Abstract

Traditionally, hoarding symptoms were coded under obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), however, in DSM-5 hoarding symptoms are classified as a new independent diagnosis, hoarding disorder (HD). This change will likely have a considerable impact on the self-report scales that assess symptoms of OCD, as these scales often include items measuring symptoms of hoarding. This study evaluated the psychometric properties of one of the most commonly used self-report measures of OCD symptoms, the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R), in a sample of 474 individuals with either OCD (n = 118), HD (n = 201) or no current or past psychiatric disorders (n = 155). Participants with HD were diagnosed according to the proposed DSM-5 criteria. For the purposes of this study the OCI-R was divided into two scales; the OCI-OCD (measuring the 5 dimensions of OCD) and the OCI-HD (measuring the hoarding dimension). Evidence of validity for the OCI-OCD and OCI-HD was obtained by comparing scores with the Saving Inventory Revised (SI-R), the Hoarding Rating Scale (HRS) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Receiver operating curves for both subscales indicated good sensitivity and specificity for cut-scores determining diagnostic status. The results indicated that the OCI-OCD and OCI-HD subscales are reliable and valid measures that adequately differentiate between DSM-5 diagnostic groups. Implications for the future use of the OCI-R in OCD and HD samples are discussed.

Keywords: obsessive-compulsive disorder, hoarding disorder, obsessive-compulsive inventory

The most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) has brought considerable changes to the diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). First, OCD was removed from the anxiety disorders to a newly created category, the obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (OCRD). Second, hoarding symptoms, which were traditionally encapsulated under the OCD diagnosis, were removed to a new independent diagnosis, hoarding disorder (HD), which is also listed under the OCRD category.

The OCRD category includes the diagnosis of OCD along with HD, body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania and excoriation disorder. Moving the OCD diagnosis from the anxiety disorders to the OCRD section has been contentious, with many experts in the field not supporting the reclassification (Mataix-Cols, Pertusa, & Leckman, 2007). It has been argued that OCD differs significantly from the other OCRD diagnoses in terms of clinical features and response to treatment (Abramowitz, Taylor & McKay, 2009), suggesting they should not be grouped together. However, results of a recent genetic study indicate that OCD, HD and BDD do share significant genetic variance, although excoriation and trichotillomania do not appear to fit within the new model (Monzani, Rijsdijk, Harris, & Mataix-Cols, 2014).

The separation of OCD and HD into independent diagnoses has been generally accepted. Numerous studies have demonstrated that individuals with hoarding symptoms differ from those with OCD in many respects. For instance, individuals with HD and OCD have been shown to differ in neural response to a variety of tasks including response inhibition tasks (Tolin, Witt, & Stevens, 2014) and decision making tasks (Tolin et al., 2012). Additionally, individuals with HD tend to improve significantly less in response to best practice treatment for OCD, including ERP (Mataix-Cols, Marks, Greist, Kobak, & Baer, 2002) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (Mataix-Cols, Rauch, Manzo, Jenike, & Baer, 1999) justifying HD's separate diagnostic status. While the removal of hoarding symptoms has led to greater diagnostic homogeneity of OCD, this change also has implications for self-report scales that are commonly used to assess symptoms of OCD, as these scales often include items measuring symptoms of hoarding. Therefore it is important to re-examine the psychometric properties of these measures given the new separation of OCD and HD in DSM-5.

The Obsessive Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R) (Foa et al., 2002) is one of the most commonly used self-report scales in OCD outcome research (Andersson et al., 2012; Jónsson, Hougaard, & Bennedsen, 2011; Simpson et al., 2008; Wootton et al., 2011), and has been translated into multiple languages, demonstrating its scope for use in a large number of clinical settings worldwide. It is a brief, 18-item self-report questionnaire and measures symptoms across 6 subscales including washing, checking, neutralizing, obsessing, ordering and hoarding. The six-factor structure of the OCI-R has been demonstrated consistently across numerous clinical (Gönner, Leonhart, & Ecker, 2008; Huppert et al., 2007), non-clinical (Chasson, Tang, Gray, Sun, & Wang, 2013; Solem, Hjemdal, Vogel, & Stiles, 2010), and combined samples (Foa et al., 2002; Williams, Davis, Thibodeau, & Bach, 2013). The OCI-R has shown adequate test-retest reliability in a number of samples (Foa et al., 2002; Chasson et al., 2013) and evidence of the convergent and discriminant validity of the OCI-R has been supported in previous studies (Belloch et al., 2013; Hajcak, Huppert, Simons, & Foa, 2004; Huppert et al., 2007; Solem et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2013). The OCI-R has also been demonstrated to be sensitive to treatment effects (Abramowitz, Tolin, & Diefenbach, 2005), making it useful as an outcome measure in clinical trials.

