Abstract

To metastasize, tumor cells often need to migrate through a layer of collagen-containing scar tissue which encapsulates the tumor. A key component of scar tissue and fibrosing diseases is the monocyte-derived fibrocyte, a collagen-secreting pro-fibrotic cell. To test the hypothesis that invasive tumor cells may block the formation of the fibrous sheath, we determined if tumor cells secrete factors that inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. We found that the human metastatic breast cancer cell line MDA-MB 231 secretes activity that inhibits human monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, while less aggressive breast cancer cell lines secrete less of this activity. Purification indicated that Galectin-3 Binding Protein (LGALS3BP) is the active factor. Recombinant LGALS3BP inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, and immunodepletion of LGALS3BP from MDA-MB 231 conditioned media removes the monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation-inhibiting activity. LGALS3BP inhibits the differentiation of monocyte-derived fibrocytes from wild-type mouse spleen cells, but not from SIGN-R1−/− mouse spleen cells, suggesting that CD209/SIGN-R1 is required for the LGALS3BP effect. Galectin-3 and galectin-1, binding partners of LGALS3BP, potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. In breast cancer biopsies, increased levels of tumor cell-associated LGALS3BP were observed in regions of the tumor that were invading the surrounding stroma. These findings suggest LGALS3BP and galectin-3 as new targets to treat metastatic cancer and fibrosing diseases.

Keywords: Cancer, Metastasis, Fibrosis, Monocyte/Macrophage, Cell Differentiation, Fibrocyte, Inflammation

Introduction

A key component of scar tissue is the fibrocyte, a CD34+, CD45+, collagen+ cell found in healing wounds and fibrotic lesions. Monocytes are recruited to wounds or fibrotic lesions by chemokines (1, 2), and in response to wound signals such as tryptase released from mast cells, or thrombin activated during blood clotting, differentiate into monocyte-derived fibrocytes (3–5). The term “fibrocyte” has been used to refer to multiple cell types, including cells of the ear (6), CD34+, CD45+, collagen+ circulating cells (4, 7), and spindle-shaped CD34+, CD45+, collagen+ cells that differentiate in a tissue or in cell culture (4, 8). Spindle-shaped CD34+, CD45+, collagen+ fibrocytes are found in scar tissue (9, 10), and it appears likely that circulating CD34+, CD45+, collagen+ PBMC are either precursors to the fibrocytes in scar tissue (11, 12), or are fibrocytes that have left the scar tissue.

While circulating fibrocytes can be directly purified (12–14), in this study we cultured PBMC or monocytes to obtain monocyte-derived fibrocytes (15). Monocytes isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells differentiate in vitro in a defined media into monocyte-derived fibrocytes (16). Monocyte-derived fibrocytes express collagen and other extracellular matrix proteins, secrete pro-angiogenic factors, and activate nearby fibroblasts to proliferate and secrete collagen (3, 17–20). Increased monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation correlates with increased fibrosis in animal models (21, 22). Elevated circulating fibrocyte counts also associate with poor prognosis in human diseases (23).

In response to a foreign object or inflammatory environment, the immune system can initiate a desmoplastic response in which monocytes differentiate into monocyte-derived fibrocytes to form a sheath of fibrotic tissue around the foreign object (24–27). In response to some tumors, the immune system also initiates a desmoplastic response, attempting to contain the tumor (9, 28). This desmoplastic sheath is a dynamic, responsive tissue that adjusts to changing conditions in the tumor microenvironment (29, 30).

To metastasize through this desmoplastic tissue, cancer cells must find a way to remove scar tissue or to prevent scar tissue from forming (29–34). As cancer progresses towards metastasis and a more mesenchymal phenotype, it interacts with the immune system in different ways. Some tumors attempt to evade the immune system, and others act to suppress the immune system (35–39).

The MDA-MB-231 cell line was isolated from metastases of a breast cancer patient (40). MDA-MB-231 cells behave aggressively in culture and murine models, displaying a metastatic phenotype that suggests that these cells retain the protein expression profile which allowed them to metastasize through the basement membrane of the original patient (41).

Galectin-3 binding protein (LGALS3BP), previously called Mac-2 binding protein and tumor-associated antigen 90K, is a heavily glycosylated 90 kDa protein (42). LGALS3BP binds to galectins 1, 3, and 7, fibronectin, and collagen IV, V, and VI (42–44). LGALS3BP is a member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich domain (SRCR) family of proteins (45). LGALS3BP is ubiquitously expressed in bodily secretions, including milk, tears, semen, and serum, usually 10 µg/ml (46). In patients with aggressive hormone-regulated cancers, including breast cancer, serum LGALS3BP concentration can be an order of magnitude higher than in normal serum (47–49). In breast milk, LGALS3BP concentration can rise and fall over the same range (approximately 10 µg/ml to 100 µg/ml) depending on the length of time after the pregnancy (46). LGALS3BP is produced mostly by epithelial cells in glands (breast and tear ducts) and cancer cells (especially breast cancer cells) (50).

Higher levels of serum LGALS3BP correlate with worse outcomes in breast cancer patients (48, 49, 51, 52), while higher levels of LGALS3BP’s binding partner galectin-3 correlate with better outcomes for breast cancer patients (53). LGALS3BP promotes angiogenesis by increasing VEGF signaling and directly signaling endothelial cells (43, 54). Mouse knockouts of LGALS3BP show higher circulating levels of TNF-alpha, IL-12, and interferon-gamma, suggesting a role of LGALS3BP in regulating the immune system (55).

Galectin-3 is a ~30 kDa protein expressed nearly ubiquitously in human tissues, and can be secreted from cells, associated with membrane bound carbohydrates, or located in the cytoplasm (53, 56–59). Galectin-3 is a biomarker of fibrosing diseases such as heart disease and pulmonary fibrosis (60, 61). As the disease severity increases, serum galectin-3 concentrations increase. Galectin-3 is widely expressed by immune system cells, and promotes the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages (62). Galectin-3 interacts with a number of intercellular and intracellular receptors and ligands, and is theorized to have roles in inflammation, host response to a virus, and wound healing (57, 62, 63).

In this report, we show that MDA-MB 231 cells secrete LGALS3BP, which in turn inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, and that conversely galectin-3 promotes monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. LGALS3BP and galectin-3 are new modulators of fibrosis in the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, the effects of LGALS3BP and galectin-3 on monocyte-derived fibrocytes show these proteins are active signaling molecules in cancer and fibrosis, respectively, and not passive biomarkers.

Materials and methods

PBMC isolation and culture

Human blood was collected from adult volunteers who gave written consent and with specific approval from the Texas A&M University human subjects Institutional Review Board. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated and cultured as previously described (64, 65). Protein-free medium (PFM) was Fibrolife basal medium (Lifeline, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1× non-essential amino acids (Sigma), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 2 mM glutamine (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Lonza). Serum-free media (SFM) was PFM further supplemented with 10 µg/ml recombinant human insulin (Sigma), 5 µg/ml recombinant human transferrin (Sigma), and 550 µg/ml filter-sterilized human albumin (65). PBMC were cultured in SFM with the indicated concentrations of conditioned media, recombinant human galectin-1 and galectin-3 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), or recombinant human galectin-3 binding protein (R & D systems, Minneapolis, MN) for five days, after which PBMC were stained, and monocyte-derived fibrocytes were identified by morphology as 40–100 µm long, spindle-shaped cells tapered at both ends with oval nuclei (65). The same phenotypic criteria was used to identify the 25–60 µm long mouse monocyte-derived fibrocytes. Adhered cells and macrophages were counted as previously described (65). Human monocytes were purified, tested for purity, and cultured as previously described (8, 65). For immunohistochemistry, PBMC were fixed and stained for CD209 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) as previously described (8).

