Abstract

Inflammation is a highly organized event impacting upon organs, tissues and biological systems. Periodontal diseases are characterized by dysregulation or dysfunction of resolution pathways of inflammation resulting in a failure of healing and a dominant chronic, progressive, destructive and predominantly unresolved inflammation. The biological consequences of inflammatory processes may be independent of the etiological agents such as trauma, microbial organisms and stress. The impact of the inflammatory pathological process depends upon the affected tissues or organ system. Whilst mediators are similar, there is a tissue specificity for the inflammatory events. It is plausible that inflammatory processes in one organ could directly lead to pathologies in another organ or tissue. Communication between distant parts of the body and their inflammatory status is also mediated by common signaling mechanisms mediated via cells and soluble mediators. This review focuses on periodontal inflammation, its systemic associations and advances in therapeutic approaches based on mediators acting through orchestration of natural pathway to resolution of inflammation. We also discuss a new treatment concept where natural pathways of resolution of periodontal inflammation can be used to limit systemic inflammation and promote healing and regeneration.

Inflammation is an organized event that affects susceptible organs, tissues and systems including the periodontium. Under healthy or “normal” conditions, the inflammatory process enters a programmed resolution cycle through natural pathways of healing (119). As in many other diseases where inflammation is the central cause of pathology, periodontal diseases are characterized by a dysregulation or dysfunction of resolution pathways (63). The result is a failure of healing and a dominant chronic, progressive, and destructive, but mostly unresolved inflammation (128).

The biological consequences of inflammatory processes can be viewed as the root cause for many pathological diseases. These processes can be initiated independently of the etiological agents such as trauma, microbial organisms, and stress. Understanding resolution pathways has led to a change in paradigm of how disease entities are perceived and how these understandings can be applied to the development of novel treatment strategies (50).

The fate of tissues affected by the inflammation depends on many factors; the process may be organ-specific and may not always be predicted through an understanding of the inflammatory process in one organ and adaptation of this knowledge to another organ. Yet, it is critical to elucidate the common pathways of inflammation at activation and resolution stages and identify the cellular and molecular mechanisms. Resolution is an active process and is modulated by endogenous mediators as agonists (117). The discovery of new families of lipoxins, eicosapentaenoic acid- and docosahexaenoic acid-derived chemical mediators (resolvins), protectins and maresins has opened avenues in designing resolution-targeted therapies to control unwanted side-effects of aberrant inflammation (122). Increasing evidence on the success of these mediators in returning the tissues to homeostasis is promising and helpful in understanding the mechanisms involved in the pathogenic processes (47, 76, 90, 96, 112). This approach may also provide new insights into our understanding of the link between local and systemic diseases as a whole.

Inflammatory diseases share a common diagnostic and prognostic definition if they remain active: aberrant and uncontrolled inflammation of the target tissues and incurable progressive outcomes. The severity of the inflammatory pathological condition for the human’s life depends on the affected tissues or organ system. In vital tissues such as heart, lung, kidney, or liver, the progression of inflammation can be devastating. In peripheral tissues; however, the inflammatory process can follow a slowly progressive path. Thus, while the mediators may be similar, there exists a tissue specificity for the inflammatory events. Another major issue in understanding inflammation as an entity is the communication between distant organs. While it is plausible that inflammatory processes in one organ could directly lead to the pathologies in another organ or tissue, communication between distant parts of the body and their inflammatory states is mediated by common signaling mechanisms via cells or soluble mediators (49).

For decades since an understanding of the biology of periodontal tissues and pathologies has evolved, they were perceived that the only significant consequence of periodontal disease was tooth loss, and therefore, periodontitis was seen as a concern only to dentists. Indeed, the origins of this belief date back to ancient times when tooth loss was considered as a natural consequence of aging and “normal and harmless” to human life. Books on the natural history of dental diseases famously depicted a patient with a tooth ache treated by a barber using a tool that resembles today’s extraction forceps (20). Once the “rotten and decayed” teeth were extracted, it was assumed to pose no further risk to the patient (136). This approach has led to extensive extractions of teeth as a “cure” for “gum diseases” and at the same time it was believed that infectious “foci” were eliminated from the body (42, 92). Even today, despite our modern world with advanced technological improvements, tooth extraction is still one of the most common dental procedures and such beliefs remain (78). There are still debates on the focal infection theory (57). Meanwhile, a new problem is emerging. With the introduction of dental implants, extraction and replacement of teeth with titanium counterparts has become common practice. This approach is also promoted as a cure for “untreatable” teeth and periodontally diseased tissues by many clinicians. Yet, without a thorough understanding of the inflammatory processes underlying the cause of periodontal diseases, placement of implants in the mouths of patients with a history of, or with existing periodontal disease, further elevates the risk for peri-implantitis (81). In addition, with an appreciation of the mechanistic links between systemic inflammatory diseases such as uncontrolled diabetes and cardiovascular diseases and periodontal and peri-implant pathologies, where virtually no unequivocal data exist, the issue becomes even more complex (125).

Treatment methods in clinical periodontology meanwhile do not present better choices. Most approaches employ the same principles as Pierre Fauchard indicated in his 1746 publication entitled “Le Chirurgien Dentiste” and include scaling with instruments (53), use of mouthwashes and dentifrices (84). These approaches are often successful in eliminating the etiology of periodontal diseases by removing the niches for bacterial colonization and preventing growth of pathogenic species. When repeated, treatment based on these techniques can arrest the inflammatory process and tissue break-down. On the other hand, such conventional and historically proven methods are insufficient in halting disease progression in many patients mainly due to a lack of thorough understanding of the biology of periodontal tissues and the inflammatory processes. In addition, if success is defined as the “full restoration to homeostasis”, a complete regeneration of the lost tissue architecture is required. This is even more complicated and unpredictable when it comes to susceptible individuals with co-morbidities such as diabetes or other inflammatory diseases (33). Thus, an accurate characterization of the disease systems and mechanisms of inflammation will not only enable us to measure the impact between multiple diseases and develop new therapeutics, but will also help to develop a “personalized” treatment approach specifically targeting the susceptible individual rather than prescribing the same treatment to all subjects regardless of the underlying cause. It is time for a paradigm shift in our understanding of diseases that will help to develop new therapeutics for our well-being and to reduce/eliminate disabilities. This review focuses on periodontal inflammation, its systemic associations and advances in therapeutic approaches based on mediators acting through the orchestration of natural resolution of inflammation pathways (Fig. 1).

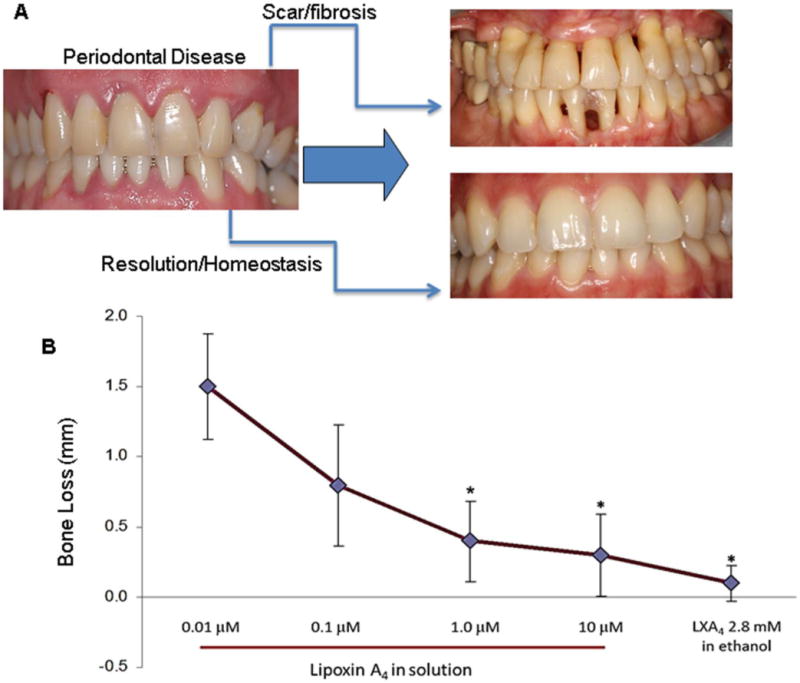

Fig. 1. Goal and outcome of periodontal treatment.

A. Chronic periodontitis results in irreversible damage to the periodontal organ leading to tooth loss. Current therapeutic approaches can stop the progression of the disease and delay tooth loss however tissues lost to the disease remain compromised and are vulnerable to reactivation of the disease. Fibrosis and scarring are the characteristics of healing during chronically resolving inflammation. Conversely, the goal of the treatment is to restore the periodontal tissues to their original architecture and return to health, which can be achieved by resolution of inflammation. B. Newly identified novel lipid mediators, (e.g., lipoxin A4) have the capacity of activating resolution-specific pathways and a return to periodontal homeostasis, including regeneration of bone and soft tissue lost to the disease. Note that topically used lipoxin A4, in micromolar concentrations, was capable of reversing bone loss up to 100% in animal experiments.

