Abstract

Hyaluronan (HA) is an extracellular matrix (ECM) component that is present in mouse and human islet ECM. HA is localized in peri-islet and intra-islet regions adjacent to microvessels. HA normally exists in a high molecular weight form, which is anti-inflammatory. However, under inflammatory conditions, HA is degraded into fragments that are proinflammatory. HA accumulates in islets of human subjects with recent onset type 1 diabetes (T1D), and is associated with myeloid and lymphocytic islet infiltration, suggesting a possible role for HA in insulitis. A similar accumulation of HA, in amount and location, occurs in non-obese diabetic (NOD) and DORmO mouse models of T1D. Furthermore, HA accumulates in follicular germinal centers and in T-cell areas in lymph nodes and spleen in both human and mouse models of T1D, as compared with control tissues. Whether HA accumulates in islets in type 2 diabetes (T2D) or models thereof has not been previously described. Here we show evidence that HA accumulates in a mouse model of islet amyloid deposition, a well-known component of islet pathology in T2D. In summary, islet HA accumulation is a feature of both T1D and a model of T2D, and may represent a novel inflammatory mediator of islet pathology.

Keywords: diabetes, extracellular matrix, islet, hyaluronan, hyaladherins

Introduction

Extracellular Matrix in the Islet

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a ubiquitous, non-cellular component of tissues. It consists of a complex array of structural proteins, entangled, cross-linked and associated with other ECM components, growth factors, chemokines and cytokines, which together provide a rich signaling environment (Hynes 2009). Each tissue has its own ECM “signature”, which provides specific phenotypic cues. For example, anchoring of epithelial cells to their native ECM conveys survival signals and maintains homeostasis (Meredith et al. 1993; Grossmann 2002). Conversely, alterations in ECM composition and/or integrity occur during disease pathogenesis. Several studies show that detachment of cells from their native ECM or the exposure of cells to a non-native ECM both result in a specific form of apoptosis, “ankoisis” (Frisch and Screaton 2001). Thus, the ECM is critical for maintaining normal tissue structure and also interacts with cells in those tissues to regulate cell phenotype and survival.

Over the past 10 years, our understanding of islet ECM composition has made significant strides. It is now well-established that both human and rodent islet ECMs contain classical basement membrane components including non-fibrillar collagens, laminins, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and hyaluronan (HA) (Jiang et al. 2002; Hughes et al. 2006; Nikolova et al. 2006; Irving-Rodgers et al. 2008; Otonkoski et al. 2008; Virtanen et al. 2008; Korpos et al. 2013; Bogdani et al. 2014a). Some investigators have subdivided islet ECM into two different entities: “peri-islet” or “intra-islet”, which are associated with the blood vessels that surround the islet (e.g., post-capillary venules) or that penetrate the islet core, respectively (Bogdani et al. 2014b). Peri- and intra-islet ECMs are also intimately associated with the autonomic nerve fibers that follow the islet vasculature (Mei et al. 2002; Rodriguez-Diaz et al. 2011). Peri- and intra-islet ECMs both contain the same basement membrane components in mouse and human islets (Jiang et al. 2002; Irving-Rodgers et al. 2008; Otonkoski et al. 2008; Virtanen et al. 2008; Korpos et al. 2013), aside from the reported lack of the laminin-411/421 isoform(s) in human peri-islet ECM (Virtanen et al. 2008). Additionally, the peri-islet ECM is surrounded by a thin layer of interstitial matrix, comprising distinct ECM molecules including the fibrillar type I and type III collagens, type VI collagen, and fibronectin (Van Deijnen et al. 1994; Hughes et al. 2006; Korpos et al. 2013). Whether this interstitial matrix has a biological impact on the pancreatic islet has not been investigated.

Most endocrine cells are thought to contact islet capillaries and, therefore, the associated ECM (Kragl and Lammert 2010), making the ECM an important entity from which endocrine cells receive signals. Indeed, exposing islets and/or β cells to tumor-derived ECM or individual ECM components has been shown to improve β-cell survival (Hamamoto et al. 2003; Hammar et al. 2004; Hammar et al. 2005; Saleem et al. 2009) and increase insulin gene transcription and/or insulin content (Muschel et al. 1986; Nikolova et al. 2006; Saleem et al. 2009; Daoud et al. 2011); although some studies have found no such effect (Hammar et al. 2005; Kaido et al. 2006). Additionally, many studies have shown that these ECM components increase insulin release (Bosco et al. 2000; Nagata et al. 2001; Hamamoto et al. 2003; Hammar et al. 2005; Parnaud et al. 2006; Weber and Anseth 2008; Rondas et al. 2012), whereas other studies have shown no change (Daoud et al. 2011) or decreases in insulin release (Nagata et al. 2001; Navarro-Alvarez et al. 2008; Daoud et al. 2011). ECM signals are, at least in part, transmitted into the β cell via the action of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Rondas et al. 2012). Mice with β-cell FAK deletion show impaired β-cell function (Cai et al. 2012). FAK activation (phosphorylation) results in actin cytoskeleton remodeling, and activates Ras/Raf1/extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling, thereby promoting insulin gene transcription and the proliferation and survival of β cells. These findings suggest that specific ECM components help support normal β-cell function and viability.

One islet ECM component that we have become interested in is HA (Bollyky et al. 2012; Hull et al. 2012; Bogdani et al. 2014a; Bogdani et al. 2014b). A previous study showed that HA is beneficial for insulin release from immortalized β cells (Li et al. 2006), suggesting that, under normal conditions, HA acts similarly to other islet ECM components to support normal β-cell function and health. HA is a large (>500 kDa) glycosaminoglycan composed of repeating disaccharides of N-acetyl glucosamine and glucuronic acid. HA is a ubiquitous ECM component that has been implicated in angiogenesis, cell motility, wound healing, cell adhesion, proliferation, and inflammation (Toole et al. 2002; Jiang et al. 2011). Under normal circumstances, HA exists in a high molecular weight form (>500 kDa), and can exhibit anti-inflammatory properties through interacting with CD44 to provide tissue integrity cues and anti-inflammatory signals (Turley et al. 2002; Jiang et al. 2011). Conversely, in inflammation and disease, HA is degraded to lower molecular weight fragments as a result of hyaluronidase enzyme activity (Chajara et al. 2000; Stern et al. 2006) or in response to mechanical or oxidative stress (Jiang et al. 2011). These lower molecular weight forms of HA activate toll-like receptors 2 and 4, triggering NFκB signaling and resulting in cytokine and chemokine production that promote an inflammatory response (Powell and Horton 2005; Jiang et al. 2011).

The stability and biological function of HA, both in health and disease, is modulated by its interactions with a large number of proteins (hyaladherins) (Toole 1990). These include the large aggregating family of proteoglycans such as versican (Wight et al. 2014) and link protein (Neame and Barry 1993), along with tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6) and inter-α-trypsin inhibitor (IαI) (Zhao et al. 1995; Evanko et al. 1999; Day and de la Motte 2005; Baranova et al. 2011).

