Abstract

Core–shell magnetic nanostructures (MNS) such as Fe3O4–SiOx, are being explored for their potential applications in biomedicine, such as a T2 (dark) contrast enhancement agent in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Herein, we present the effect of silica shell thickness on its r2 relaxivity in MRI as it relates to other physical parameters. In this effort initially, monodispersed Fe3O4 MNS (nominally 9 nm size) were synthesized in organic phase via a simple chemical decomposition method. To study effect of shell thickness of silica of Fe3O4–SiOx core shell on r2 relaxivity, the reverse micro-emulsion process was used to form silica coating of 5, 10 and 13 nm of silica shell around the MNS, while polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane was used to form very thin layer on the surface of MNS; synthesized nanostructures were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high resolution TEM (HRTEM), superconducting quantum interference device magnetometry and MRI. Our observation suggests that, with increase in thickness of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell nanostructure, r2 relaxivity decreases. The decrease in relaxivity could be attributed to increased distance between water molecules and magnetic core followed by change in the difference in Larmor frequencies (Dx) of water molecules. These results provide a rational basis for optimization of SiOx-coated MNS for biomedical applications.

Keywords: Magnetic nanoparticles, T2 contrast agents, Core–shell nanostructures, Relaxivity, MRI

Introduction

Synthesis and characterization of nanoscale magnetic materials is important because of their size and shape dependent properties for potential technological applications in many fields (Laurent et al. 2008). At this length scale, magnetic nanostructures (MNS) exhibit unique ability to respond at molecular level, that are being explored for targeted drug delivery (Sun et al. 2008), diagnostics (Rosi and Mirkin 2005), magnetic separation (Molday and Mackenzie 1982), as MRI contrast agent (Lee et al. 2007), thermal responsive drug carriers (Schmidt 2007) and as heat mediator in thermal activation therapy (Prasad et al. 2007; Jordan et al. 1997), to name few. These applications are possible due to the super-paramagnetic behavior of MNS at nanoscale dimension.

Tailored size, shape, stable colloidal dispersion in buffer, biocompatibility, non-toxic nature, non-immunogenicity, and long half-life for fluidic circulation are some of the important criteria that are essential for MNS to be efficient contrast agent. To accomplish these requirements surface modification of these MNS plays very important role. Due to stringent synthesis conditions such high temperature and reaction in organic medium, MNS cannot be functionalized directly during the synthesis process; therefore, post-synthesis processes are often required. Surface modification of MNS gives several advantages such as passivation, biocompatibility and fluidic stabilization in colloidal form. Since surface of the silica can react with various coupling agents with specific functional groups, it is one of the preferred materials for coating MNS (Ulman 1996). Magnetic nanoparticles with silica shell have potential applications in bioimaging as well as in drug delivery. Hence, it is important to study effect of silica shell thickness of Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell nanostructures on MRI contrast.

The reverse micro-emulsion process is one of the most common processes used for the silica shell formation. In this process, thickness of the shell can be controlled by various parameters such as time, temperature, concentration of Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), etc. (Zhang et al. 2008); however; other routes of synthesis also demonstrate excellent control over thickness of silica coating on iron oxide MNS (Vogt et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2009).