Inflammatory nature of periodontal disease

Periodontal disease is among the most common of human diseases; initiated by specific species of microorganisms (40, 121). Such pathogenic bacteria were assumed, by association, to be directly involved in the destruction of the host tissues. Host-related factors such as genetics and the inflammatory-immune response, and environmental factors including diet, smoking, stress, systemic health, and socio-demographic elements, are all now recognized as major determinants of the initiation and progression of disease. Despite current periodontal therapeutic approaches that target “pathogenic” species, permanent eradication of bacteria is not possible or desirable (45, 86). Development of sensitive microbiological techniques for the identification of bacteria (100) revealed that the pathogenic biofilm in periodontitis represents an overgrowth of commensal organisms (89). Induction of inflammatory signaling pathways by pathogenic bacteria is crucial for development of inflammatory events in the periodontium. Application of highly technological advances to periodontal microbiology demonstrates the critical role played by microbial communities during the transition from health to disease. These findings also support the multi-faceted complexity of periodontitis pathogenesis (5) and the role of the inflammatory response and other host related factors in the disease process (66, 128).

The host’s immune response depends on the activity of leukocytes. Phagocytes (macrophages and neutrophils) are a group of leukocytes that are immediately available to combat a wide range of pathogens without prior exposure as key cells of the innate immune response (18, 64). Lymphocytes mediate the adaptive immune response. Many infections are handled successfully by the innate immune response and cause no disease, however an infection, which cannot be resolved by innate immunity, triggers adaptive immunity to overcome it. Malfunction of the immune system to respond properly to infections can cause diseases such as allergy and autoimmunity (73).

Inflammation, which is initiated as a protective response to pathogens, foreign bodies or an injury is characterized by vascular dilation, enhanced permeability of blood capillaries, increased blood flow and leukocyte recruitment into tissues (22). In periodontal tissues, this process starts with the penetration of bacterial products through the epithelial lining although there is still a debate regarding the physical penetration of bacteria themselves through the epithelial barrier. It has become clear that the junctional and sulcular epithelial structures lining the periodontal sulcus and pocket are actively involved in the defense processes beyond their role as a physical barrier (11). In addition to the epithelial barriers and fluid exudates that carry components of the immune response, polymorphonuclear neutrophils are the first leukocytic cells of the innate immune system to accumulate at the site of insult. In an effective and healthy immune system, neutrophil antimicrobial functions are followed by an efficient clearance of the resulting cellular debris by mononuclear cells (monocytes and macrophages). Mononuclear phagocytes are responsible for clearing these sites from apoptotic neutrophils by phagocytosis. The goal at this stage is to resolve the inflammation at the acute level and establish tissue homeostasis. Immune cells are cleared, epithelial structures return to normal, and vascularization is reduced with no damage to the tissues. This process usually eliminates the bacterial insult (14, 41).

As in other inflammatory conditions however, periodontal inflammation becomes chronic either when the microbial species continue to grow and cannot be eliminated by the acute response, or a defective/aggravated immune response results in a prolonged inflammatory reaction and host tissue damage, which provides a source of nutrients to pathogens to survive. Chronic and progressive periodontal disease is characterized by an unresolved inflammation, fibrosis and loss of tissue structure and function. Cells and mediators of adaptive immunity such as lymphocytes are recruited, macrophage populations continue to be activated, and an antibody response is mounted. This phase is usually non-linear and follows an episodic pattern. If unresolved, this results in apical migration of the epithelial lining paralleled with destruction of the alveolar bone and periodontal attachment. Pain is an uncommon feature of periodontitis as nerve signaling pathways appear to be downregulated; therefore, patients are typically unaware of the underlying condition. The periodontal tissues become highly inflamed, bleed due to microulceration of the pocket lining epithelium, and harbor large numbers of a diverse bacterial community in an ever-growing and organized biofilm (49).

Periodontal inflammation as a risk factor for systemic inflammation and disease at distant tissues

If the human body is viewed as a single entity, a local disruption of the homeostatic balance cannot be merely observed as an isolated phenomenon limited in its impact. The cells and mediators of the inflammatory response are unlikely to remain confined to the organ system in question. This is also true for periodontal tissues. In addition, being a niche for the second most diverse human microbiome, the oral tissues are never sterile. Commensal species with oral biofilms always have the potential of becoming pathogenic. This evolutionary interaction between the host and the microbiota has led to the development of a highly specialized host response in periodontal tissues where the epithelia and vasculature demonstrate considerable anatomical differences compared to the other parts of the body. As a function of this complex interaction, the immune cells travel to distant organs through the systemic circulation. Evidence is accumulating on how immune system cells challenged by local periodontal stimuli and processes may transmit the inflammatory response to other organs (51). Recent data on dendritic cells demonstrate how these critical cells of immune response and “presenters” of antigens; can also serve as “transporters” of bacteria and their virulence factors (91). Likewise, the concept of a “mobile oral microbiome” involves a direct migration and colonization of the oral resident microbial species to distant organs (44). Therefore, there are potentially two mechanisms; through which the immune system and inflammatory process may play role in affecting distant organs:

1. Direct migration and colonization of periodontal microbial species to distant organs eliciting an inflammatory reaction distant from the point of invasion

Theoretically, all microbial organisms and their products can travel throughout the body via the circulation. Sepsis or septicemia is the pathological result of bacteremia, which involves the presence of bacteria in blood and its compartments. Since bleeding is a common sign and symptom of periodontal inflammation, every time the periodontal pocket bleeds, microbial communities or single species enter into the blood circulation. This can be the result of disease activity or may arise due to periodontal procedures such as probing or scaling. There is conflicting data on how many bacteria can be found in the systemic circulation following an active burst of periodontal disease, after bleeding on probing, or due to mechanical instrumentation (54, 82, 83). This may be the result of differing sensitivities of detection methods for bacteria and the timing of the bacteremia (8). Whilst bacteremia is an accepted phenomenon (23, 67); it remains unclear whether septicemia could be the result of periodontal infection and instrumentation.

An important question in this context is the number of bacteria mixing with the blood in local tissues and travelling through systemic circulation. How many bacteria enter the circulation and how many are required to cause disease elsewhere in the body? Which organs are more susceptible to oral bacteria and why? These questions require extensive experimentation with highly sensitive detection platforms. Nevertheless, regardless of the number of bacteria, a healthy immune system has the capacity to eliminate and eradicate the invaders quite efficiently. Therefore, a defective and dysfunctional immune response is a prerequisite for the initiation and progression of inflammatory diseases due to migrating bacteria.

The duration of bacteremia until clearance is also critical. In the case of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and viral infections (e.g. HIV), latency of the infection is a major determinant of the disease outcome. Days to weeks may be required before a full-blown infection and the consequent host response is mounted with respect to oral bacteria disseminating to other parts of the body, this knowledge is currently limited.

According to the Koch’s postulates, a single species has the capacity to cause a systemic disease if sufficient time lapses between the inoculation and infection. This concept has been repeatedly and successfully illustrated in the case of the inoculation of periodontal pathogens in animal models (36). There is however, no evidence that this could be the case in humans. First, ethical concerns prevent such a model of inoculation and experimental transfer of periodontal pathogens into humans. Secondly, even in cases where inter-individual transfer is possible between spouses (30, 129) there is no clear evidence that either periodontal infections or systemic infections can be attributed to the periodontal microbiota that is introduced.

A modification of Koch’s postulates was presented by Socransky, where these strict requirements were suggested to be different in the case of periodontal microbial species. Data suggests that bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides may be derived from the periodontal microbiota and enter the circulation. This phenomenon has not been studied in depth but presents a potentially plausible mechanism through which bacterial communities from the periodontal tissues can be found in the blood circulation.

Another important factor is the colonization capacity of oral species on non-dental and non-oral surfaces. While in vitro model systems demonstrate that all cell types and structures of the human body can present favorable environments for colonization of individual or multiple oral species under controlled environmental conditions in the laboratory, in vivo data is missing. There is evidence that periodontal species or their genetic material may be found in cardiovascular tissues (27) suggesting that distant organs can be potential growth sites for pathogenic periodontal microbes such as Porphyromonas gingivalis. Likewise, bridging species such as Fusobacterium nucleatum have been found in amniotic fluid (43). This area of research is evolving and will demonstrate whether periodontal bacteria may find safe havens for growth and colonization in distant organs.