Hyaluronan in the Islet

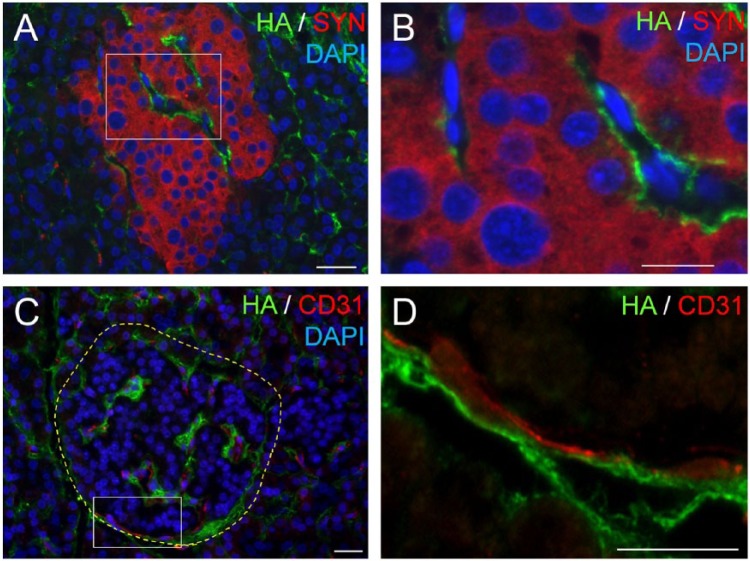

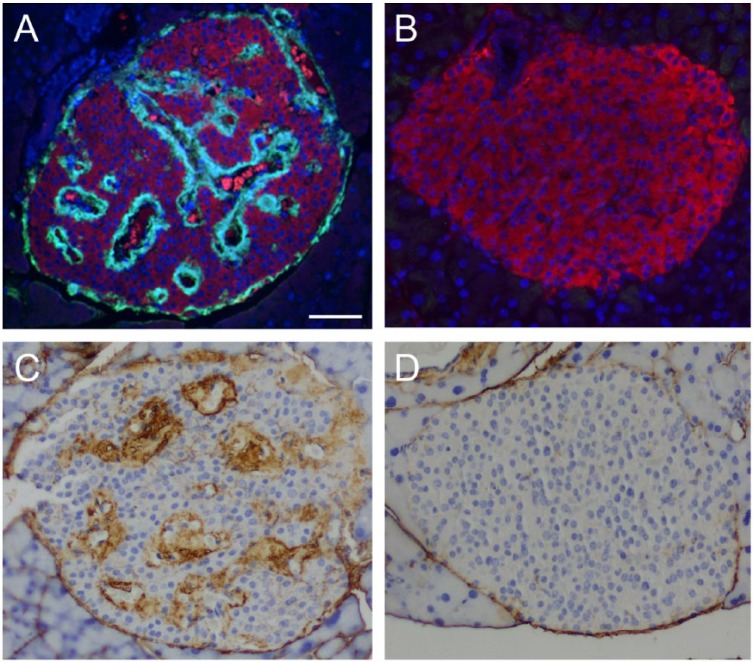

In mouse islets, HA is predominantly present in peri-islet ECM but is also detectable in intra-islet ECM (Fig. 1A). In human islets, HA distribution is somewhat similar to that observed in mouse islets, being present in peri-islet ECM mostly in a discontinuous pattern, and also occurring in intra-islet ECM (Figs. 1B, 2A, 2B) (Bogdani et al. 2014a). HA is extracellular, located outside islet endocrine cells along the peri- and intra-islet microvessels (Fig. 2C, 2D). We have demonstrated that the HA synthetic enzymes HA synthase 1 (HAS1) and HAS3, but not HAS2, are expressed in normal mouse islets (Hull et al. 2012).

Figure 1.

Hyaluronan (HA) localization in mouse (A) and human (B) pancreatic islets. White and yellow arrowheads point to peri- and intra- islet microvessels, respectively. Scale, 50 µm. Panel A is adapted from (Hull et al. 2012) and used with permission.

Figure 2.

Hyaluronan (HA) locates extracellularly, juxtaposed to the human islet microvessels. (A) Co-labeling of HA (green) with the pan-endocrine marker synaptophysin (red) shows HA outside the endocrine cells. (B) Higher magnification of the boxed area in (A). (C) Co-labeling of HA (green) with the endothelial cell marker CD31 (red) reveals HA juxtaposed to the islet microvessels. (D) Higher magnification of the boxed area in (C). Scale (A, C) 50 µm; (B, D) 10 µm. Adapted from (Bogdani et al. 2014b) and used with permission.

As described above, HA normally exists in a complex arrangement with multiple hyaladherins. Several hyaladherins are present and expressed in normal mouse islets (Hull et al. 2012). Interestingly, we observed that different endocrine cell populations contribute these various HA-binding proteins. Namely, components of IαI are produced in α, β, and δ cells, whereas TSG-6 is produced by α and β cells. In contrast, versican, a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan/hyaladherin, is restricted to glucagon-producing α cells. These findings suggest that endocrine cells synthesize distinct repertoires of ECM molecules, which likely impart local nuances to islet ECM composition and may influence endocrine cell function and viability. This is an extremely understudied area, and the focus of future work.

Islet Hyaluronan in Type 1 Diabetes

T1D is characterized by the progressive immune and inflammatory cell-mediated destruction of pancreatic β cells (Atkinson and Gianani 2009; Eizirik et al. 2009). Although the triggering mechanism(s) for T1D is not clear, T-cells, and potentially myeloid cells, must interact with the islet ECM as they migrate from the blood stream into pancreatic islets during islet destruction. Disintegration of the islet ECM has been suggested as an early event in the progression to destructive insulitis in mouse models of T1D (Irving-Rodgers et al. 2008; Korpos et al. 2013), with the loss of integrity in peri-islet ECM also being described in human T1D islets (Korpos et al. 2013).