Some studies investigating the psychometric properties of the OCI-R have indicated that the hoarding subscale does not distinguish individuals with OCD from those with other anxiety disorders (Belloch et al., 2013) or from community controls (Belloch et al., 2013; Solem et al., 2010). This may potentially be due to the low number of individuals in an OCD sample endorsing symptoms of hoarding. For instance, research has indicated that clinically significant symptoms of hoarding are prevalent in less than 5% of individuals with OCD (Foa et al., 1995; Mataix-Cols, Rauch, Manzo, Jenike, & Baer, 1999) and that OCD is present in only 18% of individuals with HD (Frost, Steketee, & Tolin, 2011). Often prior studies investigating the psychometric properties of the OCI-R have not specified the number of individuals with hoarding symptoms, and investigating criterion validity of the measure may be difficult in a sample with a low number of individuals with clinically significant hoarding symptoms. An additional hypothesis however is that the 3 items measuring hoarding in the OCI-R are not sufficient to detect significant hoarding symptoms, however larger studies are needed with adequate number of individuals with hoarding symptoms to investigate this hypothesis.

Previous research has documented the diagnostic sensitivity of the OCI-R according to DSM-IV criteria for OCD, and a range of cutoff scores to identify clinically significant symptoms have been suggested. The original article (Foa et al., 2002) recommended a cutoff score of 21 to distinguish individuals with OCD from those without anxiety disorders, and the same cutoff score was recommended by others (Abramowitz et al., 2005; Belloch et al., 2013). However, other authors have recommended cut scores ranging from 14-36 for various populations (Abramowitz & Deacon, 2006; Gönner et al. 2008; Williams et al., 2013). These discrepant findings may be related to the heterogeneity of the samples, suggesting the need for further research with more clearly defined samples.

While the OCI-R is a widely utilized and well-validated measure, recent changes to DSM-5 mean that the scale now spans two diagnostic categories, suggesting a need for revision. The present study investigated the psychometric properties of the OCI-R according to DSM-5, which treats OCD and HD as separate disorders. For this study we divided the OCI-R into two separate measures: the OCI-OCD (measuring the 5 dimensions of OCD) and the OCI-HD (measuring the hoarding dimension). This study investigates the validity, reliability and diagnostic sensitivity of these measures in a sample of individuals with HD, a sample of individuals with OCD, and a group of community controls (CC) who did not endorse any current or prior psychiatric diagnoses.

Method

Data for this study was obtained from two datasets from existing studies assessing hoarding and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Tolin et al., 2012; Frost, Steketee & Tolin, 2011). Due to the different inclusion criteria for this study, the total number of participants listed differs from the original studies.

Participants

The total sample consisted of 474 adult (age 18 or older) participants (mean age = 47.40; SD = 14.23; 67% female). Of these, 201 had a primary diagnosis of HD, 118 had a primary diagnosis of OCD, and 155 were CC without a psychiatric diagnosis. Participants were recruited prior to the publication of DSM-5. For this study the diagnosis of OCD was made with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV and the diagnosis of HD was assessed against the proposed criteria at the time (Mataix-Cols et al., 2010) and was assessed with the Hoarding Rating Scale- Interview (HRS-I; Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2010). The HRS-I includes interviewer ratings of moderate or greater clutter (DSM-5 Criterion C), difficulty discarding (DSM-5 Criterion A), and either distress or impairment from hoarding symptoms (DSM-5 Criterion D). In addition, the clutter and difficulty discarding could not be attributed to another OCD symptom (e.g., contamination, checking). These criteria overlap substantially with the current DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), with the exception of Criterion B which requires that the difficulty discarding is due to a percevied need to save the items and to distress associated with discarding the item (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which is not assessed with the HRS-I. All interviews were conducted by trained clinicians with expertise in OCD and HD.

Participants were excluded from the analysis if they had missing data on the OCI-R or had comorbid OCD and HD (n = 73). Participants were excluded from participating if they had a history of psychotic disorder, substance abuse or serious suicidal ideation. Participants in the CC group were excluded if they met diagnosis for current or previous mental disorder. As this is an analysis of existing data, the number of participants excluded for these reasons is not accessible.

Measures

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS; Brown, DiNardo, & Barlow, 1994)

The ADIS is a commonly used semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to assess lifetime and current DSM-IV anxiety and related disorders. Inter-rater reliability of the measure has ranged between .58-.81, demonstrating good to excellent agreement in past studies (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001); such information is unavailable for the current study. Interviewers in the study underwent extensive training by an expert clinician. The training process involved observation of an expert conducting an interview, then observation by an expert. Independent interviews were not conducted until there was agreement between interviewer and expert clinician (including matching diagnoses and clinician severity rating within 1 point agreement).

Obsessive Compulsive Inventory - Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002)

The OCI-R is an 18-item measure of DSM-IV symptoms of OCD. The internal consistency of the OCI-R total score was demonstrated to be high in past studies, ranging from .88-.92 (Hajcak et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2013), and the internal consistency of each of the subscales has ranged from .57-.93 in past studies (Hajcak et al., 2004; Huppert et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2013). The internal consistency in the current study is described below. The total score on the OCI-R ranges from 0-72. For this study the OCI-R was divided into two scales, items measuring the HD symptoms (OCI-HD) and items excluding the hoarding symptoms (OCI-OCD). The OCI-HD consists of three items and the total range for scores is 0-12. The OCI-OCD consists of 15 items and total scores range from 0-60.

