Abstract

Despite the growing practice of international adoption over the past 60 years, the racial and ethnic experiences of adopted youth are not well known. This study examined the moderating role of ethnic identity in the association between racial/ethnic discrimination and adjustment among transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents (N = 136). Building on self-categorization theory and past empirical research on Asian Americans, it was hypothesized that ethnic identity would exacerbate negative outcomes associated with discrimination. The moderating role of ethnic identity was found to vary by specific ethnic identity dimensions. For individuals with more pride in their ethnic group (affective dimension of ethnic identity), discrimination was positively associated with externalizing problems. For individuals with greater engagement with their ethnic group (behavioral dimension of ethnic identity), discrimination was positively associated with substance use. By contrast, clarity regarding the meaning and importance of one’s ethnic group (cognitive dimension of ethnic identity) did not moderate the relationship between discrimination and negative outcomes.

Keywords: ethnic identity, discrimination, transracial adoptees, Korean Americans

Discrimination based on race and ethnicity is a common life experience for Asian Americans (Alvarez, Juang, & Liang, 2006). These experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination, in turn, are associated with poor mental and physical health (e.g., Gee, Spencer, Chen, & Takeuchi, 2007; Lee & Ahn, 2011; Paradies, 2006). Despite the detrimental effects of racial/ethnic discrimination, theory and research suggest that individual differences in ethnic identity can modify the strength or direction of the discrimination-adjustment association (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Though ethnic identity is primarily construed as a protective asset, most research finds that it exacerbates the discrimination-adjustment association among Asian Americans (R. M. Lee, 2005; Noh, Besier, Kaspar, Hou, & Rummens, 1999; Yip, Gee, & Takeuchi, 2008; Yoo & R. M. Lee, 2005, 2008). In the present study, we further explore the role of ethnic identity as a moderator in the association between racial/ethnic discrimination and adjustment among transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents, whose racial and ethnic experiences are distinct from immigrant and native-born Asian Americans raised in same-race families.

Transracial, Transnational Korean American Adolescents

The international adoption population has grown dramatically over the past sixty years with a worldwide estimate of 970,000 children adopted internationally from 1948–2010 (Selman, 2012). Over twenty percent of these internationally adopted children were from South Korea. In the United States, over 110,000 South Korean children have been adopted by Americans who are predominatly White (E. Kim, 2007). Despite the popularity of international adoption, especially from South Korea, the racial and ethnic experiences of internationally adopted children and youth are not well known. The majority of psychological research on internationally adopted children and youth have focused on the preadoption risk factors for maladjustment and behavioral development of these children (R. M. Lee, 2003).

Adoption scholars have posited that internationally adopted individuals who are raised in White families are confronted with the task of navigating unique racial and ethnic paradoxes. First, as transracial adoptees, they are tasked with negotiating the inherent contradiction of being a part of, yet separate from, the dominant White society (i.e., transracial adoption paradox; R. M. Lee, 2003). Second, as trasnational adoptees, they must contend with the loss of their ethnic culture and subsequent assimilation into the dominant White culture of their family (R. M. Lee & Miller, 2009). The challenges related to racial differences and the absence of a shared ethnic culture between White parents and their internationally adopted children can complicate the racial/ethnic experiences of these youth, including racial/ethnic discrimination and ethnic identity development. However, the postadoption experiences of transracially, transnationally adopted individuals have been largely overlooked within the field of psychology (R. M. Lee, 2003).

Discrimination and Adjustment

Racial/ethnic discrimination (hereafter referred to as discrimination) is broadly defined as the behavioral manifestations of prejudice, including unfair treatment based on racial and ethnic differences (e.g., Gee, Ryan, Laflamme, & Holt, 2006). The uncontrollable and unpredictable nature of discrimination, especially when persistent, is viewed as particularly disruptive to healthy development across populations (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Discrimination is believed to be an important factor related to adjustment problems in adolescence, including internalizing problems (i.e., problem behaviors that reflect internal distress, such as anxiety and depression) and externalizing problems (i.e., problems that manifest in outward behaviors, such as aggression), as well as substance use (e.g., García Coll et al., 1996).

In studies on immigrant or native-born Asian Americans, research clearly supports a positive association between discrimination and anxiety (Cassidy, O’Connor, Howe, & Warden, 2004) and depressive symptoms (Becker & Grilo, 2007; Cassidy et al., 2004). Research also supports a positive link between discrimination and externalizing problems (Park, Schwartz, R. M. Lee, & Kim, 2013). For instance, Park and colleagues (2013) found that East Asian and South Asian American college students’ reports of discrimination were positively correlated with antisocial behaviors. Internalizing and externalizing problems, in turn, are factors that contribute to a nonnormative developmental trajectory, which can include greater likelihood of substance use during adolescence (Brook & Newcomb, 1995). In support of this assertion, discrimination has been found to be positively associated with substance use among Asian Americans (Chae et al., 2008; Tran, Lee, & Burgess, 2010). Despite the gains in research on discrimination and adjustment among Asian Americans, little attention has been paid to the racial and ethnic experiences of transracially, transnationally adopted Asian Americans.

Racial/ethnic experiences related to prejudice and discrimination inevitably color postadoption experiences, and likely impact adjustment for transracially, transnationally adopted individuals due to their status as racial minorities. Extant research supports that discrimination is relevant to transracially, transnationally adopted individuals (R. M. Lee, 2003). In a large epidemiological study using data from the Swedish national registry, transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents and young adults were found to be two to three times more likely to have serious psychiatric and social maladajustment problems than their non-adopted siblings and the general population, but had similar rates of maladjustment problems as Asian and Latin American immigrants in Sweden (Hjern, Lindblad, & Vinnerljung, 2002). The researchers concluded that challenges around racial prejudice and discrimination most likely explain the comparable levels of adjustment difficulties of adoptees and immigrants. However, there is limited research that directly examines discrimination as a potential contributing factor to adjustment among transracially, transnationally adopted individuals. In one study, discrimination was found to be associated with greater behavioral problems and psychological distress in a sample of ethnically diverse adopted adolescents in Sweden (Cederblad, Höök, Irhammar, & Mercke, 1999). R. M. Lee & MnIAP (2010) similarly found evidence to support that adoptive parents’ perceptions of discrimination (i.e., intrusive and inappropriate racial- and adoption-related comments) uniquely accounted for variance in internalizing and externalizing problems, above and beyond preadoption adversity, for U.S. children and adolescents adopted internationally from Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

The Moderating Role of Ethnic Identity

Researchers have examined ethnic identity as an individual difference variable that may modify the strength or the direction of the discrimination-adjustment association in Asian American, African American, Latino/a, and Native American populations (e.g., Galliher, Jones, & Dahl, 2011; Mossakowski, 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Torres & Ong, 2010; see Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009 for a review). Yet all these studies have focused on immigrant or native-born populations. To our knowledge, there are no published studies that have examined how ethnic identity moderates the psychological effects of discrimination among transracially, transnationally adopted individuals.