2. Systemic inflammation as a result of metastatic periodontal inflammation or activated soluble inflammatory pathways by blood-borne periodontal bacteria

This concept has long been debated between dental epidemiologists and medical professionals and direct causal links are being questioned despite strong epidemiological associations. Causality between inflammatory diseases cannot currently be proven in humans; thus, in vitro and in vivo models are critical to this field of research.

Based on well-designed epidemiological studies, it has been shown that people with periodontal diseases present a higher risk for systemic inflammation (12, 56). Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory condition that shares common mechanistic pathways with other systemic inflammatory diseases. To this end, strong evidence is accumulating for co-morbid associations between periodontitis and other inflammatory diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and rheumatoid arthritis. To a lesser extent, periodontal infection and inflammation are regarded as risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic kidney disease. Such evidence is derived from clinical and epidemiological data, data from animal models and from in vitro experimentation (17, 101, 113, 126).

Diabetes mellitus

Although periodontal disease and Type 2 diabetes are seemingly dissimilar, affecting different organs and having distinct etiologies, they share a common mediator of morbidity, namely unresolved inflammation. Increasing evidence supports elevated levels of systemic inflammation (acute-phase and oxidative stress biomarkers) resulting from the entry of periodontal organisms and their virulence factors into the circulation, providing biological plausibility for the impact of periodontitis on diabetes (15). Makiura et al (2012) postulated that glycemic control in patients with periodontitis and diabetes is potentially influenced by the persistence of P. gingivalis, particularly clones with type II fimbriae, following treatment (87). It has also been reported during in vitro studies that cytokine induction (specifically interleukin 1beta, interleukin-8, interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) by P. gingivalis with type II fimbriae is greater than that induced by P. gingivalis with type I fimbriae (124), and in animal studies where P. gingivalis inoculation led to elevated serum levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 (95). At present however, there is no strong evidence to support the contention that the periodontal microbiota has any direct impact on the diabetic state or on glycemic control.

Chronicity of inflammation presents the strongest plausibility for detrimental effects of inflammatory events that could also link periodontal disease to diabetes. Mechanisms underlying the chronicity of inflammation in diabetes and the link to periodontal disease are poorly defined. Toll-like receptor 4 has a major role in pro-inflammatory cytokine production by myeloid cells (7). In previous work, we sought to determine whether toll-like receptor 4 expression was altered by chronic inflammatory diseases. We evaluated blood samples from 40 healthy donors, 17 patients with inflammatory bowel disease (including 16 patients with Crohn’s disease) and 35 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Patients had varying degrees of periodontitis. We found no differences between myeloid cell levels of toll-like receptor 4 in healthy or diseased donors. However, we identified a novel and common player in the pathogenesis of both diseases: Circulating Toll-like receptor 4-positive human B lymphocytes. This phenomenon is important since it was previously believed that human B cells lacked surface toll-like receptor 4 and did not respond to the toll-like receptor 4 ligand, lipopolysaccharide. Few B cells from healthy donors expressed surface toll-like receptor 4 (n=40), whereas upwards of 97% of B cells in the peripheral blood of patients with chronic inflammatory disease were toll-like receptor 4-positive. In contrast to toll-like receptor 4-positive myeloid cells, B cells have an intrinsic ability to recirculate and therefore have the potential to promote systemic inflammation demonstrating signatures of activation (59, 120, 138). Recently, we have also shown that neutrophils from individuals with both diabetes and chronic periodontitis show a significant reduction in apoptosis compared to people with diabetes or chronic periodontitis alone where Caspase 3 and 8 activities were significantly reduced compared to healthy controls (unpublished data). Although these observations do not show a direct impact of periodontal disease on diabetes since the exposure sequence is unknown; they may still suggest that spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis is impaired in subjects with chronic inflammation and that chronic periodontitis may contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetes by increasing the inflammatory burden and impeding the resolution of systemic inflammation.

Chronic dysregulation and imbalance of peripheral cytokine networks is now considered a central pathogenic factor in diabetes (69). Systemic levels of inflammatory mediators including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interleukin-6 are elevated in periodontal diseases (13, 31, 99) and may be the link to diabetes in susceptible individuals. Increases in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels over a 5-year period in patients with periodontitis were highest in individuals with high levels of C-reactive protein suggesting an interaction between periodontitis and systemic inflammation (26). This data highlights the importance of the chronicity of inflammation and the risk it poses in susceptible individuals.

Our laboratory and others have repeatedly shown that oxidative stress is one of the major determinants of chronic inflammation (3, 16, 29, 38, 65). These studies suggested that hyperactive neutrophils, possibly activated in the periodontium by the local inflammation, may be an important source of reactive oxygen species, which lead to an activation of pro-inflammatory pathways and promote insulin resistance in patients with periodontitis and diabetes (3). Increased oxidative stress may also result in elevated lipid peroxidation, which, in turn may have a proinflammatory effect. A recent study has demonstrated higher levels of gingival crevicular fluid markers of lipid peroxidation in diabetes patients, which correlated with clinical parameters of periodontitis and levels of inflammatory mediators (9). In a recent clinical study from our laboratory we demonstrated that individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus and periodontitis exhibit an imbalance in circulating levels of proinflammatory markers (reduced levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-10, interleukin 4 and adiponectin versus elevated levels of C-reactive protein), which was restored following elimination of periodontal inflammation over 12 months (unpublished data). In summary, while there is evidence for a role for circulating inflammatory mediators (C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6) in patients with co-existing periodontitis and diabetes, more research is needed to investigate this further. Oxidative stress in diabetes may activate pro-inflammatory pathways in the periodontium and vice versa, as the comorbid presence of both conditions creates further oxidative stress and dyslipidemia (3).

Cardiovascular diseases

Vascular diseases and their ischemic complications, including myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular diseases and stroke, are the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in the aging population. The underlying cause, atherosclerosis, is a chronic progressive inflammatory disease characterized by vascular inflammation and sub-intimal lipid accumulation. There is now significant epidemiological evidence for an association between oral infections, particularly periodontitis, and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (28). Statistically significant excess risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease independent of established risk factors in people with periodontitis has been reported in a number of well-controlled studies (28). Disruption of endothelial function is one of the earliest indicators of cardiovascular disease, which can be initiated by a number of factors (68, 103, 131), including infection (130, 131). Microbial invasion by pathogenic oral species as suggested above has been proposed as a direct mechanism for cardiovascular pathology. An infectious etiology was considered to be a potential co-factor for the development of cardiovascular diseases. This was based on the discovery of co-localization of bacteria (particularly Chlamydia species) in atheromas. Initial reports of an epidemiological association between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease coincided with the Chlamydia observations in atherosclerotic lesions and initiated the idea that periodontal bacteria could be causal in cardiovascular disease. There are examples in the literature of studies demonstrating oral bacteria in atheromas, but the rationale suggesting that antibiotic therapy may be expected to have an impact on disease progression could be flawed. Once the atherogenic process is established, it may be too late for the antibiotic therapy to be effective. Richardson reported that an infectious agent anywhere in the body might lead to the co-activation of the innate immune system and this co-activation accelerates atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic rabbits suffering from respiratory tract infections with Pasteurella multocida (108, 109). Hence, infectious agents might be an indirect etiological factor for cardiovascular disease providing the necessary inflammatory stimulus. However, human atheromas often lack any indication of the presence of infectious agents, and even if an infectious particle is present in the lesion, a pathogenic role is far from established for that particular organism.

Throughout the microbial world, there are strain differences within a species and these differences sometimes influence virulence. It is proposed that this is the case for periodontopathogenic species in relation to cardiovascular diseases (106). For example, P. gingivalis 381 (fimbriae type I) induces gene expression of growth-regulated oncogene-alpha and gamma, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule in human coronary artery endothelial cells, which is a fimbriae-dependent phenomenon (19) mediated through engagement of toll-like receptors (139). Conversely, P. gingivalis strain W83, which is capsule-positive but does not express fimbriae, induces moderate activation of toll-like receptor 2 and an attenuated inflammatory response in human coronary artery endothelial cells when compared to 381 (111). Similarly, capsule-positive strain P. gingivalis A7436, which expresses type IV fimbriae, also induces a moderate inflammatory response in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Interestingly, both W83 and A7436 can accelerate atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice (77, 85), suggesting that periodontal bacteria can promote atherosclerosis through other mechanisms that may not involve profound activation of endothelial cells. Most recently, we have shown that induction of periodontal disease by P. gingivalis A7436 strain in an accelerated atherosclerosis model in rabbits can provoke the atherosclerotic changes and result in a more severe form of atherosclerotic lesion (46).