Several research groups have demonstrated the efficacy of the MNS as contrast agent, and its dependence on composition, size, shape and coating of the nanostructures (Joshi 2013). Recently, it was reported that the r2 values of the Fe3O4 MNS synthesized by amine-stabilized aqueous method were 80–232 mM−1s−1 (Aslam et al. 2007). In addition, Jun et al. (2005) reported the size-dependent MR properties of water soluble MFe2O4 nanostructures. The same group compared various compositions of metal ferrites (Jang et al. 2009). Previous work from our laboratory has shed light on size and shape dependence of CoFe2O4 on its MRI relaxivity (Joshi et al. 2009). Further, Schultz-Sikma et al. (2011) reported effect metal ion leaching in MFe2O4–SiOx (M = Co, Fe) MNS on their MRI contrast emphasizing importance of chemical stability in designing MRI contrast agents. In another report, Duan et al. (2008) indicated the dependence of proton relaxivity on particle size, surface coating of polymer thickness, hydrophilicity and the co-ordination chemistry of inner capping ligands. Their findings show that MNS coated with hydrophilic ligands yield high proton relaxivity, whereas MNS coated with oleic acid and ampiphylic polymers exhibit strongest dependence on particle size. Laconte et al. (2007) demonstrated PEG chain length dependent r2 relaxivity in PEG-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Similarly, Hu et al. (2009) reported higher r2 relaxivity for PEG capped Fe3O4 over DEG-capped Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Thus, these reports demonstrate that hydrophilicity of the surrounding medium significantly affects the r2 relaxivity. Recently Pinho et al. (2010) studied MRI relaxivity of γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 nanoparticles and shown that viability and mitochondrial dehydrogenase expression of the microglial cells is not sensitive to the vesicular load with these core shell nanoparticles, thus, can be used for biological imaging. In spite of many potential technological applications of Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS (synthesized by reverse micro-emulsion process), the effect of hydrophilic nature of amorphous silica shell thickness in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS on MRI contrast has not been investigated in detail, which is presented in this contribution.

To understand the effect of silica shell thickness in Fe3O4–SiOx core shell structures, four different thicknesses of silica shells were formed around Fe3O4 magnetic core. Initially Fe3O4 were synthesized in organic phase. Three different thicknesses of silica shell i.e., 5 ± 1, 10 ± 1 and 13 ± 1 nm, were then formed by reverse micro-emulsion process. Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane (POSS) was used as capping agent on bare Fe3O4 MNS because it is known to form monolayer (thickness ~1 nm) while capping inorganic nanoparticles and gives excellent dispersion in aqueous phase (Carroll et al. 2004; Frankamp et al. 2006). After coating of silica shells, all the MNS disperse very well in water, with stability for several weeks. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high resolution TEM (HRTEM) were used to characterize the size and morphology of the MNS while superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) was used to measure the magnetic properties. The r2 relaxivity measurements were performed with commercial Siemens Verio 3.0 T MR System.

Experimental methods and materials

Iron (III) chloride hexahydrate, sodium oleate, 1-octdecene, polyoxyethylene (5) nonylphenylether, branched (Igepal CO-520), POSS, ammonium hydroxide, hexane, and cyclo hexane were obtained from sigma Aldrich and used without any modification. Oleic acid stabilized Fe3O4 was synthesized as reported elsewhere (Park et al. 2004).

Synthesis of iron oleate complex

In a typical experiment, 10.8 g of iron chloride hexahydrate and 36.5 g of sodium oleate were dissolved in the mixture of 80-ml ethanol, 60 ml of water, and 140 ml of hexane. This mixture was stirred for 4 h at 62 °C. Transfer of iron ions into organic phase was observed resulting into dark brown iron oleate complex. Organic layer was washed three times with water and solvent was evaporated to obtain sticky iron oleate complex.

Synthesis of Fe3O4 MNS

To obtain 9 nm Fe3O4 MNS, 18 g of iron oleate complex and 2.35 g of oleic acid were dissolved in the 100 g of octadecene. The reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was then heated to 320 °C and kept for 25 min. The mixture was then cooled down to room temperature, and ethanol was added to precipitate the MNS.

Synthesis of POSS-coated Fe3O4 MNS

10 mg (in hexane) and 200 mg of TMA-POSS (in 1 ml water) were mixed. This reaction mixture was purged with nitrogen, capped, and stirred vigorously for 48 h which transfers particles from organic phase to the aqueous phase. The layers were carefully separated, and dialyzed against deionized/distilled water (24 h) to remove free POSS (Carroll et al. 2004; Frankamp et al. 2006).