Ethnic identity refers to the part of the self-concept that is derived from the degree to which individuals perceive themselves to be included and connected with an ethnic minority group (Phinney, 1990). Most scholars conceptualize ethnic identity as including clarity and resolution about one’s ethnic background, affect and regard toward one’s ethnic group, and behavioral engagement with one’s ethnic heritage (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). For this investigation, we separately examine the cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of ethnic identity, an approach that is consistent with current measures of ethnic identity, such as the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (Phinney, 1992) and Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004).

By nature of having clear understanding and appreciation for one’s ethnic background along with a sense of belonging with a larger collective group, ethnic identity is theorized to be positively associated with psychological adjustment and well-being. Psychological research on immigrant and native-born Asian American youth and adults supports this view. These three dimensions of ethnic identity are associated with higher self-esteem, life satisfaction, and less psychological distress (R. M. Lee, 2005; R. M. Lee, & Yoo, 2004; Yip & Fuligni, 2002). However, the extant research that examines the association between ethnic identity and adjustment among transracially, transnationally adopted individuals is equivocal. Yoon (2001) found that ethnic identity, as measured by ethnic pride, had a direct positive impact on adopted Korean American adolescents’ psychological adjustment. Conversely, Cederblad and colleagues (1999), found that ethnic identity, as measured by behavioral engagement, was positively associated to emotional distress, behavioral problems, and lower self-esteem in an ethnically diverse sample of transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents. R. M. Lee, Yoo, and Roberts (2004) similarly found that ethnic identity, as measured by behavioral engagement, was negatively correlated with life satisfaction in an adult sample of transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American. These limited and equivocal findings with transracially, transnationally adopted individuals suggest the need for further study on the role of ethnic identity in this population.

The social identity perspective (Hogg, Abrams, Otten, & Hinkle, 2004), which encompasses both social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987), provides two possible explanations for the role of ethnic identity in the context of discrimination. Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) explains how individuals negotiate intergroup competition, such as prejudice and discrimination, which includes motivation to think affirmingly about one’s ingroup in order to derive a more positive sense of self. From this perspective, ethnic identity likely serves as a cultural resource that functions to protect against the negative impact of discrimination (Phinney, 2003). That is, racial/ethnic minorities may react to discrimination by increasing focus on the positive aspects of their ethnic group, thereby enhancing their overall self-concept. To this end, Mossakowski (2003) found that ethnic identity, as measured by cognitive, affective, and behavioral components, functioned as a protective factor that significantly reduced the effects of lifetime discrimination on depressive symptoms in a large sample of adult Filipino Americans.

Self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987) focuses on the cognitive processes by which individuals attend to salient cues in the immediate social context to categorize themselves and others into meaningful groups. From this perspective, ethnic identity may facilitate the process of making sense of one’s social context in terms of racial/ethnic group differences, which could make experiences with prejudice and discrimination more salient, and possibly exacerbate the distress associated with discrimination (Yip et al., 2008). In support of this perspective, Noh and colleagues (1999) found that high levels of ethnic identity strengthened the association between discrimination and depression in a sample of Southeast Asian refugees living in Canada. Similarly, Yoo and R. M. Lee (2005) found that discrimination was positively associated with negative affect for Asian American college students with higher ethnic identity.

Overall, the majority of studies that have examined ethnic identity as a moderator against the psychological impact of discrimination, specifically among Asian Americans, have found an exacerbating effect (R. M. Lee, 2005; Noh et al., 1999; Yip et al., 2008; Yoo & R. M. Lee, 2005, 2008) outside of the few that have found no interaction (Liang & Fassinger, 2008; Stein, Kiang, Supple, & Gonzalez, 2014) or a protective effect (Mossakowski, 2003; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2008). By contrast, studies that have examined the moderating role of ethnic identity in non-Asian samples have largely found protective effects (e.g., Galliher, Jones, & Dahl, 2011; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). According to social identity perspective, the results from these studies may suggest that Asian Americans with high ethnic identity may categorize themselves and others along racial/ethnic boundaries by using contextual cues like discrimination, thereby accentuating similarities within groups and differences between groups. This heightened awareness of discrimination, in turn, may lead to increased sensitivity and reactiveness to experiences of discrimination.

It is not clear why ethnic identity more commonly acts as an exacerbating factor for Asian Americans, in comparison to other racial/ethnic groups. One possibility is that the type of discrimination experienced by Asian Americans is uniquely tinged with the message that they do not belong in America, which reifies racial/ethnic group boundaries. Sociological literature supports the notion that Asian Americans are racialized as the “other,” where they are often categorized as outsiders and perpetual foreigners who are unable to fully integrate into U.S. society (C. J. Kim, 1999). Psychological research further supports that the daily lives of Asian Americans are filled with frequent exchanges that challenge their membership as an American (Sue, Bucceri, Lin, Nadal, & Torino, 2007; Cheryan & Monin, 2005). Perhaps then, self-categorization (i.e., maximizing perceived differences between group and similarities within groups) is strengthened among Asian Americans as a natural and adaptive response to a pervasive stereotype that precludes them from integrating into the dominant society. By nature of sharing the social space in which immigrant and native-born Asian Americans reside, transracially, transnationally adopted Korean Americans may more frequently engage in cognitive processes of group categorization, which would exacerbate the discrimination-adjustment association.