Tumor cell lines and conditioned media

MDA-MB 231 (40), MDA-MB 435 (66), and DCIS.com (67) cells were the kind gift of Dr. Weston Porter. HT-29 (68), SW480 (69), DKOB8 (70), and HCT (71) cells were the kind gift of Dr. Robert Chapkin. MCF-7 (72), ADR-RES (73), OVCAR-8 (74, 75), SNU 398 (76), HEP-G2 (77), SW 1088 (78), U87 MG (79), and PANC-1 (80) cells were the kind gift of Dr. Deann Wallis. Mono mac-1 (81) and Mono mac-6 (82) were from the DSMZ (Liebniz Institute: German Collection of Microogranisms and Cell Culture, Braunschwieg, Germany), and U-937 (83), HL-60 (84), THP-1 (85), and HEK-293 (86) cells were from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). The MDA-MB 435 cell line has previously been classed as a breast cancer cell line, but is currently classed as a melanoma cell line (66, 87). Each tumor cell line was tested for mycoplasma contamination using a PCR detection kit (MDBioproducts, St. Paul, MN) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and all work was done with cell lines containing undetectable levels of mycoplasma.

Tumor cell lines were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Genesee Scientific, San Diego, CA) in 75 cm2 flasks (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) until 70% confluent. Adhered cells were washed three times with PBS, and were then incubated with 10 ml protein free media (PFM). After 24 or 48 hours, the conditioned medium was collected and clarified by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 minutes. Conditioned media from MDA-MB 231 cells was further clarified by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes, followed by clarification at 200,000 × g for 1 hour. The supernatant was then concentrated with a 100 kDa centrifugal filter (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MD), and buffer exchanged with 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2. Proteins were visualized by silver stain on 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California) and protein concentration was assessed by absorbance at 280 nm (Synergy MX, Biotek, Winooski, VT).

Protein purification and identification

300 ml of MDA-MB 231 CM was clarified by ultracentrifugation, concentrated, and buffer-exchanged as described above, and resuspended in 1 ml. This was loaded on a 5 ml MonoQ anion exchange column on an AKTA chromatography system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The column was washed with 6 ml of 20 mM NaPO4 pH 7.4 buffer (first 6 fractions), and bound proteins were then eluted with a 24 ml gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in 20 mM NaPO4 pH 7.4, collecting 0.5 ml fractions. Serial doubling dilutions of fractions were then mixed with PBMC, and their effect on monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation was measured as previously described (15). Trypsin digestion of samples, purification of peptides with Zip tips (EMD Millipore), and mass spectrometry was performed by the University of Utah mass spectrometry core facility, and peptides with MASCOT scores > 40 and mass errors < 3 ppm were used for protein identification.

Flow cytometry

PBMC were placed on an ultra low attachment plate (Corning, Corning, NY) and incubated with MDA-MB 231 conditioned media at the indicated concentrations for the indicated time. These cells were then removed from the plate using ice cold 5 mM EDTA in PBS (Rockland, Limerick, PA) with gentle pipetting. PBMC were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g for 10 minutes, resuspended in 100 µl ice cold PBS, and analyzed for viability using propidium iodide (Sigma) and forward/side scatter via flow cytometry (Accuri-BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as previously described (88, 89).

Immunodepletion of conditioned media

For immunodepletion, rabbit polyclonal anti-galectin-3 binding protein (BIOSS, Woburn, MA), mouse monoclonal anti-galectin-3 (Biolegend), mouse IgG isotype control (Jackson, West Grove, PA) and rabbit polyclonal anti-protein S (Sigma) antibodies were bound to protein G-coated Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) beads following the manufacturer’s instructions. Beads complexed with antibodies were mixed 1:10 with conditioned media at 37° C for 2 hours. Beads were then removed from the conditioned media following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sequencing MDA-MB 231 LGALS3BP

Total RNA was isolated from MDA-MB 231 cells using a kit (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA), and cDNA was generated using a kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). LGALS3BP was amplified using Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) with primers 5’-AACTCGAGGTCCACACCTGAGTTGG-3’ and 5’-AAACTCCTAGTCCACACCTGAGG-3’ that encompassed all known or predicted transcript variants (90), and resulted in a single band on a DNA gel. Amplified LGALS3BP was ligated into pCMV and sequenced at Lonestar Labs (Houston, TX), using the primers listed above and internal primers (5’-CGCCCTGGGCTTCTGTGG-3’ and 5’-GGTCTATCAGTCCAGACG-3’).

Isolation of mouse spleen cells

SIGN-R1 −/− spleens were developed by Andrew McKenzie (91) and were the kind gift of Dr. Jeffrey Ravetch at Rockefeller University. Mouse spleen cells were isolated and cultured as previously described (92).

Staining of biopsies

De-identified slides of formalin fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies or surgical specimens from patients with confirmed infiltrative ductal carcinoma of the breast were kindly provided by Dr. Kelly Hunt at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Patients signed informed consent prior to the initiation of treatment. The M.D. Anderson Institutional Review Board approved the use of all patient-derived tissues and data. Slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanols. Antigens were retrieved by incubating sections with Antigen Unmasking Solution H-3300 (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) in a steamer for 20 minutes. Slides were then permeabilized by incubating with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 45 minutes at room temperature. Slides were blocked by incubating with 1% Bovine Serum Albumin in PBS for one hour at room temperature. Slides were then incubated with primary antibody diluted in 0.1% BSA/PBS overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were collagen-I (Rabbit pAb, 1:500, Abcam #ab34710), CD45RO (Mouse mAb, 1:100, Biolegend #304202), LGALS3BP (Rabbit pAb, 1:200, GeneTex #GTX116497), galectin-3 (Rat mAb, 1:200, BioLegend #125401). Secondary antibody in 0.1% BSA/PBS was then added for one hour at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were donkey anti-mouse DyLight 488, donkey anti-rabbit Red X, and goat anti-rat 488 (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were DAPI stained for 10 minutes and mounted with Dako Fluorescent mounting medium (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Images were captured with an Olympus BX51 microscope and Olympus DP72 camera (Olympus, Tokyo, JP) and CellSens software (Center Valley, PA).

Statistics

Statistics were performed using Prism (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences were assessed by two-tailed t-tests or two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests. Significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

MDA-MB 231 and MDA-MB 435 cells secrete factors that inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation

To determine whether factors secreted from tumors might promote or inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, we examined the effect of conditioned media (CM) from a variety of human tumor cell lines on human monocytes cultured in serum-free medium and measured the resulting monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. In our culture conditions, monocyte-derived fibrocytes express canonical fibrocyte markers (8). Human PBMC were incubated in the presence or absence of tumor cell line CM, and after 5 days, monocyte-derived fibrocytes were counted. In the absence of CM, we observed 81 to 1374 monocyte-derived fibrocytes per 105 PBMCs from the different donors, similar to what we have previously observed (65). Per 105 PBMC originally added to each well, 17,617 ± 5720 (mean ± SD, n = 38) remained adhered to the plate after fixation. Of these, 638 ± 278 had a monocyte-derived fibrocyte morphology and 6062 ± 2208 had a phenotype similar to macrophages cultured in serum and MCSF (8). Because of this variability, monocyte-derived fibrocyte numbers were thus normalized to CM-free controls. CM from MDA-MB-231 (231) (40) and MDA-MB-435 (435) cells (66) inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A), and this effect was observed for PBMC from all donors tested. The 435 CM did not affect the number of adherent cells after removing weakly adhering cells, and then fixing and staining, while 231 CM slightly inhibited adherent cell number only at 12.5% CM, which is well above the IC50 for monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibition (Fig. 1B, and S1B). PBMC exposed to 231 CM or 435 CM for 5 days did not have significantly increased cell death as assessed by propidium iodide staining (Fig. C, and S1C), or decreased total cell number (this includes the weakly adherent cells removed before fixing and staining) as assessed by removing all cells from the assay well and counting by flow cytometry (Fig. 1D and S1D). Some concentrations of 231 CM increased total cell numbers (Fig. 1D). This may due to factors in the conditioned media that promote cell survival and/or cell proliferation.

Figure 1. MDA-MB 231 conditioned media inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation.