Saving Inventory – Revised (SI-R; Frost, Steketee, & Grisham, 2004)

The SI-R is a commonly used outcome measure assessing symptoms of HD. The scale consists of 23 items, with 3 subscale scores including clutter, difficulty discarding and acquiring. The 3 factor structure has been validated in a number of studies with non-clinical (Melli, Chiorri, Smurra, & Frost, 2013; Mohammadzadeh, 2009) and clinical (Frost et al., 2004) populations. Total scores on the SI-R range from 0-92 for the total score. The internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) has been demonstrated as good, ranging from .84-.93 (Fontenelle et al., 2010; Frost, Rosenfield, Steketee, & Tolin, 2013) and the test-re-test reliability ranges from .86-.94 in previous studies (Fontenelle et al., 2010; Frost et al., 2004). The internal consistency in the current study was .98. Convergent evidence of validity has been established by the indication of high correlations between the SI-R (Frost et al., 2004) and Hoarding subscale of the OCI-R (Fontenelle et al., 2010) in past studies. Evidence of the discriminant validity of the SI-R has also been demonstrated via correlations with the Beck Depression Inventory (Fontenelle et al., 2010). A cutoff score of 41 has been deemed to provide the best relationship between sensitivity and specificity (Tolin, Meunier, Frost, & Steketee, 2011) for this measure.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990)

The BAI is a 21-item self-report measure of anxiety symptomology in the past week. Items are rated on a four-point scale from 0 = not at all to 3 = severely. The BAI has demonstrated good test-retest reliability, and good internal consistency in other studies, ranging from .85-.94 (Beck & Steer, 1990). In the current study the internal consistency in the current study was .93.

Hoarding Rating Scale – Interview (HRS-I; Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2010)

The HRS is a 5-item structured interview that assesses the core features of compulsive hoarding including the severity of clutter, difficulty discarding, acquiring, distress from symptoms and impairment from symptoms. The HRS-I has demonstrated good internal consistency (.97) and test-retest reliability in other studies, and is able to distinguish individuals with HD from controls (Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2010). The internal consistency in the current study was .97.

Statistical Methods

In the current study criterion validity was analyzed using a general linear model one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and planned contrasts using Bonferroni-corrected p-values. Convergent and discriminant validity of the measures was assessed with Pearson correlation coefficients. Significant differences between correlation coefficients were calculated using Fisher's r-to-z transformation. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha. The diagnostic sensitivity of the measures was assessed using receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis. All analyses were conducted using SPSS V21.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Demographics and comorbidity data are shown in Table 1. There was a significant difference between the groups on age (p <.001). Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests showed that the OCD group was significantly younger than the HD (p <.001) and CC groups (p <.001), which did not differ from each other. The OCD group contained more men than did the HD and CC groups (both ps <.001), which did not differ from each other.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for each group on demographic and clinical variables.

| Group | Significance statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Demographics | HD (n = 201) | OCD (n = 118) | CC (n = 155) | |

| Age | 52.32 (9.17) | 33.50 (13.20) | 51.61 (13.51) | F (2,471) =109.68, p = <.001 b, c |

| Gender (% female) | 79.6% | 39.8% | 71.0% | χ2 (2, N=474) = 54.83, p = <.001 b, c |

| Comorbid Diagnoses# | ||||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 22.4% | 12.7% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 4.56, p = .03 |

| Unipolar Depression | 58.2% | 35.6% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 15.21, p = <.001 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 1.5% | 0.0% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 1.78, p = .18˄ |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 20.9% | 20.3% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 0.01, p = .91 |

| Posttraumatic/Acute Stress Disorder | 6.0% | 2.5% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 1.95, p = .16 |

| Panic Disorder/Agoraphobia | 0.0% | 2.5% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 5.16, p = .02˄ |

| Specific Phobia | 12.4% | 8.5% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 1.20, p = .27 |

| Drug/alcohol abuse or dependence | 1.0% | 1.7% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = .29, p = .59 |

| Eating Disorder | 1.5% | 0.0% | - | χ2 (1, N=319) = 1.78, p = .18˄ |

Note.

Comparisons were made between the clinical groups only (HD Group and OCD Group).

Chi-square tests with at least one cell with a count of less than 5. These statistics should thus be interpreted with caution.

indicates significant differences between the CC and HD groups.

indicates significant differences between CC and OCD groups.

indicates differences between HD and OCD groups.