Synthesis of core shell structures

9-nm Fe3O4 MNS were coated with 5, 10, and 13 nm thickness of silica shell by base-catalyzed silica formation from tetraorthosilicate in water in oil emulsion. Typically, 1 ml of Igepal CO-520 was mixed with cyclohexane under vigorous stirring conditions. Fe3O4 MNS were dispersed in cyclohexane at a concentration of 1.25 mg/mL and then 2 ml were added slowly into the cyclohexane/Igepal solution followed by drop wise addition of 140 μl of 30 % ammonium hydroxide. The resulting mixture stirred well for 40 min. For thickness of 5 nm silica shell, 90 μl of TEOS while for 10 and 13 nm of shell thickness 270 μl of TEOS added to the above mixture. For 5 and 10 nm silica shell thickness, reaction mixture was stirred for 2 days while for 13 nm shell thickness, reaction mixture was stirred for 4 days. The precipitate with ethanol was collected by centrifugation at10,000 rpmandparticleswere washedseveral timesby redispersing in ethanol. Washed precipitate was dispersed in deionized water (Schultz-sikma et al. 2011).

Material characterization

Hitachi HF-8100 and JEOL 2100F Transmission Electron Microscopes were used to characterize the MNS. Elemental maps were collected using energy X-ray dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) in the scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mode using a ~1 nm probe size to further confirm the composition of the core shell structures. The nanostructure size was determined by the statistical averaging using Digital Micrograph 3.4. SQUID analyzer (Quantum Design, MPMS, San Diego, CA) was used to obtain the hysteresis of the samples at room temperature (magnetic field range—1.59 × 106–1.59 × 106 A/m i.e., −20,000 to 20,000 oersted). For relaxivity measurements, the MNS were dispersed in water and diluted to concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.3 mM of Fe ions. A Siemens Verio 3.0 T MR System was used to scan the nanostructure solutions using multiple-echo-spin-echo sequence to determine T2 values.

Results and discussion

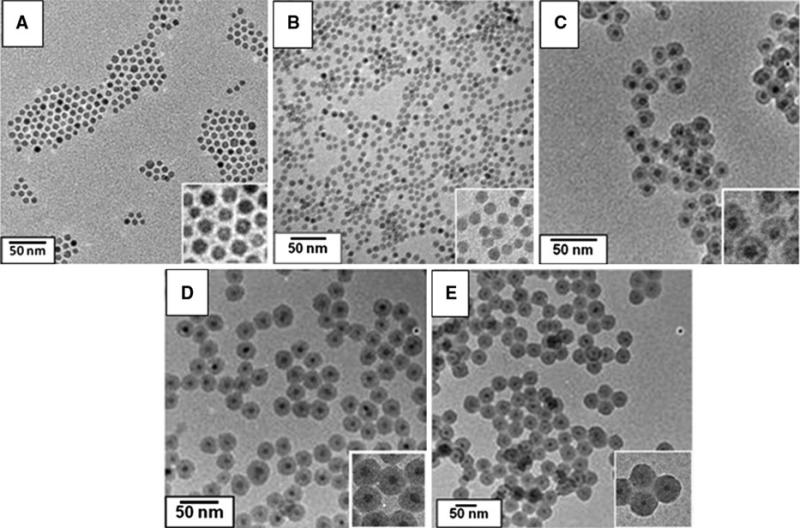

For all core–shell structure investigated here, 9-nm Fe3O4 oleic acid-capped MNS from the same batch have been used as the magnetic core. The surface morphology and silica shell thickness of various MNS were analyzed with TEM and HRTEM. Figure 1A, B shows TEM micrograph of as prepared MNS in organic medium and MNS coated with POSS in aqueous phase. No change was apparent in the size of the MNS after phase transfer, this suggests very thin layer (~1 nm) of POSS coating on the surface of MNS. Figure 1C–E represents 9 nm Fe3O4 with 5, 10, and 13 nm silica shell thickness. It indicates that as the amount of TEOS and time of reaction increases shell thickness increases; however, no morphological changes have been observed in core Fe3O4 MNS.

Fig. 1.