(A) PBMC were cultured in serum free media in the presence of the indicated concentrations of MDA-MB 231 (231 CM) conditioned media for five days. Monocyte-derived fibrocyte counts were normalized for each donor to the SFM control. (B) Counts of total adherent PBMC per five fields of view at the indicated concentrations of 231 CM. (C) Total propidium iodide positive PBMC, and (D) total PBMC, after 5 days at the indicated concentrations of 231 CM, measured by flow cytometry. (E) Total number of monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes cultured at the indicated concentrations of 231 CM for 5 days. Monocytes were 16% ± 9% (mean ± SEM, n=3) of the PBMCs and 92% ± 5% in the purified fraction. (F) Total number of macrophages from PBMC cultured at the indicated concentrations of 231 CM for 5 days. Values are mean ± SEM. The absence of error bars indicates that the error was smaller than the plot symbol. (A, B, F) n=38, (C, D, E) n=3. * indicates p < .05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the control (t-test).

Monocyte-derived fibrocytes differentiate from monocytes (3, 16, 17). Cells in the PBMC population include T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, and other cells in addition to monocytes (15). To determine whether the CM effect on monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation is a direct effect on monocytes, or is mediated by the other cells in a PBMC population, 231 or 435 CM was added to purified human monocytes. 231 CM and 435 CM inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation from purified monocytes (Fig. 1E, and S1E). For the inhibition of monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation from PBMC, the IC50 of 231 CM was 0.33 ± 0.05% (mean ± SEM, n=37, Hill coefficient 1.06 ± 0.13), and that of 435 CM was 0.45 ± 0.17% (n=7, Hill coefficient 0.73 ± 0.20). When added to monocytes, the 231 and 435 IC50s were 1.2 ± 0.2% (n=5, Hill coefficient 1.08 ± 0.15) and 1.9 ± 0.7% (n=3, Hill coefficient 1.70 ± 0.60), respectively. The difference in IC50s for 231 CM between PBMCs and monocytes was significant with p < 0.05 (t test); the difference for 435 CM was not significant. Since purifying monocytes and thus removing other cells from the PBMC population modestly increased the 231 CM IC50, these data suggest that either the monocyte purification procedure modestly reduced the ability of monocytes to respond to the factor(s) in CM that inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, or else the presence of the other cells in the PBMC population somewhat potentiates the ability of monocytes to respond to the factor(s). In either case, the data indicate that monocytes can respond direct to the factor(s).

In addition to differentiating into monocyte-derived fibrocytes, monocytes can also differentiate into macrophages. To determine if the CMs that inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation also affect macrophage differentiation from monocytes, we counted the total number of adhered macrophages, as assessed by morphology. 231 CM caused a decrease in macrophage differentiation at 12.5% CM, but did not affect the number of macrophages at lower concentrations which inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, and 435 did not significantly inhibit macrophage differentiation (Fig. 1F, and S1F). Together, the data indicate that factors in 231 and 435 CM affect monocytes to strongly inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, while having no effect, or a relatively modest effect, on cell death, total cell numbers, numbers of macrophages, and the numbers of adherent cells.

Some but not all human cancer cell lines also secrete a monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibitory activity

To determine if other tumor types might secrete factors that inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, we exposed PBMC to conditioned media from cancer cell lines derived from human breast, skin, colon, liver, pancreas, brain, ovary, and leukocyte tissue. We defined units of activity as the inverse of the CM’s IC50 for monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibition. Of the cell lines tested, conditioned media from OVCAR-8, U-87 MG, MDA-MB 231, MDA-MB 435, MCF-7, and DCIS.com significantly inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 2). OVCAR-8 is an ovarian cancer cell line derived from a metastatic site (74, 75). U87-mg is derived from a glioblastoma (79). MDA-MB 231 is derived from a breast cancer metastasis (40). MDA-MB 435 has an uncertain origin: originally the cell line was listed as a breast cancer line by the ATCC (66). Currently, the cell line is listed as a melanoma cell line (87). MCF-7 is a breast cancer cell line derived from a pleural effusion (72). DCIS.com is derived from a normal breast tissue cell line (MCF10A) passaged through a mouse, and forms a non-metastatic ductal carcinoma in-situ when injected into mice (67). Each cell line whose CM inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation was isolated from hormone secreting tissues (breast, ovarian), with the exception of the U-87 MG and MDA-MB 435 cell lines. No colon, liver, pancreatic, or leukemia CM significantly inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 2A), and 0.4 to 10% SW480 colon cancer CM modestly potentiated monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The effect of conditioned media from other cancer cell lines on monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation.

(A) Conditioned media from 20 different cancer cell lines show different levels of potentiation and inhibition for monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. Activity Units are the dilution of CM which inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation to 50% of the control value. Higher activity units indicate more potent inhibition of monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. n=3 for Mono mac-1, Mono mac-6, U937, HL-60, THP-1, DK0B8, HCT (P21+/P53+), HCT (P21-/P53+), HCT (P21+/P53-), HCT (P21-/P53-), HEK-293, K562; n=6 for ADR-RES, OVCAR-8, snU-398, HEP-G2, U-87 MG, PANC-1, SW480, n=7 for DCIS.com, n=10 for MCF-7 and MDA-MB 435, and n=38 for MDA-MB 231. A = cancers derived from breast tissue, B = skin, C = leukocyte, D = colon, E = embryonic kidney, F = ovarian, G = Liver, H = Brain, and I = Pancreas. The absence of error bars indicates that the error was smaller than the plot symbol. # indicates inconsistent inhibition of monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (variability of response of PBMC from different donors), * indicates p < .05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the control (t-test). (B) Conditioned media from SW480 cells potentiated monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. Values are mean ± SEM, n=6. * indicates p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the control (t-test).

The 231 monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibitor is a protein, and can be concentrated and purified

To determine if the monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibition activity in 231 conditioned media is due to a protein, we exposed conditioned media to trypsin, heat, and freeze-thaw cycles. All three treatments strongly decreased the ability of 231 CM to inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. S2). The 231 CM retained ~80% activity after clarification by ultracentrifugation, and was largely retained by a 100 kDa filter (Fig. 3A). The components of 231 CM that passed through a 100 kDa filter potentiated monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. S3A). This potentiating activity was retained by a 10 kDa filter (Fig. S3B). Together, these results suggest that the 231 CM activity which inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation is a protein.

Figure 3. MDA-MB 231 conditioned media’s monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibitory activity is greater than 100 kDa.

(A) The indicated fractions were assessed for their ability to inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. The activity units were normalized to the value for the CM. Values are mean ± SEM, n=24.

To purify the 231 CM monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation inhibitor, the 100 kDa retentate was fractionated by anion exchange chromatography, and fractions were assayed for activity (Fig. 4A). There was little activity in the flow-through, some activity throughout the elution, and a large peak of activity in fractions 27 and 28, corresponding to a NaCl concentration of 375 mM. The IC50 of both of these fractions occurred at a ~4,096-fold dilution, with a Hill coefficient of 4.6 ± 1.7 (mean ± SEM, n=6). Silver-stained gels showed prominent bands at ~85 and ~39 kDa in fraction 27 (Fig. 4B). Tryptic fragments of proteins in fraction 27 were analyzed by mass spectrometry. In decreasing order of the number of identified peptides, the identified proteins were human galectin-3 binding protein, desmoplakin, plakoglobin, desmoglein type 1, pentraxin-3 (PTX-3), adult intestinal phosphatase, and dermcidin. However, after purifying peptides with a Ziptip, the only identified peptides corresponded to galectin-3 binding protein (LGALS3BP; GI:5031863).

Figure 4. Anion exchange chromatography of the partially purified factor.

(A) 100 kDa concentrated MDA-MB 231 CM, produced as in Figure 3, was fractionated on an anion exchange column. Fractions were assayed as in Figure 1, and the resulting monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibition was measured by activity units, as in Figure 2. (B) SDS-PAGE gel of the fractions, silver stained.

Immunodepletion of LGALS3BP from CM removes most of the monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibitory activity

To determine if the LGALS3BP detected in CM affects monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, we immunodepleted LGALS3BP from 231 and 435 CM. Immunodepletion with a control antibody had little effect on the ability of CM to inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 5 and S3). Immunodepletion of LGALS3BP from 231 CM (Fig. 5) increased the IC50 by 8.6 ± 1.3 fold (mean ± SEM, n=7, p < 0.001, t-test). Similarly, immunodepletion of LGALS3BP from 435 CM (Fig. S3) increased the IC50 by 21 ± 11 fold (mean ± SEM, n=7, p < 0.001, t-test). These results suggest that LGALS3BP is a significant component of the 231 and 435 CM monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibitory activity.

