-established role in down-regulating signaling in response to insulin and leptin and is a highly validated therapeutic target for diabetes and obesity [1]. Furthermore, PTP1B also plays a positive role in promoting signaling events associated with breast tumorigenesis and is a therapeutic target for HER2-positive cancer [1]. Now a recent study has extended the scope of PTP1B-directed therapeutics to include anxiety disorders, highlighting the potential for PTP1B inhibitors to be exploited as anxiolytics [2].

In this study, the authors investigated signaling changes in the amygdala, focusing on endocannabinoid (eCB) signaling as a regulator of anxiety. They noted that facilitation of eCB signaling reverses anxiety induced by chronic stress, whereas disruption of eCB signaling promotes states of anxiety. Considering that production of eCB is regulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors, in particular mGluR5, which may be subject to regulation by reversible tyrosine phosphorylation, they proposed that a decrease in mGluR5 tyrosine phosphorylation could impair eCB production and signaling. In a previous study, the authors reported that the LIM domain only protein LMO4 functioned as an inhibitor of PTP1B, which exerted its effects by increasing the oxidation and inactivation of the phosphatase [3]. Now, they noted a profound anxiety phenotype in mice that were deficient in LMO4 expression in glutaminergic neurons. This led them to propose that in response to chronic stress, mediated by glucocorticoids, LMO4-mediated inhibition of PTP1B was impaired, which in turn led to a PTP1B-catalyzed decrease in tyrosine phosphorylation of mGluR5 and the collapse of eCB production, resulting in increased anxiety. Although this is an attractive model, not least because of the potential therapeutic implications of inhibiting PTP1B as a strategy for treatment of anxiety disorders, closer scrutiny of the data reveals that several aspects of the study require further validation.

LMO4 as a regulator of PTP1B

Central to the model is the regulation of PTP1B by LMO4, a Zn finger motif protein that has been implicated in protein-protein interactions. PTP1B-null mice are healthy, display enhanced insulin sensitivity, do not develop type 2 diabetes and are resistant to obesity when fed with a high fat diet. This is associated with the ability of PTP1B to dephosphorylate the insulin receptor β-subunit and the leptin receptor-associated JAK2 tyrosine kinase, thereby to down-regulate insulin and leptin signaling [1]. The authors noted that ablation of LMO4 in neurons resulted in an obesity phenotype, associated with impaired leptin-induced phosphorylation of STAT3, together with insulin resistance, impaired glucose homeostasis and attenuated central leptin signaling. They interpreted this phenotype as resulting from the relief of an LMO4-mediated inhibitory constraint on PTP1B [3].

The mechanism they propose involves manipulating redox regulation of PTP1B function. It is now established that the controlled production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), in particular hydrogen peroxide, represents a mechanism for fine-tuning tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent signaling in response to a variety of stimuli. Members of the PTP family are characterized by a signature motif, HC(X)5R(S/T), in which the catalytically essential, invariant cysteine is exquisitely sensitive to reversible oxidation and inactivation. Consequently, stimulus-induced production of H2O2, such as in response to insulin or leptin, leads to the transient oxidation and inactivation of those PTPs, such as PTP1B, that normally inhibit the signaling pathway. This transient PTP inactivation enhances the tyrosine phosphorylation of substrates that are components of the stimulus-induced pathway, which promotes the signaling response. Oxidation of the active site Cys in PTPs can produce either sulphenic (S-OH), sulphinic (S-O2H) or sulphonic (S-O3H) acid. For oxidation to represent a mechanism for reversible regulation of PTP function, it is important that the active site Cys is not oxidized further than sulphenic acid, since higher oxidation is usually an irreversible modification. Several methods have been developed to demonstrate and assay reversible oxidation of PTPs in cells [4]. The method chosen by the authors utilizes an antibody generated against a consensus peptide from the active site of members of the PTP family, VHCSAG, in which the Cys is in the terminally oxidized, sulphonic acid form [5]. Although there are ways to adapt this antibody to measure reversible PTP oxidation [4], the authors do not appear to have done so and have instead used it directly in immunoblotting. Consequently, they are measuring the appearance of the irreversibly oxidized form of PTP1B, which is unlikely to be the form of the protein that is important for reversible regulation of phosphatase activity. In addition, they demonstrate that tagged versions of PTP1B and LMO4 associate following overexpression in F11 neuroblastoma cells, but there is no indication of the stoichiometry of the association, and no indication of the extent to which it occurs under physiological conditions. There is also a suggestion that LMO4 is tyrosine phosphorylated and may itself be a substrate of PTP1B, but again the extent to which this occurs and its significance under physiological conditions is unclear. Finally, in assessing the effects of LMO4 on the activity of PTP1B, the authors use a “PhosphoSeek PTP1B Assay Kit” from BioVision. This kit is designed as an assay for screening activity of the purified protein in vitro and does not contain any step for enriching PTP1B from cell lysates. Consequently, the activity that is being measured in this study will be that of any PTP in the cell lysate that recognizes the fluorescent dye substrate, which is likely to reflect several PTPs and not just PTP1B alone. Therefore, although there are attractive features to this element of the model, a more quantitative approach to define precisely the stoichiometries of association and to investigate further the significance of reversible oxidation of PTP1B for the effects of LMO4 will be required to test its validity.

