Dear Editor:

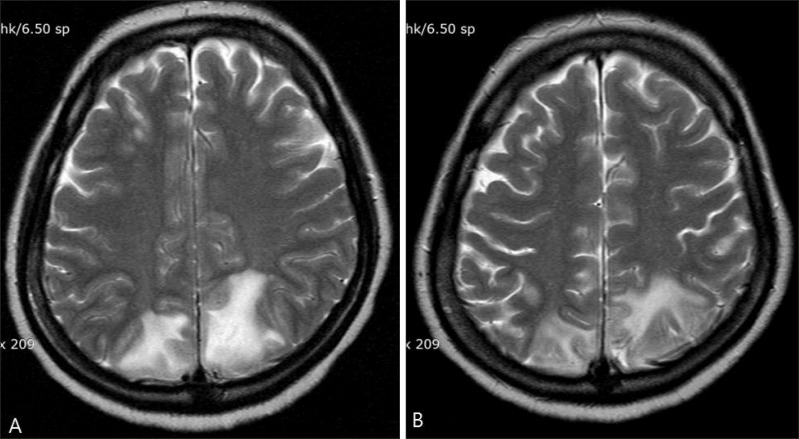

Cyclosporine is an immunosuppressive drug originally isolated from Tolypocladium inflatum in 19701. Here, we report a case of cyclosporine-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris. A 41-year-old Korean woman who had no underlying disease except pemphigus vulgaris was admitted to the emergency room owing to a sudden onset of severe headache, nausea, vomiting, and vision loss. A few minutes after admission, she presented with generalized tonic-clonic convulsive movement and became confused. Transient hypertension (160/100 mmHg) accompanied the episode. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis (17.9×109/L) with neutrophilia (92.2%); cerebrospinal fluid was normal. Multiple ill-defined high-signal enhanced lesions were visible in the cortex and subcortical white matter of the bilateral parieto-occipital lesion on a T2-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1A). Six months earlier, the patient presented with highly crusted vegetating lesions on her lower lip (Fig. 2A) as well as several flaccid blisters and scaly crusted erosions on her trunk (Fig. 2B). Histopathological examination showed suprabasal acantholysis (Fig. 2C), and a direct immunofluorescence study on the perilesional dorsal skin showed intercellular epidermal IgG deposition (Fig. 2D). Therefore, she was diagnosed with pemphigus vulgaris. Initially, the patient received prednisolone 100 mg/day for 2 weeks and tapered for 4 months; this was followed by cyclosporine 200 mg/day (4 mg/kg) for 2 months. We considered acute hypertension and cyclosporine administration as possible causes of the convulsive encephalopathy. Cyclosporine was discontinued immediately, and conservative therapy was administered. The patient showed a complete clinical recovery in 6 weeks, and signal enhancement also decreased on follow-up brain MRI (Fig. 1B). Cyclosporine is rarely reported to cause PRES; its association with cyclosporine was first described by Adams et al.2 in 1987. PRES is characterized by clinical symptoms including headache, mental confusion, vomiting, visual disturbance, and multiple generalized tonic-clonic seizures; it is associated with characteristic radiological abnormalities in the posterior area of the cerebral white matter3. In addition to immunosuppressive or cytotoxic drugs, reported causes of PRES also include acute hypertension, infection, autoimmune disease, eclampsia, and pre-eclampsia3. Although the pathophysiology of PRES remains unclear, several mechanisms have been proposed. Cyclosporine has a direct toxic effect on vascular endothelial cells, causing them to release endothelin, prostacyclin, and thromboxane; these may cause microthrombi and also damage the blood-brain barrier3. Many PRES cases have been reported in organ and bone marrow transplant recipients receiving high-dose cyclosporine4. However, in the present case, the patient had been taking low-dose cyclosporine 4 mg·kg-1·day-1 and had no associated risk factors for neurotoxicity. We finally diagnosed the patient with PRES because of her favorable response to cyclosporine discontinuation and the ultimately near-full reversal of encephalopathy. Thus, the possibility of PRES in patients taking even low-dose cyclosporine who present with neurologic symptoms should be emphasized. Physicians should rapidly diagnose this disease and withdraw the causative drug(s), because delayed diagnosis could lead to permanent sequelae.

Fig. 1. (A) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing an area of high signal intensity in the bilateral white matter of the posterior parieto-occipital area. (B) Six weeks later, axial T2-weighted MRI showing significant improvement after cyclosporine withdrawal.

Fig. 2. (A) Highly crusted vegetating lesions on the lower lip. (B) Several flaccid blisters and scaly crusted erosions are distributed on her trunk. (C) Separation of the epidermis above the basal layer and scattered acantholytic cells (H&E, ×200). (D) Direct immunofluorescence study of the perilesional skin shows intercellular deposition of immunoglobulin G (×100).

References

- 1.Amor KT, Ryan C, Menter A. The use of cyclosporine in dermatology: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:925–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams DH, Ponsford S, Gunson B, Boon A, Honigsberger L, Williams A, et al. Neurological complications following liver transplantation. Lancet. 1987;1:949–951. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, et al. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602223340803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belli LS, De Carlis L, Romani F, Rondinara GF, Rimoldi P, Alberti A, et al. Dysarthria and cerebellar ataxia: late occurrence of severe neurotoxicity in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Int. 1993;6:176–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00336365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]