Synthesized Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS with varying shell thicknesses. A As prepared magnetic MNS, B POSS coated, C 5 nm, D 10 nm, and E 13 nm MNS. Inset shows magnified images of the same TEM micrographs

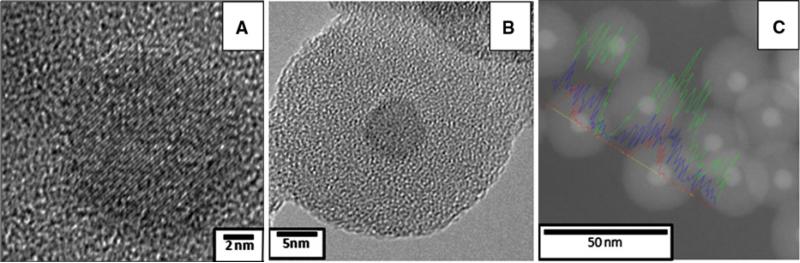

Figure 2 shows HRTEM images of A) POSS-coated Fe3O4 nanostructures B) Fe3O4–SiOx core shell MNS and Fig. 2C is STEM image with elemental mapping of Fe3O4–SiOx (10-nm silica shell thickness) MNS. In Fig. 2A, interplaner distance is 0.21 nm in POSS-coated Fe3O4 MNS which matches with 400 plane of Fe3O4 MNS (Hui et al. 2008). Figure 2B reveals that silica is uniformly coated around Fe3O4 and amorphous in nature while Fig. 2C shows elemental mapping of Fe3O4–SiOx MNS, which proves that no magnetic impurities were present in the silica shell coated around Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell nanostructures.

Fig. 2.

HRTEM image of A POSS-coated 9-nm Fe3O4 MNS, B Fe3O4–SiOx core shell (thickness 10 nm) MNS, and C STEM image with elemental mapping of nanostructure, red line, blue line and green line represents Fe, Si, and O, respectively. (Color figure online)

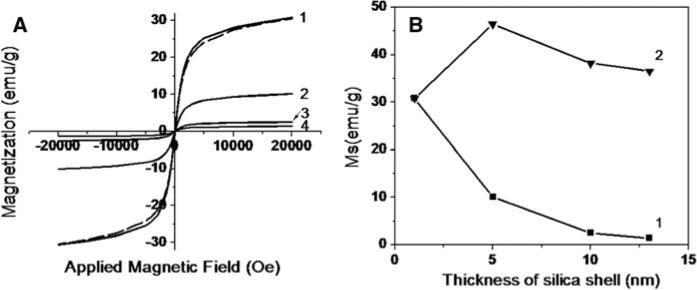

The aqueous MNS were freeze dried to convert it into powder form for magnetic measurements. Figure 3A shows field dependent magnetization measurements of various thicknesses of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS at room temperature. While Fig. 3B demonstrates variation in saturation magnetization values with respect to thickness of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS. Ms values with respective thickness of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS are summarized in Table 1. All MNS reported here exhibit superparamagnetism. Figure 3B 1 and Table 1 show that as the thickness of the silica shell increases Ms (emu/g) values decreases very rapidly. This is due to the amorphous silica content per unit volume increases with cube of the radius of MNS (volume of sphere = (4/3)*π*r3).

Fig. 3.

A Magnetization (M) curve for Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS of various thicknesses as follows, dotted line indicates MNS powder in organic phase, 1) POSS-coated MNS, 2) 5 nm, 3) 10 nm, 4) 13 nm silica shell thickness while core of the MNS are same i.e., 9 nm. B 1 Saturation magnetization versus thickness of silica shell of MNS. Measurements were performed at room temperature 2. Theoretically calculated saturation magnetization of MNS in emu/g after subtraction of theoretically calculated mass of silica shell from experimentally measured values of emu/g values of the core shell nanostructures

Table 1.