However, it is most likely that the link between periodontitis and atherosclerotic disease in humans is through inflammation. A body of evidence in the cardiology literature suggests that a local inflammatory nidus can increase vascular inflammation systemically (80). Recent papers suggest that an elevated innate host response of any origin is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease as well as periodontitis, suggesting the inflammatory response as a common determinant of susceptibility. A relatively recent study revealed that initiation of isolated inflammation in the murine dorsal air pouch model resulted in an up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA in the heart and lung supporting the hypothesis that the magnitude of the inflammatory response to insult or injury is a major determinant in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, including periodontitis and cardiovascular disease (104). We have shown that P. gingivalis can induce periodontal inflammation and can also worsen the co-existent atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits; however, P. gingivalis DNA was non-existent in the atheroma tissues as shown by polymerase chain reaction (60). In a most recent study, we demonstrated that periodontal disease induction accelerated atherogenesis as evidenced by dramatic changes in the arterial layers, intima and media causing smooth muscle cell proliferation leading to medial fibrosis, macrophage infiltration and necrotic core formation with increased intimal thickness and fibrous cap formation (46). In addition, the circulating levels of C-reactive protein were significantly elevated by the presence of periodontitis (Fig. 2). In summary, results indicate that local inflammatory diseases, in this case, periodontal disease can accelerate the initiation and/or progression of another disease in a distant organ. Thus, therapeutic approaches should target host modulation to induce the effective resolution mechanisms that could change the fate of the inflammatory events and stimulate a return to homeostasis.

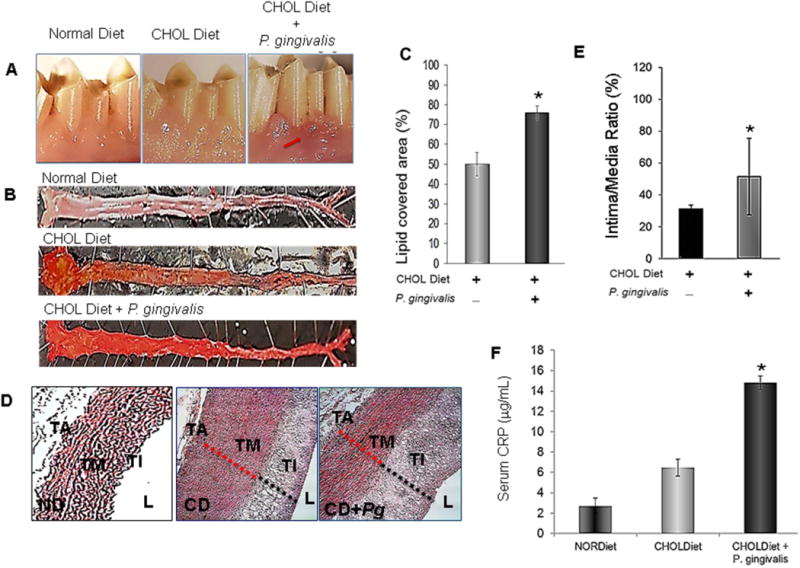

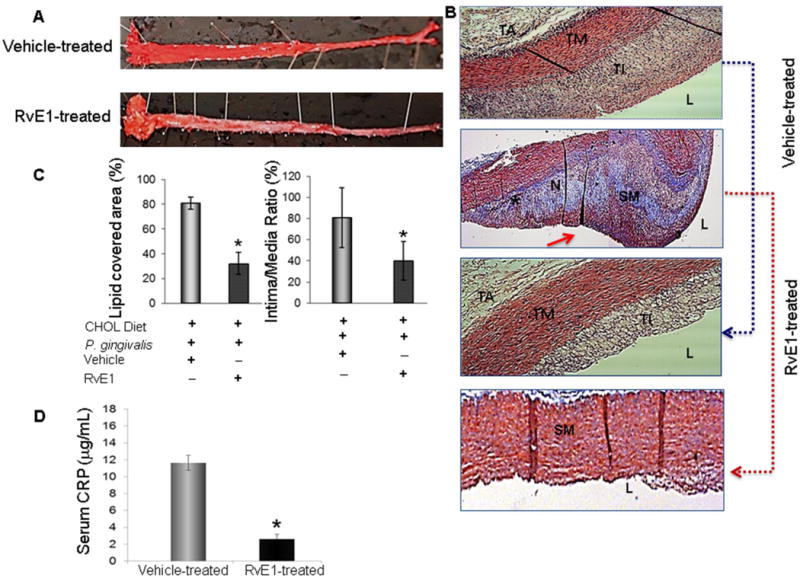

Fig. 2. Impact of periodontal disease on atherosclerotic changes in aorta.

A. Clinical presentation of P. gingivalis induced experimental periodontitis in 0.5% cholesterol-fed rabbits compared to those that did not receive P. gingivalis (Normal Diet and Cholesterol Diet). Arrow depicts the area of interest B. Aortas were cut en-face, pinned down and stained with Sudan IV to detect fatty deposits. The top figure depicts an aorta from an animal who received a normal diet. Animals received P. gingivalis in addition to a cholesterol diet showed greater and extended plaque formation compared to a cholesterol diet alone. C. Quantification of area covered by lipids showed significant differences between group (n=4; p<0.05). D. Aortas were embedded in paraffin; thin sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histomorphometric assessments of media and intima thickness. E. Intima/media ratio was calculated. P. gingivalis induced periodontal inflammation significantly increased the intima/media ratio indicated by dramatic intimal thickening and atrophic media, the characteristics of an atherosclerotic aortic wall (p<0.05) Pg: P. gingivalis. TA: tunica adventitia; TM: tunica media; TI: tunica intima; L: lumen; ND: Normal Diet; CD: Cholesterol diet. *Statistically significant compared to CD and ND.

Impact of systemic inflammation on periodontal tissues

A classic example where a systemic inflammatory disease impacts the periodontal tissues is diabetes. Since the dawn of human kind, the link has been acknowledged and explored in the medical literature. Periodontal disease has been recognized as a complication of diabetes. The link between the systemic inflammation of diabetes and periodontal disease presents a model for how a two-way relationship impacts upon local and distant organs. Various mechanisms have been proposed where the cells and mediators of the immune system play the central role. Data on neutrophils demonstrate the mechanistic links that can result from these phagocytic cells (107). Protein kinase C presents a potential target for regulation of inflammatory conditions relevant to both periodontal and diabetes-related inflammation (65, 93). Likewise, another phagocytic cell type, the macrophage plays a critical role suggesting that innate immune responses are the direct regulators of inflammation in patients with diabetes and periodontal disease (49). Recent data has demonstrated roles for the B and T lymphocytes adding to this complexity (58, 72, 140). Non-immune cells such as adipocytes and epithelial cells as well as vascular cells are all involved in diabetes-induced inflammation and its impact on periodontal tissues (105).

An important finding from experimental in vivo and in vitro models as well as the cells of individuals with poorly-controlled diabetes is that diabetes ubiquitously impacts all cell types and organs including the periodontal tissues (79). This observation suggests a common mechanism underpinning the chronicity of diabetic inflammation and the hyperglycemic state. Hyperglycemia presents a major stress on mammalian tissues and can result from a variety of conditions such as genetic defects where the intake of glucose may not be counteracted by the hormonal actions of insulin and glucagon regulation or as a function of acquired conditions such as obesity or toxicity by drugs where the production of insulin and the function of the pancreas may not be sufficient to eliminate the increased levels of glucose (1). In both cases, the outcome is increased levels of glucose in blood and circulating through the tissues, and if prolonged, the chronic exposure of cells to glucose results in pathological consequences.

One well-defined mechanism is through the activation of advanced glycation endproducts. Advanced glycation endproducts may form on all protein moieties and can be recognized by their receptors, which are also ubiquitously expressed on all cell types. As a result of recognition of the advanced glycation end-products through their complementary receptor, the receptor for advanced glycation end-products, a complex series of intracellular signaling pathways are activated and cell function is modified (114). This mechanism should be regarded as a part of the immune defense for the body when challenged by increased levels of blood glucose and the impact of glucose on tissues. As with other forms of inflammation-mediated tissue damage however, prolonged exposure results in the host’s own tissues being destroyed. Within the context of periodontal inflammation, activation of advanced glycation endproducts and expression of their receptors in periodontal tissues and cells have been demonstrated (74, 75, 115).

Other systemic inflammatory diseases such as hematological diseases could result in aggravation of periodontal inflammation (4). Systemic diseases caused by viruses or other microbes also affect periodontal diseases and inflammation (37). In the case of HIV-infection, periodontal pathologies result directly from the systemic immune deficiency, notably necrotizing periodontal diseases (137). Interestingly, chronic periodontitis is no more prevalent in HIV patients than non-HIV patients (35, 137), consistent with a hyper-rather than hypo-inflammatory contribution to periodontal tissue damage in chronic periodontitis.