Figure 5. Immunodepletion of LGALS3BP decreases MDA-MB 231 CM’s monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibitory activity.

MDA-MB 231 CM was immunodepleted with anti-LGALS3BP or isotype control antibodies. Values are mean ± SEM, n=7.

Recombinant LGALS3BP inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation

To test the hypothesis that LGALS3BP inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, we incubated PBMC with recombinant human LGALS3BP. LGALS3BP significantly inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation with an IC50 of 0.22 ± 0.05 µg/ml (Hill coefficient 6.5 ± 2.2) (Fig. 6), but unlike 231 CM (Fig. A), did not completely inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. Together with the immunodepletion assays, the data indicate that LGALS3BP does inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation.

Figure 6. Recombinant LGALS3BP inhibits monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation.

Recombinant LGALS3BP was added to PBMC, and monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation was assessed as in Figure 1. Values are mean ± SEM, n=8. * indicates p < .05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 compared to the control (t-test).

The 231 LGALS3BP mRNA encodes a canonical LGALS3BP

LGALS3BP has an experimentally verified transcript variant, and several predicted transcript variants (90). To determine if MDA-MB 231 cells secreted a truncated or alternatively spliced variant of LGALS3BP, mRNA was isolated from MDA-MB 231 and converted to cDNA. Using primers which encompass all known or predicted transcript variants (90), LGALS3BP cDNA was amplified via PCR and sequenced. The sequence encoded the four LGALS3BP peptides detected by mass spectrometry, and was identical to human LGALS3BP from oral squamous carcinoma cells (93), and is identical to the sequence of the recombinant full-length human LGALS3BP (R&D datasheet).

LGALS3BP produced in cancer cells has a higher mass than recombinant LGALS3BP

To determine the concentration of LGALS3BP in CM, western blots of CM and known amounts of recombinant LGALS3BP were stained for LGALS3BP. MDA-MB 231, MDA-MB 435, and OVCAR-8 CMs showed high concentrations of LGALS3BP compared to MCF-7, DCIS.com, and U87-mg CMs (Fig. 7). MDA-MB 435, MDA-MB 231, and OVCAR-8 cells accumulated ~1 µg/ml LGALS3BP in their CMs. U-87 MG CM had very little LGALS3BP, suggesting that glioma cells may inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation by other means. LGALS3BP has a predicted mass of ~60 kDa, but LGALS3BP isolated from the serum of cancer patients has a mass of ~90 kDa (50) and the LGALS3BP we observed in cancer cell CMs has a mass of ~85 kDa. While LGALS3BP in cancer CM appears as a single band, the recombinant LGALS3BP from CHO cells has several bands. R&D Systems is the only manufacturer of recombinant LGALS3BP produced in eukaryotic cells.

Figure 7. High concentrations of LGALS3BP are present in 321 and 435 conditioned media.

Western blot of equal volumes of the indicated concentrations (in ng/ml) of recombinant LGALS3BP and conditioned media from the indicated cell types were stained with anti-LGALS3BP antibodies. Blot image is representative of three separate experiments.

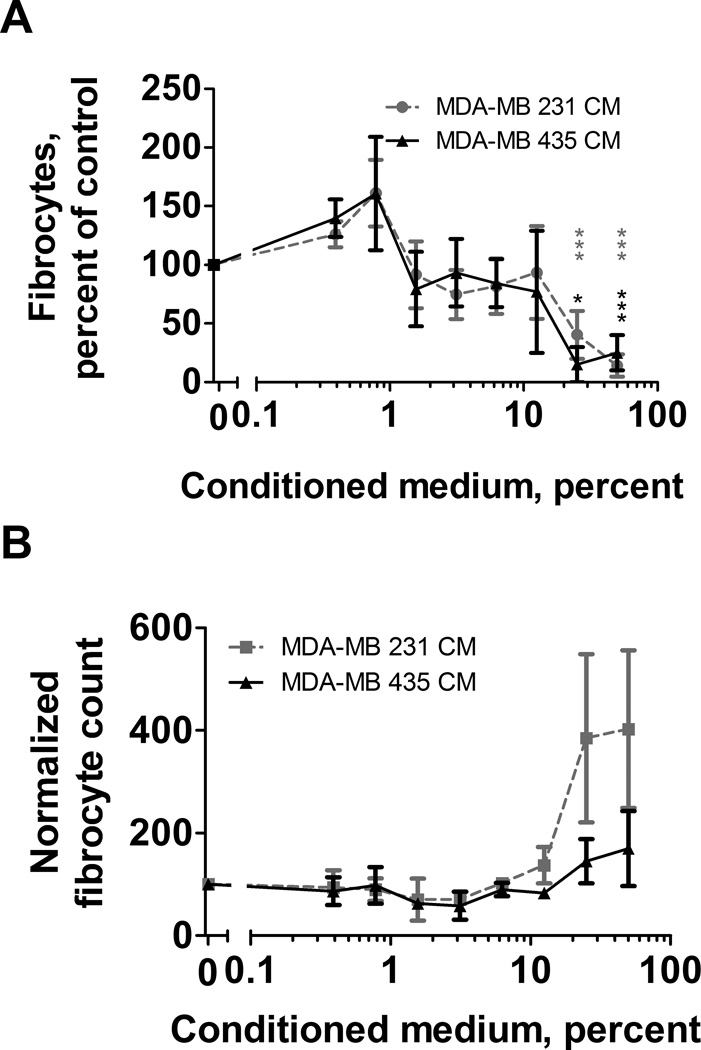

231 and 435 CMs inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation using a DC-SIGN-dependent mechanism

The C-type lectin receptor DC-SIGN/CD209 is expressed on monocytes, and is upregulated as monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells (94). IgG is capable of inducing a pro- or anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype by interacting with monocytes (95). IgG that is glycosylated with N-linked sialic-acid glycans binds DC-SIGN, and causes macrophages to secrete IL-10, reducing inflammation (95, 96). Both glycosylated IgG and LGALS3BP bind human DC-SIGN (44, 95). To determine if the DC-SIGN receptor might mediate the effect of LGALS3BP on monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, we added 231 CM and 435 CM to PBMC from WT and CD209−/− (SIGN-R1−/−) mice. 231 CM and 435 CM inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation from wild type C57BL/6 mouse spleen cells, but potentiated monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation from CD209 knockout mouse spleen cells (Fig. 8) in a similar manner to 231 CM components that passed through a 100 kDa filter (Fig. S3). Recombinant LGALS3BP, 231 CM, and 435 CM each upregulated CD209 expression on PBMC and decreased the number of fibronectin-positive monocyte-derived fibrocytes (Fig. S4).

Figure 8. CD209 (SIGN-R1) is needed for the effect of MDA-MB 231 and MDA-MB 435 CM on mouse monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation.

Cells were isolated from mouse spleens and incubated with the indicated concentrations of CM. Spleen cells from (A) wild-type C57BL/6 and (B) SIGN-R1 −/− knockout mice were incubated with the indicated concentrations of MDA-MB 231 or MDA-MB 435 CM. After 5 days, monocyte-derived fibrocytes were counted. Values are mean ± SEM, n=3, * indicates p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to the control (t-test).

Galectin-3 and galectin-1 potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation

Galectin-1 and galectin-3 are binding partners for LGALS3BP (50, 97). To determine if galectins −1 and −3 affect monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, we incubated PBMC with recombinant human galectins −1 and −3 (98, 99). Galectin-1 and −3 significantly potentiated monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. S4C). To determine how a mixture of galectin-3 and LGALS3BP would influence monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, recombinant galectin-3 and LGALS3BP were co-incubated with PBMC. Concentrations of galectin-3 that potentiated monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation continued to potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation when mixed with concentrations of LGALS3BP that inhibited monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. 6 and S4D). Galectin-3 did not potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation when mixed with a 3-fold higher quantity of LGALS3BP (Fig. S4D). This suggests that the monocyte-derived fibrocyte-potentiating effect of galectin-3 competes with the monocyte-derived fibrocyte-inhibiting effect of LGALS3BP.