Validity

Table 2 displays the mean scores and effect sizes for each group on all outcome measures, as well as the significance statistics. A one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine whether scores on the OCI-HD and OCI-OCD differed among the groups. On the OCI-HD, the HD sample scored higher than did the other two groups (p's <.001, large effect sizes), and there was no significant difference between the CC and OCD groups (small effect size). On the OCI-OCD, the OCD group scored significantly higher than did the CC and HD groups (p's <.001, large effect sizes). The HD group also scored significantly higher than did the CC group (p <.001, large effect size).

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for each group on clinical variables.

| Group | Significance statistics | Effect size (d) (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Measure | HD | OCD | CC | CC and HD | CC and OCD | HD and OCD | |

| OCI-HD | 9.29 (2.45) | 1.89 (2.59) | 1.32 (2.16) | F (2,471) = 600.38, p = <.001 a, c | 3.42 (3.09-3.74) | 0.24 (0.00-0.48) | 2.96 (2.63-3.27) |

| OCI-OCD | 9.25 (8.28) | 23.94 (12.11) | 2.35 (3.54) | F (2,471) = 229.13, p = <.001 a, b, c | 1.04 (0.81-1.26) | 2.57 (2.24-2.89) | 1.49 (1.23-1.74) |

| SI-R Total | 63.27 (13.40) | 15.06 (14.29) | 10.50 (12.74) | F (2,458) = 806.91, p = <.001 a, b, c | 4.02 (3.65-4.38) | 0.34 (0.09-0.58) | 3.51 (3.14-3.86) |

| HRS | 25.42 (4.98) | 3.23 (4.80) | 1.89 (3.65) | F (2,464) = 1458.35, p = <.001 a, c | 5.29 (4.83-5.72) | 0.32 (0.08-0.56) | 4.52 (4.08-4.92) |

| BAI | 11.27 (9.71) | 12.65 (11.41) | 1.69 (3.58) | F (2,436) = 68.13, p = <.001 a, b | 1.26 (1.02-1.49) | 1.41 (1.13-1.68) | 0.13 (-0.11-0.37) |

Note. SI-R scores were available for 461/474 participants (97%). HRS scores were available for 467/474 participants (98%). Scores on the BAI were available for 439/474 participants (93%).

indicates significant differences between the CC and HD groups.

indicates significant differences between CC and OCD groups.

indicates differences between HD and OCD groups.

The OCI-HD correlated strongly with the SI-R (r =.94) and HRS (r =.89) and only moderately with a measure of anxiety (BAI, r =.36). In line with the recommendation of Cohen (1988), these correlations are considered large in the case of the SI-R and HRS, and medium for the BAI. Fisher's r-to-z transformation was used to compare the OCI-HD scores with measures of hoarding and measures of anxiety. Correlations between the OCI-HD with measures of hoarding were significantly higher than with the measure of anxiety (SI-R; z = -20.34, p <.001; HRS; z = -15.67, p <.001). Similarly, the OCI-OCD correlated more strongly with a measure of anxiety (BAI, r =.61, a large effect size) than with measures of hoarding (SI-R r =.06; HRS r =-.01; both small effect sizes). These correlations also differed significantly (SI-R; z = 9.70, p <.001; HRS; z = 10.78, p <.001). The two scales (OCI-HD and OCI-OCD) demonstrated a very small correlation with each other (r = .08; a small effect).

Reliability

Cronbach's alphas for both scales were high (r = .94 for the OCI-HD and r = .92 for the OCI-OCD) when all groups were combined. For the HD, OCD and CC samples separately, alpha values for the OCI-HD were .70, .87 and .89 respectively. For the OCI-OCD the values were .87, .84 and .81 respectively.