Resolution of periodontal inflammation, tissue healing, and systemic impacts

Resolution of inflammation is a highly coordinated and active process. The process utilizes cells and various messenger molecules generated by cells to provide “stop signals” that lead to shut-down and clearance of inflammatory cells (118). Thus, inflammation includes both proinflammatory and proresolving mechanisms inherent to the body, where the host attempts to confine and/or eliminate the invaders and, when accomplished, actively resolves the response to limit self-damage (128). Hence, the body has the capacity to actively control inflammation. Pro-resolving mediators are readily generated in tissues and limit leukocyte trafficking directed into the inflamed site, reverse the cardinal signs of inflammation such as vasodilatation and vascular permeability, and coordinate the clearance of exhausted leukocytes, exudates, and fibrin; eventually leading to the restoration of function (102). All of these inflammation-resolving processes limit and prevent tissue injury and further progression of acute inflammation into chronic inflammation. If there is a failure of the host in its ability to eliminate the injury however, acute inflammation proceeds into a chronic phase and results in varying degrees of tissue injury (34). When tissue injury is mild and confined, necrotic cells are replaced by new cells through regeneration. If tissue damage is extensive, the process of healing is dominated by repair or scarring. When repair takes place, fibrin is not cleared rapidly and efficiently after the acute phase of inflammation and granulation tissue is formed from surrounding tissue compartments. Later phases of repair involve fibroblast-mediated collagen deposition, disappearance of vascular tissues and replacement of these areas by avascular and fibrotic scar tissue (73). Thus, in the context of resolution of inflammation, “acute resolution” leads to regeneration while “chronic resolution” results in repair and these terms are applicable to periodontal tissue healing. In periodontal disease pathogenesis, similar to other forms of host-mediated tissue injury, such as rheumatoid arthritis and asthma, chronic resolution also leads to ongoing tissue damage through continuous and recurring episodes of acute inflammation (70). Therefore, the induction and resolution of inflammation processes are concurrent phases in chronic inflammation and such pathologies should be defined as “continuous” inflammatory diseases rather than independent stages.

The pathogenesis of periodontitis is similar in nature to other inflammatory diseases in its pathways of progression. Attempts at elimination of infectious agents do not often represent a definitive therapy in periodontitis; necessitating the administration of more sophisticated biological treatment modalities. It was established in the 1980’s that modulation of the host response with cyclooxygenase inhibitors (61, 62, 97, 98, 132–135) was effective in halting the progression of periodontitis. However, the side effects of chronic long term use of cyclooxygenase inhibitors were significant creating a poor risk/benefit ratio, and the use of these drugs for the routine treatment of periodontitis was abandoned.

Animals do not have the capacity to fully desaturate fatty acids compared to plants. It is necessary to acquire certain polyunsaturated “essential” fatty acids derived from a plant source as a part of the animals’ diet. In humans, skin lesions, for example, occur when the diet lacks essential fatty acids (110). Linoleic acid-rich diets or essential fatty acid intake that consists of 1–2% of the total caloric requirement can reverse such pathological symptoms. In addition to the lack of dietary intake of essential fatty acids, abnormal metabolism of these molecules can also be associated with diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Crohn’s disease, cirrhosis, and alcoholism. A diet with high polyunsaturated fatty acid content is beneficial in decreasing serum cholesterol levels and low-density lipoproteins, while balanced consumption of essential fatty acids is important to prevent the risk of cardiovascular diseases associated with the high cholesterol levels (24, 25).

Lipid mediator pathways are very attractive targets for new therapeutic interventions because the lipids are: (1) small molecules (<500 Da molecular weight), (2) amenable to total organic synthesis, and (3) manufacturable with currently available pharmaceutical facilities. A “pro-resolution” pathway involves novel lipid mediators that possess endogenous anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving properties. Novel oxygenated products generated from the omega-3 fatty acid precursors eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) generated in the presence of aspirin that possess potent bioactions were identified in resolving inflammatory exudates, and similar structures were elucidated in tissues rich in docosahexaenoic acid. These molecules termed “resolvins” (resolution phase interaction products) and “docosatrienes” display potent anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory properties (116). Unlike other products identified earlier from omega-3 fatty acids that are similar in structure to eicosanoids but less potent or devoid of bioactions, the resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins evoke potent biological actions in vitro and in vivo. (116, 118).

Lipoxins, resolvins, protectins and maresins are novel families comprising a distinct chemical series of lipid-derived mediators, each with unique structures and apparent complementary anti-inflammatory properties and actions. The resolvins dampen from within, both inflammation and neutrophil-mediated injury, key culprits in many human diseases. It is likely that these compounds and their aspirin-triggered forms may play roles in other tissues and organs, since they are involved in physiological and pathological processes. In view of the important roles of their precursors, eicosapentanoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid in human biology and medicine, it is likely that these novel pathways and compounds are responsible, in part, for the beneficial impact of omega-3 essential fatty acids in complex systems and could be of use in periodontal treatment. A member of the resolvin family, resolvin D1, was shown to significantly enhance periodontal ligament fibroblast proliferation and wound closure as well as basic fibroblast growth factor release, highlighting the anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution actions of resolvins with upregulation of arachidonic acid-derived endogenous resolution pathways (lipoxins) (94).

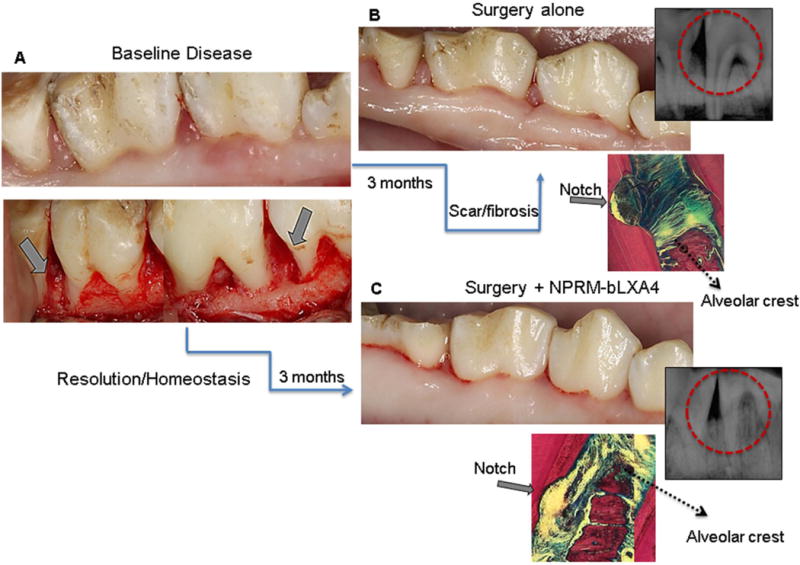

In this context, we reported on successful preventive and therapeutic impacts by resolvins (resolvin E1 and resolvin D1) on experimental periodontitis in rabbits as well as on their regenerative potential in the impaired periodontium in rabbits and minipigs (47, 48, 127). These novel nano-proresolving medicines containing a stable lipoxin A4 analog, benzo lipoxin A4, promoted regeneration of hard and soft tissues irreversibly lost to periodontitis in a minipig model of periodontitis (Fig. 3). The nano-proresolving medicines containing benzo lipoxin A4 dramatically reduced inflammatory cell infiltration into chronic periodontal disease sites surgically treated and dramatically increased new bone formation and regeneration of the periodontal organ (Fig. 4). These findings indicate that nano-proresolving medicines containing benzo lipoxin A4 as a mimetic of endogenous resolving mechanisms, with potent bioactions, offers a new therapeutic tissue-engineering approach for the treatment of chronic osteolytic inflammatory diseases.

Fig. 3. Nano-proresolving medicines containing benzo lipoxin A4 results in regeneration of the periodontal organ.

A. Chronic periodontal disease was induced in miniature pigs after creation of surgical defects by wire ligatures over 3 months. All defects were treated with surgical debridement and randomly received 1) empty nano-proresolving medicines, 2) nano-proresolving medicines loaded with benzo lipoxin A4, 3) benzo lipoxin A4 alone and 4) no additional treatment. B. The defects treated with surgical debridement alone healed with fibrosis and scarring; radiography and un-decalcified histology confirmed that healing was without bone formation. C. Treatment with either the nano-proresolving medicines loaded with benzo lipoxin A4 or benzo lipoxin A4 (not shown) alone resulted in clinically healthy tissues without fibrosis or scarring. Bone regenerated at the defect site was confirmed by histological and radiological assessments. Red circles depict the defect area on radiological images.