Increased LGALS3BP expression at the interface between breast cancer and scar tissue

To determine how tumor cells, LGALS3BP, galectin-3, and monocyte-derived fibrocytes interact in human tumors, we stained sections of human infiltrative ductal carcinomas for CD45RO, pro-collagen, collagen-I, galectin-3, and LGALS3BP. For all biopsies tested, the tumor cells strongly expressed LGALS3BP and pro-collagen. The staining intensity of LGALS3BP increased at the interface of tumor cells and stroma, particularly where tumor cells were invading through layers of collagen-rich stroma (Fig. 9). Monocyte-derived fibrocytes at the tumor edge were pro-collagen and collagen-1 positive, while the scar tissue was negative for pro-collagen and positive for collagen-1. ‘X’ indicates the tumor, the arrow indicates tumor infiltration into scar tissue, and ‘*’ indicates areas with monocyte-derived fibrocytes. Galectin-3 colocalized with the monocyte-derived fibrocyte markers CD45RO and collagen-I (Fig. 9). These data suggest that in some breast tumors, LGALS3BP expression is increased at the interface between the tumor and desmoplastic tissue, and that monocyte-derived fibrocytes are reduced when LGALS3BP expression is increased. Intriguingly, galectin-3, which we observed to potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, colocalized with monocyte-derived fibrocytes (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Breast cancer tumor sections visualized by immunofluorescence show increased LGALS3BP at the edge of tumors.

Human infiltrative ductal carcinoma tumor specimens were sectioned and stained for CD45RO, collagen-1, pro-collagen LGALS3BP, and galectin-3. Images are (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of a representative biopsy section, (C) immunofluorescence for collagen (red) and CD45RO (green), and (D) immunofluorescence for LGALS3BP (red) and galectin-3 (green), and (E and F) immunofluorescence for pro-collagen (red) and CD45 (green). Yellow indicates co-localization. The boxes in (A and E) indicate areas of magnification for B-E and F, respectively. The image in panel F extends slightly below the white box in panel E. ‘X’ indicates the tumor, the arrow indicates tumor infiltration into scar tissue, and ‘*’ indicates areas with monocyte-derived fibrocytes. Bar in A is 200µm, bars in B through F are 20 µm.

Discussion

In this report, we show that several human tumor cell lines secrete activity that inhibits the differentiation of human monocytes into monocyte-derived fibrocytes. For a metastatic breast cell line and a metastatic melanoma cell line, the majority of the activity is LGALS3BP. LGALS3BP produced by cancer cells appears to act through the CD209 receptor to inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. LGALS3BP’s binding partner, galectin-3, is upregulated in fibrotic tissue surrounding breast cancer tumors, and promotes monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation at physiological concentrations. In breast cancer biopsies, LGALS3BP is concentrated at the edge of the tumor in regions with fewer monocyte-derived fibrocytes. Taken together, this suggests that LGALS3BP may inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation to facilitate metastasis in breast cancer and melanoma.

LGALS3BP (Mac2-BP, Antigen 90K) is a secreted member of the scavenger-receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) family of proteins (50). LGALS3BP binds to galectins −1 and −3 (100), both collagen and fibronectin (101), and increases cell adhesion (97). Mouse knockouts of LGALS3BP show higher circulating levels of TNF-alpha, IL-12, and IFN-γ, suggesting multiple roles in regulating the immune system (102).

MCF-7 and DCIS.com cells, which are derived from non-metastatic breast cancers (67, 72), accumulate relatively low extracellular levels of LGALS3BP, while MDA-MB 231 cells, which are derived from a metastatic breast cancer (40), accumulate high extracellular levels of LGALS3BP (103–109). Patients with metastatic breast cancer tend to have abnormally high serum levels of LGALS3BP (50, 52). MDA-MB 435 accumulates high concentrations of extracellular LGALS3BP compared to other cancer cell lines (110), and patients with metastatic melanoma have higher serum LGALS3BP than patients with benign skin cancer (111). In patients with breast cancer (112, 113), ovarian cancer (114–117), or melanoma (118–120), serum LGALS3BP concentrations increase during the progression to metastasis (49, 121). An intriguing possibility is that LGALS3BP may play a role in metastasis by inhibiting monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation.

The Hill coefficient of recombinant LGALS3BP for monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibition is 6.5, but 231 and 435 CM have Hill coefficients close to 1. Fractions of 231 CM containing LGALS3BP have a Hill coefficient of 4.6. Both 231 CM and 435 CM contain a factor (or factors) that potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation (Fig. S3), suggesting that perhaps LGALS3BP competes with these factors to produce a Hill coefficient of ~1. Recombinant LGALS3BP, 231 CM, and 435 CM all increase CD209 staining on monocytes, suggesting that LGALS3BP may cooperatively bind to monocytes by increasing CD209 expression.

LGALS3BP secreted from MDA-MB 231 cells has a higher apparent mass than recombinant LGALS3BP produced in CHO cells, despite the two having an identical primary structure. Since LGALS3BP is glycosylated (44), this suggests that the LGALS3BPs from the two cell lines have different glycosylations and/or other posttranslational modifications. MDA-MB 231 and 435 secrete ~1 µg/ml of LGALS3BP into conditioned media, and 231 and 435 CM have an IC50 for monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation of ~0.3% (Fig. 1 and S1). Taken together, these results indicate that the IC50 for LGALS3BP should be ~0.3% × 1 µg/ml = ~3 ng/ml. Recombinant LGALS3BP’s IC50 for monocyte-derived fibrocyte inhibition was 300 ng/ml. This then suggests that glycosylation and/or posttranslational modification of LGALS3BP may affect its ability to inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. In agreement with this, LGALS3BP produced by cancer cells has at least a fourfold higher affinity for CD209 (DCSIGN) receptors than LGALS3BP produced by non-cancer cells (44). The CD209 receptor, which we found to be necessary for the ability of LGALS3BP to inhibit monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, is activated by posttranslational glycosylations (95). A reasonable possibility is thus that the posttranslational glycosylations of LGALS3BP produced in CHO and MDA-MB 231 cells have different affinities for CD209, resulting in the observed differences in IC50’s.

Galectin-3 is expressed by monocytes and macrophages (122). Serum galectin-3 is upregulated in heart disease and other fibrosing diseases (123), and inhibitors of galectin-3 are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of fibrosing diseases (124, 125). While serum galectin-3 is 100–900 ng/ml (98), we observed potentiation of monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation at 2.5 to 5 µg/ml. Similar concentrations of galectin-3 are necessary to induce changes in other cells (99), suggesting that either the effects of galectin-3 we and others observed in tissue culture are not physiological, or that extracellular concentrations of galectin-3 in some tissues may be much higher than in the serum. If galectin-3 levels in a tissue are high enough to potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, this would suggest that high levels of galectin-3 could potentiate fibrosis in part by potentiating monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation. Since we observed that galectin-1 also potentiates monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, high levels of galectin-1 may similarly potentiate fibrosis.

Together, this work elucidates a signal and receptor used by metastatic tumor cells to block a response of the innate immune system. An intriguing possibility is that blocking LGALS3BP may decrease the ability of tumor cells to inhibit the desmoplastic response and metastasize. Conversely, LGALS3BP might be useful to decrease monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation and thus decrease fibrosis. Since galectin-3 and galectin-1 potentiate monocyte-derived fibrocyte differentiation, these proteins might be useful to inhibit metastasis, although with the danger that they might promote fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Kelly Hunt, M.D. and Cansu Karakas, M.D. at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center for providing human breast cancer patient slides and aiding in interpretation of the immunofluorescent staining. We thank Darrell Pilling and Nehemiah Cox for advice. We would also like to thank the volunteers who donated blood and the phlebotomy staff at the Texas A&M Beutel student health center.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants T32CA009599 (DR) and HL118507 (RHG).