Diagnostic Sensitivity

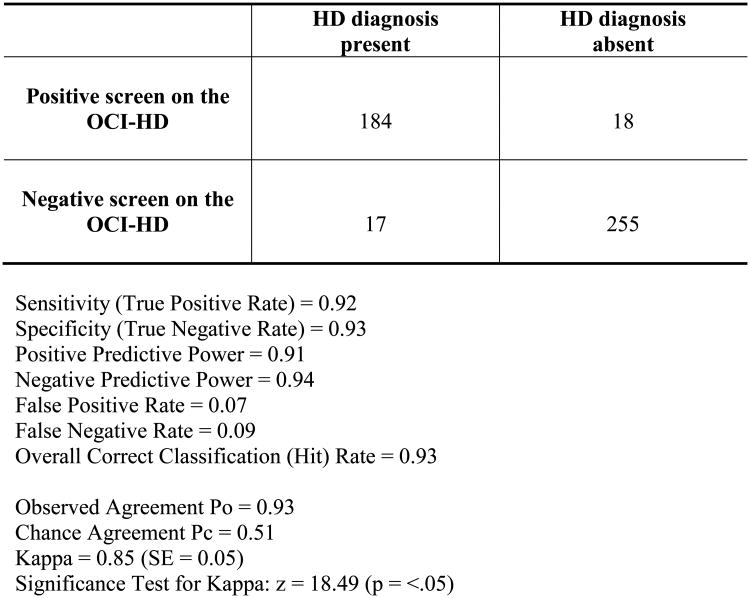

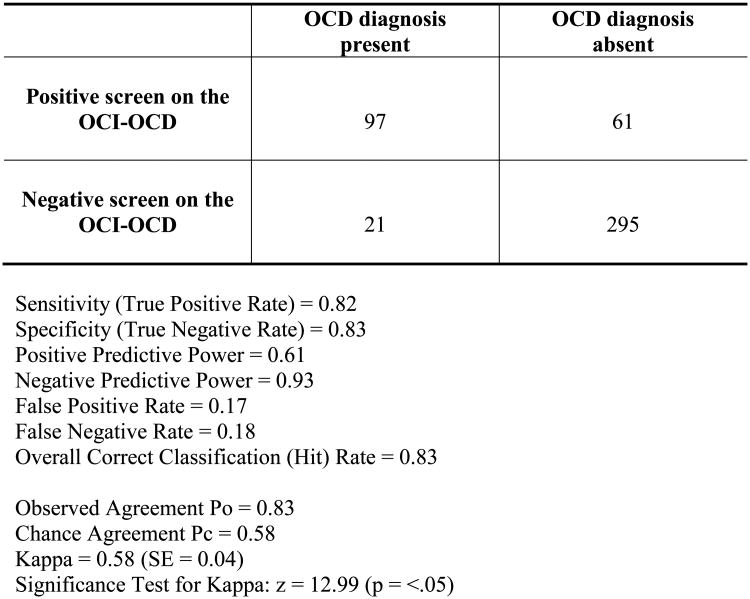

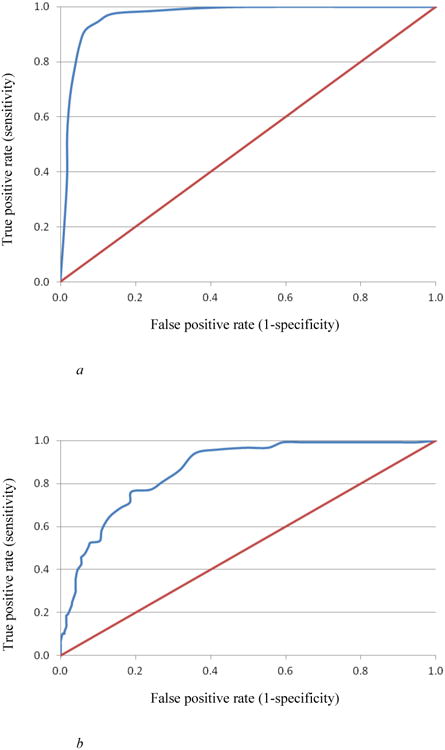

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were conducted in order to ascertain the diagnostic sensitivity (percentage of patients who were accurately identified as having the diagnosis) and specificity (percentage of patients who were accurately identified as not having the diagnosis) of the OCI-HD and OCI-OCD scales. The ROC curves can be seen in Figure 1. The objective diagnosis was based on the ADIS/HRS assessments. On the OCI-HD, the area under the curve (AUC) was .97 (95% CI: .95-.98), and as seen in Table 3, a cutoff score of 6 provided the best balance between sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity, .92; specificity, .93). The positive predictive power was .91 and the negative predictive value was .94. The false positive rate was 7% and the false negative rate was 9%. The percentage of participants who were correctly classified based on a cut score of 6 was 93%. On the OCI-OCD the AUC was .91 (95% CI: .89-.94) and as seen in Table 4, a cut score of 12 provided the best balance between sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity, .82; specificity, .83). The positive predictive power was .61 and the negative predictive power was .93. The false positive rate was 17% and the false negative rate was 18%. The percentage of participants who were correctly classified based on a cut score of 12 was 83%. In line with the recommendations of Kessel and Zimmerman (1993) the data required for assessing the diagnostic performance of each of the tests is indicated in Figure 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

a. Receiver operating characteristic curve of the OCI_HD.

b. Receiver operating characteristic curve of the OCI_OCD.

Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity of the OCI-HD.

| Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | % correctly classified |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 71.1 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 78.9 |

| 3 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 85.4 |

| 4 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 90.0 |

| 5 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 92.0 |

| 6* | 0.92 | 0.93 | 92.6 |

| 7 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 91.1 |

| 8 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 88.8 |

| 9 | 0.68 | 0.97 | 84.8 |

| 10 | 0.54 | 0.98 | 79.3 |

| 11 | 0.39 | 0.98 | 73.0 |

| 12 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 66.2 |

optimal cut score

Table 4. Sensitivity and specificity of the OCI-OCD.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | % correctly classified | Sensitivity | Specificity | % correctly classified | Sensitivity | Specificity | % correctly classified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 38.4 | 21 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 84.6 | 41 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 77.4 |

| 2 | 0.99 | 0.28 | 45.6 | 22 | 0.51 | 0.96 | 84.4 | 42 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 77.2 |