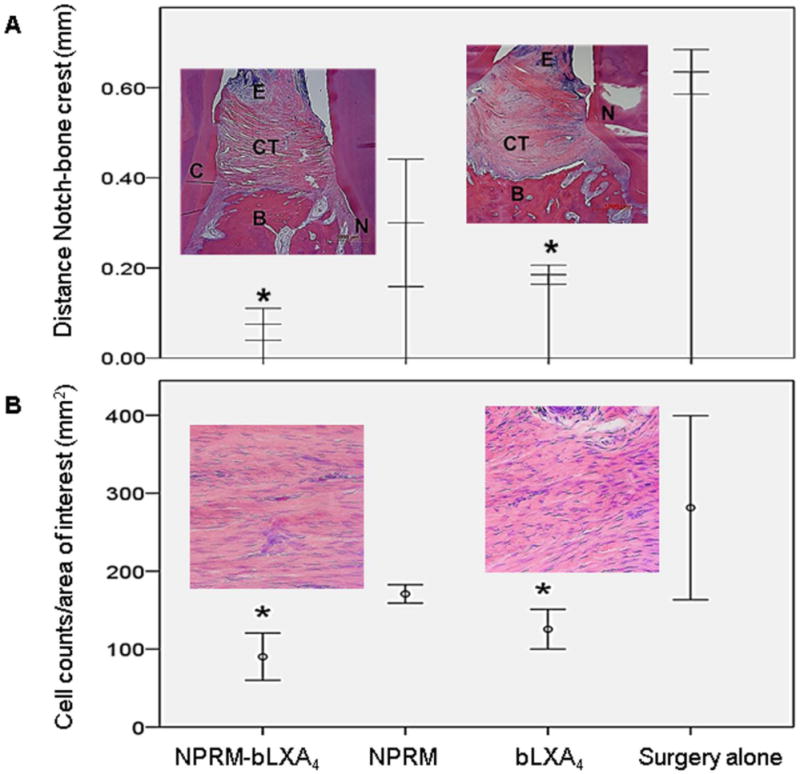

Fig. 4. Histology confirms nano-proresolving medicines containing benzo lipoxin A4 regeneration of the periodontal organ.

A- nano-proresolving medicines loaded with benzo lipoxin A4 and benzo lipoxin A4 alone induce regeneration of new bone, new connective tissue attachment and new cementum; quantified as distance from the bone crest to the root notch created at time of surgery (*p<0.05, N=4/group). N=notch, CT=connective tissue, B=bone, E=epithelium. B- Inflammatory cell counts were determined using Image J. Nano-proresolving medicines loaded with benzo lipoxin A4 and benzo lipoxin A4 alone significantly limit inflammatory cell infiltrate. (* p<0.05, N=4/group).

Considering the proposed causal relationships between periodontal disease and other systemic inflammatory diseases, the treatment outcomes of one disease should improve or reduce the risk for another in order to prove causality in humans. Clinical trials were therefore conducted to test the impact of periodontal treatment on glycemic control, circulating inflammatory markers, cardiovascular markers including C-reactive protein, serum plasminogen, endothelial dysfunction and many other markers of inflammatory diseases (21, 32, 71). Although the results of these studies are controversial due to unstandardized study planning, patient populations, selection criteria and short-term follow-up, randomized clinical trials consistently demonstrate that mechanical periodontal therapy associates with approximately a 0.4% reduction in glycated hemoglobin at three months, a clinical impact equivalent to adding a second drug to a pharmacological regime for diabetes (15). While there is moderate evidence that periodontal treatment reduces systemic inflammation, it was shown that periodontal therapy can result in reductions in C-reactive protein and oxidative stress leading to improvements of surrogate clinical and biochemical measures of vascular endothelial function (126).

In the context of pro-resolution mediators, lipoxins and resolvins, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases represent a unique disease model where the impact of treatment of a local inflammation, periodontitis, on the outcome of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases may be measured. It has been shown that lipoxin A4 attenuates adipocyte inflammation and reduces secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha in diabetic murine models (10). A recent study (52) from our laboratory with a murine model of type 2 diabetes (db/db mice) and transgenic mice, overexpressing resolvin E1 receptor, (ChemR23, ERV1), clearly demonstrated that resolvin E1 increased neutrophil phagocytosis of P. gingivalis in wild type mice but had no impact on type 2 diabetes mice. In both mice overexpressing resolvin E1 receptor and type 2 diabetes mice overexpressing resolvin E1 receptor however, phagocytosis was significantly increased. Moreover, dorsal air pouch studies revealed that resolvin E1 decreases neutrophil influx into the pouch and increases neutrophil phagocytosis of P. gingivalis in the animals overexpressing resolvin E1 receptor in addition to reducing cutaneous fat deposition and in macrophage infiltration. These results suggest that resolvin E1 rescues impaired neutrophil phagocytosis in type 2 diabetes mice overexpressing resolvin E1 receptor. In an in vitro study of neutrophil function, N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine and tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulation, demonstrated dramatic reductions in superoxide anion production when the cells from type 2 diabetes subjects and type 2 diabetes subjects with periodontal disease were treated with lipoxin A4 and resolvin E1. Both lipid mediators showed comparable results in dampening the pro-inflammatory actions of neutrophils upon stimulation (unpublished data).

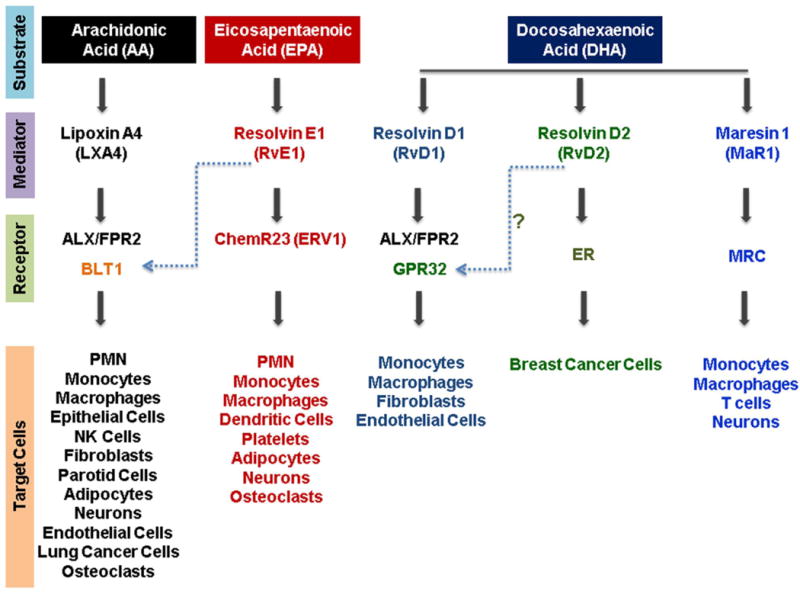

The actions of lipoxins and resolvins support their potential use in inflammatory diseases. For example, in a sepsis model (cecal ligation and puncture), resolvins reduced the local and systemic bacterial burden, cytokine production and neutrophil accumulation, and increased peritoneal mononuclear cell recruitment, macrophage phagocytosis and mouse survival (123). Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the vessel wall. Ho et al (55) recently demonstrated that plasma levels of aspirin-triggered lipoxins were significantly lower in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease than in healthy volunteers suggesting an inflammation-resolution deficit that may play a significant role in the development of atherosclerosis. Importantly, receptors for aspirin-triggered lipoxin and resolvin E1 (ALX and ChemR23, respectively) were identified in human vascular smooth muscle cells. The results of this study demonstrated that stimulatory lipid mediators confer a protective phenotypic switch in vascular smooth muscle cells and can provide novel functions in the regulation of vascular biology. In parallel, the data from our laboratory demonstrated that resolvin E1, used as an oral/topical agent, was capable of diminishing atherogenesis in an accelerated-atherosclerosis model in rabbits in both the presence and absence of periodontal inflammation (46). This study specifies that endogenous mediators of resolution of inflammation have potential to reduce the burden of local inflammatory disease on systemic diseases and at the same time can directly interact with tissue and cell specific receptors to activate the tissue’s resolution pathways and facilitate a return to hemostasis and tissue healing (Fig 5). To date, multiple receptors and target cells have been identified with various functions for the lipoxins, resolvins, and maresins (Fig. 6) demonstrating an active recognition of these resolution-phase lipid mediator classes by host cells. The data suggests that some of these “resolvers” of inflammation act on a large variety of cells whereas some are more limited in their activation; the field is expanding. For example, the newest member of this class of molecules, maresin 1 acts through the mannose receptor C on T cells, macrophages and neurons, opening new avenues for research (88). Likewise, recent work demonstrated that estrogen receptors on breast cancer cells mediate the functions of resolvin D2 (2). The nomenclature and designations of receptors and their ligands are continuously evolving (6).