Saturation magnetization of magnetic core shell MNS

| Sr. no. | Thickness of silica shell | Ms (emu/g) | Ms (emu/g) after theoretically calculated mass of silica shell |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | As prepared | 30 | - |

| 2 | ~ 1nm | 30 | - |

| 3 | 5 nm | 10 | 46 |

| 4 | 10 nm | 2.5 | 38 |

| 5 | 13 nm | 1.4 | 36 |

To prove this, theoretically calculated weight of silica in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS, was subtracted from weight of the sample. Figure 3B 2 and Table 1 shows that after subtraction, Ms values are closer to the experimentally calculated Ms values of POSS-coated MNS. This indicates that changes in saturation magnetization values in various magnetic nanostructures are due to increase in nonmagnetic content and there is no change in the magnetic properties of the core after silica shell formation. It is also interesting to note that there is no much difference in Ms values of as prepared Fe3O4 MNS and POSS-coated Fe3O4 MNS. This suggests that there is no much change in the magnetic properties after coating POSS on Fe3O4 MNS.

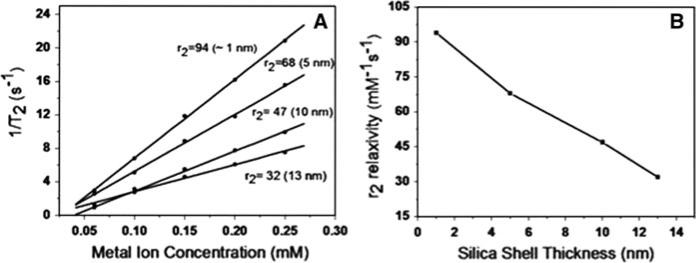

Figure 4A show the plot of 1/T2 versus iron concentration, in which r2 relaxivity coefficient was determined by the slope of the linear regression (Joshi et al. 2009). It demonstrates that as the iron concentration increases, the relaxation time decreases; indicating linear relationship with metal ion concentration. To understand the effect of size of Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS on r2 relaxivity, the r2 values were plotted against thickness of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core shell MNS in Fig. 4B. It shows that POSS-coated MNS has highest relaxivity coefficient and r2 relaxivity decreases with increase in thickness of the silica. Recently, Hu et al. reported that PEG-coated Fe3O4 MNS show larger r2 relaxivity than DEG-coated Fe3O4 MNS counterparts. The increase in r2 relaxivity was attributed to decreased diffusion coefficient of water in increased volume of hydrophilic PEG-coated Fe3O4 MNS. As stated in the introduction, r2 relaxivity of nanostructures is not only function of size but also function of many other parameters (Joshi 2013). In present study, to avoid complications of other parameters, same cores of magnetic nanoparticles nanoparticles are used in all samples. In the case of Fe3O4–SiOx core shell nanostructures, in spite of hydrophilic nature of amorphous silica, surprisingly our observation demonstrates opposite trend. Possible explanation for this observation is, in basic conditions, silica forms very dense coating, which leads to low internal surface area and less porosity (Finni et al. 2007). As the silica shell thickness increases distance between magnetic core and water molecules on the surface of silica shell increases and very negligible amount of water molecules may remain in close proximity of magnetic core. As discussed elsewhere in the literature (Joshi et al. 2009), under applied magnetic field and upon RF pulse, r2 contrasting effect is due to accelerated dephasing of larmor frequencies of water molecules closer to magnetic nanoparticles. According to outer sphere theory, (under assumption, ) r2 relaxivity can be predicted from the equation i.e., (Gillis et al. 2002)

| (1) |

where τD is translational diffusion co-relation time, V is volume fraction of MNS while Δω shift in the larmor frequency of water molecules at particle surface and infinity. As the shell thickness around magnetic core increases, distance between magnetic core and water molecules in the surrounding increases, consequently local magnetic dipolar field of nanoparticles experienced by water molecules decreases, which could possibly change the difference in the larmor frequencies of water molecules and hence r2 relaxivity.

Fig. 4.