References

- 1.Hamilton JA. Colony-stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:533–544. doi: 10.1038/nri2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1:71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White MJ, Galvis-Carvajal ED, Gomer RH. A brief exposure to tryptase or thrombin potentiates fibrocyte differentiation in the presence of serum or SAP. Journal of Immunology. 2014 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suko T, Ichimiya I, Yoshida K, Suzuki M, Mogi G. Classification and culture of spiral ligament fibrocytes from mice. Hearing research. 2000;140:137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strieter RM, Keeley EC, Hughes MA, Burdick MD, Mehrad B. The role of circulating mesenchymal progenitor cells (fibrocytes) in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1111–1118. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0309132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilling D, Fan T, Huang D, Kaul B, Gomer RH. Identification of markers that distinguish monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellini A, Mattoli S. The role of the fibrocyte, a bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor, in reactive and reparative fibroses. Lab Invest. 2007;87:858–870. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paget J. Lectures on Surgical Pathology Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. London: Wilson and Ogilvy; 1853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattoli S, Bellini A, Schmidt M. The role of a human hematopoietic mesenchymal progenitor in wound healing and fibrotic diseases and implications for therapy. Current stem cell research & therapy. 2009;4:266–280. doi: 10.2174/157488809789649232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellini A, Marini MA, Bianchetti L, Barczyk M, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. Interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-17A differentially affect the profibrotic and proinflammatory functions of fibrocytes from asthmatic patients. Mucosal immunology. 2012;5:140–149. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isgro M, Bianchetti L, Marini MA, Bellini A, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. The C-C motif chemokine ligands CCL5, CCL11, and CCL24 induce the migration of circulating fibrocytes from patients with severe asthma. Mucosal immunology. 2013;6:718–727. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bianchetti L, Marini MA, Isgro M, Bellini A, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. IL-33 promotes the migration and proliferation of circulating fibrocytes from patients with allergen-exacerbated asthma. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2012;426:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Gomer RH. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. J Immunol. 2003;171:5537–5546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilling D, Vakil V, Gomer RH. Improved serum-free culture conditions for the differentiation of human and murine fibrocytes. J Immunol Methods. 2009;351:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reilkoff RA, Bucala R, Herzog EL. Fibrocytes: emerging effector cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:427–435. doi: 10.1038/nri2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moeller A, Gilpin SE, Ask K, Cox G, Cook D, Gauldie J, Margetts PJ, Farkas L, Dobranowski J, Boylan C, O’Byrne PM, Strieter RM, Kolb M. Circulating fibrocytes are an indicator of poor prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:588–594. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1534OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan TE, Cowper SE, Bucala R. The role of circulating fibrocytes in fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:145–150. doi: 10.1007/s11926-006-0055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strieter RM, Keeley EC, Burdick MD, Mehrad B. The role of circulating mesenchymal progenitor cells, fibrocytes, in promoting pulmonary fibrosis. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2009;120:49–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pilling D, Roife D, Wang M, Ronkainen SD, Crawford JR, Travis EL, Gomer RH. Reduction of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by serum amyloid P. J Immunol. 2007;179:4035–4044. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naik-Mathuria B, Pilling D, Crawford JR, Gay AN, Smith CW, Gomer RH, Olutoye OO. Serum amyloid P inhibits dermal wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herzog EL, Bucala R. Fibrocytes in health and disease. Experimental hematology. 2010;38:548–556. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrade ZA. Schistosomiasis and liver fibrosis. Parasite immunology. 2009;31:656–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boros DL. Immunopathology of Schistosoma mansoni infection. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1989;2:250–269. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.3.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wahl SM, Frazier-Jessen M, Jin WW, Kopp JB, Sher A, Cheever AW. Cytokine regulation of schistosome-induced granuloma and fibrosis. Kidney international. 1997;51:1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyler DJ, Wahl SM, Wahl LM. Hepatic fibrosis in schistosomiasis: egg granulomas secrete fibroblast stimulating factor in vitro. Science. 1978;202:438–440. doi: 10.1126/science.705337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schedin P, Elias A. Multistep tumorigenesis and the microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:93–101. doi: 10.1186/bcr772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim BG, An HJ, Kang S, Choi YP, Gao MQ, Park H, Cho NH. Laminin-332-rich tumor microenvironment for tumor invasion in the interface zone of breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coulson-Thomas VJ, Coulson-Thomas YM, Gesteira TF, de Paula CA, Mader AM, Waisberg J, Pinhal MA, Friedl A, Toma L, Nader HB. Colorectal cancer desmoplastic reaction up-regulates collagen synthesis and restricts cancer cell invasion. Cell Tissue Res. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cichon MA, Degnim AC, Visscher DW, Radisky DC. Microenvironmental influences that drive progression from benign breast disease to invasive breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2010;15:389–397. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9195-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao ZM, Nguyen M, Barsky SH. Human breast carcinoma desmoplasia is PDGF initiated. Oncogene. 2000;19:4337–4345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker RA. The complexities of breast cancer desmoplasia. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3:143–145. doi: 10.1186/bcr287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coulson-Thomas VJ, Coulson-Thomas YM, Gesteira TF, de Paula CA, Mader AM, Waisberg J, Pinhal MA, Friedl A, Toma L, Nader HB. Colorectal cancer desmoplastic reaction up-regulates collagen synthesis and restricts cancer cell invasion. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;346:223–236. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finn OJ. Immuno-oncology: understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in cancer. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2012;23(Suppl 8):viii6–viii9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nature immunology. 2013;14:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solito S, Pinton L, Damuzzo V, Mandruzzato S. Highlights on molecular mechanisms of MDSC-mediated immune suppression: paving the way for new working hypotheses. Immunological investigations. 2012;41:722–737. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2012.678023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biragyn A, Longo DL. Neoplastic “Black Ops”: cancer’s subversive tactics in overcoming host defenses. Seminars in cancer biology. 2012;22:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakshmi Narendra B, Eshvendar Reddy K, Shantikumar S, Ramakrishna S. Immune system: a double-edged sword in cancer. Inflammation research : official journal of the European Histamine Research Society [et al.] 2013;62:823–834. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cailleau R, Young R, Olive M, Reeves WJ., Jr Breast tumor cell lines from pleural effusions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1974;53:661–674. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdelkarim M, Vintonenko N, Starzec A, Robles A, Aubert J, Martin ML, Mourah S, Podgorniak MP, Rodrigues-Ferreira S, Nahmias C, Couraud PO, Doliger C, Sainte-Catherine O, Peyri N, Chen L, Mariau J, Etienne M, Perret GY, Crepin M, Poyet JL, Khatib AM, Di Benedetto M. Invading basement membrane matrix is sufficient for MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells to develop a stable in vivo metastatic phenotype. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koths K, Taylor E, Halenbeck R, Casipit C, Wang A. Cloning and characterization of a human Mac-2-binding protein, a new member of the superfamily defined by the macrophage scavenger receptor cysteine-rich domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:14245–14249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ullrich A, Sures I, D’Egidio M, Jallal B, Powell TJ, Herbst R, Dreps A, Azam M, Rubinstein M, Natoli C, et al. The secreted tumor-associated antigen 90K is a potent immune stimulator. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18401–18407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nonaka M, Ma BY, Imaeda H, Kawabe K, Kawasaki N, Hodohara K, Kawasaki N, Andoh A, Fujiyama Y, Kawasaki T. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) recognizes a novel ligand, Mac-2-binding protein, characteristically expressed on human colorectal carcinomas. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22403–22413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.215301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resnick D, Pearson A, Krieger M. The SRCR superfamily: a family reminiscent of the Ig superfamily. Trends in biochemical sciences. 1994;19:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.D’Ostilio N, Sabatino G, Natoli C, Ullrich A, Iacobelli S. 90K (Mac-2 BP) in human milk. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1996;104:543–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.40745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iacobelli S, Arno E, D’Orazio A, Coletti G. Detection of antigens recognized by a novel monoclonal antibody in tissue and serum from patients with breast cancer. Cancer research. 1986;46:3005–3010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Ao X, Vuong H, Konanur M, Miller FR, Goodison S, Lubman DM. Membrane glycoproteins associated with breast tumor cell progression identified by a lectin affinity approach. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4313–4325. doi: 10.1021/pr8002547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mbeunkui F, Metge BJ, Shevde LA, Pannell LK. Identification of differentially secreted biomarkers using LC-MS/MS in isogenic cell lines representing a progression of breast cancer. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2993–3002. doi: 10.1021/pr060629m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grassadonia A, Tinari N, Iurisci I, Piccolo E, Cumashi A, Innominato P, D’Egidio M, Natoli C, Piantelli M, Iacobelli S. 90K (Mac-2 BP) and galectins in tumor progression and metastasis. Glycoconjugate journal. 2004;19:551–556. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000014085.00706.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tinari N, Lattanzio R, Querzoli P, Natoli C, Grassadonia A, Alberti S, Hubalek M, Reimer D, Nenci I, Bruzzi P, Piantelli M, Iacobelli S, Consorzio Interuniversitario Nazionale per la B-O. High expression of 90K (Mac-2 BP) is associated with poor survival in node-negative breast cancer patients not receiving adjuvant systemic therapies. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2009;124:333–338. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iacobelli S, Sismondi P, Giai M, D’Egidio M, Tinari N, Amatetti C, Di Stefano P, Natoli C. Prognostic value of a novel circulating serum 90K antigen in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:172–176. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes RC. Secretion of the galectin family of mammalian carbohydrate-binding proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1999;1473:172–185. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piccolo E, Tinari N, Semeraro D, Traini S, Fichera I, Cumashi A, La Sorda R, Spinella F, Bagnato A, Lattanzio R, D’Egidio M, Di Risio A, Stampolidis P, Piantelli M, Natoli C, Ullrich A, Iacobelli S. LGALS3BP, lectin galactoside-binding soluble 3 binding protein, induces vascular endothelial growth factor in human breast cancer cells and promotes angiogenesis. Journal of molecular medicine. 2013;91:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0936-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trahey M, Weissman IL. Cyclophilin C-associated protein: a normal secreted glycoprotein that down-modulates endotoxin and proinflammatory responses in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3006–3011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moutsatsos IK, Wade M, Schindler M, Wang JL. Endogenous lectins from cultured cells: nuclear localization of carbohydrate-binding protein 35 in proliferating 3T3 fibroblasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84:6452–6456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hughes RC. The galectin family of mammalian carbohydrate-binding molecules. Biochemical Society transactions. 1997;25:1194–1198. doi: 10.1042/bst0251194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu XC, el-Naggar AK, Lotan R. Differential expression of galectin-1 and galectin-3 in thyroid tumors. Potential diagnostic implications. The American journal of pathology. 1995;147:815–822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coli A, Bigotti G, Zucchetti F, Negro F, Massi G. Galectin-3, a marker of well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma, is expressed in thyroid nodules with cytological atypia. Histopathology. 2002;40:80–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gruson D, Ko G. Galectins testing: new promises for the diagnosis and risk stratification of chronic diseases? Clinical biochemistry. 2012;45:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCullough PA, Olobatoke A, Vanhecke TE. Galectin-3: a novel blood test for the evaluation and management of patients with heart failure. Reviews in cardiovascular medicine. 2011;12:200–210. doi: 10.3909/ricm0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sundblad V, Croci DO, Rabinovich GA. Regulated expression of galectin-3, a multifunctional glycan-binding protein, in haematopoietic and non-haematopoietic tissues. Histology and histopathology. 2011;26:247–265. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krzeslak A, Lipinska A. Galectin-3 as a multifunctional protein. Cellular & molecular biology letters. 2004;9:305–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cox N, Pilling D, Gomer RH. NaCl Potentiates Human Fibrocyte Differentiation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.White MJ, Glenn M, Gomer RH. Trypsin potentiates human fibrocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cailleau R, Olive M, Cruciger QV. Long-term human breast carcinoma cell lines of metastatic origin: preliminary characterization. In vitro. 1978;14:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF02616120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller FR, Santner SJ, Tait L, Dawson PJ. MCF10DCIS.com xenograft model of human comedo ductal carcinoma in situ. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:1185–1186. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1185a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Kleist S, Chany E, Burtin P, King M, Fogh J. Immunohistology of the antigenic pattern of a continuous cell line from a human colon tumor. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1975;55:555–560. doi: 10.1093/jnci/55.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leibovitz A, Stinson JC, McCombs WB, 3rd, McCoy CE, Mazur KC, Mabry ND. Classification of human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1976;36:4562–4569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shirasawa S, Furuse M, Yokoyama N, Sasazuki T. Altered growth of human colon cancer cell lines disrupted at activated Ki-ras. Science. 1993;260:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.8465203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dexter DL, Barbosa JA, Calabresi P. N,N-dimethylformamide-induced alteration of cell culture characteristics and loss of tumorigenicity in cultured human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1979;39:1020–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soule HD, Vazguez J, Long A, Albert S, Brennan M. A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from a breast carcinoma. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1973;51:1409–1416. doi: 10.1093/jnci/51.5.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scudiero DA, Monks A, Sausville EA. Cell line designation change: multidrug-resistant cell line in the NCI anticancer screen. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:862. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hamilton TC, Young RC, McKoy WM, Grotzinger KR, Green JA, Chu EW, Whang-Peng J, Rogan AM, Green WR, Ozols RF. Characterization of a human ovarian carcinoma cell line (NIH:OVCAR-3) with androgen and estrogen receptors. Cancer Res. 1983;43:5379–5389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamilton TC, Young RC, Ozols RF. Experimental model systems of ovarian cancer: applications to the design and evaluation of new treatment approaches. Seminars in oncology. 1984;11:285–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park JG, Lee JH, Kang MS, Park KJ, Jeon YM, Lee HJ, Kwon HS, Park HS, Yeo KS, Lee KU, et al. Characterization of cell lines established from human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:276–282. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aden DP, Fogel A, Plotkin S, Damjanov I, Knowles BB. Controlled synthesis of HBsAg in a differentiated human liver carcinoma-derived cell line. Nature. 1979;282:615–616. doi: 10.1038/282615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fogh J, Fogh JM, Orfeo T. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1977;59:221–226. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ponten J, Macintyre EH. Long term culture of normal and neoplastic human glia. Acta pathologica et microbiologica Scandinavica. 1968;74:465–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1968.tb03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lieber M, Mazzetta J, Nelson-Rees W, Kaplan M, Todaro G. Establishment of a continuous tumor-cell line (panc-1) from a human carcinoma of the exocrine pancreas. Int J Cancer. 1975;15:741–747. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910150505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steube KG, Teepe D, Meyer C, Zaborski M, Drexler HG. A model system in haematology and immunology: the human monocytic cell line MONO-MAC-1. Leukemia research. 1997;21:327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(96)00129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Thiel E, Futterer A, Herzog V, Wirtz A, Riethmuller G. Establishment of a human cell line (Mono Mac 6) with characteristics of mature monocytes. Int J Cancer. 1988;41:456–461. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sundstrom C, Nilsson K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937) Int J Cancer. 1976;17:565–577. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Collins SJ, Gallo RC, Gallagher RE. Continuous growth and differentiation of human myeloid leukaemic cells in suspension culture. Nature. 1977;270:347–349. doi: 10.1038/270347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) Int J Cancer. 1980;26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Graham FL, Smiley J, Russell WC, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. The Journal of general virology. 1977;36:59–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rae JM, Creighton CJ, Meck JM, Haddad BR, Johnson MD. MDA-MB-435 cells are derived from M14 melanoma cells--a loss for breast cancer, but a boon for melanoma research. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104:13–19. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Buckley CD, Pilling D, Henriquez NV, Parsonage G, Threlfall K, Scheel-Toellner D, Simmons DL, Akbar AN, Lord JM, Salmon M. RGD peptides induce apoptosis by direct caspase-3 activation. Nature. 