Fig. 5. Outcome of treatment with oral topical resolvin E1 in periodontitis and atherosclerosis in rabbits.

A. Treatment with resolvin E1 resulted in apparent prevention from periodontal disease induction; this was also demonstrated by histological assessments (resolvin E1-treated) compared to vehicle treated animals (not shown). En face evaluation of aortas dissected from animals treated with vehicle (n=5) or resolvin E1 (n=5) revealed significant protection form atherosclerotic plaque development in animals treated with resolvin E1. B. Histological assessments of hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome stained sections of aortas from groups treated with vehicle and resolvin E1 demonstrated significant changes in aorta layers where the intima and media thickness was close to normal healthy aorta. C. Bar graphs show quantification of percent lipid covered area and intima/media ratio. (*p<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated group. Red arrow depicts the fibrous cap in vehicle-treated group in Masson’s trichrome stained sections. D. As shown in Fig. 2F, local inflammation induced up-regulation of C-reactive protein in serum from cholesterol-fed rabbits. Resolution of local inflammation, periodontal disease, by resolvin E1 treatment also reduced the systemic levels of C-reactive protein, an acute phase pro-inflammatory cytokine, which is accepted as a marker for atherosclerosis. (*p<0.05; n=5/group). TM: tunica media; TI: tunica intima; TA: tunica adventitia; L: lumen; SM: smooth muscle; N: necrotic core; F: foam cells

Fig. 6. Resolution-agonist Lipid mediators.

Arachidonic acid (an omega-6 fatty acid) and omega-3 fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are the substrates for lipoxins, resolvins and maresins. These lipid mediators act as direct agonists through specific receptors located on various cell types and modulate the tissue-specific inflammatory conditions.

Conclusions

Inflammation comprises a series of events that lead to a host response against trauma and microbial invasion, results in the liquefaction of surrounding tissues to prevent microbial metastasis, and eventually healing of injured tissue compartments. Periodontal diseases are inflammatory processes, in which microbial etiological factors induce a series of host responses that mediate an inflammatory cascade of events in an attempt to protect and heal the periodontal tissues. However, the progression of periodontal disease and its commonality with other systemic disorders such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes is based on the inflammatory events underlying its pathogenesis. Studies have shown that in addition to the “on” signals that initiate the inflammatory events, periodontal tissues are capable of generating “off” or “stop” signals as checkpoint controls in inflammation. These control mechanisms are specific pro-resolving cellular and biochemical circuits that have evolved to activate resolution, thus limiting uncontrolled dissemination of inflammation. We have already identified several common inflammatory pathways of pathogenesis in chronic periodontitis and diabetes where neutrophils play an important role as an inducer in conveying the inflammatory processes (65). These neutrophil-mediated pathways, which could very well be shared by the other phagocytes (such as monocytes) and cells of the adaptive immune system, could be used to control and manage inflammatory processes (39). Thus, during regulation of phagocyte-mediated inflammation, in addition to the traditional pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, endogenous lipid mediators (lipoxins and resolvins) represent a pro-resolution phase. Blockage of pro-inflammatory pathways could be accomplished not only by immune modulation therapy (e.g. anti-tumor necrosis-alpha therapy), bisphosphonates, tetracyclines (e.g. chemically modified tetracyclines), or activation of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase, all of which have side effects or short-comings, but also through shutting down the pro-inflammatory cellular and molecular circuits endogenously by resolution-phase lipid mediators. The available data and the results of ongoing studies demonstrate a new treatment concept where natural pathways of resolution of inflammation could be employed to limit inflammation and promote healing and regeneration with minor risk of side effects.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this review was partly supported by USPHS National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grants (DE18917 to H. Hasturk and DE 020906 to A. Kantarci)

Contributor Information

Hatice Hasturk, Email: hhasturk@forsyth.org, The Forsyth Institute, Department of Applied Oral Sciences, Center for Periodontology, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA. Phone: 617-892-8499; Fax: 617-892-8505.

Alpdogan Kantarci, Email: akantarci@forsyth.org, The Forsyth Institute, Department of Applied Oral Sciences, Center for Periodontology, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA. Phone: 617-892-8530.