Current Study

The purpose of this study is to examine the association between discrimination, ethnic identity, and adjustment among transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents. We draw from research on immigrant or native-born Asian Americans to make study hypotheses given the lack of literature on transracially, transnationally adopted individuals. We hypothesized that discrimination would be significantly associated with higher internalizing and externalizing problems and substance use in our sample. Based on past research (Cederblad et al., 1999; R. M. Lee et al., 2004; Yoon, 2001), we also hypothesized that cognitive and affective, but not behavioral, dimensions of ethnic identity would be associated with lower internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as substance use. Consistent with self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987), we expected that ethnic identity would exacerbate the effects of discrimination on internalizing and externalizing problems and substance use. Due to limited prior research on differential interactions between dimensions of ethnic identity and discrimination in this population, specific moderation hypotheses for each dimension were not made. Last, in order to examine the unique contribution of discrimination, we controlled for preadoption adversity as early deprivation has been associated with the development of behavioral problems (Gunnar, Van Dulmen, & International Adoption Project Team, 2007).

Method

Participants and Procedure

We used data from the Korean Adoption Project (2007–2008), which is the first wave of a longitudinal study examining how transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American children and youth as well as their adoptive parents navigate issues around culture, ethnicity, and race. This project supplemented an existing interdisciplinary epidemiological study on the general health and well-being of international adoptees in Minnesota, called the International Adoption Project (IAP) (MnIAP; http://www.cehd.umn.edu/icd/research/iap/Team/staff.html). Participants for this particular study were identified and drawn through the IAP family research registry. Surveys were mailed to White parents who have adopted a child from South Korea, as well as Korean American adoptees, ages 13–18, residing with their adoptive parent(s). A total of 593 families expressed interest in participating in the study. A survey was completed for each adopted child by one parent who self-identified as the primary caretaker, making a total of 578 returned parent surveys for a return rate of 74%. Of the 352 eligible adopted Korean American adolescents, 248 surveys were returned for a return rate of 70%.

For this investigation, we only included adolescent participants who had matched parent data in order to integrate demographic and health information about the adolescents in the analyses, which was only available from the parent survey. In addition, adolescents with significant mental health issues or a known developmental disorder (i.e., cerebral palsy, fetal alcohol syndrome, schizophrenia, mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorder) were excluded from the analyses. The final sample consisted of 136 transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents (M age = 15.16, SD = 1.54, 56% male).

Measures

Ethnic identity

Ethnic identity was measured using the 14-item Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney, 1992). Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). A higher score on the MEIM represents a more positive ethnic identity. R. M. Lee and Yoo’s (2004) three-factor version of this measure was used as a multidimensional measure of ethnic identity. The factor structure derived from their analysis aligns with the three commonly identified dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., cognition, affect, and behavior). Specifically, the ethnic identity cognition factor consists of five items that measure a sense of cognitive clarity and self-understanding regarding membership in one’s ethnic group (e.g., “I have a clear sense of being Korean and what it means for me”). The ethnic identity affect factor consists of three items that measure positive feelings and attitudes towards one’s ethnic group (e.g., “I have a strong sense of belonging with other Koreans”). The ethnic identity behavior(s) factor consists of five items that measure active participation in one’s group (e.g., “I participate in Korean cultural practices, such as food, music, or customs”). This measurement approach has been used with various Asian ethnic groups, including transracial, transnational Korean American adult adoptees (R. M. Lee et al., 2004). Moreover, the MEIM demonstrates good validity and has been used in a wide range of Asian American samples, including high school students (e.g., Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006) and adoptees (e.g., Song & R. M. Lee, 2009). The internal reliability estimate (α) in this sample was .65, .80, .73 for ethnic identity cognition (EI-Cog), affect (EI-Affect), and behavior (EI-Behave), respectively.

Discrimination

Nine items were developed for this study on the basis of a review of literature on the forms of discrimination that are commonly experienced by transracially, transnationally adopted Korean Americans. Moreover, the scale items were reviewed and modified by four adopted Korean American scholars and activists to ensure relevance to the adoptee community. These items examined general perceptions of denigration due to racial/ethnic differences. Sample items include, “I have overheard people make rude or insensitive ethnic and racial comments about minorities” and “I have been expected to have certain abilities, skills, or talents because I am Korean or Asian.” Respondents indicated the frequency at which each event occurred in their lifetime on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). These items share some similarity with items found in recently developed discrimination scales for Asian Americans, such as The Brief Discrimination Scale (Pituc, Jung, & R. M. Lee, 2009), Subtle and Blatant Racism Scale for Asian American College Students (Yoo, Steger, & R. M. Lee, 2010), and measures of racial and ethnic microaggressions (Nadal, 2011; Ong, Burrow, Fuller-Rowell, Ja, & Sue, 2013). However, none of these measures were published at the time of our study.

An exploratory factor analysis with no rotation was conducted to estimate factor loadings of the items for the sample population. This analysis revealed one factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1 (4.61) and explained 51% of the total variance. A scree test confirmed the selection of one factor for scale validation. Factor loadings for each item ranged from 0.66 to 0.80. This scale also correlated with conceptually similar behaviors, such as a single-item on having conversations with friends around “ethnic or cultural issues” (r = 0.32, p <. 01) and a measure of parental racial socialization (r = 0.17, p = .05). The internal reliability estimate (α) in this sample was .87.