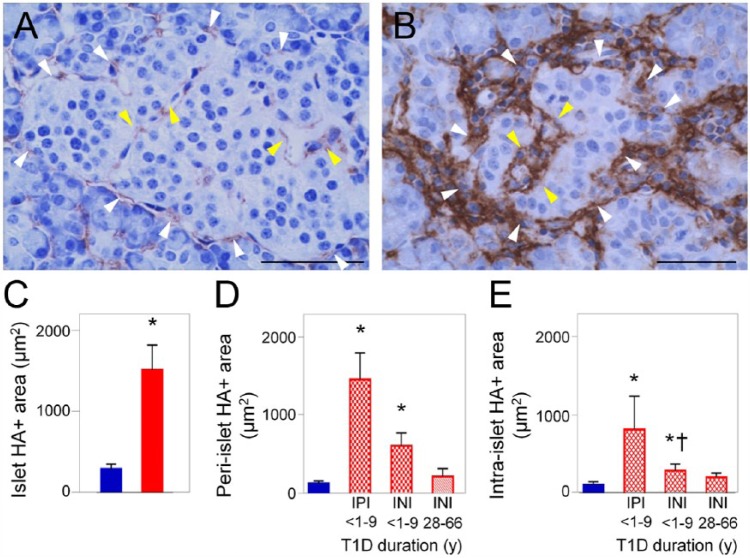

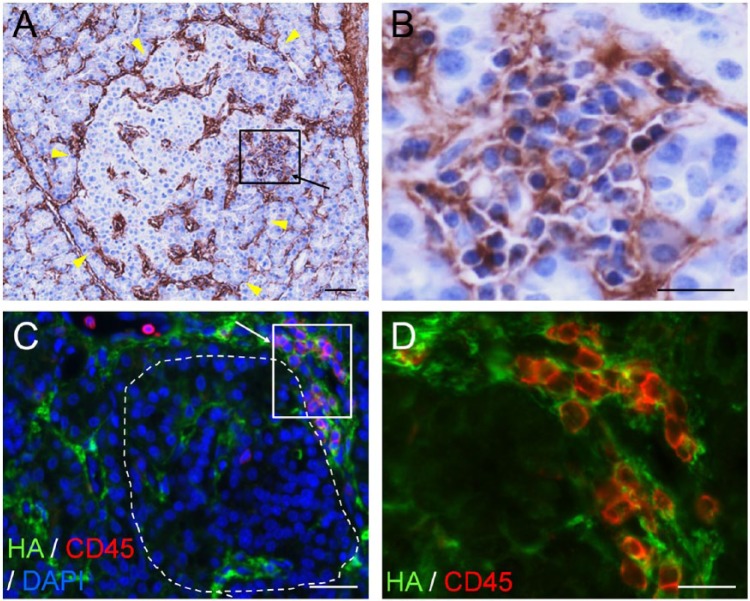

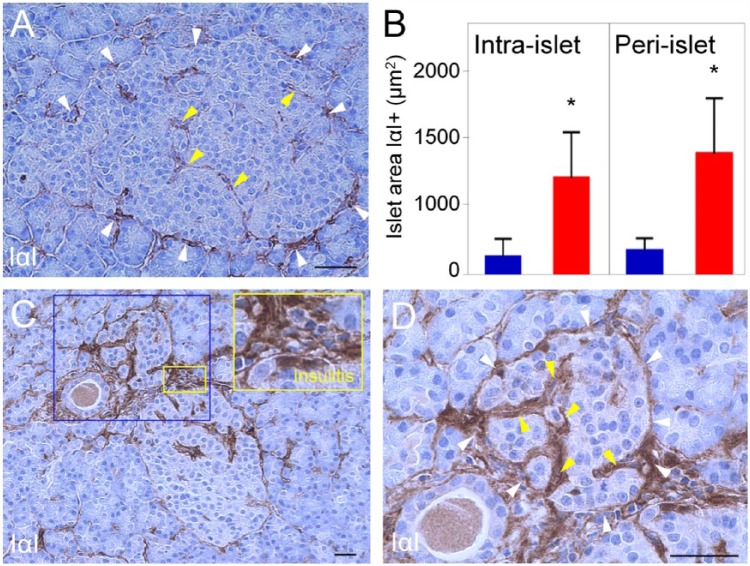

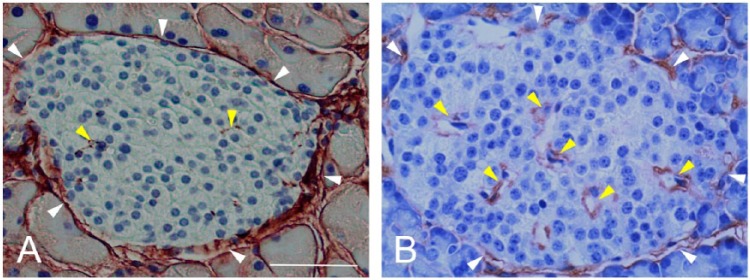

Substantial accumulation of HA occurs in islets from T1D subjects (Bogdani et al. 2014a) (Fig. 3B, 3C) as compared with those from control samples (Figs. 1B, 2, 3A). Accumulation of HA has been shown to occur in both peri-islet ECM (Fig. 3B, white arrowheads; Fig. 3D) and intra-islet ECM (Fig. 3B, yellow arrowheads; Fig. 3E). HA is most abundant in islets that contain residual insulin immunoreactivity and in subjects with relatively short duration of disease, particularly those within one year of diagnosis (Fig. 3D and 3E), suggesting that islet HA may accumulate preferentially during the period of active β-cell loss. In addition, HA accumulates in sites of islet inflammation (Fig. 4A, 4B), with clusters of CD45+ leukocytes either at the islet periphery or infiltrating the islets, surrounded by a meshwork of HA (Fig. 4C, 4D). This HA-rich ECM meshwork also contains the hyaladherins, versican (Bogdani et al. 2014a) and, most notably, IαI (Fig. 5). IαI also accumulates in HA-rich islet areas in peri- and intra-islet ECM in T1D (Fig. 5), and is present around inflammatory cell infiltrates. Taken together, these observations indicate that HA and hyaladherins accumulate in human T1D islets, and that these molecules closely associate with the inflammatory cell infiltrates in human insulitis.

Figure 3.

Hyaluronan (HA) accumulates along the microvasculature of human islets in type 1 diabetes (T1D). (A) Histochemistry shows HA (brown) juxtaposed to peri- and intra- islet microvessels in the normal human pancreas. (B) Image of a human diabetic islet. Histochemistry shows abundant HA (brown) located around and within the islet. White and yellow arrowheads point to peri- and intra-islet microvessels, respectively. Scale (A) 50 µm; (B) 10 µm. (C–E) Morphometric quantitation of HA-positive areas in pancreatic islets of normal and T1D donors. Blue bars, normal tissues; red bars, diabetic tissues; IPI, insulin-positive islet; INI, insulin-negative islet. *p<0.0001 vs normal islets. y, years. Adapted from (Bogdani et al. 2014b) and used with permission.

Figure 4.

Hyaluronan (HA) accumulates in insulitis in human type 1 diabetes (T1D). (A–D) Images of two diabetic islets with insulitis. Arrows denoting boxed areas in (A) and (C) point to areas of insulitis. (A) Histochemistry reveals HA (brown) in the islet and insulitis area. Arrowheads point to the islet border. (B) Higher magnification of the boxed area in (A). (C) Co-labeling of HA (green) with the leukocyte common antigen CD45 (red) confirms the presence of HA at sites of inflammatory cell infiltration. The islet is delineated with a dashed line. (D). Higher magnification of the boxed area in (C). Scale, (A, C) 50 µm; (B, D) 25 µm. Adapted from (Bogdani et al. 2014b) and used with permission.