| 3 | 0.99 | 0.39 | 53.8 | 23 | 0.47 | 0.96 | 84.0 | 43 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 77.2 |

| 4 | 0.99 | 0.51 | 62.9 | 24 | 0.46 | 0.97 | 84.0 | 44 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 77.2 |

| 5 | 0.99 | 0.58 | 68.1 | 25 | 0.45 | 0.97 | 83.8 | 45 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 77.4 |

| 6 | 0.99 | 0.62 | 71.3 | 26 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 83.3 | 46 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 76.8 |

| 7 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 72.8 | 27 | 0.40 | 0.97 | 83.1 | 47 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 76.4 |

| 8 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 76.2 | 28 | 0.36 | 0.98 | 82.3 | 48 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 76.2 |

| 9 | 0.96 | 0.74 | 79.7 | 29 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 81.9 | 49 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 75.9 |

| 10 | 0.94 | 0.78 | 82.1 | 30 | 0.31 | 0.98 | 81.0 | 50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 75.5 |

| 11 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 82.1 | 31 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 80.8 | 51 | 0.11 | 0.99 | 75.5 |

| 12* | 0.82 | 0.83 | 82.7 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 80.0 | 52 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 75.5 |

| 13 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 82.9 | 33 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 79.7 | 53 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 75.3 |

| 14 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 83.5 | 34 | 0.19 | 0.99 | 79.1 | 54 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 75.3 |

| 15 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 85.4 | 35 | 0.19 | 0.99 | 79.1 | 55 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 75.3 |

| 16 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 84.4 | 36 | 0.18 | 0.99 | 78.9 | 56 | 0.04 | 1.00 | - |

| 17 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 84.8 | 37 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 78.7 | 57 | - | - | - |

| 18 | 0.64 | 0.92 | 85.0 | 38 | 0.16 | 0.99 | 78.5 | 58 | - | - | - |

| 19 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 84.6 | 39 | 0.15 | 0.99 | 78.3 | 59 | - | - | - |

| 20 | 0.53 | 0.94 | 83.8 | 40 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 77.8 | 60 | - | - | - |

Optimal cut score

Figure 2. Diagnostic performance matrix for OCI-HD (n = 474).

Figure 3. Diagnostic performance matrix for OCI-OCD (n = 474).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to assess the psychometric properties of the OCI-R according to the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, which consider HD and OCD as separate diagnoses. To achieve this aim the OCI-R was separated into two measures; the OCI-HD consisted of the 3 items measuring symptoms of hoarding, and the remaining 15 items, which investigate symptoms of OCD, constituted the OCI-OCD. Specifically, we investigated the validity, reliability and diagnostic sensitivity of each of these measures in a sample of individuals with HD, a sample of individuals with OCD, and a sample of CCs. All participants with HD were diagnosed before the publication of DSM-5 and were diagnosed based on the proposed criteria at the time, which as described above overlaps significantly with the eventual DSM-5 diagnostic criteria.

Overall the scales adequately differentiated the relevant DSM-5 diagnostic groups. We found that those in the HD group scored significantly higher than the OCD and CC on the OCI-HD and results from the current study provide important preliminary evidence to suggest that the 3-item OCI-HD scale may be sufficient to detect significant hoarding symptoms (correctly classifying 93% of this group). This finding is contradictory to other studies in the field that have failed to demonstrate criterion validity of the OCI-R hoarding subscale (Belloch et al., 2013; Solem et al., 2010). It is possible that this was due to lack of power, as it would be expected that only a small proportion (e.g., 5%; Mataix-Cols et al., 1999) of individuals with clinical hoarding symptoms would be seen in an OCD sample.

We also found that those in the OCD group scored significantly higher than the HD and CC groups on the OCI-OCD and that a cut score of 12 accurately placed 83% of the sample. There was also a significant difference between the HD and CC on the OCI-OCD, indicating that subclinical OCD symptoms may be present in those with HD. The mean score on the OCI-OCD was 9.23 (SD = 2.45) for the HD group and 57/201 (28%) of individuals in the HD group scored above our proposed clinical cutoff of 12 on the OCI-OCD. However, in this study participants who met criteria for both disorders were removed and this finding may be a feature of the significant psychopathology that is characteristic individuals with hoarding disorder more generally (Frost, Steketee, & Tolin, 2011).