Adjustment Problems

The 25-item Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1999) was used to measure internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors. For this study, we adopted Ruchkin, Jones, Vermeiren, and Schwab-Stone’s (2008) version of the SDQ because it was specifically validated for use as a self-report measure with youth in the United States. This version included three factors; however, only internalizing problems (8 items) (e.g., “I worry a lot.” and “I have many fears, I am easily scared.”) and externalizing problems (7 items) (e.g., “I fight a lot. I can make other people do what I want.” and “I get very angry and often lose my temper.”) were examined since the third factor, social competence, is not theoretically relevant for this study. Adolescents rated each item using a 3-point scale from 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true), and 2 (certainly true). Items reflecting problems were summed to create a total difficulties score for internalizing and externalizing problems. In Ruchkin et al. (2008)’s study, the average difficulties score across urban vs. suburban samples, respectively, were 4.00 vs. 3.40 for internalizing problems and 4.21 vs. 3.62 for externalizing problems. The SDQ has been used in many countries across diverse populations, including adopted youth. Golombok, MacCallum, and Goodman (2001) compared psychological well-being across adopted children, children conceived via in vitro fertilization, and children naturally conceived, and found no significant differences in scores. In addition, the adopted children were also well within the normal range of functioning. In our study, the internal reliability estimate (α) was .73 for internalizing problem behaviors and .74 for externalizing problem behaviors.

Substance Use

Substance use behaviors were assessed with three items that were developed for this study. The items asked about the typical frequency of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (e.g., marijuana) use. Specifically, adolescents were asked to rate the frequency of engaging in substance use related behaviors (i.e., “drink alcohol, such as beer, wine, or liquor,” “smoke cigarettes,” “tried other drugs, such as marijuana”). These items were assessed on a 5-point scale from 1 (never or not at all) to 5 (almost always). For the analyses, a mean score was computed. Such an unweighted composite index of drug use among adolescents has been found to be a robust predictor of reported social, physical, and legal costs of drug use (Needle, Su, & Lavee, 1989). Furthermore, alcohol, cigarette, and other drug use were intercorrelated, which is consistent with prior methodological research (e.g., Wills, Yaeger, & Sandy, 2003). The internal reliability estimate (α) in this sample was .74.

Preadoption adversity

Preadoption adversity was measured as an adversity index using duration of institutional care, age at time of adoption in months, and health status immediately after adoption (see Gunnar et al. 2007). Total time spent in a hospital, baby home, or orphanage was calculated in months to assess duration of institutional care. Children who spent more than 4 months in any of these settings (n = 17; 12.5%) were given a score of 1. If children were more than 24 months old at time of adoption (n = 5; 3.5%), they were given a score of 1. Children who were diagnosed or treated for one or more of the following illnesses after adoption (including Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, elevated lead level, anemia, syphilis, hearing problems, vision problems, intestinal parasites, chronic ear infection, or microcephaly) were given a score of 1 (n = 25; 18.4%). These three indices were aggregated to create an index of preadoption adversity ranging from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating minimal adversity and 3 indicating exposure to more adversity. The mean adversity score was .35 (SD = .63), with 72% of the sample having no exposure to preadoption adversity.

Results

A Missing Values Analysis was conducted on all study variables to identify variables with greater than 5% missing data. The affective dimension of ethnic identity (EI-Affect) variable consisted of a substantial proportion of missing values (5.9%), which revealed a significant pattern of missing cases with internalizing problem behaviors (Present: M = 3.02; Missing: M = .75; t(14.1) = 5.2, p < .001) and substance use (Present: M = 1.15; Missing: M = 1.00; t(126) = 3.6, p < .001). Little’s (1988) MCAR test showed that the pattern of missing values did not depend on the data values (p = .97). Imputed mean scale scores were then created using expectation maximization for EI-Affect.

Table 1 presents the correlation matrix, including scale means, for all the study variables. As hypothesized, discrimination correlated significantly with internalizing problems (r = .33, p < .01), externalizing problems (r = .35, p < .01), and substance use (r = .19, p < .05). The correlations between both cognitive and affective dimensions of ethnic identity with discrimination, internalizing and externalizing problems, and substance use were not statistically significant. Interestingly, the behavioral dimension of ethnic identity had significant positive correlations with discrimination (r = .38, p < .01), internalizing problems (r = .35, p < .01), externalizing problems (r = .18, p < .05), and substance use (r = .30, p < .01).

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and Scale Means

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-adopt Adv. | -- | −.12 | .00 | −.08 | −.05 | .02 | .00 | −.16 |

| 2. EI-Cog | -- | .61** | .55** | .05 | −.07 | .00 | .14 | |

| 3. EI-Affect | -- | .44** | .10 | −.12 | −.12 | .03 | ||

| 4. EI-Behave | -- | .38** | .35** | .18* | .30** | |||

| 5. Discrimination | -- | .33** | .35** | .19* | ||||

| 6. In. Prob. | -- | .41** | .19* | |||||

| 7. Ext. Prob. | -- | .25** | ||||||

| 8. Substance Use | . | -- | ||||||

| Mean | .35 | 2.70 | 3.17 | 2.36 | 1.93 | 2.978 | 2.88 | 1.14 |

| SD | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 2.51 | 2.67 | 0.47 |

Note. EI-Cog = Ethnic identity cognition, EI-Affect = Ethnic identity affect, EI-Behave = Ethnic identity behavior.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to test the hypothesized main and interaction effects. Specifically, Aiken and West’s (1991) statistical procedure was employed in order to examine the type of moderating role that different dimensions of ethnic identity have on the association between discrimination and adjustment. After centering all study variables, three hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed, with internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and substance use as dependent variables. To examine the unique contribution of each variable, preadoption adversity was entered in Step 1 as a covariate, discrimination was entered in Step 2, then the three dimensions of ethnic identity (EI-Cog, EI-Affect, and EI-Behave) were entered in Step 3, and the three interaction terms (Disc × EI-Cog, Disc × EI-Affect, and Disc × EI-Behave) were entered in Step 4 (Table 2 presents the results from the final model [i.e., Step 4]). Next, regression slopes of significant two-way interactions were plotted using predicted values for representative high (+1 SD) and low ethnic identity (−1 SD) on discrimination. Because the power of testing interactions is dependent on sample size, and our sample was relatively small, we decided to examine effect size (f2) to determine the contribution of the three interaction effects to the overall variance. Following Cohen’s (1988) conventions, a f2 of .06 (f2 = .02 per interaction) or greater was selected as a criterion for a small effect size. In order to determine the unique contribution of each first-order and interaction effect, squared semipartial correlations were examined (Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, & Aiken, 2003).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Testing Ethnic Identity Dimensions as Moderators of Discrimination