References

- 1.Ahlqvist E, van Zuydam NR, Groop LC, McCarthy MI. The genetics of diabetic complications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:277–287. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Zaubai N, Johnstone CN, Leong MM, Li J, Rizzacasa M, Stewart AG. Resolvin D2 supports MCF-7 cell proliferation via activation of estrogen receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;351:172–180. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.214403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen EM, Matthews JB, DJ OH, Griffiths HR, Chapple IL. Oxidative and inflammatory status in Type 2 diabetes patients with periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:894–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angst PD, Dutra DA, Moreira CH, Kantorski KZ. Periodontal status and its correlation with haematological parameters in patients with leukaemia. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:1003–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armitage GC, Robertson PB. The biology, prevention, diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases: scientific advances in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(Suppl 1):36S–43S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Back M, Powell WS, Dahlen SE, Drazen JM, Evans JF, Serhan CN, Shimizu T, Yokomizo T, Rovati GE. Update on leukotriene, lipoxin and oxoeicosanoid receptors: IUPHAR Review 7. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:3551–3574. doi: 10.1111/bph.12665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagchi A, Herrup EA, Warren HS, Trigilio J, Shin HS, Valentine C, Hellman J. MyD88-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways in synergy, priming, and tolerance between TLR agonists. J Immunol. 2007;178:1164–1171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahrani-Mougeot FK, Paster BJ, Coleman S, Ashar J, Knost S, Sautter RL, Lockhart PB. Identification of oral bacteria in blood cultures by conventional versus molecular methods. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:720–724. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastos AS, Graves DT, Loureiro AP, Rossa Junior C, Abdalla DS, Faulin Tdo E, Olsen Camara N, Andriankaja OM, Orrico SR. Lipid peroxidation is associated with the severity of periodontal disease and local inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1353–1362. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borgeson E, McGillicuddy FC, Harford KA, Corrigan N, Higgins DF, Maderna P, Roche HM, Godson C. Lipoxin A4 attenuates adipose inflammation. FASEB J. 2012;26:4287–4294. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-208249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosshardt DD, Lang NP. The junctional epithelium: from health to disease. J Dent Res. 2005;84:9–20. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boylan MR, Khalili H, Huang ES, Michaud DS, Izard J, Joshipura KJ, Chan AT. A prospective study of periodontal disease and risk of gastric and duodenal ulcer in male health professionals. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5:e49. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bretz WA, Weyant RJ, Corby PM, Ren D, Weissfeld L, Kritchevsky SB, Harris T, Kurella M, Satterfield S, Visser M, Newman AB. Systemic inflammatory markers, periodontal diseases, and periodontal infections in an elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1532–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2014;64:57–80. doi: 10.1111/prd.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapple IL, Genco R, working group 2 of the joint EFPAAPw Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Periodontol. 2013;84:S106–112. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapple IL, Socransky SS, Dibart S, Glenwright HD, Matthews JB. Chemiluminescent assay of alkaline phosphatase in human gingival crevicular fluid: investigations with an experimental gingivitis model and studies on the source of the enzyme within crevicular fluid. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:587–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapple IL, Wilson NH. Manifesto for a paradigm shift: periodontal health for a better life. Br Dent J. 2014;216:159–162. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janeway Charles A, T P, Walport Mark, Shlomchik Mark. The Components of the Immune System. In: Janeway Charles A, Travers Paul, Walport Mark, Shlomchik Mark., editors. Immunobiology. 5. 2001. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou HH, Yumoto H, Davey M, Takahashi Y, Miyamoto T, Gibson FC, 3rd, Genco CA. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbria-dependent activation of inflammatory genes in human aortic endothelial cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5367–5378. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5367-5378.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen RA, Donaldson JA. The study of dental history. Int Dent J. 1967;17:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corbella S, Francetti L, Taschieri S, De Siena F, Fabbro MD. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:502–509. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotran RSKV, Collins T, editors. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. W.B. Saunders Co; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crasta K, Daly CG, Mitchell D, Curtis B, Stewart D, Heitz-Mayfield LJ. Bacteraemia due to dental flossing. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das UN. Essential fatty acids as possible mediators of the actions of statins. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2001;65:37–40. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das UN. Is obesity an inflammatory condition? Nutrition. 2001;17:953–966. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demmer RT, Desvarieux M, Holtfreter B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Wallaschofski H, Nauck M, Volzke H, Kocher T. Periodontal status and A1C change: longitudinal results from the study of health in Pomerania (SHIP) Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1037–1043. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deshpande RG, Khan MB, Genco CA. Invasion of aortic and heart endothelial cells by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5337–5343. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5337-5343.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dietrich T, Sharma P, Walter C, Weston P, Beck J. The epidemiological evidence behind the association between periodontitis and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2013;84:S70–84. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.134008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding Y, Kantarci A, Badwey JA, Hasturk H, Malabanan A, Van Dyke TE. Phosphorylation of pleckstrin increases proinflammatory cytokine secretion by mononuclear phagocytes in diabetes mellitus. J Immunol. 2007;179:647–654. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dowsett SA, Archila L, Foroud T, Koller D, Eckert GJ, Kowolik MJ. The effect of shared genetic and environmental factors on periodontal disease parameters in untreated adult siblings in Guatemala. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1160–1168. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.10.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engebretson S, Chertog R, Nichols A, Hey-Hadavi J, Celenti R, Grbic J. Plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in patients with chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engebretson SP, Hyman LG, Michalowicz BS, Schoenfeld ER, Gelato MC, Hou W, Seaquist ER, Reddy MS, Lewis CE, Oates TW, Tripathy D, Katancik JA, Orlander PR, Paquette DW, Hanson NQ, Tsai MY. The effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on hemoglobin A1c levels in persons with type 2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2523–2532. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Genco RJ, Loe H. The role of systemic conditions and disorders in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 1993;2:98–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1993.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilroy DW, Lawrence T, Perretti M, Rossi AG. Inflammatory resolution: new opportunities for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:401–416. doi: 10.1038/nrd1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goncalves LS, Goncalves BM, Fontes TV. Periodontal disease in HIV-infected adults in the HAART era: Clinical, immunological, and microbiological aspects. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:1385–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gradmann C. A spirit of scientific rigour: Koch’s postulates in twentieth-century medicine. Microbes Infect. 2014;16:885–892. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grande SR, Imbronito AV, Okuda OS, Pannuti CM, Nunes FD, Lima LA. Relationship between herpesviruses and periodontopathogens in patients with HIV and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1442–1452. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graves DT, Kayal RA. Diabetic complications and dysregulated innate immunity. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1227–1239. doi: 10.2741/2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gronert K, Kantarci A, Levy BD, Clish CB, Odparlik S, Hasturk H, Badwey JA, Colgan SP, Van Dyke TE, Serhan CN. A molecular defect in intracellular lipid signaling in human neutrophils in localized aggressive periodontal tissue damage. J Immunol. 2004;172:1856–1861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbiology of periodontal diseases: introduction. Periodontol 2000. 2005;38:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hajishengallis G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hale GC. Focal Infection and Its Relation to Disease. Can Med Assoc J. 1931;24:537–539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han YW, Redline RW, Li M, Yin L, Hill GB, McCormick TS. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2272–2279. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2272-2279.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han YW, Wang X. Mobile microbiome: oral bacteria in extra-oral infections and inflammation. J Dent Res. 2013;92:485–491. doi: 10.1177/0022034513487559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harper DS, Robinson PJ. Correlation of histometric, microbial, and clinical indicators of periodontal disease status before and after root planing. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:190–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hasturk H, Abdallah R, Kantarci A, Nguyen D, Giordano N, Hamilton J, Van Dyke TE. Resolvin E1 Attenuates Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation in Diet and Inflammation-Induced Atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1123–1133. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Goguet-Surmenian E, Blackwood A, Andry C, Serhan CN, Van Dyke TE. Resolvin E1 regulates inflammation at the cellular and tissue level and restores tissue homeostasis in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:7021–7029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.7021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Ohira T, Arita M, Ebrahimi N, Chiang N, Petasis NA, Levy BD, Serhan CN, Van Dyke TE. RvE1 protects from local inflammation and osteoclast-mediated bone destruction in periodontitis. FASEB J. 2006;20:401–403. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4724fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE. Oral inflammatory diseases and systemic inflammation: role of the macrophage. Front Immunol. 2012;3:118. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE. Paradigm shift in the pharmacological management of periodontal diseases. Front Oral Biol. 2012;15:160–176. doi: 10.1159/000329678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayashi C, Gudino CV, Gibson FC, 3rd, Genco CA. Review: Pathogen-induced inflammation at sites distant from oral infection: bacterial persistence and induction of cell-specific innate immune inflammatory pathways. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:305–316. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herrera BS, Hasturk H, Kantarci A, Freire MO, Nguyen O, Kansal S, Van Dyke TE. Impact of resolvin E1 on murine neutrophil phagocytosis in type 2 diabetes. Infect Immun. 2015;83:792–801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02444-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hillam C. James Blair (1747–1817), provincial dentist. Med Hist. 1978;22:44–70. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300031744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirschfeld J, Kawai T. Oral inflammation and bacteremia: implications for chronic and acute systemic diseases involving major organs. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets. 2015;15:70–84. doi: 10.2174/1871529x15666150108115241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ho KJ, Spite M, Owens CD, Lancero H, Kroemer AH, Pande R, Creager MA, Serhan CN, Conte MS. Aspirin-triggered lipoxin and resolvin E1 modulate vascular smooth muscle phenotype and correlate with peripheral atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2116–2123. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holtfreter B, Empen K, Glaser S, Lorbeer R, Volzke H, Ewert R, Kocher T, Dorr M. Periodontitis is associated with endothelial dysfunction in a general population: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ide M, Linden GJ. Periodontitis, cardiovascular disease and pregnancy outcome–focal infection revisited? Br Dent J. 2014;217:467–474. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jagannathan M, Hasturk H, Liang Y, Shin H, Hetzel JT, Kantarci A, Rubin D, McDonnell ME, Van Dyke TE, Ganley-Leal LM, Nikolajczyk BS. TLR cross-talk specifically regulates cytokine production by B cells from chronic inflammatory disease patients. J Immunol. 2009;183:7461–7470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jagannathan M, McDonnell M, Liang Y, Hasturk H, Hetzel J, Rubin D, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE, Ganley-Leal LM, Nikolajczyk BS. Toll-like receptors regulate B cell cytokine production in patients with diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1461–1471. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1730-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jain A, Batista EL, Jr, Serhan C, Stahl GL, Van Dyke TE. Role for periodontitis in the progression of lipid deposition in an animal model. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6012–6018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.6012-6018.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeffcoat MK, Reddy MS, Moreland LW, Koopman WJ. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on bone loss in chronic inflammatory disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;696:292–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb17164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jeffcoat MK, Williams RC, Reddy MS, English R, Goldhaber P. Flurbiprofen treatment of human periodontitis: effect on alveolar bone height and metabolism. J Periodontal Res. 1988;23:381–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1988.tb01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE. Host-mediated resolution of inflammation in periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:144–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kantarci A, Oyaizu K, Van Dyke TE. Neutrophil-mediated tissue injury in periodontal disease pathogenesis: findings from localized aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:66–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karima M, Kantarci A, Ohira T, Hasturk H, Jones VL, Nam BH, Malabanan A, Trackman PC, Badwey JA, Van Dyke TE. Enhanced superoxide release and elevated protein kinase C activity in neutrophils from diabetic patients: association with periodontitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:862–870. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1004583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kinane DF, Lappin DF. Immune processes in periodontal disease: a review. Ann Periodontol. 2002;7:62–71. doi: 10.1902/annals.2002.7.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kinane DF, Riggio MP, Walker KF, MacKenzie D, Shearer B. Bacteraemia following periodontal procedures. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:708–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kolattukudy PE, Niu J. Inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CCR2 pathway. Circ Res. 2012;110:174–189. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kolb H, Mandrup-Poulsen T. The global diabetes epidemic as a consequence of lifestyle-induced low-grade inflammation. Diabetologia. 2010;53:10–20. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kornman KS, Page RC, Tonetti MS. The host response to the microbial challenge in periodontitis: assembling the players. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:33–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1997.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koromantzos PA, Madianos P. Nonsurgical periodontal treatment can improve HbA1c values in a Mexican-American population of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) and periodontal disease (PD) J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14:193–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kramer JM, Gaffen SL. Interleukin-17: a new paradigm in inflammation, autoimmunity, and therapy. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1083–1093. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lalla E, Lamster IB, Feit M, Huang L, Schmidt AM. A murine model of accelerated periodontal disease in diabetes. J Periodontal Res. 1998;33:387–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1998.tb02335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lalla E, Lamster IB, Schmidt AM. Enhanced interaction of advanced glycation end products with their cellular receptor RAGE: implications for the pathogenesis of accelerated periodontal disease in diabetes. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:13–19. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leigh NJ, Nelson JW, Mellas RE, Aguirre A, Baker OJ. Expression of resolvin D1 biosynthetic pathways in salivary epithelium. J Dent Res. 2014;93:300–305. doi: 10.1177/0022034513519108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]