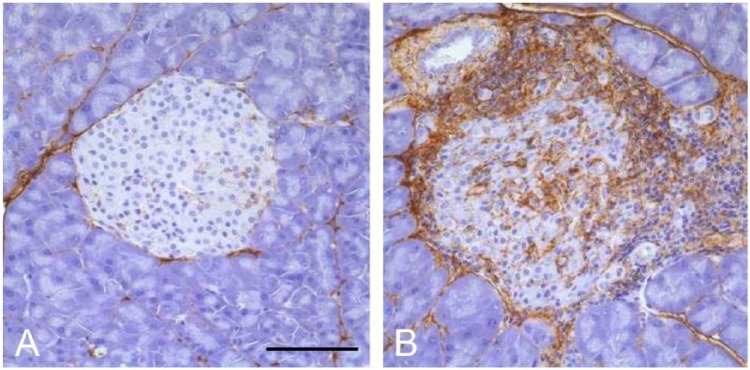

Figure 5.

Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor (IαI) accumulates in pancreatic islets and sites of insulitis in human type 1 diabetes (T1D). IαI immunohistochemistry of normal (A) and diabetic (C) islets. White and yellow arrowheads point to peri- and intra-islet microvessels, respectively. (B) The bar graph indicates larger IαI-positive areas in islets of T1D patients. Blue bar, normal controls; red bar, diabetic tissues. *p<0.0001 vs. normal islets. (D) Higher magnification of the tissue area within the blue box in (C). Scale, 50 µm.

We have also examined whether changes in islet HA occur in two mouse models of T1D: the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse and the DORmO mouse. The NOD mouse is an inbred strain, which develops spontaneous autoimmune diabetes as a result of leukocyte infiltration of the pancreatic islets (Makino et al. 1980). Spontaneous diabetes development occurs in 60% to 80% of females and 20% to 30% of males. The age of onset is somewhat variable and is gender-dependent, with disease onset being delayed in male mice. The DORmO model of T1D is a newer and more predictable model (Wesley et al. 2010). It is generated by cross-breeding two transgenic mouse strains. DO11.10 mice have a T-cell receptor transgene that is specific for ovalbumin (OVA), whereas the RIPmOVA mice express membrane-bound OVA under the control of the insulin promoter on pancreatic β cells. When these mice are cross-bred, the resulting double-transgenic offspring (DO11.10xRIPmOVA; DORmO) spontaneously develop autoimmune insulitis starting as early as 4 weeks of age, and nearly all animals become diabetic by 20 weeks of age.

HA accumulation occurs in islets from NOD mice at around 11–16 weeks of age, after induction of diabetes by splenocyte transplant from diabetic donors (Weiss et al. 2000). Our recent studies now show that significant HA accumulation occurs in islets from NOD mice (without transplant) as young as 4 weeks of age (typical age of insulitis onset; Fig. 6). For both mouse models, we find that HA in the control animals is present in the peri-islet ECM and weakly associated with intra-islet capillaries (Figs. 6A and 7A) similar to our previous findings (Fig. 1) (Hull et al. 2012). In contrast, in diabetic NOD and DORmO mice, substantial accumulation of HA occurs in peri-islet ECM as well as in intra-islet ECM (Figs. 6B and 7B). However, the most striking finding is the extensive accumulation of HA at sites of insulitis in both mouse models. Large deposits of HA are detectable in association with clusters of inflammatory cells both surrounding islets and at sites of invasive insulitis. These inflammatory cells appear to be completely surrounded by HA (Figs. 6B and 7B).

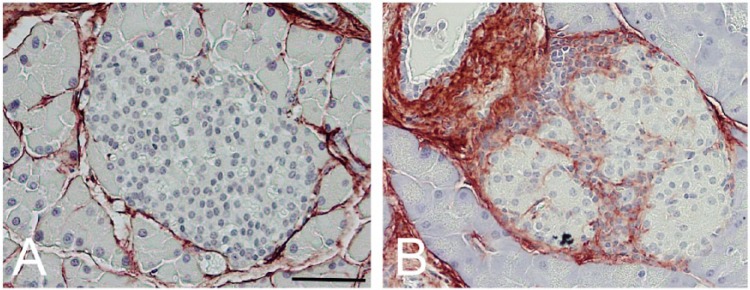

Figure 6.

Hyaluronan (HA) accumulates in diabetic non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse pancreatic islets. Representative images of pancreatic islets from control (Balb/c) mice (A) and NOD mice at 4 weeks of age (B) stained for HA (brown). Scale, 50 µm. Adapted from (Bollyky et al. 2012) and used with permission.

Figure 7.

Hyaluronan (HA) accumulates in islets from diabetic DORmO mice. Representative images of pancreatic islets from control (Balb/c) mice (A) and DORmO mice (B) at 15 weeks of age, stained for HA (brown). Scale, 100 µm.

Although the significance of islet HA/hyaladherin accumulation in T1D needs further investigation, several possible roles for these molecules in the regulation of insulitis can be anticipated. HA regulates major steps in the process of inflammation such as increased vascular permeability and inflammatory cell infiltration (de la Motte 2011; Jiang et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2011). In response to inflammatory mediators, tissue-resident cells generate a pro-inflammatory, HA-rich ECM that enhances myeloid and lymphoid cell accumulation during inflammation (Lesley et al. 2004; Day and de la Motte 2005; Potter-Perigo et al. 2010; de la Motte 2011; Bollyky et al. 2012; Evanko et al. 2012; Baranova et al. 2013). Activated macrophages also secrete HA and hyaladherins, such as TSG-6 and versican (Chang et al. 2012; Chang et al. 2014). The resulting HA–hyaladherin macromolecular complexes interact with a variety of cell-surface proteins, growth factors, chemokines, and proteases to modulate the adhesive properties and activation state of inflammatory cells (Wight and Evanko 2002; Day and de la Motte 2005; de la Motte 2011; Wang et al. 2011; Wight et al. 2014). The hyaladherin IαI specifically associates with HA to create structures that bind to and enhance the adhesiveness of leukocytes in inflamed tissues (de la Motte et al. 2003). Also, the association of HA with serum-derived HA-associated protein (SHAP; which is identical to the heavy chain subunits of IαI) occurs on the surface of inflamed endothelial cells during inflammation and supports leukocyte adhesion and rolling (Zhuo et al. 2006). It is thus conceivable that the HA/IαI-rich matrix generated at sites of insulitis in T1D may be a major regulator of immune cell adhesion and migration. It has recently been suggested that another hyaladherin, TSG-6, has immunomodulatory properties. TSG-6 administration to NOD mice enhances the generation of regulatory T cells, inhibits the activation of both antigen-presenting cells and T cells, and prevents the progression of destructive insulitis (Kota et al. 2013).

In addition, a resistance to diabetes is induced in the NOD mouse by the systemic blockade of the HA receptor, CD44, or after administration of the HA-degrading enzyme, hyaluronidase (Weiss et al. 2000). Although these latter findings suggest a role for HA in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diabetes, the systemic nature of the interventions do not allow a role for islet HA in particular to be implicated.