The importance of tyrosine phosphorylation for regulation of mGluR5 function

Another central feature of the model is the regulation of mGluR5 by reversible tyrosine phosphorylation; however, the regulatory importance of such phosphorylation remains to be defined. Glutamate receptors, such as mGluR5, are G protein-coupled receptors that are linked to activation of phospholipase C and phosphatidylinositol phospholipid turnover, with the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and the modulation of multiple downstream signaling pathways, in particular those involved in protein translation [6]. Studies of mGluR5 tyrosine phosphorylation have focused on testing the effects of broad specificity kinase and phosphatase inhibitors [7]. It has been reported that mGluR5 is tyrosine phosphorylated, but only after treatment with the broad specificity PTP inhibitor pervanadate [7]. Furthermore, this phosphorylation was not associated with any changes in phosphatidylinositol phospholipid turnover, so the significance with respect to regulation of signaling remains unclear [8]. In this study, the authors demonstrate tyrosine phosphorylation of mGluR5, but further work is needed to define the stoichiometry of phosphorylation, to identify the sites that are phosphorylated, to identify the PTK responsible for the phosphorylation and to validate that this modification is linked to a change in signaling. It will be of interest also to examine where in the cell such phosphorylation may occur. It has been reported that different subcellular pools of mGluR5 may be associated with different signaling outcomes [8]. Considering the ER localization of PTP1B [1] and recent reports that there are intracellular pools of mGluR5, including in the ER, it will be interesting to test whether PTP1B exerts effects on receptors at the cell surface or on intracellular membranes.

Stress, endocannabinoid signaling and anxiety

The authors noted that the phenotype of the LMO4-knockout mouse resembles that seen following chronic stress or loss of eCB signaling. Therefore, they took the complementary approach of testing the effects of chronic stress stimuli on the proposed signaling cascade and the development of anxiety. They subjected mice to a daily regimen of restraint stress over a period of eight days, which resulted in increased levels of the stress hormone corticosterone in the blood. The authors report that these effects coincided with elevated PTP1B activity in the amygdala, and in neuronal cells exposed to corticosterone in culture, due to a decrease in the amount of the oxidized inactive form of the phosphatase, which coincided with attenuation of stress-induced decrease in eCBs. Furthermore, they report that treatment with the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU486 during chronic stress normalized PTP1B activity in the amygdala. Nevertheless, one caveat of these studies with respect to the proposal that the effects of LMO4 on PTP1B activity was mediated through changes in redox regulation of the phosphatase is that chronic stress, such as the restraint stress regimen used here, has been reported to lead also to enhanced oxidative stress. In fact, such acute restraint stress has been reported to induce expression of NADPH oxidases, which are major enzymes that promote PTP oxidation and inactivation in cells [9]. Considering the susceptibility to oxidation and inactivation of the catalytic cysteine residue at the PTP active site, one might have anticipated that restraint stress would lead to enhanced oxidation and inactivation of those PTPs that colocalize with the NADPH oxidases. In addition, it remains unclear from the protocol used in this study, which PTPs are being measured in the activity assay and the extent to which PTP1B contributes to the activity that was detected. Further studies will be required to define more precisely the mechanism by which PTP1B activity may be regulated in this context.