| Internalizing Problems | Externalizing Problems | Substance Use | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Final Step | B | SE | β | sr2 | B | SE | β | sr2 | B | SE | β | sr2 |

| (Constant) | 2.67 | .25 | 2.82 | .25 | 1.12 | .05 | ||||||

| Preadoption Adversity | .21 | .33 | .05 | .00 | .18 | .34 | .04 | .00 | −.05 | .06 | −.07 | .00 |

| Discrimination | .53 | .23 | .20* | .03 | .68 | .24 | .26** | .05 | .05 | .04 | .10 | .00 |

| EI-Cog | −.78 | .30 | −.30* | .04 | .36 | .30 | .14 | .01 | .01 | .05 | .03 | .00 |

| EI-Affect | −.47 | .26 | −.18 | .02 | −.54 | .26 | −.22* | .03 | −.07 | .05 | −.16 | .01 |

| EI-Behave | 1.33 | .28 | .51*** | .14 | .15 | .28 | .06 | .00 | .14 | .05 | .29† | .04 |

| Disc × EI-Cog | −.57 | .29 | −.22 | .02 | .10 | .29 | .04 | .00 | .00 | .05 | .00 | .00 |

| Disc × EI-Affect | .17 | .27 | .06 | .00 | .68 | .28 | .28* | .04 | −.06 | .05 | −.14 | .01 |

| Disc × EI-Behave | .41 | .24 | .17 | .01 | −.32 | .24 | −.15 | .01 | .11 | .04 | .27* | .04 |

Note. Disc = Discrimination.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Internalizing Problems

In Step 1, the covariate, preadoption adversity, on internalizing problems was not statistically significant at the p < .05 level (R2 = .00), F(1, 119) = .002. In Step 2, the main effect of racial/ethnic discrimination on internalizing problems was statistically significant (R2 = .09; f2 = .09), F(1, 118) = 12.68, p = .001. In Step 3, the incremental main effect of the set of dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., EI-Cog, EI-Affect, EI-Behave) on internalizing problems was statistically significant (R2 = .24, ΔR2 = .14; f2 = .31), F(3, 115) = 7.48, p < .001. Specifically, EI-Cog was negatively related to internalizing problems (B = −.78, sr2 = .04, p = .01), whereas EI-Behave was positively related to internalizing problems (B = 1.33, sr2 = .14, p < .001). In Step 4 (see Table 2), contrary to hypothesis, the incremental effect of the set of three two-way interaction terms between discrimination and dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., Disc × EI-Cog, Disc × EI-Affect, Disc × EI-Behave) on internalizing problems explained an additional 3% of the variance, above and beyond the 24% explained by the main effects; thus, failing to meet the criterion for a small overall effect size (R2 = .27; ΔR2 = .03; f2 = .05), F(3, 112) = 1.79, p = .15.

Externalizing Problems

In Step 1, the covariate, preadoption adversity, on externalizing problems was not statistically significant at the p < .05 level (R2 = .00), F(1, 116) = .000. In Step 2, the main effect of racial/ethnic discrimination on externalizing problems was statistically significant (R2 = .10; f2 = .11, F(1, 115) = 13.53, p < .001. In Step 3, the incremental main effect of the set of dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., EI-Cog, EI-Affect, EI-Behave) on externalizing problems was not statistically significant (R2 = .14, ΔR2 = .03; f2 = .16), F(3, 112) = 1.59, p = .19. In Step 4 (see Table 2), the incremental effect of the set of three two-way interaction terms between discrimination and dimensions of ethnic identity (e.g., Disc × EI-Cog, Disc × EI-Affect, Disc × EI-Behave) on externalizing problems explained an additional 6% of the variance, above and beyond the 14% explained by the first-order effects, meeting the criterion for a small overall effect size (R2 = .20; ΔR2 = .06; f2 = .08), F(3, 109) = 2.89, p < .05. In terms of the specific moderator effects, discrimination was significantly moderated by EI-Affect only (B = .68, sr2 = .04, p < .05). Despite the presence of intercorrelations among the independent variables, tolerance was greater than .10 (.49 – .94) and the variance inflation factor was less than 10 (1.06 – 2.06), suggesting that multicollinearity was not an issue.

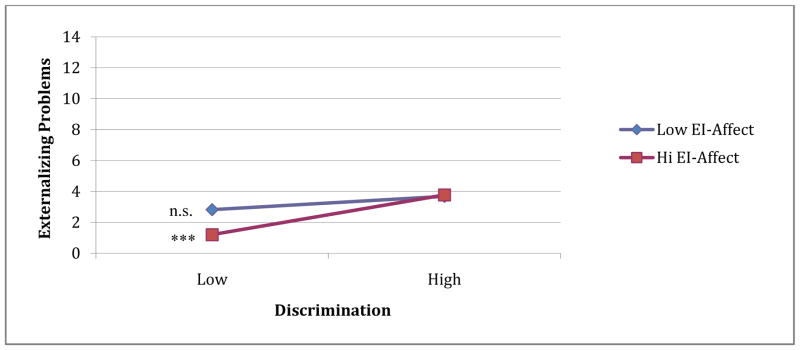

Simple slope analyses showed that the slope of discrimination on externalizing problems was significantly different from zero when the conditional value of EI-Affect was high (+1 SD) (R2 = .17), F(3, 124) = 8.95, p < .001 (with discrimination B = 1.28, sr2 = .15, p < .001), and it was not significantly different from zero when the conditional value was low (−1 SD) (discrimination B = .42, sr2 = .01, p = .16). In other words, for individuals with higher EI-Affect, there was a significant positive association between discrimination and externalizing problems (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interaction effect between ethnic identity affect (EI-Affect) and discrimination on externalizing problems. *** p< .01.

PROCESS, a computational tool for path analysis-based moderation (Hayes & Preacher, 2013), was implemented in order to further probe the interaction effect. First, simple slopes of discrimination on externalizing problems were generated at different percentile values of EI-Affect. A table of estimated values of externalizing problems for various values of discrimination and EI-Affect was then produced. In the final step, the Johnson-Neyman technique was implemented to identify the values of EI-Affect at which the simple slope of discrimination on externalizing problems moves from non-significance to significance at a p value of .05. Results indicated an upward boundary of −0.77 (with no lower boundary), indicating that the simple slope of discrimination on externalizing problems is significantly different from zero when the standardized value of EI-Affect exceeds −0.77.