1999;397:534–539. doi: 10.1038/17409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salmon M, Scheel-Toellner D, Huissoon AP, Pilling D, Shamsadeen N, Hyde H, D’Angeac AD, Bacon PA, Emery P, Akbar AN. Inhibition of T cell apoptosis in the rheumatoid synovium. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:439–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI119178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.UniProt C. Activities at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D191–D198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lanoue A, Clatworthy MR, Smith P, Green S, Townsend MJ, Jolin HE, Smith KG, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. SIGN-R1 contributes to protection against lethal pneumococcal infection in mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2004;200:1383–1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Crawford JR, Pilling D, Gomer RH. Improved serum-free culture conditions for spleen-derived murine fibrocytes. J Immunol Methods. 2010;363:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Endo H, Muramatsu T, Furuta M, Uzawa N, Pimkhaokham A, Amagasa T, Inazawa J, Kozaki K. Potential of tumor-suppressive miR-596 targeting LGALS3BP as a therapeutic agent in oral cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:560–569. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bullwinkel J, Ludemann A, Debarry J, Singh PB. Epigenotype switching at the CD14 and CD209 genes during differentiation of human monocytes to dendritic cells. Epigenetics : official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2011;6:45–51. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Karlsson MC, Ravetch JV. Identification of a receptor required for the anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19571–19578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810163105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Anthony RM, Ravetch JV. A novel role for the IgG Fc glycan: the anti-inflammatory activity of sialylated IgG Fcs. Journal of clinical immunology. 2010;30(Suppl 1):S9–S14. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Inohara H, Akahani S, Koths K, Raz A. Interactions between galectin-3 and Mac-2-binding protein mediate cell-cell adhesion. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4530–4534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Iurisci I, Tinari N, Natoli C, Angelucci D, Cianchetti E, Iacobelli S. Concentrations of galectin-3 in the sera of normal controls and cancer patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2000;6:1389–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kohatsu L, Hsu DK, Jegalian AG, Liu FT, Baum LG. Galectin-3 induces death of Candida species expressing specific beta-1,2-linked mannans. J Immunol. 2006;177:4718–4726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Iurisci I, Cumashi A, Sherman AA, Tsvetkov YE, Tinari N, Piccolo E, D’Egidio M, Adamo V, Natoli C, Rabinovich GA, Iacobelli S, Nifantiev NE, Consorzio Interuniversitario Nazionale Per la B-O. Synthetic inhibitors of galectin-1 and −3 selectively modulate homotypic cell aggregation and tumor cell apoptosis. Anticancer research. 2009;29:403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sasaki T, Brakebusch C, Engel J, Timpl R. Mac-2 binding protein is a cell-adhesive protein of the extracellular matrix which self-assembles into ring-like structures and binds beta1 integrins, collagens and fibronectin. The EMBO journal. 1998;17:1606–1613. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Blake JA, Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Mouse Genome Database G. The Mouse Genome Database: integration of and access to knowledge about the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D810–D817. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Whelan SA, He J, Lu M, Souda P, Saxton RE, Faull KF, Whitelegge JP, Chang HR. Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) identified proteomic biosignatures of breast cancer in proximal fluid. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5034–5045. doi: 10.1021/pr300606e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lawlor K, Nazarian A, Lacomis L, Tempst P, Villanueva J. Pathway-based biomarker search by high-throughput proteomics profiling of secretomes. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1489–1503. doi: 10.1021/pr8008572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kulasingam V, Diamandis EP. Tissue culture-based breast cancer biomarker discovery platform. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2007–2012. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pavlou MP, Diamandis EP. The cancer cell secretome: a good source for discovering biomarkers? Journal of proteomics. 2010;73:1896–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Colzani M, Waridel P, Laurent J, Faes E, Ruegg C, Quadroni M. Metabolic labeling and protein linearization technology allow the study of proteins secreted by cultured cells in serum-containing media. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4779–4788. doi: 10.1021/pr900476b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Palazzolo G, Albanese NN, DICG, Gygax D, Vittorelli ML, Pucci-Minafra I. Proteomic analysis of exosome-like vesicles derived from breast cancer cells. Anticancer research. 2012;32:847–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang Y, Tang X, Yao L, Chen K, Jia W, Hu X, Xu LX. Lectin capture strategy for effective analysis of cell secretome. Proteomics. 2012;12:32–36. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ross DT, Scherf U, Eisen MB, Perou CM, Rees C, Spellman P, Iyer V, Jeffrey SS, Van de Rijn M, Waltham M, Pergamenschikov A, Lee JC, Lashkari D, Shalon D, Myers TG, Weinstein JN, Botstein D, Brown PO. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nature genetics. 2000;24:227–235. doi: 10.1038/73432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cesinaro AM, Natoli C, Grassadonia A, Tinari N, Iacobelli S, Trentini GP. Expression of the 90K tumor-associated protein in benign and malignant melanocytic lesions. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2002;119:187–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.17642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.He J, Whelan SA, Lu M, Shen D, Chung DU, Saxton RE, Faull KF, Whitelegge JP, Chang HR. Proteomic-based biosignatures in breast cancer classification and prediction of therapeutic response. International journal of proteomics. 2011;2011:896476. doi: 10.1155/2011/896476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kostianets O, Antoniuk S, Filonenko V, Kiyamova R. Immunohistochemical analysis of medullary breast carcinoma autoantigens in different histological types of breast carcinomas. Diagnostic pathology. 2012;7:161. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lee JH, Zhang X, Shin BK, Lee ES, Kim I. Mac-2 binding protein and galectin-3 expression in mucinous tumours of the ovary: an annealing control primer system and immunohistochemical study. Pathology. 2009;41:229–233. doi: 10.1080/00313020902756279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Iacobelli S, Bucci I, D’Egidio M, Giuliani C, Natoli C, Tinari N, Rubistein M, Schlessinger J. Purification and characterization of a 90 kDa protein released from human tumors and tumor cell lines. FEBS letters. 1993;319:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80037-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scambia G, Panici PB, Baiocchi G, Perrone L, Iacobelli S, Mancuso S. Measurement of a monoclonal-antibody-defined antigen (90K) in the sera of patients with ovarian cancer. Anticancer research. 1988;8:761–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gortzak-Uzan L, Ignatchenko A, Evangelou AI, Agochiya M, Brown KA, St Onge P, Kireeva I, Schmitt-Ulms G, Brown TJ, Murphy J, Rosen B, Shaw P, Jurisica I, Kislinger T. A proteome resource of ovarian cancer ascites: integrated proteomic and bioinformatic analyses to identify putative biomarkers. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:339–351. doi: 10.1021/pr0703223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Inohara H, Raz A. Identification of human melanoma cellular and secreted ligands for galectin-3. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1994;201:1366–1375. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Traini S, Piccolo E, Tinari N, Rossi C, La Sorda R, Spinella F, Bagnato A, Lattanzio R, D’Egidio M, Di Risio A, Tomao F, Grassadonia A, Piantelli M, Natoli C, Iacobelli S. Inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis by SP-2, an anti-lectin, galactoside-binding soluble 3 binding protein (LGALS3BP) antibody. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2014;13:916–925. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Morandi F, Corrias MV, Levreri I, Scaruffi P, Raffaghello L, Carlini B, Bocca P, Prigione I, Stigliani S, Amoroso L, Ferrone S, Pistoia V. Serum levels of cytoplasmic melanoma-associated antigen at diagnosis may predict clinical relapse in neuroblastoma patients. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2011;60:1485–1495. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chen ST, Pan TL, Juan HF, Chen TY, Lin YS, Huang CM. Breast tumor microenvironment: proteomics highlights the treatments targeting secretome. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1379–1387. doi: 10.1021/pr700745n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Liu FT, Hsu DK, Zuberi RI, Kuwabara I, Chi EY, Henderson WR., Jr Expression and function of galectin-3, a beta-galactoside-binding lectin, in human monocytes and macrophages. The American journal of pathology. 1995;147:1016–1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Grandin EW, Jarolim P, Murphy SA, Ritterova L, Cannon CP, Braunwald E, Morrow DA. Galectin-3 and the development of heart failure after acute coronary syndrome: pilot experience from PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Clin Chem. 2012;58:267–273. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.174359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Traber PG, Zomer E. Therapy of experimental NASH and fibrosis with galectin inhibitors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Traber PG, Chou H, Zomer E, Hong F, Klyosov A, Fiel MI, Friedman SL. Regression of fibrosis and reversal of cirrhosis in rats by galectin inhibitors in thioacetamide-induced liver disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.