Overall, results from the current study indicate that the OCI-HD can adequately differentiate between clinical OCD and HD symptoms when the study is powered to do so. Likewise, the OCI-OCD can adequately differentiate individuals with OCD from those with HD and community controls. The internal consistency was high (>.92) in the combined samples, although scores were slightly lower for each group separately. The HD group showed the lowest internal consistency for the OCI-HD, suggesting that individuals with HD may respond differentially to the items, indicating the possibility of subtypes. This is consistent with a recent study by Hall, Tolin, Frost and Steketee (2013) that identified three possible subtypes of individuals with hoarding symptoms (1) no comorbid hoarding, 2) hoarding symptoms with depression and 3) hoarding with comorbid depression and inattention. Despite the possibility of subtypes, the reliability of the OCI-HD in this group was still satisfactory (.70). The internal consistency of the OCI-HD in this sample is similar to figures cited in previous studies (e.g. Huppert et al. 2007, .93; Williams et al. 2013, .81). The internal consistency of the OCI-OCD was similar to two prior studies that investigated the psychometric properties of the 15-item OCI-R scale without the HD items (.89; Frost et al., 2013; Hall, Tolin, Frost, & Steketee, 2013). These results indicate that both the OCI-HD and OCI-OCD can be reliably used as stand-alone measures of HD and OCD symptoms respectively, however due to the lower internal consistency in the HD sample the OCI-HD may be best suited to a screening measure rather than an outcome measure.

The OCI-HD correlated highly with other measures of HD symptoms (SI-R and HRS), and results were similar to those seen in other studies (e.g., Fullana et al., 2005) demonstrating evidence of convergent validity of this brief 3-item scale with other more lengthy scales of hoarding symptoms. Therefore the OCI-HD may be a beneficial brief screening tool. The OCI-OCD correlated moderately with a measure of anxiety (the BAI), a higher correlation than found in studies that have examined correlations between these measures in the past (Sica et al., 2009; Solem et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2013). However, measures of OCD symptoms were unavailable in this study and an investigation of the convergent validity of the OCI-OCD with OCD symptom measures deserve further attention in the future. Additionally, the two scales showed a low correlation (r = .08, small effect size) with each other, suggesting that the scales are most likely measuring different constructs.

The results of the ROC analyses indicate that an appropriate cut off score on the OCI-HD is 6 and on the OCI-OCD, 12, for purposes of using the OCI-R as a screening measure for HD and OCD symptoms. Using this cut off score, approximately 93% of individuals with HD and 83% of individuals with OCD were appropriately classified. This has important implications for clinicians who may wish to use the brief OCI-R as a screening tool for individuals with HD and OCD, and also for OCD researchers who may wish to re-analyze data excluding individuals who would likely have met current criteria for HD. From a research perspective, inconsistent findings in the OCD literature may have resulted from significant symptom heterogeneity in OCD samples (McKay et al., 2004). Removal of individuals who report significant symptoms of hoarding (and may have a primary diagnosis of hoarding disorder) may assist in reducing some of the inconsistency in this literature.

While this study has important implications for the use of the OCI-R in OCD and HD research, there are a number of notable limitations to this study. First, the individuals in the HD group were not diagnosed according to DSM-5 criteria, although it is noteworthy that the criteria used to diagnose this group are very similar to the current DSM-5 criteria. Additionally, we were unable to calculate the inter-rater reliability for the diagnosis, a limitation that should be addressed in future research. Second, the convergent validity of the OCI-OCD evident in correlations with existing OCD measures could not be assessed in this study. Future studies might replicate these findings using a structured diagnostic questionnaire that assesses both symptoms of DSM-5 OCD and HD such as the Diagnostic Interview of Anxiety, Mood, Obsessive-Compulsive and Neurodevelopmental Disorders (DIAMOND) (Tolin et al., 2013), as well as other measures to adequately address the convergent and discriminant validity of the OCI-OCD such as the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Goodman et al., 1989) or the Dimensional Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Abramowitz et al., 2010).

In summary, DSM-5 has brought considerable changes to the diagnosis of OCD that require modification to common self-report measures of OCD symptoms. The OCI-R is a reliable, well validated and widely used measure of DSM-IV symptoms of OCD. The results of the current study demonstrate the psychometric properties and diagnostic sensitivity of the hoarding subscale of the OCI-R (OCI-HD) and the remaining 15 items that measure symptoms of OCD (OCI-OCD). The results of this study highlight the potential of the OCI-R as a screening measure for individuals with OCD and HD and demonstrate the utility of separate clinical cut offs for assessing likely diagnosis of both HD and OCD.