Substance Use

In Step 1, the covariate, preadoption adversity, on substance use was not statistically significant at the p < .05 level (R2 = .02), F(1, 119) = 2.50. In Step 2, the main effect of racial/ethnic discrimination on substance use was statistically significant (R2 = .06, ΔR2 = .04; f2 = .06, F(1, 118) = 4.99, p < .05. In Step 3, the incremental main effect of the set of dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., EI-Cog, EI-Affect, EI-Behave) on substance use was statistically significant (R2 = .13, ΔR2 = .07; f2 = .14), F(3, 115) = 3.43, p < .05. Specifically, EI-Behave was positively related to substance use (B = .14, sr2 = .04, p = .01). In Step 4 (see Table 2), the incremental effect of the set of three two-way interaction terms between discrimination and dimensions of ethnic identity (.e., Disc × EI-Cog, Disc × EI-Affect, Disc × EI-Behave) on substance use explained an additional 5% of the variance, above and beyond the 13% explained by the first-order effects (R2 = .18; ΔR2 = .05; f2 = .06), F(3, 112) = 2.24, p = .08. In terms of the specific moderator effects, discrimination was significantly moderated by EI-Behave only (B = .11, sr2 = .04, p < .05). Again, a collinearity diagnostic on the specific moderator effect does not suggest strong possibility for multicollinearity as tolerance was greater than .10 (.49 – .93) and the variance inflation factor was less than 10 (1.06 – 2.09).

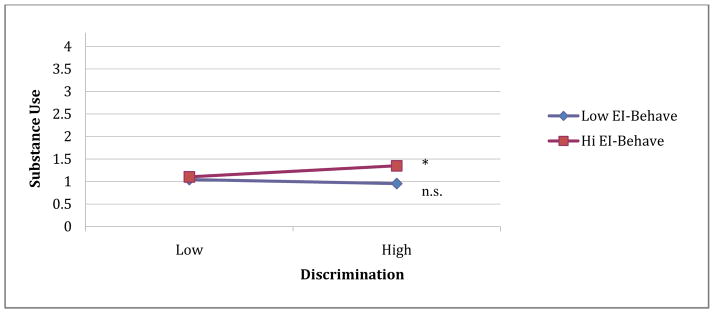

Simple slope analyses showed that the slope of discrimination on substance use was significantly different from zero when the conditional value of EI-Behave was high (+1 SD) (R2 = .14), F(3, 122) = 6.63, p < .001 (with discrimination B = .12, sr2 = .03, p < .05), and it was not significantly different from zero when the conditional value was low (−1 SD) (with discrimination B = −.04, sr2 = .0, p = .45) (See Figure 2). Thus, for individuals with higher EI-Behave, there was a significant positive association between discrimination and substance use (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interaction effect between ethnic identity behaviors (EI-Behave) and discrimination on substance use. * p< .05.

PROCESS was again implemented in order to further probe the interaction effect to identify the values of EI-Behave at which the simple slope of discrimination on substance use moves from non-significance to significance at a p value of .05. Results indicated an upward boundary of 0.83 (with no lower boundary), which suggests that the simple slope of discrimination on substance use is significantly different from zero when the standardized value of EI-Behave exceeds 0.83.

Discussion

This study examined whether ethnic identity modifies the strength or direction of the relation between discrimination and adjustment among transracially, transnationally adopted Korean Americans. First, we examined the associations of discrimination, ethnic identity, and adjustment. Discrimination was significantly associated with greater internalizing and externalizing problems, as well as substance use. These findings are consistent with existing research on ethnically diverse adopted adolescents (Cederblad et al., 1999; R. M. Lee & MnIAP, 2010) and immigrant and native-born Asian Americans (Chae et al., 2008; D. L. Lee & Ahn, 2011; Tran et al., 2010). By contrast, the cognitive and affective dimensions of ethnic identity were not related to internalizing problems and externalizing problems and substance use. However, the behavioral dimension of ethnic identity was significantly positively related to these problem behaviors. The lack of significant correlations between cognitive and affective dimensions of ethnic identity with problem behaviors are surprising given that the general research literature suggests that ethnic identity is linked to adaptive outcomes (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014). Furthermore, the positive correlation between the behavioral dimension of ethnic identity and problems behaviors was somewhat unanticipated, although there has been a growing amount of research suggesting that certain dimensions of ethnic identity are associated with negative adjustment (Cederblad et al., 1999; R. M. Lee et al., 2004; Syed et al., 2013). Importantly, these pairwise correlations and interpretations must be tempered by the interaction effects that were found.

Second, we examined the moderating role of ethnic identity in the association between discrimination and adjustment. The moderating role of ethnic identity varies by specific ethnic identity dimensions. The affective dimension of ethnic identity had an exacerbating effect on the relation between discrimination and externalizing problems. For transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents with higher ethnic pride, discrimination was associated with greater externalizing problems. R. M. Lee (2005) reported similar findings on the role of the affective dimension of ethnic identity in the context of high discrimination among a group of non-adopted Korean American college students. Similarly, we found that the behavioral dimension of ethnic identity had an exacerbating effect on the relation between discrimination and substance use. For transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents with higher ethnic engagement, discrimination was associated with greater substance use. According to self-categorization theory (Turner et al., 1987), these findings suggest that having more pride in one’s ethnic group and being more engaged with one’s ethnic group facilitates a heightened awareness of discrimination, which contributes to more negative adjustment outcomes. It is also possible that those who are more proud and engaged with their ethnic group may be at an increased risk to discrimination because they are more inclined to expect rejection based on race-based judgments. Mendoza-Denton, Downey, Purdie, Davis, and Pietrzak (2002) suggest that such race-based rejection sensitivity drives anxious vigilance and intense reactions to discrimination.