Trodusquemine/MSI-1436 – an allosteric inhibitor of PTP1B and drug candidate

Although it has been possible to generate potent, specific and reversible small molecule inhibitors of PTP1B, the chemical properties of the PTP active site dictated that these inhibitors were highly charged and limited in their drug development potential. The aminosterol natural product Trodusquemine represents a new class of allosteric inhibitors of PTP1B, which bind at a site remote from the catalytic center, in the regulatory C-terminal segment of the protein, but induce conformational changes in the enzyme that result in inhibition [10]. Treatment of high fat diet-induced obese mice with Trodusquemine has been reported to result in fat-specific weight loss, as expected for inhibition of PTP1B [10]. Furthermore, consistent with the positive role for PTP1B in regulating signaling by the HER2 oncoprotein tyrosine kinase, Trodusquemine has been shown to attenuate HER2-induced tumorigenesis and metastasis in animal models of breast cancer [10]. Now in this study, the authors have used Trodusquemine to support a central role for PTP1B in regulating stress-induced anxiety. They showed that treatment of F11 neuroblastoma cells with Trodusquemine led to enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of mGluR5. Furthermore, injection of the inhibitor into the amygdala, as well as systemic administration by intra-peritoneal injection attenuated the anxiety phenotype in the LMO4-knockout mice. Similar results were obtained following injection of lentiviral vectors expressing specific shRNA against PTP1B. Furthermore, they demonstrated that treatment with Trodusquemine attenuated the decrease in levels of eCBs in the amygdala of restraint stress-treated mice and decreased stress-induced anxiety. These are perhaps the strongest data to support a critical role for PTP1B in this pathway.

Summary and perspectives

The mechanisms underlying stress-induced anxiety remain to be fully defined. Overall, this study makes an important contribution not only in highlighting a potential signaling pathway in the amygdala that induces anxiety by impaired eCB signaling, but also in identifying the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B as a novel therapeutic target for anxiolytic therapy from within that pathway. Nevertheless, an element of caution is raised by an independent study from the Heberlein lab [11], which shows that ablation of LMO4 in the amygdala “did not significantly affect anxiety-like behavior” – a diametrically opposed conclusion to that drawn from this study. It is interesting to note that LMO4 is frequently overexpressed in human breast tumors [12]; it induces hyperplasia and promotes cell migration when overexpressed in the mouse mammary gland. Furthermore, it has been shown to be overexpressed in more than 60% of HER2-positive tumors, where it is required for HER2-induced cancer cell cycle progression through the regulation of Cyclin D expression [13]. In addition, by functioning as an adapter protein it has been implicated in promoting cell migration through the regulation of Ste20-like Kinase (SLK) [12]. Interestingly PTP1B is also a positive regulator of HER2-dependent tumorigenesis [10]. As an endogenous inhibitor of PTP1B, LMO4 would be expected to counteract the activity of the phosphatase and inhibit HER2-dependent breast cancer progression; however, in contrast, the two proteins have been reported to promote tumorigenesis. This suggests that there are facets to this interaction that we don’t yet understand, with further studies required to define the relationship more fully.

The amygdala has been shown to be active in insulin signaling [14, 15]. In response to a high fat diet, rodents develop insulin resistance in the amydgala, consistent with a role for this region of the brain in metabolic regulation. Furthermore, neuroimaging studies from obese and normal human subjects have revealed that obese individuals display increased activation in the amygdala compared to the normal subjects, suggesting a potential link between chronic stress and metabolic aberrations. As PTP1B is a negative regulator of insulin signaling, it will be interesting to test whether enhanced insulin signaling following administration of an inhibitor of the phosphatase may contribute to ameliorating symptoms associated with anxiety.