A Plot of 1/T2 versus Metal ion concentration for Fe3O4–SiO2 core–shell with varying shell thicknesses number in the brackets indicate the thickness of the shell, B plot of r2 relaxivity coefficient versus thickness of silica shell around Fe3O4 MNS

This observation suggest that in spite that base catalyzed amorphous silica shell is hydrophilic in nature, relaxivity decreases with increase in silica shell thickness. We believe this study will help in designing silica based multifunctional MRI contrast agents that could be used in various biological applications such as diagnostics and drug delivery.

Summary and conclusion

To understand the relation between r2 relaxivity coefficient and thickness of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell MNS, various sizes of Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell were synthesized successfully. In spite of hydrophilic nature of silica, with increase in thickness of silica shell in Fe3O4–SiOx core–shell nanostructure, r2 relaxivity decreases. The decrease in relaxivity could be attributed to increased distance between water molecules and magnetic core followed by change in the difference in Larmor frequencies (Δω) of water molecules.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence (CCNE) initiative of the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute under Award U54CA119341 at Northwestern University. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health. Part of this work was performed in the EPIC/NIFTI facility of the NUANCE centre (supported by NSF-NSEC, NSFMRSEC, Keck Foundation, the State of Illinois, and Northwestern University) at Northwestern University. MRI measurements were performed at NorthShore University HealthSystem with the kind support of Center for Advanced Imaging. We would like to acknowledge paper by Blasiak et al. (2011) on similar research topic, which was published at nearly the same time when this contribution was under reviewing process.

Footnotes

Present Address: H. M. Joshi R&D Centre, Hindustan Polyamides and Fibres Limited, Navi Mumbai 400701, India

Contributor Information

Hrushikesh M. Joshi, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

Mrinmoy De, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

Felix Richter, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

Jiaqing He, Department of Chemistry, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

P. V. Prasad, Department of Radiology, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, IL 60201, USA

Vinayak P. Dravid, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA.

References

- Aslam M, Schutz EA, Sun T, Meade T, Dravid VP. Synthesis of amine-stabilized aqueous colloidal iron oxide nanoparticles. Cryst Growth Des. 2007;7:471–475. doi: 10.1021/cg060656p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasiak B, Zhang Z, Zhang T, Foniok T, Sutherland GR, Veres T, Tomnek B. The effect of coating of Fe3O4/silica core/shell nanoparticles on T-2 relaxation time at 9.4 T Eur. Phys. J Appl Phys. 2011;55:10401. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JB, Frankamp BL, Srivastava S, Rotello VM. Electrostatic self-assembly of structured gold nanoparticle/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) nanocomposites. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:690–694. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Bu W, Chen Y, Fan Y, He Q, Zhu M, Liu X, Zhou L, Zhang S, Peng W, Shi A. Sub-50-nm monosized superparamagnetic Fe3O4@SiO2T2-weighted MRI contrast agent: highly reproducible synthesis of uniform single-loaded core–shell nanostructures. J Chem Asian J. 2009;4:1809. doi: 10.1002/asia.200900276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, Kuang M, Wang X, Wang YA, Mao H, Nie S. Reexamining the effects of particle size and surface chemistry on the magnetic properties of iron oxide nano-crystals: new insights into spin disorder and proton relaxivity. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:8127–8131. [Google Scholar]

- Finni KS, Bartlett JR, Barbe' CJA, Kong L. Formation of silica nanoparticles in microemulsions. Langmuir. 2007;23:3017–3024. doi: 10.1021/la0624283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankamp BL, Fischer NO, Hong R, Srivastava S, Rotello VM. Surface modification using cubic silsesquioxane ligands facile synthesis of water-soluble metal oxide nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2006;18:956–959. [Google Scholar]