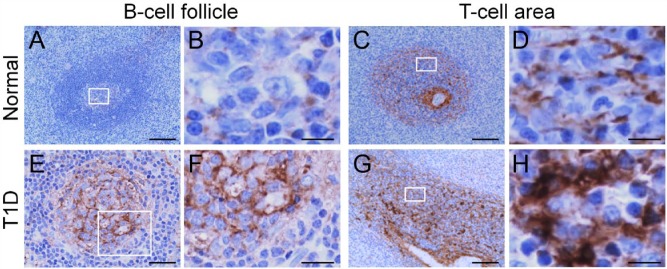

It is of interest that HA accumulation is indeed not limited to islets in T1D. HA accumulation also occurs in lymph nodes and spleens in both human (Bogdani et al. 2014b) and mouse models of T1D (unpublished observation). In normal human pancreatic lymph node and spleen tissues, sparse HA staining is seen in B-cell follicular germinal centers (Fig. 8A and 8B), and in reticular networks along niches of immune cells in the T-cell compartment (Fig. 8C and 8D). In T1D, prominent changes in the HA-rich ECM occur in specific regions of B- and T-cell activation. Specifically, HA is abundant in the B-cell follicular germinal centers in T1D, which show an intense punctate HA staining that is distributed over the germinal center areas (Fig. 8E and 8F). Prominent accumulations of HA also occur in the T-cell compartment, where HA deposits form large, amorphous aggregates along the reticular network, which appear enlarged and thickened (Fig. 8G and 8H).

Figure 8.

Altered hyaluronan (HA) distribution in lymphoid tissues in type 1 diabetes (T1D). HA is sparse in follicular germinal centers (A) and T-cell areas (C) in normal tissues. (B) and (D) show higher magnification of the boxed areas in (A) and (C), respectively. HA is abundant in B-cell follicular germinal centers (E) and T-cell areas (G) in T1D. (F) and (H) are higher magnification of the boxed areas in (E) and (G), respectively. (A, B, E, and F) Human pancreatic lymph node; (C, D, G, and H) human spleen. Scale, (A, C and G) 100 µm; (E) 50 µm; (B, D, F, and H) 10 µm. Adapted from (Bogdani et al. 2014b) and used with permission.

The finding of accumulation of HA in specific regions of B- and T-cell activation in pancreatic lymph node and spleen in T1D expands the possibilities of HA involvement in T1D pathogenesis beyond that of insulitis. We previously demonstrated that high molecular weight HA augments the suppressor activity and viability of regulatory T cells (Bollyky et al. 2012; Evanko et al. 2012). Further, we showed that the interaction of intact HA (but not fragmented low molecular weight HA) with its receptor CD44 provides an important in situ co-stimulatory signal to adaptive regulatory T-cells via stimulation of the interleukin-2/interleukin-10 pathway, which promotes regulatory T-cell persistence and function (Bollyky et al. 2009). We and others have also shown that HA production induces dendritic cell phenotypic maturation, cytokine production, and antigen presentation. Additionally, HA localizes to the immune synapse, pointing to an important role for HA in antigen presentation and immune signaling (Mummert et al. 2000; Bollyky et al. 2007; Bollyky et al. 2010). It may be that HA accumulation in these specific immune cell regions modulates antigen presentation and enhances immune cell proliferation, migration, and adhesion (Bajenoff et al. 2006), which then results in potentiation of immune responses, sustained T-cell activation, and failure of immune tolerance.

Islet Hyaluronan in Type 2 Diabetes

Although there is good evidence for the accumulation of HA in islets, as well as in spleen and pancreatic lymph nodes, in T1D, to our knowledge, no report exists as to whether islet HA accumulation also occurs in type 2 diabetes (T2D).

The pathogenesis of T1D and T2D differ; however, the loss of islet β cells is a common feature (Maclean and Ogilvie 1955; Gepts 1965; Foulis and Stewart 1984; Kloppel et al. 1985). Other similarities also exist between the pathogenesis of these two forms of diabetes. For example, clinical data suggest that markers of islet autoimmunity in phenotypic T2D are much more common than previously appreciated in both adults and children (Brooks-Worrell et al. 2011; Brooks-Worrell et al. 2013). Moreover, the presence of cellular islet autoimmunity in T2D patients has been demonstrated to be associated with a more rapid decline in β-cell function (Brooks-Worrell et al. 2014). Inflammatory stress is also emerging as a mechanism leading to β-cell death and dysfunction in T2D. For example, the local release of proinflammatory cytokines in response to nutrient stimuli has been reported in cultured human islets (Maedler et al. 2002; Maedler et al. 2004; Donath et al. 2008).

Precedent exists for alterations in islet ECM in T2D, with islet fibrosis being reported (Donath et al. 2008; Hayden et al. 2008) and amyloid deposition occurring in islets of approximately 90% of subjects with T2D (Opie 1901; Westermark 1972; Clark et al. 1988; Jurgens et al. 2011). Islet amyloid deposition is associated with β-cell loss and increased β-cell apoptosis (Jurgens et al. 2011). Recent work has shown that aggregation of the amyloidogenic peptide, human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) in vitro (Masters et al. 2010; Westwell-Roper et al. 2011) or islet amyloid deposition in vivo in hIAPP transgenic mice (Meier et al. 2014; Westwell-Roper et al. 2014) is proinflammatory. Specifically, hIAPP aggregation/amyloid deposition results in chemokine production by islets and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in monocytes/dendritic cells, leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1β. Given the role of HA in inflammatory processes, as described above, we investigated whether there is an association between islet amyloid deposition and HA accumulation. Pancreatic sections were examined from hIAPP transgenic mice, which had been fed a high-fat diet for 12 months, a model of islet amyloid deposition (Fig. 9A) (Hull et al. 2003). In non-transgenic control animals fed a high-fat diet for 12 months that were not predisposed to amyloid deposition (Fig. 9B), HA was present in the peri-islet ECM and was rarely associated with intra-islet ECM (Fig. 9D); this is similar to our findings in normal young mice (Figs. 1A, 6A and 7A). In contrast, significant HA accumulation occurred in islets from hIAPP transgenic mice under conditions of amyloid deposition (Fig. 9C), with increased HA being present in both peri- and intra-islet ECM. Strikingly, the localization of HA accumulation was essentially identical to that of islet amyloid (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, these same animals demonstrated increased macrophage accumulation and upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression in their islets (Meier et al. 2014). Thus, HA accumulation may occur as a result of, and/or contribute to, the pro-inflammatory islet milieu that occurs with islet amyloid deposition.

Figure 9.

Hyaluronan (HA) accumulates in association with islet amyloid deposition in human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP) transgenic mice. Pancreas sections from hIAPP transgenic mice, which develop amyloid after one year of high-fat feeding (A, C), and non-transgenic control mice, which do not (B, D), were labeled: thioflavin S to visualize amyloid (green; A, C, B), insulin immunofluorescence to label β cells (red; A, B) or HA via affinity staining (brown; C, D). Scale, 50 µm.