PTP1B has already been validated as a therapeutic target in diabetes and obesity, as well as HER2-positive breast cancer. In light of this, there have been major programs in industry focused on developing small molecule inhibitors of PTP1B, but such efforts have been frustrated by the chemical properties of the PTP active site. The identification of Trodusquemine has opened up a new approach to PTP1B-directed drug development [10] and provided an important tool to validate a role for PTP1B in stress-induced anxiety. Hopefully, the establishment of further links to major unmet medical needs, such as in this study, will help to reinvigorate interest in PTP1B, and the PTP family of enzymes in general, as therapeutic targets.

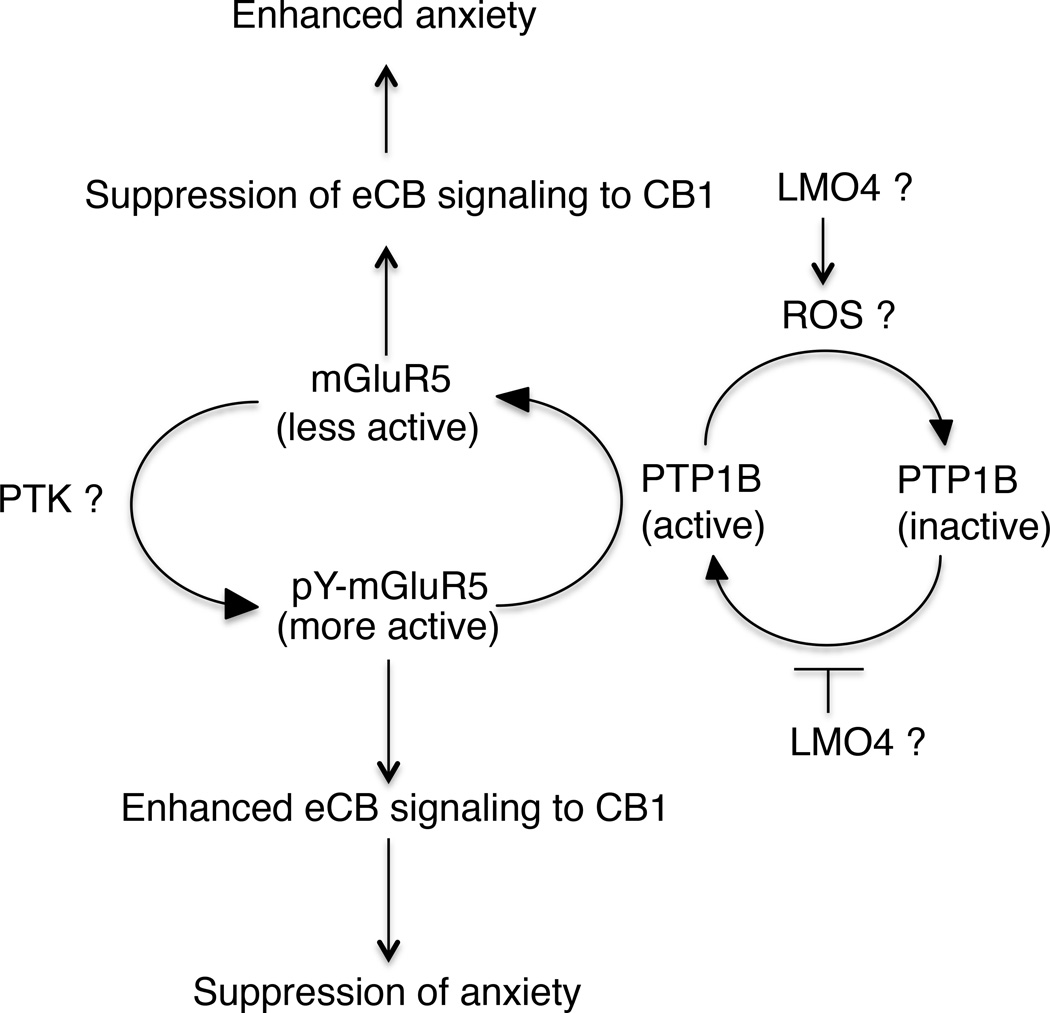

Figure 1. A model to summarize the proposed role of PTP1B in regulation of endocannabinoid signaling.