Notably, ethnic identity was only found to exacerbate the association of discrimination and outwardly expressed, or “acting out,” type of behaviors. The finding is consistent with conceptual models that include anger and antisocial behaviors as a common response to social rejection (Smart Richman & Leary, 2009). Multiple laboratory studies (see Leary, Twenge, & Quinlivan, 2006) that manipulate social rejection have produced increased aggression in participants, as shown by their willingness to engage in aversive behaviors to presumed opponents, such as blast them with loud noise (Twenge, Baumeister, Tice, & Stucke, 2001). Other research suggests that the experience of discrimination promotes an acceptance of deviance and “some kind of rebellion,” along with affiliation with friends who are substance using (Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004, p. 526). The positive association between discrimination and substance use for those youth highly engaged with their ethnic group can also be viewed from a stress and coping framework (see Miller & Kaiser, 2001). Transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents who are actively involved as a member of their ethnic group and who experience more discrimination may cope by engaging in substance use. Some scholars found that distress (including distress from discrimination) predicts substance use, but not the other way around. (e.g., Wills, Yaegar, & Sandy, 2002).

Last, it is important to note that no interaction effect was found between the cognitive dimension of ethnic identity and discrimination. This finding may offer support for the notion that dimensions of ethnic identity serve different functions. For instance, Yip (2005) found that among Chinese college students, positive feelings towards one’s ethnic group membership (affective dimension of ethnic identity) differentially predicted well-being; however, the importance of one’s ethnic group membership (cognitive aspect of ethnic identity) did not. It may also be that for younger aged adolescents the distinction between cognitive and affective dimensions of ethnic identity is not yet salient (R. M. Lee & Yoo, 2004) because cognitive complexity in ethnic identity development comes at a later age in adolescence (Phinney, 1990). Another factor to note is that the internal consistency of the EI-Cog measure was lower (α = .65), and though this value fits within the range of internal consistency estimates found in other samples (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; R. M. Lee & Yoo, 2004), self-report measures with lower internal reliability reduces the statistical power of tests of interactions (Aiken & West, 1991).

Other study limitations temper the interpretation of research findings. For instance, it is unclear as to whether the findings of our study are generalizable to a broader population beyond transracially, transnationally adopted Korean American adolescents. Specifically, it is inconclusive as to whether the exacerbating effects of ethnic identity was found due to factors related to the population’s developmental stage, adoption experiences, racial and ethnic experiences, or some combination of these factors. The fact that the exacerbating effect of ethnic identity converges with research on immigrant and native-born Asian American samples suggest that racial and ethnic experiences play a role. However, further research is necessary to understand the manner in which ethnic identity operates across groups.

More research is needed to refine measurements of ethnic identity and discrimination, to account for demographic variations of this population. Transracially, transnationally adopted youths’ ethnic identity development is complicated by experiences such as navigating the paradox of being both a member of the dominant White majority and a racial/ethnic minority. Such contradictory set of experiences may undermine ethnic identity development (R. M. Lee, 2003), or change the process of ethnic identity development. Ethnic identity development among transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents is also complicated by their socialization experience as a member of a transracial, transnational family. For instance, their ethnic identity development is less influenced by culturally-embedded experiences (i.e., speaking a native language at home, learning cultural values through direct socialization by parents and other family members who share a common ethnic heritage) than other ethnic minorities who are immigrants or native-born. Moreover, the experience of racial/ethnic discrimination for transracially, transnationally adopted individuals may be conflated with the stigma of adoption (R. M. Lee & MnIAP, 2010).

Another methodological limitation is that the data are cross-sectional. In the future, a longitudinal study would allow researchers to explore the temporal relation of ethnic identity, discrimination, and adjustment in this population. Findings from this study support the exacerbating hypothesis; still, the mechanism by which high ethnic identity is exacerbating in certain contexts is unclear. For instance, we have offered the interpretation that having high pride and engagement with one’s ethnic group may increase salience of cues regarding one’s group membership, such as racial discrimination, which then exacerbates the effects of discrimination. However, it is possible that after having experienced frequent discrimination, transracially, transnationally adopted adolescents develop more pride and engagement with their ethnic group as a way of identifying with a rejected identity (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). Additionally, future research should assess the extent to which correlational bias (i.e., shared method variance) alters the association of discrimination, ethnic identity, and adjustment, which results from the use of single-reporter data.