- Gillis P, Moiny F, Brooks RA. On T2-shortening by strongly magnetized spheres: a partial refocusing model. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:257–263. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, MacRenaris KW, Waters EA, Liang T, Schultz-Sikma EA, Eckermann AL, Meade TJ. Ultrasmall, water-soluble magnetite nanoparticles with high relaxivity for magnetic resonance imaging. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:20855–20860. doi: 10.1021/jp907216g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C, Shen C, Yang T, Bao L, Tian J, Ding H, Li C, Gao HJ. Large-scale Fe3O4 nanoparticles soluble in water synthesized by a facile method. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:11336–11339. [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, Nah H, Lee JH, Moon SH, Kim MG, Cheon J. Critical enhancements of MRI contrast and hyperthermic effects by Dopant-controlled magnetic nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1234–1238. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Scholz R, Wust P, Fahling H, Krause J, Wlodarczyk W, Sander B, Vogl TH, Felix R. Effects of magnetic fluid hyperthermia (MFH) on C3H mammary carcinoma in vivo. Int J Hyperth. 1997;13:587–605. doi: 10.3109/02656739709023559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi HM. Multifunctional ferrite nanoparticles for MR imaging applications. J Nanopart Res. 2013;15:1235. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi HM, Lin YP, Aslam M, Prasad PV, Schultz EA, Edelman R, Meade T, Dravid VP. Effects of shape and size of cobalt ferrite nanostructures on their MRI contrast and thermal activation. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:17761–17767. doi: 10.1021/jp905776g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun YW, Huh YM, Choi JS, Lee JH, Song HT, Kim S, Yoon S, Kim KS, Shin JS, Suh JS, Cheon J. Nanoscale size effect of magnetic nanocrystals and their utilization for cancer diagnosis via magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5732–5733. doi: 10.1021/ja0422155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaConte LEW, Nitin N, Zurkiya O, Caruntu D, O'Connor CJ, Hu X, Bao G. Coating thickness of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles affects R2 relaxivity. J Mag Res Imag. 2007;26:1634–1641. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S, Forge D, Port M, Roch A, Robic C, Elst LV, Muller RN. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2064–2110. doi: 10.1021/cr068445e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Huh YM, Jun YW, Seo JW, Jang JT, Song HT, Kim S, Cho EJ, Yoon HG, Suh JS, Cheon J. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nat Med. 2007;13:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molday RS, Mackenzie D. Immunospecific ferromagnetic iron-dextran reagents for the labeling and magnetic separation of cells. J Immun Meth. 1982;52:353–367. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, An K, Hwang Y, Park JG, Noh HJ, Kim JY, Park JH, Hwang NM, Hyeon T. Ultra-large-scale syntheses of monodisperse nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2004;3:891–895. doi: 10.1038/nmat1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho SLC, Pereira GA, Voisin P, Kassem J, Bouchaud V, Etienne L, Peters JA, Carlos L, Mornet S, Geraldes CFGC, Rocha J, Delville MH. Fine tuning of the relaxometry of γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 nanoparticles by tweaking the silica coating thickness. ACS Nano. 2010;9:5339–5349. doi: 10.1021/nn101129r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad NK, Rathinasamy K, Panda D, Bahadur D. Mechanism of cell death induced by magnetic hyperthermia with nanoparticles of γ-MnxFe2–xO3 synthesized by a single step process. J Mater Chem. 2007;17:5042–5051. [Google Scholar]

- Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Nanostructures in biodiagnostics. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1547–1562. doi: 10.1021/cr030067f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AM. Thermoresponsive magnetic colloids. Colloid Poly Sci. 2007;285:953–966. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-sikma EA, Joshi HM, Ma Q, Macrenaris KW, Eckerman AL, Dravid VP, Meade TJ. Probing the chemical stability of mixed ferrites: implications for magnetic resonance contrast agent design. Chem Mater. 2011;23:2657. doi: 10.1021/cm200509g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Lee JSH, Zhang M. Magnetic nanoparticles in MR imaging and drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1252–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulman A. Formation and structure of self-assembled monolayers. Chem Rev. 1996;96:1533. doi: 10.1021/cr9502357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt C, Toprak MS, Muhammed M, Laurent S, Bridot JL, Muller RN. High quality and tuneable silica shell–magnetic core nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res. 2010;12:1137–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Cushing BL, O'Connor CJ. Synthesis and characterization of monodisperse ultra-thin silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:085601. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/8/085601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]