A number of aspects of the model require further validation. This includes the role of LMO4 in the regulation of PTP1B. What is the specific neuronal subtype and region of the brain in which PTP1B and LMO4 are localized? Trodusquemine has a direct impact on PTP1B that is independent of oxidation, yet it effectively suppresses anxiety. To what extent does reversible oxidation of PTP1B contribute to this pathway? What is the source of ROS for PTP1B oxidation and how is it triggered? Is there a role for mGluR5 in ROS production and where in the cell does the regulation occur? Does LMO4 inhibit PTP1B activity at the level of promoting oxidation and inactivation, or impairing reduction and reactivation? Another important feature is the regulation of mGluR5 activity by reversible tyrosine phosphorylation. What is the kinase that phosphorylates mGluR5 and how is its activity coordinated with this signaling pathway? To what extent does tyrosine phosphorylation alter signaling output from mGluR5? What are the critical sites for regulation of mGluR5 function?

HIGHLIGHTS.

Role for PTP1B in endocannabinoid signaling

Novel therapeutic strategy for anxiety disorders

PTP1B as anxiolytics

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in the authors’ lab is supported by by NIH grants CA53840 and GM55989, and the CSHL Cancer Centre Support Grant CA45508. We are grateful to our colleague Linda Van Aelst for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases--from housekeeping enzymes to master regulators of signal transduction. The FEBS journal. 2013;280:346–378. doi: 10.1111/febs.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin Z, et al. Chronic stress induces anxiety via an amygdalar intracellular cascade that impairs endocannabinoid signaling. Neuron. 2015;85:1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey NR, et al. The LIM domain only 4 protein is a metabolic responsive inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B that controls hypothalamic leptin signaling. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:12647–12655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0746-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karisch R, et al. Global proteomic assessment of the classical protein-tyrosine phosphatome and "Redoxome". Cell. 2011;146:826–840. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persson C, et al. Preferential oxidation of the second phosphatase domain of receptor-like PTP-alpha revealed by an antibody against oxidized protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:1886–1891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304403101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waung MW, Huber KM. Protein translation in synaptic plasticity: mGluR-LTD, Fragile X. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2009;19:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orlando LR, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 in striatal neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tozzi A, et al. Group I mGluRs coupled to G proteins are regulated by tyrosine kinase in dopamine neurons of the rat midbrain. Journal of neurophysiology. 2001;85:2490–2497. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo JS, et al. NADPH oxidase mediates depressive behavior induced by chronic stress in mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:9690–9699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0794-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan N, et al. Targeting the disordered C terminus of PTP1B with an allosteric inhibitor. Nature chemical biology. 2014;10:558–566. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiya R, et al. Lmo4 in the basolateral complex of the amygdala modulates fear learning. PloS one. 2012;7:e34559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baron KD, et al. Recruitment and activation of SLK at the leading edge of migrating cells requires Src family kinase activity and the LIM-only protein 4. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1853:1683–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montanez-Wiscovich ME, et al. LMO4 is an essential mediator of ErbB2/HER2/Neu-induced breast cancer cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 2009;28:3608–3618. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Areias MF, Prada PO. Mechanisms of insulin resistance in the amygdala: influences on food intake. Behavioural brain research. 2015;282:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh H, et al. The effect of high fat diet and saturated fatty acids on insulin signaling in the amygdala and hypothalamus of rats. Brain research. 2013;1537:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]