Footnotes

All authors contributed to this study and meet requirements for authorship.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, Olatunji BO, Wheaton MG, Berman NC, Losardo D, et al. Hale LR. Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: Development and evaluation of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22(1):180–198. doi: 10.1037/a0018260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz JS, Taylor S, McKay D. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Lancet. 2009;374(9688):491–499. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ. Psychometric properties and construct validity of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised: Replication and extension with a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(8):1016–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz JS, Tolin DF, Diefenbach GJ. Measuring change in OCD: Sensitivity of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2005;27(4):317–325. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E, Enander J, Andrén P, Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Hursti T, et al. Rück C. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(10):2193–2203. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Belloch A, Roncero M, García-Soriano G, Carrió C, Cabedo E, Fernández-Álvarez H. The Spanish version of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R): Reliability, validity, diagnostic accuracy, and sensitivity to treatment effects in clinical samples. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2013;2(3):249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chasson GS, Tang S, Gray B, Sun H, Wang J. Further validation of a chinese version of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised. Behavioural and cognitive psychotherapy. 2013;41(2):249–254. doi: 10.1017/S1352465812000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, Salkovskis PM. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14(4):485–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ, Goodman WK, Hollander E, Jenike MA, Rasmussen SA. DSM-IV field trial: Obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American journal of psychiatry. 1995;152(1):90–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenelle IS, Prazeres AM, Rang EB, Versiani M, Borges MC, Fontenelle LF. The Brazilian Portuguese version of the Saving Inventory-Revised: Internal consistency, test-retest, reliability, and validity of a questionnaire to assess hoarding. Psychological Reports. 2010;106(1):279–296. doi: 10.2466/PR0.106.1.279-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Rosenfield E, Steketee G, Tolin DF. An examination of excessive acquisition in hoarding disorder. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2013;2(3):338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: Saving Inventory-Revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(10):1163–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RO, Steketee G, Tolin DF. Comorbidity in hoarding disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(10):876–884. doi: 10.1002/da.20861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana MA, Tortella-Feliu M, Caseras X, Andión Ó, Torrubia R, Mataix-Cols D. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory—Revised in a non-clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19(8):893–903. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönner S, Leonhart R, Ecker W. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R): Validation of the German version in a sample of patients with OCD, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(4):734–749. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Huppert JD, Simons RF, Foa EB. Psychometric properties of the OCI-R in a college sample. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2004;42(1):115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BJ, Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An exploration of comorbid symptoms and clinical correlates of clinically significant hoarding symptoms. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(1):67–76. doi: 10.1002/da.22015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert JD, Walther MR, Hajcak G, Yadin E, Foa EB, Simpson HB, Liebowitz MR. The OCI-R: Validation of the subscales in a clinical sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21(3):394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jónsson H, Hougaard E, Bennedsen BE. Randomized comparative study of group versus individual cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;123(5):387–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel JB, Zimmerman M. Reporting errors in studies of the diagnostic performance of self-administered questionnaires: Extent of the problem, recommendations for standardized presentation of results, and implications for the peer review process. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(4):395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Frost RO, Pertusa A, Clark LA, Saxena S, Leckman JF, et al. Wilhelm S. Hoarding disorder: A new diagnosis for DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(6):556–572. doi: 10.1002/da.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Pertusa A, Leckman JF. Issues for DSM-V: How should obsessive-compulsive and related disorders be classified? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(9):1313–1314. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, Kobak KA, Baer L. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: Results from a controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2002;71(5):255–262. doi: 10.1159/000064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Manzo PA, Jenike MA, Baer L. Use of factor-analyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(9):1409–1416. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay D, Abramowitz JS, Calamari JE, Kyrios M, Radomsky A, Sookman D, et al. Wilhelm S. A critical evaluation of obsessive–compulsive disorder subtypes: Symptoms versus mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:283–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melli G, Chiorri C, Smurra R, Frost RO. Psychometric properties of the paper-and-pencil and online versions of the Italian Saving Inventory-Revised in nonclinical samples. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2013;6(1):40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh A. Validation of Saving Inventory-Revised (SI-R): Compulsive hoarding measure. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2009;1(56):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Monzani B, Rijsdijk F, Harris J, Mataix-Cols D. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for dimensional representations of DSM-5 obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):182–189. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica C, Ghisi M, Altoè G, Chiri LR, Franceschini S, Coradeschi D, Melli G. The Italian version of the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory: Its psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23(2):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Ledley DR, Huppert JD, Cahill S, et al. Petkova E. A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for augmenting pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(5):621–630. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solem S, Hjemdal O, Vogel PA, Stiles TC. A Norwegian version of the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory–Revised: Psychometric properties. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2010;51(6):509–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. A brief interview for assessing compulsive hoarding: the Hoarding Rating Scale-Interview. Psychiatry Research. 2010;178(1):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.001. doi:S0165-1781(09)00178-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Meunier SA, Frost RO, Steketee G. Hoarding among patients seeking treatment for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, Norberg MM, Calhoun VD, Frost RO, et al. Pearlson GD. Neural mechanisms of decision making in hoarding disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832–841. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Witt ST, Stevens MC. Hoarding disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder show different patterns of neural activity during response inhibition. Psychiatry Research - Neuroimaging. 2014;221(2):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Wootton BM, Bowe W, Bragdon LB, Davis EC, Gilliam CM, et al. Worden B. Diagnostic Interview for Anxiety, Mood, and OCD and Related Disorders (DIAMOND) Hartford, CT: Institute of Living/Hartford HealthCare Corporation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Davis DM, Thibodeau MA, Bach N. Psychometric properties of the obsessive-compulsive inventory revised in african americans with and without obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2013;2(4):399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton BM, Titov N, Dear BF, Spence J, Andrews G, Johnston L, Solley K. An Internet administered treatment program for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A feasibility study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25(8):1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]