Despite these potential imitations, this study offers preliminary information that can inform clinical practice. It highlights that the racial and ethnic experiences of transracially, transnationally adopted individuals should not be overlooked. Particularly, it suggests that ethnic identity and discrimination are intricately related, sometimes placing transracially, transnationally adopted individuals at risk for maladajustment. This is not to suggest that ethnic identity is a risk factor for this population, but suggests that it is important for researchers and practicing psychologist alike to heavily weigh discrimination and ethnic identity as factors that contribute to adjustment.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by a K01 MH070740 grant under the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: R. M. Lee).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez AN, Juang LP, Liang C. Asian Americans and racism: When bad things happen to “Model Minorities”. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:477–492. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, Grilo CM. Ethnic differences in the predictors of drug and alcohol abuse in hospitalized adolescents. American Journal of Addiction. 2007;16:389–396. doi: 10.1080/10550490701525343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brook J, Newcomb M. Childhood aggression and unconventionality: Impact on later academic achievement, drug use, and workforce involvement. Journal of Genetic Psychology: Resaerch and Theory on Human Development. 1995;156:393–410. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1995.9914832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy C, O’Connor RC, Howe C, Warden D. Perceived discrimination and psychological distress: The role of personal and ethnic self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cederblad M, Höök B, Irhammar M, Mercke A. Mental health in international adoptees as teenages and young adults. An epidemiological study. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1999;40:1239–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Takeuchi DT, Barbeau EM, Bennett GG, Lindsey J, Krieger N. Unfair treatment, racial/ethnic discrimination, ethnic identification, and smoking among Asian Americans in the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:485–492. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan S, Monin B. “Where are you really from?”: Asian Americans and identity denial. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:717–730. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdie, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Galliher RV, Jones MD, Dahl A. Concurrent and longitudinal effects of ethnic identity and experiences of discrimination on psychosocial adjustment of Navajo adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:509–526. doi: 10.1037/a0021061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Waski BH, Jenkins R, Garcia H, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Deveopment. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Ryan A, Laflamme D, Holt J. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendents, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: The added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1821–1828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Spencer M, Chen J, Takeuchi D. A nationwide study of discrimination and chronic health conditions among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1275–1282. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombok S, MacCallum F, Goodman E. The “test-tube” generation: Parent-child relationships and the psychological well-being of in vitro fertilization children at adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:599–608. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:791–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Van Dulmen MH The International Adoption Project Team. Behavior problems in postinstitutionalized internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:129–148. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. Under contract to appear. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editors. Structural equation modeling: A second course. 2. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hjern A, Lindblad F, Vinnerljung B. Suicide, psychiatric illness, and social maladjustment in intercountry adoptees in Sweden: a cohort study. The Lancet. 2002;360:443–448. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09674-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, Abrams D, Otten S, Hinkle S. The social identity perspective: Intergroup relations, self-conception, and small groups. Small Group Research. 2004;35:246–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kim CJ. The racial triangulation of Asian Americans. Politics & Society. 1999;27:105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Our adoptee, our alien: Transnational adoptees as spectars of foreignness and family in South Korea. Anthropological Quarterly. 2007;80:497–531. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Twenge JM, Quinlivan E. Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:111–132. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DL, Ahn S. Racial discrimination and Asian mental health: A meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist. 2011;39:463–489. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. The Counseling Psychologist. 2003;31:711–744. doi: 10.1177/0011000003258087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM. Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Miller M. History and psychology of adoptees in Asian America. In: Alvarez A, Tewari N, editors. Asian American Psychology. Mahwah, N. J: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; 2009. pp. 337–363. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM Minnesota International Adoption Project. Parental perceived discrimination as a postadoption risk factor for internationally adopted children and adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:493–500. doi: 10.1037/a0020651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Yoo HC. Structure and measurement of ethnic identity for Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RM, Yoo HC, Roberts S. The coming of age of Korean Adoptees: Ethnic identity development and psychological adjustment. In: Kim IJ, editor. Korean-Americans: Past, Present, and Future. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International Corp; 2004. pp. 202–224. [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Fassinger R. The role of collective self-esteem for Asian Americans experiencing racism-related stress: A test of moderator and mediator hypotheses. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:19–28. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:896–918. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Kaiser CR. A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL. The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:470–480. doi: 10.1037/a0025193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle RH, Su S, Lavee Y. A comparison of the empirical utility of three composite measures of adolescent overall drug involvement. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14:429–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Besier M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian Refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Burrow AL, Fuller-Rowell TE, Ja NM, Sue DW. Racial microaggressions and daily well-being among Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60:188–199. doi: 10.1037/a0031736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IJ, Schwartz SJ, Lee RM, Kim M. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and antisocial behaviors among Asian American college students: Testing the moderating roles of ethnic and Americn identity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19:166–176. doi: 10.1037/a0028640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe E, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity and acculturation. In: Chun KM, Balls Organista P, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pituc SP, Jung K-R, Lee RM. Development and validation of a brief measure of perceived discrimination. Poster presented at the 37th Annual Asian American Psychological Association Conference; Toronto, Canada. 2009. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Hughes D, Way N. A closer look at peer discrimination, ethnic identity, and psychological well-being among urban Chinese American sixth graders. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:12–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, Yip T. Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Develomemt. 2014;85:40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchkin V, Jones S, Vermeiren R, Schwab-Stone M. The Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire: The self-report version in American urban and suburban youth. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:175–182. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman P. The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century: Global trends from 2001 to 2010. In: Gibbons J, Rotabi K, editors. Intercountry adoption: Policies, practices, and outcomes. Farnham: Ashgate; 2012. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smart Richman L, Leary MR. Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychological Review. 2009;116:365–383. doi: 10.1037/a0015250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SL, Lee RM. The past and present cultural experiences of adopted Korean American adults. Adoption Quarterly. 2009;12:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Kiang L, Supple AJ, Gonzales LM. Ethnic identity as a protective factor in the lives of Asian American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014 Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Bucceri J, Lin AI, Nadal KL, Torino GC. Racial microaggressions and the Asian Americane experience. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:72–81. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Walker LHM, Lee RM, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Armenta BE, Huynh QL. A two-factor model of ethnic identity exploration: Implications for identity coherence and well-being. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2013;19:143–154. doi: 10.1037/a0030564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner J. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin W, Worchel S, editors. The social psychology of intergroup relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1979. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Ong A. A daily diary invesetigation of Latino ethnic identity, discrimination, and depression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:561–568. doi: 10.1037/a0020652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AGTT, Lee RM, Burgess DJ. Perceived discrimination and substance use in Hispanic/Latino, African-born Black, and Southewast Asian immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:226–236. doi: 10.1037/a0016344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Hogg M, Oakes P, Reicher S, Wetherell M. Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, Tice DM, Stucke TS. If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1058–1069. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez M. Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4:9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross W, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ Ethnic Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed S. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Yaeger AM, Sandy JM. Buffering effect of religiosity for adolescent substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:24–31. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T. Sources of situational variation in ethnic identity and psychological well-being: A palm pilot study of Chinese American students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;31:1603–1616. doi: 10.1177/0146167205277094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Fuligni AJ. Daily variation in ethnic identity, ethnic behaviors, and psychological well-being among American adolescents of Chinese descent. Child Development. 2002;73:1557–1572. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Racial discrimination and psychological distress: The impact of ethnic identity and age among immigrant and United States-born Asian adults. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:787–800. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Lee RM. Ethnic identity and approach-type coping as moderators of the racial discrimination/well-being relation in Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Lee RM. Does ethnic identity buffer or exacerbate the effects of frequent racial discrimination on situational well-being of Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HC, Steger MF, Lee RM. Validation of the subtle and blatant racism scale for Asian American college students (SABR-A2) Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:323. doi: 10.1037/a0018674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon DP. Causal modeling predicting psychological adjustment of Korean-born adolescent adoptees. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2001;3:65–82. [Google Scholar]