We believe that HA accumulation in islets may also contribute to this inflammatory milieu, since HA remodeling is almost certainly associated with the generation of proinflammatory HA fragments. In support of this hypothesis, circulating levels of HA, indicative of low molecular weight forms of HA and a marker of inflammation, are substantially upregulated in the plasma of both T2D (Mine et al. 2006) and T1D (Nieuwdorp et al. 2007) subjects. Studies are underway to determine whether, as in T1D, HA accumulation also occurs in islets from human T2D.

Conclusions

HA is a normal component of islet ECM in mice and humans (Bollyky et al. 2012; Hull et al. 2012; Bogdani et al. 2014b). Substantial HA accumulation occurs in islets from individuals with T1D, and in animal models thereof, and under conditions of islet amyloid formation. Although these immunohistochemical studies cannot infer mechanism, we believe that the consistent finding of HA accumulation across these somewhat diverse disease states and animal models strongly suggests that HA may play a role in β-cell loss in both forms of diabetes. We propose that HA may be a novel inflammatory mediator of islet pathology in both T1D and T2D, albeit via different mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Virginia M. Green, PhD, Benaroya Research Institute, for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Puget Sound Health Care System (Seattle, WA, USA), National Institutes of Health grants DK088082 (RLH); DK017047 (University of Washington Diabetes Research Center); and U01 AI101990 Pilot Project, U01 AI101984, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation [nPOD 25-2010-648 (TNW)]. NN was supported by research grant NA 965/2-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- Atkinson MA, Gianani R. (2009). The pancreas in human type 1 diabetes: providing new answers to age-old questions. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 16:279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajenoff M, Egen JG, Koo LY, Laugier JP, Brau F, Glaichenhaus N, Germain RN. (2006). Stromal cell networks regulate lymphocyte entry, migration, and territoriality in lymph nodes. Immunity 25:989-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranova NS, Foulcer SJ, Briggs DC, Tilakaratna V, Enghild JJ, Milner CM, Day AJ, Richter RP. (2013). Inter-α-inhibitor impairs TSG-6 induced hyaluronan cross-linking. J Biol Chem 288:29642-29653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranova NS, Nileback E, Haller FM, Briggs DC, Svedhem S, Day AJ, Richter RP. (2011). The inflammation-associated protein TSG-6 cross-links hyaluronan via hyaluronan-induced TSG-6 oligomers. J Biol Chem 286:25675-25686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdani M, Johnson PY, Potter-Perigo S, Nagy N, Day AJ, Bollyky PL, Wight TN. (2014a). Hyaluronan and hyaluronan binding proteins accumulate in both human type 1 diabetic islets and lymphoid tissues and associate with inflammatory cells in insulitis. Diabetes 63:2727-2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdani M, Korpos E, Simeonovic CJ, Parish CR, Sorokin L, Wight TN. (2014b). Extracellular matrix components in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 14:552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollyky P, Evanko S, Wu R, Potter-Perigo S, Long S, Kinsella B, Reijonen H, Guebtner K, Teng B, Chan C, Braun K, Gebe J, Nepom G, Wight T. (2010). TH1 cytokines promote hyaluronan production by antigen presenting cells and accumulation at the immune synapse. Cell Mol Immunol 7:211-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollyky PL, Bogdani M, Bollyky JB, Hull RL, Wight TN. (2012). The role of hyaluronan and the extracellular matrix in islet inflammation and immune regulation. Curr Diab Rep 12:471-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollyky PL, Falk BA, Long SA, Preisinger A, Braun KR, Wu RP, Evanko SP, Buckner JH, Wight TN, Nepom GT. (2009). CD44 costimulation promotes FoxP3+ regulatory T cell persistence and function via production of IL-2, IL-10, and TGF-β. J Immunol 183:2232-2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollyky PL, Lord JD, Masewicz SA, Evanko SP, Buckner JH, Wight TN, Nepom GT. (2007). Cutting edge: high molecular weight hyaluronan promotes the suppressive effects of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 179:744-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco D, Meda P, Halban PA, Rouiller DG. (2000). Importance of cell-matrix interactions in rat islet beta-cell secretion in vitro: role of alpha6beta1 integrin. Diabetes 49:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Worrell B, Narla R, Palmer JP. (2013). Islet autoimmunity in phenotypic type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Obes Metab 15 Suppl 3:137-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Worrell BM, Boyko EJ, Palmer JP. (2014). Impact of islet autoimmunity on the progressive beta-cell functional decline in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 37:3286-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Worrell BM, Reichow JL, Goel A, Ismail H, Palmer JP. (2011). Identification of autoantibody-negative autoimmune type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 34:168-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai EP, Casimir M, Schroer SA, Luk CT, Shi SY, Choi D, Dai XQ, Hajmrle C, Spigelman AF, Zhu D, Gaisano HY, MacDonald PE, Woo M. (2012). In vivo role of focal adhesion kinase in regulating pancreatic beta-cell mass and function through insulin signaling, actin dynamics, and granule trafficking. Diabetes 61:1708-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chajara A, Raoudi M, Delpech B, Leroy M, Basuyau JP, Levesque H. (2000). Increased hyaluronan and hyaluronidase production and hyaluronan degradation in injured aorta of insulin-resistant rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20:1480-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MY, Chan CK, Braun KR, Green PS, O’Brien KD, Chait A, Day AJ, Wight TN. (2012). Monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: synthesis and secretion of a complex extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem 287:14122-14135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MY, Tanino Y, Vidova V, Kinsella MG, Chan CK, Johnson PY, Wight TN, Frevert CW. (2014). A rapid increase in macrophage-derived versican and hyaluronan in infectious lung disease. Matrix Biol 34:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Wells CA, Buley ID, Cruickshank JK, Vanhegan RI, Matthews DR, Cooper GJ, Holman RR, Turner RC. (1988). Islet amyloid, increased A-cells, reduced B-cells and exocrine fibrosis: quantitative changes in the pancreas in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res 9:151-159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud JT, Petropavlovskaia MS, Patapas JM, Degrandpre CE, Diraddo RW, Rosenberg L, Tabrizian M. (2011). Long-term in vitro human pancreatic islet culture using three-dimensional microfabricated scaffolds. Biomaterials 32:1536-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day AJ, de la Motte CA. (2005). Hyaluronan cross-linking: a protective mechanism in inflammation? Trends Immunol 26:637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Motte CA. (2011). Hyaluronan in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation: implications for fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301:G945-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Motte CA, Hascall VC, Drazba J, Bandyopadhyay SK, Strong SA. (2003). Mononuclear leukocytes bind to specific hyaluronan structures on colon mucosal smooth muscle cells treated with polyinosinic acid:polycytidylic acid: inter-α-trypsin inhibitor is crucial to structure and function. Am J Pathol 163:121-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath MY, Schumann DM, Faulenbach M, Ellingsgaard H, Perren A, Ehses JA. (2008). Islet inflammation in type 2 diabetes: from metabolic stress to therapy. Diabetes Care 31 Suppl 2:S161-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizirik DL, Colli ML, Ortis F. (2009). The role of inflammation in insulitis and beta-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanko SP, Angello JC, Wight TN. (1999). Formation of hyaluronan- and versican-rich pericellular matrix is required for proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19:1004-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanko SP, Potter-Perigo S, Bollyky PL, Nepom GT, Wight TN. (2012). Hyaluronan and versican in the control of human T-lymphocyte adhesion and migration. Matrix Biol 31:90-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulis AK, Stewart JA. (1984). The pancreas in recent-onset type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: insulin content of islets, insulitis and associated changes in the exocrine acinar tissue. Diabetologia 26:456-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch SM, Screaton RA. (2001). Anoikis mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13:555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepts W. (1965). Pathologic anatomy of the pancreas in juvenile diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 14:619-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann J. (2002). Molecular mechanisms of “detachment-induced apoptosis–Anoikis”. Apoptosis 7:247-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto Y, Fujimoto S, Inada A, Takehiro M, Nabe K, Shimono D, Kajikawa M, Fujita J, Yamada Y, Seino Y. (2003). Beneficial effect of pretreatment of islets with fibronectin on glucose tolerance after islet transplantation. Horm Metab Res 35:460-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar E, Parnaud G, Bosco D, Perriraz N, Maedler K, Donath M, Rouiller DG, Halban PA. (2004). Extracellular matrix protects pancreatic beta-cells against apoptosis: role of short- and long-term signaling pathways. Diabetes 53:2034-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar EB, Irminger JC, Rickenbach K, Parnaud G, Ribaux P, Bosco D, Rouiller DG, Halban PA. (2005). Activation of NF-kappaB by extracellular matrix is involved in spreading and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion of pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem 280:30630-30637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden MR, Patel K, Habibi J, Gupta D, Tekwani SS, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. (2008). Attenuation of endocrine-exocrine pancreatic communication in type 2 diabetes: pancreatic extracellular matrix ultrastructural abnormalities. J Cardiometab Syndr 3:234-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes SJ, Clark A, McShane P, Contractor HH, Gray DW, Johnson PR. (2006). Characterisation of collagen VI within the islet-exocrine interface of the human pancreas: implications for clinical islet isolation? Transplantation 81:423-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull RL, Andrikopoulos S, Verchere CB, Vidal J, Wang F, Cnop M, Prigeon RL, Kahn SE. (2003). Increased dietary fat promotes islet amyloid formation and beta-cell secretory dysfunction in a transgenic mouse model of islet amyloid. Diabetes 52:372-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull RL, Johnson PY, Braun KR, Day AJ, Wight TN. (2012). Hyaluronan and hyaluronan binding proteins are normal components of mouse pancreatic islets and are differentially expressed by islet endocrine cell types. J Histochem Cytochem 60:749-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. (2009). The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science 326:1216-1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving-Rodgers HF, Ziolkowski AF, Parish CR, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Simeonovic CJ, Rodgers RJ. (2008). Molecular composition of the peri-islet basement membrane in NOD mice: a barrier against destructive insulitis. Diabetologia 51:1680-1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Liang J, Noble PW. (2011). Hyaluronan as an immune regulator in human diseases. Physiol Rev 91:221-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang FX, Naselli G, Harrison LC. (2002). Distinct distribution of laminin and its integrin receptors in the pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem 50:1625-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens CA, Toukatly MN, Fligner CL, Udayasankar J, Subramanian SL, Zraika S, Aston-Mourney K, Carr DB, Westermark P, Westermark GT, Kahn SE, Hull RL. (2011). beta-cell loss and beta-cell apoptosis in human type 2 diabetes are related to islet amyloid deposition. Am J Pathol 178:2632-2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaido T, Yebra M, Cirulli V, Rhodes C, Diaferia G, Montgomery AM. (2006). Impact of defined matrix interactions on insulin production by cultured human beta-cells: effect on insulin content, secretion, and gene transcription. Diabetes 55:2723-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppel G, Lohr M, Habich K, Oberholzer M, Heitz PU. (1985). Islet pathology and the pathogenesis of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus revisited. Surv Synth Pathol Res 4:110-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpos E, Kadri N, Kappelhoff R, Wegner J, Overall CM, Weber E, Holmberg D, Cardell S, Sorokin L. (2013). The peri-islet basement membrane, a barrier to infiltrating leukocytes in type 1 diabetes in mouse and human. Diabetes 62:531-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota DJ, Wiggins LL, Yoon N, Lee RH. (2013). TSG-6 produced by hMSCs delays the onset of autoimmune diabetes by suppressing Th1 development and enhancing tolerogenicity. Diabetes 62:2048-2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragl M, Lammert E. (2010). Basement membrane in pancreatic islet function. Adv Exp Med Biol 654:217-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley J, Gal I, Mahoney DJ, Cordell MR, Rugg MS, Hyman R, Day AJ, Mikecz K. (2004). TSG-6 modulates the interaction between hyaluronan and cell surface CD44. J Biol Chem 279:25745-25754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Nagira T, Tsuchiya T. (2006). The effect of hyaluronic acid on insulin secretion in HIT-T15 cells through the enhancement of gap-junctional intercellular communications. Biomaterials 27:1437-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean N, Ogilvie RF. (1955). Quantitative estimation of the pancreatic islet tissue in diabetic subjects. Diabetes 4:367-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K, Sergeev P, Ehses JA, Mathe Z, Bosco D, Berney T, Dayer JM, Reinecke M, Halban PA, Donath MY. (2004). Leptin modulates beta cell expression of IL-1 receptor antagonist and release of IL-1beta in human islets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:8138-8143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maedler K, Sergeev P, Ris F, Oberholzer J, Joller-Jemelka HI, Spinas GA, Kaiser N, Halban PA, Donath MY. (2002). Glucose-induced beta cell production of IL-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J Clin Invest 110:851-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Kunimoto K, Muraoka Y, Mizushima Y, Katagiri K, Tochino Y. (1980). Breeding of a non-obese, diabetic strain of mice. Jikken Dobutsu 29:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, Hull RL, Tannahill GM, Sharp FA, Becker C, Franchi L, Yoshihara E, Chen Z, Mullooly N, Mielke LA, Harris J, Coll RC, Mills KH, Mok KH, Newsholme P, Nunez G, Yodoi J, Kahn SE, Lavelle EC, O’Neill LA. (2010). Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1beta in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol 11:897-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Q, Mundinger TO, Lernmark A, Taborsky GJ., Jr. (2002). Early, selective, and marked loss of sympathetic nerves from the islets of BioBreeder diabetic rats. Diabetes 51:2997-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier DT, Morcos M, Samarasekera T, Zraika S, Hull RL, Kahn SE. (2014). Islet amyloid formation is an important determinant for inducing islet inflammation in high-fat-fed human IAPP transgenic mice. Diabetologia 57:1884-1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith JE, Jr., Fazeli B, Schwartz MA. (1993). The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol Biol Cell 4:953-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mine S, Okada Y, Kawahara C, Tabata T, Tanaka Y. (2006). Serum hyaluronan concentration as a marker of angiopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Endocr J 53:761-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mummert ME, Mohamadzadeh M, Mummert DI, Mizumoto N, Takashima A. (2000). Development of a peptide inhibitor of hyaluronan-mediated leukocyte trafficking. J Exp Med 192:769-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschel R, Khoury G, Reid LM. (1986). Regulation of insulin mRNA abundance and adenylation: dependence on hormones and matrix substrata. Mol Cell Biol 6:337-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata N, Gu Y, Hori H, Balamurugan AN, Touma M, Kawakami Y, Wang W, Baba TT, Satake A, Nozawa M, Tabata Y, Inoue K. (2001). Evaluation of insulin secretion of isolated rat islets cultured in extracellular matrix. Cell Transplant 10:447-451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Alvarez N, Rivas-Carrillo JD, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yuasa T, Okitsu T, Noguchi H, Matsumoto S, Takei J, Tanaka N, Kobayashi N. (2008). Reestablishment of microenvironment is necessary to maintain in vitro and in vivo human islet function. Cell Transplant 17:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neame PJ, Barry FP. (1993). The link proteins. Experientia 49:393-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwdorp M, Holleman F, de Groot E, Vink H, Gort J, Kontush A, Chapman MJ, Hutten BA, Brouwer CB, Hoekstra JB, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. (2007). Perturbation of hyaluronan metabolism predisposes patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus to atherosclerosis. Diabetologia 50:1288-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova G, Jabs N, Konstantinova I, Domogatskaya A, Tryggvason K, Sorokin L, Fassler R, Gu G, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Melton DA, Lammert E. (2006). The vascular basement membrane: a niche for insulin gene expression and Beta cell proliferation. Dev Cell 10:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie EL. (1901). The relation of diabetes mellitus to lesions of the pancreas. Hyaline degeneration of the islets of Langerhans. J Exp Med 5:527-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otonkoski T, Banerjee M, Korsgren O, Thornell LE, Virtanen I. (2008). Unique basement membrane structure of human pancreatic islets: implications for beta-cell growth and differentiation. Diabetes Obes Metab 10(Suppl 4):119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnaud G, Hammar E, Rouiller DG, Armanet M, Halban PA, Bosco D. (2006). Blockade of beta1 integrin-laminin-5 interaction affects spreading and insulin secretion of rat beta-cells attached on extracellular matrix. Diabetes 55:1413-1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter-Perigo S, Johnson PY, Evanko SP, Chan CK, Braun KR, Wilkinson TS, Altman LC, Wight TN. (2010). Polyinosine-polycytidylic acid stimulates versican accumulation in the extracellular matrix promoting monocyte adhesion. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 43:109-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JD, Horton MR. (2005). Threat matrix: low-molecular-weight hyaluronan (HA) as a danger signal. Immunol Res 31:207-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Diaz R, Abdulreda MH, Formoso AL, Gans I, Ricordi C, Berggren PO, Caicedo A. (2011). Innervation patterns of autonomic axons in the human endocrine pancreas. Cell Metab 14:45-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondas D, Tomas A, Soto-Ribeiro M, Wehrle-Haller B, Halban PA. (2012). Novel mechanistic link between focal adhesion remodeling and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 287:2423-2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem S, Li J, Yee SP, Fellows GF, Goodyer CG, Wang R. (2009). beta1 integrin/FAK/ERK signalling pathway is essential for human fetal islet cell differentiation and survival. J Pathol 219:182-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern R, Asari AA, Sugahara KN. (2006). Hyaluronan fragments: an information-rich system. Eur J Cell Biol 85:699-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole BP. (1990). Hyaluronan and its binding proteins, the hyaladherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2:839-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toole BP, Wight TN, Tammi MI. (2002). Hyaluronan-cell interactions in cancer and vascular disease. J Biol Chem 277:4593-4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley EA, Noble PW, Bourguignon LY. (2002). Signaling properties of hyaluronan receptors. J Biol Chem 277:4589-4592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deijnen JH, Van Suylichem PT, Wolters GH, Van Schilfgaarde R. (1994). Distribution of collagens type I, type III and type V in the pancreas of rat, dog, pig and man. Cell Tissue Res 277:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen I, Banerjee M, Palgi J, Korsgren O, Lukinius A, Thornell LE, Kikkawa Y, Sekiguchi K, Hukkanen M, Konttinen YT, Otonkoski T. (2008). Blood vessels of human islets of Langerhans are surrounded by a double basement membrane. Diabetologia 51:1181-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, de la, Motte C, Lauer M, Hascall V. (2011). Hyaluronan matrices in pathobiological processes. FEBS J 278:1412-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber LM, Anseth KS. (2008). Hydrogel encapsulation environments functionalized with extracellular matrix interactions increase islet insulin secretion. Matrix Biol 27:667-673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L, Slavin S, Reich S, Cohen P, Shuster S, Stern R, Kaganovsky E, Okon E, Rubinstein AM, Naor D. (2000). Induction of resistance to diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice by targeting CD44 with a specific monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:285-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley JD, Sather BD, Perdue NR, Ziegler SF, Campbell DJ. (2010). Cellular requirements for diabetes induction in DO11.10xRIPmOVA mice. J Immunol 185:4760-4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermark P. (1972). Quantitative studies on amyloid in the islets of Langerhans. Ups J Med Sci 77:91-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwell-Roper C, Dai DL, Soukhatcheva G, Potter KJ, van Rooijen N, Ehses JA, Verchere CB. (2011). IL-1 blockade attenuates islet amyloid polypeptide-induced proinflammatory cytokine release and pancreatic islet graft dysfunction. J Immunol 187:2755-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwell-Roper CY, Ehses JA, Verchere CB. (2014). Resident macrophages mediate islet amyloid polypeptide-induced islet IL-1beta production and beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes 63:1698-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wight T, Evanko S. (2002). ‘Hyaluronan is a critical component in atherosclerosis and restenosis and in determining arterial smooth muscle cell phenotype’ in Kennedy J, Philips G, Williams P, Hascall V. (eds.) Hyaluronan, Cambridge:Woodhead Publishing Ltd., pp. 173-176. [Google Scholar]

- Wight TN, Kang I, Merrilees MJ. (2014). Versican and the control of inflammation. Matrix Biol 35:152-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Yoneda M, Ohashi Y, Kurono S, Iwata H, Ohnuki Y, Kimata K. (1995). Evidence for the covalent binding of SHAP, heavy chains of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor, to hyaluronan. J Biol Chem 270:26657-26663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo L, Kanamori A, Kannagi R, Itano N, Wu J, Hamaguchi M, Ishiguro N, Kimata K. (2006). SHAP potentiates the CD44-mediated leukocyte adhesion to the hyaluronan substratum. J Biol Chem 281:20303-20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]